Abstract

Nonlinear water waves (NWWs) can be generated by the vertical bottom disturbance, which represents the conceptual processes of the rise of seabed rupture under seismic loads. To explore the correlation between the disturbance parameters and the wave features, a Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) model is applied, with the flow turbulence and fluid–structure interaction (FSI) being resolved by the k–ɛ model and the immersed boundary method (IBM), respectively. The free surface is tracked using the volume of fluid (VOF) method. After validating against the theoretical solutions and experimental results, the effects of disturbance duration and bulk on the wave features at the source region (the generation stage) and offshore direction (the propagation stage) are systematically discussed. The fixed maximal vertical displacement is considered, with four moving durations and five disturbance widths being simulated, resulting in four disturbance velocities and five disturbance bulks. The results indicate that the proposed RANS model can accurately create various wave patterns (including the linear, solitary, and tsunami-like waves) generated by bottom disturbances. Special attentions are paid to the tsunami-like wave. The wave evolution exhibits strong dependence on disturbance duration and width, with shorter durations triggering earlier soliton fission and longer widths accelerating phase celerity. These findings highlight the critical role of disturbance parameters in governing soliton formation and energy propagation patterns, which are vital in disaster forecasting.

1. Introduction

Nonlinear water waves (NWWs) have garnered significant attention due to their complex generation mechanisms and associated coastal hazards. They can be generated by tide or current flowing over submarine topography (e.g., Semenov and Wu [1]). Another fundamental generation mechanism is sudden bottom disturbance, which has been extensively investigated through laboratory experiments and numerical simulations (e.g., Derakhti et al. [2]; Gao et al. [3]). Among these, vertical bottom disturbances represent a canonical scenario, conceptually modeling seabed earthquakes (Synolakis & Bernard [4]; Reeve et al. [5]). Research on this mechanism has revealed that it can generate diverse and often extreme wave forms, including solitary waves, tsunami-like waves, and undular bores (e.g., Fang et al. [6]; Jing et al. [7]; Gao et al. [8,9]). A thorough understanding of the generation and evolution of such NWWs is, therefore, of considerable engineering significance for coastal hazard mitigation.

Theoretical investigations of NWWs commonly assume an inviscid and incompressible fluid. Under these assumptions, several governing equations have been derived, including the forced Korteweg–de Vries (fKdV) equation (Hammack & Segur [10]; Tinti & Bortolucci [11]; Infeld et al. [12]), the Green–Naghdi (G–N) equations (Nadiga et al. [13]; Duan et al. [14]), and the Boussinesq or generalized Boussinesq (B/g-B) equations (Madsen et al. [15]; Løvholt et al. [16]). Analytical solutions indicate that NWWs generated by bottom disturbances are influenced by both the velocity and bulk of the disturbance, findings that are corroborated numerically by Shen and Chan [17] and Jin et al. [18]. Nevertheless, the inviscid assumption inherently introduces discrepancies in wave height, phase celerity, wave form, breaking pattern, etc., which are attributable to the flow separation and energy dissipation (Whittaker et al. [19]; Jin et al. [18]; Ebrahimi & Boroomand [20]; Mi et al. [21]). These discrepancies between potential solutions and real waves (either generated from experiments or simulations by high-fidelity numerical solvers) have been widely noted (Zhang & Chwang [22]; Whittaker et al. [19]; Jin et al. [23]). In a related context, Meyla and Stepanyants [24] theoretically examined the scattering of gravity–capillary waves over a bottom step. They discovered an extra evanescent mode unique to gravity–capillary wave scattering, which is essential for satisfying the additional boundary condition at the surface introduced by capillary effects. Collectively, while existing theoretical studies provide a foundational framework for understanding NWWs, notable gaps remain between idealized models and real wave dynamics.

The real waves, inherently encompassing key fluid properties, such as viscosity, turbulence, and vorticity, are distinguished from idealized potential flow descriptions. When fluid viscosity is considered, artificial Rayleigh damping has been widely adopted in theoretical analyses (Ockendon et al. [25]; Kim et al. [26]) to partially account for viscous effects. While this approach can qualitatively represent viscous damping, determining an appropriate value for the Rayleigh damping coefficient remains challenging, as it is influenced by multiple factors such as wall roughness, surface dissipation, and fluid–structure interaction (Kim et al. [26]; Ibrahim [27]; Mao et al. [28]; Jin et al. [29,30,31]). Nevertheless, with careful calibration, the discrepancy between theoretical predictions and experimental (or simulated) waves, particularly those generated by fluid–structure interaction (FSI), can be rendered negligible. This has motivated a series of subsequent studies incorporating artificial Rayleigh damping. For example, Wang et al. [32] introduced an artificial viscosity term into the dynamic free surface boundary condition to analyze viscous effects on the hydrodynamic performance of a fixed oscillating water column wave energy converter. In a more advanced approach, Zhang et al. [33] developed a fully nonlinear sloshing model enhanced by a machine learning strategy, in which a neural network was trained to adaptively calibrate the artificial damping coefficient to evaluate the damping ratio.

Despite these advances, the capability of these artificial damping-based methods to capture truly viscous effects remains limited. To the best of our knowledge, Wu et al. [33] derived an exact solution based on the linearized Navier–Stokes equations. However, significant deviations among the theoretical results, experimental data, and high-fidelity numerical simulations (fully nonlinear potential solver and Navier–Stokes model) persist (Zhang et al. [33]; Jin and Lin [34]; Jin et al. [35,36]), underscoring the ongoing difficulty in accurately representing the effects of liquid viscosity in theoretical models.

An alternative approach for accurately exploring wave responses with realistic viscosity is through laboratory experiments. Pioneering experimental work was conducted by Hammack and Segur [10], who generated tsunami-like waves in a flume. Jamin et al. [37] performed experiments in a circular wave basin, creating nonlinear waves via vertical bottom disturbances. Slunyaev et al. [38] provided accurate reconstructions of dynamic pressure fields from surface displacement data across all tested models using experimental methods. More recently, Reeve et al. [4] validated the applicability of linear theory through 32 sets of experiments. It is important to note, however, that most experiments are conducted at relatively small scales and can be cost-prohibitive, and limited parametric flexibility also restricts the comprehensiveness of the experiments.

