Abstract

This study evaluates the feasibility of implementing water markets and improving decision-making for irrigated agriculture in transboundary water basins. It analyzes the physical and economic potential of cooperation between institutions and users in the face of recurrent water scarcity. The research’s study case is the Conchos River basin in Chihuahua, Mexico, where agriculture accounts for 96% of the state’s water use. The basin, with its four main irrigation districts: 005 Delicias, 090 Ojinaga, 103 Florido, and 113 Alto Conchos, contributes approximately 80% of the volume committed in the 1944 International Boundary and Water Treaty between Mexico and the United States. The methodology integrates Cooperative Game Theory with Positive Mathematical Programming (PMP) in Python version 3.12 to optimize water allocation. The models consider crop coefficients, yield response to water deficit, and regulatory proposals: water transfer (75% efficiency), fodder production flexibility (10%), and saving 20% of the maximum transferable volume for the treaty. Results show that cooperation between districts allows positive gains to be maintained, even with a 50% reduction in water availability.

1. Introduction

For several years, humanity has witnessed the emergence of various extreme meteorological phenomena, including droughts and floods. Although, these phenomena are not the direct result of anthropogenic activities, droughts and floods have nonetheless exerted the greatest influence on all levels of society in relation to climate change. One of the environmental resources most appreciated by humanity is water, which, due to its implicated participation in the development of societies [1], has caused governments to put all their efforts into developing different water management techniques or strategies that allow adaptation to the growing effects of climate change, relying heavily on IPCC reports to carry them out. However, current methods have proven to be insufficient when it comes to effectively addressing this problem. In Mexico, the current climate crisis has emphasized the pressing need to develop new analysis and policy tools to identify improvements in how different government institutions can collaborate, towards a more sustainable environment [2].

Water scarcity is a phenomenon that significantly impacts various sectors of society, particularly the economic sphere. Agriculture is one of the most affected, as this activity accounts for the greatest consumptive use of both surface and underground sources, representing 76.04% of the total fresh water available for human use in Mexico [3].

In addition to water scarcity, agriculture faces a series of additional problems regarding climate vulnerability, such as political, technological, and social challenges [4]. Because water, or lack thereof, has the capability of furthering the severity of these challenges, this helps highlight the urgent need for water management tools that adopt an interdisciplinary perspective to promote cooperation among all stakeholders involved in water management decision-making.

Water scarcity has become a global imperative, forcing international river basins such as the Nile, the Aral Sea, and the Lancang–Mekong to face similar challenges that manifest themselves in geopolitical conflicts, environmental degradation, and critical water allocation dilemmas [5]. To optimize management in these contexts of restriction, it is essential to implement socio-hydrological methodologies, notably Transboundary Socio-Hydrological Modeling (TCSH). This analytical framework incorporates Game Theory to assess the complex dynamics of cooperation and antagonism, together with Bankruptcy Theory to configure equitable resource distribution designs during periods of deficit. This demonstrates that optimization tools are essential pillars for substantially improving water governance in transboundary systems [6].

A clear example of this can be found along the country’s northern border, in the Rio Grande/Bravo basin, where conflicts over water scarcity are a day-to-day issue. These conflicts are intensified by the obligations of the 1944 International Boundary and Water Treaty, which requires Mexico to deliver an average annual volume of 431,721,000 cubic meters to the United States, equivalent to approximately 2,158,605,000 cubic meters over the five-year cycles established by the 1944 Treaty [7]. The operational management of the Binational Water Treaty has evolved through the issuance of official Acts by the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC, on the US side) and the Comisión Internacional de Límites y Aguas (CILA, on the Mexican side). These Acts seek to address specific problems in the Rio Grande basin and its tributaries, such as the Conchos River. Minute 309 (2003) is a key example, as it formally recognized the water savings achieved by modernizing irrigation districts in the Conchos basin and established measures to transfer that volume to the Rio Grande [8]. Similarly, Minute 325 (2020) incorporated provisions aimed at ensuring water supply without deficits and included the facilitation of humanitarian assistance from the United States to Mexico [9]. Despite these mechanisms, tensions persist due to fragmented communication between government institutions and civil society, as well as constant pressure from the U.S. government regarding deficits in delivery volumes [6].

Among the events that have generated significant disasters in this region in recent years are the political crisis in the state of Chihuahua in 2020 due to extractions in the La Boquilla Dam [10], which resulted in confrontations between civil society and the government; the water crisis in Monterrey in 2022, which continues to generate important social problems; and the more recent political crisis between the agricultural states of Tamaulipas and Chihuahua during 2025, which stems in the vulnerability of the downstream state Tamaulipas to upstream reservoir and water allocation decisions in Chihuahua which holds the upstream dams. Tamaulipas economy, which is heavily dependent on irrigated agriculture, is directly affected by the uncertainty of the water delivery situation that is further aggravated by the problem of saline intrusion resulting from evaporation and the dissolution of geological material, the infiltration of saline groundwater, as well as discharges from irrigation drains in irrigation districts. This harms its agriculture and puts the economic stability of the area at risk due to the lack of this vital resource [11].

The management of water resources is an intricate and diverse topic. However, transboundary water management introduces an additional layer of complexity by being subject to the laws and regulations of the countries involved. Conflicts in these river basins often arise due to asymmetries or inequalities in the information available, which occur when countries sharing a transboundary basin have different levels of access to and quality of data related to the basin. In addition, conflicts can also arise from power and/or location asymmetries [12]. A notable example of these discrepancies occurred in Mexico during the last few decades, particularly between 1994 and 1997, a period known as the beginning of the “Water Debt” or “Debt of the 90s”.

