Abstract

Rainfall-driven non-point source (NPS) pollution has become a critical issue for water environment management in urban watershed systems. However, single-model use is limited to fully represent the intricate processes of rainfall-correlated NPS pollution generation and dispersion for effective decision-making. This study develops a novel cross-scale, multi-factor coupled model framework to characterize hydrologic and NPS pollution responses to different rainfall events in Shenzhen, China, a representative worldwide metropolis facing challenges from rapid urbanization. The calibrated and validated coupled model achieved remarkable agreements with observed hydrologic (Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency, NSE > 0.81) and water quality (NSE > 0.85) data in different rainfall events and demonstrated high-resolution dynamic changes in flow and pollutant transfer within the studied watershed. In an individual rainfall event, heterogeneous spatial distributions of discharge and pollutant loads were found, highly correlated with land use types. The temporal change pattern and risk of flooding and NPS pollution differed significantly with rainfall intensity, and the increase in the pollutants (mean 322% and 596%, respectively) was much larger than the discharge (207% and 302%, respectively) under intense rainfall conditions. Based on these findings, a decision-support framework was established, featuring land-use-driven spatial prioritization of industrial hotspots, rainfall-intensity-stratified management protocols with event-triggered operational rules, and integrated source-pathway-receiving end intervention strategies. The validated model framework provides quantitative guidance for optimizing infrastructure design parameters, establishing performance-based regulatory standards, and enabling real-time operational decision-making in urban watershed management.

1. Introduction

In the context of global climate change and rapid urbanization, urban water systems are facing unprecedented environmental pressures. Urbanization not only changes land use patterns, but also leads to substantial non-point source (NPS) pollution [1,2]. Generally, NPS pollution originates from various and diffuse sources rather than any identifiable discharge point in an area, which is often washed out by rainfall into urban water bodies and ultimately enters into rivers and lakes [3,4]. Pollutants, such as nutrients, suspended solids, and toxic substances, can severely degrade river water quality and result in the deterioration of aquatic ecosystems [5]. NPS pollution from rainfall runoff has become a major threat to urban water bodies [6]. These sources include (i) roadway and traffic-related runoff, (ii) roof and building facade runoff, (iii) residential lawns/urban greenspaces (nutrients and pesticides), (iv) airborne pollutants and particulate matter from industrial processes, and (v) atmospheric deposition mobilized during first-flush events [2]. These diffuse sources are conveyed via rainfall networks, overland flow, infiltration–exfiltration pathways, and finally into rivers, lakes, wetlands, or coastal waters. Therefore, effective control of urban NPS pollution has become an urgent challenge in water resource protection and management. To address this challenge, accurate characterization of dynamic rainfall-driven runoff and pollutant transport processes is crucial, which can provide scientific basis to decision-makers for effective urban water pollution management [7,8].

Given the complexity of urban water systems [9], researchers have employed various hydrological and hydrodynamic models, such as Storm Water Management Model (SWMM) [10,11], Delft3D [12,13], MIKE 11 [14], QUAL2K [15], and HEC-HMS [16], to characterize the generation, transport, and dispersion of pollutants in urban water bodies. SWMM is a dynamic rainfall-runoff modeling tool developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency since 1971, which has been widely used for planning, analyzing, and designing urban drainage systems. Based on a distributed hydrological modeling framework, SWMM focuses on detailed spatiotemporal distribution of urban surface runoff and the interactions among impervious surfaces, pipe networks, and surface flow. Consequently, it has been used to model precipitation–runoff, pollutant generation, and wash-off processes in urban circumstances [17,18]. Delft3D is open-source software released by Deltares from the Netherlands. It offers multi-dimensional analytical capabilities for modeling hydrodynamics and pollutant transportation in water bodies and enables detailed impacts of convection and diffusion on pollutant transfer, which are important in some complex aquatic environments [12,19]. However, single-model use is limited to fully represent the intricate processes of NPS pollutant dispersion in urban water systems. Although the sub-catchment discretization approach adopted by SWMM provides a reliable way for source apportionment [20], its one-dimensional (1D) simplification limits the ability to resolve complex in-stream hydrodynamics, such as three-dimensional (3D) turbulent structures, vertical pollutant diffusion, and interactions with bed sediments [21]. By coupling an unstructured 3D grid with the Navier–Stokes equations, Delft3D can highly resolve the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of river hydrodynamics and pollutant transport. Nevertheless, its application depends on accurate upstream boundary conditions, and its single use is difficult to link directly to the dynamic generation of surface pollution sources [22].