High-fidelity numerical modeling offers another powerful alternative. When thoroughly validated, numerical simulations are particularly suitable for investigating the fundamental nature of NWWs, as they circumvent the scale effects inherent in physical experiments. Early simulations primarily relied on depth-averaged Navier–Stokes equations, commonly referred to as shallow-water equations (SWEs) (Lee et al. [39]; Bai and Cheung [40]; Whittaker et al. [19]; Gao et al. [41]; Jin et al. [42]). For instance, Dragani [43] applied an SWE model to study long ocean wave generation in the coastal waters of Buenos Aires province, Argentina. Auclair et al. [44] employed a non-hydrostatic and non-Boussinesq model to investigate gravity wave generation, discussing the influence of bottom topography on wave formation. Nevertheless, it should be noted that these inviscid, depth-averaged models struggle to accurately capture strongly nonlinear wave dynamics, particularly in the near-field generation region (Wassim et al. [45]; Jin et al. [18]).

Because of the fast development of computational technologies, directly solving the Navier–Stokes equations with appropriate numerical methods to resolve FSI offers a rigorous approach to revealing the intrinsic behavior of realistic waves (e.g., Gao et al. [46]; Mi et al. [47]). Shen and Chan [17] developed a combined immersed boundary method (IBM) and a Navier–Stokes model to study NWWs induced by vertical motions, revealing a clear relationship between the arrival time and disturbance duration. Wang and Chan [48] proposed a RANS model to investigate wave generation mechanisms and derived explicit predictive equations for wavelength and amplitude. Xie and Du [49] implemented a tsunami generation procedure using the interFoam solver to simulate leading-depression tsunami waves and analyze their run-up behaviors. More recently, Jin et al. [18] identified the disturbance velocity as a dominant parameter governing stable wave profiles. While these studies have broadly outlined NWW generation via bottom movements, the reported wave characteristics remain scattered across parameter spaces, and a systematic portrayal of wave generation and propagation processes is still lacking.

To address the research gap, the present study investigates the characteristics of NWWs generated by vertically moving bottom disturbances using a RANS model, in which flow turbulence and FSI are resolved by the k–ε model and IBM, respectively. Wave dynamics during both generation and propagation phases are analyzed in detail. The influences of movement duration and disturbance width are examined, revealing that both parameters critically govern the arrival time of NWWs. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces the governing equations and numerical methodology; Section 3 presents benchmark tests and model validation; Section 4 discusses the features of NWWs induced by vertical disturbances; and Section 5 summarizes the key findings.

2. Governing Equations and Numerical Methodology

The OpenFOAM version proposed by Mi et al. [21] is utilized to simulate NWWs induced by upward-moving bottom disturbances with varying movement duration and disturbance bulk. The turbulence and the interaction between the fluid and structure are implemented by the k–ɛ model and IBM, respectively. The governing equations are solved using a two-step projection method for momentum conservation, and free surface dynamics are captured using the volume of fluid (VOF) technique.

2.1. Governing Equations

The fluid media are tap water and air, with densities of 998 kg/m3 and 1.0 kg/m3, respectively. Considering that the fluid and structure motions are at a low speed, it is acceptable that both fluids are assumed to be incompressible. Then, the basic governing equations of the flow motions are formulated as the continuity equation and the Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equation. The k–ɛ model is adopted to solve the turbulence. The total equations are summarized as follows:

where I and j = 1 and 2 for the two-dimensional (2D) flow. ui and p are the mean velocity and fluid pressure, respectively; ρ is the fluid density; fi is the gravitational acceleration; and μ is the kinematic viscosity. FIBM is the immersed boundary force, which represents the hydrodynamic forces exerted on the flow by the vertical bottom disturbance. stands for the Reynolds stress, which can be resolved through the two-equation models as follows:

where k and ε are the turbulent kinetic energy and the dissipation rate, respectively. μt is the turbulent viscosity, and Pk = μtS2 represents the productions due to the mean velocity shear, where S is the average strain rate tensor. σk is the Prandtl number corresponding to k, with a value of 0.7179, and σε is the Prandtl number corresponding to ε, with a value of 0.7179. Cu is a constant of 0.0845. The empirical constants C1ε and C2ε, η0 and β, are respectively set as 1.42, 1.68, 4.38, and 1.92.

2.2. Numerical Methodology

This two-step projection method can effectively uncouple the pressure from the momentum equation. This strategy transforms the coupled problem into sequential, computationally tractable steps, significantly enhancing numerical stability and efficiency. The details of this method are divided into the following two steps:

Step 1 is to first compute an intermediate velocity (denoted by ũin+1), which may not satisfy the continuity equation of Equation (1), and then Step 2 is to subsequently correct it to the final flow field via a pressure projection. Taking the divergence of Equation (7) and substituting Equation (1) yields the pressure Poisson equation (PPE) as follows:

It is noted that the hydrodynamic force (FIBM)in+1 is only non-zero at the fluid–solid interface, which can be estimated from Equation (7) as follows:

At the (n + 1)-th time step, the velocity uin+1 is unknown. To address this, a new velocity ûin+1 is introduced to replace uin+1 in Equation (9). This velocity is interpolated between the predicted fluid velocity in the interior fluid cells and the zero-velocity condition enforced on the fluid–solid interface. The forcing term is implemented as an implicit source within the momentum equation, coupled with the pressure–velocity correction procedure to maintain stability at practical time steps.

3. Benchmark Tests and Model Validation

This section presents the validation of the proposed model against established theoretical solutions and experimental and numerical data from the literature. Three benchmark cases of gravity waves are considered: linear, solitary, and tsunami-like waves.

