Abstract

To address the issues of zero-valent iron Fe(0) passivation and limited nitrogen and phosphorus removal in constructed wetlands (CWs), this study investigated the enhancement effect of two carbon materials—activated carbon (AC) obtained through high-temperature pyrolysis and biochar (BC) obtained through low-temperature pyrolysis—when coupled with Fe(0). Four systems were set up: control (CW-C), Fe(0) alone (CW-Fe), Fe(0) with AC (CW-FeAC), and Fe(0) with BC (CW-FeBC). Evaluations covered wastewater treatment performance, microbial community structure, and functional gene abundance. Results showed that iron–carbon coupling significantly improved nitrogen and phosphorus removal, with the CW-FeAC system performing best, achieving 58% total nitrogen (TN) and 90% total phosphorus (TP) removal. This enhancement was attributed to AC’s high conductivity, which strengthened iron–carbon micro-electrolysis, accelerated Fe(0) corrosion, and enabled continuous Fe2+/Fe3+ release, supplying electrons for denitrification and phosphorus precipitation. Microbial analysis indicated that iron–carbon coupling markedly reshaped community structure, enriching key genera such as Thiobacillus (33.8%) and Geobacter (12.5%) in CW-FeAC. Functional gene analysis further confirmed higher abundances of denitrification (napA/narG→nirS→nosZ) and iron metabolism genes (feoA/feoB), suggesting enhanced nitrogen-iron cycling. This study clarifies the mechanisms by which iron–carbon coupling improves nitrogen and phosphorus performance in CWs and highlights the superiority of AC over BC in facilitating electron transfer and functional microorganism enrichment, providing a basis for the design of enhanced CW systems treating low-carbon-nitrogen-ratio wastewater, such as secondary effluent or lightly polluted surface water.

1. Introduction

Low-pollution water typically contains low concentrations of contaminants but displays notable fluctuations and continuous discharge patterns [1,2]. Such water can be rendered potable through conventional purification processes, including filtration and disinfection. It is commonly utilized in pollution prevention and control initiatives for lakes and reservoirs, primarily aiming at water resource protection and ecological restoration. Major sources of low-pollution water include treated effluent from wastewater treatment plants, agricultural runoff, and stormwater runoff. The nitrogen and phosphorus present in such water bodies can easily trigger eutrophication, disrupt aquatic ecosystems, and accumulate through the food chain, posing potential risks to human health [3,4]. Therefore, advanced removal of nitrogen and phosphorus from low-pollution water has become a crucial approach for controlling point-source pollution and ensuring aquatic environmental safety. Constructed wetlands (CWs) have gained increasing attention in this regard due to their low energy consumption, easy maintenance, and ecological benefits [5,6,7]. Nevertheless, the application of this technology in practical engineering still faces certain bottlenecks. The low carbon-to-nitrogen ratio in low-pollution water restricts heterotrophic denitrification, leading to inefficient nitrogen removal [8]. Meanwhile, traditional wetland substrates exhibit limited phosphorus adsorption capacity, and their long-term removal performance tends to decline, hindering stable phosphorus removal.

Iron, an abundant and reactive metal in the Earth’s crust, is widely used to enhance pollutant removal in CWs due to its low cost, easy availability, and environmental friendliness. Fe(0) can release Fe2+/Fe3+ via chemical corrosion [9,10], precipitate with phosphate for phosphorus removal [11,12], and consume oxygen to create an anaerobic microenvironment conducive to denitrification [13,14]. It can also directly participate in nitrate reduction. However, during long-term operation, iron materials are prone to form a dense oxide passivation layer on the surface, which impedes electron transfer and mass transport, leading to decreased nitrogen and phosphorus removal efficiency and compromised long-term stability. The need for passivation layer removal and material replacement further increases operational complexity. Therefore, improving the reactivity of iron-based materials and delaying surface passivation are crucial for enhancing iron-mediated electron transfer and achieving stable nutrient removal.

Carbon materials produced by high-temperature pyrolysis have been demonstrated as effective electron mediators for enhancing the performance of iron-based CWs [15]. When iron and carbon materials come into contact in wastewater, a microscopic galvanic cell (Figure S1) is formed spontaneously: Fe(0) acts as the anode, releasing Fe2+ and electrons, while protons are reduced at the carbon cathode to form reactive hydrogen atoms [H] [16,17]. These species serve as electron donors for autotrophic denitrification, significantly improving TN removal without the need for an external carbon source. Iron–carbon micro-electrolysis has shown promising pollutant removal in CWs. For instance, the combination of BC and amorphous iron hydroxide achieved over 90% NO3−-N removal in one-third of the time required by the control system, while also enhancing microbial activity and ion exchange [18]. Lian et al. found that the AC not only enhanced the activity of the electron transfer system but also increased the microbial diversity and abundance in the artificial wetland matrix layer composed of pyrite and sponge iron, effectively improving the total nitrogen removal efficiency and reducing greenhouse gas emissions [19]. It should be noted that BC (typically pyrolyzed below 700 °C) differs from AC (often activated above 700 °C) in structure and surface properties. BC usually carries a negative surface charge, which may hinder NO3−-N adsorption in the galvanic system, and its porosity and specific surface area are generally lower than those of AC [20,21]. BC can release organic carbon to support denitrifying microorganisms [22], whereas AC offers limited carbon release but superior conductivity and adsorption capacity.

Differences in structure and properties between BC and AC lead to variations in their nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance when coupled with Fe(0). While iron–carbon composite materials have been widely studied for treating high-concentration wastewater, their application in low-pollution water remains limited. In particular, a systematic comparison of the effectiveness and microbial response of Fe(0) coupled with conductive AC versus functional-group-rich BC in CWs is still lacking.

Therefore, this study systematically evaluates the nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance of Fe(0) combined with BC or AC in CWs treating low-pollution water. The research aims to clarify the distinct roles of different carbon materials in iron–carbon micro-electrolysis CW systems, providing a scientific basis for developing efficient and sustainable enhanced CW technologies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

The iron source used in this study was iron scraps procured from a machinery materials processing plant in Wenzhou, China. Composed mainly of industrial pure iron with an Fe(0) content exceeding 95%, the material exhibits a curled, shredded morphology with an average length of approximately 2 cm. The iron scraps (specific surface area: 0.4 m2/g) were washed to remove surface oil and cut into 2 cm pieces for subsequent use. The main elements of iron scraps used in the experiment was shown in Table S1.

BC and AC were prepared from Phragmites australis biomass collected in the laboratory via oxygen-limited pyrolysis in a tube furnace under a nitrogen atmosphere. BC was produced by pyrolyzing at 400 °C for 2 h, while AC was obtained by pyrolysis at 800 °C for 2 h followed by physical activation to enhance its pore structure. Both carbon materials were crushed and sieved to a diameter of about 7 mm and a length of 5–10 mm to ensure experimental uniformity. The physiochemical properties of BC and AC were shown in Table S2. Prior to use, all materials were rinsed with deionized water until the effluent was clear, dried in an oven at 60 °C to constant weight, and then stored separately in sealed containers in a cool, dry location within the laboratory to prevent moisture absorption and cross-contamination. Pictures of iron scraps and carbon materials can be seen in Figure S2.

