A 21-Year Analysis of Turbidity Variability in Cartagena Bay: Seasonal Patterns and the Influence of ENSO

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

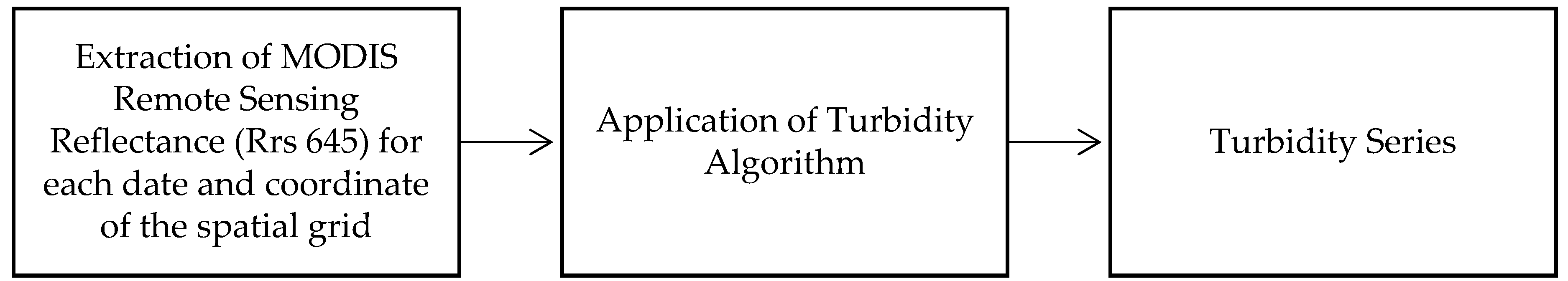

2.2. Image Processing

2.3. Turbidity Time Series

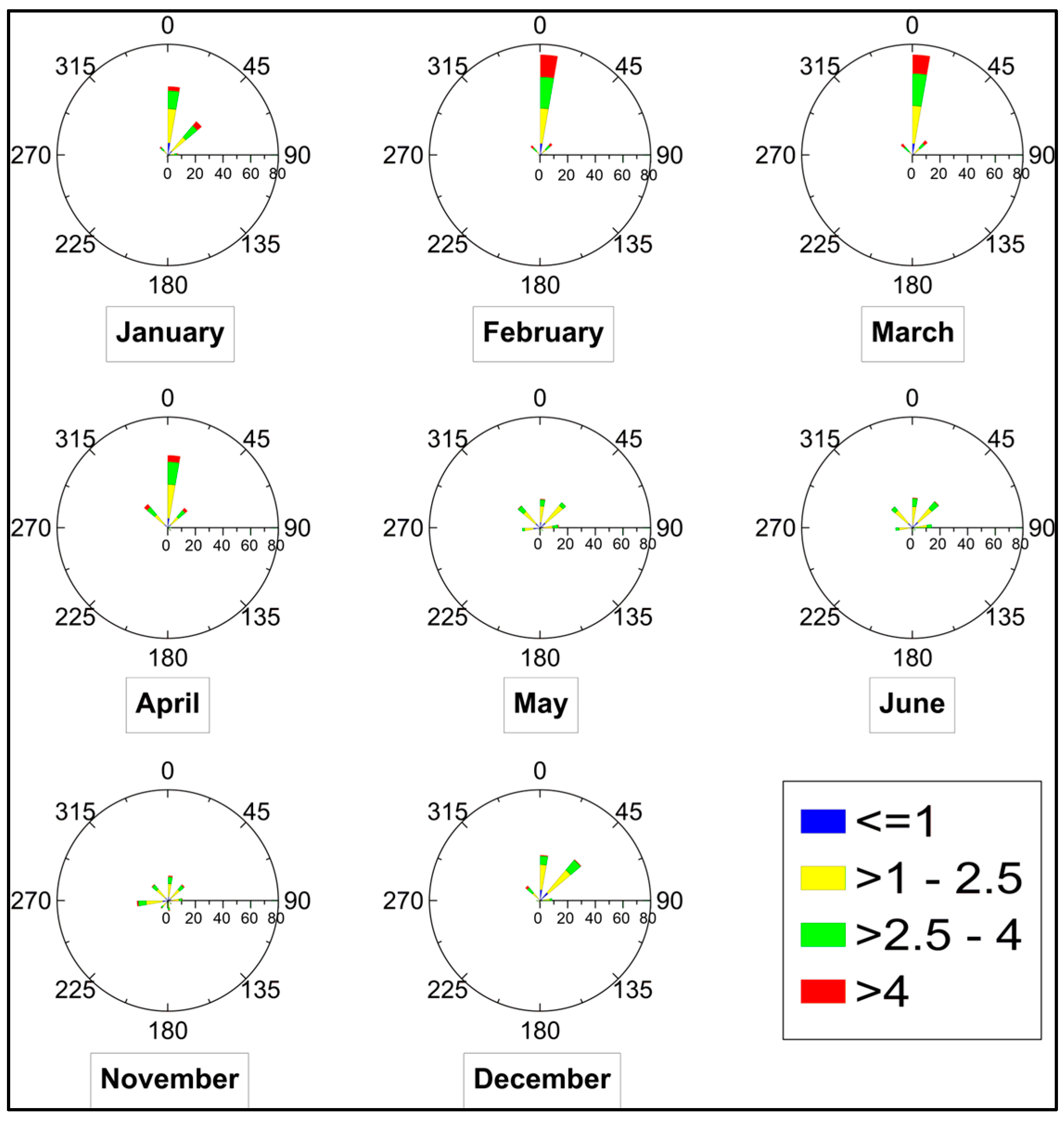

2.4. Seasonal and Spatial Turbidity Variability

2.5. ENSO-Related Anomaly Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. MODIS Images

3.2. Validation of Algorithm with MODIS Data

3.3. Seasonal and Spatial Turbidity Patterns

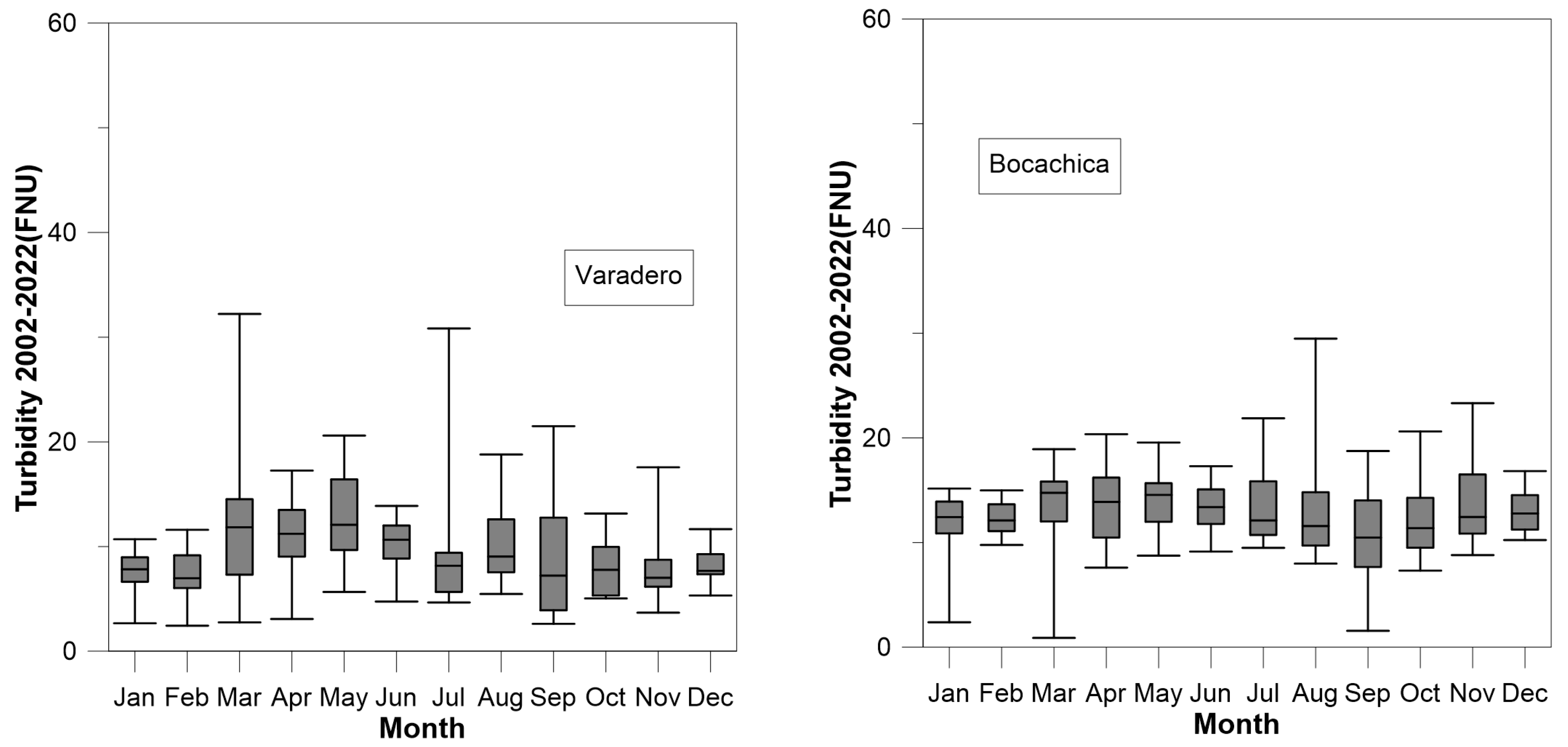

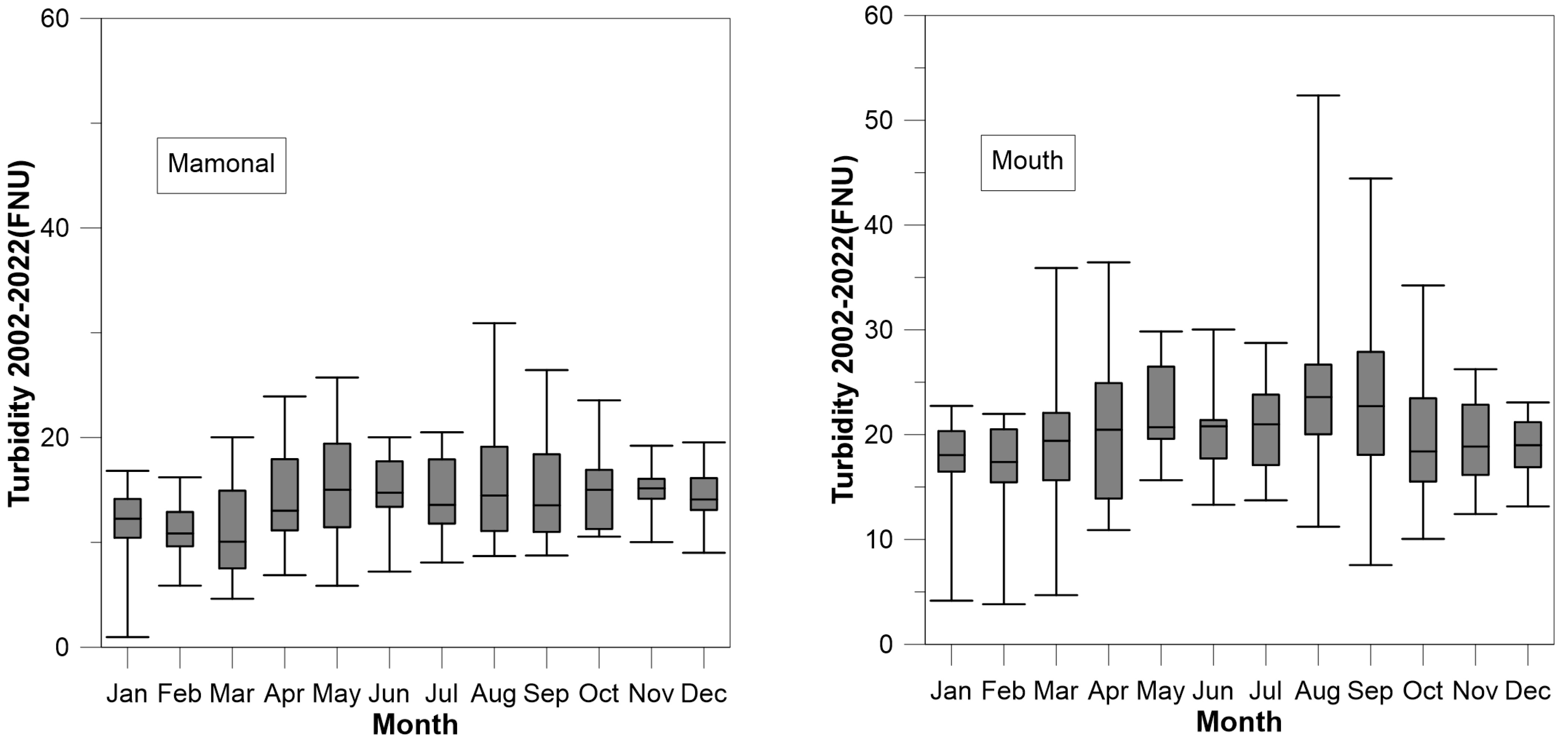

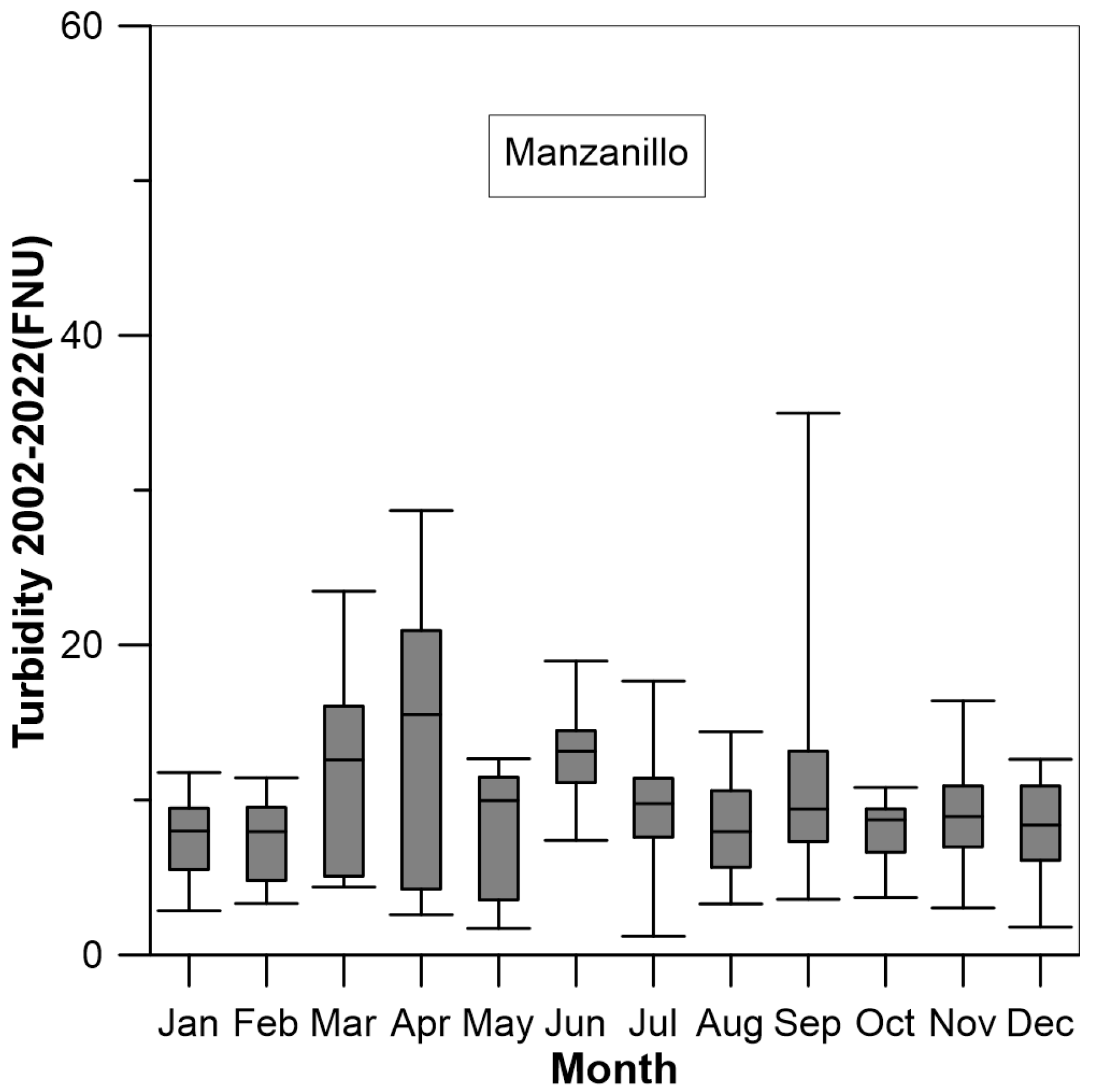

3.4. Turbidity Spatial Distribution in Cartagena Bay

3.5. Turbidity Trends in Cartagena Bay

3.6. ENSO Influence on Turbidity Variability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tuchkovenko, Y.S.; Lonin, S.A. Mathematical model of the oxygen regime of Cartagena Bay. Ecol. Modell. 2003, 165, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invemar. Diagnóstico y Evaluación de la Calidad de las Aguas Marinas y Costeras en el Caribe y Pacífico Colombianos; Espinosa, L.F., Obando, P., Garcés, O., Eds.; Informe Técnico 2019; REDCAM-INVEMAR: Santa Marta, Colombia, 2020. Available online: https://www.invemar.org.co/documents/37438/75549/Informe+REDCAM_2019.pdf/9133403e-4b7b-e4bd-69e1-df4f5841b1f7?t=1670244369911 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Cherukuru, N.; Martin, P.; Sanwlani, N.; Mujahid, A.; Müller, M. A semi-analytical optical remote sensing model to estimate suspended sediment and dissolved organic carbon in tropical coastal waters influenced by peatland-draining river discharges off sarawak, borneo. