Abstract

The Ukrainian brook lamprey (UBL) (Eudontomyzon mariae) spreads in Poland and often replaces the European brook lamprey (EBL) (Lampetra planeri) in rivers contaminated by wastewater effluents. We aimed to investigate whether this phenomenon is associated with differences in the intestinal microbiota of the two lamprey species. We analysed seasonal changes in the midgut microbial content of the UBL ammocoetes collected from a section of the River Gać affected by wastewater treatment plant effluent. The numbers of cultivable psychrophilic (autochthonous) and mesophilic (allochthonous) microorganisms, along with Escherichia coli and faecal streptococci, were compared to those found in the EBL from the same site. Higher levels of the faecal indicator microorganisms were observed in the UBL gut content compared to the EBL across most seasons, particularly in the winter (all mesophiles), in contrast to the levels of psychrophilic bacteria. This may suggest a relatively greater accumulation of mesophilic, sewage-associated bacteria in the UBL gut. Varying intestinal bacterial counts in the UBL gut did not reflect trends observed for the microorganisms in surrounding water during the studied seasons. These findings support the hypothesis that the UBL potentially benefits from the uptake of faecal bacteria. Such adaptation may contribute to its dominance in contaminated freshwater ecosystems, where EBL populations decline.

1. Introduction

Effluent from municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) is considered one of the primary stressors in receiving freshwater ecosystems [1]. Effluents may contain not only pathogenic and antibiotic-resistant bacteria but also higher amounts of nutrients and a complex mixture of hazardous chemical substances, such as pharmaceuticals (including antimicrobials), pesticides, metals, and microplastics [1,2,3]. Importantly, they are also a source of genetic material introduced into the environment [4,5]. Studies on microbial communities in rivers revealed changes in microbial content and a decline in the microbial diversity downstream of the WWTP, primarily due to effluent discharge [5,6]. However, downstream microbes have been found to exhibit greater metabolic diversity, likely as an adaptive response to chemical stress from organic pollutants, enhancing their decomposition capacity [5].

Microorganisms that naturally occur in the environment (e.g., in freshwater) are referred to as autochthonous, and under Polish conditions, they are typically cold-water psychrophiles with an optimal growth temperature of around 15 °C [7,8]. Wastewater introduces into the environment a group of foreign microorganisms known as allochthonous species. These are generally mesophilic bacteria, with optimal growth temperatures ranging from 20 to 45 °C [9].

Among allochthonous microorganisms are coliform bacteria, including Escherichia coli (EC) and faecal streptococci (FS), which are considered indicator microorganisms (IMs) of faecal contamination. Their level increases in proportion to the degree of water pollution [9]. These microbes are a natural component of the intestinal microbiota of all warm-blooded animals and are excreted in faeces in far greater numbers than pathogenic bacteria. However, they are not naturally present in aquatic ecosystems and typically do not multiply there, even in contaminated water [10,11,12].

The biological and chemical components introduced into water through wastewater discharge exert, in most cases, a negative impact on aquatic fauna, including both invertebrates and vertebrates living downstream of the discharge sites. Our understanding of the cumulative impacts of treated wastewater (often not fully characterised in terms of its chemical and microbial composition) on animal health and microbiomes remains limited. Nevertheless, several studies have documented effects such as behavioural and morphological changes in fish, including external male feminization, gonadal intersex, reduced fertilisation success, increased metabolic rates, and impaired stress responses [1,13,14,15]. A growing body of evidence also points to the vulnerability of other aquatic vertebrates to domestic pollution. For instance, in our previous work, we reported significant differences between the body condition indices of the European brook lamprey (EBL) (Lampetra planeri) ammocoetes from polluted and relatively unpolluted sections of a lowland river, highlighting the detrimental effects of faecal contamination on their health and development [16]. On the contrary, Pyrzanowski et al. (2025) [17] reported an improved condition and growth of the Ukrainian brook lamprey (UBL) (Eudontomyzon mariae) in polluted river sections, suggesting a potential adaptive advantage in such environments. Thus, the two adjacent lamprey species, coexisting in a section of the River Gać, which is constantly polluted by a WWTP, reacted inversely to the living conditions as the EBL showed worse indices of the body condition than the UBL in the same environment. It could be connected with the observed differences in spatio-temporal dynamics of both lamprey species in Poland. The EBL decreased its abundance and disappeared from many localities, while the UBL expanded its distribution and replaced the EBL in some habitats [18]. It is possible that contrary to the EBL, the UBL benefits from sewage pollution, as was observed for some fish that were attracted to sites with the constant temperature and nutrient-rich character of wastewater outflows [1].

