Abstract

In this study, CuO nanoparticles were synthesised by chemical precipitation assisted by ultrasonic irradiation (UI), a rapid and environmentally friendly procedure without high temperature that enhances the sustainability of the synthesis process. They were also employed as a catalyst to activate peroxydisulfate (PDS) in the removal of ciprofloxacin (CIP) from a polluted solution. The effects of various factors, such as CIP concentration, catalyst dosage, PDS concentration, and initial pH, on the efficiency of this contaminant treatment were investigated. Under optimal conditions, CIP and TOC removal reached 100% and 49%, respectively, after only 30 min of reaction time and using high initial concentrations of CIP (20 mg/L), PDS (0.5 mM), and CuO (0.5 g/L) in pH (10). For the best set of processing conditions, pseudo-first-order reaction rate kinetics can be assumed and characterised. The possible degradation pathway of CIP is also suggested. Furthermore, by quenching experiment, the presence of O2−*, *OH, and SO4−* were identified, with O2−* being a radical species with great impact on CIP removal. This study demonstrates that, in alkaline environments, ultrasonically synthesised CuO can effectively activate PDS for the degradation of CIP, achieving total removal within 30 min. The results indicate that UI-synthesised CuO is a very promising catalyst for the removal of emerging organic pollutants.

1. Introduction

Recently, the emergence of organic pollutants in the environment, especially in aquatic environments, has been increasing sharply. This issue is attracting global attention due to the persistent, toxic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic characteristics of these pollutants. Emerging organic pollutants pose a high risk to the environment, ecosystems, human health, and sustainable development [1,2,3]. Antibiotics are the most important type of emerging organic pollutants with a significant impact on the treatment of human and animal diseases. Antibiotic consumption has increased recently, especially due to the COVID-19 pandemic [4]. Ciprofloxacin (CIP, 1-cyclopropyl-6-fluoro-4-oxo-7-(piperazine-1-yl)-quinoline-3-carboxylic acid, whose structure is illustrated in Figure 1) is an antibiotic belonging to the second generation of fluoroquinolones, which have a low cost, excellent oral ingestion properties, and great activity against bacteria and high antibacterial properties (for Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria through DNA inhibition [5]), therefore being the most used drug for the treatment of humans and animals [6,7,8,9,10]. So, after ingestion of CIP, a small amount is metabolised in the bodies of humans and animals, and a large amount is released into the aquatic environment in its pharmacologically active form through urine and faeces [8]. Because of its high solubility in water at different pH levels and high persistence in soil and water, high concentrations of CIP have been identified in aquatic environments, such as wastewater, surface water, groundwater, and even drinking water, especially in hospitals, healthcare centres, and wastewater treatment plants from pharmaceutical industries [11]. For instance, according to the literature, almost 31 mg/L and 0.7–124.5 µg/L of CIP have been reported in pharmaceutical and hospital wastewaters, respectively [12]. CIP and some of its transformation products have toxic effects on aquatic microorganisms and plants [8]. Unfortunately, due to process difficulties and low biodegradability, most of the usual physical and biological wastewater treatment plants cannot effectively treat CIP in wastewater [5]. Therefore, seeking a sustainable strategy for the removal of CIP from wastewater is essential. Table 1 reports several studies in the literature that use advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) to treat CIP in an aquatic environment.

Figure 1.

Ciprofloxacin’s chemical structure.

The advanced oxidation process is a suitable strategy for the treatment of emerging organic pollutants in aquatic environments [13,14]. Recently, AOPs based on sulphate radicals (SO4−*) and hydroxyl radicals (*OH) have received special attention for pollutant remediation. In AOPs, sulphate radicals have received more attention than hydroxyl ones due to their excellent redox properties (2.5–3.1 V), according to the activation method; efficient remediation of organic contaminants; longer half-life (30–40 μs), which is much greater than *OH (less than 1 μs) (due to the faster electron transfer reaction [15]); and good performance over a wide range of pH [16,17,18,19]. Also, persulfate salts are more economical and easier to transport [16,20]. Usually, SO4−* is produced via haemolytic cleavage of the peroxide bond in peroxydisulfate (PDS, S2O82−) or peroxymonosulfate (PMS, HSO5−) [16]. In addition, PDS and PMS have good solubility in water, are environmentally friendly compounds, and are relatively stable solids [21].

Table 1.

CIP degradation in aquatic media by photocatalytic and nano-catalytic system.

Table 1.

CIP degradation in aquatic media by photocatalytic and nano-catalytic system.

| Row | NMs | Dosage of NMs (g/L) | Oxidant | Dosage of Oxi. (mM) | Concentration of CIP (mg/L) | pH | Time (min) | Radicals | Mechanism | Removal (%) | Other Condition | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | nZVMn | 1 | PDS | 0.21 (50 mg/L) | 10 | 2 | 80 | SO4−* *OH | Metal catalyst | 95 | Only nZVMn removes 63% (Absence of PDS) | [8] |

| 2 | ZnO | 0.25 | PDS | 1.76 (476.06 mg/L) | 25 | 7 | 10 | SO4−* *OH | Metal catalyst | 99 | Under US (60 kHz) Only US removes 36% US/ZnO removes 70% US/ZnO/PS removes 99% | [22] |

| 3 | CeO2–Ag/AgBr (21.26 wt% of Ag) | 1 | - | 10 | - | 120 | h+, *OH O2−* | Photocatalytic | 93.05 | UV-Vis | [10] | |

| 4 | AgI (20 wt%)/BiOBr | 0.5 | - | - | 10 | - | 60 | h+, *OH O2−* | Photocatalytic | 90.9 | UV-Vis λ ≥ 420 nm | [23] |

| 5 | Ag@PCNS/BiVO4 | 1 | - | - | 10 | - | 120 | h+, *OH O2−* | Photocatalytic | 92.6 | UV-Vis λ ≥ 420 nm | [11] |

| 6 | Bi2WO6/NSBC | 1 | - | - | 5 | 3–9 | 75 | h+, *OH O2−* | Photocatalytic | 90.33 | UV-Vis | [1] |

| 7 | OM-Co3O4 | 0.1 | PMS | 1 | 5 | 9 | 60 | SO4−* *OH | Metal catalyst | 95 | Ambient temperature | [2] |

| 8 | Bi1−xSrxFeO3 | 1 | PDS | 1 | 10 | 6 | 60 | 1O2 SO4−* *OH | Metal catalyst | 95 | [16] | |

| 9 | Zn-doped Cu2O | 0.6 | - | - | 20 | - | 240 | h+, *OH | Photocatalytic | 94.5 | The light range was 400–1100 nm | [24] |

| 10 | Cu2MG | 0.3 | - | - | 10 | - | 75 | *OH O2−* | Son photocatalytic | 94 | US bath (40 kHz–120 W) and UV-Visible | [7] |

| 11 | rGO-BiVO4-Zn | 0.3 | - | - | 13.25 (4 × 10−5 M) | 7 | 60 | h+, O2−* | Photocatalytic | 98.4 | UV-Visible λ < 400 nm | [9] |

| 12 | CuO | 0.5 (6.3 mmol/L) | PDS | 1 (1mmol/L) | 10 (0.03 mmol/L) | 8 | 60 | O2−*, 1O2 SO4−* *OH | Metal catalyst | 100 | Bicarbonate = 10 mmol/L | [25] |

Copper oxide (CuO) is a well-known p-type semiconductor with a narrow band gap [26], thus requiring less energy to activate (transferring electrons from the valence band to the conduction band) than materials with a high energy bandgap. Such a particular property of CuO may suggest this metallic oxide as a strong candidate for the decontamination of water polluted by persistent organic pollutants (POPs). CuO oxide nanoparticles are available non-toxic materials. Due to its large surface area to volume ratio, an in particular its optical properties and narrow band gap, CuO is an excellent candidate for a variety of applications, mainly as a catalyst or adsorbent [27,28]. The literature offers a wide variety of synthesis methods in order to produce nanomaterials with different properties [29,30]. Such methodologies are often constrained by limitations such as high pressure and temperature requirements [31,32,33,34,35,36], toxic solvents, reducing and coating agents [31,32,34,35,36,37], and long reaction times [31,32,33], among many others, which have an impact on the properties of the synthesised nanomaterials. Therefore, it is important to highlight ultrasonic irradiation as an experimental green tool that facilitates the production of engineered nanomaterials through fast and easy methods [30,38,39,40].

