Abstract

Sulfanilic acid (SA) is a representative sulfonated aromatic amine commonly found in industrial effluents, posing significant risks to both human health and the ecosystem. Efficient and cost-effective treatment of SA-containing wastewater is crucial for sustainable environmental management. This study investigates the performance of the photo-Fenton process in degrading SA-containing wastewater. Three process variables are selected to study their effects on percent total organic carbon (%TOC) removal and final pH (pHFinal): initial total organic carbon concentration (TOC0) (150–250 mg/L), Fe2+ concentration (15–85 mg/L), and H2O2 concentration (1000–1500 mg/L). A combination of response surface methodology (RSM) and Box-Behnken design (BBD) is applied to examine both the individual and interactive effects of these variables. A total of 15 experimental trials are conducted, with the center point repeated three times. The results indicate significant interaction effects between Fe2+ and H2O2 concentrations on %TOC removal, while the interaction between TOC0 and H2O2 concentration notably influences pHFinal. The optimal operating parameters to maximize %TOC removal within 45 min of operation are determined as a TOC0 of 54.2 mg/L, an Fe2+ catalyst concentration of 33.7 mg/L, and an H2O2 concentration of 1403 mg/L. Under these conditions, the predicted %TOC removal and pHFinal were 89.2% and 2.93, respectively, which confirmed through validation experiments. Additionally, a correlation between pHFinal, TOC0, and final TOC concentration (TOCFinal) is observed, leading to the development of a linear model capable of predicting TOCFinal based on TOC0 and within the experimental space. The latter finding facilitates online monitoring of the process progress.

1. Introduction

Sulfonated aromatic amines are common pollutants in pharmaceutical and textile industry wastewater effluent, posing significant threats to human health and the environment due to their toxic, allergenic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic properties [1,2,3]. Sulfanilic acid (SA, 4-aminobenzenesulfonic acid) is a typical sulfonated aromatic amine, serving as a common intermediate in industries related to dyes, optical brighteners, pesticides, and sulfonamide antibiotics [4,5,6,7]. Substantial quantities of SA are introduced into water bodies during production and application. In addition, its relatively high water-solubility poses a challenge for efficient removal [7]. Therefore, developing an effective method for remediating SA-contaminated wastewater is crucial for the sustainable development of the industrial sector.

Aerobic biological treatment is the most cost-effective and environmentally friendly process [8]. However, the high chemical stability and low permeability of SA through bacterial membranes make it biorecalcitrant. Adsorption is commonly applied to remediate water containing non-degradable compounds [8]. Activated carbon, a typical adsorbent for sulfonated aromatic amines, demonstrates low adsorption capacity for SA due to its high water-solubility [9]. Additionally, challenges related to activated carbon regeneration and the generation of secondary pollutants hinder its widespread application [8].

Currently, advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) have received considerable attention for their ability to degrade complex organic compounds while minimizing negative impacts on ecosystems and public health. The degradation of organic pollutants during AOPs primarily occurs through the formation of hydroxyl radicals (HO•) from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). As a strong oxidizing species, HO• radicals attack organic compounds non-selectively, transforming them into less harmful by-products such as water, carbon dioxide, and inorganic salts [2,10,11,12,13,14]. AOPs are promising technologies for treating persistent wastewater [15]. Various AOPs have been applied for the degradation of sulfonated aromatic amine compounds, including Fenton [16], Photo-Fenton [17,18], (Photo)Electro-Fenton [2], and Photocatalysis [19].

Research conducted by Khankhasaeva et al. (2020) demonstrated that heterogeneous catalytic photo-oxidation achieved a 100% conversion rate for sulfonated aromatic amine wastewater [17]. However, the total organic carbon (TOC) removal was limited to 52.3%, indicating relatively low mineralization efficiency [17]. Another study applied the Electro/Photoelectro-Fenton process to SA wastewater [2], achieving 95–98% TOC removal. However, the system complexity and its high maintenance demand due to the frequent electrode passivation, limits its real-world applicability. Limited research has been conducted on SA degradation using AOPs. Among them, the Fenton reaction is one of the most extensively studied. The Fenton reaction is initiated by ferrous ion (Fe2+) and H2O2, generating HO• radicals and ferric ion (Fe3+). When pH < 3, this process becomes autocatalytic due to the regeneration of Fe2+ from Fe3+ through its reaction with H2O2, known as the Fenton-like reaction, outlined below [20]:

It is important to note that the Fenton-like reaction is significantly slower than the Fenton reaction, leading to the accumulation of Fe3+ species and limiting the overall reaction. Additionally, the produced hydroperoxyl radicals () exhibit lower oxidation power toward organic pollutants [21]. This obstacle can be addressed by introducing Ultraviolet (UV) radiation, which stimulates the reduction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ while simultaneously generating additional HO• radicals, as described below [21]:

Moreover, UV can decompose H2O2 through direct photolysis, as described in equation below, contributing to the formation of HO• radicals [13,22]:

where h and represent Planck’s constant and the light frequency, respectively. In comparison, the photo-Fenton process can operate with a lower concentration of Fe salts, reducing the amount of toxic metal released into the water and minimizing Fe sludge production. Additionally, the shorter degradation time enhances the process’s feasibility in terms of energy demand. The primary limitation of the photo-Fenton process is its sensitivity to pH, with an optimal range of 2.8–3.5 [15,23]. However, the acidic nature of SA aqueous solutions, with a natural pH of approximately 3 in the studied range (50–250 mg/L), compensates for the need for pH adjustment, further simplifying the process.

The objective of this research is to investigate the feasibility of the photo-Fenton process for degrading SA-containing wastewater without pH adjustment. The effects of various process variables, including initial TOC concentration (TOC0) (mg/L), Fe2+ concentration (mg/L), and H2O2 concentration (mg/L), on percentage of TOC removal (%TOC) and final pH (pHFinal) are examined. The optimum operating conditions for maximizing %TOC removal within the studied space are determined. Furthermore, a statistical expression is proposed to predict the final TOC concentration (TOCFinal) based on pHFinal and TOC0 within the experimental space. A combination of response surface methodology (RSM) and a Box–Behnken design (BBD) is employed to develop the statistical model, optimize operating conditions, and perform statistical analysis, which is achieved using Design-Expert software (Stat-Ease, Version 22.0.1).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Analytical-grade iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4·7H2O, 99%+, Sigma-Aldrich, Oakville, ON, Canada), TOC standard solution, (1000 µg/mL, Specpure, Thermo Scientific Chemicals, Barrington, IL, USA), pH buffer kit (Ward’s Science, Rochester, NY, USA), H2O2 (30% stabilized, ACS, VWR Chemicals BDH, Rouses Point, NY, USA), and reagent-grade SA (98%+, Thermo Scientific Chemicals, Mississauga, ON, Canada) were obtained from VWR Canada. For pH adjustments, sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 99%, Anachemia, Radnor, PA, USA) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 97%+, VWR Chemicals BDH, Mississauga, ON, Canada) were purchased from VWR Canada. The sample filtration is performed through a 0.45-micron non-sterile PVDF hydrophilic syringe filter (SF-PVDF-4513-S, Globe Scientific, Mahwah, NJ, USA). Phosphoric acid (H3PO4, ACS reagent, ≥85 wt%, JT Baker Chemicals, Phillipsburg, NJ, USA) was diluted in distilled water to prepare a 21% solution by volume. This solution is sparged into a sample to remove inorganic carbon (IC) and purgeable organic carbon (POC) before TOC analysis.

