Abstract

For the majority of its existence, Addis Ababa has had predominantly low-quality housing with inadequate water and sanitation services. However, in 2004, the government-led condominium housing development project started changing the availability and quality of these services. Our team has performed a systematic review of articles dealing with this housing development project and related water and wastewater issues. The results of the review show that over 208,000 condominium housing units with modern water and sanitation infrastructure were built between 2005 and 2021. The condominium housing units have a significantly higher per capita water consumption of 60.5 L/d compared to 17 L/d for the city’s old low-quality Kebele houses. The city has had to more than double the pre-2005 water supply and expand its very limited wastewater treatment capacity from a mere 7500 m3/d to more than 185,000 m3/d in response to the new demand. Overall, both the IHDP and private housing development have increased the quality of life for over 30% of Addis Ababa’s residents by providing modern cooking, bathing, and toilet facilities. Despite this, water supply interruptions are persistent and require a sustainable solution.

Keywords:

Addis Ababa; condominium; water; wastewater; sanitation; urbanization; Sub-Saharan Africa; slum upgrading; sustainable cities; MDG 1. Introduction

Sub-Saharan African countries are rapidly urbanizing, with an annual average city population growth rate of 4.5 to 6.5% between the year 2000 and 2015 [1]. Unfortunately, in 2014, 55% of urban dwellers in Sub-Saharan Africa lived in slums [2] with inadequate water, sanitation, and other related services. The eleventh United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goal is to “make cities, human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable” [3]. This goal recognizes the increasing concentration of the global population in cities and the associated needs of city life such as clean air, reliable water supply, waste disposal, and access to convenient transportation. It also includes the need to enhance the livelihood of billions of “slum” dwellers. The Commission on Sustainable Development has discussed the challenge of making cities sustainable, focusing on the principles of provision of “shelter for all” and “promoting the integrated provision of environmental infrastructure: water, sanitation, drainage, and solid waste management” [3].

As both the capital and the largest city in Ethiopia, Addis Ababa serves as a hub for political, diplomatic, economic, and urban development activities. The city consists of a sprawling urban environment, with a 2024 estimated population of 4.11 million [4]. Addis Ababa’s population grew at an annual rate of 2.1% between 1994 and 2007 [4]. Despite this, inadequate and slum-like housing with poor water and sanitation services has been Addis Ababa’s mark until the mid-2000s. Historically, a socialist political environment between 1974 and 1991 greatly constrained the construction of new homes and led to a critical housing deficit. Around 2004, the Government of Ethiopia began financing and managing the construction of condominium complexes that were mortgaged to residents in one of the largest such programs in the world. As the scale of housing development is very large and has significantly changed the housing make-up of the city of Addis Ababa over a relatively short period, it is important to carefully examine how it has impacted water consumption and supply, as well as wastewater generation and management. Here it should be noted that rapid and large-scale housing development impacts social, economic, health, and other complex aspects for residents of Addis Ababa, beyond water and wastewater issues. As Ethiopia has underpopulated urban centers, with the second largest city having only about 1/10th of the population of Addis Ababa, it is expected to experience a high rate of urbanization in the near future in response to the rapid population increase. Thus, understanding how large-scale urban housing development impacts the water and wastewater sector will help with planning sustainable urban housing development in Ethiopia and in other Sub-Saharan African countries that are undergoing rapid urbanization.

This review paper explores housing development, specifically the water and wastewater management efforts, and challenges that accompany housing development. The objectives of the research study are to answer the questions below:

- -

- How has the condominium housing project affected domestic water consumption in Addis Ababa?

- -

- How has the water supply (quantity and source) changed following housing development?

- -

- What impacts does housing development have on household sanitation, related wastewater generation, and management?

- -

- Are residents receiving adequate and sustainable water and wastewater services?

We answer the questions above by conducting a review of relevant published articles. The methodology we used to find, review, and analyze the articles is presented below. While we have chosen to undertake a review of relevant publications as an approach, a primary and/or secondary research approach can also be taken to answer the above questions. We hope that this review paper helps future researchers in designing efficient research projects while taking into account what has already been published by other researchers.

2. Materials and Methods

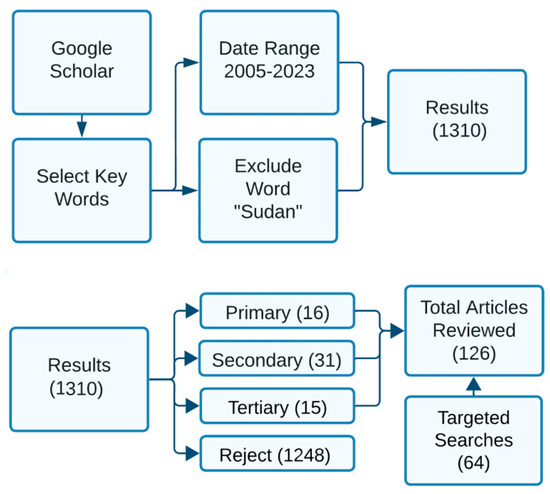

The main body of research found in this project was completed using a systematic literature review and targeted searches (Figure 1). This review was completed by searching a predefined set of keywords in Google Scholar and then reading the abstract of the results and categorizing the articles. The keywords used were Addis Ababa, condominium, water, consumption, and distribution. Two filters were applied to the search results to enhance the relevance of the results. The first filter was a time frame from 2005 to 2023. This filter was based on the date that the condominium project was implemented. The second filter was applied from 2005 to 2007 and excluded the word “Sudan”. This was carried out to reduce the number of irrelevant results related to South Sudan. As South Sudan achieved its independence in 2005, the surge in developmental activities and its proximity to Ethiopia could have been the reason for the Google Scholar search results we had to exclude.

Figure 1.

A flow chart of the approach used in the systematic literature review.

Once the abstracts of the search results were read, the abstracts were sorted into one of four categories. These categories were primary, secondary, tertiary, and rejected. These articles were sorted based on the relevance of the title, abstract, and number of hits on keywords. Primary results were categorized by specific information regarding residential demographics and water/wastewater data, as well as infrastructure and management aspects of the condominium complexes. Secondary results contained general information about the condominium program, urbanization in Addis Ababa, and city-level water metrics. Tertiary results included additional background information regarding Addis Ababa as well as semi-relevant information. Rejected results were classified as information that did not apply to the scope of the project.

Additional sources of information were also gathered outside of the literature review methodology using targeted searches in order to fill gaps in some aspects of the research topic that were not addressed using the initial systematic literature review. Targeted searches involved using topical keywords on Google Scholar such as “Ethiopian Census Reports” and “household hygiene in Addis Ababa”. These targeted searches were the primary method of finding information on the pre-condominium period (pre 2005). Finally, targeted searches on a web search engine were used to find 7 references for determining part of the timeline for the construction of IHDP condominium complexes and wastewater treatment facilities. While these 7 newspaper and commercial references are not scholarly, they were only used to obtain general information and determine the construction timelines. Outside these 7 references, the other references used were scholarly, consisting of peer-reviewed journal and conference articles, student thesis, and reports from reputable institutions, giving us high confidence in the quality of the numbers and findings reported.

The analysis of the reviewed articles was conducted using both qualitative and quantitative methods. To facilitate this analysis and address the research questions, a qualitative summary was first used to establish the background of housing in Addis Ababa. This included a brief history of the city and its housing development prior to the launch of the IHDP condominium program. Following this, both qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted to summarize the number and types of houses built in Addis Ababa after the implementation of the IHDP condominiums. This step helped establish the necessary context for comparing water usage between the pre- and post-condominium periods. Available quantitative data was then used to indicate temporal trends in water and wastewater service capacity for the pre- and post-condominium periods.