This situation led to international tension when then-President Bush demanded that the Mexican government deliver the water established in the treaty. A more recent example is the so-called “water war” in 2020 between CONAGUA and farmers in the state of Chihuahua, related to the water required to comply with the international treaty. These social discrepancies have a common trigger: the lack of knowledge and cooperation between the different levels of government and civil society, which has often led to economic and human losses resulting from water conflicts in the region.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the viability of water markets (WM) as a tool for optimizing decision-making in transboundary agricultural watersheds in northern Mexico, particularly under conditions of water scarcity. Cooperation between government institutions, agricultural users, the public sector, and industry, as well as binational collaboration on water issues, is analyzed using game theory and Positive Mathematical Programming (PMP), with a special emphasis on the potential economic value of such interactions. The case study corresponds to the Conchos River basin in the state of Chihuahua, Mexico.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Area

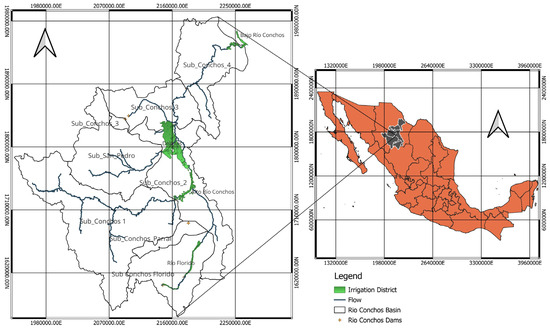

The study area of this research project is the Conchos River basin, whose main consumptive use is agriculture and contains one of the most important irrigation districts in Mexico: District 005 Delicias. Together with irrigation districts 090 Ojinaga 103 Florido and 113 Alto Conchos, it accounts for 90.91% of total water use in the state of Chihuahua. The basin originates in the pine and oak forests on the eastern slopes of the Sierra Madre Occidental in Mexico and flows into the Rio Grande near the border area of Ojinaga. Geographically, it is in the southeastern portion of the state of Chihuahua, encompassing 41 of its 67 municipalities, as well as two municipalities in the northern part of the state of Durango. The basin covers an approximate area of 74,371.79 km2 [13].

The area presents another significant geographical feature as it is in a transitional zone from the monsoonal region to the plains of the USA. The basin consists of five sub-basins identified as “High,” “Middle,” “Low,” “Río Florido,” and “Río San Pedro.” Each sub-basin exhibits a hydrological and socio-economic dynamic by its geohydrological and climatic characteristics [13].

Although CONAGUA establishes a division of 11 sub-basins for the Río Conchos, a grouping was adopted based on the study by Hernández-Romero [14]. Based on surface runoff, this author determined that certain sub-basins, such as the Chuviscar River, located in the northern region of the basin, or the three tributaries named Río Florido 1, 2, and 3, could be analyzed together. Specifically, the Chuviscar River was unified with the Conchos River 3, and the Florido tributaries were consolidated into a single sub-basin called simply Florido. For this study, the same configuration will be adopted for the analysis of the sub-basins, as presented in Figure 1, along with the irrigation districts considered.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the Conchos River Basin.

The primary natural runoff of the basin is the Conchos River, which originates in the foothills of the Sierra Madre Occidental, receiving precipitation from the Pacific Ocean. It is supplied by a significant amount of perennial runoff during the rainy season and, for most of the year, by three tributaries: the Florido River, the San Pedro River, and the Chuvíscar River. The basin has experienced water stress in recent years due to increased demand from the agricultural, domestic, and industrial sectors, a situation exacerbated by the occurrence of drought events [15].

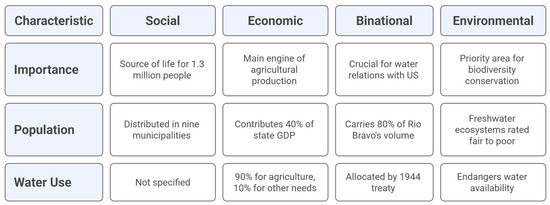

The relevance of the Conchos River watershed has been extensively documented by entities such as the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (SEMARNAT), the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), and the Texas Center for Policy Studies. This significance can be understood through four key aspects, which are illustrated in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Importance of the Conchos River Basin. Author’s own elaboration using data from [13,15,16,17], (elaborated using Napkin.ai [16]).

As illustrated in Figure 2, the Conchos River basin is fundamental to the state of Chihuahua due to its multifaceted relevance, which encompasses social, economic, binational, and environmental aspects. This importance is discussed in greater detail below.

- Socially, the Conchos basin provides sustenance for nearly 1.3 million inhabitants, distributed in nine of the state’s most populated municipalities, including Chihuahua, Delicias, Hidalgo del Parral, Camargo, Jiménez and Ojinaga [17].

- Economically, the Conchos River is a key agricultural engine for the region. Its four main irrigation districts (005 Delicias, 090 Ojinaga, 103 Florido and 113 Alto Conchos) contribute approximately 40% of the state’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) [10]. Moreover, about 90% of its surface water is used for agriculture, while the remaining 10% covers public-urban, industrial, livestock, and electricity generation need [18].

- Binationally, the Conchos River is crucial to the enforcement of the 1944 International Boundary and Water Treaty between Mexico and the United States. Although the treaty refers to the Rio Grande/Grande basin, it allocates the water of six major tributaries to the Conchos River [19], with the Conchos being the most important, transporting nearly 80% of the volume of the Río Bravo from its confluence at the Ojinaga-Presidio border [17]. This makes it a pillar of international water relations between Mexico and the United States.

- Finally, from an environmental perspective, the upper Conchos watershed is considered by the WWF-Carlos Slim Foundation Alliance as one of the 18 priority areas for Mexico’s Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Development Strategy [18]. However, the ecological functionality of its freshwater ecosystems has deteriorated over time from a previous classification of “fair” to the current rating “very poor”, threatening the availability of water and the conservation of its ecosystems [17].

2.2. Data Sources and Key Parameters

The key parameters of the study and its data sources are detailed in Table 1 for greater methodological clarity.

