Abstract

Dyes are widely used in textile processing and are frequently discharged without adequate treatment, posing risks to aquatic ecosystems through reduced water quality, toxicity to organisms, and long-term environmental degradation. To address the need for sustainable remediation solutions, this study investigated the use of pine bark (Pinus pinaster), an abundant forestry byproduct, as a low-cost biosorbent for textile dye removal. Powdered (<0.5 mm) and granular (>1 mm) bark fractions were washed, dried, and modified through iron impregnation (10 wt.% Fe) via sonication in an FeCl3·6H2O solution, with one iron-coated variant subsequently subjected to thermal treatment at 400 °C under nitrogen (1 h) and hydrogen (3 h). Adsorption performance was evaluated using synthetic effluents containing Sirius Blue, Astrazon Red, and Sirius Yellow, individually and as a ternary mixture (80 mg/L each), with added NaCl and NaHCO3 to simulate realistic conditions. Thermally treated granular iron-coated bark showed the highest removal efficiency, achieving >90% dye elimination within 24 h without detectable iron leaching, along with strong iron retention (~80%) and a 53% thermal-treatment yield. Maximum adsorption reached 15.51 mg/g at 5.0 g/L, while lower adsorbent doses increased capacity (26.8 mg/g) but reduced overall removal (~83%). Kinetic analysis was dose-dependent: the pseudo-first-order model provided the best fit at 5.0 g/L, reflecting the rapid approach to equilibrium, whereas the Elovich model fitted best at 2.5 g/L (R > 0.99), consistent with heterogeneous surface interactions under limited adsorbent availability. These results demonstrate the potential of thermally treated iron-coated pine bark as an efficient and sustainable biosorbent for textile wastewater treatment.

1. Introduction

The textile industry is one of the largest global sectors, with an anticipated business turnover of USD 2.25 trillion by 2025 [1]. It also plays a crucial role in the Portuguese economy, contributing 10% of total exports and employing over 199,000 people across 6301 companies as of 2023 [2,3]. Textile manufacturing consumes large amounts of water and chemicals, including dyes, salts, metals (chromium, arsenic, zinc), stabilizers, and detergents [4,5] with dyeing and rinsing processes alone generating approximately 113 to 151 m3 of wastewater per ton of textile product [6]. Textile wastewater discharges cause dye accumulation in water bodies, reducing light penetration and harming aquatic ecosystems, while pollutant leaching contaminates groundwater, and their degradation products pose toxicity risks [6]. These pollutants contribute to eutrophication, oxygen depletion, inhibited reoxygenation, and metal ion sequestration, increasing genotoxicity risks [7].

Textile wastewater often exhibits significant variability in parameters such as total organic carbon (TOC), chemical oxygen demand (COD), biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), pH, electrical conductivity, turbidity, and color, due to differences in industrial processes, complicating treatment efforts [8]. Another important aspect is the occurrence of high COD/BOD5 ratios (>3.5), which implies that conventional biological treatments may be ineffective, with color removal rates below 40% [8], and often requiring physico-chemical methods to achieve disposal quality [9]. Furthermore, due to their high solubility in aqueous solutions, many dyes are only partially removed through conventional physico-chemical treatments such as coagulation, sedimentation, and filtration [10]. Several factors, including seasonal variations, complex composition, dye non-biodegradability, and the extensive range of dye types, complicate cost-effective and environmentally sustainable dye removal from textile effluents [11]. Notably, global dye consumption has increased by over 400% in the last two decades, rising from 178,000 tons in 2004 to 1,000,000 tons in 2021 [5,12], of which 2–20% are directly discharged into water resources [13]. Given increasingly stringent discharge regulations and the rising demand for wastewater reuse, developing high-performance treatment solutions is essential [11].

Adsorption is widely recognized as one of the most effective techniques for dye removal from textile wastewater, being often an exothermic process influenced by several factors, including temperature, adsorbate properties (polarity, molecular size, solubility, acidity/basicity), adsorbent characteristics (surface area, pore size distribution, surface functional groups, hydrophobicity, and density), and contaminant concentration [14,15]. An ideal adsorbent should exhibit high removal efficiency within a short time, be cost-effective, reusable, and scalable, and require minimal chemical processing for its production, ensuring environmental sustainability [15].

Carbon-based materials, particularly activated carbon, are widely used as industrial adsorbents due to their high porosity and large surface area, which enhance adsorption capacity. However, their production involves energy-intensive activation processes, increasing costs significantly [7,15]. The transformation of natural materials, especially waste from other industries, into biochar has been analyzed as a sustainable and lower-cost alternative for the production of adsorbents for color removal [16], for example rice husks [17], pecan shells [18], cellulose and paper sludge [19], and lignocellulosic materials [20] have been explored as sustainable alternatives. Iron-based adsorbents have also gained attention due to their high efficiency in contaminant capture, non-toxicity, abundance, and low cost. Iron incorporation increases the number of adsorption sites and shifts the isoelectric point to higher values, promoting electrostatic interactions with anionic dyes [21]. Additionally, thermal treatment of adsorbents can significantly improve their porosity and surface area. This process typically occurs under oxygen-limited conditions and at high temperatures, leading to the release of volatile matter and the formation of porous structures [22]. The use of nitrogen and hydrogen gases during thermal treatment is particularly beneficial for iron-coated adsorbents, facilitating the anion removal of the precursor (e.g., chloride) and metal reduction, thereby improving metal fixation on the adsorbent surface [23].

Pine (Pinus pinaster) is one of the most abundant tree species in Portugal, covering approximately 22% of the national forest area [24]. While its economic value is primarily derived from timber and resin production [25], pine bark is a significant byproduct of the forestry industry and a common forest residue. This material is readily available at low cost, making it a promising resource for sustainable biosorbent production, thereby reducing wastewater treatment expenses [26,27]. Pine bark has a diverse chemical composition: approximately 45% lignin, 25% cellulose, and 15% hemicellulose [28]. Additionally, it is widely available across multiple regions, including Spain, southern France, western Italy, parts of the Middle East, and North Africa, ensuring global accessibility for adsorption applications [29]. In contrast to conventional activated carbons, which, although often derived from biological sources, undergo extensive carbonization and activation, biosorbents produced directly from lignocellulosic residues maintain much of the natural structure and chemistry of the raw material. This distinction is essential, as biosorbents rely on native functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carboxyl, and phenolic groups) for adsorption, while activated carbons depend on their highly porous carbonized structure. In this work, the pine bark used as the starting matrix was obtained in its virgin form directly from the forest floor, without any prior industrial processing. This ensured that the adsorbent originated from an untreated natural residue, aligning with the objectives of developing low-cost, minimally processed, and sustainable biosorbents.

The main goal of this study was to assess the potential of pine-bark–derived adsorbents—both iron-coated and thermally treated—in the removal of textile dyes under conditions representative of real wastewater. Initially, the dye removal capacity of pine bark-derived adsorbents was evaluated using a synthetic effluent containing Sirius Blue K-CFN dye composed of Direct Blue 85 [30]. Direct dyes are highly water-soluble and form strong bonds with textile fibers, with their primary advantage being their low cost, which makes them widely used in the textile industry [5,15]. Global consumption of direct dyes increased dramatically from 54 thousand tons in 1992 to 458 thousand tons in 2024 [31], with the market value rising from USD 317.3 million to a projected USD 414.7 million by 2030 [32], highlighting the growing environmental relevance of these dyes. Other commonly used dyes include the cationic dye Astrazon Red FBL [33] and the anionic dye Sirius Yellow K-CF, which, along with Sirius Blue K-CFN, represent primary colors in textile dyeing processes. This study examined the removal of all these dyes to evaluate the potential of pine bark as a sustainable, cost-effective alternative for textile dye adsorption.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Pine bark (Pinus pinaster) was obtained from local forestry residues sourced in northern Portugal. Iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O, ≥98%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Nitric acid (HNO3, 68%) and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%) used for acid digestion were supplied by Fisher Scientific (Loughborough, UK). High-purity nitrogen (N2, 99.999%) and hydrogen (H2, 99.999%) gases used for thermal treatment were supplied by Air Liquide (Lisbon, Portugal). Dyes used to prepare synthetic textile effluents were obtained from DyeStar: Sirius Blue K-CFN, Sirius Yellow K-CF, and Astrazon Red FBL 200%. Sodium chloride (NaCl, ≥99.5%) and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, ≥99.7%) were purchased from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Distilled water was used for all preparation, washing, and dilution steps.

