Abstract

Exploring the spatiotemporal patterns of cultivated land conversion to non-agricultural uses and their evolutionary driving mechanisms is of significant importance for regional cultivated land protection and food security. This study utilizes time-series land use datasets, DEM, meteorological data, and statistical yearbook data to construct an assessment model for the rate of cultivated land conversion to non-agricultural uses. Based on this model, the study conducts spatial autocorrelation analysis and locational gradient analysis to systematically investigate the characteristics and driving mechanisms of cultivated land conversion to non-agricultural uses in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023. The study revealed several key findings: (1). The total area of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province has demonstrated a trend of ‘initial continuous decline followed by a slight recovery after 2015.’ Spatially, it exhibits a distribution pattern characterized by ‘continuous reduction around urban areas, with relative stability in the northern core regions’. (2). The temporal pattern of cultivated land conversion to non-agricultural use in Jiangsu Province follows a trajectory of ‘rapid expansion (2000–2015) followed by a gradual slowdown (2015–2023),’ with significant gradient differences observed spatially (‘Southern Jiangsu > Central Jiangsu > Northern Jiangsu’). (3). The conversion of cultivated land to non-agricultural use in Jiangsu Province results from the combined effects of natural constraints, socio-economic driving factors, and agricultural policies. Topographical constraints and urban radiation have emerged as the primary spatial conditions promoting non-agriculturalization, with urban expansion identified as the most direct driving factor of cultivated land conversion in recent years. Conversely, agricultural factors have exerted a relatively weaker influence on non-agriculturalization. These research findings provide a significant scientific basis for formulating differentiated cultivated land protection policies across the province, thereby assisting in achieving a balance between food security and coordinated urban–rural development.

1. Introduction

Cultivated land serves as the foundation for human survival, development, and prosperity, while also playing an irreplaceable role in carbon sequestration, emission reduction, soil and water conservation, and biodiversity maintenance [1]. Furthermore, it is a critical material condition for sustaining ecological balance, ensuring food security, promoting economic development, and maintaining social stability [2]. As urbanization and industrialization progress, the urban population continues to grow, leading to an increasing demand for construction and living space, which exerts greater pressure on limited arable land resources [3]. The global arable land resources have undergone significant changes, accompanied by increasingly prominent environmental challenges. Over the past two decades, the global arable land area has increased at a net rate of 19,000 square kilometers per year, with developing countries experiencing notable transformations in arable land resources, alongside environmental issues such as carbon emissions and biodiversity loss [4]. The conflict between economic development and arable land resources is becoming increasingly pronounced, highlighting the urgent need for a quantitative analysis of changes in arable land use. This analysis should identify the driving mechanisms behind current changes in arable land use and subsequently construct targeted and sustainable arable land protection models to balance food production with ecological security, thereby addressing the challenges posed by resource depletion and environmental risks [5].

To achieve the “dual carbon” goal and the strategic objective of ecological civilization construction, the Chinese government has explicitly proposed to “comprehensively consolidate the foundation of food security,” while emphasizing the “safeguarding of the red line of arable land” [6]. This highlights the core importance of arable land protection within the national security framework. The key to safeguarding arable land lies in a real-time and accurate understanding of its dynamic changes. Research indicates that the net cultivated land area in China increased by only 0.4% from 1990 to 2019; however, the changes in land use were significant [4], particularly in economically developing regions such as the Huang Huai Hai Plain and the Middle and Lower Yangtze Valley Plain, where cultivated land areas have decreased markedly [7,8,9]. The protection of arable land is closely linked to the dual strategy of ensuring national food security and ecological security. To address this challenge, in 2021, the Ministry of Natural Resources, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, and the State Forestry and Grassland Administration of China jointly issued a notice enforcing strict control over arable land use, aiming to curb the “non-agriculturalization” of arable land and resolutely uphold the red line of arable land. Broadly speaking, the non-agricultural use of arable land refers to the conversion of arable land into non-agricultural production land, leading to changes in land use types. This manifests as a reduction in both arable land and the total area of agricultural land [10]. The non-agriculturalization of arable land not only results in a significant decline in high-quality arable land resources but may also threaten food security, exacerbate ecosystem imbalances, and pose potential risks to regional sustainable development [11].

The core contradiction in the conversion of cultivated land to non-agricultural uses—specifically the spatial competition between cultivated land protection and urbanization/industrialization—is a universally observed phenomenon worldwide. In Asia, emerging economies such as Pakistan and Vietnam are grappling with increasingly prominent issues of cultivated land being converted to industrial and urban construction land, driven by rapid industrialization and population agglomeration. Relevant studies have focused on policy regulation and the food security crises arising from such conversion [12,13,14]. In South America, under the dual impetus of large-scale agricultural operations and urban expansion, the conversion between cultivated land and other land types exhibits characteristics of “large scale and high intensity,” with scholars paying greater attention to the coordinated governance of ecological protection and economic development transformation [15,16]. These international studies offer diverse perspectives for understanding the driving logic and regulatory pathways of cultivated land conversion to non-agricultural uses. However, given the variations in natural endowments, development stages, and institutional environments across different countries, targeted research tailored to specific regions remains essential. As one of the countries facing the most severe pressure regarding cultivated land protection globally, China finds in Jiangsu Province—a region with distinct developmental heterogeneities across its three major sub-regions—a typical case for analyzing the evolutionary patterns of cultivated land conversion to non-agricultural uses at different stages of development. The findings of this research can thus serve as a reference for similar regions both domestically and internationally.

The existing research on the non-agricultural conversion of cultivated land primarily focuses on the characteristics of large-scale spatiotemporal changes and the analysis of the influencing factors related to this conversion [17]. The non-agriculturalization process of cultivated land in China has exhibited distinct characteristics over different time periods; however, the overall trend is moving towards stability or a slowdown, undergoing a phase of “growth stability” [18,19,20,21,22,23]. From 1990 to 2020, China’s arable land area decreased by 4.43%, with an average annual reduction of 3353.20 km2 [19]. The non-agricultural utilization of arable land has been significantly influenced by the expansion of built-up areas, displaying a distribution pattern centered around urban areas, gradually spreading outward and diminishing towards the periphery [20]. The reduction in arable land in China is predominantly concentrated in the coastal regions east of the Hu Huanyong Line and certain inland areas, particularly within developed regions such as Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Delta [21]. Zhang et al. employed standard deviation ellipse and trend analysis to estimate the dynamic evolution characteristics of non-agriculturalization and non-grainization, developed a comprehensive indicator system for both processes, and constructed a partial correlation model to quantify the relative contributions of each influencing factor [22].

In analyzing the factors influencing non-agricultural transformation, the primary methods employed include interpretable machine learning models [24], geographic detectors [25], and geographically weighted regression models [26]. Zhang et al. utilized an interpretable machine learning model to elucidate the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of non-agricultural land use and its influencing factors across three representative regions in China (Jilin, Henan, and the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area) from 2000 to 2020 [24]. Their findings indicate that while socio-economic factors predominantly influence non-agricultural land use, natural factors such as altitude and slope also play a significant role. These natural factors not only directly affect land availability and suitability but also interact with socio-economic factors, collectively shaping the trends and patterns of non-agricultural land use. Additionally, Peng et al. employed techniques such as single land use dynamics and geographic information mapping to uncover the characteristics and spatiotemporal evolution patterns of land use transformation in Putian City, China, over the past two decades [27]. Xu et al. analyzed land use datasets from multiple periods between 2000 and 2023, employing analytical tools such as non-parametric kernel density estimation (KDE) and the optimal parameter geodetector model (OPGD) to investigate the dynamic evolution and potential driving forces of non-agricultural land use change (NACCL) across 183 counties in Sichuan Province through both temporal and spatial dimensions [28].

As a crucial grain production base and industrial province in China, Jiangsu Province bears significant responsibilities in ensuring national food security and fostering economic development. The rapid urbanization and industrialization processes have posed severe challenges to arable land resources. This economic growth and urbanization have intensified the imbalance between land supply and demand in the region [29]. From 2000 to 2023, the cultivated land area in the province decreased from 77,738 km2 to 70,662 km2, resulting in a cumulative non-agricultural area of 9739 km2 and a non-agricultural rate of 13%. The non-agricultural rate exhibited considerable fluctuations over different periods: from 2010 to 2015, it peaked at 4.83%, the highest rate recorded, but subsequently declined to 1.36% from 2020 to 2023, reflecting the phased effects and pressures of cultivated land protection policies. Nevertheless, the spatial differentiation and driving mechanisms behind the phenomenon of cultivated land non-agricultural use remain unclear. Therefore, an in-depth analysis of the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics, spatial agglomeration patterns, and regional differences in non-agricultural land use in Jiangsu Province, along with an exploration of the spatiotemporal patterns and driving mechanisms of non-agricultural land use, is of great significance for formulating differentiated agricultural land protection policies throughout the province and achieving regional dual carbon goals [30].

