Abstract

As rapid urbanisation accelerates in Global South cities, regulatory upzoning is widely promoted as a tool to expand supply and foster compact growth. Yet the interaction between permissive rules, market valuation, and institutional capacity remains underexplored. This article examines Hyderabad’s near two-decade experiment with Floor Space Index deregulation, introduced through Government Order Ms. No. 86 (2006), which eliminated citywide density caps and allowed premium-based flexibility. Using a geocoded dataset of over 9200 projects matched with government circle rate tables, spatial accessibility measures, and a subset of 2500 properties for regression analysis, this study evaluates how rules, price signals, and institutional arrangements shaped development outcomes through a rules–prices–institutions analytical framework. Results reveal that deregulation produced highly selective verticalisation, with high-rise projects concentrated in the western IT corridor while most of the city retained low-to-mid-rise form. Regression estimates demonstrate that FSI and height are capitalised in market prices but remain statistically insignificant in government valuations, reflecting a systematic undervaluation of high-intensity development in official pricing schedules. Institutional fragmentation and valuation inertia thus created a “capture gap,” where fiscal returns failed to match private value increments. The findings underscore that effective densification requires dynamic alignment of regulatory latitude, real-time valuation, and integrated governance. Hyderabad’s case illustrates broader lessons for Global South cities: the analysis demonstrates that the proposed framework is transferable beyond the empirical setting, and that blanket deregulation without fiscal and institutional reform entrenches inequality and weakens the public dividend from urban growth.

1. Introduction

Urban land policy reforms in rapidly growing cities have increasingly turned to deregulation as a means of enabling densification, expanding housing supply, and mobilising resources for infrastructure. Among the most widely used regulatory levers is the Floor Space Index (FSI), or Floor Area Ratio (FAR), which governs the intensity of development permissible on a given parcel. While advocates of FSI liberalisation often argue that higher or flexible limits unlock latent development potential, empirical research shows that the impacts of such reforms are uneven, shaped by local market conditions, state valuation practices, and institutional capacity [1,2,3].

Recent scholarship underscores that regulatory reform alone is rarely sufficient to produce widespread or equitable densification. Studies from Auckland and elsewhere show that even blanket upzoning tends to generate selective development, with outcomes mediated by pre-existing urban form, historical land ownership, and state action [1,2]. The effectiveness of FSI regulation is fundamentally mediated by urban economic forces, notably the classical trade-off between land rents and distance to major employment centres. Moreover, excessive building height restrictions, such as those that FSI limits impose, have been shown to induce significant economic costs, including underinvestment in land improvement and urban sprawl. In the Indian context, additional challenges arise from the misalignment between state-determined valuation instruments, such as circle rates, and actual market prices, reflecting the political–institutional production of land values rather than purely market-based pricing. This divergence constrains the ability of governments both to capture increments in land value and to shape development trajectories effectively [4]. Further, negotiations between state institutions and private developers—whether over land conversion, approvals, or revenue sharing—add another layer of institutional mediation, often diluting the redistributive or supply-enhancing intent of reform [5]. These studies suggest that deregulation outcomes depend not only on planning rules but also on how price signals are constructed and transmitted through state institutions.

Hyderabad offers a particularly instructive case of radical deregulation, initiated in 2006 via Government Order (G.O. Ms. No. 86), which effectively abolished FSI caps across the metropolitan area. The reform replaced fixed limits with a premium-based system that allowed density to be determined by market demand. Nearly two decades later, outcomes are strikingly uneven. High-rise clusters have proliferated in the western IT corridor, while much of the broader metropolitan region remains characterised by low-to-mid-rise development. This selective densification highlights a core puzzle: why did such a radical reform—designed to unleash development citywide—result in only partial transformation?

To address this question, this article advances a triadic framework centred on the interaction of rules, prices, and institutions, drawing on urban economics, institutional theory, and planning scholarship to conceptualise densification as a co-produced outcome of regulation, valuation, and governance capacity. The first dimension concerns the rules themselves: the deregulation of FSI and the removal of statutory development limits. The second concerns prices, specifically the misalignment between administratively determined circle rates and market valuations, which affects both development incentives and fiscal capture, and shapes how land value increments are formally recognised, taxed, and shared. The third concerns institutions, including the state’s regulatory capacity, the instruments through which deregulation was implemented, and the negotiation processes that mediated development rights, including the administrative and political processes through which valuation systems are updated, enforced, and contested. The logical relationship is sequential and interdependent: rules define legal development capacity; prices capitalise that capacity based on location and demand; and institutions determine how—if at all—value increments are recorded, revised, and redistributed. The central hypothesis is that, in the absence of alignment across these three dimensions, regulatory reform produces nodal and selective densification rather than citywide transformation, a pattern increasingly observed across rapidly urbanising cities in the Global South.

Accordingly, this article pursues two objectives. First, it examines the spatial and density patterns of Hyderabad’s built form since the 2006 reform, highlighting where and why deregulated FSI has been realised. Second, it analyses the role of valuation practices and institutional arrangements in mediating these outcomes. Together, these objectives contribute to broader debates on the conditions under which upzoning and land use deregulation can deliver compact and equitable urban growth in the Global South and advance a transferable analytical framework for diagnosing policy failure in deregulated urban land markets.

This study adopts a mixed-methods design, combining geospatial and statistical analysis of building heights, sanctioned projects, and property values with documentary evidence from valuation schedules, government orders, and secondary reports. This enables a systematic assessment of realised FSI, valuation alignment, and institutional mediation across both space and regulatory regimes.

