Ephemeral Channel Expansion: Predicting Shifts Toward Intermittency in Vulnerable Streams Across Semi-Arid CONUS

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Gage Selection

2.2. Trend Analysis: Stream Drying

2.3. Variable Selection and Data Collection

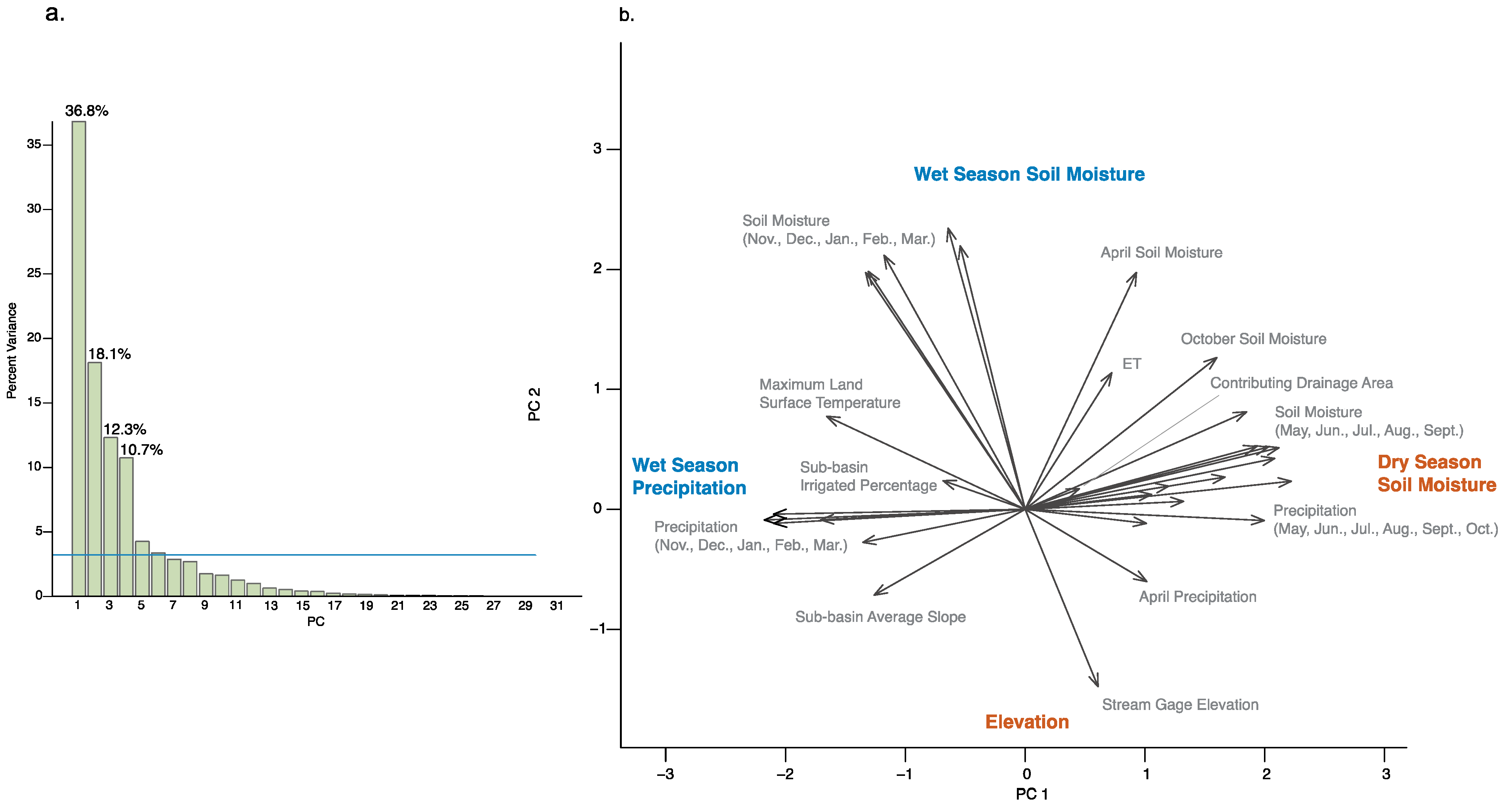

2.4. Discriminant Function Analysis and Principal Component Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Trends in Stream Drying