2.2. Preparation of Synthetic SA-Contained Wastewater

The concentration of SA in wastewater can vary considerably across different contaminated sources. Additionally, real process effluents exhibit varying concentrations of SA over time due to process disturbances, production fluctuations, and seasonal changes, even when an average concentration is observed. Therefore, the robustness of the model within a reasonable concentration range is important. Preliminary experiments have shown that the initial SA concentration plays a significant role in the overall degradation process, which has also been reported and examined as a key operational parameter in previous AOP studies [2,7,9,24]. In this study, the selected SA concentration levels are 50, 150, and 250 mg/L in terms of TOC concentration. This range was chosen to simulate typical SA-containing wastewater [1,7,8,25,26]. SA-containing wastewater was synthesized on-site by dissolving the proper amount of SA in distilled water. The TOC of the synthesized wastewater was confirmed using a TOC analyzer, along with its pH.

2.3. Analytical Method

2.3.1. pH Measurement

The pH measurements in this experiment were conducted using a potentiometric pH meter (Model HQ2200, Hatch, London, ON, Canada). A three-point calibration was performed daily using pH 4, 7, and 10 buffer solutions to ensure measurement accuracy and quality.

2.3.2. TOC Analysis

The degradation level of the SA solution was assessed through %TOC removal. The TOC content of all samples was determined using a combustion-type TOC analyzer (Model Apollo 9000, Teledyne Tekmar, Mason, OH, USA) operated under the direct method. In this method, IC is removed by adding 21% (v/v) H3PO4 to the sample, after which the acidified sample is purged with purified gas to eliminate dissolved inorganic carbon. The remaining organic carbon is quantified by oxidizing the purged sample in a high-temperature combustion furnace using Grade 4.5 oxygen. The resulting oxidized gases are transported by a carrier gas (O2, Grade 4.5) through a condenser and a semi-permeable Nafion tube to remove water vapor. The dehydrated gas is then passed through a corrosive scrubber to remove any halides. Finally, the carbon dioxide (CO2) produced during oxidation is detected by a nondispersive infrared (NDIR) detector. The NDIR detector measures the CO2 concentration, and the results are converted into TOC readings, providing an accurate evaluation of the organic carbon content in the sample with a range of 4–25,000 mgC/L. The %TOC removal for each trial was calculated using the following equation:

where TOC0 and TOCt represent the initial TOC concentration and TOC concentration at any time interval that is tested.

2.4. Design of Experiments and Analysis of Data

The RSM combined with a BBD was used to statistically evaluate the effects of process variables on the %TOC removal and pH change. Moreover, the potential of using TOC0 concentration and pHFinal as an indicator of final TOC content is investigated. The required number of experiments using BBD is estimated as follow [27]:

where N is the total number of experiments, k represents the number of factors and cp denotes the number of central points. The independent variables and their studied levels are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Independent variables along with their corresponding symbol, coded, and actual range utilized in BBD.

In total, 15 trials were designed with the central point repeated 3 times. The details of each experiment are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

BBD for three-factor three-level experiments alongside the observed and predicted %TOC removal and pHFinal for each run. x1, x2, and x3 are TOC0, Fe2+, and H2O2 concentrations, respectively.

The recorded data on %TOC removal and pHFinal with respect to the process variables at 45 min of reaction time were fitted into a second-order model given by the following equation:

where Y represents the predicted response, n is the number of variables, and e is the residual term, indicating the deviation between the predicted and actual values. b0, bi, bii, and bij are the intercept regression coefficient, linear regression coefficient, quadratic regression coefficient, and interaction regression coefficient, respectively. The independent variables are represented by xi and xj. The coefficients are determined using the least squares method, which minimizes the sum of squared differences between the observed and predicted values. Design-Expert (Stat-Ease, Version 22.0.1) was used in the design of the experiment (DOE) to create a model, perform Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), and optimize the operating parameters.

2.5. Experimental Setup and Procedure

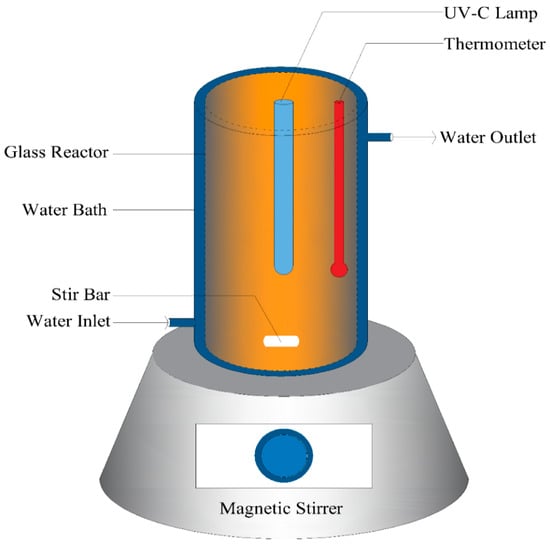

The structure of the photo-Fenton experimental setup is illustrated in Figure 1. The lab-scale batch photoreactor consists of a cylindrical glass beaker with an effective volume of 2000 mL. A germicidal lamp (Model PLS9W/TUV, LSE Lighting, Southampton, PA, USA) with a peak wavelength of 254 nm is positioned at the center of the photoreactor to ensure a homogeneous mixture. The same lamp was used within a two-week period, and any potential changes in the lamp’s intensity or wavelength over this period were considered negligible. The specifications of the lamp are listed in Table 3. The photoreactor is submerged in an isothermal water bath to maintain a temperature of 25 °C during the reaction, with the reaction temperature monitored using a thermometer. Adequate agitation is provided by a magnetic stirrer to ensure uniform mixing. The entire setup is wrapped in aluminum foil to enhance UVC irradiation and minimize external disturbances. The photoreactor lid contained several ventilation holes to release any gas formed during the reaction, and the entire setup was placed under a fume hood. The stirrer geometry, rotational speed, and lamp positioning were not included as variables in this study and were kept constant across all experiments to ensure controlled operating conditions. Given the small scale of the laboratory setup, the system was assumed to behave as an ideal homogeneous batch photoreactor, with no significant mass transfer limitations arising from mixing or other fixed parameters. Therefore, the effects of the key process variables, including TOC0, Fe2+, and H2O2 concentrations, were investigated, as these were identified from the literature and preliminary experiments as the most influential factors for evaluating the feasibility of the proposed process [2,16,17,28].

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of bench scale batch photo-Fenton System.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the UV-C lamp.

In each experiment listed in Table 2, 2 L of SA solution was prepared by dissolving the required amount of solid SA into distilled water. The prepared solution was tested for its TOC content and pH to confirm the desired quality of the stock solution. The solution was then loaded into the reactor, and the submerged UV lamp was activated and allowed to warm up for 30 min.

To confirm the necessity of the synergistic effect of UV/Fe2+/H2O2 in degrading SA, several preliminary experiments were conducted as listed in Table 4. These experiments consist of different combinations of experimental conditions, including UV irradiation alone, UV/H2O2, Fenton (Fe2+/H2O2) and photo-Fenton process (UV/Fe2+/H2O2). The result indicated that UV irradiation alone or in combination with H2O2 was insufficient for degrading the wastewater, as the TOC removal was negligible. In contrast, the Fenton and photo-Fenton processes achieved TOC removals of 18.3% and 78.8%, respectively, demonstrating the significant enhancement of the Fenton process when combined with UV irradiation. These results highlight the necessity of the combined UV/Fe2+/H2O2 system to achieve efficient SA degradation.

Table 4.

