Abstract

Tetracycline (TC), commonly utilized in medicine and aquaculture, frequently enters aquatic environments, raising ecological concerns. This study examined TC-contaminated wastewater treated through ultraviolet (UV), potassium persulfate (PS), and combined UV/PS disinfection processes. The degradation of TC followed pseudo-first-order kinetics, with removal efficiency ranked as UV/PS > UV > PS. High-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) identified 20 disinfection byproducts (DBPs) across all processes. Based on the identified intermediates, the degradation pathways of TC under different disinfection processes (UV, PS, and UV/PS) were elucidated. Using the ECOSAR program, both acute and chronic aquatic toxicities of TC and its DBPs were predicted. The biological effects on Chlorella were also investigated. DBPs from UV and PS treatments inhibited algal growth, reducing it by 4.8–9.4% relative to the control. Conversely, DBPs formed under UV/PS disinfection stimulated growth, increasing rates by 3.4–6.6%. To counteract oxidative stress from TC and its DBPs, Chlorella enhanced superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) activities. These findings highlight that while TC degradation occurs efficiently, the nature of DBPs and their ecological impacts vary significantly depending on the disinfection method. Overall, the UV/PS process not only improved TC removal but also reduced harmful effects on microalgal growth compared with UV or PS alone.

1. Introduction

Disinfection serves as a critical measure for controlling the transmission of pathogenic microorganisms in water bodies. UV disinfection technology is widely employed in advanced treatment and water reuse stages due to its high efficiency, broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, and operational safety, particularly for degrading recalcitrant trace organic contaminants. However, its performance is significantly compromised by water turbidity and color, in addition to high energy consumption [1]. Sulfate radical-based advanced oxidation processes (SR-AOPs) activate PS to generate sulfate radicals (SO4−) for organic pollutant degradation, demonstrating potential in pretreating high-concentration industrial wastewater. Nevertheless, challenges such as substantial energy consumption, metal sludge generation, and sulfate byproduct formation remain [2,3]. The activation of PS proceeds slowly under natural conditions, whereas UV irradiation effectively activates PS to yield abundant SO4−, significantly enhancing contaminant removal efficiency. Laboratory studies have confirmed that the combined UV/PS process exhibits notable synergistic effects, indicating promising application prospects. However, certain DBPs formed during the disinfection process may exhibit higher toxicity than their parent compounds [4]. Studies have shown that during chlorination, chlorine reacts with natural organic matter (NOM) present in water to form DBPs such as trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetic acids (HAAs) [5], which can increase the risk of liver cancer [6] and bladder cancer [7]. Zheng et al. evaluated the toxicity of sulfadiazine solutions treated with different advanced oxidation processes using Chlorella as a model organism. Their findings demonstrated that the compounds produced in the PS system exhibited the highest toxicity [8].

Antibiotics have been widely used to improve health care and human quality of life. However, it has also led to a sharp increase in their consumption and raised concerns regarding antibiotic resistance. Among them, TC is extensively applied in human medicine, animal husbandry, and aquaculture due to its low cost and strong antibacterial activity [9,10,11,12]. Incompletely metabolized antibiotics in animals are excreted into the environment, contaminating surface water and groundwater [13]. Studies indicate that the average global concentration of TC in surface water ranges from 0.01 to 1 μg/L, with peak levels of up to 9500 ng/L detected in Beijing and Hebei, China [14,15]. In wastewater treatment plants worldwide, TC concentrations in the influent vary between 0.001 and 15 μg/L; for instance, at a municipal plant in Iran, TC was measured at 0.011 μg/L among multiple antibiotics detected in the inlet flow [16,17]. As a widely occurring DBP precursor in aquatic environments, TC can undergo reactions such as substitution and ring-opening with oxidants during disinfection. Zhou et al. [18] demonstrated that chlorination and chloramination of TC can generate byproducts including chloroform, carbon tetrachloride (CT), dichloroacetonitrile (DCAN), and dichloroacetone (DCAce). Brominated DBPs, formed from reactions between bromide ions and disinfectants/natural organic matter in water [19], generally exhibit significantly stronger cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and developmental toxicity than their chlorinated analogues [20,21,22,23,24]. Advanced disinfection processes such as UV/O3/PDS and UV/NH2Cl have also been shown to produce a variety of high-molecular-weight products with enhanced acute toxicity [25,26]. These toxic compounds and DBPs are discharged with treated effluent into water bodies, posing a threat to aquatic ecosystems.

Microalgae, as primary producers in aquatic ecosystems, are widely distributed across various water bodies and play a crucial role in the biogeochemical cycles of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus. They contribute to carbon sequestration through photosynthesis and participate in the decomposition and purification of organic matter, making them essential for maintaining the balance of aquatic ecosystems [27]. However, residual antibiotics and their DBPs in water bodies can affect microalgal growth [28]. Studies have shown that oxytetracycline (OTC) exhibits a “low-concentration promotion and high-concentration inhibition” effect on microalgae [29]; the photodegradation products of erythromycin (ERY) demonstrate considerable toxicity to Chlorella, particularly by inhibiting growth and chlorophyll synthesis during later exposure stages [30]; although low concentrations of TC significantly suppress microalgal growth, photosynthetic pigment content, and photosynthetic efficiency, the inhibition rate gradually decreases with prolonged exposure [31].