In planning theory and urban economics, statutory planning controls are widely understood as enabling conditions for development rather than sufficient triggers of spatial transformation. Debates on densification increasingly show that statutory reforms are necessary to permit higher intensities but are insufficient to deliver them uniformly. From a foundational urban economic perspective, density restrictions, commonly implemented via Floor Area Ratio (FAR) or FSI caps, constrain the efficient utilisation of scarce urban land. Theoretical models, particularly those using the Constant Elasticity of Substitution (CES) housing production functions, demonstrate that stringent building height restrictions impose significant economic costs, primarily by causing underinvestment in land improvement, reducing aggregated land rent, and inducing urban sprawl due to diminished housing output in the inner city [6]. Conversely, FSI liberalisation is expected to facilitate agglomerative economies by enabling high employment and population densities to concentrate in strategic, well-serviced areas, which is critical for boosting mass transit ridership and access to urban amenities. For instance in Auckland, broad upzoning raised construction yet in highly selective patterns, with take-up concentrated where market conditions and local morphology were favourable [2,7]. Historical layouts and parcel structures channel change into specific corridors, producing an “even geography” of redevelopment rather than citywide transformation [1]. Behavioural responses further temper outcomes: landowners may delay or stage redevelopment despite permissive rules, dampening the expected supply response [3], and the benefits of regulatory latitude can accrue unevenly across sites and owners [8]. Collectively, this work cautions against presuming that rule changes alone will translate into broad-based densification, reinforcing the view that regulatory permission is filtered through market structures and institutional constraints.

A convergent strand examines how value is signalled and captured once rights are relaxed. Urban economics has long emphasised that land prices reflect both accessibility and regulatory constraints, rather than simply construction costs or demand pressure [9]. The spatial distribution of this value is determined by classic microeconomic principles, specifically the trade-off between land rents and transportation costs, which dictates that land value capitalises heavily on proximity to employment centres and infrastructure [9]. Municipalities can recoup part of planning-induced increments, but only where instruments and administrative valuation, which in many systems functions less as a market proxy and more as a fiscal and regulatory instrument, are credible and enforceable [10,11]. Political-economy analyses emphasise that land value capture is contingent—its legitimacy, design, and timing condition whether value increments are socialised or remain private [12,13]. Methodological contributions show that measured “zoning effects” on land and real estate are sensitive to context and the sequencing of permissions and charges [14]. In India, long-standing misalignment between circle rates and market values weakens fiscal capacity and distorts incentives, limiting the ability of authorities to convert regulatory latitude into public revenue [4]. In this setting, circle rates operate as administratively fixed valuation schedules rather than market-clearing prices, introducing structural rigidities into land markets. This disconnect is amplified by institutional lag, such as the practice of deferring circle rate revisions for long periods, which decouples administrative pricing from rapid market transformation. Relatedly, estimates of zoning reform’s economic value depend on whether institutional channels transmit price signals effectively into realised outcomes [5].

Beyond valuation itself, there is a growing body of literature on the economic consequences of density restrictions. Using Beijing as a case, Ding [6] demonstrates that building height restrictions can impose substantial welfare losses through underutilisation of land, suppressed investment, and outward urban expansion—effects that weaken agglomeration economies and raise housing costs. This evidence reinforces the argument that valuation regimes and regulatory constraints interact in shaping land market outcomes.

These dynamics are ultimately institutional. Densification policies succeed when planning systems coordinate actors and instruments—especially where redevelopment is intended around transport or growth corridors [15]. Institutional design shapes how the “value of land” is co-produced by policy, infrastructure expectations, and markets, and thus how much of that value can be directed to public aims [16]. A parallel contribution emerging from urban morphology and complexity science focuses on the statistical distribution of building heights and densities. Batty [17] demonstrates that urban built form commonly follows scaling laws, with a small number of tall structures and many low-rise buildings—a pattern that reflects both market competition and spatial constraints. In cities where regulation or valuation suppresses heights, this distribution departs from its theoretically expected form, signalling regulatory distortion rather than market driven equilibrium. More broadly, cities are shaped by market signals filtered through regulatory frameworks; reforms work when institutions align incentives and information rather than attempt to substitute for them [18,19]. At metropolitan scale, this implies that regulatory permission (rules), valuation credibility (prices), and administrative capacity (institutions) operate jointly to determine whether upzoning yields compact and equitable growth, and whether actual development trajectories approximate or diverge from their economically expected density distributions [20].

Despite progress, three gaps remain clear. First, much of the robust upzoning evidence comes from OECD contexts; there is less systematic empirical work from rapidly urbanising cities where fiscal regimes and administrative capacity differ markedly. This limits understanding of whether the economic and regulatory models applied in developed markets, which rely on strong institutional credibility and responsive valuation systems, are transferable to the volatile and fragmented governance environments of the Global South. Second, existing studies often analyse rules, prices, and institutions in isolation; fewer examine their interaction as a system governing both spatial form and fiscal outcomes. Third, while traditional urban studies address density regulation, there is a distinct need to systematically compare the observed spatial distribution of density (built height and FSI) with both theoretical scaling patterns and state-determined administrative valuations, such as circle rates [17]. The pattern of density distribution, which often follows scaling laws based on urban form and population, provides a useful theoretical benchmark against which to assess the success of deregulation. By analysing Hyderabad’s radical FSI deregulation through a rules–prices–institutions lens, this study contributes evidence on how regulatory permission, undervalued prices, and institutional mediation together yield selective, rather than citywide, densification thereby linking planning reform to land valuation failure and institutional inertia within a unified analytical framework.

2. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a cross-sectional, quantitative research design to evaluate the effects of Hyderabad’s deregulation of FSI on development intensity and valuation. Hyderabad provides a distinctive case owing to the radical reform introduced through Government Order Ms. No. 86 (2006), which abolished fixed FSI ceilings and introduced a premium-based system that allowed developers to build beyond the base FSI by paying impact-linked fees. These charges were intended to finance civic infrastructure, embedding an early form of value capture into the regulatory framework. The Hyderabad Building Rules (G.O. Ms. No. 168, 2016) subsequently linked maximum achievable density to abutting road width, while preserving exclusions in sensitive zones such as the GO 111 catchment (Osman Sagar and Himayat Sagar lakes), heritage precincts in the Old City, and high-value neighbourhoods such as Jubilee Hills and Banjara Hills. The metropolitan region spans 7228 km2 under the Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority’s Metropolitan Development Plan–2031, which envisioned polycentric growth along the Outer Ring Road (ORR). Yet in practice, vertical development has clustered in western corridors such as HITEC City, Gachibowli, Kokapet, and Narsingi, making Hyderabad an instructive case for examining how deregulated rules interacted with valuation and locational factors.

The empirical analysis draws on multiple data sources. Project-level approvals were collected from the Telangana State Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA), including sanctioned built-up area, plot size, and number of floors, which enabled the calculation of realised FSI. Market data were obtained from property listings on 99acres.com and Magicbricks.com, which provided information on building height, property type, price per square foot, and—critically—geocoded latitude and longitude coordinates. These coordinates allowed the construction of spatial variables such as distance to HITEC City and position relative to the ORR, and also supported comparative benchmarking against other Indian metros (Mumbai, Gurgaon, Kolkata), which continue to operate under more restrictive FSI regimes. Circle rate tables, issued by the Telangana Registration and Stamps Department, supplied government-notified valuations, which were standardised to per-square-metre values to ensure comparability. After cleaning and matching across sources, a dataset of approximately 2500 properties was assembled that contained both physical and pricing information.

The analysis proceeded in three stages. First, descriptive comparisons were made between Hyderabad and other Indian metropolitan regions (Mumbai, Gurgaon, Kolkata) using property listing data to examine distributions of building height and realised FSI, to situate the case in a national context. Second, within Hyderabad, descriptive spatial analysis assessed the relationship between realised FSI, market price, and circle rates, with a particular focus on corridors adjoining HITEC City and the ORR. Third, regression models were estimated to quantify the determinants of valuation outcomes. Two log-linear models were specified, one with market price per unit area and the other with circle rates as the dependent variable. A log-linear specification was adopted to address the right-skewed distribution typical of real estate prices and spatial variables, and to enable elasticity-based interpretation of coefficients (i.e., percentage change in the dependent variable for a one-percent change in a continuous independent variable). Variables that are strictly positive and highly skewed—including realised FSI, distance to HITEC City, and number of floors (a count variable with a wide range and asymmetric distribution)—were transformed using natural logarithms. Binary and categorical variables (property type and ORR location) were retained in level form. The general specification is:

where Yi denotes either (a) market price per square metre or (b) the notified circle rate per square metre for property i; FSIi is realised floor space index; Floorsi is the total number of storeys; DistHITECi is the network distance (in kilometres) from HITEC City; Typei is a categorical variable indicating residential or commercial use; ORRi is a binary indicator for whether the property falls within the Outer Ring Road; Agei measures years since project approval; and ϵi is the error term.

Separate models were estimated to isolate how deregulation affects private valuations (market prices) versus state valuations (circle rates).

Several limitations warrant acknowledgement. The dataset, while substantial, does not capture informal construction or unregistered developments. Circle rates are revised periodically, introducing potential lag relative to market valuations. Geocoded coordinates from listings allowed spatial positioning but are dependent on platform accuracy. Finally, omitted factors such as construction quality or developer reputation may bias results in unobservable ways. Nonetheless, by combining multiple data sources and explicitly comparing government and market valuations, this study offers a rigorous test of how deregulated rules, valuation mechanisms, and locational factors interact to shape development outcomes.

3. Results

This section presents the empirical results of this study, organised into three parts to construct a coherent narrative of Hyderabad’s development post-deregulation. First, Table 1 and Figure 1 present a comparative analysis of Hyderabad’s building height distribution against other major Indian metropolitan regions—Mumbai, Gurgaon, and Kolkata—to contextualise its vertical development profile. Second, a descriptive analysis of Hyderabad’s built form provides details on the spatial and temporal patterns of development intensity, using property listing and Real Estate Regulatory Authority data. Finally, the results of two parallel regression models are presented to quantify the determinants of market prices and government-set circle rates, highlighting the divergence between market logic and official valuation metrics.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics Across Four Cities.

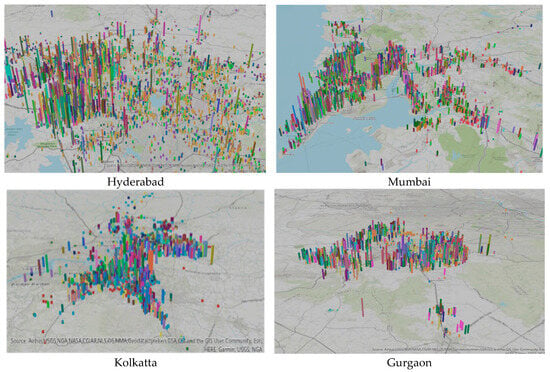

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of property listings in four metropolitan regions. Authors’ analysis of 99acres data.

3.1. A Paradox of Verticality: Comparative Building Heights

A policy of deregulated Floor Space Index (FSI) might be expected to produce a taller, denser city. However, despite the removal of FSI caps in 2006, Hyderabad’s built form remains predominantly low-rise when compared to metropolitan areas with stricter density controls. As shown in Table 1, 67.2% of residential buildings in Hyderabad have five or fewer floors, a share far exceeding that of Mumbai (8.3%), Gurgaon (38.8%), and Kolkata (52.7%). The city’s mean building height of 9.2 floors is less than half of Mumbai’s (23.8).