2.2. Experimental Setup

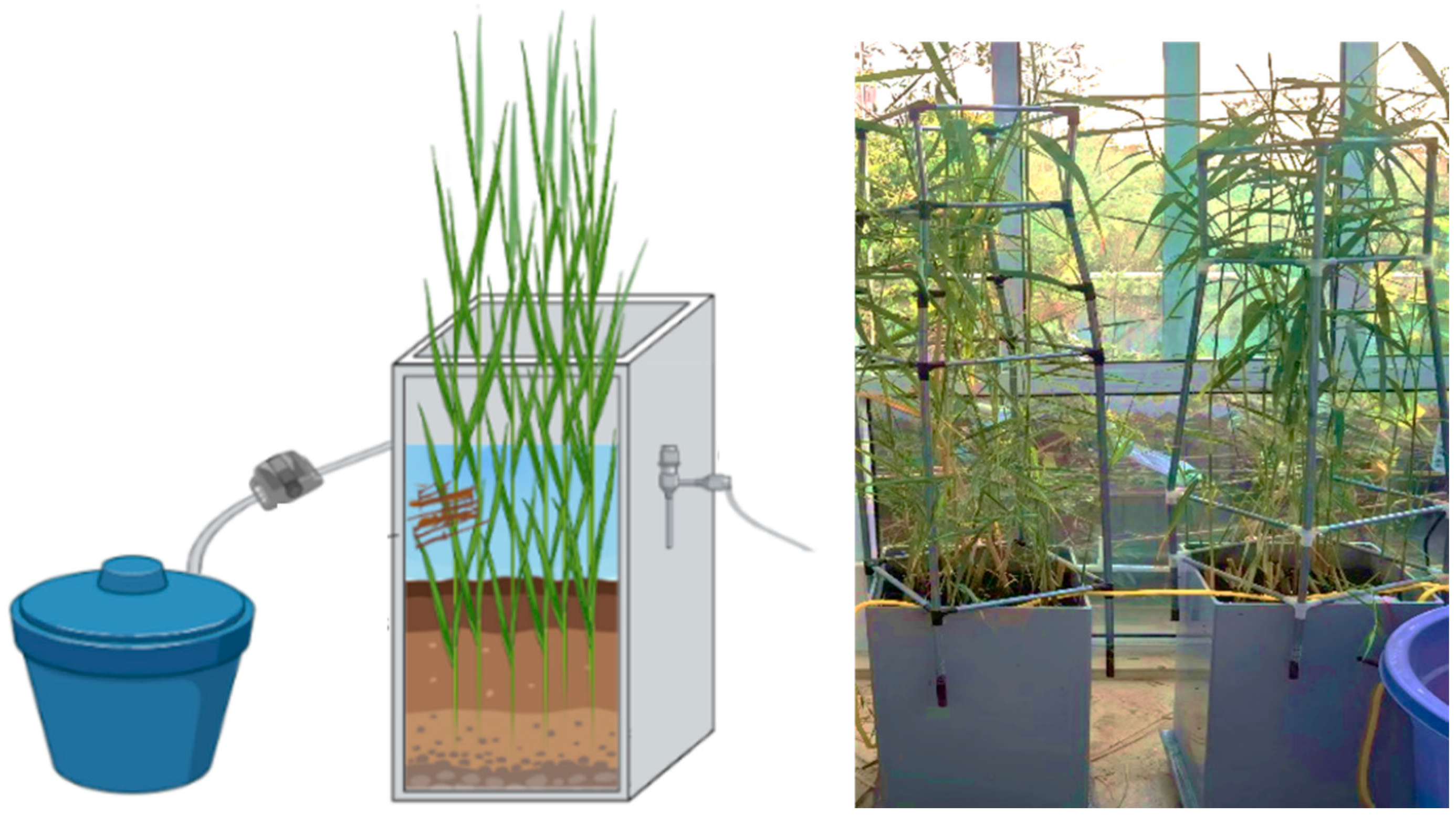

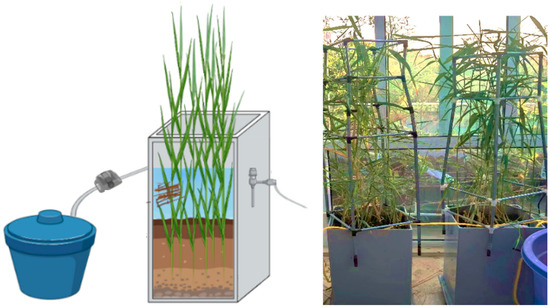

Four pilot-scale CW systems were established inside a greenhouse at the School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (Figure 1). Each reactor consisted of a rectangular polyethylene tank with internal dimensions of 30 cm (length) × 30 cm (width) × 60 cm (height). A 25 cm layer of sandy loam soil was placed at the bottom as the plant growth substrate, and a constant water depth of 15 cm was maintained during operation. Five uniformly grown seedlings of common Phragmites australis, with an initial height of approximately 30 cm, were planted in each system at a density of 56 plants/m2.

Figure 1.

Diagram and photograph of CW.

Four treatment groups were set up: control (CW-C, without functional materials), Fe(0) group (CW-Fe), Fe(0) plus AC group (CW-FeAC), and Fe(0) plus BC (CW-FeBC). Functional materials were added at a mass ratio of 2:1 (Fe(0) to carbon material), with each system receiving 20 g of iron scraps alone or mixed with 10 g of the corresponding carbon material. The materials were placed in nylon mesh bags (pore size ≤ 1 mm), which were suspended and fixed in the middle of the water column to ensure complete submersion and full contact with the water flow.

Synthetic wastewater was used as the influent, with the following baseline water quality parameters: NO3−-N: 4.05 ± 0.21 mg/L, NO2−-N: 0.06 ± 0.005 mg/L, NH4+-N: 0.05 ± 0.004 mg/L, TN: 4.17 ± 0.23 mg/L, TP: 0.21 ± 0.02 mg/L, and pH: 7.2–7.6. The CW systems were operated continuously for 60 days under natural conditions, with a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 2 days maintained by using a peristaltic pump for continuous inflow.

2.3. Water Sampling and Analysis

During the operation of the CWs, influent and effluent samples were collected every other day. Prior to sampling, water temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and pH were measured on-site using a portable multi-parameter water quality meter (YSI ProPlus, (YSI Incorporated, Yellow Springs, OH, USA)). The collected water samples were immediately placed in pre-cleaned polyethylene bottles and promptly transported to the laboratory for processing. Prior to analysis, all samples were filtered through 0.45 μm cellulose acetate membranes to remove suspended solids. All tests were conducted with triplicate measurements. Water quality parameters were determined in accordance with the standard methods using the following specific procedures:

NO3−-N: Ultraviolet spectrophotometric method at 220 nm and 275 nm (dual-wavelength);

NO2−-N: N-(1-Naphthyl) ethylenediamine spectrophotometric method at 540 nm;

NH4+-N: Salicylate-hypochlorite spectrophotometric method at 697 nm;

TN: Alkaline potassium persulfate digestion-UV spectrophotometric method;

TP: Potassium persulfate digestion-ammonium molybdate spectrophotometric method at 700 nm;

Total iron (TFe): 1,10-Phenanthroline spectrophotometric method at 510 nm.

Any samples not analyzed on the day of collection were stored at 4 °C and processed within 48 h.

2.4. Analysis of Microbial Community Composition and Diversity

To investigate the influence of different functional materials on the microbial community structure in the CWs, sediment samples were systematically collected from each wetland unit at the end of the experiment. Immediately after collection, samples were aliquoted into sterile cryotubes, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C before being sent within 24 h to Shanghai Majorbio Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) for high-throughput sequencing analysis. Total microbial DNA was extracted using the FastDNA® Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA) strictly following the manufacturer’s instructions. The V3–V4 hypervariable region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified with the primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was performed using an optimized protocol based on established methods. The amplified products were purified, quantified, normalized, and subjected to paired-end sequencing on the Illumina NovaSeq platform [23,24]. After quality control and chimera removal, the raw sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at a 97% similarity threshold using USEARCH. An OTU table was generated, and alpha diversity indices (including Chao1 and Shannon index) were calculated to assess microbial community diversity. The specific experimental procedures can be found in Supplementary Material Text S1.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Changes in Physical and Chemical Properties

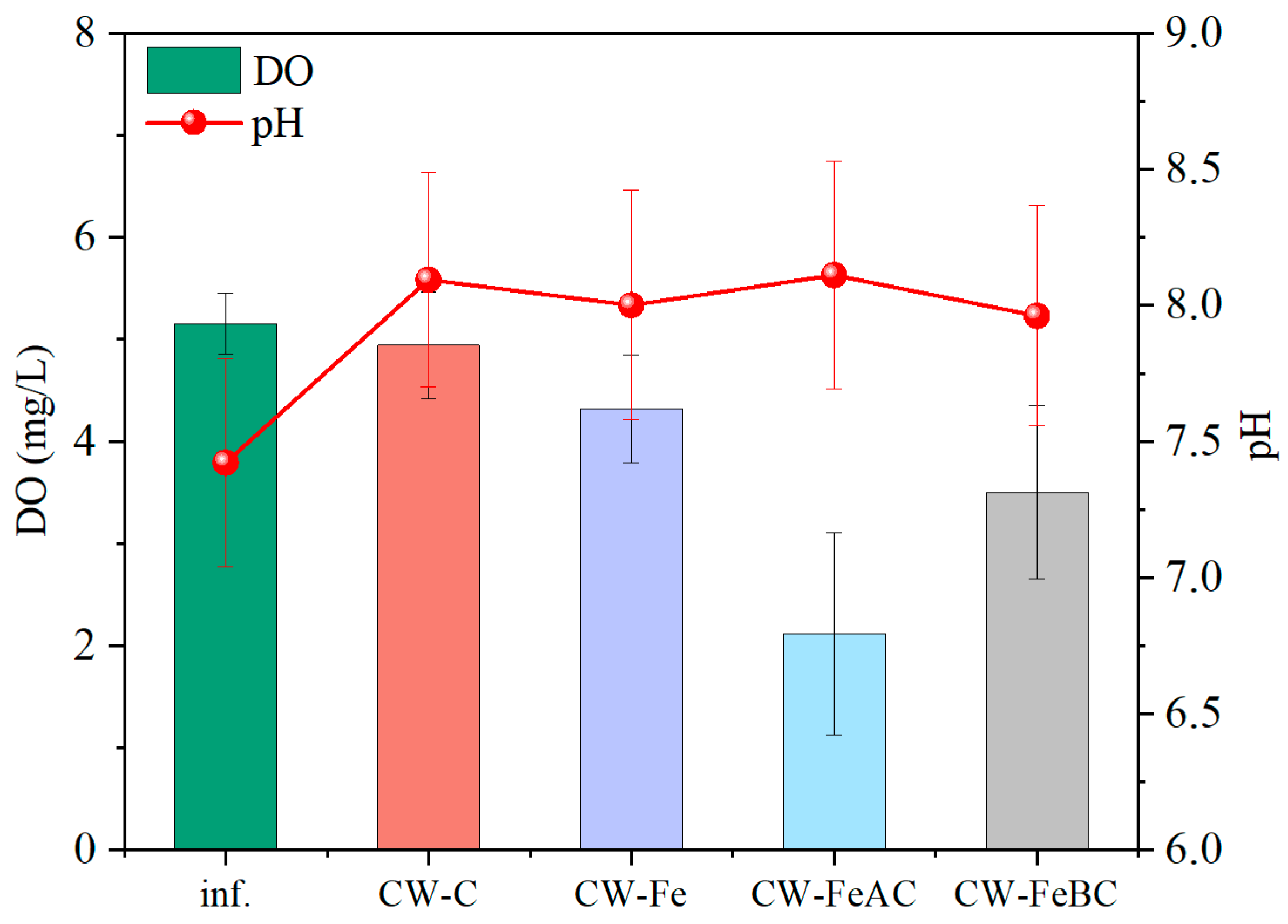

DO and pH are key parameters in the microenvironment of CWs, directly influencing microbial metabolic activity and pollutant transformation pathways, thereby playing an important regulatory role in the nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance. This study systematically analyzed the effects of Fe(0) and its combination with different carbon materials on the redox state and pH conditions by monitoring the dynamic changes in DO and pH in the influent and effluent of each wetland group. As shown in Figure 2, the average DO in the influent was 5.15 mg/L. After treatment in the wetland systems, the effluent DO decreased to varying degrees. The CW-C exhibited an effluent DO of 4.94 mg/L, while the CW-Fe showed a decrease to 4.32 mg/L. In contrast, the effluent DO levels in the CW-FeAC and CW-FeBC groups were further reduced to 2.12 mg/L and 3.50 mg/L, respectively. These results indicated that the combination of Fe(0) and carbon materials significantly enhanced DO consumption, with AC exhibiting a stronger promoting effect than BC. This can be attributed to the micro-electrolytic structure formed between iron and carbon, which accelerates the corrosion of Fe(0) and continuously consumes DO. The lower DO environment provides favorable anaerobic conditions for denitrifying bacteria, thereby contributing to improved nitrogen removal [25,26].