Subsequently, the focus shifted to aspects of water supply, examining the sources of water used, the quantity supplied, the type of access available, and the performance of the water distribution system. Following this, qualitative and quantitative analyses were applied to summarize household sanitation conditions in the pre- and post-condominium periods. Next, a combined qualitative and quantitative summary of domestic wastewater generation and management was provided for both pre- and post-condominium periods. To address the experiences of condominium dwellers regarding water and wastewater services, a qualitative analysis of studies that surveyed residents was performed. Finally, focus was shifted to a qualitative analysis of the reviewed articles on the sustainability of water and wastewater services. The study concludes by identifying existing knowledge gaps and offering recommendations for future research.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Background to Housing in Addis Ababa

Addis Ababa (originally Finfinnee) was founded in 1886 by Emperor Menelik II (years of reign: 1889–1913) of Ethiopia and became the capital city of Ethiopia in 1892 [5,6]. The initial organization of Addis Ababa was centered on Emperor Menelik II’s government structure, with his top generals occupying various parts of the city at the time, which was much smaller in footprint [6]. Emperor Menelik II installed modern infrastructure and introduced many services throughout Ethiopia, particularly in Addis Ababa. These included telephones, vehicles, associated roads, hospitals, hotels, restaurants, and non-religious schools [5]. It should be noted that this positions Addis Ababa as one of the first non-colonial modern cities in Africa. Following the death of Emperor Menelik II, various internal political developments slowed down the development of the city until the 1930 coronation of Emperor Haile Selassie I (1930–1974). Emperor Haile Selassie’s early reign saw the construction of more roads within the city, which were further expanded during the 5-year Italian invasion of Ethiopia in the Second World War (1936 to 1941). Following the conclusion of the Second World War, Addis Ababa experienced an active growth period until the early 1960s, mainly in roads, commercial buildings, a few modern apartment buildings, public service infrastructure, foreign embassies, and Pan-African Organizations (ECA—Economic Commission for Africa, and OAU—Organization of African Unity) [7].

Land ownership in Addis Ababa during Emperor Haile Selassie I’s reign was dominated by those of high status and to a limited extent by middle-class bureaucrats, with as much as 90% of the city’s land owned by 10% of Addis Ababa’s residents [5,6,7]. Affluent residents used their land ownership privileges to build low-quality housing (mostly single-room homes made from adobe walls) for rent to the majority of city residents. The city had 470,000 residents in the early 1960s, following 15 years of peaceful life after the conclusion of the Second World War [8]. Following the socialist revolution of 1974, which established a new government, a proclamation banned ownership of more than one urban property and renting homes for income generation [5]. The government nationalized the low-quality houses and started renting them directly to the residents who were renting them from the previous owners. These houses are commonly known as ‘Kebele’ houses and constituted nearly 55% of the total housing units in 1984 [8]. It is generally agreed upon that the rental rates that the government used for these Kebele houses were very low and quite affordable to even the poorest of residents. On the other hand, most of these houses only had a single room, almost universally lacked indoor water plumbing, and only featured a water tap in the yard, shared among several households, and pit latrines of various qualities, which were shared amongst many households. The new socialist government formed a housing agency called the Agency for Administration of Rental Housing (AARH) and, through the agency, embarked on a limited number of modern apartment building and housing projects in collaboration with other socialist countries [5]. The AARH, based on Habtewold, 2016 [9], only built 66 apartment buildings and villas for a total of 8623 housing units. In addition to these constructed units, the AARH also administered nationalized housing that was of higher quality (as opposed to Kebele homes). Based on the 2007 census, the housing units that the AARH rented consisted of 15,096 units, or 2.40% of the total housing units [8,10]. Around 1984, Addis Ababa was reorganized into Zones, Woredas, and Kebeles (with a decreasing order of jurisdiction). During the socialist regime (1974–1991), construction of new homes in Addis Ababa by private residents was limited to professional associations (teacher’s unions, doctor’s unions, etc.). The first national censuses conducted in 1984 shows that Addis Ababa had a population of 1.42 million residents and 259,555 housing units [8].

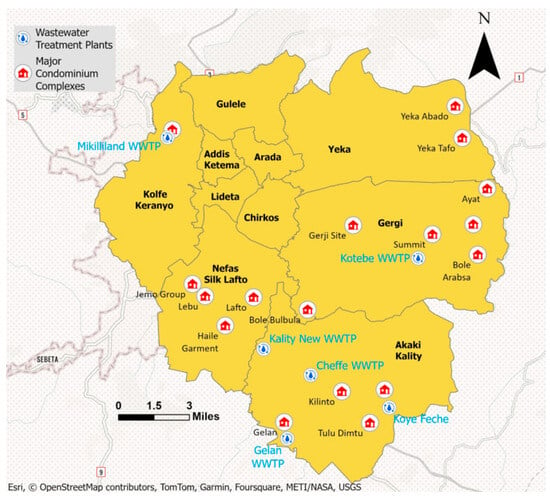

In 1991, the socialist government was replaced by a new government. The new government abolished socialism and encouraged the participation of the private sector in various enterprises including the construction of houses. In the year 2000, the new government also reorganized Addis Ababa into ten new administrative structures called sub-cities (see Figure 2). Woredas and kebeles continue to be used along with sub-cities. The government also instituted a new urban land lease system in 2002 and started encouraging investments in all urban areas, especially in Addis Ababa. The third national census conducted in 2007 shows that the population of the city had increased to 2.7 million, with 628,986 housing units [8]. Wubneh reported a further breakdown of the type of housing units present in Addis Ababa and indicated that only 25% of the total housing units were Kebele houses compared to 55% in 1984 [8]. An example of a group of Kebele houses can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

A sub-city level map of Addis Ababa with major condominium complexes and wastewater treatment plants shown. Sub-city names are bolded for easier reference.

Figure 3.

A group of Kebele houses in the Kazanchis area (a) and a condominium building in the Ayat condominium complex (b). Photo credit: (a) Tesfayohanes Yacob (2024) and (b) Amha Sertse (2024). Used with permission.

In this context of rapid construction and development that started post 1991 and took off at a much faster rate starting from 2000, the government started demolition of Kebele homes in the inner parts of Addis Ababa. The empty plots were then distributed to investors for the construction of commercial buildings. Many of those displaced by the demolition of the Kebele housing were moved to the outskirts of Addis Ababa, where apartment buildings were constructed and provided to them under a pilot re-housing project. The demolitions expanded greatly after 2006 as the Integrated Housing Program (also known as Condominium Housing Program) went into full swing.

3.2. The Condominium Housing Program

The condominium housing project, launched in 2004 as a pilot program with the German Technical Cooperation Agency (GTZ), aimed to optimize low-cost pre-cast and cast in situ construction methods used in Ethiopia [11]. The city of Addis Ababa decided to then embark on a larger-scale housing program with the GTZ, with the initial goal of building at least 10,000 housing units per year [11]. The first set of homes built in the pilot phase consisted of 28 buildings, which were four to seven stories in height [12]. Per design specifications, the condominium buildings were to be built in a fashion that required no major maintenance in the first 10 years and at a minimum would last for up to 50 years [11]. According to Ejigu, condominium buildings were initially designed with three to five stories, made up of one- to three-room housing units, sometimes even four-room housing units [13]. Furthermore, within each unit were water features such as showers, kitchen sinks, and hand sinks. Additionally, between buildings, there was a common room for 3 to 5 of the buildings to conduct communal activities such as cooking, animal slaughtering, clothes washing, and social events [13].

The condominium housing project was officially launched in 2005 by the Ethiopian Ministry of Works and Urban Development under the Integrated Housing Development Program—IHDP [14]. The program aimed to alleviate housing shortages resulting from increasing population growth as well as address the dilapidated Kebele houses for low-income urban residents [11].

In 2008, the housing shortage in Addis Ababa was estimated to be about 300,000 homes, combined with an additional 136,330 Kebele homes that were to be replaced [11]. To put these numbers into perspective, the 2007 national census showed that there were 628,986 houses in Addis Ababa, highlighting the immense demand of residents [10]. By 2009, 60,000 houses were built in Addis Ababa, and about 30,452 of these homes were transferred to new homeowners [11,15]. This pace of construction was unprecedented when compared to the approximately 2000 modern houses with indoor plumbing built per year between 1994 and 2007 [10,16]. The construction was not limited to Addis Ababa but extended to regional cities in the first few years of the project. Developments outside Addis Ababa were suspended around 2010 as a result of the low percentage of people taking up homes due to low income [14]. Also, the limited ability of residents outside Addis Ababa to pay back the loans and their opposition to constructing high-rise buildings exacerbated the low take-up [14]. Despite this, 69,921 condominium units were constructed outside Addis Ababa before the suspension of construction.