At the upper end of the spectrum, Mumbai’s verticality stands out. Nearly a quarter (23.4%) of its buildings exceed 30 floors, with the tallest rising to 117 floors. In Hyderabad, data indicates that only 8.7% of buildings surpass this height, and its tallest building reaches 63 floors. Gurgaon and Kolkata fall in between, with maximum heights of 51 and 62 floors, respectively. In mid-rise (10–20 floors) and high-rise (above 20 floors) categories, Hyderabad consistently shows lower percentages than Gurgaon and Mumbai. For instance, in the 15–20 floor range, Hyderabad has 3.1% compared to Gurgaon’s 14.6% and Mumbai’s 17.2%. Even in taller ranges (e.g., 40–45 floors), Hyderabad’s 1.8% is higher than Gurgaon’s 0.7% and Kolkata’s 0.6% but lower than Mumbai’s 4.6%. Mumbai, with regulated FSI, stands out with a significant share of buildings above 50 floors (8.2%), while Hyderabad has only 0.2% in this range.

Descriptive statistics further underline the disparity. Hyderabad’s mean building height is 9.2 floors, less than half of Mumbai’s 23.8 and below Gurgaon’s 14.8, and Kolkata’s 10.1. Median values reinforce this pattern: Hyderabad and Kolkata both have a median of 5 floors, while Gurgaon and Mumbai stand at 14 and 20, respectively.

Measures of dispersion and shape also differ significantly. Hyderabad’s standard deviation in floor counts is 10.9, indicating some variation but lower than Mumbai’s 16.5. Hyderabad’s Q1 (3) and Q3 (12) indicate that 75% of its properties have 12 or fewer floors, a tighter range compared to Gurgaon (22) and Mumbai (32), and closer to Kolkata (15). The high skewness (1.73) in Hyderabad suggests a right-skewed distribution with a long tail of taller buildings, but the low median (5) and high percentage of 0–5 floor properties (67.2%) imply that this tail is relatively sparse. Mumbai and Gurgaon, despite regulated FSI, show broader IQRs (20 and 18) and higher medians, indicating a greater concentration of mid-to-high-rise buildings. Skewness (1.73) and kurtosis (2.07) confirm a strong tilt toward shorter buildings, with a concentration around the lower end of the distribution. Mumbai, by comparison, shows a wider and flatter profile (skewness 1.27, kurtosis 2.26), while Gurgaon has the least skewed and most evenly distributed height profile (skewness 0.69, kurtosis −0.41).

A bin-wise breakdown shows that only 5.9% of Hyderabad’s buildings exceed 20 floors. In Mumbai, that figure is 23.8%. Gurgaon and Kolkata lie in the middle, at 13.8% and 10.4%, respectively. These summary statistics reinforce that, even relative to cities with formally lower FSI limits, Hyderabad’s deregulation has not translated into a systematically taller urban form.

Figure 1 shows the spatial distribution of property listings across Hyderabad, Mumbai, Kolkata, and Gurgaon. While Hyderabad exhibits a strong concentration of listings in the western IT corridor, the other cities display more spatially dispersed development patterns.

3.2. Spatial and Temporal Dimensions of Development in Hyderabad

Despite the formal removal of FSI caps, developers have exercised this flexibility selectively, concentrating high-rise construction in a few high-demand corridors—most notably the western IT cluster near HITEC City, the Financial District, and along the ORR—while large parts of the city remain dominated by mid- and low-rise typologies. This spatial concentration underscores a pattern of calculated intensification, where developers pursue vertical growth only in zones that offer both economic viability and infrastructural support.

Drawing from 15,406 listings on 99acres, 9249 RERA-registered projects, and a matched subset of over 2500 records, the analysis that follows examines the spatial and temporal contours of this pattern. Rather than a simple story of liberalisation leading to uniform densification, the data points to a differentiated urban form shaped by proximity to employment nodes, timing of development, and the cost–benefit calculus of builders. Even in a deregulated environment, verticality comes at a premium: where land prices, absorption rates, and infrastructure capacity align, the economics justify high-rise formats; elsewhere, developers default to more modest typologies. The result is an uneven skyline that reflects not just policy change, but the underlying logic of market demand.

Hyderabad’s property market skews young. Of the 11,576 records with age data, nearly half (48.3%) are classified as new or recently completed: 2340 projects under construction, and a further 6747 falling within the 0.5, 1, or 3-year age bins. In contrast, just over 21% of the listings are in the older 7- or 11-year categories. As summarised in Table 2, this distribution points to a relatively recent surge in supply, consistent with the timeline of deregulation and Hyderabad’s westward economic expansion.

Table 2.

Distribution by age of properties.

Hyderabad’s vertical growth displays a distinctive spatial concentration, combining nodal hubs with corridor patterns. A significant share of taller, denser projects cluster around the western IT corridor, particularly in proximity to HITEC City, which functions as a primary node. However, rather than a tight centralised core, the bulk of development fans out along a broader arc—forming a belt of intensified activity that extends from the Financial District and Kokapet to Gachibowli, Kondapur, and beyond. Projects within 5 to 10 km of HITEC City represent the single largest distance band in our dataset (3476 properties), followed by 10–15 km (2787 properties). In contrast, the innermost zone (0–2 km) accounts for just 239 listings, highlighting the limited availability of centrally located land and the preference for adjacent high-growth zones. These patterns are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Property count by distance to HITEC City.