Although transition metal-activated persulfate systems have been widely investigated, there is still a lack of studies achieving high pollutant degradation at low oxidant and catalyst dosages under alkaline conditions. Despite a wide investigation into transition metal oxide-activated persulfate systems, numerous critical gaps remain. Most synthesis processes require calcination at high temperatures (>200 °C), which uses more energy and has a bigger impact on the environment [25,41,42,43,44]. In addition, most of the studies were conducted at an acidic or neutral pH, limiting applicability to alkaline industrial wastewaters. A systematic examination of the relationship between catalyst surface properties and radical speciation mechanisms is also missing. Moreover, achieving high degradation efficiency (>95%) at low chemical dosages and high pollutant concentrations remains challenging.

The current investigation bridges these gaps by integrating sustainable ultrasound-assisted synthesis without high-temperature processing, systematic optimisation demonstrating superior performance under alkaline conditions, and mechanistic elucidation of pH-dependent radical speciation. The novelty of this work lies in the synergistic integration of green synthesis, enhanced catalytic performance, and mechanistic understanding to advance practical water treatment applications. Therefore, the primary focus of this study is the synthesis of CuO through chemical precipitation with the assistance of UI. CuO is intended to be used as a catalyst for the decomposition of CIP while employing PDS as the oxidant. The impact of experimental conditions on CIP removal will also be evaluated, including the initial pH, dosage of the catalyst, and concentration of the oxidant and CIP. Moreover, an exploration of the kinetics of the treatment process and a detailed mechanistic analysis were conducted to elucidate radical pathways, which provided fresh perspectives on persulfate activation chemistry.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Copper sulphate (CuSO4) was obtained from Riedel-de Haen (Seelze, Germany). Sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and 1,4-benzouquinone (99%) were purchased from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium) and used as received. Analytical-grade potassium peroxydisulfate (K2S2O8) was obtained from Merck Eurolab (Hoeilaart, Belgium), and sodium nitrite (NaNO2) was obtained from Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany). Ciprofloxacin (≥98.0%) and methanol (CH3OH) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and tert-butanol (TBA, purity ≥ 99.0%) was supplied by Fisher Chemical (Leicester, UK). All solutions were prepared using Milli-Q ultra-pure water (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA). Also, HPLC-grade acetonitrile was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), ammonium formate (NH4HCO2) from Acros Organics (Belgium), and formic acid (CH2O2) (>98%) was supplied by Honeywell (Machelen, Belgium) for the analysis of CIP. The pH value was adjusted by NaOH and H2SO4 (>95%), which were obtained from Acros Organics (Geel, Belgium) and Fisher Chemical (Loughborough, UK), respectively.

2.2. Analytical Methods

CIP concentrations were measured employing an HPLC system (Agilent 1100, Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with a G1314A UV detector. The separation was performed using an Agilent Eclipse Plus C18 column (Zorbax Eclipse Plus, 4.6 × 100 mm; particle size (dp): 3.5 μm, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The column temperature was maintained at 30 °C by the thermostatic compartment. The mobile phase included a 10 mM ammonium formate solution in Milli-Q ultra-pure water, with the pH adjusted to 2.8 using formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient elution programme was set for A/B (v/v) from 90/10 at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The injection volume was 3 µL, and the detector wavelength was set at 280 nm. The duration of the analysis was 19 min, with the peak of ciprofloxacin occurring at the 11th minute. CIP degradation was monitored by HPLC-UV, which provides high sensitivity and selectivity for accurate quantification. Although UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy could offer supplementary visual evidence of degradation, it was not conducted due to analytical limitations. HPLC quantification is more reliable for kinetic analysis, as it eliminates interference from catalyst particles and transformation intermediates. Furthermore, the reconditioning time of the column to the initial condition was 5 min. TOC values were measured by a TOC-L Analyser (TNM-L ROHS, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan).

2.3. Synthesis and Characterisation of CuO

In order to prepare CuO, 4.39 g of copper (II) sulphate (CuSO4) was dissolved in 200 mL of Milli-Q ultra-pure water (solution A) under stirring (250 RPM) and sonicated in a UI bath for 15 min. Next, 5 g of NaOH was dissolved in 100 mL of Milli-Q ultra-pure water (solution B), and this resulting solution was added dropwise (15 mL/min) using a Watson Marlow 120U/R peristaltic pump (Cornwall, UK) to the reactor, where solution A was maintained under UI (300 W and 35 kHz) using an ultrasound bath (Bandelin Sonorex digiplus, Berlin, Germany) at 60 °C. The reactor was kept under stable operating conditions (UI (300 W and 35 kHz) and temperature (60 °C)) for 30 min. Thereafter, the synthesised powder particles were removed, washed carefully with water, and then dried overnight in a vacuum oven at 105 °C. After that, the powders produced were ready for characterisation and storage for future applications.

The crystal phase composition of the produced particles was examined by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku Geigerflex, Tokyo, Japan). For this purpose, continuous scans were taken from 30° to 100° 2θ at the scan rate of the goniometer speed of 2° 2θ/min. The crystallite size of the synthesised nanomaterial was calculated by the Scherrer equation:

where D is the average crystallite size, K indicates a dimensionless shape factor, λ is the wavelength of X-rays, β represents the full width at the half-maximum intensity (FWHM) of the sample, and θ refers to the Bragg angle. The specific surface area of the powders was determined using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) adsorption isotherm. Adsorption/desorption isotherms were obtained employing Micromeritics Gemini 2380 (Norcross, GA, USA) equipment to measure the porosity features of the synthesised particles. The powder samples were degasified at 120 °C overnight before measurement. Using UV-Vis scanning spectrometry (UV-3100, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), the UV-Vis spectra of the synthesised powders were recorded. The morphological characteristics of the powder particles were analysed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) (Hitachi SU-70, Tokyo, Japan).

D = Kλ/βcos(θ)

Zeta potential measurements were conducted by employing Zetasizer equipment (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern, UK) to determine the electrical charge properties of the particle surfaces. Aqueous suspensions of the particles (10 mL) were prepared through dilution under ultrasonic irradiation in a Sonoswiss 6lt ultrasonic cleaning bath (Ramsen, Switzerland). The pH of the suspensions was adjusted within the acidic and alkaline ranges using HCl or NaOH, respectively.

2.4. Removal of Ciprofloxacin (CIP)

The CIP solution was prepared by dissolving 20 mg of CIP in 1 L of deionised water. Batch experiments for the removal of CIP were conducted in a 400 mL beaker equipped with a magnetic stirrer working at 450 rpm. The synthesised particles were spread on 100 mL of effluent. Various operating conditions, including treatment time (2, 5, 10, 15, and 30 min), temperature (ambient), pH (3, 5, 7, and 10), CuO dosage (0, 0.1, 0.250, 0.5, and 1 g/L), concentration of potassium peroxodisulfate (0.5 and 1 mM), and the concentration of CIP (5, 10, and 20 mg/L), were studied in the treatment of CIP in the CuO/PDS system. At certain times, 0.75 mL samples were withdrawn from the reactor and filtered with syringe filters (0.45 µm), and the oxidation was immediately quenched by the addition of 0.75 mL of NaNO2 (1 mM) in HPLC vials. The amount of CIP removal by the CuO/PDS system was calculated according to Equation (2):

where C0 is the starting concentration of CIP, while Ct represents the concentration of CIP at a designated period.

CIP removal (%) = ((C0 − Ct)/C0) × 100%

The kinetics of the CIP removal reaction are described by Equation (3) according to a pseudo-first-order model under the optimum condition of the degradation process:

d[CIP]/dt = −kobs × [CIP]t

The pseudo-first-order reaction rate constant (1/min), represented by kobs, is estimated as the slope of the fitted linear regression between ln([CIP]t/[CIP]0) and reaction time (t). The integration of Equation (3) results in Equation (4), where [CIP]t indicates the concentration of CIP that was measured at a certain time and [CIP]0 represents the initial concentration of CIP.

ln([CIP]t/[CIP]0) = −kobs × t

Quenching analyses were performed to determine the radical species that were produced in the CuO/PDS system. For this purpose, tert-butanol (50 mM), methanol (50 mM), and benzouquinone (0.1 mM) were used as scavengers for *OH, SO4−*, and *OH, and single oxygen (O2−*), respectively.

