Integrated Hydrogeochemical, Isotopic, and Geophysical Assessment of Groundwater Salinization Processes in the Samba Dia Coastal Aquifer (Senegal)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area

2.1. Geographic Location and Climate

2.2. Geology and Hydrogeology

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Workflow

- Groundwater sampling was conducted in 31 shallow wells (2–12 m depth), selected based on proximity to suspected saline interfaces and local surface salt zones.

- Physicochemical parameters, including temperature, electrical conductivity, pH, and TDS, were measured in situ.

- Major ion concentrations were analyzed by ion chromatography, with quality control performed via ion balance checks (<±5% error).

- Stable isotope ratios (δ18O and δ2H) were determined using laser spectroscopy, with reported precisions of ±0.1‰ and ±1‰, respectively.

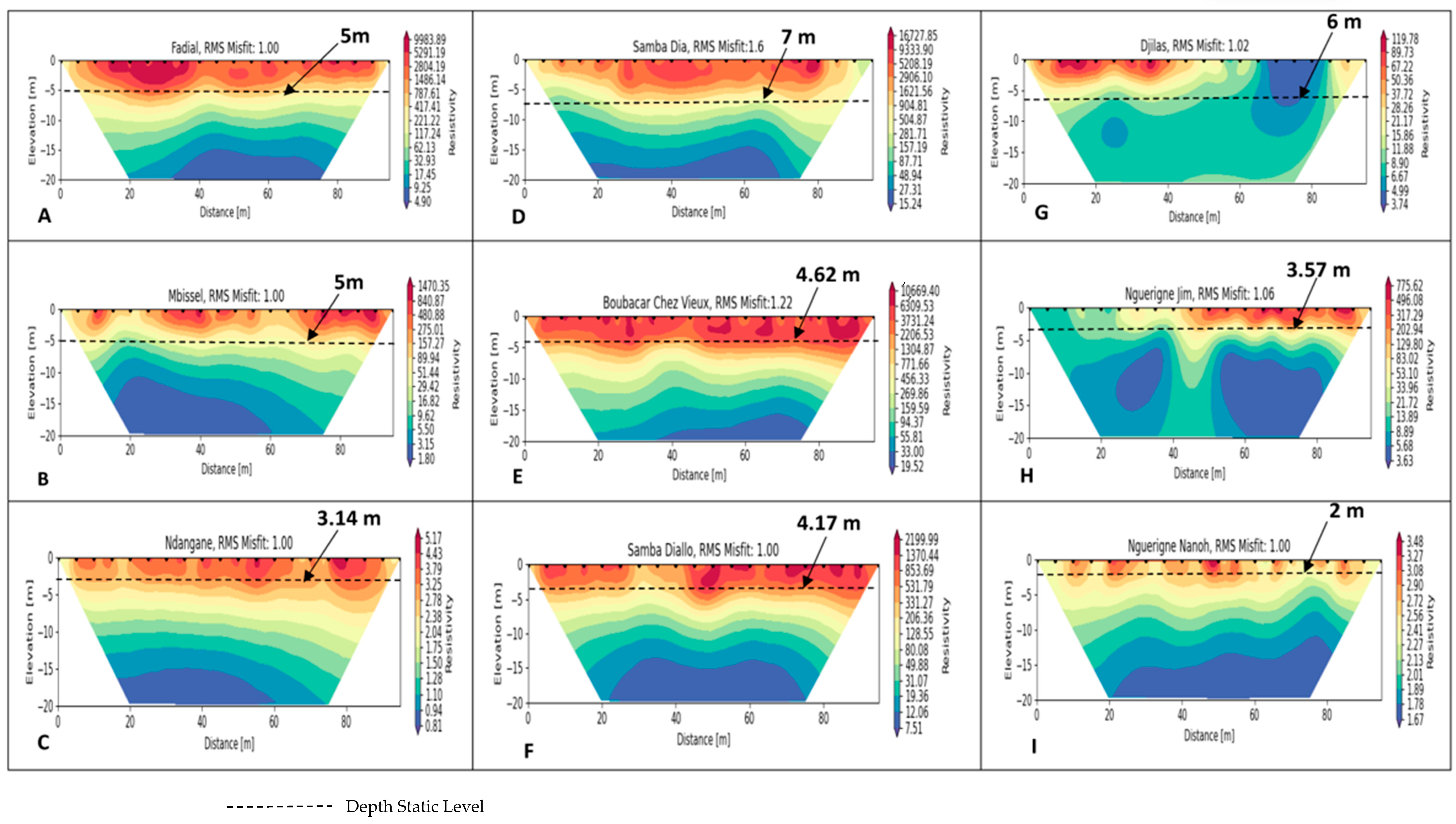

- The ERT surveys were conducted to map subsurface resistivity variations indicative of groundwater salinity. Details of the data acquisition, array configuration, and inversion procedures are provided in Section 3.3.

- Hydrogeochemical data, isotopic signatures, and geophysical results were integrated through spatial mapping and multivariate analyses to interpret salinization dynamics and identify dominant salinity sources.

3.2. Hydrochemical and Isotopic Investigations

3.3. Geophysical Investigations

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Hydrochemistry and Water Stable Isotopes