We aimed to examine whether these differences in vulnerability to water pollution are associated with the abundance of microorganisms absorbed from the contaminated water. We hypothesised that the UBL could accumulate higher numbers of sewage-associated bacteria that exist in the gut of the UBL in comparison with the EBL and discussed whether it might be a kind of the UBLs ‘adaptation to polluted waters.

2. Materials and Methods

The subject of the research were the UBLs and their midgut cultivable microbiota.

2.1. Sampling

The study was conducted in the River Gać, central Poland (51.539270° N, 20.139083° E), at a site located downstream from the outflow of a municipal WWTP in the village of Spała. This section of the river is 3–4 m wide and 0.3–0.7 m deep, with a sandy bottom interspersed with organic deposits and limited submerged vegetation due to the dense riverside tree cover.

Sampling was carried out in four seasons: summer (June 2020), autumn (September 2020), winter (January 2021), and spring (April 2021). In each season, three individuals (ammocoetes) of the EBL [16] and three larval individuals of the UBL were collected, for a total of 24 specimens; with permission from the Regional Directorate of Environmental Protection (WPN.6401.282.2020.JHi/BWo), all lampreys were captured using an electrofishing method. The UBL measured 163–176 mm in total length, while the EBL ranged from 110 to 170 mm. Water samples (0.5 L) were taken 0.25 m above the substrate and stored in sterile containers under chilled conditions until laboratory analyses [16]. The alimentary tracts of lampreys were removed under aseptic conditions, and midgut contents were isolated immediately after euthanasia. Details regarding the methodology and study area characteristics can be found in the work of Zięba et al. (2024) [16].

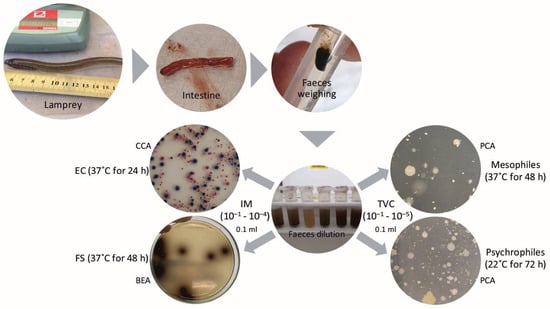

The faecal samples from the dissected larvae were weighed and thoroughly suspended in 1 mL of 0.85% normal saline by vortexing (1 × 20 s), sonicating (2.5 min), and another round of vortexing (2 min).

2.2. Estimation of the Numbers of Psychrophilic and Mesophilic Microorganisms in the Midgut Content

The total viable counts (TVCs) of cultivable psychro- and mesophilic microorganisms per gram of the lampreys’ faeces were estimated using the pour-plate technique, as described previously [16]. Briefly, plate count agar (PCA) (Molten Yeast Extract LAB-Agar) (BioMaxima S.A., Lublin, Poland) cooled to 45 °C was mixed in a sterile Petri dish with 0.1 mL each of the faeces suspensions or its serial 10/100/1000/10,000/100,000-fold dilutions in 0.85% normal saline. After the incubation (22 °C for 72 h for psychrophiles and 37 °C for 48 h for mesophiles), the growing colonies were counted (A) and the results were presented as colony-forming units (CFUs) per 1 g of a faecal sample, according to the formula: CFU/g = A × 10 × reciprocal titer/M, where 10 was a conversion factor per 1 mL and M represented the mass of the faecal sample in grams. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.3. Estimation of the Numbers of Escherichia coli (EC) and Faecal Streptococci (FS)

