Abstract

Accurate prediction of land use and land cover (LULC) change is essential for sustainable development and climate change adaptation planning. This study projects LULC changes across 17 administrative regions of South Korea from 2020 to 2050 using the Future Land Use Simulation (FLUS) model under four integrated SSP-RCP scenarios: SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5. The model was calibrated with land cover data for 2000–2010 and validated against observations for 2010–2020 using socioeconomic variables together with CMIP6 climate projections. In practical terms, FLUS produces scenario-based maps of future land patterns that inform land regulation, infrastructure planning, and climate adaptation. Across all scenarios, urban areas expanded by 488,000–585,000 ha, mainly through the conversion of agricultural land, which accounted for 10–24% of transitions in high-growth regions. Agricultural land decreased by 124,000–174,000 ha, and forests declined by 473,000–572,000 ha. Transformation intensity peaked around 2030 and then slowed in later decades. Urban expansion was greatest under SSP5-8.5, followed by SSP3-7.0, SSP1-2.6, and SSP2-4.5. Gyeonggi Province exhibited the most pronounced spatial change, whereas Seoul showed limited additional growth consistent with its already saturated urban structure. Validation results indicated an overall accuracy range of 57–83% with metropolitan areas generally outperforming provincial regions. These findings reveal spatial and temporal hotspots of land cover change and provide region-specific information that can guide urban development, land and ecosystem management, climate adaptation policy, and progress toward carbon neutrality.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, urban areas around the world have expanded rapidly, and the extent of agricultural and forest land has steadily decreased [1,2,3]. During the same period, the average annual rate of land use and land cover (LULC) change reached 0.36% which is higher than in previous decades [4]. These changes are closely linked to socioeconomic factors such as urban expansion, industrial restructuring, and population movements [5,6]. In Korea, urbanization has become more pronounced since the 1980s, with a marked increase in urban land and concurrent declines in forests, wetlands, and agricultural areas [7]. These dynamics are intensified by urban expansion associated with economic growth and housing demand, the decline of agriculture caused by rural depopulation and land conversion, and the growing need to conserve biodiversity in ecologically sensitive areas. As a result, conflicts among competing land use priorities have become more intense, and managing these pressures has become a central task for sustainable spatial planning. Previous studies have shown that changes in land use and land surface cover are associated with biodiversity loss [8], deterioration of water quality [9], air pollution [10], declines in ecosystem services [11,12], and increased climate-related risks [13]. A sound understanding of LULC dynamics is therefore important for minimizing environmental impacts and for formulating sustainable land management policies [14]. Existing LULC research can be grouped into four broad areas: technical mapping and classification [15,16], temporal change detection [17,18], scenario-based modeling [19,20,21], and environmental impact assessment [22,23,24]. Early studies mainly used satellite imagery, GIS techniques, and aerial photography to identify LULC patterns [25,26]. More recent work has expanded to examine the ecological, social, and economic impacts of land use change and to explore how future patterns may evolve under different development pathways. Even so, predicting LULC over long periods is still difficult. Widely used simulation models do not share the same assumptions or internal structure [27,28,29]. Cellular automata (CA) models, for example, use neighborhood rules to describe spatial change, but these rules are usually simple and do not easily reflect long-term socioeconomic or policy influences [30]. The CLUE-S model connects regional land demand with local allocation, yet its parameters must be tuned in detail for each application. SLEUTH reproduces urban growth patterns well, but it struggles to represent a wide range of land use categories [25]. Because of these features, long-term projections remain uncertain, and planners face limits when applying these models directly in policy-oriented planning. The Future Land Use Simulation (FLUS) model was introduced as one way to deal with these shortcomings. It links a machine learning based suitability module with an adaptive CA allocation module. In FLUS, the artificial neural network (ANN) component represents nonlinear links between socioeconomic and environmental variables [28,31], and the adaptive CA part controls inertia and competition among land use types during allocation. This design allows FLUS to produce detailed spatial maps of future land patterns that can inform zoning decisions, infrastructure investment, and conservation planning. By running the model under different scenarios, planners can compare development options and examine how regional vulnerability changes under alternative futures [32,33,34]. Building on these capabilities, FLUS has been integrated with the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) and Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) frameworks [35,36,37] and is now used in many international scenario-based studies [12,24,25,31]. In Korea, several studies have analyzed urban growth at national and metropolitan scales using data-driven and explainable machine learning models. Most of this work, however, has focused on major metropolitan areas and has given limited attention to diverse regional land transition dynamics. To date, no study has integrated LULC changes across all administrative regions of Korea with the SSP-RCP scenario framework. As a result, the policy relevance of future land use projections and the implications of alternative development pathways for regional planning have not been fully explored.

This study addresses that gap by building an SSP-RCP-driven FLUS framework at 100 m resolution for all 17 first-level administrative regions of South Korea. We first use observed LULC change from 2000 to 2020 to construct a separate 7 × 7 transition matrix for each region and to tune the corresponding model parameters. We then combine regional trajectories of population, GDP, and land demand with four SSP-RCP scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5) and feed them into the FLUS allocation module. In this way, the model produces long-term land use projections that can be used for zoning regulation, infrastructure planning, and climate adaptation, and helps multi-level planning by clarifying how sensitive each region is to different future pathways.

Study Area: Location and Characterization

The Republic of Korea is in East Asia between 33° and 38° N and 124° and 131° E. In the eastern part of the country, high elevations and rugged terrain shaped by the Taebaek and Baekdudaegan mountain ranges limit the extent of urban and agricultural development. In contrast, the western and southern regions include broad plains and low river basins along the Yellow Sea coast, which provide favorable conditions for intensive agriculture and active urban growth. These geographical contrasts create distinct regional patterns in climate, topography, and land use, which are summarized in Supplementary S5.

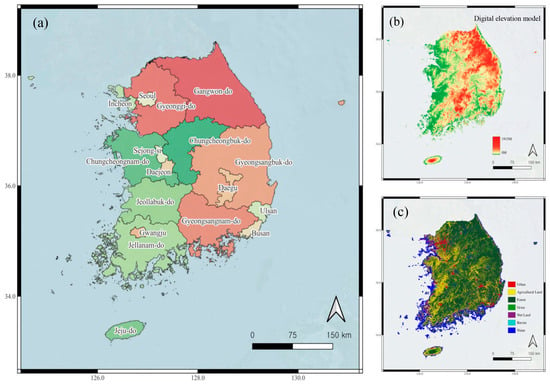

Since the 1970s, rapid industrialization and urbanization have led to the loss of farmland, an expansion of impervious surfaces, and increasing ecological pressure around the Seoul metropolitan area and coastal industrial zones. As a result, the southwestern plains remain dominated by agriculture, whereas the capital region is characterized by dense residential and industrial land uses, and the southeastern coastal zone hosts manufacturing and port-based industries. South Korea consists of 17 metropolitan-level administrative units, including 1 special city, 6 metropolitan cities, 8 provinces, 1 special self-governing province, and 1 special self-governing city. The spatial extent and boundaries of these units are shown in Figure 1. By the late twentieth century, the national economy had shifted from an agriculture-based structure to one centered on industry and services. From the 1960s onward, rapid industrialization and urbanization concentrated economic activity in the capital region and the southeastern industrial belt. Export-oriented strategies encouraged the growth of manufacturing and information technology sectors, and from the 1960s to the 1980s, migration from rural areas to cities drove the spread of large metropolitan regions. Together, these long-term changes produced the current land use pattern in which a large share of the population lives in major metropolitan areas.

Figure 1.

Study area of the Republic of Korea showing (a) administrative divisions of the 17 metropolitan and provincial regions, (b) digital elevation model (0–1915 m), and (c) MOE land cover map with seven classes (built-up, agricultural land, forest, grass, wetland, barren, and water) at 100 m resolution. All spatial data are presented in the WGS84 geographic coordinate system (EPSG:4326).