2.2. Preparation of Pine Bark-Derived Adsorbents

2.2.1. Raw Material Selection and Pre-Treatment

Pine bark (Pinus pinaster) adsorbents were produced from two different particle size fractions: powdered bark (<0.5 mm) and granular bark (>1.0 mm). Both raw materials were submitted to a magnetic stirrer assisted extraction (MSAE) process using distilled water as the solvent to remove impurities. The extractions were carried out at 60 °C with a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 (g/mL) for 60 min and the resulting suspensions were cooled and filtered using a 1.5 µm glass fiber filter and a vacuum pump (Welch MPC 090 E, New York, NY, USA). Finally, the washed pine bark was dried at 60 °C in an oven before further processing.

2.2.2. Iron Impregnation Process

The impregnation of iron was processed using the Incipient Wetness Impregnation (IWI) process based on previous works [34]. Briefly, the required water volume to fully wet the washed pine bark was determined as 7.4 mL per gram of solid. This was established by gradually adding water to a 1 g sample of washed pine bark until saturation without excess liquid. After that, the required mass of iron(III) chloride hexahydrate (FeCl3·6H2O) was calculated to achieve a final iron content of 10% (wt.%). The FeCl3·6H2O was dissolved, added dropwise to the material, and subjected to sonication (Elmasonic S120H, Singen, Germany) for 90 min.

2.2.3. Thermal Treatment

Iron-coated pine bark was submitted to a thermal treatment in a furnace (Termolab, Águeda, Portugal) at 400 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min and during 4 h (after reaching the desired temperature), with nitrogen flow in the first hour and hydrogen flow in the remaining 3 h. Nitrogen flow in the first hour is necessary to prevent oxidative degradation of the organic matrix during heating and to ensure that the material reaches the target temperature under inert conditions. The subsequent hydrogen atmosphere promotes partial reduction of iron species, enhancing their stability and affinity for dye molecules by facilitating the formation of mixed-valence Fe(II)/Fe(III) surface sites. This two-step gas protocol improves the structural integrity of the biosorbent and contributes to the enhanced adsorption performance observed for the thermally treated materials.

Following the processing steps, four distinct adsorbents were obtained:

- Pine bark powder impregnated with 10% iron (PFe)

- Granular pine bark coated impregnated 10% iron (GFe)

- Pine bark powder impregnated with 10% iron and thermally treated (PFeTT)

- Granular pine bark impregnated with 10% iron and thermally treated (GFeTT)

2.3. Characterization of the Adsorbents

2.3.1. Iron Content Determination

The iron content in the prepared adsorbents was quantified via acid digestion, adapted from [35]. 150 mg of each adsorbent were placed, in duplicates, in digestion tubes with 5 mL of distilled water, 4 mL of nitric acid (HNO3 68%), and 12 mL of hydrochloric acid (HCl 37%). A blank sample without adsorbent was prepared following the same procedure. The digestion was conducted at 150 °C for 120 min and the resulting solutions were filtered using a 1.5 µm glass fiber filter and a vacuum pump. After filtration, the solutions were diluted to 50 mL with distilled water, and the iron concentration was measured using atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) (932 AA, GBC Scientific Equipment Ltd., Perai, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia).

2.3.2. Iron Leaching Assessment

Part of the adsorbents were also subjected to a washing procedure with distilled water, consisting of three short cycles in a rotating shaker (SB3, Stuart, Surrey, UK). Each cycle used a solid-to-liquid ratio of 5 g/L and lasted 30 min at 20 rpm, ensuring full contact between the adsorbent and the washing solution. The supernatant of each cycle was discarded to replicate potential iron release during handling or initial rinsing. They were then dried overnight in an oven at 60 ± 1 °C before undergoing acidic digestion, as described in Section 2.3.1, and their iron content was quantified using AAS.

2.3.3. Surface Characterization

The textural characterization of all materials was performed to assess potential changes after the surface modifications. N2 adsorption isotherms were measured at −196 °C using a Quanthachrome NOVA 4200e (Spectralab Scientific Inc., Markham, ON, Canada), with samples outgassed at 120 °C for 5 h under vacuum. The specific surface area (SBET) was calculated using the BET method, while pore diameter was calculated using the DFT method [34]. Moreover, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyzed iron distribution on samples from different processing stages, including washed granular bark, iron-coated and thermally treated adsorbents, and a post-treatment sample. Briefly, the SEM/EDS analysis was conducted using a high-resolution (Schottky) Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope equipped with X-Ray Microanalysis and Electron Backscattered Diffraction: FEI Quanta 400 FEG ESEM/EDAX Genesis X4M (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, EUA). Pine bark samples without iron were coated with a thin Au/Pd film via sputtering, using the SPI Module Sputter Coater (SPI supplies, West Chester, PA, USA). Each image includes a databar displaying key analysis conditions.

2.3.4. Point of Zero Charge (pHpzc)

The point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the adsorbent was found in order to determine at which pH the surface of the adsorbent has a net zero charge, i.e., when the negative and positive charges of the surface are equal. pH variation method was utilized using inert NaOH solution (0.1 mol L−1), preadjusted at varying initial pH (4, 6, 8, 10, and 12). For each measurement, 20 mL of the solution and 20 mg of the adsorbent were transferred to 50 mL flasks and mixed at 20 rpm for 24 h. After reaching equilibrium, final pH (pH meter, Consort C6010, Consort, Turnhout, Belgium) of each solution was measured and pHpzc was found from final pH vs. initial pH plot corresponding at the point where pH did not vary. Below pHpzc, the surface of the adsorbent has positive charge and above it negative charge.

2.4. Evaluation of Dye Removal Efficiency

2.4.1. Preparation of Synthetic Effluents

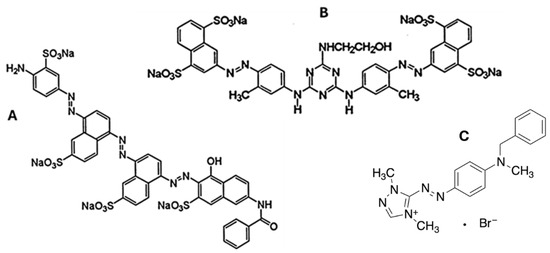

Dye removal efficiency was assessed using three synthetic textile effluents prepared with dyes covering primary colors: Sirius Blue K-CFN (80 mg/L, DyeStar, C43H26N8Na4O14S4, 1098.93 g/mol, Singapore) for blue effluent, Astrazon Red FBL 200% (80 mg/L, DyeStar, C18H21N6·Br, 401.3 g/mol) for red effluent, and Sirius Yellow K-CF (80 mg/L, DyeStar, C39H30N10Na4O13S4, 1066.94 g/mol) for yellow effluent (Figure 1) (DyStar Anilinas Teíxteis Unipessoal, Lda, Porto, Portugal) [36,37,38]. Additionally, a mixed effluent (1:1:1 ratio of the three dyes) was prepared to better represent real textile wastewater. To simulate real effluent salinity conditions, sodium chloride (NaCl, 2.5 g/L) and sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3, 1.0 g/L) were added, and the pH, turbidity, and conductivity of synthetic effluents were further adjusted based on literature values for real textile wastewater [39].

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of the dyes used in this work with (A) being the structure of Sirius Blue K-CFN (80 mg/L, DyeStar, C43H26N8Na4O14S4, 1098.93 g/mol) for blue effluent, (B) being Sirius Yellow K-CF (80 mg/L, DyeStar, C39H30N10Na4O13S4, 1066.94 g/mol), and (C) Astrazon Red FBL 200% (80 mg/L, DyeStar, C18H21N6●Br, 401.3 g/mol) for red effluent.

2.4.2. Batch Adsorption Experiments

Adsorption experiments were conducted in a thermostatic chamber at 20 °C with rotary agitation at 20 rpm for 24 h. For each experiment, 30 mL of synthetic effluent and an adsorbent concentration of 5 g/L were used (in duplicate). After the treatment, the solutions were filtered using a 1.5 µm glass fiber filter. Absorbance was measured with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU UV-1280, Shimadzu corporation, Kyoto, Japan) at the peak absorption wavelength for each dye, determined by prior scanning across the visible spectrum at the peak absorption wavelengths for each dye: 564 nm (blue), 510 nm (red), 380 nm (yellow), and 415, 535, and 606 nm for the dye mixture. The amount of dye removed by adsorption was calculated using the following equation:

where q is the color removal initial concentration of dye per gram of pine bark adsorbent, Cinitial is the initial concentration of the dye in grams per liter, Cafter treatment is the dye concentration in the treated solution in grams per liter, m is the mass in g of pine bark adsorbent and Vdye is the volume of dye solution in liters.

