Abstract

Antarctica’s pristine environment and geographical isolation make it an ideal location for conducting research on the global transport and fate of pollutants. Given its unique environmental characteristics, research on this continent is essential for identifying and characterizing the various types of pollution and understanding their transport dynamics. This study employs a comprehensive analytical approach to examine the physico-chemical and chemical characteristics of water samples collected from catchments at the Lions Rump headland, including assessments of pH, specific electrical conductivity, total organic carbon, inorganic analytes (anions, cations, metals and metalloids), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). The results showed that stream waters exhibited neutral to slightly alkaline conditions (pH 7.0–8.1) and relatively high conductivity, indicating a significant contribution of volcanic and marine inputs. TOC concentrations remained low (<2 mg L−1), while elevated levels of Cl− and SO42− reflected the strong imprint of halogen deposition. PAHs were detected at low concentrations (41.5–67.4 ng/L), with their distribution pointing to long-range atmospheric transport as the dominant source and additional evidence of re-emission from sediments. The obtained results fill gaps in knowledge about the chemical composition of water, including the levels of potentially toxic substances in areas of Antarctica that are not directly influenced by research stations.

1. Introduction

Human environmental impact is spatially heterogeneous, with intensity varying by location. Identifying pristine areas is challenging, but regions like Antarctica remain relatively untouched, serving as valuable reference sites for environmental studies and a critical location for investigating climate change impacts [1,2,3,4,5] Antarctica’s 72 designated Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs) conserve and protect unique ecosystems, including areas with notable flora and fauna, and others with historical or scenic significance, offering valuable opportunities for scientific study [6,7,8,9,10]. Antarctica’s extreme climate has isolated the region from significant human impact. However, the continent is not entirely exempt from anthropogenic influence, as pollutants are transported to the region through long-range atmospheric transport (LRAT) [5,11,12,13,14,15]. These pollutants become cold-trapped, underscoring the intricate interplay between air mass dynamics and their accumulation in this remote region [1,16,17] with the lack of information related to areas located far from the research station [12].

Lions Rump is located on King George Island, within the South Shetland Islands, which are situated in the Antarctic Peninsula region of Western Antarctica, characterized by a dynamic maritime climate and heightened sensitivity to climate change [2,7,14,18]. As detailed in [15], Lions Rump has been designated as ASPA No. 151 to protect its unique ecological values, with a primary focus on conserving its diverse marine avifauna, with penguins constituting one of the dominant and ecologically significant groups [7]. This reference site, which supports a diverse array of bird and mammal species, has been subject to minimal human impact, except for occasional monitoring of population trends and periodic investigations into geological, geomorphological, chemical, and botanical characteristics [7,19,20,21]. Lions Rump, situated on King George Island, is in a remote, far removed from major pollution sources. The Lions Rump headland is located approximately 21 km northwest of the Polish Antarctic Station Henryk Arctowski, which is the nearest permanently staffed research base. This location makes it an ideal site for studying atmospheric chemical compounds, as their composition and concentrations offer valuable insights into their origins and transport mechanisms [22,23].

Despite the initial detection of anthropogenic pollutants in Antarctica several decades ago, substantial gaps in knowledge remain, and a comprehensive understanding of their underlying patterns and dynamics is still incomplete [16,24]. Ongoing research efforts have been hindered by the challenges of conducting field studies in Antarctica, resulting in a significant deficiency of data on anthropogenic pollutants across both spatial and temporal scales [25]. The water chemistry of the ice-free regions in the Antarctic Peninsula, particularly on King George Island, is a significant knowledge gap in the field of environmental chemistry [5]. Data on the concentrations of both inorganic and organic analytes in water samples from this region are limited [1,24,25].

This study aims to investigate the water chemistry of contrasting streams on King George Island, Antarctica, to improve understanding of hydrochemical processes in small periglacial catchments and inform environmental management in polar regions. This study addresses the need to better understand hydrochemical processes in small periglacial catchments of the maritime Antarctic. The studied creeks are not subject to constant hydrological and chemical monitoring, and due to location in ASPA, the only limited research activity is permitted, excluding water bodies measurements requiring entry into the water or installation of measuring devices in water. By integrating analyses of major ions, trace elements, total organic carbon, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, we provide a comprehensive characterization of two contrasting streams draining basalts and andesites (Bystry) and volcanic–hydrothermal deposits (Lions Rump). Such a comparative approach has not previously been applied in this region. This study therefore offers new insights into the interplay of lithogenic, volcanic, and atmospheric inputs, and highlights the role of Antarctic periglacial streams as sensitive archives of both local geochemical signals and long-range transported contaminants.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area, Sample Collection and Storage

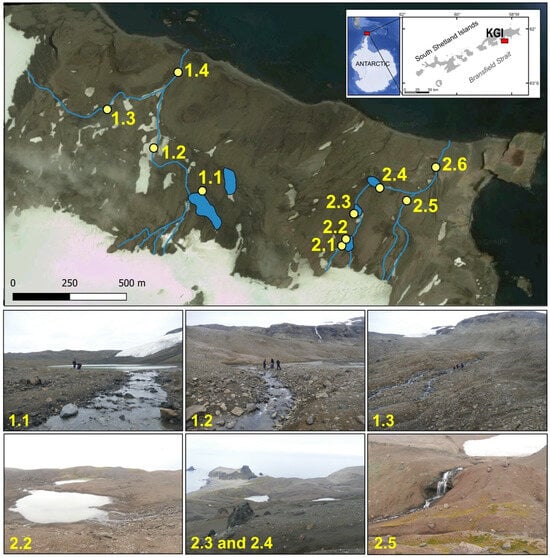

Research area was located in the Lions Rump headland. The cape is situated on King George Island in western Antarctic (Figure 1). The field sampling, including collection of water samples, was carried out on 2 February 2017 during the austral summer season.

Figure 1.

Location of the study area in the King George Island (KGI) and, visualization of the hydrological network of two catchments: Bystry Creek (left 1.1–1.4) and Lions Rump Creek (right 2.1–2.6), and the positions of sampling points in 2017 (Google Earth application).

The research area forms the west side of the entrance to King George Bay and is additionally bounded on three sides by Polonia Glacier, White Eagle Glacier [18] and Stwosz Icefall at the outlet of Kraków Icefield. Due to the diverse biota and geological features representing examples of the littoral habitats of the maritime Antarctic, Lions Rump area was posted as an Antarctic Specially Protected Area No. 151. The purpose of this is to protect natural landforms and native species such as penguins: Adélie (Pygoscelis adeliae), gentoo (P. papua) and chinstrap (P. antarcticus), marine birds, and pinniped mammals [7].

The subjects of this study were the two largest non-glaciated catchments at Cape Lions Rump of the Bystry Creek and Lions Rump Creek. The main creeks are fed both directly by atmospheric precipitation, snow melt water streams and a runoff from melting glaciers. Meteorological conditions during the sampling period were characterised using data obtained from the Henryk Arctowski Polish Antarctic Station, located in the vicinity of Admiralty Bay. These records represent the closest continuous meteorological dataset available for the Lions Rump area. The summary includes air temperature, precipitation and snow cover measurements for January–February 2017, corresponding to the peak melt season in Maritime Antarctica. Although the data were not collected directly at Lions Rump, they reliably describe the regional late-summer climatic background under which the fieldwork was conducted. A concise overview of these parameters is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of meteorological conditions near Admiralty Bay (Arctowski Station) during January–February 2017, representing the climatic background for the Lions Rump sampling period.