To address the aforementioned issues, this study makes the following main contributions: (1) Integrating multi-source data including long-time-series land use datasets (2000–2023), DEM, meteorological data, and statistical yearbooks, a comprehensive evaluation framework for the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land rate covering the Jiangsu Province is constructed; (2) Spatial autocorrelation analysis (Moran’s I) and locational gradient analysis are systematically employed to accurately explore the spatiotemporal evolution patterns of non-agriculturalization in Jiangsu Province; (3) Multi-scale driving factor analysis is conducted to examine the differences in characteristics of non-agriculturalization between Jiangsu Province as a whole and its three major regions (Southern Jiangsu, Central Jiangsu, and Northern Jiangsu), enhancing the comprehensiveness and targeting of the analysis on regional differential patterns.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents a review of the Study area and materials. Section 3 introduces the methods. Section 4 presents the analysis results of cultivated land non-agriculturalization. Section 5 presents the discussion and future policy recommendations. Finally, Section 6 provides the conclusion.

2. Study Area and Materials

2.1. Study Area

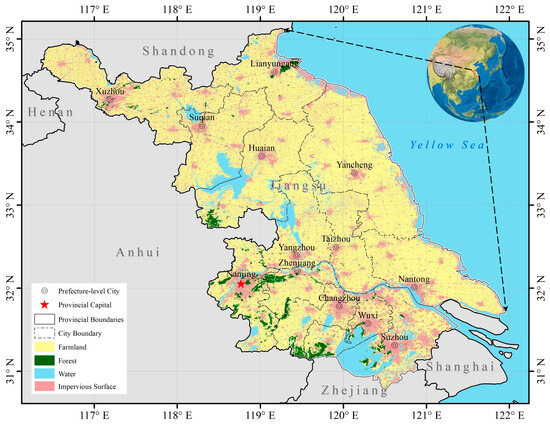

This study focuses on Jiangsu Province as the research area. Located between 30°45′ N and 35°20′ N latitude, and 116°18′ E and 121°57′ E longitude, Jiangsu lies at the intersection of the Yangtze River Economic Belt and the coastal development strategy, serving as a crucial grain-producing region in China (see Figure 1). The terrain is predominantly flat, spanning both northern and southern regions, and is conventionally divided into three major zones: Southern Jiangsu (including Nanjing, Suzhou, Zhenjiang, Wuxi, Changzhou), Central Jiangsu (including Yangzhou, Taizhou, Nantong), and Northern Jiangsu (including Xuzhou, Yancheng, Suqian, etc.). Southern Jiangsu, the most economically developed area in the province, sharply contrasts with Northern Jiangsu, which lags behind, resulting in significant disparities in development levels between the two extremes. Climatically, Jiangsu falls within the monsoon zone that transitions from subtropical to warm-temperate, characterized by distinct seasons, concurrent rainfall and heat, and concentrated precipitation during the summer months (June to August). The annual precipitation in the Jiangsu region ranges from 782 to 1150 mm. As a leading eastern economic province in China, Jiangsu has undergone significant farmland changes due to urbanization and industrialization, exhibiting regional disparities in farmland non-agriculturalization, specifically: “Southern Jiangsu > Central Jiangsu > Northern Jiangsu.” The highest degree of farmland non-agriculturalization is found in Southern Jiangsu, followed by Central Jiangsu, with Northern Jiangsu exhibiting relatively lower levels. This spatial differentiation provides a typical case for exploring regional patterns of farmland non-agriculturalization. The study encompasses all 13 prefecture-level cities in Jiangsu Province, with a focus on the differences in farmland non-agriculturalization across regions with varying economic development levels.

Figure 1.

Study area.

2.2. Data Sources

(1) China Land Cover Dataset, CLCD

The land use data utilized in this study is derived from the China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD) [31], which was released by Professor Huang Xin’s team at Wuhan University. This dataset has a spatial resolution of 30 m and encompasses a time span from 2000 to 2023. It is based on Landsat series images that have been integrated using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform. The dataset was generated by combining spatiotemporal features with a random forest classifier, achieving an overall classification accuracy of more than 80%. In ArcGIS 10.8, the raw data was reclassified into six categories: cultivated land, forest land, grassland, water bodies, impermeable surfaces (construction land), and bare land (unused land). These categories are employed to extract essential information, such as the area of cultivated land, the conversion area from cultivated land to other land types, and the non-agriculturalization rate for each period.

(2) Digital elevation model, DEM

The ground elevation data utilized in this study is derived from the Copernicus Digital Elevation Model (DEM), which boasts a spatial resolution of 30 m. This model was generated by the European Space Agency using TanDEM-X satellite radar data collected between 2011 and 2015, and subsequently sampled from WorldDEM products. The data is accessible via the Europe an Space Agency’s Copernicus Panda website (https://browser.dataspace.copernicus.eu/, accessed on 25 November 2025) or through the OpenTopography platform (https://portal.opentopography.org, accessed on 25 November 2025). This data facilitates the extraction of terrain indicators, such as altitude and slope, which are essential for conducting vertical location analysis of non-agricultural cultivation on cultivated land.

(3) Meteorological data

The temperature data utilized in this study is derived from a monthly average temperature dataset available on the platform (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/71ab4677-b66c-4fd1-a004-b2a541c4d5bf, accessed on 25 November 2025). This dataset features a spatial resolution of 1 km and spans the years from 1901 to 2023. The annual average temperature is computed by taking the average of the 12 monthly temperature values for each respective year, thereby facilitating a comprehensive analysis of meteorological factors.

(4) Precipitation data

The precipitation data utilized in this study is derived from the monthly precipitation dataset released by scholar Peng Shouzhang at the National Qinghai–Tibet Plateau Science Data Center (https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/zh-hans/data/faae7605-a0f2-4d18-b28f-5cee413766a2, accessed on 25 November 2025). This dataset features a 1 km resolution grid, which represents the total monthly precipitation. The annual precipitation data is calculated by aggregating the monthly precipitation over a 12-month period, providing insights into the potential impact of meteorological factors on the non-agricultural use of cultivated land.

(5) Socio-economic statistical data

The social statistical data is derived from the statistical yearbooks of Jiangsu Province and the 13 prefecture-level cities under its jurisdiction, with supplementary information obtained from local economic bulletins. This data encompasses: (1) land use-related metrics, including cultivated land area, non-agricultural area, and the non-agricultural rate; (2) social and economic indicators such as GDP, the proportion of agricultural output value, permanent population, per capita income, and grain production. This data is utilized to support the analysis of regional disparities and to explore the driving mechanisms behind the non-agricultural cultivation of arable land. In instances of missing data, adjacent year data has been employed as a substitute.

3. Methods

3.1. Non-Agriculturalization Rate of Cultivated Land Calculation

The non-agriculturalization rate of cultivated land serves as a metric to characterize the extent of non-agriculturalization within the study area. This rate is calculated as the ratio of the total area of cultivated land that has been converted to other land types over a specific period to the total initial area of cultivated land at the beginning of that period. In this study, a conversion of cultivated land to other types, such as forest land, grassland, water bodies, impervious surfaces (construction land), or bare land, is classified as non-agricultural conversion. The formula for calculating the non-agricultural conversion rate of cultivated land is expressed as follows:

where represents the non-agricultural land conversion rate during the t period (%); denotes the total area of cultivated land converted to other types by the end of the t period (i.e., the non-agricultural land area during this period, in km2); and indicates the total area of cultivated land at the beginning of the period (in km2).

3.2. Geographical Location Difference Statistics

Geographical differences significantly impact the spatial distribution of non-agricultural land. To elucidate the spatial differentiation patterns of non-agriculturalization, this study constructs analytical indicators based on two spatial dimensions: vertical and horizontal. The vertical dimension encompasses two terrain factors—altitude and slope—while the horizontal dimension focuses on two locational variables: distance to construction land and distance to rivers. Considering the physical and geographical characteristics of Jiangsu Province, these indicators are further categorized into 15 gradient levels. Utilizing techniques such as spatial overlay and buffer zone simulation, this research systematically explores the varying intensities of different locational factors on the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land. The classification details for each indicator are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification criteria for terrain gradient levels.