4.1.1. Electrical Conductivity and Chloride

4.1.2. Salinity Origin: Use of Hydrochemical Facies Evolution Diagram and Classification of Stuyfzand

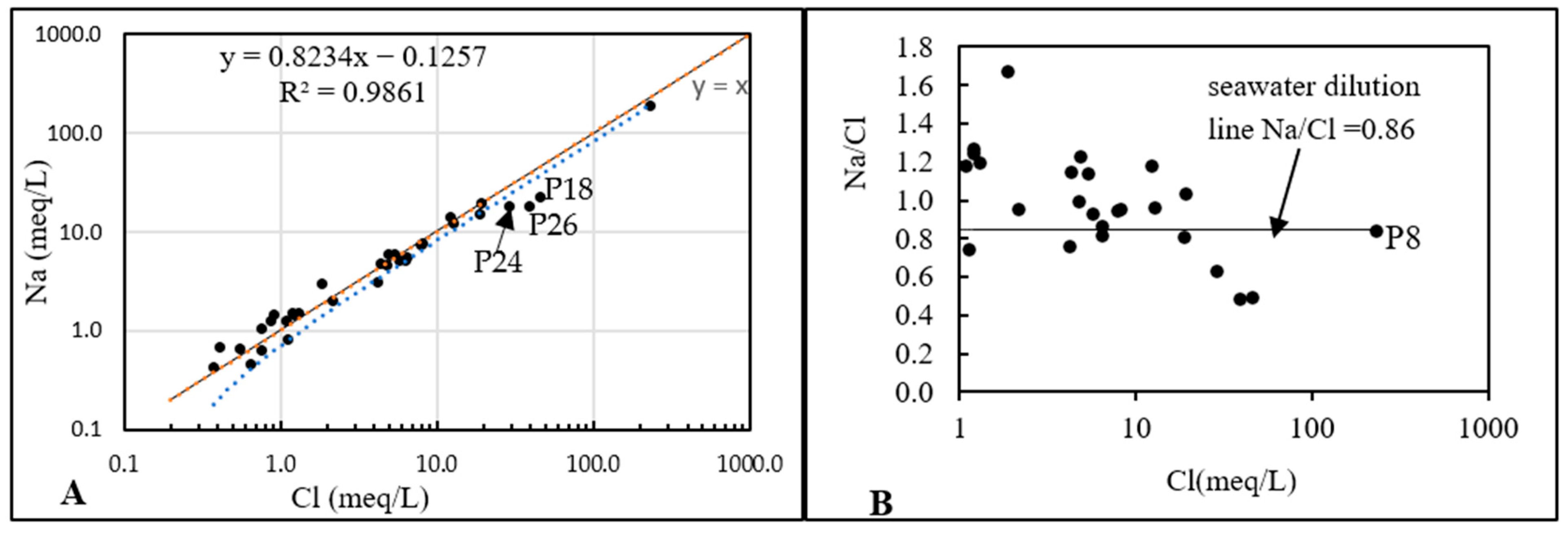

4.1.3. Na+/Cl− Correlation

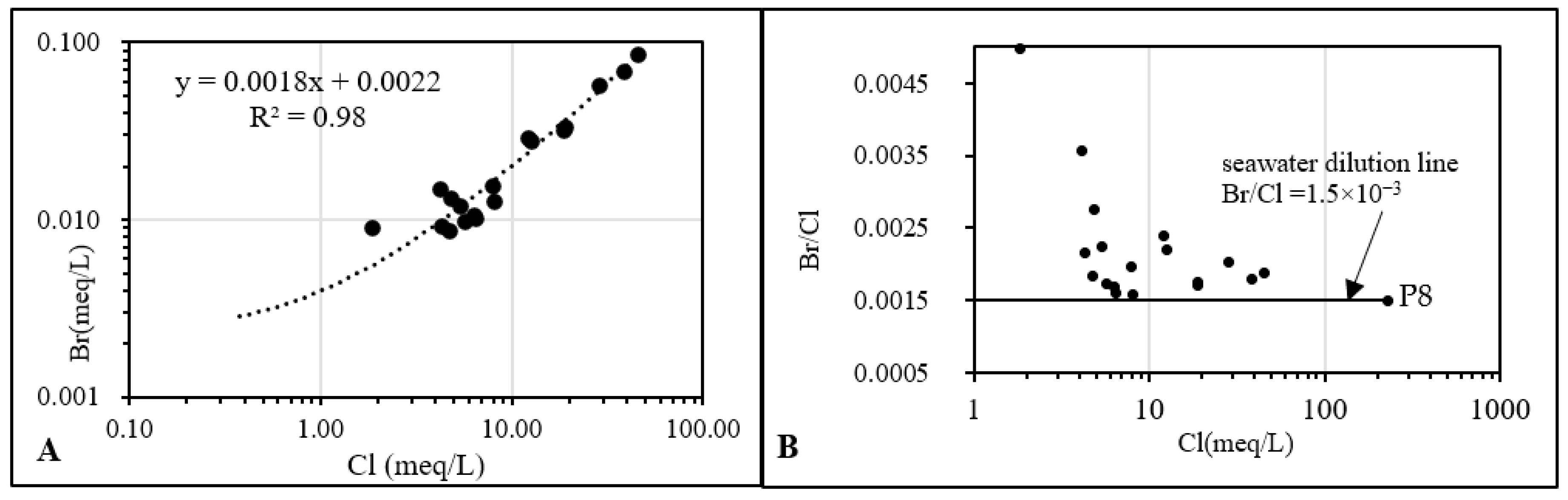

4.1.4. Br−/Cl− Correlation