The numbers of live EC and FS per gram of the lampreys’ faeces were estimated according to the methods described previously [16]. Briefly, 0.1 mL each of the faeces suspensions and their serial 10/100/1000/10,000-fold dilutions in 0.85% normal saline were spread on the surface of CCA medium (Chromogenic Coliform LAB-AGAR) (BioMaxima S.A., Poland) for EC or BEA medium (Bile Esculin Azide LAB-AGAR) (BioMaxima S.A., Poland) for FS. After the incubation (37 °C for 24 h—EC and 37 °C for 48 h—FS), the growing colonies (dark-blue for EC, brown with a brown halo for FS) were counted (A) and the results were presented as colony-forming units (CFUs) per 1 g of a faecal sample, according to the formula: CFU/g = A × 10 × reciprocal titer/M, where 10 was a conversion factor per 1 mL and M represented the mass of the faecal sample in grams. The experiments were performed in triplicate.

A schematic diagram presenting the methodology used in the research is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The research scheme.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) or means ± standard error of the mean (SEM), calculated per individual specimen. Prior to statistical analyses, microbiological data expressed as colony-forming units per gram (CFU/g) were log10-transformed to normalise the distribution and reduce the impact of outliers.

Seasonal differences in microbial abundance were assessed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunn’s multiple comparison post hoc test to identify statistically significant differences between specific seasonal pairs. Comparisons between two microbial groups (e.g., EC vs. FS within a given season) were conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired data.

Inter-species comparisons (the UBL vs. the EBL) were performed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Welch’s correction to account for the heterogeneity of variances. Statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05. Where appropriate, interactions between factors (species × season) were also evaluated.

The relationships between the numbers of the studied bacteria in water and in the intestines of UBL across seasons were analysed using Spearman’s rank correlation (significance threshold: p ≤ 0.05).

All statistical analyses were conducted using R software (version 4.5.1; R Core Team, 2025).

3. Results and Discussion

Lampreys from the genus Eudontomyzon are suggested to be the most distributed lampreys in Europe. The UBL is known from the watersheds of the Baltic Sea, the Black Sea, the Aegean Sea, and the Caspian Sea [19]. In some rivers, the UBL coexists with the EBL. Both brook lampreys are assessed in Poland as vulnerable species [18].

Our research involved estimating the number of cultivable microorganisms living in the midgut of the UBL larvae in polluted water. We defined the total number of psychrophilic microorganisms which may be considered as autochthonous in the relatively cold environment in the River Gać and its cold-blooded residents as well as the total number of mesophilic microorganisms which may be regarded as allochthonous in these conditions. Furthermore, we determined the number of IMs (both EC and FS) which are typical inhabitants of the intestines of warm-blooded animals and humans [12] and compared the microbial levels in the UBL with those observed for the EBL in the same environment [16]. High levels of IMs in the water may have influenced their content in the midgut of lamprey ammocoetes filtrating the nutrition from mud.

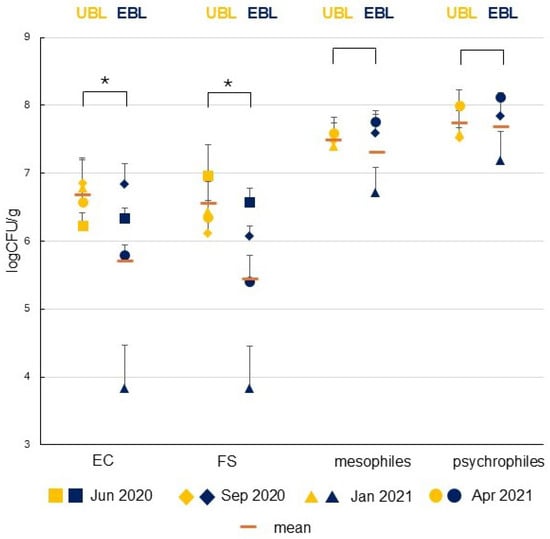

The gut microbiota of the UBL remained relatively stable over the year compared to EBL. Comparative analysis revealed that the UBL larvae accumulated markedly greater numbers of sewage-associated bacteria in their midgut than the EBL. In most seasons, IMs were present at significantly elevated levels in the midgut content of the UBL (Mann–Whitney, p ≤ 0.001) and this difference was highly pronounced in winter (January 2021). In this month, mesophilic bacteria were more numerous in the UBL midgut, while no other significant differences were detected in the TVC of mesophilic and psychrophilic bacteria between the two species (Figure 2, Table S1). The microbial abundance within the UBL midgut exhibited a significant disconnect from the seasonal fluctuations observed in the ambient water for all bacterial groups studied, including autochthonous psychrophiles and allochthonous mesophiles (in the number of IMs). In contrast, the EBL demonstrated a correlating response, as its intestinal bacterial counts reflected the trends found in the surrounding aquatic environment [16]. The microbial characteristics of the surrounding water in the studied seasons were presented it our previous paper [16].