All degradation experiments were performed in duplicate to assess reproducibility, and error bars in the figures correspond to the standard deviation calculated from the two parallel measurements.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation of Synthesised NMs

The CuO catalyst was synthesised through a rapid and environmentally friendly procedure by chemical precipitation assisted by UI, without the use of toxic solvents or high-temperature calcination, enhancing the sustainability of the process.

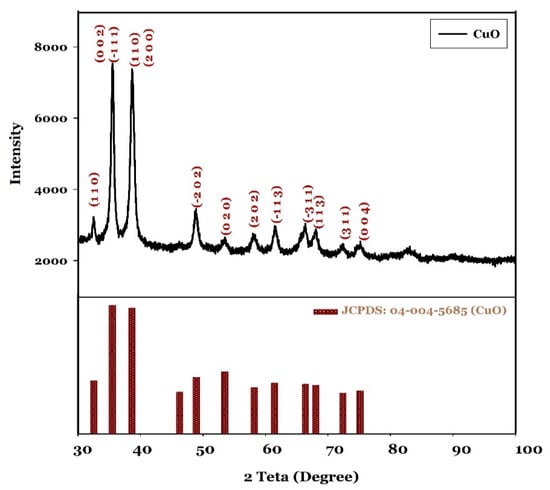

3.1.1. XRD Analysis

Figure 2 illustrated the XRD pattern of the powders produced. All reflection peaks observed at 2θ ranging from 30° to 100° could be indexed by the JCDPS 04-004-5685 card, thus revealing that the powders are composed of tenorite (CuO) with a monoclinic crystalline structure, without secondary phases. Using the Scherrer equation (Equation (1)), the average crystallite size of the precipitated CuO was calculated as 4.16 nm.

Figure 2.

XRD pattern of synthesised CuO.

3.1.2. STEM with EDX Analyses

As shown in Figure 3a,b, where STEM images of the obtained powder particles are presented, the individual CuO particles are very tiny, with a nanometric size and needle-like morphology (average length ≈ 150 nm and width < 50 nm), but very agglomerated. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) confirms the chemical purity of the synthesised material. The spectrum (Figure 3c) shows characteristic peaks for Cu and O. No impurity elements from precursors or contaminants were detected, confirming the successful synthesis of phase-pure copper (II) oxide.

Figure 3.

Morphological and elemental analysis of synthesised CuO nanoparticles: (a,b) STEM images showing needle-like nanoparticle morphology (average length ~ 150 nm, width < 50 nm) with significant agglomeration; (c) EDS confirming elemental composition—only Cu and O peaks detected, verifying phase purity and absence of impurities.

3.1.3. Surface Area Analysis

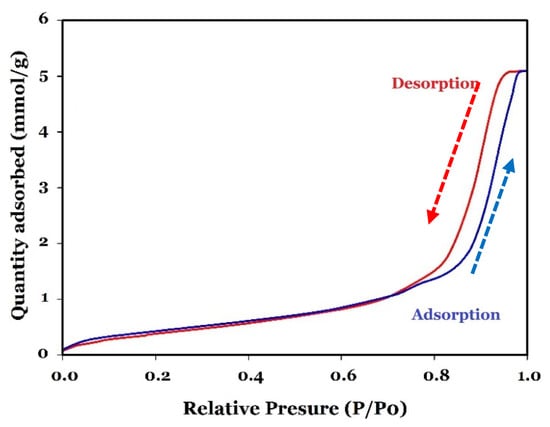

The synthesis process greatly impacts morphology and specific surface area. For instance, Chauhan et al. (2019) [45] prepared different types of CuO by adding, dropwise, 10 mL of 60 mM NaOH to 10 mM copper sulphate solution by three different methods. In the first, the resulting mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature (CPM method). In the second, the mixture was heated in a microwave oven for 5 min (MIM method). In the last one, the resulting mixture after 5 min of stirring was transferred to the Teflon-lined stainless-steel reactor and heated for 3 h at 150 °C (HM method). According to their results, the morphology and size of the different types of synthesised CuO were different, and the specific surface area for CPM, MIM, and HM was 40, 30, and 20 m2/g, respectively [45]. Table 2 presents the results of the BET surface area and porosity analysis of the fabricated CuO. The specific surface area of CuO was about 35.81 m2/g. Figure 4 illustrates the adsorption/desorption isotherms. For the synthesised CuO, the typical hysteretic behaviour of mesoporous materials is identified. According to the IUPAC classification, the hysteresis loop can be categorised as type H1 (IV) based on the form of the adsorption/desorption curves [39]. Using ultrasound in the fabrication process of CuO has increased the specific surface area [46]. Furthermore, the morphology, as well as the surface area, has a great impact on the catalytic performance of CuO [47]. For instance, Xing et al. (2020) employed the hydrothermal method for the fabrication of CuO, which could degrade only 10 mg of CIP in 60 min using 0.5 g/L catalyst and 0.5 mM PDS [25] (see Table 1).

Table 2.

Surface area and porosity analysis.

Figure 4.

Adsorption and desorption isotherms of CuO.

3.1.4. Zeta Potential of CuO

Figure 5 displays the pH dependence of the zeta potential of CuO. The results illustrate that the zero-charge point (ZPC) is around 9.3, which indicates that the surface of the particles is negatively charged when the pH is above 9.3 and positively charged when the pH is below 9.3.

Figure 5.

pH dependence on the zeta potential of CuO. The curve shows a zero-point of charge at approximately pH 9.3 (circle), above which the particle surface acquires a net negative charge (orange) and below (bule) which it becomes positively charged.

3.2. Nano-Catalytic Performance Study

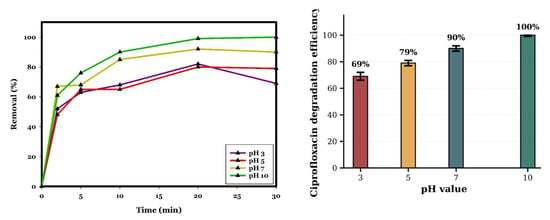

3.2.1. Effect of Initial pH

To study the effect of initial pH on the removal of CIP, the pH was initially adjusted to 3, 5, 7, and 10 by adding NaOH and H2SO4 to a CIP concentration of 20 mg/L, a dosage of CuO of 0.5 g/L, and a PDS concentration of 0.5 mM for a reaction time of 30 min at room temperature. The effect of pH on CIP removal is illustrated in Figure 6. According to the results achieved, the removal of CIP for pH 3, 5, 7, and 10 was 69%, 79%, 90%, and almost 100%, respectively, which indicates that increasing the initial pH will increase the removal efficiency of CIP. The final pH for different starting values (3, 5, 7, and 10) is 5.47, 5.62, 5.62, and 8.75, respectively. The finding of this study is confirmed by a study by Deng et al. (2019), where the best pH for the degradation of CIP (5 mg/L) by nano-ordered mesoporous Co3O4 (0.1 g/L) and PMS (1 mM) over 60 min at room temperature was 9, achieving almost 95% removal of CIP [2], according to Table 1, although in the literature, there are some studies that show the best pH for the removal of CIP by catalytic systems is acidic or neutral pH. For instance, Wang et al. (2021) studied the degradation of CIP (10 mg/L) by nano-Bi1−xSrxFeO3 (1 g/L) and PDS (1 mM) over 60 min, obtaining 95% degradation of CIP at pH 6 [16], and Noor S. Shah et al. (2019) could degrade almost 95% of CIP (10 mg/L) with nZVMn (1 g/L) and PDS (50 mg/L) at pH 2 for 80 min [8]. According to the findings of this study, by increasing the initial pH, the degradation efficiency of CIP on the CuO/PDS system increased because the pHpzc of CuO is 9.3, indicating that the surface transitions from protonated (≡Cu–OH2+) below pH 9.3 to deprotonated (≡Cu–O−) above this value. At pH 10, the dominance of ≡Cu–O− groups increases the electron density, which helps electron transfer from surface oxygen atoms to the O–O bond of S2O82−, improving its reductive cleavage into SO4−* (Equations (11) and (12)) [25]. This mechanism is particularly notable in metal-oxide catalysts, where deprotonated surface hydroxyls act as electron donors. The negatively charged CuO surface at pH 10 increases the activation of PDS by preventing the sulphate by-product (SO42−), so avoiding product accumulation and maintaining the availability of the catalytic sites. Alkaline conditions also stabilise Cu3+ via hydroxide complexation, hence enhancing the Cu2+/Cu3+ redox cycle, which has been reported to be especially effective in activation [17,25]. Homogeneous base-catalysed PDS breakdown is relevant at a pH above 9, because HO2− intermediates react with PDS to create both SO4−* and *OH radicals [17,48,49]. This synergises with heterogeneous CuO activation, explaining the strong contribution of O2•− observed in our quenching results. Under acidic conditions, the catalytic performance will be decreased because (i) the protonated surface has reduced electron-donating capacity, (ii) the adsorption of PDS is hindered, and (iii) SO4−* and *OH are scavenged by the excess of H+ [17]. Although CIP has a greater negative charge at pH 10, which can reduce electrostatic attraction to anionic radicals, the increased oxidative potential of SO4−* and the non-electrostatic electron-transfer reactivity of O2−*promote effective transfer [50,51,52].

