Abstract

An effective understanding of sediment deposition and erosion in river basins, particularly floodplains, is critical for modeling geomorphic evolution, managing flood risks, and maintaining ecological integrity. However, most related studies have been limited to hydraulic or hydrodynamic modeling approaches. Therefore, this study integrated Sentinel-1 differential interferometric synthetic aperture radar (DInSAR) coherence, Sentinel-2 normalized difference vegetation index, and soil surface moisture index data with one-dimensional hydraulic modeling to assess flood-induced sediment deposition and erosion in the Gamcheon River basin under non-flood, short flood, and long flood scenarios. The DInSAR deformation analysis revealed a clear pattern of upstream erosion and downstream deposition during flood events, indicating a total depositional uplift of 0.33 m during the long flood scenario but dominant erosion with a total measured surface lowering of −2.03 m during the non-flood scenario. These results were highly consistent with the predictions from the hydraulic model and supported by the hysteresis curves for in situ suspended sediment concentration. The findings of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed integrated approach for quantifying floodplain sediment dynamics, offering particular application value in data-scarce or inaccessible floodplains. Furthermore, the proposed approach provides practical insights into sediment management, flood risk assessment, and ecosystem restoration efforts.

1. Introduction

The sediments present in a watershed are generated by hillslope erosion and surface runoff, transported through channels by flowing water, and ultimately deposited in lower-energy zones [1]. Among these depositional environments, floodplains are dynamic zones that intermittently store and redistribute sediments during overbank flows. However, floodplains are not purely depositional; they may also experience localized erosion under certain hydraulic conditions. The interactions among hydraulic forces, sediment properties, vegetation, and topography create a complex set of processes that determine whether sediment is deposited or eroded across the floodplain surface [2]. These processes are influenced by the magnitude, duration, and timing of flooding as well as the antecedent moisture conditions. The complex interactions among these conditions can lead to spatially variable patterns of sedimentation and scouring. Understanding this sediment–floodplain exchange is not only essential for predicting long-term geomorphic evolution, but also for managing flood risks and maintaining ecological integrity. Indeed, given the increasing pressure placed on floodplains by urbanization and infrastructure development, the accurate characterization of these mechanisms has become a critical aspect of effective watershed planning and floodplain restoration [3,4]. In particular, the floodplains of Korean rivers face various challenges associated with vegetation expansion and other issues exacerbated by climate change [5]. An understanding of floodplain dynamics in conjunction with flow and sediment transport processes is essential for addressing these challenges and advancing floodplain management and sediment budgeting [6].

South Korea’s geography and climate create a dynamic sediment transport regime in its rivers. When the intense rainfall brought to the nation’s mountainous terrain by summer monsoons flows through its short, steep rivers, flood events generate significant sediment loads with yields ranging from 5 to 1500 tons/km2·yr. Monitoring has shown that upstream tributaries supply a disproportionate share of this sediment and indicated that much of the annual load moves as suspended material during short, high-flow flood events. Empirical modeling across 35 sites has further indicated that larger floodplains and wetlands are associated with lower sediment yields, underscoring the regulatory role of floodplains in sediment routing and storage [7,8,9]. Together, these previous studies demonstrate that significant upland erosion occurs in upstream areas during the summer rainy season and the resulting sediment is transported downstream where it is eventually deposited in reservoirs, floodplains, and wetlands as the flood wave propagates. This established role of floodplains underscores the necessity of accurately quantifying their sediment dynamics, which is the focus of this research.

Although sediment transport dynamics in Korean rivers have been relatively well studied, research focusing on floodplain processes remains limited, as most studies have typically employed only hydraulic or hydrodynamic modeling approaches. These models are inherently limited not only because ensuring their accuracy requires calibration and validation using extensive field data that are often limited and challenging to acquire during flood events, but also because they fail to capture exact localized surface changes and vegetation dynamics. Furthermore, such modeling approaches cannot directly measure the actual sediment erosion and deposition in floodplains, resulting in uncertain sediment budget estimates. However, recent technological advances have increased the incorporation of satellite-based remote-sensing data into water- and river-related research. For example, optical satellites, such as Landsat and Sentinel-2, can detect changes in water color and wave reflectance to estimate suspended sediment concentrations, offering wide spatial coverage and high temporal resolution when flood conditions hinder field measurements [10]. Complementing these optical systems, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) satellite sensing, particularly interferometric synthetic aperture radar (InSAR), can detect ground deformation and sediment deposition with millimeter-scale sensitivity [11,12]. In addition to sediment monitoring, InSAR has also been used in river and water management applications to inform flood risk reduction and infrastructure safety efforts. For example, Sentinel-1 data were used in South Korea to flag weak levee sections around the 2020 Seomjin River failure site and create levee indices by coupling displacement variability with hydrometeorological factors such as soil moisture to provide early warning of failure [13]. The application of Sentinel-1 data has also facilitated rapid inundation mapping in South Korean basins when optical data are unavailable, thereby supporting near real-time flood forecasting, monitoring, and awareness [14]. Finally, persistent scatter InSAR mapping of subsidence in reclaimed coastal infrastructure, such as the Busan New Port, has enabled the linking of geotechnical changes with water management planning and shown how long-term drainage capacity and flood exposure along estuarine corridors have been constrained [15]. Although InSAR has been successfully applied in South Korea to monitor infrastructure stability and map flooding and ground subsidence [15,16,17], its use in the direct, quantitative assessment of floodplain sediment deposition remains largely unexplored. Therefore, this study fills the gap between traditional model-based approaches simulating flow and sediment behaviors without directly observing geomorphic change and remote sensing applications of InSAR, focusing primarily on structural and geological deformations by integrating InSAR data and multispectral imagery to demonstrate a new satellite-based methodology that provides detailed and spatially extensive measurements of floodplain sediment transport. This integrated approach can enhance our understanding of flood-driven sediment dynamics, especially in regions with sparse on-site data, and provide insights for managing floodplains and flood risks while preserving floodplain ecosystems.

2. Experimental Analysis and Methods

2.1. Study Site

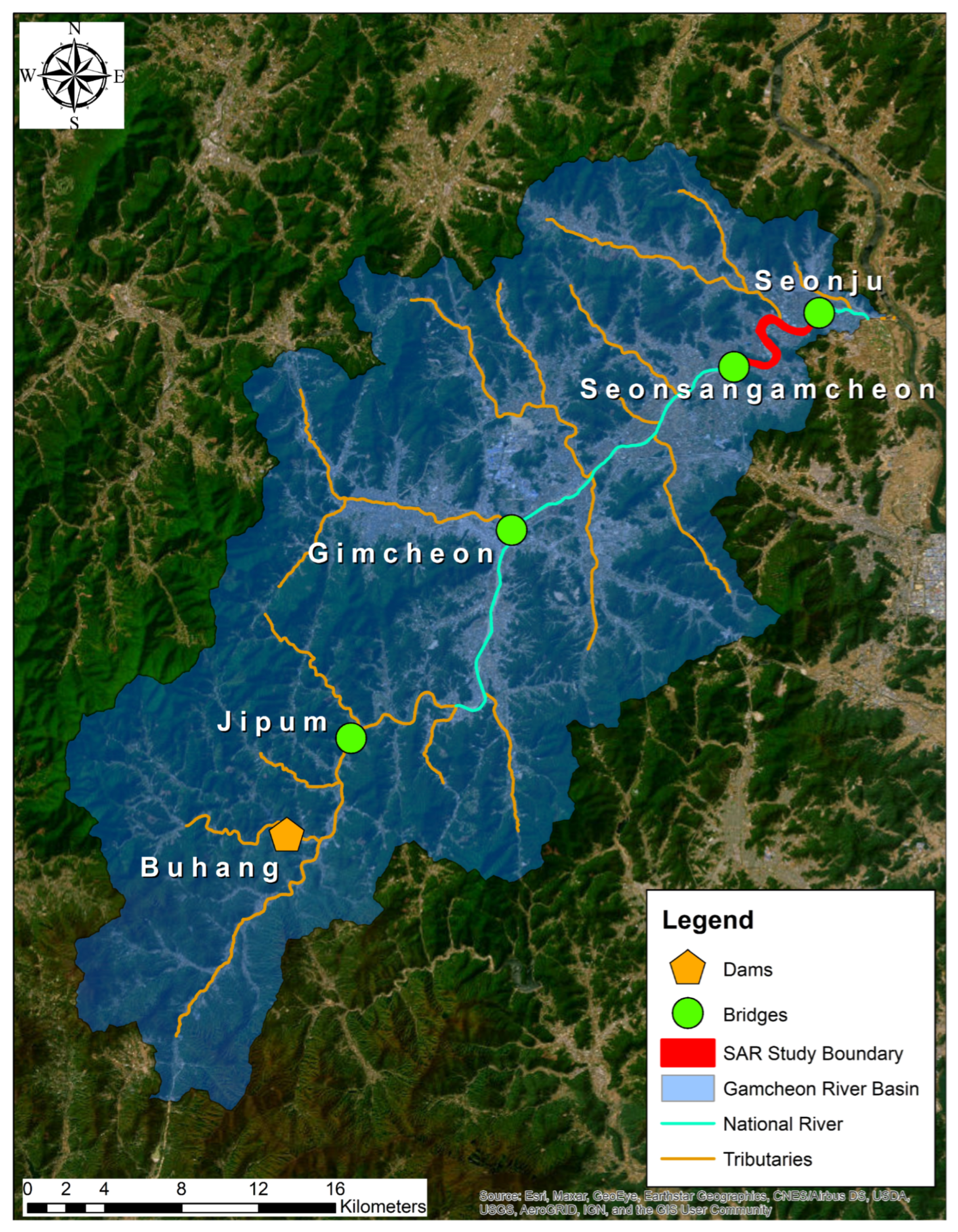

This study analyzed the Gamcheon River, a major tributary of the Nakdong River, which is located in southeastern South Korea. Originating from the northwestern slopes of Mt. Wolmae in Daedeok-myeon, Gimcheon City, the Gamcheon River flows approximately 69 km before merging with the main channel of the Nakdong River. The total drainage area of the river basin is approximately 1004.4 km2, spanning between 127°52′32″ to 128°21′10″ E and 35°50′52″ to 36°18′11″ N. The upper basin is characterized by relatively undisturbed terrain and land cover predominantly consisting of forested hills and agricultural fields (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study site.