Previous studies mainly focused on the toxic effects of TC on microalgae. However, after disinfection of wastewater containing TC in water treatment plants, more toxic DBPs such as HAAs are produced and can persist in the water environment. Although various studies have reported the effects of TC and DBPs on microalgae, further research is necessary to elucidate their chronic toxic impacts and accurately assess the ecological risks posed to aquatic environments. The specific objective of this study are (a) to investigate the degradation kinetics of TC under different disinfection methods (UV, PS, and UV/PS) and clarify the impact of different disinfection processes on the degradation of TC; (b) to examine the formation of DBPs during different disinfection processes and predict the toxicity of TC and DBPs to aquatic organisms; (c) to evaluate the toxic effects of TC and its DBPs on microalgae under different disinfection methods. The present study features two key innovations: (1) a systematic comparative analysis of TC degradation pathways and DBPs formation profiles under three distinct oxidation processes (UV, PS, and UV/PS); (2) an integrated assessment combining UV/PS advanced oxidation with Chlorella toxicity testing to evaluate the combined ecological effects of TC and its DBPs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

TC (AR), 0.1 mol/L sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) standard solution, potassium dihydrogen phosphate (AR), sodium dihydrogen phosphate (AR), disodium hydrogen phosphate (AR), and formic acid (HPLC) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Methanol (HPLC grade) was obtained from ACS Enco Chemical Company (Wilmington, DE, USA). Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 was acquired from Shanghai Maclin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), PS (AR), and anhydrous ethanol (AR) was supplied by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). BG-11 medium was purchased from Qingdao Haibo Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Qingdao, China). All the experimental water was prepared using deionized water.

2.2. Experimental Procedures

2.2.1. Culture of Chlorella

Microalgae, serving as primary producers in aquatic environments, form the foundation of the food chain and play a significant role in shaping the structure and function of ecosystems [32,33]. Owing to their short growth cycle and high sensitivity to pollutants, Chlorella has been widely employed in toxicity assays [34]. Based on these considerations, Chlorella was selected as the test organism in this study. Chlorella sp. (FACHB-5) was obtained from the Freshwater Algal Species Bank of the National Aquatic Biological Germplasm Resources Bank (Wuhan, China). For detailed cultivation procedures, refer to Supplementary Text S1.

2.2.2. Analysis of the Degradation of TC and the Generation of DBPs

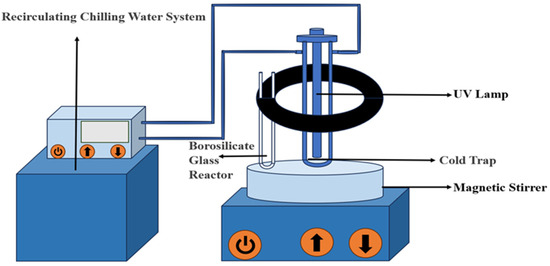

The disinfection methods employed were UV, PS, and UV/PS. The photochemical reaction apparatus is illustrated in Figure 1. The initial TC solution (10 mg/L) was subjected to UV, PS, and UV/PS disinfection processes, with samples collected at various time points and the reactions terminated using excess Na2S2O3. Detailed experimental procedures are provided in Supplementary Materials Text S2.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the photochemical reaction system.

2.2.3. Toxicity Experiments on Microalgae Exposed to TC and DBPs

The physiological and biochemical responses of Chlorella to TC and DBPs were assessed after different disinfection treatments. The TC-DBPs mixture (the detailed composition of the mixture is provided in Supplementary Text S3), obtained from the disinfection of a 10 mg/L TC solution, was added to the culture medium of Chlorella. The algae were cultivated for 12 days, with daily monitoring of algal growth and periodic measurements of antioxidant enzyme activities. Detailed experimental procedures are provided in Supplementary Materials Text S4.

2.3. Analytical Methods

2.3.1. Determination of TC Concentrations and Identification of DBPs

TC concentrations were quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography-triple quadrupole mass spectrometry (LC-MS; Thermo Fisher TSQ Quantum Access MAX, Waltham, MA, USA). DBPs were analyzed by HPLC-high-resolution MS (Thermo Fisher Q-Exactive, Waltham, MA, USA) after solid-phase extraction [35]. For detailed analytical procedures, refer to Supplementary Texts S5 and S6.

2.3.2. Determination of Algal Cell Growth

Algal growth was monitored daily by measuring OD680. Biomass was determined spectrophotometrically [36] (Shanghai Metash Instruments Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). For detailed methodologies, refer to Supplementary Text S7. Then, the absorbance of the corresponding Chlorella suspension was measured at 680 nm. The cell dry weight (g/L) was calculated by Formula (1):

2.3.3. Determination of Biochemical and Physicochemical Indicators of Microalgae

SOD (A007-1-1 Visible light method) and CAT (A001-1-2 Hydroxylamine method) activities were determined using assay kits manufactured by the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China. For comprehensive details on the crude enzyme extraction protocol, refer to Supplementary Text S8.

Chlorophyll was extracted with 95% ethanol after centrifuging 5 mL of suspension (10,000 RPM, 10 min). The extract was kept in darkness at 4 °C for 24 h, centrifuged again, and absorbance was measured at 652, 665, and 645 nm. Chlorophyll content was calculated by Formula (2) [37]:

2.4. Data Analysis

All experiments in this study were performed in triplicate. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance of differences in physiological and biochemical parameters was assessed by one-way ANOVA using SPSS 25.0, followed by LSD post hoc testing. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All figures were generated with Origin Pro 2025.

