Abstract

Rainfall simulators are crucial devices in erosion research, enabling the controlled reproduction of precipitation characteristics for both laboratory and field investigations. This study presents a comprehensive characterization of a rainfall simulator originally designed to assess the erosive effects of precipitation on heritage surfaces. The simulator, installed at the University of León, was evaluated using volumetric methods and disdrometric techniques, employing a Parsivel2 optical disdrometer. Simulations were conducted with a falling height of 10 m and high-intensity rainfalls. Spatial uniformity was assessed through thematic mapping and the Christiansen Uniformity (CU) coefficient, revealing limited uniformity across the full wetted area, but an improved performance within the central zone (CU up to 80%). Disdrometric data provided detailed insights into drop size and velocity distributions, enabling the estimation of rainfall intensity, kinetic energy, and momentum, as well as the spatial uniformity of the energetic parameters. Empirical models to estimate the raindrop’s fall velocity were tested against disdrometric measurements, confirming the simulator’s ability to generate rainfall with velocity characteristics comparable to those of natural precipitation. Moreover, the findings underscore the importance of integrating multiple measurement approaches to enhance the reliability and accuracy of rainfall simulator characterization.

1. Introduction

The importance of rainfall simulators in erosion research lies in their capacity to reproduce key precipitation characteristics, such as rainfall intensity, kinetic energy, and momentum, in a rapid and controlled manner while eliminating the variability inherent to natural rainfall [1,2,3,4]. Due to these advantages, rainfall simulators have been used as a systematic approach for both laboratory and field studies [5,6,7].

Over time, a wide range of simulators has been designed [8], each adapted to specific research topics, including soil erosion [9,10,11,12], hydrology [13,14], water infiltration [15,16], runoff and sediment transport [17,18,19], heritage surfaces erosion [20,21], soil texture [22,23], the roles of runoff and splash erosion in soil degradation and landform development [24,25,26,27], or the assessment of environmental impacts [28,29,30].

Nevertheless, the development of high-fidelity rainfall simulators remains a considerable challenge [31]. Moreover, despite their widespread use, the lack of standardized protocols and the heterogeneity of research goals represent additional limitations [32,33,34,35,36], constraining the comparison of research results [8,37]. Indeed, devices range from simple drip systems with capillary tubes [38] to pressurized nozzles/sprinklers [31] and aspersion mechanisms [20]; some operate under highly controlled laboratory conditions, while others are deployed in full-scale field plots; rainfalls can be applied from microplots [39] to large field plots [40].

Few recognized protocols provide standardized procedures for rainfall simulator calibration, testing configuration, and data collection and analysis. As an example, the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) developed the ASTM D6459 and the ASTM D7101 protocols for rolled erosion control [41,42,43,44,45]; both aim to ensure the reproducibility and comparability of erosion-related experiments, promoting consistent evaluation of hydraulic performance under simulated rainfall conditions.

Common approaches for characterizing rainfall simulators typically include the use of rain collectors to quantify rainfall intensity, photographic techniques to determine raindrop fall velocity, and disdrometers to evaluate the size and velocity distribution of simulated raindrops [46,47,48]. However, the choice of a particular characterization method can significantly influence the measured rainfall parameters [37,49,50,51], potentially introducing variability into the results and highlighting the need for standardized protocols to ensure comparability across studies [52,53,54].

Green and Pattison [55] stated that the number, spatial arrangement, and physical characteristics of rainfall collectors, such as their size and shape, directly affect the representation of rainfall distribution over a plot surface. According to the authors, these factors influence the assessment of uniformity, which is usually quantified using the Christiansen Uniformity (CU) coefficient:

in which Ii is the rainfall intensity of a single rain collector, IS is the mean rainfall intensity, and nc (−) is the number of rainfall collectors. Thus, as the CU value approaches 100%, the rainfall pattern becomes increasingly uniform.

In other words, the CU method is susceptible to the sampling resolution and the layout of collectors, resulting in differences in a rainfall simulator characterization when different experimental setups are employed. As a consequence, the CU reflects both the performance of the applied testing procedure and the simulator’s actual performance. However, the CU coefficient remains one of the most widely applied methods due to its simplicity, widespread acceptance, and long-standing use as a standard metric for comparing rainfall simulator performance across different studies [55].

In previous literature, various thresholds of the CU coefficient have been proposed to evaluate the spatial uniformity of rainfall simulators. A classification, originally developed by the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (ASABE) [56] for irrigation systems, also adopted in rainfall simulation research as a benchmark for experimental reliability [12,20], defines drippers and nozzles as follows: unacceptable (CU < 60%), poor (60% ≤ CU < 70%), fair (70% ≤ CU < 80%), good (80% ≤ CU < 90%), and excellent (CU ≥ 90%). Other authors [10,11,57,58] consider rainfall to be uniform when CU exceeds 80%, especially in small-scale experiments. For large plot areas, a threshold of 70% or less has been accepted in some studies [26,59].

Regarding the use of photographic methods for estimating the fall velocity of raindrops, although these techniques have proven reliable, particularly in drip-type rainfall simulators [49,50], their application in pressurized or other complex devices faces several practical limitations. Manual procedures are time-consuming and labor-intensive; in addition, results depend on the operator, and errors can occur in the estimated kinetic energy of up to ±28% compared with the results obtained using automated methods [60]. Additional limitations arise from drop deformation during free fall, which tends to flatten drops, affecting velocity estimation [61]. Furthermore, drops located too close or too far from the camera calibration plane appear enlarged or reduced, respectively, requiring the filtering of out-of-focus data [61]. Finally, in multi-nozzle simulators with high drop densities, drop overlap in the image plane can lead to identification and sizing errors [61].

Currently, disdrometers represent the last advancement in the field, enabling a comprehensive characterization of precipitation. Specifically, these devices provide detailed measurements of the rainfall Particle Size and Velocity Distribution (PSVD), which is crucial for a more reliable estimation of the rainfall kinetic energy, Pn (J/m2/s), and momentum, M (N/m2). These are two key parameters to define rainfall erosivity [62] and play a central role in soil detachment and splash erosion processes [8,63], infiltration and runoff dynamics [64], and rainfall-induced deterioration of cultural heritage surfaces [20].

Most disdrometers use a laser optical technology, such as the Eigenbrodt ODM 470 [65,66], the Laser Precipitation Monitor (LPM) [67], the Multi-Angle Snowflake Camera [68], the Particle Size Velocity (Parsivel) [69] and its integrated version (Parsivel2) [70], and the two-dimensional video disdrometer [71,72].

Among the various disdrometers available, the Parsivel2 (OTT Hydromet GmbH, Kempten, Germany) and the LPM (Thies Clima, Göttingen, Germany) are particularly prevalent in the field of rainfall simulator characterization [8,73,74,75,76,77,78].

Research on natural precipitation using Parsivel2 and LPM disdrometers [79] has demonstrated that both instruments systematically tend to underestimate raindrop fall velocity and exhibit substantial discrepancies in the measured PSVD, with these differences becoming more pronounced at higher rainfall intensities. According to the authors [79], such differences and underestimations may arise from both hardware- and software-related factors, including geometric variations in the laser configuration.

Further potential biases intrinsic to optical disdrometers include the nonuniform power distribution across the laser beam, the misinterpretation of multiple particles as a single drop, and the occurrence of margin fallers, i.e., drops that only partially intersect the beam and are therefore not fully detected [80]. Although the manufacturers state that these devices incorporate corrections for margin fallers and multiple particles, the specific methodologies employed to address these sources of error remain undisclosed [79].

Therefore, due to the widespread tendency of optical disdrometers to underestimate fall velocity, several studies [72,79,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] have avoided the use of measured velocity distributions, opting instead for empirical relationships [88,89,90,91] calibrated on natural rainfall data, which relate terminal velocity, defined as the equilibrium speed at which gravitational and aerodynamic drag forces are balanced [92], to raindrop diameter.

Based on the experimental data of Gunn and Kinzer [88], Atlas et al. [89] and Atlas and Ulbrich [90] adopted the following empirical relationship to estimate the terminal velocity of raindrops, V(D) (m/s), as a function of their diameter D (mm):

Beard [91] did not propose a closed equation for estimating fall velocity but developed a physically based model in which environmental variables (such as altitude, latitude, temperature, relative humidity, air pressure) are considered. Therefore, this parametric model uses several fit curves to represent the terminal velocity over specific diameter ranges and atmospheric conditions.

Another formulation used in literature [93,94], also to estimate raindrop terminal velocity in disdrometers that do not provide direct velocity measurement [92,95,96], is that of Ferro [97], who used measurements from several studies [88,91,98,99,100,101] to propose the following relationship:

in which D is expressed in cm, while the coefficients Vh (m/s) and ah (cm) vary with the falling height, assuming values, respectively, equal to 9.5 m/s and 6 cm for natural precipitations.