2. Methods

2.1. Framework

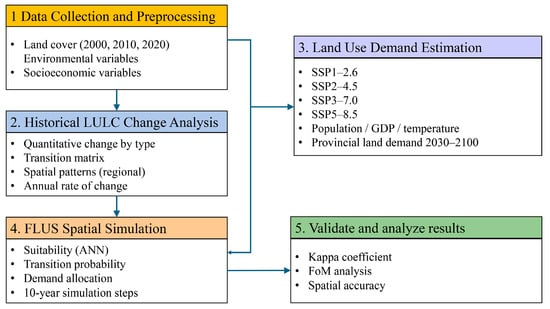

This study developed an integrated modeling framework that combines System Dynamics SD and the Future Land Use Simulation (FLUS) model to predict future LULC changes in South Korea under SSP-RCP scenarios. The framework is composed of five sequential steps, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Research framework for LULC projection in South Korea.

The workflow consists of five main steps. In the data collection and preprocessing step, environmental and socioeconomic variables are compiled, and all datasets are standardized to a common spatial resolution and coordinate reference system. In the LULC time series analysis, we quantify changes in each land cover class and examine transition matrices, and identify major conversion patterns from past LULC trajectories. Next, a System Dynamics-based land demand model combines population change, GDP growth, and climate variables to estimate future land use requirements for each administrative region under the four SSP-RCP scenarios. The FLUS spatial simulation then uses suitability maps and transition probabilities to allocate the estimated land use demand and to generate gridded LULC projections. In the final validation and analysis step, we evaluate model performance using FoM and Kappa and analyze the temporal and spatial patterns of future LULC.

Overall, the framework links machine learning based suitability estimation with scenario-driven land demand and allocation, and produces long-term LULC projections for all administrative regions of South Korea that can support land use regulation infrastructure planning and climate adaptation policies.

2.2. Data Collection and Sources

This study uses several spatial datasets to project future LULC changes in South Korea. The data are grouped into three categories. (1) Land use and land cover data; (2) socioeconomic variables; and (3) environmental and climate data. Each dataset was preprocessed for use in the FLUS model 2.4. GIS-based procedures were applied to normalize the variables and to harmonize the coordinate reference systems. To ensure consistency, all datasets were resampled to a 100 m grid raster using a majority rule. Data processing and conversion were carried out in QGIS 3.28 and with Python 3.12.10 and the GDAL 3.7.3 library. The main characteristics of these datasets are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of datasets used in this study.

2.2.1. Land Use Data

The land use data used in this study are derived from the official 100 m national land cover maps produced by the Ministry of Environment of Korea. These maps are generated from multi-temporal satellite imagery following standardized preprocessing procedures and have been provided at 10-year intervals since 1990 with an overall classification accuracy of at least 75%. This nationally harmonized dataset provides a consistent and reliable temporal baseline suitable for long-term land cover prediction under multiple SSP-RCP scenarios. As this study focuses on projecting future land cover dynamics rather than generating a new land cover classification, the analysis uses this official dataset to ensure temporal comparability and to keep nationwide SD and FLUS simulations computationally feasible.

In South Korea, land use is divided into seven broad classes: urban areas, agricultural land, forest land, grassland, wetlands, barren land, and water bodies. These classes are used consistently throughout the analysis so that spatial patterns and long-term trends in land use change can be compared in a straightforward way. Past land use maps in these classes are used to estimate transition probabilities and to prepare land use conditions for target years such as 2030 and 2050. The national land cover classification system and class codes used in this study are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Korean land cover classification system categories.

For the suitability analysis, additional spatial layers are included, such as digital elevation models and indicators of access to major roads and ports. Legally protected areas, including national parks, provincial parks, ecosystem conservation zones, and designated wetland reserves, are treated as spatial constraints where specific land use conversions are not allowed.

2.2.2. Socioeconomic Data

Socioeconomic factors are key drivers of land use change, including urban expansion, agricultural conversion, and industrial development. Population and gross domestic product (GDP) were selected as the primary variables for this study. Historical records for 2000–2020 were obtained from the Korean National Statistics Portal (KOSIS), and future projections were sourced from the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) under the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSP) framework. These projections were calibrated against historical KOSIS trends to reflect the Korean context.

For spatially explicit modeling, both population and GDP were disaggregated to a 100 m grid using a building-based allocation method that incorporates structural information from the National Geographic Information Institute (NGII). Building footprint and height data were used to estimate floor area in each grid cell, and regional totals were allocated proportionally according to each cell’s share of total floor area within its administrative unit. Cells without buildings were assigned to be valued at zero. This method provides a consistent representation of built-environment density across the national 100 m grid and supplies essential socioeconomic inputs for the FLUS-based land cover prediction.

2.2.3. Environmental and Climate Data

Climate data used in this study were obtained from NanoWeather Inc., which processed the original HadGEM3-RA regional climate model outputs developed by the National Institute of Meteorological Sciences of Korea. The HadGEM3-RA dataset was produced under the CMIP6 SSP-RCP scenario framework and is widely used as a national standard for climate impact assessments. NanoWeather Inc. downscaled the dataset to 1 km and 90 m grids using the Quantitative Topographic Model and generated daily maximum and minimum temperatures from daily means using their patented algorithm [38].

The processed climate dataset includes daily mean, maximum, and minimum temperatures. These variables are used in the SD model to represent long-term changes in regional land use demand, and in the FLUS model, they are combined with elevation, slope, and accessibility indicators as inputs for ANN training. All environmental and climate datasets were resampled to the unified 100 m spatial resolution used in the nationwide prediction framework.

2.2.4. Data Preprocessing

In this study, all spatial datasets were consolidated into a unified 100 m grid framework before integration with the SD and FLUS models. The land cover data used was not raw imagery, but the official national land cover maps produced by the Ministry of Environment of Korea. Because these maps are already atmospherically and geometrically corrected and fully classified, no additional radiometric or geometric preprocessing was required.

All raster layers were reprojected to the EPSG 5178 coordinate system, clipped to the national boundary, and aligned to a common pixel origin. The land cover map was converted to raster format, and nearest neighbor resampling was applied so that the categorical class codes were preserved. Socioeconomic and climate variables, including population, GDP, and related indicators, were also resampled to the same 100 m grid to maintain spatial consistency of the inputs. After preprocessing, all datasets shared the same spatial resolution, coordinate reference system, and grid alignment.

2.3. SSP-RCP Integrated Scenario Construction

This study uses a combined SSP-RCP setting to link socioeconomic change with different levels of climate forcing. SSPs describe how population, economy, and institutions may evolve [39], whereas RCPs specify radiative forcing targets used in climate models [40,41]. From the CMIP6 scenario matrix, we selected four pairs that are commonly used in impact studies: SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5.

In SSP1-2.6, countries move toward more efficient resource use and stronger environmental policy, and global inequality is reduced. SSP2-4.5 assumes that many current trends continue without strong shifts in either a sustainable or a highly fossil fuel-intensive direction. SSP3-7.0 describes a world with frequent regional conflict, weak international cooperation, and slow economic growth. SSP5-8.5 combines rapid economic expansion with heavy reliance on fossil fuels and high energy demand.

Most applications of these SSP-RCP combinations have focused on global or continental scales, and work for South Korea has often been limited to a few sectors or regions. Here, we apply the four SSP-RCP scenarios to all 17 first-level administrative regions using the FLUS model. For each region, transition matrices and key parameters are calibrated separately so that differences in land transition behavior and future land demand under each socioeconomic and climate pathway can be examined explicitly.

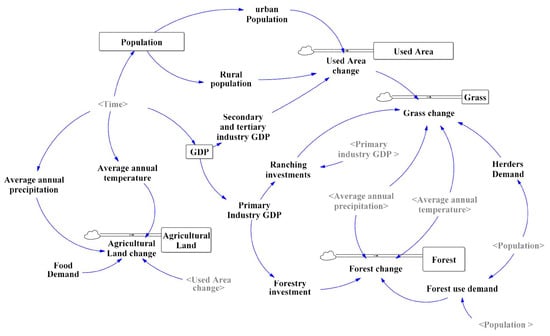

2.4. System Dynamics

The System Dynamics model developed in this study represents the interactions among population, economic activity, climate variables, and land use demand. Population growth increases the demand for residential, industrial, and commercial land while also influencing agricultural demand through changes in food consumption. Economic activity modifies the scale and structure of production in the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors and therefore alters the demand for cropland, forest, and grassland. Long-term changes in temperature and precipitation influence agricultural and forest conditions and consequently modify land use demand through climate-driven responses [42].

