Optimization of the Fe0/H2O2/UV Photo-Fenton Process for Real Textile Wastewater via Response Surface Methodology

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Systems

2.2. Determination of Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD, mg L−1)

2.3. Sample Lyophilization

2.4. Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy Analysis

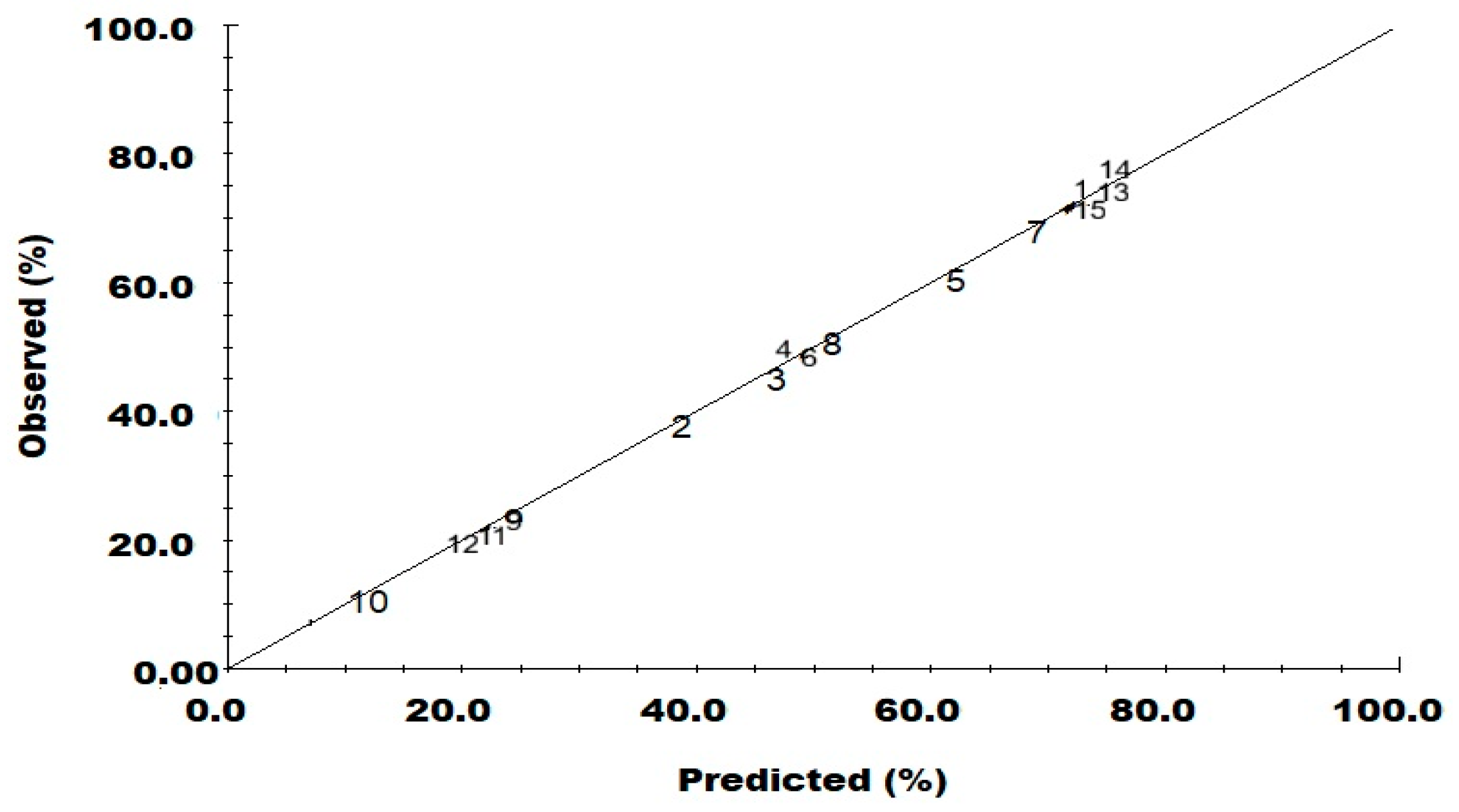

3. Results and Discussion

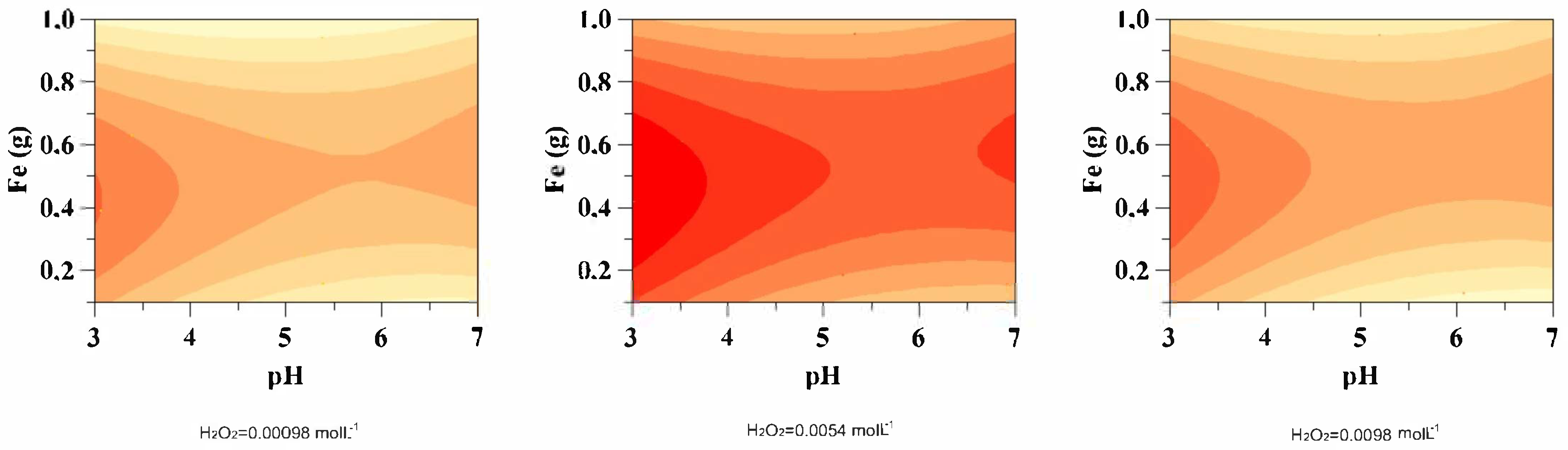

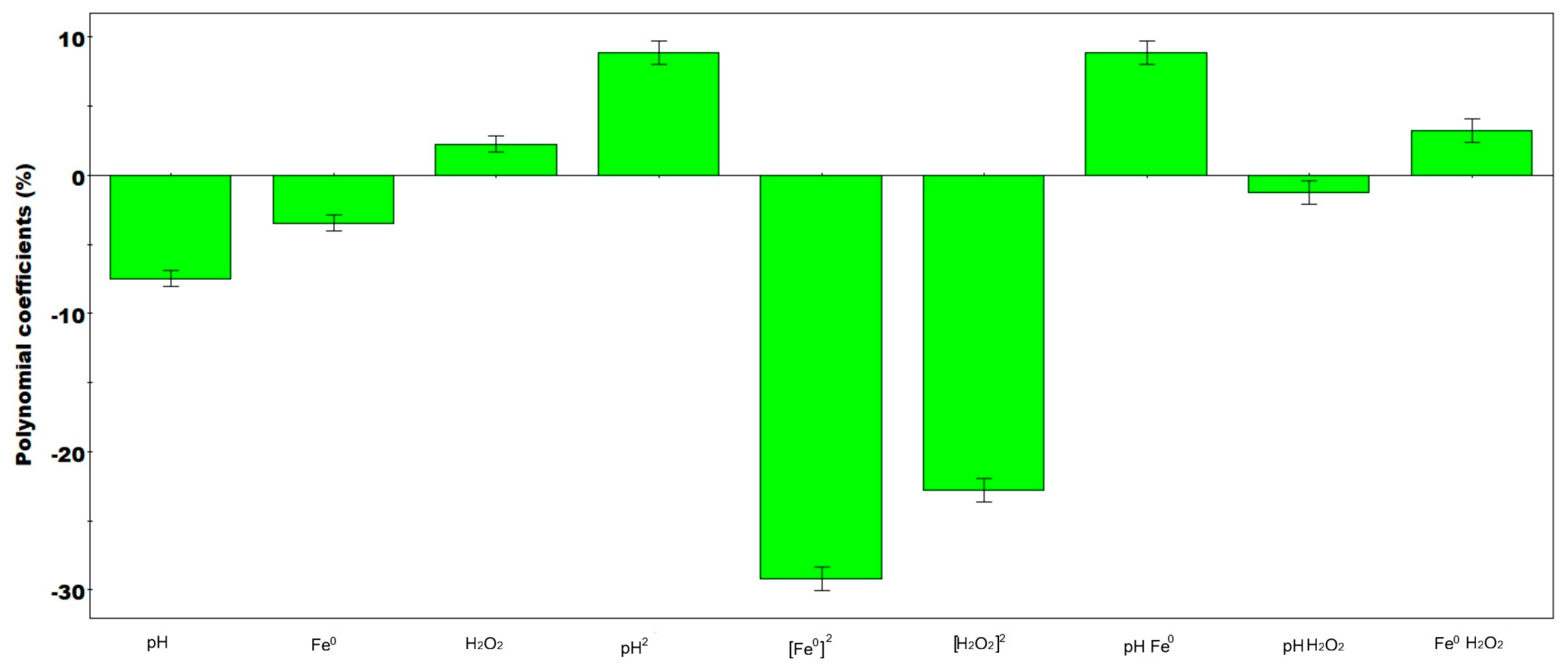

3.1. Effect of pH

3.2. Effect of Iron (Fe0)

3.3. Effect of Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2)

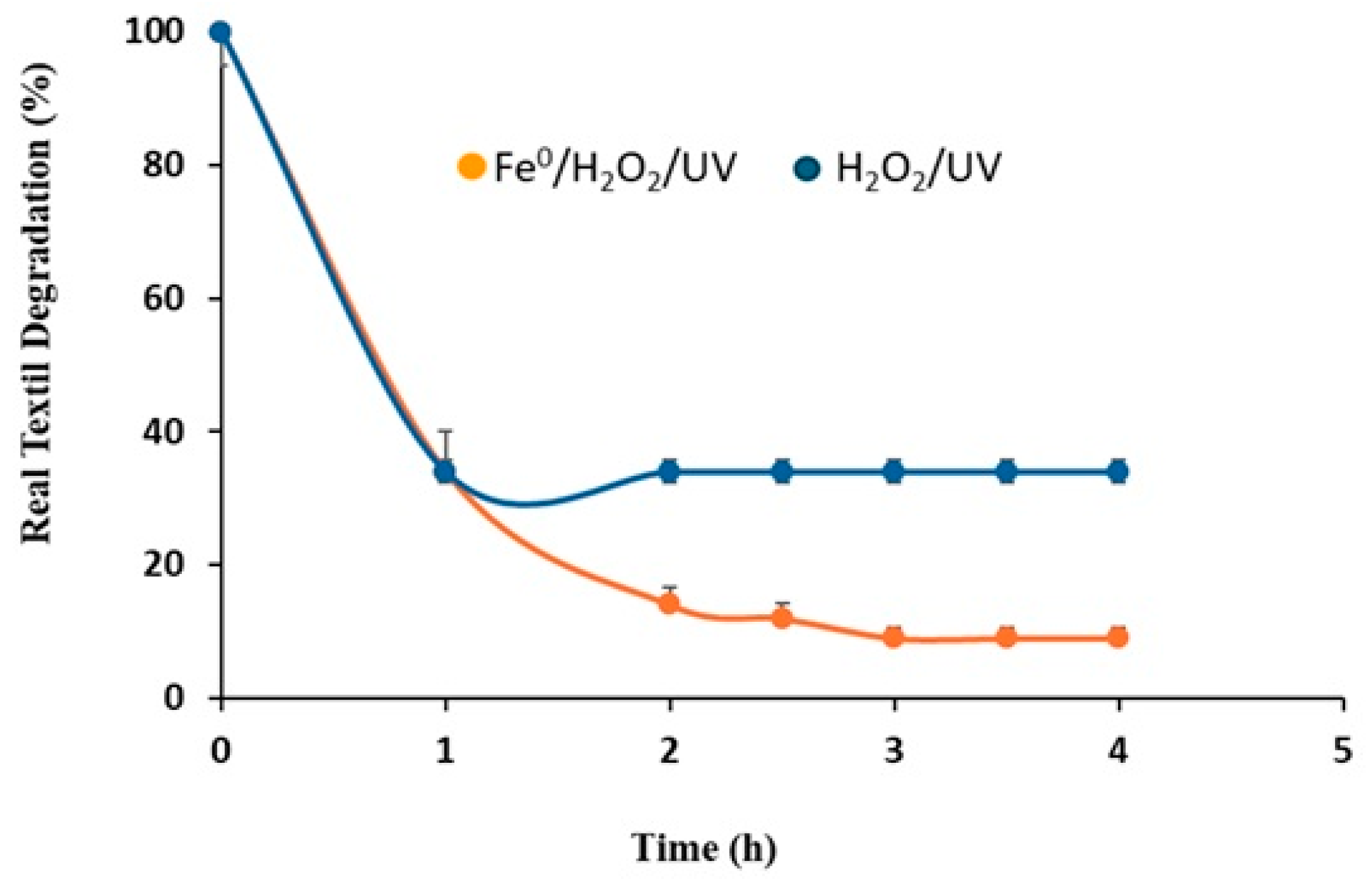

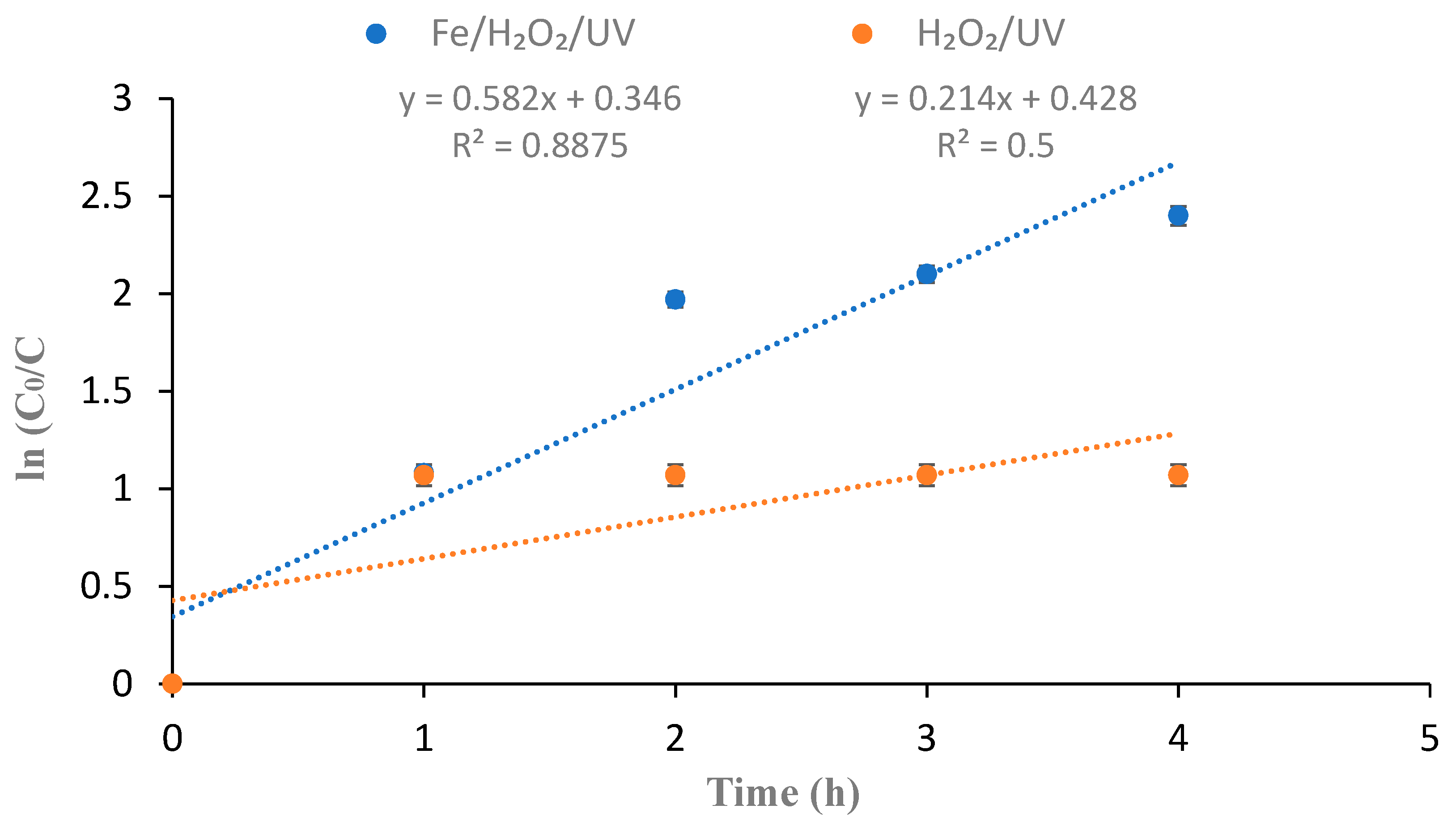

3.4. Reaction Mechanism and Role of UV Irradiation in Fe2+ Regeneration

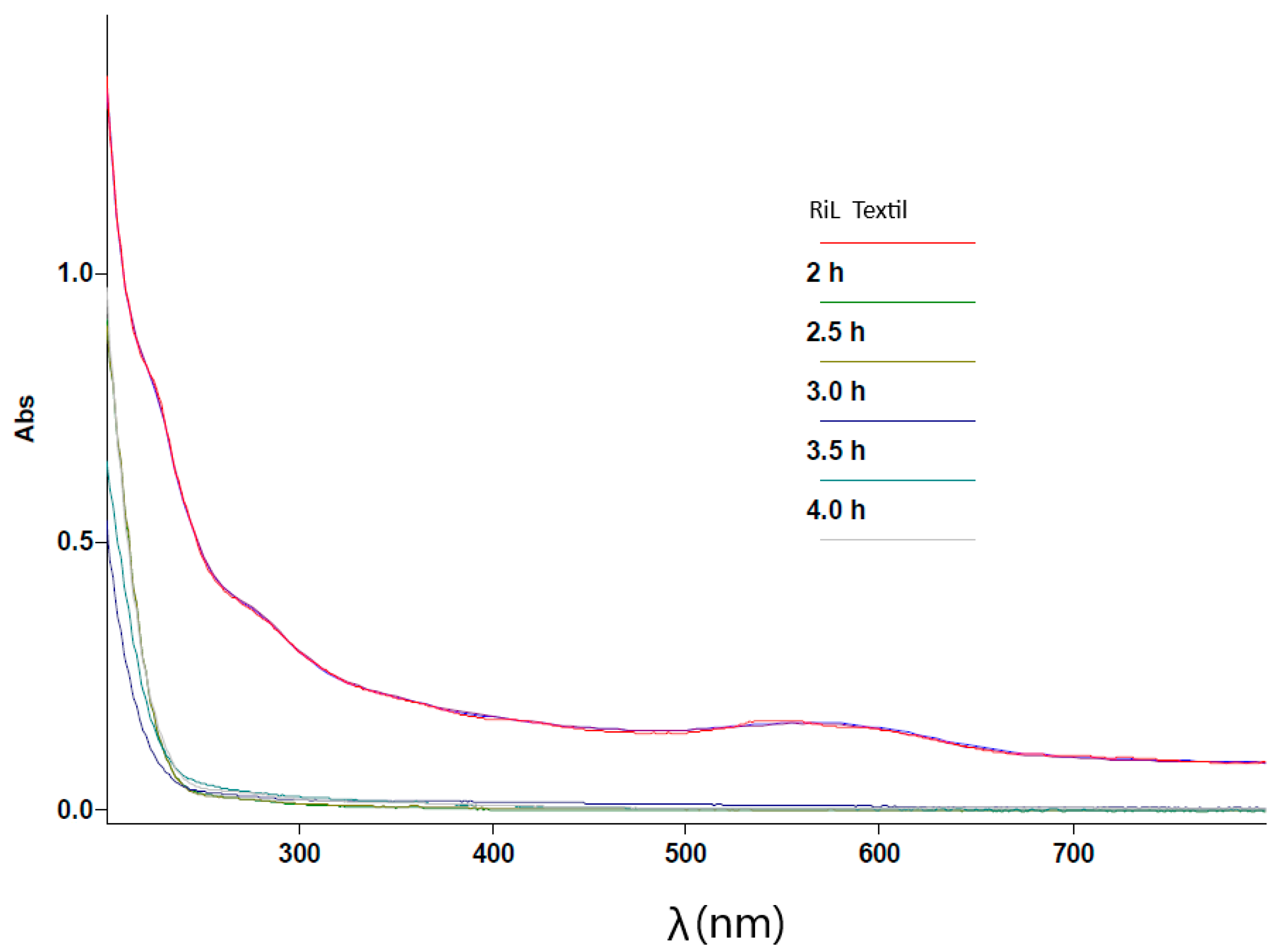

3.5. UV–Vis Spectral Evolution During the Degradation Process

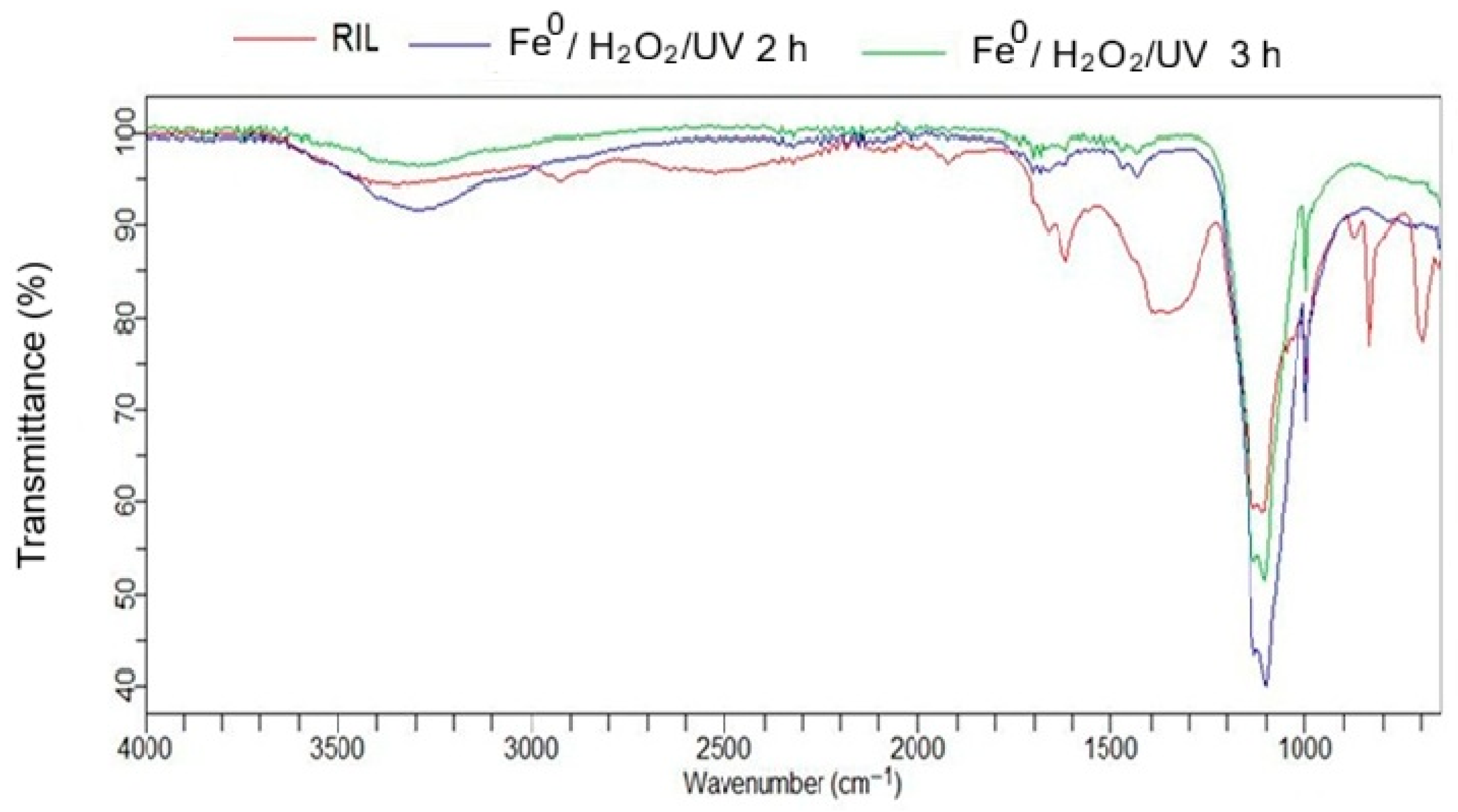

3.6. FTIR Spectral Analysis of Structural Changes After Treatment

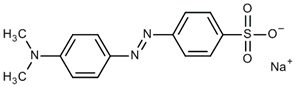

3.7. Correlation Between Molecular Structures and FTIR Spectral Features