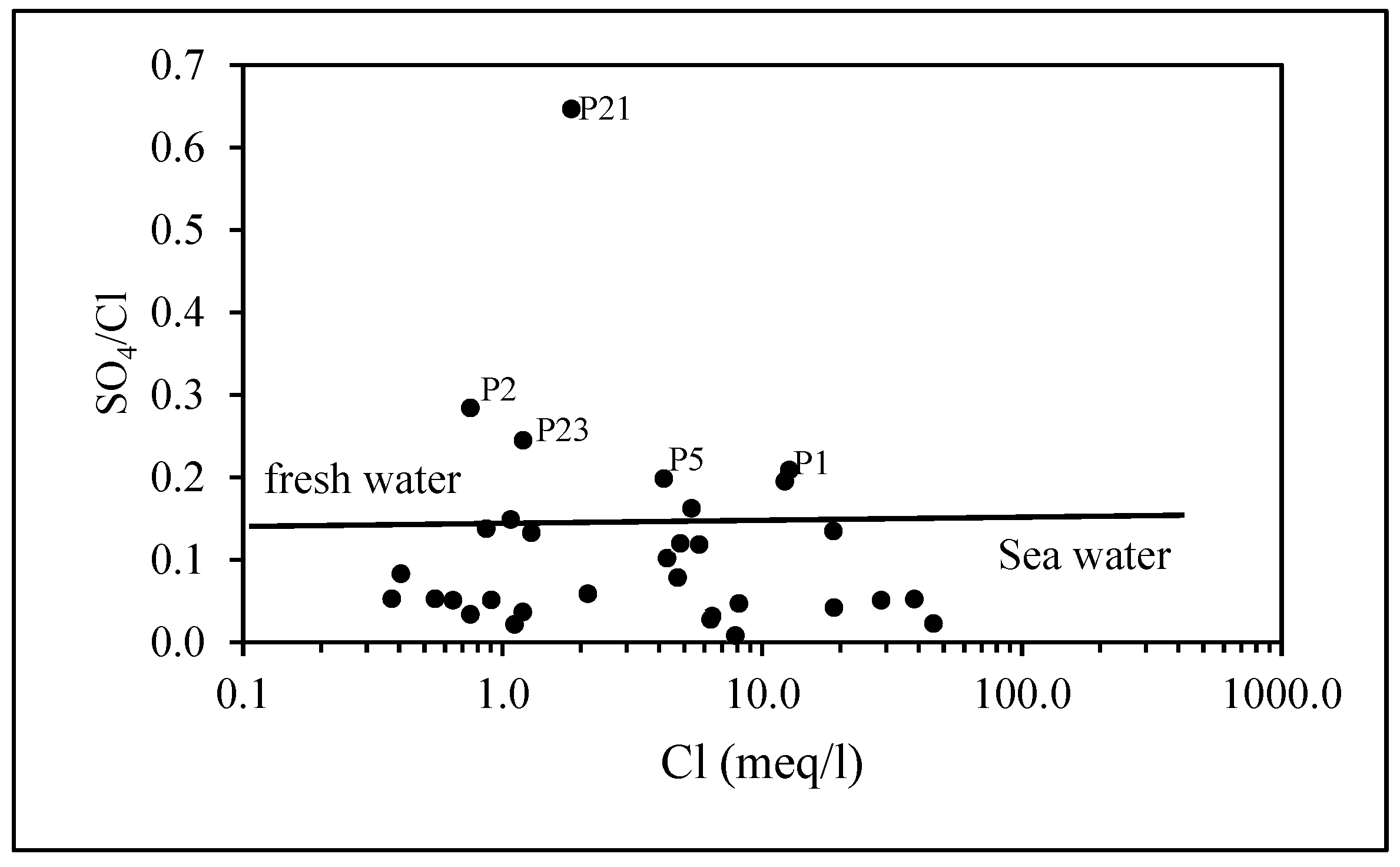

4.1.5. SO42−/Cl− Correlation

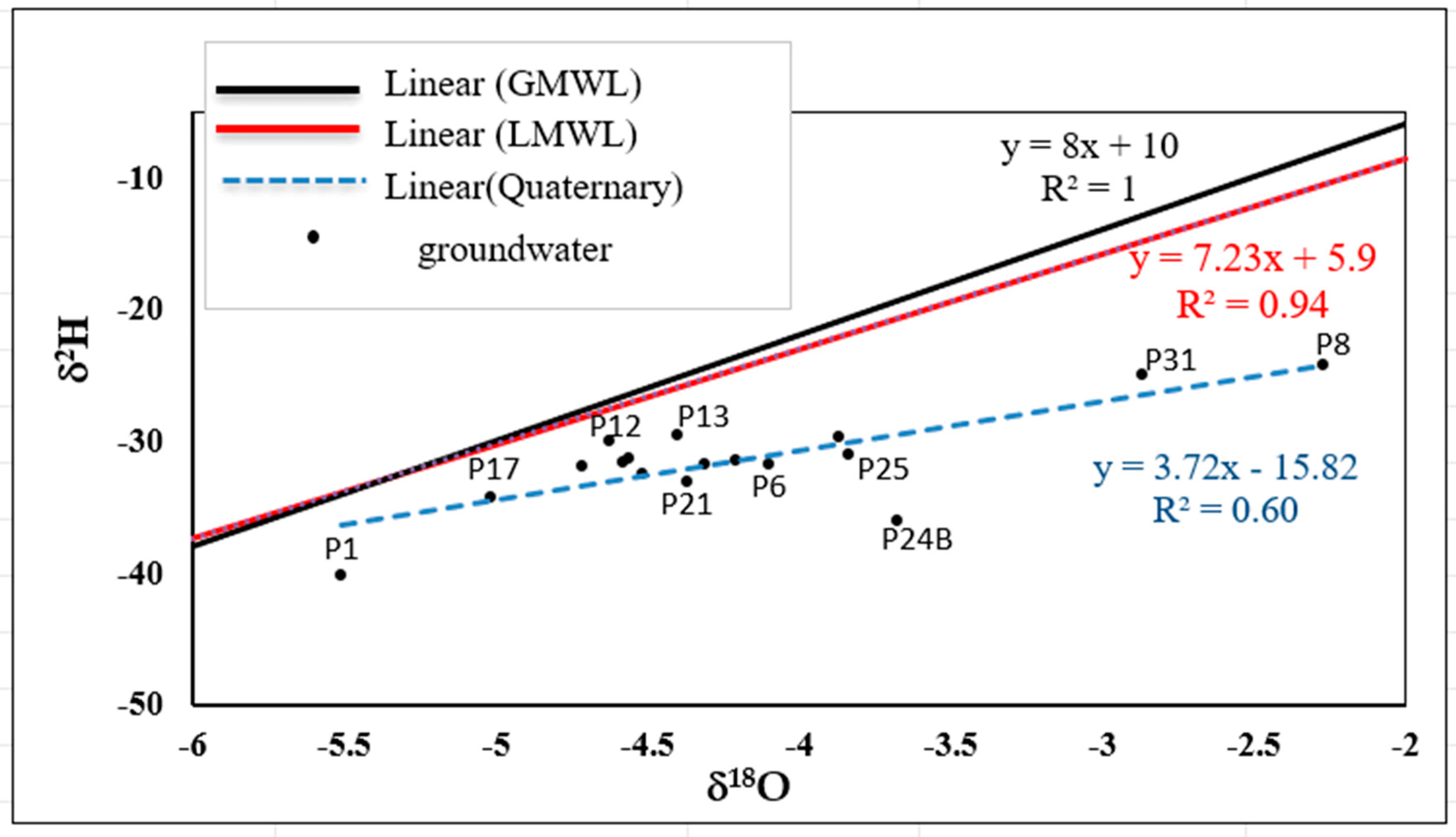

4.1.6. Water Stable Isotopes (δ18O and δ2H)

4.2. Geophysical

4.3. Applications and Limitations

5. Conclusions

- Central recharge zones (10–15 m of freshwater, resistivity > 7 Ω·m);