Figure 2.

Seasonal variations in total viable counts (TVCs) of mesophilic and psychrophilic bacteria and indicator microorganisms—E. coli (EC) and faecal streptococci (FS)—in the midgut content of ammocoetes of Eudontomyzon mariae (Ukrainian brook lamprey, UBL) and Lampetra planeri (European brook lamprey, EBL) from the River Gać. Log-transformed values of colony-forming units (CFUs)/g are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Sampling was conducted in four seasons: summer (June 2020), autumn (September 2020), winter (January 2021), and spring (April 2021). Significant differences between groups (four-season means) (p ≤ 0.001) are indicated with an asterisk (*).

3.1. TVC in the UBL Midgut

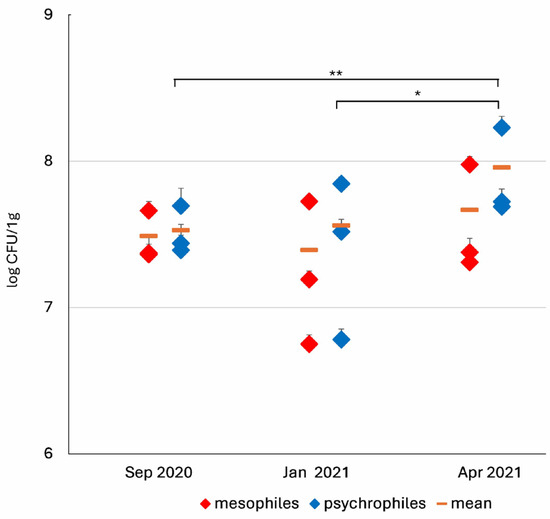

Studies on the total number of cultivable microorganisms in the intestines of the UBL larvae showed that the highest levels of psychrophilic microorganisms were observed in spring (in April, which was exceptionally cold in 2021) reaching a number of 9.06 × 107 CFU/g (p ≤ 0.05). The average counts of mesophiles in the analysed seasons were not significantly different (Figure 3, Table S1).

Figure 3.

Seasonal variations in TVC of mesophilic and psychrophilic microorganisms in the midgut of UBL ammocoetes. Data are log-transformed (CFU/g) and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for individual specimens. Significant differences between seasons were determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons: p: * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01.

The numbers of psychrophilic and mesophilic microorganisms were similar in autumn (September 2020) and winter (January 2021) (Figure 3), ranging from 2.5 to 3.6 × 107 CFU/g, with a 1:1 ratio between these two groups in both seasons.

3.2. Comparison of TVC in the Midgut of the UBL and the EBL in Relation to the Living Environment

Two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of lamprey species and no significant effect of season in the numbers of psychrophilic and mesophilic bacteria (Table 1).

Table 1.

The effects of species and season on microbial numbers in the lampreys’ larvae midgut content (ANOVA II, log-transformed data).

In the case of the EBL, which inhabits the same environment as the UBL, the highest numbers of both psychrophiles and mesophiles were recorded in spring (April 2021). However, in each studied season, psychrophilic microorganisms dominated over the mesophilic ones (2–3 times higher counts). This result reflected the situation in the water environment where the lampreys live, with psychrophiles dominating over the mesophiles to a small extent (two to three times) [16].

The numbers of psychrophiles and mesophiles in the intestines of both lamprey species were similar in autumn (September 2020) and in spring (April 2021), while in winter (January 2021), both mesophiles and psychrophiles seemed to be more numerous in the intestines of the UBL, but only in the case of mesophiles the difference is significant (Figure 2, Table S1). The psychrophile/mesophile ratio in the midgut of the UBL was found to be lower compared to its European neighbour and to the polluted water they live in, whilst in normal (relatively unpolluted) river water, allochthonous mesophiles remained in a minority (6–11 times lower numbers than for autochthonous psychrophiles) [16].

