Hydrothermal Modification of Coal Gangue for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Adsorption: Modelling and Optimization of Process Parameters by Response Surface Methodology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Hydrothermal Modification of CG

2.3. Box–Behnken Method

2.4. Adsorption Capacity Test of Cd2+ and Pb2+

2.5. Characterization of Modified CG

3. Results

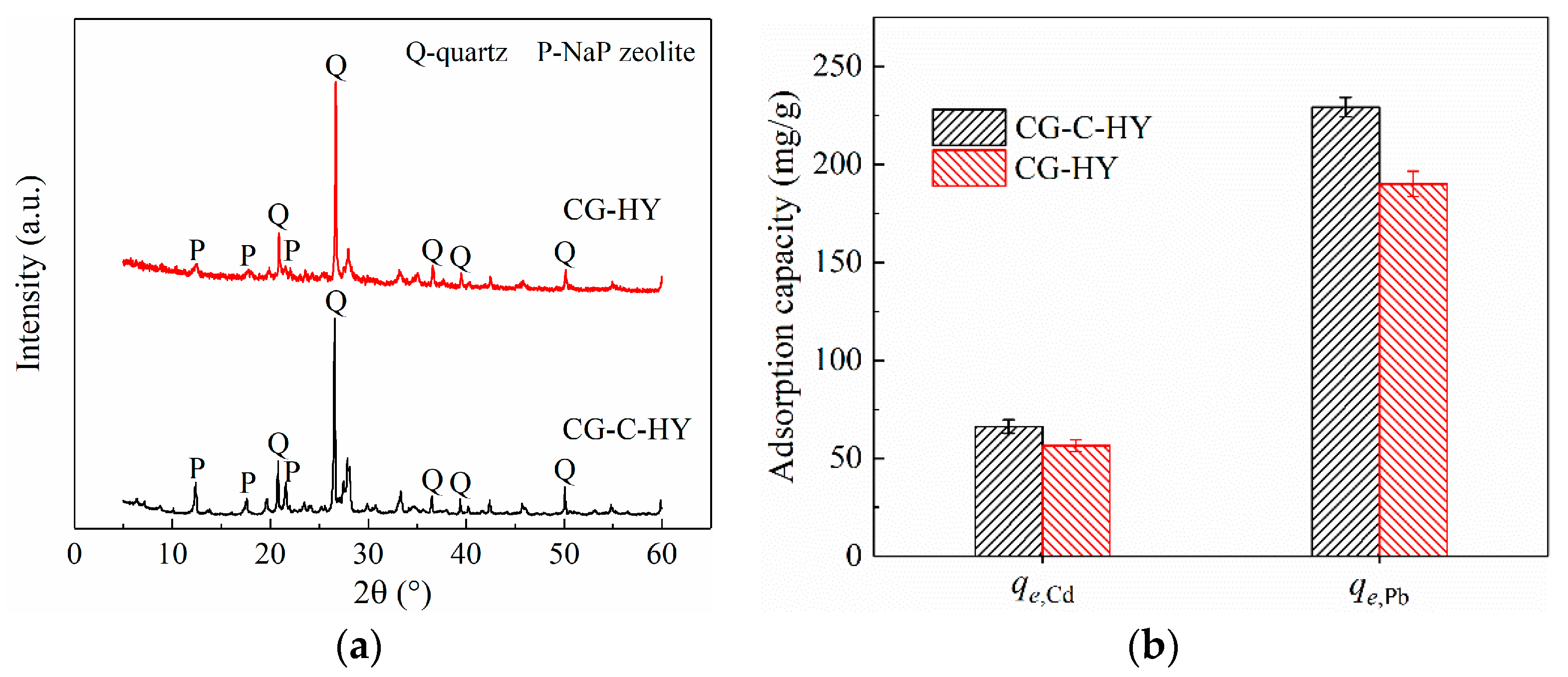

3.1. Effect of Calcination Pretreatment on CG Modification

3.2. Effect of Different Parameters on CG Modification

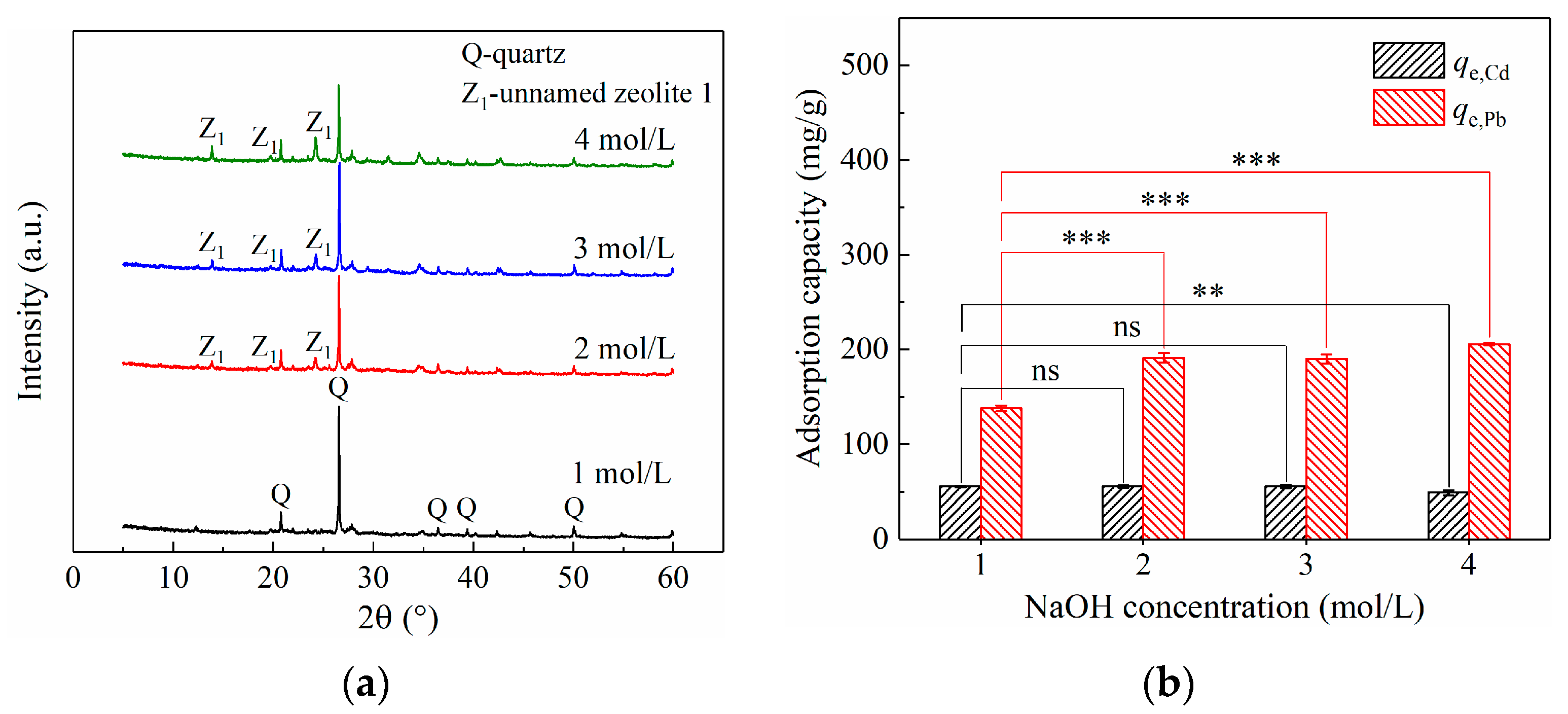

3.2.1. Effect of NaOH Concentration on CG Modification

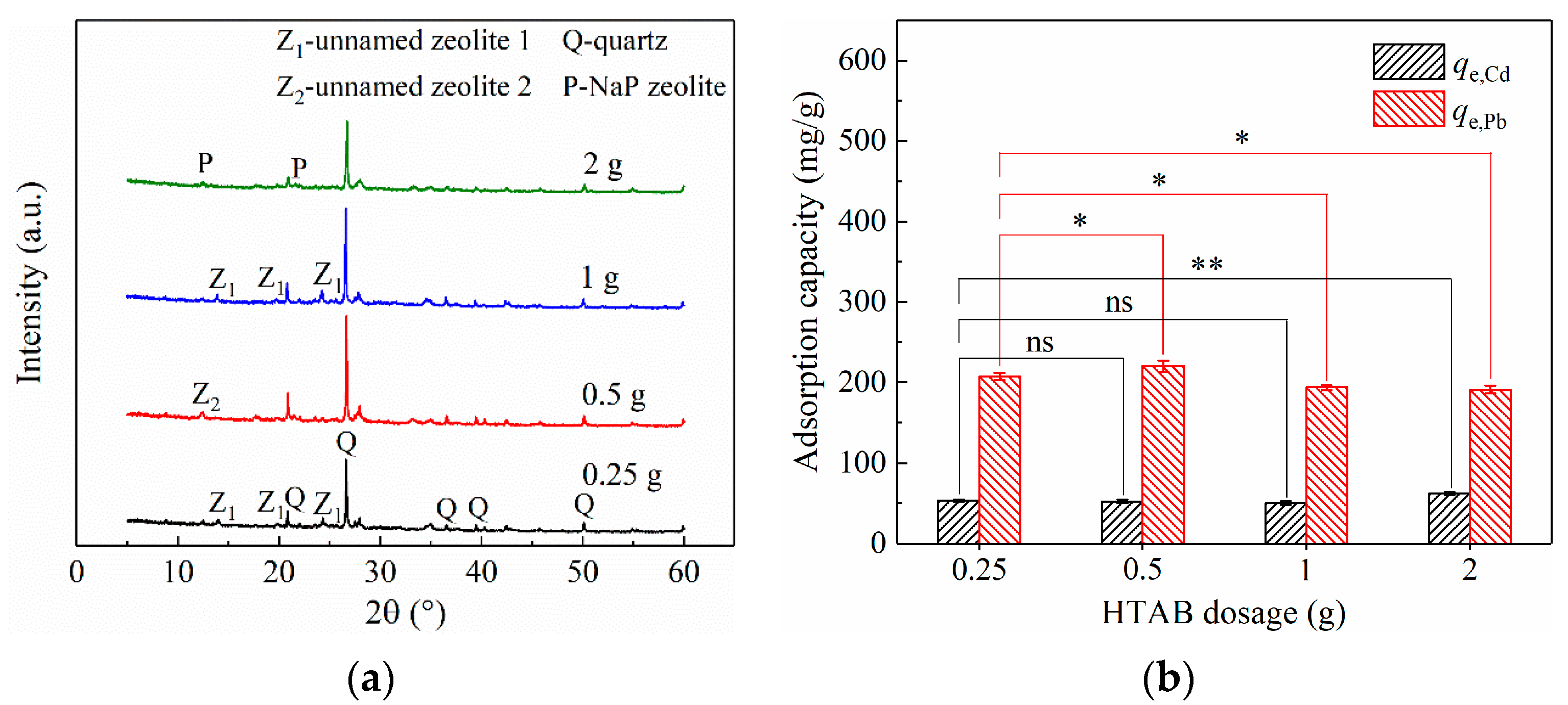

3.2.2. Effect of HTAB Dosage on CG Modification

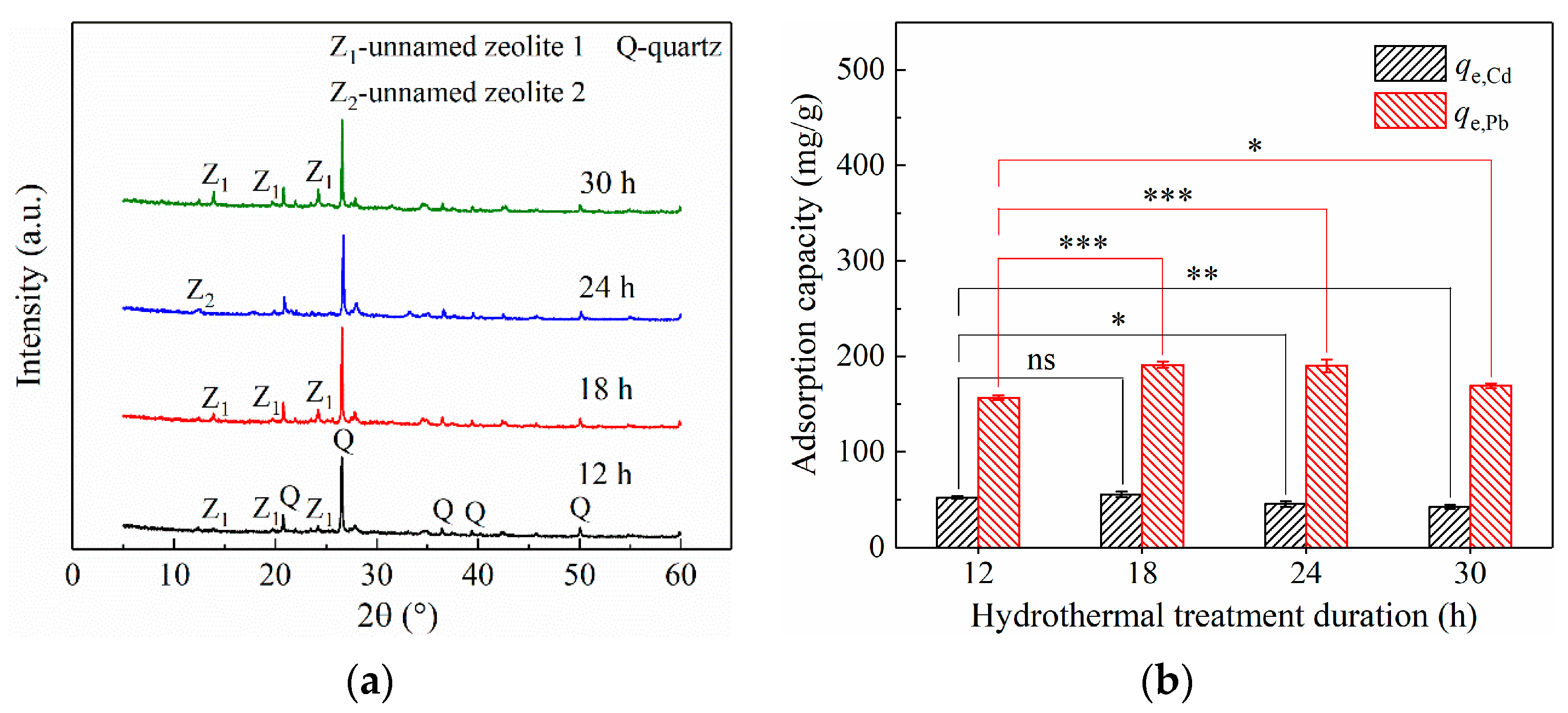