- Peripheral intrusion fronts (resistivity < 5 Ω·m, Na/Cl < 0.86);

- Inland leaching-prone zones (mixed facies, elevated SO4/Cl).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morsli, B.; Habi, M.; Bouchekara, B. Study of marine intrusion in coastal aquifers and its repercussions on the land degradation by the use of a multidisciplinary approach. Larhyss J. 2017, 30, 225–237. [Google Scholar]

- Marjoua, A.; Olive, P.; Jusserand, C. Apports des outils chimiques et isotopiques à l’identification des origines de la salinisation des eaux: Cas de la nappe de La Chaouia côtière (Maroc). Rev. Sci. l’eau/J. Water Sci. 1997, 10, 489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Oude Essink, G.H. Improving fresh groundwater supply—Problems and solutions. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2001, 44, 429–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapti-Caputo, D. Influence of climatic changes and human activities on the salinization process of coastal aquifer systems. Ital. J. Agron. 2010, 5, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay, R.; Khobragade, P.; Mohapatra, P.K. Assessment of groundwater quality in Puri City, India: An impact of anthropogenic activities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2011, 177, 409–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prusty, P.; Farooq, S.H. Farooq-Seawater intrusion in the coastal aquifers of India—A review. HydroResearch 2020, 3, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marius, C. Effets de la sécheresse sur l’évolution phytogéographique et pédologique de la mangrove en basse Casamance. Bull. de l’IFAN 1979, 41, 669–691. [Google Scholar]

- Sarr, R. Etude Géologique et Hydrogéologique de la Zone de Joal-Fadiouth (Sénégal). Ph.D. Thesis, Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar, Dakar, Sénégal, 1982; 166p. [Google Scholar]

- Plaud, M. Les Lentilles D’eau Douce des iles du Bas-Saloum; BRGM, SN-CNDEA: Dakar, Sénégal, 1967; 74p. [Google Scholar]

- Leroux, M. La dynamique de la grande sécheresse sahélienne/Dynamics of the Great Sahelian Drought. Rev. Géogr. Lyon 1995, 70, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaye, A.T.; Sylla, M.B. Scenarios Climatiques au Sénégal. Laboratoire de Physique de l’atmosphère et de l’océan S F (LPAO-SF); Ecole Supérieure Polytechnique Université Cheikh Anta Diop: Dakar, Sénégal, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Travi, Y. Origine des fortes teneurs en fluor des eaux souterraines de la nappe paléocène de la région de Mbour (Senegal): Le rôle de l’ion magnésium. C. R. Acad. Sci. Paris 1984, 298, 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Mudry, J.; Travi, Y. Enregistreurs et indicateurs de l’évolution de l’environnement en zone tropicale. In Sécheresse Sahélienne et Action Anthropique—Deux Facteurs Conjugués de Dégradation des Ressources en eau de l’Afrique de l’Ouest; Sénégal, P., Maire, R., Pomel, S., Salomon, J.-N., Eds.; University of Bordeaux: Bordeaux, France, 1995; pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, E.; Morell, I. Contributions of boron isotopes to understanding the hydrogeochemistry of coastal detritic aquifer of Castellón Plain, Spain. Hydrogeol. J. 2008, 16, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, E. Coastal aquifers of Europe: An overview. Hydrogeol. J. 2010, 18, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Hamouda, M.F.; Tarhouni, J.; Leduc, C.; Zouari, K. Understanding the origin of salinization of the Plio-quaternary eastern coastal aquifer of Cap Bon (Tunisia) using geochemical and isotope investigations. Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 63, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzavand, M.; Ghasemieh, H.; Sadatinejad, S.J.; Bagheri, R. An overview on source, mechanism and investigation approaches in groundwater salinization studies. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 17, 2463–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrino, L.; Gaiolini, M.; Cellone, F.A.; Colombani, N.; Mastrocicco, M.; Cosma, M.; Da Lio, C.; Donnici, S.; Tosi, L. Salinity origin in the coastal aquifer of the Southern Venice lowland. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faye, S. Apports des Outils Géochimiques et Isotopiques à L’identification des Sources de Salinité et à L’évaluation du Régime D’écoulement de la Nappe du Saloum. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal, 2005; 153p. [Google Scholar]

- Ramatlapeng, G.J.; Atekwana, E.A.; Ali, H.N.; Njilah, I.K.; Ndondo, G.R.N. Assessing salinization of coastal groundwater by tidal action: The tropical Wouri Estuary, Douala, Cameroon. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2021, 36, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunadha Rao, V.V.S.; Rao, G.T.; Surinaidu, L.; Rajesh, R.; Mahesh, J. Geophysical and Geochemical Approach for Seawater Intrusion Assessment in the Godavari Delta Basin, AP, India. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2011, 217, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, V.; Nakhaei, M.; Lak, R.; Kholghi, M. Geophysical, isotopic, and hydrogeochemical tools to identify potential impacts on coastal groundwater resources from Urmia hypersaline Lake, NW Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 16738–16760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carol, E.; Perdomo, S.; Álvarez, M.D.P.; Tanjal, C.; Bouza, P. Hydrochemical, Isotopic, and Geophysical Studies Applied to the Evaluation of Groundwater Salinization Processes in Quaternary Beach Ridges in a Semiarid Coastal Area of Northern Patagonia, Argentina. Water 2021, 13, 3509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nefzaoui, F.; Ben Hamouda, M.F.; Carreira, P.M.; Marques, J.M.; Eggenkamp, H.G.M. Evidence for Groundwater Salinity Origin Based on Hydrogeochemical and Isotopic (2H, 18O, 37Cl, 3H, 13C, 14C) Approaches: Sousse, Eastern Tunisia. Water 2023, 15, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalá, F.J.; Custodio, E. Using the Cl/Br ratio as a tracer to identify the origin of salinity in aquifers in Spain and Portugal. J. Hydrol. 2008, 359, 189–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, V.; Nakhaei, M.; Lak, R.; Kholghi, M. Assessment of seasonal groundwater quality and potential saltwater intrusion: A study case in Urmia coastal aquifer (NW Iran) using the groundwater quality index (GQI) and hydrochemical facies evolution diagram (HFE-D). Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2016, 30, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, V.; Nakhaei, M.; Lak, R.; Kholghi, M. Investigating the salinization and freshening processes of coastal groundwater resources in Urmia aquifer, NW Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, V.; Bhattacharya, P.; Nakhaei, M. The hydrogeochemical evaluation of groundwater resources and their suitability for agricultural and industrial uses in an arid area of Iran. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 12, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M.; Gilad, D.; Ronen, A.; Melloul, A. Mapping of seawater intrusion into the coastal aquifer of Israel by the time domain electromagnetic method. Geoexploration 1991, 28, 153–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouhamdouch, S.; Bahir, M.; Ouazar, D.; Rafik, A. Hydrochemical characteristics of aquifers from the coastal zone of the Essaouira basin (Morocco) and their suitability for domestic and agricultural uses. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 8, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoye, S.; Diedhiou, M.; Celle, H.; Faye, S.; Baalousha, M.; Le Coustumer, P. Hydrogeochemical characterization of groundwater in a coastal area, central western Senegal. Front. Water 2023, 4, 1097396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarr, A.; Ndoye, S.; Faye, S. Caractérisation hydrogéochimique de l’aquifère de Samba Dia (Ouest du Sénégal). Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2022, 38, 71–85. [Google Scholar]