Despite extensive research on urban NPS pollution, these single-model approaches often struggle with cross-scale process representation, resolution mismatches, and event-scale extremes. This creates a significant gap in our ability to understand and predict the complete pollutant pathway from source to receiving water body, particularly under intense rainfall events characteristic of rapidly urbanizing regions like Shenzhen.

Consequently, scarce research has been found on effectively integrating high-resolution urban surface runoff modeling with in-channel hydrodynamic processes. Coordinating and integrating model datasets with different temporal resolutions is still a challenge [23,24]. Furthermore, existing coupled models have not been sufficiently validated, which constrains the feasibility and reliability of characterizing real-world complex urban water systems. Therefore, an innovative model-coupling approach developed and validated based on practical validation data can not only be of scientific significance but also provide robust support for practical decision-making in urban water quality management and pollution control.

In this study, two research questions are addressed: (i) what are characteristics of the rainfall-driven hydrological response and NPS pollution behavior in an urban watershed, and (ii) to what extent can a cross-scale, multi-factor coupled modeling framework improve prediction and process attribution compared to single-model approaches? It is hypothesized that a coupled framework will significantly enhance capability in reproducing and predicting dynamic rainfall-driven flows and NPS pollutant transfer within the watershed than the single-model approaches, particularly under intense rainfall conditions in subtropical urban environments.

This research addresses the aforementioned limitations of the single-model use by developing a cross-scale, multi-factor coupled model framework. Taking a representative worldwide metropolis with rapid urbanization (Shenzhen, China) as a validation site for a broadly applicable framework, systematic simulations were conducted on the rainfall-driven flooding and NPS pollution behavior throughout the entire “surface wash–sewer transport–river dispersion” process. By coupling SWMM for dynamic rainfall runoff and pollutant buildup/washoff with Delft3D for high-resolution depiction of pollutant dispersion in channels, we created a nested urban water environment modeling framework spanning multiple spatial and temporal scales. Moreover, a high-resolution rainfall series, a sewer-network topology database, and multi-section online monitoring data were integrated for model sensitivity analysis and validation. This work aims to (1) develop and validate a coupled model framework that can elucidate the entire “land-based generation–sewer conveyance–riverine response” process in a rainfall event, including the multi-media transport paths by which NPS pollutants move from different types of impervious urban surfaces through the drainage network to receiving channels; (2) assess the spatio-temporal distribution and environmental impacts of rainfall-driven NPS pollution with different precipitation intensities; and (3) propose strategies for effective control and management of urban rainfall-driven flooding and NPS pollution. This research makes significant contributions by (1) addressing the methodological gap in cross-scale NPS pollution modeling, (2) providing quantitative evidence of model performance improvement through coupling (with NSE values > 0.81 for hydrology and >0.85 for water quality), and (3) demonstrating the substantial pollutant concentration increases (322–596%) under intense rainfall scenarios that may be underestimated by single-model approaches.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area and Data