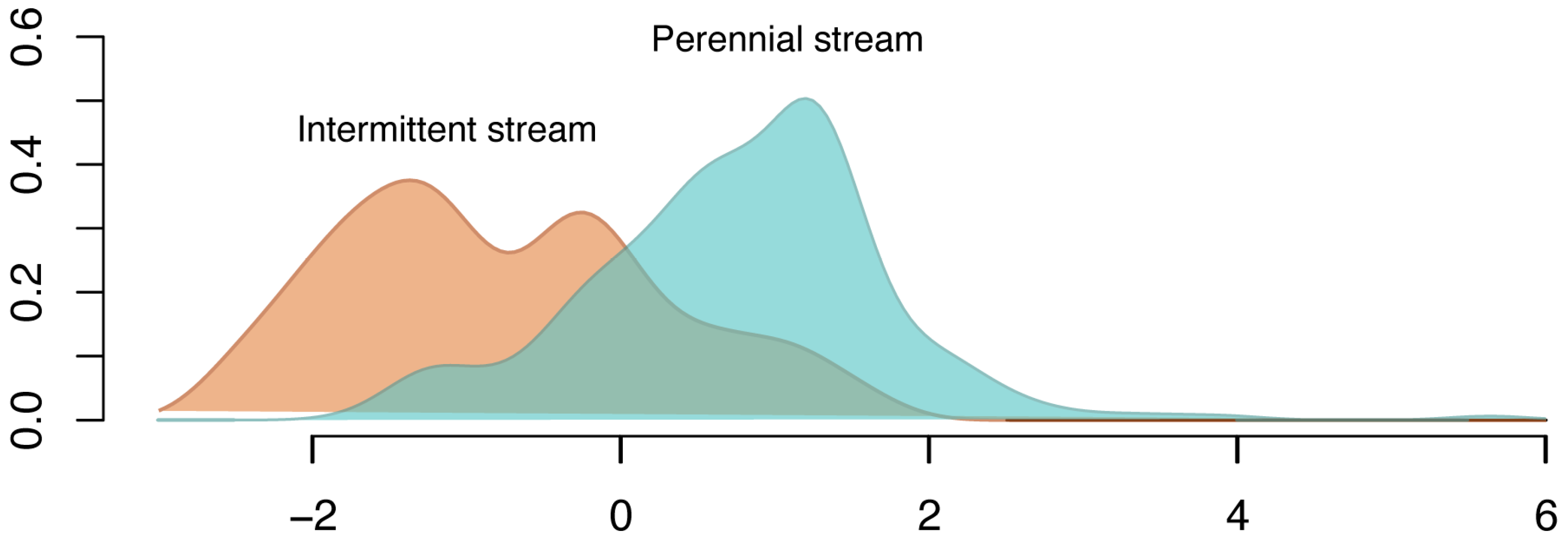

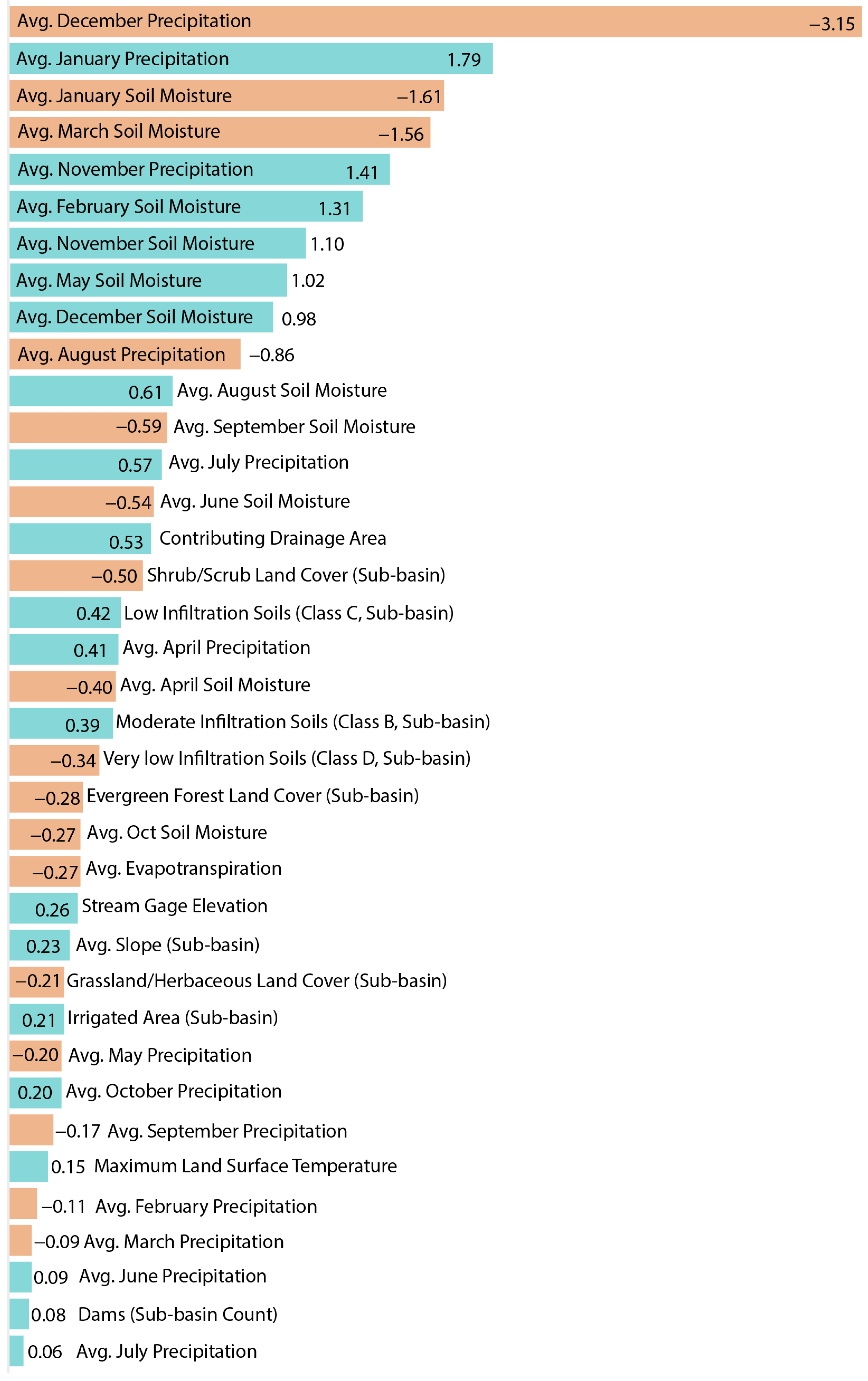

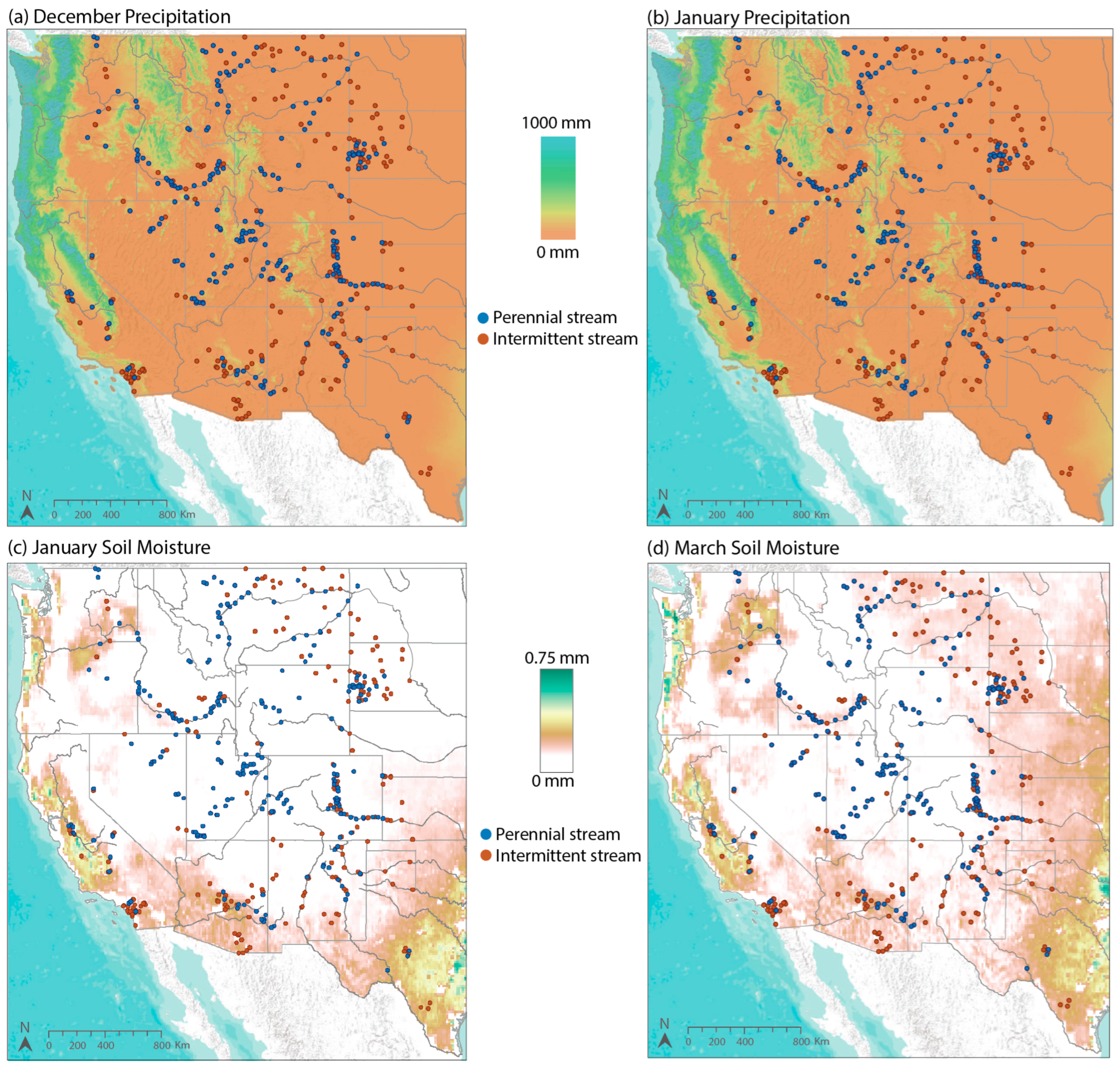

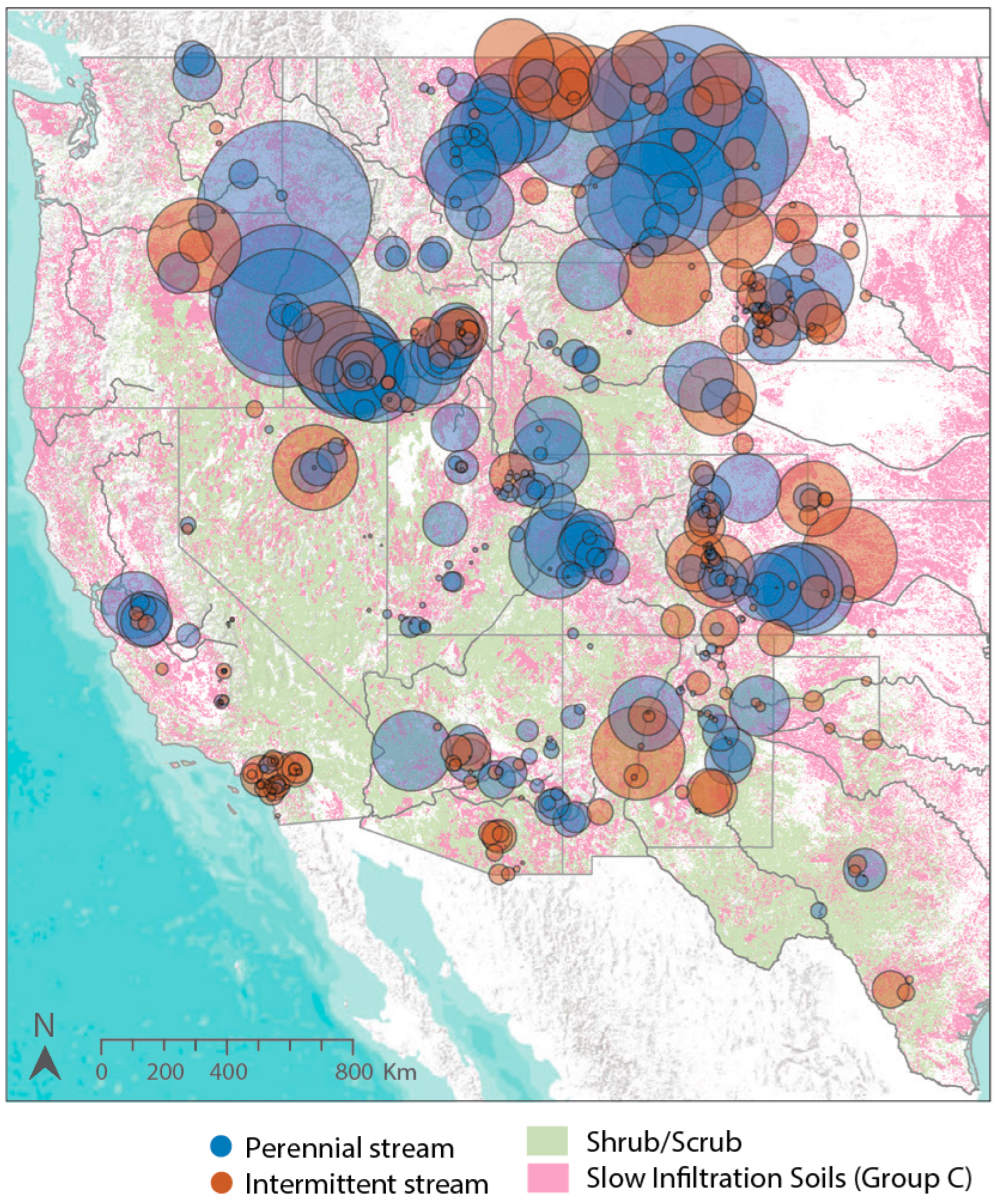

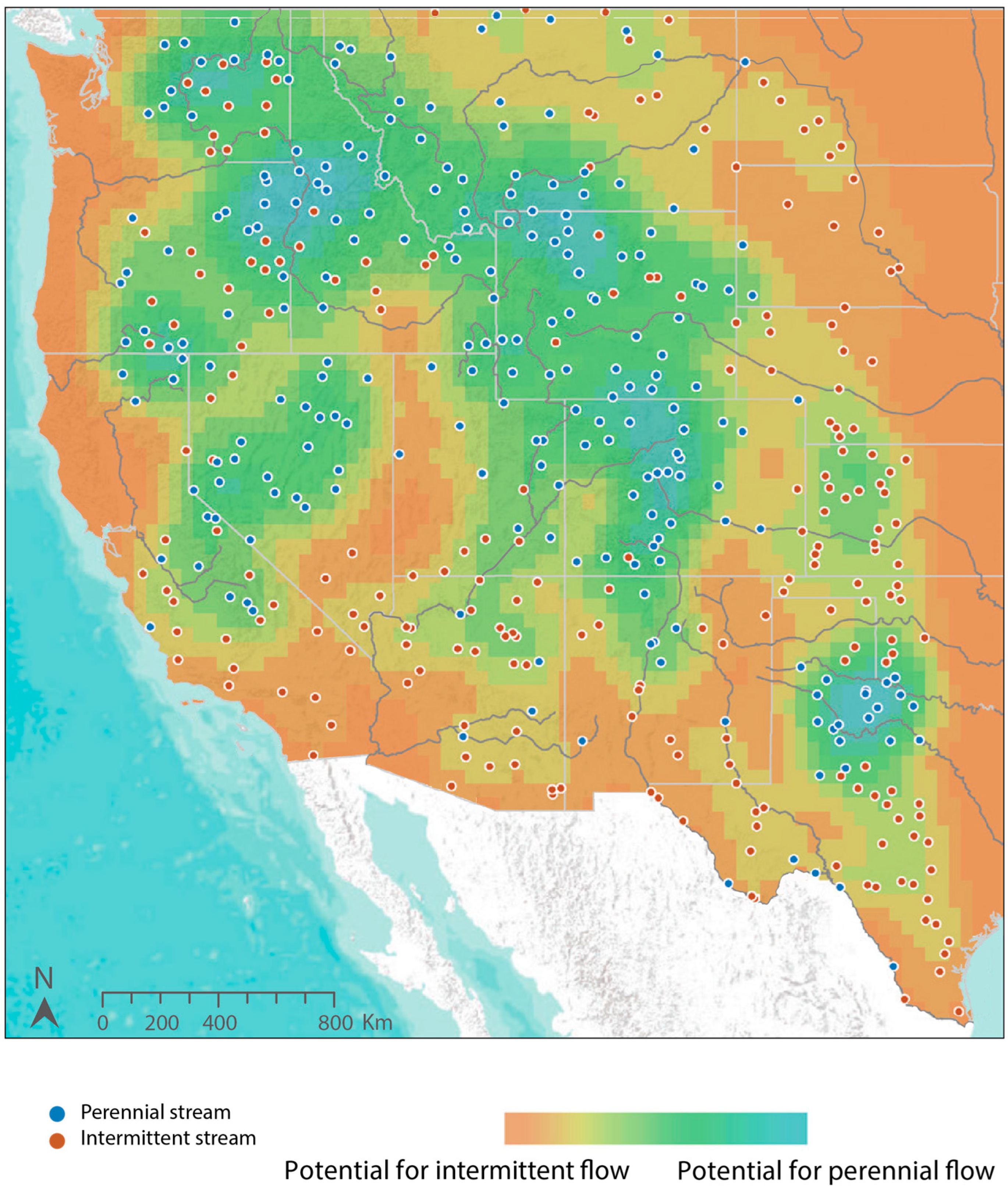

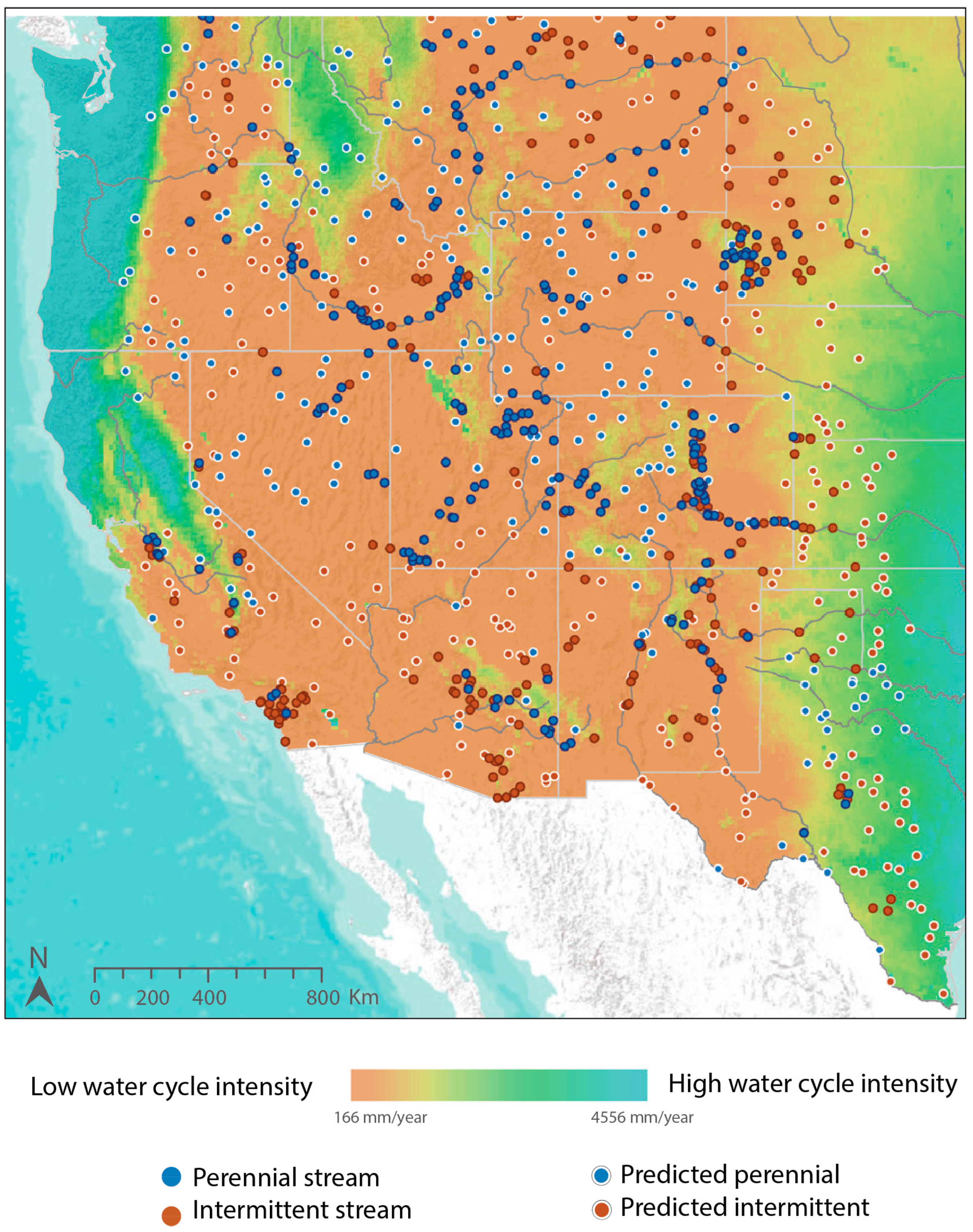

3.2. Differentiating Drivers of Perennial and Intermittent Flow Regimes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lins, H.F.; Slack, J.R. Seasonal and Regional Characteristics of U.S. Streamflow Trends in the United States from 1940 to 1999. Phys. Geogr. 2005, 26, 489–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficklin, D.L.; Robeson, S.M.; Knouft, J.H. Impacts of Recent Climate Change on Trends in Baseflow and Stormflow in United States Watersheds. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 5079–5088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudley, R.W.; Hirsch, R.M.; Archfield, S.A.; Blum, A.G.; Renard, B. Low Streamflow Trends at Human-Impacted and Reference Basins in the United States. J. Hydrol. 2020, 580, 124254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dethier, E.N.; Sartain, S.L.; Renshaw, C.E.; Magilligan, F.J. Spatially Coherent Regional Changes in Seasonal Extreme Streamflow Events in the United States and Canada since 1950. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba5939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, J.C.; Zimmer, M.; Shanafield, M.; Kaiser, K.; Godsey, S.E.; Mims, M.C.; Zipper, S.C.; Burrows, R.M.; Kampf, S.K.; Dodds, W.; et al. Spatial Patterns and Drivers of Nonperennial Flow Regimes in the Contiguous United States. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2020GL090794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipper, S.C.; Farmer, W.H.; Brookfield, A.; Ajami, H.; Reeves, H.W.; Wardropper, C.; Hammond, J.C.; Gleeson, T.; Deines, J.M. Quantifying Streamflow Depletion from Groundwater Pumping: A Practical Review of Past and Emerging Approaches for Water Management. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2022, 58, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, J.C.; Simeone, C.; Hecht, J.S.; Hodgkins, G.A.; Lombard, M.; McCabe, G.; Wolock, D.; Wieczorek, M.; Olson, C.; Caldwell, T.; et al. Going Beyond Low Flows: Streamflow Drought Deficit and Duration Illuminate Distinct Spatiotemporal Drought Patterns and Trends in the U.S. During the Last Century. Water Resour. Res. 2022, 58, e2022WR031930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seager, R.; Neelin, D.; Simpson, I.; Liu, H.; Henderson, N.; Shaw, T.; Kushnir, Y.; Ting, M.; Cook, B. Dynamical and Thermodynamical Causes of Large-Scale Changes in the Hydrological Cycle over North America in Response to Global Warming. J. Clim. 2014, 27, 7921–7948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, M.; Seager, R.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Henderson, N. Mechanism of Future Spring Drying in the Southwestern United States in CMIP5 Models. J. Clim. 2018, 31, 4265–4279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zowam, F.J.; Milewski, A.M.; Richards IV, D.F. A Satellite-Based Approach for Quantifying Terrestrial Water Cycle Intensity. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Climate Change Indicators in the United States, 5th ed.; EPA 430-R-24-003; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Scheff, J.; Frierson, D.M.W. Robust Future Precipitation Declines in CMIP5 Largely Reflect the Poleward Expansion of Model Subtropical Dry Zones. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, H.E.; Zimmermann, N.E.; McVicar, T.R.; Vergopolan, N.; Berg, A.; Wood, E.F. Present and Future Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification Maps at 1-Km Resolution. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodrich, D.C.; Kepner, W.G.; Levick, L.R.; Wigington, P.J., Jr. Southwestern Intermittent and Ephemeral Stream Connectivity. JAWRA J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 2018, 54, 400–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levick, L.; Fonseca, J.; Goodrich, D.; Hernandez, M.; Semmens, D.; Stromberg, J.; Leidy, R.; Scianni, M.; Guertin, D.P.; Tluczek, M.; et al. The Ecological and Hydrological Significance of Ephemeral and Intermittent Streams in the Arid and Semi-Arid American Southwest; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Gleeson, T.; Cuthbert, M.; Ferguson, G.; Perrone, D. Global Groundwater Sustainability, Resources, and Systems in the Anthropocene. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 48, 431–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Tang, G.; Chen, T.; Niu, X. An Assessment of the Impacts of Snowmelt Rate and Continuity Shifts on Streamflow Dynamics in Three Alpine Watersheds in the Western U.S. Water 2022, 14, 1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, K.L.; Olden, J.D.; Pelland, N.A. Climate Change Poised to Threaten Hydrologic Connectivity and Endemic Fishes in Dryland Streams. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13894–13899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costigan, K.H.; Jaeger, K.L.; Goss, C.W.; Fritz, K.M.; Goebel, P.C. Understanding Controls on Flow Permanence in Intermittent Rivers to Aid Ecological Research: Integrating Meteorology, Geology and Land Cover: Integrating Science to Understand Flow Intermittence. Ecohydrology 2016, 9, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, O.S.; Cook, P.G.; Grierson, P.F.; Dogramaci, S.; Simmons, C.T. Controls on Interactions Between Surface Water, Groundwater, and Riverine Vegetation Along Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams in Arid Regions. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2020WR028429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauquet, E.; Shanafield, M.; Hammond, J.C.; Sefton, C.; Leigh, C.; Datry, T. Classification and Trends in Intermittent River Flow Regimes in Australia, Northwestern Europe and USA: A Global Perspective. J. Hydrol. 