Figure 2.

The variation in DO and pH.

The average pH of the influent was 7.42. The effluent pH values of CW-C, CW-Fe, CW-FeAC, and CW-FeBC increased to 8.10, 8.00, 8.11, and 7.96, respectively, indicating the occurrence of denitrification to varying degrees in all systems. Statistical analysis revealed no significant differences in effluent pH among the groups (p > 0.05), suggesting that the addition of Fe(0) and carbon materials had a limited impact on the overall acidity and alkalinity of the systems, without causing significant pH fluctuations.

3.2. The Nitrogen Removal Performance

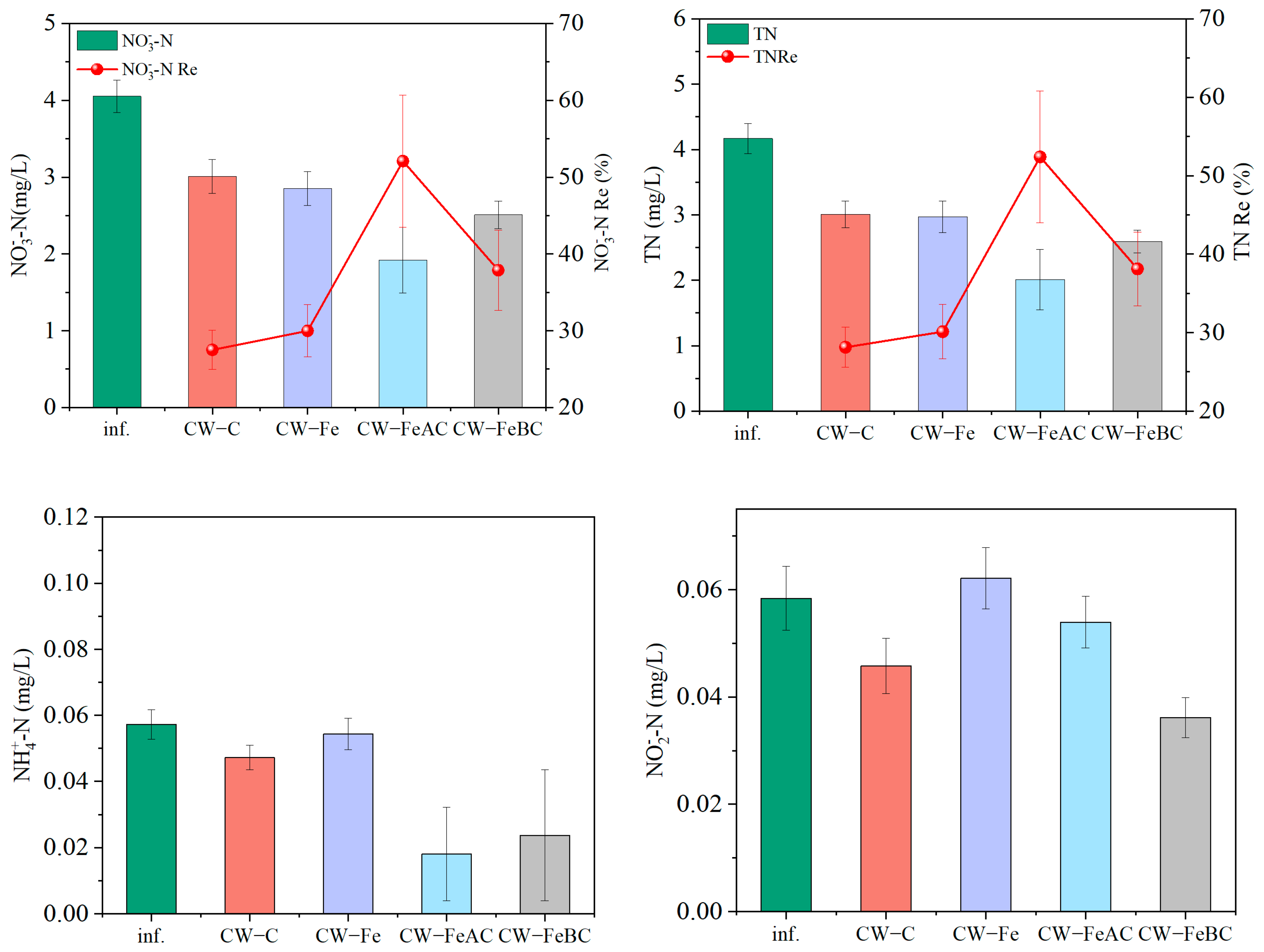

Figure 3 illustrates the temporal variation of nitrogen species (NO3−-N, TN, NH4+-N, and NO2−-N) in the influent and effluent of the different CW systems during the experimental period. The influent NO3−-N concentration remained relatively stable at approximately 4.05 mg/L, providing a consistent baseline for evaluating nitrogen removal performance. In the control group CW-C, the effluent NO3−-N concentration decreased only slightly to around 3.01 mg/L, corresponding to a removal efficiency of 28%. This modest reduction suggests that control CWs exhibit limited NO3−-N removal capacity, which may be ascribed to incomplete or slow denitrification under the prevailing redox conditions. The relatively low content of electron donors in the CW-C likely constrained the full reduction of NO3−-N to N2, leaving residual NO3−-N in the effluent. In the Fe(0)-amended system (CW-Fe), the effluent NO3−-N concentration was 2.85 mg/L, with a removal efficiency of 30%. This slight improvement over CW-C indicates that Fe(0) addition provided some enhancement of denitrification, likely by releasing Fe(II) as a potential electron donor. However, the improvement remained limited, which can be attributed to the rapid passivation of Fe(0) surfaces. The accumulation of a dense oxide layer reduces the reactivity of Fe(0), impedes continuous electron transfer, and consequently diminishes the long-term nitrogen removal performance. These results highlight the challenge of maintaining Fe(0) activity in wetland environments, particularly over extended operational periods.

Figure 3.

Temporal variations of nitrogen species (NO3−-N, TN, NH4+-N, NO2−-N) in the influent and effluent of different CW systems.

Remarkably, the combined addition of Fe(0) with carbonaceous materials led to a pronounced decrease in effluent NO3−-N concentration. In CW-FeAC and CW-FeBC, the effluent NO3−-N decreased to 1.92 and 2.51 mg/L, corresponding to removal efficiencies of 52% and 38%, respectively. These findings demonstrate that Fe–C coupled systems substantially enhanced denitrification performance compared to both CW-C and CW-Fe. The improvement can be explained by two synergistic mechanisms. First, the close contact between Fe(0) and carbon materials facilitates the formation of a micro-electrolytic cell, which accelerates electron transfer and generates localized reducing conditions favorable for the reduction of NO3−-N to N2. Second, AC, due to its high-temperature pyrolysis origin, possesses a highly graphitized structure and superior electrical conductivity [27,28]. This property not only promotes Fe(0) corrosion and sustained Fe(II) release but also provides additional electron transfer pathways, thereby reinforcing the denitrification process. Compared with BC, AC exhibited superior performance, likely due to its larger specific surface area, more abundant conductive sites, and stronger ability to support microbial process.

The removal trend of TN was generally consistent with that of NO3−-N. The influent TN concentration averaged 4.17 mg/L, while effluent TN concentrations from CW-C, CW-Fe, CW-FeAC, and CW-FeBC were 3.01, 2.97, 2.00, and 2.59 mg/L, corresponding to removal efficiencies of 28%, 30%, 58%, and 38%, respectively. We calculated the TN removal load, which was 0.087, 0.090, 0.162, and 0.118 mg/m2/d of CW-C, CW-Fe, CW-FeAC, and CW-FeBC, respectively. Among these, CW-FeAC achieved the highest TN removal efficiency, highlighting the pronounced synergistic effect between Fe(0) and AC. This synergy is likely attributable to the enhanced electron transfer facilitated by the Fe–C micro-electrolytic system and the superior conductivity of AC, which together promoted more efficient denitrification and overall nitrogen reduction. In contrast, CW-FeBC exhibited a moderate TN removal efficiency (38%), which, although improved compared to CW-C and CW-Fe, was notably lower than CW-FeAC. This difference may be explained by the physicochemical properties of BC, which typically has a less graphitized structure, lower conductivity, and fewer active sites than AC [29]. Consequently, its capacity to accelerate Fe(0) corrosion and stimulate microbial denitrification was comparatively weaker.