2.4.3. Kinetic Studies

Kinetic adsorption curves were constructed for the most promising adsorbents: granular pine bark with 10% iron and thermally treated (GFeTT) at two different operational concentrations, 2.5 g/L and 5 g/L. For the 5.0 g/L adsorption test, samples were collected at 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, and 240 min while for the 2.5 g/L test, sampling times were 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 240, 360, and 1440 min. The concentration of the dye was determined by UV-Vis spectrophotometry and the kinetic models used to describe the adsorption removal kinetics were the pseudo-first-order (Equation (2)), pseudo-second-order (Equation (3)), and Elovich (Equation (4)) models [40,41].

where q (mg/g) represents the amount of dye adsorbed, qe; (mg/g) corresponds to the amount of dye adsorbed at equilibrium, k1 (min−1) and k2 (g/(mg.min)) are the kinetic constants for the pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order models, respectively, the constant a (Equation (4)) (mg/(g·h)) is the initial adsorption rate, b (g/mg) is the reciprocal of surface coverage when the adsorption rate is 1/e (exponential decay) of its initial value, and t (min) represents the treatment duration. To better understand the relationship between color removal efficiency (%CR) and adsorption capacity, the adsorbent concentration was adjusted between 1 and 10 g/L, for 24 h treatment periods.

3. Results

3.1. Adsorption Experiments

3.1.1. Preliminary Adsorption Tests

To identify the most effective adsorbents for color removal, preliminary adsorption tests were conducted using the synthetic blue effluent and the color removal efficiency (%CR) was determined by comparing the absorbance of the treated and initial effluent. The mean results and standard deviations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Average color removal efficiency (%CR) (n = 2) recorded after 24 h treatment of synthetic blue effluents with the different adsorbents.

As observed above, in general, the iron-coated adsorbents demonstrated high color removal efficiency after 24 h, suggesting that iron impregnation enhances adsorption capacity. This aligns with findings described in the literature, which reported improved dye adsorption capacity in iron oxide-impregnated adsorbents [19]. In fact, studies imply that iron incorporation generates specific adsorption sites and shifts the isoelectric point, facilitating electrostatic interactions between the adsorbent surface and anionic dyes [11,21,42].

Additionally, it is relevant to note that GFe adsorbents exhibited a 10% higher color removal efficiency when compared with PFe adsorbents. While smaller particles typically have a larger surface area (Table 2), the superior performance of the granular adsorbent may be attributed to its higher total pore volume, as described by Tsai et al. [43]. Indeed, an analysis of the pore properties of different adsorbents prepared in this study revealed a total pore volume for the GFe adsorbent approximately 3.5 times higher than that recorded for the PFe adsorbent, supporting the proposed explanation. The higher pore volume provides additional adsorption sites, with GFe achieving 97.7 ± 0.2% color removal when compared to 88 ± 3% obtained by PFe. Nevertheless, it was observed that significant iron leaching into the treated solution caused a yellowish discoloration, suggesting the high fragility of the iron coating. This behavior was confirmed when a drastic reduction in adsorption efficiency was observed following a washing process, with Washed Powder + 10%Fe and the Washed Granular + 10%Fe showing a color removal of 20 ± 5% and 62 ± 5%, respectively.

Table 2.

Pore properties of the prepared adsorbents.

Ultimately, the thermal treatment of 4 h at 400 °C significantly enhanced adsorption efficiency, as both thermally treated adsorbents (powdered and granular) achieved near-complete color removal after 24 h. Furthermore, GFeTT exhibited the largest surface area (53 m2/g) and total pore volume (0.043 cm3/g), approximately 6.4 times higher than that recorded before the adsorbent was subjected to thermal treatment. This is a result of the thermal treatment process, which promotes pore formation and increases surface area, improving adsorption performance [22]. Moreover, the lower standard deviation values that were observed for thermally treated adsorbents indicate a greater precision across replicates which can be attributed to the enhanced surface homogeneity resulting from thermal treatment, which reduces variability [20].

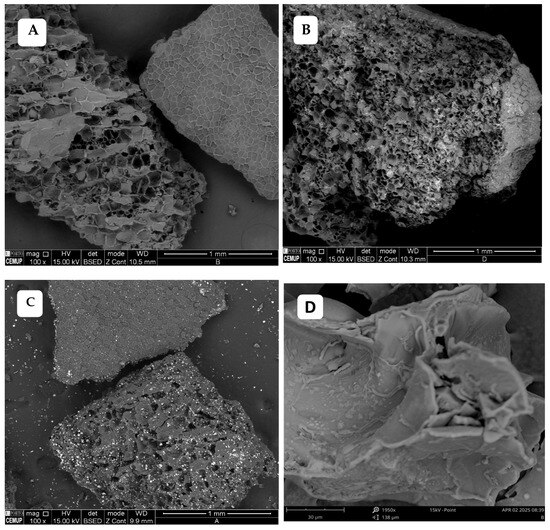

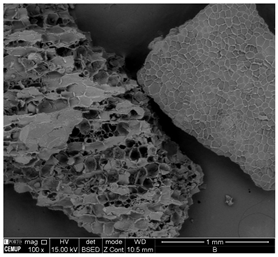

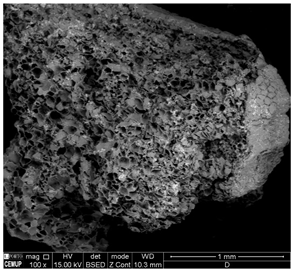

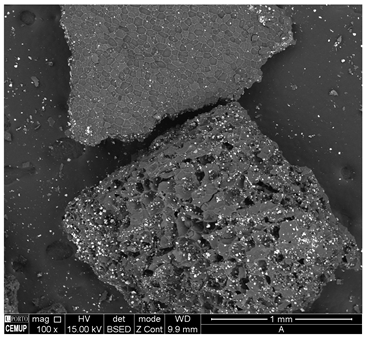

3.1.2. Surface Characterization

The morphology of the granular adsorbent was analyzed using SEM at the various stages of its processing. The results show a significant predominance of pores in the washed granular pine bark, without any additional processing (Figure 2A), confirming the viability of this raw material for biosorbent production. However, it is important to note that the observed porous structure primarily consists of the material’s biological cells, which play a key role in facilitating iron crystal fixation. Additionally, when comparing the SEM images of the iron-coated granular adsorbent before and after thermal treatment (Figure 2B,C, respectively), an increase in pore size and a greater definition of the iron crystals impregnated on the adsorbent surface can be observed, with a heterogeneous distribution. The biological structure of the material remained intact throughout the treatments, though heat treatment appeared to open some internal structures and slightly reduce the size of the cellular framework. This aligns with SEM analyses of pine bark adsorbents found in the literature and the findings from adsorption experiments [44].

Figure 2.

SEM micrographs the granular adsorbent: (A) washed granular pine bark; (B) Granular + 10%Fe; (C) Granular + 10%Fe thermally treated (1 mm scale) and (D) Powder + 10%Fe (PFe) (30 µm scale).

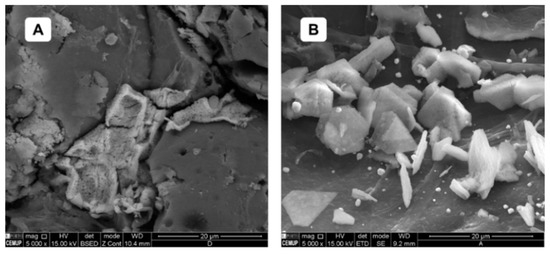

A more detailed analysis of the crystals detected in Figure 2C was carried out. Their magnified image can be found in Figure 3 below, and at this scale, their elemental composition was quantified using Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS), revealing that the larger crystals present on the surface of both adsorbents have a balanced composition of iron and chloride. However, in the thermally treated adsorbent (Figure 3B, smaller crystals stand out, with a composition predominantly consisting of iron (approximately 73% Fe and 5% Cl), Table A5 in the Appendix A.3. These results support the earlier hypothesis, suggesting that thermal treatment facilitates the release of the anionic precursor and consequently enhances iron fixation on the adsorbent surface [45].

Figure 3.