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joseph, N.; Libunao, T.; Herrmann, E.; Bartelt-Hunt, S.; Propper, C.R.; Bell, J.; Kolok, A.S. Chemical Toxicants in Water: A GeoHealth Perspective in the Context of Climate Change. Geo Health 2022, 6, e2022GH0006752022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshamsi, A.M.O.; Tatan, B.M.; Ashoobi, N.M.S.; Mortula, M.M. Emerging pollutants of water supplies and the effect of climate change. Environ. Rev. 2023, 31, 256–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C. Biological Treatment of Water Contaminants: A New Insight. Water 2025, 17, 1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, G.; Ghaly, M.; Ahmed, G.; Mohamed, R.; El-Gawad, H.; Kowal, P.; Al-Hazmi, H.; Afify, A.A. Comprehensive Approach to Azo Dichlorotriazine Dye Treatment: Assessing the Impact of Physical, Chemical, and Biological Treatment Methods through Statistical Analysis of Experimental Data. Water 2024, 16, 1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrah, A.; AL-Zghoul, T.; Al-Qodah, Z. An Extensive Analysis of Combined Processes for Landfill Leachate Treatment. Water 2024, 16, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okut, N.; Hamzat, A.; Rajakaruna, A.; Asmatulu, E. Agricultural wastewater treatment and reuse technologies: A comprehensive review. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 69, 106699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameta, S. Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment. Emerging Green Chemical Technology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antiñolo, L.; Pascual, J.; Muñio, M.; Poyatos, J. Effectiveness of Advanced Oxidation Processes in Wastewater Treatment: State of the Art. Water 2021, 13, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, A.; Deivayanai, V.C.; Kumar, P.S.; Rangasamy, G.; Hemavathy, R.V.; Harshana, T.; Gayathri, N.; Alagumalai, K. A detailed review on advanced oxidation process in treatment of wastewater: Mechanism, challenges and future outlook. Chemosphere 2022, 308, 136524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capodaglio, A. Critical Perspective on Advanced Treatment Processes for Water and Wastewater: AOPs, ARPs, and AORPs. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, T.; Nawaz, R.; Al-Hussain, S.; Irfan, A.; Irshad, M.; Ahmad, S.; Zaki, M. Application of Advanced Oxidation Processes for the Treatment of Color and Chemical Oxygen Demand of Pulp and Paper Wastewater. Water 2023, 15, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaswan, V.; Kaur, H. A comparative study of advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment. Water Pract. Technol. 2023, 18, 1233–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odabasi, S.U.; Buyukgungor, H. Comparative study of degradation of pharmaceutical and personal care products in wastewater by advanced oxidation processes: Fenton, UV/H2O2, UV/TiO2. Clean Soil Air Water 2024, 52, 2300204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Shaad, K.; Vollmer, D.; Ma, C. Treatment of Textile Wastewater Using Advanced Oxidation Processes—A Critical Review. Water 2021, 13, 3515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhou, S.; Li, F.; Sun, L.; Lu, H. Ozone Micronano-bubble-Enhanced Selective Degradation of Oxytetracycline from Production Wastewater: The Overlooked Singlet Oxygen Oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 18550–18562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, G.; Kim, T.; Jeon, H.; Lee, G.; Jung, S.; Seo, S.; Jang, A. Pilot scale application of a hybrid process based on ozone and BAF process: Performance evaluation for livestock wastewater treatment in a real environment. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 66, 105989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wypart-Pawul, A.; Neczaj, E.; Grobelak, A. Advanced oxidation processes for removal of organic micropollutants from wastewater. Desalin. Water Treat. 2023, 305, 114–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metin, S.; Çifçi, D. Chemical industry wastewater treatment by coagulation combined with Fenton and photo-Fenton processes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2023, 98, 1158–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, B.M.; Zyadah, M.A.; Ali, M.Y.; El-Sonbati, M.A. Pre-treatment of composite industrial wastewater by Fenton and electro-Fenton oxidation processes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Ji, L.; Ma, Z.; Ren, Y.; Zhou, S.; Long, X.; Cao, C. Application of Photo-Fenton-Membrane Technology in Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Membranes 2023, 13, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincho, J.; Gomes, J.; Martins, R.; Domingues, E. Continuous Heterogeneous Fenton for Swine Wastewater Treatment: Converting an Industry Waste into a Wastewater Treatment Material. Water 2024, 16, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zheng, X.; Chen, Y. Municipal wastewater reclamation and reuse using membrane-based technologies: A review. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 224, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dansawad, P.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; You, S.; Li, W.; Yi, S. Machine learning toward improving the performance of membrane-based wastewater treatment: A review. Adv. Membr. 2023, 3, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, B.; Ersahin, M.; Ozgun, H.; Koyuncu, I. Pilot and full-scale applications of membrane processes for textile wastewater treatment: A critical review. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 42, 102172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethi, B.; Sonawane, S.H.; Bhanvase, B.; Sonawane, S.S. Textile Industry Wastewater Treatment by Cavitation Combined with Fenton and Ceramic Nanofiltration Membrane. Chem. Engin. Process-Process Intensif. 2021, 168, 108540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPA Method 410.4; The Determination of Chemical Oxygen Demand by Semi-Automated Colorimetry. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1993.