3.1. Generation of Linear Waves

The generation of a linear wave (LW) is based on the principle of volume displacement, which assumes the crest volume above the still water depth (defined as h) equals the water confined by the wavemaker (Galvin [50]). Following this principle, a numerical underwater wavemaker is implemented to simulate an LW generated by a rectangular upthrust. The general formula can be expressed as follows in Equation (10):

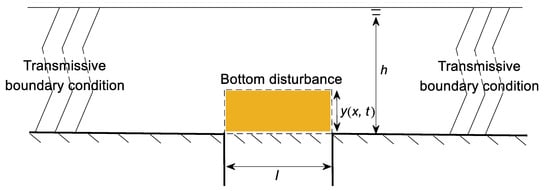

where l denotes the upthrust width, y(x,t) represents the upthrust displacement, and η(t) expresses the free surface displacement. The schematic diagram of the underwater wavemaker is shown in Figure 1. Factor 2 is used on the account that two systematic wave trains are generated on both sides. To avoid wave reflection from the left and right boundaries, the transmissive boundary condition is applied, which is as follows:

where φ denotes various wave characteristics at the boundary, including the mean velocity, the mean free surface displacement, the turbulent kinetic energy, the turbulent dissipation rate, etc. Un is the normal component of velocity at the boundary. c and L are the characteristic wave speed (equaling to (gh)0.5, where g is the gravitational acceleration) and the characteristic length scale (set as the wavelength in the present study), respectively.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of an underwater wavemaker.

To excite a linear wave whose free surface displacement satisfies η(x,t) = H/2 sin(2π/T × t), where H and T denote the wave height and wave period, respectively, a prescribed bottom upthrust motion y(x,t) is applied. To minimize startup transients, the displacement follows a smoothed trajectory given by y(x,t) = S × [1 − cos(2π/T × t)] with a corresponding velocity of 2πS/T × sin(2π/T × t), where S represents half of the stroke. A linear wave with H = 0.0068 m and T = 1.0 s is expected in a domain of h = 0.1 m. Based on the linear dispersion relationship, kh = 0.68, where k stands for the wave number, meaning an intermediate water depth. The computational domain of 50.0 m × 0.115 m is discretized into 2500 × 230 uniform grids with Δx = 0.02 m and Δz = 0.0005 m. Radiation boundary conditions are imposed at both sides of the domain to avoid wave reflection, and the time step is automatically adjusted to ensure numerical stability. The upthrust is a rectangular shape that is initially arranged at the middle of the domain in x axis, with l = 0.2 m, and S is estimated to be 0.01 m.

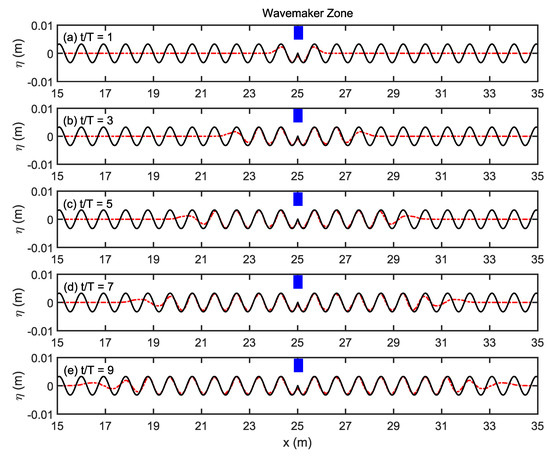

Figure 2 shows the comparisons of the free surface profiles at different instants t/T = 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 between the present numerical results and analytical wave profiles. From the figure, two successive wave trains have been generated on both sides; the leading waves at both onshore (negative x) and offshore (positive x) directions are smaller than the waves near the wavemaker zone. Excellent agreement has been guaranteed between the present numerical result and the analytical solution, implying the accuracy of the present model in modeling the LW with small amplitude, which further indicates the negligible numerical dissipation.

Figure 2.

Comparisons of the free surface profiles between the present numerical results (dash–dot line) and analytical wave profiles (solid line) at different instants: (a) t/T = 1; (b) t/T = 3; (c) t/T = 5; (d) t/T = 7; (e) t/T = 9.

3.2. Generation of Tsunami-like Waves

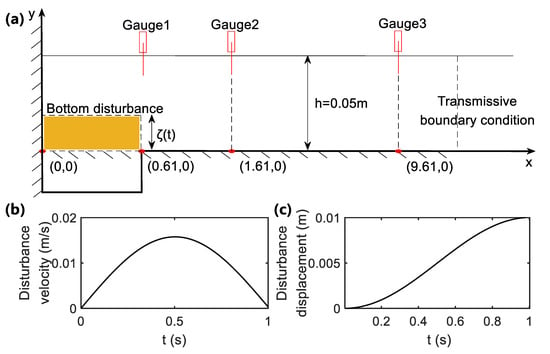

The configuration of a rectangular bottom disturbance in water of depth of h is illustrated in Figure 3a, where bup and ζ(t) are the disturbance width and displacement, respectively, and tup stands for the rise time of the disturbance. This setup replicates the seminal experiments of Hammack and Segur [10] on tsunami-like wave generation by vertical bottom motion. Shen and Chan [17] reconsidered this problem through an in-house code Navier–Stokes model, with the bottom disturbance being implemented through IBM. The schematic diagram of the experimental setup is shown in Figure 3a, where three wave gauges are installed at 0.61 m, 1.61 m, and 9.61 m away from the left boundary wall. h and bup are set as 0.05 m and 0.61 m, respectively. The disturbance motion lasts 1.0 s, with the corresponding movement velocity and disturbance displacement shown in Figure 3b,c.

Figure 3.

Generation of the tsunami-like wave: (a) schematic diagram of the fluid domain and bottom disturbance; (b) movement velocity; (c) disturbance displacement.

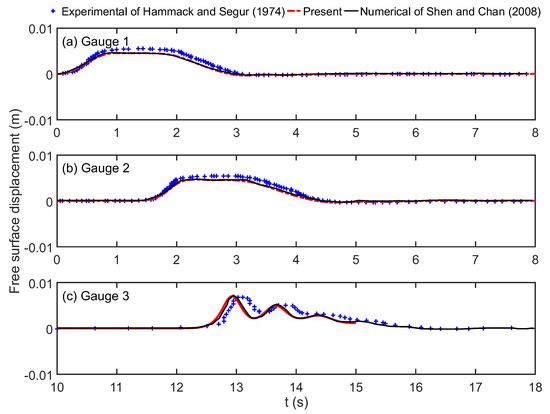

The computation domain 10.0 m × 0.06 m is discretized into 2000 × 150 uniform grids with Δx = 0.005 m and Δz = 0.0004 m. The time step is adaptively adjusted to ensure numerical stability. The free surface displacements at three wave gauges are presented in Figure 4, alongside the experimental data of Hammack and Segur [10] and the numerical results of Shen and Chan [17] for comparison. The discrepancies between the present model and that of Shen and Chan [17] are minimal, particularly in the near-field generation region, although the present model is slightly ahead of that of Shen and Chan [17] at the far region, x = 9.61 m, and overall agreement remains good. Both numerical results slightly underestimate the experimental data of Hammack and Segur [10] in the generating region, but the phase shift is unapparent, which implies good numerical conservation. In the far region, x = 9.61 m, the experimental data lag both numerical results, and this may be mainly due to accumulative errors in the numerical simulations.

