Re-Scour Below a Self-Buried Submarine Pipeline

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

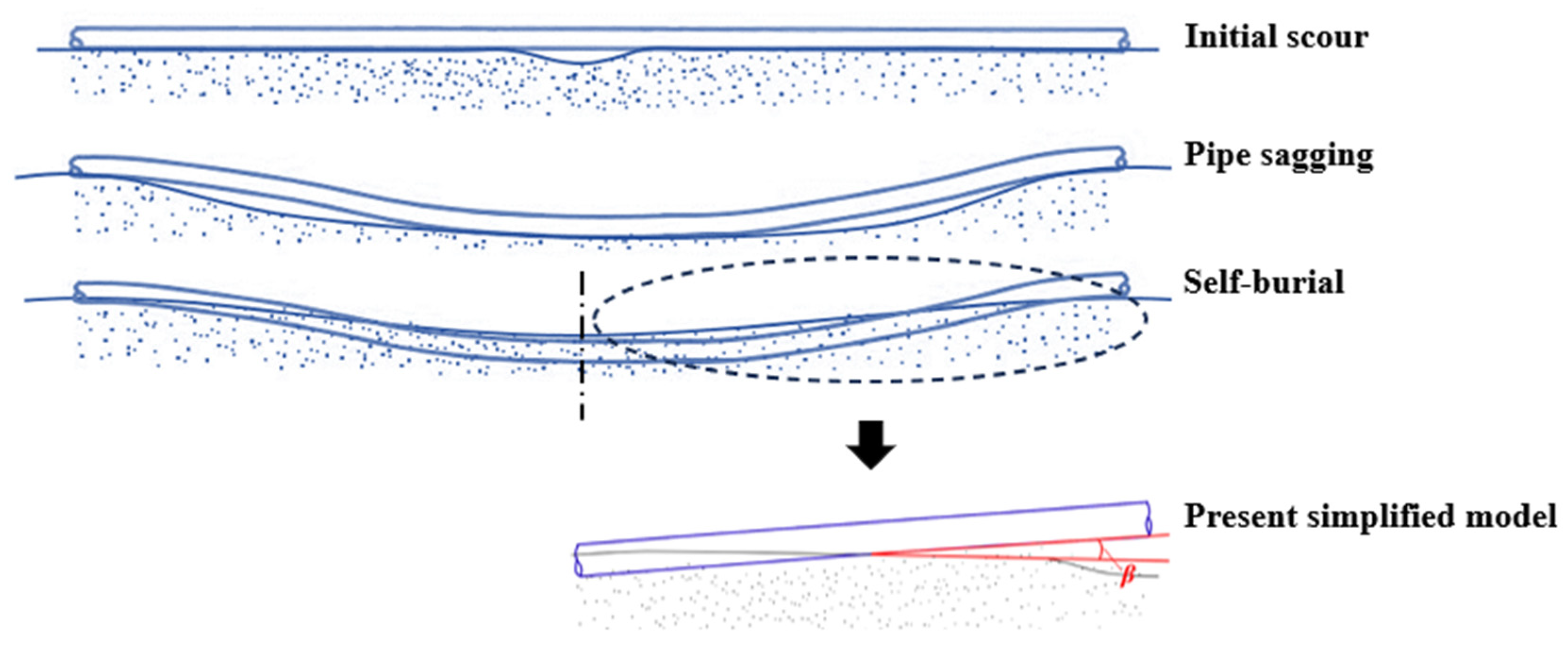

2.1. Problem Description

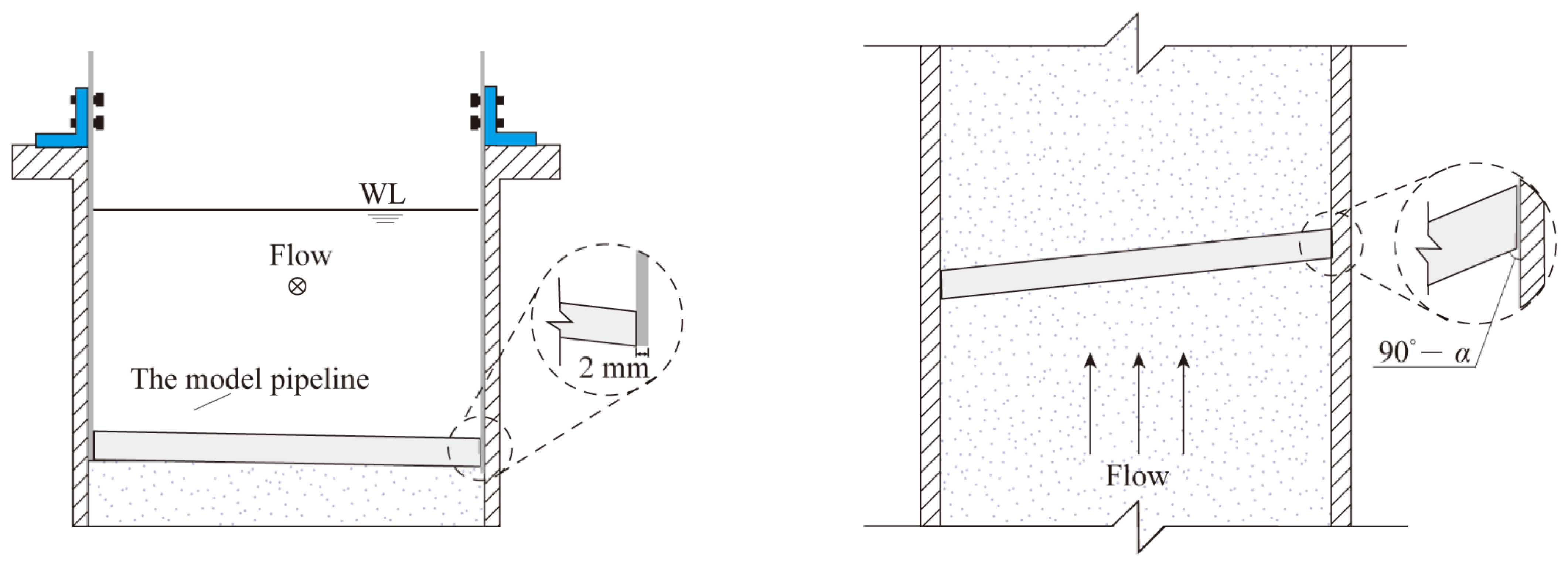

2.2. Experiment Setup

3. Results and Discussion

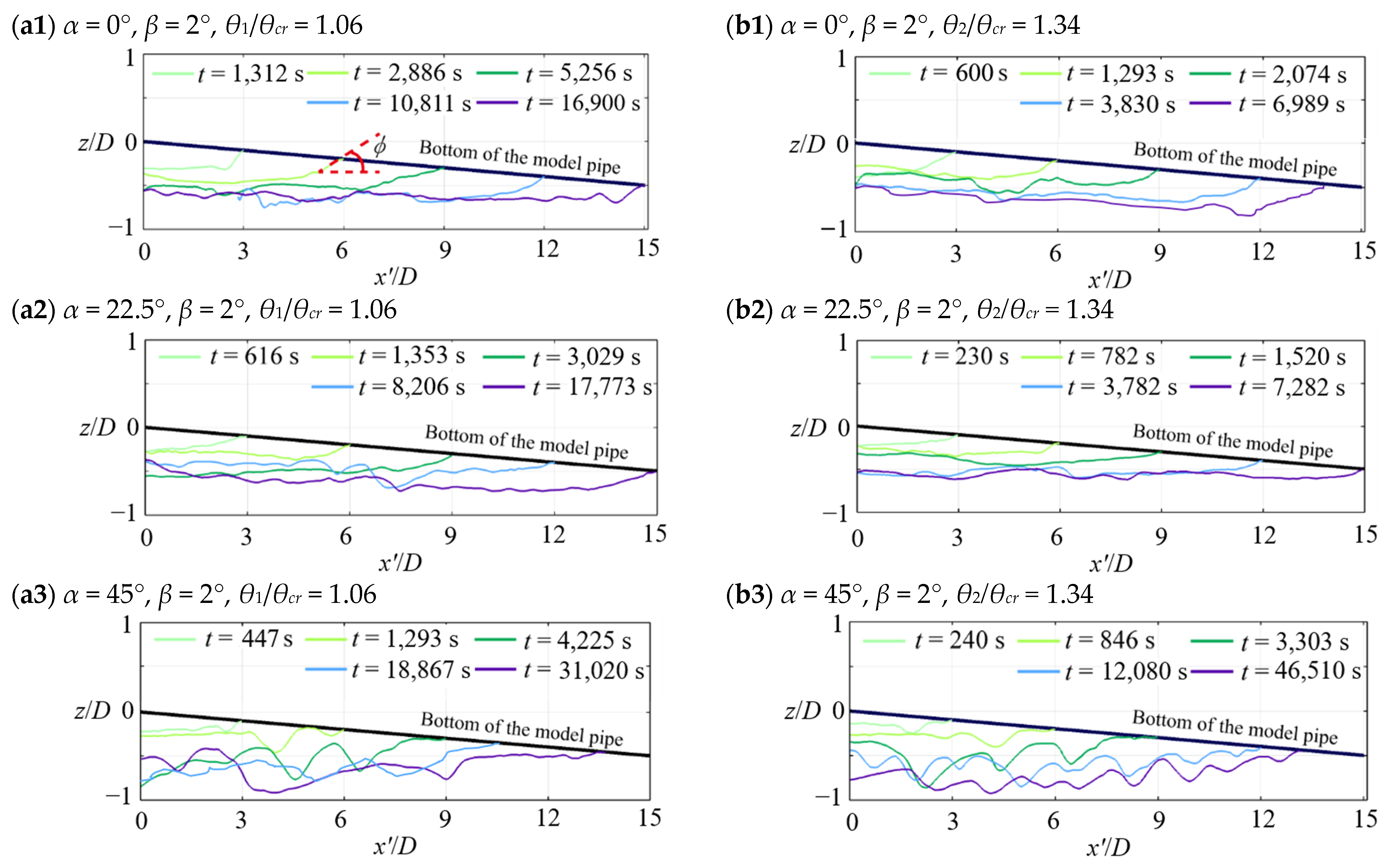

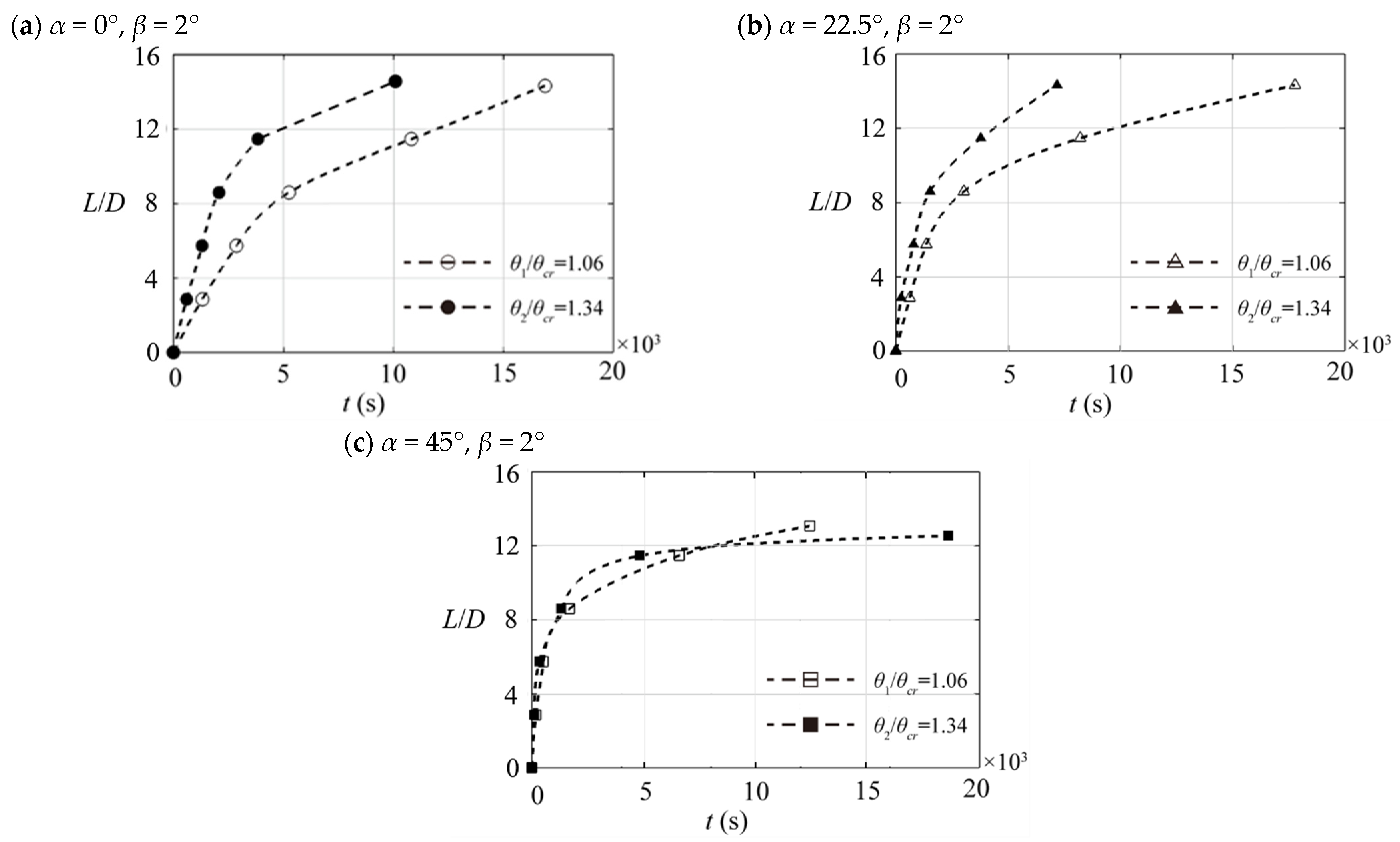

3.1. Scour Topography and Scour Depth

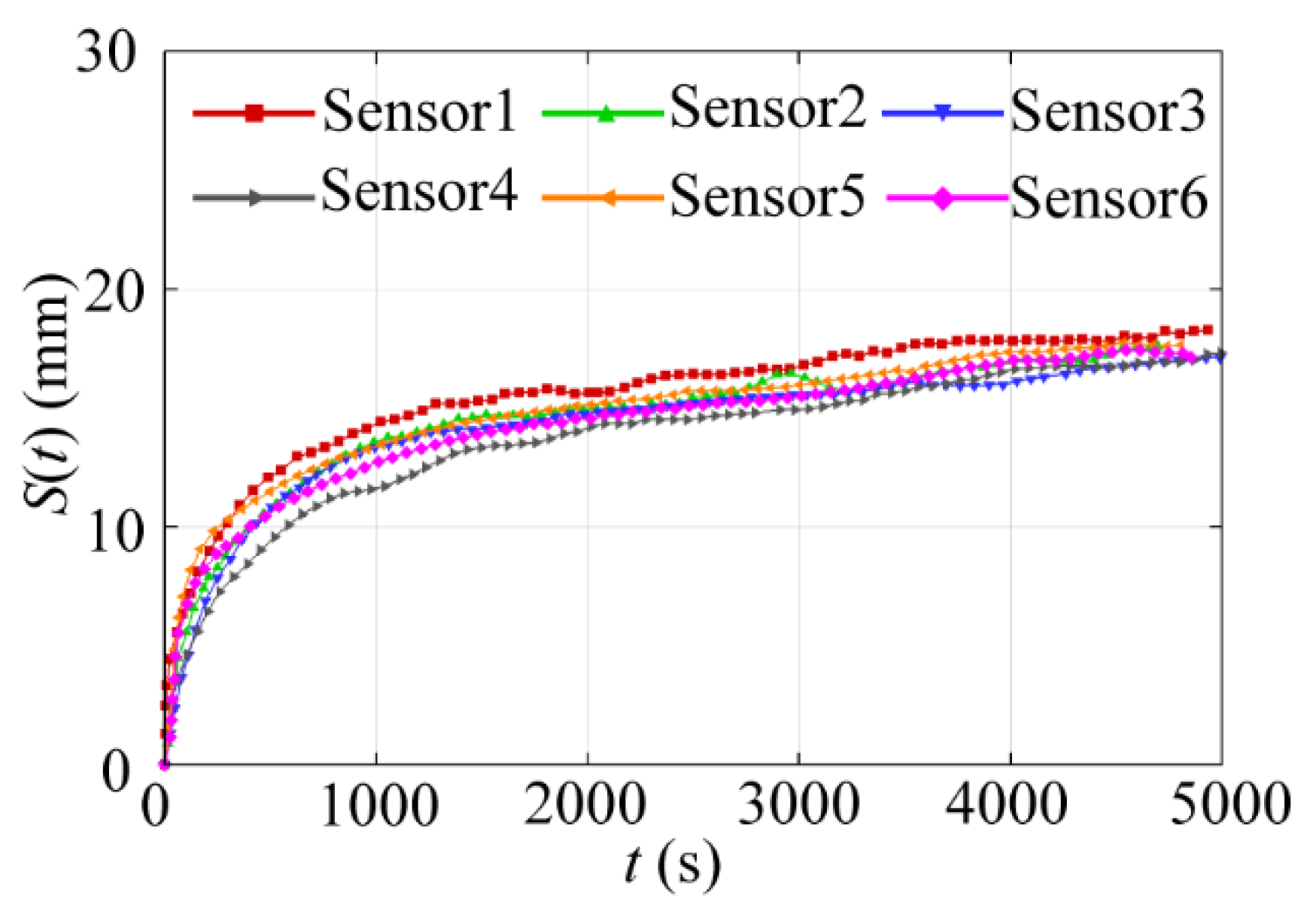

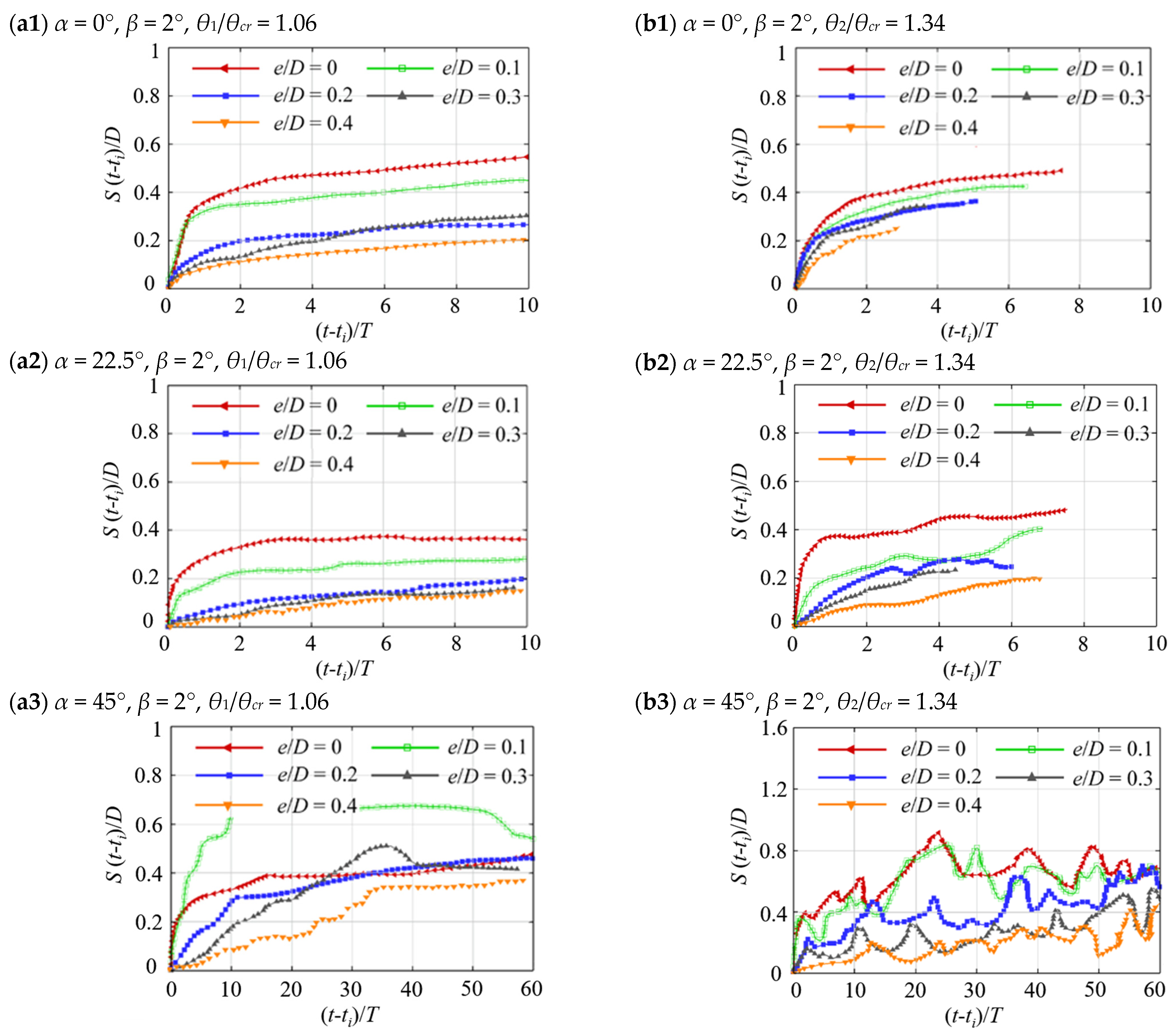

3.2. Scour Propagation Rate