Summary of %TOC removal from preliminary experiments along with their conditions, TOC0, Fe2+, and H2O2 concentrations.

To initiate the photo-Fenton experiments, the corresponding dosages of Fe2+ catalyst and H2O2 were added to the photoreactor after the warm-up period. The preliminary estimation of H2O2 concentration (mg/L) range was calculated based on the stoichiometric ratio, under the fundamental assumption of complete SA mineralization, as described in equation below:

The stoichiometric ratio of 16 determined in this study falls within the range of 15–18 reported in previous studies involving similar pollutants [16,17,28]. The preliminary estimation of H2O2 dosage was further adjusted with preliminary experiments, and concentrations of 500, 1000, and 1500 mg/L were selected for subsequent tests.

The experimental Fe2+ concentration range, 15–85 mg/L, was selected as based on previous studies [16,28,29,30] and validated through preliminary experiments. Subsequently, the corresponding amounts of FeSO4·7H2O were calculated according to the molar equivalent of Fe2+ required. To minimize the risk of catalyst overdosing, in addition to the Fe2+ concentrations, their corresponding Fe2+/TOC0 ratios reported in the literature were calculated and presented in Table 5. These ratios were also considered in determining the Fe2+ concentration range used in this study. It is noteworthy that two relatively high values reported in the open literature correspond to Fe2+/TOC0 ratios of 14.2 and 7.75 [28,29]. This discrepancy arises because Pariente et al. (2008) employed a heterogeneous catalyst [28], while Baran et al. (2009) performed photocatalysis in the absence of H2O2 [29]; neither study investigated the photo-Fenton process as applied in the present work.

Table 5.

Summary of Fe2+ concentrations and Fe2+/TOC0 ratios reported in the literature and the present study.

Based on the results of preliminary experiments, samples were collected at 45, 60, 90, and 120 min of reaction time. Each sample was immediately tested for its pH, followed by quenching with 5 N NaOH to adjust the pH above 11. The quenching process ensures that the reaction is terminated, and the iron content is sufficiently precipitated. The quenched samples were then filtered through a 0.45-micron non-sterile PVDF hydrophilic syringe filter. The filtered samples were subjected to TOC analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Data-Driven Prediction Model and ANOVA

One of the main objectives of this research is to predict the %TOC removal and pHFinal in response to different process variables, in the experimental domain. Therefore, %TOC removal (Y1) and pHFinal (Y2) were selected as the two key response variables, with respect to three process variables: TOC0 concentration (x1), Fe2+ concentration (x2), and H2O2 concentration (x3). The data collected at 45 min from each trial were fitted into quadratic models, which are presented in equations below:

The 45 min interval was selected for modeling because this reaction time demonstrated the highest energy efficiency, as discussed later in this section.

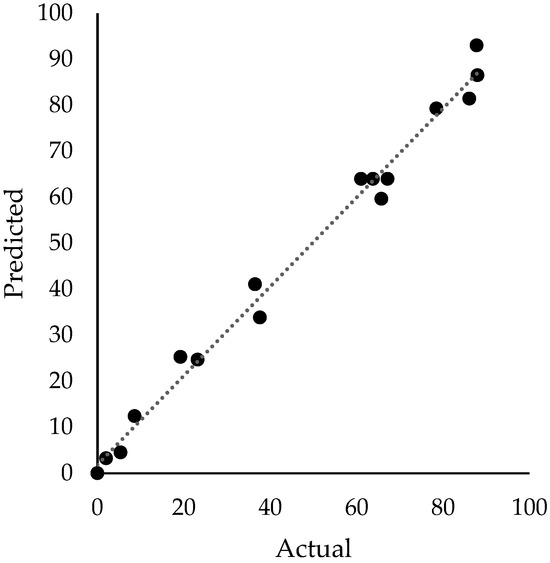

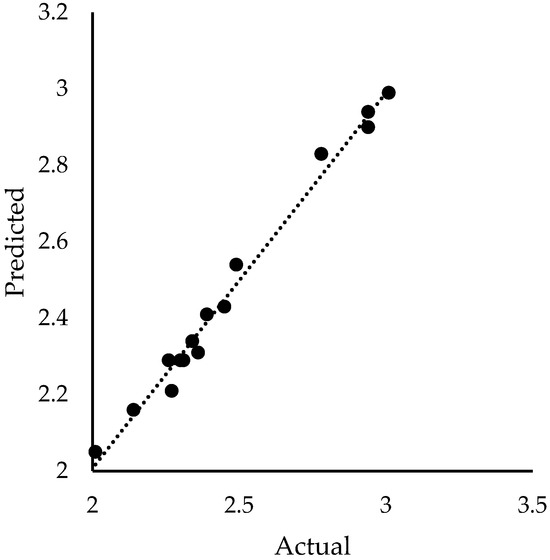

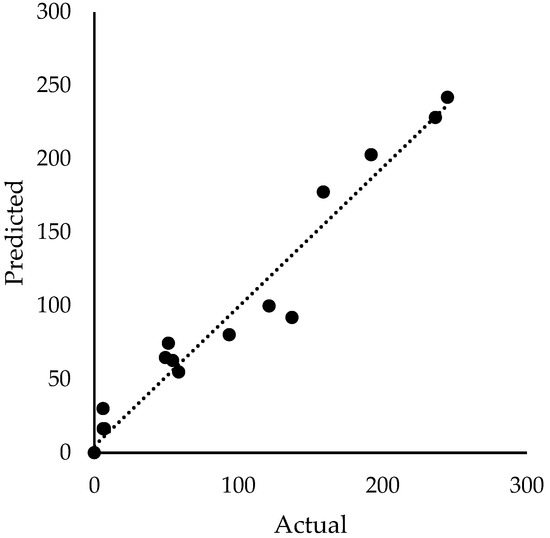

All independent variables are represented by their coded value instead of the actual value to diminish the impact of the scale on the statistical model. The quality of the models can be visualized in Figure 2 and Figure 3 for %TOC removal and pHFinal response, respectively. The predicted values from the model were plotted against the corresponding experimentally determined values. The close alignment of data points with the 45-degree line indicates the precision and consistency of the model in predicting process responses.

Figure 2.

Comparison of %TOC removal from experimental data and predicted values by the model.

Figure 3.

Comparison of pHFinal from experimental data and predicted values by the model.

The selection of 45 min operation time for the process was based on the calculated energy efficiency ratio (%/min) at different reaction times. This ratio, defined as the %TOC removal per unit of irradiation time (min), is shown in the equation below:

The energy efficiency at different time intervals is presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

The energy efficiency ratio after 45, 60, 90, and 120 min reaction time.

In most trials, energy efficiency ratio at 45 min outperformed other time intervals, indicating that 45 min is the optimal operating time. Furthermore, solving the optimization model at 45 min resulted in a %TOC removal around 85.3%, demonstrating the effectiveness of SA mineralization within this time frame. In cases where higher %TOC removal is required, the operation time can be extended; however, this comes with a trade-off in cost-effectiveness due to reduced energy efficiency at longer durations.

ANOVA was applied to evaluate the model’s effectiveness. The ANOVA results for %TOC removal and pHFinal response models are presented in Table 7 and Table 8, respectively. The R2 values of the quadratic models for %TOC removal and pHFinal response are 0.984 and 0.987, respectively, demonstrating the effectiveness of the second-order models in explaining most data points. The small differences (<0.2) between predicted and adjusted R2 for each expression highlight the model’s accuracy and consistency in predicting responses within the experimental range. The significance of different parameters is represented by the p-value, where a p-value < 0.05 indicates statistical significance, and a p-value > 0.05 is considered insignificant. It was observed that TOC0, Fe2+ and H2O2 concentrations are statistically significant to pHFinal while only TOC0 and H2O2 concentrations were significant to %TOC removal.