Figure 4.

Comparisons of time series free surface displacements among the present numerical result (dash–dot line), numerical result of Shen and Chan [17] (solid line), and experimental data of Hammack and Segur [10] (plus) at three gauges: (a) Gauge 1; (b) Gauge 2; (c) Gauge 3.

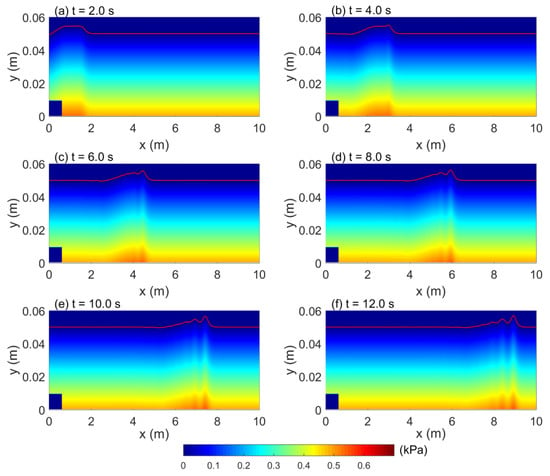

Figure 5 illustrates the free surface profiles and corresponding pressure distributions at successive instants: t = 2.0 s, 4.0 s, 6.0 s, 8.0 s, 10.0 s, and 12.0 s. After the initial 1.0 s, gravity is the only restoring force without other disturbances. By t = 2.0 s, there exists a bulk of water proceeding offshore (positive x). Subsequently, the leading bulk undergoes fission under gravitational effects, gradually splitting into successive soliton trains in the leading crest, behaving like a dispersive wave, which is also called the tsunami-like wave (Jing et al. [51]). The water in the generating zone restores calm promptly after the wave leaves the generating region, as reflected by the hydrostatic pressure distribution observed in the later stages.

Figure 5.

Free surface snapshots and pressure distributions at different instants: (a) t = 2.0 s; (b) t = 4.0 s; (c) t = 6.0 s; (d) t = 8.0 s; (e) t = 10.0 s; (f) t = 12.0 s.

4. Effects of Bottom Disturbance on Wave Features

Tsunami-like waves represent a common manifestation of seabed deformation during marine earthquakes. Seismic loading can trigger parts of the seabed to move vertically, which also represents the conceptual process of seabed upthrust, serving as a key generation mechanism for such waves. Studies have identified that both the movement velocity and disturbance bulk (or width) dominate the generated wave (Derakhti et al. [2]; Shen and Chan [17]). Building on the validation in Section 3.2, this part extends the investigation to NWWs generated by an upward-moving bottom disturbance.

4.1. Disturbance Settings

The field investigation and numerical simulation have revealed that the arrival time of the tsunami and tsunami-like wave is strongly dependent on the total duration of the seabed movement (Derakhti et al. [2]; Shen and Chan [17]), which is correlated to the movement velocity. Additionally, the disturbance bulk is another dominant parameter (Hammack and Segur [10]; Wu [52]). The larger bulk means more water is prone to move under the influence of seabed disturbance. To systematically investigate these effects, the following two sub-sections examine the influences of the two parameters on the generated waves.

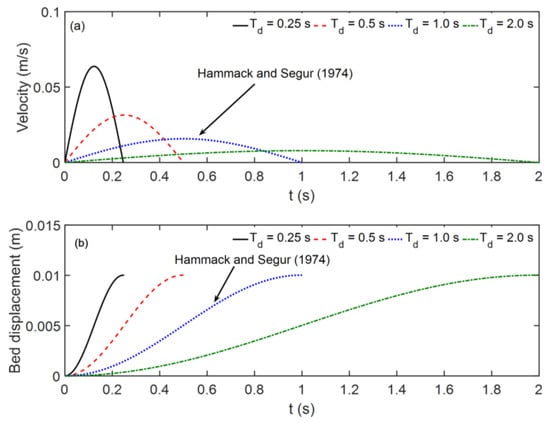

In the subsequent simulations, a fixed disturbance displacement of 0.01 m with four disturbance durations is adopted, with whom velocity and displacement are displayed in Figure 6. The two solid lines in the figure denote the benchmark case discussed in Section 3.2. In addition, five disturbance widths are simulated and presented in Section 4.3. In total, twenty numerical cases are modeled to comprehensively elucidate the role of disturbance velocity and bulk in governing wave characteristics.

Figure 6.

Time series movements of a bottom disturbance: (a) velocity; (b) displacement [10].

4.2. Influence of Disturbance Velocity

To evaluate the influence of disturbance velocity on wave generation, four distinct velocities are considered, as illustrated in Figure 6, among which the case of Td = 1.0 s is a reference case, which has yet to be verified. All cases share the same maximum vertical displacement, while the movement duration varies from 0.25 s to 2.0 s, resulting in maximum disturbance velocities (Umax) ranging approximately from 0.0079 m/s to 0.064 m/s.

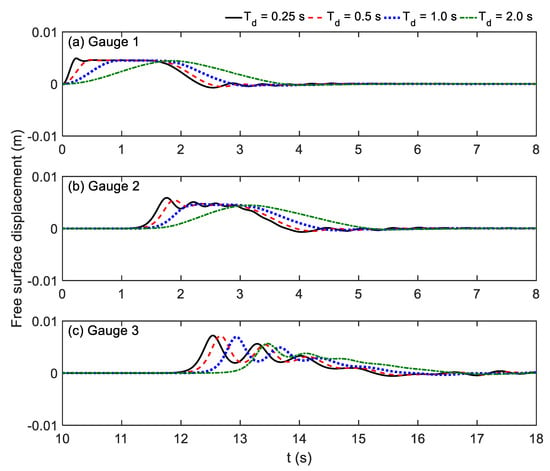

The comparisons of time series free surface displacements at Gauge 1, Gauge 2, and Gauge 3 under four disturbance velocities are displayed in Figure 7. Near the source region (Gauge 1), the surface elevation exhibits a non-isosceles trapezoidal shape in all cases, except for the longest duration (Td = 2.0 s), which retains a solitary-like profile. The peak surface elevations are consistently slightly less than half of the maximum bottom displacement, consistent with earlier studies (Hammack and Segur [10]; Shen and ChaN [17]; Wu [52]). As the wave propagates to Gauge 2 (x = 1.61 m), the leading wave begins to fission into multiple solitons in the shorter-duration cases (Td = 0.25 s and 0.5 s), accompanied by an amplitude increase relative to Gauge 1. The case of Td = 1.0 s maintains a trapezoidal form, while that of Td = 2.0 s continues to show a solitary-like profile with little change in wave height from Gauge 1.