Regarding reduced nitrogen species, the influent NH4+-N and NO2−-N concentrations were relatively low, averaging 0.057 and 0.058 mg/L, respectively. All CW systems achieved certain levels of removal for these species; however, no statistically significant differences were observed among treatments. This outcome is likely due to the low influent concentrations, which minimized the observable impact of functional material amendments. It also suggests that the primary contribution of Fe–C coupling in this study was directed toward nitrate and TN removal rather than ammonium or nitrite, whose baseline concentrations were insufficient to exert a strong influence on system performance. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that Fe–C coupling, especially with AC, is an effective strategy for enhancing TN removal in constructed wetlands. The results further underline the importance of optimizing the physicochemical properties of carbon materials to maximize synergies with Fe(0) for sustained nitrogen removal efficiency.

3.3. Phosphorus Removal Performance

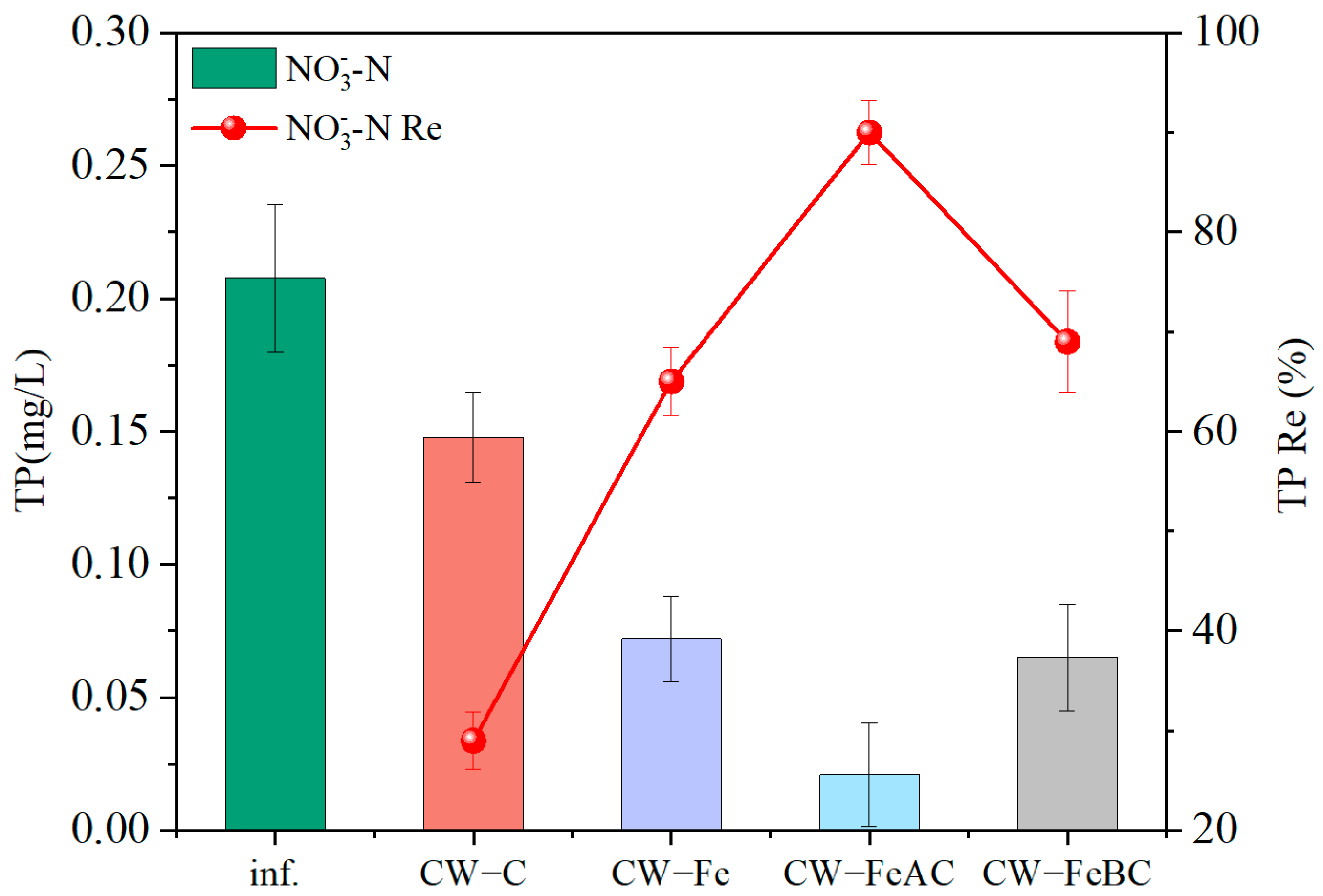

Efficient phosphorus removal is a critical strategy for mitigating eutrophication in aquatic ecosystems. In CWs, phosphorus is mainly removed through substrate adsorption, precipitation, microbial transformation, and plant uptake [30,31]. In this study, the enhancement of TP removal by Fe(0) and its coupling with different carbon materials was systematically evaluated. As shown in Figure 4, the influent TP concentration averaged 0.21 mg/L, and all CW systems exhibited a certain degree of phosphorus removal. In the CW-C, effluent TP decreased to 0.15 mg/L (29% removal), indicating limited efficiency when relying mainly on substrate adsorption and plant assimilation. The introduction of Fe(0) greatly improved phosphorus removal efficiency. In CW-Fe, effluent TP was reduced to 0.07 mg/L, corresponding to a removal efficiency of 65%. We calculated the TP removal load, which was 0.0045, 0.0102, 0.014, and 0.0107 mg/m2/d of CW-C, CW-Fe, CW-FeAC, and CW-FeBC, respectively. This improvement can be attributed to the generation of iron corrosion products, including amorphous and crystalline iron (oxyhydr)oxides, which are formed as Fe2+ released from Fe(0) oxidation is further oxidized to Fe3+. These reactive solids possess high surface area and abundant hydroxyl groups, enabling effective phosphorus immobilization through ligand exchange and co-precipitation with phosphate ions [32]. The presence of Fe(0) thus provided a stable and reactive sink for phosphorus removal beyond the natural capacity of CW substrates and vegetation.

Figure 4.

TP variation and removal efficiency of the CWs during the experimental period.

When Fe(0) was combined with carbon materials, TP removal performance was further enhanced. In CW-FeAC, effluent TP decreased to 0.02 mg/L (90% removal), while CW-FeBC achieved 0.05 mg/L (76% removal). The superior performance of the Fe–AC system highlights a strong synergistic effect, likely due to the highly porous structure and strong adsorption affinity of AC, which facilitated both direct phosphate binding and Fe–P precipitates [33]. Moreover, the higher electrical conductivity of AC promoted galvanic coupling with Fe(0), accelerating Fe(0) corrosion and ensuring a continuous supply of reactive Fe(II)/Fe(III) species for phosphorus sequestration. In contrast, BC, with its less graphitized structure and lower conductivity, provided weaker electrochemical and adsorption support, resulting in comparatively lower TP removal efficiency. Overall, these results demonstrate that Fe(0) plays a pivotal role in enhancing phosphorus removal in CWs, and its coupling with carbon materials—particularly AC—establishes a more efficient and sustainable removal pathway. The Fe–C systems not only provide additional adsorption sites and chemical binding capacity but also create favorable electrochemical conditions that sustain long-term phosphorus removal from wastewater.