3.3. Spatial Correlation Analysis

Spatial autocorrelation refers to the correlation characteristics of geographical phenomena or variables in spatial distribution, reflecting their aggregation trends or spatial heterogeneity [32]. This study analyzes the spatial agglomeration characteristics of cultivated land non-agriculturalization using Moran’s I. This index serves as the primary measure for assessing spatial autocorrelation in spatial statistics and encompasses two levels: Global Moran’s I and Local Moran’s I. The calculation formula for the global Moran index is as follows:

where I represents the global Moran index; and denote the cultivated land non-agriculturalization rates of research units i and j, respectively; is the average non-agriculturalization rate across all research units; is the sample variance; and is the spatial weight matrix. The value of I ranges from [−1, 1]: a positive value (approaching 1) indicates a positive spatial correlation (clustered distribution) in the non-agricultural land conversion rate; a negative value (approaching −1) signifies a negative spatial correlation (discrete distribution); and a value close to 0 reflects a random distribution.

The global Moran index primarily describes the spatial correlation characteristics of the entire study area and is suitable for analyzing autocorrelation patterns at a global scale. However, it poses challenges in visually presenting the spatial correlation differences in local areas. Consequently, this study further employs the local Moran index to conduct a detailed analysis of the spatial correlation characteristics of each research unit. The calculation formula is as follows:

Among them, is the local Moran index; is the spatial weight value; n is the total number of research units; is the non-agriculturalization rate of cultivated land in a single research unit; is the average non-agriculturalization rate of all research units.

The significance of spatial autocorrelation is tested by the standardized statistic Z(I), and the calculation formula is:

Among them: E(I) is the expected value of I; V(I) is the variance of I. At the 0.01 significance level, if ≥ 2.58, the spatial autocorrelation is considered significant.

Based on the results of the local Moran index and significance tests, the spatial distribution of the cultivated land non-agriculturalization rate can be categorized into five correlation patterns: (1) “high–high” agglomeration areas, where high-value units are surrounded by other high-value units; (2) “high–low” contrast areas, where high-value units are adjacent to low-value units; (3) “low–high” transition areas, where low-value units are surrounded by high-value units; (4) “low–low” agglomeration areas, characterized by low-value units clustering together; and (5) “not significant” districts, where no significant correlation is observed.

3.4. Driving Factors Exploration

Geodetector is a spatial statistical method employed to analyze the relationship between the spatial differentiation characteristics of geographical phenomena and potential driving factors. Its core module, the factor detector, identifies whether the independent variable serves as a driving factor for the dependent variable and, to a certain extent, elucidates the formation mechanism of the spatial pattern of the dependent variable [33].

Consequently, this study utilizes factor detectors to examine the driving factors behind cultivated land non-agriculturalization, expressed as:

Here, represents the explanatory power value of the driving factor on cultivated land non-agriculturalization, with a value range of [0, 1]. A larger value indicates a stronger capacity of the factor to explain the spatial differentiation of cultivated land non-agriculturalization. In this equation, h denotes the number of partitions or classifications; and represent the total number of units in the study area and the number of units in sub-region , respectively; and and are the variances of the dependent variables in the entire region and sub-region , respectively. The index system of influencing factors on cultivated land non-agriculturalization is presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The index system of influencing factors on cultivated land non-agriculturalization.

This study introduces the Optimal Parameter Geodetector (OPGD) model, which optimizes the selection of data discretization methods and the number of classifications, thereby reducing subjective bias. Following the optimal discretization of the data, the driving factors behind the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province were analyzed using factor detectors. This analysis was conducted with assistance from the GeoDetector package in R (https://cran.r-project.org/, accessed on 25 November 2025). Furthermore, this study employs a method that integrates the Geodetector model with the XGBoost-SHAP interpretable machine learning model to quantify the impacts of natural, socioeconomic, and agricultural factors on the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land. The Geodetector identifies dominant driving factors by calculating factor explanatory power (Q-value), while the XGBoost-SHAP model provides further insights into the marginal effects and interaction mechanisms of each factor. The selection of indicators comprehensively considers natural background conditions, the intensity of human activities, and characteristics of agricultural production, encompassing multidimensional factors such as terrain, climate, water resources, economic development, population agglomeration, urban radiation, and agricultural structure.

4. Results Analysis

4.1. Spatial and Temporal Pattern of Agricultural Land Use in Jiangsu Province

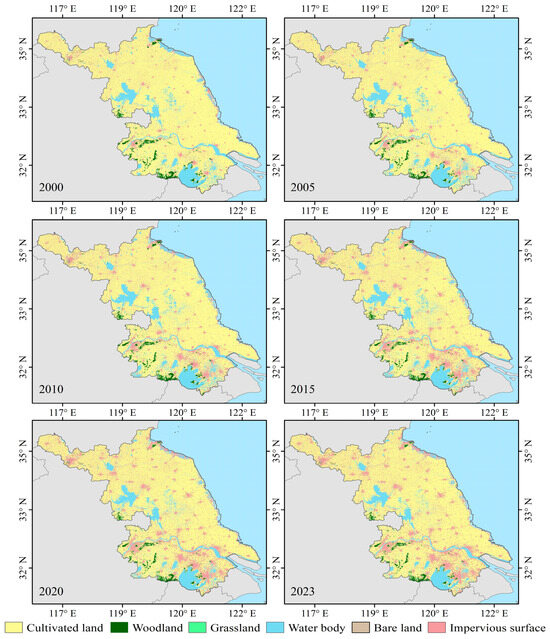

As shown in Figure 2, from the perspective of time evolution, land use in Jiangsu Province exhibits distinct dynamic transformation characteristics from 2000 to 2023. The area of cultivated land has consistently decreased, particularly in urban areas and along major transportation routes, with the conversion of cultivated land to other land uses intensifying over time. Conversely, the area of impervious surfaces has shown a significant expansion trend; it was sparsely distributed in 2000 and 2010, but has rapidly spread in southern Jiangsu (including regions around Taihu Lake and cities such as Suzhou, Wuxi, and Nanjing along the Yangtze River) since then. This expansion has continued unabated from 2020 to 2023, reflecting the increasing encroachment of urban development on cropland.

Figure 2.

Spatial distribution of land use in Jiangsu Province in six periods from 2000 to 2023.

From a spatial pattern perspective, woodlands and grasslands are primarily concentrated in regions with favorable ecological backgrounds or relatively complex terrains, such as the southwestern and northern parts of Jiangsu Province. Their spatial distribution remains generally stable, with only minor local adjustments. Water bodies, encompassing natural waters such as Taihu Lake, Hongze Lake, and the Yangtze River, maintain a consistent spatial pattern; however, land use transformations around these water areas, particularly the conversion of cultivated land to construction land, are notably pronounced. Overall, the predominant feature of land use change in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023 is the ongoing transformation of cultivated land into construction land, with this change being most concentrated and significant in the densely populated urban areas of southern Jiangsu. The spatial patterns of land use types such as woodlands, grasslands, and water bodies remain relatively stable.

From 2000 to 2023, the land use structure of Jiangsu Province has exhibited significant dynamic changes. The primary aspect is the fluctuation of cultivated land and impervious surfaces. Additionally, woodland, grassland, water bodies, and other land types have also experienced varying degrees of adjustment (see Table 3). As the predominant land use type, the area of cultivated land reached 77,738 km2 in 2000, accounting for 76.42% of the total area. However, it experienced a continuous decline from 2000 to 2015, decreasing to 70,597 km2 (69.40%) by 2015, marking a significant reduction. Following a slight decrease from 2015 to 2020, the area of cultivated land slightly rebounded to 70,662 km2 (69.47%) in 2023, indicating an overall trend of “initial continuous reduction followed by a slight recovery in the later period.” The impervious surface has undergone the most substantial changes among land types. The year-on-year expansion from 10,273 km2 to 19,322 km2 intuitively highlights the ongoing increase in land occupation due to human activities, particularly urban construction. Overall, the fundamental logic behind land use changes in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023 is the rapid expansion of impervious surfaces driven by urbanization, coupled with corresponding adjustments in land types such as cultivated land and water bodies. Ecological lands, including forestland and grassland, have also been somewhat marginalized, while the slight recovery of cultivated land in the later period reflects the dynamic allocation of land resources among production, living, and ecological functions.

Table 3.

Area and proportion of various categories in Jiangsu Province in six periods from 2000 to 2023.

