Carbon-Water Coupling and Ecosystem Resilience to Drought in the Yili-Balkhash Basin, Central Asia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

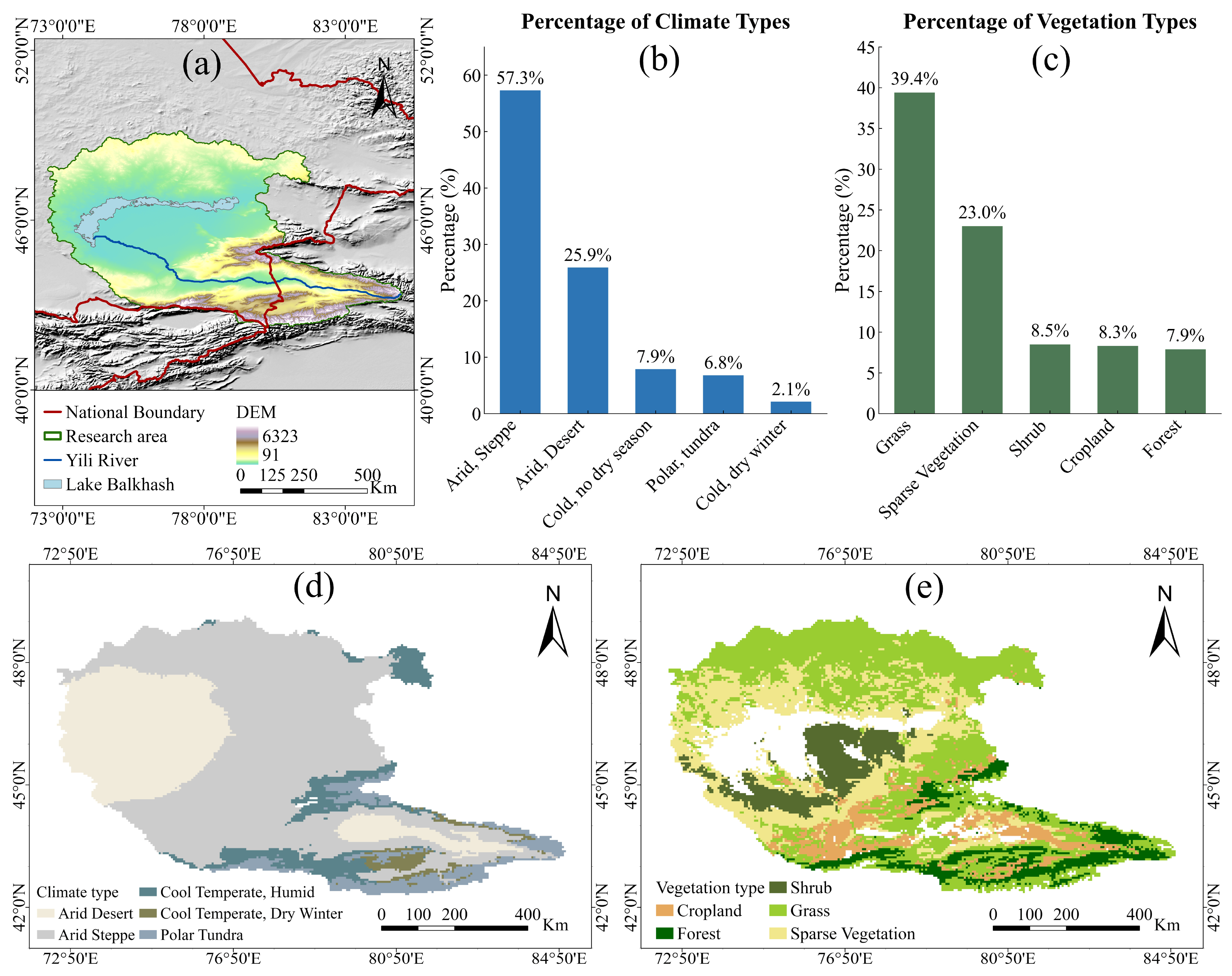

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

2.2.1. GPP and ET Datasets

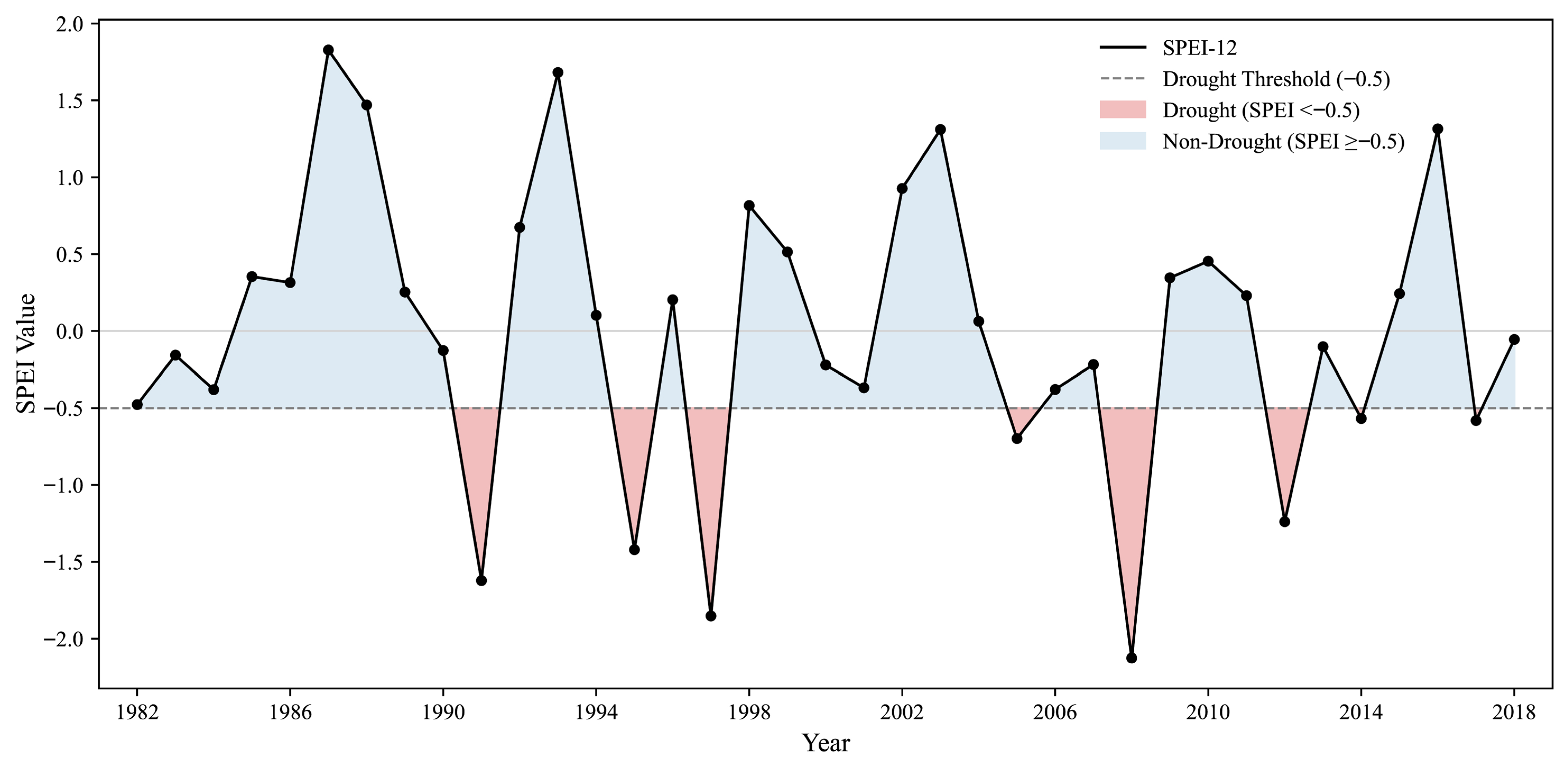

2.2.2. SPEI Data

2.2.3. ERA5 Data

2.2.4. Land Cover Data

2.2.5. Climate Zone Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Ecosystem Water Use Efficiency

2.3.2. Dominant Process Classification

2.3.3. Vapor Pressure Deficit

2.3.4. Elastic Net Regression

2.3.5. Ecosystem Resilience Assessment

- Resilient: Rd ≥ 1.0

- Slightly non-resilient: 0.9 ≤ Rd < 1.0

- Moderately non-resilient: 0.8 ≤ Rd < 0.9

- Severely non-resilient: Rd < 0.8

2.3.6. Attribution of Resilience Drivers

3. Results

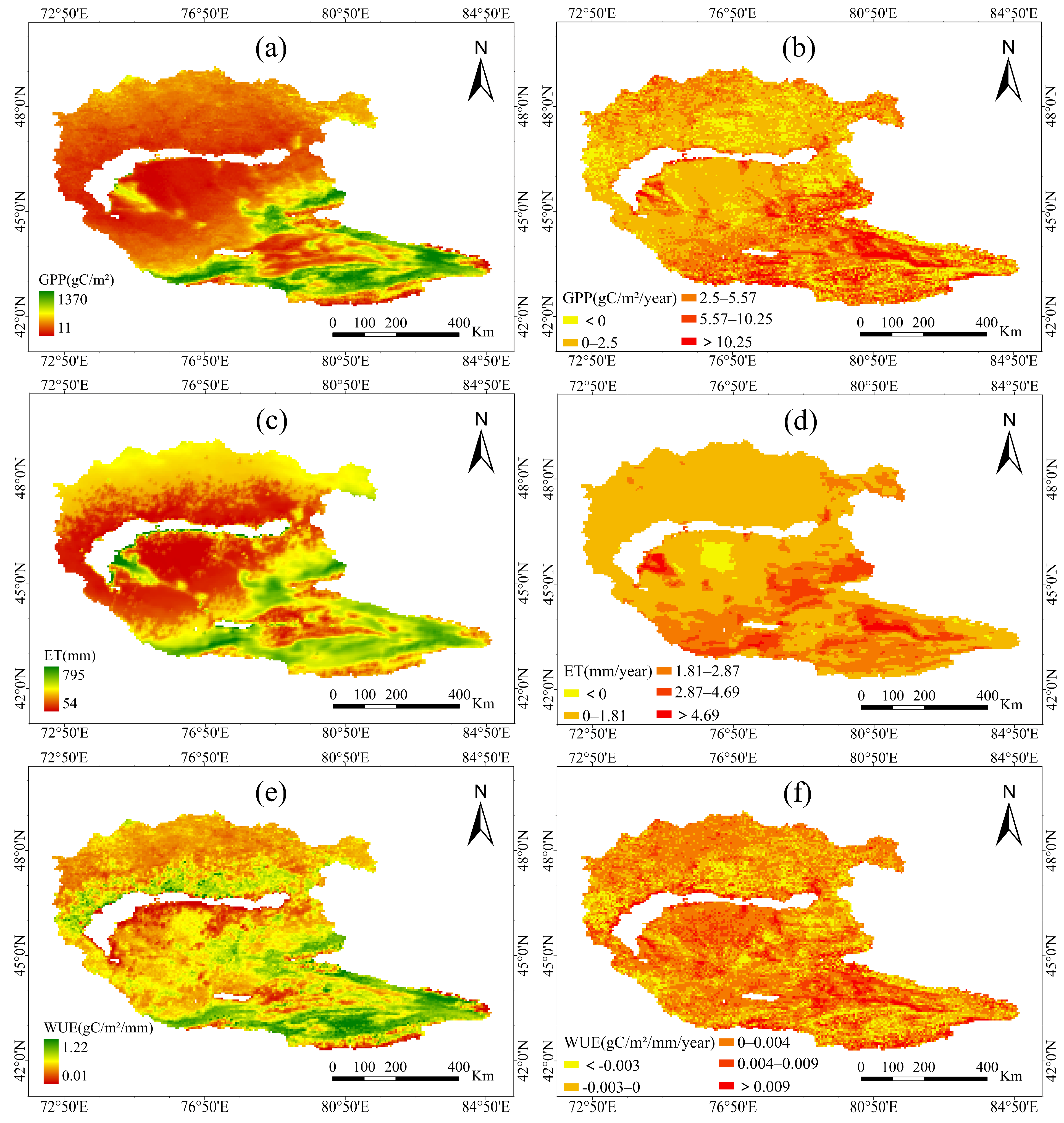

3.1. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of GPP, ET, and WUE

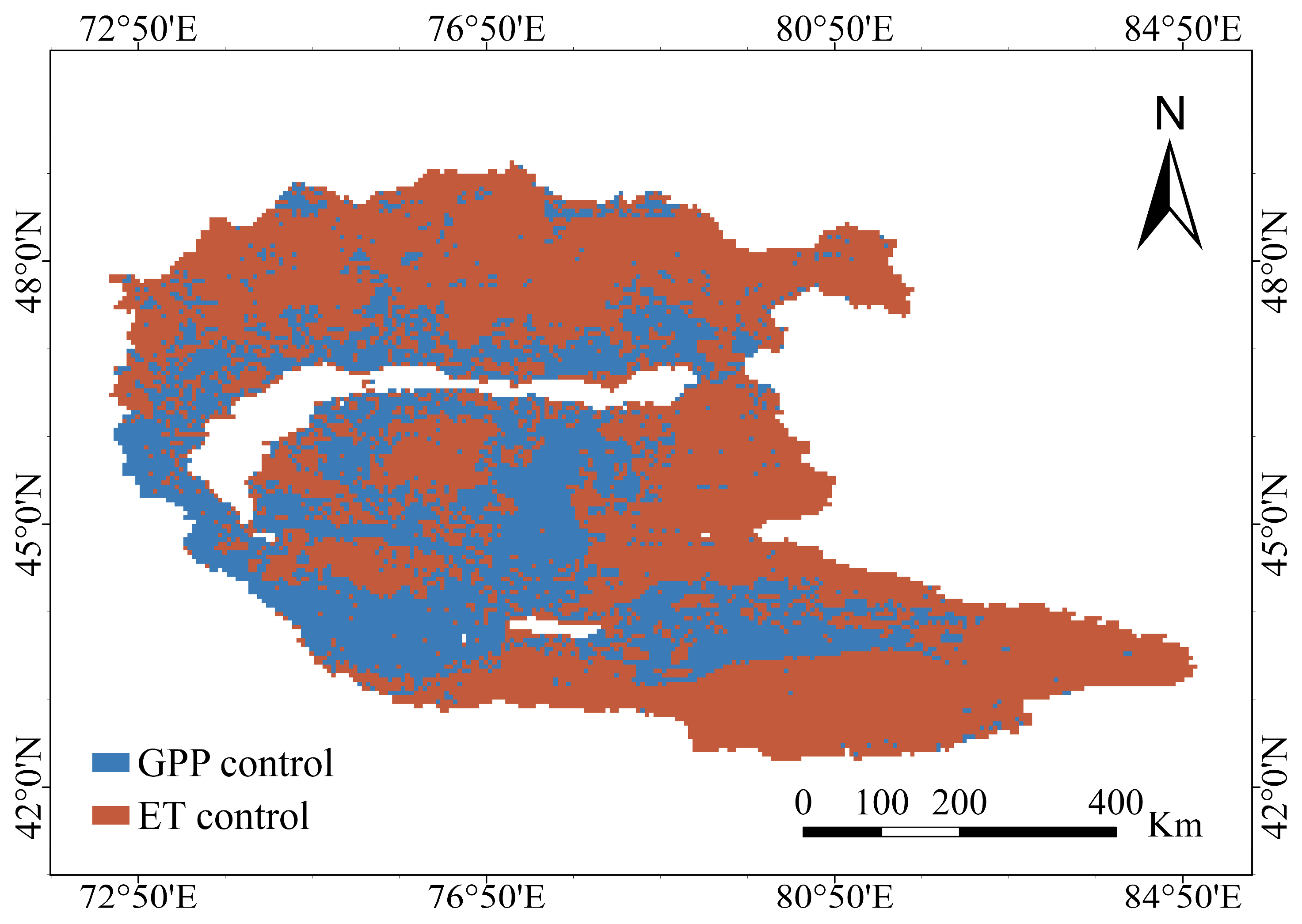

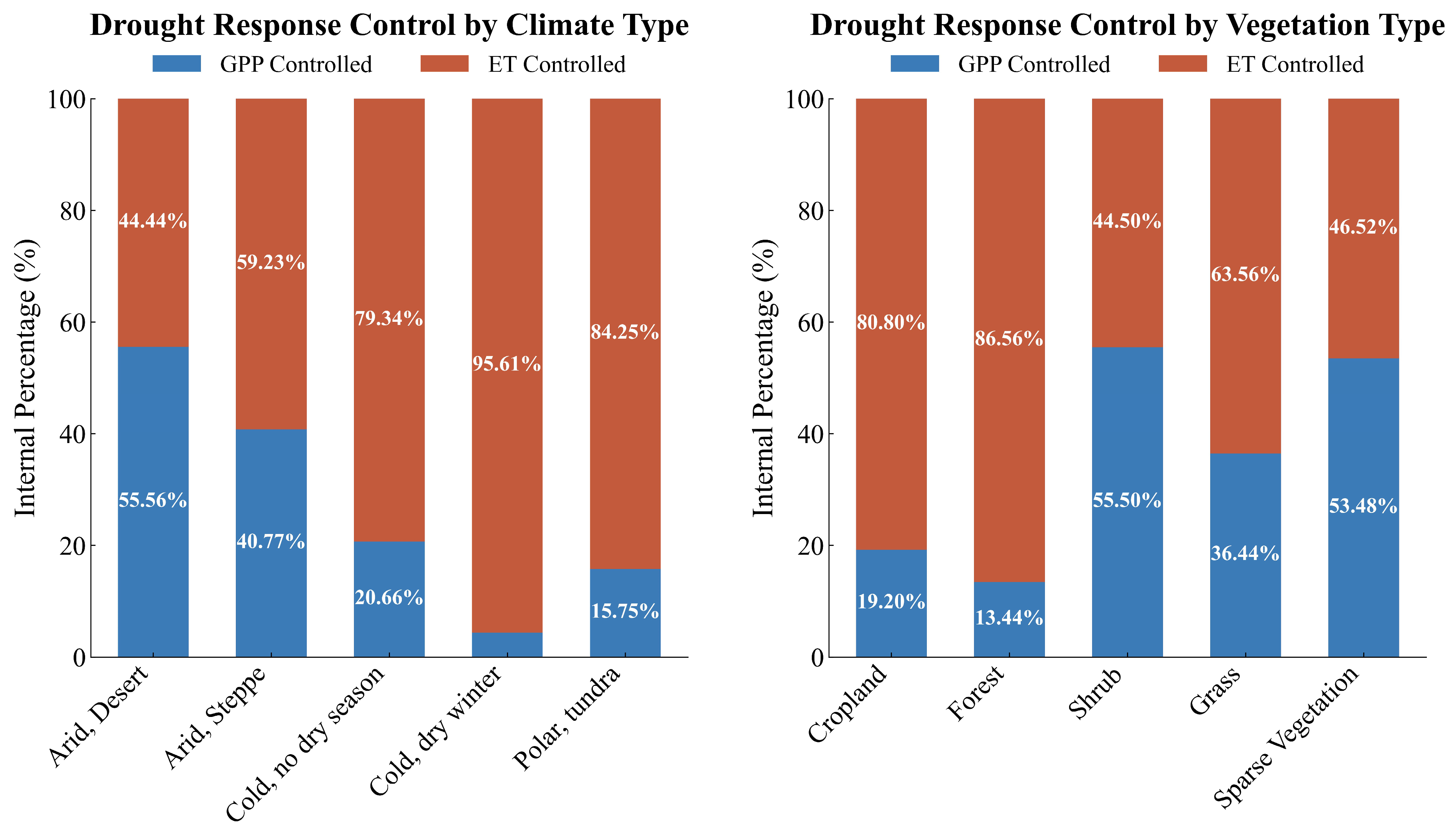

3.2. Dominant Control of GPP vs. ET on WUE Response to Drought

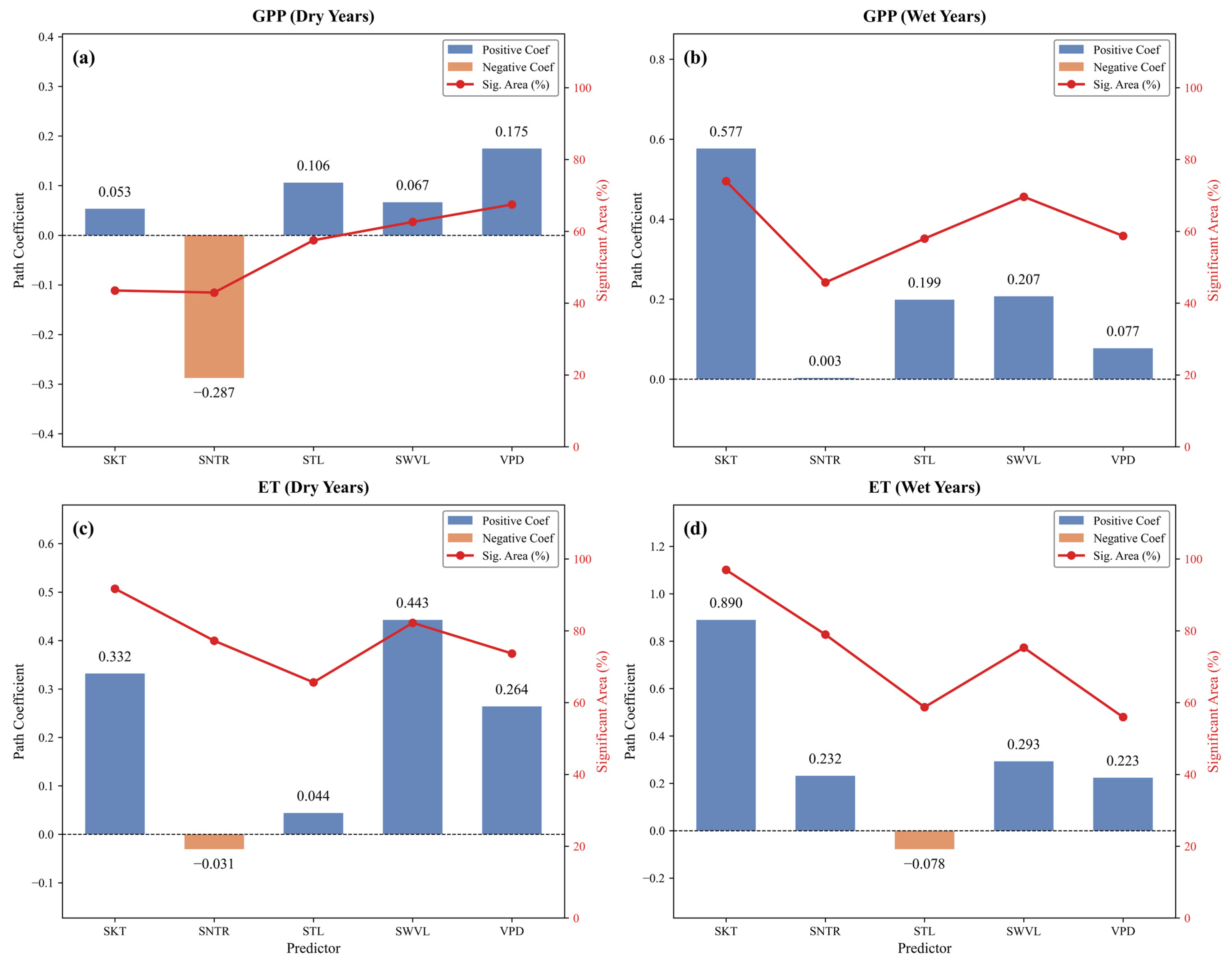

3.3. Core Driving Mechanisms: Dynamic Changes Under Dry and Wet Scenarios

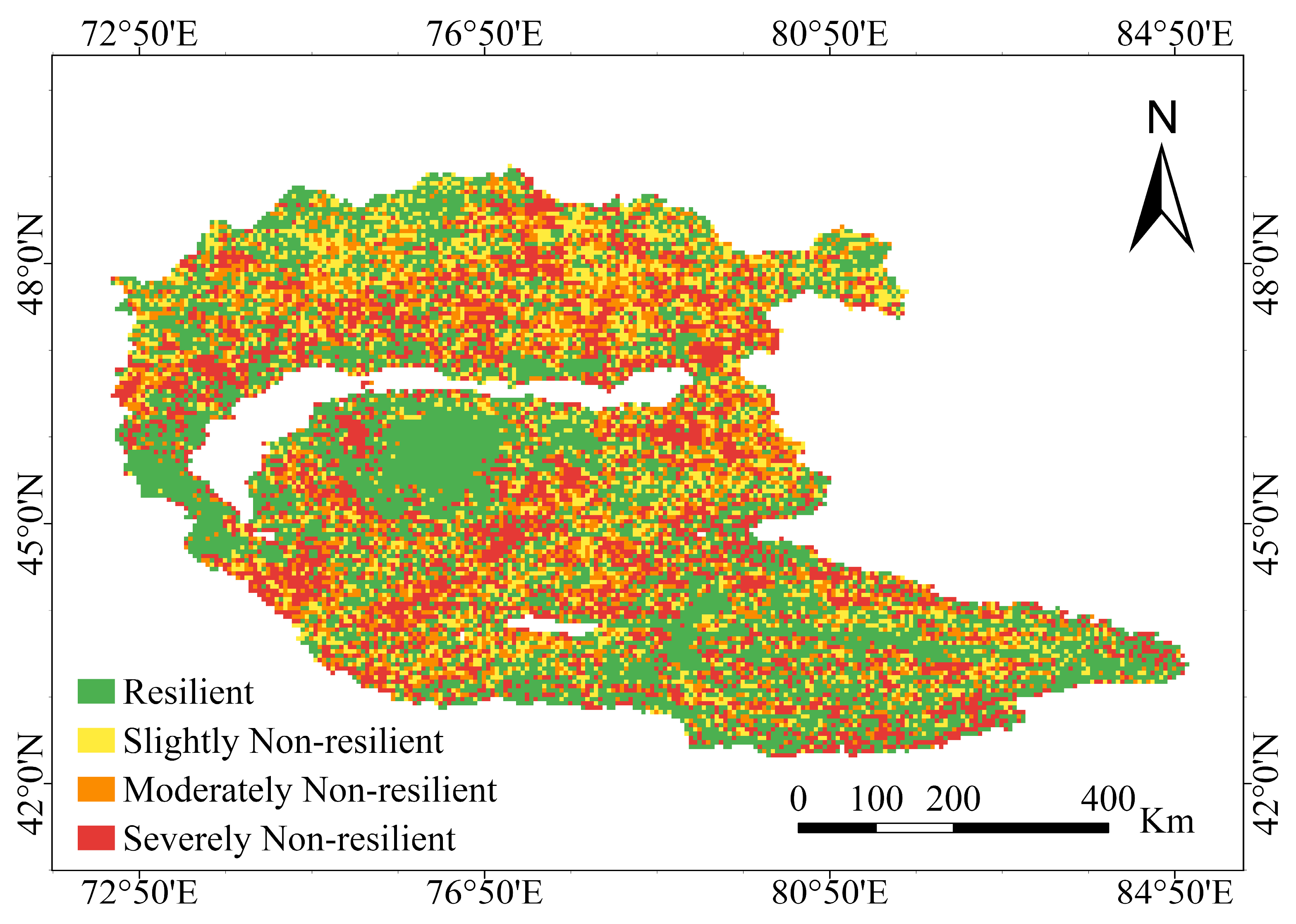

3.4. Spatial Distribution of Ecosystem Resilience