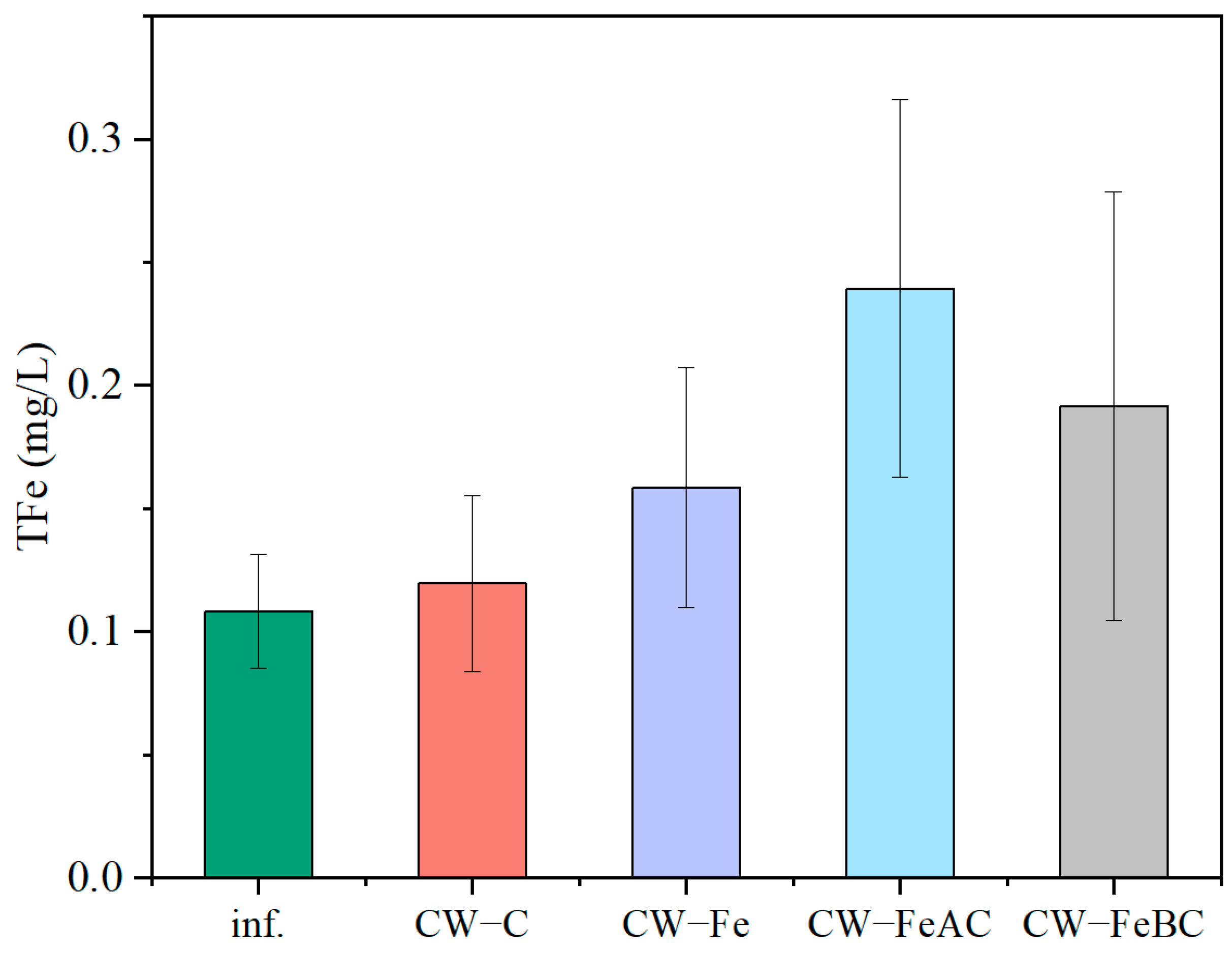

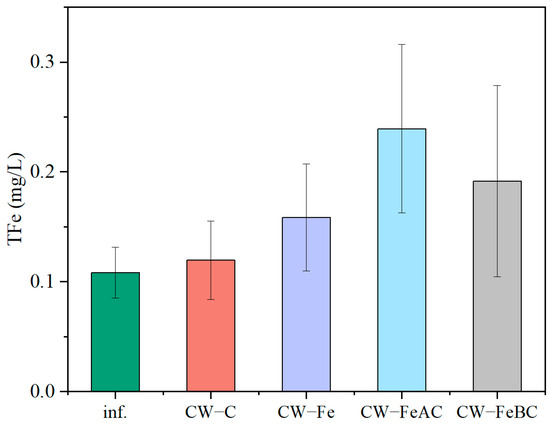

3.4. The Changes in the TFe Content

The release of active components from iron-based materials is a key indicator for evaluating both the stability and potential environmental risks of CW systems. In this study, TFe concentrations in the effluent of each unit were monitored to investigate the release behavior of Fe(0) and its coupling with carbon materials, and to explore its relationship with nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance (Figure 5). The influent TFe concentration was approximately 0.11 mg/L. In CW-C, the effluent TFe remained nearly unchanged at 0.12 mg/L, indicating negligible iron release and highlighting the stability of conventional wetland substrates without Fe(0) addition. In contrast, effluent TFe in CW-Fe increased to 0.16 mg/L, directly confirming the corrosion and dissolution of Fe(0) in the wetland aquatic environment. This release provides a continuous source of Fe2+ and Fe3+ species, which can serve as electron donors for microbial denitrification and as reactive sites for phosphate immobilization, linking material dissolution to enhanced nutrient removal.

Figure 5.

TFe variation in the CWs during the experimental period.

When Fe(0) was coupled with carbon materials, iron release was further promoted. The highest effluent TFe (0.25 mg/L) was observed in CW-FeAC, significantly exceeding that of CW-Fe and CW-FeBC. This enhancement suggests that the micro-electrolytic effect between Fe(0) and AC accelerated anodic corrosion of Fe(0) [34]. The increased iron release reflects the most intense micro-electrochemical activity in the CW-FeAC system, facilitating a higher generation rate of Fe2+/Fe3+ species and thus providing a more sustained supply of electron donors and reactive adsorption sites.

The observed correlation between TFe release and nutrient removal performance underscores the mechanistic role of iron in enhancing CW efficiency. The CW-FeAC system, with its pronounced iron dissolution, exhibited the highest nitrogen and phosphorus removal, demonstrating that accelerated Fe(0) corrosion via Fe–C micro-electrolysis not only improves the supply of electrons for denitrification but also promotes phosphate precipitation and adsorption. These findings highlight that coupling Fe(0) with conductive carbon materials, particularly AC, can simultaneously optimize material reactivity and nutrient removal efficiency, offering a sustainable strategy for engineered wetland design and operation.

3.5. Analysis of Microbial Community Structure

Table 1 presents the α-diversity indices of the microbial communities in all wetland systems. The coverage index for all samples exceeded 95%, indicating that sufficient sequence data were obtained to reliably characterize the microbial community structure. In terms of microbial richness, as represented by the Chao1 and ACE indices, the CW-FeAC group exhibited the lowest values. Regarding microbial diversity, however, the CW-FeAC group showed the highest Shannon and Simpson indices, suggesting that the addition of Fe(0) coupled with AC increased the variety of microbial species but reduced their overall abundance. The increase in microbial diversity is conducive to enhancing the nitrogen and phosphorus removal performance of CWs.

Table 1.

The α-diversity indices of all the microbial samples.

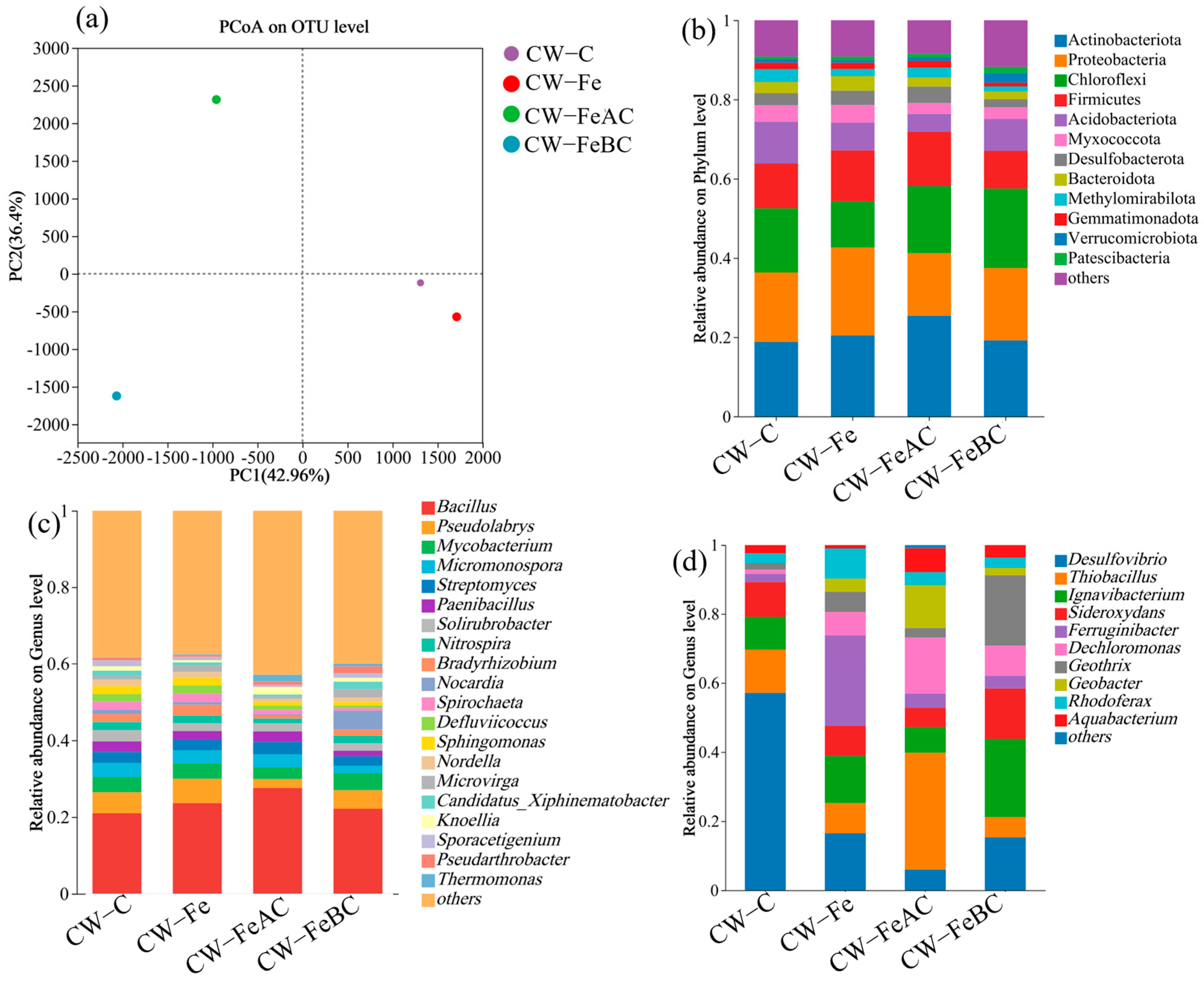

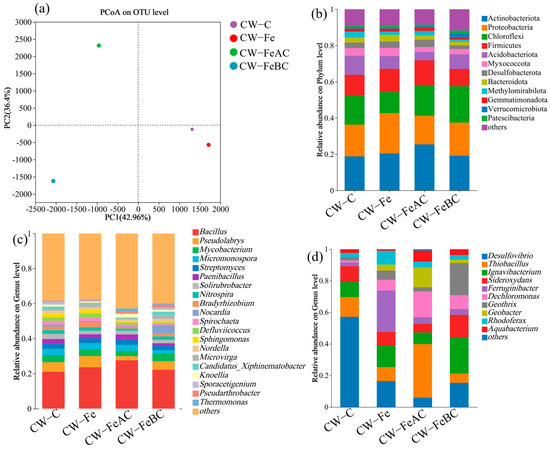

The structural characteristics of microbial communities directly determine the ecological functions of CW systems. To investigate the regulatory effects of different materials on the microbial communities, a principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was performed based on the OTU level, with the results shown in Figure 6a. The PCoA revealed that the first two principal coordinates (PC1 and PC2) together explained 79.36% of the total variation in microbial β-diversity (PC1: 42.96%; PC2: 36.4%), indicating that these axes effectively capture the core differences among samples. The sample points representing different treatment groups showed clear spatial separation. The distribution along the PC1 axis reflected the ecological effects induced by different filling materials. The CW-C was distinctly separated from the other groups, suggesting fundamental differences in microbial community structure compared to other systems, which corresponds to its relatively weak pollutant removal performance. The microbial community structure in the CW-Fe shifted significantly relative to CW-C, likely due to the unique microenvironment created by Fe(0) corrosion—such as lower redox potential and continuous release of Fe2+—which selectively enriched key microbial populations involved in iron reduction, iron oxidation, or denitrification using iron as an electron donor.

