Abstract

Rapid urbanization poses a significant challenge to striking a balance between urban development and heritage conservation, particularly in historic urban environments. In this regard, UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach reconceptualizes heritage as a multifaceted system of interwoven cultural and natural values, advocating for integrated and participatory governance. Nonetheless, the implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye is constrained by factors such as institutional fragmentation, overlapping mandates, and inadequate coordination among key stakeholders. This article aims to develop a conceptual system dynamics (SD) framework, informed by existing scientific literature, to elucidate the relationships between stakeholder objectives and the interdependencies that complicate the HUL implementation process in Türkiye. This article compiles and organizes key stakeholders and their corresponding objectives, as delineated in the scientific literature. The proposed conceptual SD model elucidates plausible pathways through which stakeholder objectives may interact with the HUL implementation process. Furthermore, this article presents critical considerations for stakeholder engagement and outlines a conceptual framework designed to enhance it during the HUL implementation process. Ultimately, this article presents a replicable conceptual framework designed to promote adaptive, inclusive, and sustainable implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye by integrating systems thinking into heritage governance practices.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of global urbanization has reshaped demographic, spatial, and cultural patterns, presenting significant challenges to the protection of historic sites. Today, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities, and this figure is expected to reach nearly 70% by 2050 [1]. This shift creates challenges between urban expansion and heritage preservation, especially in historic cities where modernization can threaten cultural values and social bonds [2]. Urbanization is not just a demographic change but also a socio-economic and environmental process that affects land-use, infrastructure, governance, and heritage preservation systems [3].

Conservation theory and practice initially centered on historically significant buildings and artifacts [4,5]. After World War II, rural-to-urban migration and rapid population growth highlighted the importance of preserving historic urban values as cities expanded. This prompted the development of new international charters and guidelines in the 1960s and 1970s, such as the Venice Charter [6] and the European Charter for the Conservation of the Architectural Heritage [7], which broadened conservation efforts from individual monuments to the comprehensive protection of urban areas. Over time, the concept of heritage has expanded to encompass cultural landscapes and living heritage, positioning heritage as a vital resource for sustainable development, social cohesion, and resilience [8,9].

UNESCO’s Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach [10] refines these changes, redefining heritage as a layered system of cultural and natural values within urban space. It promotes integrated, participatory governance, emphasizing heritage as crucial to identity, economic growth, and resilience in rapidly evolving cities [11]. The implementation of the HUL approach progresses while integrating heritage conservation into broader urban development processes [12]. However, its practical application faces ongoing challenges due to institutional fragmentation, overlapping mandates, and competing stakeholder priorities, which often cause coordination failures [2,13,14].

Despite ongoing recognition of stakeholders as key actors in HUL implementation processes, the scientific literature remains descriptive mainly, focusing on broad, categorical roles rather than systematically analyzing stakeholder interactions through their objectives and interdependencies [9,13]. As a result, the influence of stakeholder interactions on the practical implementation of HUL has not been thoroughly investigated, leaving a gap in operational models that can reflect the complexity of stakeholder interactions. This article addresses this gap by synthesizing stakeholder objectives documented in existing scientific literature and by organizing them within a conceptual system dynamic (SD) framework. This article compiles and structures previously documented key stakeholders and their objectives while interpreting their potential interdependencies within the HUL implementation process in Türkiye. This article conceptualizes these interactions through a causal loop diagram to illustrate plausible interaction pathways, acknowledging that these representations do not capture the full empirical complexity of real-life stakeholder dynamics. The diagram is therefore conceptual, synthesizing existing knowledge to propose an interpretive representation rather than an empirically validated analysis of stakeholder interactions. This approach shifts from static description toward dynamic conceptualization, providing an interpretive tool that offers structural insight into interdependencies and feedback mechanisms. Ultimately, this article aims to outline critical considerations for each stakeholder and to provide a comprehensive stakeholder engagement framework that emphasizes the essential interactions needed for successful HUL implementation.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Concept and Global Applications

UNESCO’s HUL approach emphasizes a significant shift in conservation thinking by integrating heritage into sustainable urban development. It broadens the definition of heritage beyond monuments to cover open spaces, spatial layout, and intangible practices that shape urban identity [10]. The HUL approach emphasizes integrated governance, stakeholder involvement, and the balancing of conservation with growth [11].

Practical application of the HUL approach has been tested in many locations, including Ballarat (Australia), Cuenca (Ecuador), Shanghai and Suzhou (China), and Rawalpindi (Pakistan), with additional cases in Zanzibar (Tanzania), Naples (Italy), and Amsterdam (The Netherlands) [15,16].

In Ballarat, efforts focused on participatory planning and linking heritage with economic growth [17,18]. A wide-ranging consultation, called “Ballarat Imagine,” was carried out throughout the process. The civil society and local government collaborated to develop a shared vision for the city’s future. As a result, cultural heritage has become a key driver of tourism and the creative industries. Therefore, the city is seen as one of the most successful examples of the HUL approach in practice [15,16].

In Cuenca, heritage preservation remains a central goal despite modernization pressures on the historic center [19]. In practice, UNESCO-supported programs have balanced urban development with the conservation of historical heritage. Development boundaries have been established to prevent damage to the historic fabric. As a result, Cuenca’s historic center has been preserved and has become a cornerstone of urban identity and tourism [15,16].

In Shanghai and Suzhou, the focus was on integrating historic heritage areas into planning during rapid modernization [20,21]. In practice, Shanghai’s lilong houses and historic neighborhoods have been prioritized for transformation. In Suzhou, water towns and traditional gardens have been seamlessly integrated into the city’s planning. Consequently, heritage was not viewed as an obstacle to development but as an essential part of planning [15,16].

In Rawalpindi, the primary objective was to promote community participation and capacity building [22]. In practice, residents were involved in decision-making. Public ownership of heritage was strengthened through educational programs, craft activities, and cultural events. Conservation efforts included not only physical restoration but also social development [15,16].

In Zanzibar, the aim was to protect Stone Town’s heritage, which was under pressure from tourism [23,24]. Strategies for sustainable tourism and visitor management were developed. Social benefits were prioritized to ensure local people were not excluded. Tourism revenues supported restoration, and social justice for local communities was safeguarded [15,16].

In Naples, the project aimed to enhance the identity of the historic center and its connection with modern life [25,26]. Conservation and renovation projects followed HUL principles in Naples’ UNESCO World Heritage Site. Residential and public spaces were improved within the narrow streetscape. As a result, the historic center remains a vibrant living space, strengthening the community’s sense of belonging [15,16].

In Amsterdam, the focus was on integrating heritage within the historic canal belt alongside climate change and sustainability strategies [27]. Historic buildings were included in climate change adaptation retrofit projects. Cultural heritage was viewed as an integral part of urban sustainability. Consequently, Amsterdam became one of the first cities addressed by HUL in the context of climate change adaptation [15,16].

These projects demonstrated how the HUL approach can incorporate heritage into planning while adapting historic housing and infrastructure and promoting inclusive governance. The HUL approach implementation across its applications underlined the importance of multi-stakeholder engagement. However, they also highlighted ongoing challenges, including institutional fragmentation, limited legal support, and competing development pressures [8,13,28].

2.2. Historic Urban Landscape (HUL)’s Legislative Status in Global Applications

In Australia, cultural heritage protection is carried out through state-based laws [29]. The HUL approach was incorporated into existing state conservation statutes. Additionally, HUL principles are integrated into the planning document “Ballarat Strategy.” As a result, they have been directly embedded into planning laws without the need for new legislation.

In Ecuador, the 2008 Constitution defines cultural heritage as part of development policies. In Cuenca, the HUL approach has been aligned with the national “Ley Orgánica de Cultura” [19]. Regulations supported by UNESCO have imposed building restrictions in the historic center.

