1. Introduction

Flood forecasting remains a central challenge in hydrology, particularly as extreme events increase in frequency and intensity under changing climatic conditions. Different river systems exhibit distinct hydrological behaviours that influence forecasting difficulty. Snowmelt-dominated mountain rivers (such as those in the Canadian Rockies) demonstrate strong seasonality with rapid melt-driven peaks; rainfall–runoff rivers respond quickly to short-duration storms; monsoon-fed rivers show pronounced intra-annual variability; and regulated rivers are influenced by storage-release patterns from reservoirs. These diverse flow regimes have motivated a wide range of forecasting methods, from conceptual and statistical models to emerging data-driven approaches. Situating flood-flow forecasting within this broader hydrological context provides essential motivation for evaluating different modelling techniques.

A flood forecasting procedure that has recently shown considerable promise is the Prophet model, a generalized additive modeling approach designed for handling complex seasonality and trend components in time series data. Prophet can flexibly incorporate external regressors and non-linear growth patterns, making it suitable for environmental and hydrological applications where multiple climate drivers influence stream flow features that are not incorporated in traditional statistical models such as SARIMAX. This is important because many engineering agencies continue to rely on conventional models like SARIMAX due to their interpretability and long-standing use in operational settings. Previous studies have shown that Prophet achieves accurate flood forecasting by capturing both long-term seasonal dynamics and short-term variability. These results demonstrate capabilities that exceed those of commonly used traditional models, underscoring Prophet’s substantial potential for advancing hydrological prediction [

1].

Taken together, these points highlight the central motivation for this study: while Prophet offers flexibility in modelling nonlinear seasonal behaviour and integrating multiple exogenous drivers, SARIMAX remains widely used in operational hydrology because of its interpretability and established reliability. Consolidating, these contrasting strengths provides a clear rationale for evaluating both methods within a unified forecasting framework.

In parallel, the SARIMAX model remains a widely used statistical approach for time-series forecasting. By explicitly modeling seasonality and incorporating external climatic variables such as precipitation and temperature, SARIMAX provides interpretable and theoretically grounded predictions [

2]. However, SARIMAX often requires careful parameter tuning and assumptions of stationarity, which may limit its flexibility when dealing with non-linearities or abrupt changes in hydrological systems. An accompanying study currently being prepared by the authors examines Prophet’s performance across multiple flood years and highlights the importance of snow water equivalent (SWE) in improving forecast skill under varying hydrological conditions. However, that analysis focused primarily on predictive performance, leaving scope for further investigation of long-term variability and uncertainty quantification.

Accordingly, a comparison between Prophet and SARIMAX is undertaken in this study. By incorporating precipitation, temperature, and SWE as exogenous regressors, and by quantifying both relative error and prediction interval uncertainty, this work provides the first comprehensive evaluation of Prophet against a traditional statistical benchmark.

This paper provides a comparative evaluation of both Prophet and SARIMAX for river flood forecasting for 2013 (an extreme flooding event). The analysis examines both medium-term (15-day ahead) and short-term (3-day ahead) forecasts, assessing performance through quantitative metrics such as MAE, RMSE, and R2, alongside uncertainty bounds. By systematically comparing these two approaches, this study highlights their relative strengths and limitations, offering insights into their applicability for operational flood forecasting and risk management.

1.1. Literature Review

In recent years, the demand for accurate flood forecasting has intensified due to the increasing frequency of extreme weather events and climate variability. Traditional models such as the Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) have long been used in hydrology for its simplicity and ability to capture linear dependencies in time-series data [

2]. However, ARIMA relies on strict assumptions of stationarity and often struggles to capture nonlinear dynamics or complex seasonal variations. The limitations have encouraged the use of more advanced approaches, such as the SARIMAX, which extends ARIMA by incorporating seasonality and external climate predictors [

3,

4].

Alongside SARIMAX, the Prophet model has emerged as a robust alternative [

1]. Prophet decomposes time-series into trend, seasonality, and external effects, while also handling missing data and irregular time steps [

5]. Its adaptability has been demonstrated in environmental applications, including temperature and air quality forecasting, where irregular seasonalities and abrupt shifts are common [

6,

7]. These characteristics highlight, in particular, the potential use of Prophet for hydrological forecasting under increasingly dynamic climate conditions.

SARIMAX was selected as the comparative benchmark because it remains one of the most widely applied forecasting models in operational hydrology. Engineering agencies and government practitioners continue to use SARIMAX due to its interpretability, established reliability, and capacity to incorporate exogenous climatic variables. Accordingly, SARIMAX provides a fair and representative baseline against which the added value of Prophet can be evaluated. This selection is consistent with prior hydrological studies, where SARIMA-based models are routinely adopted as reference methods when assessing emerging machine-learning approaches.

Despite this collective body of work, the existing literature lacks a focused comparison of Prophet and SARIMAX within the context of an extreme flood event, particularly one that incorporates multiple hydrological and climatic drivers such as snow water equivalent (SWE), temperature, and precipitation. Most prior studies evaluate these models independently rather than examining their relative strengths, limitations, and uncertainty behavior under identical conditions. Therefore, a clear research gap exists in assessing how a modern decomposable forecasting model like Prophet performs against an established statistical benchmark when applied to a real-world, high-impact hydrological event.

1.2. Shortcomings in Current Research

Despite these advances, both SARIMAX and Prophet present notable limitations. SARIMAX requires careful specification of parameters, and misidentification of seasonal or differencing terms can degrade performance, particularly in nonstationary datasets [

4]. Moreover, although SARIMAX allows for external regressors, its flexibility is limited when multiple climate variables interact in complex ways.

While Prophet is more flexible, this method also faces challenges since it can underperform in datasets with irregular spacing or limited historical records, and it often requires careful tuning of hyperparameters to avoid overfitting [

8]. Additionally, although Prophet generates uncertainty intervals, some studies have noted that these intervals can be overly narrow, potentially underestimating hydrological variability [

9,

10].

The shortcomings of both modeling procedures underline the need for careful validation when applied to stream flow forecasting.

1.3. Strengths of the Prophet Algorithm

Prophet’s primary strength lies in its ability to incorporate nonlinear patterns and multiple covariates, including climate variables such as precipitation, temperature, and snowmelt, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy [

1]. Prophet is particularly effective at detecting and adjusting for changepoints and abrupt shifts in time-series structure, which are common in hydrological systems experiencing rapid environmental changes.