No correlation was observed between seasonal changes in the numbers of psychrophilic (p = 0.360) and mesophilic (p = 0.748) bacteria in the intestines of the UBL and in the water, where the lowest TVC levels were found in September 2020 and the highest in January 2021 for psychrophiles and in April 2021 for mesophiles. In contrast, opposing results were obtained for the EBL, where varying intestinal bacterial counts reflected trends observed in the surrounding water in the studied autumn and spring seasons [16].

3.3. Presence of IMs in the UBL Midgut

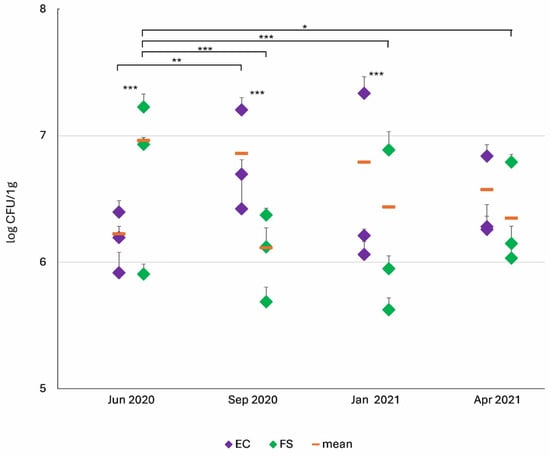

In the midgut content of the UBL ammocoetes, the number of EC was highest in September 2020 (7.22 × 106 CFU/g) and lowest in June 2020 (1.67 × 106 CFU/g). In contrast, the highest number of FS was recorded in June 2020 (9.15 × 106 CFU/g), while the lowest was observed in September 2020 (1.30 × 106 CFU/g). FS counts remained at a similar level in January and April 2021 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Seasonal variation in the abundance of indicator microorganisms (IM): EC and FS in the midguts of UBL ammocoetes. Data are log-transformed (CFU/g) and presented as mean ± SD per individual. Significant differences between seasons were determined using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc comparisons. Differences between microbial groups were assessed using the Wilcoxon test. Statistical significance was set at p: * ≤ 0.05, ** ≤ 0.01; *** ≤ 0.001.

Statistically significant differences between the EC and FS numbers were found in all seasons except spring (April 2021). In summer (June 2020), FS counts were more than five times higher than EC count, whereas in autumn (September 2020), EC predominated. In winter (January 2021), EC also outnumbered FS, although only by a factor of two (Figure 4).

3.4. Comparison of IM Numbers in the Midgut of UBL and EBL in Relation to the Living Environment

In the case of IMs in the lampreys’ midgut, the two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of both species and season (Table 1). A post hoc HSD Tukey test is shown in Table S1. The number of both IMs was significantly higher in the ammocoetes midgut content of the UBL compared to the EBL (Figure 2) in every season except for autumn (September 2020) and except for summer (June 2020) for EC (Table S1). The greatest differences were observed in winter (January 2021), when the numbers of IMs in the EBL were low compared to the other seasons [16], while in the UBL, they remained high and comparable to those observed in the other seasons (Figure 4). In January 2021, over 246 times more EC and 57 times more FS were detected in the UBL than in the EBL. Smaller differences were observed in April 2021, when the UBL exhibited six-fold and nine-fold higher levels of EC and FS, respectively, than EBL. The smallest disparity in FS abundance was recorded in June 2020, with values more that two-fold greater in the UBL (Figure 2).

Seasonal variations in the number of EC in the intestines of UBL did not reflect the fluctuations observed in the water inhabited by the lampreys (Spearman’s correlation, p = 0.671). There, EC levels were similar in summer (June) and winter (January), slightly lower in autumn (September), and increased markedly in spring (April) [16]. In contrast, the intestinal EC content in UBL was the lowest in summer (June), significantly higher in autumn (September), and in the following seasons remained at intermediate levels between these extremes (Figure 4).