The government continued to focus on housing developments in Addis Ababa and introduced four payment schemes: 10/90, 20/80, 40/60, and housing associations. The first three schemes entail a 10, 20, and 40 percent down payment by the homeowners while the housing association involves a full payment of costs upfront. Registrations for these schemes started in June 2013, with 865,000 people having been registered in the 40/60, 20/80, or 10/90 housing programs by 2014 [17]. A systematic literature report on the number of condominium units built over time is not available. Using both literature and newspaper article sources, we estimate the number of condominium units built and transferred to residents in Addis Ababa between 2007 and 2022 in Table 1. We report the number of condominium units built separately from the number of units transferred to owners as there was a time gap between when condominium units were completed and when they were transferred (delivered) to their owners due to lengthy administrative processes. The construction of the condominium complexes happened throughout the city, with most of the complexes built in areas that were previously considered outskirts of the city. Over 50 complexes were built over the years, with the complexes containing as few as five buildings and as many as several hundred. This shows how entirely new neighborhoods of various spatial scales were created as a result of the IHDP. Figure 2 shows the location and names of seventeen major complexes housing more than 10,000 people. By the year 2021, there were 208,000 condominium units transferred to residents, and assuming 4.1 persons per condominium unit [18], 852,800 people are expected to have been living in the IHDP condominium units. Based on the 2021 population projection of 3.77 million Addis Ababa residents [4], 22.6% of Addis’s residents lived in the IHDP’s condominium units in 2021. This large percentage shows how much of an impact the IDHP was having on the city and its residents, highlighting the importance of understanding how such a large-scale development impacts various aspects of life, including this paper’s chosen focus of water and wastewater services. An example of an IHDP condominium building is given in Figure 3.

Besides the IHDP condominium program, construction of new and modern single-family homes has increased since 2005 [19,20]. Woldegerima et al. used analysis of ortho-rectified aerial photographs to estimate how an area of various types of physical infrastructures, including modern single-family homes, changed between 2006 and 2011 [19]. The category of ‘villa and single stories’ quantified by Woldegermia et al. represents single-family modern houses that are expected to feature indoor water plumbing and sewage connection [19]. The 2007 Ethiopian national census provides detailed housing information on Addis Ababa. We used the census data and the single-family modern house area estimates provided by Woldegerima et al. to estimate the number of single-family modern houses built between 2007 and 2021. As a first step, we used the single-family modern house area estimates for 2006 and 2011 (4820 and 6884 hectares, respectively) provided by Woldegerima et al. [19] to linearly interpolate and extrapolate area estimates for 2007, 2010, 2015, 2020, and 2021. We then found the area per single-family modern house for 2007 by dividing the area estimate (5232.8 hectares) by the 36,663 homes with indoor plumbing reported in the 2007 census to calculate the area per home for single-family modern houses. We then assumed the same ratio of area per house and calculated the number of modern single-family homes with indoor plumbing for the years 2010, 2015, 2020, and 2021. We calculated that in 2021, there were 77,154 modern single-family homes with indoor plumbing. Based on the number of condominium units transferred in 2021 (208,000 units), there were 2.7 condominium units for every single-family modern house. The number of single-family modern houses in 2010, 2015, and 2020 were also determined to be 48,232, 59,801, and 74,262, respectively. Assuming 4.2 people live per a single-family house [10], we determined that in 2021, 324,048 residents were living in these modern single-family houses. Thus, combined with condominium residents, in 2021, a total of 1.177 million people (31.2% of Addis Ababa’s residents) lived in homes that had indoor plumbing and generated sewage. This is in comparison to the less than 5% of Addis residents who had indoor plumbing in 2007 [18]. This shows a sixfold increase in households with indoor plumbing over a 14-year span, highlighting the rapid transformation of Addis Ababa. We now turn to explore how this large increase in people living in modern homes with indoor water access is impacting water use and wastewater generation, as well as management, by comparing the pre-condominium and post-condominium periods.

Table 1.

Timeline of IHDP condominium completion and transfer in Addis Ababa.

Table 1.

Timeline of IHDP condominium completion and transfer in Addis Ababa.

| By Year | Condominium Units Built | Condominium Units Transferred | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 30,000 | 11,000 | [11,21] |

| 2009 | 60,000 | 30,452 | [11,15] |

| 2010 | 78,000 | 53,000 | [14] |

| 2011 | 100,000 | 66,000 | [5] |

| 2015 | 178,482 | 136,000 | [22,23] |

| 2019 | 233,388 | 176,000 | [24,25] |

| 2020 | Not Reported | 208,000 | [26] |

| 2021 | Not Reported | 208,000 | [26,27] |

| 2022 | Not Reported | 233,000 | [27] |

3.3. Water and Sanitation Services in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

3.3.1. Pre-Condominium Period

Water Usage

Prior to the proliferation of IHDP condominium complexes, most water connections to households were through yard pipe connections [28]. According to the national census of 1994, more than 98.4 percent of the city population received safe water from either the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority (AAWSA) or private wells and springs [16]. The 1994 census revealed that about 26.8% had private connections (with the majority of these being yard connections instead of inside the house), 25.6% had a shared yard pipe connection with other households (within a shared compound), and 45.3% obtained water from water taps found outside the compounds where they lived [16]. It should be noted that some of the last fraction (45.3%) were residents living outside AAWSA supply areas and received clean water via private (informal) water vendors [29]. Teshome cited a 2005 WorldBank study and reported that nearly 190,000 homes out of a total of 638,000 were constructed in illegal plots, with 60,000 homes being classified as slums [30]. Many of the illegal homes were typically constructed near the ‘edges’ of the city and often paid higher prices to receive a connection from AAWSA [29] due to the need to do earthwork to connect them to the existing distribution lines. Those who were not able to get connected or had frequent service disruptions were forced to purchase water from informal vendors at a premium to what AAWSA charges [29]. Desalegn also reported that close to 94% of Addis Ababa residents used yard pipe connections in 2004 based on AAWSA data [28]. It is important to understand the type of water access residents have as that can impact the way they use it. Yard connections require households to use containers to bring water to their homes for use. This can introduce household hygiene issues as re-contamination of water in containers can take place [31].

Previous investigators have determined that the biggest predictor of per capita water consumption is whether the water access is via a yard connection or an in-house connection [32,33]. A 2005 city-wide study by Desalegn [28] determined an average water consumption of 16.7 ± 6.3 L per capita per day for Kebeles found in Addis (n = 303 Kebeles). The study also found an average of 3.5 families connected to a single tap/service point, with a total of 171,880 domestic connections throughout the city. The analysis by Desalegn also showed outliers in consumption in some Kebeles (as high as 150 L per capita per day consumption). These outliers and the Kebeles in the higher range of the reported consumption tended to be concentrated in a few areas of the city [28]. A second field study by Sharma and Bereket across three poor urban neighborhoods in Addis Ababa found a similar average per capita water consumption of 17.0 L from surveyed households [34]. A per capita water consumption of about 17 L per day is much smaller than the typical per capita consumption of 40 L per day estimated by previous international studies featuring a yard pipe connection [33].

Water Supply

Addis Ababa is located at the foot of the Entoto Mountain range in the northern direction and is at an elevation of 2355 m. The Entoto Mountains supply a significant amount of spring water and are one of the first sources of water the city relied on during its early days. The main agency responsible for water and waste services in Addis Ababa was formed in 1971 under the name of the Addis Ababa Water and Sewerage Authority—AAWSA [8]. The first surface water reservoir, Gefersa, along with its treatment plant, was built just west of Addis Ababa in 1945 and expanded in 1996 to supply 30,000 m3/d [35,36,37]. A second surface water reservoir, Legedadi, was built East of Addis Ababa in 1974, followed by a subsequent expansion of Legedadi and the construction of a new reservoir called Dire in the year 2000 [36]. The Legedadi and Dire reservoirs together supplied about 140,000 m3/d [28,36]. AAWSA, in 1999, completed the construction of a groundwater wellfield in the southern part of the city, with about 52,000 m3/d being supplied [36]. The combined surface and groundwater resources allowed for water production of nearly 220,000 m3/d in 2005 [28]. Thus in the pre-condominium period, AAWSA utilized both surface water and groundwater to meet water consumption needs [28], with 76% of the water supplied to Addis Ababa coming from surface water sources. AAWSA, in 1991, finalized a Stage III water resources project plan and a preliminary study to supply adequate water for Addis Ababa residents by the year 2020 [38]. The plans included a groundwater wellfield at Akaki, three new dams (Dire, Gerbi, Sibilu), and associated infrastructure [38,39]. Delays in the implementation of planned Stage III water resources development led AAWSA to prioritize emergency projects (Stage IIIA), thus allowing it to finish the first set of groundwater wells, the Dire reservoir, and the expansion of thr Legedadi reservoir by the year 2000 [36].