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabiri, K.; Moradi, M. Landsat-8 imagery to estimate clarity in near-shore coastal waters: Feasibility study—Chabahar Bay, Iran. Cont. Shelf Res. 2016, 125, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Távora, J.; Fernandes, E.H.; Bitencourt, L.P.; Orozco, P.M.S. El-Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) effects on the variability of Patos Lagoon Suspended Particulate Matter. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 40, 101495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, J.C.; Escobar, J.; Otero, L.; Franco, D.; Pierini, J.; Correa, I. Factors Influencing the Distribution and Characteristics of Surface Sediment in the Bay of Cartagena, Colombia. Coast. Educ. Res. Found. 2017, 33, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosic, M.; Restrepo, J.D.; Lonin, S.; Izquierdo, A.; Martins, F. Water and sediment quality in Cartagena Bay, Colombia: Seasonal variability and potential impacts of pollution. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2019, 216, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, J.D.; Zapata, P.; Díaz, J.M.; Garzón-Ferreira, J.; García, C.B.; Restrepo, J.C. Aportes Fluviales al mar Caribe y Evaluación Preliminar del Impacto Sobre los Ecosistemas Costeros; Universidad Eafit: Medellín, Colombia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, J.D.; Escobar, R.; Tosic, M. Fluvial fluxes from the