Figure 7.

Comparisons of time series free surface displacements among various Td = 0.25 s, 0.5 s, 1.0 s, and 2.0 s at three gauges: (a) Gauge 1; (b) Gauge 2; (c) Gauge 3.

At the far-field Gauge 3, clear soliton trains are observed in all cases, confirming the eventual formation of a tsunami-like wave. The amplitude of the leading soliton is higher than that recorded at the previous gauges. Both the arrival time and amplitude of the leading soliton vary systematically with Td. Shorter disturbance durations result in earlier arrival and larger phase celerity, indicating that faster disturbance motion generates faster nonlinear waves and thus an earlier tsunami onset. The wave amplitude decreases with increasing Td. Moreover, the time intervals between the leading solitons of consecutive cases are approximately 0.13 s, 0.26 s, and 0.50 s, roughly half of the differences in disturbance duration, which highlights the critical role of movement duration in tsunami wave forecasting.

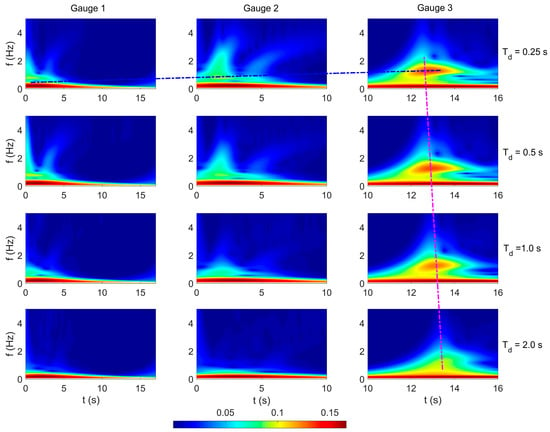

The wave energy evolutions across various gauges and under different disturbance durations are accordingly discussed, as displayed in the wavelet spectrogram results of Figure 8. The results reveal distinct spatiotemporal patterns of energy concentration in the frequency–time domain at each measurement location. As Td increases from 0.25 s to 2.0 s, a clear delay in wave energy migration is observed at Gauge 3, as marked by dashed lines in both the temporal and frequency dimensions. Specifically, for Td = 0.25 s, the dominant energy at Gauge 3 is concentrated around a relatively high frequency and early time, whereas for Td = 2.0 s, it shifts toward lower frequencies and later times. In contrast, Gauge 1 and Gauge 2 display less pronounced energy variation with Td, implying that wave energy transformation becomes most pronounced in the far field (Gauge 3) under extended disturbance durations. This spatial and parametric disparity in energy distribution underscores the strong dependence of wave energy propagation on both the measurement location and the disturbance duration. Furthermore, the results indicate that wave celerity in the generation region varies significantly with Td, a finding essential for understanding nonlinear wave dynamics.

Figure 8.

Time series wavelet spectrogram results for the corresponding free surface displacements across different wave gauges (left, middle, and right columns for Gauge 1, Gauge 2, and Gauge 3, respectively) and under varied disturbance durations (first, second, third, and fourth rows for Td = 0.25 s, 0.5 s, 1.0 s, and 2.0 s, respectively). The blue and pink dashed lines represent the trends of spatial-temporal energy transfer.

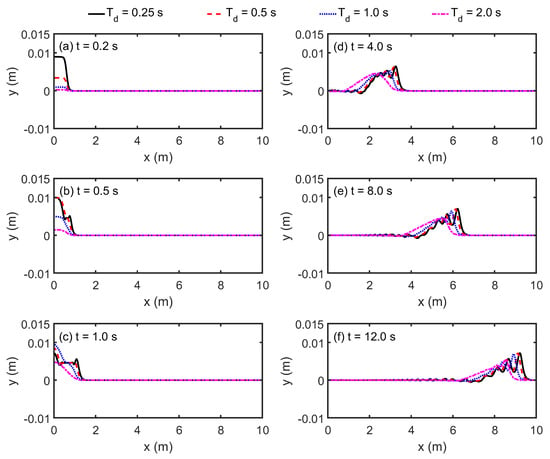

To further elucidate the wave characteristics, Figure 9 compares the free surface profiles at several instants (t = 0.2, 0.5, 1.0, 4.0, 8.0, and 12.0 s) across the four disturbance durations, with the case of Td = 1.0 s included as a reference (previously validated in Figure 4). As shown in the figures, the shortest-duration case (Td = 0.25 s) consistently exhibits the largest wave height and phase celerity of the leading crest. In all cases, the initial elevation undergoes fission, breaking up into several solitons at the wave front. Both the number of solitons and the instant at which fission initiates increase as the disturbance duration Td decreases.

Figure 9.

Comparisons of the free surface profiles among cases with various Td = 0.25 s, 0.5 s, 1.0 s (the reference case), and 2.0 s at different instants: (a) t = 0.2 s; (b) t = 0.5 s; (c) t = 1.0 s; (d) t = 4.0 s; (e) t = 8.0 s; (f) t = 12.0 s.

4.3. Influence of Disturbance Bulk

Following the analysis of a fixed bottom width Lup = 0.61 m in Section 3.2, this section examines nonlinear waves generated by disturbances with varying widths. Five different widths are considered, namely, 0.2 m, 0.4 m, 0.61 m, 0.8 m, and 1.0 m, implying a series of disturbance bulks. To emphasize nonlinear effects, the shortest disturbance duration Td = 0.25 s is selected, as it produces the most pronounced wave height and highest phase celerity (see Figure 6). Accordingly, the case with Td = 0.25 s and Lup = 0.61 m serves as the reference, which has not yet been discussed.