Table 7.

ANOVA results for the developed second-order model predicting %TOC removal in the photo-Fenton process for the degradation of SA.

Table 8.

ANOVA results for the developed second-order model predicting final pH value in the photo-Fenton process for the degradation of SA.

3.2. Interactive Effects of Fe2+ and H2O2 on %TOC Removal and pHFinal

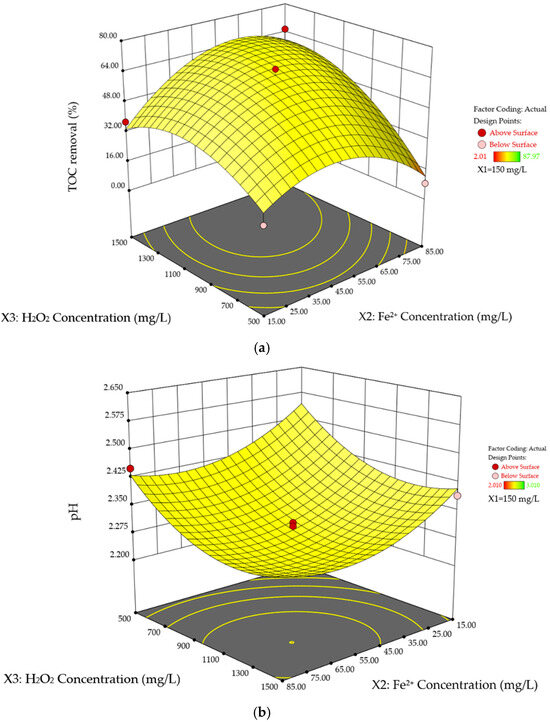

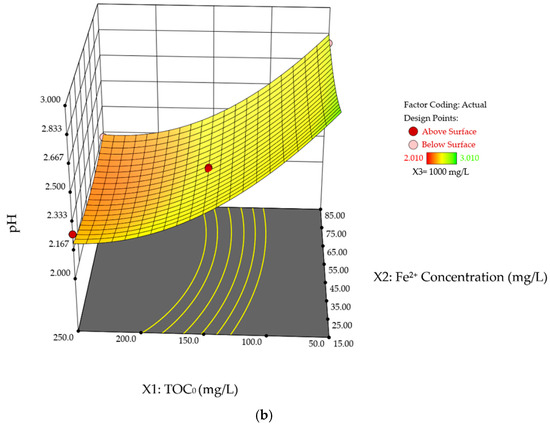

Three-dimensional response surface plots of the process variables were generated based on the mathematical model across the entire experimental space. These plots are generated by holding one process variable constant while varying the other two, allowing for clearer visualization and a better understanding of how the process behaves across the experimental range.

Figure 4a and b illustrates the interaction effects of Fe2+ and H2O2 concentrations on %TOC removal and pHFinal, with the TOC0 held constant at its mid-range value of 150 mg/L. Figure 4a demonstrates a curvature trend in %TOC removal as both Fe2+ and H2O2 concentrations increase. Specifically, increasing the H2O2 concentration from 500 to 1500 mg/L across the full range of Fe2+ concentrations result in a rising %TOC removal, peaking near the mid-range value of 1000 mg/L. Beyond this point, further increases in H2O2 concentration leads to a decline in removal efficiency. This behavior is primarily attributed to the scavenging effect of HO• radicals at high H2O2 concentrations [31,32,33]. At lower H2O2 concentrations (500–1100 mg/L), the added H2O2 reacts under UV irradiation and in the presence of Fe2+ to generate HO• radicals, which effectively oxidize and mineralize SA, thereby improving %TOC removal. However, at elevated H2O2 levels, excess H2O2 begins to scavenge the HO• radicals, as shown in Equation (12), resulting in the formation of instead. These radicals possess a lower oxidation-reduction potential than HO• radicals, thus reducing the overall degradation efficiency [34].

where RH represents the organic pollutant and is the organic radical produced from its reaction with . A similar trend is observed with increasing Fe2+ dosage. For instance, when H2O2 concentration and TOC0 are fixed at their mid-range values, %TOC removal increases from 40.0% to 49.0% as Fe2+ concentration rises from 15 to 49 mg/L. However, beyond 49 mg/L, removal decreases to 41.0%. As noted earlier, Fe2+ catalyzes the reaction via Equations (2) and (3). The rise in Fe2+ concentration from 15 to 49 mg/L enhances catalytic activity and HO• radical production, resulting in higher TOC removal. The distinctive behavior of the system after 49 mg/L of Fe2+ can be explained by two factors. One plausible explanation is that excessive iron leads to the scavenging effect of HO• radicals by Fe2+ ions, as described below [35,36,37]:

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional response surface plots of SA degradation in photo-Fenton process. Interaction effects of H2O2 concentration and Fe2+ concentration on (a) %TOC removal, and (b) pHFinal while the TOC0 is held at its mid-range values (150 mg/L).

At high Fe2+ concentrations, excess Fe2+ ions scavenge HO• radicals, thereby reducing the number of HO• radicals available for the degradation of organic compounds. Similar scavenging effects have been reported in other studies [38,39,40,41]. Another contributing factor is that surplus Fe2+ ions form excess free radicals and Fe3+ ions, leading to a higher concentration of metal complexes due to complexation reactions [42]. These metal complexes contribute to a more persistent color change, will be explained in the next section, ultimately reducing the permeability of UV light and limiting its efficiency in generating HO• radicals. Moreover, the complexes also hinder the regeneration of Fe2+ in Equation (3), resulting in lower catalytic activity and fewer HO• radicals produced [42].

Figure 4b demonstrates a reversed behavior of pHFinal compared to %TOC removal, where increases in Fe2+ and H2O2 concentrations slightly decrease pHFinal, followed by a slight increase, showing an overall concave-down trend. This pattern can be attributed to the formation of acidic intermediates and final products, primarily carboxylic acids and H2SO4, during the decomposition of SA. Initially, enhanced degradation of SA at higher catalyst and H2O2 concentrations results in the generation of more H2SO4 and carboxylic acids. The slight increase in pH observed in Figure 4b, upon the introduction of excess Fe2+ and H2O2, occurs due to the scavenging effect of these reagents. This scavenging reduces the amount of HO• radicals formed, thereby limiting degradation and lowering the concentration of acidic compounds in the medium. Although it has been suggested that the sulfate heptahydrate catalyst used in this experiment may affect pH, its influence was found to be negligible based on experimental observations. The p-value of 0.0342 in Table 7 indicates that the interaction between Fe2+ and H2O2 concentrations significantly impacts %TOC removal. In contrast, their interaction is statistically insignificant for pHFinal, with a p-value of 0.935.