Another advantage of Prophet is its robustness in handling missing or unevenly spaced data, which makes it suitable for real world forecasting scenarios where datasets are rarely complete or regularly sampled. While these capabilities provide meaningful advantages, the effectiveness of Prophet still depends on the characteristics of the underlying dataset and appropriate model configuration, underscoring the importance of applying the method with careful validation.

1.4. Recent Advancements in Flood Forecasting

Recent advancements in flood forecasting have been driven by innovations in data acquisition, computational methods, and predictive modeling. The integration of remote sensing and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) has enabled real time monitoring and high resolution mapping of flood prone areas, thereby providing valuable inputs for forecasting models [

11]. Additionally, the incorporation of machine learning and AI techniques has transformed data-driven hydrologic forecasting by enabling the analyses of large, complex datasets and uncovering nonlinear patterns that traditional statistical models may fail to capture [

12,

13].

Ensemble forecasting approaches have further strengthened predictive reliability by combining multiple models to better account for uncertainty, particularly under extreme hydrological events [

14,

15]. Real time data assimilation methods, such as the Ensemble Kalman Filter [

16], have also improved forecast accuracy by continuously updating models with incoming observations. Furthermore, advances in cloud computing and big data analytics allow for more efficient processing of hydrological and climatic datasets. The inclusion of socio-economic factors alongside physical drivers in recent studies has provided a more holistic understanding of flood impacts, supporting more effective preparedness and mitigation strategies [

17].

1.5. Prophet vs. Other Machine Learning Models

Among machine learning approaches, Prophet stands out for its unique ability to handle time series data with strong seasonal cycles and clear trend components. Prophet is a decomposable model, designed to separate trend, seasonality, and residuals, thereby enhancing interpretability compared to “black box” models such as Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) or Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks [

5]. Unlike deep learning models which often require extensive data and computational resources, Prophet provides a more accessible framework that can be effectively utilized by researchers and practitioners without advanced expertise in time series programming.

As well, Prophet allows the integration of external covariates and can automatically identify changepoints where the structure of the time series shifts significantly [

1]. This feature makes Prophet particularly valuable in environmental forecasting where abrupt changes, such as those driven by sudden precipitation events or snowmelt, must be captured with accuracy. However, its performance may vary depending on the watershed characteristics, where extreme variability poses challenges to prediction accuracy. While deep learning models can capture non-linear interactions, they often lack transparency in their internal workings, which can hinder decision making in operational flood forecasting [

18,

19]. Prophet, by contrast, offers a balance of accuracy, interpretability, and practical usability, making it a strong candidate for applied hydrological forecasting tasks.

These characteristics make Prophet an appropriate candidate for comparative evaluation against widely used statistical models such as SARIMAX. Accordingly, the present study examines whether Prophet’s methodological advantages translate into improved forecasting performance and uncertainty representation during an extreme flood event.

1.6. Objectives of This Study

The primary objective of this study is to conduct a comprehensive comparative analysis of the Prophet and SARIMAX models in stream flow forecasting of flooding disasters. Prophet is evaluated herein against this improved benchmark to assess whether its flexibility in handling seasonality and external variables translates into superior predictive performance.

The evaluation considers accuracy metrics such as MAE, Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and R2, as well as uncertainty bounds associated with each prediction. By explicitly quantifying uncertainty, this study enhances understanding of forecast reliability and provides insights into the strengths and limitations of both models for operational flood forecasting.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area and Datasets

The Bow River basin at Banff is characterized by its mountainous terrain, including glaciers and icefields, and it follows the main valley of the Bow River. The ecosystems surrounding Banff National Park comprise montane (~3%), subalpine (~53%), and alpine (~27%) zones. Forests, primarily located in valley bottoms and on lower mountain hillslopes, cover approximately 44% of the Park area [

20,

21].

The upper Bow River region experiences annual precipitation ranging from 500 to 700 mm, with roughly half falling as snow, while Calgary (a city further down the River) receives about 412 mm of annual precipitation, 78% of which occurs as rainfall [

