In the original publication [1], there was a mistake in Table 2 as published. Units for the parameters Dissolved Oxygen, Total Phosphorus, Total Nitrogen, Visual Clarity, Dissolved Reactive Phosphorus, Ammoniacal Nitrogen, and Nitrate were incorrectly typed. The corrected Table 2 appears below.

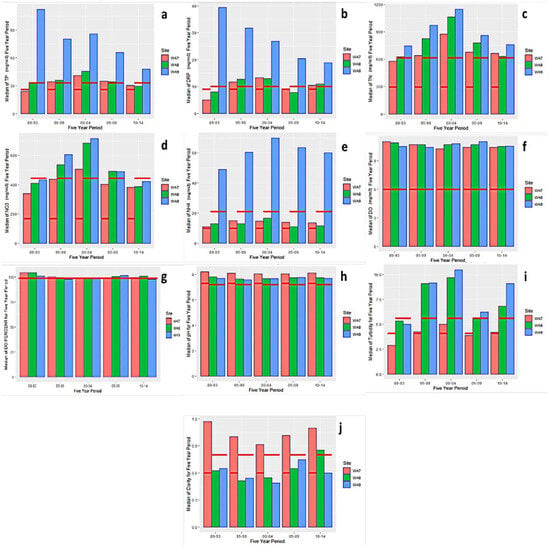

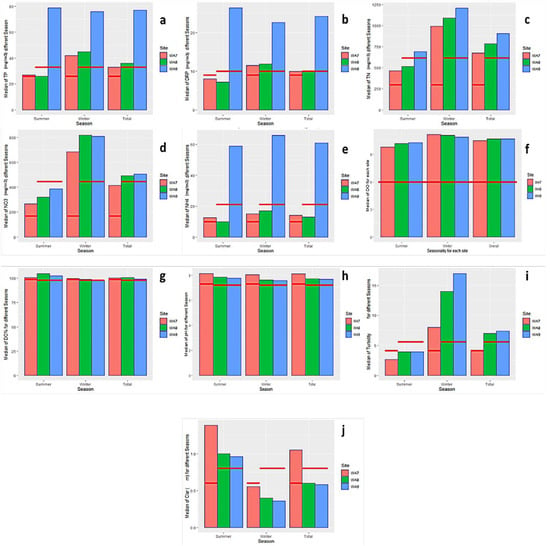

In the original publication, there was a mistake in Figures 4 and 5 as published. The axes in both figures had incorrectly written units. The units corrected include Total Phosphorus, Total Nitrogen, Visual Clarity, Dissolved Reactive Phosphorus, Ammoniacal Nitrogen, Nitrate and Turbidity. The corrected Figure 4 and Figure 5 appear below.

Table 2.

Description of Water Quality Data Used for Analysis of the Manawatu River in NZ from 1989–2014.

Table 2.

Description of Water Quality Data Used for Analysis of the Manawatu River in NZ from 1989–2014.

| Unit | Abbreviation | Missing Data (%) | Trigger Values (Lowland/Upland †) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flow rate | m3/s | Flow | 1.4 | |

| Water Temperature | °C | Tw | 0.3 | |

| Electrical conductivity | µScm−1 | EC | - | |

| Dissolved Oxygen | mg/m3 | DO | 1.3 | 6 |

| Dissolved Oxygen (%) | % | DO% | 1.3 | 98/99 |

| pH | - | pH | 0.2 | 7.2/7.3 |

| Turbidity | NTU | Turb | - | 5.6/4.1 |

| Total Phosphorus | mg/m3 as P | TP | 0.3 | 33/26 |

| Total Nitrogen | mg/m3 as N | TN | 0.6 | 614/295 |

| Visual clarity | m | Clar | - | 0.8/0.6 |

| Dissolved Reactive Phosphorus | mg/m3 as P | DRP | - | 10/9 |

| Ammoniacal nitrogen | mg/m3 as N | NH4-N | - | 21/10 |

| Nitrate | mg/m3 as N | NO3-N | - | 444/167 |

Note: DO % and pH: lower limits were considered. † Lowland and Upland are distinguished by the 150-m elevation threshold.

Figure 4.

(a–j): Water Quality patterns for 25 years, at 5-year intervals, at the three stations. The red lines represent the ANZECC trigger values for the respective WQ variables.

Figure 5.

(a–j): Water Quality patterns for 25 years, at the three stations, in different seasons. The red lines represent the ANZECC trigger values for the respective WQ variables.

There was an error in the original publication [1]. In the published manuscript, the units in the text matched the units listed in Table 2. However, the units of some parameters have been changed. The text is now updated to match the new units in Table 2. A correction has been made to Section 3.3, Paragraphs 1 and 2.