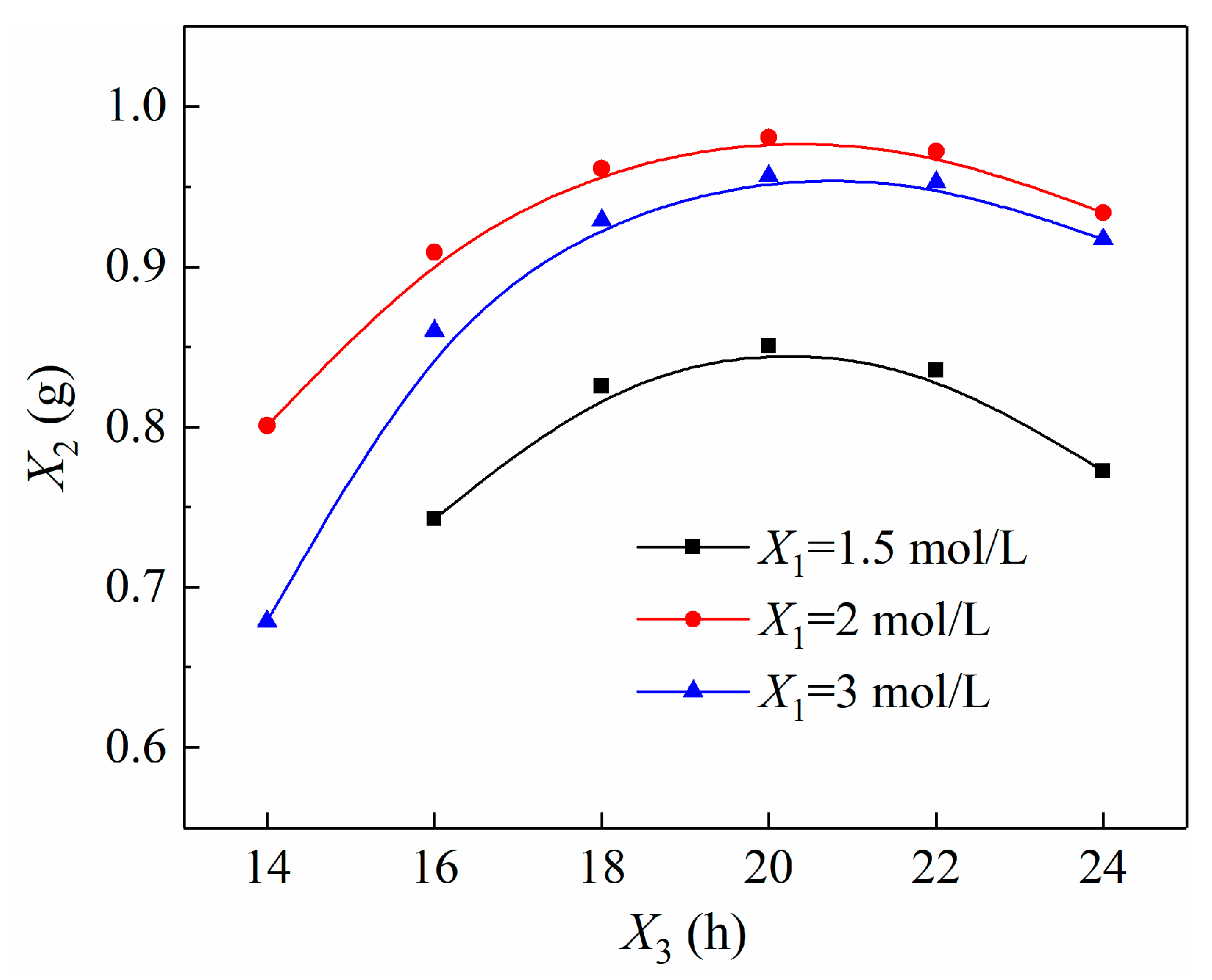

3.2.3. Effect of Hydrothermal Treatment Duration on CG Modification

3.3. Optimization of Modification Conditions by RSM

3.3.1. RSM Model Fitting

3.3.2. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) Tests

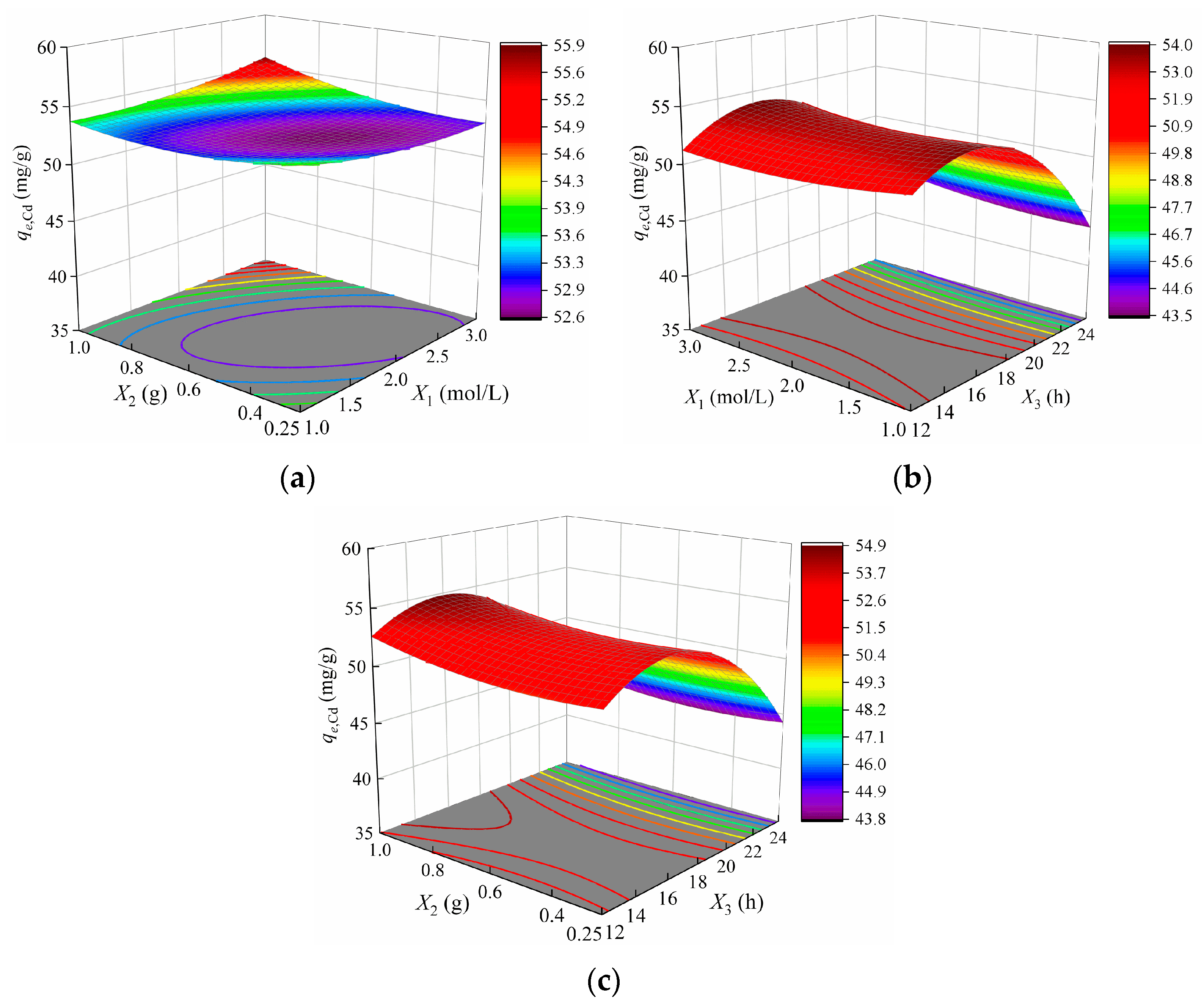

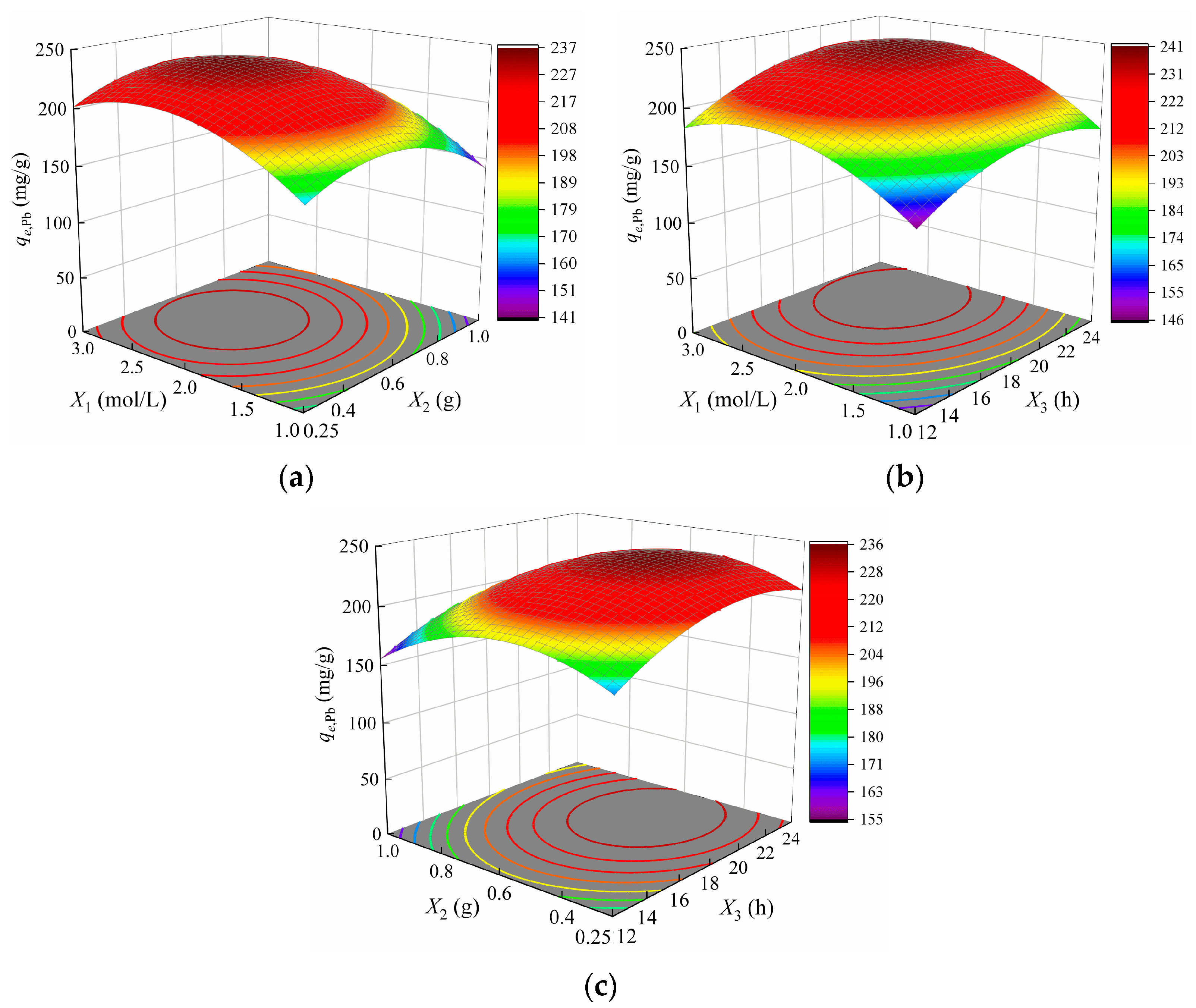

3.3.3. Variables Interactions Analysis