- (1)

- In the rapid propagation phase, the scour propagation rate increases noticeably when α varies from 0° to 22.5° and shows no significant change when α further increases to 45°. This phenomenon can be explained by the scouring mechanism. When the flow is perpendicular to the pipeline, the flow dominates the scour process totally, causing the tunnel scouring, which is mainly responsible for scour propagation in the span shoulder region, although other spiral types of vortex caused by the three-dimensional separation in front of the pipeline may contribute to the free span expansion. When the flow has a certain angle acting on the pipeline (α ≠ 0°), the approaching flow velocity can be decomposed into the velocity component perpendicular to the pipeline and along the pipeline. The former leads to the scour propagation mainly by dominating the scour depth process, while the latter contributes to the scour propagation, similar to the horseshoe vortex in the scour around a pile discussed by [15]. As the flow incident angle α changes from 0° to 45°, the scour propagation rate increases significantly due to the combined action of the reduction of the velocity component perpendicular to the pipeline and the increase of the velocity component along the pipeline.

- (2)

- In the slow propagation phase, the scour propagation rate starts to decrease with the increase of embedment-to-diameter ratio (e/D), and reduces faster when α increases, because larger α leads to greater impact of flow structures formed downstream, causing the thicker sand ripples along the pipeline. As discussed in [9], a stable and well-developed scour shoulder is formed at the slow propagation stage, and it is less likely to be breached even by the velocity component along the pipeline. Meanwhile, the scouring tunnel effect has been significantly reduced for the inclined pipeline [15]. Therefore, both the scour length and scour rate have been found to decrease for the large flow incident angle case.