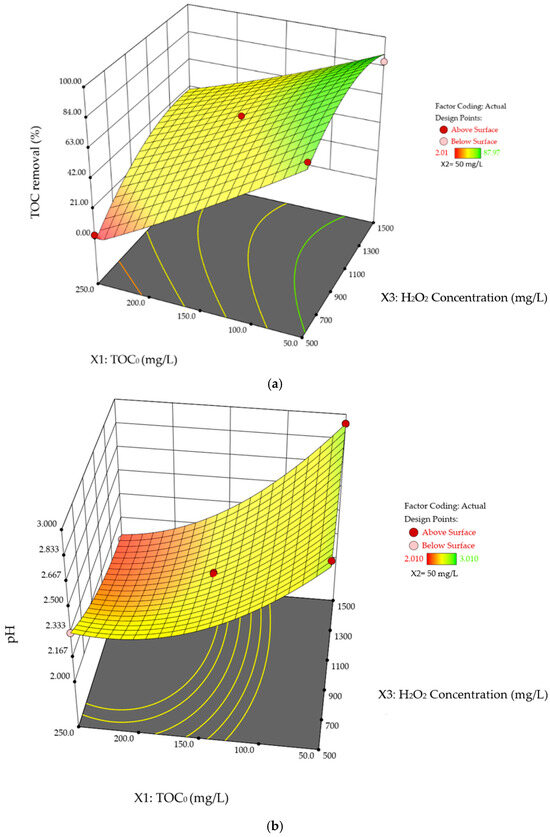

3.3. Interactive Effects of TOC0 and H2O2 on %TOC Removal and pHFinal

Figure 5a,b demonstrates the interaction effects of TOC0 concentration and H2O2 concentration on %TOC removal and pHFinal, with Fe2+ dosage maintained at its mid-range value (50 mg/L). Figure 5a and b shows that, regardless of the H2O2 concentration, increasing TOC0 leads to a significant reduction in both %TOC removal and pHFinal. At the lowest H2O2 dosage of 500 mg/L, %TOC removal drops from 86.0% to 5.00% as the TOC0 concentration increases from 50 to 250 mg/L. This trend is attributed to the increased demand for HO• radicals and the extended reaction time required to mineralize higher concentrations of SA. Correspondingly, it is observed that extending the experiment duration to 120 min enables most trials to achieve over 90% TOC removal, as shown in Table 9.

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional response surface plots of SA degradation in photo-Fenton process. Interaction effects of TOC0 concentration and H2O2 concentration on (a) %TOC removal, and (b) pHFinal while the Fe2+ is held at its mid-range values (50 mg/L).

Table 9.

TOC0 concentration, %TOC removal, and pHFinal at 45 and 120 min reaction time.

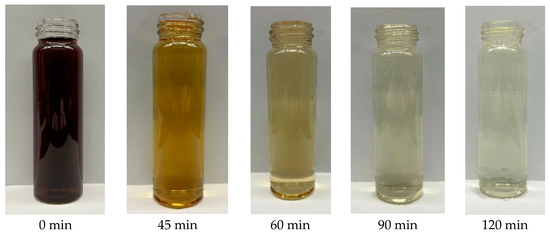

TOC0 reflects the concentration of SA. At higher SA levels, more UV-C light is absorbed by the dissolved SA, limiting the UV-C available to be absorbed by H2O2. This leads to fewer HO• radicals being generated, reducing the overall process efficiency. Notably, during the experiments, a visible color change from dark black to brown and eventually to transparent was observed, primarily associated with TOC0. This color change is demonstrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Color transition captured during the experiment under the following conditions: TOC0 concentration of 150 mg/L, Fe2+ concentration of 15 mg/L, and H2O2 concentration of 1500 mg/L.

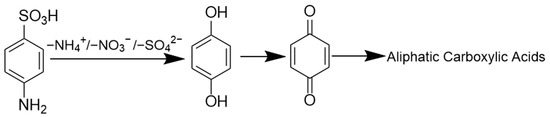

According to Mijangos et al. (2006), this change is linked to the formation of dihydroxylated rings, which produce color-intense compounds such as benzoquinone [42]. Reactions involving these rings and their quinones further contribute to the color, even at low concentrations [42]. Additionally, colored metal complexes can form as Fe3+ ions interact with benzene derivatives, intensifying the observed color [42]. The extent of color change is largely influenced by the initial pollutant concentration, with minimal impact from the oxidant and catalyst [42]. The color, thus, can serve as an indicator of the oxidation level, as color-intense intermediates are progressively degraded into less colored compounds as the reactions proceed [42]. These mechanisms are consistent with the commonly reported intermediates in the degradation of SA through AOP-based methods, including hydroquinone, p-benzoquinone, and aliphatic carboxylic acids, along with their corresponding degradation pathways [2,16,19,28]. Although these color correlations are preliminary, they provide valuable insights that can serve as a basis for the proposed process mechanism, which can be further studied, analyzed, and evaluated in future research. The presence of these intermediates depends on the degree of conversion. According to the general pathway proposed in the literature [2,16,43,44], HO• radicals initially attack the benzenic ring of SA, leading to the release of , , and , and resulting in dihydroxylation of the aromatic ring to form hydroquinone. Hydroquinone is subsequently oxidized to p-benzoquinone, which then undergoes ring cleavage to produce aliphatic carboxylic acids. These aliphatic acids represent the ultimate organic intermediates that are further oxidized to inorganic end products, primarily CO2. The proposed degradation pathway is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Proposed conversion pathway of sulfanilic acid (SA).

In this study, it is observed that the duration of the dark phase is mainly influenced by the initial SA concentration. Higher TOC0 leads to a longer dark phase (~5–25 min), decreasing UV light efficiency due to reduced transparency. In contrast, lower TOC0 shows a shorter dark phase (<30 s), enabling more efficient utilization of UV light in producing HO• radicals. Notably, even at the highest TOC0, a 27.0% removal is achieved, demonstrating the feasibility of the photo-Fenton process for SA degradation. At the minimum TOC0 (50 mg/L), increasing H2O2 results in a uniform curvature in %TOC removal, with values of 86.1% and 86.4% at the lowest and highest H2O2 dosages, respectively. Conversely, at the highest TOC0 (250 mg/L), %TOC removal plateaus as H2O2 increases. This may be due to relative excess H2O2 at low TOC0 concentration, leading to scavenging effects discussed in Section 3.2, while high TOC0 demands more oxidant to reach peak efficiency.

Similar pattern is observed in Figure 5b, where pH decreases across all H2O2 concentrations as TOC0 increases. At higher TOC0 loads, more SA is present, resulting in a lower initial pH, as shown in Table 9. As degradation progresses, the reduction in SA concentration leads to a further decrease in pH. This is attributed to the formation of acidic organic intermediates and inorganic final products, mainly carboxylic acids and H2SO4, during SA degradation. During the experiments, a rapid pH drop is observed at the beginning, followed by a gradual rise once a certain level of %TOC removal is reached. Eventually, the pH stabilizes at a value higher than the initial pH. One possible explanation is that, as the reaction proceeds, most SA is first converted into more acidic organic intermediates, most likely benzenesulfonic acid as reported in [16,45]. These intermediates are then further broken down into less acidic organics as carboxylic acid [2,16], and inorganics such as CO2 and H2O, and partially into H2SO4, as suggested by Equation (8), as the solution approaches complete mineralization, the pH of the solution stabilize as the concentration of carboxylic acid decreases to zero. This behavior aligns with the observation that pH inversion typically occurs when TOC removal reaches 20.0–35.0%. In cases of high SA concentration (e.g., 250 mg/L) combined with relatively low H2O2 concentration (e.g., 500 mg/L), this inversion may not occur due to the continuous generation of acidic intermediates. Opposite to the trend observed in %TOC removal, Figure 5b shows that increasing H2O2 concentration results in an upward curvature in pHFinal. This is because the scavenging effect of H2O2 leads to variations in the amount of acidic intermediates and final products generated, as discussed previously in this section. The curvature is more pronounced at lower H2O2 concentrations, aligning with the trend observed in Figure 5a. According to Table 8, the interaction between TOC0 and H2O2 concentration significantly influences pHFinal, with a p-value of 0.037. In contrast, their interaction is statistically insignificant for %TOC removal, with a p-value of 0.058. Notably, the p-value presented in Table 7 indicates that TOC0 concentration, as an individual process variable, has the most significant impact on %TOC removal, with the lowest p-value of <0.0001. Similarly, TOC0 concentration and its second-order term are statistically significant for pHFinal shown in Table 8, with p-values of <0.0001 and 0.0013, respectively. This suggests a higher-order correlation between TOC0 and pHFinal.