No correlation was found between the midgut levels of FS and the counts of bacteria detected in the aquatic environment across the studied seasons (p = 0.276) [16]. However, a similar trend was observed to some extent in both variables. Higher FS counts were detected in June 2020 and January 2021 than in September 2020 both in water and in the UBL midgut content. The exception was April 2021, when the FS level in the water increased, while in the midgut it decreased. Different results were obtained for the EBL [16], where, except for winter, higher EC and FS numbers in the midgut content were associated with higher numbers of these IMs detected in water.

3.5. Midgut Microbiota and Lampreys’ Fitness

The information about lampreys’ microbiota and its role is scarce and does not apply to the UBL. Gram-negative bacteria seem to dominate in different lamprey species with the most abundant and common genus Aeromonas, which is also present in water. The representatives of the former family, Enterobacteriaceae (currently the order Enterobacterales [20]), have also been identified, but the presence of EC has not been indicated [21,22,23,24]. Tetlock et al. (2012) [22] isolated FS from sea lamprey gut tissue samples; however, the genus Enterococcus was not detected using the 16S rRNA metagenomic clone library. Shavalier et al. (2021) [25] indicated different Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria-causing infections of some lamprey species inhabiting the Laurentian Great Lakes (USA) and neither EC nor FS were recognised as pathogens.

The results obtained by Pyrzanowski et al. (2025) [17] show that the EBL and the UBL respond differently to water pollution in the River Gać. In the section of the river affected by WWTP discharge, the UBL exhibited a higher population density and a larger average body length. It demonstrated greater tolerance to faecal contamination and microbiological pollution compared to the EBL.

The UBL is known for its ability to adjust to a variety of spawning habitats [19]. It appeared to be well adapted to sewage-polluted aquatic environments and did not eliminate faecal bacteria (particularly EC and FS) from its intestines, even during the winter when feeding activity is typically reduced. This may indicate a specific adaptation to sewage-derived pollution. Our results may suggest that mesophilic bacteria, including EC and FS, are somehow connected with the fitness of the UBL and may be beneficial for the animal host, when filtrated and absorbed from faecally polluted mud which may contain comparable or even larger amounts of EC and FS than water [26]. Domestic sewage contains mainly organic matter and bacteria that are deposited in sediment and possibly, may be utilised as an additional or easily available source of nutrition for lampreys, especially in winter. An intriguing observation by Moore and Potter (1976) [27] may support this hypothesis. The authors stated that in experiments conducted in laboratory conditions in tanks with a slight current, the EBL ammocoetes were able to gain 0.5% weight when fed with an exceptionally high concentration (1 × 108 cells/mL) of EC for 60 days.

The ability of lampreys to accumulate the IMs from their environment has been reported recently. Kalan et al. (2023) [28] observed that Pacific lampreys (Entosphenus tridentatus) could effectively remove suspended EC from water in aquaria and potentially improve the water quality in its habitat. However, the authors did not investigate the accumulation of these bacteria in the lampreys’ intestinal tract.

The contrasting responses of the two lamprey species to sewage pollution suggest that such environmental conditions may promote the expansion of the UBL while contributing to the decline of the EBL in areas where their habitats overlap [17], as was observed by Jażdżewski et al. (2016) [18]. Indeed, the EBL prefers to live in oligotrophic and β-mesosaprobic zones of running water. Its larvae are considered to be bioindicators of water quality and environmental conditions [29]. These observations are supported by the findings of Pyrzanowski et al. (2025) [17], who reported that the UBL was the dominant species and reached a higher abundance than the EBL in the polluted section of the River Gać (downstream of the municipal WWTP discharge). Moreover, the UBL attained the largest average body length, while the EBL exhibited reduced growth in polluted water. Jażdżewski et al. (2016) [18] reported that the UBL increase its populations and replace the EBL in some habitats, which is reflected by our results showing high levels of faecal mesophilic bacteria present in the UBL intestines.

4. Conclusions

The UBL has been shown to present better adaptation skills to the environment polluted by effluents from WWTPs compared to the EBL co-occurring in the same section of the River Gać. Its high capacity to survive in water contaminated by domestic and faecal waste may be connected with the effective absorption and accumulation of the allochthonous mesophilic bacteria coming from warm-blooded animals, which are highly abundant in polluted water. WWTPs that work more effectively should help to avoid contamination of the river environment. However, the incoming microorganisms polluting the water may be an efficient source of nutrition to the burrowing UBL.