Table 1.

Key parameters of the study.

2.3. Crop Selection and Base Year

To begin to understand the key aspects of the water problems in the study area, as well as their relationships with other problems in the country, both locally and internationally, a systematic review of historical reports was carried out. This review considered both technical and social aspects, which have been particularly important in recent decades. To conduct this analysis, official sources, such as agricultural statistics of irrigation districts published by CONAGUA, records of social problems documented by civil and governmental organizations, and the minutes of the International Boundary and Water Commission between Mexico and the United States (CILA) were consulted.

Based on this review, the year 2020 (agricultural cycle 2019–2020) was identified as one of the most critical periods observed in recent decades. Its significance lies in the convergence of factors: the region experienced one of the most severe droughts in its history, which, combined with social conflicts over water allocated under international treaties, created a scenario of extreme tension. This combination of hydrological and social conditions made 2020 an ideal and representative case study for the objectives of this research.

With the year 2020 established as the base year, we proceeded to analyze the cultivated area and the profits generated by each crop within the irrigation districts [005, 090, 103, and 113]. This process was carried out by applying the criteria of area representation and marginal profit generation. Crops representing at least 96% of cultivated area, marginal gains were considered; for the Alto Conchos 113 irrigation district, given its specific characteristics and production history, crops representing ~95% of total profits were used.

Table 2 details the selected crops and their percentage contribution to the total cultivated area in the base year, a cycle for each of the irrigation districts mentioned above.

Table 2.

Crop selection by irrigation district (based on Estadísticas Agrícolas de los Distritos de Riego [20]).

2.4. Water Demand

The methodology used to calculate the water demand in each of the irrigation districts, which was determined in correspondence with the previously selected crops, is presented below.

2.4.1. Irrigation Depth

The precise estimation of irrigation depth for each of the crops represented becomes an imperative need in this study. Due to the lack of official information, the Crop Coefficient methodology, published by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), has been used [21]. This methodology is based on the Penman-Monteith equation to calculate the reference evapotranspiration , and allows for estimating the real crop evapotranspiration in a simple way by applying the crop coefficient , as shown in the following Equation (1):

where

- = Crop evapotranspiration, expressed in

- = Crop coefficient.

- = Reference crop evapotranspiration, in

2.4.2. Reference Evapotranspiration

This research utilized the ClimateEngine.org service, an online platform developed by the University of Idaho, in collaboration with Google Earth Engine, NOAA, and other institutions to obtain reference evapotranspiration data. This resource allows users to view, analyze, and download climate and environmental data derived from remote sensors and climate models. One of its most notable uses is the calculation and monitoring of evapotranspiration data from NASA’s MODIS mission.

2.4.3. Crop Growth Coefficient

is the crop coefficient, which varies throughout the growing cycle of each of the crops in the selected irrigation districts. This variation reflects their changes in its vegetative state and is represented by a crop coefficient curve based on three key values: initial (Kc In), mid-season (Kc med) and final (Kc fin) [21].

These crop growth coefficient values integrate the combined effects of transpiration and evaporation, assuming ideal conditions: crops that are in optimal development, well-managed, and not stressed by water deficit. However, they may require adjustments according to climate (relative humidity, wind speed), crop type (height, cover, leaf structure), planting density and frequency of soil wetting, number of irrigation cycles, and other losses [21].

These values are presented in Table 3, corresponding to each of the irrigation districts analyzed in the Conchos River basin.

Table 3.

KC Values for each irrigation district (based on FAO Table 12 [21]).

2.4.4. Applied Water

Once the evapotranspiration of each crop in the irrigation districts had been calculated using the Penman-Monteith equation, the application efficiency of each irrigation method was analyzed. This analysis was based on data and recommendations published by the Secretariat of Agriculture and Rural Development (SADER) in 2022. The efficiencies used were 60% for gravity irrigation, 90% for drip irrigation, and 75% for sprinkler irrigation [22].

The information collected from the Trust Funds Instituted in Relation to Agriculture (FIRA’s) Agrocost portal, concerning the irrigation systems used in each type of crop, was the basis for quantifying the water applied in each of the four irrigation districts analyzed. The estimation was carried out according to Equation (2):

where

- Applied Water.

- = Crop Evapotranspiration.

- = Efficiency of irrigation methods used for each crop.

On this basis, the water demand (D) for each of the irrigation districts was calculated, using the volume of water applied as an input, Equation (3):

Subsequently, the calculated demand was compared with the volume of water distributed in the selected base year, revealing a discrepancy. To mitigate this discrepancy and achieve system calibration, an adjustment in the irrigation sheets was implemented, proportional to the variation observed in the volumes.

2.5. Positive Mathematical Programming

Positive mathematical programming (PMP) consists of a three-step procedure in which a nonlinear cost function is calibrated [23]. In the basic formula, the first step is linear programming that provides marginal values (Lagrange multipliers) associated with water and land constraints only, which are used in the second step to estimate the parameters of a nonlinear cost function and a production function. In the third step, the calibrated production and cost functions are used in a nonlinear optimization program. The solution to this nonlinear program calibrates the observed values of the inputs and outputs of production [24]. The model integrates three fundamental Steps for the analysis, which are detailed below:

- Step 1 Linear Programming (LP): The objective is to maximize profits in agricultural production. The distinctive feature of this phase is the so-called “calibration constraints.” These will force the model in this first instance to replicate exactly the observed crop areas and land allocation decisions of the selected base year. This ensures that the model calibrates its initial parameters based on actual behavior [25]. The profit maximization objective function for this instance is reflected in the following Equation (4):

- Irrigated area [Decision Variable].

- Price of each of the selected crops.

- = Yield of each of the selected crops.

- = Production cost for each of the selected crops.