- Pitaud, G. Etude Hydrogéologique des Calcaires Paléocènes des Calcaires de Mbour. Evaluation des Ressources en eau et des Possibilités d’exploitation; DGHER-DEH, Rapport de synthèse; Ministère de l’équipement du Sénégal: Dakar, Senegal, 1980.

- Bellion, Y.; Guiraud, R. Le bassin sédimentaire du Senegal. Synthèse des connaissances actuelles. In Bureau des Recherches Géologiques et Minières (BRGM) et Direction des Mines et de la Géologie (DMG); Plan minéral de la république du Senegal, Dakar: Dakar, Senegal, 1984; pp. 4–63. Available online: https://fr.scribd.com/document/868100869/Plan-Mineral-1984-Volume1#start_trial (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Depagne, J.; Mossu, H. Notice Explicative de la Carte Hydrogéologique du Sénégal au 1/500,000 et de la Carte Hydrochimique au 1/1,000,000; BRGM: Orléans, France, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Tessier, F. Contribution à la stratigraphie et à la paléontologie de la partie ouest du Sénégal (Crétacé et Tertiaire). Bull. Dir. Mines Afr. Occid. 1950, 14, 570. [Google Scholar]

- Travi, Y.; Gac Jean-Yves Fontes, J.C.; Fritz, B. Reconnaissance chimique et isotopique des eaux de pluie au Sénégal. Géodynamique 1987, 2, 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- Madioune, D.H.; Faye, S.; Orban, P.; Brouyère, S.; Dassargues, A.; Mudry, J.; Stumpp, C.; Maloszewski, P. Application of isotopic tracers as a tool for understanding hydrodynamic behavior of the highly exploited Diass aquifer system (Senegal). J. Hydrol. 2014, 511, 443–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, H. Isotopic variations in meteoric waters. Science 1961, 133, 1702–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuyfzand, P.J. A new hydrochemical classification of water types: Principles and application to the coastal dunes aquifer system of the Netherlands. In Proceedings of the 9th Salt Water Intrusion Meeting, Delft, The Netherlands, 12–16 May 1986; pp. 641–655. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenez-Forcada, E. Dynamic of sea water interface using hydrochemical facies evolution diagram. Groundwater 2010, 48, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoye, S.; Razack, M.; Faye, S.; Gaye, C.B. Application des méthodes statistiques multivariées et de la classification de Stuyfzand pour la caractérisation des eaux souterraines de l’aquifère côtier du Saloum, Sénégal. Afr. Sci. 2017, 13, 200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Pilla, G.; Torrese, P. Hydrochemical-geophysical study of saline paleo-water contamination in alluvial aquifers. Hydrogeol. J. 2022, 30, 511–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakis, N.; Pavlou, A.; Vargemezis, G.; Voudouris, K.S.; Soulios, G.; Pliakas, F.; Tsokas, G. Seawater intrusion mapping using electrical resistivity tomography and hydrochemical data. An application in the Coastal Area of Eastern Thermaikos Gulf, Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 543, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainone, M.L.; Rusi, S.; Torrese, P. Mud volcanoes in central Italy: Subsoil characterization through a multidisciplinary approach. Geomorphology 2015, 234, 228–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, M.H.; Barker, R.D. Rapid Least-Squares Inversion of Apparent Resistivity Pseudosections by a Quasi-Newton Method. Geophys. Prospect. 1996, 44, 131–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loke, M.H.; Acworth, I.; Dahlin, T. A comparison of smooth and blocky inversion methods in 2D electrical imaging surveys. Explor. Geophys. 2003, 34, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arato, A.; Godio, A.; Sambuelli, L. Staggered grid inversion of cross hole 2-D resistivity tomography. J. Appl. Geophys. 2014, 107, 60–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrese, P. Investigating karst aquifers: Using pseudo-3-D electrical resistivity tomography to identify major karst features. J. Hydrol. 2020, 580, 124257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelgesang, J.A.; Holt, N.; Schilling, K.E.; Gannon, M.; Tassier-Surine, S. Using high-resolution electrical resistivity to estimate hydraulic conductivity and improve characterization of alluvial aquifers. J. Hydrol. 2020, 580, 123992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlemann, S.; Kuras, O.; Richards, L.A.; Naden, E.; Polya, D.A. Polya-Electrical resistivity tomography determines the spatial distribution of clay layer thickness and aquifer vulnerability, Kandal Province, Cambodia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2017, 147, 402–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guérin, R. Borehole and surface-based hydrogeophysics. Hydrogeol. J. 2005, 13, 251–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comte, J.C.; Banton, O. Apport de la tomographie électrique à la modélisation des intrusions salines dans les aquifères côtiers. Exemple des aquifères gréseux des Îles-de-la-Madeleine (Québec, Canada). In Proceedings of the 5e Colloque GEOFCAN, Orléans, France, 20–21 September 2007; pp. 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S.R.; Ingham, M.; McConchie, J.A. The applicability of earth resistivity methods for saline interface definition. J. Hydrol. 2006, 316, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batayneh, A. Use of Electrical Resistivity Methods for Detecting Subsurface Fresh and Saline Water and Delineating Their Interfacial Configuration: A Case Study of the Eastern Dead Sea Coastal Aquifers, Jordan. Hydrogeol. J. 2006, 14, 1277–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuras, O.; Ogilvy, R.D.; Meldrum, P.I.; Gisbert, J.; Jorreto, S.; Francés, I.; Vallejos, A.; Sánchez Martos, F.; Calaforra, J.M.; Pulido Bosch, A. Monitoring coastal aquifers with Automated Time-Lapse Electrical Resistivity Tomography (ALERT): Initial results from the Andarax delta, SE Spain. In Proceedings of the Gestion Intégrée des Ressources en Eaux et Défis du Développement Durable (GIRE3D), Marrakech, Morocco, January 2006; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/259228467_Monitoring_coastal_aquifers_with_Automated_time-Lapse_Electrical_Resistivity_Tomography_ALERT_Initial_results_from_the_Andarax_delta_SE_Spain (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Kok, A. The use of mapping the salinity distribution using geophysics on the Island of Terschelling for groundwater model calibration. In Proceedings of the 20th SWIM Salt Water Intrusion Meeting, Naples, FL, USA, 23–27 June 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlin, T. 2D resistivity surveying for environmental and engineering applications. First Break 1996, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rücker, C.; Günther, T.; Wagner, F.M. PyGIMLi: An open-source library for modelling and inversion in geophysics. Comput. Geosci. 2017, 109, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahir, M.; Ouazar, D.; Ouhamdouch, S.; Zouari, K. Assessment of groundwater mineralization of alluvial coastal aquifer of essaouira basin (Morocco) using the hydrochemical facies evolution diagram (HFE-Diagram). Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 11, 100487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammoun, S.; Trabelsi, R.; Re, V.; Zouari, K. Coastal Aquifer Salinization in Semi-Arid Regions: The Case of Grombalia (Tunisia). Water 2021, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.F.; Vengosh, A.; Rosenthal, E.; Yechieli, Y. Geochemical investigations. In Seawater Intrusion in Coastal Aquifers; Bear, J., Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1999; pp. 51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Vengosh, A.; Kloppmann, W.; Marei, A.; Livshitz, Y.; Gutierrez, A.; Banna, M.; Guerrot, C.; Pankratov, I.; Raanan, H. Sources of Salinity and Boron in the Gaza Strip: Natural Contaminant Flow in the Southern Mediterranean Coastal Aquifer. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, 2004WR003344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telahigue, F.; Agoubi, B.; Souid, F.; Kharroubi, A. Assessment of seawater intrusion in an arid coastal aquifer, south-eastern Tunisia, using multivariate statistical analysis and chloride mass balance. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2018, 106, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamouda, B. Approche Hydrogéochimique et Isotopique du Système Aquifère Côtier du CAP BON: Cas des Nappes de la côte Orientale et d’El Haouaria, Tunisie. Ph.D. Thesis, Université du Carthage, Tunis, Tunisia, 2014; 209p. [Google Scholar]