SEM micrographs of the granular adsorbent coated with iron, before (A) and after (B) heat treatment (20 µm scale).

Moreover, the point of zero charge (pHpzc) of the most effective biosorbent, GFeTT, was also measured and it was established to be 8.24 which signifies that the adsorbent surface exhibits a positive charge at pH values below 8.24 such as the one used during this work (pH = 8). This behavior holds significant implications for the adsorption of textile dyes, particularly anionic dyes such as Sirius Blue K-CFN or Sirius Yellow K-CF, which are preferentially adsorbed under conditions in which the adsorbent surface is positively charged, thereby enhancing electrostatic attraction. The observed pHpzc is in line with values typically found for iron-modified lignocellulosic biosorbents, which are known to show alkaline zero-charge points due to increased basic surface-oxide and hydroxy-lated iron functionalities [46,47].

3.1.3. Iron Content Quantification

To assess coating efficiency, the iron content in the adsorbents before and after washing was quantified via acid digestion and the results are expressed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Average losses (n = 3) of the iron coating evidenced by the different adsorbents, after washing with distilled water.

The highest iron concentration was recorded for the thermally treated adsorbents. This could be attributed to the thermal treatment process, which degrades volatile compounds, reducing the total mass and thereby increasing the iron content per gram of material [22,23].

Regarding the mechanical resistance of the coating, the results suggest that thermally treated adsorbents retained the highest iron content after washing, with a retention of iron of around 70%. During thermal treatment, nitrogen and hydrogen gases were supplied, promoting the release of the anionic precursor (chloride) and the reduction of iron. This effect, combined with increased material porosity due to the high-temperature exposure, enhances iron fixation on the material’s surface and makes the coating more resistant to mechanical action [22,23]. Conversely, non-thermally treated adsorbents lost over 70% of their impregnated iron after washing, demonstrating that the IWI method used for coating may be less effective than other techniques for iron fixation [48], leading to weaker attachment. During effluent treatment, agitation likely contributed to iron detachment, resulting in elevated iron concentrations in the treated solution. However, compared to other impregnation techniques, this method offers the advantage of minimizing waste and wastewater generation to nearly zero.

3.2. Color Removal Efficiency

The thermally treated adsorbents, identified as the most promising in preliminary tests, were evaluated for color removal from synthetic effluents containing blue, red, and yellow dyes, as well as a 1:1:1 dye mixture representing real textile wastewater. The %CR values are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Average color removal percentages (%CR) (n = 2) for the three dyes analyzed and their mixture, recorded after 24 h treatments.

As the results suggest, the granular adsorbents consistently outperformed powdered adsorbents, which aligns with prior findings and is likely due to their higher total pore volume [43]. It can be observed that the blue effluent exhibited the highest removal efficiency (>98%), while yellow effluent showed the lowest, with granular adsorbents achieving 92% removal and powdered adsorbents only 55 ± 9%. Although no previous studies have examined pine bark-based biosorbents for this specific dye, similar research on metal-loaded polymer matrices reported comparable efficiencies [49]. Specifically, the treatment of a synthetic effluent containing Sirius Yellow K-CF (80 mg/L) was evaluated by Moghaddam et al., [50] and Pandey et al. [44], using chitosan-polyacrylamide matrices loaded with zinc oxide (ZnO) and titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles, reporting removal efficiencies of 62% and 70%, respectively. These results are comparable to those obtained for the powdered adsorbent, whereas the granular adsorbent achieved considerably higher treatment efficiencies. Moreover, it is worth noting that the costs associated with the biosorbents analyzed in this project are significantly lower than those of the mentioned polymeric matrices [50].

Furthermore, regarding the fact that adsorption was less efficient for the yellow effluent, compared to the others, published studies reported a similar effect in tests carried out with chitosan matrices, which recorded maximum adsorption capacities for blue (498.0 mg/g) and red (312.8 mg/g) dyes much higher [49] than those reported for the yellow dye (149.8 mg/g) [50].

Finally, tests carried out with the mixture of dyes revealed that the removal was lower when analyzed at a wavelength (415 nm) closer to that characteristic of the yellow dye and increased as the wavelength of the blue dye approached. This confirms that the adsorbents exhibit a lower removal capacity for the yellow dye, although very high in the case of the granular adsorbent (between 97% and 99%).

It is also important to mention that an ASS analysis of the treated solutions revealed that no iron was released, confirming the increase in the resistance of the adsorbent coating after heat treatment [22,23].

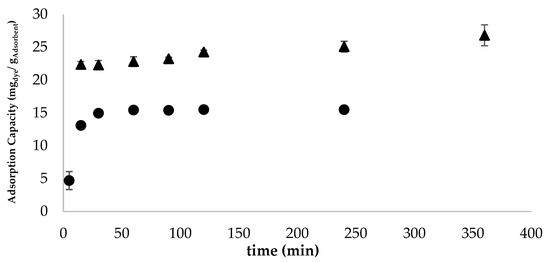

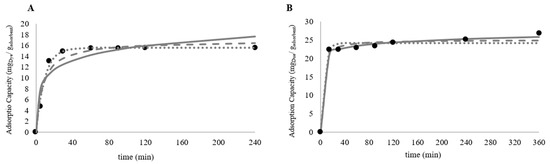

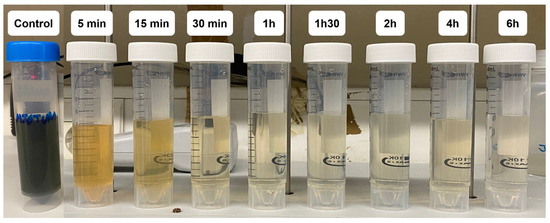

3.3. Adsorption Kinetics

In this study, kinetic adsorption curves were obtained for the most promising adsorbent (Figure 4)-granular pine bark containing 10% iron and thermally treated (GFeTT) at two operational dosages (2.5 g/L and 5.0 g/L).

Figure 4.

Graphical representation of the color removal kinetics obtained for the thermally treated Granular + 10%Fe (GFeTT) adsorbent at a concentration of 5.0 g/L and a dye concentration of 80 mg/L (●) and at a concentration of 2.5 g/L and a dye concentration of 80 mg/L (▲).

Based on the dye concentration profiles measured by UV-Vis spectrophotometry at the corresponding sampling times, the adsorption kinetics were evaluated using three widely employed kinetic models: the pseudo-first-order (Equation (2)), pseudo-second-order (Equation (3)), and Elovich (Equation (4)) models. Although all three models are frequently used for liquid-phase adsorption, they differ substantially in their underlying assumptions and mechanistic implications. The pseudo-first-order model assumes that the adsorption rate is proportional to the number of unoccupied sites and is typically associated with diffusion-controlled physisorption processes on relatively homogeneous surfaces. The pseudo-second-order model, on the other hand, is based on the assumption that chemisorption is rate-limiting, involving electron exchange or sharing between the dye molecules and specific functional groups on the adsorbent surface. In contrast, the Elovich model is particularly suited for systems in which adsorption occurs on heterogeneous or energetically non-uniform surfaces, where the activation energy decreases as adsorption progresses. Given the physicochemical features of the GFeTT material especially the surface heterogeneity introduced by thermal treatment and the non-uniform distribution of iron this model is theoretically consistent with the expected adsorption behavior [51,52].

To determine the dye concentration after each treatment time, it was necessary to construct a calibration curve, shown in Table A2 of the Appendix A.2. The scan of the visible spectrum using the mixture of dyes with three different colors revealed several absorption peaks. Therefore, to promote greater accuracy of the results, the area of the curve below the spectrum (380 to 700 nm) for each sample was considered.

At 5.0 g/L adsorbent concentration, 80% dye removal was achieved within 15 min, with near-complete removal (97%) within 2 h (Figure 4) and as observed visually in Figure A1 (Appendix A.4). From this moment on, it was possible to observe a stabilization in the adsorption capacity, showing a maximum value of 15.51 ± 0.01 mg of dye per gram of adsorbent at equilibrium (Table A6). This behavior is corroborated by kinetic curves reported in the literature for adsorbents produced from pine bark, which show stabilization of adsorption capacity after 300 min of treatment for adsorbent concentrations of 1 g/L [53].Reducing the adsorbent concentration to 2.5 g/L (Figure 4), the maximum color removal was approximately 83% and occurred after 6 h of treatment. From this point onwards, it is possible that the equilibrium was achieved, and part of the adsorbed dye started to be released, due to the saturation of the adsorbent, which is in a reduced concentration compared to the amount of dye needed to be removed. This was suggested by the reduction in adsorption capacity manifested between 6 and 24 h of treatment. The maximum adsorption capacity exhibited by the adsorbent at a concentration of 2.5 g/L was considerably higher than that observed at a concentration of 5.0 g/L, reaching 26.8 ± 0.4 mg of dye per gram of adsorbent (Table A7, Appendix A.4). One justification for what happened is the fact that, at a lower adsorbent concentration, the availability of adsorbent particles for dye removal is lower. This leads to a greater portion of the active sites of these particles being used in the treatment, leading to the saturation of the adsorbent and, consequently, the maximization of its adsorption capacity—as described by Zermane et al. [53].