Figure 6.

(a) PCoA analysis of microbial communities; (b) Relative abundance at the phylum level; (c,d) Relative abundance of key genera involved in nitrogen and iron cycling.

The sample points of CW-FeAC and CW-FeBC were located close to each other, indicating a relatively similar microbial community structure. However, the two groups did not fully overlap, suggesting that while the iron–carbon micro-electrolysis process imparted common features to the microbial communities, the distinct properties of the carbon materials also led to specific structural differences. This gradient distribution along the PC1 axis demonstrated that the addition of functional materials is a key environmental factor driving microbial community assembly, with varying degrees of influence depending on the material type.

The relative abundance of microbial communities at the phylum level was analyzed, and the results were shown in Figure 6b. In all CWs, Actinobacteriota, Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, and Firmicutes were identified as the dominant phyla, collectively accounting for 63.87% to 71.83% of the total sequences. Among these, Proteobacteria includes numerous known genera involved in nitrogen and phosphorus removal [35,36], and its dominance suggested a functional potential for nutrient transformation in the systems. Compared to CW-C and CW-Fe, the addition of carbon materials altered the microbial community structure at the phylum level. In the CW-FeBC, the relative abundance of Chloroflexi increased to 20.06%. As Chloroflexi are capable of degrading complex organic matter, this increase may reflect enhanced biodegradation facilitated by the coupling of iron and BC, which can release residual organic compounds due to its low-temperature pyrolysis. The relative abundance of Firmicutes increased to 13.73% in the CW-FeAC. Firmicutes include various bacteria capable of anaerobic fermentation and denitrification [35], and their enrichment may be associated with the low redox potential environment created by the Fe(0)-AC combination, where Fe(0) serves as an electron donor supporting their metabolic activities. Additionally, the relative abundance of Desulfobacterota, a phylum closely associated with denitrification, increased in the iron–carbon coupled systems (4.12%). Certain species within this phylum can perform not only sulfate reduction but also participate in denitrification processes [37,38]. The iron–carbon micro-electrolysis environment appears to create a distinct habitat that selectively enriches specific functional microbial groups.

The relative abundances of functional genera involved in nitrogen and iron cycling in different systems are shown in Figure 6c,d. The results indicated that the addition of different functional materials altered the community structure of functional microorganisms, and the observed succession patterns were highly consistent with the nitrogen removal performance. In terms of nitrogen-cycling functional genera, Bacillus was one of the most dominant genera across all samples. Its relative abundance increased in the amended systems, reaching 23.66% in CW-Fe, 27.60% in CW-FeAC, and 22.17% in CW-FeBC. As a metabolically versatile genus, many Bacillus species are capable of denitrification [39,40] and can form spores to withstand unfavorable conditions. Thermomonas was significantly enriched in the CW-FeAC, with a relative abundance of 1.76%. As an aerobic denitrifier, the increase in Thermomonas suggests that the AC addition enhanced iron corrosion, supplying more electron donors (Fe0 or Fe2+) for denitrification and thereby promoting the enrichment of such functional bacteria. Furthermore, denitrifying genera such as Paenibacillus also showed a notable increase. Together, these genera form a functionally diverse and structurally complex nitrogen transformation network, supporting efficient denitrification in the systems.

Iron cycling and nitrogen cycling are closely coupled at the microbial metabolic level. As indicated by the relative abundances of iron-cycling functional genera, significant changes were observed in groups amended with functional materials for taxa involved in iron oxidation and reduction, such as Ferruginibacter, Thiobacillus, Geothrix, and Geobacter. Ferruginibacter, which has been reported to participate in denitrification [41] and iron oxide transformation, was significantly enriched in the CW-Fe (26.21%). Thiobacillus, a typical iron-oxidizing nitrate-reducing bacterium [42], showed the highest relative abundance in the CW-FeAC system (33.80%). Iron oxidation—iron reduction” coupled cycle forms a self-sustaining, closed-loop electron shuttle within the system. This cycle is of high ecological significance because it efficiently couples the iron and nitrogen biogeochemical pathways, ensuring a continuous supply of electron donors (Fe2+) and acceptors (Fe3+) to drive autotrophic denitrification. This internal recycling mechanism enhances the stability and efficiency of nutrient removal by creating a resilient microbial network that minimizes the accumulation of inhibitory intermediates and reduces the system’s dependence on external substrates. Geothrix and Geobacter, both known as dissimilatory iron-reducing bacteria capable of utilizing Fe(III) as an electron acceptor, compete or synergize with NO3−-N reduction processes. Their highest abundances were observed in the CW-FeBC (20.44%) and CW-FeAC (12.5%) systems, respectively.

The iron–carbon coupling reconfigured the microbial community structure in CWs by modulating the abundance and composition of key genera involved in nitrogen and iron cycling. Fe(0) served as an electron donor, directly or indirectly driving the denitrification process. Moreover, when Fe(0) was coupled with AC, the resulting galvanic cell effect accelerated the corrosion of iron and facilitated iron cycling (Fe2+/Fe3+ transformation). This process not only supplied a more sustained electron flow for denitrification but also created a dynamic redox microenvironment conducive to the coexistence and collaboration of diverse functional microorganisms. For instance, the chemolithoautotrophic denitrifier Thiobacillus could directly utilize Fe2+ generated from iron oxidation as an electron donor to enhance denitrification. Simultaneously, the iron-reducing bacterium Geobacter, enriched in the CW-FeAC system, reduced Fe(III) to Fe(II), thereby supplying electrons for Thiobacillus and contributing to highly efficient nitrogen removal.