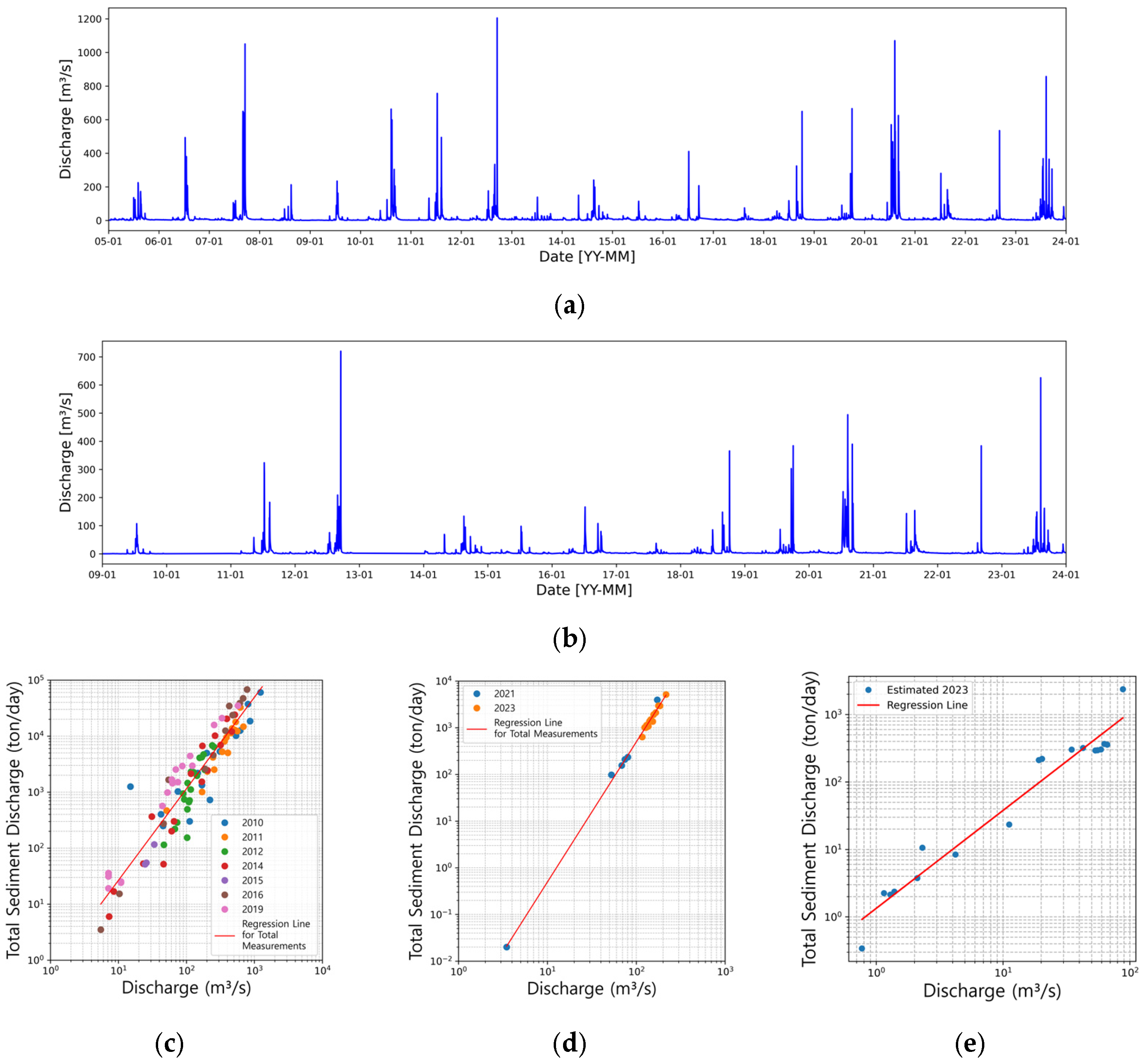

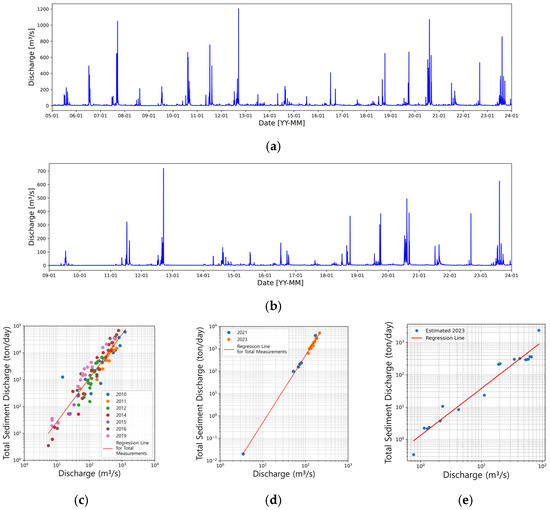

A total of 3428 daily discharge measurements recorded along the main channel of the Gamcheon River were used in this study: 2142 measurements collected at the Seonju Bridge Station from 2005 to 2023 and 1286 measurements collected at the Gimcheon Bridge Station between 2009 and 2023; these data are presented in Figure 2a,b, respectively. Note that the Gamcheon River region is highly susceptible to flooding during typhoon and monsoon events owing to the climatic characteristics of the Korean Peninsula, where heavy rainfall is concentrated during the summer monsoon season, as well as the dense tributary network, short flow paths, and increasing runoff from urban expansion within this watershed [16]. Furthermore, this study employed 101 sediment transport data points collected at the Seonju Bridge in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2019, and 34 measurements recorded at the Gimcheon Bridge in 2021 and 2023, as shown in Figure 2c,d.

Figure 2.

Daily discharges at (a) Seonju Bridge and (b) Gimcheon Bridge. Sediment rating curves at (c) Seonju Bridge, (d) Gimcheon Bridge, and (e) Gimcheon Bridge from estimated results.

Although the amount of sediment supplied to the main channel of the Gamcheon River is relatively low (approximately 120 tons/km2·year) owing to the presence of an upstream dam constructed to provide water supply and downstream flow stabilization, the sediment transport characteristics typical of Korean rivers are still evident, particularly the large volumes transported during the flood season [8,9]. Critically, the Gamcheon River basin has exhibited distinct riverbed morphological changes over the past decade that coincide with the expansion of riparian vegetation. Indeed, dense vegetation communities composed of Salix gracilistyla, Phragmites japonicus, and Typha orientalis have become established along the floodplain and inner channel zones. These plants provide notable ecological benefits, such as bank stabilization and habitat support, but their presence in high densities increases the hydraulic roughness of the river channel, which can reduce flow velocity and elevate water levels during flood events. Furthermore, sediment tends to accumulate in densely vegetated areas owing to flow deceleration, leading to localized riverbed aggradation and forming mid-channel bars [5]. Ultimately, the main channel of the Gamcheon River is characterized by a complex sediment transport regime in which localized erosion and deposition processes coexist owing to varying hydraulic conditions, seasonal flood pulses, and the influences of riparian vegetation and upstream flow regulation.

2.2. Modeling to Select the Study Area

The hydraulic behavior and riverbed changes of the Gamcheon River were simulated in this study by a one-dimensional (1D) steady-state hydraulic model developed using the Hydrologic Engineering Center River Analysis System (HEC-RAS) software, version 6.5. This software, developed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, is widely used to simulate open-channel hydraulics under various flow conditions. Critically, it supports analyses of water surface profiles as well as sediment transport, erosion, and deposition processes. Therefore, this study employed a 1D HEC-RAS model configured in quasi-unsteady flow mode to evaluate the longitudinal flow dynamics and sediment conveyance along the main channel of the Gamcheon River. Notably, this 1D approach offers computational efficiency and robustness when analyzing profile changes across the entire study reach.