2021, 597, 126170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, B.T.; Bruckerhoff, L.A. Dry, Drier, Driest: Differentiating Flow Patterns across a Gradient of Intermittency. River Res. Appl. 2024, 40, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datry, T.; Larned, S.T.; Tockner, K. Intermittent Rivers: A Challenge for Freshwater Ecology. BioScience 2014, 64, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messager, M.L.; Lehner, B.; Cockburn, C.; Lamouroux, N.; Pella, H.; Snelder, T.; Tockner, K.; Trautmann, T.; Watt, C.; Datry, T. Global Prevalence of Non-Perennial Rivers and Streams. Nature 2021, 594, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.A.; Burgin, A.J.; Kaiser, K.; Hosen, J. The Unknown Biogeochemical Impacts of Drying Rivers and Streams. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, K.; Sando, R.; McShane, R.R.; Dunham, J.B.; Hockman-Wert, D.; Kaiser, K.; Hafen, K.; Risley, J.C.; Blasch, K. Probability of Streamflow Permanence Model (PROSPER): A Spatially Continuous Model of Annual Streamflow Permanence throughout the Pacific Northwest. J. Hydrol. X 2018, 2, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zipper, S.C.; Hammond, J.C.; Shanafield, M.; Zimmer, M.; Datry, T.; Jones, C.N.; Kaiser, K.E.; Godsey, S.E.; Burrows, R.M.; Blaszczak, J.R.; et al. Pervasive Changes in Stream Intermittency across the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 084033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, K.; Wolock, D.M.; Dettinger, M.D. Sensitivity of Intermittent Streams to Climate Variations in the USA. River Res. Appl. 2016, 32, 885–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Gallardo, M.; Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Hannaford, J.