3. Results

3.1. Degradation Kinetics of TC Under Different Disinfection Methods

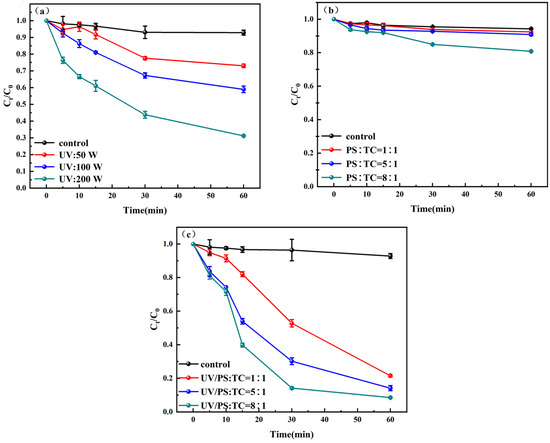

The removal results of TC by disinfection processes such as UV, PS, and UV/PS are shown in Figure 2. The pseudo-first-order degradation kinetics of TC can be found in Supplementary Materials Figure S1. The TC removal efficiency of the three disinfection methods is UV/PS > UV > PS. The maximum removal rate of TC by UV/PS disinfection within 60 min reached 91.5%, with a pseudo-first-order rate constant of 0.044 min−1. The maximum removal rate of TC by UV disinfection reached 68.8% (k = 0.018 min−1), while TC removed only 19.2% (k = 0.003 min−1) under the PS disinfection condition. The reactions followed pseudo-first-order kinetics with respect to TC at pH 7. As the power of the ultraviolet lamp increased, the removal rate of TC also increased accordingly. When the ultraviolet lamp was 50 W, 100 W, and 200 W, the removal rates of TC were 27%, 41% and 68.8%, respectively, which were 2.7 times, 3.6 times, and 5.7 times that of the control group. PS alone showed limited efficacy even at high [PS]0/[TC]0 ratios (8:1), achieving only 19.2% degradation. UV activation markedly enhanced PS performance, with removal rates of 78.4%, 85.9%, and 91.5% at ratios of 1:1, 5:1, and 8:1, respectively. The enhancement was attributed to UV-induced cleavage of the O–O bond in PS, generating SO4− radicals that efficiently degrade TC.

Figure 2.

Degradation of TC by (a) UV, (b) PS, and (c) UV/PS Systems.

3.2. Identification of TC DBPs Under Different Disinfection Conditions

The formation of DBPs from TC during UV, PS, and UV/PS disinfection processes was identified by HPLC-MS. The chemical formula, relative molecular mass, and other information for the major DBPs can be found in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3. Fragmentation mass spectra of the major DBPs are provided in Supplementary Figure S2. The chemical formulas, relative molecular masses, and other information for all DBPs can be found in Tables S1–S3 of the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Identification of Major DBPs in UV Disinfection.

Table 2.

Identification of major DBPs in PS disinfection.

Table 3.

Identification of major DBPs in UV/PS disinfection.

3.3. Analysis of TC Degradation Pathways Under Different Disinfection Methods

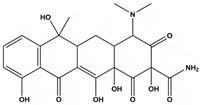

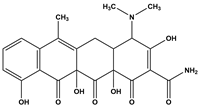

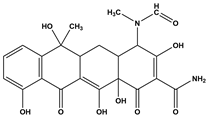

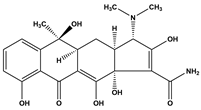

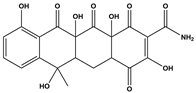

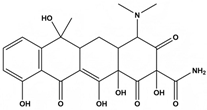

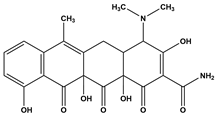

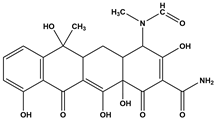

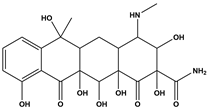

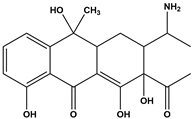

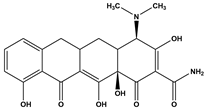

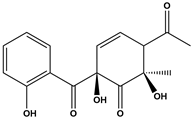

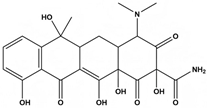

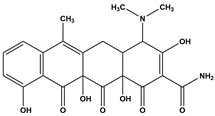

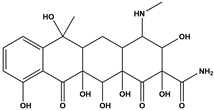

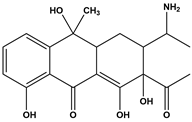

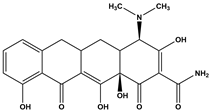

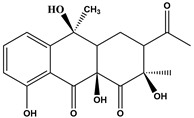

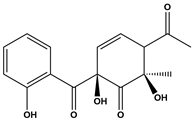

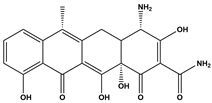

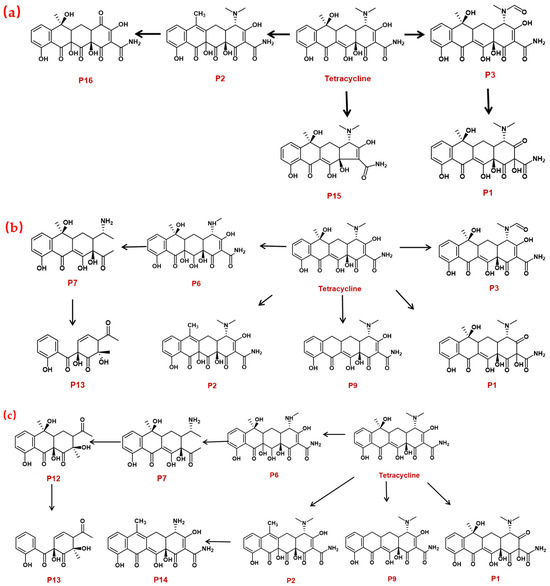

The DBPs of TC under UV, PS, and UV/PS conditions were identified by HPLC-MS. Potential structural formulas of the DBPs were proposed based on fragment information and mass-to-charge ratios (m/z). The structures of the proposed DBPs were drawn using Chem Draw Professional 23.1, and the degradation pathways of TC under different treatment conditions were analyzed. The degradation pathway diagram is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

TC degradation pathways under different disinfection processes: (a) UV, (b) PS, (c) UV/PS.