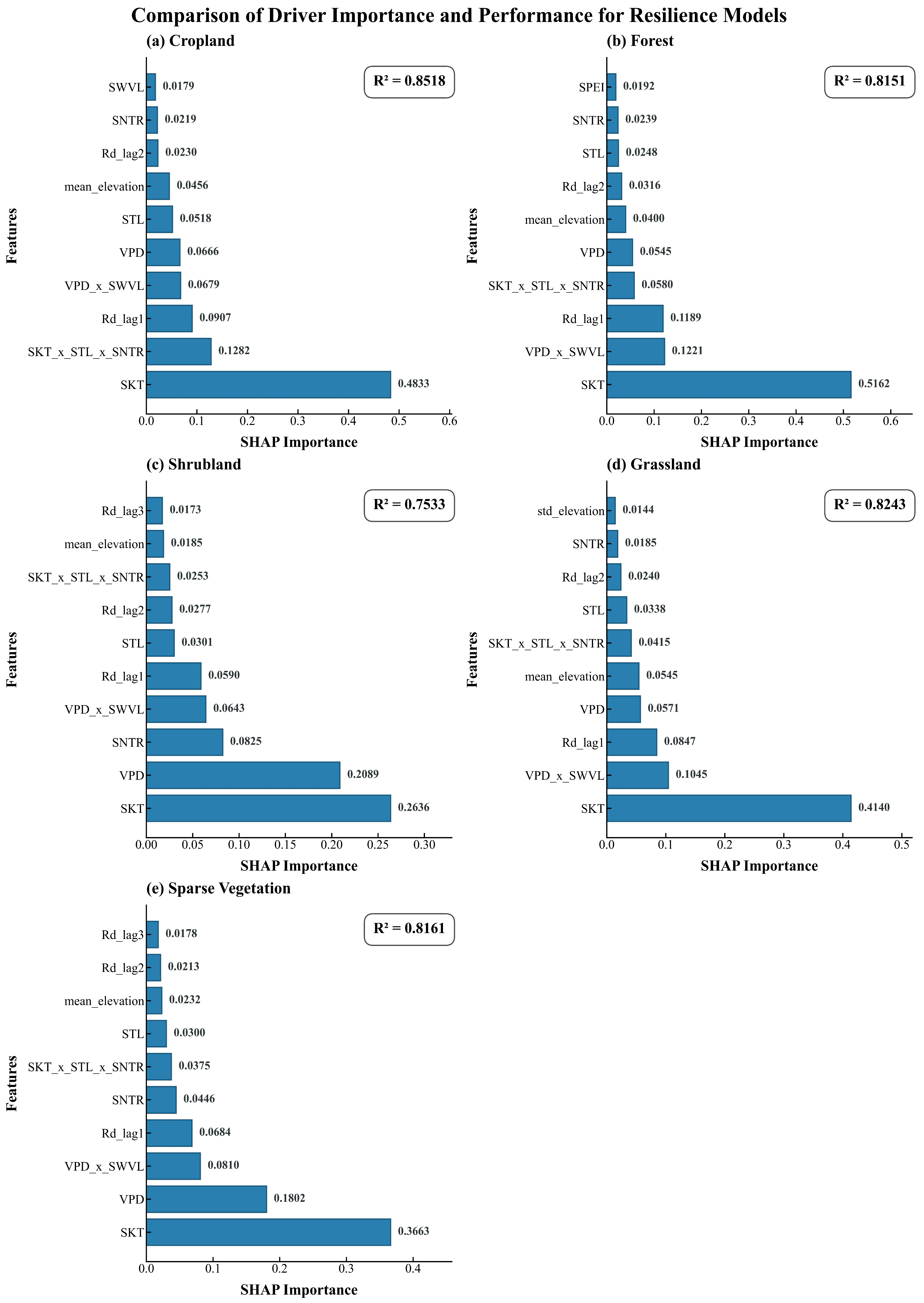

3.5. Attribution of Ecological Resilience Drivers

4. Discussion

4.1. Divergent Carbon-Water Coupling Trends in the YBB

4.2. Asymmetric Responses of GPP and ET and Their Ecological Implications

4.3. Spatial Heterogeneity of Ecosystem Resilience and Its Driving Mechanisms

4.4. Limitations and Future Outlook

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Cai, W.; Ullah, S.; Yan, L.; Lin, Y. Remote sensing of ecosystem water use efficiency: A review of direct and indirect estimation methods. Remote. Sens. 2021, 13, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wang, T. Evaluating cumulative drought effect on global vegetation photosynthesis using numerous GPP products. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 908875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, R.; Qin, M.; Jiang, P.; Yang, F.; Liu, B.; Zhu, M.; Fang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Shang, B. Vegetation and evapotranspiration responses to increased atmospheric vapor pressure deficit across the global forest. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Guan, H.; Batelaan, O.; McVicar, T.R.; Long, D.; Piao, S.; Liang, W.; Liu, B.; Jin, Z.; Simmons, C.T. Contrasting responses of water use efficiency to drought across global terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 23284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Rentch, J.S.; Sun, P.; Lu, C. Global gross primary productivity and water use efficiency changes under drought stress. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 014016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Martínez, D.; Holwerda, F.; Holmes, T.R.; Yépez, E.A.; Hain, C.R.; Alvarado-Barrientos, S.; Ángeles-Pérez, G.; Arredondo-Moreno, T.; Delgado-Balbuena, J.; Figueroa-Espinoza, B.; et al. Evaluation of remote sensing-based evapotranspiration products at low-latitude eddy covariance sites. J. Hydrol. 2022, 610, 127786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shveytser, V.; Stoy, P.C.; Butterworth, B.; Wiesner, S.; Skaggs, T.H.; Murphy, B.; Wutzler, T.; El-Madany, T.S.; Desai, A.R. Evaporation and transpiration from multiple proximal forests and wetlands. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2022WR033757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Quezada, J.F.; Trejo, D.; Lopatin, J.; Aguilera, D.; Osborne, B.; Galleguillos, M.; Zattera, L.; Celis-Diez, J.L.; Armesto, J.J. Drivers of ecosystem water use efficiency in a temperate rainforest and a peatland in southern South America. EGUsphere 2023, 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, R.L.; Huxman, T.E.; Cable, W.L.; Emmerich, W.E. Partitioning of evapotranspiration and its relation to carbon dioxide exchange in a Chihuahuan Desert shrubland. Hydrol. Process. 2006, 20, 3227–3243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, G.; Sun, H.; Ma, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, H.; Mei, L. Effects of drought stress on photosynthesis and photosynthetic electron transport chain in young apple tree leaves. Biol. Open 2018, 7, bio035279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yan, S.; Ciais, P.; Wigneron, J.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Fu, Z.; Ma, H.; Liang, Z.; Wei, F.; et al. Exploring complex water stress–gross primary production relationships: Impact of climatic drivers, main effects, and interactive effects. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4110–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Ciais, P.; Prentice, I.C.; Gentine, P.; Makowski, D.; Bastos, A.; Luo, X.; Green, J.K.; Stoy, P.C.; Yang, H.; et al. Atmospheric dryness reduces photosynthesis along a large range of soil water deficits. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Q.; Yu, R.; Guo, L. Evaluation of forest ecosystem resilience to drought considering lagged effects of drought. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e70281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, L.M.; Bahn, M. Drought legacies and ecosystem responses to subsequent drought. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 5086–5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britton, A.; Graham, G.; Woloszyn, M. Exploring relationships between drought indices and ecological drought impacts using machine learning and explainable AI. J. Appl. Serv. Clim. 2024, 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zhang, Q.; Jia, Y.; Tang, H.; Zhang, H. Attribution of hydrological droughts in large river-connected lakes: Insights from an explainable machine learning model. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 952, 175999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Bai, Y.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Henchiri, M.; Seka, A.M.; Nanzad, L. Drought monitoring and performance evaluation based on machine learning fusion of multi-source remote sensing drought factors. Remote. Sens. 2022, 14, 6398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Chen, Y. Influences of recent climate change and human activities on water storage variations in Central Asia. J. Hydrol. 2017, 544, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Chen, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, S. Climate change with elevation and its potential impact on water resources in the Tianshan Mountains, Central Asia. Glob. Planet. Change 2015, 135, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zeng, B.; Cao, Y.; Li, F.; Tang, Z.; Qi, J. Human activities have markedly altered the pattern and trend of net primary production in the Ili River basin of Northwest China under current climate change. Land Degrad. Dev. 2022, 33, 2585–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yegizbayeva, A.; Koshim, A.G.; Bekmuhamedov, N.; Aliaskarov, D.T.; Alimzhanova, N.; Aitekeyeva, N. Satellite-based drought assessment in the endorheic basin of Lake Balkhash. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 11, 1291993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, T.; Paltan, H.; Sternberg, T.; Wheeler, K. Evaluating vulnerability of Central Asian water resources under uncertain climate and development conditions: The case of the Ili-Balkhash Basin. Water 2021, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevs, N.; Rozi, A.; Kubal, C.; Abdusalih, N. Water consumption of agriculture and natural ecosystems along the Tarim River, China. Geo-Oeko 2013, 34, 50–76. [Google Scholar]