Figure 6.

Influence of initial pH on CIP degradation in the CuO/PDS system. The line plot shows the temporal degradation profiles, and the accompanying bar chart presents the removal efficiencies at 30 min for each evaluated pH value. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. Reaction conditions: [CIP]0 = 20 mg/L; CuO = 0.5 g/L; PDS = 0.5 mM; room temperature. Data represent mean values of duplicate experiments.

At pH 3, the percentage of the CIP removal increased within the first 20 min, reaching 82%. But, after this point, the removal efficiency decreased slightly to 69% at 30 min. This phenomenon can be explained by the accumulation of intermediates that scavenge reactive species. On the other hand, hydrogen ions act as scavengers of sulphate and hydroxyl radicals under acidic conditions [17].

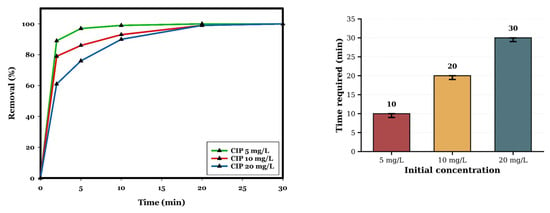

3.2.2. Effect of CIP Concentration

The influence of the concentration of the contaminant on the removal process of CIP using CuO (0.5 g/L) and PDS (0.5 mM) at pH 10 and room temperature was studied. As shown in Figure 7, different concentrations of CIP (5, 10, and 20 mg/L) were completely degraded in 10, 20, and 30 min, respectively. As the concentration of CIP increased, the removal efficiency decreased because the screening effect caused by the CIP molecules reduced the reach of the radicals generated in the CuO/PDS system throughout the entire solution [9]. Furthermore, by increasing the initial concentration of CIP, more intermediates will be produced in comparison with the lowest initial concentration of CIP (5 mg/L), so these intermediates compete with CIP molecules to react with limited reactive oxygen species (ROS) or active sites on the catalyst surface; therefore, they can decrease the efficiency of the removal of CIP molecules in the highest concentration [10,11]. Furthermore, higher initial CIP concentrations generate a greater flux of oxidation intermediates (hydroxylated quinolones, piperazine ring-opened products, and carboxylic acids), which compete with parent CIP for the limited pool of radicals and catalyst active sites. Since the catalyst dose (0.5 g/L) and PDS concentration (0.5 mM) remain constant, the finite rate of radical generation becomes the limiting factor. This competitive inhibition by intermediates is a well-documented phenomenon in AOPs [10,52]. Additionally, at high substrate concentrations, saturation of CuO active sites may occur, limiting the rate of PDS adsorption and activation, further constraining radical production [10]. Other studies in the literature confirm that the removal efficiency of CIP decreases at the highest initial concentration [9,10,11]. For instance, Wen et al. (2018) showed that, when increasing the initial concentration of CIP from 10 mg/L to 40 mg/L in the photodegradation process with CeO2–Ag/AgBr, the degradation decreased from 93.05% to 30.90% at 120 min [10].

Figure 7.

Influence of CIP concentration (5, 10, and 20 mg/L) on removal performance in the CuO/PDS system. The line plot shows the temporal degradation profiles (2.5, 5, 10, 20, and 30 min), and the accompanying bar chart reports the time required to achieve complete removal under each concentration. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. Reaction conditions: CuO = 0.5 g/L; PDS = 0.5 mM; pH 10; room temperature. Data represent mean values of duplicate experiments.

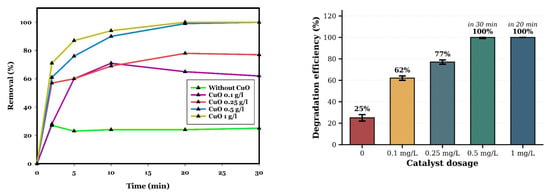

3.2.3. Effect of CuO Dosage

In general, an enhancement in the catalyst dosage rapidly increases the active sites available for the adsorption of CIP molecules and also enhances the decomposition of PDS molecules into more reactive oxygen species (ROSs) that degrade the contaminant by the metallic catalyst of the adsorbed molecules. Thus, the efficiency of CIP removal is directly related to the creation of *OH, O2−*, and SO4−* radicals. Therefore, increasing the dosage of the catalyst is expected to improve the removal efficiency of CIP. CIP removal was investigated at different dosages of CuO using a constant PDS of 0.5 mM, pH of 10, and CIP of 20 mg/L, at room temperature for 30 min. According to Figure 8, the removal rate for 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 g/L of CuO is 25%, 62%, 77%, and 100% for 30 min and 100% for 20 min, respectively. This result is consistent with previous studies in the literature [8,22]. For instance, Jawad et al. (2018) increased the degradation efficiency of phenol from 5% to 100% by increasing the dosage of the CuOx@Co-LDH catalyst from 0 to 0.4 g/L [50].

Figure 8.

Influence of CuO dosage on CIP removal in the CuO/PDS system. The line plot illustrates the temporal removal profiles, while the accompanying bar chart reports the CIP removal efficiencies at 30 min for each CuO dosage. Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. Complete removal was achieved at CuO loadings of 0.5 g L−1 (30 min) and 1.0 g L−1 (20 min). Reaction conditions: [CIP]0 = 20 mg/L; PDS = 0.5 mM; pH 10; room temperature. Data represent mean values of duplicate experiments.

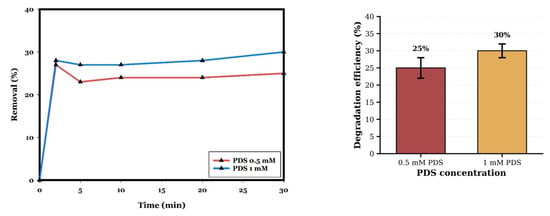

3.2.4. Effect of PDS Concentration

To evaluate the contribution of non-catalytic PDS oxidation, control experiments without CuO were performed at different PDS concentrations. As illustrated in Figure 9, PDS concentration affects the removal of contaminant when the CIP is 20 mg/L and pH is 10, without a catalyst, at room temperature for 30 min. By increasing the PDS concentration from 0.5 mM to 1 mM, the degradation efficiency increased from 25% to 30%. Thereby, by increasing the initial concentration of PDS, the efficiency of CIP removal is improved because S2O82− is the source of SO4−* and *OH in the CuO/PDS system, so the increase in the amount of SO4−* and *OH generated results in increased exposure to CIP molecules [5,8,50]. The slight improvement in the removal of CIP with an increasing concentration of PDS (25% at 0.5 mM improves to 30% at 1.0 mM) in the absence of a catalyst indicates that direct PDS oxidation of CIP is kinetically limited at room temperature. PDS is a relatively stable oxidant agent that requires activation to generate reactive radicals. The negligible degradation (<30%) contrasts sharply with the 100% removal achieved in the CuO/PDS system under the same conditions (0.5 mM PDS, pH 10, 30 min; Figure 8), confirming that CuO acts as an essential activator.

Figure 9.

Influence of PDS concentration on CIP degradation in the absence of CuO catalyst (control experiments). The line plot illustrates the temporal degradation profiles, while the accompanying bar chart reports the removal efficiencies obtained at 30 min for 0.5 mM and 1.0 mM PDS (25% and 30%, respectively). Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. Low removal efficiency (<30%) demonstrates that CuO catalysis is essential for effective PDS activation. Reaction conditions: CIP = 20 mg/L; pH 10; room temperature; 30 min. Data represent mean values of duplicate experiments.