However, previous empirical formulations are not commonly applied in simulated rainfall experiments, since the limited drop falling height under laboratory conditions often prevents raindrops from reaching their terminal velocity.

An alternative approach is to apply empirical relationships validated under laboratory conditions to estimate the fall velocity of raindrops, in which V(D) is explicitly expressed as a function not only of the raindrop diameter but also of the drop falling height set during the experiment. Recently, after having analyzed fall velocity measurements in literature in the falling height range of 0.5 m to 20 m [98], Serio et al. [49] proposed the following relationship:

in which D is expressed in cm and h (m) is the falling height, i.e., the distance from the sprinkler’s outlet of the rainfall simulator to the disdrometer measuring surface. The reliability of Equation (4) was positively verified using both experimental fall velocity measurements, up to 1.3 m, obtained with a drip-type rainfall simulator [49] and literature data up to 13 m [99].

In this context, the primary contribution of this study is the comprehensive characterization of a laboratory rainfall simulator, which is currently being employed in studies on heritage erosion. This characterization is performed by comparing different approaches, i.e., a volumetric method using rain collectors and a disdrometric one employing a Parsivel2 disdrometer, and highlighting the discrepancies that can arise depending on the method chosen.

This is critical because erosion studies require the quantification of not only rainfall intensity but also crucial erosivity parameters such as rainfall kinetic energy and momentum, and their spatial uniformity across the tested surface.

The results presented here will deepen our understanding of the simulated rainfall’s characteristics, enabling us to adapt the current configuration to different events, thereby enhancing the simulator’s applicability to a variety of different situations focused on soil and heritage erosion.

In addition, disdrometric data and raindrop velocity distribution collected with an optical disdrometer are analyzed to evaluate the simulator’s ability to reproduce raindrop velocities comparable to those observed in natural rainfall.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

In the present study, the rainfall simulator (RS) recently proposed by Fernández-Raga et al. [20] is used; this RS was originally designed for studies on stone-based heritage erosion [20,102]. The device is located at the Department of Chemistry and Applied Physics, Industrial Engineering School, University of León. The characterization of the RS was performed using rain collectors for the volumetric calibration and an optical disdrometer (OTT Hydromet GmbH, model Parsivel2, Kempten, Germany) for the disdrometric one. The falling height, defined as the distance from the RS to the optical disdrometer sampling surface, was set to 10 m.

2.1.1. Rainfall Simulator Design

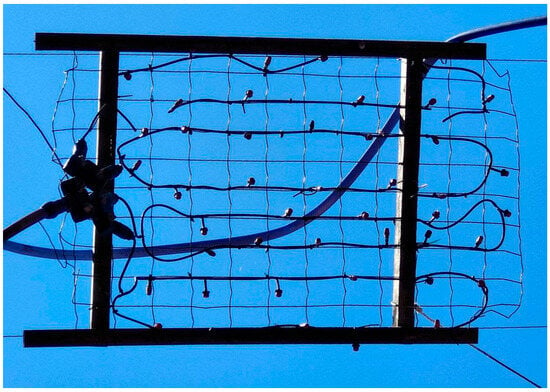

The RS is suspended and anchored by tensioned steel cables to the walls of an internal courtyard (Figure 1), whose vertical walls reduce the wind influence and prevent droplet drift.

Figure 1.

Rainfall simulator (RS) structure.

Tap water was avoided to supply the RS as its mineral content could, over time, compromise the hydraulic efficiency of the system by depositing calcium, especially in the smallest parts of the system (microsprinklers). Moreover, deionized water better represents natural rain from a physical/chemical point of view since the presence of salts modifies the water surface tension [103]. Therefore, using a purification system (Wasserlab, model DE7003, Barbatáin, Navarra, Spain), deionized water was continuously supplied to a 100 L tank equipped with a submersible pump (LISTA, Ehlis S.A., model Hidrosub AS-216, Illescas, Toledo, Spain).

Water was then conveyed to the main supply line using a surface pump (Hidrobex model EH-125, Parets del Vallés, Barcelona, Spain), which delivered it to the top of the internal courtyard. A constant pressure was selected for the present work. In particular, since weathering and erosion processes on stone-based cultural heritage occur over large temporal scales, an appropriate methodology already established for these scenarios [20,102,104] was followed, resulting in rainfall intensity values higher than those observed under natural precipitation conditions.

Still, since the surface pump loses power over time [20], its functioning was automated with an Arduino program. Therefore, after a continuous and constant run of 55 s, the program stops the pump for 5 s, thereby allowing for a constant mean flow rate over time. The cycle can be programmed for the desired time. For this investigation, a total rainfall cycle of 5 min was chosen.

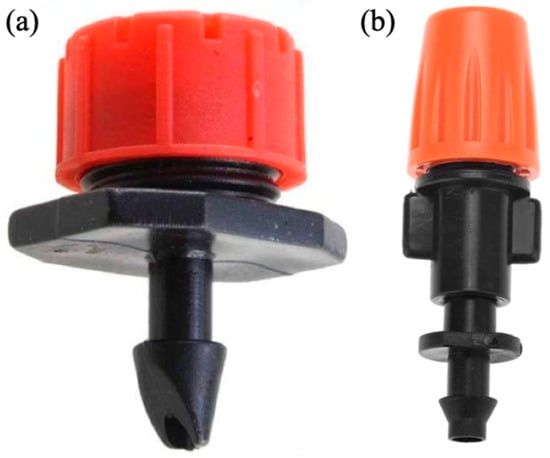

Once water reaches the upper part of the hydraulic system, the main pipeline feeds the RS structure (Figure 1), which consists of a metal frame supporting four independent pipes equipped with 46 emitters with a flow rate that can range from 1 to 70 L/h (Figure 2). Specifically, two emitter models commonly employed in gardening applications were selected: 26 drippers releasing droplets in eight peripheral directions (Figure 2a), and 20 minisprinklers with a single central outlet for drop release, which can generate a spray radius of 0–0.5 m (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Emitters employed in the RS: drippers (a) and minisprinklers (b).

Both emitter models allow a fine regulation of the outlet pressure by screwing/unscrewing, thus impacting the size of simulated raindrops. Consequently, to generate simulated rainfalls with the widest possible drop size variability, both the positioning and the opening of the drippers and the minisprinklers were set randomly.

2.1.2. Optical Disdrometer

The disdrometric calibration was performed using a Parsivel2 disdrometer (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Parsivel2 optical disdrometer (OTT Hydromet GmbH, Kempten, Germany).

This optical device is widely employed in both simulated and natural rainfall studies. It measures the diameter and fall velocity of individual raindrops, classifying them into 1024 possible size–velocity combinations: 32 diameter classes ranging from 0.2 mm to 25 mm, with class widths progressively increasing from 0.125 mm to 3 mm, and 32 velocity classes ranging from 0.2 m/s to 20 m/s, with class widths increasing from 0.1 m/s to 3.2 m/s. The assignment of each drop to a specific combination is governed by an undisclosed internal algorithm [84].

2.2. Laboratory Protocol for the Rainfall Simulator Characterization

2.2.1. Volumetric Characterization

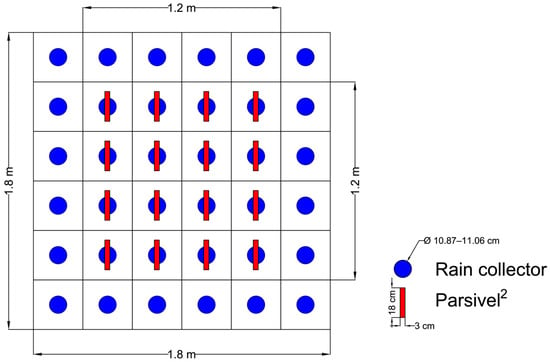

The volumetric calibration was focused on a rectangular sampling area of 1.8 m × 1.8 m (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the volumetric and disdrometric characterization method. All 36 rain collectors were contemporarily employed in the 1.8 m × 1.8 m wetted area, while a single Parsivel2 disdrometer was alternatively positioned at the center of each of the 16 measuring surfaces of the 1.2 m × 1.2 m wetted area.

Since the floor is composed of regular square tiles measuring 0.3 × 0.3 m, the characterization was performed by placing rain collectors at the center of each of the 36 tiles. Moreover, given the simulator’s configuration, characterized by a great falling height and high simulated rainfall intensities, concerns arose around the droplet impact potentially inducing splash phenomena. This could lead to water losses from within the collectors or, conversely, to additional inflow caused by droplets rebounding off the floor, thereby compromising the accuracy of volumetric measurements.