Distribution System

Due to its large size, the city of Addis Ababa has an extensive water distribution network. Most of the primary and secondary water mains prior to 2005 were found North of the Kirkos sub-city, and very few existed in the Akaki-Kaliti and Nefas Selk Lafto sub-cities [28]. In 2005, the network featured 40 distribution service reservoirs, 13 sub-systems (elevation zones), and a total of 200,000 unique customers [28]. Water distribution systems lose water due to a number of factors, and one way of quantifying the water loss is through accounting of water that is dispatched to the system but not billed (called non-revenue water). The city-wide non-revenue water percentage is defined as the ratio of the volume of non-revenue water to the volume of water dispatched to the distribution system. Desalegn studied Addis Ababa’s non-revenue water percentage by comparing the total amount of water produced to the sum of individual customer meter readings (billed amount) [28]. The Addis Ababa distribution network has had high levels of non-revenue water percentage, with the city level percentage in 2005 ranging from 19.86% to 45.99% depending on the month and a one-year average of 31.93% [28]. Desalegn attributed the non-revenue water mainly to leaks in the distribution system and under-metering as a result of meter errors [28].

Domestic Liquid Waste and Wastewater/Fecal Sludge Generation, Collection and Treatment

Household sanitation prior to the commencement of the IHDP condominium housing project featured both low quality and quantity. In the pre-condominium period, the dominant forms of sanitation facilities in households of Addis Ababa were either private or shared latrines (ventilated improved pit latrines (VIPs) or regular pit latrines). In the national census of 2007, it was shown that 70.7% of Addis’s households used either a private or shared latrine. The vast majority of these latrines (80%) were shared between multiple households [10]. Table 2 summarizes the type of sanitation facilities in households over the 20 years preceding the start of the IHDP condominium project. A modest increase in the percentage of households who use flush toilets is seen between 1985 and 2007, from 12.3 to 14.9% [10,32]. The data also shows an extensive decrease in the percentage of households with no access to sanitation facilities in the same time period: 31.4 to 14.3% [10,32]. It is also shown that the majority of the sanitation facility upgrades for the households that lacked sanitation facilities were in the form of using pit latrines (56.3 to 70.7%).

Table 2.

Sanitation access type in the pre-condominium period.

Another important aspect of sanitation that is relevant to households is the availability of liquid waste drainage systems that can be used to handle cloth and food preparation waste, as well as personal hygiene waste (for example: showering, hand washing, and brushing). It should be noted that in this regard, most of the Kebele houses in Addis Ababa fared very poorly and met the UN-Habitat definition of being classified as slums [40]. Overall, only 5.8% of Addis Ababa’s homes in the pre-condominium period had indoor plumbing in 2007 [10], negatively affecting home activities that depend on indoor plumbing such as food preparation and personal hygiene/bathing. In 2007, only 9.1% of households had a modern kitchen with a water source and a sink, and only 18.8% had access to bathing facilities (private or shared), with the majority of the bathing facilities being outside the home [10]. In the absence of indoor plumbing, most of the residents used a plastic or metal water basin as a container over which to pour water, and also eventually as a waste container prior to disposing of it. Thus in most Addis Ababa homes, activities related to personal hygiene such as hand washing, face washing, brushing, and bathing were accomplished this way. Similarly, food preparation such as washing food items and utensils was performed over water basins. For the nearly 82.2% of residents who did not have bath or shower access with indoor plumbing, either manual bathing or paying to use the very limited communal shower facilities [41] were the options. In manual bathing, a mix of hot and cold water is typically used over a large plastic or metal container called ‘safa’ in the Amharic language. The lack of indoor plumbing and the arrangements households use to utilize water and perform critical life functions put a constraint on how much water is used, helping to partially explain the low 17 L/c/d water consumption. Pit latrines use minimal amounts of water compared to flush toilets, and more water is used in modern kitchens with a sink than when washing dishes manually into a waste vessel. While the volume of liquid waste generated is minimized, it is more concentrated with grease and fat, biological oxygen demand (a proxy of organic material), suspended solids, and microorganisms [32].

Most households in Addis Ababa thus accumulated wastewater in a plastic or metal vessel and would have to dispose of it manually. Households unfortunately did not have readily available waste drainage or sewer access in or near their homes. In fact, in 1994 less than 1% of the households had sewer connections [42]. Investigation in a pre-condominium period also showed that the stormwater drainage system in Addis Ababa had inadequate coverage and that the limited existing drainage system had significant blocking with inert materials [43]. This often led to liquid waste being dumped around houses creating a pool of unclean water, which in turn exposed residents to diseases [44]. Unfortunately, the direct dumping of liquid waste into creeks, rivers, and streams was also common in the pre-condominium period [42]. Some of the homes with indoor water access and/or flush toilet facilities used masonry septic tanks to handle liquid waste [32]. These septic tanks were without properly designed drainfields, which caused overflow and led to contamination of groundwater, surrounding streets, and stormwater drains [32]. Some homeowners directly connected their flush toilets to stormwater drains or nearby streams [16].

Prior to 1981, no centralized sewer network and wastewater treatment facility existed in Addis Ababa. The first wastewater treatment facility (Kality Treatment Plant) started service in 1981, with a subsequent second phase in 1988 and a capacity of 7600 m3/d, and was designed to serve 200,000 people [32,39]. By the end of the second phase, it had a combined 44 km of primary and 46.5 km of secondary sewer pipes [32]. The treatment plant for sewer waste consisted of a screen and grit chamber followed by a series of stabilization ponds [32]. It also contained drying beds and digestion tanks for pit latrine waste and septic tank sludge, albeit with inadequate capacity to handle the volume of waste the city generated [32]. Fifteen years after its construction, the sewer system was collecting 4500 m3/d at 35,000 equivalent people capacity and had a total of 110 km of sewer pipes [16]. AAWSA added a second wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) called Kotebe in 1999 with a capacity of 4000 m3/d [39]. The Kotebe WWTP, in its initial iteration, featured 20 drying beds and 10 liquid treatment lagoons and was primarily designed to treat pit latrine waste and septic tank septage [39,45]. The locations of both the Kality and Kotebe WWTPs can be seen in Figure 2.

Along with the sewer network and treatment plants, the city also provided pit latrines and septic tank-emptying services. In 1988, there were 25 vacuum waste tanks owned by AAWSA that provided 6 to 8 pit latrine-emptying services per vehicle per day at a cost of 14 USD per single service [32]. Due to crowded neighborhoods without adequate road infrastructure, access to latrines was a serious issue faced by AAWSA in using vacuum trucks to remove latrine waste [32]. It is reported that only 60% of the latrines in Addis Ababa were accessible by vacuum trucks [16]. By 1999, the number of vacuum trucks operated by AAWSA had doubled to 50 but was still inadequate to meet the needs of a big city [16,43]. Unserved households with pit latrines resorted to manually emptying and dumping the waste into local water bodies such as streams and drainage systems [16]. The problem of dumping wastewater was worse in the expanding areas of the city where a deficit of planned sewer and storm drains led to the dumping of waste in public areas, rivers, and streets [29]. In addition, due to a lack of facilities, roughly 50% of sewage waste generated from informal housing was disposed of in public places [30].

Addis Ababa has two major river catchment areas named Little Akaki and Big Akaki [46]. Major rivers within these catchment areas include the Little Akaki, Jemo, Shegole, Big Akaki, Ginfle, Kebena, and Kechene rivers [46,47,48]. The lack of proper management of domestic liquid waste in the pre-condominium period had a direct consequence on the water quality of surface water bodies such as creeks, streams, and rivers. In addition to domestic liquid waste, improper release of commercial and industrial waste has also been documented to pollute surface water bodies in Addis Ababa [47,48]. The quantitative relative contribution of domestic, commercial, and industrial waste to surface water pollution was not obtained during this review but is an area where further research is warranted.