Magdalena River into Cartagena Bay, Caribbean Colombia: Trends, future scenarios, and connections with upstream human impacts. Geomorphology 2018, 302, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seers, B.M.; Shears, N.T. Spatio-temporal patterns in coastal turbidity—Long-term trends and drivers of variation across an estuarine-open coast gradient. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 154, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunus, A.P.; Masago, Y.; Hijioka, Y. Analysis of long-term (2002–2020) trends and peak events in total suspended solids concentrations in the Chesapeake Bay using MODIS imagery. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 299, 113550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechad, B.; Ruddick, K.G.; Neukermans, G. Calibration and validation of a generic multisensor algorithm for mapping of turbidity in coastal waters. In Remote Sensing of the Ocean, Sea Ice, and Large Water Regions; Bostater, C., Mertikas, S.P., Neyt, X., Velez-Reyes, M., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dogliotti, A.; Ruddick, K.G.; Nechad, B.; Doxaran, D.; Knaeps, E. A single algorithm to retrieve turbidity from remotely-sensed data in all coastal and estuarine waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 156, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petus, C.; Marieu, V.; Novoa, S.; Chust, G.; Bruneau, N.; Froidefond, J.M. Monitoring spatio-temporal variability of the Adour River turbid plume (Bay of Biscay, France) with MODIS 250-m imagery. Cont. Shelf Res. 2014, 74, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Hu, C.; Muller-Karger, F. Monitoring turbidity in Tampa Bay using MODIS/Aqua 250-m imagery. Remote Sens. Env. 2007, 109, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Wang, X.H.; Ritchie, E.A.; Qiao, L.; Li, G.; Cheng, Z. Using 250-M Surface Reflectance MODIS Aqua/Terra Product to Estimate Turbidity in a Macro-Tidal. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, L.F.; de Carvalho, L.S.; Cirano, M.; Barberini, F.D.; Maciel, D.A.; Lange, P.K.; Soares, F.S.; Ciotti, A.M. Regional Studies in Marine Science The seasonal and tidal effects on turbidity in Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro-Brazil. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 90, 104449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eljaiek-Urzola, M.; Sander De Carvalho, L.A.; Betancur-Turizo, S.P.; Quiñones-Bolaños, E.; Castrillon-Ortiz, C. Spatial Patterns of Turbidity in Cartagena Bay, Colombia, Using Sentinel-2 Imagery. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldías, G.S.; Strub, P.T.; Shearman, R.K. Spatio-temporal variability and ENSO modulation of turbid freshwater plumes along the Oregon coast. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2020, 243, 106880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, L. Study on the Seasonal Estuarine Turbidity Maximum Variations of the Yangtze Estuary, China. J. Waterw. Port. Coast. Ocean. Eng. 2018, 144, 5018002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa, Á.K.R.; Pereira, L.C.C.; Jiménez, J.A.; de Oliveira, A.R.G.; de