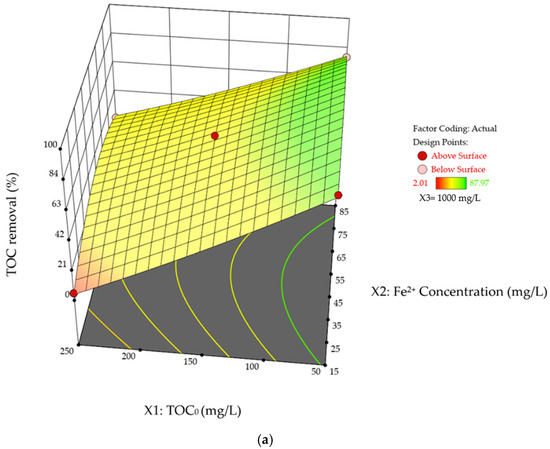

3.4. Interactive Effects of TOC0 and Fe2+ on %TOC Removal and pHFinal

Figure 8a and b presents the interaction effects of TOC0 concentration and Fe2+ dosage on %TOC removal and pHFinal, with the H2O2 concentration held at its mid-range value of 1000 mg/L. The curvature behavior observed is a result of the scavenging effect of excessive Fe2+ catalyst, as discussed in previous sections, which leads to a nonlinear variation in both %TOC removal and pHFinal with increasing Fe2+ concentration. Noteworthy that the curvature shown in Figure 8b exhibits a high degree of homogeneity: the difference in %TOC removal between the two extreme Fe2+ concentrations (15 mg/L and 85 mg/L) is very similar at both the lowest and highest TOC0 concentrations (50 mg/L and 250 mg/L), with values of 9.52% and 9.24%, respectively. This supports the earlier observation that the reduction in %TOC removal due to color change is primarily governed by TOC0 concentration rather than Fe2+ dosage. Based on Table 7 and Table 8, the interactive effect between TOC0 concentration and Fe2+ concentration is not significant for %TOC removal and pHFinal, with p-values of 0.096 and 0.433, respectively.

Figure 8.

Three-dimensional response surface plots of SA degradation in photo-Fenton process. Interaction effects of TOC0 concentration and Fe2+ concentration on (a) %TOC removal, and (b) pHFinal while the H2O2 is held at its mid-range values (1000 mg/L).

3.5. Potential Use of TOC0 and pHFinal as Indicators for TOCFinal

TOC is the primary parameter in this study, as it serves as a direct indicator of the degree of mineralization. However, due to the inherent limitations of TOC measurement techniques, real-time monitoring is not feasible [46]. This constraint poses a significant challenge for the practical implementation of the studied process, particularly in AOPs, where fluctuations in operational conditions and external disturbances can significantly influence process performance. The findings presented in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3 indicate a strong correlation between pH and TOC concentration within the studied experimental range. This correlation suggests the possibility of developing a statistical predictive model to estimate TOCFinal based on pHFinal and TOC0 concentration. Utilizing the collected experimental data, a linear regression model has been established to predict TOCFinal, as described in equation below:

Excel (Version 2108) was employed to develop the first order model applying least squares method. The R2 value of 0.943, as shown in Table 10, indicates a strong correlation pHFinal, TOC0, and TOCFinal. Additionally, the accuracy and consistency of this linear model are confirmed by the difference between the predicted and adjusted R2 values being less than 0.2. The p-values of TOC0 and are <0.0001 and 0.0005, respectively, indicating their statistical significance.

Table 10.

ANOVA results for the linear model predicting TOCFinal according to and .

The actual TOCFinal versus their anticipated values using Equation (14) were plotted, as shown in Figure 9. The consistency of data points around 45 line verified the accuracy and effectiveness of the model.

Figure 9.

The observed TOCFinal versus its predicted value from the linear model.

3.6. Optimization of Operating Conditions

In this study, the optimization objective is to maximize the %TOC removal by adjusting three process variables. Equation (9) is regarded as the objective function to maximize %TOC removal within the experimental range. The optimization solutions were generated using Design Expert (version 22.0.1) and based on the desirability criterion, the solution shown in Table 11 was selected. The forecasted values of %TOC removal and pHFinal under the proposed optimal conditions aligned with the results from the validation experiment, with a percent error of less than ± 5.00%. At the optimum conditions, the %TOC removal and pHFinal response were determined as 85.3 percent and 2.92, respectively, yielding a percent error of 4.39% and 0.057 for %TOC removal and pH, in comparison to the anticipated values.

Table 11.

Calculated optimum operation conditions to maximize the %TOC removal. Predicted and observed value for process response of %TOC removal and pHFinal along with process variables of TOC0 concentration in mg/L (x1), Fe2+ concentration in mg/L (x2), and H2O2 concentration in mg/L (x3).

The work done by Kalinski et al. (2014), which employed the UV/H2O2 process to degrade SA, reported an optimal H2O2-to-SA molar ratio of 122 as shown in Table 1 [47]. In comparison, the molar ratio identified in this study for optimum solution is 54.7, indicating a significantly lower H2O2 demand in the photo-Fenton process and suggesting improved cost-effectiveness. Additionally, the optimal Fe2+/TOC0 mass ratio determined in this study is compared with values reported in the literature listed in Table 12, falling within the documented range of 0.152–4.65 on the lower side. Considering that Khankhasaeva et al. (2020) applied a heterogeneous catalyst [17], the lower optimum Fe2+/TOC0 ratio observed in this study is reasonable since the Fe2+ catalyst is introduced in salt form to make a homogeneous system; in comparison, heterogeneous systems mass transfer is limited by factors such as particle size and porosity.

Table 12.

Summary of optimum Fe2+/TOC0 and H2O2/TOC0 ratios reported in the literature and the present study.

Intermediates are important indicators of the toxicity of the treated influent. As discussed in Section 3.3, various intermediates are formed throughout the degradation process, with their concentrations varying according to the extent of conversion. A study by El-Ghenymy et al. (2012) applying a Fenton-based process to SA demonstrated that, under optimal conditions, the concentrations of hydroquinone and p-benzoquinone peaked at approximately 5 and 3 min, respectively, and decreased to nearly zero after about 8 min with no significant change in the TOC of the solution [2]. Beyond this point, aliphatic carboxylic acids became the dominant intermediates, and their concentrations continued to increase until approximately 20% TOC removal was achieved [2]. This observation aligns with the color transition we observed between 5 and 25 min and the pH reversion occurring at TOC removals between 20 and 35%. Therefore, it is proposed that the predominant species present after achieving the optimum TOC removal (89.19%) are aliphatic carboxylic acids, which have been reported to exhibit lower aquatic toxicity toward Daphnia magna compared to SA, as summarized in Table 13.

Table 13.

Summary of EC50 toxicity for SA, oxalic acid and formic acid.