The calibration restrictions established for this first methodological impulse can be found in Equations (5)–(7):

where

- X = Planted area in the study zone (observed area).

- Water is applied for crop growth in each region.

- = Total available water by region or water under concession.

- Calibration constraint for land.

Because the results of this stage are fully known, it may appear as though this stage is not relevant compared to the following stages, but the key value of this first stage is the importance of obtaining the dual values (shadow prices) associated with the calibration constraints. These shadow prices allow us to quantify the profitability premium of the most competitive crops over marginal ones [25].

- 2.

- Step 2 Estimation of parameters α and γ: The second stage of the PMP process focuses on obtaining dual values using nonlinear cost or production functions. The objective of doing so is the mathematical construction of an increasing cost function that rationalizes the farmers’ observed production decisions, a function that the farmer can be considered to have implicitly followed as shown in Equations (8) and (9).

- 3.

- Stage 3 Nonlinear programming: The final stage of this process is the creation of a final optimization model that uses a cost/production function calculated using the parameters calculated in stage 2. This final model, with calibration, will accurately reproduce the production and use of selected base year inputs, which can be used to realistically and flexibly reproduce farmers’ responses to changes in policies and prices through the following Equation (10):

This research also proposes inter-district optimization based on the principles outlined above. This phase of joint optimization of irrigation districts follows scenarios of low water availability, using the previously selected base year. Its focus is on improving cooperation mechanisms in the basin, especially regarding compliance with the International Treaty with the United States. The formulation of this interdistrict optimization is based on the following proposed Equation (11):

Π the net benefits of the individual optimization of each irrigation district.

2.6. PMP Model in Python

Python source code was developed and adapted for each irrigation district and its different coalitions. This was implemented in the Visual Studio Code editor (VS Code, version 1.107.0, Microsoft Corporation), using Pyomo (version 6.8.0, Sandia National Laboratories) as the modeling language. Pyomo facilitates the integration of optimization solvers such as GLPK (GNU Linear Programming Kit, version 4.65) for linear problems and IPOPT (Interior Point Optimizer, version 3.11.1) for nonlinear problems. This flexibility provides total control over the process, allowing workflows to be customized and libraries such as NumPy (version 2.1.1), SciPy (version 1.16.3), and Matplotlib (version 3.10.1) to be integrated [26].

Taking advantage of the flexibility of the Pyomo environment, we developed an optimized source code. This code was designed to efficiently integrate irrigation district data, obtained directly from CONAGUA’s agricultural irrigation statistics, along with the cost and crop price values provided by FIRA’s Agrocostos portal.

The generation of this code arose as a secondary objective of the article. It seeks to integrate various modifications made to the work presented by Medellín-Azuara, Harou, and Howitt in 2010 [24]. These modifications include the response of crop yields to a water deficit or the transfer of water volumes between different districts. To adequately model these new PMP instruments, a dynamic generation was indispensable to allow their adaptation to the reality of water availability observed over the last decades, making imperative the need for a programming environment.

The source codes for each irrigation district and coalition analyzed, along with a simple tutorial on the programmed PMP functions and proposed adaptations and additional functions, are available in the GitHub repository entitled “Optimization Conchos Basin”. The link to the repository can be found at: https://github.com/MiguelSalomonVera/Optimization-Conchos-Basin-.git (accessed on 7 December 2025).

2.7. Restrictions

Positive Mathematical Programming (PMP) allows the incorporation of various constraints on limited resources, such as land and water. This ensures that models operate within the physical limits of available resources, allowing for accurate simulation of public policies. For instance, PMP can model reductions in water availability, whether due to human activities or government regulations [24]. In terms of land, the irrigation district area is restricted to the maximum allowed for each irrigation district, as established in the Mexican legislation.

To establish the water availability constraint for the PMP models, the volumes granted by CONAGUA over the last 25 years were analyzed, which allowed us to identify the minimum and maximum historical peaks reported for each of the irrigation districts analyzed [17]. Based on these volumes, and to validate game theory as an essential tool for the formulation of new public policies, the behavior of irrigation districts and their coalitions under various conditions of availability was analyzed. Beginning with a 100% availability of the volume allocated in the base year, this analysis simulated decreases in intervals of 5% until reaching a minimum of 50%.

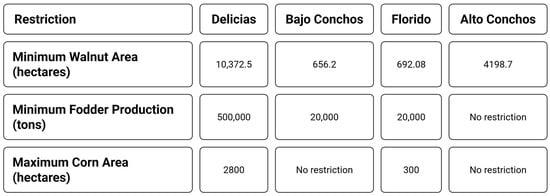

The PMP model also includes specific additional restrictions for pecan nut and fodder cultivation because of importance to the area and predominant use in the livestock industry, respectively.

To justify these restrictions and ensure that they reflect the actual behavior of farmers in the region, the historical planting patterns reported in CONAGUA statistics were analyzed. For pecan nut, the analysis revealed and atypical pattern: although reductions larger than 15% are uncommon due to land use implications and the difficulties associated with tree trimming, in extraordinary situations of water scarcity the planted area has been reduced between 23% and 45%. Therefore, these maximum variations were adopted as the limits for pecan nut area in the model.

In the case of fodders, restrictions were established by analyzing yields and crop areas over multiple years, selecting historical minimums as limits. Details on how the cropping restrictions were established for each of the four selected irrigation districts are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Restrictions for individual irrigation districts. Authors own elaboration using Napkin.ai [16].

Interregional Restrictions

With individual district restrictions in place, potential coalitions were analyzed while considering the following restrictions:

Nut and corn restrictions remain at the individual district level. However, fodder restrictions can be summed up across districts within a coalition, with 10% flexibility. Water transfers between districts were considered, assuming these occur via mixed channels with a 75% efficiency. To improve the delivery of annual water volumes to the international treaty, an additional proposal consists of limiting the transfer of available water to 80%, ensuring that the remaining 20% is kept in reserve or allocated directly to comply with the 1944 International Boundary and Water Treaty. These restrictions are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Restrictions for Irrigation District Coalitions. Author’s own elaboration using Napkin.ai [16].