Jesus Flores-Montes, M.; da Costa, R.M. Effects of Extreme Climatic Events on the Hydrological Parameters of the Estuarine Waters of the Amazon Coast. Estuaries Coasts 2022, 45, 1517–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogliotti, A.; Ruddick, K.; Guerrero, R. Seasonal and inter-annual turbidity variability in the Río de la Plata from 15 years of MODIS: El Niño dilution effect. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 182, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolanski, E.; Elliott, M. 3—Estuarine sediment dynamics. In Estuarine Ecohydrology, 2nd ed.; Wolanski, E., Elliott, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Boston, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 77–125. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780444633989000039 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- DIMAR-CIOH. Carta Náutica 261—Bahía de Cartagena. Escala 25.000. Catálogo de Cartas Náuticas de Colombia. 13 April 2021. Available online: www.dimar.mil.co/dimar-presenta-actualizacion-de-la-carta-nautica-262-bahia-de-cartagena (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Molares, R.; Mestres, M. Efectos de la descarga estacional del Canal del Dique en el mecanismo de intercambio de aguas de una bahía semicerrada y micromareal: Bahía de Cartagena, Colombia. Boletín Científico CIOH 2012, 45, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IDEAM. Consulta y Descarga de Datos Hidrometeorológicos. 2023. Available online: http://dhime.ideam.gov.co/atencionciudadano/ (accessed on 14 November 2023).