Based on the findings of this study, two degradation pathways of TC during UV disinfection have been proposed. Pathway I involves sequential oxidation and cleavage of the A-ring: the hydroxyl group on the A-ring is oxidized to a ketone, while simultaneous saturation of the double bond and hydroxyl radical (OH) addition lead to the formation of P1. Subsequently, the N,N-dimethylamino group on the A-ring undergoes oxidation, yielding P3, which contains a carbonyl group. Finally, due to steric hindrance and high reactivity of the carbonyl group adjacent to carbon-1 on the A-ring, cleavage rearrangement occurs with decarbonylation, resulting in the formation of P15. Pathway II primarily entails dehydroxylation of the C-ring and cleavage of the C–N bond: carbon-6 on the C-ring undergoes dehydroxylation and reacts with ·OH to form P2. Additionally, under ·OH attack and strong oxidizing conditions, the C–N bond in the TC molecule is cleaved, leading to the removal of the N,N-dimethylamino group at position 4, accompanied by oxidation, ultimately generating P16.

Two distinct degradation pathways of TC were proposed in the PS disinfection system: Pathway I commences with the oxidation of the hydroxyl group on the A-ring to a ketone group, concurrent with saturation of the double bond and its electrophilic addition by hydroxyl radicals, leading to the formation of P1. In a parallel reaction, dehydroxylation at the C-6 position of the C-ring, followed by hydroxylation, yields P2. Subsequently, the N,N-dimethylamino group on the A-ring undergoes oxidation to form P3, which then participates in a nucleophilic substitution reaction to generate P9. Pathway II is initiated by radical-mediated N-demethylation of the N,N-dimethylamino group, producing the intermediate P6. This is followed by complete dealkylation, which results in carbon ring cleavage and dehydroxylation, forming P7 that contains a primary amino group. Ultimately, carbon ring fission occurs at the C-6 position, giving rise to the ring-opened final product P13.

Three distinct degradation pathways of TC were proposed in the UV/PS disinfection system. Pathway I begins with the oxidation of the hydroxyl group on the A-ring to a ketone, concomitant with saturation of the double bond and its electrophilic addition by hydroxyl radicals, leading to the formation of P1. Subsequently, TC undergoes a substitution reaction to generate P9. Pathway II, concurrent with Pathway I, involves the dehydroxylation at the C-6 position of the C-ring followed by hydroxylation, yielding P2. P2 then undergoes demethylation to form P14. Pathway III is initiated by a radical attack on the N,N-dimethylamino group, which undergoes stepwise demethylation. Initial N-demethylation produces the intermediate P6, followed by complete dealkylation that induces cleavage of the carbon ring and dehydroxylation, forming P7, which contains a primary amino group. P7 is further oxidized to the intermediate P12, culminating in carbon-ring fission at the C-6 position and the formation of the ring-opened final product P13.

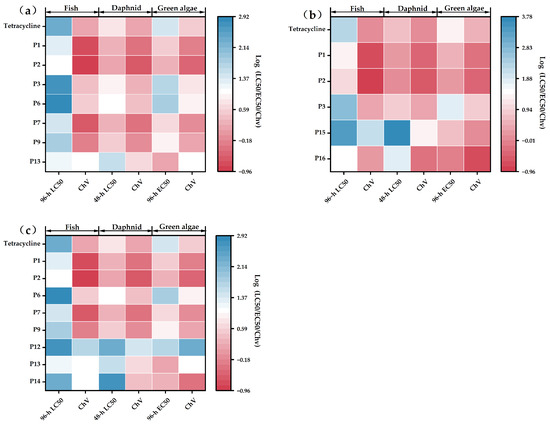

3.4. Toxicity Prediction of TC DBPs Under Different Disinfection Conditions

The present study employed the ECOSAR (Version 2.2) software to predict the acute and chronic toxicity of TC and its DBPs toward aquatic organisms, including Daphnia magna, green algae, and fish (a detailed description of the ECOSAR software is provided in Supplementary Materials Text S9). Toxicity classification was based on the internationally adopted Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals (GHS). According to this system, a compound is classified as “non-toxic” if its acute or chronic toxicity values (LC50/EC50/ChV) exceed 100 mg/L; as “harmful” if the values fall within the range of 10–100 mg/L; as “toxic” for values between 1 and 10 mg/L; and as “highly toxic” if the values are below 1 mg/L. Based on the results presented in Figure 4 and the calculated data, TC exhibits chronic toxicity toward all three aquatic organisms. Among the DBPs generated by different disinfection processes, some products showed enhanced acute toxicity to green algae compared to the parent TC. Specifically, during UV disinfection, products P1, P2, and P16 exhibited increased acute toxicity to green algae. Among these, P1 and P2 were classified as “toxic”, while P16 was classified as “highly toxic”. In contrast, the toxicity of P3 decreased. During PS disinfection, products P1, P2, P7, P9, and P13 showed enhanced acute toxicity to green algae, all of which were categorized as “toxic”, whereas the toxicity of P3 and P6 decreased. During UV/PS disinfection, products P1, P2, P7, P9, and P13 similarly demonstrated increased acute toxicity to green algae and were all classified as “toxic”, while the toxicity of P6, P12, and P14 was reduced. It is noteworthy that TC and its degradation products consistently exhibited chronic toxicity at “toxic” or even “highly toxic” levels toward all three non-target aquatic organisms. Therefore, highly toxic degradation products of TC should be given particular attention in future research and environmental risk assessments.

Figure 4.

Log10 toxicity values of TC and DBPs for fish, daphnid, and alga predicted by ECOSAR ((a) UV, (b) PS, and (c) UV/PS).