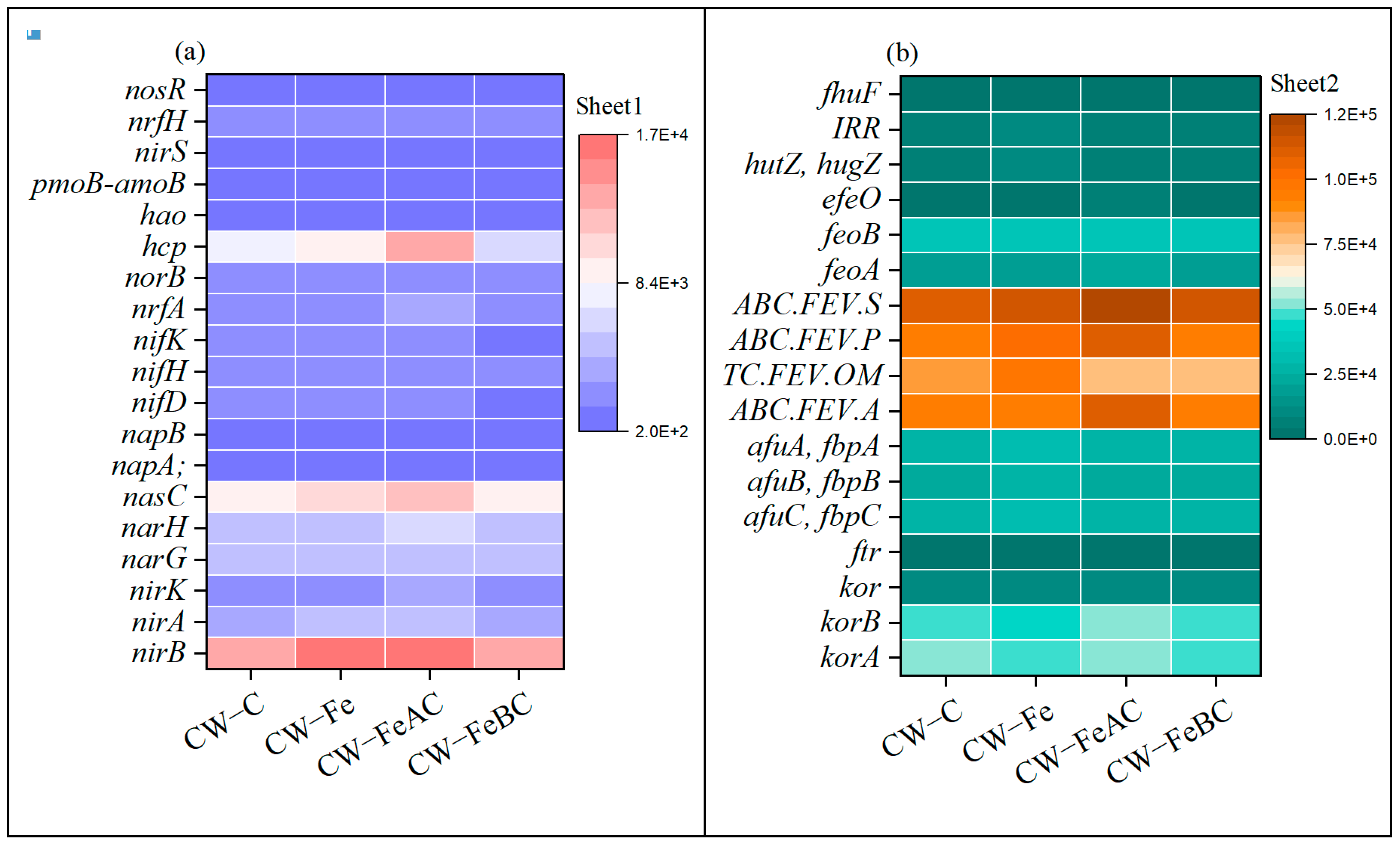

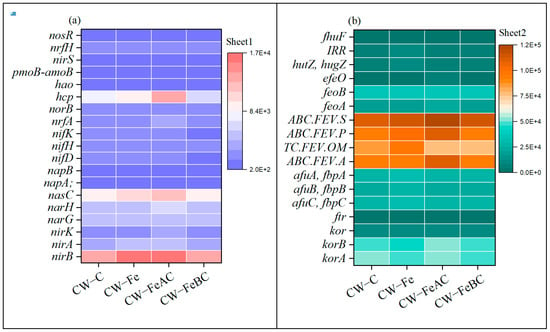

3.6. Function Prediction

To achieve a comprehensive understanding of nitrogen transformation in iron–carbon coupled CWs, this study analyzed functional genes associated with nitrogen metabolism and iron cycling based on the KEGG database (Figure 7). The heatmap of nitrogen-cycling functional genes (Figure 7a) demonstrates that the addition of functional materials markedly altered the abundance of nitrogen transformation genes. Compared with the control group, most genes involved in denitrification were enriched after material amendment, particularly in the Fe–AC system, highlighting the stimulatory effect of material addition on nitrogen-cycling function. Specifically, the NO3−-N reductase genes napA and narG, encoding Nap and Nar enzymes [43], exhibited the highest relative abundances in the CW-FeAC group, reaching 0.0017% and 0.0072%, respectively, indicating a strong potential for NO3−-N reduction. The NO2−-N reductase gene nirS also showed elevated abundances in the iron–carbon coupled systems, particularly in CW-FeAC (0.00073%) and CW-FeBC (0.00071%), reflecting enhanced NO2−-N conversion. Furthermore, nosZ, which encodes N2O reductase, was most abundant in CW-FeAC (0.0030%), followed by CW-FeBC (0.0026%), suggesting that the addition of carbon—especially AC—promotes complete denitrification by facilitating the reduction of the potent greenhouse gas N2O to N2.

Figure 7.

Heatmaps of functional genes associated with nitrogen cycle (a) and iron cycle (b).

Analysis of iron-cycling functional genes (Figure 7b) provides another critical perspective for interpreting the coupling mechanism. Iron and nitrogen cycling are closely linked at the microbial metabolic level. The results indicate that a series of genes related to iron uptake, storage, and transport—such as feoA, feoB (Fe2+ transport) [44], korB (ferredoxin oxidoreductase) [45], and afuB (iron complex outer membrane receptor protein) [44] were significantly enriched in the CW-FeAC group compared with other systems, indicating highly active microbial iron metabolism. Notably, feoA (0.030%) and feoB (0.048%) exhibited the highest abundances in CW-FeAC, suggesting more efficient microbial uptake and utilization of Fe2+ released from Fe(0) corrosion. These iron ions can then be transported via receptor proteins and integrated into microbial iron metabolism, participating in redox cycling and maintaining a dynamic pool of bioavailable iron. The enhanced iron cycling effectively provides a continuous and stable “electron source” for microbial communities, thereby facilitating denitrification and other nitrogen transformation processes.

Collectively, the coordinated enrichment of both nitrogen- and iron-cycling functional genes in CW-FeAC underscores the critical role of AC in stimulating microbial activity, accelerating Fe(0) corrosion, and reinforcing the Fe–N micro-electrochemical system. This genetic-level evidence provides a mechanistic explanation for the superior nitrate and total nitrogen removal observed in CW-FeAC, highlighting the importance of conductive carbon materials in optimizing microbial-mediated nutrient cycling in CWs.