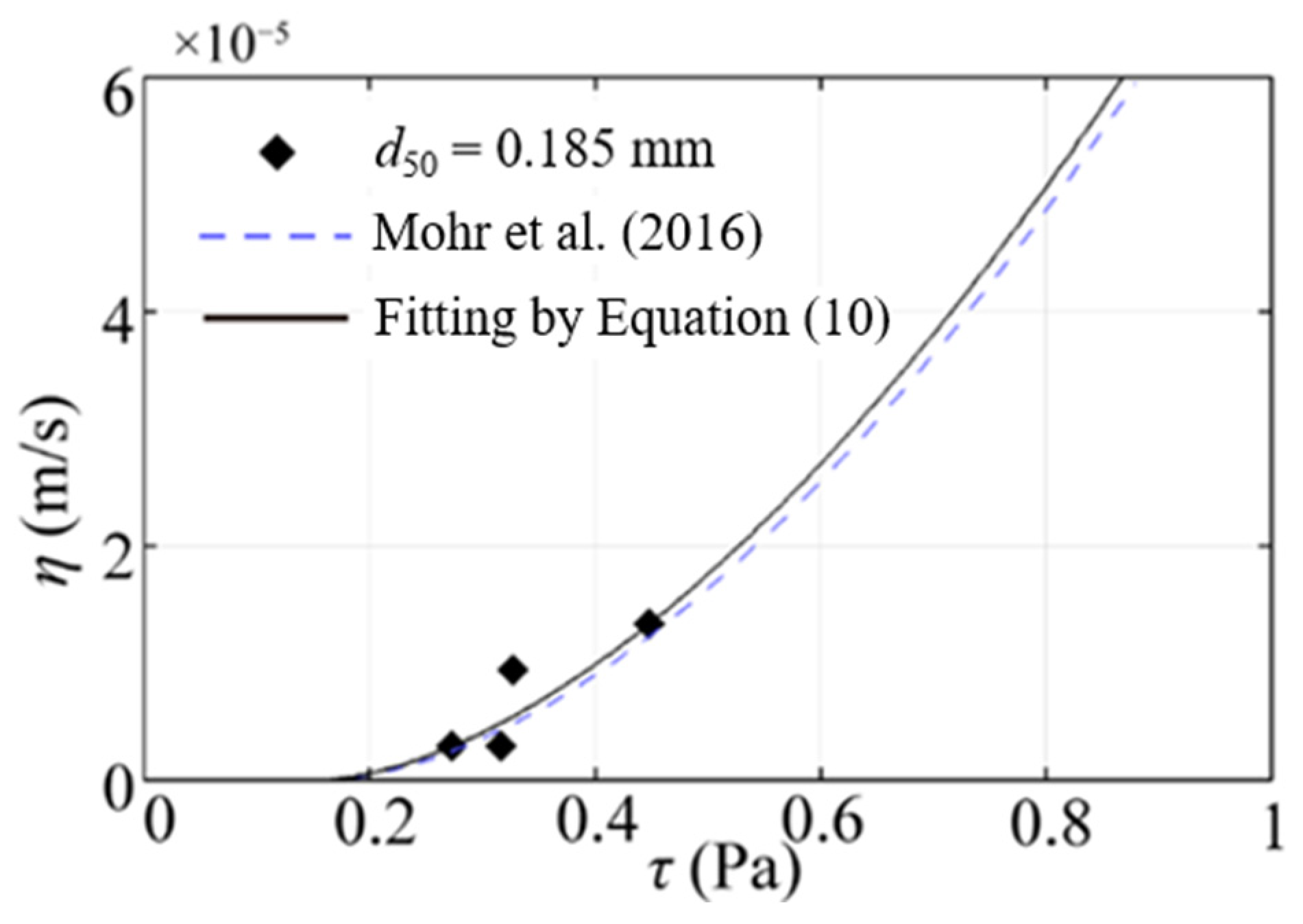

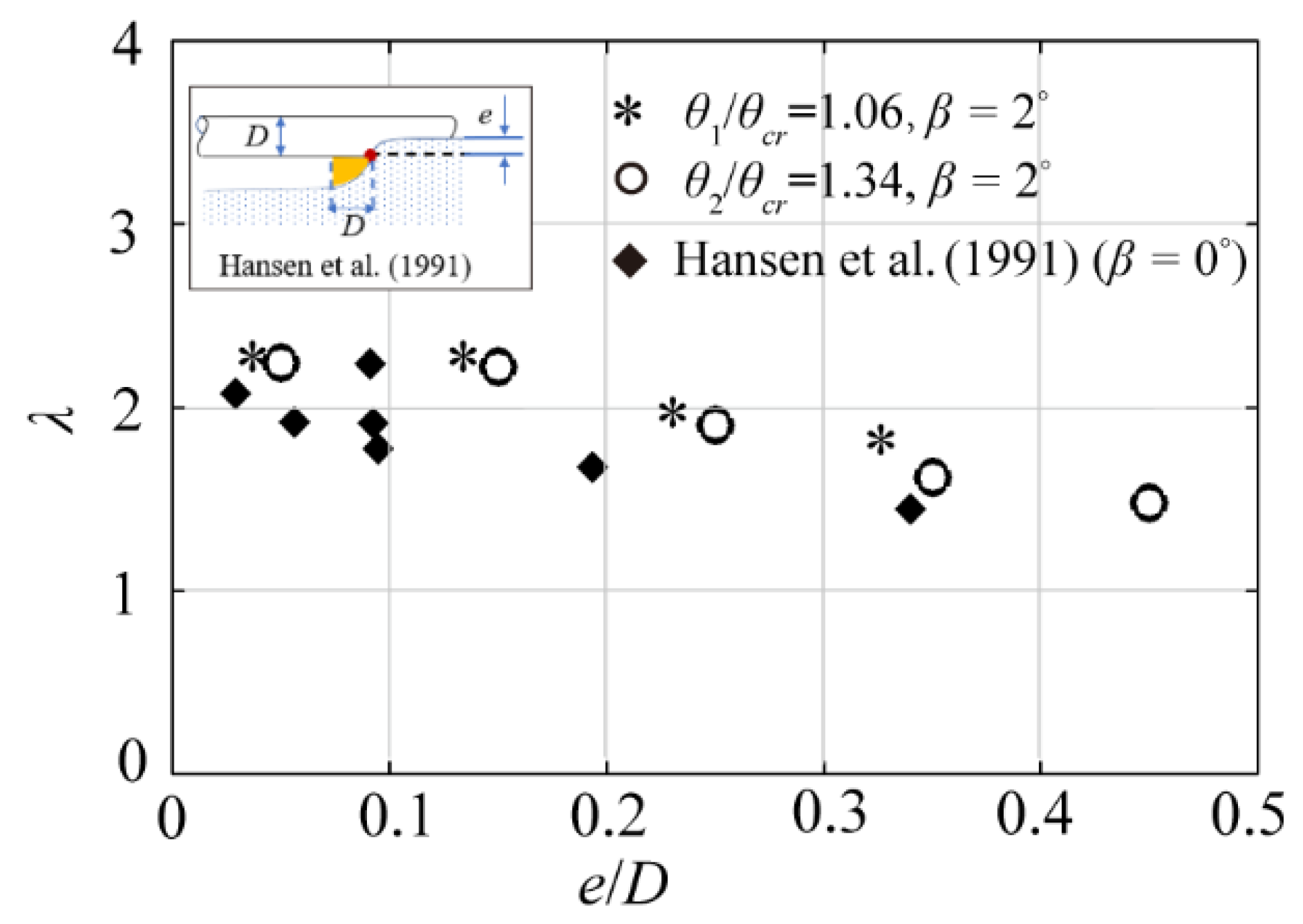

3.3. Prediction of Scour Propagation Rate

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chiew, Y. Mechanics of local scour around submarine pipelines. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1990, 116, 515−529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J. Onset of scour below a pipeline exposed to waves. Int. J. Offshore Polar Eng. 1991, 1, 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Sumer, B.M.; Truelsen, C.; Sichmann, T. Onset of scour below pipelines and self-burial. Coast. Eng. 2001, 42, 313−335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J. Scour below pipelines in waves. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 1990, 116, 307−323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredsøe, J.; Sumer, B.M.; Arnskov, M.M. Time scale for wave/current scour below pipelines. Int. J. Offshore Polar Eng. 1992, 2, 13−17. [Google Scholar]