3.3.2. Post-Condominium Period

Water Usage

As discussed in previous sections, post 2005, the construction of single-household homes and multi-story residential condominium complexes accelerated, increasing the number of housing units in the city. Most of these new housing units (whether in a single-household house or within multi-story condominium buildings), contained private access water that was directed indoors to multiple locations where it was needed. Additionally, the newly constructed homes and condominium residential units contained features such as showers, kitchen sinks, and hand sinks that facilitated food preparation and personal hygiene. At the same time, these useful and modern features also led to a significant increase in water demand as compared to households that used yard pipe connections. In the case of the Yeka Abado condominium complex, a study reported that the per capita water consumption in 2021 was 65 L/c/d [49]. Atilaw used the total billed water and an estimate of the number of people living in the Yeka Abado condominium complex to determine the per capita daily consumption [49]. When this is compared to a pre-condominium average of 16.7 L/c/d reported by Desalegn [28], it represents an increase of 289%. This shows the strikingly different characteristics of water consumption between people living in modern condominium units vs. people living in ‘Kebele’-style houses. A study performed at a decentralized wastewater treatment plant serving the Mikililand condominium complex in 2011 reported an average measured influent flow rate of 1421 m3/d for an estimated 25,200 residents of the condominium complex [16]. As the actual study was conducted during the generally dry months of December and January, assuming all the influent wastewater to the treatment plant was due to water consumption by residents at the Mikililand condominium complex (and not due to stormwater infiltration and inflow), it points to a per capita consumption estimate of 56 L/d. Taking an average of 56 L/c/d and 65 L/c/d gives a 60.5 L/c/d estimated average water consumption for condominium residents in Addis Ababa. When comparing this estimated average per capita water consumption of 60.5 L/c/d with the typical global per capita consumption estimate for multi-pipe indoor water access of around 150 L/c/d [33], we find it to be lower by 60% than the typical global number. Using a recently reported average consumption of 173.2 L/c/d from a Chinese study on urban domestic water consumption in 286 cities for the year 2015 [50], we can see that Addis Ababa condominium residents’ per capita water consumption is lower by 65% compared to the Chinese urban average per capita water consumption. Based on a comparison with global numbers [33,50], it can be said that the reported 60.5 L/c/d water consumption in Addis Ababa condominium complexes is low. This is likely a relief for AAWSA as it is continuously working to meet the demand created by the increased water consumption from modern homes with indoor plumbing. Supply constraints (water supply interruptions), cost consciousness, and environmental stewardess could be some of the reasons for the lower per capita water consumption seen in Addis Ababa condominium complexes.

Estimating city-wide per capita water consumption numbers is important for infrastructure planning and assessment purposes. Assefa and co-workers estimated Addis Ababa city-wide water consumption by using aggregate water bill data (2013 to 2017) and population numbers of eight AAWSA supply areas to calculate supply area average per capita water consumption estimates [51]. The per capita daily water consumption averages reported for the supply areas ranged from 18 to 89 L/person/day and resulted in a city-wide average of 40 L/c/d [51]. The authors noted that this number is only half of what AAWSA uses for planning purposes. We used the pre-condominium per capita water consumption of 17 L/c/d [28,34] as the water consumption of the estimated 2.597 million people who lived in homes without indoor plumbing in 2021 and 60.5 L/c/d water consumption for the 1.177 million people who lived in condominium units and other modern single-family homes with indoor plumbing [16,49] to calculate city-wide per capita water consumption. The population weighted average of those two per capita water consumption values yields a consumption of 30.6 L/c/d, which is 24% lower than the 40 L/c/d average reported by Assefa and co-workers [51]. One of the reasons for this discrepancy could be that our study only looked at domestic household water consumption, whereas the number reported by Assefa and co-workers is inclusive of non-domestic customers [51]. While per capita water consumption is one metric we can use to study water usage, it is certainly not the only one and this limitation should be considered when interpreting the per capita water consumption increase observed for the post-condominium period.

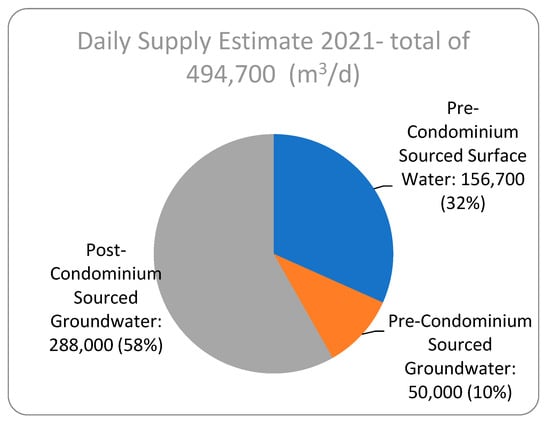

Water Supply

The city of Addis Ababa continues to utilize both surface water and groundwater to meet water consumption needs [51]. With the growing population, AAWSA had to increase its overall water supply to meet the growing demand. The city’s surface water resources as of 2021 are the Gefersa, Dire, and Legedadi dams. These are combined with the groundwater resources consisting of the Legedadi wellfield, the Akaki wellfield, and other smaller wells within the city [51,52]. A further breakdown of the city’s water resources can be found in Figure 4 and Figure 5. As of 2021, the overall water production from these water sources is estimated to be between 447,333 and 542,000 m3/d [37,52]. Post 2000, all newly added water supply projects have been groundwater well projects with a total of 288,000 m3/d [37,52]. As of 2021, thus, around 68% of Addis Ababa’s water supply comes from groundwater sources [37,52]. Figure 4 summarizes the source and capacity of water supply as of 2021. The calculated average water production for the city in 2021 (494,700 m3/d) is over double compared to what it was in 2005 during the pre-condominium era (220,000 m3/d) [28,37,52]. The difference in water production between these periods is calculated to be 274,667 m3/d. This vast increase in water production from 2005 to 2021 is a direct response to the expanding population of Addis Ababa, the increasing construction and business water demands, and the post-condominium increased water demand at the household level. In 2005 the population of Addis Ababa was estimated to be 2.643 million; in 2021 that estimate rose to 3.774 million [4,10]. Within these 16 years, there was approximately a 1.130 million-person increase in the population.

Figure 4.

Source of daily water supply to Addis Ababa in 2021 based on the type of supply and when the supply was initiated (pre or post condominium).

Figure 5.

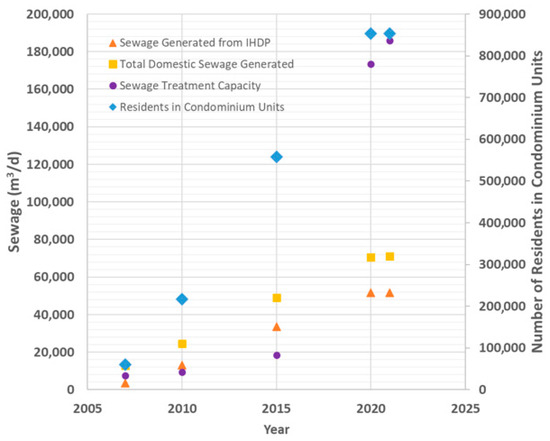

The domestic sewage generated from IHDP, total domestic sewage generated, installed sewage treatment capacity, and the number of IHDP residents for the years 2007 to 2021.

Distribution System

Since the commencement of the IHDP condominium housing project, the water distribution system in Addis Ababa has grown to provide water access to residents within the condominium complexes and other single-family housing developments in what were previously the outskirts of the city. The current water distribution system in Addis Ababa is a vast series of pipe networks that cover 90% of the city [49]. This distribution system delivers water throughout the city on a semi-consistent basis, in the more extreme cases with some sub-cities only having access to water for less than 36 h out of the week [49]. As new pipes and related distribution equipment are used to supply the large condominium complexes, the efficiency of the distribution system has improved and resulted in lower non-revenue water. For the year 2020, the distribution system in the relatively new Yeka Abado Condominium complex was found to have a non-revenue water percentage of 24.6% [49]. The vast majority of the non-revenue water (23.65% of the total water supply) was attributed to a physical water loss [49]. Atilaw calculated this water loss by comparing the amount of water entering the distribution system against the amount of water consumed within the condominium units [49]. The input and consumption data was measured using direct measurement of input flow rates using ultrasonic meters and processing of water bill records [49]. Atilaw identified high pressure in the distribution system, poor pipe fitting connections, slow response to leaks, and structural damage due to water pressure loss during supply interruptions as the main culprits of the non-revenue water [49]. The calculated average water loss percentage in the Yeka Abado condominium complex was much lower than the cumulative water loss within the city reported in 2005 [28]. In 2005 the city-wide one-year average non-revenue water percentage was 31.93% [28], showing a reduction in non-revenue water loss percentage when compared to what was observed in the Yeka Abado condominium complex [49]. We hypothesize that this decrease in non-revenue water percentage can be attributed to a combination of new pipes and increased water production throughout the city. Increased water production theoretically should reduce the number of new leaks in pipes due to fewer occurrences of negative pressure throughout the distribution system. However, it should be noted that a research investigation would have to be conducted to test the hypothesis.