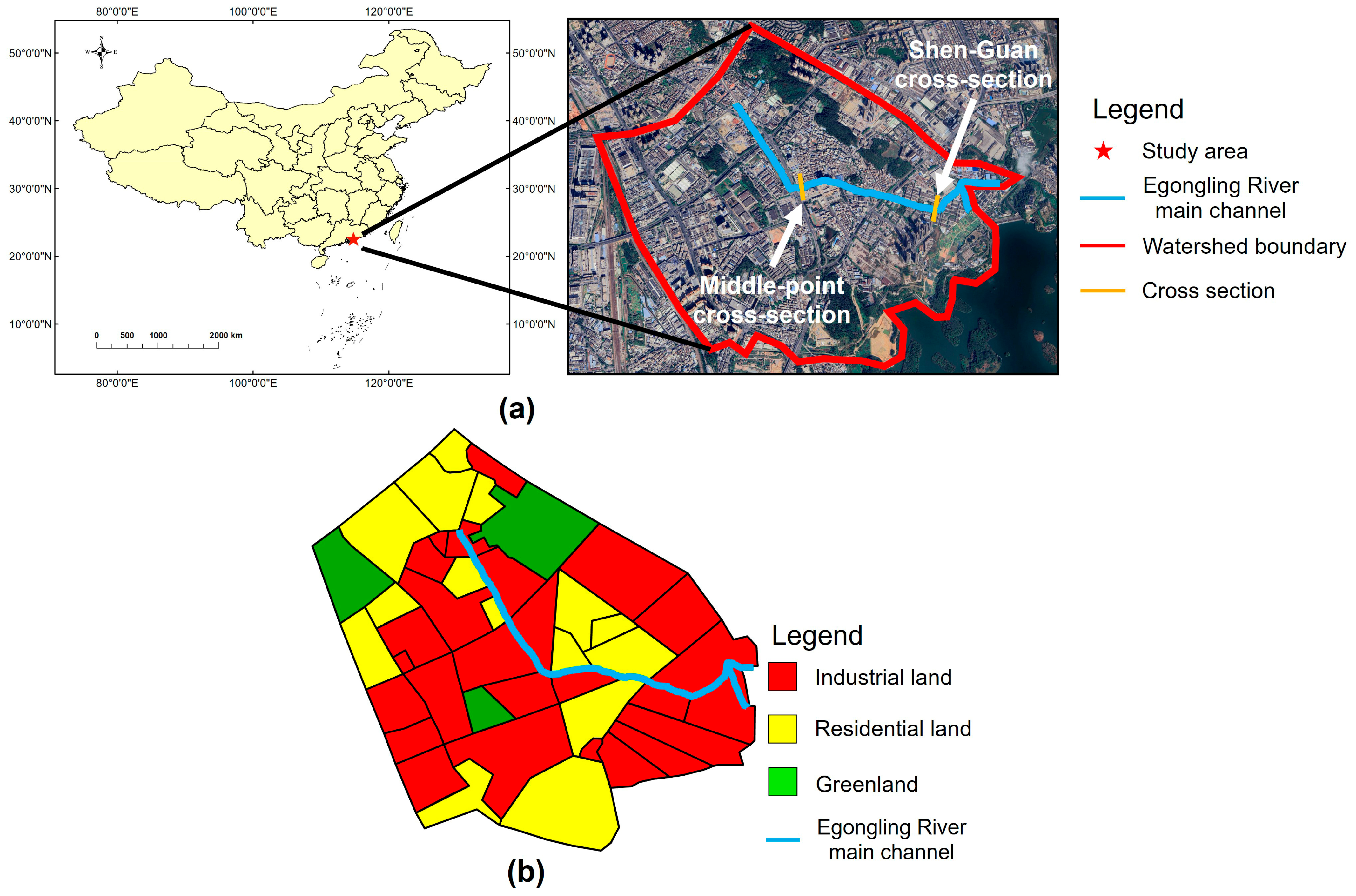

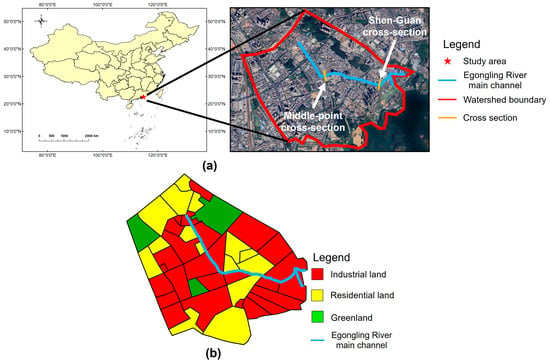

Shenzhen, selected for this study, is one of the most representative worldwide metropolises undergoing rapid urbanization in China over the last few decades, with a population of 17.98 million. The study area, the Egongling River watershed (Figure 1a), lies in Longgang District in the middle part of Shenzhen, offering a valuable context for studying the impacts of urbanization on river ecosystems. The Egongling River, located in the center of Shenzhen, flows through areas that blend industrial, residential, and greenland zones. This diversity makes the watershed an ideal area to analyze the dynamics of NPS pollution in a rapidly urbanizing environment. By studying this region, we aim to gain a deeper understanding of pollution dynamics within a typical urban river system undergoing fast development. The watershed is situated in a subtropical maritime monsoon climate zone, with a mean annual temperature of 22.3 °C (maximum 37 °C and minimum 1.4 °C), an averaged relative humidity of 80%, and a mean annual precipitation of 1933 mm. The catchment area is about 8.45 km2. The main river channel, highlighted by the blue line in Figure 1a, is approximately 2762 m long.