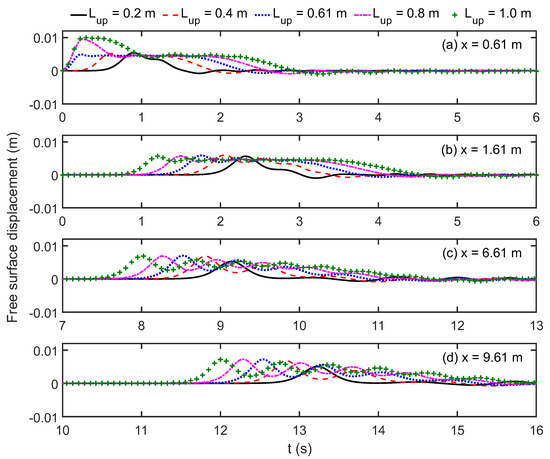

Figure 10 gives the comparisons of time series of free surface displacements at four gauges, including an additional gauge at x = 6.61 m to better capture intermediate-field behavior. Near the generation region, the maximal wave heights for the two cases with Lup = 0.8 m and Lup = 1.0 m can approach 0.01 m, whereas the remaining three cases remain below half of the maximum disturbance displacement, consistent with trends in Figure 7. As the waves pass over Gauge 2 (see Figure 10b), wave heights of the two widest disturbances with Lup = 0.8 m and Lup = 1.0 m decrease to a value comparable to the other cases. All profiles behave as the non-isosceles trapezoid, except for the case with Lup = 0.2 m, the minimal upthrust width, exhibiting an irregular solitary-like feature. In the far fields, x = 6.61 m and x = 9.61 m, well-defined soliton trains emerge for Lup ≥ 0.4 m. Among these, the case with Lup = 0.4 m shows a slightly reduced leading wave height. In contrast, the narrowest case (Lup = 0.2 m) maintains a solitary wave profile throughout propagation, particularly evident in the far field x = 9.61 m. Furthermore, the phase celerity of the leading wave grows systematically with the disturbance width Lup.

Figure 10.

Comparisons of time series of the free surface displacements among various Lup = 0.2 m, 0.4 m, 0.61 m (reference case), 0.8 m, and 1.0 m at four gauges: (a) x = 0.61 m; (b) x = 1.61 m; (c) x = 6.61 m; (d) x = 9.61 m.

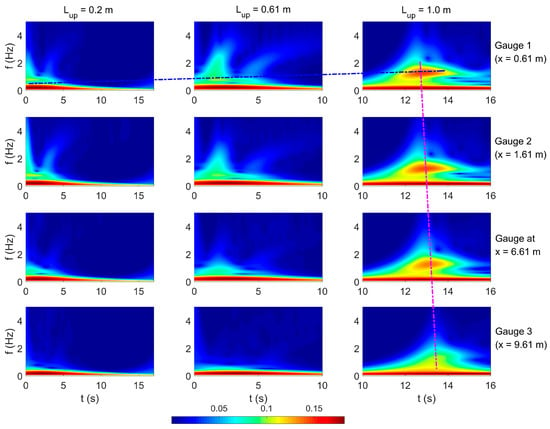

To elucidate the influence of disturbance width on wave energy evolutions across distinct spatial locations, the wavelet spectrogram results of three cases (Lup = 0.2 m, 0.61 m, 1.0 m) are selected for further discussions, as displayed in Figure 11. The energy distribution in the frequency–time domain presents remarkable spatial–temporal heterogeneity. As Lup increases from 0.2 m to 1.0 m, the wave energy migration (marked by dashed lines) at downstream gauges (especially Gauge 3) exhibits a systematic shift in both frequency and time. Specifically, for Lup = 1.0 m, the dominant energy at Gauge 3 is concentrated at relatively lower frequencies and later times compared to cases with narrower disturbance widths. In contrast, upstream gauges (Gauge 1 and Gauge 2) show less significant energy variation with Lup, indicating that the modulation of disturbance width exerts a more pronounced effect on wave energy evolution. This spatial divergence in energy dynamics across gauges and Lup values underscores the critical role of disturbance bulk in governing wave energy propagation, which is essential for advancing the understanding of the wave-bottom interaction mechanism.

Figure 11.

Time series wavelet spectrogram results for the corresponding free surface displacements across different wave gauges (first, second, third, and fourth rows, for Gauge 1, Gauge 2, gauge at x = 6.61 m, and Gauge 3, respectively) and under varied disturbance widths (left, middle, and right columns for Lup = 0.2 m, 0.61 m, and 1.0 m, respectively). The blue and pink dashed lines represent the trends of spatial-temporal energy transfer.

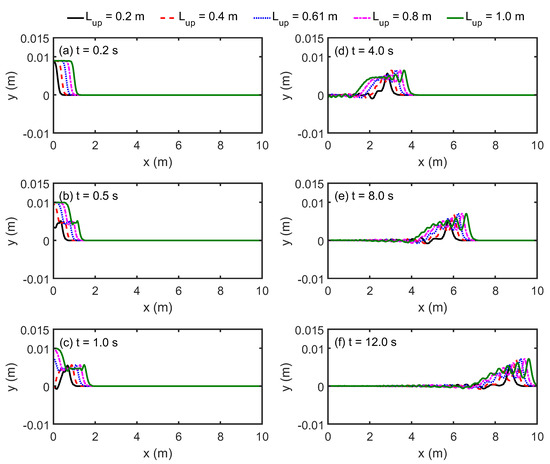

A comparison of wave characteristics among the five cases is demonstrated in Figure 12, with the case of Lup = 0.61 m serving as the reference (previously shown as the solid line in Figure 9, Td = 0.25 s and Lup = 0.61 m). The case of Lup = 1.0 m displays the largest wave height and the highest phase celerity. The comparisons also imply that the phase celerity increases with the increasing disturbance width Lup, as well as the timing of wave fission. In contrast, the narrowest disturbance case (Lup = 0.2 m) gradually develops into an irregular solitary wave, exhibiting transient spatiotemporal features of a strain of oscillating tails rather than a flat tail as the standard solitary wave, which is consistent with tsunami-like waves documented in field observations of Kawai et al. [53].