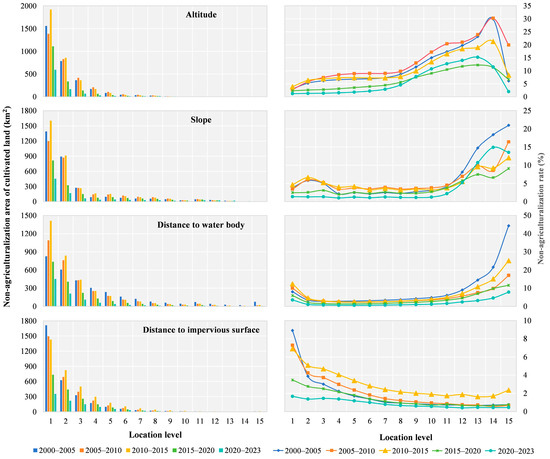

4.2. Distribution Characteristics of Spatial Location of Non-Agricultural Cultivated Land

From Figure 3, we can observe that the distribution of non-agricultural land within cultivated areas is influenced by factors such as altitude, slope, proximity to impervious surfaces, and distance from water bodies. This distribution exhibits a spatial pattern characterized by a concentration in low-lying areas, a gradual expansion into mid-to-high elevation zones, and marginal penetration into high-altitude locations. Additionally, a temporal pattern is evident, indicating a gradual progression from lower to mid-to-high levels over time. Notably, the low-lying areas (Levels 1–3), with altitudes ranging from 0 to 15 m, slopes between 0 and 6°, and proximity to impermeable surfaces and water bodies, have consistently served as core concentration zones for non-agricultural development due to their relatively low development and construction costs. The non-agricultural area was largest during each time period, particularly concentrated in the early stages. The mid-level areas (Levels 4–10), situated at altitudes of 15 to 50 m and slopes ranging from 6 to 30°, function as transition zones for expansion. Although the non-agricultural area decreases as elevation increases, the rate of non-agriculturalization shows an upward trend, significantly increasing in later stages (2015–2023) compared to earlier periods, thus becoming the primary region for urban spatial expansion. In contrast, high-altitude areas (Levels 11–15), with altitudes exceeding 50 m and slopes greater than 30°, face constraints due to terrain and locational factors, resulting in a consistently small area designated for non-agricultural use, thereby categorizing them as restricted zones.

Figure 3.

Analysis chart of non-agricultural land location factors.

The non-agriculturalization rate increased significantly in the later stages, particularly from 2020 to 2023, indicating a marginal expansion into high-constraint locations. Only extremely high-constraint areas—such as those at level 15, with altitudes exceeding 200 m and slopes greater than 60°—remain limited in scale due to significant constraints. From a temporal perspective, the non-agriculturalization process initially concentrated on low location levels and has progressively advanced to medium and high location levels. This trend reflects the phased evolution of urban spatial expansion, transitioning from core lowlands to peripheral suboptimal or constrained locations.

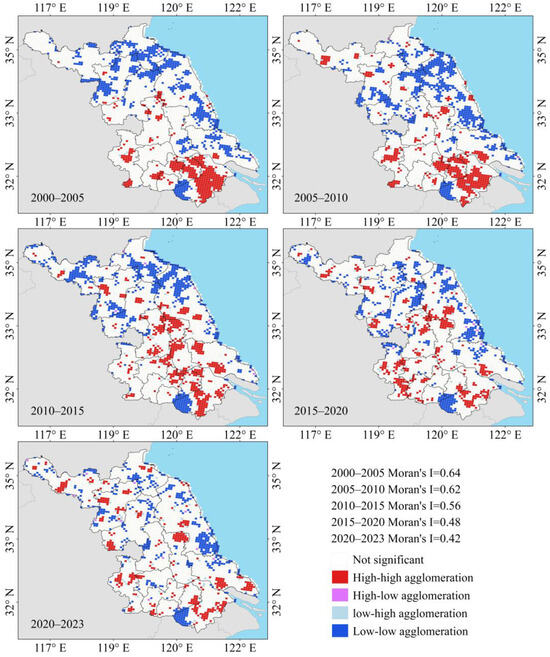

As shown in Figure 4, the spatial aggregation of the non-agriculturalization rate of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province exhibits a spatiotemporal evolution pattern characterized by a weakening of global aggregation, an expansion of local hotspots along the river, and a stabilization of cold spots in northern Jiangsu. Moran’s I value declined from 0.64 between 2000 and 2005 to 0.42 from 2020 to 2023, indicating a continuous weakening of the global spatial aggregation of cultivated land non-agriculturalization rates. Furthermore, the inter-regional spatial correlation of non-agriculturalization has evolved from a state of ‘strong aggregation’ to one of ‘relative dispersion’.

Figure 4.

Spatial aggregation characteristics of cultivated land non-agriculturalization rate in Jiangsu Province.

(1) High–high agglomeration areas (where both the areas themselves and their surrounding non-agriculturalization rates are high): During the initial period from 2000 to 2010, these areas were predominantly located in the core region of southern Jiangsu, specifically in cities such as Suzhou, Wuxi, Changzhou, and parts of Nanjing, with a relatively concentrated distribution. However, after 2010, the number of high–high agglomeration areas experienced a brief decline from 2010 to 2020. Subsequently, from 2020 to 2023, there has been a resurgence, particularly notable in 2016, with the agglomeration extending to regions adjacent to the Yangtze River in central Jiangsu, including Nantong and Yangzhou. This trend reflects the gradual expansion of ‘hot spots’ for non-agricultural land conversion from traditional southern Jiangsu to the riverside areas.

(2) Low–low agglomeration areas (where both the non-agriculturalization rates of the areas themselves and their surrounding areas are low): These areas have exhibited a long-term and stable distribution across most regions of northern Jiangsu, including Xuzhou, Huai’an, and northern Yancheng. Although the number of such areas may fluctuate, they demonstrate strong spatial continuity. This stability indicates that northern Jiangsu is constrained by factors such as terrain and location, resulting in consistently low levels of non-agriculturalization of cultivated land and stable aggregation characteristics.

(3) High–low and low–high agglomeration areas (where the levels of non-agriculturalization rates are opposite to those of the surrounding areas): The number of patches in these areas is limited and dispersed, with no centralized distribution observed during any period. This indicates that the local heterogeneous phenomenon characterized by ‘large contrasts in non-agriculturalization levels’ between regions remains relatively scattered and has not evolved into a dominant spatial distribution type.

4.3. Temporal and Spatial Evolution Characteristics of Non-Agricultural Land Use

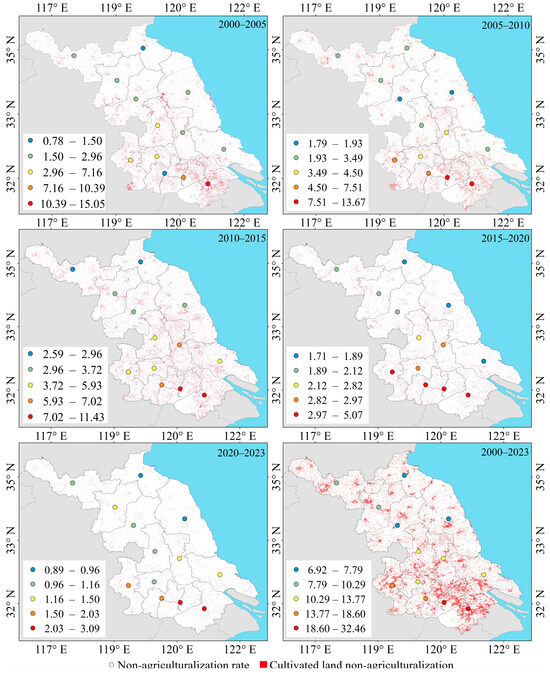

The spatio-temporal distribution map in Figure 5, along with the non-agriculturalization rate table of Jiangsu Province presented in Table 4, facilitates a detailed analysis of the spatial pattern of non-agriculturalization within the province.

Figure 5.

Spatial and temporal distribution of non-agriculturalization in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023.

Table 4.

Changes in cultivated land area and non-agricultural land conversion rate in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023.

From 2000 to 2023, the spatial distribution of cultivated land non-agriculturalization in Jiangsu Province exhibits a strong correlation with the urbanization process. This pattern is characterized by core agglomeration in southern Jiangsu, regional gradient diffusion, and a gradual convergence in the later period. High non-agriculturalization rates have consistently been concentrated in the urban dense belts of southern Jiangsu. Specifically, a continuous high-intensity deagriculturalization zone extends from Nanjing eastward along the Yangtze River to Suzhou and Wuxi, where the non-agriculturalization rate predominantly ranges from 13.77% to 32.46%. This region represents the most significant area for the conversion of cultivated land to non-agricultural land within the province. In contrast, non-agriculturalization in central and northern Jiangsu is primarily localized around the urban areas of prefecture-level cities, exhibiting a scattered, point-like distribution. The cumulative non-agriculturalization rates in these areas are generally between 6.92% and 10.29%, indicating an overall intensity that is considerably lower than that observed in southern Jiangsu.

Table 5 illustrates that the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023 exhibits a temporal evolution characterized by an initial phase of rapid expansion followed by a gradual deceleration. The predominant transition type is ‘impervious surface (construction land),’ which is spatially concentrated in densely populated urban areas.

Table 5.

Non-agriculturalization rate of prefecture-level cities in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023.