- Fredsøe, J.; Hansen, E.A.; Mao, Y.; Sumer, B.M. Three-dimensional scour below pipelines. J. Offshore Mech. Arct. Eng. 1988, 110, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Cheng, L. Numerical model for wave-induced scour below a submarine pipeline. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2005, 131, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yeow, K.; Zang, Z. 3D scour below pipelines under waves and combined waves and currents. Coast. Eng. 2014, 83, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chiew, Y.M. Mechanics of pipeline scour propagation in the spanwise direction. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2015, 141, 04014045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajdehak, E.; Zhao, M.; Cheng, L.; Draper, S. Numerical investigation of local sour beneath a sagging subsea pipeline in steady currents. Coast. Eng. 2018, 136, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Lin, J.; Shi, Y. Incompressible Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics Simulation of Sediment Erosion around Submarine Pipelines. Water 2024, 16, 1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Zhan, B.; Jin, Y.; Tang, G. Numerical Study on the Hydrodynamic Force on Submarine Pipeline Considering the Influence of Local Scour Under Unidirectional Flow. Water 2025, 17, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernetti, R.; Bruschi, R.; Valentini, V.; Venturi, M. Pipelines placed on erodible seabeds. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Offshore Mechanics and Artic Engineering, Houston, TX, USA, 18–23 February 1990; pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.A.; Staub, C.; Fredsøe, J.; Sumer, B.M. Time-development of scour induced free spans of pipelines. In Proceedings of the 10th Offshore Mechanics and Artic Engineering Conference. Pipeline Technology, Stavanger, Norway, 23–28 June 1991; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, L.; Yeow, K.; Zhang, Z.; Teng, B. Three-dimensional scour below offshore pipelines in steady currents. Coast. Eng. 2009, 56, 577−590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chiew, Y.M. Three-dimensional scour at submarine pipelines. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2012, 138, 788−795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, H.; Drapper, S.; Cheng, L.; White, D.J. Predicting the rate of scour beneath subsea pipelines in marine sediments under steady flow conditions. Coast. Eng. 2016, 110, 111−126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, S.; Yao, W.; Cheng, L.; Tom, J.; An, H. Estimating the Rate of Scour Propagation Along a Submarine Pipeline in Time-Varying Currents and in Fine Grained Sediment. In Proceedings of the ASME 2018 37th International Conference on Ocean, Offshore and Arctic Engineering, Madrid, Spain, 17–22 June 2018; p. V005T04A019. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Meftah, M.; Mossa, M. New Approach to Predicting Local Scour Downstream of Grade-Control Structure. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2020, 146, 04019058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumer, B.M.; Fredsøe, J. Self-burial of pipelines at span shoulders. Int. J. Offshore Polar Eng. 1994, 4, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, E.A.; Klomp, W.H.G.; Smed, P.F.; Chen, Z.; Bijker, R.; Bryndum, M.B. Free Span Development and Self-Lowering of Pipelines. In Proceedings of the 14th Offshore Mechanics and Artic Engineering Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 18–22 June 1995; pp. 409–417. [Google Scholar]

- Staub, C.; Bijker, R. Dynamic numerical models for sand waves and pipeline self-burial. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Coastal Engineering, Delft, The Netherlands, 2–6 July 1990; pp. 2508–2521. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, M.; Arisoy, Y. The propagation of wave scour along the spanwise direction of submarine pipelines in case of clear-water regime. Coast. Eng. 2021, 168, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulsby, R.L.; Whitehouse, R.J.S.W. Threshold of Sediment Motion in Coastal Environments. In Proceedings of the 13th Australasian Coastal and Ocean Engineering Conference and the 6th Australasian Port and Harbour Conference, Christchurch, New Zealand, 7–11 September 1997; pp. 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Christoffersen, J.B.; Jonsson, I.G. Bed friction and dissipation in a combined current and wave motion. Ocean. Eng. 1985, 12, 387−423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sediment | Median Grain Size | Uniformity Index | Specific Gravity | Fitting Parameters for Equation (10) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| d50 (mm) | Cu | s | m | n | |

| This paper | 0.185 | 1.7 | 2.7 | 1.06 × 10−4 | 1.693 |

| [17] | 0.19 | 2 | 2.67 | 1.05 × 10−4 | 1.73 |

| Sensor No. | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| x’ (mm) | 0 | 143 | 286 | 429 | 572 | 715 |

| e (mm) | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

| e/D | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Test No. | θ/θcr | α (°) | β (°) | Scour Start | Scour Stop |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e/D | e/D | ||||

| C0 | 1.34 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| C1 | 1.06 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.5 |

| C2 | 1.34 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0.5 |

| C3 | 1.06 | 22.5 | 2 | 0 | 0.5 |

| C4 | 1.34 | 22.5 | 2 | 0 | 0.5 |

| C5 | 1.06 | 45 | 2 | 0 | 0.4 |

| C6 | 1.34 | 45 | 2 | 0 | 0.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lou, X.; Hua, Y.; Chen, L. Re-Scour Below a Self-Buried Submarine Pipeline. Water 2025, 17, 3565. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243565

Lou X, Hua Y, Chen L. Re-Scour Below a Self-Buried Submarine Pipeline. Water. 2025; 17(24):3565. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243565

Chicago/Turabian StyleLou, Xiaofan, Yulong Hua, and Lichao Chen. 2025. "Re-Scour Below a Self-Buried Submarine Pipeline" Water 17, no. 24: 3565. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243565

APA StyleLou, X., Hua, Y., & Chen, L. (2025). Re-Scour Below a Self-Buried Submarine Pipeline. Water, 17(24), 3565. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243565