Abstract

Many studies have been conducted on wave and sediment movement with submerged dikes. However, the effect of a submerged dike’s height and orientation on hydrodynamics has not been thoroughly examined from the perspective of the marine ecology impact. This paper employs a two-dimensional numerical model to investigate effects of submerged dike height and orientation on flow, specifically flow velocity and cross-dike flux. The findings indicate that the most significant velocity variation occurs at a distance of approximately one-fifth of the dike length (0.2 L) from the dike head, when the flow is perpendicular to the dike and parallel to the coastline. And this area as the submerged dike’s protection zone will have the least impact on the surrounding environment. The change pattern of the flow velocity with the distance apart from the submerged dike varies for different submerged dike heights. A submerged dike height of 0.7 times the water depth (0.7 H) is a dividing value. Additionally, as the orientation angle increases, the cross-dike flux rises. From the perspective of the impact on the marine ecological environment, the design angle of the submerged dike should be as small as possible. The findings establish a theoretical hydrodynamic basis that may support future integrated studies on coastal zone management.

1. Introduction

Dikes, including emerged dikes and submerged dikes, are a kind of hydraulic structure that has long been employed to damp waves, redirect flows, safeguard coastlines, adjust water depth, and build local deposition [1]. Consequently, dikes are crucial and extensively implemented coastal engineering projects. Dikes are usually constructed at an angle to the coastline to redirect flow [2].

Many relevant investigations are focusing on emerged dikes. Emerged dike obstruction leads to a multidimensional turbulent flow pattern close to the structure, causing localized regions of steep velocity changes and sediment transport [3]. Weitbrecht et al. indicated that mass and momentum exchange occur in the vicinity of emerged dike heads [4]. J. W. et al. [5] described the analysis of 10 years of measurements together with a recently measured storm that included wave overtopping. Tomohiro Suzuki [6] showed that the vertical wall induces seaward velocity on the dike, which might be an extra risk during extreme events. Beji and Battjes [7] applied nonlinear shallow-water wave theories to investigate the transformation of periodic waves passing over a dike. Previous studies have revealed that the surrounding flow region can be split into three distinct zones [8]. Chen et al. [9] categorized the three zones concerning the dike length, defining them as Y = 2/3 L for the Dike Field Zone (DFZ), Y = 4/3 L for the Momentum Exchange Zone (MEZ), and Y = 3 L for the (Main-Stream Zone) MSZ (where Y is the channel bund width and L is the dike length). Sujantoko et al. [10] present a two-dimensional numerical analysis of the hydrodynamic performance of a submerged dike, focusing on the effects of slope and porosity on wave transmission and reflection. Ikha Magdalena and Owen Nathanael [11] introduce a mathematical model and demonstrate that submerged porous breakwaters effectively mitigate shoaling effects by attenuating wave amplitudes and reducing resonance risks.

Meanwhile, there are some studies on wave and sediment movement with submerged dikes. Harmonic generation past a submerged porous dike has been studied by experiments [12]. Altomare et al. [13] introduced a new “equivalent slope” concept to estimate average wave overtopping discharges on sea dikes with shallow and very shallow foreshores. Tsal et al. [14] studied the wave reflection coefficient of the submerged dike and the attenuation coefficient of wave energy by experiment. Sharifahmandian and Simons [15] published a numerical model that could predict the wave transmission coefficient in submerged dike space under regular waves in shallow water. Based on the RBF method, the model can accurately simulate wave motion near a submerged dike. Chen et al. [16] showed that the wave profile may become more asymmetrical when the wave propagates over the breakwater. Chai et al. [17] employed a 3D numerical model to investigate how dike shape and height affect sediment transport. Their results demonstrated that a narrower hexagonal dike outperforms rectangular designs, and suspended sediment concentration could be reduced by 30% when the height of dike varied from 0.3 m to 0.5 m. In a complementary study, Pang et al. [18] conducted flume experiments examining mud flotation at various dike elevations, fluid mud thickness variations, channel siltation, and sediment deposition upstream of submerged dikes. Their findings revealed that optimal sedimentation effects occur when the submerged dike height-to-depth ratio ranges from 0.2 to 0.5.