The geometric framework for the HEC-RAS model was established using longitudinal and cross-sectional survey data from the 2016 “Master Plan for the Mid-to-Lower Gamcheon Basin”, supplemented with updated terrain data from the river information management geographic information system (GIS). These datasets informed a detailed representation of the river channel and its adjacent floodplain topography. The boundary conditions for the upstream flow were defined using discharge records from Jipumgyo station, and the downstream water levels were based on observations collected at Seonjugyo station. The sediment input parameters, including grain size distribution and bed composition, were derived from field surveys conducted at the Gimcheongyo cross-section and integrated into the model for sediment transport analysis. The flow boundary conditions were configured according to the design flood frequencies specified in the 2016 master plan [7]. Hydrographs representing the design discharge events were applied at the upstream boundary of the model, and a constant stage was assigned at the downstream boundary, which was constrained using the water levels observed at Seonju Bridge. Manning’s roughness coefficients ranging from 0.024 to 0.033 were applied to reflect the channel bed conditions, vegetation cover, and levee structure according to the River Design Criteria and Guidelines based on field observations and adjusted to match the hydraulic and morphological characteristics of the Gamcheon mainstem [16]. Sediment boundary conditions were established for the upstream reach (e.g., above Jipum Bridge) to analyze the erosion and deposition zones along the main channel of the Gamcheon River and support SAR-based terrain change detection (Figure 2e) using the model tree-based sediment estimation technique proposed by Jang et al. [17]. This method considers hydrological and morphological input variables, such as discharge, flow velocity, water depth, and bed material grain size, and was trained to predict daily sediment discharge at the upstream site based on data collected at previously monitored locations. The estimated sediment load was subsequently used as the upstream boundary condition to simulate riverbed changes in the 1D HEC-RAS sediment transport model.

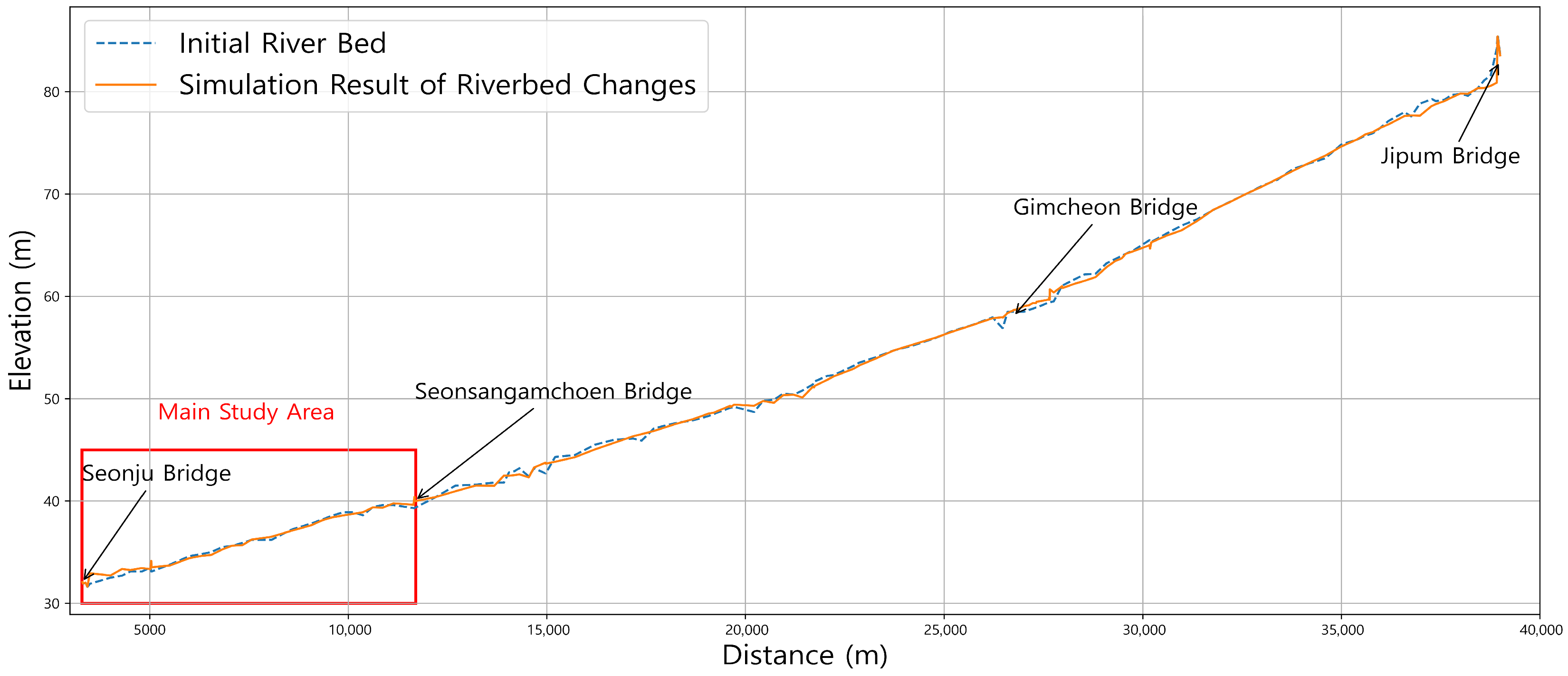

The HEC-RAS simulation results obtained using the estimated sediment load were compared with those obtained using the data measured at the Gimcheon Bridge to verify the accuracy of the simulation method. Although different riverbed changes were observed in the upstream section depending on the sediment input method, similar results were obtained in the downstream section, confirming that the proposed sediment estimation technique is reliable and can be effectively applied to simulate riverbed changes. The simulation results indicated that the upstream section between the Seonsangamcheon and Seonju bridges exhibited predominant erosion, whereas the downstream section experienced significant sediment deposition (Figure 3). These model-obtained patterns are consistent with the DInSAR displacement observations, which indicated only surface lowering across the floodplain (i.e., no positive uplift) in non-flood conditions, as well as modest upstream erosion and significant downstream deposition during flood events. In particular, the DInSAR analysis showed depositions of approximately 0.31 and 0.33 m in the lower part of the study area for short flood and long flood scenarios, respectively. These depositions were spatially coincident with the downstream reach in the HEC-RAS model, which indicated a maximum sediment deposition of 0.66 m between Gampogyo and the Seonsangamcheon Bridge. Furthermore, the modeled erosional zone mirrored the small upstream lowering observed by DInSAR. These results strengthened confidence in the accuracy of the erosion and deposition patterns obtained by both approaches. Therefore, the downstream section between the Seonsangamcheon and Seonju bridges was selected for the SAR-based floodplain deformation analysis in this study because it represents a typical area influenced by multiple interacting riverine factors, including vegetation expansion, repeated flood damage, and aging levee structures and exhibits a considerable bed-level difference compared with the main channel of the Nakdong River, into which this segment flows.

Figure 3.

Riverbed change simulation results obtained using HEC-RAS showing the main study area.

2.3. Study Data and Methods

This study employed C-band SAR data collected by the Sentinel-1B satellite operating in the interferometric wide-swath mode, which provides a spatial resolution of 5 m (range) by 20 m (azimuth) and collects data through a descending orbit with a revisit period of 6–12 d. Five Sentinel-1 images were processed covering a non-flood baseline scenario occurring between 9 May and 2 June 2020. The impacts of different flood conditions were assessed using two additional scenarios. The first scenario comprised a short 3 d flood event that occurred 13–15 July 2020; it was captured between the Sentinel-1 acquisitions of 26 June and 20 July 2020. This flood was characterized by a rapid, single-peak hydrograph reaching a maximum discharge of 570 m3/s. The second scenario comprised a prolonged 16 d long flood event that occurred in two phases from 23 July to 1 August and 7 to 13 August 2020; it was captured between the image acquisition windows of 20 0July and 24 August 2020. This flood was characterized by a long, elevated hydrograph reaching a maximum discharge of 1069 m3/s (Table 1). The consideration of a short, rapid flash flood event along with a sustained, high-volume flood event captured the cumulative effects of repeated inundation on the floodplain and enabled a comparison of how different flood dynamics influence patterns of floodplain sediment displacement. The satellite imagery data were sourced from the Copernicus Browser website and processed using the SNAP software package (version 11.0.0) with GIS tools to visualize and quantify the analysis results.

Table 1.

SAR data description.

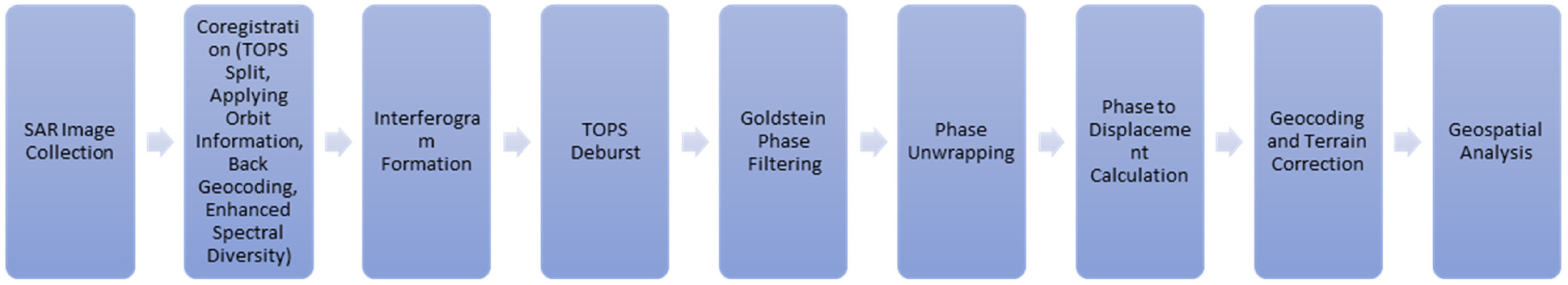

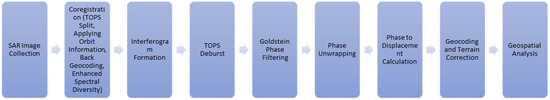

This study applied the DInSAR technique to detect and analyze riverbed sediment displacement caused by flood deposition. This technique enables the detection of subtle ground surface movements by comparing the phase differences between two radar images captured at different times. It is particularly useful for identifying short-term deformations, especially during flood events, as it requires only two SAR images per observation window. This analysis followed the general DInSAR processing workflow shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

DInSAR deformation analysis flowchart.