- Apello, C.A.J.; Postama, D. Geochemistry Groundwater and Pollution; CRC Press: London, UK, 1993; 536p. [Google Scholar]

- Fontes, J.C.; Andrews, J.N.; Edmunds, W.M.; Guerre, A.; Travi, Y. Pale recharge by the Niger River (Mali) deduced from the groundwater geochemistry. Water Resour. Res. 1991, 27, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starinsky, A.; Bielski, M.; Ecker, A.; Steinitz, G. Tracing the origin of salts in groundwater by Sr isotopic composition (the Crystalline Complex of the southern Sinai, Egypt). Chem. Geol. 1983, 41, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengosh, A.; Pankratov, I. Chloride/Bromide and Chloride/Fluoride Ratios of Domestic Sewage Effluents and Associated Contaminated Ground Water. Groundwater 1998, 36, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnayake, M.S.; Senarathne, S.L.; Diyabalanage, S.; Bandara, C.; Wickramarathne, S.; Chandrajith, R. Processes of Groundwater Contamination in Coastal Aquifers in Sri Lanka: A Geochemical and Isotope-Based Approach. Water 2025, 17, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsissoua, Y.; Mudry, J.; Mania, J.; Bouchaou, L.; Chauve, P. Utilisation du rapport Br/Cl pour déterminer l’origine de la salinité des eaux souterraines: Exemple de la plaine du Souss (Maroc). Comptes Rendus L’acad. Des Sci.-Ser. IIA-Earth Planet. Sci. 1999, 328, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Lee, K.; Koh, D.; Lee, D.; Lee, S.; Park, W.; Koh, G.; Woo, N. Hydrogeochemical and isotopic evidence of groundwater salinization in a coastal aquifer: A case study in Jeju volcanic island, Korea. J. Hydrol. 2003, 270, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzourra, H.; Bouhlila, R.; Elango, L.; Slama, F.; Ouslati, N. Characterization of mechanisms and processes of groundwater salinization in irrigated coastal area using statistics, GIS, and hydrogeochemical investigations. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 2643–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabelsi, R.; Abid, K.; Zouari, K.; Yahyaoui, H. Groundwater salinization processes in shallow coastal aquifer of Djeffara plain of Medenine, Southeastern Tunisia. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 66, 641–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vengosh, A. Salinization and saline environments. In Environmental Geochemistry, Treatise in Geochemistry; Sherwood Lollar, B., Ed.; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2003; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Telahigue, F.; Mejri, H.; Mansouri, B.; Souid, F.; Agoubi, B.; Chahla, A.; Kharroubi, A. Assessing seawater intrusion in arid and semi-arid Mediterranean coastal aquifers using geochemical approaches. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2020, 115, 102811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Lebouef, P. Seawater intrusion and associated processes in a small coastal complex aquifer (Castell de Ferro, Spain). Appl. Geochem. 2004, 19, 1517–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndoye, S.; Fontaine, C.; Gaye, C.B.; Razack, M. Groundwater Quality and Suitability for Different Uses in the Saloum Area of Senegal. Water 2018, 10, 1837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, N.; Celle-Jeanton, H.; Huneau, F.; Le Coustumer, P.; Lavastre, V.; Bertrand, G.; Charrier, G.; Clauzet, M.L. Isotopic and geochemical identification of main groundwater supply sources to an alluvial aquifer, the Allier River valley (France). J. Hydrol. 2014, 508, 181–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, P.M.; Bahir, M.; Salah, O.; Galego Fernandes, P.; Nunes, D. Tracing Salinization Processes in Coastal Aquifers Using an Isotopic and Geochemical Approach: Comparative Studies in Western Morocco and Southwest Portugal. Hydrogeol. J. 2018, 26, 2595–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontes, J.C. Isotopes du Milieu et Cycle des Eaux Naturelles: Quelques Aspects. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Paris, Paris, France, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Manu, E.; De Lucia, M.; Akiti, T.T.; Kühn, M. Stable Isotopes and Water Level Monitoring Integrated to Characterize Groundwater Recharge in the Pra Basin, Ghana. Water 2023, 15, 3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Salem, H.S.; Gemail, K.S.; Junakova, N.; Ibrahim, A.; Nosair, A.M. An Integrated Approach for Deciphering Hydrogeochemical Processes during Seawater Intrusion in Coastal Aquifers. Water 2022, 14, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreis, M.B.; Taupin, J.D.; Patris, N.; Vergnaud-Ayraud, V.; Leduc, C.; Lachassagne, P.; Martins, E.S.P.R. Explaining the groundwater salinity of hard-rock aquifers in semi-arid hinterlands using a multidisciplinary approach. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2025, 68, 2189–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binley, A.; Kemna, A. Electrical resistivity tomography. In Hydrogeophysics; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 113–143. [Google Scholar]