Compared with emerged dikes, submerged dikes have the advantages of requiring little engineering work and less investment, and having reduced impacts on the marine ecological environment. With the popularization of the national ecological civilization strategy, more ecologically friendly submerged dikes have attracted more and more attention. It is necessary to analyze the hydrodynamic characteristics of submerged dikes from the perspective of marine ecology impact. Therefore, studying the hydrodynamics near submerged dikes will have engineering and ecological significance. Studies of the current features around submerged dikes are usually based on specific projects. Xu et al. [19] studied the spatial–temporal variation characteristics of current velocity in the south dike of the Yangtze Estuary by using FVCOM, calculated the cross-dike flux, and analyzed the current change past the dike before and after the engineering. Li [20] studied the hydrodynamic environmental impact of the East China Sea Dike on Zhanjiang Bay, showing that the dike reduced current velocity and that the tidal prism decreased by 21% or more in the bay.

A physical model can only be tested under a specific similarity ratio, making it impractical to cover all possible conditions. It is difficult to fit a submerged dike’s height in physical models. With the rapid development of computer modeling, numerical simulation has become an effective research method. Using a two-dimensional numerical model, this paper analyzes hydrodynamic characteristics, including the flow velocity and the cross-dike flux, under different heights and orientations of a submerged dike. It can provide a basis for the study of submerged dike hydrodynamics, submerged dike design, and coastal zone ecological restoration.

2. Materials and Methods

This paper uses MIKE21 FM (MIKE ZeroRelease 2014, Service Pack 3), which is developed by DHI Water & Environment, to simulate numerical models. MIKE21 FM uses a cell-centered finite-volume method to fit complicated terrain well and ensure material flux conservation with high speed. It can forecast water level change and flow under different driving forces by solving continuity and momentum equations to calculate the water level at different times and the velocity of each grid point. Related research [21,22] on submerged dikes has proved the applicability of MIKE.

The research focuses on the large-scale, horizontal redistribution of flow and the calculation of bulk cross-dike flux, for which depth-averaged dynamics are dominant. The use of a 2D model allows for a computationally efficient exploration of the parameter space (dike height and orientation) while isolating their first-order effects from the complexities of three-dimensional turbulence. This approach is well-established for investigating coastline-scale hydrodynamics around submerged structures and provides a critical baseline for understanding primary flow patterns.

2.1. Governing Equations

This paper employs two-dimensional incompressible Reynolds-depth-averaged shallow-water equations. The basic equations in this model are as follows.

Mass conservation equation:

Momentum equation:

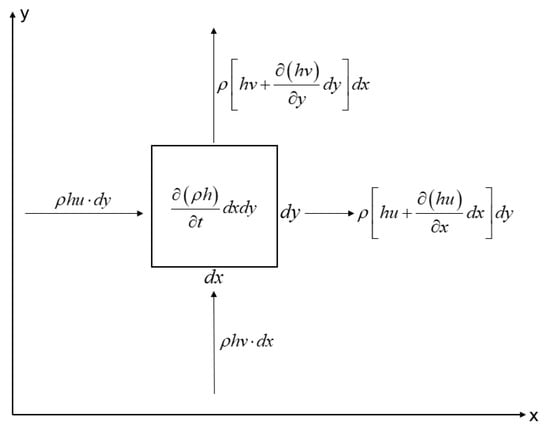

where indicates the surface elevation; indicates the depth of water; indicates the total depth; ; and are velocity components in the and directions; is the gravitational acceleration, = 9.81 m/s2; is the parameter of the Carioles force (, is rotational angular velocity of the earth, is engineering sea latitude); is the Chezy resistance; ; and are horizontal eddy viscosity coefficients of components in the and directions; and indicates time. Figure 1 is a schematic diagram of the mass conservation equation.

Figure 1.

Diagram of mass conservation equation.

The model assumes water is incompressible, which is valid for all practical hydraulic and coastal engineering applications where Mach number Ma << 0.3. The model assumes that the horizontal scales of motion are much greater than the water depth, neglecting vertical acceleration effects.

This 2D approach cannot capture 3D flow structures, particularly strong vertical separation and secondary currents in the dike wake region. The hydrostatic assumption may introduce errors in regions of rapidly varying bathymetry.

2.2. Initial Conditions

2.3. Boundary Conditions

The closed-boundary normal-direction velocity is zero, .

2.4. Open Boundaries

The open-boundary-condition velocity is 1 m/s constantly. The direction of flow is from left to right.

2.5. Other Conditions

The Manning is normally 0.02.

