Abstract

This study addresses the problem of inaccurate channel flow simulation and uneven irrigation water distribution caused by the spatiotemporal variability of Manning’s roughness coefficient. The SCE-UA optimization algorithm was applied to calibrate Manning’s roughness coefficients and quantify their spatiotemporal variation patterns using 1728 sets of measured water level–discharge data collected in the Yellow River Irrigation District. Results show that accounting for spatiotemporal variability reduces the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) for water level simulation by nearly 8%. Based on these findings, an automatic roughness update system specifically designed for grassroots water distribution stations has been developed, which can integrate water demand and gate control to achieve efficient water allocation in canals in the future.

1. Introduction

Manning’s roughness coefficient is a fundamental parameter in fluid mechanics, characterizing the comprehensive resistance opposing the flow direction. Its value directly affects the calculation accuracy of flow velocity and discharge, and also serves as a critical factor in estimating energy loss caused by friction during water propagation [1,2]. In irrigation districts, Manning’s roughness coefficient finds extensive applications. In surface irrigation systems, this parameter is a core variable for designing and evaluating irrigation performance, with its variation patterns attracting significant research attention to improve irrigation efficiency [3,4,5]. For canal hydraulic design, the selection of Manning’s roughness coefficient determines the channel’s flow capacity, structural safety, and the simulation accuracy of hydrodynamic processes during irrigation scheduling, thereby influencing both irrigation efficiency and water allocation equity [6,7]. In flood control districts, Manning’s roughness coefficient is pivotal for deriving peak flood discharge, critically impacting flood forecasting, levee design elevation determination, and numerical simulations of inundation ranges [8,9,10]. However, field observations reveal that Manning’s roughness coefficient in canals is not constant but exhibits pronounced spatiotemporal variability due to seasonal operations, sediment deposition, and vegetation growth [11].

Furthermore, empirical reference ranges exist for Manning’s roughness coefficients of different materials. However, values derived only from surface roughness are often inaccurate [12,13]. Accurate unsteady flow simulation requires suitably calibrated channel parameters, especially Manning’s roughness [14]. A common approach involves minimizing the error between measured and simulated water levels as the objective function, treating Manning’s roughness coefficient as the decision variable, and solving for its optimal value using optimization algorithms [15,16]. As research progresses, a single Manning’s roughness coefficient can no longer meet the accuracy requirements of complex hydraulic modeling. Scholars have increasingly recognized the spatiotemporal variability of this parameter and have conducted a series of related studies [17,18]. Some researchers have used Monte Carlo simulations and proposed spatial distribution functions that are based on heuristic search and optimization clustering algorithms to identify roughness in natural rivers [19,20]. Others have developed neural network-based roughness identification models, enabling dynamic determination of Manning’s coefficients for any channel section at any time [21,22]. Additionally, adaptive models have been introduced to automatically adjust roughness based on water level and discharge [23,24]. Although these models are powerful, their implementation process is overly complex. They place high demands on users’ professional expertise and computational resources, making it difficult to promote their application at the grassroots level in irrigation districts [25,26]. Therefore, in practical applications, suitable Manning’s roughness identification models should be selected based on specific modeling objectives and data conditions, ensuring simulation accuracy while balancing computational efficiency, and fully considering the technical proficiency and hardware configuration of grassroots personnel.

Field investigations in the Yellow River Irrigation District have revealed significant differences in sediment deposition and scouring conditions across different irrigation seasons and canal segments. Particularly on the inner side of curved channel sections, substantial silt accumulation is frequently observed. These factors markedly alter the Manning’s roughness coefficient of the channels. However, when formulating irrigation schedules, most irrigation stations still rely on past experience. They apply a uniform Manning’s roughness coefficient for the entire canal network in flow process calculations, neglecting its spatiotemporal variability. This leads to insufficient simulation accuracy, which in turn causes issues such as uneven irrigation water distribution, under-irrigation, or severe water waste. Addressing the above issues, this study aims to develop an automated channel Manning’s roughness coefficient identification system tailored for practical management in grassroots irrigation districts, proposing a lightweight solution that balances managerial practicality with technical feasibility. Its core value lies in achieving an optimal balance among managerial practicality, technical feasibility, and automation level.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

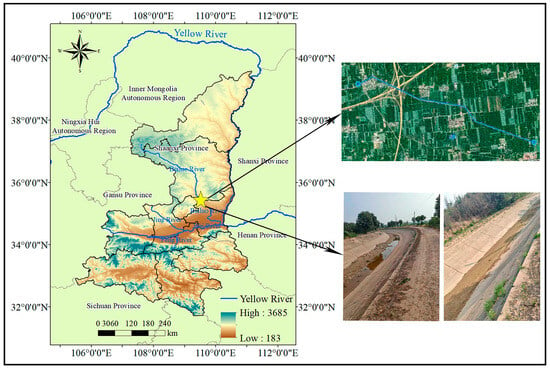

The Weinan Donglei Second Yellow River Irrigation District is located in the Weibei Plateau region of eastern Guanzhong, Shaanxi Province, between 108°50′–110°38′ E longitude and 34°13′–35°52′ N latitude. Sourced from the Yellow River, it has a designed irrigation area of 1.265 million mu (approximately 84,333 hectares) and an effective irrigation area of 0.837 million mu (approximately 55,800 hectares). With a water diversion capacity of 40 m3/s, it serves as a vital production base for grain, fruits, vegetables, and aquaculture in Shaanxi Province. As shown in Figure 1, which illustrates the location of the irrigation district and field photographs of the channels, the total length from the Xingjia Flow Division Gate to the water level measurement point at Puda Road is 5300 m.