The spatial and temporal evolution of cultivated land non-agriculturalization can be categorized into two primary stages: a rapid expansion stage (2000–2015) and a gradual slowdown stage (2015–2023). During the rapid expansion stage, the swift advancement of urbanization significantly accelerated the conversion of cultivated land to non-agricultural land. Conversely, in the gradual slowdown stage, the enforcement of cultivated land protection policies and the transformation of urbanization development models have effectively curtailed the rate of non-agricultural land conversion. These two stages align with the anticipated outcomes of the implementation of Jiangsu Province’s cultivated land protection policy.

The spatiotemporal distribution map presented in Figure 5, along with the non-agriculturalization rate table of prefecture-level cities in Jiangsu Province (Table 5), facilitates an analysis of the spatial pattern of non-agriculturalization in the region. From 2000 to 2023, the spatial distribution of cultivated land non-agriculturalization in Jiangsu Province exhibits a strong correlation with the urbanization process, characterized by a pattern of “core agglomeration in southern Jiangsu, regional gradient diffusion, and gradual convergence in the later stages.” High non-agriculturalization rates have consistently been concentrated in the urban dense belts of southern Jiangsu. This region features a continuous high-intensity deagriculturalization zone extending from Nanjing eastward along the Yangtze River to Suzhou and Wuxi, where non-agriculturalization rates predominantly range between 13.77% and 32.46%. This area represents the most significant concentration of cultivated land conversion to non-agricultural land within the province. In contrast, non-agriculturalization in central and northern Jiangsu is primarily localized around urban areas of prefecture-level cities, appearing in a scattered, point-like distribution. The cumulative non-agriculturalization rates in these areas generally fall between 6.92% and 10.29%, indicating an overall intensity significantly lower than that of southern Jiangsu.

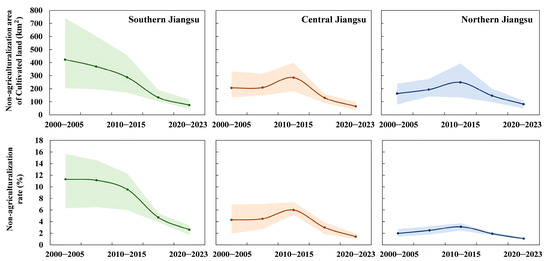

Figure 6 illustrates the changes in the non-agricultural area and the rate of cultivated land across the southern, central, and northern regions of Jiangsu. A significant gradient difference is observed in the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land in Jiangsu. Specifically, the non-agricultural area and rate of cultivated land in southern Jiangsu are markedly higher than those in central and northern Jiangsu, with the non-agriculturalization rate of cultivated land in northern Jiangsu being the lowest in the province. From 2000 to 2005, the non-agricultural area and rate of cultivated land in southern Jiangsu remained elevated, followed by a rapid decline. Between 2020 and 2023, this rate decreased further, indicating a clear overall downward trend. In contrast, the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land in central and northern Jiangsu exhibited a fluctuating upward trend from 2000 to 2015. After peaking between 2010 and 2015, it experienced a sharp decline from 2020 to 2023, entering a contraction phase.

Figure 6.

Changes in cultivated land area and non-agricultural land conversion rate in different regions of Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023.

4.4. Driving Factors Analysis for Non-Agriculturalization of Cultivated Land

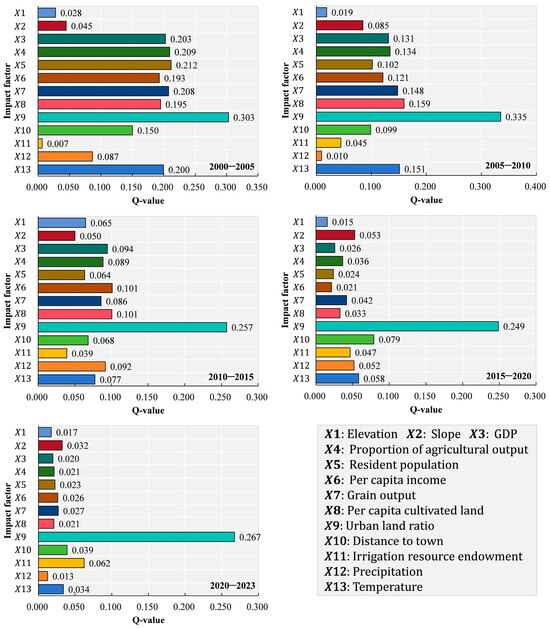

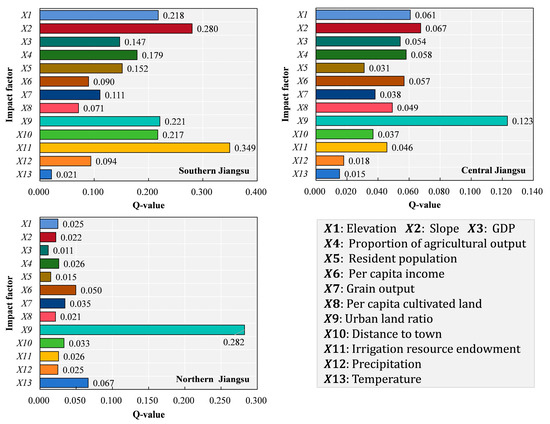

The results of the factor detector are illustrated in Figure 7. With the exception of the permanent population from 2000 to 2010 (X5) and the temperature from 2015 to 2023 (X13), as well as irrigation resource endowment (X11) and permanent population (X5), all other factors passed the significance test at p < 0.05. The average explanatory power of each factor regarding the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land across the three periods—2000–2010, 2010–2015, and 2015–2023—was 0.132, 0.195, and 0.115, respectively. These findings indicate significant differences in the intensity of the driving factors at various stages.

Figure 7.

Non-agricultural factor detector results for cultivated land.

Throughout the study period from 2000 to 2023, the proportion of urban land (X9) has consistently been the primary factor influencing non-agricultural land conversion. The proportion of urban land serves as a direct indicator of urban expansion intensity. Specifically, during this period, the proportion of urban land in southern Jiangsu increased from 10.10% to 19.00%, with a corresponding non-agriculturalization rate, such as that observed in Suzhou at 32.46%, significantly exceeding that of northern Jiangsu. This trend confirms that the occupation of construction land is a direct cause of non-agricultural land conversion. Additionally, per capita cultivated land reflects the fundamental conditions for agricultural production. Northern Jiangsu benefits from sufficient per capita cultivated land, a strong willingness among farmers to engage in farming, and a low abandonment rate. The non-agriculturalization rate in this region, exemplified by only 6.92% in Yancheng, is markedly lower than that in southern Jiangsu. Conversely, areas with limited per capita cultivated land are more susceptible to farming abandonment due to insufficient agricultural income, thereby facilitating de-agriculturalization.

From the perspective of driving factors in different periods, 2000–2005 and 2005–2010 were the early stages of rapid non-agricultural land expansion, where the primary factor influencing cultivated land non-agriculturalization was the urban land ratio (X9), coupled with the combined effects of multiple factors including GDP (X3), proportion of agricultural output value (X4), permanent population (X5), per capita income (X6), grain production (X7), per capita cultivated land (X8), distance to urban areas (X10), and temperature (X13); 2010–2015 marked the peak period of the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land, during which the impacts of all factors except the urban land ratio (X9) on the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land diminished, and the speed of urban expansion accelerated significantly in this stage—the urban land ratio directly affected the scale of cultivated land occupation, with stronger urban radiation effects leading to a higher likelihood of non-agricultural conversion; 2015–2023 was a period of slowing the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land, where the urban land ratio (X9) occupied an absolutely dominant position in the process of the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land, and the influences of other factors except the urban land ratio (X9) on the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land further declined. Overall, in the early stage of rapid non-agricultural land expansion (2000–2010), the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province was jointly driven by multiple factors such as socio-economic conditions and natural environments, while in the middle (2010–2015) and late (2015–2023) stages, the explanatory power of socio-economic factors weakened, and the urban land ratio (X9) became the absolutely dominant factor in the process of non-agriculturalization.

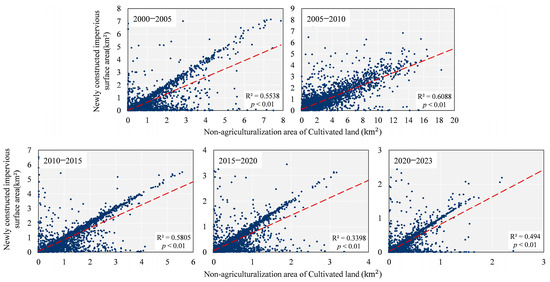

To further verify the impact of the urban land ratio (X9) on the non-agriculturalization process, we conducted a correlation analysis between the impervious surface expansion area and non-agricultural land expansion in different periods. As shown in Figure 8, during various periods from 2000 to 2023, there was a significant correlation between the impervious surface expansion area and the non-agriculturalization of cultivated land (p < 0.01); from 2000 to 2015, the correlation coefficient R2 was greater than 0.55 in all sub-periods, and reached 0.6088 during 2005–2010. This further confirms the decisive role of the urban land ratio (X9) in cropland non-agriculturalization.