The water samples were collected manually into plastic containers 1 L volume. The environmental samples were taken according to Good Laboratory Practice. Water samples were taken at 10 sites in the catchments (Figure 1).

Due to hydrological and geological characteristics of the research area, it can be divided into two parts:

- Bystry Creek catchment, east of Godwin Cliff, in the foreground of White Eagle Glacier. Godwin Cliff is characterized by the dark gray andesitic lavas with crystal-rich rocks and display porphyritic [18]. The soil in this catchment area is characterized as loamy-skeletal, mixed, subgelic, Typic Haplorthels, according to the Soil Taxonomy. Moreover, in the upper part soils in this area have a loamy-sand textured moraine sediments prevailed. Vegetation covers 70% of its surface [2]. There is a large flow lake between the head of the glacier and Sukiennice Hills, while Bystry Creek ends its course in the bay. The stream drains into the bay in the north, forming mouth.

- Lions Rump Creek catchment, bounded to the east by Batke Point and Lions Rump; to the west by Sukiennice Hills and to the south by White Eagle Glacier. The stream flows from the eastern part of the glacier front and flows through three lakes. Lions Rump Creek then terminates at King George Bay. Moraine sediments prevailed in the surface geology, with the occurrence of volcanic rocks in the right side of the catchment [18]. Noteworthy is the lake closest to the mouth due to the immediate vicinity of the colonies of representatives of the Antarctic fauna. This area is home to the most colonies of penguins and Antarctic fur seals (Arctocephalus gazella). The soil in this area is rich in guano and feces of pinniped mammals, which are a carrier of organic matter.

2.2. Sample Preparation and Laboratory Methods

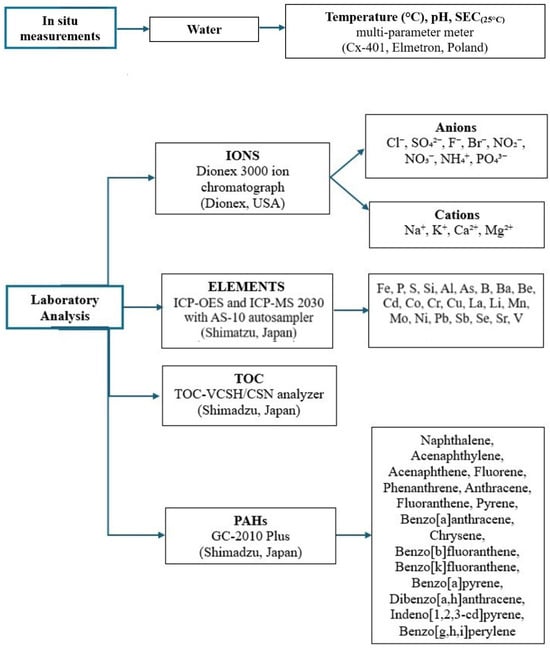

In situ measurements of water temperature, pH, and specific electrical conductivity (SEC(25)) were performed directly at each sampling site immediately after sample collection (Figure 2). Measurements were conducted using a portable multi-parameter meter (Cx-401, Elmetron, Zabrze, Poland), previously calibrated with certified standard solutions.

Figure 2.

Summary flowchart of methodological steps, including field physicochemical measurements and subsequent laboratory analyses of ions, trace elements, TOC, and PAHs.

Following the transport of samples to Poland, where they were stored in a frozen state, laboratory analyses were conducted (Figure 2). Ion concentrations were determined using a DIONEX 3000 ion chromatograph (DIONEX, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The analysis included the following ions: cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) and anions (Cl−, SO42−, F−, Br−), as well as nitrite (NO2−), nitrate (NO3−), ammonium (NH4+), and reactive ortophosphate (PO43−). For the analysis of anions, a Dionex IonPac AS22 analytical column was utilized, and the eluent consisted of 4.5 mM Na2CO3 and 1.5 mM NaHCO3. The flow rate was set to 0.3 mL min−1. For the cation analysis, a Dionex IonPac CS16 analytical column was used with an eluent of 38 mM methanesulfonic acid, and the flow rate was maintained at 0.36 mL min−1. Conductometric detection was applied for both analyses. Total Organic Carbon (TOC) was determined in liquid environmental samples using a catalytic combustion method coupled with non-dispersive infrared (NDIR) detection on the TOC-VCSH/CSN analyzer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Concentrations of elements such as Fe, P, S, and Si in water samples were analyzed using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES 9820, Shimadzu, Japan). For the ICP-OES analysis, the parameters included a plasma gas (Ar) flow rate of 10 L min−1, auxiliary gas flow of 0.6 L min−1, nebulizer gas flow of 0.7 L min−1, and a radio frequency power of 1.2 kW. Additionally, 20 elements-Ag, Al, As, B, Ba, Be, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, La, Li, Mn, Mo, Ni, Pb, Sb, Se, Sr and V-were quantified using Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS 2030 with AS-10 autosampler, Shimadzu, Japan). The ICP-MS analysis was performed with the following parameters: collision gas (Ar) flow at 8.0 L min−1, auxiliary gas flow at 0.7 L min−1, nebulizer gas flow at 0.9 L min−1, and collision cell technology (CCT) with helium gas flow at 6.0 mL min−1, operating in CCT mode with +3 Kinetic Energy Discrimination (KED).

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were determined in water samples by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS). Prior to analysis, 500 mL of each sample was subjected to triple liquid–liquid extraction with dichloromethane (CH2Cl2). The combined organic extracts were dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrated under a gentle stream of nitrogen to a final volume of 1 mL. The analyses were performed using a Shimadzu GC-2010 Plus gas chromatograph equipped with a ZB-5 Plus PAHs capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness). A splitless insert with quartz wool was used. The injection volume was 1.0 μL, the injector temperature was 290 °C, and the injection mode was splitless. Helium served as the carrier gas, with a linear velocity of 48.9 cm s−1. The sampling time was set to 1 min. The oven temperature program was as follows: initial temperature 60 °C (held 1 min), then ramped at 4 °C min−1 to 290 °C, and held for 22 min. The mass spectrometer operated in electron impact ionization mode (70 eV) with selected ion monitoring (SIM) for enhanced sensitivity. Sixteen priority PAHs were identified and quantified based on retention times and mass spectra compared with certified standards: naphthalene, acenaphthylene, acenaphthene, fluorene, phenanthrene, anthracene, fluoranthene, pyrene, benzo[a]anthracene, chrysene, benzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[k]fluoranthene, benzo[a]pyrene, dibenzo[a,h]anthracene, indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene and benzo[g,h,i]perylene.

2.3. Quality Control

Environmental samples were handled with special care to avoid cross-contamination. Error precision for the ions, all elements and TOC analyses were 5% according to repeat analyses of mid-range standards, whilst the detection limits are listed in Table S1 (Supplementary Materials). No contaminants were detected above this limit in the analyses of blank deionised water (18 MΩ·cm) samples.

The analytical accuracy of metal and metalloid determination was checked with certified reference material Trace Metals ICP-Sample 2 (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany), CRM recovery ranged from 97% to 103%. Quantification of PAHs was based on external calibration with five-point standard curves. Detection limits for individual PAHs ranged between 0.001 and 0.005 µg L−1, and mean recoveries for spiked samples were within 83–108%. All analyses were carried out under clean-lab conditions. Procedural blanks and standard reference solutions were included in every analytical batch to ensure accuracy, reproducibility, and control of potential contamination.