- Karina, Z. Kazakhstan’s National Priorities and Political and Institutional Response to the Water-Energy-Climate-Food Nexus: The Effects on the Ili-Balkhash Basin; CEU, Budapest College: Budapest, Hungary, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, W.; Liu, S.; Yu, G.; Bonnefond, J.-M.; Chen, J.; Davis, K.; Desai, A.R.; Goldstein, A.H.; Gianelle, D.; Rossi, F.; et al. Global estimates of evapotranspiration and gross primary production based on MODIS and global meteorology data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 1416–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Liang, S.; Li, X.; Hong, Y.; Fisher, J.B.; Zhang, N.; Chen, J.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. Bayesian multimodel estimation of global terrestrial latent heat flux from eddy covariance, meteorological, and satellite observations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2014, 119, 4521–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beguería, S.; Serrano, S.M.V.; Reig-Gracia, F.; Garcés, B.L. SPEIbase v.2.10 [Dataset]: A Comprehensive Tool for Global Drought Analysis. Digital. CSIC 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration-Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements; FAO Irrigation and Drainage Paper 56; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, T.; Xu, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, L. GLC_FCS30D: The first global 30 m land-cover dynamics monitoring product with a fine classification system for the period from 1985 to 2022 generated using dense-time-series Landsat imagery and the continuous change-detection method. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2024, 16, 1353–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. World Map of the Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Updated. Meteorol. Z. 2006, 15, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Zou, J.; Ding, J.; Zou, W.; Yahefujiang, H.J.F. Stronger cumulative than lagged effects of drought on vegetation in Central Asia. Forests 2023, 14, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Piao, S.; Myneni, R.B.; Huang, M.; Zeng, Z.; Canadell, J.G.; Ciais, P.; Sitch, S.; Friedlingstein, P.; Arneth, A.; et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 2016, 6, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Park, T.; Chen, C.; Lian, X.; He, Y.; Bjerke, J.W.; Chen, A.; Ciais, P.; Tømmervik, H.; et al. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, E.A.; Rogers, A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising [CO2]: Mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, T.F.; Hollinger, D.Y.; Bohrer, G.; Dragoni, D.; Munger, J.W.; Schmid, H.P.; Richardson, A.D. Increase in forest water-use efficiency as atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations rise. Nature 2013, 499, 324–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donohue, R.J.; Roderick, M.L.; McVicar, T.R.; Farquhar, G.D. Impact of CO2 fertilization on maximum foliage cover across the globe’s warm, arid environments. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2013, 40, 3031–3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Piao, S.; Sun, Y.; Ciais, P.; Cheng, L.; Mao, J.; Poulter, B.; Shi, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y. Change in terrestrial ecosystem water-use efficiency over the last three decades. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 2366–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Zheng, X.-J.; Yin, L.; Wang, Y. Forest stand factors determine the rainfall pattern of crown allocation of Picea schrenkiana in the northern slope of Mount Bogda, Tianshan Range, China. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1113354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y. Age-effect radial growth responses of Picea schrenkiana to climate change in the eastern Tianshan Mountains, Northwest China. Forests 2017, 8, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, Q.; Ling, H.; Zhao, H.; Li, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, G. Do extreme climate events cause the degradation of Malus sieversii forests in China? Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 608211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlyn, B.E.; Duursma, R.A.; Eamus, D.; Ellsworth, D.S.; Prentice, I.C.; Barton, C.V.M.; Crous, K.Y.; DE Angelis, P.; Freeman, M.; Wingate, L. Reconciling the optimal and empirical approaches to modelling stomatal conductance. Glob. Change Biol. 2011, 17, 2134–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.; Reichstein, M.; Ciais, P.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Sheffield, J.; Goulden, M.L.; Bonan, G.; Cescatti, A.; Chen, J.; De Jeu, R.; et al. Recent decline in the global land evapotranspiration trend due to limited moisture supply. Nature 2010, 467, 951–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesinger, W.H.; Jasechko, S. Transpiration in the global water cycle. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 189, 115–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Zheng, Y.; Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Lombardozzi, D.; Wang, Y.; Ryu, Y.; Chen, G.; Dong, W.; Hu, Z.; et al. Increased atmospheric vapor pressure deficit reduces global vegetation growth. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senf, C.; Seidl, R. Persistent impacts of the 2018 drought on forest disturbance regimes in Europe. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 5223–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemani, R.R.; Keeling, C.D.; Hashimoto, H.; Jolly, W.M.; Piper, S.C.; Tucker, C.J.; Myneni, R.B.; Running, S.W. Climate-driven increases in global terrestrial net primary production from 1982 to 1999. Science 2003, 300, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beer, C.; Ciais, P.; Reichstein, M.; Baldocchi, D.; Law, B.E.; Papale, D.; Soussana, J.; Ammann, C.; Buchmann, N.; Frank, D.; et al. Temporal and among-site variability of inherent water use efficiency at the ecosystem level. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2009, 23, GB2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gudmundsson, L.; Hauser, M.; Qin, D.; Li, S.; Seneviratne, S.I. Soil moisture dominates dryness stress on ecosystem production globally. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; Carpenter, S.; Foley, J.A.; Folke, C.; Walker, B. Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature 2001, 413, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazol, A.; Camarero, J.J.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Sánchez-Salguero, R.; Gutiérrez, E.; de Luis, M.; Sangüesa-Barreda, G.; Novak, K.; Rozas, V.; Tíscar, P.A.; et al. Forest resilience to drought varies across biomes. Glob. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 2143–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, B.; Dong, Z.; Li, G.; Li, S. Variations in water use strategies of Tamarix ramosissima at coppice dunes along a precipitation gradient in desert regions of northwest China. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1408943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zheng, X.J.; Tang, L.S.; Li, Y. Dynamics of water usage in Haloxylon ammodendron in the southern edge of the Gurbantünggüt Desert. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2014, 38, 1214–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Li, Y.; Xu, H. Seasonal variation in plant hydraulic traits of two co-occurring desert shrubs, Tamarix ramosissima and Haloxylon ammodendron, with different rooting patterns. Ecol. Res. 2011, 26, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reich, P.B. The world-wide ‘fast–slow’plant economics spectrum: A traits manifesto. J. Ecol. 2014, 102, 275–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Chenchouni, H.; Bachelet, D.; McDowell, N.; Vennetier, M.; Kitzberger, T.; Rigling, A.; Breshears, D.D.; Hogg, E.H.; et al. A global overview of drought and heat-induced tree mortality reveals emerging climate change risks for forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 660–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choat, B.; Brodribb, T.J.; Brodersen, C.R.; Duursma, R.A.; López, R.; Medlyn, B.E. Triggers of tree mortality under drought. Nature 2018, 558, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Naylor, R.; Polasky, S. Agricultural sustainability and intensive production practices. Nature 2002, 418, 671–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isbell, F.; Craven, D.; Connolly, J.; Loreau, M.; Schmid, B.; Beierkuhnlein, C.; Bezemer, T.M.; Bonin, C.; Bruelheide, H.; De Luca, E.; et al. Biodiversity increases the resistance of ecosystem productivity to climate extremes. Nature 2015, 526, 574–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zscheischler, J.; Westra, S.; Van Den Hurk, B.J.J.M.; Seneviratne, S.I.; Ward, P.J.; Pitman, A.; AghaKouchak, A.; Bresch, D.N.; Leonard, M.; Wahl, T.; et al. Future climate risk from compound events. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park Williams, A.; Allen, C.D.; Macalady, A.K.; Griffin, D.; Woodhouse, C.A.; Meko, D.M.; Swetnam, T.W.; Rauscher, S.A.; Seager, R.; Grissino-Mayer, H.D.; et al. Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderegg, W.R.L.; Berry, J.A.; Smith, D.D.; Sperry, J.S.; Anderegg, L.D.L.; Field, C.B. The roles of hydraulic and carbon stress in a widespread climate-induced forest die-off. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, M.; Westra, S.; Phatak, A.; Lambert, M.; van den Hurk, B.; McInnes, K.; Risbey, J.; Schuster, S.; Jakob, D.; Stafford-Smith, M. A compound event framework for understanding extreme impacts. WIREs Clim. Change 2014, 5, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zscheischler, J.; Seneviratne, S.I. Dependence of drivers affects risks associated with compound events. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDowell, N.; Pockman, W.T.; Allen, C.D.; Breshears, D.D.; Cobb, N.; Kolb, T.; Plaut, J.; Sperry, J.; West, A.; Williams, D.G.; et al. Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: Why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought? New Phytol. 2008, 178, 719–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döll, P. Impact of climate change and variability on irrigation requirements: A global perspective. Clim. Change 2002, 54, 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Roberts, M.J.; Schlenker, W.; Braun, N.; Little, B.B.; Rejesus, R.M.; Hammer, G.L. Greater sensitivity to drought accompanies maize yield increase in the US Midwest. Science 2014, 344, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Mean Spatial Distribution | Temporal Trends | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPP (gC·m−2) | ET (mm) | WUE (gC·m−2·mm−1) | GPP (gC·m−2·yr−1) | ET (mm·yr−1) | WUE (gC·m−2·mm−1·yr−1) | ||