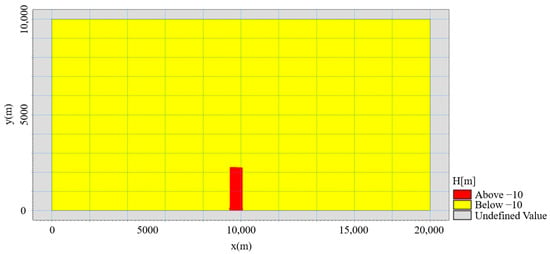

This article employs an idealized case study. To reduce the grid scale effect, the domain is a 20,000 m long and 10,000 m wide rectangular channel with a constant water depth of 10 m. This simulates a large submerged dike about 2500 m long and 700 m wide. The water depth (represented by H) is set as a vertical length unit, and the length of the submerged dike (represented by L) is set as a horizontal length unit.

The model terrain diagram is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Model terrain schematic.

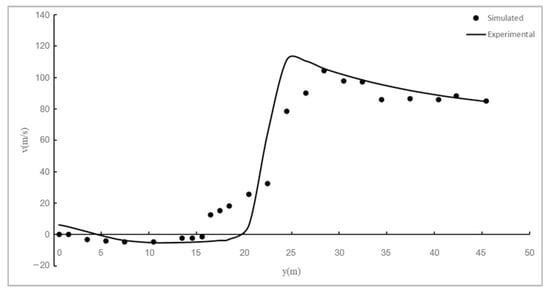

In this paper, the experimental data presented by Iqbal and Tanaka [23] are used to validate the numerical model. At the same time, the error relative to the measured current value is calculated, and the Brier Skill Score (BSS) is 0.91. BSS is an empirical coefficient that relates to the variance between the measured data and the model results. A BSS close to 1 indicates that the simulation performance of the model is good, and a BSS close to 0 indicates that the fitting result is poor, and the model cannot be used for calculation.

where m is the measured value and c is the calculated value of the model.

Although the model does not accurately simulate the variation rule, the overall trend is consistent, and the statistical error analysis results are reasonable (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Comparison between numerical and experimental results.

2.6. Schemes Setup

The numerical modeling conditions were designed to be idealized in order to isolate the fundamental effects of dike height and orientation. A rectangular channel with constant depth and a steady, uniform inflow velocity was employed. This approach eliminates confounding factors from complex bathymetry and unsteady flow, allowing for a clear attribution of the observed hydrodynamic patterns to the dike parameters under investigation. While this setup does not replicate a specific field site, it represents a canonical scenario for studying current–structure interaction, similar to methodologies used in foundational studies.

2.6.1. Schemes of Different Heights

To study the characteristics of a submerged dike in terms of dynamics, this paper sets up 10 groups with different heights. The dike heights are set to 0.1 H, 0.2 H, 0.3 H, 0.4 H, 0.5 H, 0.6 H, 0.7 H, 0.8 H, 0.9 H, and 1 H. The upper and lower boundaries of the model are land boundaries, and the left and right boundaries are water boundaries. The boundary conditions are 1 m/s, and the model maintains a constant flow of 1 m/s.

2.6.2. Schemes of Different Orientations

To study the influence of submerged dike orientation on hydrodynamics, this paper sets up 7 groups of different orientations. The length and width of the submerged embankment are the same as those in the aforementioned plan, and the water depth is also the same. The flow direction, which is from due east to west, is defined as a reference. Then, the submerged dikes’ orientations—the angles between their center lines and the flow direction— are set at 30°, 45°, 60°, 90°, 120°, 135°, and 150°. The boundary conditions of this plan are also consistent with those of the aforementioned plan.

3. Results

3.1. Hydrodynamic Characteristics for Different Submerged Dike Heights

3.1.1. Flow Velocity Distribution for Different Submerged Dike Heights

- Distance–velocity distribution

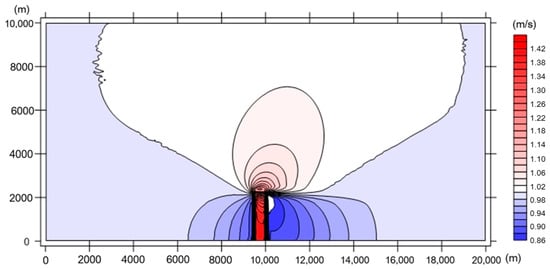

From the flow velocity contour map (Figure 4), it can be seen that the velocity contour map is slightly rounded at the dike head, slightly straight at the tail, and looks quarter-round. With the decrease in the contour value, the contour gathers at the dike head. This indicates that the velocity changes most dramatically near the head of the submerged dike. The velocity at about 0.2 L from the dike head shows the most significant change along the flow direction. Therefore, we analyzed the decay of flow velocity with distance for different submerged dike heights by studying the velocity at a line located about 0.2 L from the dike head, when the orientation angle of submerged dike is 90°.