2.4. Data Interpretation

The interpretation of the chemical data was carried out by combining descriptive statistics with spatial comparisons along stream transects. Concentration changes from headwaters to downstream sections were used to identify dominant hydrochemical processes, including mineral weathering, marine aerosol input, and volcanic contributions. Diagnostic ion ratios such as Cl−/Na+ and SO42−/Cl− were evaluated to differentiate marine and volcanic sources, following approaches commonly applied in Antarctic hydrochemistry [5,26].

Trace element distributions and TOC were analyzed with respect to their variability within and between catchments, while PAH concentrations and diagnostic ratios were assessed to distinguish between long-range atmospheric transport and local re-emission from sediments. The interpretation of these patterns was made in reference to published studies from polar regions to ensure comparability and to highlight the broader environmental context [27,28].

Atmospheric transport via air masses to the South Shetland Islands was examined with the use of the HySPLIT model (The Hybrid Single Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory Model) [29,30] for modelled 10-day backward trajectories of air masses at 500 m a.s.l., 1000 m a.s.l. and 2000 m a.s.l., based on Global Data Assimilation System meteorological data. The data of volcanic activity as also analysed, based on the Global Volcanism Program database (www.volcano.si.edu accessed on 27 January 2025).

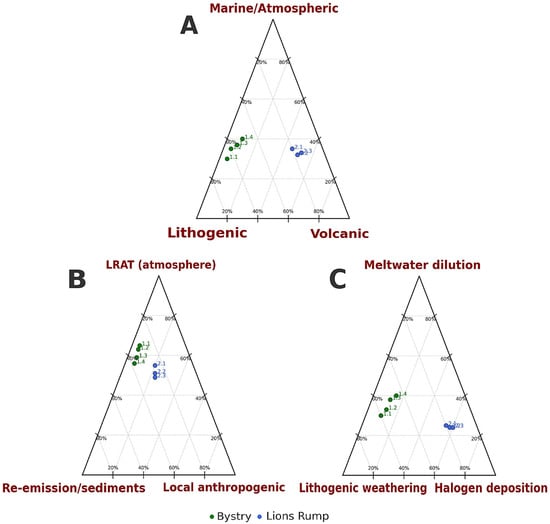

To visualise the relative contribution of key hydrochemical factors, ternary diagrams were constructed in R (version 4.2.2; R Core Team, 2022) using the ggtern package (version 3.3.5; [31]). The approach consisted of three steps:

- (1)

- Selection and grouping of measured parameters.

Measured variables were assigned to conceptual end-members representing dominant environmental controls. For Figure 7A, these were:

- −

- Marine/atmospheric input: Cl−, Na+;

- −

- Lithogenic weathering: Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Si;

- −

- Volcanic/halogen-derived sources: Br−, SO42− (if > LOD).

For Figure 7B (PAH sources):

- −

- Long-range atmospheric transport (LRAT): low-molecular-weight PAHs;

- −

- Re-emission/sediment release: medium-molecular-weight PAHs;

- −

- Local anthropogenic contribution: high-molecular-weight PAHs.

For Figure 7C (dilution vs. weathering):

- −

- Lithogenic weathering: Ca2+, Mg2+, K+, Si;

- −

- Halogen deposition: Cl−, Br−;

- −

- Meltwater dilution: SEC (25 °C), temperature.

- (2)

- Calculation of composite values.

For each sample, all variables within a given group were summed to obtain a single composite value representing the magnitude of each end-member.

- (3)

- Normalisation and ternary transformation.

The three composite values were normalised to proportions summing to 1:

where denotes the composite value for end-member i.

These proportions were used as ternary coordinates and plotted using ggtern. This procedure allows for visualisation of relative hydrochemical influences without implying mechanistic dominance of individual ions or compounds

3. Result and Discussion

3.1. Physicochemical Parameters of Bystry and Lions Rump Creeks: Patterns and Environmental Drivers

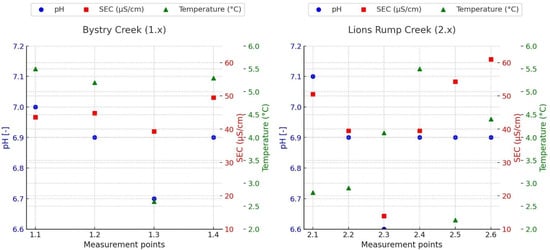

The analysis of basic physicochemical parameters (pH, SEC, and temperature) provides key insights into the functioning of the studied stream ecosystems at Lions Rump. The results presented in (Figure 3, Table 2 and Table S2) indicate clear differences between the two streams, reflecting both local lithological conditions and hydrological factors.

Figure 3.

Distribution of Physicochemical Parameters: pH, Electrical Conductivity (SEC), and Temperature in Bystry Creek (I) and Lions Rump Creek (II) along the creeks courses.

Table 2.

Median concentrations and ranges of TOC, inorganic ions, and elements in Bystry Creek (1.x) and Lions Rump Creek (2.x). Fold Change (FC) = median (Lions Rump)/median (Bystry). Values below detection limit are reported as <LOD.

In Bystry Creek, pH values ranged between 6.67 and 6.97, indicating slightly acidic to near-neutral water. Such conditions are typical of streams fed by snowmelt and groundwater in periglacial environments, where the absence of carbonate buffering minerals makes pH strongly dependent on weathering processes and soil composition [32]. The lowest value (6.67 at site 1.3) may also reflect inputs of groundwater poor in bicarbonate ions, thus reducing buffering capacity.

SEC in Bystry was low (39.3–49.5 µS/cm), reflecting weak mineralization and the oligotrophic character typical of Antarctic waters. Similar values have been reported from other Antarctic streams without direct marine aerosol influence [33]. The lowest SEC coincided with the lowest pH at site 1.3, pointing to dominance of low-mineralized meltwater. This interpretation does not contradict the TOC-based observations presented in Section 3.2, as SEC and TOC respond to different hydrological pathways, and meltwater dilution may co-occur with limited contributions from soil-contacted water. The slightly higher SEC at site 1.4 (49.5 µS/cm), although still within a narrow range, may reflect subtle contributions from localized groundwater inputs, minor weathering of volcanic substrates, or an increased exposure to marine aerosols due to the site’s proximity to the coast.

Water temperature in Bystry ranged from 2.6 °C to 5.5 °C. The slightly wider variability compared to Lions Rump indicates stronger influence of surface factors, such as solar exposure, channel depth, and snowmelt inputs. A weak positive correlation between temperature and SEC suggests slightly enhanced mineral solubility at higher temperatures, a phenomenon also observed in other Antarctic streams [27].

Lions Rump Creek displayed contrasting features. Here, pH was higher (7.06–7.19), indicating neutral to slightly alkaline waters. Rather than reflecting buffering capacity, this elevated pH likely results from the influence of alkaline volcanic lithology or groundwater inputs supplying base cations [34]. The consistently higher pH distinguishes Lions Rump from Bystry, emphasizing the role of bedrock composition in shaping the water’s acidity–alkalinity state.

SEC values in Lions Rump showed a wider range (13.9–61 µS/cm) and less spatial variability than in Bystry Creek. This stability points to continuous ion inputs from geological substrates and groundwater. Importantly, the absence of typical Cl−/Mg2+ ratios characteristic of marine aerosols suggests that local geochemical processes, rather than sea spray, govern water chemistry in Lions Rump [35].