Figure 8.

Correlation Analysis between Impervious Surface Expansion and Cropland Non-Agriculturalization Process.

The detection results of driving factors for non-agricultural land use in different regions of Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023 are illustrated in Figure 9. The driving factors for the non-agricultural use of farmland in southern, central, and northern Jiangsu exhibit significant regional differentiation. In southern Jiangsu, the availability of irrigation resources stands out as the most critical driving factor. Conversely, in central Jiangsu, the proportion of urban land use has emerged as the primary driving factor, indicating that urbanization serves as the key impetus for the non-agricultural use of arable land in this region. The influence of other factors diminishes in a descending order, reflecting a comprehensive driving force that includes urbanization, terrain, agricultural economy, and population dynamics, with each factor’s impact being relatively more balanced compared to southern Jiangsu. In northern Jiangsu, the predominance of urban land use again emerges as the main driving factor, underscoring the significant role of urbanization in the non-agricultural utilization of arable land.

Figure 9.

Non-agricultural factor detector results for cultivated land in different regions of Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023.

5. Discussion

5.1. Dynamic Spatiotemporal Pattern of Non-Agriculturalization of Cultivated Land

With the rapid advancement of industrialization and urbanization, the imbalance between land resource supply and demand has become increasingly pronounced, rendering cultivated land protection a critical issue for sustainable development in Jiangsu Province. This study quantifies the scale and temporal variations in cultivated land non-agriculturalization through a land use transition matrix. By integrating spatial autocorrelation analysis (Moran’s Index) and location gradient analysis, it investigates the spatial differentiation and clustering patterns of non-agriculturalization. Utilizing the geographical detector model, the study explores the driving mechanisms of cultivated land non-agriculturalization from three dimensions: natural, socio-economic, and agricultural factors. Through a systematic analysis of the characteristics and driving mechanisms of cultivated land non-agriculturalization in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023, this research reveals the spatiotemporal evolution patterns and formation mechanisms of cultivated land non-agriculturalization in the region.

In terms of spatial distribution and evolutionary patterns, cultivated land in Jiangsu Province is influenced by both terrain and urbanization. Cultivated land is primarily concentrated in the northern Jiangsu Plain and the central Jiangsu Yangtze River region, maintaining a long-term proportion of 69% to 76%. However, due to the presence of dense urban areas, the proportion of arable land in the southern Jiangsu region is only 60% to 70% of that in northern Jiangsu. The evolutionary process reveals a distribution characteristic of ‘continuous reduction in the surrounding areas of towns along southern Jiangsu and relative stability in the core area of northern Jiangsu. This pattern is consistent with the “peri-urban concentration” of cropland loss observed by other scholars in the Yangtze River Delta. Specifically, in rapidly urbanizing regions, over 70% of non-agricultural conversion occurs within 30 km of urban centers [34]. However, unlike the Pearl River Delta, where urban expansion drives cropland loss in large contiguous patches, southern Jiangsu shows more fragmented conversion due to stricter land use planning constraints [35]. This north–south gradient is consistent with national-scale findings that economic development is the primary driver of cropland conversion, with eastern coastal provinces showing higher rates than inland regions [36]. The southern Jiangsu’s higher non-agriculturalization rate (exceeding 30% in Suzhou) aligns with the correlation between GDP growth and cropland loss identified in Jiangsu-specific studies [37], while northern Jiangsu’s stability reflects its role as a major grain-producing area.

The formation of this gradient difference feature is primarily attributed to the spatial differentiation in economic development levels and industrial structures. As the core economic area of the eastern region, the proportion of urban land in southern Jiangsu has surpassed 25% by 2023, with the highest per capita GDP and income in the province. The demand for construction land, driven by economic development, is substantial, while the proportion of agricultural output value generally remains below 10%. This diminished role of agriculture within the economic structure has lessened the ‘economic constraint’ on cultivated land protection, resulting in a persistently high rate of non-agricultural conversion. In central Jiangsu (including Nantong and Yangzhou), urbanization has accelerated since 2010, influenced by the development in southern Jiangsu. The non-agricultural conversion rate (11.60–18.60%) lies between those of southern and northern Jiangsu, revealing a local disparity characterized by ‘higher rates in riverside areas and lower rates in inland regions.’ Conversely, northern Jiangsu (such as Yancheng and Huai’an), recognized as the main grain-producing areas of the province, has consistently maintained an agricultural output value ratio exceeding 15%. Additionally, the per capita arable land area in this region is 2–3 times greater than that of southern Jiangsu. Agricultural production continues to be a cornerstone of the regional economy, and the limitations imposed by terrain conditions (with certain areas featuring high elevations and steep slopes) contribute to a consistently low non-agricultural conversion rate (6.92–10.29%), thus serving as a ‘stabilizer’ for arable land protection in the province.

Jiangsu Province exhibited an overall trend of continuous reduction followed by a slight recovery after 2015. The area decreased from 77,738 km2 to 70,662 km2, with cumulative non-agricultural conversion reaching 9739 km2. The temporal pattern of non-agricultural conversion revealed a rapid expansion phase from 2000 to 2015, during which the peak non-agricultural conversion rate of cultivated land reached 4.83%. This was followed by a gradual slowdown phase from 2015 to 2023, where the peak rate decreased to 1.36%. This post-2015 slowdown coincides with the nationwide implementation of strict cropland protection policies, which attributed the deceleration to enhanced land use regulation and ecological redline policies [38]. Similar trends were reported in other eastern provinces, where policy enforcement reduced cropland conversion rates [39]. Spatially, the evolution pattern displayed a significant gradient difference, with Southern Jiangsu exhibiting the highest rates, followed by Central Jiangsu and Northern Jiangsu. Specifically, in Suzhou and Wuxi of Southern Jiangsu, the non-agricultural conversion rates from 2000 to 2023 reached 32.46% and 27.41%, respectively. In contrast, Yancheng and Huai’an of Northern Jiangsu recorded rates of only 6.92% and 7.79%. Concurrently, the non-agricultural conversion of cultivated land was highly correlated with locational factors, with over 80% of converted land concentrated in areas with elevations of 0–15 m, slopes of 0–6°, and distances to towns less than 30 pixels. This confirms that low terrain constraints and strong urban radiation are the core spatial conditions driving non-agricultural conversion.

5.2. Spatial Heterogeneity of Driving Factors of Non-Agriculturalization

The non-agriculturalization of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province results from the combined effects of natural background constraints, socio-economic drivers, and agricultural regulations. Natural factors, such as elevation and slope, act as spatial filters by limiting development costs; for instance, the non-agriculturalization rate is less than 1% in high-altitude areas (above 200 m) and steep slope regions (greater than 60°). Among socio-economic factors, urban expansion serves as the most direct driving force. From 2000 to 2023, the impermeable surface area in the province increased from 10,273 km2 to 19,322 km2, with the explanatory power of the urban land use ratio and distance to urban areas for non-agricultural use exceeding 0.35. Agricultural factors, including per capita arable land and the proportion of agricultural output value, influence non-agriculturalization by adjusting the willingness to cultivate. Notably, the non-agriculturalization rate in areas with sufficient per capita arable land in northern Jiangsu is significantly lower.

From the perspective of core driving factors, urban expansion serves as the most direct incentive for the non-agricultural use of arable land in Jiangsu Province. Between 2000 and 2023, the area of impermeable surfaces—indicative of urban construction land—increased from 10,273 km2 to 19,322 km2, with the proportion rising from 10.10% to 19.00%. This expansion contrasts sharply with the trend of arable land area, which has experienced a “continuous reduction followed by a slight recovery”; specifically, arable land decreased from 77,738 km2 to 70,662 km2, resulting in a cumulative non-agricultural area of 9739 km2, of which nearly 88% (8549 km2) has been converted to impermeable surfaces. The balance between arable land and construction land is particularly pronounced in the southern region of Jiangsu. Due to high-intensity urban expansion, cities such as Suzhou and Wuxi have recorded non-agricultural conversion rates of 32.46% and 27.41%, respectively, from 2000 to 2023, thereby forming a continuous non-agricultural belt along the Yangtze River. This evidence confirms that the direct occupation of high-quality arable land by urban expansion constitutes the core driving force behind non-agricultural conversion.