Figure 1.

Study Area and Field Photographs.

2.2. Methodology

Water depth and flow data were collected from the Xingjia Gate and Puda Road remote water level monitoring points, with automatic measuring equipment recording every 5 min, totaling 1728 sets. Among these, 14 and 15 August 2024, and 6 and 7 March 2025, served as the calibration sets for the summer and spring irrigation periods, respectively, while August 16 and March 4 were designated as the validation sets.

The hydraulic model employs the Saint-Venant equations (Equation (1)), with computations executed via the Preissmann four-point implicit finite difference method (Equation (2)).

where Bw = average water surface width (m); Z = water level (m); Q = discharge (m3/s); A = cross-sectional flow area (m2); g = gravitational acceleration (m/s2); R = hydraulic radius (m); t = time (s); and x = distance (m).

The discretization scheme is set as θ = 0.55.

Based on Equation (2), the system is discretized and rearranged into a form analogous to Equation (3). The equation was resolved by writing a MATLAB R2020b program.

where f(M) = illustrative variable; and aij,bij = coefficients of the discrete system of equations.

The channel has a base width of 4 m, a side slope ratio of 1.5, and a bed slope of 3/10,000. Water level data for both upstream and downstream sections are obtained from telemetry stations deployed along the channel (measuring water depth with relative elevation). Upstream flow data are derived from daily irrigation settlement records provided by the water distribution station for the downstream section of Xingjia Sluice.

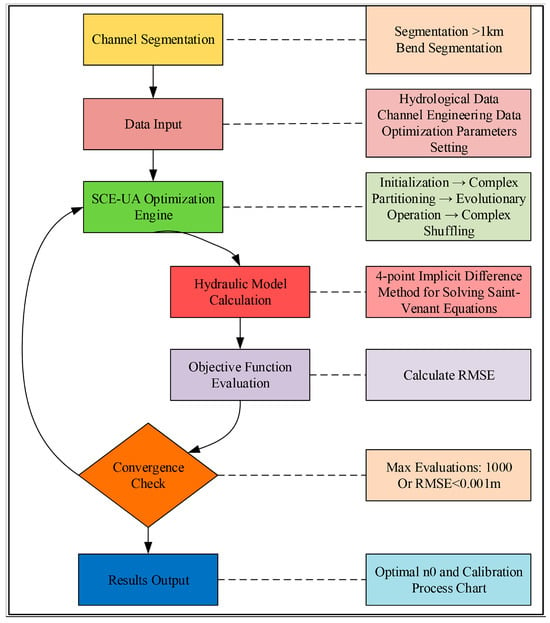

The parameter optimization employs the SCE-UA algorithm. This algorithm is widely used in the optimization of hydrological model parameters [27,28,29] and performs exceptionally well for complex problems characterized by high dimensionality, nonlinearity, and non-convexity. The optimization flowchart is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of SCE-UA-based calibration for channel roughness.

2.3. Calibration Implementation Steps

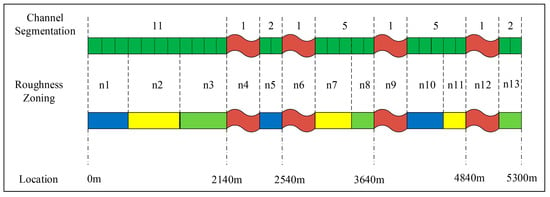

Step 1: Channel Segmentation. During the channel segmentation process, straight sections are first divided into segments with a maximum length of 300 m. This 300 m limit is determined based on the 5 min (300 s) data acquisition interval of the channel’s automated measurement equipment. The four-point implicit finite difference method adopted in this study features an unconditionally stable numerical structure and imposes no strict requirements on grid size. However, an excessive discrepancy between the spatial grid scale and the temporal step size may lead to a reduction in spatial discretization accuracy. For curved sections, the segment length is set to 120 m: in accordance with the requirements of the national standard Specifications for Water Measurement of Irrigation Canal System (GB/T 21303-2017) [30], measurement points at locations with water level fluctuations should be arranged 5 to 10 times the channel width away from the fluctuation points. During the trials, the observed water depth was generally less than 2.5 m, corresponding to a water surface width of 11.5 m. Five times this width equals 57.5 m, so the length of the single-side control segment is rounded up to 60 m, resulting in a total regulated reach length of 120 m for both the upstream and downstream sections. In addition, cross-sections must be installed at locations with irrigation water demand (e.g., lateral intake structures) to ensure the accuracy of water level calculations prior to water abstraction. The segmentation is illustrated in Figure 3, where the 5300 m channel is divided into 29 segments, with 13 Manning’s roughness coefficients to be calibrated.

Figure 3.

Channel Segmentation Schematic Diagram.

Step 2: Data Input. This dataset is primarily used for solving the Saint-Venant equations and calculating the objective function, requiring a complete set of upstream and downstream hydrographs along with channel engineering data.