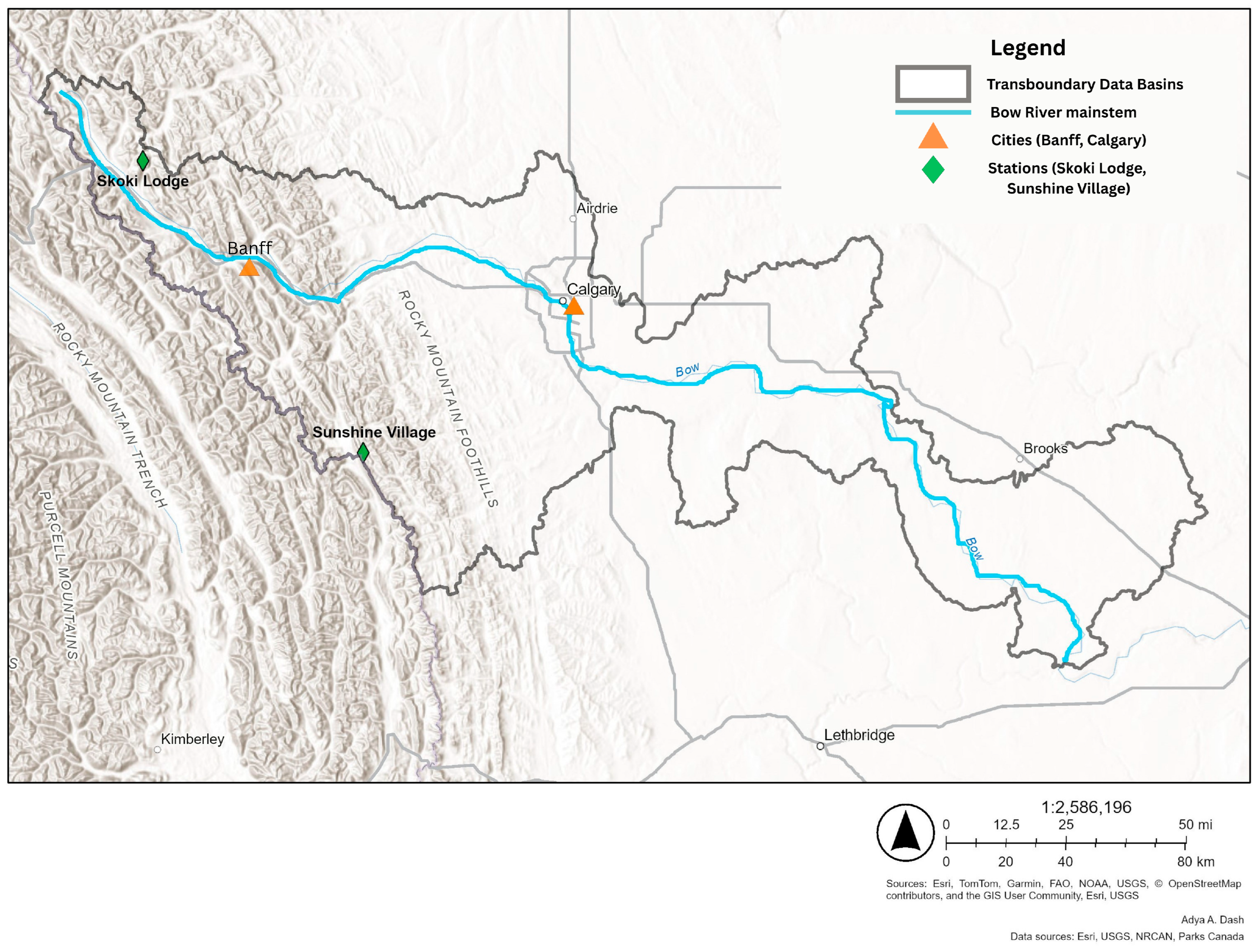

22]. As depicted in

Figure 1, the selected hydrometric station in Banff plays a crucial role in monitoring stream flow, significantly influenced by southern Alberta’s climate conditions characterized by long, cold winters and short, warm summers. The Banff area, with a cold temperate climate and an average annual temperature of –0.4 °C, experiences peak river discharges between May and June, primarily due to the melting of the winter snowpack combined with spring rains.

The Bow River at Banff hydrometric station, operational since 1909, has provided valuable data for studies on mountain hydrology and flooding [

23,

24]. This study utilized daily records of precipitation (rainfall and snowfall), stream flow, and temperature from 5 May 1990, to 21 June 2013, obtained from Environment Canada’s database. To align with the forecasting framework, variables were considered for up to 15 days prior to the June 2013 flood event, ensuring consistency of prediction with both short and medium term prediction horizons. Additionally, mean daily stream flow data compiled by Alberta Environment and Parks for the period 1910–2013 were incorporated into the model. The selection of these datasets was based on the reliability and availability of data, which are critical for developing accurate and robust forecasting models. These comprehensive datasets provide a strong foundation for both understanding and predicting hydrological responses in the Bow River basin.

2.2. Proposed Models

2.2.1. Prophet Algorithm

The Prophet algorithm decomposes the series into three primary components: trend, seasonality, and external regressors, expressed as:

where

denotes the non-periodic trend,

captures the seasonal component,

accounts for special events or external regressors, and

represents the error term.

Prophet’s trend can be modeled using either a piecewise linear function or logistic growth, making it adaptable to both gradual and abrupt changes in hydrological time series. Another advantage of Prophet is its ability to generate prediction intervals, providing quantitative measures of uncertainty around forecasts. This is especially important in hydrological applications where risk-based decision making relies not only on point estimates but also on the range of possible outcomes [

25].

2.2.2. SARIMAX Algorithm

SARIMAX extends the traditional ARIMA framework by incorporating both seasonal components and external variables [

26]. The model is represented as SARIMA (

p,

d,

q)(

P,

D,

Q)

m, where:

p,d,q corresponds to the autoregressive order, differencing order, and moving average order, respectively.

P,D,Q denote the seasonal counterparts.

m is the number of periods per season.

By including exogenous regressors (

Xt), SARIMAX allows external climatic drivers (such as precipitation, temperature, or snowpack) to be integrated directly into the forecasting framework, improving predictive skill in complex hydrological systems [

4,

26].

Mathematically, the SARIMAX model can be expressed as:

where

is the observed flow at time

t,

and

are the autoregressive and moving average coefficients,

are the exogenous variables with coefficients

, and

is the error term.

The advantage of SARIMAX over ARIMA lies in its ability to explicitly handle seasonality and integrate external hydrometeorological variables, which is particularly useful in stream flow forecasting where precipitation and temperature strongly affect outcomes [

3].

For model implementation, the SARIMAX orders (p,d,q)(P,D,Q)m were selected using a combination of autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation diagnostics, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) minimization, and stability checks across candidate configurations. For Prophet, model parameters including the changepoint prior scale, were tuned using cross-validation to balance flexibility and overfitting, with additional adjustments made to incorporate the hydrometeorological regressors effectively. These steps ensured that both models were parameterized in a consistent and data-driven manner.

For both Prophet and SARIMAX, the exogenous variables (precipitation, temperature, and SWE) were supplied using observed values rather than forecasted meteorological inputs. This study was designed as a controlled model-to-model comparison; therefore, identical exogenous information was provided to both models to isolate differences in their predictive behaviour. The intention was not to simulate an operational early-warning system, where future meteorological conditions are unknown, but to evaluate the inherent forecasting performance of each model under consistent hydrometeorological forcing.

All analyses were conducted using Python (version 3.10). Prophet (version 1.1.5) was used for AI-based forecasting, and SARIMAX was implemented using the statsmodels library (version 0.14.0).

2.2.3. Comparative Framework

Together, Prophet and SARIMAX provide a complementary framework for flood forecasting. By comparing the two approaches on the same dataset, this study highlights their relative strengths and limitations in forecasting river discharge.

To enable comparison, the models were trained using the same hydrometeorological dataset comprising precipitation, temperature, and river discharge records from the Bow River Basin. A summary of the variables and their statistical characteristics is presented in

Table 1, which outlines the dataset inputs used for both models.