Water temperature in Lions Rump was in the range of 2.8–5.5 °C, reflecting the buffering effect of groundwater inflows and shaded conditions. Unlike in Bystry Creek, no significant relationship between temperature and SEC was observed, suggesting that solubility effects play only a minor role in mineralization here. However, higher temperature observed in the sampling points 1.1, 2.3 and 2.3 may also reflect influence of small lakes occurrence. Lakes support increasing of water temperature in the summer season, what may also change pH and rate of chemical processes. The values observed at sites 1.4 and 2.6 deviate from this pattern, likely because these downstream locations receive more hydrologically mixed water, where meltwater dilution and increased flow dispersion weaken the catchment-specific geochemical signal.

Taken together, the contrasting characteristics of the two creeks likely reflect differences in dominant water sources. Bystry Creek shows slightly acidic waters, low SEC and greater temperature variability, consistent with a strong and dynamic contribution of glacier- and snowmelt waters. In contrast, Lions Rump Creek exhibits neutral-to-alkaline pH, higher SEC and more stable temperatures, suggesting a greater influence of groundwater and volcanic-substrate weathering [32,33,34], possibly combined with slower melting of buried ice or snow patches. These factors highlight the combined effect of meltwater inputs and geological setting in shaping hydrochemistry in Maritime Antarctic catchments. Temperature differences along the studied creeks are also influenced by the through the varied supply of meltwater and water retention in lakes. Such contrasts highlight the role of local geological and hydrological settings as primary drivers of stream water quality in periglacial ecosystems.

3.2. Volcanic, Marine, and Lithogenic Controls on Inorganic Chemistry and TOC in Stream Waters at Lions Rump

The concentrations of TOC, major inorganic ions, and trace elements in both streams are summarized in Table 2, with detailed data in the Supplementary Materials (Tables S3–S5). TOC values were very low, ranging from 0.041 to 0.27 mg L−1 in Bystry Creek and from 0.12 to 0.29 mg L−1 in Lions Rump Creek. In Bystry, TOC increased from upstream sites 1.1 to 1.3 but dropped sharply at the most downstream site 1.4, indicating that organic matter enrichment does not follow a simple downstream-increase pattern, while in Lions Rump, TOC values remained more stable along the course of the stream. Such low concentrations are typical for Antarctic ecosystems, where the limited development of vegetation restricts the input of allochthonous organic matter, and microbial processes, as well as localized contributions from mosses and lichens, dominate the carbon cycle [27,32]. The relative stability of TOC in Lions Rump indicates stronger control by groundwater inflows delivering a uniform load of organic matter, while downstream increases in Bystry indicate stronger control by surface processes such as soil flushing and redistribution of organic-rich cryosols. It should be noted that TOC enrichment reflects contact with soil material or subsurface pathways and does not necessarily indicate dominance of groundwater over meltwater inputs; these processes can operate simultaneously within mixed-source Antarctic streams.

Among the anions, chloride clearly dominated, ranging from 5.2 to 15 mg L−1 in Bystry and from 0.89 to 15 mg L−1 in Lions Rump. These concentrations are several orders of magnitude higher than typical Antarctic background levels (~0.03 mg L−1), and the lack of correlation between Cl− and Mg2+ excludes marine aerosol as the dominant source [35,36,37]. Although chloride is elevated in both catchments, it does not exhibit a consistent spatial pattern, which is expected given that atmospheric deposition should be relatively uniform across such small basins. The observed variability therefore likely reflects a combination of historical volcanic inputs—such as HCl-rich fumarolic gases and halogen-bearing ash layers—and local hydrological processes influencing chloride retention and remobilization [28,38,39,40,41]. Similar long-lasting chloride enrichments have been documented in volcanic and hydrothermal systems of Kamchatka and the Kuril Islands, where fumarolic activity and acid sulfate–chloride waters continuously supply halogens to surface environments [38,39], illustrating that volcanic emissions can produce persistent geochemical signatures even in the absence of a spatially coherent pattern.

Nitrate concentrations were higher at some downstream sites, although they did not follow a consistent longitudinal trend. Values ranged from <LOD to 2.2 mg L−1 in Bystry and from <LOD to 2.4 mg L−1 in Lions Rump. These values are consistent with atmospheric deposition of nitrogen oxides transported from lower latitudes, accumulated in snow cover, and subsequently released during melt events [42]. Sulfate (SO42−) were below LOD in all points of Bystry and Lions Rump Creek, suggesting that either atmospheric deposition was minimal at the time of sampling or that SO42− was efficiently scavenged before reaching the streams.

Sodium (Na+) was the dominant cation in both catchments, but concentrations did not follow a consistent downstream trend. In Bystry, values ranged from 4.3 to 8.1 mg L−1, while in Lions Rump, the highest concentration occurred at the upstream site 2.1 (0.69–6.7 mg L−1). Potassium (K+) ranged from <LOD to 1.2 mg L−1 in Bystry and from <LOD to 1.2 mg L−1 in Lions Rump, while magnesium (Mg2+) remained stable (<LOD–0.069 mg L−1 in Bystry, was <LOD in Lions Rump). Calcium (Ca2+) was detected in both catchments, with concentrations ranging from 0.084 to 4 mg/L in Bystry and 0.0037 to 2.9 mg/L in Lions Rump. Although these values are generally low, their presence suggests minor but measurable inputs from the weathering of Ca-bearing minerals. Slightly higher concentrations in Bystry may reflect greater interaction with secondary minerals derived from volcanic substrates. Episodic Ca–Cl enrichments recorded elsewhere in Antarctic periglacial systems have been attributed to the dissolution of halite- or gypsum-related mineral phases. While classic evaporitic settings are absent in Maritime Antarctica, fumarolic alteration is known to generate secondary halite–gypsum crusts that can be mobilized during snowmelt and subsequently delivered to streams [43]. Thus, the observed Ca2+ levels likely reflect a combination of limited mineral weathering and localized inputs from cryogenic or fumarolic secondary mineral phases.

Trace element analyses revealed notable differences between the two streams. Fe ranged from 5.2 to 72 µg L−1 in Bystry (median 12.05 µg L−1), whereas it was 14–52 µg L−1 in Lions Rump (median 27 µg L−1). The presence of Fe in Bystry reflects more intense weathering of ferromagnesian rocks and soils, while its absence in Lions Rump indicates dilution by snowmelt and groundwater. Mn and Zn were detected in both creeks at low concentrations. In Bystry, Mn ranged from 0.052 to 0.85 µg L−1, while in Lions Rump, it occurred within a narrower range of 0.28–0.34 µg L−1. Zn concentrations remained similarly low, varying between 0.53 and 1.2 µg L−1 in Bystry and 0.77–3.1 µg L−1 in Lions Rump. Pb occurred at ~1 µg L−1 at all sites, Cu remained below the detection limit, and As showed comparable values in both catchments (0.36–0.64 µg L−1 in Bystry; 0.19–0.9 µg L−1 in Lions Rump). Ag and Al were present in both streams, with Ag ranging from 0.12 to 1.0 µg L−1 in Bystry and 0.11 to 0.27 µg L−1 in Lions Rump. Al spanned 6.4–47 µg L−1 in Bystry and 17–39 µg L−1 in Lions Rump. For clarity, the detection limits for the key lithogenic elements discussed in this section were as follows: Fe—0.085 µg L−1, Mn—0.019 µg L−1, Al—0.029 µg L−1, and Ag—0.003 µg L−1. Although overall concentrations are low, the presence and variability in lithogenic elements such as Al, Mn, and Fe suggest contributions from weathering of volcanic substrates in both catchments. Slightly broader ranges in Bystry may indicate more dynamic short-term inputs associated with meltwater flushing surface materials. Episodic enrichments of lithogenic elements remain consistent with the influence of volcanic dust, as suggested by tephra-rich sediment layers reported from Maxwell Bay [34].