2.8. Yield Response to Water Deficit (Methodological Framework)

Considering the restrictions and with the aim of enriching the PMP models, the response of crop yield to water deficit was also incorporated. This is a crucial aspect for integrated water resource management, with direct implications for the food security of societies. In addition to the timing, severity, and duration of water deficit, the species and growth stage of crops planted influence the variance of water stress effects. Therefore, in order to accurately reflect reality with the theoretical optimization models, it is essential to consider the change in yield as a function of water availability.

Equation (12) below, based on the work of FAO Book 66, represents the crop yield response to a water deficit [27].

where

- = The adjusted yield performance depending on availability.

- = The actual yield of the irrigation districts, in this case, the base year yield.

- = The sensitivity factor for each of the crops.

- = The actual evapotranspiration of the crop under these conditions.

- = The maximum evapotranspiration of the crop.

The Ky factors were obtained from FAO Book 66 [27] and are presented in Table 4 below:

Table 4.

Ky values.

Although obtaining actual crop evapotranspiration under scarcity conditions represents a significant challenge, we propose the following solution to address this limitation in Equation (13):

Once the proposal for obtaining had been implemented and the adjusted yields for each crop had been calculated, we returned to the calculation of the nonlinear model with a slight modification, as expressed below in Equation (14):

where

- = Price of each of the crops analyzed.

- = modified yield for each availability of each of the crops analyzed.

- x = observed base area.

These vectors will serve as the main input for the game theory model proposed below.

2.9. Game Theory

In this section, we develop the idea that if different districts decide to cooperate, they could increase their profits based on the fact that the versatility of crop planting given by the coalition can optimize the gains. Under the assumption that this cooperation does in fact result in increased profits, the next natural and important decision is how to divide this profit.

Game theory is a mathematical approach to understanding competition or cooperation among several parties. The two important characteristics of the game theory are non-cooperative and cooperative game theories. In this article, we will focus on cooperative game theory.

Cooperative Game Theory

Cooperative game theory is about the fair splitting of the profits. This theory involves a group of players, a set of coalitions, and a payoff distribution that assigns to each coalition the profit it obtains when the players of that coalition cooperate [28].

The idea involved in cooperative games is that, given that the players’ decision to cooperate, the total profit of the alliance must be split in a such a way that each player obtains a fair amount. This splitting is called a solution of the game.

In mathematical language, a cooperative game on is a function that assigns a real number to every subset (coalition) of N. This represents the profit of each coalition. A game is called super-additive if whenever A and B are disjoint. This means that players are willing to cooperate.

A solution of the game is a function . This represents the splitting of the profit. The solution of the game is said to be efficient if For some subset let us denote by . The core of the game is the set:

Cv = {x|x(S) ≥v(S), for everyS subset of N and x is efficient.

One way of stating that a solution is fair is that it is inside the core. This concept provides a foundation for how cooperative game theory allocates payoffs. A value is a function that assigns a solution to every game. The most important value is the Shapley value, which satisfies the properties of efficiency, symmetry, linearity, and null player.

3. Results

The results below reflect our findings throughout this study, as well as possible recommendations to improve water management in the Rio Conchos basin.

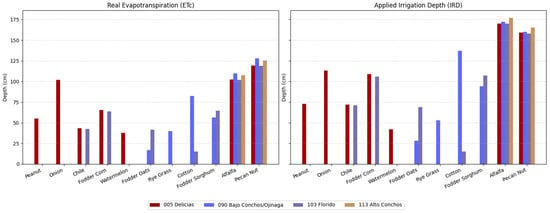

3.1. Evapotranspiration and Applied Water

Using the previously mentioned FAO crop coefficient methodology () and its corresponding equations, along with the analyzed values, we calculated the crop evapotranspiration () for each crop by irrigation district. Each calculation was adapted to the specific requirements of the crops, which depend mainly on latitude. Once the initial was calculated for each irrigation district, and additional adjustments were made to align these values with the district-level water deliveries detailed in Section 2. This process enabled us to determine the net water demand (NWD), also known as the net irrigation depth, for each crop. Figure 5 presents the resulting comparison, showing both the calculated crop evapotranspiration () and the subsequent net water demand for each crop across all analyzed irrigation districts.

Figure 5.

Evapotranspiration vs. applied irrigation depth.

A critical aspect shown in Figure 5 is the increase of up to 45% in irrigation water use in crops using conventional irrigation methods, such as fodder and cotton, when compared to their actual evapotranspiration, due to low application efficiency. This increase in consumption due to inefficiency is a key indicator for local and state governments to direct public policies and investments toward the modernization of irrigation techniques. Improving efficiency is a key strategy for addressing water scarcity conditions, which are increasingly recurrent in the area, and allows for a greater volume of water to be available for other uses and priorities, such as international commitments.

Once evapotranspiration and irrigation requirements are assessed for each crop and district, the influence of irrigation efficiency becomes evident. This highlights the relevance of adopting more efficient techniques within agricultural water management. Following this study, the procedure for calculating each of the PMP models could be initiated, as these values are a fundamental component for the beginning of the calculations.

3.2. PMP Models

After running PMP models using the Python programming language, important values for decision makers can be obtained, such as:

- Shadow prices, which provide a measure of the opportunity cost of water

- The gross value of production in each district.

- The behavior yields in response to changes in water availability.

- Production performance under different considerations

This data is crucial and will significantly help with the formulation of appropriate public policies or management plans. These results and their importance will be described below.