Although continuing to increase the PDS concentration above 0.5 mM in the complete system could theoretically improve radical generation, two opposing factors limit its assistance: (i) saturation of CuO active sites, as the catalyst surface has limited capacity for adsorption and activation of PDS, and (ii) radical–radical recombination reactions at high oxidant concentrations, including self-quenching of SO4−* by excess PDS (Equation (5)). Therefore, from both efficiency and sustainability perspectives, 0.5 mM PDS was selected as optimal [16,22,49,53].

SO4−* + S2O8−2 → S2O8·− + SO42−

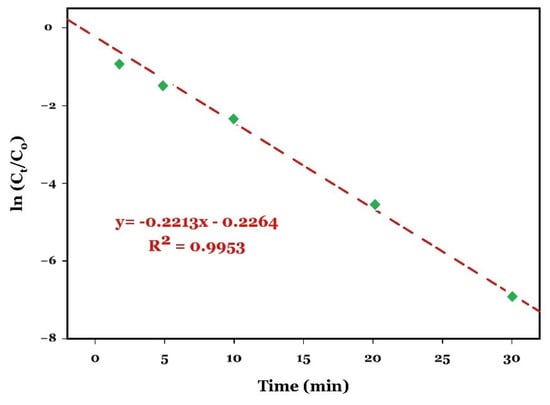

The developed CuO/persulfate system shows superior performance compared to previously reported catalysts made from transition metal oxide (Table 1). Our system achieves a mass removal rate of 0.67 mg/L·min for the degradation of CIP, about two times higher than similar CuO-based systems operating at lower pollutant concentrations and acidic pH [25]. This improved performance is because of the high specific surface area (35.81 m2/g), optimal crystallite size (4.16 nm), and mesoporous structure (Type IV isotherm, Figure 4) of the UI-synthesised CuO, which facilitates pollutant and oxidant diffusion to active sites. Moreover, the green synthesis method, which does not need high-temperature calcination, offers additional sustainability advantages, decreasing energy consumption compared to conventional hydrothermal methods, which usually require 200–600 °C calcination [25,42,43,44], while at the same time achieving superior catalytic performance. The combination of rapid degradation kinetics (kobs = 0.2213 min−1), operation under alkaline conditions, and a sustainable synthesis method in this system makes it a promising platform for practical water treatment applications.

Beyond kinetic performance, the CuO/PDS system shows critical practical advantages not addressed in previous studies. Unlike photocatalytic systems (entries 4–7, 10–12, Table 1) requiring continuous UV-Vis irradiation or sonophotocatalytic processes (entry 11) that require ultrasonic energy input, the CuO/PDS system operates without external energy sources, greatly reducing operational costs and complexity for field application. The generation of multiple reactive oxygen species (SO4−*, O2−*, *OH) provides synergistic degradation pathways, contrasting with systems dominated by single radical mechanisms such as OM-Co3O4/PMS (entry 8, primarily SO4−*and *OH). The lower oxidant consumption (0.5 mM PDS) compared to ZnO/PDS/ultrasound systems (entry 2, 1.76 mM), as well as its competitive catalyst dosage (0.5 g/L vs. 1 g/L for nZVMn, Bi1−xSrxFeO3), further enhances its economic feasibility. The advantages of energy-free operation, multi-radical generation, and reagent efficiency confirm the CuO/PDS system as a scalable and cost-effective technology bridging laboratory innovation with industrial water treatment implementation.

3.2.5. Kinetics Study

The removal of CIP under the optimum conditions (20 mg/L CIP, 0.5 mM PDS, 0.5 g/L CuO, pH 10, room temperature) was assessed as a function of time (Figure 8, blue curve). The degradation data were fitted to the pseudo-first-order kinetic model Equation (4), and the corresponding linear fitting plot of ln([CIP]t/[CIP]0) versus time is shown in Figure 10. The plot demonstrates an excellent correlation (R2 = 0.9953) and shows an apparent rate constant kobs of 0.2213 min−1.

Figure 10.

Pseudo-first-order plot for CIP removal by the CuO/PDS system.

3.2.6. TOC Removal of CIP

Researchers will usually investigate TOC removal to study the reduction in mass concentration of target organic pollutants in aquatic media and to assess the potential of treatment technology for contaminants [8]. In this study, TOC removal of CIP by the CuO/PDS system was investigated. With CIP 20 mg/L, CuO 0.5 g/L, PDS 0.5 mM, and pH 10 at room temperature, 49% removal was achieved at a reaction time of 30 min. TOC removal is a complex process that is performed in several steps, so it requires a long time for the treatment process [54]. For instance, in a study by Noor S. Shah et al. (2019), the amount of TOC removal by CIP (10 mg/L), [Mn0]0 1.0 g/L, and [S2O82−]0 50 mg/L, was 10% during 80 min of treatment time, while the removal of CIP was 95%. They could increase TOC removal to 56% in 960 min reaction time by CIP (20 mg/L), [Mn0]0 2.0 g/L, and [S2O82−]0 100 mg/L [8].

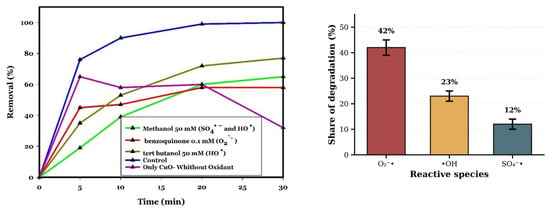

3.2.7. Reaction Mechanism

To study the origin of the excellent efficiency of the CuO/PDS system in the removal of CIP, quenching experiments introducing different scavengers to the reactor to trap the various radicals have been performed under the following conditions: CIP 20 mg/L, pH 10, CuO 0.5 g/L, PDS 0.5 mM, room temperature, time 30 min. According to the literature [9,55,56], methanol (MeOH) has been used as a scavenger of both radicals of SO4−* and *OH because it has a high rate constant with (k SO4−* = 3.2 × 106 M−1 s−1) and (k *OH = 9.7 × 108 M−1 s−1) [57], while tertiary butanol (TBA) has been used as an effective quenching agent for *OH with k*OH = ((3.8–7.6) × 108 M−1 s−1), and benzoquinone (BQ) has been used as an effective quenching agent for O2−* with (k O2−* = 2 × 10−5 M−1 s−1) [58]. This is a non-photocatalytic process operating at room temperature without light irradiation. Therefore, photogenerated electron–hole pairs (e−/h+) are not involved. The mechanism relies on electron transfer from Cu species to PDS, Cu+/Cu2+/Cu3+ redox cycling, and base-catalysed PDS decomposition. As Figure 11 illustrates, the degradation rate of CIP is decreased by adding MeOH 50 mM, TBA 50 mM, and BQ 0.1 mM from 100% (without any scavenger agent) to 65%, 77%, and 58%, respectively. The present study indicates a major role of O2−* with 42%, then *OH and SO4−* with 23% and 12%, respectively, in metal catalytic removal of CIP. Furthermore, in the condition of CIP 20 mg/L, CuO 0.5 g/L, and pH 10, without any oxidant, the degradation is about 32%, which may be due to the adsorption and production of oxy radicals such as O2−* and *OH, which are produced in CuO water suspension [59].

Figure 11.

Reactive oxygen species identification via radical scavenging experiments. The line plot compares CIP degradation in the presence of selective scavengers: control (no scavenger); methanol (MeOH, 50 mM, scavenges SO4−* and *OH); tert-butanol (TBA, 50 mM, scavenges *OH); and benzoquinone (BQ, 0.1 mM, scavenges O2−*) relative to control (no scavenger). The accompanying bar chart presents the quantified contribution of each radical species to the overall degradation process. Results indicate O2−*as the dominant radical (42% contribution), followed by *OH (23%) and SO4−* (12%). Error bars represent the standard deviation of duplicate measurements. Reaction conditions: [CIP]0 = 20 mg/L; CuO = 0.5 g/L; PDS = 0.5 mM; pH 10; room temperature. Data represent mean values of duplicate experiments.