3.5. Influence of TC and DBPs on Chlorella

3.5.1. Influence on the Growth of Chlorella

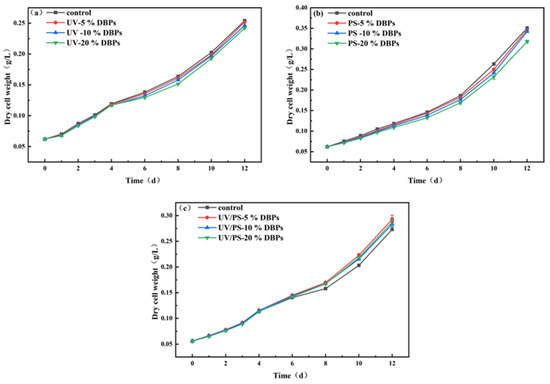

During the 12-day culture period, all DBPs produced by different disinfection methods had certain effects on the growth of Chlorella. Under UV disinfection conditions, different concentrations of TC and its DBPs (5%, 10%, 20%, v/v) have certain effects on the growth of microalgae (as shown in Figure 5a). Compared with the control group, the growth of microalgae in the mixed solution of TC and its DBPs was inhibited within 12 days, and the inhibitory effect was more obvious with the increase in concentration. On the 6th and 12th days, the cell dry weight of Chlorella cultured with 20% TC and its DBPs was 6.3% and 4.8% lower than that of the control group, respectively. It can be seen that in the early and middle stages of culture, the inhibitory effect is relatively obvious. In the later stage of culture, due to the adsorption, transformation, and degradation of TC and its DBPs by microalgae, the toxic effects of TC and its DBPs may be alleviated. Similarly, under PS disinfection conditions, different concentrations of TC and its DBPs (5%, 10%, 20%, v/v) inhibited the growth of microalgae (as shown in Figure 5b). On the 12th day, the cell dry weight of Chlorella cultured with TC and its DBPs was 1.2%, 2.4%, and 9.4% lower than that of the control group, respectively. The inhibitory effect becomes more obvious as the concentration increases.

Figure 5.

Microalgal growth inhibition after 12-day exposure to DBPs from (a) UV, (b) PS, and (c) UV/PS.

However, under UV/PS conditions, varying concentrations (5%, 10%, 20%, v/v) of TC and its DBPs stimulated microalgal growth. As illustrated in Figure 5c, cultures amended with DBPs under UV/PS treatment exhibited a statistically significant stimulatory effect relative to the control group from the 6th day onward. This growth-promoting effect was more pronounced at lower concentrations. By day 12, Chlorella cultures supplemented with 20% TC and its DBPs demonstrated a 5.2% increase in cell dry weight compared to the control group. This phenomenon arises because the disinfection efficacy of the UV/PS process significantly exceeds that of UV irradiation or (PS) alone. UV/PS mineralizes TC and its DBPs to a greater extent through enhanced oxidation processes, mitigating the inhibitory effects of TC and DBPs on Chlorella growth. In addition, low concentrations of organic pollutants cause little oxidative damage but activate the microalgal antioxidant defense system, promoting growth. Therefore, under UV/PS treatment, lower concentrations of TC and DBPs correlate with a more pronounced stimulatory effect on Chlorella growth. This finding aligns with the research conducted by Li et al. that the photodegradation of erythromycin (ERY) alleviates its inhibitory effect on microalgal growth capacity, with complete degradation even slightly promoting microalgal proliferation [30]. Toxicity prediction indicates that most DBPs generated by UV and PS disinfection exhibit higher toxicity than TC. Consequently, the growth inhibition of Chlorella cultivated with UV/PS-derived DBPs aligns with the toxicity predictions for TC and its DBPs. However, different disinfection methods yield distinct types and compositions of DBPs. The impact of DBPs on microalgal growth represents a combined effect involving multiple factors, including DBP species and concentration. Therefore, UV/PS-generated DBPs demonstrate a mitigating effect on the growth inhibition of Chlorella.

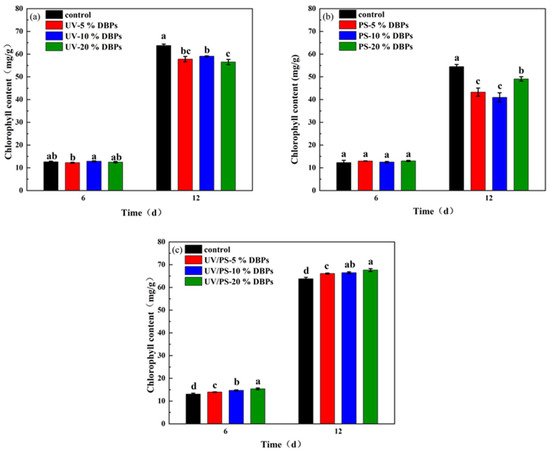

3.5.2. Effects of TC and DBPs on the Physiological and Biochemical Indicators of Protein Nucleolus

The chlorophyll content was similar to the growth and change trend of Chlorella. As shown in Figure 6, the chlorophyll concentration of Chlorella cultured with DBPs produced by UV treatment was 9.4%, 11.4%, and 7.4% lower than that of the control group at day 12, respectively. The chlorophyll concentration of protein–nucleus Chlorella cultured with DBPs produced by PS treatment was 20.6%, 24.8%, and 10% lower than that of the control group, respectively. The chlorophyll concentration of Chlorella cultured with DBPs treated with UV/PS was 3.6%, 4.2%, and 6% higher than that of the control group, respectively. That indicated that the DBPs produced by UV and PS disinfection inhibited the synthesis of chlorophyll in Chlorella, while the DBPs produced by UV/PS disinfection promoted the synthesis of chlorophyll in Chlorella.

Figure 6.

Chlorophyll content in microalgae exposed to DBPs from (a) UV, (b) PS, and (c) UV/PS disinfection. Different letters indicate statistical differences between treatments and the control group in each period of cultivation (p < 0.05).