Step 3: The SCE-UA algorithm serves as the core optimizer for the calibration process. The parameterization is designed to balance computational efficiency with robust exploration of the parameter space, a design validated through historical data tests. The maximum number of function evaluations and iterations is set to 1000 and 20, respectively, and the convergence criterion is defined by a parameter change threshold of 0.1%. This combination ensures that a calibration run is completed within two hours, meeting lightweight requirements without compromising accuracy. Thirty complexes are employed to enhance global exploration capability in the 13-dimensional parameter space. Preliminary tests confirm that when the number of complexes is ≥2N + 1 (where N = 13), premature convergence can be effectively avoided while maintaining computational efficiency. A fixed random seed (=1) is adopted to ensure result reproducibility. This configuration builds upon the classical SCE-UA framework [31].

Step 4: Convergence Criterion. The iterative process terminates if the objective function value (RMSE) is less than 0.01 m or if the maximum number of iterations (1000) is reached, at which point the results are output. Otherwise, the process returns to Step 3.

2.4. Hydrologic Simulation Performance Metrics

MAPE: Mean Absolute Percentage Error. Measures the average deviation percentage of simulated values relative to observed values. Evaluation criterion: Provides an intuitive error concept (e.g., “water depth error percentage”), with values closer to 0 indicating better performance.

RMSE: Root Mean Square Error (units: m). Represents the root mean square of errors between simulated and observed values. Evaluation criterion: Emphasizes penalty for large errors. Values closer to 0 reflect higher model simulation accuracy.

NSE: Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency coefficient. Evaluates model superiority over “using only the mean value for prediction”. Evaluation criterion: Values closer to 1 indicate stronger model capability in capturing dynamic processes (e.g., flow fluctuations).

R2: Coefficient of determination. Measures the strength of linear correlation between simulated and observed values, characterizing trend synchronization. Evaluation criterion: Values closer to 1 are preferable.

PBIAS: Percentage Bias. The core concept of PBIAS is to measure the average deviation of simulated values relative to observed values. Evaluation criterion: Values closer to 0 are preferable.

In Equations (4)–(7): n = Number of samples; H = Measured water depth (m); Hsim = Simulated water depth (m); and = Average water depth (m).

μ*: Mean of Absolute Elementary Effects. It is calculated by taking the arithmetic average of the absolute values of the parameter’s Elementary Effects (EEs). It acts as an indicator that eliminates the interference of the parameter’s influence direction (positive/negative) and quantifies the average impact intensity of the parameter on the model output. A larger value indicates a stronger overall interference of the parameter on the model output across the entire parameter space

σ: Standard Deviation of Elementary Effects. It is calculated as the standard deviation of all Elementary Effects of the parameter, serving as an indicator reflecting the dispersion degree of the parameter’s Elementary Effects in the parameter space. If σ is close to 0, the parameter’s influence is approximately linear, and its interaction with other parameters is weak.

μ: Mean of Elementary Effects. It is obtained by taking the arithmetic average of all Elementary Effects of the parameter, acting as an indicator reflecting the average influence direction (positive/negative) and average effect magnitude of the parameter on the model output. A positive value indicates a positive correlation, while a negative value indicates a negative correlation.

In Equations (9)–(12): k = Number of sampling groups in the parameter space; m = Number of parameter perturbation times in a single sampling group; EEi,j = Elementary Effect value corresponding to the i perturbation in the j sampling group; f(x) = Model output function; Xi = Initial parameter vector of the i sampling group; Δ = Parameter perturbation step size; ej = Unit vector; and = Overall mean of all Elementary Effects.

3. Results

3.1. Calibration Results

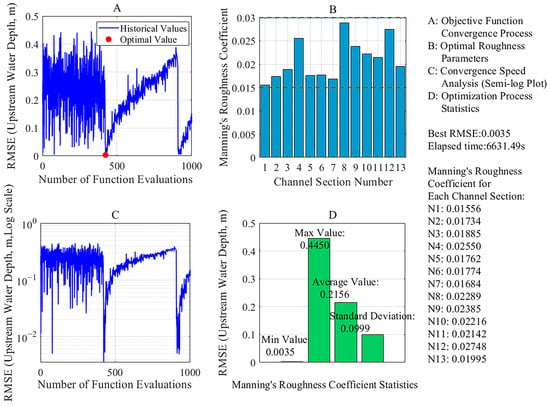

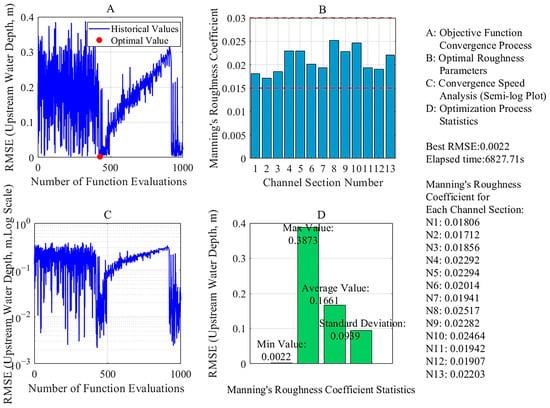

Figure 4 and Figure 5 illustrate the calibration process and results of Manning’s roughness coefficient.

Figure 4.

Calibration Process and Results of Manning’s Roughness Coefficient for March 2025.

Figure 5.

Calibration Process and Results of Manning’s Roughness Coefficient for August 2024.

Manning’s roughness coefficient exhibits significant inter-seasonal variations in spatial distribution. Its values vary markedly across spatial locations during irrigation seasons. Specifically, Manning’s roughness coefficient of the 12th segment (N12) in March 2025 is 0.01907. This is 0.008 lower than the N12 value in August 2024 (0.02748). The relative difference is 30.6%, calculated relative to the August N12 baseline (0.02748). These findings confirm the spatiotemporal variability of Manning’s roughness coefficient, which may impact the accuracy of hydrodynamic simulations in channel systems. The magnitude of such impacts requires further quantification through cross-validation and parameter sensitivity analysis.