The necessarily small number of these protected animals collected for this study prevents us from drawing far-reaching conclusions. The fact that we found great numbers of live EC, FS, and other mesophiles existing in the UBL larvae midgut throughout all seasons of the year encourages further research to analyse the mechanisms influencing the amounts of the IMs in the UBL midgut and to determine whether these bacteria may function as probiotic symbionts of the host. Then, deeper insights into the seasonal changes in the UBL gut microbiome will also be possible.

To the best of our knowledge, our work is the first report on the microbiota living in the gut of the UBL.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17243537/s1, Table S1: Tukey’s HSD post hoc comparisons of total viable counts (TVC) of mesophilic and psychrophilic bacteria and indicator microorganisms: E. coli (EC) and faecal streptococci (FS) numbers in Eudontomyzon mariae (Ukrainian brook lamprey, UBL) and Lampetra planeri (European brook lamprey, EBL) larvae midgut content (two-way ANOVA) in studied seasons. All tests are significant at p ≤ 0.01 (bolded); Table S2: Dataset file.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P., D.D. and M.M.; methodology, M.M., J.G., K.P., G.Z. and D.D.; formal analysis, K.P.; investigation, M.M., J.G., K.P., G.Z. and D.D.; resources, M.M., J.G., K.P., G.Z. and D.D.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M. and D.D.; writing—review and editing, M.M., J.G., K.P. and D.D.; visualisation, M.M. and K.P. Author M.P. passed away prior to the publication of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Iwona Grzejdziak from the Department of Biology of Bacteria, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz, for her kind technical assistance in the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BEA | Bile esculin azide |

| CFU | Colony-forming unit |

| EC | Escherichia coli |

| EBL | European brook lamprey |

| FS | Faecal streptococcus |

| IM | Indicator microorganism |

| PCA | Plate count agar |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SEM | Standard error of the mean |

| UBL | Ukrainian brook lamprey |

| WWTP | Wastewater treatment plant |

References

- McCallum, E.S.; Nikel, K.E.; Mehdi, H.; Du, S.N.N.; Bowman, J.E.; Midwood, J.D.; Kidd, K.A.; Scott, G.R.; Balshine, S. Municipal wastewater effluent affects fish communities: A multi-year study involving two wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1730–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holeton, C.; Chambers, P.A.; Grace, L. Wastewater release and its impacts on Canadian waters. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2011, 68, 1836–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diesbourg, E.E.; Kidd, K.A.; Perrotta, B.G. Effects of municipal wastewater effluents on the invertebrate microbiomes of an aquatic-riparian food web. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 372, 125948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, P.C.; Borowska, E.; Schwartz, T.; Horn, H. Impact of the particulate matter from wastewater discharge on the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes and facultative pathogenic bacteria in downstream river sediments. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, W.; Sajnani, S.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, H.; Xu, Y. Evaluating the Ecological Impact of Wastewater Discharges on Microbial and Contaminant Dynamics in Rivers. Water 2024, 16, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liu, X.; Wei, H.; Chen, X.; Gong, N.; Ahmad, S.; Lee, T.; Ismail, S.; Ni, S.Q. Insight into impact of sewage discharge on microbial dynamics and pathogenicity in river ecosystem. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, R.; Wrzesiński, D. Detecting patterns of changes in river water temperature in Poland. Water 2020, 12, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łaszewski, M. Seasonal differentiation of water temperature on the example of lowland Mazovian rivers. Przegląd Geogr. 2020, 92, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiraldi, C.; De Rosa, M. Mesophilic Organisms. In Encyclopedia of Membranes; Drioli, E., Giorno, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rompré, A.; Servais, P.; Baudart, J.; de-Roubin, M.R.; Laurent, P. Detection and enumeration of coliforms in drinking water: Current methods and emerging approaches. J. Microbiol. Methods 2002, 49, 31–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Ganesh, A. Water quality indicators: Bacteria, coliphages, enteric viruses. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2013, 23, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, G.; Bharagava, R.N.; Kaithwas, G.; Raj, A. Microbial indicators, pathogens and methods for their monitoring in water environment. J. Water Health 2015, 13, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pottinger, T.G.; Henrys, P.A.; Williams, R.J.; Matthiessen, P. The stress response of three-spined sticklebacks is modified in proportion to effluent exposure downstream of wastewater treatment works. Aquat. Toxicol. 2013, 126, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetreault, G.R.; Brown, C.J.; Bennett, C.J.; Oakes, K.D.; McMaster, M.E.; Servos, M.R. Fish community responses to multiple municipal wastewater inputs in a watershed. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2013, 9, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahamonde, P.A.; McMaster, M.E.; Servos, M.R.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Munkittrick, K.R. Molecular pathways associated with the intersex condition in rainbow darter (Etheostoma caeruleum) following exposures to municipal wastewater in the Grand River basin, ON, Canada. Part B. Aquat. Toxicol. 2015, 159, 302–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zięba, G.; Moryl, M.; Drzewiecka, D.; Przybylski, M.; Pyrzanowski, K.; Grabowska, J. Effects of Domestic Pollution on European Brook Lamprey Ammocoetes in a Lowland River: Insights from Microbiological Analysis. Water 2024, 16, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyrzanowski, K.; Zięba, G.; Marszał, L.; Leśniak, M.; Banasiak, D.; Przybylski, M. Do Endangered Lampreys Benefit from Water Pollution? Effect of Municipal Sewage Treatment Plant Operation on Growth and Abundance of the Ukrainian Brook Lamprey and the European Brook Lamprey. Water 2025, 17, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jażdżewski, M.; Marszał, L.; Przybylski, M. Habitat preferences of The Ukrainian brook lamprey Eudontomyzon mariae ammocoetes in the lowland rivers of Central Europe. J. Fish Biol. 2016, 88, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, B.A.; Holcik, J. New data on the geographic distribution and ecology of the Ukrainian brook lamprey, Eudontomyzon mariae (Berg, 1931). Folia Zool. Praha 2006, 55, 282. [Google Scholar]