The TP values (Figure 4a) for WA7 recorded an increasing trend for the first 15 years of sampling and a reduction for the last ten years during the monitoring period. However, the values recorded during this period exceeded the trigger values of 33 mg/m3, except for the first and last five years. The lowest median value measured in the first five years of sampling was initially lower than the trigger value, but it later increased between 2000 and 2004. For WA8 (Figure 4a), a similar trend was observed, with a minor difference observed in the first and last five years. The first five years had slightly higher median values than the trigger values, whereas the values during the previous five-year period were lower than the trigger values. This difference may be due to non-point source pollution at WA7 (upland river), which flowed into lowland rivers (WA8 and WA9), as well as the increase in connected pasture areas connected to the floodplain in WA9, compared with WA7. However, this was not the case for WA9. Until 2014, the TP values recorded were higher than the trigger values (Figure 4a). The higher TP values recorded may result from the accumulation of pollutants as they flow downstream. The seasonality comparison for all sites revealed similar trends for WA7 and WA8 (Figure 5a). The TP values in WA7 and WA8 were higher in winter than in summer, whereas the overall median values for both sites were higher than those of the stipulated trigger values. For WA9, which was not the case in summer and winter, the overall median values were higher than the trigger values (Figure 5a).

Throughout the monitoring period, the DRP values were higher than the trigger values for WA9, measuring 9 mg/m3 (Figure 4b). Between 1989 and 1993, and 2005 and 2009, there was a reduction in DRP; their levels were lower than the trigger values in WA7 and WA8. These values increased in 2014 and were higher than trigger values. Seasonality comparisons for all sites showed that seasonal values were higher than trigger values for WA9 (Figure 5b). At the same time, the same was only observed for winter and overall median values in WA7 and WA8. As for TN, all three sites (WA7, WA8, and WA9) (Figure 4c) showed similar distribution patterns to the patterns mentioned above from the beginning. The TN values recorded were above the trigger value of 295 mg/m3 until 2014. Interestingly, these values were significantly higher between 2000 and 2004. Seasonality across sites revealed that the summer, winter, and overall TN values exceeded the trigger values for all sites (Figure 5c). For NO3−, the values recorded throughout all periods were higher than the trigger values for all three sites (Figure 4d). High values above the trigger value of 167 mg/m3 were measured during the winter and summer periods (Figure 5d). For NH4+, all the site concentration values monitored over the 25 year period showed that the trigger values of 10 mg/m3 were exceeded to different extents (Figure 4e). More specifically, the NH4+ values recorded in WA9 were much higher than those at the other sites. Seasonality values also showed similar observations, with winter, summer, and overall median values exceeding the stipulated trigger values (Figure 5e). All sites (WA7, WA8, and WA9) had DO values below the threshold. Throughout all seasons, the data revealed that despite the number of pollutants entering the river, or that were already present in the river, the DO values were significantly above the trigger values of 6 mg/m3 (Figure 4f). The seasonal comparison also corroborates this finding. The functional reaeration capacity of the river allows for more oxygen to be re-introduced when used up, owing to the bathymetry of the river (Figure 5f). Additionally, observation of DO% revealed that all measured values were above the trigger values of 99% for the different sites during all study periods (Figure 4g). The same was observed for the median values, as seasonality was also observed (Figure 5g). The PH values were expected to be above the stipulated trigger value of 7.3. The values recorded during the monitoring periods for the three sites revealed that the median pH values were below the trigger values (Figure 4h). The same was observed during seasonality comparisons, thus corroborating a significant concern regarding high pH values (Figure 5h). For turbidity, WA8 and WA9 (Figure 4i) exhibited similar trends. Initially, the recorded values were below the trigger values, but these values increased over time to be above the trigger value. Nevertheless, in WA7 (Figure 4i), a slightly different pattern was observed. Slightly elevated values were recently recorded, whereas elevated values were measured between 1994 and 1999, and 2000 and 2004, with the highest value recorded between 2000 and 2004. Seasonality analysis revealed that the overall median and winter turbidity values exceeded the trigger values (Figure 5i). WA7 had good overall water clarity compared with WA8 and WA9 (Figure 4j). The water clarity values measured in WA7 exceeded the expectations of trigger values, whereas WA8 and WA9 had poor water clarity and did not meet expectations, except for the values measured in WA8 between 2010 and 2014. The seasonality comparison showed that most of the exceeded values were measured during the summer (Figure 5j), whereas the winter period had poor water quality for all three sites.

The authors state that the scientific conclusions are unaffected. This correction was approved by the Academic Editor. The original publication has also been updated.

Reference

- Tenebe, I.T.; Julian, J.P.; Emenike, P.C.; Dede-Bamfo, N.; Maxwell, O.; Sanni, S.E.; Babatunde, E.O.; Alves, D.D. Multi-Dimensional Surface Water Quality Analyses in the Manawatu River Catchment, New Zealand. Water 2023, 15, 2939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).