The SD model simulates land use demand from 2020 to 2050 at 10-year intervals. To build the model, we use data from 2000 to 2020 to estimate how population, GDP, and climate variables are related to each land use class. These estimated relationships are coded as nonlinear functions in the SD structure. In this way, the model reflects how demographic and economic growth can increase land use demand.

Future projections follow a two-step approach. The SSP2-4.5 scenario was used as the baseline because it represents a middle-of-the-road socioeconomic trajectory. The SD model was first calibrated with population GDP and climate variables under SSP2-4.5 to generate baseline land use demand to 2050. The remaining SSP1-2.6, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5 scenarios were applied by adjusting socioeconomic and climate forcings relative to the SSP2-4.5 path while maintaining the same functional structure.

The SD model was applied separately to each of the 17 administrative regions. For every region, an SD module was built using regional time series data from 2000 to 2020, including population, GDP, and other socioeconomic indicators, so that changes in regional demographic and economic conditions are reflected in LULC change. A detailed description of the SD model structure is provided in Supplementary S1 and the overall structure of the SD module is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

System Dynamics.

2.5. FLUS Model and Spatial Simulation

The FLUS model allocates land cover on a 100 m grid using land use demand from the SD model and estimated transition probabilities and produces maps of future land cover. FLUS builds on a basic cellular automata (CA) structure by combining suitability maps, an adaptive inertia term, and a built-in competition mechanism among land use classes [31]. With this setup, the model can link land use demand estimated at the regional scale with cell-based spatial allocation.

In many standard CA applications, transition probabilities are fixed, and it is difficult to reflect external drivers or interaction among land use types. In FLUS, the inertia and competition parameters are updated during the simulation so that the allocation can respond to different local conditions and to changes in land demand under each scenario. This helps the simulated spatial patterns stay consistent with the total land use demand for each class given by the SD model. Compared with approaches such as Markov chain models that rely only on historical transition probabilities, FLUS adds neighborhood effects, suitability factors, and adaptive transition rules.

These additional elements allow the model to follow long-term land cover trajectories under the SSP-RCP scenarios rather than simply extrapolating past transitions.

2.5.1. Model Structure and Suitability Assessment

In this study, the FLUS model was run on a 100 m grid for all 17 first-level administrative regions of South Korea. For each region, a separate suitability surface was prepared so that spatial allocation reflects the existing land use patterns in that region. Details of the suitability variables and parameter ranges are provided in the Supplementary Materials (Figures S1 and S2). Suitability for land cover class j at location p and time t is calculated by the ANN as shown in Equation (1).

where are the driving variables and are the trained weights. A sigmoid activation function is applied so that the final suitability value remains between 0 and 1 and can be interpreted as a suitability probability.

Neighborhood effects are represented with an N × N Moore neighborhood window. In this study, N was set to 5. The neighborhood term for land cover type k is calculated as shown in Equation (2).

where represents the count of cells with land cover type k in the neighborhood, and denotes the neighborhood weight for land cover type .

2.5.2. Self-Adaptive Inertia and Competition Mechanisms

During the simulation, the FLUS model updates an inertia coefficient for each land cover class to control its resistance to change. The inertia for class k at iteration t is adjusted according to the difference between the demand for class k given by the SD model and the area allocated to class k in the previous iteration [31]. When the allocated area is smaller than the demand, the inertia for that class is reduced, and conversion into that class becomes easier. When the allocated area exceeds the demand, the inertia is increased, and further expansion is discouraged. Through this process, the model gradually reduces the gap between macro-level land demand and micro-level CA allocation. The competition mechanism evaluates all land cover classes for each grid at the same time. In principle, each cell can change to any class that is not restricted by hard constraints, and the final class is chosen based on the combined transition probability. This setting reflects the fact that different land uses compete for the same locations [31].

2.5.3. Spatial Allocation and Scenario Integration

For each cell p and land cover class k at time t, the combined transition probability is written as in Equation (3).

Here, is the suitability term from the ANN, () is the neighborhood, is the inertia coefficient for class k, and is the conversion cost from the current class c to class k.

The model does not simply assign the class with the maximum value to each cell. Instead, it uses a roulette-style selection in which classes with higher values are more likely to be chosen, but other classes can still be selected with lower probabilities. This random draw introduces uncertainty into the allocation step and helps avoid overly rigid patterns.

Scenario information is passed to the FLUS model in two ways. First total land demand for each class changes with the SD results under each SSP-RCP scenario. Second, some of the driving variables used in the suitability maps also vary by scenario. Because of these two channels, the simulated spatial allocation differs across the SSP-RCP scenarios in line with their socioeconomic and climate conditions.

2.5.4. Parameter Settings

In this study, we did not add extra penalties for conversions that are allowed. For such transitions, the conversion cost was set to zero so that the term (1 − ) in Equation (3) becomes 1.

Transitions that are not allowed, for example, those inside hard constraint areas, were removed using exclusion masks instead of being assigned very high costs. Neighborhood weights were derived from the 2000–2020 LULC maps using a simple logistic regression.

For each of the 17 administrative regions and for each target class, we fitted a model in which the share of that class within a 7 × 7 neighborhood window was used as the main predictor. The estimated coefficients were then taken as class and region-specific neighborhood weights, and the same 7 × 7 window size was applied in all simulations. The full set of neighborhood weights for all regions is listed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Neighborhood weights (wₖ).

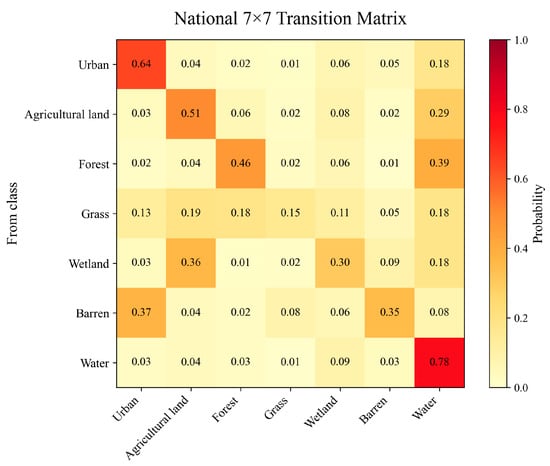

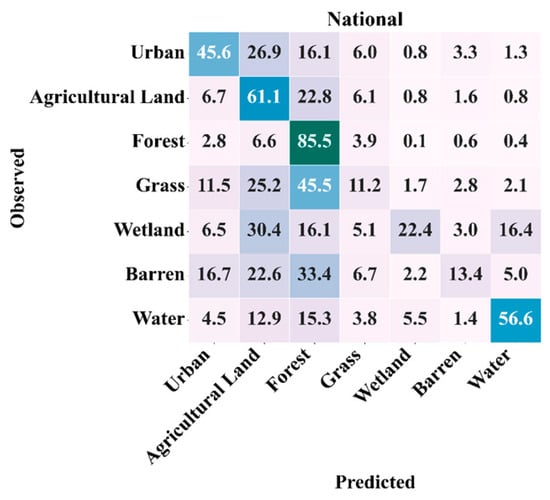

In addition, we constructed region-specific 7 × 7 transition probability matrices for all 17 administrative divisions using observed 2000–2020 LULC transitions. These empirically derived matrices were used both for diagnostic analysis and to inform the probability of land cover transitions in the FLUS spatial allocation. Figure 4 presents the aggregated national transition probability matrix for South Korea, while Supplementary Figures S1 and S2 show the region-specific matrices for each of the 17 administrative divisions.

Figure 4.

The 7 × 7 national transition matrix.