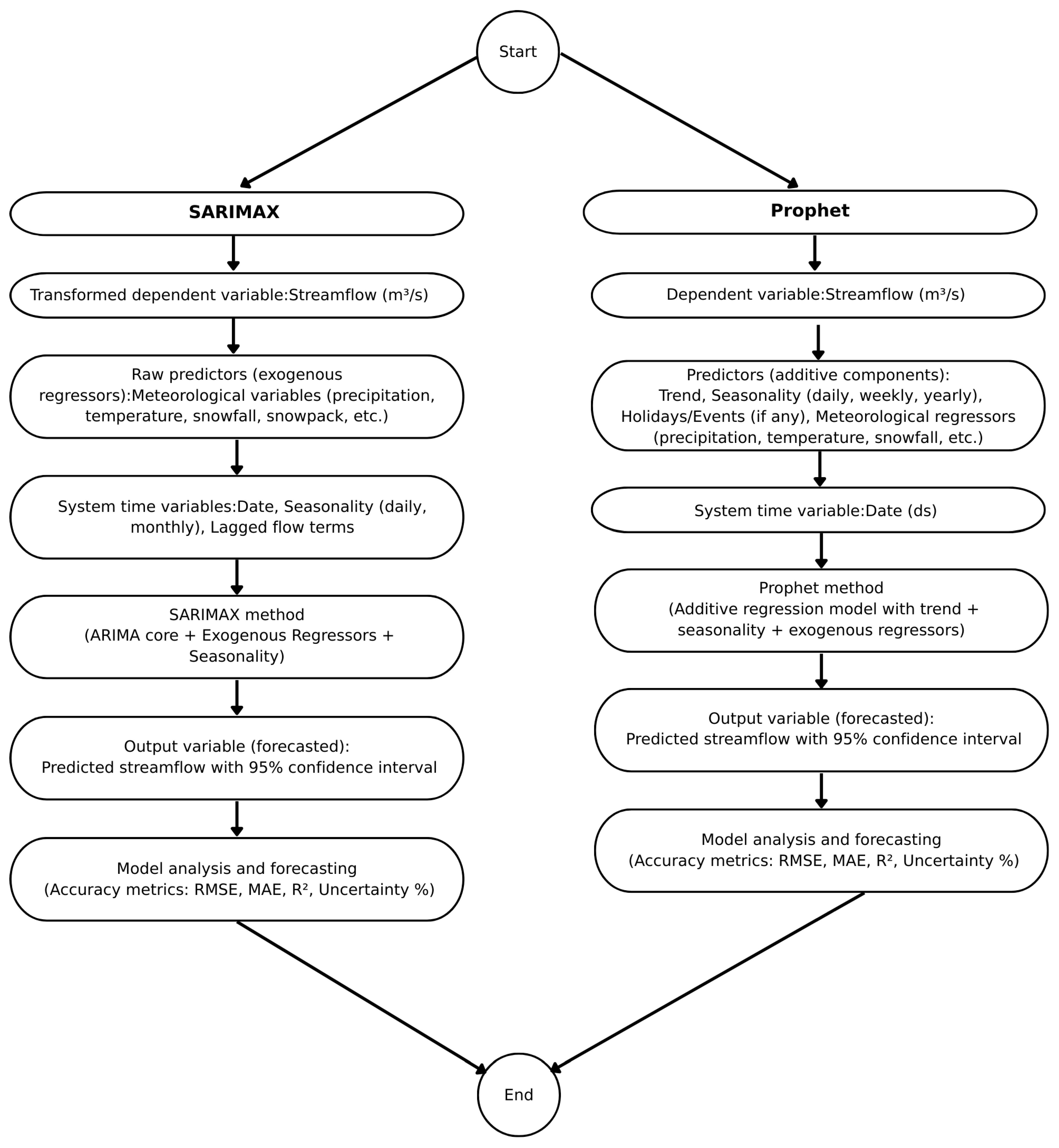

The conceptual differences between Prophet and SARIMAX are illustrated in

Figure 2, which shows the decomposition structure of Prophet alongside the SARIMAX framework.

2.3. Performance Indicators

The evaluation of Prophet and SARIMAX relied on a set of statistical indicators. Together, these metrics provide a balanced view of accuracy, explanatory power, and reliability. This integrated assessment ensures that both accuracy and uncertainty are addressed when comparing model performance.

2.3.1. Coefficient of Determination (R2)

The

R2 measures the proportion of variance in the observed data that is explained by the model:

where

is the observed value at time

i,

is the predicted value,

is the mean of observed values, and

n is the number of observations.

Values close to 1 indicate strong predictive performance, while values approaching or below 0 indicate poor model fit.

2.3.2. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

RMSE quantifies the square root of the average squared differences between predicted and observed values:

This metric penalizes larger errors more heavily, making it particularly suitable for evaluating hydrological forecasts where extreme deviations are critical. A lower RMSE indicates better predictive performance.

2.3.3. Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

MAE measures the average magnitude of forecast errors, disregarding their direction:

Unlike RMSE, MAE treats all errors equally, providing a straightforward and interpretable measure of average prediction accuracy. Lower values indicate more reliable forecasts.

2.3.4. Prediction Uncertainty Percentage (U%)

To assess the reliability of forecasts, the uncertainty interval was quantified using:

This metric reflects the relative width of the prediction interval. Smaller values indicate narrower confidence bounds, signifying greater certainty in the model’s forecasts.

The integration of these performance indicators is particularly critical in the context of flood forecasting. For instance, low MAE and RMSE values provide confidence in day –to day predictions of river discharge, while high R2 values demonstrate the model’s ability to capture long-term stream flow variability. Importantly, the uncertainty percentage (U%) reflects the operational usability of forecasts narrower intervals offer decision makers greater assurance when planning flood mitigation strategies, resource allocation, and early warning dissemination. Together, these indicators ensure a comprehensive assessment that goes beyond accuracy alone, addressing the need for dependable forecasts under dynamic and often extreme hydrological conditions.

2.4. Relative Error (RE)

To provide a scale independent measure of model error, relative error was calculated as the ratio of forecast error to the observed discharge, expressed as a percentage:

where

is the observed flow and

is the predicted flow. This highlights the proportionate magnitude of forecast deviations, which is particularly important when comparing performance across different flow regimes (low flows vs. flood peaks).

3. Results and Discussion

The comparative performance of Prophet and SARIMAX models during the June 2013 flood event at the Bow River, Banff, reflecting on 15-day and 3-day ahead forecasts is presented.