The calculation of ground surface displacement began with the generation of an interferogram by capturing the phase differences between InSAR images of the same area collected at different times. These phase differences were subsequently encoded with the changes in the distance between the satellite sensor and Earth’s surface. Next, the line-of-sight displacement (d) was calculated from the unwrapped phase () as follows:

where α denotes the radar wavelength and θ denotes the local incidence angle between the radar line-of-sight and vertical.

The data for the three considered scenarios (non-flood, short flood, and long flood) were compared to evaluate the effects of flooding on DInSAR coherence and isolate the sediment displacement by focusing on the segment of the Gamcheon River between the Seonsangamcheon and Seonju bridges. Data reliability was ensured and an accurate DInSAR deformation analysis was realized by applying a coherence threshold to exclude pixels exhibiting a low phase stability; all pixels with a coherence below 0.6 were removed as this was assumed to indicate significant decorrelation and unreliable phase information [11,18,19]. Indeed, low-coherence signals are often generated by temporal decorrelation due to surface changes or volume scattering effects, such as vegetative cover and soil moisture [20,21]. By filtering out these unstable pixels, only coherent pixels were retained for deformation analysis.

Furthermore, the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and index of soil surface moisture (ISSM) were calculated to assist in the selection of pixels representing bare riverbed surfaces, which were considered the optimal subject for analysis in this study. The NDVI and ISSM were, respectively, computed as follows [22]:

where NIR denotes the reflectance in the near-infrared band, Red denotes the reflectance in the red band, denotes radar backscatter coefficient in vertical–vertical polarization, and and denote the minimum and maximum values across the dataset, respectively.

The representative NDVI and ISSM values for each pixel in each image were analyzed using the methodology presented in [20,23], and pixels indicating bare soil (0 < NDVI < 0.1) and low- to no-moisture conditions (ISSM < 0.2) were identified as bare riverbed surfaces based on the guidance in [24,25,26] using Geographic Information System (GIS) software; the results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and index of soil surface moisture (ISSM) classification table.

3. Results

3.1. Coherence Filtering for SAR Analysis

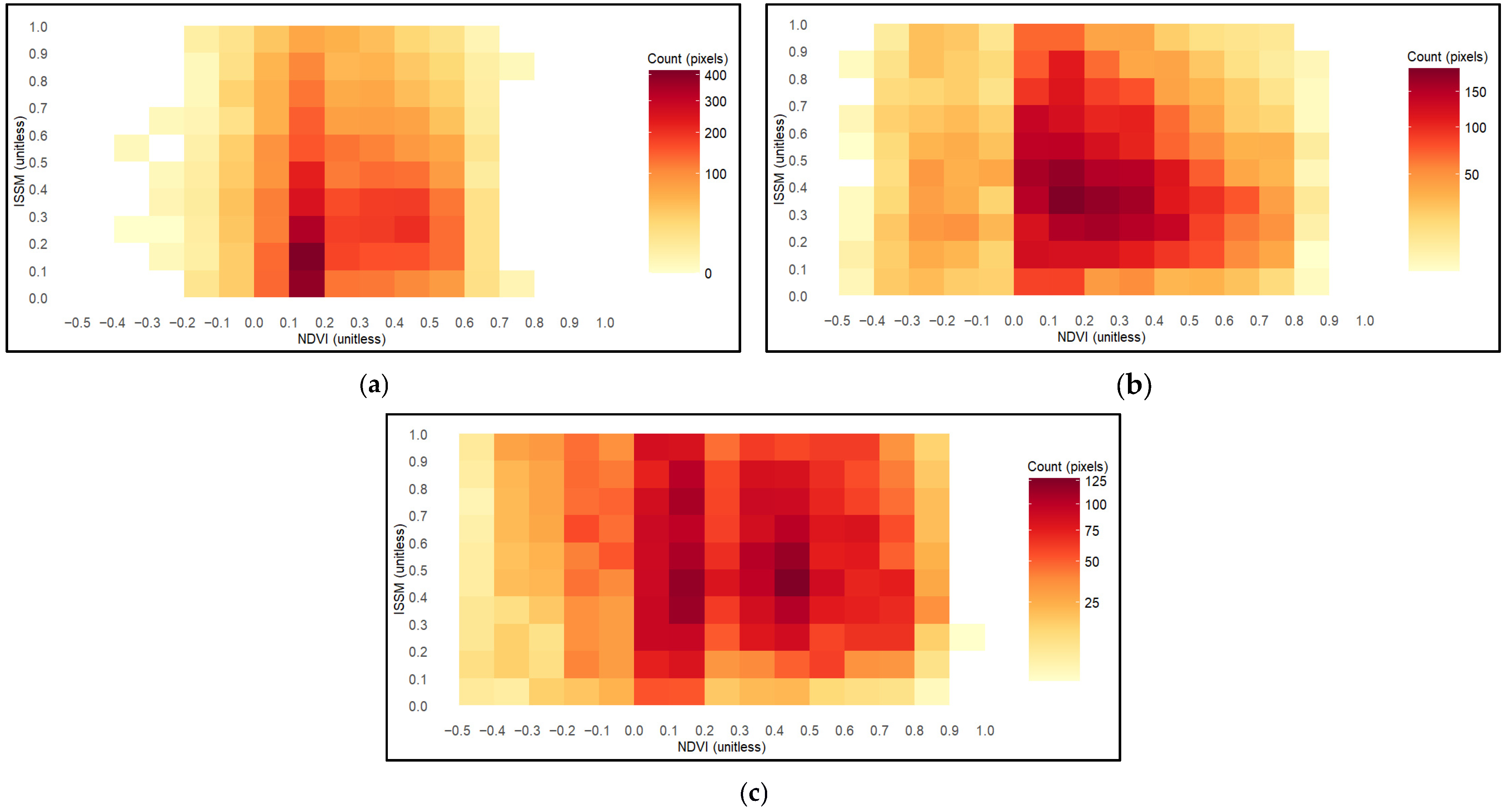

The NDVI vs. ISSM density plots for the three considered scenarios, shown in Figure 5, reveal that the pixels removed by the coherence filter were predominantly located in areas with vegetation and moist soil. Across all three scenarios, most low-coherence pixels had NDVI values above 0.1, indicating low-to-dense vegetation, and ISSM values above 0.2, indicating moist-to-saturated soil conditions. These regions of vegetation and moist soils correspond to known causes of interferometric decorrelation. Notably, the density plots obtained under the two flood scenarios contained larger shares of pixels with high ISSM and NDVI values than the density plot obtained under the non-flood scenario because floods increase surface wetness and create conditions that favor riparian and vegetation growth during wet months, as the moisture and nutrient deposition accompanying flood pulses promote plant establishment and productivity [27].

Figure 5.

NDVI vs. ISSM classification (coherence < 0.6) density plots for the: (a) non-flood, (b) short flood, and (c) long flood scenarios.