AAWSA water supply data as reported by Kitessa and co-workers indicates that domestic water use in Addis Ababa represented 66.2% of all water consumed within Addis Ababa [53]. Taking this domestic use percentage, the average yearly city-wide non-revenue water percentage reported by Desalegn [28] (31.93%), and the previously calculated water production increase of 274,700 m3/d (between 2005 and 2021), an additional 123,771 m3/d domestic consumption was calculated (between 2005 and 2021). Relating this to the 1,130,882-person population increase between 2005 and 2021 allows for a greater perspective on the increase in water production. Assuming that each new resident of Addis Ababa consumed 60.5 L/day of water (as estimated in this study for current condominium residents), this would equate to a daily water consumption of 68,418 m3/d. This means that when only looking at the increased population and water consumption from 2005 to 2021, there is a surplus between domestic production and consumption of 53,353 m3/d. When looking at the entire city’s water production in 2021 (494,700 m3/d), with non-revenue water at 31.93% and domestic water usage at 66.2% [28,53], it was calculated that 222,909 m3/d of the city-wide production will be consumed domestically. On the other hand, if each resident in Addis Ababa in 2021 had a water consumption of 60.5 L/day, there would be a total domestic consumption of 228,327 m3/d. This would then imply a deficit of 5418 m3/d. The deficit is highly sensitive to the daily per capita water consumption of Addis Ababa’s residents. If the domestic per capita daily water consumption of the entire city was 80 L, this deficit in 2021 would have been 79,011 m3/d. This highlights the lengths that the city of Addis Ababa must achieve to provide the required amount of water if the city-wide per capita daily domestic consumption increases from 40 L/c/d to 80 L/c/d. If Addis Ababa had reached a domestic per capita average daily water consumption of 173.2 L, as reported by a recent study on water consumption in Chinese cities [50], the deficit would have dramatically increased to 430,748 m3/d. This high sensitivity of the deficit to the city-wide per capita water consumption is a challenge to AAWSA, as expanding the existing water supply requires extensive planning, budgeting, and time. Thus researching the factors affecting how rapidly per capita water consumption may rise in the context of the rapidly developing Addis Ababa is very important. It will also be beneficial to identify ways of keeping the average per capita water consumption from rising rapidly. Some studies have modeled the water supply and demand for Addis Ababa and provided forecasts for the years ahead [35,53]. A detailed modeling study on water supply and consumption in Addis Ababa for various assumptions was reported by Alemu and Dioha [35]. Alemu and Dioha used various population increase cases (4.57 to 7.07 million) and a high-end per capita water consumption assumption of 150 L/c/d to estimate a range of gaps between production and consumption for Addis Ababa [35]. For the year 2030, they reported a gap ranging from a low of 750,684 m3/d to a high of 1,597,260 m3/d [35] depending on the living standard and water management scenarios considered. Another modeling study by Kitessa and co-workers looked at both water and energy management for Addis Ababa city and forecasted the water production–consumption gap for assumed conservation, supply, and demand management interventions [53]. They reported a 2030 supply–demand gap ranging from 742,466 m3/d to 898,630 m3/day [53].

One way that AAWSA is combating water shortages is by encouraging large commercial and industrial water consumers to source water through private or commercial boreholes [37,54]. In addition, AAWSA, in accordance with the original Phase III water supply plan, is still working towards constructing the Gerbi and the Sibilu reservoirs [38,55] and the Robi-Jeda reservoir [55]. AAWSA has also made new plans to continue developing new wellfields, in various areas of the city and a new surface water reservoir called Robi-Jeda [55]. These projects, if completed on time, would allow for the city’s overall water production to reach 1,763,000 m3/d in 2029 [55].

Domestic Liquid Waste and Wastewater/Fecal Sludge Generation, Collection, and Treatment

Wastewater collection and management in Addis Ababa became an urgent need following the commencement of the IHDP condominium housing program. The condominium units, as a feature of their design, included a modern kitchen with a sink and a bathroom with a hand sink, flush toilet, and a shower [14,52]. Some residents use a cloth washing machine as indicated in a survey study of a single condominium block (n = 26 households) in the Summit condominium complex [56]. The study reported that 21% of respondents used washing machines only, and another 26% used both machines and hand-washing clothes [56]. Liquid waste generated from each building is collected and directed to local septic tanks, to the sewer network, or to decentralized treatment plants. The city of Addis Ababa is divided into three catchment zones: Kaliti, Akaki, and Eastern [57]. Addis Ababa uses an independent sanitary sewer system that is not combined with stormwater [58]. The Kaliti catchment is the site of the majority of the pre-condominium sewer network. The initial years of condominium housing wastewater management focused on the use of septic tanks with minimal decentralized or centralized treatment options. Issues of overflowing condominium septic tanks causing pollution have been documented [59]. The first decentralized wastewater treatment plant to be constructed, specifically for the IHDP condominium housing project, was the Mikililand WWTP in 2008 [16]. The Mikililand WWTP used waste stabilization ponds and was designed with a capacity of 1814 m3/d for an estimated Mikililand condominium complex resident population of 25,200 [16]. Unlike previous treatment plants, the Mikililand WWTP was constructed by the Addis Ababa Housing Development Agency (AAHDA) [60]. In 2010, AAWSA converted some of the sludge-drying beds of the Kotebe WWTP to waste stabilization ponds, added a headworks chamber, and started treating the wastewater originating from the Ayat condominium complex [45]. The new sewage treatment capacity of the Kotebe WWTP was 2000 m3/d and was designed to serve close to 25,000 residents [45]. The next wastewater treatment plant to be built was the Gelan WWTP and it had a capacity of 7000 m3/d [39]. While the exact timeline is not documented in published sources, it is estimated to have been constructed around 2011, based on when the Gelan condominium complex was put into service. Between 2010 and 2015, a bulk of the condominium units built during the first phase of the program were being handed over to residents, and a sheer increase in the generation of sewage was seen [22,23]. Taking the 136,000 condominium units that were put into service by 2015 [22,23], and using an assumption of 4.1 residents per condominium residence unit and a per capita water consumption of 60.5 L/c/d, this points to a minimum of 33,735 m3/d of domestic sewage generation from condominium units. Similarly, using the 59,801 modern single-family houses estimated to be present in 2015, a 4.2 person per household estimate [10], and a 60.5 L/c/d water consumption, a total of 15,195 m3/d of sewage is estimated to have been generated. Thus in 2015, an estimated 48,930 m3/d (12.9 mgd) of total domestic sewage was generated. At this point in 2015, sewage generation far outpaced treatment capacity.