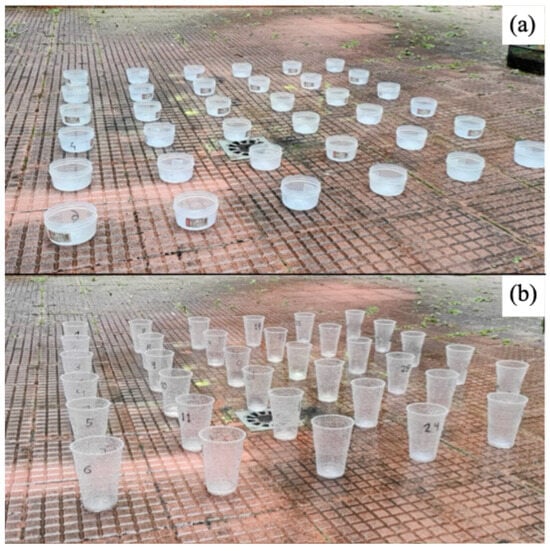

To address this issue, short plastic vessels (pv), with a capacity of 0.5 L and a sampling surface of 9.607 × 10−3 m2 (Figure 5a), and tall plastic cups (pc), with a capacity of 1 L and a sampling surface of 9.276 × 10−3 m2 (Figure 5b), were tested. For both rainfall collector types, the larger upper diameter was used to determine the effective sampling surface.

Figure 5.

Rain collectors used for the volumetric calibration: plastic vessels (a) and plastic cups (b).

The two distinct collector designs were employed to experimentally evaluate and quantify the potential error introduced by droplet splash (splash-in/splash-out), ensuring the robustness of the volumetric calibration.

In addition, a third calibration dataset was obtained using pcs across two successive rainfall simulation cycles to verify the temporal consistency of the simulator performance.

In other words, three different treatments (T) were employed: pv for 5 min (T1), pc for 5 min (T2), and pc for 10 min (T3). Due to their limited capacity, pvs could not be used for the 10 min simulation.

Before each rainfall simulation, pv and pc were calibrated using a digital scale. After the simulation, their outer surfaces were dried, and the collected water volume (Vol, L) was weighed. Knowing the volume collected by each collector, their sampling area (A, m2), and the simulation time (tS, h), the simulated rainfall intensity (Is, mm/h) was calculated as:

For each treatment, three repetitions were performed, leading to a total of 324 rainfall intensity measurements. To evaluate the rainfall spatial distribution of T1, T2, and T3, the mean value of the three repetitions was considered to determine the CU coefficient according to Equation (1).

Moreover, the IS spatial distribution was also graphically evaluated using a geographic information system (GIS) software (QGIS, version 3.34.14-Prizren) by creating thematic maps, one for each treatment. To allow direct visual comparison among treatments, a fixed graduated color scale was applied, ranging from light yellow to dark red, to represent increasing rainfall intensity.

To determine whether the observed differences in terms of simulated rainfall intensity were statistically significant, a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with replication was performed. The analysis considered two factors: treatment (T1, T2, T3), which reflects variations in both collector type and simulated rainfall duration, and collector position within the simulator. That is, the ANOVA test determines whether the considered factors, either individually or through their interaction, are responsible for any statistically significant differences in terms of simulated rainfall intensity. Specifically, F-values and corresponding p-values were calculated for each main effect and for the interaction term, and these were compared against the critical F-values to assess significance. The analysis was conducted using a significance threshold of α = 0.05.

2.2.2. Disdrometric Characterization

Regarding the disdrometric characterization, a 1.2 m × 1.2 m wetted area was considered (Figure 4). This focus was selected because the previous volumetric calibration suggested that the central 1.2 m × 1.2 m plot provided the most consistent and uniform rainfall distribution. Thus, the Parsivel2 disdrometer was placed at the center of each of the resulting 16 tiles (Figure 4).

For each position, three 5 min rainfall cycle repetitions were performed, resulting in a total of 240 1 min raw PSVD.

For each minute, rain intensity was determined using the following relationship:

in which t (s) is the sampling time, equal to 60 s for the present investigation, Di (mm) is the mean diameter of the i-th diameter class, ni (−) is the number of drops recorded in the i-th class, and σeff (mm2) is the effective sampling area that accounts for the margin faller effect. This means that, to account for the undercounting of drops falling near the laser-beam edges, a correction was applied to the nominal Parsivel2 sampling area (5400 mm2), according to the following relationship [79,84,105,106]:

where L (mm) and W (mm) are the Parsivel2 laser beam length and width, respectively, which are equal to 180 mm and 30 mm, and N (−) is the total number of drops recorded during the 1 min interval.

Regarding the rainfall kinetic power and momentum, each raw PSVD was processed as follows for their determination:

in which ρ (kg/m3) is the water density, equal to 1000 kg/m3, vj (m/s) is the mean fall velocity of the j-th velocity class, and nij is the number of drops recorded in the i-th and j-th class.

The mean IP, Pn, and M values of each position were employed to determine the spatial uniformity of the measured variables, according to Equation (1). Also, similarly to what was described in Section 2.2.1, the same procedure using a GIS software was followed to obtain thematic maps of the IP, Pn, and M spatial distributions.

The rainfall intensity values obtained from the volumetric characterization using rain collectors were compared with those derived from the disdrometric calibration. As the previous two-way ANOVA with replication (Section 2.2.1) revealed no significant differences among the volumetric treatments (T1, T2, and T3), their mean value, denoted as IT (mm/h), was used to represent the volumetric rainfall intensity.

To evaluate whether the RS was capable of generating raindrops resembling the terminal velocity of natural ones, an analysis of the measured fall velocity using the Parsivel2 disdrometer was conducted.

Specifically, at first, for each i-th diameter class of the Parsivel2 disdrometer, the weighted mean raindrop fall velocity measured with the Parsivel2 disdrometer, vP (m/s), relative to the entire dataset and thus independently of the sampled positions was obtained as follows:

Then, the resulting vP values were compared with the calculated fall velocities, V(D), derived from Equations (2)–(4).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Rainfall Intensity Spatial Distribution: Volumetric and Disdrometric Differences

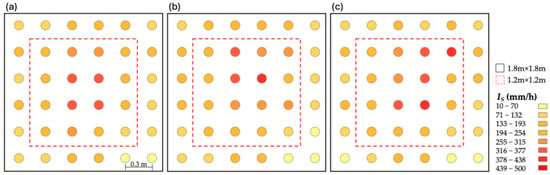

Figure 6 shows the spatial distribution of the rainfall intensity (IS) obtained from the three volumetric characterization treatments: T1 (Figure 6a), T2 (Figure 6b), and T3 (Figure 6c). Each circle represents the average rainfall intensity recorded at a specific sampling position, calculated from three repetitions per treatment.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of rainfall intensity (IS) for the three characterization treatments (T) employed in this investigation: T1 (a), T2 (b), and T3 (c).

The thematic maps reveal a certain degree of variability in rainfall intensity, with lower values observed in the peripheral zones and higher values concentrated in the central area. When comparing the full sampling area (1.8 m × 1.8 m) with a slightly reduced central portion (1.2 m × 1.2 m), the latter, despite exhibiting higher intensity values, shows improved spatial homogeneity.

This central concentration may be attributed to the simulator’s configuration: the 46 emitters, randomly oriented and alternately screwed in to reproduce a complex rainfall spectrum, may contribute more significantly to the central area, where drops from multiple emitters overlap, while the peripheral zones receive input from fewer emitters. As a result, the volumetric distribution is not perfectly uniform in the full sampling area.

These observations are supported by the data presented in Table 1, which reports, for each treatment, the mean IS value, standard deviation, and CU coefficient calculated according to Equation (1), for both the full and reduced sampling areas.

Table 1.

Mean rainfall intensity (IS), standard deviation, and Christiansen uniformity (CU) coefficient (CU) for the three characterization treatments (T) employed in this investigation, evaluated in both the 1.8 m × 1.8 m and the 1.2 m × 1.2 m sampling surfaces.

The analysis reveals that the simulator delivers, on average, a nearly constant rainfall intensity across treatments (Table 1), considering both the full and reduced sampling areas. However, the RS shows noticeable spatial differences within the full sampling area (CU from 56% to 62%), but improved uniformity across the 1.2 m × 1.2 m one (CU from 68% to 80%).

These results indicate that, within the full wetted area, the RS exhibits poor uniformity according to ASABE standards [56]. However, when considering only the central portion (Figure 6), the simulator reaches a 70% threshold across all treatments (mean CU equal to 75.16%) and even approaches 80% in T1 and T2, a threshold commonly adopted as a benchmark for uniformity in small-scale experiments [10,11,57,58] (Table 1).