The reaction of CuO with PDS with high oxidation potential can produce O2−* via the decomposition of PDS by cleavage of the S-O bond. Therefore, O2−* can be produced from the interaction of PDS with Cu2+/3+ according to Equations (6) and (7). Also, Cu+3 can be produced according to Equation (12). On the other hand, O2−* and SO4−* can be produced in alkaline pH activation of PDS according to Equations (8) and (9). So, for the degradation of CIP, superoxide radicals have a great impact in basic conditions due to producing a high amount of O2−* in alkaline pH [17,25]. The dominance of O2−* under alkaline conditions (pH 10) can be explained by the enhanced formation of HO2− intermediates from PDS, which is disproportionate to the amount of O2−* at high pH, as seen in Equations (8) and (9). Additionally, Cu (II)/Cu (III) redox cycling facilitates single-electron transfer to PDS, generating O2−* rather than SO4−* in strongly basic media, shown in Equations (6) and (7) [17]. While Cu3+ has been proposed as a transient intermediate in alkaline persulfate systems due to stabilisation by hydroxide ligands, direct spectroscopic evidence (e.g., operando XPS, EPR) is required to confirm its formation under our conditions. The mechanism may alternatively predominantly involve Cu+/Cu2+ redox cycling, which is well-documented in copper-based AOPs [25].

Cu2+ + S2O82− + 2H2O → 2HSO4− + O2−* + 2H+

Cu3+ + S2O82− + 2H2O → 2HSO4− + O2−* + 2H+

S2O82− + H2O → 2SO42− + HO2− + H+

S2O82− + HO2− → SO42− + SO4−* + H+ + O2−*

Also, *OH can be produced by the reaction of SO4−* and OH−, according to Equation (10), although SO4−* can be produced by one-electron transfer from Cu+/2+ to PDS according to Equations (11) and (12) [17,25,60]:

SO4−* + OH− → SO42− + *OH

Cu(I) + S2O82→Cu (II) + SO42− + SO4−*

Cu(II) + S2O82− → Cu (III) + SO42− + SO4−*

The formation of Cu3+ is proposed based on precedent set in the literature, but requires confirmation by in situ spectroscopic methods. As a result, CIP can be degraded to CO2 and H2O, as well as intermediates, according to Equation (13):

SO4−*/O2−*/*OH + CIP →CO2 + H2O + intermediate

It should be pointed out that quenching experiments have some limitations because of the probable side reactions and non-selectivity of scavengers. The results of this study are in line with recent EPR-based studies. For instance, Du et al. (2017) [61] and Wang and Wang (2018) [17] verified the generation of O2−*, *OH, and SO4−* radicals in the CuO/PDS systems; furthermore, He et al. (2024) [62] indicated the involvement of copper ions as an additional oxidising species. These reports support our proposed mechanism. Based on the identified reactive species and established CIP oxidation chemistry, a probable degradation pathway can be proposed. Initial attack by sulphate and superoxide radicals occurs at electron-rich sites, including the piperazine ring and quinolone moiety. Common transformation products reported in similar systems include initial hydroxylation of the quinolone ring (m/z ≈ 348), oxidation and cleavage of the piperazine moiety (m/z ≈ 306–316), and defluorination and side-chain scission (m/z ≈ 329, 316), followed by quinolone ring opening to smaller carboxylic acids (m/z ≈ 263, 230, 211) and eventual mineralisation to CO2 and H2O [63,64]. This supports the interpretation of the current study that O2−*and SO4−*/*OH radicals act synergistically to drive the sequential oxidation, ring cleavage, and defluorination of CIP in the CuO/PDS system. The 49% TOC removal achieved after 30 min indicates substantial, though incomplete, mineralisation. Defluorination and piperazine ring opening are considered critical steps toward detoxification, as these modifications reduce antibacterial activity and ecotoxicity. However, a comprehensive toxicity evaluation using standardised bioassays is essential to validate environmental safety.

Furthermore, catalyst reusability and metal leaching are important for practical applications. Copper leaching may occur during reaction, potentially contributing to both heterogeneous (surface-catalysed) and homogeneous (dissolved Cu-mediated) PDS activation. Under alkaline conditions (pH 10), Cu solubility is limited by Cu(OH)2 precipitation. Similar CuO-based systems have shown satisfactory stability and reusability in the AOP process. For example, Zhang et al. (2021) reported that CuO maintained 95% of its catalytic activity after 11 consecutive cycles in the degradation of an organic pollutant (4-nitrophenol) with minimal structural change [65]. Additionally, green-synthesised CuO nanoparticles showed a stable ion release profile, which contributed to their biocompatibility and reduced toxicity compared to chemically synthesised counterparts [66,67]. For instance, Xing et al. (2020) observed less than 3 μmol/L of dissolved Cu under alkaline conditions in the CuO–PS–bicarbonate system during CIP removal, and the catalyst maintained its efficiency after five successive cycles, indicating the low secondary pollution risk and reusability of CuO [25]. Therefore, heterogeneous catalysis predominates. However, even trace dissolved Cu2+ can participate in redox cycling, generating radicals through homogeneous pathways. These findings suggest that our ultrasonically synthesised CuO would exhibit comparable performance and have potential for real-world application, because the robust crystalline structure, high surface area, and mesoporous morphology of our CuO suggest potential for good stability. However, experimental confirmation through multi-cycle testing is essential to validate the (i) maintenance of catalytic activity over ≥5 cycles, (ii) structural integrity via post-reaction characterisation, (iii) copper leaching quantification, and (iv) identification of deactivation mechanisms. These studies will be prioritised in future work.

4. Conclusions

This research improves persulfate-based advanced oxidation processes by an integrated approach that combines sustainable synthesis, excellent catalytic efficiency, and mechanistic innovation. Ultrasonically synthesised CuO nanoparticles, produced via an energy-efficient method without high-temperature calcination (60 °C, 45 min), displayed excellent efficiency for ciprofloxacin degradation, achieving 100% removal of 20 mg/L CIP in 30 min under alkaline conditions (pH 10) with minimal catalyst (0.5 g/L) and oxidant (0.5 mM PDS) concentrations. The results indicate approximately a twofold improvement in mass removal rate over the previous CuO/persulfate systems operating at acidic/neutral pH with lower pollutant concentrations.

The mechanistic analysis confirmed pH-dependent radical speciation, with O2−* leading (42% contribution) in alkaline conditions, in contrast to SO4−*-dominated mechanisms at acidic pH. This effect was directly associated with the measured point of zero charge (pHpzc = 9.3) and surface charge inversion, highlighting the impact of catalyst surface chemistry on radical generation mechanisms. The incorporation of green synthesis principles improved catalytic efficiency under alkaline conditions, and mechanistic insights addressed critical gaps in persulfate-based water treatment.

While copper leaching was not measured, exciting developments in the literature indicate minimal Cu release under alkaline conditions, with catalysis usually occurring via heterogeneous pathways. Although indicating effective CIP degradation, verification for practical application requires the following: (i) a multi-cycle catalyst reusability study (≥5 cycles) with structural characterisation and quantification of copper leaching, (ii) LC-MS/MS identification of transformation products and validation of degradation pathways, (iii) ecotoxicity assessment of treated effluent using standardised bioassays, (iv) quantification of copper leaching mechanisms under various conditions, (v) and EPR spectroscopy for direct radical detection. Advanced characterisation methods will provide absolute confirmation of copper oxidation states and transient intermediates in the catalytic cycle.