In China, heritage protection is governed by the 1982 Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics [30,31]. After 2010, the protection of cultural landscapes was incorporated into the Urban and Rural Planning Law [32]. In Shanghai and Suzhou, the HUL approach was applied by adapting these laws to local regulations.

In Pakistan, there is no strong HUL integration at the national level. However, some pilot projects have been carried out through regional laws such as the Punjab Heritage Foundation Act [33]. In Rawalpindi, HUL has been mainly supported by local regulations and UNESCO projects.

In Tanzania, a special law was enacted for the historic center, called the Stone Town Conservation and Development Authority Act [34]. After 2010, this law was aligned with the HUL approach. Planning laws have been revised to strike a balance between tourism and heritage protection.

In Italy, a comprehensive legal framework exists called the ‘Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio’ [35]. UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Naples were designated under this law. The HUL approach is not introduced through a new law but integrated into the existing broad cultural heritage legislation.

In the Netherlands, heritage protection is governed by the Heritage Act [36,37]. In Amsterdam, the HUL approach have been embedded into spatial planning laws, especially in the canal belt area. Additionally, the Environment Act combines heritage, environment, and planning into a unified framework.

Overall, Zanzibar and Ecuador are the countries that have enacted new legislation. Australia, China, Italy, and the Netherlands have utilized existing legal frameworks to address these issues. Pakistan remains largely at the regional or local regulation level. Therefore, the HUL approach has not been directly incorporated into national laws; however, most countries have attempted to implement it by integrating it into existing conservation and planning laws.

The global scientific literature recognizes the HUL approach as a transformative shift in heritage management, successfully embedding cultural values within broader sustainable urban development agendas and encouraging inclusive, multi-stakeholder governance frameworks [2,8,10]. Scholars have highlighted how this approach can enhance the integration of conservation priorities with urban development goals, while also acknowledging significant barriers, including fragmented governance, competing institutional priorities, and limited implementation capacity [13,28].

Globally, the HUL approach operates more as a flexible, voluntary guideline than as a strict law. Its versatility allows for local adaptation, but it depends on strong institutions and cross-sector collaboration. Scholars have emphasized both its potential to transform heritage and the challenges posed by governance fragmentation and limited capacity [2,13,28].

2.3. Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Concept and Applications in Türkiye

In Türkiye, the HUL approach has primarily been discussed in terms of implementation prerequisites [38], the integration of cultural and ecological values into urban planning [39], and its influence on shaping identity [40]. Scholars emphasize the need for multidisciplinary approaches and legal reforms [41], but the practical implementation of these efforts encounters significant obstacles due to overlapping institutional authorities, fragmented legislation, and weak coordination mechanisms.

The Turkish planning system operates through a multi-level hierarchy comprising national, regional, and local plans, with conservation plans often developed separately from the main zoning frameworks [42]. This separation creates spatial gaps, where historic areas risk becoming disconnected from broader urban development. Several institutions, including the Ministries of Culture and Tourism, Forestry and Water Affairs, and Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change, contribute to the complexity, resulting in fragmented responsibilities and overlapping planning documents [43].

This institutional fragmentation undermines effective conservation and threatens the sustainability of preservation efforts. Turkish scientific literature emphasizes the importance of integrating cultural and ecological values into planning processes and aligning national frameworks with international standards, such as the HUL approach [38,44]. Without structural reforms, stakeholder involvement remains limited, and cultural heritage continues to face growing risks.

2.4. Stakeholder Engagement in the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Applications

The global scientific literature recognizes the HUL approach as a key transformation in heritage management, successfully integrating cultural values into broader sustainable urban development agendas and promoting inclusive, multi-stakeholder governance frameworks [2,8,10]. Scholars emphasize how this approach could enhance the effective integration of conservation priorities and urban development goals, while also highlighting significant barriers caused by fragmented governance structures, competing institutional priorities, and limited implementation capacity [13,28]. Conversely, the Turkish scientific literature mainly focuses on regulatory and institutional barriers to implementing the HUL approach, including insufficient institutional skills, poor coordination mechanisms, and the lack of cohesive participatory governance structures [38,39,40,41].

Although stakeholders are consistently recognized as central actors in HUL implementation, the existing scientific literature remains mostly descriptive, emphasizing broad roles rather than systematically analyzing stakeholder interactions in terms of their objectives and interdependencies [9]. Ref. [45] provides strategic tools for stakeholder identification and prioritization, yet without examining how stakeholders’ objectives interact. Ref. [46] analyzes collaboration among heritage managers, tourism actors, and local communities, but their assessment focuses on cooperative processes rather than systemic interdependencies. Ref. [47] explores negotiation dynamics in contested heritage environments, though their study does not translate stakeholder relations into an operational model. Complementary studies in the heritage field recognize the importance of multi-actor coordination [48,49,50,51], yet these approaches neither conceptualize stakeholder objectives as interacting variables nor identify the feedback mechanisms through which these interactions influence decision-making. Consequently, despite acknowledging the importance of stakeholders, the existing scientific literature does not provide a dynamic framework that captures how stakeholder objectives reinforce or balance one another within the implementation of the HUL approach. In other words, neither the global nor the Turkish contexts have been thoroughly examined to understand how stakeholder interactions influence the practical implementation of HUL, leaving a gap in operational models that can capture the complexity of stakeholder interactions in Türkiye.

2.5. Systems Thinking Approach for Stakeholder Engagement in the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) Applications

Stakeholder interactions are affected by nonlinear dynamics, in which shifting alliances, changing objectives, and feedback mechanisms often yield unexpected or unintended outcomes [52]. These dynamics are consistent with what systems thinkers refer to as dynamic complexity, where interdependencies, time delays, and feedback loops produce emergent, path-dependent trajectories [53,54]. Conventional descriptive or linear approaches fall short here, as they do not adequately view stakeholders as adaptive actors with changing roles, capacities, and goals [55].

To address this complexity, this article adopted a systems thinking approach, which views socio-technical contexts as an integrated whole where outcomes result from interactions, interdependencies, and feedback processes. This perspective enables moving beyond static classifications of stakeholders toward a more dynamic understanding of how their interactions shape trajectories over time. The importance of systems thinking in implementing the HUL approach is increasingly recognized [56,57,58], highlighting its role in providing both theoretical justification and analytical guidance essential for exploring the complexity involved in its implementation.

Systems thinking draws on various methodological tools from complex systems science, primarily agent-based simulation (ABM) and system dynamics (SD). These are the most commonly used tools in socio-ecological and urban systems modeling due to their ability to represent feedback, nonlinearity, and emergent behaviors [59]. The ABM examines how interactions among diverse agents affect overall system behavior at micro- and meso-scale applications [60]. It has been widely applied in urban analytics for modeling land-use change, urban mobility, and governance processes [57]. However, its use in the HUL implementation process, especially regarding stakeholder interactions, is limited by its focus on independent rather than interdependent actors. Conversely, the SD investigates how system structure influences the behavior of complex, evolving systems at meso- and macro-scale applications. It has been used in the HUL process. For example, Ref. [56] carried out an SD analysis as part of a longitudinal study to critically assess existing paradigms for heritage-led urban regeneration and proposed a new framework centered on community engagement and sustainable lifestyles. Additionally, Ref. [58] emphasized a critical SD approach that captures both visible and invisible dynamics of urban heritage transformation, advocating for the integration of intangible values into heritage-led urban regeneration.

This article not only adds to the global scientific literature by introducing a new methodological application but also fills specific gaps in the Turkish context, providing insights into how stakeholder engagement can be improved in implementing the HUL approach.

3. Methodology

In this article, the SD tool has been chosen since it is better suited thanks to its focus on meso-scale application and its interdependency perspective on the complexity of the HUL implementation process through stakeholder interactions.