Figure 4.

Flow velocity contour map (Flow direction: from left to right).

- 2.

- Flow velocity variation with distance for different dike heights

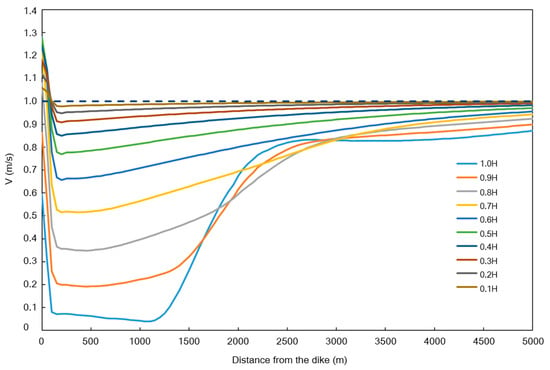

The separate flow zones are different in every case, depending on the height of submerged dike. To reflect the velocity variation with distance for different dike heights, the velocity along the line of 0.2 L distance from the submerged dike was selected to study the velocity law. Figure 5 shows that the flow velocity in general decreases rapidly at a distance of about one-tenth of L. Then, as the distance increases, the flow velocity continues to recover to its original velocity, and finally becomes stabilized. A submerged dike height of 0.7 H is a dividing value. When the submerged dike’s height is shorter than or equal to 0.7 H, flow velocity recovery is substantially proportional to distance. While the distance increases, the flow velocity increases. When the height of the submerged dike is higher than 0.7 H, the velocity is invariant or changes little from a distance of about one-tenth of L to half of L. The velocity quickly recovers at distances further than half of L. In all schemes, the velocity recovers to 85 percent of the initial flow velocity at a distance of one dike length, but the velocity values with different dike heights are slightly different.

Figure 5.

Flow velocity variation with distance for different submerged dike heights.

3.1.2. Flux Characteristics for Different Submerged Dike Heights

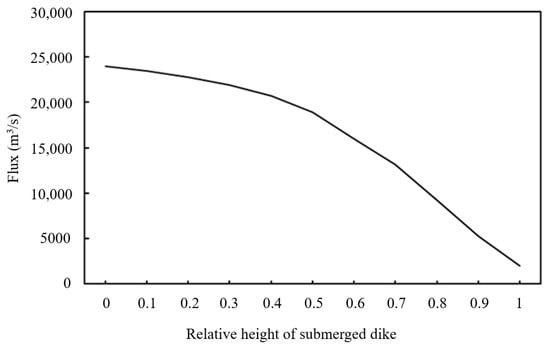

To study the hydrodynamics of submerged dikes with different heights, the average velocity across submerged dikes is reflected by the flux across the center line of the submerged dikes. Figure 6 shows that the flux is reduced as the height of the submerged dike increases. When the relative height of the submerged dike is between 0.5 H and 1 H, the relationship between cross-dike flux and the relative height of the submerged dike is linear. When the relative height is less than 0.5 H, the cross-dike flux decreases slowly.

Figure 6.

Flux across submerged dike of different heights.