Both streams were characterized by low TOC, moderate concentrations of major ions, and trace element signatures typical of pristine Antarctic environments. However, Lions Rump bears a clear volcanic imprint, evidenced by elevated chloride, while Bystry reflects stronger lithogenic weathering inputs. These contrasting hydrochemical signatures demonstrate that water chemistry in Antarctic periglacial catchments is shaped by the interplay of atmospheric, volcanic, and lithological sources.

3.3. Spatial Variability and Sources of PAHs in Two Contrasting Antarctic Streams

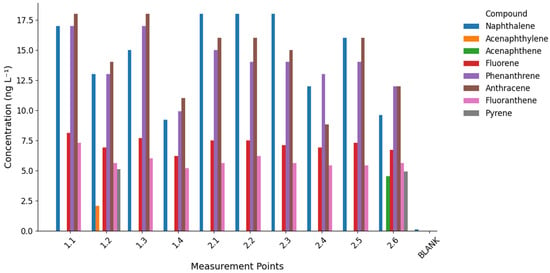

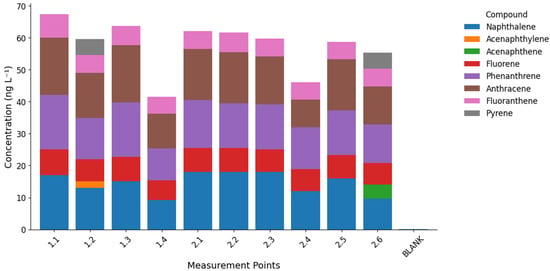

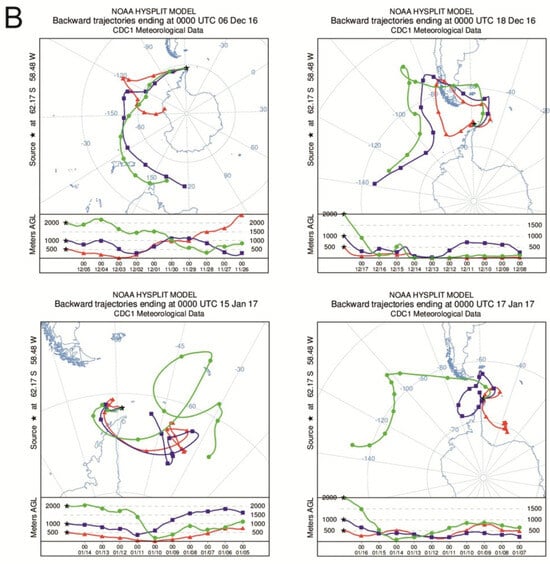

The analysis of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) revealed clear spatial and compositional differences between the studied streams (Figure 4 and Figure 5), with detailed results provided in Table S6 of the Supplementary Materials. The most frequently detected compounds were low- and medium-molecular-weight PAHs, such as naphthalene, fluorene, phenanthrene, anthracene, fluoranthene, and pyrene, while high-molecular-weight PAHs (e.g., benzo[a]anthracene, chrysene, benzo[b]fluoranthene, benzo[a]pyrene) remained below detection limits. Total sum of marked PAHs ranged 41.5–67.4 ng L−1 in Bystry Creek, and 46.1–62.1 ng L−1 in Lions Creek.

Figure 4.

Concentrations of identified polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in water samples from Bystry Creek and Lions Rump Creek. Each group of bars represents a sampling point, with individual compounds shown in different colors.

Figure 5.

Distribution of identified polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in water samples from Bystry Creek and Lions Rump Creek. Each bar represents the total PAH concentration at a given sampling point, subdivided into contributions from individual compounds.

Naphthalene was quantitatively dominant in Lions Rump, reaching up to 18.0 ng L−1 in the middle course (sites 2.1–2.3). In Bystry, its concentrations were slightly lower and more variable (9.2–17.0 ng L−1). Phenanthrene and anthracene were higher in Bystry (up to 17–18 ng L−1 at sites 1.1 and 1.3), while in Lions Rump, they remained lower (median 14.5 ng L−1). Fluorene and fluoranthene also peaked in the upper course of Bystry and decreased downstream, suggesting progressive removal along the flow path. Pyrene was detected only in point 2.6 in Lions Rump (4.9 ng L−1) and in point 1.2 in Bystry (5.1 ng L−1). Acenaphthylene and acenaphthene occurred sporadically—exclusively in Bystry and Lions Rump, respectively.

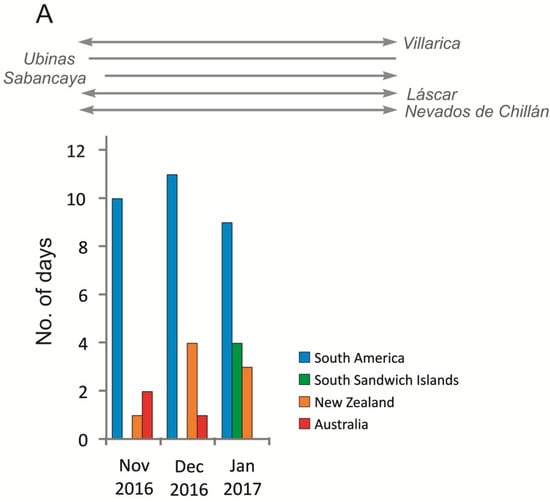

This distribution indicates that long-range atmospheric transport (LRAT) is the main source of PAHs in both streams, particularly for volatile, low-molecular-weight compounds such as naphthalene and phenanthrene. Their physical properties (high vapor pressure and solubility) facilitate transport and deposition in cold polar environments [24,44,45,46]. The absence of heavier PAHs (e.g., benzo[a]pyrene) reflects their stronger particle affinity and limited atmospheric range, leading to deposition closer to emission sources [47]. Another potential pathway of PAH input to the study area involves atmospheric transport of combustion products from biomass burning and large-scale wildfires occurring on Southern Hemisphere continents. Such episodes have been identified as an important source of black carbon and organic pollutants reaching Antarctica, driven by seasonal circulation patterns that promote the transfer of air masses from South America and Africa towards the Antarctic region [41]. Consequently, biomass-burning–derived aerosols may accompany LRAT events, contributing to the deposition of PAHs and soot particles on King George Island. Confirmation of the possible input of PAHs via long-range atmospheric transport (LRAT) is provided by the high frequency of air mass inflow from the South American region. During the period from 1 September 2015 to 31 August 2017, LRAT events occurred on 44% of the analyzed days, with air masses originating from South America on approximately 30% of those days [41]. In the period directly preceding the sampling campaign (December 2016–January 2017), most LRAT episodes were associated with air advection from South America; however, some trajectories also indicated inflow from the South Sandwich Islands, New Zealand, and Australia (Figure 6). During these months, as well as shortly before the sampling period, several volcanoes located along the southern and central parts of the western South American coast were active.

Figure 6.