The SD tool operates through an iterative process of model creation, validation, and scenario analysis, with a focus on scope selection, dynamic hypothesis generation, causal loop diagramming, quantification, reliability testing, and scenario evaluation [53,61]. This process involves constructing the causal loop diagram to identify variable interactions and determine both balancing and reinforcing loops [62]. Subsequently, a stock-flow diagram is developed based on the causal loop diagram [63]. The SD model uses these diagrams, which include three types of variables: stocks, flows, and auxiliary variables [53]. Ultimately, the SD model is built through simulation models, testing, reliability assessments, and further scenario analysis [64,65].

The methodological approach was carried out in two steps: problem articulation and system conceptualization. The problem articulation step organized stakeholder groups, subgroups, and key stakeholders, along with their documented objectives, by drawing on existing scientific sources. This article systematically categorized its objectives into six thematic clusters: managerial, economic, social, cultural, conservation, and sustainable urban development. These thematic clusters reflected the multidimensional structure of heritage management, which integrates institutional, economic, social, cultural, environmental, and sustainability-related dimensions, as recognized by UNESCO’s HUL approach [10]. This enabled an interpretable structure for system conceptualization, allowing the SD model to organize heterogeneous stakeholder objectives into coherent domains. The system conceptualization step then aimed to connect stakeholder objectives to build the causal loop diagram. It also identified the balancing and reinforcing loops within the causal loop diagram. The SD model was not further developed through a stock-flow diagram during the system conceptualization step, nor were the formulation of simulation models, model testing, reliability assessment, and scenario analysis included.

The SD model was developed as a conceptual and structural framework, rather than a fully quantified simulation. Its primary purpose was to organize and interpret interactions among stakeholder objectives, without generating time-based simulations or predictive outcomes. Although the interconnections among variables were identified and visually depicted, no mathematical equations were applied, reflecting the predominantly qualitative and heterogeneous nature of the available data. Consequently, the SD model serves as an interpretive tool for examining stakeholder interactions, rather than a platform for numerical analysis.

The identification of interactions among stakeholder objectives relied exclusively on relationships documented in the existing scientific literature. These interactions represent generalized patterns, not empirically verified causal effects. Because the directionality and strength of such relationships may vary across contextual conditions, policy frameworks, institutional performance levels, and socio-economic dynamics, the model does not claim to reproduce real-world behavior. Instead, it synthesizes recurring interaction pathways reported in the scientific literature, acknowledging that actual effects may diverge and require further empirical validation. In this sense, the SD model functions as a heuristic representation that structures existing knowledge into a coherent system of interdependencies.

All modeling activities were conducted using Vensim PLE (Version 10.1.0). It was used exclusively as a structural modeling environment for visually constructing and organizing interactions among stakeholder objectives. The software’s diagramming functions enabled the identification of feedback loops and the structuring of the conceptual model, without employing its quantitative simulation features. Therefore, it served as a tool for conceptualizing the visual system, rather than for numerical modeling or dynamic simulation. Accordingly, the SD model did not produce time-based simulations or predictive outcomes; instead, it provided a static structural representation intended to support interpretation and guide future SD model development.

The methodological novelty lies in applying the SD tool to address stakeholder interactions in the HUL implementation process in Türkiye. Interpreting the results from the SD model provides considerations for each stakeholder and produces a stakeholder framework model that highlights the necessary interactions for effective HUL implementation. This is the first systematic effort to model stakeholder interactions within the Turkish HUL context, offering an operational framework to understand governance complexity and identify considerations for better coordination. Although previous studies [11,13,66] have acknowledged the vital role of stakeholders in the HUL implementation process, they generally remain descriptive, presenting stakeholder taxonomies and objectives without operational models that show their interactions.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Problem Articulation

The problem articulation was the initial step in the SD modeling process, aiming to define the system’s boundaries and focus on a specific issue rather than visualizing the entire system. This step has compiled the stakeholder groups, subgroups, and key stakeholders, documented in existing scientific literature, the HUL implementation process at the Turkish national level, according to [41,44], namely: Governmental institutions; Professional and academic institutions; Civil society and community; Private sector organizations; and international organizations and partners.

The governmental institutions comprised the national, regional, and local governments, as the stakeholder subgroups. The national governments included the Foundation General Directorate, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, and the Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change. On the other hand, the regional governments were referred to as the regional conservation board directorates, and the municipalities and local governments. The professional and academic institutions included universities, research institutions, museums, technology and innovation companies, and professional associations. Civil society and community were referred to as local communities, non-governmental organizations, the media, and cultural organizations. The private sector organizations were attributed to the developers and investors, banks and financial institutions, and tourism sector stakeholders. Finally, the international organizations and partners were principally UNESCO and other conservation bodies. The objectives of these key stakeholders were designated, in accordance with [41,44] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Key stakeholders and their associated objectives (elaborated by the authors, based on [41,44]).

The stakeholders’ associated objectives were synthesized from existing literature and organized into thematic categories: managerial, economic, social, cultural, conservation, and sustainable development objectives.

Managerial objectives included collaboration and coordination, defined as facilitating inter-institutional and multi-stakeholder cooperation; policy-making and regulatory authority, defined as the development of policies, legal frameworks, and institutional mandates to guide conservation and urban development; implementation and enforcement, defined as the enactment and practical application of regulations, plans, and standards; and monitoring and evaluation, defined as the systematic oversight of heritage and urban development projects to ensure accountability and effectiveness.

Economic objectives included funding and resource allocation, which involves mobilizing and distributing financial resources to support conservation and development; economic viability and revitalization, which focus on integrating heritage into local economic systems and urban regeneration strategies; investment and incentives, aimed at attracting sustainable financial flows and implementing policies or fiscal measures to encourage conservation practices; and risk management, which involves anticipating and mitigating financial, operational, and environmental risks related to heritage and urban projects.

Social objectives encompassed community engagement and participation, emphasizing the active involvement of local stakeholders in planning, decision-making, and implementation; capacity building and education, focusing on enhancing knowledge, skills, and institutional capabilities for long-term stewardship; awareness and advocacy, aimed at promoting public understanding of the cultural, social, and environmental importance of heritage; and empowerment and inclusion, dedicated to advancing equity, fostering local ownership, and increasing agency in shaping heritage and urban development outcomes.

Cultural objectives included maintaining cultural identity and continuity, defined as preserving the intangible, symbolic, and lived aspects of heritage that sustain community traditions, and promoting and educating about culture, defined as increasing cultural visibility, appreciation, and intergenerational transmission through educational and outreach initiatives.

Conservation objectives included protecting and preserving heritage, defined as safeguarding tangible and intangible heritage resources from degradation or loss; re-storing and reusing historic assets, defined as rehabilitating heritage buildings and sites for modern purposes; managing sites and integrating planning, defined as aligning heritage site management with broader urban and territorial planning systems; and providing technical support, innovation, and research, defined as applying scientific methods, technological tools, and innovative approaches to improve conservation outcomes.

Sustainable urban development goals included long-term, cross-sector urban sus-trainability, defined as aligning heritage conservation with strategies for urban resilience and sustainable growth; integrating heritage with livability and growth, defined as incorporating cultural assets into urban quality of life, service delivery, and development planning; and ensuring environmental and climate sensitivity in planning, defined as systematically applying ecological principles and climate adaptation strategies into heritage and urban policy frameworks.