3.2. Hydrodynamic Characteristics Under Different Submerged Dike Orientations

3.2.1. Flow Velocity Distribution Under Different Submerged Dike Orientations

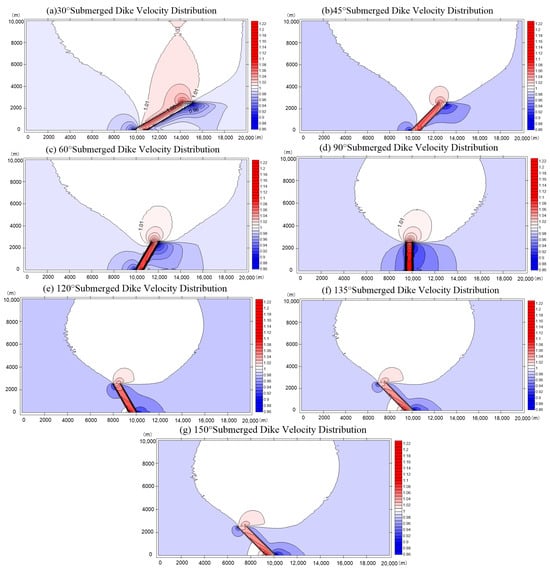

Figure 7 shows that the laws of velocity distribution can be divided into three categories by the angle between the submerged dike and the flow direction. The first category is acute angles. The flow velocity decreases on the backside of the submerged dike and the front side of the dike foot, and increases on the face of the submerged dike and the front of the dike head. As the angle increases, the area of flow velocity decrease becomes larger, and the area of flow velocity increase becomes smaller. The second category is a right angle. In this circumstance, the flow velocity decreases on the backside and front side of the submerged dike, and increases on the face of the submerged dike and the front of the dike head. Thirdly are obtuse angles. In these cases, the flow velocity decreases on the frontier of the submerged dike head and the backside of the submerged dike foot, and increases on the dike, the front of the dike foot, and the backside of the dike head. With an increase in angle, the area of flow velocity decrease becomes smaller. In addition, it is easily discovered that with a decrease in angle, the range and the degree of flow velocity decrease become smaller and lower. This means that submerged dikes with smaller angles have lower influence on flow fields.

Figure 7.

Flow velocity distribution for different submerged dike orientations (flow direction: from left to right).

3.2.2. Flux Characteristics Under Different Submerged Dike Orientations

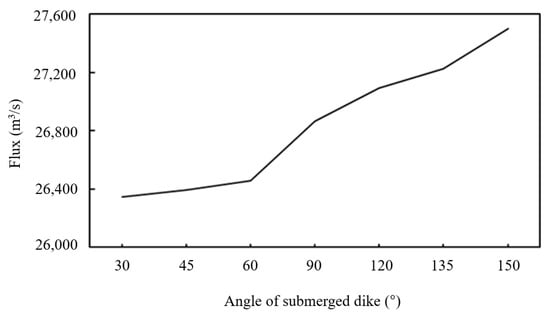

As depicted in Figure 8, the cross-dike flux increases with angle. Because the flow direction follows the submerged dike orientation, the blocking effect of the submerged dike is tiny. In orientations with acute angles, the cross-dike flux changes little. A smooth linear relationship is present when the angle is less than 60°. If the angle is more than 60°, the flux increases sharply with angle.

Figure 8.

Flux under different submerged dike orientations.

4. Discussion

The fundamental ecological premise of this study is that structures which minimize alterations to natural flow patterns generally have lower environmental impacts. Reduced velocity changes and maintained cross-dike flux help preserve natural sediment transport regimes, nutrient distribution, and habitat connectivity—all critical factors for ecosystem health. Macroinvertebrate abundance and diversity both generally declined in response to alteration inflow magnitude, whether an increase or a decline [24].

In general, when a submerged dike is perpendicular to the coastline and the flow direction is parallel to the coastline, owing to the presence of the submerged dike, the flow velocity increases on the dike’s head side and decreases on the dike’s tail side. The velocity at about 0.2 L from the dike head shows the most significant change along the flow direction. The velocity on the dike’s head side increases because the water section along the dike reduces, and the velocity of all the water tries to keep its original state. The velocity on the dike’s tail side decreases because the water along the dike is hindered by the dike. The range of the flow velocity variation is concentrated in the area of 2 L.

4.1. Influence of Submerged Dike Height on Flow Velocity and Flux

The velocity distribution law for different dike heights can be used to adjust the marine hydrodynamic impact. According to the result shown in Figure 4, if the height is below 0.7 H, a location velocity can be predicted by the empirical formula: y = ax + b (a is the slope). Thus, the initial height of the dike can be confirmed from the perspective of the flow velocity. In this paper, the relationship between relative height and slope is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

The relationship of relative height and slope.

When the dike orientation is perpendicular to the coastline, the flux is reduced as the height of the submerged dike increases. The changing of the cross-dike flux of different dike heights can be divided into two types: basically unchanged (dike height < 0.5 H) and linear change (dike height > 0.5 H). It may be the following reasons. When the relative height of the submerged dike is small (less than 0.5 H), as the height of the submerged dike increases, the area of water across the submerged dike is reduced, but the velocity is increased. These two changes cause the flux to decrease slowly. However, when the relative height of the submerged dike is high (greater than 0.5 H), as the height of the submerged dike increases, the area of the water across the submerged dike is reduced. It becomes a decisive factor and causes the cross-dike flux to linearly decrease as the height increases.