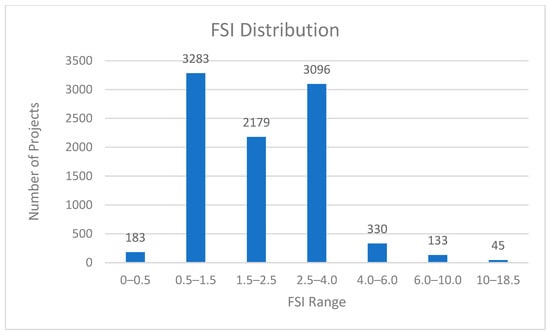

While listing data offers a market-facing snapshot, RERA filings provide a project-level view of approved development volumes. Across 9249 projects, the average land parcel spans 22,016 sqm, with an average approved built-up area of 23,220 sqm. This translates into a citywide average FSI of 2.11—far below the theoretical ceilings enabled by deregulation. The pattern of vertical growth is not uniform, but concentrated in areas such as the western corridor near Kokapet, Nanakramguda, HITEC City, where development pressure and proximity to economic hubs likely support taller construction. As shown in Table 4, the distribution is strongly skewed, with a mode of 1.00 and a long tail extending up to 18.34 in rare high-rise projects.

Table 4.

FSI Utilisation in RERA-Registered Projects.

Despite regulatory flexibility, most projects opt for moderate intensities: the median FSI is 2.34, and 25% of projects operate below 1.4. The skewness (2.16) and kurtosis (11.24) confirm a sharp clustering around low-to-mid FSI values, punctuated by a small number of vertical outliers, as seen in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2.

FSI Distribution. Authors analysis.

The combined 99acres–RERA subset (~2500 properties) enables a closer look at how deregulation has translated into built form. Here, FSI patterns mirror the broader RERA sample, but with sharper geographic clarity. FSI utilisation correlates strongly with proximity to HITEC City: properties within 5–10 km average 4.89, more than triple the outer 20–50 km band (1.45). The gradient is steep and consistent—dropping from 4.68 in the 2–5 km ring to 3.19 at 10–15 km, and continuing downward beyond. Table 5 reports the average FSI by distance band, illustrating how realised density falls systematically with greater distance from the employment core.

Table 5.

FSI Utilisation in relation to distance from HITEC City.

The spatial concentration of development intensity is mirrored in property values. Circle rates (government-assessed values) show a clear distance decay. In Hyderabad, properties within 2 km of HITEC City command average rates of INR27,000 per square yard, dropping to just INR4600 for properties 20–50 km away. Market prices follow a similar pattern, though with interesting variations. Properties 0.5 years old command significantly higher prices than both brand new and older properties, suggesting a premium for newly completed developments that are ready for immediate occupation. Taken together, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 and Figure 1 and Figure 2 show that both density and value are strongly concentrated in the western corridor, reinforcing the selective nature of verticalisation.

Contrary to what might be expected, the analysis shows no significant difference in average FSI between properties near Hyderabad’s Outer Ring Road (ORR) (3.70) and outside (3.65) the region. This further confirms that regulatory freedom alone does not determine development patterns—market forces and economic considerations play the decisive role.

3.3. Determinants of Value: Market Prices vs. Government Valuations

To quantify how these development patterns are reflected in property values, two parallel log-linear regression models were estimated. Model 1 assesses the determinants of market prices, while Model 2 examines government-set circle rates. The main coefficients and model fit statistics are reported in Table 6 and Table 7 (Model 1) and Table 8 and Table 9 (Model 2).

Table 6.

Model 1 Summary.

Table 7.

Coefficients a Estimate—Model 1.

Table 8.

Model 2 Summary.

Table 9.

Coefficients a Estimate—Model 2.

3.3.1. Model 1: Market Price Determinants

The adjusted R2 is 0.354, suggesting that approximately 35.4% of the variation in property prices is explained by the selected variables. The following key results emerge:

- Development Potential: A 1% increase in permissible built-up area (FSI) is associated with a 0.057% increase in price, suggesting that the market assigns a modest premium to properties with higher potential for vertical expansion. Similarly, the number of floors—a proxy for constructed density—is positively correlated with value, with a 1% increase linked to a 0.144% rise in price. The coefficient magnitude of floors—more than double that of FSI—indicates that actual vertical implementation carries greater market value than theoretical development potential alone. These relationships indicate that while development rights are priced in, they do not dominate buyer preferences.

- Distance to HITEC City: Distance to HITEC City emerges as a major spatial determinant. The coefficient (−0.289) implies that a 1% increase in distance reduces price by nearly 0.3%, underscoring the centrality of employment cores in shaping market value. This confirms the descriptive evidence that price gradients are anchored around the western IT corridor. Interestingly, the other distance variable is insignificant, suggesting that network connectivity, rather than radial proximity, may matter more.

- Property Type: The results indicate strong price differentiation across property types. Apartment listings are associated with significantly lower prices per unit area, with a coefficient of −0.702 (p < 0.001), suggesting a substantial discount relative to other categories. In contrast, independent houses and residential land are priced considerably higher, with coefficients of 0.609 (p = 0.001) and 0.649 (p < 0.001), respectively. This segmentation reflects the distinct ownership structures and market positioning of each property type. Apartments, while representing the bulk of new supply, are typically built at higher densities and cater to a broader, often more price-sensitive segment. By contrast, independent houses and residential plots tend to be lower in supply, offer greater exclusivity and land control, and thus command a premium. This differentiation is particularly notable in Hyderabad, where deregulation has enabled both high-density apartment construction and the persistence of standalone housing, resulting in a dual market structure that shapes both affordability and investment patterns. The strength of these coefficients suggests a structurally distinct valuation logic.

- ORR Region: The ORR zone does not significantly impact prices (B = 0.037, p = 0.129), suggesting no clear market premium for policy-induced development rights. This is particularly notable given that the ORR was specifically designed as a growth corridor with special development charges, deferred development charges, and area development plans intended to capture land value increments. The absence of a statistically significant premium in the ORR zone underscores a key finding: infrastructure provision and regulatory incentives alone do not automatically translate into higher market valuations; instead, proximity to economic anchors like HITEC City (β = −0.289, p < 0.001) remains the dominant spatial driver.