(A) Total number of days with LRAT occurrence divided into source areas of air masses in the period of 1 November 2016–31 January 2017 compared with South American volcanoes activity. (B) Selected 10 days backward trajectories of air masses at heights 500 m, 1000 m and 2000 m (trajectories of air masses calculated with the HySPLIT model based on Global Data Assimilation System meteorological data, volcanic activity based on Global Volcanism Program, https://volcano.si.edu/).

The observed differences between the two catchments suggest that Lions Rump is more directly exposed to atmospheric inputs, as indicated by the dominance of volatile compounds like naphthalene and pyrene. Bystry, in turn, shows higher levels of medium-molecular-weight PAHs (phenanthrene, anthracene, fluorene, fluoranthene), pointing to stronger retention in soils and sediments. The downstream decline in phenanthrene and anthracene in Bystry can be attributed mainly to their sorption onto suspended particles and organic matter, followed by sedimentation in the streambed. Additionally, meltwater contributions may dilute PAH concentrations along the flowpath, with even small inputs rapidly influencing the stream chemistry due to short and reactive hydrological pathways [48]. Moreover, the larger ice-free drainage area of the Bystry catchment likely enhances the contribution of both surface and sub-cover meltwaters flowing through forefield sediments, which may influence the transport, dilution, and redistribution of PAHs within the system.

In Lions Rump, the downstream increase in some PAHs suggests accumulation during transport and their association with fine particles, consistent with observations from polar snow and rivers where hydrophobic PAHs gradually partition to suspended matter [27,45,49].

Local sources must also be considered. Although LRAT is dominant, emissions linked to station activities (fuel combustion, storage and handling of Arctic diesel) may add to the PAH load in coastal areas. Recent studies from Antarctica confirm that human activities in coastal research stations contribute to measurable increases in PAH concentrations in nearby soils, snow and surface waters [1,24,50]. Even at low concentrations, PAHs pose ecological risks, as cold temperatures slow down their degradation, favoring accumulation in sediments and potential bioaccumulation in food webs [16,48].

PAH distributions in Bystry and Lions Rump confirm the dominance of pyrogenic sources and long-range atmospheric transport, while catchment-specific conditions modulate retention and transformation. Bystry shows evidence of stronger sorption, sedimentation, and dilution of medium-weight PAHs, whereas Lions Rump records direct deposition and accumulation of more volatile compounds. These contrasts illustrate how global-scale transport processes interact with local environmental factors to shape contaminant dynamics in Antarctic periglacial streams.

3.4. Environmental Significance of Hydrochemical Patterns in Antarctic Periglacial Streams

The integrated hydrochemical dataset from Bystry Creek and Lions Rump Creek highlights distinct environmental controls shaping water chemistry in the two periglacial catchments. These contrasts are consistent with patterns described in the physicochemical parameters, the distribution of major ions and trace elements, and PAH concentrations, indicating that lithogenic weathering, atmospheric deposition, halogen inputs, meltwater dilution and local sediment interactions all contribute to the geochemical signatures of the streams.

The ternary diagrams (Figure 7) provide additional insight into these processes. Panel A, comparing lithogenic, volcanic, and marine/atmospheric contributions, shows that Bystry Creek plots consistently toward the lithogenic vertex. This pattern aligns with the slightly acidic pH, low SEC, and elevated Fe and Al observed in the catchment, reflecting weathering of andesitic and basaltic substrates and the influence of moraine-derived sediments [18,33]. In contrast, Lions Rump Creek plots toward the axis representing volcanic and atmospheric inputs, consistent with neutral to alkaline pH, relatively stable and higher SEC, and markedly elevated Cl− that cannot be explained solely by marine aerosols. The chemical patterns indicate a combination of halogen-rich atmospheric deposition, evaporite dissolution, and volcanic aerosol influence [26,28,39,43].

Panel B, comparing LRAT, re-emission from sediments, and local anthropogenic sources, further differentiates the catchments. Bystry Creek, clustering toward the re-emission/sediment vertex, reflects the downstream decline in medium-molecular-weight PAHs (phenanthrene, anthracene, fluorene), which is consistent with sorption to sediments and subsequent dilution by meltwater [48]. Lions Rump Creek, positioned closer to the LRAT axis, exhibits higher contributions of volatile atmospheric PAHs such as naphthalene and pyrene. This aligns with frequent late-summer air mass inflow from South America, South Sandwich Islands, Australia, and New Zealand [41], carrying combustion products, volcanic aerosols, and long-range transported contaminants [24,44,45].

Panel C, illustrating lithogenic weathering, halogen deposition, and meltwater dilution, again separates the two catchments. Bystry Creek lies along the axis between lithogenic weathering and meltwater dilution, consistent with the strong influence of snow- and glacier-derived waters, low mineralization, and high variability in temperature and SEC. Lions Rump Creek, clustering toward the halogen deposition vertex, reinforces the interpretation of elevated Cl− and SO42− as products of halogen-rich atmospheric inputs and dissolution of surface evaporitic crusts that can form during freeze–thaw cycles in coastal Antarctic environments [34,43].

Taken together, these patterns demonstrate that Bystry Creek is dominated by lithogenic processes, meltwater dilution, and sediment interactions, while Lions Rump Creek integrates additional signals from halogen deposition, volcanic aerosols, and more direct LRAT. Despite their proximity, the two catchments thus provide complementary perspectives on the influence of local geology, atmospheric circulation, and meltwater dynamics on Antarctic freshwater systems. The predominance of low- and medium-molecular-weight PAHs, along with the absence of heavier compounds, further confirms long-range atmospheric transport as the principal vector of organic contaminants to the region [1,46].

Figure 7.

Ternary diagrams showing the relative contributions of different sources and processes shaping the hydrochemistry of Bystry and Lions Rump streams. (A) Major ion sources: lithogenic, volcanic, and marine/atmospheric inputs. (B) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) sources: long-range atmospheric transport (LRAT), local anthropogenic emissions, and re-emission/sediment release. (C) Factors controlling physicochemical parameters: lithogenic weathering, halogen deposition, and meltwater dilution. Plots were generated in R using the ggtern package.

Although these trends are coherent, it is important to acknowledge that the interpretation is based on a single austral summer season, which limits the ability to capture interannual variability in meltwater supply, atmospheric trajectories, and solute fluxes. Additionally, the lack of isotopic tracers (e.g., δ18O, δ2H, δ37Cl, δ34S) constrains the precision with which marine, volcanic, and lithogenic components can be quantitatively distinguished. Nonetheless, the combined use of major ions, trace elements, PAHs and ternary diagrams provides a sufficiently robust qualitative framework to infer dominant processes, while multi-season and isotope-supported datasets in future studies would allow these interpretations to be refined.

4. Conclusions

The obtained results clearly demonstrate that the water chemistry in the analysed catchments is shaped by local geological conditions, meltwater dynamics, and the degree of hydrological connectivity within the landscape. In Lions Rump Creek, the ionic composition and elemental ratios show a strong link to the mineralogy of the underlying bedrock, resulting in distinct water types and stable chemical signatures. In contrast, Bystry Creek exhibits a more complex pattern, with greater variability in hydrochemical parameters, reflecting stronger hydrological integration and more intensive interactions between meltwater, freshly exposed rocks, and unconsolidated sediments.

The observed patterns in conductivity, pH, ionic proportions and trace-element presence highlight the importance of the early ablation period. It is during this phase that the first meltwaters reach the stream channels, transporting both products of chemical weathering and substances previously accumulated within the snowpack. This indicates that early melt conditions provide a unique opportunity to capture the most dynamic geochemical processes operating within these catchments.