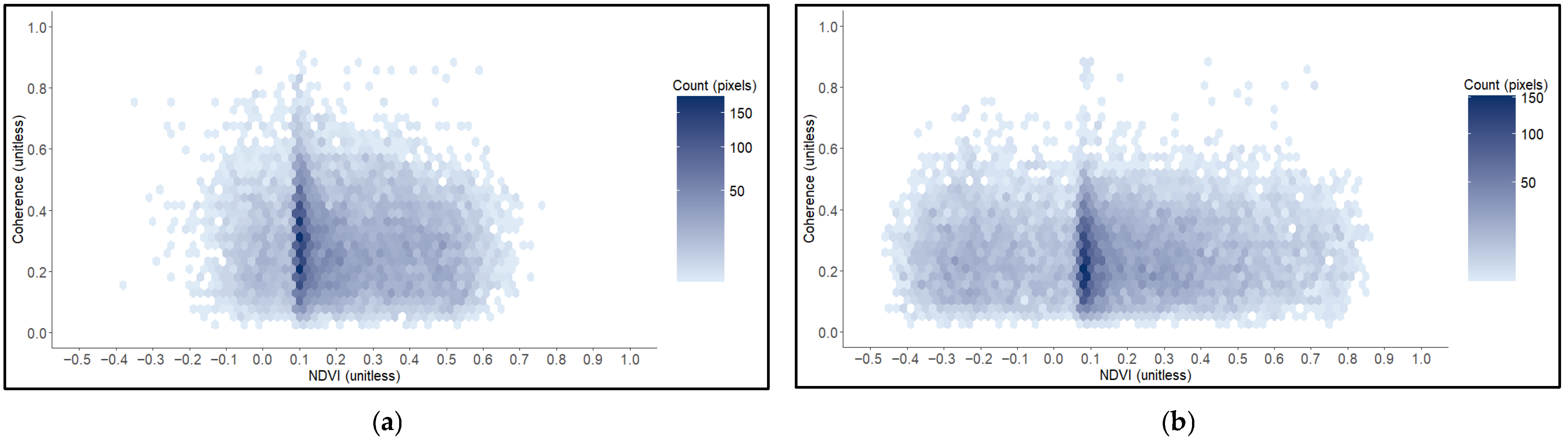

The effects of vegetation on SAR coherence were assessed using the density plots in Figure 6, which show the association between NDVI and coherence across the three considered scenarios. The results indicate that 77.24%, 55.12%, and 64.97% of pixels in the non-flood, short flood, and long flood scenarios, respectively, had NDVI values exceeding 0.1 and coherence values below 0.6. These values confirm that the presence of vegetation is a persistent driver of decorrelation across all scenarios, though its relative contribution is lower during flood events, likely owing to the concurrent influence of surface moisture. This pattern is consistent with the fluvial setting in South Korea, where many monsoon-driven rivers have transitioned from bare sand-dominated channels to vegetation-rich channels. Indeed, monitoring of Korean sand-bed systems has observed the rapid expansion of herbaceous and woody vegetation in floodplains, narrowing of low-flow channels, formation of secondary channels, and an increase in hydraulic roughness modulating flood routing and sediment trapping. Such biogeomorphic alterations reflect the sustained presence of vegetation followed by bank stabilization promoting additional sediment retention, a process that is now common in modified monsoonal rivers in Korea [28].

Figure 6.

NDVI vs. coherence density plots for the (a) non-flood, (b) short flood, and (c) long flood scenarios.

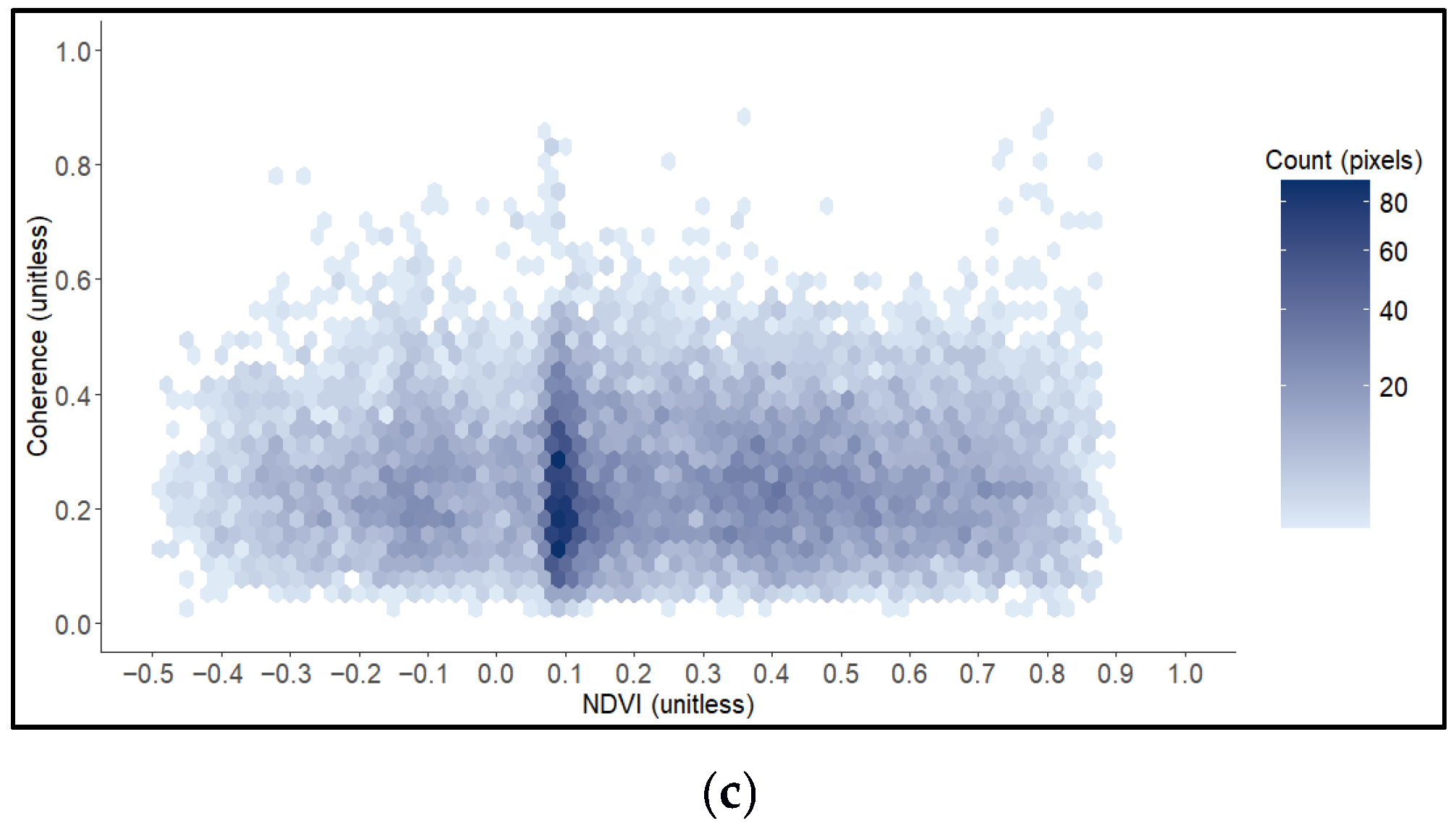

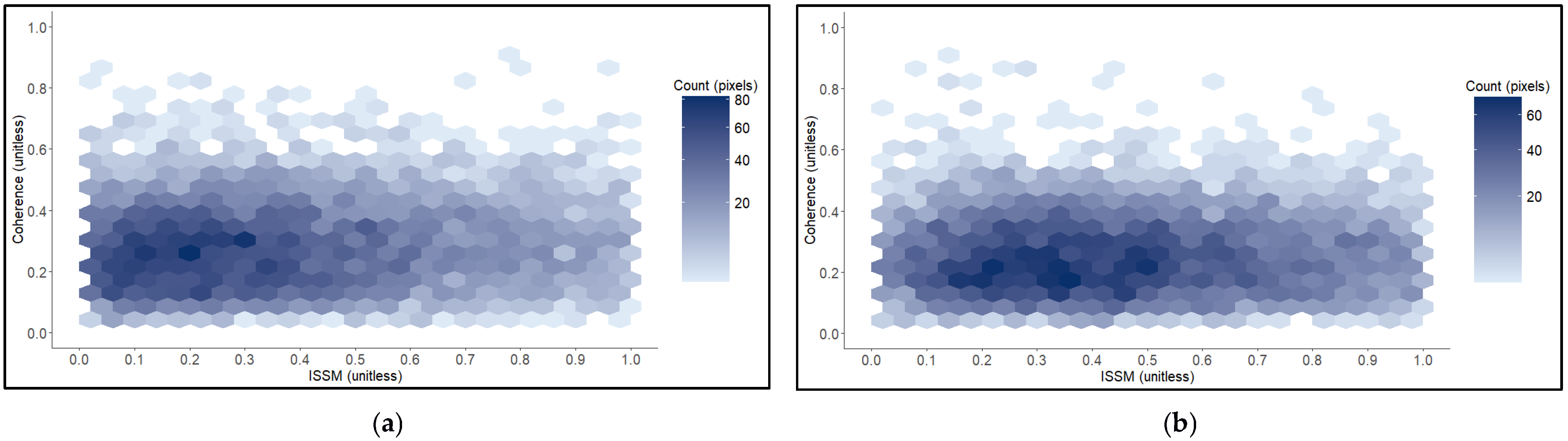

The impact of soil moisture on coherence loss is similarly clear in Figure 7. Across all scenarios, low-coherence pixels were concentrated at higher ISSM values. In flooded zones, coherence loss was typically observed where ISSM values indicated wet or saturated soil conditions (ISSM > 0.2). Quantitatively, 58.08%, 67.24%, and 78.76% of low-coherence pixels in the non-flood, short flood, and long flood scenarios, respectively, exhibited ISSM values greater than 0.2. The long flood scenario clearly exhibited the wettest and most saturated decorrelation pattern with widespread and prolonged saturation following the 16 d flood event, explaining the loss of reliable pixels. By comparison, the short flood scenario retained a higher proportion of coherent pixels, whereas the dry non-flood scenario still exhibited some moisture-driven coherence loss in certain areas. Moreover, the average ISSM for each scenario exhibited the same trend with values of 0.184, 0.236, and 0.311 for the non-flood, short flood, and long flood scenarios, respectively, confirming that the two flood scenarios were generally wetter than the non-flood scenario.

Figure 7.

ISSM vs. coherence density plots for the (a) non-flood, (b) short flood, and (c) long flood scenarios.