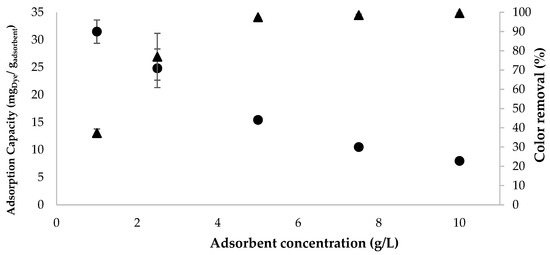

Naturally, reducing the adsorbent concentration leads to a decrease in dye removal efficiency over a given treatment period, even though the adsorption capacity increases. It was observed that at the lowest concentration analyzed (1.0 g/L), the GFeTT adsorbent exhibited an adsorption capacity of 31 ± 2 mg/g (Figure 5) but removed only 37 ± 2% of the dye present in the effluent after 24 h of treatment. With an increase in concentration to 10 g/L, the removal efficiency reached 99.6 ± 0.1%, while the adsorption capacity decreased by more than threefold, stabilizing at 7.97 ± 0.03 mg/g.

Figure 5.

Graphical representation of adsorption capacity (●) and color removal efficiency (▲) obtained for the thermally treated Granular + 10% Fe (GFeTT) adsorbent at a concentration of 1.0, 2.5, 5.0, 7.5 and 10 g/L and a dye concentration of 80 mg/L, after 24 h treatment.

Thus, there is a minimum threshold for the operational adsorbent concentration to ensure that its saturation does not compromise treatment efficiency (Table A9, Appendix A.5). For concentrations below 5 g/L, complete dye removal from the solution was not achieved. In contrast, above this concentration, the removal efficiency remained very high, with only minor variations as the concentration increased. Additionally, the GFeTT adsorbent exhibits a moderate removal capacity at 5 g/L (15.44 ± 0.03 mg/g), representing a good balance between removal efficiency and adsorption capacity.

In general, the maximum adsorption capacity recorded for the prepared adsorbent is comparable with that of other biosorbents produced from plant residues reported in the literature, namely orange peel at a concentration of 8.0 g/L (10.7 mg/g) [54], sugar cane bagasse at a concentration of 5.0 g/L (23.6 mg/g) [55] and peanut husk at a concentration of 2.0 g/L (25.9 mg/g) [56]. One of the main advantages of using pine bark as a precursor for biosorbents is its high content of condensed tannins, which is obtained in the form of an extract in the raw material washing process [21]. In fact, several studies in the literature demonstrate the use of tannins extracted from pine bark in the production of adsorbents with a high affinity for precious metals and coagulants. Therefore, they constitute an important value-added byproduct of the processing described in this project for pine bark [57,58].

Using the CurveExpert Professional 2.7 software, the kinetic data for color removal at both adsorbent concentrations (2.5 and 5.0 g/L) were fitted to the original (non-linear) forms of the pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, and Elovich models, presented in Equations (2)–(4) in Section 2.3.3 [40]. The results are presented in Figure 6 and the fitting parameters obtained for each kinetic model, as well as the corresponding correlation coefficients, are provided in the Table A8.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of the fitting of the collected experimental data (●) to the Pseudo-First Order (⋯), Pseudo-Second Order (– –) and Elovich (―) kinetic models for the thermally treated Granular + 10% Fe (GFeTT) adsorbent at a concentration of 5.0 g/L (A) and 2.5 g/L (B) and a dye concentration of 80 mg/L.

The kinetic data obtained for both adsorbent concentrations were adequately fitted by the three evaluated models (R > 0.94). For the system operating at an adsorbent concentration of 5.0 g/L, the pseudo-first order model yielded the best fit (R > 0.99). This behavior is consistent with the inherent ability of this kinetic model to describe adsorption processes that rapidly approach equilibrium [40]—a trend clearly observed for the GFeTT adsorbent, which displayed a fast initial adsorption rate followed by early system stabilization.

At the lower adsorbent concentration of 2.5 g/L, the best fit was obtained for the Elovich model (R > 0.99), although both the pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order models also produced good fits. The Elovich kinetic model is particularly suitable to describe adsorption processes involving solid materials to remove contaminants in wastewater [59], as well as for characterizing adsorption systems with heterogeneous surfaces [41]. Since the SEM analysis of the adsorbent surface (Figure 3C) revealed a heterogeneous distribution of impregnated iron—responsible for creating specific sites for dye complexation—the results obtained align with expectations. The slightly lower accuracy of the pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order models at 2.5 g/L may be attributed to the underlying assumption in both models that adsorption equilibrium is achieved [40,60]. In this case, equilibrium was not fully reached, which explains the less precise fit relative to the Elovich model.

Iron content in the treated solutions was monitored through multiple AAS (Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy) analyses. As a result, it was found that the thermal treatment of iron-coated adsorbents not only led to a significant increase in color removal capacity but also reduced iron release into the treated solution to levels below the maximum discharge limit of 2.0 mg/L established by Portuguese legislation [61]. To determine whether the energy investment in this treatment process is truly justified by the efficiency gains, conducting a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) would be valuable, allowing for the quantification of its environmental and economic impact [62]. Nevertheless, studies have been exploring the potential to harness the heat generated during this type of thermal treatment [63,64].

4. Conclusions

The widespread use of dyes in the textile industry often results in the discharge of toxic compounds in wastewater, posing severe risks to aquatic ecosystems. Developing sustainable and affordable treatment technologies is crucial, and pine bark-based adsorbents offer a promising solution due to their low cost, abundance, and natural origin, aligning with circular economy principles.

The adsorption assays demonstrated that iron coating enhanced dye removal, with thermal treatment significantly boosting the adsorbents’ performance. The GFeTT adsorbent achieved the highest color removal for synthetic blue (99.8 ± 0.1%), red (96.2 ± 0.2%), yellow (92 ± 2%), and mixed effluents (97.0 ± 0.1% to 99.0 ± 0.1%) after 24 h of treatment. It also showed the lowest iron loss during washing (20.5 ± 0.3%) and the highest thermal treatment yield (~53%).

The kinetic modeling highlighted that all three evaluated models (pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, and Elovich) provided good fits to the data (R > 0.94); however, the best-fitting model depended on the operational conditions. At 5.0 g/L, the pseudo-first-order model showed the highest accuracy, reflecting the rapid approach to equilibrium. At 2.5 g/L, the Elovich model provided the best fit, consistent with the heterogeneous distribution of iron observed in the SEM/EDS analysis and the non-uniform energy profile of the active sites. These results confirm that surface heterogeneity plays a key role in the adsorption mechanism of the GFeTT material.

Overall, thermally treated iron-coated pine bark demonstrated excellent adsorption performance, operational stability, and competitive capacity compared to other plant-derived biosorbents. These findings support its potential as an efficient and sustainable material for textile wastewater treatment, particularly in processes aiming to integrate low-cost, circular, and environmentally responsible technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.G. and R.M.F.; methodology, P.G., A.P., O.S.G.P.S. and R.M.F.; validation, A.P., O.S.G.P.S., M.F.R.P., C.M.S.B. and R.M.F.; formal analysis, P.G. and R.M.F.; investigation, P.G.; resources, M.F.R.P. and C.M.S.B.; data curation, P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.G.; writing—review and editing, P.G., A.P., O.S.G.P.S., M.F.R.P., C.M.S.B. and R.M.F.; visualization, P.G.; supervision, O.S.G.P.S., C.M.S.B. and R.M.F.; project administration, M.F.R.P. and C.M.S.B.; funding acquisition, M.F.R.P. and C.M.S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is a result of Agenda “GIATEX—Intelligent Water Management in the Textile & Clothing Industry”, nr. C644943052-00000050, investment project nr. 17, financed by the Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRR) and by European Union—NextGeneration EU. This research was also supported by: UID/50020 of LSRE-LCM—Laboratory of Separation and Reaction Processes—Laboratory of Catalysis and Materials—funded by Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P./MCTES through national funds; and ALiCE—LA/P/0045/2020 (DOI: 10.54499/LA/P/0045/2020).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to ongoing project activities and institutional data management policies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BOD | Biochemical oxygen demand |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| IWI | Incipient Wetness Impregnation |

| GFe | Granular pine bark coated impregnated 10% iron |

| GFeTT | Granular pine bark impregnated with 10% iron and thermally treated |

| PFeTT | Pine bark powder impregnated with 10% iron and thermally treated |

| PFe | Pine bark powder impregnated with 10% iron |

| pHpzc | Point of zero charge |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy |

| %CR | Color removal (%) |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Thermal Treatment Yield Determination

The thermal treatment yield was determined for each of the analyzed adsorbents with different granulometries (Table A1). This yield measured the percentage of the adsorbent’s initial mass that remained after the heating process involved in the thermal treatment.