3.7. Limitations and Future Perspectives

While this study demonstrates the significant potential of iron–carbon micro-electrolysis for enhancing nutrient removal in constructed wetlands (CWs) treating low-pollution water, several limitations should be acknowledged. Firstly, the experiment was conducted at the laboratory pilot scale under controlled greenhouse conditions. The long-term efficacy and stability of the system under full-scale, real-world environmental fluctuations (e.g., temperature variations, hydraulic shocks, and diverse water matrices) remain to be validated. Secondly, the internal mechanisms were primarily elucidated through microbial community analysis and functional gene prediction. Direct experimental evidence quantifying the specific contributions of distinct nutrient removal pathways (e.g., the proportion of nitrogen removal via autotrophic denitrification driven by Fe(II) versus heterotrophic processes) was not obtained. Lastly, the potential for long-term accumulation of iron and its possible ecological impacts on the wetland ecosystem require further investigation over extended operational periods. Based on these limitations, future research should focus on the following directions: (1) Scale-up and Field Validation: Implementing long-term, large-scale demonstration projects to evaluate the technological and economic feasibility of iron-carbon-enhanced CWs for treating actual low-pollution water bodies, such as river influents or wastewater treatment plant effluents. (2) Mechanistic Elucidation: Employing advanced techniques, such as isotope tracing (e.g., 15N) and metatranscriptomics, to precisely quantify the fluxes of different nitrogen transformation pathways and identify the active functional microorganisms responsible for the synergistic effects. (3) Material Optimization and Environmental Impact: Exploring the synthesis and application of novel iron–carbon composite materials with optimized physicochemical properties to enhance electron transfer efficiency and longevity. Concurrently, a comprehensive assessment of the life cycle and potential environmental risks associated with the long-term use of iron-based materials in wetlands is essential.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically evaluated the effects of coupling Fe(0) with AC or BC on the treatment of low-pollution water in CWs. Results demonstrated that iron–carbon micro-electrolysis significantly enhanced nitrogen and phosphorus removal. The CW-FeAC system achieved the highest efficiencies, with 58% TN and 90% TP removal, substantially outperforming the control and Fe(0)-only systems. Microbial community analysis revealed that the AC addition specifically enriched key functional genera such as Thiobacillus (33.8%) and Geobacter (12.5%), establishing a coupled microbial nitrogen removal pathway involving iron oxidation, iron reduction, and NO3−-N reduction. Functional gene analysis further revealed that CW-FeAC possessed the most complete denitrification pathway and the most active iron metabolism genes (feoA/feoB), corroborating its superior performance. These findings elucidate the electrochemical–microbial synergy in iron–carbon enhanced CWs, providing a theoretical basis and a technical strategy for optimizing the design of constructed wetlands using conductive carbon materials (e.g., activated carbon) to treat low-pollution water.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17213139/s1, Text S1: Detailed steps of high-throughput sequencing; Figure S1: A schematic of galvanic cell; Figure S2: Pictures of iron scraps and carbon materials; Figure S3. Differences in the functional composition of microorganisms in different CWs; Table S1: Main elements of iron scraps used in the experiment (wt %); Table S2: Physiochemical properties of biochar, activated carbon; Table S3. Mass loss of iron scraps and carbon materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.R. and X.Z.; methodology, D.W. and J.S.; software, S.S.; validation, X.R. and S.H.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, X.R. and J.S.; data curation, S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S.; writing—review and editing, S.H.; supervision, S.H.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basic research program of Yunnan Province (No. 202401AT070273), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52170167, No. 52300213), 2025 Key Research Initiatives of Yunnan Erhai Lake National Ecosystem Field Observation Station (No. 2025ZD01), and the project from Yunnan Provincial Communications Investment Construction Group Co., Ltd. (No. YCIC-YF-2024-01).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Xiaojiao Ren, Xuejin Zhou and Di Wu were employed by the company Yunnan Communications Investment Eco-Tech Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from the Basic research program of Yunnan Province, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, 2025 Key Research Initiatives of Yunnan Erhai Lake National Ecosystem Field Observation Station, and the project from Yunnan Provincial Communications Investment Construction Group Co., Ltd. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Zhang, L.; Cui, B.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, A.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Pan, L.; Li, L. Denitrification Mechanism and Artificial Neural Networks Modeling for Low-Pollution Water Purification Using a Denitrification Biological Filter Process. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 257, 117918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Cui, B.; Yuan, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, A.; Han, X.; Pan, L. Purification mechanism of low-pollution water in three submerged plants and analysis of bacterial community structure in plant rhizospheres. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2019, 37, 560–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, X.; Sun, S.; Yan, P.; Fan, Y.; Xi, Y.; He, S. Trade-off between electrochemical and microbial nutrient eliminations in iron anode-assisted constructed wetlands: The specificity of voltage level. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 377, 124623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Wang, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; He, Q. Sulfur and iron cycles promoted nitrogen and phosphorus removal in electrochemically assisted vertical flow constructed wetland treating wastewater treatment plant effluent with high S/N ratio. Water Res. 2019, 151, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhai, X.; Hu, M.; Chang, J.; Lee, D. Atypical removals of nitrogen and phosphorus with biochar-pyrite vertical flow constructed wetlands treating wastewater at low C/N ratio. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 422, 132219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zhou, Q.; Li, Y.; Wu, W. Integrated Treatment of Suburb Diffuse Pollution Using Large-Scale Multistage Constructed Wetlands Based on Novel Solid Carbon: Nutrients Removal and Microbial Interactions. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 326, 116709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, K.; Lu, S.; Guo, X.; Zhang, J.; Xi, B. Removal of Nitrogen from Low Pollution Water by Long-Term Operation of an Integrated Vertical-Flow Constructed Wetland: Performance and Mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 652, 977–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.; Gu, X.; Lai, W.; Fan, Y.; Sun, S.; Yan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, X.; He, S. Sulfur-iron interactions forming activated FexSy pool in-situ to synergistically improve nitrogen removal in denitrification system. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 388, 126047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Li, D.; Yang, X.; Zhu, S.; Li, J. Process of Nitrogen Transformation and Microbial Community Structure in the Fe(0)–Carbon-Based Bio-Carrier Filled in Biological Aerated Filter. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 6621–6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcello, E.; Herpain, A.; Tomatis, M.; Turci, F.; Jacques, P.; Lison, D. Hydroxyl radicals and oxidative stress: The dark side of Fe corrosion. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 185, 110542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, S.; Li, D.; Yang, X.; Xing, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q. Iron [Fe(0)]-Rich Substrate Based on Iron–Carbon Micro–Electrolysis for Phosphorus Adsorption in Aqueous Solutions. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 1486–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Dai, W.; Zheng, P.; Zheng, X.; He, S.; Zhao, M. Iron Scraps Enhance Simultaneous Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal in Subsurface Flow Constructed Wetlands. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 395, 122612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, L.; Ou, Y.; Yan, B.; Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Cheng, L.; Jiao, P. Synergistic Improvement of Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal in Constructed Wetlands by the Addition of Solid Iron Substrates and Ferrous Irons. Fundam. Res. 2023, 3, 890–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.-S.; Ding, R.-R.; Chen, J.Q.; Li, W.Q.; Li, Q.; Mu, Y. Interactions between Nanoscale Zero Valent Iron and Extracellular Polymeric Substances of Anaerobic Sludge. Water Res. 2020, 178, 115817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, J.; Wu, P.; Yang, F.; Chen, B.; Wang, Y.; Meng, G.; Kong, Q.; Fang, J.; Wu, H. Enhanced Nitrogen Removal and Greenhouse Gas Reduction via Activated Carbon Coupled Iron-Based Constructed Wetlands. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 66, 106098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M.; Niu, J. Numerical Simulation of the Hydrodynamic Behavior and the Synchronistic Oxidation and Reduction in an Internal Circulation Micro-Electrolysis Reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 381, 122709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Hu, Q.; Deng, S. Nitrate Removal and Microbial Analysis by Combined Micro-Electrolysis and Autotrophic Denitrification. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 211, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, Z.M.; Rogers, M.; Davis, M.; Wade, J.; Eick, M.; Bock, E. Mitigation of Sulfate Reduction and Nitrous Oxide Emission in Denitrifying Environments with Amorphous Iron Oxide and Biochar. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 82, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xu, F.; Yang, C.; Su, X.; Guo, F.; Xu, Q.; Peng, G.; He, Q.; Chen, Y. Highly efficient nitrate removal in a heterotrophic denitrification system amended with redox-active biochar: A molecular and electrochemical mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. 2019, 275, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Lee, S.S.; Dou, X.; Mohan, D.; Sung, J.K.; Yang, J.E.; Ok, Y.S. Effects of Pyrolysis Temperature on Soybean Stover- and Peanut Shell-Derived Biochar Properties and TCE Adsorption in Water. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 118, 536–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, M.; Gao, B.; Pullammanappallil, P.; Ding, W.; Zimmerman, A.R. Biochar from Anaerobically Digested Sugarcane Bagasse. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 8868–8872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, J.; Rillig, M.C.; Thies, J.; Masiello, C.A.; Hockaday, W.C.; Crowley, D. Biochar Effects on Soil Biota—A Review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Bian, S.; Wang, H.; Chu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Song, Y.; Fang, C. Responses of nitrogen removal, microbial community and antibiotic resistance genes to biodegradable microplastics during biological wastewater treatment. Biochem. Eng. J. 2025, 219, 109732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Tao, R.; Zhang, X.; Dao, Y.; Yang, Y. Micropollutant removal efficiency and microbial community of different hybrid constructed wetland systems. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocaoglu, S.M.; Insel, G.; Cokgor, E.U.; Orhon, D. Effect of Low Dissolved Oxygen on Simultaneous Nitrification and Denitrification in a Membrane Bioreactor Treating Black Water. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 4333–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Ma, Z.; Qin, Y.; Wu, H.; Xu, X.; Xin, L.; Wu, W. Pilot-Scale Study of Step-Feed Anaerobic Coupled Four-Stage Micro-Oxygen Gradient Aeration Process for Treating Digested Swine Wastewater with Low Carbon/Nitrogen Ratios. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 380, 129087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Balmaceda, A.; Rojas-Candia, V.; Arismendi, D.; Richter, P. Activated carbon from avocado seed as sorbent phase for microextraction technologies: Activation, characterization, and analytical performance. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 2399–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Yin, M.; Nie, S.; Xiao, X.; Chu, C.; Chen, B. Pyrogenic Carbon Enhances Hydroxyl Radical Generation during Microbial Transformation of Ferrihydrite at Redox Interfaces. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 12692–12702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Feng, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Wu, R. Research Progress of Phosphorus Adsorption by Attapulgite and Its Prospect as a Filler of Constructed Wetlands to Enhance Phosphorus Removal from Mariculture Wastewater. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M.; Liang, J.; Zhang, J.; Meng, F.; Li, S.; Jia, Q.; Liu, H.; Chen, X.; Jiang, H. Advanced Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal from Municipal Tailwater in Sulfur-Based Constructed Wetland Strengthened by Boron Oxide and Magnesium Oxide at Low Temperatures: Role of Multipath Autotrophic Pathways. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 200, 107384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fu, S.; Han, Y.; Zheng, J.; Wang, C.; Xu, X.; Zhu, L. Synergistic Removal of Carbon and Phosphorus by Modified Carbon-Based Magnetic Materials. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 151244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.; Basiouny, M.E.; Abosiada, O.A. Activated Carbon and Biochar Prepared from Date Palm Fiber as Adsorbents of Phosphorus from Wastewater. Desalination Water Treat. 2025, 321, 100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Jeyakumar, P.; Bolan, N.; Zhai, X.; Wang, H.; Pan, M.; Lian, J.; Cheng, L.; Li, J.; Hou, M.; et al. Enhanced Denitrification Driven by a Novel Iron-Carbon Coupled Primary Cell: Chemical and Mixotrophic Denitrification. Biochar 2024, 6, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Sun, S.; Gu, X.; Fan, Y.; He, S. Mechanistic insights into microplastic-mediated shifts in nitrogen metabolism and sensory quality across emergent and submerged-plant wetlands: Evidence from metagenomics and physiological indicators. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 498, 139937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, B. Effect of Temperature on Simultaneous Nitrogen and Phosphorus Removal and Microbial Community in Anaerobic-Aerobic-Anoxic Sequencing Batch Reactor. Desalination Water Treat. 2022, 253, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Huang, J.; Li, W.; Shi, Z.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, R.; Meng, J.; Tang, J.; Hou, P. Coupled Process of In-Situ Sludge Fermentation and Riboflavin-Mediated Nitrogen Removal for Low Carbon Wastewater Treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 363, 127928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wei, C.; Yang, Z.; Yang, L. The Enhancement of Autotrophic Denitrification by Manganese Carbonate on Sulfur-Pyrite Composite Filler and Its Biochemical Mechanism. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 76, 108156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bai, Y.; Xu, L.; Su, J.; Feng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, W.; Bai, J. Mechanistic insights and performance of Mn redox cycling in a dual-bacteria bioreactor for ammonium and Cr(VI) removal. Water Res. 2025, 268, 123713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, W.; Liu, G.; Yu, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, F.; Meng, X.; Cao, J. Metabolic Characteristics and the Cross-Feeding of Bacillus and Ca. Brocadia in an Integrated Partial Denitrification-Anammox Reactor Driven by Glycerol. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 111859. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Song, X.; Cheng, X.; Huang, Z.; Dong, D.; Li, X. Enhanced Denitrification of Biodegradable Polymers Using Bacillus Pumilus in Aerobic Denitrification Bioreactors: Performance and Mechanism. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 394, 130240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.; Chen, S.; Zhang, H.; Ma, Y.; Qu, Z.; Yan, N.; Zhang, Y.; Rittmann, B.E. The Roles of Rhodococcus Ruber in Denitrification with Quinoline as the Electron Donor. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 902, 166128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Dong, H.; Min, J.; Xu, H.; Sun, D.; Liu, X.; Dang, Y.; Qiu, B.; Mennella, T.; et al. Evidence of autotrophic direct electron transfer denitrification (DETD) by thiobacillus species enriched on biocathodes during deep polishing of effluent from a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sestok, A.E.; Brown, J.B.; Obi, J.O.; O’Sullivan, S.M.; Garcin, E.D.; Deredge, D.J.; Smith, A.T. A Fusion of the Bacteroides Fragilis Ferrous Iron Import Proteins Reveals a Role for FeoA in Stabilizing GTP-Bound FeoB. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sheng, Y.; Wang, G.; Zhou, P.; Liao, F.; Mao, H.; Zhang, H.; Qiao, Z.; Wei, Y. Spatiotemporal Successions of N, S, C, Fe, and As Cycling Genes in Groundwater of a Wetland Ecosystem: Enhanced Heterogeneity in Wet Season. Water Res. 2024, 251, 121105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Su, Y.; Xue, S.; Li, N.; Li, R.; Wang, S.; Bu, J.; Zhang, H.; Huang, T. Breaking through the Bottleneck of Nitrogen Pollution Control in Micropolluted Water Sources: Enhancement of Aerobic Denitrification Efficacy Driven by Microbial Community Enrichment and Its Sustainable Application. Water Res. 2025, 285, 124070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).