Figure 12.

Comparisons of the free surface profiles among cases with various Lup = 0.2 m, 0.4 m, 0.61 m (the reference case), 0.8 m, and 1.0 m at different instants: (a) t = 0.2 s; (b) t = 0.5 s; (c) t = 1.0 s; (d) t = 4.0 s; (e) t = 8.0 s; (f) t = 12.0 s.

5. Conclusions

This study numerically investigates the generation and propagation of nonlinear water waves (NWWs) by vertical bottom disturbances, employing a Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) solver. The model incorporates the k–ɛ model and the immersed boundary method (IBM) to represent the moving seabed disturbance, with the free surface captured by the volume of fluid (VOF) method. The model demonstrates robust accuracy in capturing the key features of resultant wave fields. The key findings are summarized as follows:

- The model demonstrates high accuracy across a defined parameter space, simulating bottom disturbances with non-dimensional velocity amplitudes () ranging from 0.113 to 0.091 and non-dimensional widths (Lup/0.61) ranging from 0.328 to 1.639, validating its capability in capturing essential wave features across a broad range of disturbance velocities and widths.

- The generated wave field exhibits strong dependence on both the disturbance duration Td and width Lup. For instance, the decrease in Td and the growth of Lup can independently lead to an increase in phase celerity and wave height of the leading soliton. All simulated cases evolve into dispersive wave trains whose leading crest undergoes fission into successive solitons, a hallmark of a tsunami-like wave.

- Shorter disturbance durations result in earlier fission of the leading crest into soliton trains and higher phase celerities. This inverse relationship between disturbance duration and wave celerity provides crucial insight for wave forecasting applications.

- Larger disturbance widths generate nonlinear waves in a near-linear increase in the phase celerity of the leading wave. The amplitude of the leading soliton decreases with increasing Td but increases with expanding Lup, revealing competing mechanisms governing wave amplitude evolution.

- Wave energy evolution demonstrates distinct spatiotemporal patterns, with the main wave energy nonlinearly migrating from higher frequencies to lower frequencies in the offshore direction (the prorogating direction) for longer disturbances. This spectral evolution underscores the critical role of both disturbance duration and width in governing wave energy propagation characteristics.