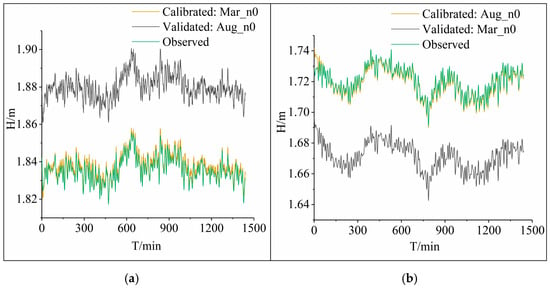

3.2. Validation

Figure 6 illustrates the cross-seasonal water depth simulation results under two scenarios: (a) using the Manning’s roughness parameters calibrated from March 2025 (Mar_n0) and August 2024 (Aug_n0) to fit the water depth data of the same irrigation season as Mar_n0; (b) using the parameters Mar_n0 (calibrated with the March 2025 dataset) and Aug_n0 (calibrated with the August 2024 dataset) to fit the water depth data of the same irrigation season as Aug_n0. The calibrated roughness parameter sets in Figure 6 perform well when simulating the same irrigation season, demonstrating the model’s certain robustness under consistent seasonal conditions. However, their simulation accuracy declines significantly when applied to different irrigation seasons. These results indicate that the spatiotemporal variation in Manning’s roughness coefficient cannot be ignored in irrigation district hydrodynamic modeling.

Figure 6.

Comparison of Cross-Seasonal Water Depth Simulations. (a) Using the Manning’s roughness calibrated in March 2025 (Mar_n0) and August 2024 (Aug_n0) to fit the water depth data of the same irrigation season as Mar_n0; (b) Using Mar_n0 (calibrated with the March 2025 dataset) and Aug_n0 (calibrated with the August 2024 dataset) to fit the water depth data of the same irrigation season as Aug_n0.

Table 1 presents the cross-validation results of water level simulations using two Manning’s roughness coefficients: Mar_n0 (calibrated with the March 2025 dataset) and Aug_n0 (calibrated with the August 2024 dataset). Validation was conducted in two scenarios: within-season validation (using datasets from the same irrigation season as the calibrated coefficient) and cross-season validation (applying a coefficient calibrated in one season to simulate the other season).

Table 1.

Cross-Validation Analysis.

For within-season validation, both calibrated coefficients demonstrated excellent accuracy, with all evaluation metrics meeting the preset performance standards (RMSE < 0.01 m, MAPE < 0.500, PBIAS < 0.100%, R2 > 0.990, NSE > 0.9). Mar_n0 was validated with the March 2025 validation dataset, and the NSE value was 0.5156. This value is slightly lower than the preset threshold but still within an acceptable range, indicating the method’s robustness in short-term simulations. Similarly, Aug_n0 maintained high reliability in within-season validation, with RMSE < 0.01 m and NSE > 0.98.

In contrast, cross-season validation results showed a significant deterioration in simulation performance. When Mar_n0 was applied to the August 2024 dataset, RMSE increased to 0.0491 m (nearly 14 times higher than within-season values), MAPE reached 2.7384 (exceeding the preset limit by over 5 times), and NSE plummeted to −31.94. Similarly, Aug_n0 used for simulating the March 2025 dataset yielded an RMSE of 0.0454 m, a MAPE of 2.3713, and an NSE of −51.16. The negative NSE values (below −30) further indicate that cross-season simulation performance deteriorated significantly, as the model’s accuracy was lower than that of a baseline model using the mean value for prediction.

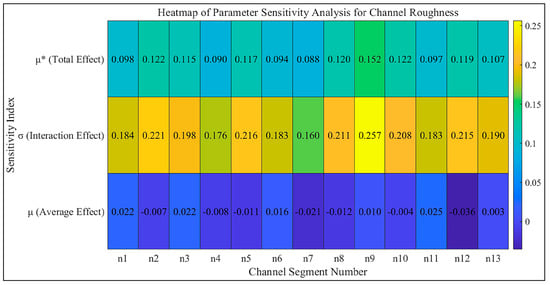

3.3. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

This study employs a segmented discretization approach to characterize Manning’s roughness coefficients of channels through regionalization. It constructs a multidimensional parameter system to accurately describe the comprehensive impact of their spatial variability on the flow propagation process. Based on the deconstruction principles of mathematical models in global sensitivity analysis, the response mechanisms of model outputs under the coupled effects of multiple parameters can be systematically analyzed. This enables the effective identification of core sensitive parameter clusters [32,33,34,35]. Compared with traditional local sensitivity analysis methods, the Morris screening method is a typical global sensitivity analysis tool. It generates a total of 1400 sets of n0 parameter matrices within the reasonable value range of 0.015 to 0.03 (Figure 7). This approach not only quantifies the main effects of individual parameters but also accurately captures the nonlinear interactions among parameters. Such a modeling strategy significantly strengthens the physical constraints of the automatic inversion system for Manning’s coefficients. It ensures that the final parameter calibration results not only meet numerical stability requirements but also strictly conform to hydraulic constitutive relationships. This enhances the interpretability of the results in both river dynamics theory and engineering practice.

Figure 7.

Heatmap of Parameter Sensitivity.