- US EPA Standard Methods 5220 D; Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD). American Public Health Association/American Water Works Association/Water Environment Federation: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- ISO 15705:2002; Water quality Determination of the Chemical Oxygen Demand Index (ST-COD) Small-Scale Sealed-Tube Method. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Çalık, Ç.; Çifçi, D. Comparison of kinetics and costs of Fenton and photo-Fenton processes used for the treatment of a textile industry wastewater. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, T.; Ghosh, P. Photo-Fenton remediation of textile wastewater in fluidized-bed reactor using modified laterite: Hydrodynamic study and effect of operating parameters. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 473, 145324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atmaca, K. Comparative Investigation of COD and Color Removal from Real Textile Wastewater by Electro-Fenton and Photo-Electro-Fenton Methods: The Effect of Operational Parameters and Cost Analysis. Int. J. Chem. Eng. 2025, 2025, 9248366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, N.; Sönmez, G. Removal of COD and Color from Textile Wastewater by the Fenton and UV/H2O2 Oxidation Processes and Optimization. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2023, 234, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.; Santana, C.; Velloso, C.; da Silva, A.; Magalhães, F.; Aguiar, A. A review on the treatment of textile industry effluents through Fenton processes. Process Saf. Environ. 2021, 155, 366–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawaz, M.; Fida, S.; Javed, T.; Numan, F.; Choudhary, L.; Saleem, M.; Pervez, S. Removal of NOVACRON® red C-4B reactive dye from textile industry wastewater by the UV/H2O2-assisted advanced oxidation process. Water Pract. Technol. 2024, 19, 3794–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, K.; Fiaschitello, T.; Labuto, G.; Freeman, H.; Fragoso, W.; da Costa, S.; da Costa, A. Reuse of water from real reactive monochromic and trichromic wastewater for new cotton dyes after efficient treatment using H2O2 catalyzed by UV light. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurs, E.; Morshed, M.N.; Kahoush, M.; Kadi, N. Study on Fenton-based discoloration of reactive-dyed waste cotton prior to textile recycling. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, R.; Yasar, A.; Nizami, A.; Tabinda, A. Integration of physical and advanced oxidation processes for treatment and reuse of textile dye-bath effluents with minimum area footprint. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 383, 135366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, M.; Singh, S.; Pathak, S.; Kasaudhan, J.; Mishra, A.; Bala, S.; Garg, D.; Singh, R.; Singh, P.; Kumar, P.; et al. Recent Strategies for the Remediation of Textile Dyes from Wastewater: A Systematic Review. Toxics 2023, 11, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadioglu, E.N.; Öztürk, H.; Eroglu, H.A.; Akbal, F.; Kuleyin, A.; Özkaraova, E.B. Artificial neural network modeling of Fenton-based advanced oxidation processes for recycling of textile wastewater. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 136, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobczak, M.; Bujnowicz, S.; Bilinska, L. Fenton and electro-Fenton treatment for industrial textile wastewater recycling. Comparison of by-products removal, biodegradability, toxicity, and re-dyeing. Water Resour. Ind. 2024, 31, 100256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thampraphaphon, B.; Phosri, C.; Pisutpaisal, N.; Thamvithayakorn, P.; Chotelersak, K.; Sarp, S.; Suwannasai, N. High Potential Decolourisation of Textile Dyes from Wastewater by Manganese Peroxidase Production of Newly Immobilised Trametes hirsuta PW17-41 and FTIR Analysis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamand, D.; Muhammad, D.; Aziz, S.; Hama, P.; Al-Asbahi, B.; Ahmed, A.; Hassan, J. Enhanced optical properties of chitosan polymer doped with orange peel dye investigated via UV–Vis and FTIR analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, S.; Yao, P.; Zhu, X.; Lei, X.; Xing, T.; Chena, G. Degradation of textile dyes from aqueous solution using tea-polyphenol/Fe loaded waste silk fabrics as Fenton-like catalysts. RSC Adv. 2021, 14, 8290–8305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafez, T.; Radwan, E.; Sayed, G.; Khatib, E.; Nasr, M.; Gabry, L. Removal of acid and basic dyes from textile wastewater using modified acrylic fibres waste as an efficient adsorbent. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Experiment Name | Run Order | pH | Fe0 (g) | H2O2 (mL) | Aromatic Ring Removing (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | 3 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.55 (0) | 70.1 |