3.2.1. Yield Response to Water Deficit Results

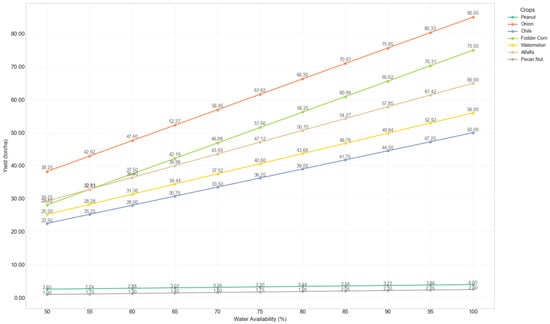

Using the 005 Delicias Irrigation District for emphasis, the behavior of crop yields in response to a variety of water availability scenarios can be seen in Figure 6:

Figure 6.

Crop yield performance in ton/ha for the Delicias irrigation district under different water-availability scenarios.

All crop yields show linear modification patterns. This is due to the linear adjustment proposed for the actual crop evapotranspiration. However, the linear behavior assumption used in this research, while facilitating multi-scenario analysis, has important implications for the results, including the potential underestimation of economic losses in crops, such as pecan nut, under extreme scarcity or the overestimation the relative benefit in fodder. Therefore, future work should focus on refining the modeling of vegetative cycles and the response to water stress using nonlinear models for a more accurate approximation. Despite this limitation, the current model arrangement provides an effective tool for decision makers to evaluate trade-offs and priorities under different levels of water availability.

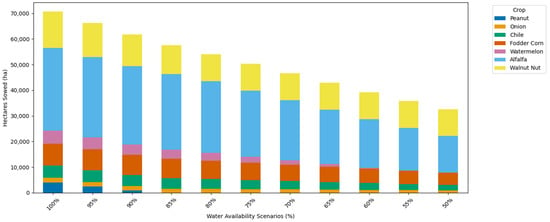

3.2.2. Crop Mix Simulation

Another result of the PMP models is related to the distribution of crops in each of the irrigation districts. Figure 7 shows, the resulting crop mix for irrigation district 005 Delicias, where we can see that even under conditions of lower water availability, the model manages to maintain the selected restrictions, especially for crops such as pecan nuts and fodder. It is vital to highlight the intrinsic value of fodder in the agricultural sector, given their high impact on the livestock industry.

Figure 7.

Crop mix for Delicias.

Furthermore, it is important to note that in order to validate these assertions, the PMP model is calibrated from its linear phase to replicate the crop allocation observed in the base year. Using calibration factors applied to individual crop areas, the model accurately reproduces the observed land distribution for the irrigation district in the base year, a scenario of 100% water availability. This replicative consistency, standard in PMP applications, supports the interpretation that the model adequately reflects the actual behavior of producers under reference conditions, ensuring that scenarios of lower water availability maintain methodological and predictive consistency with respect to the initial scenario.

These results suggest that, even in water scarcity scenarios, it is possible to meet all water needs if cooperation instruments between districts and their coalitions are prioritized.

We also obtained shadow prices of water for each region and water availability scenario. These can be defined as the monetary value assigned to a scarce resource, not traded directly in the market, which reflects the marginal increase in the objective value (profit) of having an additional unit of the scarce resource available, in this case, water. These shadow prices were obtained from the Lagrange multipliers on the water availability constraint, a standard output of the optimization routine. Shadow prices are generally higher for scarcer resources. However, constraints on lower value (fodder) communities may introduce reductions in the shadow price at intermediate levels of availability. Shadow values also represent the opportunity cost of water in other uses at the district level. In this context, shadow price quantifies the marginal profit loss associated with restricting water availability, especially within the 80–100% supply range.

The fluctuations observed in shadow prices in this study are due to different internal factors within the model, such as the crop-specific constraints. For instance, pecan nuts are a high-value crop that consume a large amount of water, whereas fodder crops, which have an intrinsic value for livestock production, are generally not financially profitable and consume significant amounts of water. These competing demands create variations in shadow prices across scenarios.

3.3. Game Theory Models

The following tables (Table 5 and Table 6) present the marginal value of the optimized payoffs using Positive Mathematical Programming (PMP) for each of the irrigation districts, under specific, predefined conditions. In these tables, PMP has been conducted for the different district combinations involved. The idea is to consider a game where the water districts are represented as players and the function v, which represents the profit, represents the marginal Value of Irrigation District Production, expressed in million USD. For each availability scenario, we define a cooperative game.

Table 5.

Marginal value of irrigation district production in million USD for high water availability scenarios.

Table 6.

Marginal value of irrigation district production in million USD for lower water availability scenarios.

Based on the evidence presented in Table 5 and Table 6, it is established that the economic impact of irrigation is intrinsically linked to the dominant crop type and its territorial extension. Pecan nuts are the main economic driver in the Delicias Irrigation District, generating the highest net profit, whose value is determined by the synergy between their high yield and the volume of water allocated. In contrast, fodder crops show a marked decrease in economic returns as water availability decreases. Despite their essential role in livestock farming, their low market value translates into a lower marginal contribution, even though they consume significant volumes of water. This duality illustrates how the constraints inherent to each crop and the severity of water scarcity jointly define the marginal profit of each irrigation district.

Likewise, the results show that interregional optimization generates positive benefits even under conditions of severe scarcity. A clear example of cooperation is the complete coalition (the four irrigation districts), which, with water availability reduced to 50%, achieves a 1.51% higher gain in comparison to an independent operation. However, this positive effect of cooperation is modulated by the agricultural composition of each district. Coalitions with a high proportion of fodder—such as those observed in the Río Florido and Bajo Conchos districts—tend to generate smaller cooperative benefits. This effect is verified in the {DEL, BC, AC} coalition, where fodder represents about 55% of the area, resulting in a marginal gain of only 0.2% above the individual scenario.