3.3.2. Model 2: Government Valuation Through Circle Rates

The persistent misalignment between market prices and government-assessed circle rates reflects deeper structural features of India’s valuation framework. While administrative guidelines recommend regular updates, actual implementation is highly uneven. In Telangana, for example, circle rates remained largely unchanged for nearly seven years following the state’s bifurcation, despite rapid urban growth. The decision to defer revisions was shaped as much by political caution as by short-term fiscal considerations—revenue collection remained stable, reducing the perceived urgency for recalibration.

This pattern is not unique. Some states such as Maharashtra and Karnataka update circle rates on a regular cycle, while others—including parts of Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal—have experienced prolonged gaps between adjustments. The result is a valuation regime that often lags behind market dynamics, especially in rapidly transforming urban peripheries.

These delays carry important fiscal consequences. Circle rates serve as the base for stamp duty collection—typically 3–8% of transacted value—and influence property tax assessments in many Indian cities. When official rates diverge substantially from market prices, governments forgo potential revenue and weaken the integrity of land-based taxation. In Hyderabad’s western growth corridors, stakeholder estimates suggest that circle rates remain 30–50% below actual transaction values. This undervaluation not only reduces fiscal yield but also enables informal cash settlements that erode transparency and compromise accurate land market data.

The second model, using log-transformed circle rates as the dependent variable, offers a markedly different profile. The model’s adjusted R2 stands at 0.806, indicating that 80.6% of the variation in circle rates is accounted for by the predictors—more than double the explanatory power of the market price model. This higher explanatory power suggests a more systematic and predictable valuation approach by government assessors, though not necessarily one that reflects real-time market dynamics. The results are summarised below:

- FSI: The coefficient is small and statistically insignificant (B = 0.017, p = 0.132), suggesting that official valuation norms do not price in development potential in any meaningful way. This contrasts sharply with the market model where FSI shows a significant positive effect, indicating a disconnect between how private buyers and government assessors value development potential.

- Floors: The number of floors is positively associated with circle rates (B = 0.059, p < 0.001), but the effect is more muted than in market valuations, At roughly 40% of the market model’s coefficient magnitude, this suggests that while government valuations acknowledge building height, they may underweight its economic significance relative to actual market behaviour.

- Distance to HITEC City: The coefficient is twice as large as in the market model (B = −0.576, p < 0.001), indicating that government valuations heavily penalise distance from the employment core. This amplified distance effect means that government assessments show a steeper spatial gradient than market prices—for every 1% increase in distance from HITEC City, circle rates decline by 0.576%, compared to the market’s 0.289% decline. This suggests that official valuations may be anchored to older models of city structure where proximity to central employment was more decisive.

- Property Type: Apartments are undervalued by approximately 21.9% relative to other property types (B = −0.219, p < 0.001), although the magnitude is smaller than the market model’s estimate. While both market and government valuations show apartments at a discount, the government’s more modest differential suggests that official assessments may not fully capture the market’s preference hierarchy among property types.

- ORR Region: Properties in the ORR region show a substantially lower level of circle rates, with an estimated coefficient of −0.788 (p < 0.001), implying that official valuations in this zone are roughly 55% below those in otherwise comparable locations. This dramatic discount in government valuations for the ORR zone, despite policy intentions to promote development there, reveals a significant misalignment between official assessment methods and both policy goals and market realities.

These models illustrate the divergent logic underpinning Hyderabad’s real estate market and its regulatory valuation apparatus. While market prices appear responsive to both development potential and proximity to economic nodes, circle rates remain heavily influenced by location and policy design, often lagging market trends. Notably, the effects of FSI are present but modest in market prices and almost absent in circle rates, highlighting a systematic disconnect between how value is generated in the market and how it is recorded in the state’s valuation system.

4. Discussion

Hyderabad’s deregulation of FSI in 2006 created one of the most permissive urban development regimes in India, abolishing caps that constrained density elsewhere. Nearly two decades on, the city provides a distinctive case to interrogate the relationship between permissive rules, the behaviour of prices, and the adaptive capacity of institutions. The results reported above—of skewed FSI distributions, corridor-centric clustering, and divergent valuation models—highlight how reforms intended to produce uniform verticalisation instead delivered selective, uneven intensification. Rather than interpreting this as regulatory failure, the evidence supports a structural explanation in which density outcomes emerge from the interaction of three systems: (i) regulatory permission, (ii) market valuation, and (iii) administrative valuation and governance capacity. This section dissects these dynamics through the triadic lens of rules, prices, and institutions and derives implications that generalise beyond Hyderabad.

4.1. Rules: The Selective Realisation of Deregulation

The evidence demonstrates that blanket FSI deregulation did not trigger citywide densification but instead accentuated a corridor-based geography of growth. While the statutory framework abolished ceilings, realised FSI averaged only 2.11, with the vast majority of projects clustered below 4.0 and only a handful exceeding 10.0. This pattern is consistent with international findings that broad upzoning leads to development primarily where demand is already concentrated. Greenaway-McGrevy and Phillips [2] show for Auckland that liberalisation induced construction largely in high-demand districts. Cheung et al. [7] similarly documents that in New York, rezonings increased housing supply predominantly in established market areas.

Hyderabad’s case is further underscored by the stark distance gradient: average FSI peaks at 4.89 within 10 km of HITEC City but falls to 1.45 beyond 20 km. Rather than creating polycentric growth as envisaged in the ORR strategy, deregulation reinforced the monocentric pull of the western IT corridor. This resonates with Kim’s [11] argument that blanket deregulation cannot overcome structural demand asymmetries. It also echoes the “node-centric” intensification patterns observed in Chinese cities where market strength rather than regulatory permission shapes development trajectories [21].