Figure 1.

(a) Left: geographic location of Shenzhen, China, and right: map of the study area Egongling River watershed, with the main channel in blue; (b) spatial distribution of all sub-catchments in the whole watershed, mainly determined by three land use types, namely, industrial, residential, and greenland.

Different types of datasets were collected to determine the watershed’s characteristics in the model, including hydrological observations, local rainfall records, and water quality data with pollutants including chemical oxygen demand (COD), total phosphorus (TP), ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N), and total nitrogen (TN), all of which were monitored at the Shenzhen–Dongguan (Shen–Guan) boundary river flow monitoring station. The Shen–Guan cross-section is located at almost the ending point of the Egongling River in the studied area, where it is representative to reflect the hydrological and pollution behavior from all sub-catchments within the entire watershed. In our study, the NPS was determined based on all sub-catchments set with distinct topographical, land use, hydrological, and pollution-related properties. In a rainfall event, the generation and transfer of the pollutants in each sub-catchment could present the local NPS pollution response. It should be noted that the Egongling River watershed has a drainage system with rain and sewage diversion, so we could assume no direct point source pollution in the studied area. Additionally, we used sewer-network information, underlying surface properties specified by land use categories and topography (industrial land: 55.02%, residential land: 34.35%, greenland: 10.63%) using a 5 m × 5 m digital elevation model and other relevant datasets, and regional characteristic pollution data covering both point source and NPS pollution. The local rainfall data were recorded using a tipping-bucket rain gauge (PG-210, Hebei Pinggao Electronics Technology Co., Ltd., Shijiazhunag, China) with a time resolution of one hour, and flow data were monitored using a radar flowmeter (JY.RFM-OA, Shenzhen JiuYi Sensor Information Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China) every 15 min. In the prior study, more water quality parameters including heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants were considered, with the measured concentrations lower than the national standard thresholds of Class I surface water; thus, the negligible pollution of micropollutants in the studied watershed was not discussed in this work. The selection of the four specific parameters (COD, TP, NH3-N, and TN) was determined by both scientific reasoning and practical considerations. Firstly, these parameters were chosen as representative indicators of urban NPS pollution, effectively capturing key aspects of nutrient loading typically observed in rainfall-runoff events. Secondly, they offer a balanced approach, integrating comprehensive pollution assessment with practical monitoring constraints, including the availability of appropriate instrumentation, analytical costs, and the requirements for sampling frequency. Finally, the selected parameters provide a sufficient level of data complexity for model validation while ensuring computational efficiency and minimizing redundancy, thereby optimizing the model’s overall performance. These four key water quality parameters (COD, TP, NH3-N, TN) were measured with a spectral sensor (FUV-408Plus, Hangzhou Kaimisi IoT Sensor Technology Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China) each hour and also determined following standard protocols [25,26]. All collected data sources and precision were shown in Table S1.