Although measuring two rainfall cycles might intuitively seem to reduce variability, T3 shows the highest variability (Figure 6c), the lowest CU values, and the highest standard deviations (Table 1), indicating the presence of more extreme intensity values. This is likely not due to manual interventions (the system runs continuously under Arduino control), but rather to nonstationary effects inherent to the simulator during its operation.

To further investigate whether significant statistical differences exist between the employed treatments (effect 1) and the position of the rain collectors (effect 2, accounting for the spatial distribution), a two-factor ANOVA was performed. The results in terms of sum of squares (SQ), degrees of freedom (df), mean squares (MQ), F-value, p-value, and F-critical are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Two-factor ANOVA investigating whether significant statistical differences exist between the three employed characterization treatments and the rain collector positions.

The results of the two-factor ANOVA show highly significant differences due to rain collector position (F-value > F-critical; p < 0.001), demonstrating spatial heterogeneity to represent the primary source of variability in rainfall intensity. In contrast, treatment effect, assessing differences due to collector type and simulation duration, is not statistically significant (F-value < F-critical; p = 0.96), indicating that rainfall intensity does not change appreciably among treatments.

Considering the previous results, rainfall intensity at each position can be expressed as a single representative value, IT, obtained by averaging the results from the three different treatments.

Furthermore, to exclude positions less relevant from an erosive point of view, thus characterized by lower rainfall intensity values, and to characterize a more uniform pattern of the simulator from a disdrometric standpoint, the outer positions of the 1.8 m × 1.8 m pattern were excluded from subsequent analyses. Thus, only the central 1.2 m × 1.2 m wetted area was considered (Figure 6). For each of the 15 1 min PSVD measurements recorded using the Parsivel2 disdrometer, Equation (6) was applied to compute the corresponding rainfall intensity value, and the mean IP value was then obtained by averaging these 15 values.

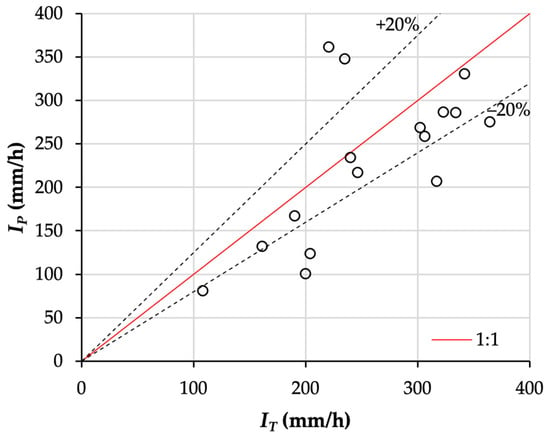

To assess the agreement between the two measurement methods, the (IT, IP) pairs corresponding to each fixed sampling position were plotted in Figure 7, in which the solid line indicates the perfect agreement (1:1), while the dashed lines indicate the ±20% error boundaries.

Figure 7.

Comparison between simulated rainfall intensity measured with rain collectors (IT) and that measured using a Parsivel2 disdrometer (IP).

Overall, the Parsivel2 disdrometer appears to underestimate rainfall intensity compared with the rain collectors. Indeed, 87.5% of the measures lie below the 1:1 line (Figure 7), and 43.75% of the points exhibit errors greater than or equal to 20%. This result is consistent with those found in literature [81], where a general underestimation of rainfall intensity using the Parsivel2 is detected and variance between identical Parsivel2 devices increases significantly with precipitation intensity. Furthermore, many authors [79,84,105,106,107] have reported that underestimation in rainfall intensity can be attributed to instrumental errors, including margin fallers—raindrops pass only partially through the sensor’s laser beam and are thus misclassified as smaller drops—and double detection—a single large drop is erroneously registered as two or more separate smaller drops.

However, it is important to note that the measurement surfaces are not identical: the disdrometer measures intensity over a rectangular area of 54 cm2, whereas the rain collectors cover circular areas of 92.76 cm2 (pv) and 96.07 cm2 (pc).

Therefore, the observed discrepancies between IT and IP can be explained by the expected underestimation under extreme rainfall intensity conditions, the differences in the real measurement surfaces, and the fair spatial uniformity exhibited by the simulator.

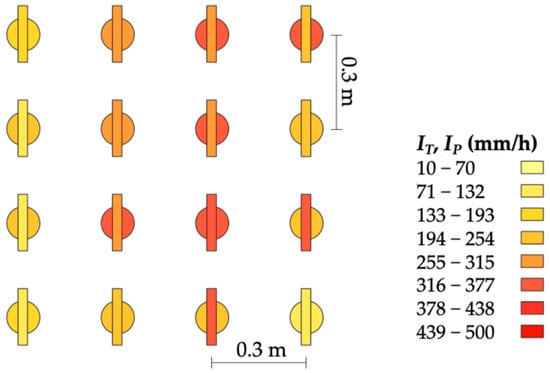

To further deepen the analysis on the differences between the two measurement methods, spatial distribution of rainfall intensity obtained using both rain collectors (IT) and a Parsivel2 (IP) is shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of simulated rainfall intensity in a 1.2 m × 1.2 m sampling surface, obtained using rain collectors (IT) and a Parsivel2 disdrometer (IP).

The coherent spatial overlay of the position of the rain collectors and the disdrometer, combined with consistent color coding, enables immediate visual comparison between the two measurement methods. This facilitates the identification of areas with similar rainfall intensities, the detection of extreme events, and a first evaluation of the spatial distribution captured by the disdrometer. Specifically, similar rainfall intensity values were recorded in only a few positions and, compared with the rain collector data, the intensities measured with the disdrometer appear less uniformly distributed.

To quantitatively assess the uniformity of the simulated rainfall based on the full dataset from both rain collectors and disdrometric measurements, the CU coefficient was calculated using Equation (1). Notwithstanding similar mean rainfall intensities, equal to 255.8 mm/h (rain collectors) and 229.6 mm/h (disdrometer), the volumetric method yielded a CU of 75.7%, while the disdrometric method resulted in a lower CU of 61.1%.

According to the ASABE classification [56], the RS in the 1.2 m × 1.2 m surface would be rated as fair (70% < CU < 80%) when evaluated using rain collectors and poor (60% < CU < 70%) when evaluated using the disdrometer.

These discrepancies are consistent with findings reported in literature, which highlight that the number, spatial arrangement, and physical characteristics of rainfall collectors, such as their size and shape, directly influence the representation of rainfall distribution over a plot surface [55].

3.2. Rainfall Kinetic Power and Momentum Spatial Distribution

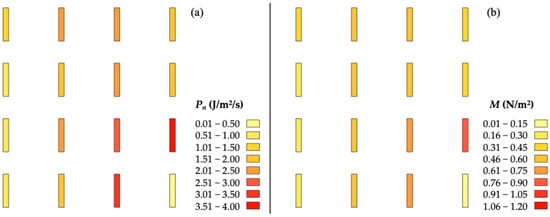

To evaluate the uniformity of the rainfall energy-related parameters, i.e., the rainfall kinetic power (Pn) and momentum (M), derived by applying Equations (8) and (9) to the disdrometer raw PSVD, their spatial distribution was analyzed. Figure 9 shows, for each sampled position, the mean Pn and M values of fifteen 1 min PSVD.

Figure 9.

The spatial distribution of the rainfall kinetic power (Pn) (a) and Momentum (M) (b) obtained using a Parsivel2 disdrometer.

Overall, the distribution of energetic parameters (Figure 9) mirrors the pattern previously observed for rainfall intensity (Figure 8), displaying a non-uniform spatial distribution within the wetted area of 1.2 m × 1.2 m. The rainfall momentum exhibits a higher degree of spatial uniformity compared to kinetic power, likely due to the quadratic dependence of the latter on fall velocity. Indeed, the uneven distribution of rainfall intensity reflects the non-uniform spatial pattern of the drop size distribution and the associated fall velocities. Thus, this variability in raindrop fall velocity is further amplified in the calculation of kinetic power.

Specifically, the RS discharges a mean Pn of 1.54 J/m2/s and a mean M of 0.39 N/m2 in the 1.2 m x 1.2 m sampled area, registering a CU coefficient, respectively, equal to 61.5% and 65.0%. These values reflect a level of spatial variability comparable to that observed for rainfall intensity (IP) (CU = 61.1%). Therefore, when assessed through disdrometric methods, the simulator exhibits poor uniformity [56] across the three metrics (IP, Pn, M).