4. Conclusions

This study investigated the feasibility of the photo-Fenton process for degrading SA-rich wastewater without prior pH adjustment, with a primary focus on maximizing %TOC removal. A RSM approach, combined with the BBD, was employed to evaluate both the individual and interactive effects of TOC0 concentration, Fe2+ concentration, and H2O2 concentration on the process efficiency. The statistical model, developed using experimental data and validated using ANOVA, was utilized as an objective function to optimize process parameters with the aim of maximizing %TOC removal within the experimental space. The optimal conditions were identified as 54.2 mg/L for TOC0 concentration, 33.7 mg/L for Fe2+ concentration, and 1403 mg/L for H2O2 concentration, yielding a predicted %TOC removal of 89.2%. These conditions were confirmed through a validation experiment, demonstrating a variance of less than 5% between predicted and observed values. Compared to reported UV/H2O2 systems in the literature, the optimal parameters determined in this study require significantly lower H2O2 input, highlighting the improved cost-effectiveness of the photo-Fenton process. Additionally, a linear correlation model was developed within the experimental range to predict TOCFinal based on TOC0 concentration and pHFinal, which will be helpful toward the online monitoring of process progress.

The findings from this study confirm the effectiveness of the photo-Fenton process in remediating SA-contaminated wastewater and highlight its potential as a viable treatment or pre-treatment method for such industrial effluents. The next recommended step of this work is to evaluate the potential application of the photo-Fenton process as a pretreatment method to enhance the biodegradability of SA, particularly in terms of biochemical oxygen demand. Furthermore, the collection and analysis of gas emissions during larger-scale experiments are suggested to support the development of a mechanistic model. Finally, LC–MS or HPLC analyses of experimental samples are recommended for investigating the reaction mechanism, identification and toxicity assessment of intermediate compounds formed during the process, and evaluation of reaction rate constants.

Author Contributions

This article was a collaborative effort. The conceptualization was led by research supervisors M.M. and Z.P., while the extensive data analysis and experimentations, summarization, and literature comparison were carried out by C.C., guided by supervisors. C.C. took the lead in drafting the manuscript, with contributions and feedback from M.M. and Z.P. during critical revisions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Toronto Metropolitan University Graduate Scholarship, and Toronto Metropolitan University Faculty of Engineering and Architectural Science.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Acronyms | |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| AOPs | Advanced Oxidation Process |

| BBD | Box-Behnken Design |

| Corrected total SS | Corrected Total Sum of Squares |

| df | Degree of Freedom |

| DOE | Design of Experiments |

| IC | Inorganic Carbon |

| NDIR | Nondispersive Infrared |

| POC | Purgeable Organic Carbon |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| SA | Sulfanilic Acid |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| Symbols | |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| Fe2+ | Ferrous Iron |

| Fe3+ | Ferric Iron |

| h | Planck’s Constant |

| HO• | Hydroxyl Radical |

| Hydroperoxyl Radical | |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen Peroxide |

| RH | Undegraded Organic Pollutant |

| Organic Radical | |

| pHInitial | Initial pH |

| pHFinal | Final pH |

| TOC0 | Initial Total Organic Carbon Content (mg/L) |

| TOCFinal | Final Total Organic Carbon Content of Feed (mg/L) |

| x1 | Initial Total Organic Carbon Content (mg/L) |

| x2 | Ferrous Iron Concentration (mg/L) |

| x3 | Hydrogen Peroxide Concentration (mg/L) |

| Y1 | Predicted %TOC Removal |

| Y2 | Predicted Final pH |

| Light Frequency |

References

- El-Ghenymy, A.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Brillas, E.; El Begrani, M.S.; Abdelouahid, B.A. Optimization of the Electro-Fenton and Solar Photoelectro-Fenton Treatments of Sulfanilic Acid Solutions Using a Pre-Pilot Flow Plant by Response Surface Methodology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 221–222, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ghenymy, A.; Garrido, J.A.; Centellas, F.; Arias, C.; Cabot, P.L.; Rodríguez, R.M.; Brillas, E. Electro-Fenton and Photoelectro-Fenton Degradation of Sulfanilic Acid Using a Boron-Doped Diamond Anode and an Air Diffusion Cathode. J. Phys. Chem. A 2012, 116, 3404–3412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.-C.; Wang, K.-S.; Lin, I.-C.; Hsiao, T.-E.; Lin, Y.-N.; Tang, C.-T.; Chen, J.-C.; Chang, S.-H. Rapid Regeneration of Sulfanilic Acid-Sorbed Activated Carbon by Microwave with Persulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 193–194, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsing, P.; Tiwari, A.; Joshi, T.; Garg, S. Application of a Novel Bacterial Consortium for Mineralization of Sulphonated Aromatic Amines. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Ramírez, C.; Galíndez-Mayer, J.; Ruiz-Ordaz, N.; Ramos-Monroy, O.; Santoyo-Tepole, F.; Poggi-Varaldo, H. Steady-State Inhibition Model for the Biodegradation of Sulfonated Amines in a Packed Bed Reactor. New Biotechnol. 2015, 32, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, G.; Lu, H.; Jin, R.; Zhou, J. Degradation of 1-amino-4-bromoanthraquinone-2-sulfonic Acid Using Combined Airlift Bioreactor and TiO2-photocatalytic Ozonation. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2013, 88, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Li, T.; Su, Y.; Li, C.; Jin, X.; Ren, H. Removal of Sulfanilic Acid from Wastewater by Thermally Activated Persulfate Process: Oxidation Performance and Kinetic Modeling. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 94, 3208–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amrani, W.A.; Hanafiah, M.A.K.M.; Lim, P.-E. Influence of Hydrophilicity/Hydrophobicity on Adsorption/Desorption of Sulfanilic Acid Using Amine-Modified Silicas and Granular Activated Carbon. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 249, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Z.; Liu, Y. Treatment of High Salinity Sulfanilic Acid Wastewater by Bipolar Membrane Electrodialysis. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 281, 119842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreozzi, R.; Campanella, L.; Fraysse, B.; Garric, J.; Gonnella, A.; Lo Giudice, R.; Marotta, R.; Pinto, G.; Pollio, A. Effects of Advanced Oxidation Processes (AOPs) on the Toxicity of a Mixture of Pharmaceuticals. Water Sci. Technol. 2004, 50, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GilPavas, E.; Correa-Sánchez, S.; Acosta, D.A. Using Scrap Zero Valent Iron to Replace Dissolved Iron in the Fenton Process for Textile Wastewater Treatment: Optimization and Assessment of Toxicity and Biodegradability. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.; Wu, Q.-Y.; Tian, G.-P.; Hu, H.-Y. Effective Degradation of Methylisothiazolone Biocide Using Ozone: Kinetics, Mechanisms, and Decreases in Toxicity. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 1064–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M. Degradation and Mineralization of Organic Contaminants by Fenton and Photo-Fenton Processes: Review of Mechanisms and Effects of Organic and Inorganic Additives. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 2011, 15, 96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Eslami, A.; Massoudinejad, M.; Avazpour, M. Enhanced Degradation of Sulfamethoxazole Antibiotic from Aqueous Solution Using Mn-WO3/LED Photocatalytic Process: Kinetic, Mechanism, Degradation Pathway and Toxicity Reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 380, 122497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignatello, J.J.; Oliveros, E.; MacKay, A. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Organic Contaminant Destruction Based on the Fenton Reaction and Related Chemistry. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 36, 1–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khankhasaeva, S.T.; Dambueva, D.V.; Dashinamzhilova, E.T.; Gil, A.; Vicente, M.A.; Timofeeva, M.N. Fenton Degradation of Sulfanilamide in the Presence of Al, Fe-Pillared Clay: Catalytic Behavior and Identification of the Intermediates. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 293, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khankhasaeva, S.T.; Badmaeva, S.V. Removal of P-Aminobenzenesulfanilamide from Water Solutions by Catalytic Photo-Oxidation over Fe-Pillared Clay. Water Res. 2020, 185, 116212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanchai, K.; Pichon, R. Synthesis of Fe3O4@chitosan Beads for Degradation of Sulfanilamide Using Photo-Fenton Process. In Proceedings of the Second Materials Research Society of Thailand International Conference, Pattaya, Thailand, 10–12 July 2019; p. 130002. [Google Scholar]