| Main Type | Code | [Cl−1] (mg L−1) |

|---|---|---|

| Fresh | F | ≤150 |

| Fresh-brackish | Fb | 150–300 |

| Brackish | B | 300–1000 |

| Brackish-salt | Bs | 1000–10,000 |

| Salt | S | 10,000–20,000 |

| Hyper haline | H | >20,000 |

| Wells | Name | T °C | pH | TDS (mg L−1) | EC (μS cm−1) | Ca (mg L−1) | Mg (mg L−1) | Na (mg L−1) | K (mg L−1) | HCO3 (mg L−1) | Cl (mg L−1) | Br (mg L−1) | SO4 (mg L−1) | NO3 (mg L−1) | δ2H | δ18O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | kobongoye2_E | 24.5 | 7.3 | 1106 | 1940 | 63.75 | 30.82 | 281.50 | 6.16 | 85.40 | 451.30 | 2.23 | 127.50 | 53.91 | −40.2 | −5.51 |

| P2 | kobongoye2 | 27.4 | 6.9 | 211 | 366 | 23.27 | 2.70 | 24.77 | 1.41 | 48.80 | 26.63 | <LOD | 10.23 | 72.64 | - | - |

| P3 | Kobongoye 1 | 27.7 | 7.3 | 193 | 279 | 15.32 | 4.92 | 35.60 | 0.77 | 73.20 | 45.78 | <LOD | 8.23 | 9.38 | - | - |

| P4 | Samba Dia Forage | 29.8 | 7.6 | 286 | 413 | 36.40 | 5.38 | 34.03 | 0.45 | 170.80 | 32.04 | <LOD | 2.23 | 4.14 | - | - |

| P5 | Samba Dia M | 29.1 | 6.1 | 712 | 1115 | 85.14 | 17.02 | 73.27 | 33.15 | 42.70 | 148.09 | 1.19 | 39.78 | 269.00 | −32.5 | −4.52 |

| P6 | Baboucar | 30.4 | 7.0 | 133 | 175 | 19.17 | 1.59 | 15.69 | 1.66 | 73.20 | 14.39 | <LOD | 1.62 | 5.53 | −31.7 | −4.1 |

| P7 | Ndangane 1 | 29.7 | 6.7 | 170 | 282 | 11.54 | 1.46 | 34.95 | 1.87 | 54.90 | 42.43 | <LOD | 2.11 | 20.57 | - | - |

| P8 | Ndangane 2 | 29 | 8.1 | 14,734 | 25,200 | 276.57 | 494.96 | 4472.00 | 209.70 | 439.20 | 8184.25 | 27.49 | 557.00 | 11.51 | −24.2 | −2.27 |

| P9 | Ndangane camp | 30.1 | 4.9 | 1617 | 2600 | 95.13 | 13.64 | 452.20 | 22.85 | 24.40 | 670.79 | 2.65 | 38.48 | 291.10 | −31.7 | −4.31 |

| P10 | Djilor | 33.6 | 5.6 | 80 | 107 | 5.76 | 0.85 | 15.12 | 1.39 | 18.30 | 19.50 | <LOD | 1.40 | 17.12 | - | - |

| P11 | Simal | 30.7 | 6.6 | 497 | 850 | 28.69 | 10.88 | 121.80 | 10.85 | 61.00 | 202.49 | 0.79 | 32.52 | 26.57 | - | - |

| P12 | Fimela | 30 | 6.9 | 1744 | 2730 | 145.94 | 28.50 | 349.70 | 58.33 | 42.70 | 666.17 | 2.57 | 121.80 | 322.40 | −30 | −4.63 |

| P13 | Yayem | 30.8 | 6.0 | 2071 | 3120 | 125.11 | 50.61 | 331.40 | 83.16 | 30.50 | 432.89 | 2.33 | 114.40 | 883.80 | −29.5 | −4.4 |

| P14 | Fimela | 29.6 | 5.8 | 0.78 | 108 | 7.65 | 0.83 | 9.85 | 1.36 | 15.25 | 13.26 | <LOD | 0.95 | 28.44 | - | - |