3.3. Raindrop Fall Velocity

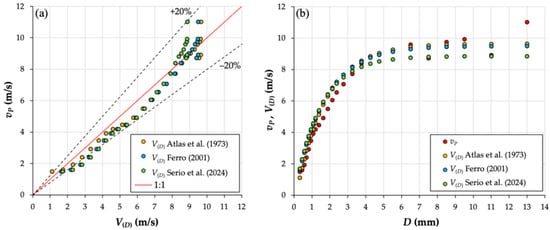

Given the 10 m drop falling height of the employed RS, raindrops are expected to reach terminal velocities comparable to those observed under natural precipitation conditions. To verify this, the weighted mean fall velocity for each diameter class, vP, measured with the Parsivel2 disdrometer was compared with the velocities V(D) calculated using empirical relationships from literature. Specifically, Equations (2) [89,90] and Equation (3) [97] represent typical fall velocities under natural rainfall conditions, while Equation (4) [49] was developed to estimate drop velocities in laboratory settings.

Figure 10 shows the comparison between the measured vP, derived from raw PSVDs using Equation (10), and the calculated V(D) relationships. In particular, Figure 10a displays vP versus V(D), with a 1:1 reference line and ±20% deviation bands, allowing visual assessment of the agreement between measured and predicted velocities. Figure 10b illustrates the variation in both vP and V(D) as a function of drop diameter.

Figure 10.

Comparison between weighted mean velocity measured with the Parsivel2 disdrometer, vP, and calculated, V(D), raindrop fall velocity (a); variation in both vP and V(D) as a function of drop diameter, D (b).

Generally, the agreement between experimental measurements and empirical relationships demonstrates the

Effectiveness of the RS system in generating drops that fall at velocities consistent with terminal conditions, as evidenced by the close alignment between measured and predicted values (Figure 10a,b). However, the Parsivel2 tends to underestimate fall velocities compared with all the tested empirical relationships, consistently with what has been observed in natural precipitation events [79].

Moreover, Equation (4) results applicable for predicting the fall velocity of simulated raindrops under the present experimental conditions, despite having been previously validated only for drip-type simulators with limited drop heights [49] (Figure 10a,b). The points of Atlas et al. [89] fall entirely within the ±20% error band, while those of Ferro [99] and Serio et al. [49] show greater errors, between 2 m/s and 4 m/s (Figure 10a).

Furthermore, for smaller diameters (D < 3 mm), the Parsivel2 shows a general tendency to slightly underestimate the fall velocity compared with the values calculated using literature-based relationships. Conversely, for larger diameters (D > 3 mm), all the empirical models accurately describe the velocity of the simulated raindrops (Figure 10b), with greater uncertainty for diameter values above 6 mm. These results are consistent with the findings by Luo et al. [108], who reported that the Parsivel2 exhibited a slight negative bias in mean fall velocity for the 1.375–2.75 mm diameter range, while showing a positive bias for drops exceeding 5.5 mm in diameter.

It is worth noticing also that the empirical relationships tend toward an asymptotic value of approximately 9–10 m/s (Figure 10a,b), which is consistent with the maximum velocities observed in nature for drops of around 6–8 mm. In contrast, the Parsivel2 disdrometer recorded both unrealistically large drop diameters (up to 13 mm) and a maximum weighted mean fall velocity of 11.02 m/s (Figure 10a,b). These outliers may be attributed to coalescence phenomena induced by the simulation system, instrumental errors such as overlapping drops within the laser beam being interpreted as a single drop, or the limited fall height, which may prevent the onset of breakup processes typically observed in larger natural raindrops [109].

It is also important to consider that the velocity comparison in Figure 10 is presented per fixed diameter class, without accounting for the relative abundance of drops within each class, as the goal was to assess whether the agreement between measured and calculated velocities holds consistently across the full range of drop sizes. However, such an evaluation must be weighted by the actual frequency of occurrence of each diameter class. Specifically, in the present dataset, approximately 99.9% of all simulated raindrops fall within the diameter range of 0.31 mm to 6.50 mm. Consequently, discrepancies observed at larger diameters may have limited practical relevance, given their negligible contribution to the overall drop population.

3.4. Broader Implications and Future Applications

The RS characterized here is being currently applied to investigate the erosive effects of precipitation on stone-based heritage surfaces [20,102]. Nevertheless, the comprehensive characterization presented in this study using volumetric methods and disdrometric technics extends its potential far beyond this specific research field. Indeed, the detailed assessment of rainfall intensity, kinetic energy, and momentum, as well as their spatial distribution and the information regarding fall velocity provide a complete description of the simulated rainfall regime, therefore allowing the use of this simulator for a wide range of hydrological and erosive research topics.

Specifically, we recommend the 1.2 m × 1.2 m as the maximum sample size for experiments requiring the highest level of accuracy and fully controlled rainfall parameters. When testing samples that exceed this size, the characteristics for the area beyond this 1.2 m × 1.2 m plot must be evaluated relying only on the calibration data derived from the rain collectors, which cover the larger area, or spatially interpolating the disdrometer data to the unmeasured zones, while acknowledging the associated uncertainties that this estimation process introduces.

Moreover, since the selected sampling procedure can substantially influence the results of the simulator characterization, standardization of sampling procedures is of paramount importance and must combine different characterization methodologies for a more robust and comprehensive analysis.

However, in light of the results presented in this work, future research should aim to enhance the spatial uniformity of simulated rainfall and to standardize the protocol for a more robust and reliable comparison between events, thereby enhancing the overall reproducibility and applicability of the simulator for comparative studies.

4. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive characterization of a laboratory RS originally designed to reproduce the erosive effects of high-intensity rainfall on heritage materials. The integrated use of volumetric and disdrometric techniques allowed for a detailed evaluation of the simulator’s hydrological and energetic performance, confirming its ability to realistically simulate the erosive effects of precipitation by achieving natural-like drop velocities and, therefore, kinetic energy and momentum.

The volumetric calibration, performed using different collector types and sampling durations, demonstrated that the simulator delivers consistent average rainfall intensities, but exhibits marked spatial variability over the entire wetted area. However, the CU coefficient improved up to nearly 80% within the central area.

Conversely, the analysis of the spatial distribution of rainfall intensity, kinetic power, and momentum obtained with a Parsivel2 disdrometer within the same central area revealed poor uniformity.

Disdrometric measurements also confirmed the simulator’s ability to generate raindrops able to achieve velocities comparable to those predicted by empirical relationships for natural rainfall, confirming its reliability in reproducing realistic fall dynamics even under limited falling height conditions.

Future research should aim to enhance the spatial uniformity of simulated rainfall and provide deeper insight into the physical realism of simulated precipitation, verifying whether the measured drop size distribution fits commonly used probabilistic functions such as gamma, Weibull, or lognormal.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G.C. and M.F.-R.; Methodology, R.C., M.A.S., F.G.C. and M.F.-R.; Software, G.B.-S.; Validation, R.C., M.A.S., F.G.C. and M.F.-R.; Formal Analysis, R.C., G.B.-S. and A.O.-M.; Investigation, R.C.; Resources, G.B.-S., A.O.-M. and M.F.-R.; Data Curation, R.C. and M.F.-R.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, R.C.; Writing—Review and Editing, R.C., M.A.S., G.B.-S., V.F. and M.F.-R.; Visualization, R.C., M.A.S., F.G.C. and V.F.; Supervision, G.B.-S. and M.F.-R.; Project Administration, R.C., G.B.-S. and M.F.-R.; Funding Acquisition, G.B.-S., F.G.C. and M.F.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support is acknowledged from Spanish MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and “ERDF A way of making Europe” by the European Union under project grant PID2023–147116OB-I00 (Nano shield 2.0) and by the “SiciliAn MicronanOTecH Research And Innovation Center” “SAMOTHRACE” (MUR, PNRR-M4C2, ECS_00000022, CUP B73C220081001), spoke 3—Università degli Studi di Palermo “S2-COMMs—Micro and Nanotechnologies for Smart & Sustainable Communities”.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The author R. C. gratefully acknowledges the hospitality and support provided by the University of León, specifically the Department of Chemistry and Applied Physics at the Industrial Engineering School, during his research stay. Moreover, the author R.C. also acknowledges the participation in the Erasmus+ Program (zero grant modality) of the University of Palermo (D.R. n. 848/2025). The authors want to thank Ángel Raga–Martín for his help in the experiments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