2.2. Model Coupling Framework

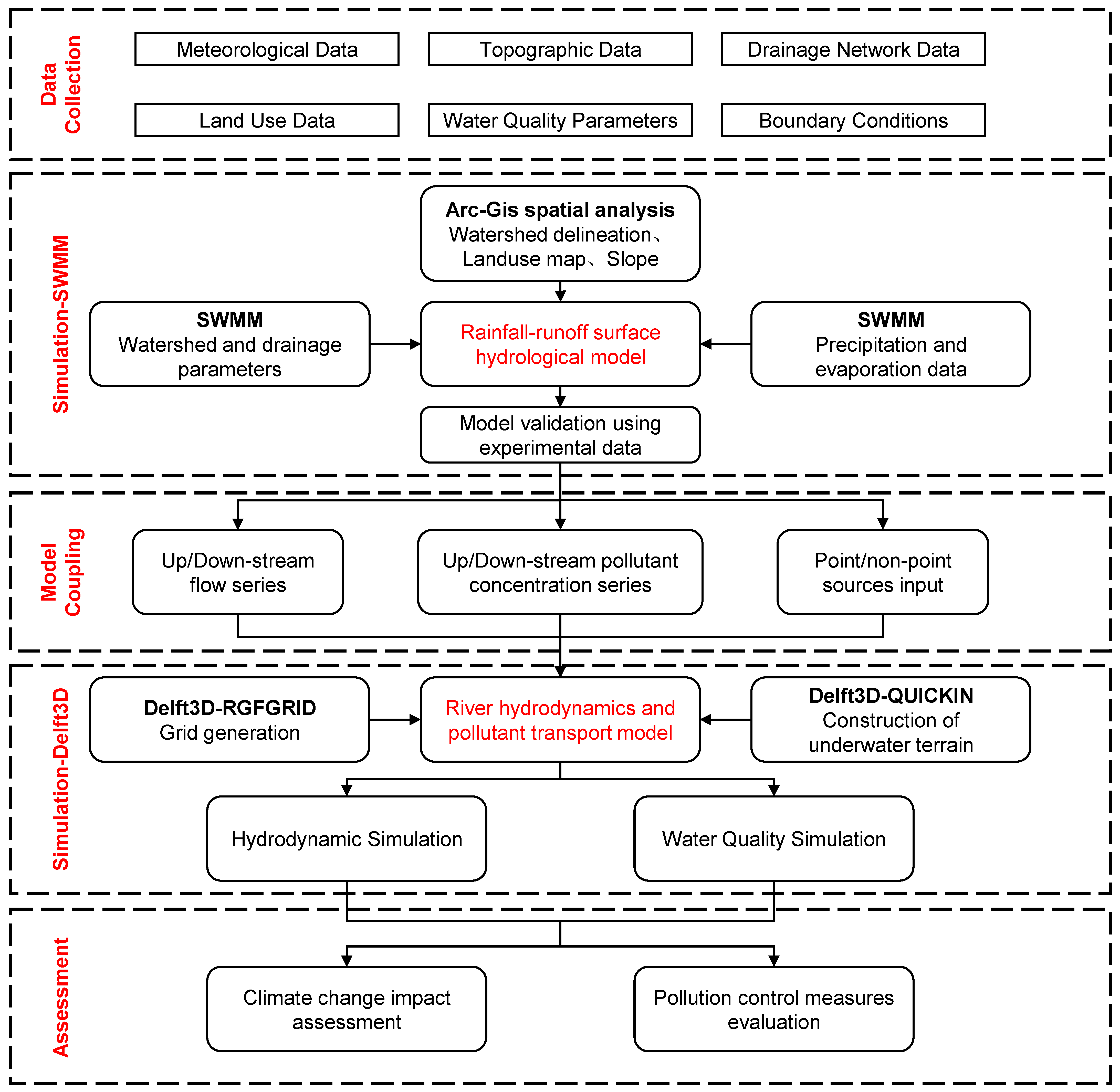

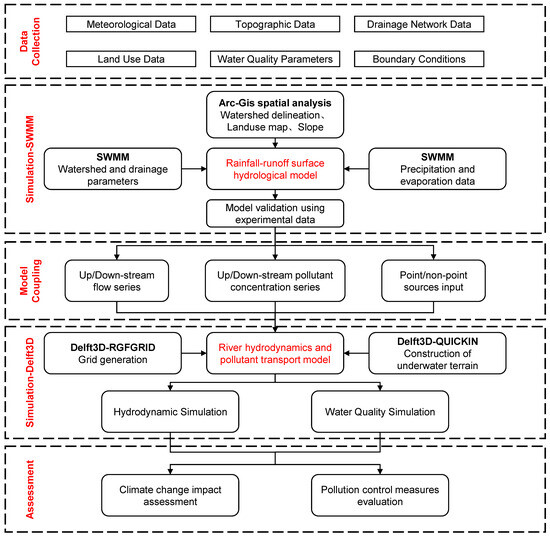

The model coupling framework was developed in five main steps. (1) Collected and screened data relevant to the study area for the model setup, including meteorology, topography, land use types, land use-correlated water quality properties, and drainage sub-catchments, which have been described in detail in Section 2.1. (2) Simulated the runoff generation and routing during a specific rainfall event using SWMM (version 5.2), and further predicted the hydrological response of the drainage network and the corresponding NPS pollution characteristics in the entire watershed. (3) Coupled the SWMM model with Delft3D (version 4.05.01), using SWMM-generated 1D hydrological and water quality data as inputs for the Delft3D model setup. (4) Implemented the multi-dimensional simulation for the Egongling River main channel using Delft3D to refine the impacts of the runoff and NPS pollution from all sub-catchments on the main channel with the consideration of river hydrodynamics and pollutant convection–diffusion transfer. (5) Validated and optimized the coupled model based on the observation data; evaluated the NPS pollution impacts under different rainfall scenarios, and proposed measures for flooding management and NPS pollution control. More details about the schematic of the coupled model framework are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Development of the coupled model framework: Technical Roadmap. SWMM: Storm Water Management Model.

In our study, a one-way coupling approach was implemented, where the 1D SWMM model simulated dynamic rainfall-driven runoff and pollutant buildup/washoff processes within the entire watershed; the output (mainly the hydrological and pollution series data of all branches) was then used as input for the Delf3D model (2D was assumed due to negligible variations in water depth direction) to simulate flow and pollutant transfer dispersion in the main channel with higher-resolution and considerable hydrodynamic impacts. While models like SWMM and Delft3D have their strengths (Table S2) [27], each also has inherent limitations in addressing the full range of hydrological, hydrodynamic, and pollutant transport processes that occur in urban rivers. By coupling these two models, we aim to combine the strengths of both: using SWMM for detailed runoff and pollutant generation modeling, while leveraging Delft3D’s advanced hydrodynamic and pollutant transport capabilities. This coupling enables a more comprehensive understanding of both the generation and dispersion of pollutants in the study area, providing a better representation of complex urban water systems.