The process of implementing the HUL approach in Türkiye involves complex interactions among various stakeholders, each playing an essential role with specific responsibilities and objectives. National governments lead by developing policies, coordinating initiatives, and allocating resources to incorporate HUL principles into urban planning, thereby promoting sustainable development and preserving cultural heritage [10]. Regional governments play a vital role in the implementation phase, as they enforce conservation laws, oversee heritage sites, foster collaboration among stakeholders, and integrate heritage preservation into broader sustainability strategies, thereby ensuring historical and cultural authenticity in urban areas [67,68]. Local governments act as the operational link, translating national policies into practical plans, mobilizing resources, and engaging local communities in conservation efforts [69]. Professional and academic institutions play a crucial role in providing expertise, conducting research, and offering technical support, thereby fueling innovation and building capacity in heritage management. Meanwhile, civil society and communities actively participate through grassroots advocacy, raising awareness, and ensuring that conservation efforts are inclusive and aligned with the values and needs of local populations [70,71]. The private sector also plays a crucial role by providing investment and financial support, as well as collaborating with other stakeholders to strike a balance between profit-making and heritage preservation. International organizations and partners complement these efforts by providing guidance, technical assistance, and funding, while sharing global best practices and enhancing the capabilities of local stakeholders [10].

Despite their individual mandates, these stakeholders often share overlapping objectives, resulting in connections across institutional levels. This synergy fosters collaboration and effective communication, resulting in a unified working environment. As a result, stakeholders realize their interdependence and the value of each other’s contributions in successfully implementing the HUL approach. Together, they build a dynamic ecosystem dedicated to protecting Türkiye’s historic urban landscapes, ensuring their sustainability for future generations while enriching the country’s cultural heritage.

4.2. System Conceptualization

The system conceptualization was the second step in the SD modeling process, aiming to develop the “dynamic hypothesis” to understand the system. This step was meant to interpret the behavior of the defined problem through the causal loop diagram and the model’s feedback loops [53].

This step was also used to identify the stakeholders’ indirect objectives. The causal loop diagram was created based on the stakeholders’ interactions with their direct objectives. Then, the feedback loops were identified from the causal loop diagram.

4.2.1. Causal Loop Diagram Construction

The causal loop diagram was developed using a structured methodological approach. First, stakeholders’ objectives were identified as variables, and their direct interconnections were shown with directional arrows within the diagram. The stakeholders themselves were not included as variables because they could not be quantified or qualified as data.

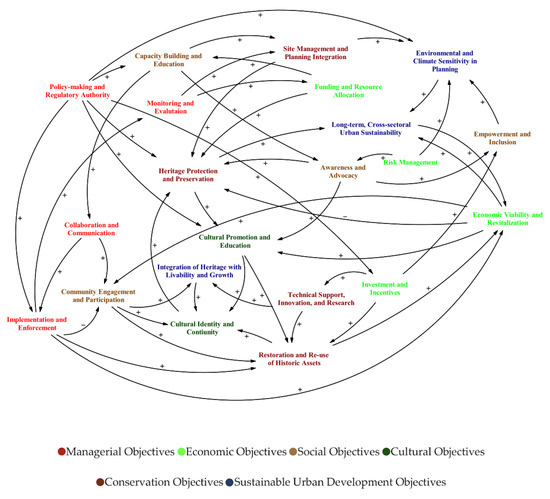

The causal loop diagram (Figure 1) was created using a color-coded scheme, with managerial objectives shown in red, economic objectives in green, social objectives in brown, cultural objectives in dark green, conservation objectives in burgundy, and sustainable urban development objectives in dark blue. Arrows depict interactions; black arrows indicate direct links between stakeholders’ related objectives. A positive interaction between variables is shown by a plus sign (+), while a negative interaction is shown by a minus sign (−).

Figure 1.

Causal loop diagram (elaborated by the authors). Black arrows indicate direct causal interactions; A plus sign (+) indicates a positive interaction; A minus sign (−) indicates a negative interaction.

Furthermore, internal interactions among stakeholders’ related objectives were derived from the existing scientific literature, and they reflect generalized patterns rather than empirically validated relationships. These interactions illustrate how objectives may influence or be influenced by one another under certain conditions. The network of direct interconnections was therefore examined conceptually to explore how objectives tend to support, reinforce, or balance each other within the system, acknowledging that these effects can vary according to context, institutional capacity, and policy design. Collaboration and coordination are commonly associated with stronger community engagement, more inclusive participation, and improved implementation and enforcement, thereby facilitating multi-actor cooperation [72]. Policy-making and regulatory authority can stimulate investment and incentives, strengthen implementation and enforcement, support capacity building and education, promote cultural activities, ensure heritage protection and preservation, and increase environmental and climate awareness in planning when policies are well-aligned with governance capacities [73]. Implementation and enforcement can, in turn, support economic viability, revitalization, restoration, and the reuse of historic assets, while also reinforcing monitoring and evaluation processes and helping balance community engagement and participation [74]. Monitoring and evaluation are frequently linked to improved funding, resource allocation, site management, and planning integration, contributing to institutional learning [75]. Funding and resource allocation may enhance capacity building, education, and heritage protection and preservation by ensuring more effective targeting of resources [73]. Economic viability and revitalization often foster community engagement and participation, support cultural promotion and education, and strengthen long-term, cross-sector urban sustainability [76]. Investment and incentives can support inclusion, encourage the restoration and reuse of historic assets, and stimulate technical support, innovation, and research when they are designed to avoid displacement and ensure equitable distribution of benefits [73]. Risk management tends to increase awareness and advocacy, promoting environmental and climate sensitivity in planning [77]. Community engagement and participation may nurture cultural identity and continuity, support the restoration and reuse of historic assets, and help integrate heritage into broader notions of livability and growth [78]. Capacity building and education frequently improve site management, planning integration, and collaboration and coordination among actors [79]. Awareness and advocacy are closely linked to advancements in cultural promotion and education, heritage protection, and empowerment and inclusion [73]. Empowerment and inclusion can strengthen environmental and climate sensitivity in planning [80]. Cultural identity and continuity may support heritage protection and preservation, while cultural promotion and education can encourage the restoration and reuse of historic assets [81]. Heritage protection and preservation often contribute to long-term, cross-sector urban sustainability, which, in turn, supports economic viability and revitalization [82]. The restoration and reuse of historic assets may reinforce economic viability and revitalization, while improved site management and planning integration can enhance environmental and climate awareness in heritage protection and preservation [83]. Technical support, innovation, and research commonly promote the integration of heritage with livability and growth, while advancing the restoration and reuse of historic assets [84]. Finally, environmental and climate awareness in planning tends to reinforce long-term, cross-sector urban sustainability [85].

The results are presented for each stakeholder. Although stakeholder variables were not included in the causal loop diagram, the results were obtained by analyzing their direct interconnections with their related objectives and then finding the shortest path between the objective variables. In this way, the logical bridge between the causal loop diagram and the stakeholder-specific interpretations are established. The analysis traces how each stakeholder’s objectives connect within the feedback structure of the system, allowing to interpret their indirect influence paths, rather than inferring stakeholder behavior directly. Therefore, the stakeholder narratives do not represent additional data collection but a systematic translation of the diagrammed interactions into stakeholder-specific analytical insights.

The Foundation General Directorate contributes to national heritage governance by coordinating regulatory frameworks, funding mechanisms, and conservation practices. Through its regulatory and policy functions, it supports investment mechanisms, helping to revitalize heritage areas by establishing stable legal conditions for funding and project success [10]. Its monitoring and evaluation activities improve the effectiveness of funding distribution, fostering professional growth and learning within heritage management [86]. Managing funding resources also strengthens heritage protection by ensuring that conservation programs are financially sustainable and accountable [87]. Additionally, its involvement in technical research enhances restoration quality and drives innovation across heritage projects, encouraging adaptive methods and data-driven documentation [88]. While strict enforcement procedures may sometimes restrict community participation, inclusive regulatory communication can turn this into a positive collaboration. It should coordinate legislative, financial, and technological tools to create a transparent, participatory framework that aligns heritage protection with sustainable urban development, ensuring the effective implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye.