2.6. Model Validation and Accuracy Assessment

Model validation is the step in land use and land cover (LULC) modeling where we check whether the results can be trusted. It shows how close the simulations are to the observed patterns and gives a reference point when interpreting future projections or comparing model performance across regions and scenarios.

In this study model, performance is evaluated using the Figure of Merit FoM and the Kappa coefficient. FoM indicates how well the model identifies locations where land cover changed, while Kappa summarizes the overall agreement between the simulated and observed maps in a single value.

Validation Metrics and Formulations

The two metrics are complementary, and it is important to choose the appropriate accuracy assessment method based on their respective features. FoM is a metric that quantifies the agreement between the observed and predicted area of change, highlighting the accuracy of the area of change prediction. FoM is defined by the following formula.

where A represents error due to observed change predicted as persistence, B represents accuracy due to observed change predicted as change, C represents error due to observed change predicted as changing to an incorrect category, and D represents error due to observed persistence predicted as change. The FoM has a value between 0 and 1, with values closer to 1 indicating that the model accurately predicted the actual change. This can be a good metric to evaluate performance, especially for models that perform spatiotemporal change analysis [43].

The Kappa coefficient, on the other hand, is a quantitative measure of the agreement between the classified results and the actual observed results and can be used to evaluate accuracy by considering the probability of a random match. The Kappa coefficient is calculated as shown in the formula below.

where Po represents the observed agreement (overall accuracy), and Pe represents the expected agreement by chance. Kappa values range from −1 to 1. In general, a value of less than 0.20 indicates very poor agreement, 0.21 to 0.40 indicates fair agreement, 0.41 to 0.60 indicates moderate agreement, 0.61 to 0.80 indicates substantial agreement, and 0.81 or higher indicates near-perfect agreement [44].

3. Results

3.1. Land Cover Conversion Matrix Analysis

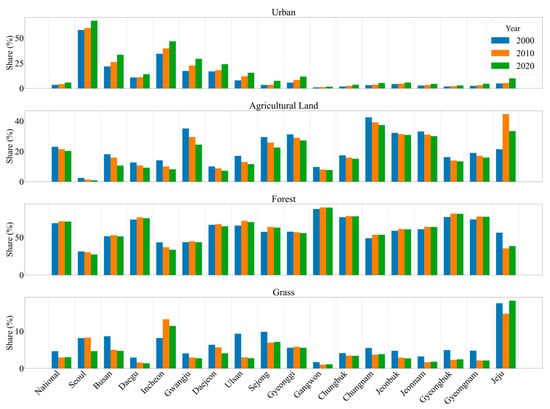

The national 7 × 7 conversion matrix for 2010–2020 is visualized in Figure 5 and shows that most new urban land comes from agricultural areas [45]. The most noticeable change in Korea is the conversion of farmland into urban land. This pattern was particularly pronounced around the metropolitan area, with 24.3% of farmland cells in Gyeonggi Province converted to urban land. Gwangju saw its urban area increase by 19.5%, while Busan, Seoul, and Daejeon also grew by 0.631%, 0.567%, and 0.500%, respectively. In rural regions like South Gyeongsang (14.6%), North Gyeongsang (12.8%), and Gangwon (7.4%), the increase in urban land was relatively smaller, yet the trend of agricultural land decline persists. Regional differences in urban expansion are also evident. While the metropolitan Seoul area as a whole saw steady growth in urban land, Gyeonggi Province had the largest increase in urbanized area, yet the increase in the proportion of urban land within its total land area was only 0.398%. The largest reductions in farmland occurred in Busan (−1.65%) and Gyeonggi Province (−0.95%), while Gangwon Province (−0.07%) and Gyeongbuk (−0.14%) maintained their farmland ratios at nearly the same levels. Over the period 2010–2020, the share of cells that kept the same land use class differed by region. Gangwon Province had the largest share of unchanged cells, which is consistent with its steep mountainous terrain and relatively weak development pressure. In Seoul and Busan, most cells in already urbanized districts did not change class, whereas in Gyeonggi Province, Gyeongnam, and Gyeongbuk, conversions between grassland and barren land occurred more often. Taken together, the conversion patterns suggest metropolitan cores that are close to saturation, additional urban growth spilling into neighboring regions, and farmland remaining mainly in upland and hill areas where development is less attractive.

Figure 5.

Temporal changes in the proportional shares of urban, agricultural land, forest, and grass across 17 administrative regions from 2000 to 2020. Each panel illustrates how the relative land cover composition has evolved at both the national and provincial scales.

3.2. National Projections and Regional Variations

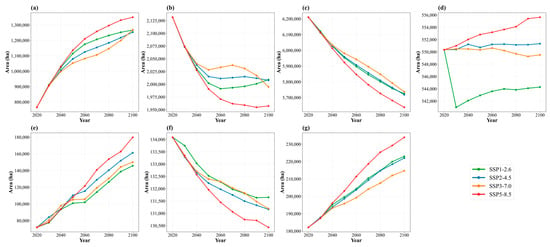

From 2020 to 2050, all four SSP-RCP scenarios show the same overall direction of change at the national scale (Figure 6). Urban land keeps expanding while agricultural and forest areas shrink. The strength of these trends depends on the scenario. SSP5-8.5 produces the largest urban increase at 584,555 ha, followed by SSP3-7.0, SSP1-2.6, and SSP2-4.5. Loss of agricultural land is also greatest under SSP5-8.5 at 174,133 ha and smallest under SSP2-4.5. Forest loss ranges from 473,174 ha in SSP3-7.0 to 571,682 ha in SSP5-8.5. Although the numbers differ, all scenarios point in the same direction. The volume of land that changes class each year reaches its maximum around 2030 and then declines, which suggests that development pressure gradually weakens across the SSPs.

Figure 6.

Projected changes by land cover type from 2020 to 2050 across four SSP-RCP scenarios: (a) urban, (b) agricultural land, (c) forest, (d) grassland, (e) wetland, (f) bare land, and (g) water.

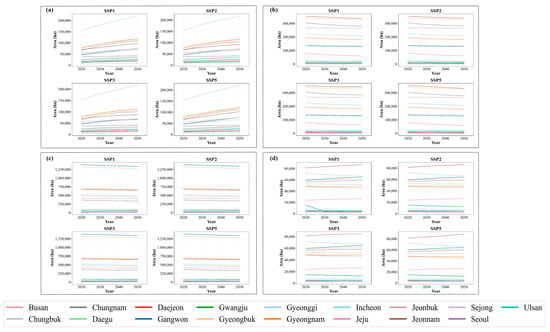

Regional results (Figure 7, Supplementary Table S1) show that these national trends play out very differently by province. Gyeonggi Province records the largest overall change by 2050, with 131,105 ha of new urban land and the strongest drop in agricultural area, so it acts as the focus of land conversion in the country. Large shifts also appear in Gyeongnam, Chungnam, and Gyeongbuk, where strong urban growth goes together with clear losses of farmland. In contrast, the metropolitan cities have less room to expand. Seoul gains only 10,328 ha of additional urban land, and Busan, Daegu, and Ulsan show moderate but steady increases rather than large jumps.

Figure 7.

Projected changes in major land cover types across the 17 administrative regions of Korea from 2020 to 2050 under four SSP-RCP scenarios. (a) Change in Urban; (b) Change in agricultural land; (c) Change in forest; (d) Change in grass. Each subpanel presents results for SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP3-7.0, and SSP5-8.5, respectively (scenario-specific land cover change tables and sensitivity indicators are available in the Supplementary Materials).

Provincial regions follow several distinct paths. In Gangwon, urban land grows by 40,742 ha, but this is accompanied by the largest forest loss in the country at 94,668 ha, which points to rising development pressure in mountain areas. Jeju Island shows a different picture. Their agricultural land drops by 34,178 ha, but forest cover increases by 20,408 ha, making Jeju the only region where forest area grows rather than shrinks under the projected scenarios.