- Lonin, S.; Parra, C.; Andrade, C.; Thomas, Y.F. Patrones de la pluma turbia del canal del Dique en la bahía de Cartagena. Boletín Científico CIOH 2004, 22, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonin, S.; Giraldo, L. Circulación de las aguas y transporte de contaminantes en la Bahía Interna de Cartagena. Boletín Científico CIOH 1995, 16, 25–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twedt, K.A.; Xiong, X.; Geng, X.; Wilson, T.; Mu, Q. Impact of satellite orbit drift on MODIS Earth scene observations used in calibration of the reflective solar bands. In Proceedings of the SPIE Optics + Photonics 2023 Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 20–24 August 2023; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- NASA. MODIS—Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer. 2024. Available online: https://modis.gsfc.nasa.gov/data/ (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Katlane, R.; El Kilani, B.; Dhaoui, O.; Kateb, F.; Chehata, N. Monitoring of sea surface temperature, chlorophyll, and turbidity in Tunisian waters from 2005 to 2020 using MODIS imagery and the Google Earth Engine. Reg Stud Mar Sci 2023, 66, 103143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sousa, F.F. Cloud_Filter_for_Google_Earth_Engine. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/felipefariadesousa/Cloud_filter_for_google_earth_engine/blob/main/Examples/Cloud_filter_Landsat.js (accessed on 22 May 2024).