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Svoboda, M.; Domínguez-Castro, F.; Maneta, M.; Tomas-Burguera, M.; Kenawy, A.E. Complex Influences of Meteorological Drought Time-Scales on Hydrological Droughts in Natural Basins of the Contiguous Unites States. J. Hydrol. 2019, 568, 611–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, S.K.; Dwire, K.A.; Fairchild, M.P.; Dunham, J.; Snyder, C.D.; Jaeger, K.L.; Luce, C.H.; Hammond, J.C.; Wilson, C.; Zimmer, M.A.; et al. Managing Nonperennial Headwater Streams in Temperate Forests of the United States. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 497, 119523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketchum, D.; Hoylman, Z.H.; Huntington, J.; Brinkerhoff, D.; Jensco, K.G. Irrigation Intensification Impacts Sustainability of Streamflow in the Western United States. Commun. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, B.L.; Hamada, Y.; Bowen, E.E.; Grippo, M.A.; Hartmann, H.M.; Patton, T.L.; Van Lonkhuyzen, R.A.; Carr, A.E. Quantifying the Sensitivity of Ephemeral Streams to Land Disturbance Activities in Arid Ecosystems at the Watershed Scale. Environ. Monit Assess 2014, 186, 7075–7095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovach, R.; Dunham, J.; Al-Chokhachy, R.; Snyder, C.; Letcher, B.; Young, J.; Beever, E.; Pederson, G.; Lynch, A.; Hitt, N.; et al. An Integrated Framework for Ecological Drought across Riverscapes of North America. BioScience 2019, 69, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulton, A.J.; Rolls, R.J.; Jaeger, K.L.; Datry, T. Chapter 2.3—Hydrological Connectivity in Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams. In Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams; Datry, T., Bonada, N., Boulton, A., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 79–108. ISBN 978-0-12-803835-2. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Geological Survey USGS. National Water Information System (NWIS); Water Data for the Nation: Reston, VA, USA, 2001.