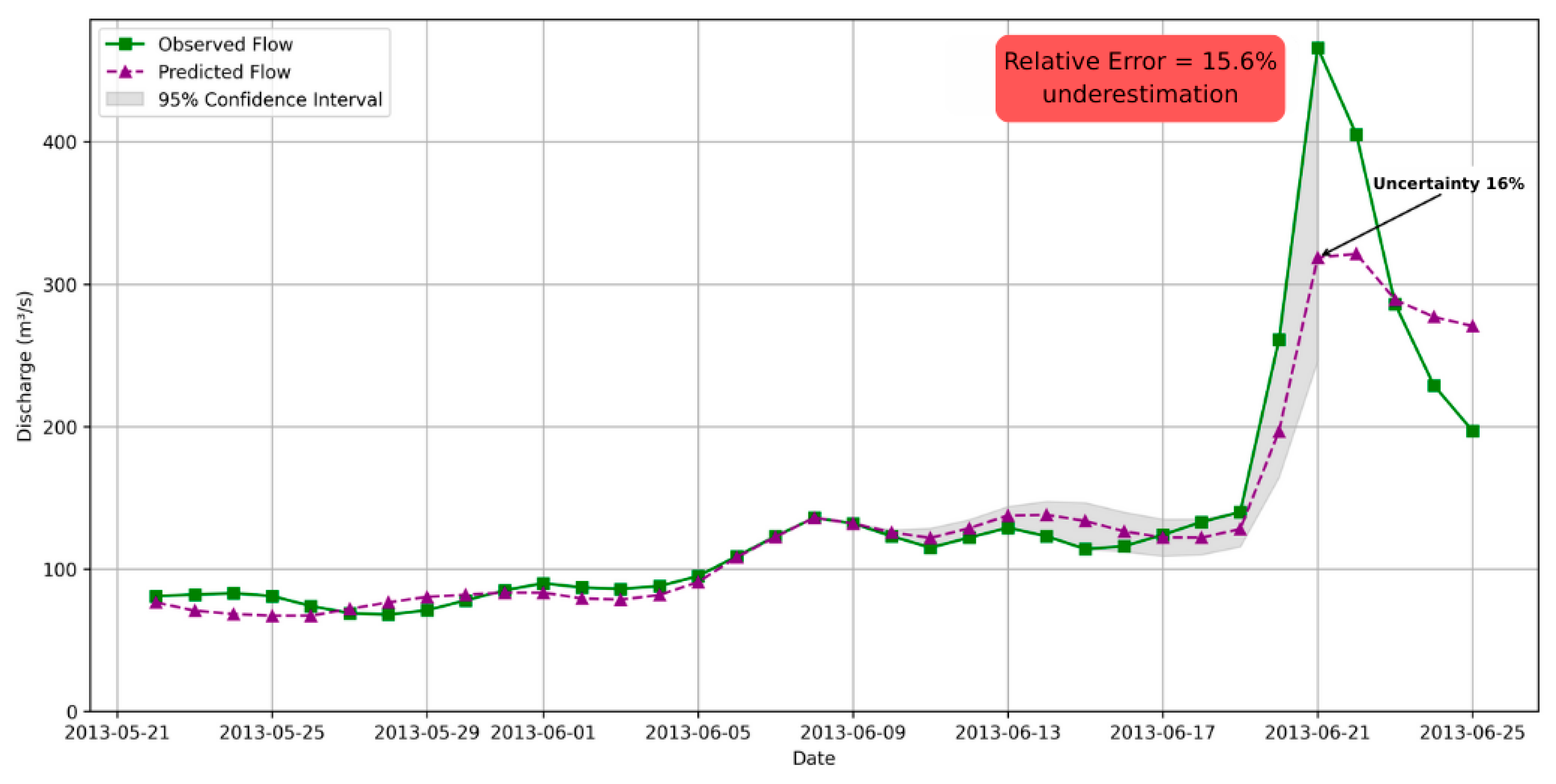

3.1. Prediction Accuracy for 15-Day Ahead Forecasts

Figure 3 presents the 15-day ahead forecasts generated using the SARIMAX model. The model was unable to reproduce the rapid rise and sharp peak associated with the 2013 flood event, resulting in substantial phase mismatches and large deviations from observed flows. The wide uncertainty bounds and the highly negative R

2 value (–4.42) indicate that the model’s underlying linear assumptions and reliance on stationarity were violated during the extreme, non-linear hydrological response of the flood. This suggests that SARIMAX is not well suited for capturing abrupt, rapidly evolving discharge dynamics driven by snowmelt–rainfall interactions.

In contrast,

Figure 4 shows the 15-day ahead forecasts produced using the Prophet model. Prophet successfully captured both the timing and magnitude of the flood peak, reflecting its ability to model non-linear patterns and incorporate exogenous hydrometeorological regressors. Its low MAE (3.65), low RMSE (9.42), and high R

2 (0.95) demonstrate strong agreement with observed flows, consistent with findings from other hydrological applications [

1].