List of Symbols and Units

The following Symbols and Units are used in this manuscript:

| Symbol | Description | Unit |

| A | Rain collector sampling area | m2 |

| an | Coefficient of Equation (3) | cm |

| CU | Christiansen uniformity coefficient | % |

| D | Raindrop diameter | mm |

| Di | Mean diameter of the i-th diameter class | mm |

| h | Drop falling height | m |

| Ii | Rainfall intensity of a single rain collector | mm/h |

| IP | Rainfall intensity measured by the Parsivel2 disdrometer | mm/h |

| IS | Mean rainfall intensity | mm/h |

| IT | Mean rainfall intensity across the treatments T1, T2, and T3 | mm/h |

| L | Length of the Parsivel2 laser beam | mm |

| M | Rainfall momentum | N/m2 |

| N | Total number of drops in 1-min sampling time by the Parsivel2 disdrometer | (-) |

| nc | Number of collectors | (-) |

| nD | Number of diameter classes for which the disdrometer recorded velocities | (-) |

| ni | Number of drops in the i-th diameter class | (-) |

| nij | Number of drops in the i-th dimeter class and j-th velocity class | (-) |

| Pn | Rainfall kinetic power | J/m2/s |

| t | Sampling time for the disdrometric characterization | s |

| tS | Time of the simulation for the volumetric characterization | h |

| V(D) | Terminal fall velocity of raindrops according to literature relationships | m/s |

| vj | Mean fall velocity if the j-th velocity class | m/s |

| Vn | Coefficient of Equation (3) | m/s |

| Vol | Water volume sampled by rain collectors | L |

| vP | Mean raindrop fall velocity recorded by Parsivel2 for each i-th diameter class | m/s |

| W | Width of the Parsivel2 laser beam | mm |

| σeff | Effective sampling area of the Parsivel2 disdrometer | mm2 |

| ρ | Water density | Kg/m3 |

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| ASABE | American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers |

| ASTM | Advancing Standards Transforming Markets |

| df | Degree of freedom |

| GIS | Geographical iformation system |

| LPM | Laser Precipitation Monitor |

| MQ | Mean square |

| Parsivel | Particle Size Velocity |

| pc | Plastic cups |

| PSVD | Particle Size and Velocity Distribution |

| pv | Plastic vessels |

| RS | Rainfall simulator |

| SQ | Sum of square |

| T | Treatment for the volumetric characterization of the rainfall simulator |

References

- Cerdá, A. Simuladores de Lluvia y Su Aplicación a La Geomorfología: Estado de La Cuestión. Cuad. Investig. Geográfica 1999, 25, 45–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkerley, D. Rainfall Drop Arrival Rate at the Ground: A Potentially Informative Parameter in the Experimental Study of Infiltration, Soil Erosion, and Related Land Surface Processes. Catena 2021, 206, 105552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.D. Rainfall Simulators for Soil Conservation Research. In Soil Erosion Research Methods; Lal, R., Ed.; Soil & Water Conservation Societ: Ankeny, IA, USA, 1988; pp. 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, I.D.; Hirschi, M.C.; Barfield, B.J. Kentucky Rainfall Simulator. Trans. ASAE 1983, 26, 1085–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphry, J.B.; Daniel, T.C.; Edwards, D.R.; Sharpley, A.N. A Portable Rainfall Simulator for Plot-Scale Runoff Studies. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2002, 18, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lora, M.; Camporese, M.; Salandin, P. Design and Performance of a Nozzle-Type Rainfall Simulator for Landslide Triggering Experiments. Catena 2016, 140, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, L.D. Rainfall Simulators for Soil Erosion Research. In Soil Erosion Research Methods; Lal, R., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1994; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Iserloh, T.; Ries, J.B.; Arnáez, J.; Boix-Fayos, C.; Butzen, V.; Cerdà, A.; Echeverría, M.T.; Fernández-Gálvez, J.; Fister, W.; Geißler, C.; et al. European Small Portable Rainfall Simulators: A Comparison of Rainfall Characteristics. Catena 2013, 110, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, Y.; Albergel, J.; Pépin, Y.; Asseline, J.; Nasri, S.; Zante, P.; Berndtsson, R.; El-Niazy, M.; Balah, M. Comparison between Rainfall Simulator Erosion and Observed Reservoir Sedimentation in an Erosion-Sensitive Semiarid Catchment. Catena 2002, 50, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iserloh, T.; Fister, W.; Seeger, M.; Willger, H.; Ries, J.B. A Small Portable Rainfall Simulator for Reproducible Experiments on Soil Erosion. Soil Tillage Res. 2012, 124, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhaske, S.N.; Pathak, K.; Basak, A. A Comprehensive Design of Rainfall Simulator for the Assessment of Soil Erosion in the Laboratory. Catena 2019, 172, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serio, M.A.; Caruso, R.; Carollo, F.G.; Bagarello, V.; Ferro, V.; Nicosia, A. The Hydraulic Assessment of a New Portable Rainfall Simulator Using Different Nozzle Models. Water 2025, 17, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Murillo, J.F.; Nadal-Romero, E.; Regüés, D.; Cerdà, A.; Poesen, J. Soil Erosion and Hydrology of the Western Mediterranean Badlands throughout Rainfall Simulation Experiments: A Review. Catena 2013, 106, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouksey, A.; Lambey, V.; Nikam, B.; Aggarwal, S.; Dutta, S. Hydrological Modelling Using a Rainfall Simulator over an Experimental Hillslope Plot. Hydrology 2017, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, C.H.; Meyer, B.; Frede, H.G. A Portable Rainfall Simulator for Studying Factors Affecting Runoff, Infiltration and Soil Loss. Catena 1985, 12, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogden, C.B.; van Es, H.M.; Schindelbeck, R.R. Miniature Rain Simulator for Field Measurement of Soil Infiltration. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1997, 61, 1041–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulange, J.; Malhat, F.; Jaikaew, P.; Nanko, K.; Watanabe, H. Portable Rainfall Simulator for Plot-Scale Investigation of Rainfall-Runoff, and Transport of Sediment and Pollutants. Int. J. Sediment Res. 2019, 34, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abudi, I.; Carmi, G.; Berliner, P. Rainfall Simulator for Field Runoff Studies. J. Hydrol. 2012, 454–455, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simelane, M.P.Z.; Soundy, P.; Maboko, M.M. Effects of Rainfall Intensity and Slope on Infiltration Rate, Soil Losses, Runoff and Nitrogen Leaching from Different Nitrogen Sources with a Rainfall Simulator. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Raga, M.; Rodríguez, I.; Caldevilla, P.; Búrdalo, G.; Ortiz, A.; Martínez-García, R. Optimization of a Laboratory Rainfall Simulator to Be Representative of Natural Rainfall. Water 2022, 14, 3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, J.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, H.; Viles, H. A Controlled Field Experiment to Investigate the Deterioration of Earthen Heritage by Wind and Rain. Herit. Sci. 2019, 7, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N.; Sereenonchai, S.; Kongsurakan, P.; Hatano, R. Assessing Soil Organic Carbon, Soil Nutrients and Soil Erodibility under Terraced Paddy Fields and Upland Rice in Northern Thailand. Agronomy 2022, 12, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharali, B. Rate of Infiltration for Different Soil Textures Using Rainfall Simulator and Green–Ampt Model. ISH J. Hydraul. Eng. 2021, 27, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Li, G.; Mu, X.; Hou, W.; Ren, Y.; Yang, M. Effect of Raindrop Splashes on Topsoil Structure and Infiltration Characteristics. Catena 2022, 212, 106040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Raga, M.; Palencia, C.; Keesstra, S.; Jordán, A.; Fraile, R.; Angulo-Martínez, M.; Cerdà, A. Splash Erosion: A Review with Unanswered Questions. Earth Sci. Rev. 2017, 171, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo-Comino, J. Precipitation: Earth Surface Responses and Processes; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 9780128226995. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, H.; Unal, N.E.; Cokgor, S.; Gedikli, A.; Yoon, J.; Koca, K.; Inci, S.B.; Eris, E. A Rainfall Simulator for Laboratory-Scale Assessment of Rainfall-Runoff-Sediment Transport Processes over a Two-Dimensional Flume. Catena 2012, 98, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, A.N.; Somjunyakul, P.; Ok, J.; Watanabe, H. Rainfall-Runoff Simulation of Radioactive Cesium Transport by Using a Small-Scale Portable Rainfall Simulator. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2019, 230, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckley, C.S.; Branfireun, B. Simulated Rain Events on an Urban Roadway to Understand the Dynamics of Mercury Mobilization in Stormwater Runoff. Water Res. 2009, 43, 3635–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Kranz, W.L.; Shapiro, C.A.; Snow, D.D.; Bartelt-Hunt, S.L.; Mamo, M.; Tarkalson, D.D.; Zhang, T.C.; Shelton, D.P.; van Donk, S.J.; et al. Effect of Rainfall Timing and Tillage on the Transport of Steroid Hormones in Runoff from Manure Amended Row Crop Fields. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 324, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rončević, V.; Živanović, N.; Radulović, L.; Ristić, R.; Sadeghi, S.H.; Fernández-Raga, M.; Prats, S.A. Design, Calibration, and Performance Evaluation of a High-Fidelity Spraying Rainfall Simulator for Soil Erosion Research. Water 2025, 17, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, M.A.; Walsh, R.P.D. A Portable Rainfall Simulator for Field Assessment of Splash and Slopewash in Remote Locations. Earth Surf. Process Landf. 2007, 32, 2052–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lascelles, B.; Favis-Mortlock, D.T.; Parsons, A.J.; Guerra, A.J.T. Spatial and Temporal Variation in Two Rainfall Simulators: Implications for Spatially Explicit Rainfall Simulation Experiments. In Earth Surface Processes and Landforms; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; Volume 25, pp. 709–721. [Google Scholar]