To preserve natural flow patterns, considering the effect of the submerged dike height, the submerged dike height should be designed below the critical relative height of 0.7 H. This ensures the flow regime remains in a “low-disturbance” state, which is fundamental for protecting in situ benthic communities and natural sediment dynamics. Considering the influence on cross-dike flux, it is recommended to limit the submerged dike height to below 0.5 H.

4.2. Influence of Submerged Dike Orientation on Flow Velocity and Flux

The laws of velocity distribution can be divided into three categories: the acute angle, the right angle, and the obtuse angle law. For the first category, the submerged dike orientation is nearly the same as the flow direction. The flow velocity on the frontier of the dike head increases because of the dike’s deflecting flow effect. The flow velocity on the submerged dike increases because the area of water across the submerged dike becomes small. The flow velocity on the backside of the submerged dike and the front side of the dike foot decreases because of the blocking effect of the submerged dike. For the second category, the submerged dike is perpendicular to the flow direction. The flow velocity on the backside and front side of the submerged dike decreases because of the blocking effect of the submerged dike. The flow velocity on the submerged dike also increases because the area of water across the submerged dike becomes small. For the third category, the orientation of the submerged dike is opposite to the flow direction, and they are shaped like a horn mouth. The flow is adjusted by the orientation and gathers in front of the dike’s foot. This makes the velocity increase. The flow velocity on the submerged dike increases because the area of water flowing across the submerged dike becomes small. The flow velocity on the backside of the submerged dike decreases because of the blocking effect of the submerged dike.

To achieve an optimal compromise between moderating flow velocity variations and preserving ecological connectivity, the orientation of the submerged dike should be constrained to angles under 60° relative to the primary current direction. If maximizing cross-dike flux is a project objective, an orientation angle greater than 90° is recommended.

5. Conclusions

A numerical model is set up using MIKE 21 FM to analyze the hydrodynamical behaviors of a submerged dike. A series of model tests have been conducted to study the variation characteristics of the flow velocity and the cross-dike flux under certain conditions. The flow patterns are different in each case, depending on the height and orientation of the dike. Therefore, the height and orientation must be considered during the design of a submerged dike. According to our simulated results, the following conclusions can be obtained.

The velocity at a distance of about 0.2 L from the head of the dike shows the most significant change along the flow direction, which is perpendicular to the dike and parallel to the coastline. The range of flow velocity variation is concentrated in the area of 2 L.

In every different height condition, the flow velocity decreases rapidly at a distance of 0.1 L. Then, as distance increases, the flow velocity continues to recover. The relative dike height of 0.7 H marks a clear division beyond which the flow velocity exhibits a distinct decay pattern with distance compared to all other heights.

The cross-dike flux is reduced as the height of the submerged dike increases. When the relative height of the submerged dike varies from 0.5 H to 1 H, the relationship between the flux and the relative height of the submerged dike is linear. When the relative height is less than 0.5 H, the flux across the submerged decreases very slowly.

Under different orientation conditions, the laws of velocity distribution can be divided into three categories by the angle between the dike and the flow direction. And cross-dike flux increases as the angle increases.

For ecological restoration projects that aim to minimize hydrodynamic disturbance, a relative dike height lower than 0.7 H and an orientation angle smaller than 60° are preferable under steady current conditions similar to this study.