Table A1.

Average yield (n = 3) of the heat treatment process to which the adsorbents under study were subjected.

Table A1.

Average yield (n = 3) of the heat treatment process to which the adsorbents under study were subjected.

| Adsorbent | Yield (%) |

|---|---|

| Powder + 10%Fe Thermally Treated (PFeTT) | 46 ± 2 |

| Granular + 10%Fe Thermally Treated (GFeTT) | 53 ± 2 |

The highest yield was recorded for the granular adsorbent, which retained approximately 53% of its initial mass reinforcing that the burning process leads to a significant mass reduction, explained by the degradation of volatile compounds (Weber & Quicker, 2018) [22].

Appendix A.2. Calibration Curve

A calibration curve was constructed to quantify the dye concentration in the treated solutions. To this end, six standard solutions of precisely defined concentrations were prepared from dilutions of the synthetic dye stock solution (80 mg/L). The area of the visible spectrum curve resulting from the scan performed for each of the standard solutions was measured in triplicate, allowing the average value to be determined (Table A2). From these values, it was possible to construct the calibration curve.

Table A2.

Measured values for absorbances of standard dye solutions.

Table A2.

Measured values for absorbances of standard dye solutions.

| Standard Solution | Concentration (mg/L) | Area1 | Area2 | Area3 | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 | 2.7452 | 2.9849 | 2.3240 | 2.6847 |

| 2 | 5.0 | 14.105 | 12.480 | 13.287 | 13.291 |

| 3 | 10 | 25.038 | 24.971 | 24.302 | 24.770 |

| 4 | 20 | 49.281 | 49.624 | 50.069 | 49.658 |

| 5 | 50 | 127.17 | 121.98 | 121.54 | 123.56 |

| 6 | 80 | 195.31 | 195.33 | 194.26 | 194.97 |

Appendix A.3. Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS)

Table A3.

Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy analysis of the adsorbent produced from washed granular pine bark (>1 mm).

Table A3.

Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy analysis of the adsorbent produced from washed granular pine bark (>1 mm).

| Symbol | Element | Concentration % (w/w) |  |

| C | Carbon | 58.41 | |

| O | Oxygen | 41.59 |

Table A4.

Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy analysis of the adsorbent produced from washed granular pine bark (>1 mm), impregnated with 10% iron by incipient water impregnation (1 h30).

Table A4.

Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy analysis of the adsorbent produced from washed granular pine bark (>1 mm), impregnated with 10% iron by incipient water impregnation (1 h30).

| Symbol | Element | Concentration % (w/w) |  |

| O | Oxygen | 8.17 | |

| C | Carbon | 4.44 | |

| Fe | Iron | 42.91 | |

| Cl | Chloride | 44.47 |

Table A5.

Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy analysis of the adsorbent produced from washed granular pine bark (>1 mm), impregnated with 10% iron by incipient water impregnation (1 h30), and thermally treated.

Table A5.

Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy analysis of the adsorbent produced from washed granular pine bark (>1 mm), impregnated with 10% iron by incipient water impregnation (1 h30), and thermally treated.

| Symbol | Element | Concentration % (w/w) |  |

| C | Carbon | 17.92 | |

| O | Oxygen | 4.02 | |

| Cl | Chloride | 4.87 | |

| Fe | Iron | 73.19 |

Appendix A.4. Color Removal Kinetics

The construction of the kinetic curves was carried out by determining the amount of dye removed normalized by the mass of adsorbent used, using Equation (A1). The results obtained for the various tests performed are presented below.

- (A)

- Granular + 10%Fe Thermally treated (5.0 g/L)

Figure A1.

Evolution of effluent color in the adsorption tests with Granular + 10% Fe heat-treated at a concentration of 5 g/L, carried out for the construction of the color removal kinetic curve.

Table A6.

Sample mass (±0.1 mg) used in duplicates (A and B) of each test carried out with Granular + 10% Fe heat-treated at a concentration of 5 g/L, color removal (%CR), dye concentration determined after treatment and results obtained for standardized color removal.

Table A6.

Sample mass (±0.1 mg) used in duplicates (A and B) of each test carried out with Granular + 10% Fe heat-treated at a concentration of 5 g/L, color removal (%CR), dye concentration determined after treatment and results obtained for standardized color removal.

| Samples Mass (mg) | Color Removal (%) | Concentration (mg/L) | Adsorption Capacity (mgDye/gadsorbent) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (min) | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | Mean |

| 5 | 150.0 | 150.5 | 32.3 | 19.7 | 51.6 | 61.3 | 5.67 | 3.73 | 5 ± 1 |

| 15 | 150.3 | 152.2 | 83.1 | 79.6 | 12.6 | 15.3 | 13.44 | 12.75 | 13.1 ± 0.5 |

| 30 | 150.4 | 150.0 | 91.6 | 94.2 | 6.13 | 4.13 | 14.73 | 15.17 | 15.0 ± 0.3 |

| 60 | 150.1 | 150.8 | 96.3 | 96.2 | 2.54 | 2.59 | 15.48 | 15.40 | 15.44 ± 0.06 |

| 90 | 151.6 | 151.3 | 96.7 | 96.6 | 2.22 | 2.29 | 15.39 | 15.41 | 15.40 ± 0.01 |

| 120 | 150.5 | 150.7 | 96.7 | 96.9 | 2.24 | 2.06 | 15.50 | 15.52 | 15.51 ± 0.01 |

| 240 | 150.8 | 151.0 | 96.8 | 97.1 | 2.17 | 1.90 | 15.48 | 15.52 | 15.50 ± 0.02 |

- (B) Granular + 10%Fe Thermally treated (2.5 g/L)

Table A7.

Sample mass (±0.1 mg) used in duplicates (A and B) of each test carried out with Granular + 10% Fe heat-treated at a concentration of 2.5 g/L, color removal (%CR), dye concentration determined after treatment and results obtained for standardized color removal.

Table A7.

Sample mass (±0.1 mg) used in duplicates (A and B) of each test carried out with Granular + 10% Fe heat-treated at a concentration of 2.5 g/L, color removal (%CR), dye concentration determined after treatment and results obtained for standardized color removal.

| Samples Mass (mg) | Color Removal (%) | Concentration (mg/L) | Adsorption Capacity (mgDye/gadsorbent) | ||||||

| Time (min) | A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | Mean |

| 15 | 76.3 | 76.7 | 87.6 | 86.6 | 21.9 | 24.0 | 22.9 | 21.9 | 22.4 ± 0.7 |

| 30 | 76.0 | 76.1 | 71.1 | 68.3 | 22.2 | 24.7 | 22.8 | 21.8 | 22.3 ± 0.7 |

| 60 | 75.8 | 75.5 | 70.7 | 67.4 | 22.0 | 22.9 | 23.0 | 22.7 | 22.8 ± 0.2 |

| 90 | 76.1 | 75.2 | 71.0 | 69.7 | 20.5 | 22.2 | 23.5 | 23.1 | 23.3 ± 0.3 |

| 120 | 75.5 | 76.5 | 72.9 | 70.7 | 17.4 | 19.6 | 24.9 | 23.7 | 24.3 ± 0.8 |

| 240 | 75.9 | 75.5 | 76.9 | 74.1 | 19.4 | 14.0 | 24.0 | 26.2 | 25 ± 2 |

| 360 | 75.2 | 75.3 | 74.4 | 81.3 | 13.5 | 12.0 | 26.5 | 27.1 | 26.8 ± 0.4 |

| 1440 | 76.0 | 75.2 | 82.0 | 84.0 | 10.8 | 24.0 | 27.3 | 22.3 | 24.8 ± 3 |

Table A8.