- Boulal, H.; Gómez-Macpherson, H.; Gómez, J.A.; Mateos, L. Effect of Soil Management and Traffic on Soil Erosion in Irrigated Annual Crops. Soil Tillage Res. 2011, 115–116, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ries, J.B.; Iserloh, T.; Seeger, M.; Gabriels, D. Rainfall Simulations—Constraints, Needs and Challenges for a Future Use in Soil Erosion Research. Z. Fur Geomorphol. 2013, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Luz, C.C.; de Almeida, W.S.; de Souza, A.P.; Schultz, N.; Anache, J.A.A.; de Carvalho, D.F. Simulated Rainfall in Brazil: An Alternative for Assesment of Soil Surface Processes and an Opportunity for Technological Development. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 2024, 12, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grismer, M. Standards Vary in Studies Using Rainfall Simulators to Evaluate Erosion. Calif. Agric. 2012, 66, 102–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, F.G.; Serio, M.A.; Caruso, R. Rainfall Energy Characteristics of a Modified Kamphorst Simulator. In Biosystems Engineering Promoting Resilience to Climate Change—AIIA 2024—Mid-Term Conference; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guida, G.; Lucchese, A.; Nicosia, A.; Palmeri, V.; Pampalone, V.; Ferro, V. Effects of Bacteria Inoculation on Soil Hydrology and Erosion Processes of a Clay Loam Soil. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Agriculture and Forestry (MetroAgriFor), Padua, Italy, 29 October 2024; pp. 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, Z.; Ren, Z.; Xu, G.; Gao, H.; Xie, M.; Wang, P. Evaluating the Role of Hydrological and Sediment Connectivity in Runoff and Sediment Transfer on the Loess Plateau: An in-Situ Field Rainfall Experiment. J. Hydrol. 2025, 659, 133226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D6459-19; Advancing Standards Transforming Markets (ASTM) Test Method for Determination of Rolled Erosion Control Product (RECP) Performance in Protecting Hillslopes from Rainfall-Induced Erosion. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ricks, M.D.; Horne, M.A.; Faulkner, B.; Zech, W.C.; Fang, X.; Donald, W.N.; Perez, M.A. Design of a Pressurized Rainfall Simulator for Evaluating Performance of Erosion Control Practices. Water 2019, 11, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.; Faulkner, B.; Donald, W.N.; Perez, M.A. Comparison of Erosion Control Products Using an ASTM D6459 Rainfall Simulator: Insights and Suggestions. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2023, 149, 04023017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, C.J.W. Rainfall Simulator Construction and Evaluation of Erosion Control Practices. Master’s Thesis, Auburn University: Auburn, Alabama, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Midha, V.-K.; S, S.-K.; Sharma, A. Biodegradable Geomeshes for Rainsplash Erosion Control. J. Fiber Bioeng. Inform. 2017, 10, 155–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Johannsen, L.L.; Zambon, N.; Strauss, P.; Dostal, T.; Neumann, M.; Zumr, D.; Cochrane, T.A.; Klik, A. Impact of Disdrometer Types on Rainfall Erosivity Estimation. Water 2020, 12, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meshesha, D.T.; Tsunekawa, A.; Haregeweyen, N. Application of an Optical Disdrometer to Characterize Simulated Rainfall and Measure Drop-Size Distribution. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2018, 63, 1574–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, T.; Chifflard, P.; Aartsma, P.; Panten, K. A Review of the Characteristics of Rainfall Simulators in Soil Erosion Research Studies. MethodsX 2024, 12, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serio, M.A.; Carollo, F.G.; Caruso, R.; Ferro, V. Guidelines for the Energetic Characterization of a Portable Drip-Type Rainfall Simulator for Soil Erosion Research. Water 2024, 16, 2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, F.G.; Caruso, R.; Ferro, V.; Serio, M.A. Characterizing the Kamphorst Rainfall Simulator for Soil Erosion Investigations. J. Hydrol. 2024, 643, 132025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, R.R.; Wan Jaafar, W.Z.; Alengaram, U.J.; Hin, L.S. Overview of the Research Gaps in the Rainfall Simulator Study. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2023, 87, 1231–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isidoro, J.M.G.P.; Green, D.; Iserloh, T.; de Lima, J.L.M.P.; Pattison, I.; Marzen, M.; Silveira, A.; Stirling, R. Towards Harmonization in the Use of Rainfall Simulators—On the Pursuit of Better and More Comparable Experimental Results. In Proceedings of the 18th Biennial Conference of the Euromediterranean Network of Experimental and Representative Basins, Portoferraio, Italy, 7–10 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kibet, L.C.; Saporito, L.S.; Allen, A.L.; May, E.B.; Kleinman, P.J.A.; Hashem, F.M.; Bryant, R.B. A Protocol for Conducting Rainfall Simulation to Study Soil Runoff. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, 86, e51664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iserloh, T.; Isidoro, J.M.G.P.; de Lima, J.L.M.P.; Marzen, M.; de Lima, M.I.P.; Green, D.; Seeger, M.; Ries, J.B. Moving towards Harmonisation in Rainfall Simulation. In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly 2021, online, 19–30 April 2021. EGU21-5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.; Pattison, I. Christiansen Uniformity Revisited: Re-Thinking Uniformity Assessment in Rainfall Simulator Studies. Catena 2022, 217, 106424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers. Design and Installation of Microirrigation Systems; American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers: St. Joseph, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Esteves, M.; Planchon, O.; Lapetite, J.M.; Silvera, N.; Cadet, P. The ‘EMIRE’ Large Rainfall Simulator: Design and Field Testing. Earth Surf. Process Landf. 2000, 25, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, H.M.; Meselhy, A.A. A Portable Rainfall Simulator to Evaluate the Factors Affecting Soil Erosion in the Northwestern Coastal Zone of Egypt. Nat. Hazards 2021, 105, 2937–2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, S.; Abrahams, A.D.; Parsons, A.J. Sediment Sources and Sediment Transport by Rill Flow and Interrill Flow on a Semi-Arid Piedmont Slope, Southern Arizona. Catena 1993, 20, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavian, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Cerda, A.; Fallah, M.; Abdollahi, Z. Simulated Raindrop’s Characteristic Measurements. A New Approach of Image Processing Tested under Laboratory Rainfall Simulation. Catena 2018, 167, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Raga, M.; Cabeza-Ortega, M.; González-Castro, V.; Peters, P.; Commelin, M.; Campo, J. The Use of High-Speed Cameras as a Tool for the Characterization of Raindrops in Splash Laboratory Studies. Water 2021, 13, 2851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catari, G.; Latron, J.; Gallart, F. Assessing the Sources of Uncertainty Associated with the Calculation of Rainfall Kinetic Energy and Erosivity—Application to the Upper Llobregat Basin, NE Spain. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2011, 15, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Martínez, M.; Barros, A.P. Measurement Uncertainty in Rainfall Kinetic Energy and Intensity Relationships for Soil Erosion Studies: An Evaluation Using PARSIVEL Disdrometers in the Southern Appalachian Mountains. Geomorphology 2015, 228, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouline, S. Drop Size Distributions and Kinetic Energy Rates in Variable Intensity Rainfall. Water Resour. Res. 2009, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, F.G.; Serio, M.A.; Pampalone, V.; Ferro, V. Advances in a Measurement Method of Rainfall Kinetic Power and Momentum Affecting Soil Erosion Processes. Hydrol. Process 2024, 38, e15172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, F.G.; Caruso, R.; Di Stefano, C.; Ferro, V.; Pampalone, V.; Serio, M.A. Measurement Method of Rainfall Energetic Characteristics Using the Weibull Drop Size Distribution. J. Hydrol. 2026, 664, 134368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzinger, E.; Theel, M.; Windolph, H. Rainfall Amount and Intensity Measured by the Thies Laser Precipitation Monitor. In Proceedings of the TECO-2006, Geneva, Switzerland, 4–6 December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, T.J.; Fallgatter, C.; Shkurko, K.; Howlett, D. Fall Speed Measurement and High-Resolution Multi-Angle Photography of Hydrometeors in Free Fall. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2012, 5, 2625–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler-Mang, M.; Joss, J. An Optical Disdrometer for Measuring Size and Velocity of Hydrometeors. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2000, 17, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OTT Hydromet GmbH. Operating Instructions—Present Weather Sensor OTT Parsivel2; OTT Hydromet GmbH: Kempten, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Schönhuber, M.; Lammer, G.; Randeu, W.L. One Decade of Imaging Precipitation Measurement by 2D-Video-Distrometer. Adv. Geosci. 2007, 10, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, A.; Krajewski, W.F. Two-Dimensional Video Disdrometer: A Description. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2002, 19, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrů, J.; Kalibová, J. Measurement and Computation of Kinetic Energy of Simulated Rainfall in Comparison with Natural Rainfall. Soil Water Res. 2018, 13, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, M.; Zumr, D.; Kavka, P.; Laburda, T.; Lolk Johannsen, L.; Zambon, N.; Dostál, T.; Strauss, P.; Klik, A. Characterization of an Artificially Generated Rainfall Used for a Soil Erosion Research. Vodohospodářské Tech.-Ekon. Inf. 2019, 61, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gires, A.; Bruley, P.; Ruas, A.; Schertzer, D.; Tchiguirinskaia, I. Disdrometer Measurements under Sense-City Rainfall Simulator. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottenot, L.; Courtemanche, P.; Nouhou-Bako, A.; Darboux, F. A Rainfall Simulator Using Porous Pipes as Drop Former. Catena 2021, 200, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhao, V.G.; Pandey, A.; Mishra, S.K. Sediment Modeling Using Laboratory-Scale Rainfall Simulator and Laser Precipitation Monitor. Environ. Res. 2023, 237, 116859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosio, R.; Cagninei, A.; Poggi, D. Large Laboratory Simulator of Natural Rainfall: From Drizzle to Storms. Water 2023, 15, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo-Martínez, M.; Beguería, S.; Latorre, B.; Fernández-Raga, M. Comparison of Precipitation Measurements by OTT Parsivel 2 and Thies LPM Optical Disdrometers. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2018, 22, 2811–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frasson, R.P.d.M.; da Cunha, L.K.; Krajewski, W.F. Assessment of the Thies Optical Disdrometer Performance. Atmos. Res. 2011, 101, 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Raga, M.; Fraile, R.; Keizer, J.J.; Varela Teijeiro, M.E.; Castro, A.; Palencia, C.; Calvo, A.I.; Koenders, J.; Da Costa Marques, R.L. The Kinetic Energy of Rain Measured with an Optical Disdrometer: An Application to Splash Erosion. Atmos. Res. 2010, 96, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caracciolo, C.; Prodi, F.; Battaglia, A.; Porcu’, F. Analysis of the Moments and Parameters of a Gamma DSD to Infer Precipitation Properties: A Convective Stratiform Discrimination Algorithm. Atmos. Res. 2006, 80, 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuki; Randeu, W.L.; Kozu, T.; Shimomai, T.; Hashiguchi, H.; Schönhuber, M. Raindrop Axis Ratios, Fall Velocities and Size Distribution over Sumatra from 2D-Video Disdrometer Measurement. Atmos. Res. 2013, 119, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, R.; Testik, F.Y. Assessment of OTT Parsivel2 Raindrop Fall Speed Measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2023, 40, 557–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adirosi, E.; Gorgucci, E.; Baldini, L.; Tokay, A. Evaluation of Gamma Raindrop Size Distribution Assumption through Comparison of Rain Rates of Measured and Radar-Equivalent Gamma DSD. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2014, 53, 1618–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raupach, T.H.; Berne, A. Correction of Raindrop Size Distributions Measured by Parsivel Disdrometers, Using a Two-Dimensional Video Disdrometer as a Reference. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2015, 8, 343–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adirosi, E.; Baldini, L.; Lombardo, F.; Russo, F.; Napolitano, F.; Volpi, E.; Tokay, A. Comparison of Different Fittings of Drop Spectra for Rainfall Retrievals. Adv. Water Resour. 2015, 83, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, R.; Kinzer, G.D. The Terminal Velocity of Fall For Water Droplets in Stagnant Air. J. Meteorol. 1949, 6, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, D.; Srivastava, R.C.; Sekhon, R.S. Doppler Radar Characteristics of Precipitation at Vertical Incidence. Rev. Geophys. 1973, 11, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlas, D.; Ulbrich, C.W. Path- and Area-Integrated Rainfall Measurement by Microwave Attenuation in the 1–3 Cm Band. J. Appl. Meteorol. 1977, 16, 1322–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beard, K.V. Terminal Velocity and Shape of Cloud and Precipitation Drops Aloft. J. Atmos. Sci. 1976, 33, 851–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serio, M.A.; Carollo, F.G.; Ferro, V. Raindrop Size Distribution and Terminal Velocity for Rainfall Erosivity Studies. A Review. J. Hydrol. 2019, 576, 210–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, C.; Cho, E.; Na, W.; Kang, M.; Lee, M. Change of Rainfall–Runoff Processes in Urban Areas Due to High-Rise Buildings. J. Hydrol. 2021, 597, 126155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, A. Proposal and Design a Comprehensive Framework to Provide Water and Energy from Rain and Precipitation. Water Resour. Ind. 2024, 32, 100263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, F.G.; Ferro, V. Modeling Rainfall Erosivity by Measured Drop-Size Distributions. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2015, 20, C4014006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carollo, F.G.; Ferro, V.; Serio, M.A. Estimating Rainfall Erosivity by Aggregated Drop Size Distributions. Hydrol. Process 2016, 30, 2119–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, V. Tecniche Di Misura e Monitoraggio Dei Processi Erosivi. In Quaderni di Idronomia Montana—Trasporto di Azcqua e Sedimenti a Scala di Versante; Bagarello, V., Ferro, V., Giordano, G., Eds.; Editoriale Bios: Cosenza, Italy, 2001; Volume 21/2, pp. 63–128. [Google Scholar]