These results collectively demonstrate a spatially uneven pattern of future land-cover change, characterized by metropolitan saturation, peri-urban expansion in adjacent provinces, and continued agricultural persistence in mountainous regions. Supplementary Table S1 further quantifies these regional differences, confirming that land use transitions in Korea through 2050 are strongly shaped by regional development capacity and policy context.

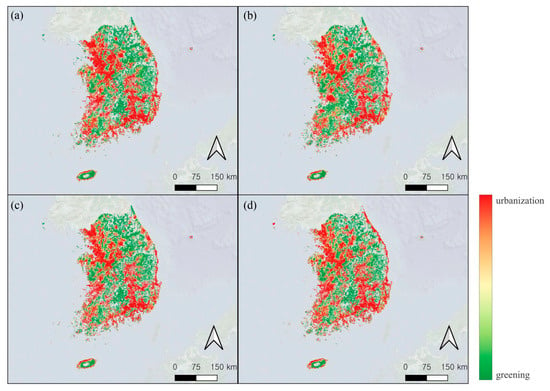

3.3. Scenario Sensitivity and Comparative Analysis

In Figure 8, urbanization and greening intensity for 2020–2050 are shown on a 1 km grid for the four SSP-RCP scenarios. If we only look at the country outline, the four maps seem to tell a similar story, but as soon as the 17 administrative regions are examined separately their shapes start to diverge. Around the Seoul capital region and along the southeastern industrial belt, dense clusters of new urban cells appear again and again under every scenario, while stronger green signals are mainly found on upland slopes and in sparsely populated farming districts. In other words, the same socioeconomic pathway pushes land use in different directions depending on local terrain and development pressure. Gyeonggi Province is a clear example of this pattern because across the four scenarios, its urban area grows by about 124,530–131,105 ha, and this growth is tied more closely to metropolitan demand than to the specific scenario choice. Gyeongnam shows a looser response with urban land increasing by 68,459–78,526 ha, and the upper end of that range occurring under SSP5-8.5. In already-dense cities such as Seoul, the additional change is modest at 8864–10,779 ha and appears in Figure 8 as a few compact red patches inside the existing urban belt. The sensitivity of agricultural land is even more uneven across regions. Jeollanam records the widest spread of farmland loss from 8509 to 29,233 ha, which matches the strong expansion of urban patches under SSP5-8.5 in that province. Many other regions show only small gaps between scenarios, so their green and red patterns in Figure 8 stay relatively similar. A closer look at the numbers shows how far SSP5-8.5 departs from SSP2-4.5. By 2050, SSP5-8.5 produces 96,575 ha more urban land than SSP2-4.5, almost twice the difference seen in other scenario pairs, and converts about 50,420 ha more farmland, most of it in provinces where agriculture still plays a major role rather than in the largest metropolitan cities. Forest area shrinks in all four settings from 473,174 ha in SSP3-7.0 to 571,682 ha in SSP5-8.5, a gap of 98,508 ha, suggesting that steep and forested terrain slows down development but does not completely stop it. Overall scenario-related uncertainty is strongest in fast-growing or agriculture-dependent regions, while many other areas change in broadly similar ways regardless of the pathway.

Figure 8.

Spatial patterns of urbanization intensity across South Korea’s 17 administrative regions from 2020 to 2050 under four SSP-RCP scenarios. Red indicates urbanization (conversion to urban areas) and green represents green (preservation or expansion of forests and agricultural lands). (a) SSP1-2.6; (b) SSP2-4.5; (c) SSP3-7.0; (d) SSP5-8.5.

3.4. Model Reliability Validation Results by Region

3.4.1. Figure of Merit (FoM) and Kappa Analysis Results

To evaluate the reliability of the FLUS model, a validation process was conducted by simulating the 2020 land cover based on the 2010 baseline and comparing the output with observed land cover data. This validation was carried out at the provincial level, and three performance metrics were used. The Kappa coefficient, FoM, and overall accuracy. Detailed results for each region are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Model reliability validation results by region.

The accuracy of provincial models across Korea exceeded 0.57, indicating that the FLUS model successfully captured the general pattern of land use changes nationwide. The Kappa coefficient ranged from 0.38 (Sejong, Gangwon) to 0.63 (Seoul), while the Figure of Merit (FoM) varied between 0.08 (Gangwon) and 0.17 (Jeju). In most regions, FoM values exceeded 0.10, demonstrating a clear advantage over random allocation and confirming meaningful predictive capability. Among metropolitan areas, Seoul achieved the highest Kappa coefficient (0.63) and overall accuracy (0.79), followed by Busan (0.61, accuracy 0.73) and Gwangju (0.57, accuracy 0.68). Conversely, Gangwon and Sejong recorded the lowest Kappa values (0.38), with Sejong also showing the lowest overall accuracy (0.57).

Regions with patchy or unusual land use change turned out to be the most difficult to reproduce. Jeju recorded the highest FoM value at 0.17, so the locations of simulated and observed change match reasonably well there. Gangwon showed the lowest FoM value at 0.08, which points to a much weaker spatial match. This outcome fits the basic characteristic of the province. Gangwon covers a large area; overall land cover conversion is rare, and strong variation in topography breaks the landscape into many separate pieces, so the model has fewer and more fragmented signals to learn from. When the 17 regions are grouped by administrative type, metropolitan cities such as Seoul, Busan, Daegu, Daejeon, and Gwangju reach an average Kappa of about 0.57, while provincial regions average roughly 0.46. Large urban areas also record the highest and lowest Kappa values at the regional scale. Jeju and other metropolitan regions follow relatively regular development paths and show compact clusters of land conversion. Gangwon sits at the other end of the range with a Kappa value of 0.38, where limited historical change, small, scattered pockets of new development, and steep terrain all work against the precise prediction of change locations. In practice, these patterns mean that FLUS tends to perform better in rapidly growing metropolitan regions than in areas that are either very stable or strongly shaped by complex mountain terrain.

3.4.2. Uncertainties and Implications

The validation results presented in Section 3.4.1, together with the confusion matrices in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3, provide the basis for assessing uncertainties in future land use projections. We identify three primary sources of uncertainty: model structure, regional heterogeneity, and scenario variability. Model structure uncertainty arises from the FoM values (0.08–0.17), which indicate that although the FLUS model reproduces the magnitude of land use change, its spatial precision remains limited. Consequently, predicted transition hotspots should be interpreted as probabilistic zones rather than exact locations. The 100 m resolution and 10-year validation interval further contribute to this uncertainty by smoothing fine-scale transitions and short-term dynamics (as shown in Figure 9).

Figure 9.

National confusion matrix for the 2010–2020 land cover validation. Values are row-normalized percentages of observed classes (rows) versus simulated classes (columns). Cell colors indicate the magnitude of percentage values, with darker shades representing higher values. Diagonal cells indicate correctly classified pixels. Full confusion matrices for the national and provincial models are provided in Supplementary Figures S3 and S4.

Regional heterogeneity in model performance introduces spatially differentiated uncertainty. Metropolitan areas (mean Kappa 0.57) show more reliable predictions than provincial regions (mean Kappa 0.46), with overall accuracies higher by roughly 12–15% age points. Gangwon (Kappa 0.38, FoM 0.08) exhibits the highest uncertainty because of limited historical change, irregular development patterns, and complex topography, whereas Seoul (Kappa 0.63, accuracy 0.79) and Busan (Kappa 0.61, accuracy 0.73) show greater predictive reliability that reflects more structured urban development. Scenario variability represents uncertainty in future socioeconomic and climate pathways. Across the four SSP-RCP scenarios, projected urban expansion ranges from 488,000 ha (SSP2-4.5) to 585,000 ha (SSP5-8.5), agricultural land loss from 124,000 ha to 174,000 ha, and forest decline from 473,000 ha to 572,000 ha, indicating the influence of alternative demographic, economic, and climate trajectories. Taken together, these uncertainties imply that projections for rapidly urbanizing metropolitan regions are more reliable than those for topographically complex or slowly changing areas. Policy applications should therefore treat metropolitan forecasts as relatively precise while adopting wider uncertainty margins and adaptive strategies for provincial planning, particularly during the 2020–2040 period when most projected changes occur, and policy interventions can most strongly alter future trajectories.