The Ministry of Culture and Tourism serves as a bridge, linking cultural vitality, public engagement, and economic development. Its investment programs support the restoration and reuse of historic assets by promoting heritage-focused projects that combine economic benefits with conservation [89]. Its focus on economic sustainability enhances civic involvement, as vibrant heritage districts encourage residents and local organizations to participate in conservation efforts [90]. Additionally, advancements in cultural education influence the planning of livable, culturally cohesive urban areas, integrating heritage into everyday life [91]. Public communication and awareness campaigns also help strengthen institutional capacity by fostering public support and shared understanding of heritage values [92]. It should unify investment and cultural-education initiatives within participatory planning strategies that balance heritage preservation with inclusive social and economic growth, ensuring the successful implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye.

The Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry strengthens the ecological dimension of heritage management by integrating natural-resource planning with cultural landscape considerations. Its awareness and advocacy efforts enhance heritage protection by elevating public understanding of the ecological and cultural significance of landscapes [93]. Environmental awareness enhances cultural identity and continuity, reinforcing the view of nature and culture as interconnected aspects of place [94]. Its coordination of site management policies enhances environmental sensitivity in planning processes, supporting the long-term sustainability of heritage sites [95]. Additionally, it helps maintain the economic stability of local communities that depend on balanced resource use by incorporating conservation principles into forest and water management [96]. It should integrate environmental governance with cultural-heritage planning, ensuring that ecological conservation and cultural preservation work together as mutually supportive goals to implement the HUL approach in Türkiye effectively.

The Ministry of Environment, Urbanization, and Climate Change shapes urban sustainability and environmental planning through its regulatory authority and spatial-planning responsibilities. Its participation in site management and planning integration enhances institutional capacity and professional development by implementing sustainability standards in urban planning [97]. Environmental awareness in planning ensures the long-term resilience of heritage sites and fosters innovation in conservation technology [98]. Its commitment to heritage protection indirectly promotes cultural awareness and educational efforts that link spatial design with heritage interpretation [99]. It also boosts the economic and social stability of urban communities, where heritage is a vital part of urban identity, by coordinating these interconnected areas [100]. The ministry should establish cross-sector planning frameworks that integrate environmental management, cultural preservation, and community education within a unified policy framework to implement the HUL approach in Türkiye effectively.

The Regional Conservation Board Directorates guide heritage conservation processes through site evaluations, regulatory enforcement, and monitoring activities. They enhance financial accountability and improve institutional learning by connecting evaluation results with funding decisions through their monitoring duties [101]. Their enforcement of regulations promotes the restoration and reuse of historic assets while ensuring that adaptive projects meet heritage-conservation standards [102]. Their policy roles encourage investment and stimulate local economic activity by clarifying regulatory procedures and enabling project approval [103]. However, overly strict enforcement may discourage civic engagement, highlighting the need for participatory compliance mechanisms [73]. They should adopt inclusive monitoring and enforcement systems that balance regulatory accuracy with stakeholder involvement and local knowledge to implement the HUL approach in Türkiye effectively.

Municipalities and local governments operationalize heritage implementation by managing spatial planning, community engagement, and local resource allocation. Their implementation and coordination efforts indirectly shape national policy by providing localized data and experience that inform regulatory updates [104]. Engaging with citizens strengthens cultural identity, raises awareness of urban heritage, and encourages voluntary participation in maintenance and monitoring activities [105]. Managing restoration projects also contributes indirectly to economic revitalization, which in turn supports social well-being and livability [106]. Additionally, their sustainability initiatives indirectly promote environmental awareness, integrating heritage protection into climate-adaptation and urban-resilience strategies [107]. They should establish participatory planning mechanisms that incorporate community involvement, environmental responsibility, and heritage preservation across all local development plans to ensure the effective implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye.

Universities and research institutes support evidence-based decision-making by generating scientific knowledge, developing analytical tools, and providing technical expertise. Their advisory work in policy development indirectly enhances professional education and institutional capacity across the heritage sector [108]. Research dissemination promotes cultural awareness and public understanding, ensuring conservation is informed by scientific and social insights [109]. Technological innovations from academic projects improve restoration quality and foster experimentation with new materials and documentation methods [110]. They support sustainable management and train future experts by bridging theoretical knowledge with practical application [111]. They should prioritize interdisciplinary research and curricula that link policy innovation, technology, and community participation in heritage planning to implement the HUL approach in Türkiye effectively.

Museums enhance public understanding of heritage by offering educational programs, exhibitions, and interpretive activities. Cultural exhibitions and learning programs generate public interest in restoration and reuse initiatives, stimulating heritage-based economic activity [112]. They foster community engagement and cultural continuity by providing spaces for interaction and education [113]. Their commitment to conservation contributes to long-term sustainability by embedding awareness of heritage values into everyday cultural life [114]. They should function as inclusive civic institutions that connect cultural education with active public participation in heritage stewardship to implement the HUL approach in Türkiye successfully.

Technology and innovation companies facilitate the digital transformation of heritage management by providing advanced monitoring, documentation, and analytical tools. Their research and development efforts improve restoration techniques, project monitoring, and digital documentation, boosting the efficiency and transparency of conservation processes [115]. Technological innovation also enhances urban life by making it easier to integrate heritage assets into modern environments [116]. They further contribute to cultural identity and accessibility by creating digital archives and visualization tools that enable communities to experience and interpret their heritage [117]. Collaboration with public institutions is essential for delivering innovative solutions that improve heritage documentation, monitoring, and citizen engagement, supporting the practical application of the HUL approach in Türkiye.

Professional associations influence conservation quality and consistency by delivering training programs and establishing professional standards. Their coordination efforts lead to more consistent implementation by harmonizing professional practices across institutions [118]. Training programs organized by these bodies improve integration between site management and planning, thereby strengthening heritage protection [119]. Additionally, they serve as channels for sharing expertise and ethical principles across the professional community [120]. Continuing to promote professional education, ethical standards, and interdisciplinary collaboration is vital for maintaining consistent conservation practices nationwide and for the successful implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye.

Local communities sustain the authenticity and continuity of heritage by engaging in participatory processes, maintaining cultural practices, and transmitting local knowledge across generations. Their participation in collaborative processes fosters restoration and reuse projects, thereby boosting local economic growth and social inclusion [121]. Empowerment initiatives enhance environmental awareness within planning and management, ensuring that local knowledge guides sustainable decisions [122]. Cultural identity in communities supports heritage conservation by reinforcing collective responsibility and the transmission of values across generations [123]. They should remain actively involved as co-managers of heritage sites, ensuring that conservation practices respect local needs, traditions, and values to implement the HUL approach in Türkiye effectively.

Non-governmental organizations enhance participatory governance by advocating for cultural and environmental values, mobilizing public awareness, and facilitating dialogue between institutions and citizens. Their engagement in policy discussions strengthens capacity-building by transferring knowledge from civil society to government frameworks [124]. Advocacy and educational programs raise cultural awareness and defend heritage, fostering wider societal support for conservation [125]. Empowerment initiatives led by these organizations reinforce environmental planning by linking social justice with sustainable land-use management [126]. They should facilitate transparent dialogue between citizens and authorities, ensuring that community perspectives inform policy development and project execution to apply the HUL approach in Türkiye effectively.

Media institutions shape public perceptions of heritage by disseminating information, fostering accountability, and generating wider awareness of conservation-related issues. Its activities promote transparency in funding and project implementation, building trust among stakeholders through investigative reporting and public outreach [127]. Educational and cultural programs increase public understanding of heritage values, encouraging active involvement in preservation efforts [128]. Additionally, consistent media coverage of planning processes helps integrate heritage considerations into urban policies [129]. It should focus on ongoing heritage communication, raise awareness, and foster civic responsibility to protect historic urban environments, ensuring the successful application of the HUL approach in Türkiye.