Moreover, sewer connections with existing treatment plants were highly limited. AAWSA responded to the urgent need by starting to deploy 14 decentralized package wastewater treatment plants that featured membrane bioreactors (MBRs) and anaerobic baffled reactor (ABR) technology from 2015 to 2017 [57,61,62]. The total capacity for the decentralized package plants was reported to be 20,000 m3/d [61,62]. At least one installed MBR was shown to be operating at a much lower capacity than the design flow rate: 350 m3/d vs. 1700 m3/d [61]. It was also shown that the specific MBR unit required intensive energy input and regular chemical cleaning [61]. AAWSA then switched from MBR technology to ABRs, which do not require aeration and work without membranes. Locations of the decentralized package treatment plants can be found in the publication by Ali et al. [62]. The next wastewater treatment plant to be built was the Koye Feche Upflow Anaerobic Sludge Blanket Reactor (UASBR) plant, with a capacity of 30,000 m3/d (see Figure 2 for its location). The Koye Fetche WWTP entered service in 2017, becoming the largest WWTP at that time. Soon after, a new large 100,000 m3/d UASBR and trickling filter-based treatment plant at Kaliti came online in 2018 [63]. This brought the total wastewater treatment capacity to 168,414 m3/d (37.0 mgd). Researchers have previously shown UASBRs to be an energy-efficient technology for tropical climates, generally preferred over a conventional activated sludge process [64]. The last three sets of treatment plants to be installed between the years 2018 and 2021 are the Cheffe 1, 2, and 3 WWTPs, with a combined capacity of 25,000 m3/d to bring the total sewage treatment capacity to 185,814 m3/d (49.1 mgd). These plants featured UASBRs and trickling filter technology [65]. Figure 5 shows a summary of estimated domestic sewage generation and treatment capacity from 2007 through 2021, along with the number of estimated residents in IHDP condominium complexes. In Figure 5, we estimate the domestic sewage generated from the IHDP and modern single-family home residents, assuming that all residents consume water at an average of 60.5 L/c/d and that all water consumed is turned into wastewater.

Unfortunately, while the treatment capacity has increased greatly, the lack of sewer infrastructure has prevented the Kaliti wastewater treatment plant from operating at full capacity, and multiple reports state that it is operating at less than 60% of its design capacity of 100,000 m3/d [57,66]. Addis Ababa has been steadily increasing trunk, secondary, and lateral pipes for the sewer network, albeit slower than the WWTP capacity increase. Worku reported the presence of 70 km trunk and 400 km secondary and lateral pipes by the year 2017 [39], representing a 60% increase in trunk and a 760% increase in secondary and lateral pipes compared to 1988. Much faster progress was made over the next three years, with 115 km trunk and 913 km secondary and laterals reported by the year 2020 for the Kality catchment area [67]. The unused treatment capacity in the Kality WWTP is creating an opportunity to add previously unserved populations if the sewer network can be expanded and households are able and willing to connect. A study on reasons behind the lower sewer connectivity in the Kaliti catchment reported household’s lack of awareness, connection fee cost, and preference as some of the reasons for not connecting with the sewer network [57].

Addis Ababa is at a crossroads in regard to wastewater collection and management. In the last census of 2007, the dominant forms of sanitation were private and shared pit latrines (70.7% of total households), with only 14.9% of households having private or shared flush toilets [10]. As has been estimated in this study, the post-2005 housing boom of both single-family homes with indoor plumbing and the popular IHDP condominium housing project has resulted in the addition of more than 248,491 residence units that need sewage collection and treatment services by 2021. At the same time, homes from the center of the city (of which the majority were Kebele houses without indoor plumbing), have been demolished to make way for commercial high-rises, and their residents moved into condominium complexes, resulting in a reduction in homes without indoor plumbing and sanitation. Thus the water demand and waste generation profile of Addis’s households has changed drastically. Interestingly a large number of the original condominium unit assignees (owners) rent or sell the units and find cheaper housing for themselves [68]. These cheaper houses are more than likely to be Kebele-style homes without indoor plumbing and, in many cases, informally built homes [68]. A study reported a 53% rental rate for condominium units in 2019 [67]. Thus, the net impact of the IHDP condominium housing project may not only be increased water consumption and wastewater generation from the condominium units themselves but also from added ‘Kebele’-style homes built to accommodate some of the previous condominium unit owners.

While the city of Addis Ababa has focused the last 10 years (post 2014) on constructing sewer lines and modern wastewater treatment plants, there are still a large number of residents who live in homes without indoor plumbing and flush toilets, who need vacuum truck fecal sludge collection services. Moreover, treatment techniques specific to fecal sludge are still needed for these households. Development of techniques that allow the co-treatment of fecal sludge from pit latrines with sewage in traditional wastewater treatment facilities have great potential to increase the overall efficiency of wastewater management in Addis Ababa. Gelaye reported that in 2018, a total of 162 vacuum trucks were available for collecting fecal sludge from pit latrines, with only 100 of them in working condition [68]. Gelaye further reported that only 20% of city residents have access to vacuum trucks due to inaccessible streets [68]. As an official census has not been conducted in Ethiopia since 2007, no definitive number of residents who still require vacuum truck services can be given. However, based on the current condominium units and other single-family modern house number estimates provided in this review, we estimate the percentage of households who use private or shared pit latrines to have dropped significantly from 70.7% in 2007. Birhanu et al. used satellite image analysis to estimate the percentage of people living in informal settlements in 2020 to be 54% [69]. While not all informal settlement residents would be pit latrine users, most are expected to be, and thus we can see that the number of private or shared pit latrine users has gotten much lower than the 70.7% of households who used private or shared pit latrines in 2007. This demonstrates how much transformation the city of Addis Ababa has undertaken during the course of the urban housing development reviewed in this paper. It also shows the continued work needed to expand fecal sludge collection to all pit latrine users instead of the currently reported 20% coverage [68].

3.4. Experiences of the Dwellers

While the IHDP condominium project has faced some difficulties regarding the overall quality of the buildings, the fixtures within, and the utility supply, residents have a high level of satisfaction with the condominium units. A study performed by Frew in 2008, through surveys of residences from eight condominium complexes transferred in 2007, reported that out of the 285 residents interviewed, 201, or 70.5%, reported having to do maintenance on their home [21]. Out of the 201 residents who performed maintenance, 81.5% of dwellers reported personally maintaining the water pipes within their condominium dwellings [21]. More recently, in a 2018 survey of residents conducted in the Yeka condominium complexes, the issue of needing to do maintenance in relatively newly transferred units (less than two years old) was reported [70]. In this study, 25% of residents (out of the 132 interviewed) stated they had to perform major maintenance on their condominium units to continue to make them livable [70], pointing to issues of construction quality. The majority of the study respondents (61%) rated their condominium units as having a very good or good overall quality [70]. The levels of satisfaction of the residents with the quality of their showers and kitchens were high (99% and 75% of the respondents gave a good ranking or above [70]).

Furthermore, through Frew’s survey, it was found that while 98.2% of responding residents had a direct water supply in their homes, 86% of respondents reported irregular water supply [21]. However, despite the irregular water supply, Frew found that most residents were pleased with their condominium units compared to their previous dwellings [21]. A 2014 survey study of four condominium complexes with a total of 263 respondents reported frequent water supply interruptions and low-water-pressure issues [71]. Surveyed residents of the condominium complexes reported supply interruptions, especially in the second through the fourth floors [71]. Overall, 46% of the surveyed residents reported not being satisfied with the utility service provided [71]. Another 2015 survey study of 50 residents in the Jemo 1 condominium complex reported that water service was irregular on the second and higher floors of the condominium complex [72]. In multiple studies, the supply problem was reported to be extreme on the fourth floor of some condominium complexes, with water being delivered as infrequently as once a week and often after midnight [71,72].

To try and offset the lack of consistent water supply, some residents within the condominium complexes have turned to harvesting rain and stormwater to supplement conventional water distribution supply [72]. Additionally, informal water reuse practices such as using laundry wastewater for flushing toilets have been reported [56,72]. However, many have also been forced to purchase water from third-party vendors to meet their immediate water needs during water supply interruptions [71,72]. These water purchases add a financial burden as well as physical strain from carrying water up flights of stairs [72]. Another major effect of the intermittent water supply is its impact on liquid waste disposal, resulting in the creation of unpleasant odors in the buildings [21]. In our literature review, we have not come across any officially established city-wide water-harvesting or -recycling practices. Adugna et al. have, however, studied the potential of rainwater harvesting in Addis Ababa from rooftops of large institutions such as hospitals, schools, and government offices [73]. They report that, in an average year, rainwater harvesting from all of the large institutions can replace up to 2.8% of the water supplied in Addis Ababa for the year 2016.