2.3. Surface Runoff Generation and Pollutant Transport Within the Watershed

In this study, the hydrologic and pollution responses were first characterized using SWMM. The time step size was set to 1 min to achieve a satisfied balance between computational efficiency and numerical stability. The whole watershed was divided into 45 sub-catchments (Figure 1b and Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials) based on geometric, topographic information and land use types obtained using ArcGIS (version 10.8). The imperviousness, depression storage, and Manning’s roughness coefficients were calibrated using the observed rainfall-runoff data, with the calibrated values presented in Table 1. The initial flow rate was set to 0.29 m3/s, with initial water quality concentrations of COD = 30 mg/L, TP = 0.45 mg/L, NH3-N = 1 mg/L, and TN = 2 mg/L. These values were derived from the observed data, specifically representing the average flow rate and pollutant concentrations during periods without rainfall, which were used as the initial conditions for the model. An open river boundary condition was applied, allowing for natural exchange of water and pollutants at the river’s boundaries. More details of the specific initial and boundary conditions of SWMM and Delft3D are summarized in Table S4 in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Hydrological parameters in model setup. The ranges were determined according to previous studies [3,28,29].

Various physical processes in the urban hydrologic cycle are simulated dynamically based on the discrete time steps. The core computations encompass four parts: surface runoff, infiltration, flow routing, and water quality simulation. The non-linear reservoir method is adopted for its enhanced capability to represent the dynamic runoff and outflow processes, especially in urban areas with diverse land use patterns. In addition, surface runoff is handled with the non-linear reservoir method, calculating outflow with the water balance equation (Equation (1)):

where V is surface water storage (m3), P is rainfall intensity (m/s), E is evaporation rate (m/s), f is infiltration rate (m/s), t is time (s), A is surface area (m2), and Q (m3/s) is discharge computed by Manning’s equation (Equation (2)):

where n is Manning roughness coefficient, R is hydraulic radius (m), and S is the channel slope.

Infiltration is represented by the Horton model [30] (Equation (3)):

where f(t) is the soil infiltration rate at time t (mm/h), fc is the infiltration rate when the soil is saturated (mm/h), f0 is the initial infiltration rate at the start of rainfall (mm/h), and β is the decay coefficient (h−1) related to soil properties.