At the same time, the descriptive statistics suggest that rule changes were not irrelevant. High-rise clusters in Gachibowli and Kokapet would have been impossible under prior caps. What emerges, therefore, is not regulatory failure per se but a conditional rule effect: the legal permission was necessary to enable verticalisation, but sufficient only in areas with existing economic gravity and parcel consolidation. In analytical terms, Hyderabad reveals a divergence between the theoretical distribution of density (unbounded FSI) and the market distribution of density (selective spatial realisation). The ORR’s limited response underscores that permissive rules alone cannot manufacture demand in locations with fragmented ownership, lagging infrastructure, or weak accessibility. This “selective realisation” mirrors Wolf-Powers’ [13] observation that deregulation interacts with legacy market frictions, producing uneven outcomes.

Policy implication (Rules): deregulation is most effective when deployed selectively rather than uniformly. Treating FSI as a universal entitlement dilutes its allocative function. A targeted approach—where intensification is prioritised in corridors with infrastructure and demonstrated demand—preserves FSI as a planning instrument rather than reducing it to a deregulatory gesture.

4.2. Prices: Misaligned Valuation and the Capture Deficit

The second key finding is the divergence between market and official valuations. In the regressions, market prices are significantly associated with both potential density (FSI) and realised density (floors), as well as accessibility to the HITEC City node. This demonstrates that the market actively capitalises intensity and location. Circle rates, by contrast, show no significant relationship with FSI and rely heavily on distance, producing coefficients that diverge sharply from the market model.

This valuation misalignment carries profound fiscal and planning consequences. First, it generates what Smolka [12] calls a “capture deficit”: increments produced by deregulation accrue privately, as stamp duties and taxes based on circle rates lag 30–50% below observed market values [4]. In Hyderabad, this translates into lost revenues at precisely the moment when densification increases infrastructure demands. Second, it undermines the credibility of administrative pricing as a signal for development. Developers and buyers discount official rates as irrelevant to real values, creating scope for under-reporting and opacity.

The broader literature reinforces these risks. Debrunner and Kaufmann [10] argue that value capture regimes are only effective when valuations are routinely updated and transparent, otherwise regulatory reforms stall in distributional deadlock. Kim [11] shows that weak valuation undermines the fiscal rationale for upzoning. Scott [16] highlights how mismatches between market transformation and state pricing erode both equity and efficiency, allowing insiders to appropriate gains while outsiders face exclusion.

Analytically, this section reveals a decisive break between the market distribution of value and the administrative distribution of value. While prices encode location and development intensity, administrative rates suppress precisely those gradients. Hyderabad therefore exhibits the third distribution identified by this study: the “administrative distribution”, whose rigidity insulates the state from market signals and weakens fiscal synchronisation with growth. The result is a situation of “private luxury and public neglect”: vertical development proceeds, but fiscal capacity stagnates.

Policy implication (Prices): valuation reform is not secondary but foundational. Without credible pricing, deregulation transfers wealth privately without financing infrastructure. Administrative valuation must incorporate built intensity, transaction evidence, and spatial gradients—otherwise the state forfeits the very value it creates through planning reform.

4.3. Institutions: Fragmented Routines and Adaptive Actors

The third dimension concerns institutions. While the 2006 reform streamlined rules, the institutional architecture remains fragmented. The Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority sanctions projects and collects data on built-up area, FSI, and floors, but this information does not systematically feed into valuation updates by the Registration and Stamps Department. Circle rate revisions are irregular, politically mediated, and derived from heuristic locational categories rather than empirical transaction data.

Such fragmentation is not unique. Comparative scholarship notes that in many Global South cities, permissive planning reforms outpace institutional capacity to align taxation, infrastructure, and land assembly [12]. Künzel et al. [3] finds similar institutional disconnects in Latin America, where deregulation without fiscal reform led to uneven growth and weakened value capture. In Hyderabad, the lack of institutional coordination means that permissive rules empower developers where demand is strong, but institutions neither steer intensity to strategic corridors nor capture increments for reinvestment.

Actors adapt within this fragmented landscape. Developers exploit opportunities in the western corridor, but avoid speculative investments in peripheral zones where infrastructure is uncertain and valuation misalignment undermines predictability. Households make tenure and location decisions conditioned by opacity in circle rates and transaction costs, reinforcing segmentation and the “insider” dynamics Debrunner and Kaufmann [10] documents for European cities.

Analytically, institutions mediate whether theoretical capacity, market value, and fiscal claims converge or diverge. Hyderabad demonstrates what occurs when institutional recalibration lags regulatory reform: selective development, fiscal leakage, and governance asymmetry.

Policy implication (Institutions): governance integration is not optional. Data on approvals, valuations, and transactions must operate within a unified metropolitan system. Without institutional coordination, deregulation yields asymmetric benefits and weak public returns.

Hyderabad’s experience underscores that deregulation is not a substitute for planning but a multiplier of existing market structures. Density emerges not from rule change alone but from alignment across permissions, valuations, and institutions. The triadic framework advanced here therefore generalises as a diagnostic tool: Rules define capacity, Prices determine where capacity is exercised, and Institutions decide whether value becomes public revenue or private gain. Where these align, deregulation supports compact growth. Where they diverge, it produces selective verticalisation, fiscal erosion, and spatial inequality.

Hyderabad exemplifies the latter condition. Repair therefore lies not in reversing deregulation, but in governing it through valuation reform and institutional integration. Only then can density translate into both efficiency and equity.

5. Conclusions

This study examined why Hyderabad’s citywide deregulation of FSI in 2006 produced dense vertical growth in select nodes rather than uniformly across the metropolitan region. By analysing the interplay between regulatory rules, land price signals, and institutional capacity, this article advances a central conclusion: in the absence of institutional alignment and valuation responsiveness, regulatory deregulation does not generate citywide densification but instead amplifies pre-existing spatial inequalities.