| 2 | 2 | 7 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.55 (0) | 37.3 |

| 3 | 7 | 3 (−1) | 1.0 (+1) | 0.55 (0) | 44.7 |

| 4 | 12 | 7 (+1) | 1.0 (+1) | 0.55 (0) | 47.4 |

| 5 | 6 | 3 (−1) | 0.55 (0) | 0.1 (−1) | 59.9 |

| 6 | 14 | 7 (+1) | 0.55 (0) | 0.1 (−1) | 47.4 |

| 7 | 15 | 3 (−1) | 0.55 (0) | 1.0 (+1) | 67.5 |

| 8 | 4 | 7 (+1) | 0.55 (0) | 1.0 (+1) | 50.2 |

| 9 | 10 | 5 (0) | 0.1 (−1) | 0.1 (−1) | 22.6 |

| 10 | 1 | 5 (0) | 1.0 (+1) | 0.1 (−1) | 10.0 |

| 11 | 9 | 5 (0) | 0.1 (−1) | 1.0 (+1) | 20.0 |

| 12 | 11 | 5 (0) | 1.0 (+1) | 1.0 (+1) | 20.3 |

| 13 | 5 | 5 (0) | 0.55 (0) | 0.55 (0) | 70.1 |

| 14 | 3 | 5 (0) | 0.55 (0) | 0.55 (0) | 70.5 |

| 15 | 8 | 5 (0) | 0.55 (0) | 0.55 (0) | 70.0 |

| Source | DF | SS | MS (Variance) | F-Value | p-Value | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 15 | 53,201.50 | 3546.77 | - | - | - |

| Constant | 1 | 48,997.60 | 48,997.60 | - | - | - |

| Total Corrected | 14 | 4203.94 | 300.282 | - | - | 17.3286 |

| Regression | 9 | 4203.93 | 467.103 | 164,874 | 0.000 | 21.6126 |

| Residual | 5 | 0.0141654 | 0.00283308 | - | - | 0.0532267 |

| Lack of Fit | 3 | 0.00749924 | 0.00249975 | 0.749979 | 0.615 | 0.0499975 |

| Pure Error | 2 | 0.00666618 | 0.00333309 | - | - | 0.0577329 |

| Dye | Molecular Structure | IR Bands (cm−1) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| methyl orange |  | 1600–1500 (C=C aromatic) | [41,43,44] |

| 1450–1400 (C-N) | |||

| 1380–1360 (CH3) | |||

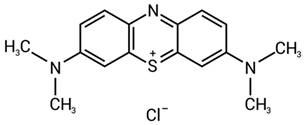

| methylene blue |  | 1600–1500 (C=C aromatic) | [41,43,44] |

| 1300–1200 (C-N) | |||

| 1400–1380 (CH3) | |||

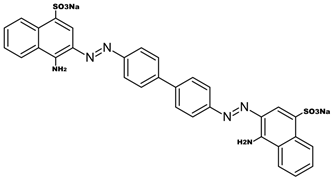

| Congo Red |  | 1600–1500 (C=C aromatic) | [41,43,44] |

| 1400–1300 (N=N) | |||

| 1200–1100 (S=O) | |||

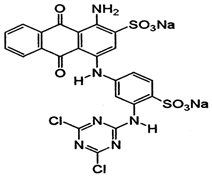

| Reactive Black 5 |  | 1600–1500 (C=C aromatic) | [41,43,44] |

| 1200–1100 (S=O) | |||

| 1050–950 (C=C) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yeber, M.C.; Paredes, B. Optimization of the Fe0/H2O2/UV Photo-Fenton Process for Real Textile Wastewater via Response Surface Methodology. Water 2025, 17, 3427. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233427

Yeber MC, Paredes B. Optimization of the Fe0/H2O2/UV Photo-Fenton Process for Real Textile Wastewater via Response Surface Methodology. Water. 2025; 17(23):3427. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233427

Chicago/Turabian StyleYeber, María C., and Bastian Paredes. 2025. "Optimization of the Fe0/H2O2/UV Photo-Fenton Process for Real Textile Wastewater via Response Surface Methodology" Water 17, no. 23: 3427. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233427

APA StyleYeber, M. C., & Paredes, B. (2025). Optimization of the Fe0/H2O2/UV Photo-Fenton Process for Real Textile Wastewater via Response Surface Methodology. Water, 17(23), 3427. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17233427