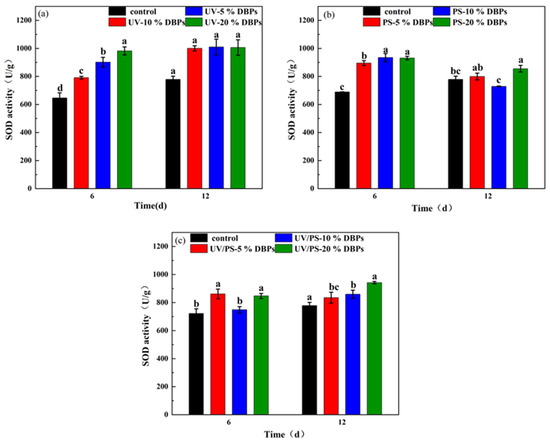

Under different concentration conditions, TC and its DBPs exerted discernible effects on the SOD activity of Chlorella, demonstrating clear concentration- and time-dependent trends. As shown in Figure 7a, SOD activity in Chlorella cells cultured with TC and its DBPs after UV treatment was measured on day 6 and day 12. With increasing concentrations of TC and its DBPs, SOD activity generally increased on day 6, with the 20% concentration treatment group showing a 49.7% increase compared to the control. As illustrated in Figure 7b,c, similar trends were observed in the PS and UV/PS treatment groups, with increases of 35.2% and 17.4%, respectively. This phenomenon indicates that algal cells activated their internal antioxidant defense system to counteract the oxidative stress induced by TC and its DBPs. The elevation in SOD activity, however, also suggests that the cells may be under oxidative stress, with elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) triggering a compensatory upregulation of antioxidant enzymes. It is noteworthy that at the same concentration, DBPs generated by different disinfection processes induced varying degrees of SOD activity, with the UV/PS group being significantly higher than the PS and UV groups. This may be attributed to the UV/PS combined process producing a mixture of DBPs with higher toxicity or stressor potency, causing the most severe oxidative stress to Chlorella and thereby eliciting a stronger primary antioxidant defense response. This highlights that when assessing the ecological risk of disinfection processes, it is essential not only to focus on the removal efficiency of the parent compound but also to consider the biological effects of its transformation products. Although advanced oxidation processes such as UV/PS are more efficient in contaminant removal, they may generate byproducts with higher environmental risks, warranting considerable attention. Wu et al. reported that intermediates could pose higher toxicity risks [38], which aligns with our findings. By day 12, SOD activity in most treatment groups remained higher than that of the control, with increases ranging from 2.7% to 30.1%, indicating the persistent oxidative stress effects of TC and its DBPs on algal cells. From a temporal perspective, SOD activity in the UV and UV/PS groups was higher on day 12 than on day 6, further suggesting cumulative oxidative damage effects under long-term exposure, prompting algal cells to continuously activate antioxidant mechanisms to maintain homeostasis. However, the convergence or decline in the increase in SOD activity under high concentrations of DBPs may imply a gradual imbalance in the antioxidant system under sustained stress, or even inhibition of enzyme activity. This provides important clues for further elucidating the algal toxicity mechanisms of TC and its DBPs.

Figure 7.

SOD activity in microalgae exposed to DBPs from (a) UV, (b) PS, and (c) UV/PS. Different letters indicate statistical differences between treatments and the control group in each period of cultivation (p < 0.05).

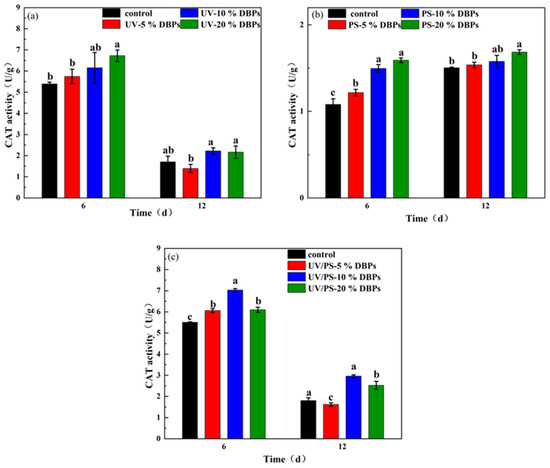

On day 6, the CAT activity in Chlorella increased significantly with rising concentrations of TC and its DBPs. Under UV treatment, as shown in Figure 8a, the 20% concentration group exhibited a 49.7% increase in CAT activity compared to the control. Similarly, under PS and UV/PS treatments (Figure 8b,c), increases of 35.2% and 17.4% were observed, respectively. This trend aligns closely with the upregulation of SOD activity observed during the same period (Figure 8a), collectively indicating the coordinated activation of the algal antioxidant defense system during the early stress phase. From a biochemical pathway perspective, SOD serves as the first line of defense in the antioxidant cascade, catalyzing the dismutation of superoxide anions (O2·−) into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). CAT, as a crucial secondary scavenging enzyme, prevents H2O2 from being converted into the more toxic ·OH via metal-catalyzed reactions. The synchronous induction of SOD and CAT reflects an effective adaptive response by the cells to maintain redox homeostasis. By day 12, CAT activity in all treatment groups remained elevated compared to the control (increases ranging from 2.7% to 30.1%), confirming the persistent impact of TC and its DBPs. However, in the UV and UV/PS treatment groups, CAT activity on day 12 was lower than that on day 6. This trend contrasts sharply with the SOD activity, which was higher on day 12 than on day 6, indicating a disruption in the coordinated antioxidant mechanism. The decoupling of SOD and CAT activities may be attributed to the sustained high activity of SOD, leading to excessive H2O2 production. When intracellular H2O2 accumulates beyond a critical threshold, it can directly inhibit CAT activity.

Figure 8.

Catalase activity in microalgae exposed to DBPs from (a) UV, (b) PS, and (c) UV/PS. Different letters indicate statistical differences between treatments and the control group in each period of cultivation (p < 0.05).

By comprehensively analyzing the dynamic changes in SOD and CAT activities, the response trajectory of Chlorella to TC and its DBPs can be systematically delineated. Under short-term exposure (day 6), the cells established an effective and comprehensive antioxidant defense by coordinately upregulating both SOD and CAT activities. However, under long-term exposure (day 12), particularly under the stress induced by specific DBPs generated via advanced oxidation processes such as UV/PS, this coordinated defense was disrupted. The sustained high SOD activity coupled with declining CAT activity indicates a transition in the cellular antioxidant system from an effective compensatory adaptation phase to a hazardous, dysfunctional phase. This provides critical toxicological evidence for comprehensively assessing the long-term ecological risks of DBPs.