- Principe, R. Geetools-Code-Editor-Code-Editor: A Set of Tools to Use in Google Earth Engine Code Editor (JavaScript). 2019. Available online: https://github.com/fitoprincipe/geetools-code-editor (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Hedley, J.D.; Harborne, A.R.; Mumby, P.J. Simple and robust removal of sun glint for mapping shallow-water benthos. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2005, 26, 2107–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouillon, S.; Douillet, P.; Petrenko, A.; Neveux, J.; Froidefond, J.M.; Caledonia, N. Optical Algorithms at Satellite Wavelengths for Total Suspended Matter in Tropical Coastal Waters. Sensors 2008, 8, 4165–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría-del-Ángel, E.; Sebastia-Frasquet, M.; González-Silvera, A.; Aguilar-Maldonado, J.; Mercado-Santana, A.; Herrera-Carmona, J. Uso Potencial de las Anomalías Estandarizadas en la Interpretación de Fenómenos Oceanográficos Globales a Escalas Locales. In Tópicos Agenda Para la Sostenibilidad Costas y Mares Méxicanos; Instituto de Ecología, Pesquerías y Oceanografía del Golfo de México (epomex) Universidad Autónoma de Campeche: Campeche, Mexico, 2019; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Villalba, R.; Ferral, A.; Baez, J.; Kurita, J.; Beltramone, G.; Bertoni, J.C. Temporal Analysis of Precipitation in the Lower and Middle Paraguay Basin within the La Plata Basin (2001–2020) and its Relationship with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO) Phenomenon. In Proceedings of the 2023 XX Workshop on Information Processing and Control (RPIC), Oberá, Argentina, 1–3 November 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Góez Arango, C.; Poveda Jaramillo, G. Variabilidad de las anomalías y de la escala de fluctuación de caudales medios mensuales con el área de la cuenca. Av. En. Recur. Hidráulicos 2005, 12, 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Mo, Z.; Zhao, J.; Ma, C. Remote monitoring of water clarity in coastal oceans of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, China based on machine learning. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, S.; Lao, Q.; Chen, C.; Fu, D.; Chen, F. Remote Sensing Estimates of Particulate Organic Carbon Sources in the Zhanjiang Bay Using Sentinel-2 Data and Carbon Isotopes. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yu, D.; Cheng, W.; Gai, Y.; Yao, H.; Yang, L.; Pan, S. Monitoring multi-temporal and spatial variations of water transparency in the Jiaozhou Bay using GOCI data. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 180, 113815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantin, S.; Doxaran, D.; Constantinescu, S. Estimation of water turbidity and analysis of its spatio-temporal variability in the Danube River plume (Black Sea) using MODIS satellite data. Cont. Shelf Res. 2016, 112, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nechad, B.; Ruddick, K.G.; Park, Y. Remote Sensing of Environment Calibration and validation of a generic multisensor algorithm for mapping of total suspended matter in turbid waters. Remote Sens. Environ. 2010, 114, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, O.; Carvajal, Y. Incidencia de El Niño-Oscilación del Sur en la precipitación y la temperatura del aire en Colombia, utilizando el Climate Explorer. Rev. Científica Ing. Y Desarro. 2008, 23, 104–118. [Google Scholar]

- Beier, E.; Bernal, G.; Ruiz-Ochoa, M.; Barton, E.D. Freshwater exchanges and surface salinity in the Colombian basin, Caribbean Sea. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenssen, N.J.L.; Goddard, L.; Mason, S. Seasonal forecast skill of enso teleconnection maps. Weather Forecast. 2020, 35, 2387–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, M.J.; Otis, D.B.; Méndez-Lázaro, P.; Muller-Karger, F.E. Water quality drivers in 11 Gulf of Mexico Estuaries. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright, P.J.; Fearns, P.R.C.S.; Branson, P.; Cuttler, M.V.W.; O’leary, M.; Browne, N.K.; Lowe, R.J. Identifying metocean drivers of turbidity using 18 years of MODIS satellite data: Implications for marine ecosystems under climate change. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khadami, F.; Tarya, A.; Radjawane, I.M.; Suprijo, T.; Sujatmiko, K.A.; Anwar, I.P.; Hidayatullah, M.F.; Erlangga, M.F.R.A. Understanding Two Decades of Turbidity Dynamics in a Coral Triangle Hotspot: The Berau Coastal Shelf. Water 2024, 16, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Month | St. Varadero | St. Bocachica | St. Mamonal | St. Manzanillo | St. Mouth | Entire Bay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan. | 181 | 213 | 212 | 101 | 218 | 223 |

| Feb. | 91 | 105 | 111 | 32 | 101 | 107 |

| Mar. | 39 | 57 | 66 | 14 | 58 | 57 |

| Apr. | 36 | 35 | 30 | 11 | 34 | 22 |

| May | 31 | 24 | 27 | 11 | 23 | 9 |

| Jun. | 43 | 54 | 43 | 19 | 47 | 28 |

| Jul. | 42 | 63 | 56 | 41 | 63 | 49 |

| Aug. | 38 | 31 | 41 | 29 | 55 | 33 |

| Sep. | 25 | 24 | 20 | 14 | 36 | 13 |

| Oct. | 13 | 25 | 19 | 11 | 27 | 12 |

| Nov. | 35 | 59 | 39 | 34 | 58 | 34 |

| Dec. | 132 | 180 | 188 | 93 | 184 | 181 |

| Total | 706 | 870 | 852 | 410 | 904 | 768 |

| Relationship | Lag (Months) | r (Max) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOI → Turbidity | +2 | 0.17 | 0.28 |