3.3.4. Validation

3.4. Characterization of Modified CG Before and After Adsorption

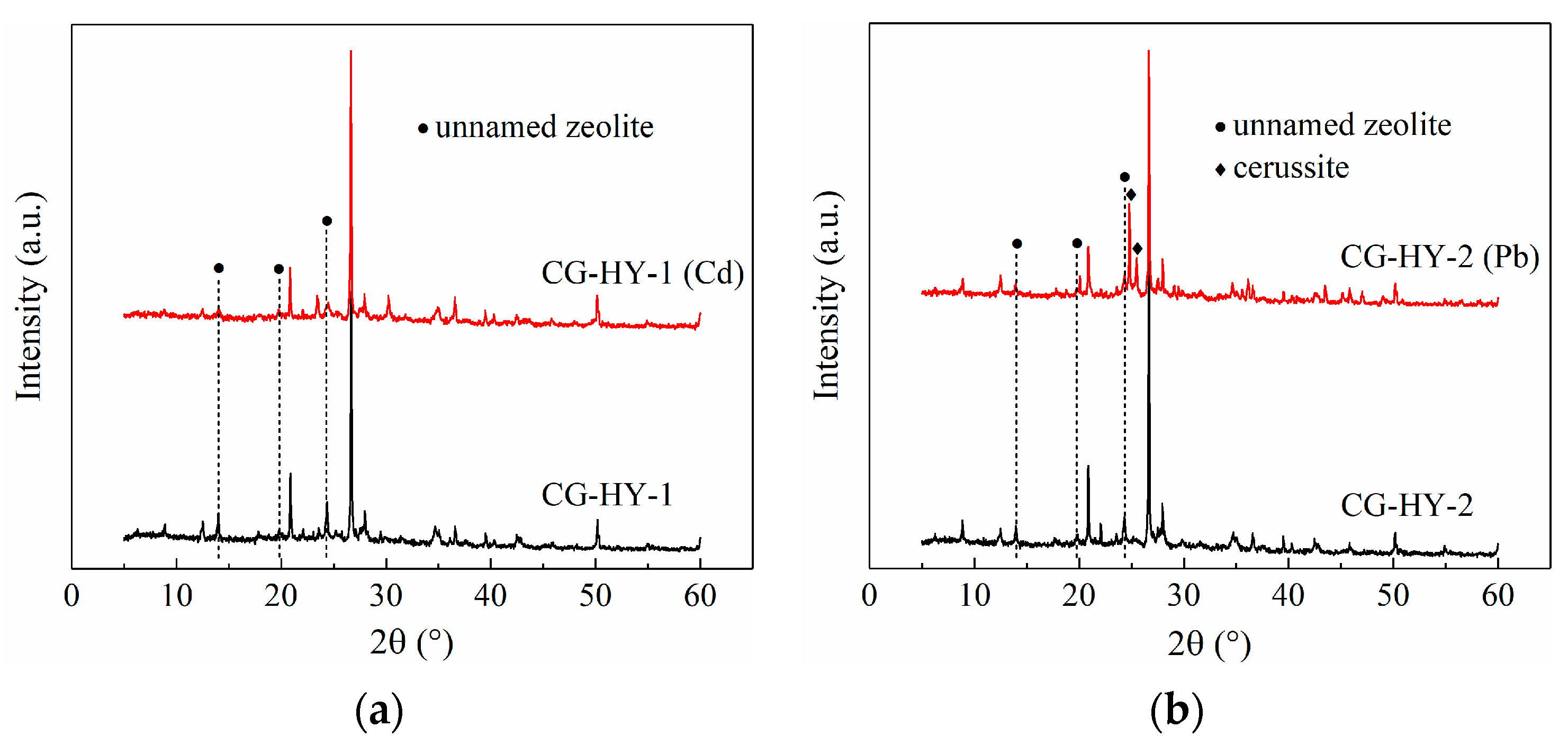

3.4.1. XRD

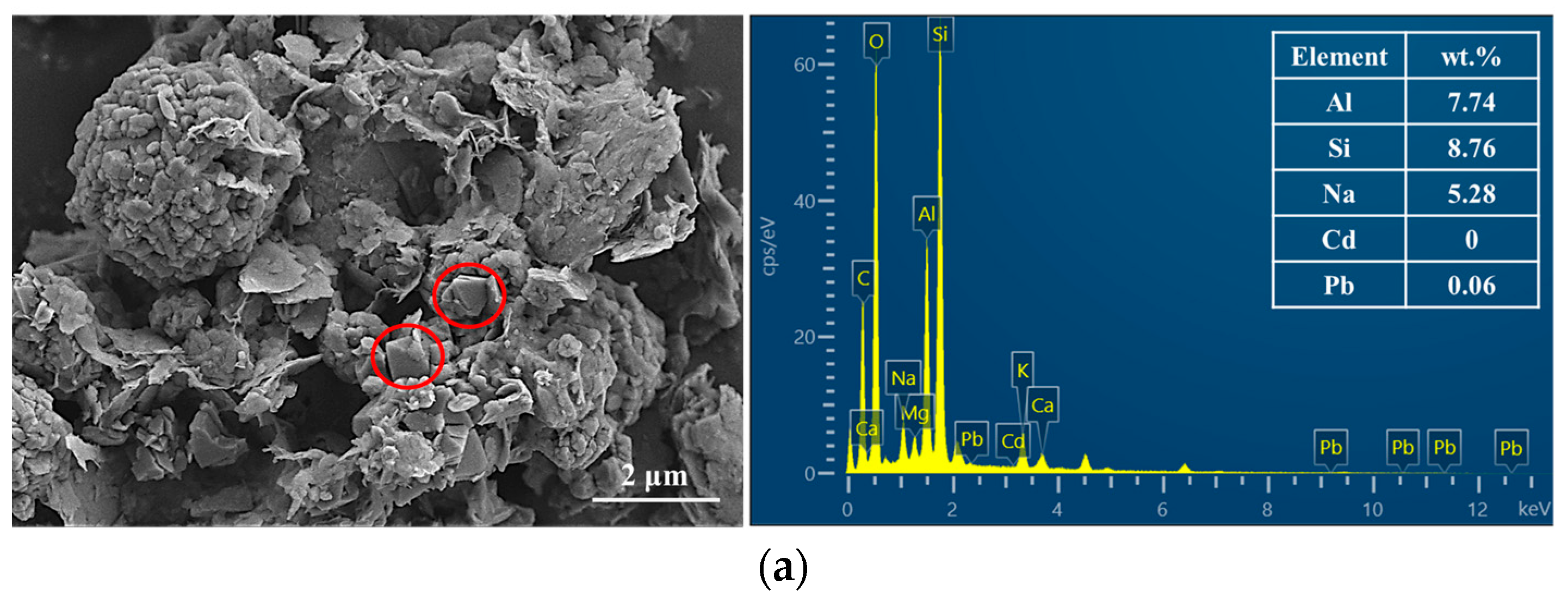

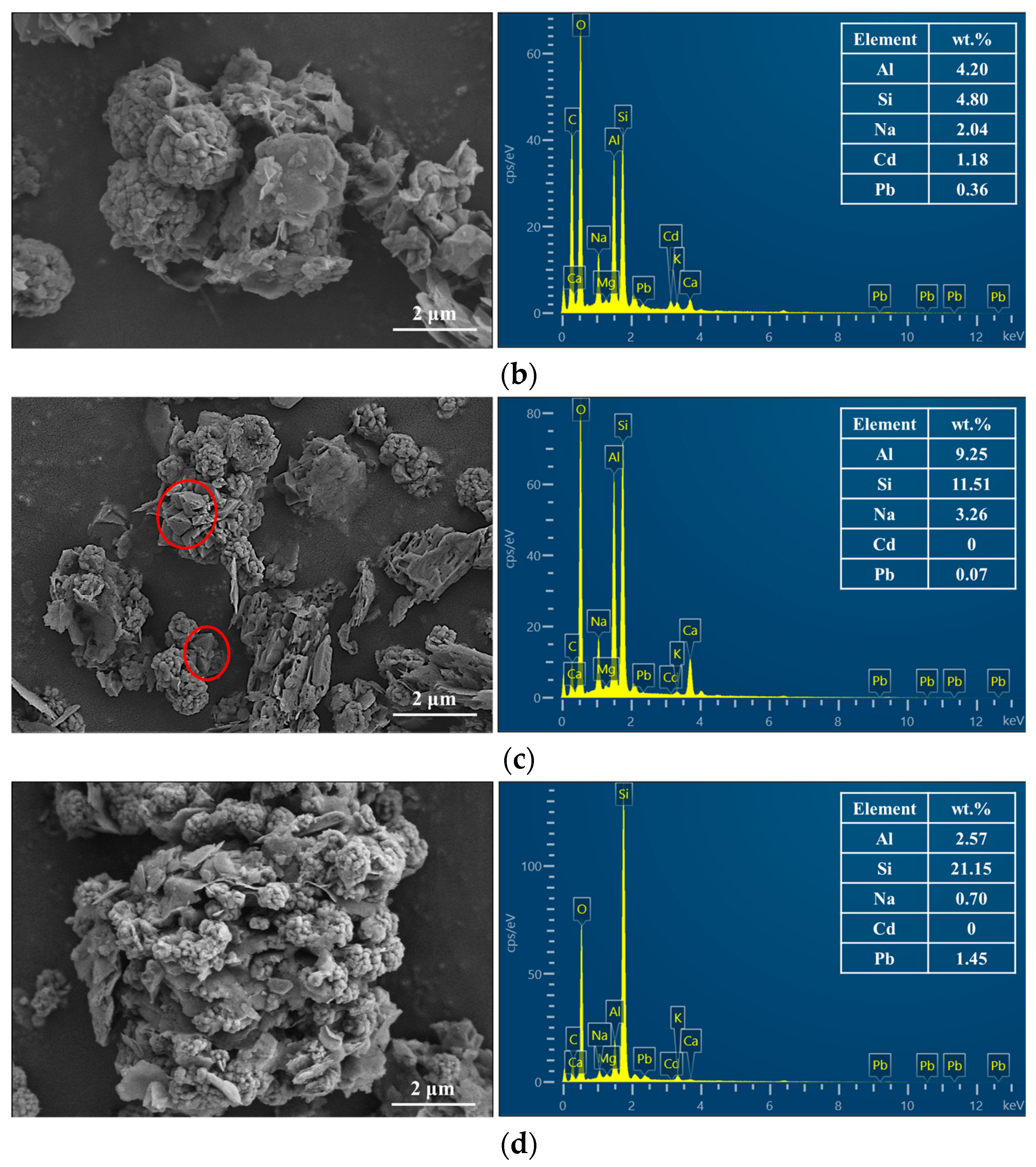

3.4.2. SEM-EDX

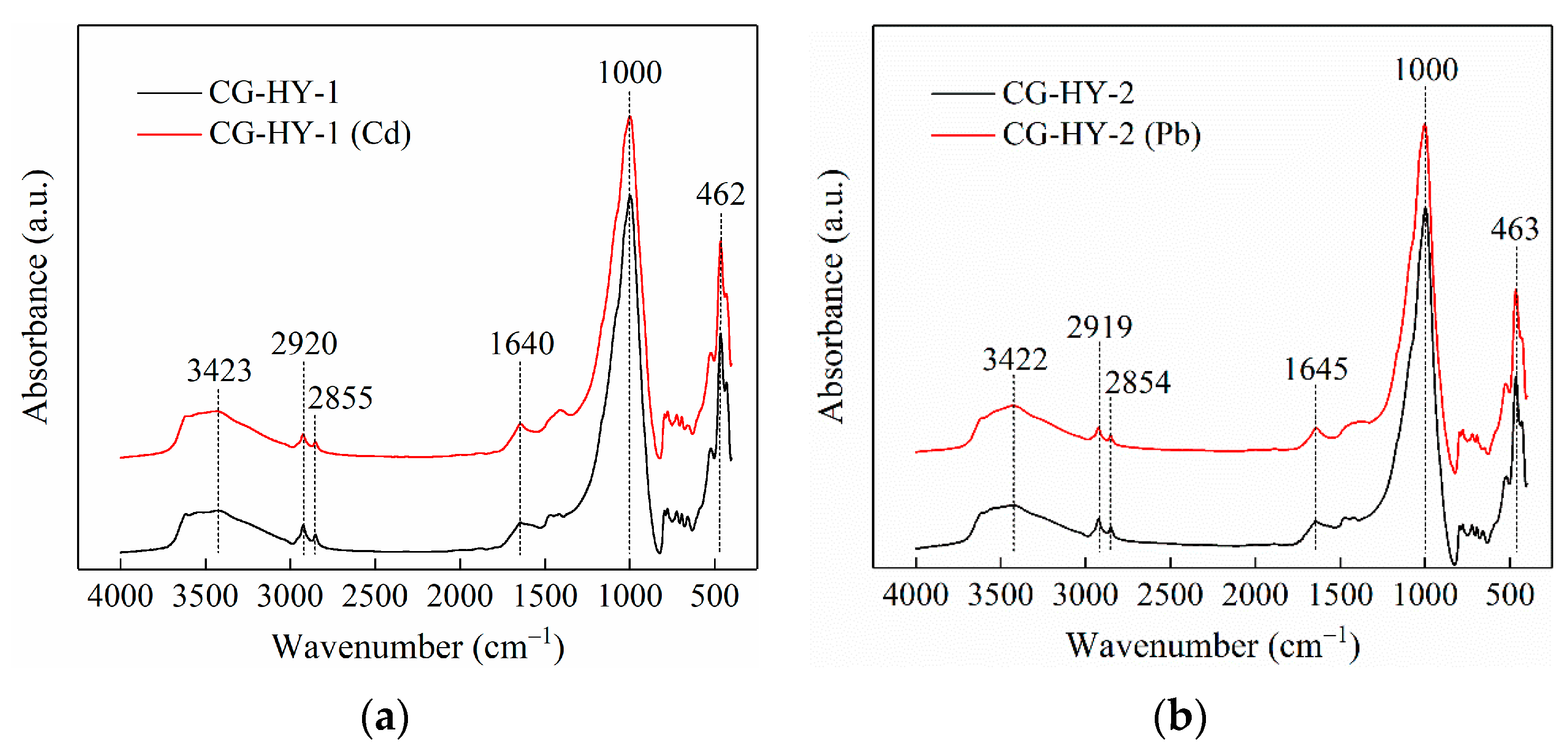

3.4.3. FTIR

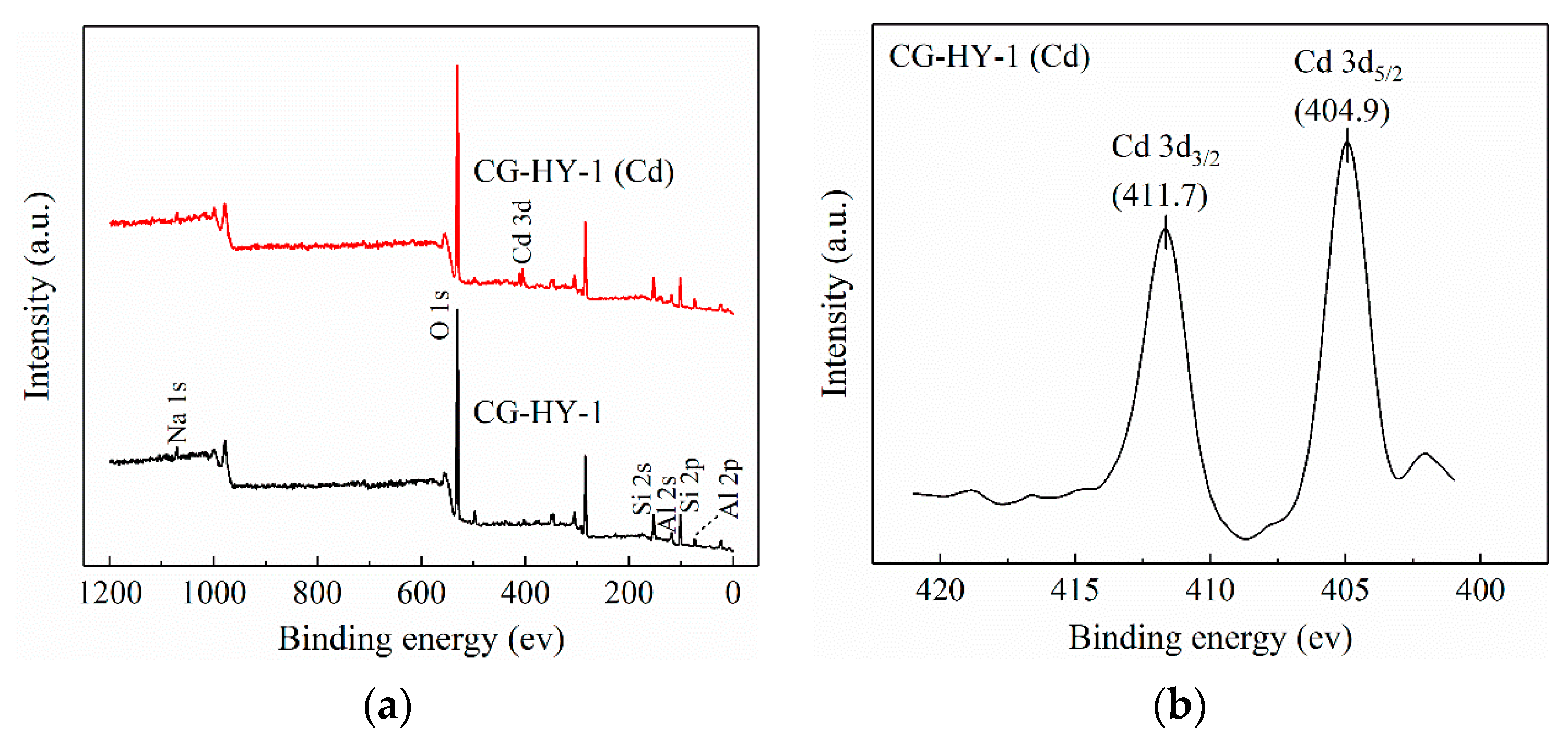

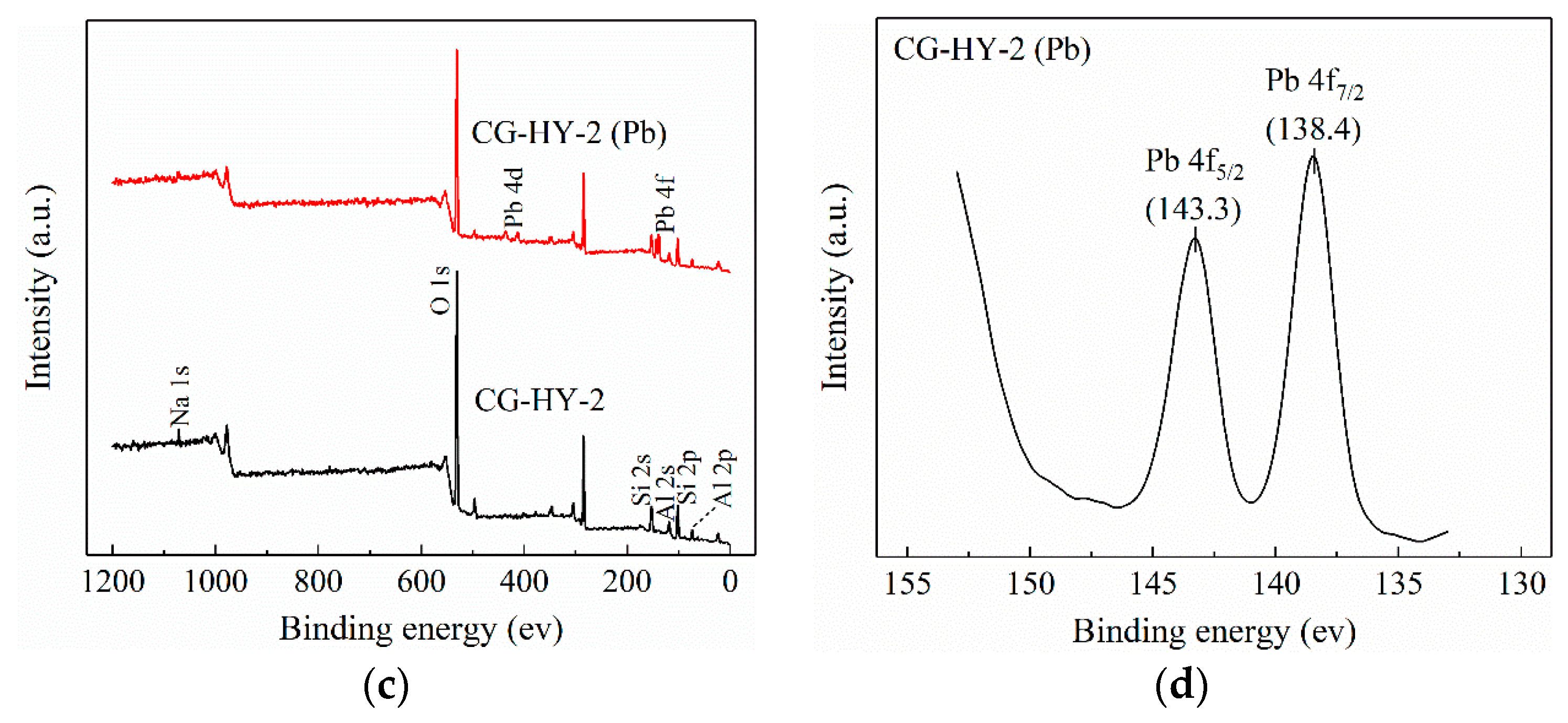

3.4.4. XPS