The parameter sensitivity analysis results show that the μ* values corresponding to the roughness coefficients of each channel segment fluctuate around 0.1. This indicates that most channel segments have a relatively similar impact on model outputs, with an overall uniform distribution of sensitivity. Furthermore, the σ values of the parameters are mostly concentrated around 0.2, reflecting the presence of certain nonlinear effects and parameter interactions in the model response. Combined with the small variation range of the μ values, it can be concluded that such interactions are not strong overall, and the parameters exhibit a certain degree of independence. Unlike μ* and σ, the distribution of μ values shows noticeable differences: they vary within both positive and negative ranges, with a range ratio as high as 5.40. This phenomenon can be interpreted from two aspects. First, the sign of the μ value reflects the direction of the parameter’s influence on the model output. For example, both the μ* and μ of the roughness of the first segment are positive, indicating that increasing the roughness of this segment helps improve the simulation performance. Second, the large fluctuation range of the μ values reveals significant differences in the degree of influence of the roughness of different channel segments on the model output. Overall, σ is much larger than μ* (with a ratio of approximately 1.8–2.0). This indicates that the model response is dominated by nonlinear effects and exhibits strong nonlinear characteristics, which aligns with the nonlinear relationship between roughness and water depth in Manning’s formula. At the same time, the high consistency in the ranking of μ* and σ further suggests that the coupling effects between parameters are limited and parameter independence is relatively good. This is beneficial for parameter identification and model calibration.

3.4. Practicality Assessment

To evaluate the model’s practical applicability in irrigation district management, this study simulated the channel flow process using three types of Manning’s roughness coefficients. The three coefficients include the segmented parameter set (Mar_n0) from the March calibration dataset, the reference value for concrete channels (0.015), and the average value (0.021) of calibrated roughness coefficients (Mar_n0) from each channel segment. Their simulation errors were compared, and the results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Simulation Results with Different Manning’s Roughness Coefficients.

As shown in the table results, different Manning’s roughness coefficients significantly impact simulation outcomes. The simulation performance of the segmented calibration method is notably better across three key metrics (MAPE, RMSE, PBIAS) compared to using a single roughness value. Specifically, the water level error (MAPE) under segmented calibration is nearly 8% lower than that of a single roughness value. The RMSE is also reduced by more than 0.1 m. Further analysis of PBIAS trends reveals that a roughness value of 0.015 yields a PBIAS of 4.6402%. This indicates simulated values are systematically lower than measured values. It implies the selected roughness is too small, which leads to overestimated flow velocity and underestimated water level. Conversely, a roughness of 0.021 results in a PBIAS of −4.9677%. This shows simulated values exceed measured values. It means the roughness setting is too large, which causes underestimated flow velocity and overestimated water level. These results fully demonstrate that an appropriate roughness value is crucial for accurate channel water level simulation. When formulating irrigation schedules and conducting hydraulic calculations, it is essential to account for the spatial variability of channel roughness and ensure its proper determination. This enhances the reliability and practicality of simulation results.

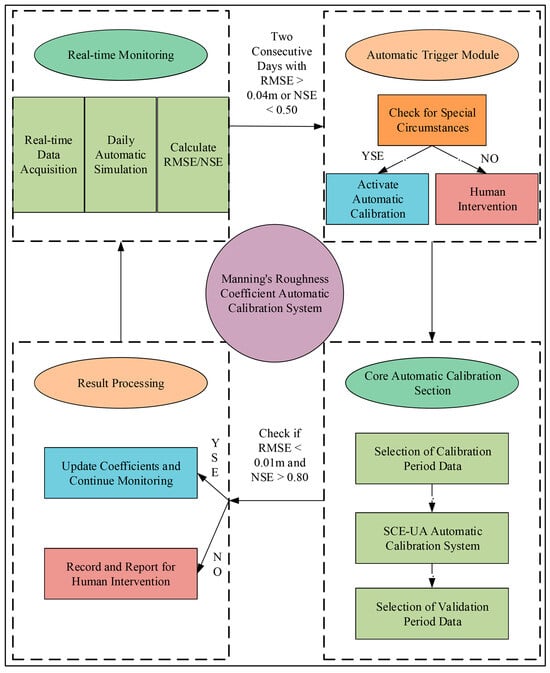

3.5. Automatic Calibration System for Manning’s Roughness Coefficient

Building upon the SCE-UA-based calibration of channel Manning’s roughness coefficient described in the previous section, an automatic calibration system for Manning’s roughness coefficient has been established. The workflow of the system is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Flowchart of the Automatic Calibration System.

This system incorporates a dual-parameter simultaneous triggering calibration mechanism. It imposes strict requirements for the concurrent attainment of calibration criteria for both parameters, ensuring reliability through this dual safeguard. The system also retains a manual intervention safety mechanism. This mechanism prevents calibration errors under special circumstances, such as extreme weather events. With a rapid response mechanism requiring only “2 + 1” days (two days for calibration and one for validation), the system guarantees high efficiency. Furthermore, it forms a closed-loop control system that follows the sequence of monitoring, triggering, calibration, validation, and updating. To verify the practicality of the system, data from two irrigation seasons were shuffled and spliced. The spliced dataset, consisting of March data followed by August data, was used to demonstrate a complete cycle of automatic calibration and updating. Model performance was evaluated using the Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) coefficient and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) as key metrics. Following recommendations from the Handbook of Hydrological Model Evaluation by the International Association of Hydrological Sciences (IAHS), model performance was classified into two grades. The first is usable, applying when 0.5 < NSE ≤ 0.8 and suitable for general hydrological simulation and research; the second is high quality, applying when NSE > 0.8 and applicable to critical decision-support systems such as water resources planning, flood early warning and international cooperation projects. A threshold of 0.04 m was adopted for RMSE, as the water gauge scale of the irrigation district’s channels is 0.02 m per division, and natural fluctuations of the water flow typically do not exceed two divisions.