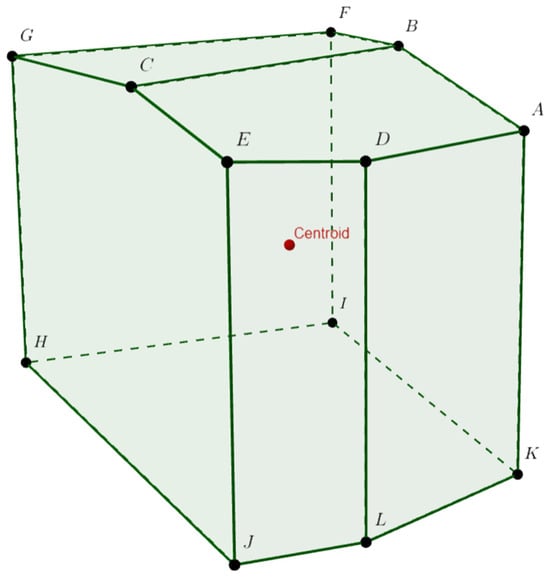

The most important aspect of this game is that this is a super-additive game, for each scenario, which can be checked by direct calculation. This means that districts are willing to cooperate. Once the game is super-additive, it is fundamental to compute the core of the game, so that a particular solution inside the core (for example, the centroid of the core) can be a fair splitting of the profit.

In this research, we compute the polyhedron that represents the core set Cv, using the SageMath interface, checking that the solution is nonempty and compact. To be illustrative, we plot the polyhedron of one scenario (90% of availability). Polyhedrons to represent the cores for the other scenarios can be computed using the same interface.

Figure 8 depicts the space of fair splitting of the total of $408.76 million USD, under the assumption of multi-district cooperation. The red point represents one of the points of the solution. A way to choose one of the solutions is to compute the centroid of the polyhedron of each scenario. This centroid is an element of the core, so it represents a solution of the game that increases the profit of each district, which is the main purpose of our approach.

Figure 8.

The polyhedron in 4 dimensions (projected to 3), that represents the solution set Cv for 90% availability. The set is delimited by the points A = (336.10, 16.72, 13.44, 42.50), B = (336.10, 16.72, 13.36, 42.58), C = (336.06, 16.76, 13.36, 42.58), D = (336.08, 16.75, 13.44, 42.50), E = (336.06, 16.76, 13.42, 42.51), F = (336.15, 16.72, 13.31, 42.58), G = (336.15, 16.76, 13.27, 42.58), H = (336.59, 16.76, 13.27, 42.13), I = (336.59, 16.72, 13.31, 42.13), J = (336.59, 16.76, 13.42, 41.98), K = (336.59, 16.75, 13.44, 41.98) and L = (336.59, 16.72, 13.44, 42.01), where each point (Del, BC, Flor, AC) is the amount in million USD given by each district. The solution Del = $336.3, BC = $16.74, Flor = $13.37, AC = $42.34 given in million USD (depicted in red) is the centroid of the polyhedron.

Table 7 shows that our approach can be used to improve the general profit of the region when cooperation is involved, and allows us to compute fair splitting between the different districts.

Table 7.

Centroid and increase % with respect to the individual profits of each district.

4. Future Research

It is advisable to incorporate additional dimensions into the water management framework, such as analysis of water quality and its possible effects on agricultural production. Although this study employs a linear representation of the relationship between water availability and yields, which is a necessary simplification in order to meet the current objectives of the model, this approach does not allow for the capture of variations associated with water quality parameters or other physical-chemical factors that also influence productivity. Although the present analysis did not explicitly model these aspects, their integration into future extensions of the PMP would allow for a more complete assessment of the constraints faced by irrigation districts under increasingly complex hydrological conditions.

Furthermore, future research should include a detailed comparative study of irrigation methods, together with an assessment of their associated pollution impacts, as both factors significantly influence agricultural water demand.

5. Conclusions

Throughout this research paper, we have explored Positive Mathematical Programming (PMP) as an effective tool for water management in regions facing water scarcity. Calibration of the model in its linear phase means that the results of the overall model, including the nonlinear model in which the 100% water availability scenario exactly replicates the observed crop distribution, provide consistent validation of the model’s ability to reflect the basic behavior of producers. Based on this validated structure, we observe that district-level applications of the PMP framework can improve decision-making and enable proper resource management, even when water availability is compromised. This is evident in our analysis, where even with relatively low water availability (50%), the model is still able to meet the specific requirements set for the study area.

In addition, these models allowed us to identify fundamental elements for the design of new public policies, such as establishing storage restrictions to secure compliance with the international treaty obligations. Likewise, with the support of Game Theory models, we were able to analyze this proposal from a mathematical point of view, finding the stability of the models through the calculation of their core and centroid.

This basis will fuel future research and allow us to analyze the flexibility of inter-institutional interactions during periods of scarcity and the feasibility of resolving conflicts, as well as the reallocation of concessions and resource allocations.

Author Contributions

M.A.S.-V.: conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, software, formal analysis, visualization (figures and codes); writing—review and editing, supervision, methodology validation, data curation (PMP analysis): J.M.-A. and B.C.-V.; investigation direction, review and editing, supervision and project administration: J.M.-A.; methodology (game theory review), formal analysis (cooperative game calculation), and visualization (polyhedron graphics): G.A.-E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A research grant from SECIHTI and UDLAP supported Miguel Angel Salomón Vera. Additional support was provided through the UNESCO Chair on Meteorological Risks, directed by Dr. Benito Corona Vasquez, which facilitated key aspects of this research. Collaboration between UDLAP and UC Merced was made possible by the UC Alianza MX Strategic Grant IRGUCMX2021-02, Water Management to Increase Climate Extreme Resilience for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Communities in the US and Mexico lead by Dr. Josué Medellín Azuara.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions derived from this research are fully documented in the body of this article. Any queries or requests for additional information should be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the instrumental role of UC Alianza MX in facilitating collaboration between the Universidad de las Américas Puebla (UDLAP) and the University of California, Merced, through academic visits and joint research activities supported by the UC Alianza MX Strategic Grant IRGUCMX2021-02. We are also deeply grateful for the leadership of both institutions for their continued support of these efforts. Likewise, the main author would like to thank the Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation (SECIHTI), for awarding the research grant. We also thank Morgan Malone for assistance with English language revision. Finally, the authors wish to honor the early contributions of Carlos Patiño Gómez, deceased, former UNESCO chair on hydrometeorological Risks, whose dedication was key to nurturing and strengthening this collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare having no competing interests.