These findings substantially advance the understanding of tsunami-like wave generation mechanisms and provide valuable insights for predicting wave behaviors in scenarios involving seabed disturbances, with relevance to coastal hazard assessment and early warning systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, H.-P.M.; validation, visualization, and writing—original draft, H.-P.M. and H.-X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Doctoral research start-up fee of Panzhihua University, grant number 035200243; the Open Fund project of the State Key Laboratory of Comprehensive Utilization of Vanadium and Titanium Resources, grant number 035001648; the Laboratory for Comprehensive Development and Utilization of Industrial Solid Waste, grant number 035300420; and the School Funding of Panzhihua University, grant number 035300968.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request due to restrictions on personal privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Semenov, Y.A.; Wu, G.X. Free-surface gravity flow due to a submerged body in uniform current. J. Fluid Mech. 2020, 883, A60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derakhti, M.; Dalrymple, R.A.; Okal, E.A.; Synolakis, C.E. Temporal and topographic source effects on tsunami generation. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 5270–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.L.; Ma, X.Z.; Dong, G.H.; Chen, H.Z.; Liu, Q.; Zang, J. Investigation on the effects of Bragg reflection on harbor oscillations. Coast. Eng. 2021, 170, 103977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Synolakis, C.E.; Bernard, E.N. Tsunami science before and beyond boxing day 2004. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2006, 364, 2231–2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, D.E.; Horrillo-Caraballo, J.; Karunarathna, H.; Wang, X. Experimental study of wave trains generated by vertical bed movements. Appl. Ocean Res. 2024, 147, 103971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Liu, Z.; Sun, J.; Xie, Z.; Zheng, Z. Development and validation of a two-layer Boussinesq model for simulating free surface waves generated by bottom motion. Appl. Ocean Res. 2020, 94, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, H.; Gao, Y.; Liu, C.; Hou, J. Far-field characteristics of linear water waves generated by a submerged landslide over a flat seabed. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ji, C.; Gaidai, O.; Liu, Y.; Ma, X. Numerical investigation of transient harbor oscillations induced by N-waves. Coast. Eng. 2017, 125, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ma, X.; Chen, H.; Zang, J.; Dong, G. On hydrodynamic characteristics of transient harbor resonance excited by double solitary waves. Ocean Eng. 2021, 219, 108345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammack, J.L.; Segur, H. The Korteweg-de Vries equation and water waves. Part 2. Comparison with experiments. J. Fluid Mech. 1974, 65, 289–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinti, S.; Bortolucci, E. Energy of water waves induced by submarine landslides. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2000, 157, 281–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infeld, E.; Karczewska, A.; Rowlands, G.; Rozmej, P. Exact cnoidal solutions of the extended KdV equation. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2018, 133, 1191–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadiga, B.T.; Margolin, L.G.; Smolarkiewicz, P.K. Different approximations of shallow fluid flow over an obstacle. Phys. Fluids 1996, 8, 2066–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, B.B.; Ertekin, R.C.; Kim, J.W. Steady solution of the velocity field of steep solitary waves. Appl. Ocean Res. 2018, 73, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madsen, P.A.; Bingham, H.B.; Schäffer, H.A. Boussinesq-type formulations for fully nonlinear and extremely dispersive water waves: Derivation and analysis. Proc. R. Soc. A 2003, 459, 1075–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Løvholt, F.; Pedersen, G.; Harbitz, C.B.; Glimsdal, S.; Kim, J. On the characteristics of landslide tsunamis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2015, 373, 20140376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.W.; Chan, E.S. Numerical simulation of fluid-structure interaction using a combined volume of fluid and immersed boundary method. Ocean Eng. 2008, 35, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Qin, Y.Y.; Tao, Y.; Lin, P. Numerical modeling of transient nonlinear water waves generated by horizontally moving bottom disturbances. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 113125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, C.N.; Nokes, R.I.; Lo, H.Y.; Liu, P.F.; Davidson, M.J. Physical and numerical modelling of tsunami generation by a moving obstacle at the bottom boundary. Environ. Fluid Mech. 2017, 17, 929–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A.; Boroomand, B. Simulation of nonlinear free surface waves using a fixed grid method. J. Appl. Fluid Mech. 2023, 16, 2054–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, S.; Wang, M.; Avital, E.J.; Williams, J.J.; Chatjigeorgiou, I.K. An implicit Eulerian–Lagrangian model for flow-net interaction using immersed boundary method in OpenFOAM. Ocean Eng. 2022, 264, 112843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chwang, A.T. Numerical study of nonlinear shallow water waves produced by a submerged moving disturbance in viscous flow. Phys. Fluids 1996, 8, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Dai, C.; Huang, H.L.; Qin, Y.Y.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, F.G. A comparative study of RNN, CNN, LSTM and GRU for random sea wave forecasting. Ocean Eng. 2025, 338, 122013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meylan, M.H.; Stepanyants, Y.A. Scattering of gravity-capillary waves on a bottom step. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36, 011701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockendon, H.; Ockendon, J.R.; Waterhouse, D.D. Multi-mode resonance in fluids. J. Fluid Mech. 1996, 315, 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.W.; Koo, W.; Hong, S.Y. Numerical analysis of various artificial damping schemes in a three-dimensional numerical wave tank. Ocean Eng. 2013, 75, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.A. Recent advances in physics of fluid parametric sloshing and related problems. J. Fluids Eng. 2015, 137, 090801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.; He, Y.; Wu, G.; Lin, J.; Ji, R. Study of liquid viscosity effects on hydrodynamic forces on an oscillating circular cylinder underwater using OpenFOAM. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Liu, M.M.; Zou, Y.J.; Luo, M.; Yang, F.; Wang, L. Numerical simulation of Faraday waves in a rectangular tank and damping mechanism of internal baffles. J. Fluids Struct. 2022, 109, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Xue, M.A.; Lin, P.Z. Experimental and numerical study of nonlinear modal characteristics of Faraday waves. Ocean Eng. 2021, 221, 108554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Huang, H.L.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, F.G.; Luo, M.; Fan, C.Y.; Tang, T. A systematic review on mechanism and regulation strategy of marine hydrodynamic noise: Advances, challenges, and perspectives. Ocean Eng. 2025, 330, 121202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Ning, D.; Zhang, C.; Zou, Q.; Liu, Z. Nonlinear and viscous effects on the hydrodynamic performance of a fixed OWC wave energy converter. Coast. Eng. 2018, 131, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tan, J.; Ning, D. Machine learning strategy for viscous calibration of fully-nonlinear liquid sloshing simulation in FLNG tanks. Appl. Ocean Res. 2021, 114, 102737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.X.; Taylor, R.E.; Greaves, D.M. The effect of viscosity on the transient free surface waves in a two-dimensional tank. J. Eng. Math. 2001, 40, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Lin, P.Z. Viscous effects on liquid sloshing under external excitations. Ocean Eng. 2019, 171, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Tang, J.B.; Tang, X.C.; Mi, S.; Wu, J.X.; Liu, M.M.; Huang, Z.L. Effect of viscosity on sloshing in a rectangular tank with intermediate liquid depth. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2020, 118, 110148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamin, T.; Gordillo, L.; Ruiz-Chavarría, G.; Berhanu, M.; Falcon, E. Experiments on generation of surface waves by an underwater moving bottom. Proc. R. Soc. A 2015, 471, 20150069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slunyaev, A.V.; Kokorina, A.V.; Klein, M. Nonlinear dynamic pressure beneath waves in water of intermediate depth: Theory and experiment. Eur. J. Mech. B Fluids 2022, 94, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.J.; Skjelbreia, J.E.; Raichlen, F. Measurements of velocities in solitary waves. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean. Div. 1982, 108, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Cheung, K.F. Depth-integrated free-surface flow with a two-layer non-hydrostatic formulation. Int. J. Numer. Methods Fluids 2012, 69, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Ma, X.; Zang, J.; Dong, G.; Ma, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, L. Numerical investigation of harbor oscillations induced by focused transient wave groups. Coast. Eng. 2020, 158, 103670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Huang, H.L.; Xu, X.K.; Qin, Y.Y.; Luo, M.; Wen, Y. Assessment of offshore wind and wave energy resources for combined exploitation in the East China Sea. Energy 2025, 323, 135730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragani, W.C. Numerical experiments on the generation of long ocean waves in coastal waters of the Buenos Aires province, Argentina. Cont. Shelf Res. 2007, 27, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auclair, F.; Bordois, L.; Dossmann, Y.; Duhaut, T.; Paci, A.; Ulses, C.; Nguyen, C. A non-hydrostatic non-Boussinesq algorithm for free-surface ocean modelling. Ocean Model. 2018, 132, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassim, E.; Zheng, B.; Shang, Y. A parallel two-grid method based on finite element approximations for the 2D/3D Navier-Stokes equations with damping. Eng. Comput. 2024, 40, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Wu, Y.; Song, Z.; He, M. Influences of low velocity uniform current on characteristics of gap resonance occurring between two adjacent fixed bodies. Mar. Struct. 2026, 106, 103961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, C.; Gao, J.; Song, Z.; Liu, Y. Hydrodynamic wave forces on two side-by-side barges subjected to nonlinear focused wave groups. Ocean Eng. 2025, 317, 120056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.E.; Chan, I.C. Numerical investigation of wave generation characteristics of bottom-tilting flume wavemaker. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, P.; Du, Y. Tsunami wave generation in Navier-Stokes solver and the effect of leading trough on wave run-up. Coast. Eng. 2023, 182, 104293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvin, C.J. Wave Height Prediction for Wave Generators in Shallow Water; Technical Memorandum No. 4; U.S. Army Coastal Engineering Research Center: Duck, NC, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, H.; Chen, G.; Liu, C.; Wang, W.; Zuo, J. Dispersive effects of water waves generated by submerged landslide. Nat. Hazards 2020, 103, 1917–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.S. A modified volume-of-fluid/hybrid Cartesian immersed boundary method for simulating free-surface undulation over moving topographies. Comput. Fluids 2019, 179, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, H.; Satoh, M.; Kawaguchi, K.; Seki, K. Characteristics of the 2011 Tohoku tsunami waveform acquired around Japan by NOWPHAS equipment. Coastal. Eng. J. 2013, 55, 1350008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).