4. Conclusions

In this study, UV, PS, and UV/PS processes were employed for TC disinfection. The degradation kinetics of TC during disinfection were analyzed to investigate the subsequent formation of DBPs. Based on the identified intermediates, the degradation pathways of TC under different disinfection processes (UV, PS, and UV/PS) were elucidated. The aquatic toxicity of these DBPs was evaluated using the Ecological Structure Activity Relationships (ECOSAR) model. Furthermore, the toxic response of Chlorella to simultaneous exposure to TC and its DBPs was investigated. Results indicated that TC removal efficiency followed the order UV/PS > UV > PS. All three disinfection processes conformed to pseudo-first-order kinetic models. HPLC-MS analysis identified 20 distinct DBPs primarily derived from TC under the three disinfection methods. Acute and chronic toxicity predictions for TC and its DBPs towards aquatic organisms, generated via ECOSAR software, revealed that nine DBPs (including P1, P2, and P7) exhibited greater toxicity than the parent TC compound. The DBPs generated by the different disinfection methods exerted varying effects on Chlorella growth. Specifically, DBPs from UV and PS disinfection inhibited Chlorella growth, whereas DBPs generated by the UV/PS process promoted growth. Under stress induced by TC and its DBPs, Chlorella exhibited the capacity to mitigate oxidative damage by enhancing the activities of superoxide dismutase SOD and CAT. Overall, the degradation efficacy of PS alone on TC was negligible. However, UV activation significantly enhanced TC degradation by PS. Notably, the disinfection processes generated DBPs exhibiting greater toxicity than TC. While DBPs from UV and PS disinfection inhibited Chlorella growth, those generated during the UV/PS disinfection process demonstrated minimal impact on Chlorella growth in aquatic environments, with a slight growth-promoting effect observed. This indicates that Chlorella possesses potential for the transformation and utilization of TC and its DBPs, suggesting a potential positive role in mitigating environmental antibiotic contamination.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17213140/s1, Text S1: Culture of Chlorella; Text S2: Analysis of the degradation of TC and the generation of DBPs; Text S3: Concentration and composition of the TC-DBPs mixture; Text S4: Toxicity experiments on Microalgae Exposed to TC and DBPs; Text S5: Determination of TC concentration; Text S6: Determination of DBPs; Text S7: Determination of algal cell growth; Text S8: Preparation of crude enzyme extracts; Text S9: Introduction to ECOSAR; Table S1: Identification of DBPs in UV Disinfection; Table S2: Identification of DBPs in PS Disinfection; Table S3: Identification of DBPs in UV/PS Disinfection; Figure S1: Pseudo-first-order degradation kinetics of TC by UV (b), PS (d), and UV/PS (f) disinfection processes; Figure S2: Fragmentation mass spectra of TC-derived DBPs; Figure S3: Growth status of Chlorella on day 12 of exposure to DBPs generated from (a) UV, (b) PS, and (c) UV/PS processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.G.; validation, Y.G. and T.Z.; formal analysis, T.Z., K.S., J.W., C.Z. and J.L.; data curation, Y.G. and T.Z.; writing—original draft, T.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.G. and Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 42407497) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (No. BK20230643).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mortezazadeh, F.; Ahmadi Nasab, M.; Javid, A.; Changani, F.; Dehghani, M.H. A review of UV-based advanced oxidation processes in wastewater treatment systems. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 323, 101388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakis, S.; Lin, K.-Y.A.; Ghanbari, F. A review of the recent advances on the treatment of industrial wastewaters by Sulfate Radical-based Advanced Oxidation Processes (SR-AOPs). Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 127083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Xiong, Z.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, H.; Huang, R.; Yao, G.; Lai, B. Marriage of membrane filtration and sulfate radical-advanced oxidation processes (SR-AOPs) for water purification: Current developments, challenges and prospects. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, Y.-L.; Wang, X.-S.; Zhao, X.-N.; Zhu, Z.-Y.; Ma, C.-N.; Cui, C.-W.; Ma, J.; Wang, L. Phenols coupled during oxidation upstream of water treatment would generate higher toxic coupling phenolic disinfection by-products during chlorination disinfection. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 483, 136678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, R.M.; Rice, G. Characterizing Microbial and DBP RIsk Tradeoffs In Drinking Water: AppUcadon of the CRFM. In Advances in Water and Wastewater Treatment; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2004; p. 456. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, R.; Meier, J.; Robinson, M.; Ringhand, H.; Laurie, R.; Stober, J. Evaluation of mutagenic and carcinogenic properties of brominated and chlorinated acetonitriles: By-products of chlorination. Fundam. Appl. Toxicol. 1985, 5, 1065–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evlampidou, I.; Font-Ribera, L.; Rojas-Rueda, D.; Gracia-Lavedan, E.; Costet, N.; Pearce, N.; Vineis, P.; Jaakkola, J.J.; Delloye, F.; Makris, K.C. Trihalomethanes in drinking water and bladder cancer burden in the European Union. Environ. Health Perspect. 2020, 128, 017001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Mariñas, B.J.; Minear, R.A. Bromamine decomposition kinetics in aqueous solutions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Moe, B.; Vemula, S.; Wang, W.; Li, X.-F. Emerging disinfection byproducts, halobenzoquinones: Effects of isomeric structure and halogen substitution on cytotoxicity, formation of reactive oxygen species, and genotoxicity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 6744–6752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Zhang, X. Comparative developmental toxicity of new aromatic halogenated DBPs in a chlorinated saline sewage effluent to the marine polychaete Platynereis dumerilii. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 10868–10876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-W.; Wang, G.-J.; Zang, S.; Qiao, Y.; Tao, H.-F.; Li, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.-S.; Ma, J. Halogenated aliphatic and phenolic disinfection byproducts in chlorinated and chloraminated dairy wastewater: Occurrence and ecological risk evaluation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 465, 132985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roccaro, P.; Korshin, G.V.; Cook, D.; Chow, C.W.; Drikas, M. Effects of pH on the speciation coefficients in models of bromide influence on the formation of trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids. Water Res. 2014, 62, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanigan, D.; Truong, L.; Simonich, M.; Tanguay, R.; Westerhoff, P. Zebrafish embryo toxicity of 15 chlorinated, brominated, and iodinated disinfection by-products. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 58, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, S.; Niu, J.; Dong, X.; Leong, Y.K.; Chang, J.-S. Dissecting the ecological risks of sulfadiazine degradation intermediates under different advanced oxidation systems: From toxicity to the fate of antibiotic resistance genes. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 941, 173678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bao, J.; Du, J.; Mao, Q.; Cheng, B. Comprehensive metagenomic and enzyme activity analysis reveals the inhibitory effects and potential toxic mechanism of tetracycline on denitrification in groundwater. Water Res. 2023, 247, 120803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Xiong, J.-Q.; Zhao, C.-Y.; Ru, S. Unraveling the key driving factors involved in cometabolism enhanced aerobic degradation of tetracycline in wastewater. Water Res. 2022, 226, 119285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, J.; Xie, W.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, T.; Zhou, H.; Wang, Q.; Li, H.; Guo, Z.; Xu, B.B.; Gu, H. Magnetic field facilitated electrocatalytic degradation of tetracycline in wastewater by magnetic porous carbonized phthalonitrile resin. App. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 340, 123225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Wang, M.; Bai, Y.; Song, H.; Lv, J.; Mo, X.; Li, X.; Lin, Z. Upcycling of nickel iron slags to hierarchical self-assembled flower-like photocatalysts for highly efficient degradation of high-concentration tetracycline. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 464, 142532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.D.; Plewa, M.J. CHO cell cytotoxicity and genotoxicity analyses of disinfection by-products: An updated review. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 58, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wang, S.; Fan, J.; Long, S.; Wang, L.; Tang, C.; Tam, N.F.; Yang, Y. Predicting distribution coefficients for antibiotics in a river water–sediment using quantitative models based on their spatiotemporal variations. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 655, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Hao, H.; Xu, N.; Liang, X.; Gao, D.; Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tao, H.; Wong, M. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in water, sediments, aquatic organisms, and fish feeds in the Pearl River Delta: Occurrence, distribution, potential sources, and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 659, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, H.; Xiong, P.; Zhu, Q.; Liao, C.; Jiang, G. Occurrence, fate, and risk assessment of typical tetracycline antibiotics in the aquatic environment: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 141975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafaei, R.; Papari, F.; Seyedabadi, M.; Sahebi, S.; Tahmasebi, R.; Ahmadi, M.; Sorial, G.A.; Asgari, G.; Ramavandi, B. Occurrence, distribution, and potential sources of antibiotics pollution in the water-sediment of the northern coastline of the Persian Gulf, Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shao, Y.; Gao, N.; Zhu, S.; Ma, Y.; Deng, J. Chlorination and chloramination of tetracycline antibiotics: Disinfection by-products formation and influential factors. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014, 107, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Q. Synergistic effects of peroxydisulfate on UV/O3 process for tetracycline degradation: Mechanism and pathways. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, A.; Deng, J.; Xu, M.; Zhu, T.; Zhou, S.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Li, X. Degradation of tetracycline by UV activated monochloramine process: Kinetics, degradation pathway, DBPs formation and toxicity assessment. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395, 125090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Bashan, L.E.; Hernandez, J.-P.; Morey, T.; Bashan, Y. Microalgae growth-promoting bacteria as “helpers” for microalgae: A novel approach for removing ammonium and phosphorus from municipal wastewater. Water Res. 2004, 38, 466–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiki, C.; Rashid, A.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, C.-P.; Sun, Q. Dissipation of antibiotics by microalgae: Kinetics, identification of transformation products and pathways. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 387, 121985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, J.; Xia, A.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, X.; Liao, Q. Microalgae cultivation for antibiotic oxytetracycline wastewater treatment. Environ. Res. 2022, 214, 113850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, W.; Liu, N.; Du, C. Chronic toxic effects of erythromycin and its photodegradation products on microalgae Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Aquat. Toxicol. 2024, 271, 106922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Xie, Z. Toxic effects of tetracycline and its removal by the freshwater microalga Chlorella pyrenoidosa. Agron. J. 2022, 12, 2497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, W.; He, P. Development and validation of a liquid chromatographic/tandem mass spectrometric method for determination of chlortetracycline, oxytetracycline, tetracycline, and doxycycline in animal feeds. J. AOAC Int. 2012, 95, 1010–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.-Q.; Kurade, M.B.; Abou-Shanab, R.A.; Ji, M.-K.; Choi, J.; Kim, J.O.; Jeon, B.-H. Biodegradation of carbamazepine using freshwater microalgae Chlamydomonas mexicana and Scenedesmus obliquus and the determination of its metabolic fate. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 205, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liao, Q.; Huang, Y.; Xia, A.; Fu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zheng, Y. Integrating planar waveguides doped with light scattering nanoparticles into a flat-plate photobioreactor to improve light distribution and microalgae growth. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 220, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Gong, S.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Deng, H. Progress and problems of water treatment based on UV/persulfate oxidation process for degradation of emerging contaminants: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Lyu, T.; Zhan, L.; Matamoros, V.; Angelidaki, I.; Cooper, M.; Pan, G. Mitigating antibiotic pollution using cyanobacteria: Removal efficiency, pathways and metabolism. Water Res. 2021, 190, 116735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satthong, S.; Saego, K.; Kitrungloadjanaporn, P.; Nuttavut, N.; Amornsamankul, S.; Triampo, W. Modeling the effects of light sources on the growth of algae. Adv. Differ. Equ. 2019, 2019, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, P.; Luo, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Luo, S. Chlorella vulgaris mediated erythromycin co-metabolism: Stress response, degradation products and pathways. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 119390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).