This study provides an innovative CuO-based persulfate activation system that offers high catalytic efficiency, sustainable synthesis, and a detailed mechanistic explanation. The proposed method facilitates the rapid degradation of emerging organic pollutants using low chemical dosages, enhancing awareness and practical developments in AOP-based wastewater treatment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and I.C.; methodology, M.E.V.C. and I.C.; software, M.K. and J.D.; validation, M.E.V.C. and I.C.; formal analysis, M.K., M.E.V.C. and I.C.; investigation, M.K.; resources, M.E.V.C. and I.C.; data curation, M.K. and J.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; writing—review and editing J.D., M.E.V.C. and I.C.; visualisation, M.K. and J.D.; supervision, M.E.V.C. and I.C.; project administration, I.C.; funding acquisition, M.E.V.C. and I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia I.P.—under the project/grant UID/50006 + LA/P/0094/2020 (doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0094/2020). This work was also developed within the scope of the project CICECO-Aveiro Institute of Materials, UIDB/50011/2020, UIDP/50011/2020, and LA/P/0006/2020, financed by national funds through the FCT/MCTES (PIDDAC). Thanks are also due to FCT for the doctoral scholarship no. SFRH/BD/140873/2018 and COVID/BD/152992/2022 for the first author. J.D. acknowledges national funds from FCT-Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within CEECINST/00102/2018, LA/P/0037/2020, UIDP/50025/2020, and UIDB/50025/2020 of the Associate Laboratory Institute of Nanostructures, Nanomodelling, and Nanofabrication-i3N.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are due to CESAM—Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies and CICECO-Aveiro Institute of Materials for the financial support. The Authors also thanks Mohammadreza Kamali.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mao, W.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Bai, Y.; Guan, Y. Facile assembled N, S-codoped corn straw biochar loaded Bi2WO6 with the enhanced electron-rich feature for the efficient photocatalytic removal of ciprofloxacin and Cr(VI). Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Xu, M.; Feng, S.; Qiu, C.; Li, X.; Li, J. Iron-doped ordered mesoporous Co3O4 activation of peroxymonosulfate for ciprofloxacin degradation: Performance, mechanism and degradation pathway. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 658, 343–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Kamali, M.; He, X.; Khalaj, M.; Xia, Y. Catalytic Ozonation of the Secondary Effluents from the Largest Chinese Petrochemical Wastewater Treatment Plant—A Stability Assessment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abelenda-alonso, G.; Carratalà, J. Antibiotic prescription during the COVID-19 pandemic: A biphasic pattern. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 41, 1371–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakootian, M.; Ahmadian, M. Ciprofloxacin removal by electro-activated persulfate in aqueous solution using iron electrodes. Appl. Water Sci. 2019, 9, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, A.; Khataee, A.; Karaca, S. Photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin by synthesized TiO2 nanoparticles on montmorillonite: Effect of operation parameters and artificial neural network modeling. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2015, 409, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvamani, P.S.; Vijaya, J.J.; Kennedy, L.J.; Mustafa, A.; Bououdina, M.; Sophia, P.J.; Ramalingam, R.J. Synergic effect of Cu2O/MoS2/rGO for the sonophotocatalytic degradation of tetracycline and ciprofloxacin antibiotics. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 4226–4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.S.; Khan, J.A.; Sayed, M.; Khan, Z.U.H.; Ali, H.S.; Murtaza, B.; Khan, H.M.; Imran, M.; Muhammad, N. Hydroxyl and sulfate radical mediated degradation of ciprofloxacin using nano zerovalent manganese catalyzed S2O82−. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 356, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, A.; Rajasekaran, P.; Selvakumar, K.; Arunpandian, M.; Kaviyarasu, K.; Bahadur, S.A.; Swaminathan, M. Visible active reduced graphene oxide-BiVO4-ZnO ternary photocatalyst for efficient removal of ciprofloxacin. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2020, 233, 115996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.J.; Niu, C.G.; Zhang, L.; Liang, C.; Guo, H.; Zeng, G.M. Photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin by a novel Z-scheme CeO2–Ag/AgBr photocatalyst: Influencing factors, possible degradation pathways and mechanism insight. J. Catal. 2018, 358, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Tang, L.; Feng, C.; Zeng, G.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Y.; Peng, B.; Feng, H. Construction of plasmonic Ag modified phosphorous-doped ultrathin g-C3N4 nanosheets/BiVO4 photocatalyst with enhanced visible-near-infrared response ability for ciprofloxacin degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 758–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdar, A.; Rahdar, S.; Askari, F.; Ahmadi, S.; Shahraki, H.; Mohammadi, L.; Sivasankarapillai, V.S.; Kyzas, G.Z. Effectiveness of graphene quantum dot nanoparticles in the presence of hydrogen peroxide for the removal of ciprofloxacin from aqueous media: Response surface methodology. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 2124–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Estrada, A.C.; Asekh, S.; Trindade, T.; Aminabhavi, T.M.; Sobolev, N.A.; Costa, M.E.V.; Dewil, R.; Capela, I. Mechanistic analysis of photocatalytic transformation of naphthalene using a nano-O-doped-g-C3N4-CuO n-p heterojunction. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 195, 106794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Xue, Y.; Khalaj, M.; Laats, B.; Teunckens, R.; Verbist, M.; Costa, M.E.V.; Capela, I.; Appels, L.; Dewil, R. ZnO/γ-Fe2O3/Bentonite: An Efficient Solar-Light Active Magnetic Photocatalyst for the Degradation of Pharmaceutical Active Compounds. Molecules 2022, 27, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Huang, B.; Gu, L.; Xiong, D.; Lai, C.; Tang, J.; Pan, X. Stimulated dissolved organic matter by electrochemical route to produce activity substances for removing of 17α-ethinylestradiol. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 780, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gao, S.; Zhu, J.; Xia, X.; Wang, M.; Xiong, Y. Enhanced activation of peroxydisulfate by strontium modified BiFeO3 perovskite for ciprofloxacin degradation. J. Environ. Sci. 2021, 99, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S. Activation of persulfate (PS) and peroxymonosulfate (PMS) and application for the degradation of emerging contaminants. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1502–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wan, Y.; Peng, J.; Yao, G.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, B. Efficient degradation of atrazine by LaCoO3/Al2O3 catalyzed peroxymonosulfate: Performance, degradation intermediates and mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 796–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Ge, Y.; Tan, C.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, K. Degradation of ciprofloxacin using α-MnO2 activated peroxymonosulfate process: Effect of water constituents, degradation intermediates and toxicity evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 330, 1390–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Srivastava, V.; Ambat, I.; Safaei, Z.; Sillanpää, M. Degradation of Ibuprofen by UV-LED/catalytic advanced oxidation process. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 31, 100808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Cheng, M.; Zhong, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Liang, Q. Iron-mediated activation of persulfate and peroxymonosulfate in both homogeneous and heterogeneous ways: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 384, 123265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwegbe, C.A.; Ahmadi, S.; Rahdar, S.; Ramazani, A.; Mollazehi, A.R. Efficiency comparison of advanced oxidation processes for ciprofloxacin removal from aqueous solutions: Sonochemical, sono-nano-chemical and sono-nano-chemical/persulfate processes. Environ. Eng. Res. 2020, 25, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Huang, B.; Wang, H.; Yuan, X.; Jiang, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, G. Facile construction of novel direct solid-state Z-scheme AgI/BiOBr photocatalysts for highly effective removal of ciprofloxacin under visible light exposure: Mineralization efficiency and mechanisms. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 522, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Niu, J.; Zhao, J.; Wei, Y.; Yao, B. Photocatalytic degradation of ciprofloxacin using Zn-doped Cu2O particles: Analysis of degradation pathways and intermediates. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 374, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Li, W.; Liu, B.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Y. Removal of ciprofloxacin by persulfate activation with CuO: A pH-dependent mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 382, 122837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaj, M.; Kamali, M.; Khodaparast, Z.; Jahanshahi, A. Copper-based nanomaterials for environmental decontamination—An overview on technical and toxicological aspects. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 148, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Davarazar, M.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Single precursor sonochemical synthesis of mesoporous hexagonal-shape zero-valent copper for effective nitrate reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 384, 123359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhao, Z.; Liang, Z.; Liu, J.; Shi, W.; Cui, F. Efficient As(III) removal by magnetic CuO-Fe3O4 nanoparticles through photo-oxidation and adsorption under light irradiation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 495, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Smita, K.; Cumbal, L.; Debut, A.; Pathak, R.N. Sonochemical synthesis of silver nanoparticles using starch: A comparison. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2014, 2014, 784268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Costa, M.E.V.; Otero-Irurueta, G.; Capela, I. Ultrasonic irradiation as a green production route for coupling crystallinity and high specific surface area in iron nanomaterials. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 211, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Coles, S.R.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Błaszczyński, J.; Słowiński, R.; Varma, R.S.; Kirwan, K. Robustness analysis of a green chemistry-based model for the classification of silver nanoparticles synthesis processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 938–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Coles, S.R.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Błaszczyński, J.; Słowiński, R.; Varma, R.S.; Kirwan, K. A green chemistry-based classification model for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles. J. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 2825–2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Yang, J.; Ma, H.; Su, S.; Chang, Q.; Komarneni, S. Green synthesis of nano-muscovite and niter from feldspar through accelerated geomimicking process. Appl. Clay Sci. 2018, 165, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikoofar, K.; Dizgarani, S.M. ZrOCl2·8H2O@nano SiO2: A green and recyclable catalyst for the synthesis of benzimidazoles. Iran. Chem. Commun. 2018, 6, 62–69. [Google Scholar]