Real-time Monitoring: The system continuously simulates water levels and discharges over a 3-day period while calculating and plotting the corresponding Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Nash–Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE) indices, as illustrated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Real-time Monitoring Summary.

Triggering Module: Staff import the previous day’s water level and discharge data into the calculation Excel file and run the program to initiate simulation. The simulation results for the first day (based on March 2025 data) are normal. Continuous daily monitoring follows. If the NSEs and RMSEs for two consecutive days (based on August 2024 data) both exceed the warning thresholds (NSE < 0.50, RMSE > 0.04 m) and no special circumstances are confirmed after manual review, the calibration module is activated.

Core Calibration Module: Two consecutive days of measured data that exceed the warning thresholds are selected as the new dedicated calibration dataset. These data are imported into the dedicated calibration Excel file, and the SCE-UA calibration system is initiated to calibrate new Manning’s roughness parameters (for specific implementation, refer to Section 2.3). The calibrated results are then validated using the water level and discharge data from the following day.

Result Processing Module: If the validation results meet the criteria (RMSE < 0.01 m, NSE > 0.80), the Manning’s roughness coefficient is updated, and the calibration process is documented. Upon completion, the system returns to the real-time monitoring module and resumes continuous monitoring.

4. Discussion

After years of informatization construction in irrigation districts, numerous intelligent irrigation district decision-making systems have emerged in China [35,36,37]. However, field investigations conducted in this study reveal that these systems have encountered a promotion paradox of “high performance yet low applicability” when transitioning from “demonstration highlights” to “large-scale practical application”. This is not a single technical issue but a systemic mismatch between “technological supply” and “grassroots demand”, manifested in three specific contradictions. First is the disconnection between demonstration-oriented development and practical needs. Advanced monitoring equipment is mostly concentrated in easily accessible areas such as the head and tail sections of main canals and around management stations, forming a “model section” effect. Branch canals and lower-level watercourses lack automatic metering devices, preventing the systems from supporting full-process precise management. This construction model of “highlighted demonstrations at the top but deficiencies at the grassroots” results in decision-making schemes output by the systems being difficult to implement at the field management unit level, ultimately reducing them to decorative tools that “look good on paper but are impractical in use”. Second is the barrier between fragmented equipment and data integration. The absence of industry standards has led to inconsistent data interfaces among information devices from different batches, making it difficult to integrate and utilize massive amounts of monitoring data. This not only wastes hardware investment but also hinders the systems from forming comprehensive decision-making bases for irrigation, trapping them in a dilemma where “more data leads to more difficult decision-making.” Third is the conflict between technical complexity and grassroots applicability. Traditional intelligent irrigation district systems pursue large and comprehensive integrated models, incorporating real-time data assimilation and imposing high requirements on hardware configurations. Their operation sometimes requires the collaboration of interdisciplinary professionals in agricultural water and soil engineering, computer science, and communication engineering. Most staff at grassroots irrigation district management stations have backgrounds in hydraulic engineering technology, and their capabilities in parameter debugging and troubleshooting of complex models are limited.

To address the long-standing issues in the informatization construction of irrigation districts mentioned above, we propose a lightweight transformation based on the core principle of “people-centered development”. Its value lies not only in methodological innovation but also in the profound response to and reconstruction of the reality of grassroots irrigation management. Specifically, we abandon the computationally intensive real-time data assimilation strategy and instead adopt a computational framework featuring daily-cycle calibration and demand-based division. We do not overly pursue the “comprehensiveness” of the model nor prioritize precision in academic research. Instead, this study shifts to seeking “sufficiently good and applicable” contextual robust solutions for specific irrigation decision-making under limited conditions. This marks a fundamental shift in the core logic of system design: from pursuing perfect performance in ideal environments to ensuring the reliable delivery of core functions in real, resource-constrained grassroots settings. The fundamental purpose of this transformation is to reconstruct the power and capability relationship between technology and users. Traditional complex systems embody a coercive logic that “requires users to adapt to technology,” concentrating decision-making authority in the system model while shifting operational burdens to grassroots administrators. In contrast, our lightweight system is committed to “making technology serve users”, returning control and understanding to the grassroots by lowering technical thresholds. This reconstruction of relationships has greatly unleashed the enthusiasm of grassroots managers, transforming them from passive system operators into active intelligent irrigation managers. From a broader systemic perspective, this “simplification from complexity” innovation achieves in-depth integration of technological innovation and management optimization. It does not merely provide a new tool; rather, by enhancing grassroots acceptance and application capabilities of intelligent technologies, it systematically cultivates the social foundation for technology to “take root” at the grassroots level. The “lightweight” feature of the technology serves as a catalyst for strengthening organizational capabilities. This bottom-up, progressive promotion path starts from irrigation station-level applications and gradually expands to the entire canal system, successfully circumventing the implementation challenges often faced by traditional top-down designed projects. Furthermore, this transformation enables the model to continuously collect grassroots feedback in practice, thereby iteratively optimizing system functions to make them more user-friendly and practical over time.