| SOI → Discharge | 0 | 0.42 | 0.03 |

| Rainfall → Discharge | 0 | 0.55 | 0.01 |

| Discharge → Turbidity | +1 | 0.47 | 0.02 |

| Study Region | ENSO Phase | Study Period | Data Source | Effect on Turbidity/Sediments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Río de la Plata Estuary | Niña: Low Precipitation Niño: High Precipitation | 2000–2014 | Derived from a remote sensing algorithm applied to MODIS data | ENSO cycles have a significant influence on turbidity variability. Turbidity tends to decrease during El Niño due to increased freshwater discharge, while higher values are observed in some La Niña years. However, the complex response of tributaries results in spatially and temporally variable sediment dynamics. | [22] |

| 11 Gulf of Mexico Estuaries | Niña: Low Precipitation Niño: High Precipitation | 2000–2014 | Derived from a remote sensing algorithm applied to MODIS data | Wind speed was the most consistent factor explaining turbidity variability. ENSO emerged as a significant factor in some cases, although its relationship with turbidity was inconsistent and, in many cases, statistically questionable. River flow also proved to be a key factor, especially at the seasonal and annual scales. | [47] |

| Patos Lagoon, Brazil | Niña: Low Precipitation Niño: High Precipitation | 2003–2019 | Derived from a remote sensing algorithm applied to MODIS data | SPM levels in Patos Lagoon increase during El Niño events due to strong northeasterly winds, intensified rainfall, and greater river discharge. In contrast, La Niña conditions, marked by southwesterly winds, low precipitation, and reduced discharge, lead to significantly lower SPM concentrations. | [5] |

| Exmouth Gulf, Australia. | Niña: High Precipitation Niño: Low Precipitation | 2002–2020 | Derived from a remote sensing algorithm applied to MODIS data | Turbidity trends in the Gulf are strongly influenced by the ENSO and IOD (Indian Ocean Dipole) cycles, as well as winds from adjacent land areas, Turbidity in the Gulf exhibits a strong spatial and temporal relationship with environmental variables such as wind, waves, sea level, precipitation, and the global ENSO and IOD climate cycles. However, the magnitude and direction of these effects vary within the Gulf, highlighting the complexity of the hydrodynamic processes that control water quality. | [48] |

| Coral Triangle Hotspot: The Berau Coastal Shelf, Indonesia | Niña: High Precipitation Niño: Low Precipitation | 2003–2022 | Derived from a remote sensing algorithm applied to MODIS data | Turbidity on the Berau coastal shelf is strongly influenced by regional climatic factors: La Niña leads to increased turbidity and precipitation, while El Niño results in decreased turbidity and precipitation. | [49] |

| New Zealand’s Hauraki Gulf, | Niña: High Precipitation Niño: Low Precipitation | 1992–2013 | In Situ | Turbidity exhibits seasonal fluctuations that are only weakly linked to ENSO due to the combined effects of tidal currents and localized precipitation. | [10] |

| This study | Niña: High Precipitation Niño: Low Precipitation | 2002–2022 | Derived from a remote sensing algorithm applied to MODIS data | Although ENSO moderately influences freshwater discharge, no direct relationship with turbidity levels in Cartagena Bay was identified (especially during La Niña events). While the sediment input from the Canal del Dique plays a key role in turbidity, its spatial distribution within the bay is largely influenced by local hydrodynamic processes such as tides and currents. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Eljaiek-Urzola, M.; Sander de Carvalho, L.A.; Quiñones-Bolaños, E.; Betancur-Turizo, S.P.; Faria de Sousa, L.F.M. A 21-Year Analysis of Turbidity Variability in Cartagena Bay: Seasonal Patterns and the Influence of ENSO. Water 2025, 17, 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243447

Eljaiek-Urzola M, Sander de Carvalho LA, Quiñones-Bolaños E, Betancur-Turizo SP, Faria de Sousa LFM. A 21-Year Analysis of Turbidity Variability in Cartagena Bay: Seasonal Patterns and the Influence of ENSO. Water. 2025; 17(24):3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243447

Chicago/Turabian StyleEljaiek-Urzola, Monica, Lino Augusto Sander de Carvalho, Edgar Quiñones-Bolaños, Stella Patricia Betancur-Turizo, and Luiz Felipe Machado Faria de Sousa. 2025. "A 21-Year Analysis of Turbidity Variability in Cartagena Bay: Seasonal Patterns and the Influence of ENSO" Water 17, no. 24: 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243447

APA StyleEljaiek-Urzola, M., Sander de Carvalho, L. A., Quiñones-Bolaños, E., Betancur-Turizo, S. P., & Faria de Sousa, L. F. M. (2025). A 21-Year Analysis of Turbidity Variability in Cartagena Bay: Seasonal Patterns and the Influence of ENSO. Water, 17(24), 3447. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17243447