Parameters obtained for the fittings to the pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, and Elovich kinetic models, applied to the experimental data related to thermally treated Granular + 10% Fe (GFeTT) adsorbent at a concentration of 5.0 g/L and 2.5 g/L and a dye concentration of 80 mg/L. The R2 values reported were calculated using the mean values of samples A and B for each condition.

Table A8.

Parameters obtained for the fittings to the pseudo-first order, pseudo-second order, and Elovich kinetic models, applied to the experimental data related to thermally treated Granular + 10% Fe (GFeTT) adsorbent at a concentration of 5.0 g/L and 2.5 g/L and a dye concentration of 80 mg/L. The R2 values reported were calculated using the mean values of samples A and B for each condition.

| Pseudo-First Order | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration (mg/L) | qe | k1 | R2 | Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) |

| 2.5 g/L | 24.2 ± 0.6 | 0.16 ± 0.05 | 0.9870 | 13.9306 |

| 5.0 g/L | 15.6 ± 0.3 | 0.10 ± 0.01 | 0.9940 | 3.5590 |

| Pseudo-second order | ||||

| Concentration (mg/L) | qe | k2 | R2 | Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) |

| 2.5 g/L | 25.0 ± 0.6 | 0.016 ± 0.007 | 0.9922 | 8.5536 |

| 5.0 g/L | 16.9 ± 0.9 | 0.008 ± 0.003 | 0.9788 | 12.6762 |

| Elovich | ||||

| Concentration (mg/L) | a | b | R2 | Sum of Squared Errors (SSE) |

| 2.5 g/L | 7 × 105 ± 2 × 106 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 0.9976 | 29.5157 |

| 5.0 g/L | 12 ± 17 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.9406 | 73.9395 |

Appendix A.5. Influence of Adsorbent Concentration on the Removal Efficiency

Table A9.

Sample mass (±0.1 mg) used in duplicates (A and B) of each test carried out with Granular + 10% Fe heat-treated at different concentrations, color removal (%CR), dye concentration determined after 24 h treatment and results obtained for standardized color removal.

Table A9.

Sample mass (±0.1 mg) used in duplicates (A and B) of each test carried out with Granular + 10% Fe heat-treated at different concentrations, color removal (%CR), dye concentration determined after 24 h treatment and results obtained for standardized color removal.

| Absorbent Concentration (g/L) | Samples Mass (mg) | Color Removal (%) | Concentration (mg/L) | Adsorption Capacity (mgDye/gadsorbent) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | A | B | A | B | A | B | Mean | |

| 1.0 | 30.3 | 31.0 | 38.8 | 35.7 | 46.7 | 49.0 | 33.0 | 30.0 | 32 ± 2 |

| 2.5 | 76.0 | 75.2 | 85.5 | 68.3 | 10.8 | 24.0 | 27.3 | 22.3 | 25 ± 4 |

| 5.0 | 152.1 | 152.3 | 97.5 | 97.4 | 1.62 | 1.71 | 15.5 | 15.4 | 15.44 ± 0.03 |

| 7.5 | 225.4 | 226.2 | 98.1 | 98.9 | 1.29 | 0.64 | 10.5 | 10.5 | 10.50 ± 0.03 |

| 10.0 | 300.2 | 301.4 | 99.6 | 99.5 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 8.00 | 7.95 | 7.97 ± 0.03 |

References

- De Felice, F.; Fareed, A.G.; Zahid, A.; Nenni, M.E.; Petrillo, A. Circular Economy Practices in the Textile Industry for Sustainable Future: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 486, 144547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATP Estatísticas. Available online: https://atp.pt/pt-pt/estatisticas/caraterizacao/ (accessed on 11 May 2024).

- BPstat Análise Setorial da Indústria dos Têxteis e Vestuário. Available online: https://bpstat.bportugal.pt/conteudos/publicacoes/1292 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Santos, S.C.R.; Boaventura, R.A.R. Adsorption of Cationic and Anionic Azo Dyes on Sepiolite Clay: Equilibrium and Kinetic Studies in Batch Mode. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 1473–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaly, A.E.; Ananthashankar, R.; Alhattab, M.; Ramakrishnan, V. Production, Characterization and Treatment of Textile Effluents: A Critical Review. J. Chem. Eng. Process Technol. 2014, 5, 1000182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Dash, R.R.; Bhunia, P. A Review on Chemical Coagulation/Flocculation Technologies for Removal of Colour from Textile Wastewaters. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 93, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Decontamination of Textile Wastewater via TiO2/Activated Carbon Composite Materials. Adv. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2010, 159, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azanaw, A.; Birlie, B.; Teshome, B.; Jemberie, M. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering Textile Effluent Treatment Methods and Eco-Friendly Resolution of Textile Wastewater. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 6, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.D.N.; Santana, C.S.; Velloso, C.C.V.; Silva, A.H.M.; Magalhães, F.; Aguiar, A. A Review on the Treatment of Textile Industry Effluents through Fenton Processes. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2021, 155, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.R.; Li, H.B.; Wang, W.H.; Gu, J.D. Degradation of Dyes in Aqueous Solutions by the Fenton Process. Chemosphere 2004, 57, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, E.C.; Santos, S.C.R.; Pintor, A.M.A.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Botelho, C.M.S. Evaluation of a Tannin-Based Coagulant on the Decolorization of Synthetic Effluents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheshwari, K.; Agrawal, M.; Gupta, A.B. Dye Pollution in Water and Wastewater. In Novel Materials for Dye-Containing Wastewater Treatment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Jorge, A.M.S.; Athira, K.K.; Alves, M.B.; Gardas, R.L.; Pereira, J.F.B. Textile Dyes Effluents: A Current Scenario and the Use of Aqueous Biphasic Systems for the Recovery of Dyes. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 55, 104125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, A.C.; Jadhav, N.C. Treatment of Textile Wastewater Using Adsorption and Adsorbents. In Sustainable Technologies for Textile Wastewater Treatments; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2021; ISBN 9780323858298. [Google Scholar]

- Pourhakkak, P.; Taghizadeh, M.; Taghizadeh, A.; Ghaedi, M. Adsorbent; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 33, ISBN 9780128188057. [Google Scholar]

- Mamane, H.; Altshuler, S.; Sterenzon, E.; Vinod, V.K. Decolorization of Dyes from Textile Wastewater Using Biochar: A Review. Acta Innov. 2020, 37, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Xue, S.; Zhao, S.; Yan, J.; Qian, L.; Chen, M. Biochar Supported Nanoscale Iron Particles for the Efficient Removal of Methyl Orange Dye in Aqueous Solutions. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0132067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zazycki, M.A.; Godinho, M.; Perondi, D.; Foletto, E.L.; Collazzo, G.C.; Dotto, G.L. New Biochar from Pecan Nutshells as an Alternative Adsorbent for Removing Reactive Red 141 from Aqueous Solutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaukura, N.; Murimba, E.C.; Gwenzi, W. Sorptive Removal of Methylene Blue from Simulated Wastewater Using Biochars Derived from Pulp and Paper Sludge. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2017, 8, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, D.; Huang, M.; He, J.; Zou, J.; Zhao, L.; Shen, F. Biochar Produced by Combining Lignocellulosic Feedstock and Mushroom Reduces Its Heterogeneity. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 355, 127231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.C.R.; Bacelo, H.A.M.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Botelho, C.M.S. Tannin-Adsorbents for Water Decontamination and for the Recovery of Critical Metals: Current State and Future Perspectives. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 14, e1900060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K.; Quicker, P. Properties of Biochar. Fuel 2018, 217, 240–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young Lee, H.; Gyu Kim, S. Kinetic Study on the Hydrogen Reduction of Ferrous Chloride Vapor for Preparation of Iron Powder. Powder Technol. 2005, 152, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florestas. As Espécies Florestais Mais Comuns da Floresta Portuguesa. Available online: https://florestas.pt/conhecer/as-especies-florestais-mais-comuns-da-floresta-portuguesa/ (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Bacelo, H.; Santos, S.C.R.; Ribeiro, A.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Botelho, C.M.S. Antimony Removal from Water by Pine Bark Tannin Resin: Batch and Fixed-Bed Adsorption. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 302, 114100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacelo, H.; Santos, S.C.R.; Botelho, C.M.S. Removal of Arsenic from Water by an Iron-Loaded Resin Prepared from Pinus Pinaster Bark Tannins. Euro-Mediterr. J. Environ. Integr. 2020, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Santos, P.; Zanuso, E.; Genisheva, Z.; Rocha, C.M.R.; Teixeira, J.A. Green and Sustainable Valorization of Bioactive Phenolic Compounds from Pinus By-Products. Molecules 2020, 25, 2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentín, L.; Kluczek-Turpeinen, B.; Willför, S.; Hemming, J.; Hatakka, A.; Steffen, K.; Tuomela, M. Scots Pine (Pinus sylvestris) Bark Composition and Degradation by Fungi: Potential Substrate for Bioremediation. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 2203–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abad Viñas, R.; Caudullo, G.; Oliveira, S.; de Rigo, D. Pinus Pinea in Europe: Distribution, Habitat, Usage and Threats. In European Atlas of Forest Tree Species; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016; pp. 130–131. [Google Scholar]