- Behrouz, S.; Soltani Rad, M.N.; Piltan, M.A. Ultrasound promoted rapid and green synthesis of thiiranes from epoxides in water catalyzed by chitosan-silica sulfate nano hybrid (CSSNH) as a green, novel and highly proficient heterogeneous nano catalyst. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 40, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckelman, M.J.; Zimmerman, J.B.; Anastas, P.T. Toward green nano: E-factor analysis of several nanomaterial syntheses. J. Ind. Ecol. 2008, 12, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakhaei, A.; Davoodnia, A.; Yadegarian, S. Nano-Fe3O4@ZrO2-SO3H as highly efficient recyclable catalyst for the green synthesis of fluoroquinolones in ordinary or magnetized water. Iran. J. Catal. 2018, 8, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, J.H.; Suslick, K.S. Applications of ultrasound to the synthesis of nanostructured materials. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 1039–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M.; Khalaj, M.; Costa, M.E.V.; Capela, I.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Optimization of kraft black liquor treatment using ultrasonically synthesized mesoporous tenorite nanomaterials assisted by Taguchi design. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 401, 126040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalaj, M.; Kamali, M.; Costa, M.E.V.; Capela, I. Green synthesis of nanomaterials—A scientometric assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagi, B.; Faggian, A.; McCann, P. Long and Short Distance Migration in Italy: The Role of Economic, Social and Environmental Characteristics. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2011, 6, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, W.T.R.S.; Amaraweera, T.H.N.G.; Jayathilaka, K.M.D.C.; Kumara, L.S.R.; Seo, O. Energy materials Engineering electron density and structural properties of CuO anode material via calcination and in situ synchrotron XRD for enhanced lithium—Ion battery performance. J. Mater. Sci. 2025, 60, 25386–25408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xing, S. Degradation of ciprofloxacin by persulfate activation with CuO supported on Mg Al layered double hydroxide. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravele, M.P.; Oyewo, O.A.; Ramaila, S.; Mavuru, L.; Onwudiwe, D.C. Results in Engineering Facile synthesis of copper oxide nanoparticles and their applications in the photocatalytic degradation of acyclovir. Results Eng. 2022, 14, 100479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, M.; Sharma, B.; Kumar, R.; Chaudhary, G.R.; Hassan, A.A.; Kumar, S. Green synthesis of CuO nanomaterials and their proficient use for organic waste removal and antimicrobial application. Environ. Res. 2019, 168, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karuppaiah, P.; Gowthaman, N.S.K.; Balakumar, V.; Shankar, S.; Lim, H.N. Ultrasonic synthesis of CuO nanoflakes: A robust electrochemical scaffold for the sensitive detection of phenolic hazard in water and pharmaceutical samples. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 58, 104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Deng, W.; Wang, Q.; Lin, X.; Gong, L.; Liu, C.; Xiong, W.; Nie, X. An efficient chemical precipitation route to fabricate 3D flower-like CuO and 2D leaf-like CuO for degradation of methylene blue. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 1391–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Wang, Z.; Deling; Zhang, Y.; Qi, J.; Rao, Y.; Lu, G.; Li, B.; Wang, K.; Yin, K. Enhanced photocatalytic performance of BiVO4 for degradation of methylene blue under LED visible light irradiation assisted by peroxymonosulfate. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2020, 15, 2470–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Liu, X.; Ma, J.; Lin, C.; Li, X.; Zhang, H. Activation of peroxymonosulfate by base: Implications for the degradation of organic pollutants. Chemosphere 2016, 151, 280–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawad, A.; Lang, J.; Liao, Z.; Khan, A.; Ifthikar, J.; Lv, Z.; Long, S.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Z. Activation of persulfate by CuOx@Co-LDH: A novel heterogeneous system for contaminant degradation with broad pH window and controlled leaching. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 335, 548–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozi, R.; Gholami, M.; Farzadkia, M.; Jonidi Jafari, A. Degradation of ciprofloxacin by CuFe2O4/GO activated PMS process in aqueous solution: Performance, mechanism and degradation pathway. Int. J. Environ. Anal. Chem. 2022, 102, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Chen, X.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Wen, S.; Guo, J.; Shi, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, R.; Xu, Y. Activation of persulfate by biochar-supported sulfidized nanoscale zero-valent iron for degradation of ciprofloxacin in aqueous solution: Process optimization and degradation pathway. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 10950–10966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, J.; Xu, W.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Tan, X.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, P.; Du, L.; Li, M. Activation of persulfate by nanoscale zero-valent iron loaded porous graphitized biochar for the removal of 17β-estradiol: Synthesis, performance and mechanism. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 588, 776–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.A.; He, X.; Khan, H.M.; Shah, N.S.; Dionysiou, D.D. Oxidative degradation of atrazine in aqueous solution by UV/H2O2/Fe2+, UV/S2O82−/Fe2+ and UV/HSO5−/Fe2+ processes: A comparative study. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 218, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Zong, F.; Xu, W.; Zhang, X.; Fang, Z. A multipath peroxymonosulfate activation process over supported by magnetic CuO-Fe3O4 nanoparticles for efficient degradation of 4-chlorophenol. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 1662–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binh, T.; Doong, R.; Huang, C.P.; Chen, C.; Dong, C. Activation of persulfate by CoO nanoparticles loaded on 3D mesoporous carbon nitride (CoO@meso-CN) for the degradation of methylene blue (MB). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 675, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Wang, X.; Fu, L.; Peng, X.; Pan, C.; Mao, Q.; Wang, C.; Yan, J. Science of the Total Environment Nonradicals induced degradation of organic pollutants by peroxydisulfate (PDS) and peroxymonosulfate (PMS): Recent advances and perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 765, 142794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fónagy, O.; Szabó-Bárdos, E.; Horváth, O. 1,4-Benzoquinone and 1,4-hydroquinone based determination of electron and superoxide radical formed in heterogeneous photocatalytic systems. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 407, 113057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applerot, G.; Lellouche, J.; Lipovsky, A.; Nitzan, Y.; Lubart, R.; Gedanken, A.; Banin, E. Understanding the antibacterial mechanism of CuO nanoparticles: Revealing the route of induced oxidative stress. Small 2012, 8, 3326–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhuang, X.; Ahmad, S.; Lee, T.; Si, H.; Cao, C.; Ni, S.-Q. Sulfate radicals based heterogeneous peroxymonosulfate system catalyzed by CuO-Fe3O4-Biochar nanocomposite for bisphenol A degradation. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 41, 102078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Zhang, Y.; Hussain, I.; Huang, S.; Huang, W. Insight into reactive oxygen species in persulfate activation with copper oxide: Activated persulfate and trace radicals. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 313, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Feng, L.; Shi, T.; Ni, F.; Zhao, L.; Lei, Y.; Liu, Y.; Fang, D.; Wei, Z.; Shen, F. Mechanistic insights into the roles of copper in enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation for tetracycline degradation by copper ferrite composite catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 156769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.-S.; Liu, J.; Ou, H.-S.; Wang, L.-L. Degradation of ciprofloxacin by 280 nm ultraviolet-activated persulfate: Degradation pathway and intermediate impact on proteome of Escherichia coli. Chemosphere 2016, 165, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Wang, Z.; Pu, Q.; Li, X.; Cui, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, Y. Identification and Mechanistic Analysis of Toxic Degradation. Toxics 2024, 12, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Meng, Y.; Ning, Y.; Wheatley, A.E.H.; Chai, F. A reusable catalyst based on CuO hexapods and a CuO-Ag composite for the highly efficient reduction of nitrophenols. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 13193–13200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Liu, C.; Qi, K.; Cui, X. Photo-reduced Cu/CuO nanoclusters on TiO2 nanotube arrays as highly efficient and reusable catalyst. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 39695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saif, S.; Tahir, A.; Asim, T.; Chen, Y. Plant mediated green synthesis of CuO nanoparticles: Comparison of toxicity of engineered and plant mediated CuO nanoparticles towards Daphnia magna. Nanomaterials 2016, 6, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).