4. Discussion

This study employed the FLUS model to simulate land use and land-cover (LULC) changes in Korea under four SSP-RCP scenarios, revealing distinct temporal and spatial transformation pathways. Unlike previous national-scale studies that applied uniform parameters, this research independently calibrated conversion matrices for each of the 17 administrative units, thereby incorporating regional heterogeneity in land use dynamics. For example, Gangwon, where approximately 70% of the land is mountainous, exhibited a high probability of urban conversion (0.534) despite limited developable areas, whereas Seoul, already highly urbanized, showed near-complete conversion of its remaining agricultural land (probability 1.0). Jeju Island recorded the lowest conversion probabilities (0.121–0.214) across all land use types, reflecting its conservation-oriented development policies. By 2050, the SSP5-8.5 scenario projected the most extensive urban expansion, followed by SSP3-7.0, SSP1-2.6, and SSP2-4.5. The approximately 20% difference between SSP5-8.5 and SSP2-4.5 underscores the critical influence of socioeconomic pathways on future urban sustainability [46,47].

This study also represents the first national-scale application of the integrated FLUS-SD framework in Korea with region-specific parameter adjustments for all 17 administrative units. This localized approach allows the model to capture differences in industrial structure, demographic trends, land availability, and climate sensitivity, thereby enhancing its ability to reflect real development constraints. The resulting methodological framework provides a robust basis for policy-oriented scenario analysis and supports differentiated land use strategies across multiple spatial governance levels. Taken together, these region-specific parameter adjustments provide a more realistic representation of Korea’s spatial development constraints and create a modeling environment in which scenario-driven differences can be evaluated with greater clarity.

4.1. Diverse LULC Change Patterns and Implications

The LULC outcomes in this study differ in several ways from patterns reported in many international SSP-based analyses [45]. In our simulations, SSP5-8.5 still leads to the largest gain in urban area and the greatest loss of farmland, yet SSP1-2.6 and SSP3-7.0 end up very close to one another in terms of overall land demand. This near overlap seems to reflect the South Korean setting rather than the scenario framework itself. Population density is already high at roughly 527 persons/km2, and about 70% of the national territory is mountainous, while the share of residents in urban areas has reached 81.4%. Under these conditions, there is limited physical space left for new development, so different policy pathways can push against almost the same capacity ceiling. As a result, physical constraints become a dominant force in shaping land use trajectories, and the contrast between scenarios is partly flattened. This behavior differs from that of countries with extensive land reserves, where SSP5-8.5 typically produces clearly stronger urban expansion than the other scenarios [45,48].

Viewed together, these results show that land use outcomes in the Republic of Korea arise from the way three forces interact [49]. Spatial limits set the outer frame for change. Policy choices then decide which locations feel pressure first. The underlying terrain finally channels where transitions can take place. The timing of change is also uneven. Early decades show strong transformation, and later decades slow down, which matches the projected shift in population and economic structure after 2040. Between 2020 and 2040, the national population falls each year at rates between minus 0.22 and minus 0.33% across the scenarios. Over the same interval, gross domestic product GDP still grows and reaches 38.53% in SSP3-7.0 and 62.01% in SSP5-8.5. After 2040, the population decline almost doubles with annual rates between minus 0.44 and minus 0.71% and GDP growth drops to 11.64% in SSP5-8.5 and minus 9.36% in SSP3-7.0 [50]. Around 2040, the shrinking working age population therefore begins to act as a direct brake on economic expansion. As demographic decline speeds up and growth weakens, the main drivers of land use change move away from straightforward outward expansion and shift toward internal adjustment and reallocation.

Because of this dynamic, the decades before roughly 2040 form a key period for managing the spread of urban land. Decisions taken in that window are likely to shape the later pattern of urban areas. The spatial and temporal results together point to a simple conclusion. Land use change in South Korea depends not only on the amount of open land that remains but also on public policy and wider socioeconomic trends [51,52]. Linking SSP-RCP narratives with the FLUS model makes it possible to trace several socioeconomic pathways and their associated climate futures within a single set of experiments. In our runs, the SSP settings mainly controlled how much urban land was added and where this growth occurred. The RCP-based climate projections added another layer through changes in temperature and precipitation. These signals affect crop yields, forest resilience, and the suitability of land for further development. When these climate-related shifts are read together with the socioeconomic pathways, the scenario set becomes a practical tool for comparing policy options and for addressing both development pressure and climate adaptation goals.

FLUS also includes adaptive inertia and competition rules that influence how cells change state. These rules help connect top-down estimates of land demand with bottom-up spatial allocation by strengthening or weakening transition pressure during each step of the simulation. That feature mattered in this study because land use demands from the System Dynamics model had to be spread across space under several SSP-RCP scenarios while still respecting regional development limits and existing policy restrictions. At the same time, FLUS shares a limitation that is common to many cellular automata approaches. The Figure of Merit values obtained here, which range between 0.07 and 0.17, show that the model still struggles to predict the exact grid cells where change will occur, especially in areas with rugged topography or relatively slow rates of transition.

4.2. Policy Applications and Sustainable Development Strategies

Across all SSP-RCP scenarios, the land use outlook for South Korea shows the same broad tendency. Urban areas continue to grow while cultivated land, forests, and wetlands lose area over time. This pattern suggests that keeping nature-based land uses in place will require planning that is more deliberate and systematic than the management of urban growth, which is mainly driven by demographic and economic pressures. As forest, farmland, and wetland areas shrink, the flow of ecosystem services is reduced as well, so the projections make clear that spatial strategies need to be designed in explicit connection with national sustainability objectives.

The expected scale of forest loss fits poorly with Korea’s climate mitigation pledges. While national strategies such as the 2030 Nationally Determined Contribution NDC and the 2050 Carbon Neutrality Roadmap assume that forest carbon absorption will stay at least stable or even increase, the modeled reductions of 473 174 ha under SSP3-7.0 and 571 682 ha under SSP5-8.5 point to a clear decline in sequestration capacity. This study does not explicitly simulate carbon fluxes, but the magnitude of forest area loss alone indicates that sector-specific reduction targets will be difficult to achieve if policy relies mainly on reforestation programs or technological removal options. The results, therefore, suggest that stronger measures to conserve existing forests are required, including tighter land use regulation in high-pressure regions such as Gyeonggi and an expansion of forest conservation zones within the national mitigation framework.

Losses of agricultural land, especially in Chungnam, Gyeonggi, and Jeonnam, intersect with South Korea’s food security goals and with recently introduced farmland protection schemes, including the Rural Revitalization and Structural Adjustment Act. The spatial projections produced in this study help to single out farmland that should be treated as a preservation priority. Rather than pointing to one preferred policy instrument, the findings underline the importance of coordinating agricultural zoning, urban growth boundaries, and municipal land use plans so that vulnerable farmland areas can maintain their functional continuity.

The results reveal a structural tension between the projected land use trajectories and the goals that South Korea has pledged under the Paris Agreement. The Framework Act on Carbon Neutrality and Green Growth, enacted in 2021, gives legal force to Korea’s commitment to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 and to reduce national greenhouse gas emissions by 40% below 2018 levels by 2030 as specified in the NDC. However, projected forest losses of 473,000–572,000 ha could weaken the assumed annual carbon uptake of roughly 26 million tons of CO2, and modeled reductions of 124,000–174,000 ha of farmland may jeopardize efforts to maintain 1.5 million hectares of cultivated land and to reach a food self-sufficiency rate of 55.5% by 2027. These spatial mismatches suggest that existing policy frameworks, including the National Land Planning and Utilization Act, the Rural Revitalization and Structural Adjustment Act, and the 2050 Carbon Neutrality Roadmap, need to be recalibrated so that land use planning more explicitly integrates climate mitigation and food security objectives through stronger forest conservation zoning expanded incentives for farmland preservation and the incorporation of scenario based monitoring into national mitigation strategies.