4. Discussion

4.1. Synthesis Strategies for Low-Cost Hydrothermally Modified CG Adsorbents

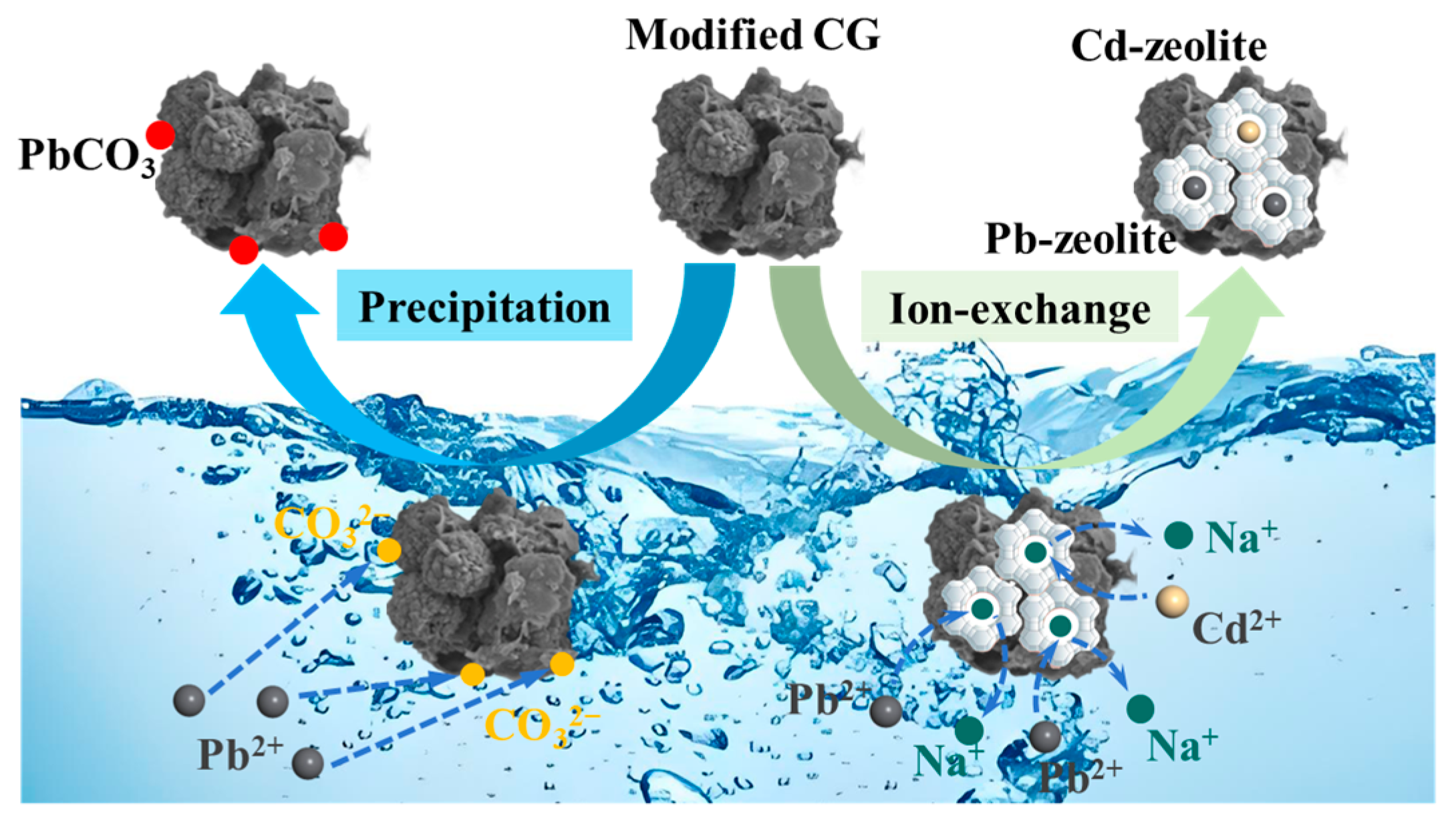

4.2. Adsorption Mechanism of Hydrothermally Modified CG for Cd2+ and Pb2+

4.3. Adsorption Capacity of Hydrothermally Modified CG for Cd2+ and Pb2+

4.4. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The optimal modification conditions for Cd2+ adsorption (qe,Cd = 58.4 mg/g) were determined as X1 = 2.9 mol/L, X2 = 1 g and X3 = 16.8 h. For Pb2+ adsorption (qe,Pb = 233.6 mg/g), the optimal parameters were X1 = 2.4 mol/L, X2 = 0.57 g and X3 = 20.7 h.

- (2)

- Hydrothermal duration was identified as a critical factor influencing Cd2+ adsorption, with a suitable range of 14–18 h. For Pb2+ adsorption, all three parameters—X1, X2, X3—played significant roles, with optimal ranges of X1 = 1.8–3 mol/L, X2 = 0.4–0.8 g, and X3 = 16–24 h.

- (3)

- Hydrothermal modification promoted the formation of zeolite structures in the modified CG, enhancing its adsorption properties. The primary adsorption mechanism for Cd2+ and Pb2+ involved ion exchange, with additional Pb2+ removal attributed to the precipitation of cerussite (PbCO3).