The impact of economic development on the non-agricultural use of arable land operates as both a driving and constraining force, resulting in a dual restriction mechanism. On one hand, economic development—illustrated by GDP growth and increases in per capita income—stimulates non-agriculturalization by elevating the demand for construction land. For instance, in the southern Jiangsu region, every increase of 10,000 yuan in per capita income correlates with an average rise of 2.1 percentage points in the non-agriculturalization rate, which aligns with the Environmental Kuznets Curve pattern identified by Zhang & Cui (2015) for eastern China, where economic growth drives cropland conversion before reaching a turning point [40]. Conversely, economic development also imposes constraints on non-agricultural activities through the optimization of industrial structure and the modernization of agriculture. In recent years, the northern Jiangsu region has sustained an agricultural output growth rate exceeding 5% by enhancing agricultural subsidies and promoting large-scale cultivation, which has augmented the economic value of arable land and effectively mitigated the risks associated with non-agricultural activities stemming from abandoned cultivation. Simultaneously, during the province’s economic transformation, certain cities in southern Jiangsu have curtailed the appropriation of newly added arable land by implementing strategies such as ‘retreating two to three’ and revitalizing existing construction land. From 2020 to 2023, the non-agricultural conversion rate in southern Jiangsu decreased by 3.47 percentage points compared to the period from 2010 to 2015, reflecting the constraints imposed by upgrading the economic development model on non-agricultural conversion.

The red line policy for arable land serves as a crucial regulatory measure aimed at constraining the non-agricultural expansion of arable land, with its effects gradually becoming apparent since 2015. In Jiangsu Province, the non-agricultural conversion rate peaked at 4.83% from 2010 to 2015, a period characterized by insufficient control over urban expansion, leading to significant occupation of cultivated land. Following 2015, the implementation of policies such as the red line system for arable land and the delineation of permanent basic cultivated land contributed to a gradual decrease in the non-agricultural conversion rate, which fell to 1.36% between 2020 and 2023. This policy-driven slowdown is consistent with Li et al. (2025)’s evaluation of China’s cropland balance policy, which found that strict enforcement reduced conversion rates by 15–25% in eastern coastal provinces [41]. However, the “gradient transfer” of non-agricultural development from southern to central Jiangsu is a region-specific phenomenon. Jiangsu’s transfer shows clear administrative boundary effects due to its stronger north–south economic gradient. In response to the stringent limitations imposed by the red line policy, some non-agricultural development demands in southern Jiangsu have migrated to central Jiangsu. For instance, although the non-agricultural conversion rate in Nantong was lower than that in southern Jiangsu from 2015 to 2023, it nonetheless experienced an increase of 3.28 percentage points compared to the period from 2000 to 2010, indicating a spatial reconfiguration of non-agricultural development under the constraints of policy.

5.3. The Impact of Policy Factors

The area and rate of non-agricultural use of arable land exhibited an upward trend from 2000 to 2015, with a notable rate of 4.83% observed between 2010 and 2015. Despite the emphasis on arable land protection through various policies during this period, the conversion of arable land into construction land—characterized by impermeable surfaces, which accounted for over 80%—remained relatively active. This was largely driven by the development orientation of accelerated urbanization and high-speed economic growth. Following 2015, the enactment of documents such as the “National Land Planning Outline (2016–2030)” and the “Jiangsu Province Farmland Protection Responsibility Target Assessment Method” prompted the government to implement measures, including the delineation of permanent basic farmland and dynamic supervision of farmland occupation and compensation balance. These actions aimed to mitigate disorderly non-agriculturalization from the perspectives of spatial control and quantity balance. Consequently, both the area and rate of non-agriculturalization have significantly decreased, with the non-agriculturalization rate dropping to only 1.36% from 2020 to 2023.

The response regarding non-agricultural policies for cultivated land across southern, central, and northern Jiangsu reveals significant disparities, illustrating the policy logic of “regional differentiated regulation.” As the most economically dynamic region in Jiangsu, early policies that supported urbanization and industrialization in southern Jiangsu facilitated extensive non-agricultural utilization of arable land. For instance, Suzhou’s non-agricultural conversion rate reached 15.05% between 2000 and 2005, the highest in the province. The process of non-agricultural conversion of cultivated land in Suzhong exhibits a pattern characterized by “mid-term fluctuations and an upward trend, followed by a subsequent decline,” reflecting the tension between “development” and “protection” policies. Driven by the urbanization strategy within the “Rise of Central Soviet Union,” the rate of non-agricultural conversion has accelerated. However, the implementation of unified farmland protection policies across the province, combined with an emphasis on enhancing agricultural production functions in central Jiangsu, has led to a rapid contraction of non-agricultural conversion. As a key grain-producing area in Jiangsu, northern Jiangsu has consistently prioritized the protection of arable land in its policies, resulting in an overall conversion rate significantly lower than that of southern Jiangsu. Under the dual constraints of the national food security strategy and the policy of grain production functional zones in Jiangsu Province, the enforcement of farmland protection policies has been continuously strengthened, maintaining the non-agricultural area and rate at a relatively low level.

5.4. Future Strategies and Suggestions

In summary, the conversion of agricultural land to non-agricultural uses in Jiangsu Province results from a combination of urban expansion, regional economic differentiation, policy constraints, and agricultural support. Despite Jiangsu’s significant achievements in cultivated land protection and the coordinated development of industry and agriculture, maintaining the cultivated land redline continues to face numerous challenges [42]. The core contradiction in the conversion of agricultural land in Jiangsu is the encroachment of urban expansion on cultivated land against the backdrop of rapid urbanization. This phenomenon is closely correlated with the spatial-temporal differentiation of regional economic development gradients, constraints imposed by cultivated land protection policies, and the foundational aspects of agricultural production, creating a complex mechanism of drivers and constraints with notable differences in the dominant influencing factors across various regions.

In the future, aerospace information technology and the low-altitude economy will be leveraged to construct an integrated monitoring platform known as the “aero-space network.” This initiative will include the establishment of a “one land, one file” system for cultivated land and will adhere to a “three-in-one” approach that focuses on the protection of cultivated land quantity, quality, and ecology [43,44,45]. Furthermore, the respect for legal frameworks, adaptation to prevailing circumstances, and customization of measures to local conditions will enable the effective coordination of the relationships among cultivated land protection, food production, and integrated urban–rural development via differentiated cultivated land protection policies [43]. It is essential to develop region-specific strategies that fully engage various stakeholders in the protection of arable land, enhance arable land productivity, and steadily expand agricultural production capacity.

The specific recommendations are as follows:

(1) In southern Jiangsu, with high-incidence areas of non-agricultural conversion of cultivated land, it is imperative to strengthen the control of urban development boundaries to prevent unregulated expansion. This includes enhancing land use planning management, strictly regulating the occupation of cultivated land by non-agricultural construction, and ensuring that the cultivated land red line is not breached [46]. Additionally, revitalizing existing land resources, optimizing land use structures, and developing high-yield, stable-standard cultivated land are crucial for maintaining grain production capacity. Concurrently, the promotion of green agriculture is essential to reduce the use of fertilizers and pesticides, protect the ecological environment of cultivated land, and effectively balance urban development with cultivated land conservation [4].

(2) In the central region of Jiangsu, the expansion of industrial land use poses a significant threat to the cultivated land protection line. It is necessary to balance the demands of industrialization and agricultural development, avoiding a ‘passive acceptance’ of non-agricultural land use. On the one hand, measures such as land consolidation and soil improvement should be implemented to enhance cultivated land quality [47]. On the other hand, promoting green development along with advanced agricultural technologies and equipment is vital for improving agricultural productivity, reducing production costs, and strengthening agricultural competitiveness. This approach ultimately aims to achieve a harmonious integration of cultivated land protection and economic development.

(3) In the northern regions of Jiangsu, it is essential to consolidate the foundation of agricultural production and establish a robust defense line for food security. With rising agricultural production costs and fluctuations in grain prices, the motivation of some farmers to cultivate crops has diminished, leading to occasional instances of abandoned cultivated land. Enhancing total factor productivity in agriculture and revitalizing farmers’ enthusiasm for crop cultivation are critical to safeguarding the red line of arable land [48,49]. The ‘scissors gap’ is a significant contributor to issues concerning food security and cultivated land protection [50]. Therefore, it is imperative to increase financial support for agriculture and establish an agricultural insurance system to motivate farmers to grow crops and mitigate agricultural production risks. Additionally, promoting the rational flow of resources between urban and rural areas, increasing farmers’ incomes, and achieving common prosperity between urban and rural regions are essential steps in this process.

6. Conclusions

The protection of cultivated land is intrinsically linked to the dual strategy of national food security and ecological security. This study systematically analyzes the non-agricultural conversion rate and the spatiotemporal differentiation characteristics of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province from 2000 to 2023, utilizing dense time-series land use data and statistical data. Furthermore, this study comprehensively explores the driving mechanisms behind the non-agricultural conversion of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province, examining natural, economic, and agricultural policy dimensions. The main conclusions of this study are as follows:

(1) The total cultivated land area in Jiangsu Province exhibits a trend of “continuous decrease followed by a slight rebound after 2015,” decreasing from 77,738 square kilometers to 70,662 square kilometers, with a cumulative non-agricultural land area of 9739 square kilometers. Spatially, it displays a distribution pattern characterized by “continuous reduction in southern cities and relatively stable core areas in the north.”