4.3. Limitations and Suggestions

Although this study provides several perspectives on future land use in South Korea, it also has important limitations. First, the resolution and accuracy of the input data may restrict what the model can capture. The FLUS model becomes less effective at representing fine-scale land use change when it is applied at relatively coarse spatial resolutions [53,54]. In this study, the simulations relied on 100 m land cover data, so transitions that occur at the parcel scale may be smoothed out. Using land cover products with finer resolution than those currently available would make it possible to test the model at a more detailed level.

Moreover, while the analysis incorporated macro-level socioeconomic indicators, micro-level drivers such as land ownership patterns and parcel-based development plans were not explicitly represented [53], which limits the ability to reproduce site-specific transitions. This limitation is particularly evident in metropolitan infill zones and rural urban fringes, where parcel-level decisions strongly influence local transition probabilities.

Second, the SSP-RCP framework used in this study makes it possible to compare broad scenario-dependent differences in future land use, but it does not describe the effects of individual policy instruments in detail [55]. The current setup cannot directly evaluate how specific measures, such as changes in zoning rules, urban forest expansion programs, or carbon neutrality strategies, would alter spatial outcomes. Future work should therefore combine the FLUS model with targeted policy simulation modules so that the quantitative impacts of development policies or environmental regulations can be assessed more explicitly, for example, by simulating alternative urban forest expansion or carbon neutrality strategies [31]. Such extensions would increase the practical usefulness of FLUS-based projections for policy making.

Third, the climate inputs were derived from high-quality projections produced by NanoWeather Inc. using the HadGEM3 RA regional climate model and the Quantitative Topographic Model QTM for downscaling [38]. However, the proprietary nature of the downscaling procedure limits full reproducibility. Comparative experiments that use publicly available climate datasets such as WorldClim or CHELSA would improve methodological transparency and make it possible to evaluate how sensitive the results are to alternative climate inputs. This is especially important because temperature-related coefficients had a strong influence on agricultural wetland and forest transitions in this study.

Model performance also reflects several structural data constraints. Aggregating the original 30 m land cover maps to a 100 m grid inevitably blurs fine-scale transition patterns in South Korea’s highly fragmented landscape and contributes to relatively low FoM values, indicating that the model cannot precisely reproduce the exact locations of change [43,56]. In addition, classification inconsistencies between the 2010 and 2020 maps may further depress FoM scores. A validation interval of 10 years can miss short-term changes, and the omission of local-scale drivers such as detailed zoning regulations or site-specific development plans reduces predictive accuracy in mixed-use peri-urban areas, so that some transition hotspots are likely underrepresented in the current projections [44].

Finally, the analysis was constrained by the availability of national-scale land cover datasets. Because of the division of the Korean Peninsula, only the southern part of the peninsula could be included, and only the 2010 and 2020 land cover maps were available for calibration and validation. This limited the temporal depth of the dataset and restricted the ability to examine longer historical trajectories of land use change.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we linked four SSP-RCP scenarios with the FLUS model to explore long-term trajectories of land use and land cover (LULC) in South Korea. The framework was applied to each of the 17 first-tier administrative regions so that regional patterns could be examined in their own context. Results from the four scenario experiments show that development pressures and land demand are not uniform across the country, and they suggest that each region will require its own mix of policy responses.

Across all four scenarios, urban areas continue to expand while agricultural and forest land contract, and the most intense changes are projected for the period between 2020 and 2040. This timing suggests that spatial policy choices made in that window can strongly reshape the later structure of the national landscape.

The four SSP-RCP combinations also do not merge into a single pathway. Each scenario assumes its own pattern of demographic change, pace of economic growth, strength of governance, and priority given to environmental protection, so the locations and intensity of development pressure at the national scale differ across scenarios.