Flow routing is simulated by applying a simplified 1D Saint-Venant equation set [31] (Equation (4)). The 1D Saint-Venant (dynamic wave) formulation was selected because it is the standard hydraulic core of SWMM for routing in urban pipe–channel networks, explicitly solving the full continuity and momentum equations in one dimension.

where A is the cross-sectional flow area (m2), x is the space coordinate along the channel axis (m), g is the gravitational acceleration (9.81 m/s2), S0 is the channel bed slope, and Sf is the friction slope.

For water quality modeling, a 1D mass transport equation (Equation (5)) is applied to describe pollutant transport and decay:

where C is the pollutant concentration (kg/m3), x is the longitudinal coordinate along the flow direction (m), qi is the i-th lateral inflow (m2/s), Ci is the pollutant concentration of the i-th lateral inflow (kg/m3), and k is the decay coefficient (s−1).

The land use type is a key factor influencing hydrological processes and pollutant transport. In this study, three land use types, namely, residential, industrial, and greenland, were used as the main basis for dividing the Egongling River watershed into the aforementioned 45 sub-catchments (Figure 1b) with specific pollutant accumulation characteristics, which are shown in Table 2. This approach more accurately specified how each sub-catchment can respond to the rainfall-runoff and pollutant buildup processes [32]. The surface runoff module based on the aforementioned non-linear reservoir method (Equations (1) and (2)) was used to simulate the conversion of rainfall into runoff across various surface types during rainfall events. The pollutant accumulation characteristics were first determined by the experimental data provided by PowerChina Eco-environmental Group and further calibrated using the water quality data measured in the rainfall series in the model validation step. An exponential function model was employed to simulate pollutant buildup and washoff processes (Equations (6) and (7)). Furthermore, the decay coefficients for the pollutants were determined based on some previous work [33,34,35,36], which, after the parameter calibration, were set as follows: COD: 0.21 d−1, TP: 0.18 d−1, NH3-N: 0.30 d−1, and TN: 0.22 d−1.

Table 2.

Water quality parameters associated with different land use types in the Egongling River sub-catchment.

For the buildup function B, which represents the accumulated pollutant mass on the surface over time, it is given by the following:

where C1 is the maximum accumulation (kg/ha), and C2 is the accumulation rate constant (day−1).

The washoff function W represents the amount of pollutants removed from the sur-face due to runoff, as shown by the following equation:

where C3 is the washoff coefficient, C4 is the exponent that governs the relationship between flow rate and pollutant removal, and B is the accumulated mass of pollutants on the surface.