(2) The process of spatiotemporal evolution, the non-agricultural use of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province has demonstrated a trajectory of “rapid expansion (peaking at 4.83% from 2000 to 2015)—gradually slowing down (decreasing to 1.36% from 2015 to 2023).” The differences in spatial pattern gradients are significant, with the order being “southern Jiangsu > central Jiangsu > northern Jiangsu.”

(3) The non-agriculturalization of cultivated land in Jiangsu Province results from the combined effects of natural limitations, socio-economic driving factors, and agricultural policies, and it is strongly correlated with locational factors. More than 80% of non-agricultural cultivated land is concentrated in areas with an altitude of 0–15 m, a slope of 0–6 degrees, and within 1 km of the city center. Terrain constraints and urban radiation have emerged as the primary spatial conditions for the non-agricultural transfer of cultivated land.

Furthermore, urban expansion has been identified as the primary driving factor behind the non-agricultural use of arable land in Jiangsu Province in recent years. In contrast, the influence of agricultural factors on non-agricultural activities remains relatively weak, primarily affecting farmers’ willingness to transfer land. Since 2015, the effectiveness of the red line policy for cultivated land protection has improved, contributing to a deceleration in the non-agriculturalization process. The research findings presented herein provide a significant scientific basis for formulating differentiated cultivated land protection policies across the province, thereby facilitating a balance between food security and coordinated urban–rural development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Z., S.Q., M.G., J.L. and C.Z.; methodology, Q.S. and H.Z.; validation, H.Z. and Q.S.; formal analysis, C.Z., H.Z. and Q.S.; investigation, Q.S. and C.Z.; data curation, C.Z., J.L. and H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Z., Q.S. and C.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.Z., J.L., C.Z., M.G. and Q.S.; visualization, H.Z. and S.Q.; supervision, C.Z. and S.Q.; project administration, C.Z.; funding acquisition, C.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 42571346, in part by the Jiangsu Qinglan Project and the Research and Practice Innovation Plan for Postgraduates of Jiangsu Normal University under Grant 2025XKT1060. (Corresponding author: Qian Shen).

Data Availability Statement

The public datasets used for training the models are provided in Section 2. The individuals appearing in the test images used in the experimental sections are all members of the research group and cannot be shared due to privacy concerns.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wang, S.; Xu, L.; Adhikari, K.; He, N. Soil carbon sequestration potential of cultivated lands and its controlling factors in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y. Reflections on China’s food security and land use policy under rapid urbanization. Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. Effects of urbanization on spatial-temporal changes of cultivated land in Bohai Rim region. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 8469–8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Wen, L.; Li, K.; Kong, X.; Zhang, X. Environmental risk and burden inequality intensified by changes in cultivated land patterns. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2026, 225, 108604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Miao, Y.; Xie, Z.; Jiang, X. Address the challenge of cultivated land abandonment by cultivated land adoption: An evolutionary game perspective. Land Use Policy 2025, 149, 107412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Xu, B.; Huan, Y.; Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Han, J.; Li, K. Food security and land use under sustainable development goals: Insights from food supply to demand side and limited arable land in China. Foods 2023, 12, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, X.; Yao, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. Mapping the annual dynamics of cultivated land in typical area of the Middle-lower Yangtze plain using long time-series of Landsat images based on Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2020, 41, 1625–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Hu, S.; Frazier, A.E.; Xie, W.; Zang, Y. Cultivated Ecosystem Services in the Yangtze River Economic Belt: Distinguishing Characteristics and Underlying Drivers Over the Past 20 Years. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025, 36, 3827–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Xia, H.; Yang, J.; Niu, W.; Wang, R.; Song, H.; Guo, Y.; Qin, Y. Mapping cropping intensity in Huaihe basin using phenology algorithm, all Sentinel-2 and Landsat images in Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 102, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, C.A.; Hansen, T.E.; Fox, A.A.; Hesje, P.J.; Nelson, H.E.; Lawseth, A.E.; English, A. Farmland conversion to non-agricultural uses in the US and Canada: Current impacts and concerns for the future. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2012, 10, 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Cultivated land protection and rational use in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 106, 105454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, N.T. Comparing the process of converting land use purposes between socio-economic regions in Vietnam from 2007 to 2020. Environ. Socio-Econ. Stud. 2024, 12, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firmansyah, M.F.; Pusparini, D.P.; Vivero, A.A.; Lababit, N.G. Impact of Agriculture Factor and Non-Agriculture Factor to Value of Food Production: Cast Study of Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia and Philippines Period 2010–2019. Int. J. Agric. Soc. Econ. Rural Dev. 2021, 1, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasu Tufa, D.; Lika Megento, T. Conversion of farmland to non-agricultural land uses in peri-urban areas of Addis Ababa Metropolitan city, Central Ethiopia. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 5101–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimanova, O.; Naumov, A.; Greenfieldt, Y.; Prado, R.B.; Tretyachenko, D. Regional trends of land use and land cover transformation in Brazil in 2001-2012. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2018, 10, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanes, A.L.; Whitworth-Hulse, J.I.; Marchesini, V.A.; Jobbágy, E.G. Land values and agricultural expansion into dry regions of Argentina. GeoJournal 2025, 90, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Tang, B.; He, F.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Cui, D. Extraction and Prediction of Spatiotemporal Pattern Characteristics of Farmland Non-Grain Conversion in Yunnan Province Based on Multi-Source Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Yuming, Z.; Jiemou, D.; Xiang, L.; Shidong, L.; Liping, X. Spatiotemporal differentiation of nonagricultural and nongrain farmland in China and its management strategies. Arid Zone Res. 2025, 42, 372–383. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Zhao, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y. Cropland non-agriculturalization caused by the expansion of built-up areas in China during 1990–2020. Land Use Policy 2024, 146, 107312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Jin, X.; Liang, X.; Liu, J.; Han, B.; Zhou, Y. Diversification of food production in rapidly urbanizing areas of China, evidence from southern Jiangsu. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 101, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Jin, X. Spatio-temporal characteristics and driving factors of cultivated land change in various agricultural regions of China: A detailed analysis based on county-level data. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, E.; Chen, J.; Tan, Q. Dynamics and driving mechanisms of cultivated land at county level in China. Acta Geogr. Sin 2023, 78, 2105–2127. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, J.; Li, F.; Zheng, S.; Deng, Y. Assessing the spatiotemporal characteristics and dynamic evolution of non-grain production on cultivated land in China. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2025, 23, 2561296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Wei, X. Dynamics and causes of cropland Non-Agriculturalization in typical regions of China: An explanation Based on interpretable Machine learning. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Lin, N.; Zhang, X.; Wang, C.; Yang, K.; Ding, K.; Wang, B. Monitoring and Historical Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Arable Land Non-Agriculturalization in Dachang County, Eastern China Based on Time-Series Remote Sensing Imagery. Earth 2025, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Zhu, S.; Xiao, Z.; Zhu, G.; Li, J.; Cui, J.; He, W.; Sun, J. Spatiotemporal Variability and Drivers of Cropland Non-Agricultural Conversion Across Mountainous County Types: Evidence from the Qian-Gui Karst Region, China. Agriculture 2025, 15, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Wu, D.; Lin, W.; Fan, S.; Su, K. Land-Use Transitions and Its Driving Mechanism Analysis in Putian City, China, during 2000–2020. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Li, J.; Zeng, K.; Wang, L. Dynamic Evolution and Driving Mechanisms of Cultivated Land Non-Agriculturalization in Sichuan Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Li, M.; Chen, Z.; Li, W. Changes in ecosystem services supply–demand and key drivers in Jiangsu Province, China, from 2000 to 2020. Land Degrad. Dev. 2024, 35, 4666–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Jin, X.; Sun, R.; Han, B.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. A typical phenomenon of cultivated land use in China’s economically developed areas: Anti-intensification in Jiangsu Province. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. 30 m annual land cover and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; DU, D. Application of the integration of spatial statistical analysis with GIS to the analysis of regional economy. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2002, 27, 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Han, Z.; Koko, A.F.; Zhang, S. Spatio-temporal analysis of the driving factors of urban land use expansion in China: A study of the Yangtze River Delta region. Open Geosci. 2024, 16, 20220609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Yang, F.; Chen, J.; Tu, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Dong, T.; Xu, G. Spatial patterns of urban expansion and cropland loss during 2017–2022 in Guangdong, China. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]