This indicates that even under the same physical setting, the long-term land use pattern of South Korea can diverge sharply depending on which socioeconomic path is followed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land14122380/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K. and S.H.; Methodology, S.H., M.A., and T.K.; Investigation, H.J. and S.H.; Software, H.J., S.H., and M.A.; Validation, S.S. and H.J.; Formal analysis, H.J., S.H., and T.K.; Data curation, S.S.; Writing—original draft preparation, S.H.; Writing—review and editing, Y.K. and T.K.; Visualization, S.H.; Supervision, Y.K.; Funding acquisition, Y.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute through the “Climate Change R&D Project for New Climate Regime” funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (2022003570008).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank MUREPA KOREA for providing the socioeconomic data and Nano Weather Inc. for providing the climate data used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Li, X.; Yu, L.; Chen, X. New Insights into Urbanization Based on Global Mapping and Analysis of Human Settlements in the Rural-Urban Continuum. Land 2023, 12, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Carvajal-Lara, C.; Urgilés-Sanchez, R.; Ruano, M.A. Deforestation as an Indicator of Environmental Degradation: Analysis of Five European Countries. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 90, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, A.N.T.; Tran, H.D.; Ashley, M.; Nguyen, A.T. Monitoring Landscape Fragmentation and Aboveground Biomass Estimation in Can Gio Mangrove Biosphere Reserve over the Past 20 Years. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 70, 101743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gong, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Ning, G.; Xu, B. Production of Global Daily Seamless Data Cubes and Quantification of Global Land Cover Change from 1985 to 2020—IMap World 1.0. Remote Sens. Environ. 2021, 258, 112364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Yang, H.; Zhong, T. Environmental Effects of Land-Use/Cover Change Caused by Urbanization and Policies in Southwest China Karst Area—A Case Study of Guiyang. Habitat. Int. 2014, 44, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muriithi, F.K. Land Use and Land Cover (LULC) Changes in Semi-Arid Sub-Watersheds of Laikipia and Athi River Basins, Kenya, as Influenced by Expanding Intensive Commercial Horticulture. Remote Sens. Appl. 2016, 3, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Park, K. Temperature Trend Analysis Associated with Land-Cover Changes Using Time-Series Data (1980–2019) from 38 Weather Stations in South Korea. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 65, 102615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidoo, R.; Arko-Adjei, A.; Poku-Boansi, M.; Quaye-Ballard, J.A.; Somuah, D.P. Land Use and Land Cover Changes Implications on Biodiversity in the Owabi Catchment of Atwima Nwabiagya North District, Ghana. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y.; Yang, G.; Zhen, W. Relating Land-Use/Land-Cover Patterns to Water Quality in Watersheds Based on the Structural Equation Modeling. Catena 2021, 206, 105566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarin, T.; Esraz-Ul-Zannat, M. Assessing the Potential Impacts of LULC Change on Urban Air Quality in Dhaka City. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoke, T.; Elsasser, P.; Kindu, M. Considering the Land-Cover Elasticity of Ecosystem Service Value Coefficients Improves Assessments of Large Land-Use Changes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 68, 101645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerici, N.; Cote-Navarro, F.; Escobedo, F.J.; Rubiano, K.; Villegas, J.C. Spatio-Temporal and Cumulative Effects of Land Use-Land Cover and Climate Change on Two Ecosystem Services in the Colombian Andes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 685, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanapathi, T.; Thatikonda, S. Investigating the Impact of Climate and Land-Use Land Cover Changes on Hydrological Predictions over the Krishna River Basin under Present and Future Scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Peng, S.; Ma, D.; Shi, S.; Zhu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Gong, L.; Huang, B. Patterns of Change, Driving Forces and Future Simulation of LULC in the Fuxian Lake Basin Based on the IM-RF-Markov-PLUS Framework. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolentino, F.M.; de Lourdes Bueno Trindade Galo, M. Selecting Features for LULC Simultaneous Classification of Ambiguous Classes by Artificial Neural Network. Remote Sens. Appl. 2021, 24, 100616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Wu, C.C.; Tsogt, K.; Ouyang, Y.C.; Chang, C.I. Effects of Atmospheric Correction and Pansharpening on LULC Classification Accuracy Using WorldView-2 Imagery. Inf. Process. Agric. 2015, 2, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, N.; Li, C.; Luan, J. Contrasting Effects of Climate and LULC Change on Blue Water Resources at Varying Temporal and Spatial Scales. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Sun, L. Response of Spatial and Temporal Variations of Ecosystem Service Value to Land Use/Land Cover Transformation in the Upper Basin of Miyun Reservoir. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Hou, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Hu, T. Future Urban Waterlogging Simulation Based on LULC Forecast Model: A Case Study in Haining City, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Guan, Q.; Lin, J.; Luo, H.; Tan, Z.; Ma, Y. Simulating Land Use/Land Cover Change in an Arid Region with the Coupling Models. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 122, 107231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.; Guan, Q.; Lin, J.; Yang, L.; Luo, H.; Ma, Y.; Tian, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, N. The Response and Simulation of Ecosystem Services Value to Land Use/Land Cover in an Oasis, Northwest China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisi Nabikandi, B.; Shahbazi, F.; Hami, A.; Malone, B. Exploring Carbon Storage and Sequestration as Affected by Land Use/Land Cover Changes toward Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Soil Adv. 2024, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximus, J.K. Assessing Watershed Vulnerability to Erosion and Sedimentation: Integrating DEM and LULC Data in Guyana’s Diverse Landscapes. HydroResearch 2025, 8, 178–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghalehteimouri, K.J.; Ros, F.C.; Rambat, S. Flood Risk Assessment through Rapid Urbanization LULC Change with Destruction of Urban Green Infrastructures Based on NASA Landsat Time Series Data: A Case of Study Kuala Lumpur between 1990–2021. Ecol. Front. 2024, 44, 289–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foteck Fonji, S.; Taff, G.N. Using Satellite Data to Monitor Land-Use Land-Cover Change in North-Eastern Latvia. SpringerPlus 2014, 3, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varga, K.; Szabó, S.; Szabó, G.; Dévai, G.; Tóthmérész, B. Improved Land Cover Mapping Using Aerial Photographs and Satellite Images. Open Geosci. 2015, 7, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Song, P.; Hu, X.; Chen, C.; Wei, B.; Zhao, S. Coupled Effects of Land Use and Climate Change on Water Supply in SSP-RCP Scenarios: A Case Study of the Ganjiang River Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 154, 110745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Wang, X. What Is the Future of Ecological Space in Wuhan Metropolitan Area? A Multi-Scenario Simulation Based on Markov-FLUS. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 141, 109124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, X.; Fu, Y. Multi-Scenario Simulation of Low-Carbon Land Use Based on the SD-FLUS Model in Changsha, China. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santé, I.; García, A.M.; Miranda, D.; Crecente, R. Cellular Automata Models for the Simulation of Real-World Urban Processes: A Review and Analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 96, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Liang, X.; Li, X.; Xu, X.; Ou, J.; Chen, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Pei, F. A Future Land Use Simulation Model (FLUS) for Simulating Multiple Land Use Scenarios by Coupling Human and Natural Effects. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 168, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Shen, H.; Shi, Q. Multimodal Registration of Remotely Sensed Images Based on Jeffrey’s Divergence. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 122, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, C.; Liu, R.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Q. Comparison of Various Models for Multi-Scenario Simulation of Land Use/Land Cover to Predict Ecosystem Service Value: A Case Study of Harbin-Changchun Urban Agglomeration, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 144012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, D.; Ren, Y.; Li, K. Construction of the Green Infrastructure Network for Adaption to the Sustainable Future Urban Sprawl: A Case Study of Lanzhou City, Gansu Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 145, 109715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegler, E.; O’Neill, B.C.; Hallegatte, S.; Kram, T.; Lempert, R.J.; Moss, R.H.; Wilbanks, T. The Need for and Use of Socio-Economic Scenarios for Climate Change Analysis: A New Approach Based on Shared Socio-Economic Pathways. Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 807–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Kriegler, E.; Riahi, K.; Ebi, K.L.; Hallegatte, S.; Carter, T.R.; Mathur, R.; van Vuuren, D.P. A New Scenario Framework for Climate Change Research: The Concept of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Clim. Change 2014, 122, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Teng, Y.; Li, J.; Yan, Y.; Zhao, C.; Li, Y.; Li, X. A New Assessment Framework to Forecast Land Use and Carbon Storage under Different SSP-RCP Scenarios in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, T.; Nakajo, Y. Composite Composition Comprising Inorganic Oxide Particles and Silicone Resin and Method of Producing Same, and Transparent Composite and Method of Producing Same. WO202500100841A1, 12 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.; O’Neill, B.C. Spatially Explicit Global Population Scenarios Consistent with the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 084003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoraghein, H.; O’Neill, B.C. U.S. State-Level Projections of the Spatial Distribution of Population Consistent with Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Alam, M.T.; Mojumder, P.; Mondal, I.; Kafy, A.-A.; Dutta, M.; Ferdous, M.N.; Al Mamun, M.A.; Mahtab, S.B. Dynamic Assessment and Prediction of Land Use Alterations Influence on Ecosystem Service Value: A Pathway to Environmental Sustainability. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 21, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Zhao, K. Dynamic Simulation and Projection of Land Use Change Using System Dynamics Model in the Chinese Tianshan Mountainous Region, Central Asia. Ecol. Model. 2024, 487, 110564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontius, R.G.; Boersma, W.; Castella, J.C.; Clarke, K.; Nijs, T.; Dietzel, C.; Duan, Z.; Fotsing, E.; Goldstein, N.; Kok, K.; et al. Comparing the Input, Output, and Validation Maps for Several Models of Land Change. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2008, 42, 11–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, Y.; Liang, X.; Leng, J.; Xu, X.; Liao, W.; Qiu, Y.; Wu, Q.; et al. Global Projections of Future Urban Land Expansion under Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Han, Y.; Zhang, L.; Han, Z. Dynamic Evolution of Land Use/Land Cover and Its Socioeconomic Driving Forces in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; O’Neill, B.C. Mapping Global Urban Land for the 21st Century with Data-Driven Simulations and Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, P.; Xia, J.; Wang, W.; Cai, W.; Chen, N.; Hu, S.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Zhan, C. Land Use/Land Cover Prediction and Analysis of the Middle Reaches of the Yangtze River under Different Scenarios. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, T.; Divigalpitiya, P.; Arima, T. Driving Factors of Urban Sprawl in Giza Governorate of Greater Cairo Metropolitan Region Using AHP Method. Land Use Policy 2016, 58, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, D.; Schalliol, D. Testing the Temporal Nature of Social Disorder through Abandoned Buildings and Interstitial Spaces. Soc. Sci. Res. 2015, 54, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegler, E.; Edmonds, J.; Hallegatte, S.; Ebi, K.L.; Kram, T.; Riahi, K.; Winkler, H.; van Vuuren, D.P. A New Scenario Framework for Climate Change Research: The Concept of Shared Climate Policy Assumptions. Clim. Change 2014, 122, 401–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, X.; van Vliet, J.; Zhou, T.; Verburg, P.H.; Zheng, W.; Liu, X. Direct and Indirect Loss of Natural Habitat Due to Urban Area Expansion: A Model-Based Analysis for the City of Wuhan, China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 231–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marey, A.; Wang, L.; Goubran, S.; Gaur, A.; Lu, H.; Leroyer, S.; Belair, S. Forecasting Urban Land Use Dynamics Through Patch-Generating Land Use Simulation and Markov Chain Integration: A Multi-Scenario Predictive Framework. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volk, R.; Rambhia, M.; Naber, E.; Schultmann, F. Urban Resource Assessment, Management, and Planning Tools for Land, Ecosystems, Urban Climate, Water, and Materials—A Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umwali, E.D.; Chen, X.; Ma, X.; Guo, Z.; Mbigi, D.; Zhang, Z.; Umugwaneza, A.; Gasirabo, A.; Umuhoza, J. Integrated SSP-RCP Scenarios for Modeling the Impacts of Climate Change and Land Use on Ecosystem Services in East Africa. Ecol. Model. 2025, 504, 111092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Hu, G.; Chen, G.; Liu, X.; Hou, H.; Li, X. 1 km land use/land cover change of China under comprehensive socioeconomic and climate scenarios for 2020–2100. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).