Considering the NDVI results in Figure 6 with the ISSM results in Figure 7, the density plots and filtering outcomes conclusively demonstrate that vegetation and soil moisture are dominant controls of coherence in the floodplain. Vegetated areas (NDVI > 0.1) and moist or saturated soils (ISSM > 0.2) not only accounted for the majority of the pixels across all three scenarios but also explained the most significant losses in usable pixels. The long flood scenario exhibited the greatest reduction in coherent pixels (a direct outcome of widespread soil saturation and overlapping vegetative cover), whereas bare and dry surfaces exhibited high coherence and remained the only reliable pixels for DInSAR analysis.

3.2. Floodplain Displacement Analysis Results

Despite limited spatial coverage, the DInSAR displacement results revealed clear patterns of sediment erosion and deposition corresponding to the considered flood events. In the non-flood scenario, the displacement map in Figure 8a shows only negative displacement values (surface lowering owing to erosion) of up to –2.03 m throughout the floodplain and no positive displacement values (surface uplift owing to deposition). This finding supports the understanding that in the absence of significant flood events, sediment is removed from exposed surfaces rather than being deposited in the floodplain.

Figure 8.

Sediment displacement maps for the (a) non-flood, (b) short flood, and (c) long flood scenarios.

By contrast, the DInSAR results for both flood scenarios indicated a combination of negative and positive displacement values. As shown in the displacement maps in Figure 8b,c, slight erosion occurred in the upper region of the study area and significant sediment accumulation occurred in the lower region of the floodplain. In the short flood scenario, the erosion and deposition values were approximately –0.02 m and +0.31 m, respectively. The long flood scenario yielded slightly more pronounced changes with –0.002 m of erosion and +0.33 m of deposition. These variations suggest that flood duration influences the magnitude of sediment transport and that floodwaters erode material from elevated upstream regions to deposit it downstream, where the channel slope and energy decline. Notably, this pattern of upstream erosion and downstream deposition aligns well with the 1D hydraulic modeling results presented in Section 2.2, which identified erosion in the upper region of the river and significant sediment deposition in the lower region of the floodplain. This agreement between the DInSAR-derived changes and HEC-RAS model predictions reinforces the credibility of both approaches in capturing the response of the Gamcheon River to flooding. Overall, these findings confirm the potential value of using DInSAR to detect and quantify flood-induced sediment transport in floodplains.

4. Discussion

Vegetation cover, which was expressed in terms of NDVI in this study, is related to floodplain sediment deposition and, as such, exhibited distinct patterns across the different flood scenarios considered. After waterlogged pixels were removed, the long flood scenario exhibited the highest average NDVI (0.345), followed by the short flood (0.256) and non-flood (0.242) scenarios. Figure 9 shows a spatial representation of these vegetation patterns across the floodplain. Although water pixel coverage was greater in both the short and long flood scenarios than in the non-flood scenario, the vegetation was densest in the long flood scenario. This result aligns with previous studies stating that denser canopies increase hydraulic roughness, reduce flow velocity, and enhance the settlement and trapping of suspended sediments [29,30]; prolonged inundation amplifies this effect by extending the window for fine particles to settle. Thus, the lower NDVI values in the non-flood scenario are consistent with the reduced trapping capacity and comparatively lower floodplain deposition (Figure 8) expected in this scenario, suggesting that a certain canopy density and continuity must be exceeded before vegetation substantially modifies sedimentation dynamics.

Figure 9.

NDVI maps for the (a) non-flood, (b) short flood, and (c) long flood scenarios.

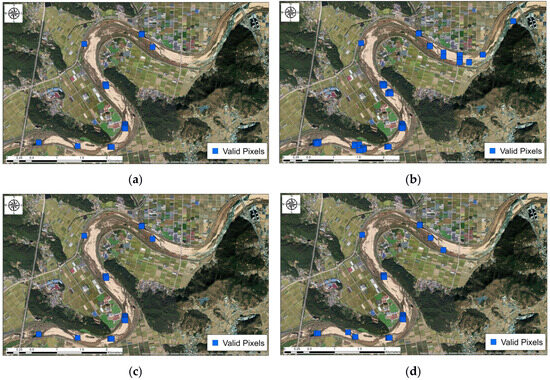

The effects of the vegetation and surface moisture thresholds on the number and spatial patterns of the valid pixels identified using the proposed method were evaluated by conducting a sensitivity analysis using 48 combinations of NDVI thresholds (≤0.05, 0.10, 0.15, and 0.20) spanning from bare soil to lightly vegetated conditions and ISSM thresholds (≤0.15, 0.20, 0.25, and 0.30) spanning from dry to moderately moist surfaces. Each combination was evaluated under the non-flood, short flood, and long flood scenarios using a coherence filter of ≥0.6.

The threshold sensitivity analysis indicated a consistent pattern of diminishing returns in valid pixel gains with increasing threshold values across all scenarios. For the NDVI-only threshold, the largest marginal gain in valid pixels occurred between 0.05 and 0.10, broadening coverage within the bare soil areas where coherence was high and uniform. Increases beyond 0.10 added progressively fewer pixels because the newly admitted surfaces were increasingly vegetated, which introduced volume scattering and temporal variability that reduced coherence. The trend for the ISSM-only threshold was similar but more gradual, with the largest change occurring between 0.15 and 0.20 as dry to slightly moist pixels that remained coherent were admitted. Further relaxations to 0.25 and 0.30 added fewer pixels as wetter areas remained decorrelated. For the combined NDVI and ISSM cases, the most prominent gain in valid pixels occurred when the NDVI threshold increased from 0.05 to 0.10 in the non-flood scenario (163–197%), followed by the short flood scenario (69–94%), then the long flood scenario (13–33%). This pattern was observed because the non-flood scenario retained extensive bare and dry surfaces that immediately qualified once the NDVI threshold was raised to 0.10, whereas the two flood scenarios added moisture-driven decorrelation that limited the pool of coherent bare pixels. By contrast, an increase in the ISSM threshold from 0.15 to 0.20 yielded smaller percentage increases in valid pixels, ranging from 4% to 7% for the non-flood scenario, 6% to 14% for the short flood scenario, and 14% to 22% for the long flood scenario. This gradient reflects the growing influence of surface moisture owing to flooding, which clustered many pixels near the 0.20 ISSM threshold. Overall, the validity of pixels was determined to be more driven by NDVI than ISSM, particularly under dry conditions, though the ISSM grew increasingly influential during floods.