Cultural organizations reinforce identity formation and cultural continuity by developing artistic programs, organizing community-oriented events, and promoting the visibility of intangible and tangible heritage. Their artistic and educational activities support restoration and reuse projects by increasing cultural visibility and stimulating creative industries within heritage contexts [91]. Efforts to preserve cultural identity strengthen conservation by aligning heritage protection with community values and traditions [130]. Public engagement programs raise awareness and foster appreciation of urban heritage, transforming cultural activities into long-term stewardship mechanisms [131]. They should develop inclusive cultural programs that reinforce local identity and link artistic expression with the safeguarding of historic urban spaces to effectively implement the HUL approach in Türkiye.

Developers and investors influence the trajectory of heritage areas by making investment decisions that affect adaptive reuse, urban revitalization, and the integration of conservation principles into development projects. Their investment initiatives indirectly promote innovation in restoration and technical applications, leading to higher standards in adaptive reuse projects [132]. Well-managed development enhances sustainability and social participation by creating viable, well-maintained heritage assets that generate employment and community involvement [83]. The economic viability of projects supports the continuation of heritage functions, ensuring long-term maintenance and usage [133]. They should align their financial strategies with heritage-sensitive planning principles, emphasizing authenticity, quality, and inclusiveness in all interventions to successfully implement the HUL approach in Türkiye.

Banks and financial institutions determine the financial feasibility of heritage initiatives by allocating credit, evaluating risks, and structuring funding mechanisms for conservation and adaptive reuse. They support training and education activities, boosting the technical capacity of both public and private actors through financial backing [134]. Their funding of conservation programs strengthens heritage protection by ensuring ongoing preservation efforts [135]. Risk-management practices foster environmental awareness, encouraging sustainable investment behavior and responsible urban planning [136]. They should incorporate cultural and environmental assessment criteria into funding decisions, thereby reinforcing the sustainability and accountability of heritage projects and effectively executing the HUL approach in Türkiye.

Tourism stakeholders contribute to the economic and cultural vitality of heritage sites by shaping visitor experiences, promoting destination identity, and supporting the maintenance and adaptive use of historic assets. Their efforts to promote culture strengthen identity and continuity by emphasizing the importance of heritage within the tourism narrative [137]. Reusing heritage buildings for tourism supports sustainability by ensuring ongoing maintenance and functional adaptation [138]. Tourism activities also encourage civic participation and boost local economies, motivating broader conservation efforts [139]. They should adopt heritage-sensitive management approaches that balance visitor experience with authenticity, preservation, and the well-being of local communities to effectively implement the HUL approach in Türkiye.

UNESCO and other conservation bodies provide overarching guidance by offering international frameworks, technical support, and capacity-building programs that inform national and local heritage governance. Their coordination programs enhance collaboration among institutions and communities, reinforcing participatory governance [140]. They support training and capacity-building initiatives that raise professional and administrative standards through evaluation and funding mechanisms [141]. Their promotion of innovation and technical guidance improves the quality of restoration and the economic performance of heritage projects [142]. They advance the long-term sustainability of heritage systems by incorporating environmental sensitivity into policy frameworks [10]. They should continue to facilitate multi-level collaboration, technical support, and policy alignment to unify national and local efforts within a coherent heritage management vision, enabling effective implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye.

As the causal loop diagram represents the existing stakeholder engagement mapping for the HUL approach implementation in Türkiye, the results showed that each stakeholder’s indirect objectives play a significant role in achieving effective implementation.

4.2.2. Feedback Loop Identification

The interconnections among variables are not limited to straightforward, one-way interactions; instead, they can influence each other in circular patterns known as feedback loops. These loops occur when variables exert mutual effects, either amplifying or counteracting the system’s dynamics. When variables influence each other positively, a reinforcing loop is created, leading to continuous growth or escalation. Conversely, a balancing loop happens when a negative interaction between variables counteracts change and stabilizes the system. In the causal loop diagram (Figure 1), two balancing and four reinforcing loops were identified.

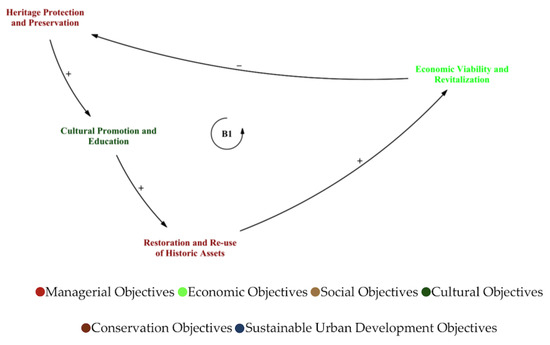

The B1-balancing loop (Figure 2) represents the interaction between economic development and heritage conservation through cultural initiative restoration and reuse activities. Heritage protection boosts cultural promotion and education, thereby increasing public appreciation and encouraging the restoration and reuse of historic assets [81]. These activities eventually contribute to greater economic viability and revitalization [119]. However, as activities accelerate, increased commercial activity in historic urban landscapes could threaten the authenticity and integrity of heritage resources [143]. This feedback loop underscores the importance of avoiding overexploitation of heritage for profit. It also highlights, especially in Türkiye, the need to align economic viability and revitalization policies with preservation and conservation priorities to maintain a balance between economic development and heritage conservation.

Figure 2.

B1-balancing loop (elaborated by the authors). Black arrows indicate direct causal interactions; A plus sign (+) indicates a positive interaction; A minus sign (−) indicates a negative interaction.

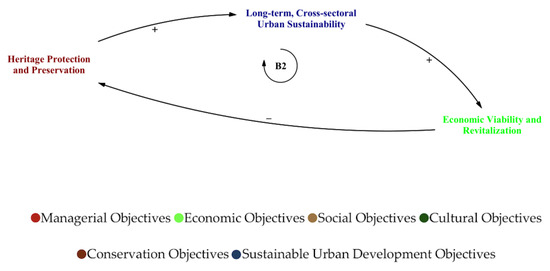

The B2-balancing loop (Figure 3) illustrates how economic growth and heritage conservation interact within urban sustainability. Heritage protection and preservation enhance long-term and cross-sectional urban sustainability by safeguarding cultural assets and integrating them into sustainable development frameworks [3]. Increased urban sustainability further boosts economic viability and revitalization by enhancing urban attractiveness, livability, and investment opportunities [144]. However, as economic growth accelerates, it can threaten heritage protection and conservation [145]. This feedback loop underscores the need to manage the trade-off between economic development and conservation integrity in sustainable urban growth. It also highlights, particularly in Türkiye, the importance of adopting sustainability-focused policies that connect heritage management with economic progress without sacrificing the authenticity and long-term preservation of historic urban landscapes.

Figure 3.

B2-balancing loop (elaborated by the authors). Black arrows indicate direct causal interactions; A plus sign (+) indicates a positive interaction; A minus sign (−) indicates a negative interaction.

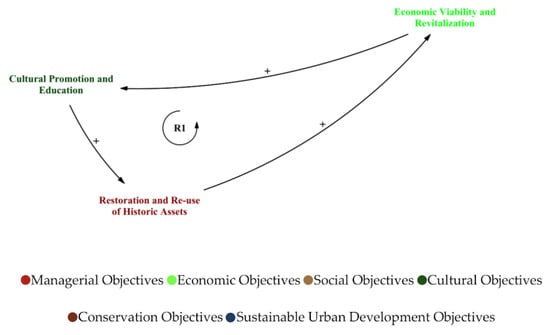

The R1-reinforcing loop (Figure 4) represents economic growth, restoration, and reuse activities driven by cultural initiatives. Cultural promotion and education increase stakeholders’ awareness of their involvement and foster a deeper appreciation for heritage values, encouraging the restoration and reuse of historic assets [146]. The improvement of restoration and reuse of historic assets subsequently supports economic viability and revitalization by attracting investment, tourism, and creative industries [119]. This economic growth then boosts cultural promotion and education by providing the necessary financial and institutional backing for further cultural initiatives [73]. This feedback loop illustrates how cultural and economic aspects of heritage conservation and preservation can strengthen one another when managed within an integrated framework to restore and reuse historic assets. It also highlights, specifically in Türkiye, the potential of culture-led development as a catalyst for sustainable urban growth, where heritage-age-driven economic progress continuously enhances cultural awareness and preservation practices.