| P15 | Samba Dia 3 | 30.3 | 6.1 | 858 | 1391 | 64.20 | 13.41 | 171.10 | 4.78 | 36.60 | 279.80 | 1.24 | 3.16 | 281.40 | - | - |

| P16 | Ndiédieng | 29.4 | 6.7 | 106 | 155 | 11.32 | 1.92 | 15.04 | 0.70 | 36.60 | 26.68 | <LOD | 1.23 | 12.33 | - | - |

| P17 | Samba Diallo | 29.5 | 6.2 | 545 | 880 | 42.69 | 5.37 | 128.20 | 4.51 | 45.75 | 227.40 | 0.82 | 9.79 | 78.23 | −34.3 | −5.02 |

| P18A | K.Moussa Diarra | 28.7 | 7.0 | 106 | 169 | 10.93 | 1.13 | 19.07 | 0.53 | 30.50 | 39.46 | <LOD | 1.17 | 2.86 | - | - |

| P18B | K.Moussa Diarra | 26.4 | 6.3 | 3536 | 5800 | 460.03 | 108.27 | 521.50 | 45.26 | 45.75 | 1620.42 | 6.83 | 50.56 | 668.60 | −31.8 | −4.72 |

| P19 | Soumbel | 27.4 | 6.6 | 214 | 370 | 18.53 | 3.57 | 46.91 | 2.05 | 39.65 | 75.60 | <LOD | 6.04 | 20.90 | - | - |

| P20 | Ndimbiding | 25.4 | 6.7 | 582 | 995 | 27.95 | 5.57 | 178.50 | 4.23 | 30.50 | 288.08 | 1.02 | 18.39 | 25.81 | −29.7 | −3.87 |

| P21 | Mbissel | 25 | 7.9 | 547 | 810 | 58.69 | 17.31 | 70.67 | 11.40 | 262.30 | 65.30 | 0.73 | 57.07 | 2.99 | −33.1 | −4.37 |

| P22 | Fadial | 28.1 | 7.3 | 99 | 140 | 14.71 | 1.41 | 10.59 | 1.42 | 30.50 | 22.86 | <LOD | 1.58 | 16.15 | - | - |

| P23 | Samba Dia mka | 28.8 | 7.8 | 299 | 437 | 44.14 | 2.87 | 34.35 | 0.41 | 152.50 | 42.58 | <LOD | 14.10 | 7.99 | - | - |

| P24A | Diofior D Salam | 29.5 | 7.3 | 2193 | 3740 | 336.08 | 10.81 | 417.80 | 23.92 | 161.65 | 1016.95 | 4.62 | 70.41 | 147.40 | −36 | −3.68 |

| P24B | Diofior 2 | 27.4 | 8.4 | 178 | 267 | 19.17 | 2.62 | 29.28 | 1.97 | 12.20 | 38.15 | <LOD | 7.69 | 58.91 | −31.4 | −4.21 |

| P25 | ROH | 26.1 | 7.3 | 452 | 710 | 34.52 | 8.31 | 107.90 | 1.38 | 48.80 | 167.50 | 0.69 | 17.84 | 63.90 | −31 | −3.84 |

| P26 | Djilass | 27 | 7.2 | 2684 | 4410 | 467.71 | 18.67 | 430.70 | 0.56 | 219.60 | 1368.13 | 5.49 | 97.42 | 71.62 | −31.6 | −4.58 |

| P27 | Ngarigne Jim 1 | 28.5 | 7.9 | 560 | 880 | 51.80 | 3.49 | 113.40 | 0.78 | 192.15 | 152.53 | 0.74 | 21.08 | 23.06 | ||

| P28 | Ngarigne Jim 2 | 28.4 | 7.2 | 539 | 875 | 51.87 | 5.65 | 118.90 | 4.60 | 24.40 | 224.44 | 0.85 | 8.55 | 98.43 | −31.3 | −4.56 |

| P29 | Sorobougou | 28.9 | 7.3 | 133 | 238 | 7.46 | 2.35 | 28.95 | 0.30 | 24.40 | 30.71 | <LOD | 5.73 | 32.98 | - | - |

| P30 | Mbissel jrd baob | 26.5 | 7.8 | 640 | 1007 | 39.78 | 11.80 | 139.50 | 5.82 | 170.80 | 189.20 | 0.95 | 41.63 | 38.23 | - | - |

| P31 | Ngarigne Nanoh | 32.5 | 8.2 | 818 | 1124 | 49.82 | 18.11 | 136.90 | 34.95 | 359.90 | 171.53 | 1.06 | 27.87 | 16.13 | −24.9 | −2.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarr, A.; Ndoye, S.; Djanni, A.L.T.; Diedhiou, M.; Ndiaye, M.; Faye, S.; Corbau, C.S.; Gauthier, A.; Le Coustumer, P. Integrated Hydrogeochemical, Isotopic, and Geophysical Assessment of Groundwater Salinization Processes in the Samba Dia Coastal Aquifer (Senegal). Water 2025, 17, 3590. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243590

Sarr A, Ndoye S, Djanni ALT, Diedhiou M, Ndiaye M, Faye S, Corbau CS, Gauthier A, Le Coustumer P. Integrated Hydrogeochemical, Isotopic, and Geophysical Assessment of Groundwater Salinization Processes in the Samba Dia Coastal Aquifer (Senegal). Water. 2025; 17(24):3590. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243590

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarr, Amadou, Seyni Ndoye, Axel L. Tcheheumeni Djanni, Mathias Diedhiou, Mapathe Ndiaye, Serigne Faye, Corinne Sabine Corbau, Arnaud Gauthier, and Philippe Le Coustumer. 2025. "Integrated Hydrogeochemical, Isotopic, and Geophysical Assessment of Groundwater Salinization Processes in the Samba Dia Coastal Aquifer (Senegal)" Water 17, no. 24: 3590. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243590

APA StyleSarr, A., Ndoye, S., Djanni, A. L. T., Diedhiou, M., Ndiaye, M., Faye, S., Corbau, C. S., Gauthier, A., & Le Coustumer, P. (2025). Integrated Hydrogeochemical, Isotopic, and Geophysical Assessment of Groundwater Salinization Processes in the Samba Dia Coastal Aquifer (Senegal). Water, 17(24), 3590. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243590