In terms of data acquisition, we clearly recognize that the current system still faces applicability challenges in irrigation districts with severely lacking monitoring facilities. Although AMR (Adaptive Mesh Refinement) technology can mitigate accuracy losses caused by sparse data from a numerical method perspective [38,39], this technical path also increases requirements for professional computational knowledge and hardware resources, which conflicts to a certain extent with the lightweight goal pursued by this study. Therefore, how to maintain the system’s usability and economy while ensuring accuracy requires further exploration of more reasonable data compensation mechanisms. On the other hand, the seepage effect commonly existing in unlined canals and severely structurally damaged canals is an unavoidable interference factor. Seepage and canal roughness jointly affect flow characteristics [40,41]. Ignoring their coupled impact during calibration may lead to a “compensation effect” between parameters. That is, incorrectly offsetting hydraulic deviations caused by seepage by adjusting Manning’s coefficient, which results in calibration results deviating from physical reality. To systematically evaluate this impact, typical damaged canal cases will be selected in subsequent studies to conduct global sensitivity analysis on Manning’s roughness coefficient and seepage parameters, with the interaction intensity visualized through heatmaps. This method not only reveals the influence mechanism of parameter coupling on model outputs but also quantitatively assesses the system’s robustness under non-ideal conditions, providing a theoretical basis for constructing more reliable calibration models.

5. Conclusions

This study confirms that the channel roughness coefficient exhibits spatiotemporal variability across different irrigation periods (spring irrigation and autumn irrigation) in the Yellow River Diversion Irrigation Districts. Based on the inversion and calibration results of measured water levels using the SCE-UA algorithm, the study systematically quantifies the spatial and temporal variation characteristics of channel roughness and establishes a channel hydraulic simulation system with an automatic roughness update function. Compared with the direct use of the concrete reference value (n0 = 0.015), this approach reduces the RMSE by 0.1455 m. In terms of achievement promotion, the current method still faces two challenges. First, its adaptability to soil channels with severe seepage or structurally damaged channel sections remains unclear. Second, the stability and applicability of the system need further verification under conditions lacking automated monitoring facilities. Future research will focus on exploring the integration of meteorological factors such as rainfall and evaporation into the existing modeling framework. This will enable the development of a more environmentally responsive system for channel roughness inversion and flow simulation, thereby enhancing the model’s dynamic adaptability and predictive performance in the context of climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.L. and D.B.; methodology, L.L. and X.B.; investigation, L.L. and W.Z.; data curation, L.L. and W.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, L.L.; writing—review and editing, L.L. and X.B.; funding acquisition, D.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work were supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41571222, 51909208).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ayvaz, M.T. A linked simulation–optimization model for simultaneously estimating the Manning’s surface roughness values and their parameter structures in shallow water flows. J. Hydrol. 2013, 500, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, T.; Graham, L.; Estep, D.; Dawson, C.; Westerink, J.J. Definition and solution of a stochastic inverse problem for the Manning’s n parameter field in hydrodynamic models. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 78, 60–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moravejalahkami, B.; Mostafazadeh-Fard, B.; Heidarpour, M.; Abbasi, F. Furrow infiltration and roughness prediction for different furrow inflow hydrographs using a zero-inertia model with a multilevel calibration approach. Biosyst. Eng. 2009, 103, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazarei, R.; Mohammadi, A.S.; Ebrahimian, H.; Naseri, A.A. Temporal variability of infiltration and roughness coefficients and furrow irrigation performance under different inflow rates. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 245, 106465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandôme, P.; Belaud, G.; Berkaoui, M.A.; Guillemin, C.; Charron, F.; Leauthaud, C. A path towards precision border irrigation combining hydrodynamic modelling and in-field sensor-based support. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 316, 109518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonet, E.; Russo, B.; González, R.; Yubero, M.T.; Gómez, M.; Sánchez-Juny, M. The FC Algorithm to Estimate the Manning’s Roughness Coefficients of Irrigation Canals. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yan, P.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Lei, X.; Wang, H. Roughness Inversion of Water Transfer Channels from a Data-Driven Perspective. Water 2023, 15, 2822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronica, G.; Hankin, B.; Beven, K. Uncertainty and equifinality in calibrating distributed roughness coefficients in a flood propagation model with limited data. Adv. Water Resour. 1998, 22, 349–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.-J.; Zhao, L.-N. Hydraulic model with roughness coefficient updating method based on Kalman filter for channel flood forecast. Water Sci. Eng. 2011, 4, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, T.; Wang, H. Partition of one-dimensional river flood routing uncertainty due to boundary conditions and riverbed roughness. J. Hydrol. 2022, 608, 127660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, E.; Liu, G.; Dan, C.; Chen, X.; Ye, S.; Li, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z. Estimating Manning’s coefficient n for sheet flow during rainstorms. Catena 2023, 226, 107093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidoro, J.M.; Martins, R.; Pereira, L.G.; de Lima, J.L. Design and characterisation of customised-roughness beds for open-channel flow experiments. Flow Meas. Instrum. 2023, 94, 102472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsie, A.B.; Ayalew, A.T.; Mada, Z.M.; Finsa, M.M. Acclimatize experimental approach to adjudicate hydraulic coefficients under different bed material configurations and slopes with and without weir. Heliyon 2024, 10, e32162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burshtynska, K.; Zayats, I.; Halochkin, M.; Bakuła, K.; Babiy, L. The Influence of the Main Factors on the Accuracy of Hydrological Modelling of Flooded Lands. Water 2023, 15, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, L.-X. An improved two-point velocity method for estimating the roughness coefficient of natural channels. Phys. Chem. Earth Parts A/B/C 2010, 35, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedaghatdoost, A.; Ebrahimian, H. Calibration of infiltration, roughness and longitudinal dispersivity coefficients in furrow fertigation using inverse modelling with a genetic algorithm. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 136, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wells, R.R.; Momm, H.G.; Zhang, Y.; Bennett, S.J. Physically based numerical model for the landscape evolution of soil-mantled watersheds driven by rainfall and overland flow. J. Hydrol. 2023, 620, 129419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isma, F.; Kusuma, M.S.B.; Adityawan, M.B.; Nugroho, E.O. Spatiotemporal variations of Manning’s roughness coefficient in the estuary of Langsa River based on field measurements and hydraulic modeling. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 61, 102632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, M.; Hosseini, S.M. A Simple Innovative Method for Calibration of Manning’s Roughness Coefficient in Rivers using a Similarity Concept. J. Hydrol. 2019, 575, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attari, M.; Taherian, M.; Hosseini, S.M.; Niazmand, S.B.; Jeiroodi, M.; Mohammadian, A. A simple and robust method for identifying the distribution functions of Manning’s roughness coefficient along a natural river. J. Hydrol. 2021, 595, 125680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Mu, T.; Li, X.; Li, P.; Feng, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, C.; Qian, S. Physics-informed neural network for hydraulic prediction in open-channel water transfer projects with sparse monitoring data. Water Res. 2025, 287, 124507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zevallos, J.; Chávarri-Velarde, E.; Gutierrez, R.R.; Lavado, W. Bayesian calibration of a 2D hydraulic model using a convolutional neural network emulator. Environ. Model. Softw. 2025, 193, 106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessar, M.A.; Matte, P.; Anctil, F. Uncertainty Analysis of a 1D River Hydraulic Model with Adaptive Calibration. Water 2020, 12, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadian, A.; Morse, B.; Robert, J.-L. Calibration of a 3D hydrodynamic model for a hypertidal estuary with complex irregular bathymetry using adaptive parametrization of bottom roughness and eddy viscosity. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2022, 265, 107655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ara, I.; Turner, L.; Harrison, M.T.; Monjardino, M.; DeVoil, P.; Rodriguez, D. Application, adoption and opportunities for improving decision support systems in irrigated agriculture: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 257, 107161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Qu, Q.; Peng, S.; Wei, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, C. Deep learning for intelligent irrigation decision-making: A review. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 320, 109836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shao, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhai, X.; She, D. Multi-metric calibration of hydrological model to capture overall flow regimes. J. Hydrol. 2016, 539, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Cecilia, D.; Venezia, A.; Massa, D.; Camporese, M. From weather data to water fluxes simulation in Mediterranean greenhouses through a combined climate and hydrological modelling approach. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 311, 109386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitfogel, H.; Herrnegger, M.; Schulz, K. Regional-scale assessment of groundwater recharge and the water balance for Austria. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 59, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 21303-2017; Specifications for Water Measurement of Irrigation Canal System. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2017.