| vegetation type | Cropland | 563.978 | 358.780 | 1.505 | 5.5893 | 2.7488 | 0.0053 |

| Forest | 889.505 | 439.630 | 2.009 | 3.8734 | 2.2991 | −0.0006 | |

| Shrub | 116.738 | 116.217 | 1.122 | 1.4533 | 0.6114 | 0.0079 | |

| Grass | 359.084 | 282.381 | 1.253 | 2.4951 | 1.5852 | 0.0017 | |

| Sparse Vegetation | 197.727 | 172.769 | 1.247 | 1.9843 | 1.2543 | 0.0027 | |

| climate type | Arid, Desert | 221.806 | 195.329 | 1.177 | 2.4841 | 1.3206 | 0.0052 |

| Arid, Steppe | 316.492 | 248.123 | 1.252 | 2.3610 | 1.5135 | 0.0024 | |

| Cold, no dry season | 702.467 | 405.451 | 1.684 | 4.2214 | 2.3956 | 0.0014 | |

| Cold, dry winter | 901.908 | 417.090 | 2.149 | 3.4375 | 1.9635 | −0.0012 | |

| Polar, tundra | 396.716 | 284.777 | 1.323 | 4.5612 | 1.6230 | 0.0093 | |

| Cropland | Forest | Shrub | Grass | Sparse Vegetation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilient | 28.27% | 16.16% | 20.29% | 26.78% | 28.48% |

| Slightly non-resilient | 21.03% | 18.20% | 10.93% | 20.14% | 16.83% |

| Moderately non-resilient | 24.35% | 30.27% | 11.36% | 17.76% | 16.72% |

| Severely non-resilient | 26.35% | 35.37% | 57.43% | 35.31% | 37.97% |

| Resilience Index | 0.9457 | 0.9880 | 1.2699 | 0.9655 | 0.9785 |

| Arid, Desert | Arid, Steppe | Cold, No Dry Season | Cold, Dry Winter | Polar, Tundra | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resilient | 27.25% | 26.04% | 22.06% | 4.39% | 26.24% |

| Slightly non-resilient | 14.05% | 18.85% | 18.05% | 18.42% | 24.86% |

| Moderately non-resilient | 11.84% | 18.24% | 24.85% | 24.56% | 22.65% |

| Severely non-resilient | 46.86% | 36.51% | 35.05% | 52.63% | 26.24% |

| Resilience Index | 1.1105 | 0.9683 | 0.9619 | 0.9978 | 1.2239 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Z.; Cui, D.; Jiang, Z.; Yan, J.; Wu, Y.; Wen, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, L. Carbon-Water Coupling and Ecosystem Resilience to Drought in the Yili-Balkhash Basin, Central Asia. Water 2025, 17, 3535. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243535

Liu Z, Cui D, Jiang Z, Yan J, Wu Y, Wen M, Liu J, Liu L. Carbon-Water Coupling and Ecosystem Resilience to Drought in the Yili-Balkhash Basin, Central Asia. Water. 2025; 17(24):3535. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243535

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Zezheng, Dong Cui, Zhicheng Jiang, Jiangchao Yan, Yunhao Wu, Mengdie Wen, Junqi Liu, and Luyao Liu. 2025. "Carbon-Water Coupling and Ecosystem Resilience to Drought in the Yili-Balkhash Basin, Central Asia" Water 17, no. 24: 3535. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243535

APA StyleLiu, Z., Cui, D., Jiang, Z., Yan, J., Wu, Y., Wen, M., Liu, J., & Liu, L. (2025). Carbon-Water Coupling and Ecosystem Resilience to Drought in the Yili-Balkhash Basin, Central Asia. Water, 17(24), 3535. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243535