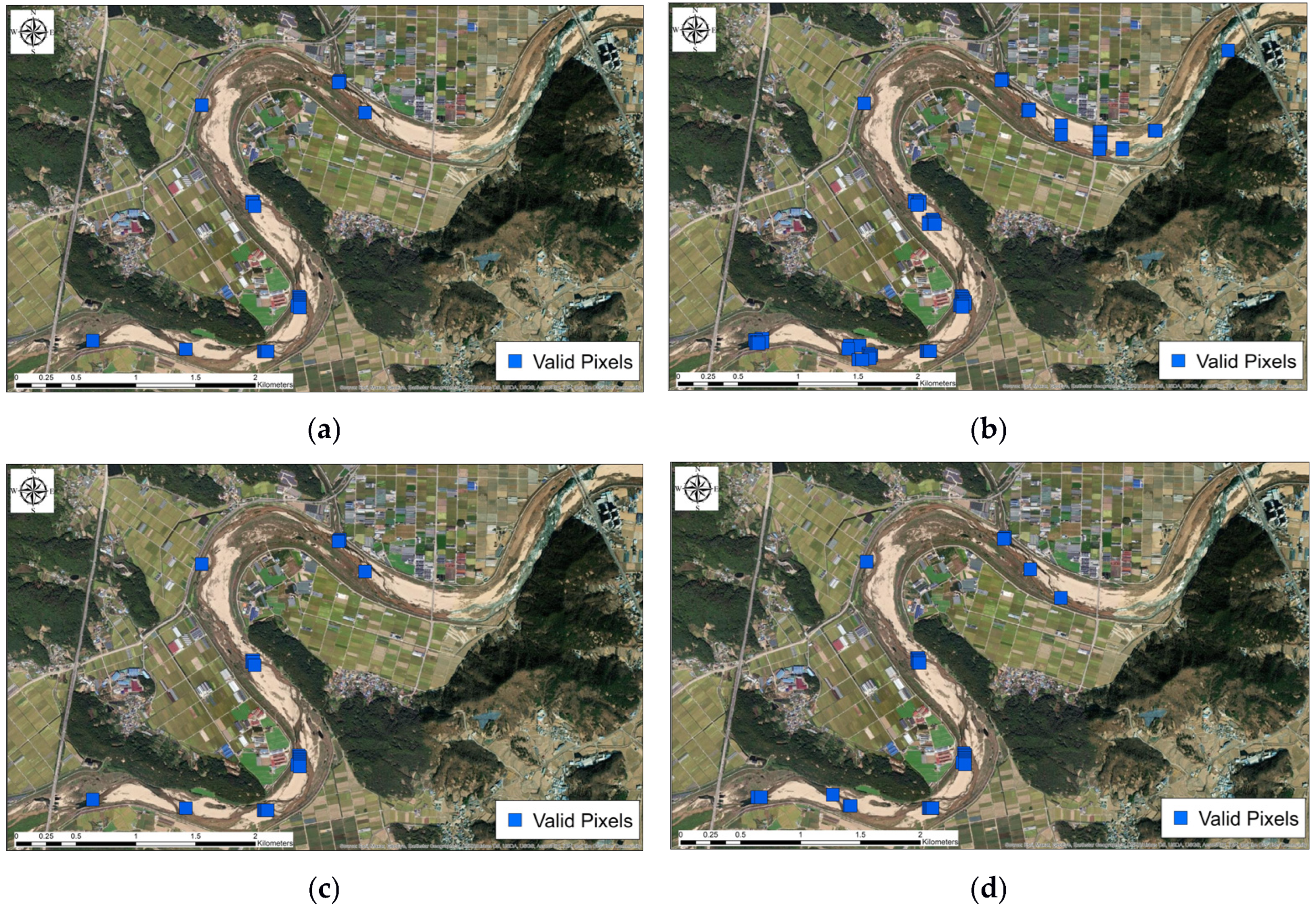

These statistical trends are visually illustrated by the spatial distributions of valid pixel masks for key threshold comparisons in Figure 10. The comparison in Figure 10a,b, which holds moisture constant (ISSM ≤ 0.20) while relaxing the NDVI threshold from 0.05 to 0.10, clearly demonstrates the dominant effect of vegetation. This single adjustment produced the largest percentage increase observed in the analysis (a 197% gain in valid pixels in the non-flood scenario) by incorporating the high-coherence bare soil surface characteristics typical of this scenario. By contrast, isolating the more subtle influence of surface moisture by relaxing the ISSM threshold yielded a considerably smaller gain, as shown in Figure 10c,d, wherein the largest ISSM-driven increase was only 24%, also in the non-flood scenario. This difference quantitatively demonstrates that the selection of valid pixels is more driven by NDVI than ISSM. In spatial terms, relaxing either threshold expands the valid data area, expanding coverage and extending it further downstream.

Figure 10.

Valid pixel threshold maps for (a) NDVI ≤ 0.05 and ISSM ≤ 0.20, (b) NDVI ≤ 0.1 and ISSM ≤ 0.20, (c) NDVI ≤ 0.05 and ISSM ≤ 0.25, and (d) NDVI ≤ 0.05 and ISSM ≤ 0.30.

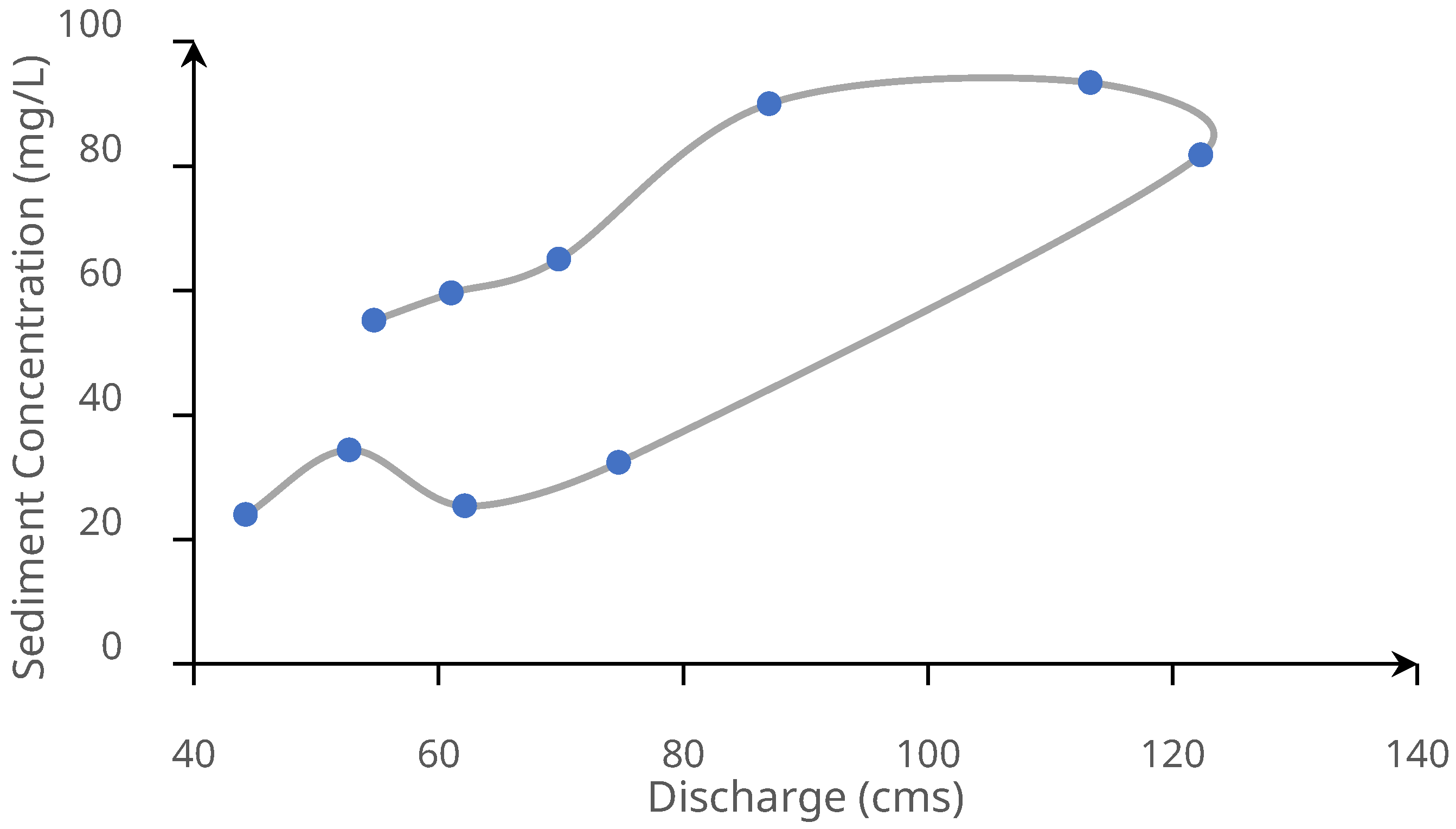

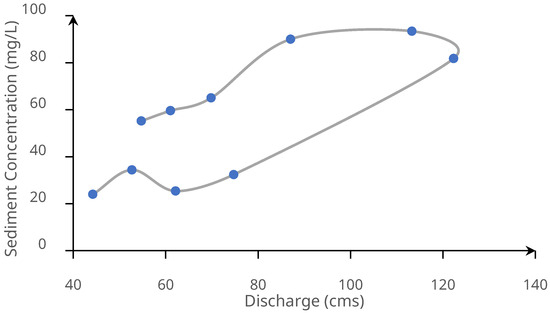

The sediment transport behavior was also examined using a hysteresis analysis to evaluate the dynamic relationship between water discharge and sediment load. A clockwise hysteresis loop was observed when the total suspended sediment load was plotted against discharge at Seonju Bridge in July 2019, as shown in Figure 11. A clockwise loop in which the suspended sediment load peak precedes the water discharge peak indicates that readily available sediment from nearby sources is quickly mobilized during the rising limb of the hydrograph. This pattern is often a sign that erosion is the primary driver of sediment mobilization in the initial stages of a flood event. Conversely, a counterclockwise hysteresis loop, in which the suspended sediment load peak occurs after the water discharge peak, indicates a delayed sediment response [31]. This delay can be caused by the presence of sediment sources far from the river channel, such as distant tributaries or hillslopes, or by mechanisms such as riverbank collapse, which occurs as water levels recede and pore water pressure decreases [30]. In the case of the Gamcheon River, the clockwise loop observed at Seonju Bridge strongly indicates the influence of upstream hydraulic regulation by the Buhang Dam. Indeed, the presence of dam- or weir-like structures can significantly alter the natural sediment regime by trapping sediment from the upper areas of the watershed, starving the downstream riverbed of sediment in a condition known to cause clockwise hysteresis. This interpretation is consistent with the DInSAR-derived analysis of erosion in the upper segment of the study area, which acted as a nearby source of early sediment load [32]. However, the limited supply of nearby sediment was rapidly entrained and exhausted as the discharge increased, leading to the observed differences between the short and long flood scenarios.

Figure 11.

Hysteresis curve at Seonju Bridge.

Historical sediment data support these findings: the 101 sediment transport measurements collected at Seonju Bridge (2010–2019) and 34 measurements collected at Gimcheon Bridge (2021–2023) suggest that although the annual supply of sediment to the main channel is relatively low (approx. 120 tons/km2·yr) owing to upstream dams, flood-induced transport still occurs in pulses during monsoon season. Furthermore, recent vegetation expansion has clearly altered the floodplain hydraulics by increasing flow resistance and enhancing deposition in vegetated zones, particularly under the prolonged inundation observed during long flood events.