Together, these findings indicate that the rules–prices–institutions framework functions as a transferable diagnostic lens for evaluating deregulation outcomes in other urban contexts, rather than as a Hyderabad-specific explanation.

The findings demonstrate that urban form is governed primarily by market valuation rather than regulatory permission alone. Consistent with urban economic theory, development intensity in Hyderabad has concentrated where the marginal revenue of vertical construction exceeds marginal cost—principally in the western IT corridor—following a steep distance–decay gradient [9]. Deregulation provided the legal capacity for vertical construction, but price signals determined its spatial expression. As a result, the removal of FSI limits did not overcome structural inertia in peripheral markets, and much of the city’s theoretical development capacity remains unrealised.

This study further identifies a systemic “capture gap” arising from the failure of administrative valuation (circle rates) to track market valuation. While the market capitalised verticality and accessibility, the state’s valuation system remained largely insensitive to development intensity. This disconnect, sustained by institutional separation between planning authorities and revenue departments, constrained fiscal capture even in the city’s highest-growth corridors. These findings validate the triadic framework proposed in this study: regulatory rules enable development, prices determine where density materialises, and institutions govern whether public value is realised.

From a policy perspective, Hyderabad illustrates a broader pattern observed in rapidly urbanising cities of the Global South. While deregulation may relax binding supply constraints imposed by height controls [6], it cannot generate demand, coordinate infrastructure, or capture value in isolation. Effective densification therefore requires governance systems that align regulatory flexibility with valuation reform and metropolitan coordination. The policy challenge is not merely to permit greater building height, but to ensure that the value created through vertical growth is systematically recovered and reinvested in infrastructure and public services.

This study has limitations. Reliance on formal RERA registrations and online listings may underrepresent small-scale or informal development, and the analysis does not evaluate second-order outcomes such as affordability, displacement, or service adequacy. Future research should pursue longitudinal analysis linking land value change to infrastructure investment, alongside comparative assessment of densification and valuation regimes across Global South and OECD cities.

Author Contributions

R.D.T.: Conceptualization, Funding generation, data collection, analysis and drafting. P.T.: Analysis, Data cleaning and modelling, revisions and redrafting. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support provided by The Infravision Foundation, which made this research possible.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from publicly accessible sources. Property listing information was obtained from 99acres (https://www.99acres.com/). Project-level development data, including built-up area and FSI, were derived from the Telangana Real Estate Regulatory Authority (RERA) portal (https://rerait.telangana.gov.in/). Government circle rate data were sourced from the Registration and Stamps Department, Government of Telangana (https://registration.telangana.gov.in/). Spatial distance calculations were carried out using geocoded listing locations and standard GIS mapping tools. All sources are in the public domain.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work the authors used Grammarly and Chat GTP-5 (OpenAI) in order to assist with English language editing. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gallagher, R. Even Geography of Upzoning: How Historic Urban Layouts, Land Use and Tenure Systems Influence Densification of Established Suburbs. Urban Policy Res. 2024, 42, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenaway-McGrevy, R.; Phillips, P.C. The impact of upzoning on housing construction in Auckland. J. Urban Econ. 2023, 136, 103555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künzel, K.; Korekt, J.; Artmann, N.; Blankertz, S.; Böhrk, L.; Render, J. Urban Densification: Understanding landowners’ inertia in building on vacant lots. disP-Plan. Rev. 2024, 60, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, M. Setting circle rates for urban property transactions. Econ. Political Wkly. 2015, 50, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Anagol, S.; Ferreira, F.V.; Rexer, J. Estimating the Economic Value of Zoning Reform. SSRN Electron. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C. Building height restrictions, land development and economic costs. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 485–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.S.; Monkkonen, P.; Yiu, C.Y. The heterogeneous impacts of widespread upzoning: Lessons from Auckland, New Zealand. Urban Stud. 2024, 61, 943–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Ruming, K.; Gillon, C.; Pinnegar, S.; Crommelin, L.; Easthope, H. “It’s Like Winning the Lottery But Without Buying a Lottery Ticket”: Housing Market Impacts of Compact City Planning, Upzoning, and Collective Sales. Urban Policy Res. 2025, 43, 33–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiPasquale, D.; Wheaton, W.C. Urban Economics and Real Estate Markets; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Debrunner, G.; Kaufmann, D. Land valuation in densifying cities: The negotiation process between institutional landowners and municipal planning authorities. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Upzoning and value capture: How U.S. local governments use land use regulation power to create and capture value from real estate developments. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolka, M. A New Look at Value Capture in Latin America. In Land Lines; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf-Powers, L. Dilemmas of 21st century land value capture: Examining Henry George’s legacy in a new Gilded Age. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2024, 56, 1738–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’aMato, M.; Zrobek, S.; Bilozor, M.R.; Walacik, M.; Mercadante, G. Valuing the effect of the change of zoning on underdeveloped land using fuzzy real option approach. Land Use Policy 2019, 86, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, C.; Renne, J.L.; Bertolini, L. Transit Oriented Development: Making It Happen; Ashgate Publishing: Burlington, VT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M. Planning and the Value of Land. Plan. Theory Pract. 2022, 23, 655–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, M. Competition in the Built Environment: Scaling Laws for Cities, Neighbourhoods and Buildings. Nexus Netw. J. 2015, 17, 831–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A. Alain Bertaud, Order without design: How markets shape cities. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 47, 734–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutt, F.E. Order without design: How markets shape cities, by Alain Bertaud. J. Urban Aff. 2020, 42, 478–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, S. Urban expansion: Theory, evidence and practice. Build. Cities 2023, 4, 124–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. Planning for Growth: Urban and Regional Planning in China; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).