- Adeolu, M.; Alnajar, S.; Naushad, S.S.; Gupta, R. Genome-based phylogeny and taxonomy of the ‘Enterobacteriales’: Proposal for Enterobacterales ord. nov. divided into the families Enterobacteriaceae, Erwiniaceae fam. nov., Pectobacteriaceae fam. nov., Yersiniaceae fam. nov., Hafniaceae fam. nov., Morganellaceae fam. nov., and Budviciaceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 5575–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, P.A.; Glenn, A.R.; Potter, I.C. The Bacterial Flora of the Gut Contents and Environment of Larval Lampreys. Acta Zool. 1980, 61, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetlock, A.; Yost, C.K.; Stavrinides, J.; Manzon, R.G. Changes in the gut microbiome of the sea lamprey during metamorphosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7638–7644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xie, W.; Li, Q. Characterisation of the bacterial community structures in the intestine of Lampetra morii. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2016, 109, 979–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathai, P.P.; Byappanahalli, M.N.; Johnson, N.S.; Sadowsky, M.J. Gut Microbiota Associated with Different Sea Lamprey (Petromyzon marinus) Life Stages. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 706683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shavalier, M.A.; Faisal, M.; Moser, M.L.; Loch, T.P. Parasites and microbial infections of lamprey (order Petromyzontiformes Berg 1940): A review of existing knowledge and recent studies. J. Great Lakes Res. 2021, 47, S90–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung-Cheung, A.K. Comparison of Bacterial Levels from Water and Sediments among Upper and Lower Areas of Guion Creek. Int. J. Soil Sediment Water 2009, 2, 1–15. Available online: http://scholarworks.umass.edu/intljssw/vol2/iss3/3 (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Moore, J.W.; Potter, I.C. A laboratory study on the feeding of larvae of the brook lamprey Lampetra planeri (Bloch). J. Anim. Ecol. 1976, 45, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalan, P.; Steinbeck, J.; Otte, F.; Lema, S.C.; White, C. Filter-feeding Pacific Lamprey (Entosphenus tridentatus) ammocetes can reduce suspended concentrations of E. coli Bacteria. Fishes 2023, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanel, L.; Andreska, J.; Valentinovich Dyldin, Y. Lampreys in Human Life, Their Cultural and Folklore Importance. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 10, 300–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).