- DeCicco, L. Water/dataRetrieval·GitLab. Available online: https://code.usgs.gov/water/dataRetrieval (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Department of Agriculture; Natural Resources Conservation Service. Federal Standards and Procedures for the National Watershed Boundary Dataset (WBD), 4th ed.; U.S. Geological Survey, Techniques and Methods 11–A3; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2013; p. 63.

- Mann, H.B. Nonparametric Tests Against Trend. Econometrica 1945, 13, 245–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, M.G. Rank Correlation Methods; C. Griffin: Spokane, WA, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Meals, D.M.; Spooner, J.; Dressing, S.A.; Harcum, J.B. Statistical Analysis for Monotonic Trends; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency by Tetra Tech, Inc.: Fairfax, VA, USA, 2011.

- Hirsch, R.M.; Slack, J.R.; Smith, R.A. Techniques of Trend Analysis for Monthly Water Quality Data. Water Resour. Res. 1982, 18, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, A.I. Kendall: Kendall Rank Correlation and Mann-Kendall Trend Test. R Package Version 2.2.1. 2022. Available online: https://CRAN.R-Project.Org/package=Kendall (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Zimmer, M.A.; Kaiser, K.E.; Blaszczak, J.R.; Zipper, S.C.; Hammond, J.C.; Fritz, K.M.; Costigan, K.H.; Hosen, J.; Godsey, S.E.; Allen, G.H.; et al. Zero or Not? Causes and Consequences of Zero-flow Stream Gage Readings. WIREs Water 2020, 7, e1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costigan, K.H.; Daniels, M.D.; Dodds, W.K. Fundamental Spatial and Temporal Disconnections in the Hydrology of an Intermittent Prairie Headwater Network. J. Hydrol. 2015, 522, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT). National Inventory of Dams; U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT): Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). State Regulated Dams; Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ): Austin, TX, USA, 2021.

- Elnashar, A.; Wang, L.; Wu, B.; Zhu, W.; Zeng, H. Synthesis of Global Actual Evapotranspiration from 1982 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 447–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.J.; Regan, R.S.; Haynes, J.V.; Read, A.L.; Henson, W.R.; Stewart, J.S.; Brandt, J.T.; Niswonger, R.G. Irrigation Water Use Reanalysis for the 2000-20 Period by HUC12, Month, and Year for the Conterminous United States; U.S. Geological Survey Data Release: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2023.

- Dewitz, J. U.S. Geological Survey National Land Cover Database (NLCD) 2019 Land Cover Science Product; version 2.0; U.S. Geological Survey Data Release: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Asrar, G.R. A Global Seamless 1 Km Resolution Daily Land Surface Temperature Dataset (2003–2020). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 14, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISM Climate Group; Oregon State University. 30-Year Normal Precipitation: Monthly 2014. Available online: https://prism.oregonstate.edu (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Soil Survey Geographic (SSURGO) Database for CONUS. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/resources/data-and-reports/soil-survey-geographic-database-ssurgo (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Hongtao, J.; Huanfeng, S.; Xinghua, L.; Lili, L. The 43-Year (1978–2020) Global 9km Remotely Sensed Soil Moisture Product 2022; PANGAEA: Bremen, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zowam, F.J.; Milewski, A.M. Groundwater Level Prediction Using Machine Learning and Geostatistical Interpolation Models. Water 2024, 16, 2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Geological Survey. 1 Arc-Second Digital Elevation Models (DEMs)—USGS National Map 3DEP Downloadable Data Collection; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2022.