3.5. Sustainability of Water Supply and Wastwater Management and Treatment

As has been presented in the sections above, residents of the condominium housing and other single-family modern houses built since 2007 have the indoor infrastructures required for modern hygienic living. However, as water supply is critical for using these infrastructures, water supply interruptions cause serious inconveniences to residents. These interruptions can also lessen the public health benefits of the indoor infrastructures that condominium residents have access to. A particularly concerning aspect is the increasing dependence of the Addis Ababa water supply on groundwater sources (68% of the supply in 2021, as shown in this review). Current groundwater withdrawal rates are not able to supply an adequate and uninterrupted supply of water to Addis Ababa’s households. Efforts thus must be directed to ensure that groundwater withdrawal can be sustainably increased to meet the needs of its residents and supply water in a continuous manner with minimal to no interruptions until the plan to build additional surface water reservoirs (Gerbi, Sibilu, and Robi-Jeda) is completed. Birhanu et al. have modeled how additional withdrawal of groundwater from the current wellfields impacts the water levels in the wells [74]. In the scenario in which planned surface water reservoirs were not online, water levels dropped significantly, with a drop greater than 20 m in the Akaki wellfields over a span of 15 years of use, by the year 2030, while only covering 62% of Addis Ababa’s water demand [74]. This result indicates that increasing groundwater withdrawal to meet the current demand–supply gap may not be sustainable (even if feasible). Further modeling by Birhanu et al. included the scenario of the planned surface water reservoirs (Gerbi and Sibilu) coming online, along with additional groundwater withdrawal, to reduce the water demand/supply gap of Addis Ababa by nearly half by 2030 [74]. Thus, in terms of the sustainability of the long-term supply of water to Addis Ababa, the completion of the two new surface water reservoirs and the increase in groundwater withdrawal seem to be mandatory. However, these measures may not be sufficient, pointing to the challenge of maintaining a sustainable water supply for a rapidly growing city. This points to the need for a multi-faceted approach from both demand and supply sides to ensure sustainable water supply to Addis Ababa.

Impressive progress has been made in the case of wastewater treatment, with Addis Ababa expanding wastewater treatment capacity by 2400% compared to the pre-condominium period. We have, however, reported the lack of sewers to enable the full use of this treatment capacity. The construction of the missing sewer networks and the continuous and successful operation of the newly built wastewater treatment facilities over the coming years can help Addis Ababa achieve sustainability in the area of wastewater management. In addition to serving residents who have flush toilets, Addis Ababa needs to continue to collect and treat waste from pit latrines, and the successful integration of these services with sewage collection and treatment will further sustainability in the wastewater sector. Future implementation of advanced wastewater treatment for indirect and/or direct reuse of treated wastewater can increase the sustainability of urban housing and other development activities in regard to water management. Another area of reuse potential is stormwater. Currently most of the stormwater collected from Addis Ababa is directed to its rivers untreated [56]. Kitessa et al. estimated the harvestable portion of the stormwater runoff in Addis Ababa to range from 158 to 200 million cubic meters (MCMs) annually [51]. If proper stormwater collection and treatment schemes are put into place, indirect reuse or direct reuse options will be possible, including implementation of managed aquifer recharge to increase the sustainability of groundwater withdrawals from the wellfields of Addis Ababa.

4. Recommendations for Future Research

Our team’s research has been based on a systematic literature review and targeted searches of literature covering water and wastewater aspects of housing in Addis Ababa pre and post the IHDP condominium housing project. Based on the results from the analysis of the reviewed literature, we have identified areas in which additional research is needed.

The first suggestion for a research area is a detailed quantitative study of water consumption, liquid waste generation, and water reuse practices for individual households within condominium complexes and single-family modern homes. This type of study would allow researchers to obtain non-aggregated data about water use and wastewater generation. Related to this, we recommend the evaluation of the efficiency of the inbuilt features of the condominium residences such as faucets, shower heads, and toilets. Knowing the efficiency of household water features could help identify changes that could result in greater efficiency in future fixtures and lead to the development of water sustainability-related policies. A second area of research we recommend is a detailed system-wide study of the water distribution system via instrumentation and modeling (including instrumentation of selected residences) to obtain quantitative temporal and 3D spatial data on the level and quality of water supply throughout the city of Addis Ababa. This can help agencies and researchers identify strategies to increase both the duration and quality of water supply throughout the city, specifically in the condominium complexes. It can also help comprehensively quantify water loss in the distribution system and provide timely geospatial information on where leaks are occurring.

The third area we propose is the study of approaches to sustainably increase the supply of water. These would require looking at the long-term sustainability of currently utilized groundwater wells, as well as studying how fast the groundwater and surface water supply can be expanded to meet demand supply gaps. Moreover, a study of how water supply fluctuations are handled and how these impact water delivery interruptions would be extremely useful. A related research topic is the study of city-wide indirect and direct water reuse potential. Research on the cost and technical aspects of implementing an advanced wastewater treatment and an associated indirect reuse application would be timely for Addis Ababa. Equally importantly, the proper collection, management, and treatment of stormwater within the city, along with studies on how the treated stormwater can be reused directly or indirectly, are recommended. Indirect reuse research can include studies on identifying optimum recharge locations and mechanisms for aquifer recharge to supplement declining groundwater levels in the major wellfields of Addis Ababa.

The fourth area of research we suggest is on the long-term managerial aspects of the condominium complexes’ water and wastewater systems and their associated costs. This study would ideally investigate important models for the long-term management and maintenance of building-level water and wastewater pipes and infrastructure (including pumps, septic tanks, and interception tanks). The study would need to include identification of which community and government agency/agencies could be responsible for the management and maintenance of these elements. While this may sound trivial to some readers, communal high-rise shared housing is relatively new in Addis Ababa, and models for managing common water and wastewater assets are needed. The knowledge generated from such research could prove to be valuable for future designers of condominium complexes and other high-rise private housing projects within the city. A related research goal can be studying the long-term experiences of condominium complex dwellers in relation to water and wastewater services. Finally, we strongly point to the urgent need for a new Ethiopian national census (including for Addis Ababa) as it has now been 18 years since the last one. The census findings would be incredibly useful to help the city of Addis Ababa and researchers with future water demand forecasting as it would provide an updated estimate of the population of the city, detailed data on housing characterization, and demographics.

5. Conclusions

Over 22.6% of Addis Ababa’s residents lived in IHDP condominium units by the year 2021, significantly increasing the number of people with access to modern water infrastructure in their homes. IHDP homes are very popular and have greatly increased the quality of life for residents. Combined with residents of single-family modern houses, by the year 2021, 31.2% of Addis’s residents who had access to modern water infrastructure consumed water at an estimated average of 60.5 L/c/d. Addis Ababa nearly doubled water production between 2005 and 2021, using groundwater sources to meet the new demand. Despite this, water supply interruptions occur regularly, pointing to the need to find sustainable ways of increasing water supply. Centralized direct and indirect water reuse and stormwater harvesting were not part of the water supply system as of 2021, and research is needed in these areas. Addis Ababa has successfully expanded wastewater treatment capacity beyond what is currently being generated domestically. However, missing sewer networks have limited the utilization of the treatment plants. Moreover, for the residents who still require pit latrine-emptying and treatment services, there is a need to continue to expand the services and find ways of leveraging the excess capacity in the conventional sewage wastewater treatment plants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.W.Y.; Methodology, T.W.Y., C.M., E.H. and S.L.; Literature Search, T.W.Y., C.M., E.H. and S.L.; formal analysis, T.W.Y., C.M. and E.H.; writing—original draft, T.W.Y., C.M., E.H. and S.L.; visualization, T.W.Y., E.H. and S.L.; writing—review and editing, T.W.Y., C.M. and E.H.; supervision, T.W.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Cal Poly Humboldt start-up grant, K1040 to Yacob.

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created in this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Moriconi-Ebrard, F.; Heinrigs, P.; Trémolières, M. OECD/SWAC Africa’s Urbanisation Dynamics 2020: Africapolis, Mapping a New Urban Geography, West African Studies; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2020; ISBN 978-92-64-31430-6. [Google Scholar]

- UN. The Millennium Development Goals Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goal 11|United Nations—Department of Economic and Social Affairs—Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11 (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- CSA. Population Projections for Ethiopia 2007–2037; Central Statistical Agency: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2013.

- Ejigu, A. History, Modernity, and the Making of an African Spatiality: Addis Ababa in Perspective. Urban Forum 2014, 25, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garretson, P.P. A History of Addis Abäba from Its Foundation in 1886 to 1910; Aethiopistische Forschungen; Harrassowitz: Wiesbaden, Germany, 1974; ISBN 978-3-447-04060-0. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, A. Haile Selassie’s Imperial Modernity: Expatriate Architects and the Shaping of Addis Ababa. J. Soc. Archit. Hist. 2016, 75, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]