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CG | Coal gangue |

| RSM | Response surface methodology |

| YST | Coal gangue sample obtained from Yangshita coal mine |

| HTAB | Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide |

| CG-C-HY | Hydrothermally modified CG sample with calcination pretreatment |

| CG-HY | Hydrothermally modified CG sample without calcination pretreatment |

| X1 | NaOH concentration |

| X2 | Hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide dosage |

| X3 | Hydrothermal duration |

| qe,Cd | Adsorption capacity of modified coal gangue for Cd2+ |

| qe,Pb | Adsorption capacity of modified coal gangue for Pb2+ |

| Q | Quartz |

| Z1 | Unnamed zeolite 1 |

| Z2 | Unnamed zeolite 2 |

| P | NaP zeolite |

| CG-HY-1 | Modified CG sample under optimized conditions for Cd2+ adsorption |

| CH-HY-2 | Modified CG sample under optimized conditions for Pb2+ adsorption |

| CG-HY-1 (Cd) | CG-HY-1 sample after Cd2+ adsorption |

| CH-HY-2 (Pb) | CG-HY-2 sample after Pb2+ adsorption |

| Ksp | Solubility product |

References

- Ezzeddine, Z.; Batonneau-Gener, I.; Ghssein, G.; Pouilloux, Y. Recent advances in heavy metal adsorption via organically modified mesoporous silica: A review. Water 2025, 17, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Moeen, M.; Tian, Q.; Xu, J.; Feng, K. Highly effective removal of Pb2+ in aqueous solution by Na-X zeolite derived from coal gangue. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 7398–7408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuldeyev, E.; Seitzhanova, M.; Tanirbergenova, S.; Tazhu, K.; Doszhanov, E.; Mansurov, Z.; Azat, S.; Nurlybaev, R.; Berndtsson, R. Modifying natural zeolites to improve heavy metal adsorption. Water 2023, 15, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasseh, N.; Khosravi, R.; Rumman, G.A.; Ghadirian, M.; Eslami, H. Adsorption of Cr (VI) ions onto powdered activated carbon synthesized from Peganum harmala seeds by ultrasonic waves activation. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yao, Q.; Xu, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Experimental study on the purification mechanism of mine water by coal gangue. Water 2023, 15, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, N.; Liu, X.; Song, S.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q.; Li, R.; Zheng, F.; Yan, L.; Zhen, Q.; Zhang, J. Synthesis of NaY zeolite from coal gangue and its characterization for lead removal from aqueous solution. Adv. Powder Technol. 2020, 31, 2699–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Q.; Tian, Q.; Hou, R.; Wang, S. Combing phosphorus-modified hydrochar and zeolite prepared from coal gangue for highly effective immobilization of heavy metals in coal-mining contaminated soil. Chemosphere 2022, 291, 132835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, R.; Cheng, F. Modification of waste coal gangue and its application in the removal of Mn2+ from aqueous solution. Water Sci. Technol. 2016, 74, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jabłońska, B.; Kityk, A.V.; Busch, M.; Huber, P. The structural and surface properties of natural and modified coal gangue. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 190, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, L.; Wang, R.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, L.; He, Y.; Yin, C.; Zhang, X. Investigation on the adsorption performance of modified coal gangues to p-hydroxybenzenesulfonic acid. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 40, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Huang, J.; Li, M.; Dai, Z.; Jiang, R.; Zhang, J. Chemical modification of combusted coal gangue for U(VI) adsorption: Towards a waste control by waste strategy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Li, P.; He, X. Remediation of cadmium contaminated soil by modified gangue material: Characterization, performance and mechanisms. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, R.; Cheng, F.; Huang, H. Removal of Cd2+ from aqueous solution using hydrothermally modified circulating fluidized bed fly ash resulting from coal gangue power plant. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 1918–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Lu, C.; Bai, L.; Guo, N.; Xing, Z.; Yan, Y. Removal of Cd2+ and Pb2+ from an aqueous solution using modified coal gangue: Characterization, performance, and mechanisms. Processes 2024, 12, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Z.; Zhang, L.W.; Zhao, X.; Liu, S.; Li, D. Removal of Pb(II), Cd(II) and Hg(II) from aqueous solution by mercapto-modified coal gangue. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 231, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Su, Y.; Du, C. A novel and green strategy for efficient removing Cr(VI) by modified kaolinite-rich coal gangue. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 211, 106208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Zheng, S.; Di, Y.; Sun, Z. A review of the synthesis and application of zeolites from coal-based solid wastes. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Shi, D.; Chen, J. Sorption of Cu2+ and Co2+ using zeolite synthesized from coal gangue: Isotherm and kinetic studies. Environ. Earth Sci. 2017, 76, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lu, X. Synthesis and characterization of zeolites NaA and NaX from coal gangue. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2018, 20, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Wang, D. Synthesis and characterization of low-cost zeolite NaA from coal gangue by hydrothermal method. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Jiang, R. Preparation of NaA zeolite from high iron and quartz contents coal gangue by acid leaching—Alkali melting activation and hydrothermal synthesis. Crystals 2021, 11, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zheng, F.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Huang, X.; Chen, L.; Hu, P.; Gao, J.; Zhen, Q.; Bashir, S.; et al. Facile preparation of zeolite-activated carbon composite from coal gangue with enhanced adsorption performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 390, 124513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 212-2008; Proximate Analysis of Coal. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- Ren, Z.; Li, Z.; Tang, H.; Yang, L.; Zhu, J.; Jing, Q. Analysis of response surface and artificial neural network for Cr(Ⅵ) removal column experiment. Water 2025, 17, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.; Liu, G.; Meng, X.; Huang, C.; Chen, S.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, W.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y. Carbon reduction strategies for typical wastewater treatment processes (A2/O): Response surface optimization, mechanism, and application analysis. Water 2025, 17, 2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, H.; Ohmori, H. Dual-wavelength spectrophotometric determination of Cadmium with cadion. Talanta 1979, 26, 959–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boostani, H.R.; Najafi-Ghiri, M.; Khalili, D. Comparative effectiveness of pristine and H3PO4-modified biochar in combination with bentonite to immobilize cadmium in a calcareous soil. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, F.; Niu, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Sun, W.; He, D. Efficient removal of Pb(II) ions from aqueous solution by modified red mud. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 406, 124678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Z.; Yan, Y.; Bai, L.; Guo, N.; Xing, Z.; Lu, C. Synthesis and characterization of NaX zeolite from coal gangue and its efficacy in cd and pb remediation in water and soil. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 51237–51252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Liu, Z.; Han, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Zhu, S.; Li, Z.P.J.; Wang, D. Synthesis of coal-analcime composite from coal gangue and its adsorption performance on heavy metal ions. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y. Review of the natural, modified, and synthetic zeolites for heavy metals removal from wastewater. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2016, 33, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Yang, Y.; Ji, P. Potential of removing Cd(II) and Pb(II) from contaminated water using a newly modified fly ash. Chemosphere 2020, 242, 125148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, H.; Jamil, T.; Hegazy, E. Application of zeolite prepared from Egyptian kaolin for the removal of heavy metals: II. Isotherm models. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 182, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.Y.; Zhao, C.; Hu, X.M.; Tong, Z.F.; Yun, J.G.; Wei, N.H.; Wang, K.J.; Liu, C.X.; Zou, Y.; Chen, Z.H. Utilization of coal gangue for preparing high-silica porous materials with excellent ad/desorption performance on VOCs. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 3498–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angaru, G.K.R.; Lingamdinne, L.P.; Choi, Y.L.; Koduru, J.R.; Chang, Y.Y. Catalytic binary oxides decorated zeolite as a remedy for As(III) polluted groundwater: Synergistic effects and mechanistic analysis. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.H.; Geum, D.E.; Jaber, M.; Park, P. Sulfide-occluded zeolite X for effective removal of Hg2+ from aqueous systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | K2O | Na2O | CaO | MgO | SO3 | P2O5 | Others | SiO2/Al2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YST | 64.64 | 21.43 | 3.56 | 3.59 | 0.87 | 2.51 | 0.92 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 2.00 | 5.13 |

| Run No. | NaOH Concentration (mol/L) | HTAB Dosage (g) | Hydrothermal Duration (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| effect of NaOH concentration | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 18 |

| 2 | 2 | ||

| 3 | 3 | ||

| 4 | 4 | ||

| effect of HTAB dosage | |||

| 5 | 2 | 0.25 | 18 |

| 6 | 0.5 | ||

| 7 | 1 | ||

| 8 | 2 | ||

| effect of hydrothermal duration | |||

| 9 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| 10 | 18 | ||

| 11 | 24 | ||

| 12 | 30 | ||

| Run No. | X1 (mol/L) | X2 (g) | X3 (h) | qe,Cd | qe,Pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3 | 1 | 18 | 55.5 | 190.0 |

| 2 | 2 | 0.5 | 18 | 55.1 | 220.2 |

| 3 | 2 | 0.5 | 18 | 52.0 | 224.7 |

| 4 | 3 | 0.25 | 18 | 52.2 | 207.2 |

| 5 | 3 | 0.5 | 12 | 52.1 | 177.7 |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 24 | 45.6 | 190.0 |

| 7 | 2 | 0.5 | 18 | 52.5 | 237.9 |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 18 | 54.2 | 137.8 |

| 9 | 1 | 0.5 | 12 | 52.1 | 148.9 |

| 10 | 2 | 0.5 | 18 | 50.4 | 229.9 |

| 11 | 1 | 0.5 | 24 | 42.5 | 180.4 |

| 12 | 2 | 1 | 12 | 52.1 | 156.7 |

| 13 | 2 | 0.25 | 12 | 50.2 | 170.5 |

| 14 | 1 | 0.25 | 18 | 55.1 | 160.6 |

| 15 | 3 | 0.5 | 24 | 45.0 | 219.7 |

| 16 | 2 | 0.25 | 24 | 45.1 | 207.2 |

| 17 | 2 | 0.5 | 18 | 53.1 | 244.4 |

| Adsorbent | Adsorption Capacities (mg/g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cd2+ | Pb2+ | Reference | |

| Hydrothermally Modified CG | 58.4 | 233.6 | This Work |

| Raw CG of Yangshita Mine | 7.7 | 26.8 | [14] |

| Hydrothermally Modified CG of Yangshita Mine | 72.7 | 247.5 | [14] |

| NaX Zeolite Parepared from Yangshita CG | 187.5 | 427.6 | [29] |

| Mercapto Modified CG | 110.4 | 332.8 | [15] |

| Coal-analcime Composite from CG | 54.1 | / | [30] |

| Low-temperature KOH Modified CG | 70.7 | / | [12] |

| Hydrothermally Modified Fly Ash | 183.7 | / | [13] |

| Natural Zeolite Treated with NaCl | / | 91.2 | [31] |

| Low-temperature NaOH Modified Fly Ash | / | 126.6 | [32] |

| NaA Zeolite Prepared from Kaolin | / | 213.4 | [33] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Guo, N.; Fang, J.; Li, S. Hydrothermal Modification of Coal Gangue for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Adsorption: Modelling and Optimization of Process Parameters by Response Surface Methodology. Water 2025, 17, 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233441

Wang X, Guo N, Fang J, Li S. Hydrothermal Modification of Coal Gangue for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Adsorption: Modelling and Optimization of Process Parameters by Response Surface Methodology. Water. 2025; 17(23):3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233441

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaolong, Nan Guo, Jie Fang, and Shoubiao Li. 2025. "Hydrothermal Modification of Coal Gangue for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Adsorption: Modelling and Optimization of Process Parameters by Response Surface Methodology" Water 17, no. 23: 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233441

APA StyleWang, X., Guo, N., Fang, J., & Li, S. (2025). Hydrothermal Modification of Coal Gangue for Cd2+ and Pb2+ Adsorption: Modelling and Optimization of Process Parameters by Response Surface Methodology. Water, 17(23), 3441. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233441