- Erden, E.; Kaymaz, Y.; Pazarlioglu, N.K. Biosorption Kinetics of a Direct Azo Dye Sirius Blue K-CFN by Trametes Versicolor. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 14, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World—Direct Dyes and Preparations Based Thereon—Market Analysis, Forecast, Size, Trends and Insights. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/dye (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- Global Direct Dyes Market (DATAINTELO from Maharashtra, India). 2025. Available online: https://dataintelo.com/report/global-direct-dyes-market (accessed on 23 May 2025).

- KANTOĞLU, Ö. The Decolorization and Detoxification of Astrazon Red FBL Solution by Gamma Radiation. J. Sci. Technol. Düzce Univ. 2023, 11, 358–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messele, S.A.; Soares, O.S.G.P.; Órfão, J.J.M.; Stüber, F.; Bengoa, C.; Fortuny, A.; Fabregat, A.; Font, J. Zero-Valent Iron Supported on Nitrogen-Containing Activated Carbon for Catalytic Wet Peroxide Oxidation of Phenol. Appl. Catal. B 2014, 154–155, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güven, D.E.; Akinci, G. Comparison of Acid Digestion Techniques to Determine Heavy Metals in Sediment and Soil Samples. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. 2011, 24, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Basic Red 46, Technical Grade|LGC Standards. Available online: https://www.lgcstandards.com/PT/pt/Basic-Red-46-Technical-Grade/p/TRC-B118733?queryID=ea673ab82db11bc27b5ab17a78898b7c (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Direct Blue 85. Available online: https://www.worlddyevariety.com/direct-dyes/direct-blue-85.html (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Direct Yellow 86. Available online: https://www.worlddyevariety.com/direct-dyes/direct-yellow-86.html (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Hu, E.; Shang, S.; Tao, X.; Jiang, S.; Chiu, K. Regeneration and Reuse of Highly Polluting Textile Dyeing Ef Fl Uents through Catalytic Ozonation with Carbon Aerogel Catalysts. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1055–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonin, J.P. On the Comparison of Pseudo-First Order and Pseudo-Second Order Rate Laws in the Modeling of Adsorption Kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 300, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.C.; Tseng, R.L.; Juang, R.S. Characteristics of Elovich Equation Used for the Analysis of Adsorption Kinetics in Dye-Chitosan Systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 150, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babuponnusami, A.; Muthukumar, K. A Review on Fenton and Improvements to the Fenton Process for Wastewater Treatment. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 557–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.T.; Lai, C.W.; Hsien, K.J. Effect of Particle Size of Activated Clay on the Adsorption of Paraquat from Aqueous Solution. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2003, 263, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, D.; Daverey, A.; Dutta, K.; Yata, V.K.; Arunachalam, K. Valorization of Waste Pine Needle Biomass into Biosorbents for the Removal of Methylene Blue Dye from Water: Kinetics, Equilibrium and Thermodynamics Study. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 25, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabar, J.M.; Adebayo, M.A.; Taleat, T.A.A.; Yılmaz, M.; Rangabhashiyam, S. Ipoma Batatas (Sweet Potato) Leaf and Leaf-Based Biochar as Potential Adsorbents for Procion Orange MX-2R Removal from Aqueous Solution. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2025, 185, 106876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusegun, S.J.; Souza, T.G.F.; Souza, G.d.O.; Osial, M.; Mohallem, N.D.S.; Ciminelli, V.S.T.; Krysinski, P. Iron-Based Materials for the Adsorption and Photocatalytic Degradation of Pharmaceutical Drugs: A Comprehensive Review of the Mechanism Pathway. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 51, 103457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayoud, N.; Tahiri, S.; Alami Younssi, S.; Albizane, A.; Gallart-Mateu, D.; Cervera, M.L.; de la Guardia, M. Kinetic, Isotherm and Thermodynamic Studies of the Adsorption of Methylene Blue Dye onto Agro-Based Cellulosic Materials. Desalination Water Treat. 2016, 57, 16611–16625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintor, A.M.A.; Vieira, B.R.C.; Santos, S.C.R.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Botelho, C.M.S. Arsenate and Arsenite Adsorption onto Iron-Coated Cork Granulates. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 1075–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALSamman, M.T.; Sánchez, J. Recent Advances on Hydrogels Based on Chitosan and Alginate for the Adsorption of Dyes and Metal Ions from Water. Arab. J. Chem. 2021, 14, 103455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazari Moghaddam, N.S.; Al-Musawi, T.J.; Arghavan, F.S.; Nasseh, N. Effective Removal of Sirius Yellow K-CF Dye by Adsorption Process onto Chitosan-Polyacrylamide Composite Loaded with ZnO Nanoparticles. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2023, 103, 8782–8798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangoremi, A.A. Adsorption Kinetic Models and Their Applications: A Critical Review. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2025, XII, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandani, S. Kinetics of Liquid Phase Batch Adsorption Experiments. Adsorption 2021, 27, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zermane, F.; Cheknane, B.; Bouras, O. Bio Sorption of Textile Dyes from Aqueous Solution onto Three Different Pine Barks: Kinetics and Isotherm Studies. J. Renew. Energ. 2019, 22, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardejani, F.D.; Badii, K.; Limaee, N.Y.; Mahmoodi, N.M. Numerical Modelling and Laboratory Studies on the Removal of Direct Red 23 and Direct Red 80 Dyes from Textile Effluents Using Orange Peel, a Low-Cost Adsorbent. Dye. Pigment. 2007, 73, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruna; Bagotia, N.; Sharma, A.K.; Kumar, S. A Review on Modified Sugarcane Bagasse Biosorbent for Removal of Dyes. Chemosphere 2021, 268, 129309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadaf, S.; Bhatti, H.N. Batch and Fixed Bed Column Studies for the Removal of Indosol Yellow BG Dye by Peanut Husk. J. Taiwan. Inst. Chem. Eng. 2014, 45, 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, I.T.; Santos, S.C.R.; Boaventura, R.A.R.; Botelho, C.M.S. Optimization of Microwave-Assisted Extraction of Phenolic Compounds from Chestnut Processing Waste Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 395, 136452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiviskä, T.; Santos, S.C.R. Purifying Water with Plant-Based Sustainable Solutions: Tannin Coagulants and Sorbents. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 23, 101004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debord, J.; Harel, M.; Bollinger, J.; Hoong, K. The Elovich Isotherm Equation: Back to the Roots and New Developments. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2022, 262, 118012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Lv, L.; Pan, B.C.; Zhang, Q.J.; Zhang, W.M.; Zhang, Q.X. Critical Review in Adsorption Kinetic Models. J. Zhejiang Univ.-Sci. A 2009, 10, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministério do Ambiente. Decreto-Lei n.o 236/98 de 1 de Agosto; Ministério Do Ambiente, 1998. Available online: https://diariodarepublica.pt/dr/en/detail/decree-law/236-1998-430457 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/en/#iso:std:iso:14040:ed-2:v1:en (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Ji, C.; Cheng, K.; Nayak, D.; Pan, G. Environmental and Economic Assessment of Crop Residue Competitive Utilization for Biochar, Briquette Fuel and Combined Heat and Power Generation. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 916–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, H.; Johansson, L.; Carvalho, L.; Thorin, E.; Yu, Z.; Yu, X.; Skreiberg, Ø. A Critical Review on Production, Modification and Utilization of Biochar. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 161, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).