These findings carry practical implications for the monitoring of Antarctic freshwater systems, as they confirm the value of parameters such as conductivity, pH, major ions and selected trace elements as sensitive indicators of environmental change. At the same time, the distinct differences between the two catchments emphasise that monitoring networks should account for their geological and hydrological specificity, as well as the differing pace and direction of their responses to climatic drivers.

Future research should expand analyses to cover the full melt season, enabling assessment of how water chemistry evolves throughout the ablation cycle, and incorporate isotopic tracers to precisely distinguish water sources and dominant flowpaths. Integrating these approaches will deepen our understanding of the processes shaping hydrochemistry in periglacial environments and provide a robust basis for long-term monitoring of changes occurring in Antarctic freshwater ecosystems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17243549/s1, Table S1: The scope of metrological characteristics of analytical methods used to determine the content of analytes in the tested samples. Table S2: Physicochemical parameters (pH, specific electrical conductivity, SEC, and water temperature) measured in waters across the study area. Table S3: Total Organic Carbon (TOC) concentrations in water samples collected in 2017 across the study sites. Table S4: Concentrations of major and trace elements measured in water samples collected across the study area. The accompanying spider diagrams below the table illustrate the relative enrichment and depletion patterns of individual elements, allowing for comparison of geochemical signatures among sampling sites. Table S5: Concentrations of inorganic ions measured in water samples from the study area. The dataset includes major anions and cations used to characterize the hydrochemical composition and assess spatial variability in ionic backgrounds across different hydrological settings. Table S6: Concentrations of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) measured in water samples collected across the study area.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., M.S. and D.S.; Methodology, J.P., A.M.S.-S., M.F. and A.Z.-F.; Software, R.J.B.; Validation, J.P., A.M.S.-S., M.F. and A.Z.-F.; Formal Analysis, J.P. and Ż.P.; Investigation, J.P.; Resources, J.P.; Data Curation, J.P., D.S. and R.J.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.P., D.S. and A.M.S.-S.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.P., M.S., D.S., R.J.B., M.F., A.Z.-F., S.L.-K., A.M.S.-S., M.W. and Ż.P.; Visualization, J.P. and D.S.; Supervision, Ż.P.; Project Administration, J.P.; Funding Acquisition, J.P., Ż.P. and A.M.S.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was carried out as part of an agreement between the Institute of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Polish Academy of Science (IBB, PAS), and Gdańsk University of Technology. This study was also partially funded by the National Science Centre of Poland grant NCN 2023/48/C/ST10/00167. We are also grateful to Sebastian Czapiewski for the help with air masses trajectory modelling. Additionally, this research was funded by Gdynia Maritime University under grant No. WZNJ/2025/PZ/04, titled ‘Systemic Management of Quality, Environment, and Safety in the Product Lifecycle’.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

One of the co-authors has a previously existing professional conflict of interest with two researchers affiliated with UMCS (Poland). This relationship is unrelated to the present study and had no influence on the design of this research, the collection or interpretation of the data, the preparation of this manuscript, or the decision to publish the results. The authors declare no other conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of this manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Szumińska, D.; Potapowicz, J.; Szopińska, M.; Czapiewski, S.; Falk, U.; Frankowski, M.; Polkowska, Ż. Sources and Composition of Chemical Pollution in Maritime Antarctica (King George Island), Part 2: Organic and Inorganic Chemicals in Snow Cover at the Warszawa Icefield. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 796, 149054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, I.C.C.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Fernandes, R.B.A.; Pereira, T.T.C.; Nieuwendam, A.; Pereira, A.B. Active Layer Thermal Regime at Different Vegetation Covers at Lions Rump, King George Island, Maritime Antarctica. Geomorphology 2014, 225, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simas, F.N.B.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Filho, M.R.A.; Francelino, M.R.; Filho, E.I.F.; da Costa, L.M. Genesis, Properties and Classification of Cryosols from Admiralty Bay, Maritime Antarctica. Geoderma 2008, 144, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simas, F.N.B.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Melo, V.F.; Albuquerque-Filho, M.R.; Michel, R.F.M.; Pereira, V.V.; Gomes, M.R.M.; da Costa, L.M. Ornithogenic Cryosols from Maritime Antarctica: Phosphatization as a Soil Forming Process. Geoderma 2007, 138, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szopińska, M.; Szumińska, D.; Bialik, R.J.; Chmiel, S.; Plenzler, J.; Polkowska, Ż. Impact of a Newly-Formed Periglacial Environment and Other Factors on Fresh Water Chemistry at the Western Shore of Admiralty Bay in the Summer of 2016 (King George Island, Maritime Antarctica). Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olech, M.; Massalski, A. Plant Colonization and Community Development on the Sphinx Glacier Forefield. Geographia 2001, 25, 111–119. [Google Scholar]