Figure 4.

R1-reinforcing loop (elaborated by the authors). Black arrows indicate direct causal interactions; A plus sign (+) indicates a positive interaction; A minus sign (−) indicates a negative interaction.

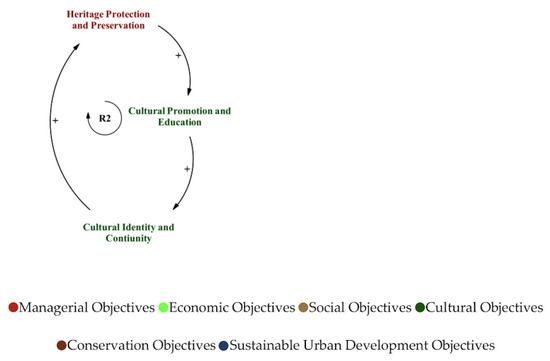

The R2-reinforcing loop (Figure 5) illustrates the interaction between cultural awareness, identity, and heritage conservation. Cultural promotion and education support cultural identity and continuity by strengthening collective memory, social belonging, and appreciation of heritage values [73]. A strong sense of cultural identity among stakeholders increases their commitment to heritage protection and preservation, ensuring that cultural assets are valued and safeguarded [147]. Improved heritage protection then boosts cultural promotion and education [119]. This feedback loop demonstrates how the cultural aspects sustain heritage conservation. It also emphasizes, especially in Türkiye, the importance of integrating education, culture, and heritage management to build a self-sustaining system in which awareness and protection continually reinforce each other, thereby securing the cultural continuity of historic urban landscapes.

Figure 5.

R2-reinforcing loop (elaborated by the authors). Black arrows indicate direct causal interactions; A plus sign (+) indicates a positive interaction; A minus sign (−) indicates a negative interaction.

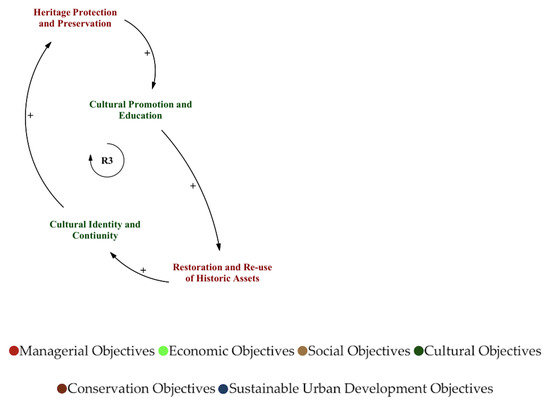

The R3-reinforcing loop (Figure 6) depicts the interaction between cultural awareness and identity through the restoration and reuse of historic assets aimed at heritage conservation. Cultural promotion and education encourage the restoration and reuse of historic assets by fostering awareness, appreciation, and engagement among stakeholders [148]. These activities strengthen cultural identity and continuity, reinforcing the community’s collective sense of belonging and appreciation for heritage values [149]. As cultural identity deepens, it enhances heritage protection and preservation, ensuring long-term stewardship of cultural assets. Improved heritage conservation, in turn, supports further cultural promotion and education [150]. This feedback loop demonstrates how the cultural dimensions are interconnected through the restoration and reuse of historic assets to sustain heritage conservation. It also highlights, especially in Türkiye, the potential of culture-based restoration policies to promote continuity, strengthen community engagement, and increase the resilience of historic urban landscapes.

Figure 6.

R3-reinforcing loop (elaborated by the authors). Black arrows indicate direct causal interactions; A plus sign (+) indicates a positive interaction; A minus sign (−) indicates a negative interaction.

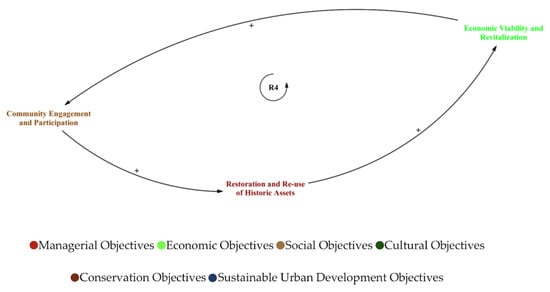

The R4-reinforcing loop (Figure 7) illustrates how economic growth and community participation interact through the restoration and reuse of historic assets. Restoring and reusing these assets boosts economic viability and revitalization by making local areas more attractive, creating jobs, and encouraging tourism and investment [151]. These economic benefits, in turn, increase community engagement and involvement, as stakeholders become more invested in heritage projects and recognize the shared value of cultural assets [132]. Greater participation then promotes further restoration and reuse of historic assets [152]. This feedback loop shows how economic growth relies on community involvement and how community efforts reinforce the restoration and reuse of historic assets. It also highlights, especially in Türkiye, the crucial role of community participation in maintaining heritage-based urban renewal, proving that inclusive engagement is key to the long-term economic and cultural health of historic city areas.

Figure 7.

R4-reinforcing loop (elaborated by the authors). Black arrows indicate direct causal interactions; A plus sign (+) indicates a positive interaction; A minus sign (−) indicates a negative interaction.

The feedback loops identified in the SD model clarify how stakeholder interactions shape the trajectory of HUL implementation. The balancing loops reveal the system’s stabilizing mechanisms, showing where counteracting dynamics limit or redirect progress. These loops highlight the structural boundaries within which stakeholder objectives operate and explain why improvements in one area may generate compensatory pressures in another. They therefore expose the system’s tendency to seek equilibrium, illustrating the institutional and governance constraints that can hinder coordination, weaken implementation, or dilute participation. Conversely, the reinforcing loops illustrate how specific stakeholder objectives may mutually strengthen each other, producing cumulative and accelerating effects. Under conditions of coherent governance, strengthened capacity, investment, community engagement, or institutional learning, these loops demonstrate how progress in one domain can amplify related objectives, increasing overall system momentum. They also identify leverage points in which small, well-targeted improvements may yield disproportionately significant impacts by indirectly supporting multiple stakeholders’ objectives. Together, they provide a systemic understanding of HUL implementation, revealing both the forces that drive progress and the structural limits that may constrain it. This dual perspective offers insight into where interventions may encounter resistance and where strategic alignment can generate sustained, collective advancement.

4.3. Discussion

This article demonstrates the applicability of the SD tool for conceptually representing stakeholder interactions that shape the implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye. By visualizing the interdependencies and feedback mechanisms influencing decisions across managerial, economic, cultural, social, conservation, and sustainable urban development domains, the model supports a systemic understanding of the HUL implementation process.

Existing scientific literature highlights the central role of stakeholders in advancing the HUL approach, emphasizing their influence on governance, participation, and policy outcomes [11,66]. Parallel studies employing the SD in heritage-led urban regeneration have revealed visible and invisible dynamics of urban transformation and argued for the integration of intangible values and community participation into heritage management [56,58]. However, these two strands of research remain largely disconnected. While studies describe stakeholder roles, collaboration, and negotiation in heritage governance [45,46,47], and others discuss the need for multi-actor coordination [48,49,50,51], they do not model how stakeholder objectives interact or how these interactions generate systemic behavior.

This article addresses this gap by integrating both perspectives into a unified analytical framework. The stakeholder-focused SD model visualizes the multi-layered relationships among stakeholder objectives, translating descriptive insights into a dynamic representation of feedback and interdependencies. In doing so, it moves beyond descriptive accounts and offers a structured foundation for strengthening coordination and decision-making in heritage governance.