- Laws, J.O. Measurements of the Fall-velocity of Water-drops and Raindrops. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1941, 22, 709–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, D.C. The Behavior of Water Drops at Terminal Velocity in Air. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1950, 31, 836–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epema, G.F.; Riezebos, H.T. Fall Velocity of Waterdrops at Different Heights as a Factor Influencing Erosivity of Simulated Rain. Catena Suppl. 1983, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jayawardena, A.W.; Rezaur, R.B. Drop Size Distribution and Kinetic Energy Load of Rainstorms in Hong Kong. Hydrol. Process 2000, 14, 1069–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, I.; Ortiz, A.; Caldevilla, P.; Giganto, S.; Búrdalo, G.; Fernández-Raga, M. Comparison between the Effects of Normal Rain and Acid Rain on Calcareous Stones under Laboratory Simulation. Hydrology 2023, 10, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, L.; Xi, Y.; Wei, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Xu, G.; Liu, Y. The Influence of Inorganic Salt on Coal-Water Wetting Angle and Its Mechanism on Eliminating Water Blocking Effect. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 2022, 103, 104618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-García, R.; González-Campelo, D.; Fraile-Fernández, F.J.; Castañón, A.M.; Caldevilla, P.; Giganto, S.; Ortiz-Marqués, A.; Zelli, F.; Calvo, V.; González-Domínguez, J.M.; et al. Performance Study of Graphene Oxide as an Antierosion Coating for Ornamental and Heritage Dolostone. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2300486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokay, A.; Wolff, D.B.; Petersen, W.A. Evaluation of the New Version of the Laser-Optical Disdrometer, OTT Parsivel2. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2014, 31, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraile, R.; Castro, A.; Fernández-Raga, M.; Palencia, C.; Calvo, A.I. Error in the Sampling Area of an Optical Disdrometer: Consequences in Computing Rain Variables. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 369450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-G.; Kim, H.-L.; Ham, Y.-W.; Jung, S.-H. Comparative Evaluation of the OTT PARSIVEL2 Using a Collocated Two-Dimensional Video Disdrometer. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2017, 34, 2059–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Wang, L.; Huo, T.; Chen, M.; Ma, J.; Li, S.; Wu, J. Raindrop Size Distribution and Rain Characteristics of the 2017 Great Hunan Flood Observed with a Parsivel2 Disdrometer. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruppacher, H.R.; Klett, J.D. Cloud Particle Interactions-Collision, Coalescence, and Breakup. In Microphysics of Clouds and Precipitation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1978; pp. 464–503. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).