- Korczak−Abshire, M.; Węgrzyn, M.; Angiel, P.J.; Lisowska, M. Pygoscelid Penguins Breeding Distribution and Population Trends at Lions Rump Rookery, King George Island. Pol. Polar Res. 2013, 34, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montone, R.C.; Alvarez, C.E.; Bícego, M.C.; Braga, E.S.; Brito, T.A.S.; Campos, L.S.; Fontes, R.F.C.; Castro, B.M.; Corbisier, T.N.; Evangelista, H.; et al. Environmental Assessment of Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctica. In Adaptation and Evolution in Marine Environments; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 157–175. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, K.A. Reducing Sewage Pollution in the Antarctic Marine Environment Using a Sewage Treatment Plant. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2004, 49, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, C.X.; Cárdenas, C.A.; González-Aravena, M.; Rebolledo, L.; Cruz, F.S. Mapping Scientific Fieldwork Data: A Potential Tool for Improving and Strengthening Antarctic Specially Protected Areas as an Effective Measure for Protecting Antarctic Biodiversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 2024, 33, 929–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipro, C.V.Z.; Bustamante, P.; Taniguchi, S.; Montone, R.C. Persistent Organic Pollutants and Stable Isotopes in Pinnipeds from King George Island, Antarctica. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 64, 2650–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potapowicz, J.; Szumińska, D.; Szopińska, M.; Polkowska, Ż. The Influence of Global Climate Change on the Environmental Fate of Anthropogenic Pollution Released from the Permafrost: Part I. Case Study of Antarctica. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 1534–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargagli, R.; Rota, E. Environmental Contamination and Climate Change in Antarctic Ecosystems: An Updated Overview. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2024, 3, 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Shi, G.; Revell, L.E.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, C.; Wang, D.; Le Ru, E.C.; Wu, G.; Mitrano, D.M. Long-Range Atmospheric Transport of Microplastics across the Southern Hemisphere. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Illuminati, S.; Notarstefano, V.; Tinari, C.; Fanelli, M.; Girolametti, F.; Ajdini, B.; Scarchilli, C.; Ciardini, V.; Iaccarino, A.; Giorgini, E.; et al. Microplastics in Bulk Atmospheric Deposition along the Coastal Region of Victoria Land, Antarctica. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 175221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, S.B. Persistent Organic Pollutants in Antarctica: Current and Future Research priorities. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muir, D.; Gunnarsdóttir, M.J.; Koziol, K.; von Hippel, F.A.; Szumińska, D.; Ademollo, N.; Corsolini, S.; De Silva, A.; Gabrielsen, G.; Kallenborn, R.; et al. Local Sources versus Long-Range Transport of Organic Contaminants in the Arctic: Future Developments Related to Climate Change. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2025, 4, 355–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pańczyk, M.; Nawrocki, J. Geochronology of Selected Andesitic Lavas from the King George Bay Area (SE King George Is Land). Geol. Q. 2011, 55, 323–334. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, I.R.; Silva-filho, E.V.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R. Heavy Metal Contamination in Coastal Sediments and Soils near the Brazilian Antarctic Station, King George Island. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2005, 50, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, I.C.C.; Schaefer, C.E.G.R.; Michel, R.F.M.; Fernandes, R.B.A.; Pereira, T.T.C.; de Andrade, A.M.; Francelino, M.R.; Fernandes Filho, E.I.; Bockheim, J.G. Long Term Active Layer Monitoring at a Warm-Based Glacier Front from Maritime Antarctica. Catena 2017, 149, 572–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatur, A.; Keck, A. Phosphates in Ornithogenic Soils of the Maritime Antarctic. In Proceedings of the NIPR Symposium on Polar Biology. National Institute of Polar Research, Tokyo, Japan, 6–8 December 1989; Volume 3, pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Anzano, J.; Abás, E.; Marina-Montes, C.; del Valle, J.; Galán-Madruga, D.; Laguna, M.; Cabredo, S.; Pérez-Arribas, L.-V.; Cáceres, J.; Anwar, J. A Review of Atmospheric Aerosols in Antarctica: From Characterization to Data Processing. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cincinelli, A.; Martellini, T.; Bittoni, L.; Russo, A.; Gambaro, A.; Lepri, L. Natural and Anthropogenic Hydrocarbons in the Water Column of the Ross Sea (Antarctica). J. Mar. Syst. 2008, 73, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchiato, M.; Argiriadis, E.; Zambon, S.; Barbante, C.; Toscano, G.; Gambaro, A.; Piazza, R. Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in Antarctica: Occurrence in Continental and Coastal Surface Snow. Microchem. J. 2014, 119, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, M.L.; Bengtson Nash, S.M.; Hawker, D.W.; Shaw, E.C.; Cropp, R.A. The Distribution of Persistent Organic Pollutants in a Trophically Complex Antarctic Ecosystem Model. J. Mar. Syst. 2017, 170, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, A.; Heaton, T.; Langford, H.; Newsham, K. Chemical Weathering and Solute Export by Meltwater in a Maritime Antarctic Glacier Basin. Biogeochemistry 2010, 98, 9–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, L.W.; Benner, R.; McClelland, J.W.; Peterson, B.J.; Holmes, R.M.; Raymond, P.A.; Hansell, D.A.; Grebmeier, J.M.; Codispoti, L.A. Linkages among Runoff, Dissolved Organic Carbon, and the Stable Oxygen Isotope Composition of Seawater and Other Water Mass Indicators in the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2005, 110, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monien, D.; Monien, P.; Brünjes, R.; Widmer, T.; Kappenberg, A.; Silva Busso, A.A.; Schnetger, B.; Brumsack, H.-J. Meltwater as a Source of Potentially Bioavailable Iron to Antarctica Waters. Antarct. Sci. 2017, 29, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draxler, R.; Rolph, G. HYSPLIT (Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory); Air Resources Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2003.

- Draxler, R.; Stunder, B.; Rolph, G.; Stein, A.; Taylor, A. HYSPLIT4 User’s Guide; Version 4.9; Air Resources Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2009.

- Hamilton, N.E.; Ferry, M. Ggtern: Ternary Diagrams Using Ggplot2. J. Stat. Softw. 2018, 87, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, D.d.V.; Souza, J.J.L.L.; de Simas, F.N.B.; Oliveira, F.S.; de Schaefer, C.E.G.R. Hydrogeochemistry and Chemical Weathering in a Periglacial Environment of Maritime Antarctica. Catena 2021, 197, 104959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunes, Y.; Balci, N. Sediment and Water Geochemistry Record of Water-Rock Interactions in King George Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Antarct. Sci. 2022, 34, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monien, P.; Schnetger, B.; Brumsack, H.-J.; Hass, H.C.; Kuhn, G. A Geochemical Record of Late Holocene Palaeoenvironmental Changes at King George Island (Maritime Antarctica). Antarct. Sci. 2011, 23, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domineé, F.; Shepson, P.B. Air-Snow Interactions and Atmospheric Chemistry. Science 2002, 297, 1506–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesselet, R.; Morelli, J.; Buat-Menard, P. Variations in Ionic Ratios between Reference Sea Water and Marine Aerosols. J. Geophys. Res. 1972, 77, 5116–5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, B.; Rivas, T.; Garciarodeja, E.; Prieto, B. Distribution of Ions of Marine Origin in Galicia (NW Spain) as a Function of Distance from the Sea. Atmos. Environ. 2007, 41, 4396–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalacheva, E.; Taran, Y.; Kotenko, T.; Hattori, K.; Kotenko, L.; Solis-Pichardo, G. Volcano–Hydrothermal System of Ebeko Volcano, Paramushir, Kuril Islands: Geochemistry and Solute Fluxes of Magmatic Chlorine and Sulfur. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2016, 310, 118–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelenski, M.; Taran, Y. Volcanic Emissions of Molecular Chlorine. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 87, 210–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkenmajer, K. Geological Relations at Lions Rump. King George Island (South Shetland Is Land, Antarctica). Stud. Geol. Pol. 1981, 72, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Szumińska, D.; Czapiewski, S.; Szopińska, M.; Polkowska, Ż. Analysis of Air Mass Back Trajectories with Present and Historical Volcanic Activity and Anthropogenic Compounds to Infer Pollution Sources in the South Shetland Islands (Antarctica). Bull. Geography. Phys. Geogr. Ser. 2018, 15, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, E.W. Signals of Atmospheric Pollution in Polar Snow and Ice. Antarct. Sci. 1990, 2, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, J.K. Evaporites; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-13511-3. [Google Scholar]

- Halsall, C.J.; Barrie, L.A.; Fellin, P.; Muir, D.C.G.; Billeck, B.N.; Lockhart, L.; Rovinsky, F.Y.; Kononov, E.Y.; Pastukhov, B. Spatial and Temporal Variation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Arctic Atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1997, 31, 3593–3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masclet, P.; Hoyau, V.; Jaffrezo, J.L.; Cachier, H. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Deposition on the Ice Sheet of Greenland. Part I: Superficial Snow. Atmos. Environ. 2000, 34, 3195–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wania, F.; MacKay, D. Peer Reviewed: Tracking the Distribution of Persistent Organic Pollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1996, 30, 390A–396A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobiszewski, M.; Namieśnik, J. PAH Diagnostic Ratios for the Identification of Pollution Emission Sources. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 162, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szopińska, M.; Namieśnik, J.; Polkowska, Ż. How Important Is Research on Pollution Levels in Antarctica? Historical Approach, Difficulties and Current Trends. In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 79–156. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffrezo, J.L.; Clain, M.P.; Masclet, P. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in the Polar Ice of Greenland. Geochemical Use of These Atmospheric Tracers. Atmos. Environ. 1994, 28, 1139–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Lin, T.; Sun, H.; Li, R.; Liu, X.; Guo, Z.; Ma, X.; Yao, Z. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Fildes Peninsula, Maritime Antarctica: Effects of Human Disturbance. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).