References

- Wu, X.; He, W.; Yuan, L.; Kong, Y.; Li, R.; Qi, Y.; Yang, D.; Degefu, D.M.; Ramsey, T.S. Two-Stage Water Resources Allocation Negotiation Model for Transboundary Rivers under Scarcity. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 900854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Zhong, P.A.; Xu, B.; Zhu, F.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Comparison of Transboundary Water Resources Allocation Models Based on Game Theory and Multi-Objective Optimization. Water 2021, 13, 1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semarnat, Y.C. Atlas del Agua en México; Semarnat Conagua: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Flores, J.M.; Medellín-Azuara, J.; Valdivia-Alcalá, R.; Arana-Coronado, O.A.; García-Sánchez, R.C. Insights from a Calibrated Optimization Model for Irrigated Agriculture under Drought in an Irrigation District on the Central Mexican High Plains. Water 2019, 11, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; He, W.; Liao, Z.; Degefu, D.M.; An, M.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, X. Allocating Water in the Mekong River Basin during the Dry Season. Water 2019, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Tian, F.; Guo, L.; Borzì, I.; Patil, R.; Wei, J.; Liu, D.; Wei, Y.; Yu, D.J.; Sivapalan, M. Socio-Hydrologic Modeling of the Dynamics of Cooperation in the Transboundary Lancang-Mekong River. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 1883–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CILA. Acta 331; CILA: Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, 2024.

- CILA. Acta 309; CILA: El Paso, TX, USA, 2003.

- CILA. Acta 325; CILA: Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, 2020.

- Cuauhtémoc Osorno Córdova Red Mexicana de Cuencas—Presa La Boquilla: Los Conflictos Hídricos y La Iniciativa de La Ley General de Aguas. Available online: https://remexcu.org/index.php/blog/223-presa-la-boquilla-los-conflictos-hidricos-y-la-iniciativa-de-la-ley-general-de-aguas (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- IMCO. Aguas en México, ¿Escasez o Mala Gestión? IMCO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Teasley, R.L. Evaluating Water Resource Management in Transboundary River Basins Using Cooperative Game Theory: The Rio Grande/Bravo Basin; The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Montero Martínez, M.J.; Ibáñez Hernández, Ó.F. La Cuenca Del Río Conchos: Una Mirada Desde Las Ciencias Ante El Cambio Climático; IMTA: Jiutepec, Mexico, 2017; ISBN 9786079368890. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández Romero, P. Índice de Seguridad Hídrica En México. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de las Américas Puebla, Puebla, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Conabio Cuenca Alta del Río Conchos. Available online: http://www.conabio.gob.mx/conocimiento/regionalizacion/doctos/rhp_039.html (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- OpenAI. Available online: https://www.napkin.ai/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- World Wildlife Fund. Manejo Integral de La Cuenca Del Río Conchos; World Wildlife Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WWF-México; Fundación Carlos Slim. Río Conchos—Alto Río Bravo: Estrategia de Conservación de La Biodiversidad y El Desarrollo Sustentable; WWF-México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CILA. Acta 234; CILA: Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, 1969.

- CONAGUA. Estadísticas Agrícolas de Los Distritos de Riego. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/conagua/documentos/estadisticas-agricolas-de-los-distritos-de-riego (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- FAO. Evapotranspiración del Cultivo; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2006; Volume 56.

- Sifuentes, E.; Jaime, I.; Cervantes, M. ¿Cómo Medir La Eficiencia de Aplicación de Nuestros Riesgos? INIFAP: Mexico City, Mexico, 2022; Available online: https://vun.inifap.gob.mx/VUN_MEDIA/BibliotecaWeb/_media/_desplegableproductores/14483_5266_C%c3%b3mo_medir_la_eficiencia_de_aplicaci%c3%b3n_de_nuestros_riegos.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Howitt, R.E. Positive Mathematical Programming Following a Brief Overview of Past Ap-Proaches to Calibrating Programming Models of Farm Production and Problems Associated with These Models, the Equivalency of the Kuhn; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Medellín-Azuara, J.; Harou, J.J.; Howitt, R.E. Estimating Economic Value of Agricultural Water under Changing Conditions and the Effects of Spatial Aggregation. Sci. Total Environ. 2010, 408, 5639–5648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medellín-Azuara, J.; Howitt, R.E.; Waller-Barrera, C.; Mendoza-Espinosa, L.G.; Lund, J.R.; Taylor, J.E. A Calibrated Agricultural Water Demand Model for Three Regions in Northern Baja California un Modelo Calibrado de Demanda de Agua Para uso Agrícola Para Tres Regiones en el Norte de Baja California; SciELO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bynum, M.L.; Hackebeil, G.A.; Hart, W.E.; Laird, C.D.; Nicholson, B.L.; Siirola, J.D.; Watson, J.-P.; Woodruff, D.L. Pyomo Optimization Modeling in Python, 3rd ed.; Sandia National Lab.: Livermore, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Steduto, P.; Hsiao, T.C.; Fereres, E.; Raes, D. Crop Yield Response to Water; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012; Volume 66. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, H. Game Theory A Multi-Leveled Approach, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).