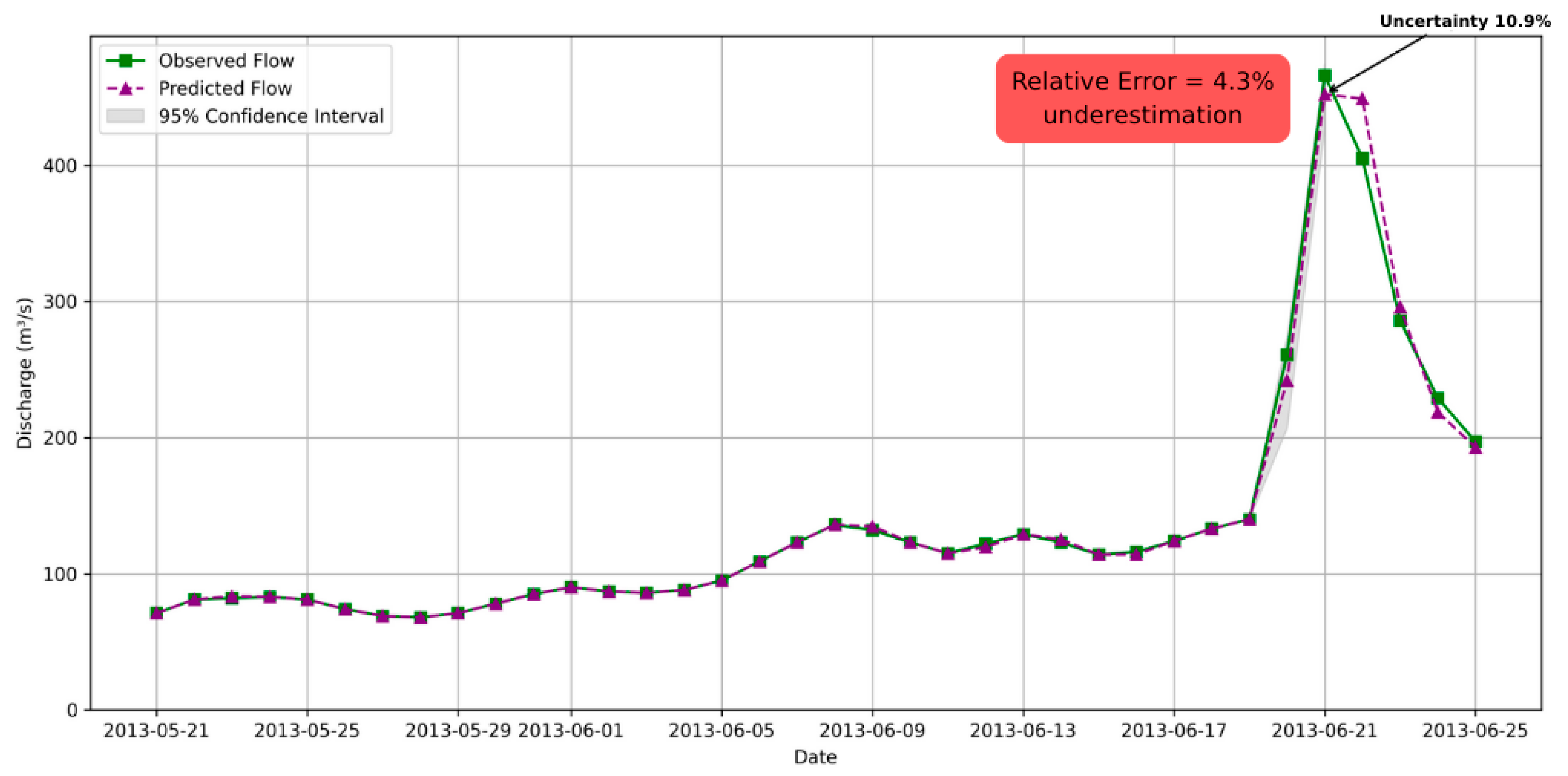

3.2. Prediction Accuracy for 3-Day Ahead Forecasts

Figure 5 shows the 3-day ahead SARIMAX forecasts. Although the shorter lead time improved performance relative to the 15-day horizon, the negative R

2 value (–0.14) and elevated errors (MAE 61.52; RMSE 94.88) indicate that SARIMAX remained less effective at representing the sharp gradients and rapid flow transitions characteristic of the flood event. This reflects the model’s difficulty in capturing non-linear hydrological responses, especially when precipitation and snowmelt-driven inputs produce rapid changes that violate stationarity.

Figure 6 displays the 3-day ahead Prophet forecasts. Prophet closely matched observed flows, capturing both the flood peak and short-term fluctuations with high accuracy (MAE 0.32; RMSE 1.61; R

2 0.99). This performance demonstrates the model’s strength in short-range hydrological forecasting, particularly under rapidly changing streamflow conditions [

1].

3.3. Uncertainty Intervals: Prophet vs. SARIMAX

The evaluation of uncertainty intervals is crucial for understanding the reliability and robustness of forecasting models.

Figure 3 and

Figure 5 show that the uncertainty intervals for SARIMAX are considerably wider, reflecting the model’s sensitivity to non-stationarity series and its reliance on differencing to achieve stability. Broader intervals imply lower predictive confidence and highlight the challenges implicit since SARIMAX faces capturing complex dynamics during periods of high flow variability. These limitations make SARIMAX less effective in the range of potential flood forecasting scenarios and, most importantly, where precise and narrow uncertainty bounds are vital.

In contrast,

Figure 4 and

Figure 6 illustrate the Prophet model’s predictions alongside its uncertainty bounds for the test period. The relatively narrow intervals produced by Prophet indicate higher confidence in its forecasts, reflecting its ability to capture both the general trend and seasonal variations with precision. The Bayesian framework underlying Prophet facilitates the estimation of uncertainty by quantifying variability around predictions, making the intervals particularly informative for decision-making under uncertain flood conditions [

5]. In this study, these features are demonstrated in the context of flood forecasting, providing new insights into their utility for hydrological applications.

While Prophet generated narrower uncertainty bands than SARIMAX, calibration analysis indicated that approximately 93% of observed flows fell within the 95% prediction intervals for the 3-day forecast window and 87% for the 15-day forecast window, suggesting that the intervals are informative.

3.4. Comparative Evaluation

A comparative summary of the models across both horizons is presented in

Table 2. Prophet consistently substantially outperforms SARIMAX, with substantially lower error values and positive R

2 values, reflecting its robustness in capturing complex river flow dynamics. Conversely, SARIMAX displayed instability at longer horizons and limited adaptability to flood induced variability, leading to unreliable forecast.

3.5. Comprehensive Data Integration

The study is based on an extensive dataset comprising daily records of streamflow, precipitation (rainfall and snowfall), and temperature from the Bow River basin. The inclusion of both hydrological and meteorological variables provides a more complete representation of the watershed’s dynamics. Such data integration strengthens forecasting performance by enabling the models to account for snowmelt driven flow variability, rainfall induced runoff, and temperature fluctuations that influence hydrological processes [

27].

Prophet’s design, which allows for the inclusion of external regressors, particularly enhances its performance in this context, as it can directly integrate these variables into the forecasting framework. In contrast, SARIMAX requires careful pre-processing and assumptions about stationarity, limiting its adaptability to incorporate diverse predictors. Comprehensive data integration is essential for capturing the multifaceted drivers of streamflow variability, providing models with the robustness required for reliable flood forecasting [

28].