- Duan, Q.Y.; Gupta, V.K.; Sorooshian, S. Shuffled complex evolution approach for effective and efficient global minimization. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 1993, 76, 501–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almahawis, M.K.; Bailey, R.T.; Abbas, S.A.; Arnold, J.G.; White, M.J. Investigating the impact of irrigation practices on hydrologic fluxes in a highly managed river basin. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 301, 108954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.A.; Bailey, R.T.; Arnold, J.G.; White, M.J.; Mirchi, A. Modeling agro-hydrological surface-subsurface processes in a semi-arid, intensively irrigated river basin. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2025, 57, 102188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, L.; Bai, T.; Liu, D.; Ji, H.; Deng, M.; Hong, L. Ditch rotation irrigation coupled with multi-scale ecological reservoir operation. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 307, 109271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkhordari, S.; Hashemy Shahdany, S.M. Developing a smart operating system for fairly distribution of irrigation water, based on social, economic, and environmental considerations. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 250, 106833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, H.; Gao, Z.; Fan, Y.; Chang, X.; Yang, M.; Fang, B. Water distribution and scheduling model of an irrigation canal system. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 209, 107866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morchid, A.; Said, Z.; Abdelaziz, A.Y.; Siano, P.; Qjidaa, H. Fuzzy logic-based IoT system for optimizing irrigation with cloud computing: Enhancing water sustainability in smart agriculture. Smart Agric. Technol. 2025, 11, 100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offermans, N.; Massaro, D.; Peplinski, A.; Schlatter, P. Error-driven adaptive mesh refinement for unsteady turbulent flows in spectral-element simulations. Comput. Fluids 2023, 251, 105736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Zhou, X.; Ren, H.; Sutulo, S.; Soares, C.G. Real-time calculation of ship to ship hydrodynamic interaction in shallow waters with adaptive mesh refinement. Ocean Eng. 2024, 295, 116943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Cai, H.; Saddique, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, L.; Ma, C.; Lu, Y. Evaluation and optimization of border irrigation in different irrigation seasons based on temporal variation of infiltration and roughness. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 214, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, M.; Kumar, B. Flow and bedform dynamics in an alluvial channel with downward seepage. Catena 2017, 158, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).