The SD model’s results reveal how stakeholder objectives influence one another through feedback mechanisms, highlighting the nonlinear and adaptive nature of heritage conservation. By integrating variables derived from real-world heritage management practices, the SD model provides practical insights into how coordinated decision-making can address fragmentation and enhance cooperation among diverse actors.

Although institutional fragmentation is a major barrier to HUL implementation in Türkiye, the conceptual SD model does not attempt to resolve it directly. Rather, it identifies how fragmentation manifests structurally within the network of stakeholder interactions. By indicating where reinforcing mechanisms fail to form, where balancing effects slow progress, and where misaligned or weak connections disrupt coordination, the model exposes systemic bottlenecks that hinder effective governance. This diagnostic perspective clarifies which interactions require alignment, which institutional capacities need strengthening, and where governance interventions may be most effective. As such, it provides a theoretically informed basis for future policy design, empirical validation, and simulation-based analysis.

The interpretation of the SD model produced a set of actionable considerations (Table 2) that help stakeholders intervene more effectively by aligning their actions with their mandates, capacities, and interdependencies. This integrated understanding encourages a shift away from isolated or compliance-oriented practices toward proactive, cooperative, and adaptive governance. It also promotes interdisciplinary collaboration, enhances institutional transparency, and supports shared ownership of heritage values. In line with the 2011 UNESCO Recommendation on the HUL approach, the model contributes to the development of inclusive governance structures that bridge administrative, professional, and community boundaries.

Table 2.

Stakeholder-tailored considerations (elaborated by the authors).

Overall, this article confirms that approaching stakeholder engagement from a systems-thinking perspective transforms it into both an analytical and operational tool for coordinated heritage governance. The conceptual SD framework introduced here identifies leverage points, informs policy actions, and supports the long-term implementation of the HUL approach in Türkiye. Although still conceptual, it establishes a solid foundation for future simulation-based analyses and stakeholder-driven scenario testing, enabling more evidence-based and collaborative decision-making in heritage-led urban development.

5. Conclusions

This article demonstrates that the successful implementation of the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach in Türkiye depends on the strength and structure of multi-stakeholder collaboration within a complex and adaptive heritage conservation system. While the HUL framework offers a comprehensive vision for integrating heritage conservation with sustainable urban development, its practical application is limited by fragmented stakeholder engagement, lack of institutional coordination, and insufficient awareness of systemic interdependencies.

The SD tool used in this article has demonstrated its applicability as an analytical and conceptual instrument for systematically representing and illustrating stakeholder interactions. The SD model was developed through a two-step process involving problem articulation and system conceptualization. The first step compiled stakeholder groups and subgroups, mapped their objectives, and outlined their direct interactions. The second step translated these interactions into a causal loop diagram, which revealed indirect connections and feedback loops. This systemic view shows how decisions in one area cascade through the network, affecting the goals and performance of others.

The results confirm that stakeholder interactions are interconnected and mutually reinforcing, forming a web of dependencies that collectively influence the success of HUL implementation. When aligned strategically, these dynamics can turn fragmentation into synergy, fostering more responsive and participatory governance structures. Conversely, weak communication channels and uncoordinated decision-making can sustain inefficiencies and hinder the adaptive capacity of heritage management systems.

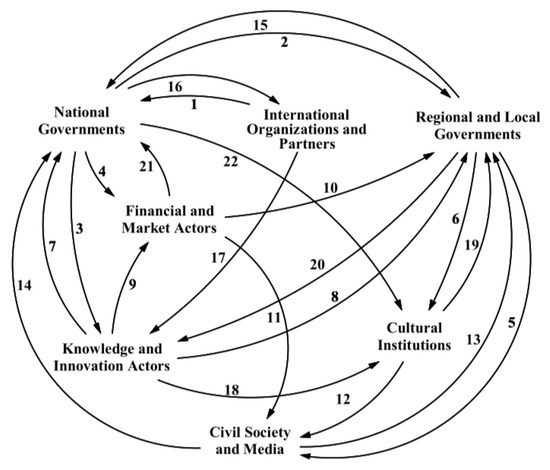

In conclusion, this article offers tailored considerations for each stakeholder group and presents a comprehensive stakeholder engagement framework that highlights the essential interactions for effective HUL implementation. This integrated framework illustrates the structure of stakeholder connections (Figure 8, Table 3).The proposed interactions between the stakeholders have been given in the sequence to be followed from the first decision-making process to the last one, both in the framework (Figure 8) and in the table (Table 2). To reduce complexity and improve clarity, stakeholders in this framework have been grouped: international organizations and partners, as well as national governments, were clustered as before; regional and local governments are represented together; knowledge and innovation actors include universities, research institutes, professional associations, and technology companies; financial and market actors encompass banks, developers, investors, and tourism stakeholders; cultural institutions include museums and cultural organizations; and civil society and media comprise NGOs, local communities, and the media.

Figure 8.

Stakeholder interconnections framework (elaborated by the authors). Black arrows indicate direction of interaction flow between stakeholders; Numbers (1–22) indicate the sequence of interaction pathways and should be followed in numerical order.

Table 3.

Stakeholder interconnections (elaborated by the authors).

The integrative framework developed in this article captures existing stakeholder interactions while illustrating potential alternative ways in which these interactions may evolve, without implying an ideal or balanced configuration. Rather than prescribing how stakeholders should interact, the framework operates as an analytical tool that visualizes the diversity of relational patterns that may emerge in practice, including asymmetric or unbalanced arrangements shaped by contextual and community-specific priorities. By mapping these potential configurations, the SD model provides a transparent foundation that can later support quantitative simulations aimed at examining the sensitivity, resilience, or vulnerability of stakeholder relationships under different scenarios without suggesting that any configuration represents a normative ideal.

The main innovation of this article lies in combining the stakeholder engagement perspective with the SD modeling approach. The methodology offers a reproducible model for analyzing, evaluating, and representing the complexity of multi-stakeholder governance systems in heritage conservation and preservation. Ultimately, this article offers both a conceptual and methodological foundation for moving from descriptive understanding to operational analysis of stakeholder interactions within the HUL approach. Applying systems thinking to heritage governance demonstrates how effective collaboration, communication, and shared responsibility can transform heritage conservation into an adaptive, inclusive, and sustainable process that enhances the resilience and identity of Türkiye’s historic urban landscapes.

However, this article has some limitations. The selection of variables and interconnections was based on a literature review and conceptual modeling, which could have introduced selection bias. Additionally, this article focused on problem articulation and system conceptualization without the quantitative stock–flow formulation, and simulation testing. While these steps were necessary to simplify system complexity, the resulting causal model remains conceptual and qualitative. Furthermore, although stakeholder considerations are theoretically aligned with institutional and operational capacities, their practical implementation may face challenges such as regulatory inertia, resource limitations, or institutional misalignment. Future expert validation and pilot programs would help strengthen their empirical reliability.

Future research should operationalize this conceptual model through simulation-based formulation and testing to measure the dynamic behavior of the HUL system under different policy, financial, or participatory scenarios. Further studies might extend the SD model to compare international contexts and evaluate whether the stakeholder framework can be transferred to other countries adopting the HUL approach. Additionally, participatory modeling workshops involving public authorities, professionals, and communities could enhance empirical grounding and foster co-production of knowledge among researchers and decision-makers. Overall, this article provides a conceptual and methodological foundation for integrating SD into heritage governance research. By framing stakeholder engagement as a dynamic framework rather than a static hierarchy, it offers an evidence-based roadmap toward adaptive, inclusive, and sustainable implementation of the HUL in Türkiye.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T.K. and F.E.K.; methodology, F.E.K.; software, F.E.K.; data curation, A.T.K. and F.E.K.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T.K. and F.E.K.; writing—review and editing, A.T.K. and F.E.K.; visualization, A.T.K. and F.E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019. Available online: https://population.un.org/wup/assets/WUP2018-Report.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).