Predictor variables were considered for up to 15 days prior to the 2013 flood peak. This horizon was selected based on hydrological reasoning: snowmelt dominated catchments in the Canadian Rockies exhibit flow responses on the order of 1–2 weeks, depending on temperature and precipitation inputs. Autocorrelation and partial autocorrelation analyses further supported the use of lags in the 7–15 day range, aligning with basin travel times and meltwater release. This ensured that both immediate meteorological drivers and cumulative snowmelt storage signals were represented.

3.6. Practical Implications

Accurate medium range (up to 15-day) and short-range (3-day) forecasts of river flow carry significant implications for flood risk disaster management and emergency preparedness. Reliable forecasts allow authorities to implement proactive strategies such as early warnings, evacuation planning, and infrastructure adjustments, ultimately reducing the social and economic impacts of floods [

29]. Prophet’s demonstrated ability in this study, to deliver more accurate forecasts with higher confidence levels, underscores its potential for operational early warning systems.

The two forecast windows analyzed serve distinct management functions. Three-day lead times are most valuable for emergency warnings and evacuation decisions, where precision around flood peaks is critical. 15-day lead times, though inherently more uncertain, may be crucial for preparedness planning. Together, these prediction forecasts may represent a tradeoff between short-term accuracy and medium-term strategic value.

Furthermore, reliable streamflow predictions of potential flood disasters enhance resource allocation for reservoir operations, optimize floodgate scheduling, and support strategic planning for infrastructure resilience. By contrast, the relatively lower accuracy and wider uncertainty ranges of SARIMAX highlight the challenges of relying solely on traditional statistical models in dynamic flood prone environments. The integration of advanced forecasting models such as Prophet into decision making systems could substantially improve community resilience and disaster preparedness [

30].

3.7. Limitations and Future Work

While the analysis demonstrates significant progress in flood forecasting using Prophet and SARIMAX, several considerations remain. The June 2013 Bow River flood was used as a representative event for model evaluation for potential flood disasters, the findings are indicative of similar performance patterns observed across multiple flood years. The consistent results highlight the robustness of both models in capturing hydrological variability under diverse climatic and snowpack conditions, underscoring their potential applicability to other watersheds.

Second, although this work incorporated SWE data from two stations (Skoki Lodge and Sunshine Village), together with temperature and precipitation as exogenous regressors, the spatial coverage of snowpack observations remains limited relative to the basin scale. Incorporating multi station networks, remote sensing datasets, or gridded SWE products would improve robustness and spatial representativeness.

A further limitation concerns the transferability of the results to other hydrological environments. The Bow River represents a snowmelt-dominated alpine basin, where flow responses are governed by gradual accumulation–melt cycles and temperature-modulated runoff. In contrast, rainfall-driven flash-flood basins respond on much shorter timescales and are influenced by localized, high-intensity storm events. Larger regional basins may also require the integration of additional exogenous drivers such as soil moisture, antecedent wetness indices, or teleconnection patterns. While Prophet’s flexibility in incorporating multiple covariates suggests potential applicability across these settings, dedicated testing is needed to evaluate its performance in rainfall-dominated systems and multi-driver basins. Future research should therefore extend model assessment to a broader range of watershed types to determine how basin characteristics influence predictive skill and uncertainty behavior.

4. Conclusions

This comparative analysis demonstrates that the Prophet model significantly outperforms the SARIMAX model for short- to medium-range streamflow forecasting during a major flood event in the Bow River basin. Prophet achieved substantially lower error metrics, stronger alignment with observed flows, and narrower prediction intervals across both 15-day and 3-day forecast horizons. Its decomposable structure and ability to incorporate external hydrometeorological variables enabled it to capture the rapid, non-linear changes associated with extreme flood conditions more effectively than SARIMAX.

For 15-day forecasts, Prophet produced significantly lower MAE and RMSE values and a substantially higher R2, whereas SARIMAX showed large deviations and negative skill relative to a mean baseline. At the 3-day horizon, SARIMAX performance improved modestly, but Prophet retained a clear advantage with error values an order of magnitude lower and an R2 of 0.99. These results demonstrate Prophet’s robustness in both medium-range and short-range hydrological forecasting.

A key strength of Prophet lies in its uncertainty quantification. Its narrower and more stable prediction intervals reflect increased reliability, an essential feature for operational flood forecasting, where early warning, evacuation planning, and real-time decision making depend heavily on probabilistic confidence.

From a practical standpoint, Prophet’s flexibility in integrating exogenous drivers, handling missing or irregular data, and maintaining performance at extended lead times highlights its potential value for flood risk management. More reliable forecasts can enhance preparedness, optimize reservoir operations, support emergency response, and strengthen community resilience to extreme hydrological events.

Although Prophet and SARIMAX differ in methodological foundations, the comparison presented in this study is justified because SARIMAX remains one of the most widely used operational forecasting tools in hydrology. Many agencies continue to rely on SARIMA-based models for stream flow prediction due to their transparency, established use, and ability to incorporate climatic regressors. Evaluating Prophet against SARIMAX therefore provides a realistic and policy-relevant benchmark for assessing whether newer AI-based approaches offer measurable improvements in settings where traditional statistical models are still the standard. This comparative framework enables practitioners to understand not only the advantages of advanced models, but also the extent to which they outperform established methods under extreme conditions.

While this study focuses on Prophet and SARIMAX, it is acknowledged that deep learning models such as LSTM, GRU, or CNN constitute an important class of contemporary AI approaches in hydrological forecasting. The present work was intentionally designed to evaluate a modern interpretable forecasting algorithm (Prophet) against a widely adopted operational benchmark (SARIMAX) under identical hydrometeorological conditions. This focused comparison provides clarity on methodological differences and offers practical insight for agencies that are considering transitions from traditional statistical tools to emerging AI-based models. Future studies can extend this framework by incorporating deep learning architectures to provide a more comprehensive assessment of the broader spectrum of AI techniques.