Notably, the ability of SAR to penetrate cloud cover can augment the capabilities of optical remote sensing during heavy rainfall seasons to ensure continuous monitoring. Furthermore, the addition of spatial information from DInSAR to hydraulic modeling simulations employing on-site measurements, such as hysteresis curves, provides a more holistic assessment of flood-induced sediment transport. The findings of this study suggest two potential practical applications of the proposed DInSAR-based surface deformation analysis method. First, DInSAR-derived erosion and deposition maps can be used to identify bank instability hotspots near critical infrastructure, such as flood walls, levees, and outfalls, informing targeted monitoring and reinforcement plans. Second, the observed link between vegetation density and sediment trapping can directly guide the design of ecological restoration projects, informing the strategic planting of vegetation to promote floodplain aggradation for habitat creation and targeted clearing of vegetation in areas where maintaining flood conveyance capacity is a priority.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the flood-induced sediment dynamics in the Gamcheon River basin by integrating 1D HEC-RAS modeling and DInSAR data analysis of non-flood baseline, 3 d short flood, and 16 d long flood scenarios. The study domain, which stretched from the Seonsangamcheon Bridge to the Seonju Bridge, was selected because of the expanding riparian vegetation and morphological changes observed in this area in recent years. By combining satellite-based deformation measurements with vegetation (NDVI) and soil moisture (ISSM) indices and corroborating the obtained values with field observations and modeling outputs, this study provides a comprehensive view of the biogeomorphic response of the evaluated floodplain to floods of varying magnitudes and durations.

The DInSAR-based deformation analysis revealed that the floodplain experienced net erosion in the absence of flooding, with a maximum surface lowering of –2.03 m. By contrast, the short flood scenario produced minor upstream erosion (–0.02 m) and downstream deposition (+0.31 m), whereas the long flood scenario yielded the most significant deposition (+0.33 m), also in the downstream reaches. These spatial patterns of erosion and deposition matched the results obtained using the HEC-RAS model. Additionally, a hysteresis analysis of total suspended sediment data collected at the Seonju Bridge (for a July 2019 flood event) exhibited a clockwise loop, indicating early-stage sediment mobilization, likely from nearby stream banks and exposed floodplain zones. This pattern aligns with the SAR-derived deformation trends and confirms that localized erosion dominates the initial sediment response in this regulated river system. Finally, the growth of vegetation clearly influenced the pattern of sediment deposition, particularly in the long flood scenario.

Despite the promising integration of satellite and hydraulic data in this study, the decorrelation of SAR signals in vegetated and moisture-rich zones represents a key limitation of the proposed analysis method. Regions with NDVI values greater than 0.1 and ISSM values greater than 0.2 were consistently associated with coherence loss, restricting the usable pixels to those representing primarily bare and dry soil areas. Consequently, large-scale erosion or deposition within vegetation-obscured areas cannot be dismissed, and the spatial patterns observed in this study should be regarded as the lower bound of basin-wide changes. Furthermore, this study did not incorporate corrections for atmospheric delays or flood-induced hydrological artifacts in the interferograms, which can introduce additional noise in the deformation fields. These limitations suggest that future work should attempt to incorporate atmospheric phase screen methods for tropospheric correction, such as global navigation satellite system-assisted or Generic Atmospheric Correction Online Service models, employ L-band SAR to improve vegetation penetration, and conduct time-series analyses across multiple flood events to capture seasonal variability. Overall, this study demonstrated the value of combining hydraulic modeling with satellite-based remote sensing and field sediment data to monitor floodplain sediment transport and morphodynamic responses. The proposed framework is especially valuable for flood-prone, data-scarce basins, such as that of the Gamcheon River, and offers meaningful implications for sediment management, riparian restoration, and adaptive flood risk planning in similar monsoon-affected river systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.K.; formal analysis, J.E.F. and E.J.; writing, J.E.F.; review and editing, W.K. and S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute through the Climate Change Research Program funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (RS-2024-00397970), the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education (2021R1C1C101040411).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the research grant of Kongju National University in 2025. This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the Jeollanamdo RISE center, funded by the Ministry of Education and the Jeollanamdo, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-14-007).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Julien, P.Y. River Mechanics, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Benjankar, R.; Yager, E.M. The impact of different sediment concentrations and sediment transport formulas on the simulated floodplain processes. J. Hydrol. 2012, 450, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, A.P.; Walling, D.E. Numerical modelling of floodplain hydraulics and suspended sediment transport and deposition. Hydrol. Process 1998, 12, 1339–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büttner, O.; Otte-Witte, K.; Krüger, F.; Meon, G.; Rode, M. Numerical modelling of floodplain hydraulics and suspended sediment transport and deposition at the event scale in the middle river Elbe, Germany. Acta Hydrochim. Hydrobiol. 2006, 34, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.; Kang, W. Estimating riparian vegetation volume in the river by 3D point cloud from UAV imagery and alpha shape. Appl. Sci. 2023, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, R.J.; Bates, P.D.; Anderson, M.G. Modelling suspended sediment deposition on a fluvial floodplain using a two-dimensional dynamic finite element model. J. Hydrol. 2000, 229, 202–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Woo, H. Sediment problems in Korea. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2000, 126, 486–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.Y.; Kang, W.; Lee, J.H.; Julien, P.Y. Sediment regimes in South Korea. River Res. Appl. 2022, 38, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Jang, E.K.; Yang, C.Y.; Julien, P.Y. Geospatial analysis and model development for specific degradation in South Korea using model tree data mining. CATENA 2021, 200, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsen, A.; Kovács, F.; Kiss, T. Remote sensing of sediment discharge in rivers using Sentinel-2 images and machine-learning algorithms. Hydrology 2022, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Mills, J. A new approach to selecting coherent pixels for ground-based SAR deformation monitoring. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 144, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sinclair, H.D. Sediment Aggradation Rates for Himalayan Rivers Revealed Through SAR Remote Sensing. EGUsphere 2024. preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Bang, Y.J.; Jung, H.J.; Lee, S.O. Detection of levee displacement and estimation of vulnerability of levee using remote sensing. J. Korean Soc. Disaster Secur. 2021, 14, 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Lee, Y.; Park, S.-E. On flood detection using dual-polarimetric SAR observation. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez, R.A.; Kwon, T.H. Sentinel-1 persistent scatterer interferometric synthetic aperture radar (PS-InSAR) for long-term remote monitoring of ground subsidence: A case study of a port in Busan, South Korea. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2022, 26, 4317–4329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, E.; Kang, W. One-dimensional bed change prediction using sediment discharge estimation under ungauged boundary conditions. Ecol. Resil. Infrastruct. 2024, 11, 203–210. (In Korean) [Google Scholar]

- Jang, E.K.; Ji, U.; Yeo, W. Estimation of sediment discharge using a tree-based model. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2023, 68, 1513–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, S.H.C.L.; Rosen, P. Application of the interferometric correlation coefficient for measurement of surface change. In Proceedings of the American Geophysical Union Fall Meeting, San Francisco, CA, USA, 5–9 December 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Falabella, F.; Serio, C.; Zeni, G.; Pepe, A. On the use of weighted least-squares approaches for differential interferometric SAR analyses: The weighted adaptive variable-length (WAVE) technique. Sensors 2020, 20, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berca, M.; Horoias, R. NDMI use in recognition of water stress issues, related to winter wheat yields in southern Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2022, 22, 105–111. [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy, S.; Shanmugam, R.S. Multispectral and microwave remote sensing models to survey soil moisture and salinity. Land Degrad. Dev. 2017, 28, 1412–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nativel, S.; Ayari, E.; Rodriguez-Fernandez, N.; Baghdadi, N.; Madelon, R.; Albergel, C.; Zribi, M. Hybrid Methodology Using Sentinel-1/Sentinel-2 for Soil Moisture Estimation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourenço, R.W.; Landim, P.M.B. Estudo da variabilidade do “Índice de Vegetação por Diferença Normalizada/NDVI” utilizando krigagem indicativa. Holos Environ. 2004, 4, 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Archontoulis, S.; Licht, M.; Castellano, M.; FACTS Soil Moisture Benchmarking Tool. Iowa State University Extension and Outreach. Available online: https://crops.extension.iastate.edu/post/facts-soil-moisture-benchmarking-tool (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- UCAR Climate Data Guide. NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index, NOAA AVHRR). Available online: https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/ndvi-normalized-difference-vegetation-index-noaa-avhrr (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Sentinel Hub. NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index)—Sentinel-2 Custom Script. Available online: https://custom-scripts.sentinel-hub.com/custom-scripts/sentinel-2/ndvi (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Tockner, K.; Malard, F.; Ward, J.V. An extension of the flood pulse concept. Hydrol. Process. 2000, 14, 2861–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Choi, H.; Kim, D.; van Oorschot, M.; Penning, E.; Geerling, G. Bio-geomorphic alteration through shifting flow regime in a modified monsoonal river system in Korea. River Res. Appl. 2023, 39, 1639–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.-H.; Gao, J.-E.; Zhang, M.-J.; Wang, F.; Zhang, T. Sediment deposition and overland flow hydraulics in simulated vegetative filter strips under varying vegetation covers. Hydrol. Process. 2016, 30, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lannergård, E.E.; Fölster, J.; Futter, M.N. Turbidity–discharge hysteresis in a meso-scale catchment: The importance of intermediate scale events. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.P. Sediment concentration versus water discharge during single hydrologic events in rivers. J. Hydrol. 1989, 111, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunsolus, E.H.; Binns, A.D. Effect of morphologic and hydraulic factors on hysteresis of sediment transport rates in alluvial streams. River Res. Appl. 2018, 34, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).