- Ganiyu, S.O.; De Araújo, M.J.G.; De Araújo Costa, E.C.T.; Santos, J.E.L.; Dos Santos, E.V.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; Pergher, S.B.C. Design of Highly Efficient Porous Carbon Foam Cathode for Electro-Fenton Degradation of Antimicrobial Sulfanilamide. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 283, 119652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litter, M.I. Introduction to Photochemical Advanced Oxidation Processes for Water Treatment. In Environmental Photochemistry Part II; Boule, P., Bahnemann, D.W., Robertson, P.K.J., Eds.; The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry; Springer-Verlag: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 2M, pp. 325–366. ISBN 978-3-540-00269-7. [Google Scholar]

- Oturan, M.A.; Aaron, J.-J. Advanced Oxidation Processes in Water/Wastewater Treatment: Principles and Applications. A Review. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 44, 2577–2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, Z.; Dhib, R.; Mehrvar, M. Continuous UV/H2O2 Process: A Sustainable Wastewater Treatment Approach for Enhancing the Biodegradability of Aqueous PVA. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manna, M.; Sen, S. Advanced Oxidation Process: A Sustainable Technology for Treating Refractory Organic Compounds Present in Industrial Wastewater. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 25477–25505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Song, G.; Fu, W.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, Y. Removal of Sulfamethazine by a Flow-Fenton Reactor with H2O2 Supplied with a Two-Compartment Electrochemical Generator. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 301, 122038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Cheng, K.Y.; Ginige, M.P.; Kaksonen, A.H. Aerobic Degradation of Sulfanilic Acid Using Activated Sludge. Water Res. 2012, 46, 145–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, S.; Kumar, A.; Dhiman, P.; Mola, G.T.; Sharma, G.; Lai, C.W. Recent Advances in Photocatalytic Removal of Sulfonamide Pollutants from Waste Water by Semiconductor Heterojunctions: A Review. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 30, 101603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, M.A.; Santelli, R.E.; Oliveira, E.P.; Villar, L.S.; Escaleira, L.A. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) as a Tool for Optimization in Analytical Chemistry. Talanta 2008, 76, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pariente, M.; Martinez, F.; Melero, J.; Botas, J.; Velegraki, T.; Xekoukoulotakis, N.; Mantzavinos, D. Heterogeneous Photo-Fenton Oxidation of Benzoic Acid in Water: Effect of Operating Conditions, Reaction by-Products and Coupling with Biological Treatment. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2008, 85, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, W.; Adamek, E.; Sobczak, A.; Sochacka, J. The Comparison of Photocatalytic Activity of Fe-Salts, TiO2 and TiO2/FeCl3 during the Sulfanilamide Degradation Process. Catal. Commun. 2009, 10, 811–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, S.; Hussain, S.; Khan, H.; Arshad, M.; Khan, J.R.; Motheo, A.D.J. Integrated AI-Driven Optimization of Fenton Process for the Treatment of Antibiotic Sulfamethoxazole: Insights into Mechanistic Approach. Chemosphere 2024, 357, 141868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamad, D.; Mehrvar, M.; Dhib, R. Photochemical Kinetic Modeling of Degradation of Aqueous Polyvinyl Alcohol in a UV/H2O2 Photoreactor. J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 3283–3293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, N.T.; Mwazighe, F.M. The Various Effects of Hydrogen Phosphate and Bicarbonate in the Degradation of Some Pollutants in the UV/Chlorine and the UV/H2O2 Processes. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 57, 104646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Manna, P.; De Carluccio, M.; Iannece, P.; Vigliotta, G.; Proto, A.; Rizzo, L. Chelating Agents Supported Solar Photo-Fenton and Sunlight/H2O2 Processes for Pharmaceuticals Removal and Resistant Pathogens Inactivation in Quaternary Treatment for Urban Wastewater Reuse. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 452, 131235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimić, D.S.; Milenković, D.A.; Avdović, E.H.; Nakarada, Đ.J.; Dimitrić Marković, J.M.; Marković, Z.S. Advanced Oxidation Processes of Coumarins by Hydroperoxyl Radical: An Experimental and Theoretical Study, and Ecotoxicology Assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 424, 130331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, C.L.; Huang, Y.H.; Wang, C.C.; Chen, C.Y. Degradation of Azo Dyes Using Low Iron Concentration of Fenton and Fenton-like System. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panizza, M.; Cerisola, G. Electro-Fenton Degradation of Synthetic Dyes. Water Res. 2009, 43, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dong, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, D.; Meng, D. A Review on Fenton Process for Organic Wastewater Treatment Based on Optimization Perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 670, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.W.; Hwang, K.-Y. Effects of Reaction Conditions on the Oxidation Efficiency in the Fenton Process. Water Res. 2000, 34, 2786–2790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, J.H.; Waters, W.A. 511. The Oxidation of Aromatic Compounds by Means of the Free Hydroxyl Radical. J. Chem. Soc. Resumed 1949, 2427–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, C.; Kato, S. Oxidation of Alcohols by Fenton’s Reagent. Effect of Copper Ion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 4275–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, S.; Olabi, A. Effect of Fe2+ and Fe0 Applied Photo-Fenton Processes on Sludge Disintegration. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2021, 44, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijangos, F.; Varona, F.; Villota, N. Changes in Solution Color During Phenol Oxidation by Fenton Reagent. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 5538–5543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duprez, D.; Delanoë, F.; Barbier, J.; Isnard, P.; Blanchard, G. Catalytic Oxidation of Organic Compounds in Aqueous Media. Catal. Today 1996, 29, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J. Degradation of Sulfamethazine by Gamma Irradiation in the Presence of Hydrogen Peroxide. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 250–251, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baran, W.; Adamek, E.; Sobczak, A.; Makowski, A. Photocatalytic Degradation of Sulfa Drugs with TiO2, Fe Salts and TiO2/FeCl3 in Aquatic Environment—Kinetics and Degradation Pathway. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2009, 90, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, Z.; Dhib, R.; Mehrvar, M. pH and UVA Real-time Data Feasibility for Monitoring Aqueous PVA Degradation in a Continuous Pilot-scale UV/H2O2 Photoreactor: Experimental and Statistical Analysis. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 103, 6056–6071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinski, I.; Juretic, D.; Kusic, H.; Peternel, I.; Bozic, A.L. Structural Aspects of the Degradation of Sulfoaromatics by the UV/H2O2 Process. J. Photochem. Photobiol. Chem. 2014, 293, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigma-Aldrich. Sulfanilic Acid SAFETY DATA SHEET; MilliporeSigma Canada Ltd.: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sigma-Aldrich. Oxalic Acid SAFETY DATA SHEET; MilliporeSigma Canada Ltd.: Oakville, ON, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Honeywell International Inc. Formic Acid SAFETY DATA SHEET; Honeywell International Inc.: Morris Plains, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).