While recognizing that real-world submerged structures exhibit complex geometries and porosity, this study intentionally employs a simplified, impermeable, rectangular dike section. This fundamental approach is adopted to isolate the first-order hydrodynamic effects of dike height and orientation, free from the confounding influences of other parameters. Establishing this theoretical baseline is a critical first step in developing a comprehensive understanding. It provides a foundation for the future systematic evaluation of additional complexities, such as slope, porosity, and surface roughness.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and X.Z.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z. and X.L.; validation, Y.D. and X.L.; formal analysis, X.Z.; investigation, X.Z.; resources, Y.Z. and X.Z.; data curation, X.Z., Y.Z., and B.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z. and X.Z.; writing—review and editing, X.Z. and Y.Z.; visualization, Y.D. and X.Z.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Youth Marine Science Fund of East China Sea Bureau, Ministry of Natural Resources, grant number 2023180504.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the study are available. Please contact the corresponding author to obtain them.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Li, G.; Lang, L.; Ning, J. 3D Numerical Simulation of Flow and Local Scour Around a Spur Dike. In Proceedings of the IAHR World Congress, Chengdu, China, 13 September 2013; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.H.; Ding, W. Hydrodynamic improvement of a goose-head pattern braided reach in lower Yangtze River. J. Hydrodyn. 2019, 31, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z. Simulation of scour and deposition in the flow field and adaptability of fishes around eco-friendly notched groins. J. Hydrol. 2022, 609, 127754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weitbrecht, V.; Socolofsky, S.A.; Jirka, G.H.; Asce, F. Experiments on mass exchange between groin fields and main stream in rivers. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2008, 134, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Meer, J.W.; Nieuwenhuis, J.W.; Steendam, G.J.; Reneerkens, M.; Steetzel, H.; van Vledder, G.P. Wave overtopping measurements at a real dike. Coast. Struct. 2019, 2019, 1107–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, T.; Altomare, C.; Yasuda, T.; Verwaest, T. Characterization of overtopping waves on sea dikes with gentle and shallow foreshores. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beji, S.; Battjes, J.A. Numerical simulation of nonlinear wave propagation over a bar. Coast. Eng. 1994, 23, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Tanaka, N. Analysis of hydrodynamic behavior in response to diverse pile arrangements adjacent to an impermeable dike. Water Sci. 2024, 38, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yang, S.; Mao, J.; Gong, Y.; Muhammad, W.I.; Yin, S. Numerical investigation of flow structure and turbulence characteristic around a spur dike using large-eddy simulation. Water 2022, 14, 3158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujantoko, S.; Djatmiko, E.B.; Wardhana, W.; Firmasyah, I.N.G. Numerical Modeling of Hydrodynamic Performance on Porous Slope Type Floating Breakwater. Nase More 2023, 70, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalena, I.; Nathanael, O. Wave resonance reduction over a linear transition bottom with a submerged porous breakwater. Results Eng. 2025, 26, 104580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada, I.J.; Losada, M.A.; Martin, F.L. Experimental study of wave-induced flow in a porous structure. Coast. Eng. 1995, 26, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altomare, C.; Suzuki, T.; Chen, X.; Verwaest, T.; Kortenhaus, A. Wave overtopping of sea dikes with very shallow foreshores. Coast. Eng. 2016, 116, 236–257. [Google Scholar]

- Tsal, C.P.; Chen, H.B.; Jeng, D.S.; Chen, K.H. Wave Transformation and Soil Response due to Submerged Permeable Breakwater. In Proceedings of the OMAE 2006, Hamburg, Germany, 4–9 June 2006; pp. 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifahmandian, A.; Simons, R.R. A 3D numerical model of nearshore wave field behind submerged breakwaters. Coast. Eng. 2014, 83, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, C.B.; Hu, S.X.; Huang, W.W. Numerical study on the characteristics of flow field and wave propagation near submerged breakwater on slope. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2010, 29, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.C.; Hayashi, S.; Yamanishi, H. Effect of the shape of submerged dike/mound on mud transport. Sediment Ecohydraulics INTERCON 2005, 9, 329–544. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Q.X.; Zhang, R.B.; Yang, H. Flume experimental study on the heights of submerged dike to diminish siltation. Ocean Eng. 2012, 30, 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Ge, J.Z.; Ding, P.X.; Fu, G. Numerical simulation about temporal and spatial variations of overtopping flow flux at the south leading jetty in the deep waterway project of the Changjiang Estuary. J. East China Normal Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2016, 2, 50–78. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.B. Research on the Effects of Donghai Dam on the Hydrodynamic Environment of the Zhanjiang Bay. Master’s Thesis, Ocean University of China, Qingdao, China, 2008; pp. 112–127. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, H.K.; Karambas, T.V.; Avgeris IZanuttigh, B.; Gonzalez-Marco, D.; Caceres, I. Modelling of waves and currents around submerged breakwaters. Coast. Eng. 2005, 52, 949–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanuttigh, B.; Lamberti, A. Experimental analysis and numerical simulations of waves and current flow around low-crested rubble-mound structures. J. Waterw. Port Coast. Ocean Eng. 2006, 132, 10–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Tanaka, N. Experimental Study on Flow Characteristics and Energy Reduction Around a Hybrid Dike. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2023, 21, 1045–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poff, N.L.; Zimmerman, J.K.H. Ecological responses to altered flow regimes: A literature review to inform the science and management of environmental flows. Freshw. Biol. 2010, 55, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).