In conclusion, Prophet demonstrates superior predictive accuracy, uncertainty handling, and operational applicability compared to SARIMAX. These strengths underscore its promise as a next-generation tool for hydrological forecasting and disaster risk reduction. Future work should extend this analysis to seasonal forecasting, incorporate real-time meteorological inputs, and evaluate performance across diverse hydrological basins to further establish generalizability and model reliability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.D. and E.M.; methodology, A.A.D.; software, A.A.D.; validation, A.A.D. and E.M.; formal analysis, A.A.D.; investigation, A.A.D.; resources, E.M.; data curation, A.A.D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.D.; writing—review and editing, A.A.D. and E.M.; visualization, A.A.D.; supervision, E.M.; project administration, E.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) [RGPIN-2023-03391]. Additional support through the Morwick Scholarships in Water Resources Engineering [E3024], funded by the School of Engineering, University of Guelph, and the Skills for Communicating Change in Agri-food Scholarship [E/16084], sponsored by the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, is also sincerely appreciated. The authors further acknowledge the Nora Cebotarev Memorial Scholarship [E8012] for its generous contribution to this research.

Data Availability Statement

The streamflow data used in this study are publicly available from the Water Survey of Canada (HYDAT) database:

https://wateroffice.ec.gc.ca/ (accessed on 15 October 2025). Meteorological variables (precipitation and temperature) were obtained from the Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) climate data archive:

https://climate.weather.gc.ca/ (accessed on 15 October 2025). Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) observations were retrieved from publicly accessible Government of Canada snow monitoring stations:

https://climate-scenarios.canada.ca/?page=blended-snow-data (accessed on 15 October 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dash, A.A.; Castro, K.; McBean, E. Modelling for improved flood forecasting in the Bow River Basin using Prophet. J. Environ. Inform. Lett. 2024, 13, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Box, G.E.P.; Jenkins, G.M.; Reinsel, G.C. Time Series Analysis: Forecasting and Control, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Athanasopoulos, G. Forecasting: Principles and Practice, 3rd ed.; OTexts: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, G.E.d.M.e.; Filho, F.C.M.d.M.; Canales, F.A.; Fava, M.C.; Brandão, A.R.A.; de Paes, R.P. Assessment of time series models for mean discharge modeling and forecasting in a sub-basin of the Paranaíba River, Brazil. Hydrology 2023, 10, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.J.; Letham, B. Forecasting at Scale. Am. Stat. 2018, 72, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenyi, M.G.S.; Yamamoto, K. A hybrid SARIMA-Prophet model for predicting historical streamflow time-series of the Sobat River in South Sudan. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Hasan, S.S.; Mahmud, A.; Bai, L. Analysis and forecasting of meteorological drought using PROPHET and SARIMA models deploying machine learning technique for southwestern region of Bangladesh. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2025, 27, 100761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulos, F.; Hyndman, R.J.; Bergmeir, C. Exploring the sources of uncertainty: Why does bagging for time series forecasting work? Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 268, 545–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makridakis, S.; Spiliotis, E.; Assimakopoulos, V. The M4 Competition: 100,000 time series and 61 forecasting methods. Int. J. Forecast. 2019, 36, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasari, S.K.; Preetha, P.; Ghantasala, H.M. Predictive analysis of hydrological variables in the Cahaba watershed: Enhancing forecasting accuracy for water resource management using time-series and machine learning models. Earth 2025, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, M.S.B.M.; An, C.; Li, S.S. Evolution from the physical process-based approaches to machine learning approaches to predicting urban floods: A literature review. Environ. Syst. Res. 2025, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zounemat-Kermani, M.; Batelaan, O.; Fadaee, M.; Hinkelmann, R. Ensemble machine learning paradigms in hydrology: A review. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Kuglitsch, M.M.; Pelivan, I.; Albano, R. Review and intercomparison of machine learning applications for short-term flood forecasting. Water Resour. Manag. 2025, 39, 1971–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, H.L.; Pappenberger, F. Ensemble flood forecasting: A review. J. Hydrol. 2009, 375, 613–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Peng, T.; Qi, H.; Yin, Z.; Shen, T. Improving flood forecasting skill by combining ensemble precipitation forecasts and multiple hydrological models in a mountainous basin. Water 2024, 16, 1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, E.; Ghil, M. A multi-model ensemble Kalman filter for data assimilation and forecasting. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2023, 15, e2022MS003123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, K.T.; Balasubramanian, M.; Govindarajan, P.L.; Kesav, B. Assessing the socioeconomic and environmental determinants of flood vulnerability in India: A panel data approach. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Available online: http://www.deeplearningbook.org (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Zhou, J.; Chen, L.; Hu, T.; Lu, H.; Shi, Y.; Chen, L. The comparative study of machine learning agent models in flood forecasting for tidal river reaches. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achuff, P.L.; Corns, I.G.W.; Hosie, R.C. Ecological Land Classification of Banff and Jasper National Parks; Parks Canada: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2002; Volume II: Soil and vegetation resources. [Google Scholar]

- Natural Regions Committee (Government of Alberta). Natural Regions and Subregions of Alberta; Government of Alberta: Edmonton, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Sullivan, M.; Bayne, E.; Scrimgeour, G. Landscape-level stream fragmentation caused by hanging culverts along roads in Alberta’s boreal forest. Can. J. For. Res. 2008, 38, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environment Canada. Canadian Climate Data Archives. Government of Canada. 2013. Available online: https://climate.weather.gc.ca (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Alberta Environment and Parks. Hydrometric and Climate Data Records. Government of Alberta. 2015. Available online: https://open.alberta.ca/publications (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Nguyen, D.H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kwon, H.-H.; Bae, D.-H. Uncertainty Quantification of Water Level Predictions from Radar-based Areal Rainfall Using an Adaptive MCMC Algorithm. Water Resour. Manag. 2021, 35, 2197–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyo, A.; Adewumi, A.; Ayo, C. Stock price prediction using the ARIMA model. In Proceedings of the 2014 UKSim-AMSS 16th International Conference on Computer Modelling and Simulation, Cambridge, UK, 26–28 March 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Pechlivanidis, I.G. Hybrid approaches enhance hydrological model usability for local streamflow prediction. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beven, K. Rainfall-Runoff Modelling: The Primer; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Merz, B.; Hall, J.; Disse, M.; Schumann, A. Fluvial flood risk management in a changing world. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2010, 10, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, H.; Shrestha, P.K.; Rakovec, O.; Apel, H.; Vorogushyn, S.; Kumar, R.; Thober, S.; Merz, B.; Samaniego, L. High-resolution impact-based early warning system for riverine flooding. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).