- Davis, J.C. Statistics and Data Analysis in Geology, 3rd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maindonald, J.; Braun, W.J. Data Analysis and Graphics Using R—An Example-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-0-511-71286-9. [Google Scholar]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, UA, 2002; ISBN 0-387-95457-0. [Google Scholar]

- Lever, J.; Krzywinski, M.; Altman, N. Principal Component Analysis. Nat. Methods 2017, 14, 641–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, E.E. Climatic Controls on Diffuse Groundwater Recharge in Semiarid Environments of the Southwestern United States. Water Resour. Res. 2005, 41, W04012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehler, R.; Li, J.; Reager, J.; Ye, H. Investigating Relationship Between Soil Moisture and Precipitation Globally Using Remote Sensing Observations. J. Contemp. Water Res. Educ. 2019, 168, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakir, Y.; Bouimouass, H.; Constantz, J. Seasonality in Intermittent Streamflow Losses Beneath a Semiarid Mediterranean Wadi. Water Resour. Res. 2021, 57, e2021WR029743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Stein, M.L.; Wang, J.; Kotamarthi, V.R.; Moyer, E.J. Changes in Spatiotemporal Precipitation Patterns in Changing Climate Conditions. J. Clim. 2016, 29, 8355–8376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasko, C.; Nathan, R.; Stein, L.; O’Shea, D. Evidence of Shorter More Extreme Rainfalls and Increased Flood Variability under Climate Change. J. Hydrol. 2021, 603, 126994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shumilova, O.; Zak, D.; Datry, T.; Schiller, D.; Corti, R.; Foulquier, A.; Obrador, B.; Tockner, K.; Allan, D.C.; Altermatt, F.; et al. Simulating Rewetting Events in Intermittent Rivers and Ephemeral Streams: A Global Analysis of Leached Nutrients and Organic Matter. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 1591–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Data Description | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Contributing Drainage Area | USGS NWIS dataset contributing drainage area is reported in sq. miles. A minority of stream gages lacked this metric, and USGS-designated watershed areas (HUC 10) were used as a substitute [35]. | 30 m |

| Dams* | USDOT National Inventory of Dams dataset. The state of Texas was supplemented with an inventory of state-regulated dams (TCEQ). Dam counts were aggregated for each gage sub-basin (HUC 8) [46,47]. | NA |

| Elevation | USGS-derived gage elevation (ft), from USGS NWIS dataset. Values were supplemented by elevation from USGS 1-arc second DEM [35]. | 30 m |

| Evapotranspiration (ET) | Multi-product and satellite-aggregated global ET dataset. ET was averaged monthly from 2010 to 2019, with average ET calculated for each gage sub-basin (HUC 8) [48]. | 0.1° |

| Irrigated Area* | Landsat-based irrigation dataset (LANID) for CONUS (2018–2020). Percent irrigated area was aggregated for each gage sub-basin (HUC 8) [49]. | 30 m |

| Land Cover | NLCD MRLC land cover classification for CONUS (2021). Dominant land cover type (percentage of total area) within gage sub-basin (HUC 8) was extracted [50]. | 30 m |

| Maximum Land Surface Temperature (LST) | NASA MODIS (Terra/Aqua)-generated dataset. LST averaged monthly from 2010 to 2019, with units converted to °F. Maximum LST within each gage sub-basin (HUC 8) was extracted [51]. | 0.1° |

| Precipitation* | PRISM-average monthly 30-year normal precipitation dataset (CONUS). Values were averaged across each gage sub-basin (HUC 8) [52]. | 800 m |

| Soil Hydrologic Group | U.S. Soil Hydrologic Group (SSURGO) water infiltration classification. Dominant soil hydrologic group (percentage of total area) within gage sub-basin (HUC 8) was extracted [53]. | 30 m |

| Soil Moisture (SM)* | Multi-product and satellite-generated dataset, downscaled by Zowam and Milewski (2024) [54,55]. SM was averaged monthly from 2010 to 2019, and further averaged across each gage sub-basin (HUC 8). | 0.1° |

| Slope | Average slope across each gage sub-basin (HUC 8), derived from USGS 1-arc second DEM [56]. | 30 m |

| DFA Predictive Accuracy | Jackknife Predictive Accuracy | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Group | Overall | ||

| Perennial Channels | 82.3% | 79.5% | 74.3% |

| Intermittent Channels | 77.8% | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Davidson, L.J.; Milewski, A.M. Ephemeral Channel Expansion: Predicting Shifts Toward Intermittency in Vulnerable Streams Across Semi-Arid CONUS. Water 2025, 17, 3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233445

Davidson LJ, Milewski AM. Ephemeral Channel Expansion: Predicting Shifts Toward Intermittency in Vulnerable Streams Across Semi-Arid CONUS. Water. 2025; 17(23):3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233445

Chicago/Turabian StyleDavidson, Lea J., and Adam M. Milewski. 2025. "Ephemeral Channel Expansion: Predicting Shifts Toward Intermittency in Vulnerable Streams Across Semi-Arid CONUS" Water 17, no. 23: 3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233445

APA StyleDavidson, L. J., & Milewski, A. M. (2025). Ephemeral Channel Expansion: Predicting Shifts Toward Intermittency in Vulnerable Streams Across Semi-Arid CONUS. Water, 17(23), 3445. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233445