2.4. Refined Characterization of Hydrology, Hydrodynamics, and Water Quality in the Main Channel

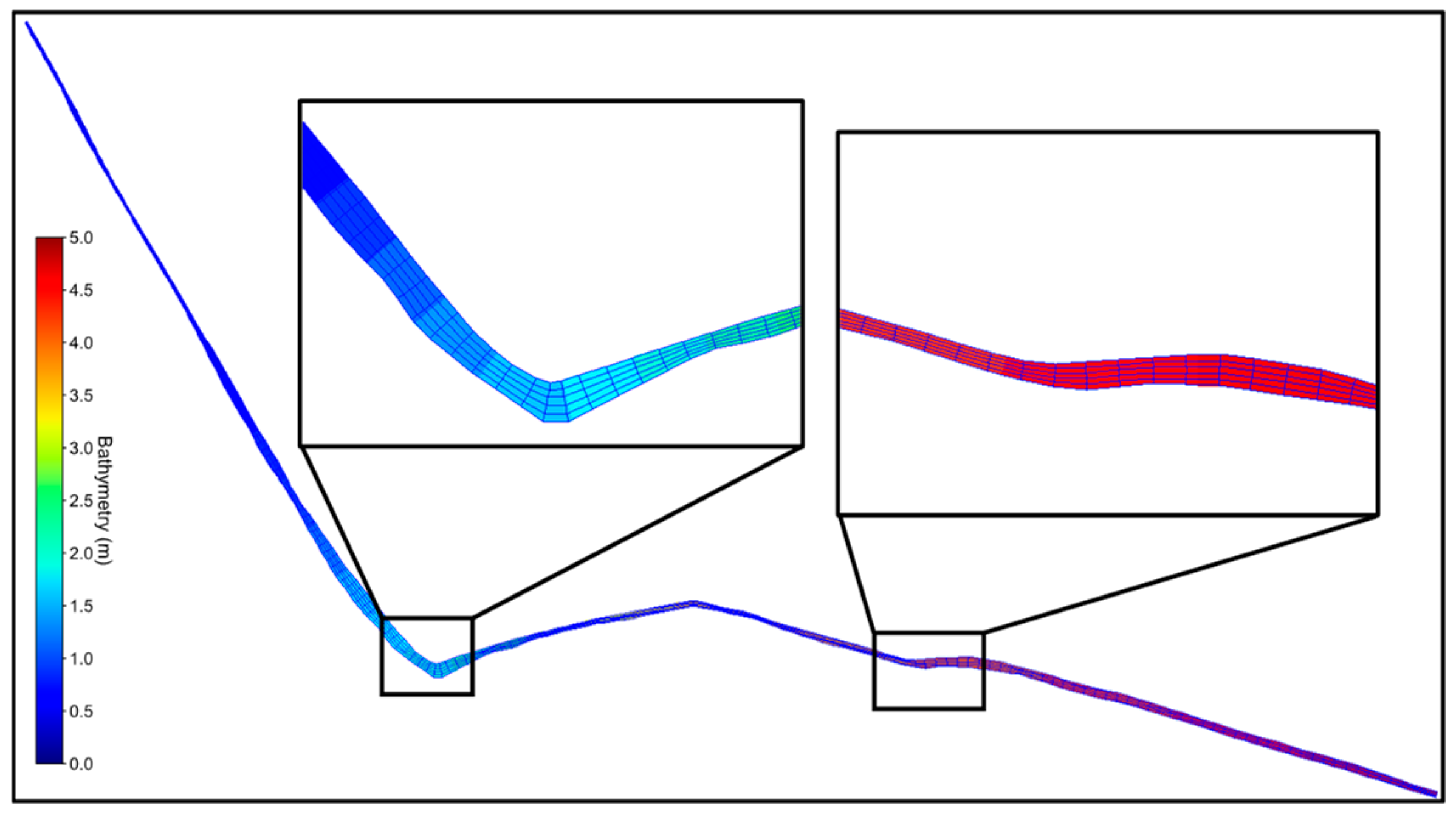

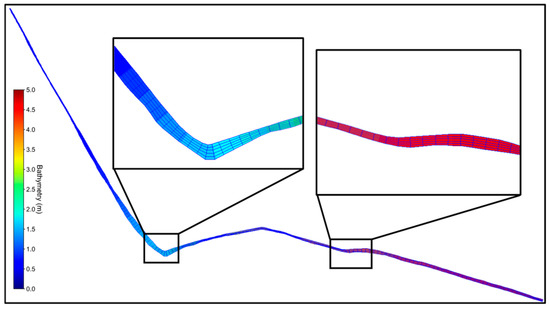

In the Delft3D package, the FLOW module is capable of accurately simulating 2D- or 3D- surface water dynamics and pollutant transport. Precise river-boundary coordinates were extracted to form the domain of the Egongling River main channel, which was discretized with a high resolution containing 1414 grid cells, as illustrated in Figure 3. The Delft3D model was configured with a time step size of 1 min to match the SWMM model. All tributary contributions were represented as point sources along the main channel, using flow and pollutant output data from the SWMM model. Appropriate water levels and pollutant concentrations in the main channel were specified to initialize the simulation. The water and air densities were defined as 1000 kg/m3 and 1 kg/m3, respectively. Bed roughness was set to 0.01. The horizontal eddy viscosity and diffusivity were both set to 1 m2/s.

Figure 3.

Top view of the Egongling River main channel and the grid distribution, with bed elevation data.

Regarding hydrodynamics, given that the water depth (around 0.5 m) of the main channel is much smaller than its width (around 12 m) and length (2762 m), the variation in depth could be negligible, and the model was effectively assumed as 2D. The finite difference method was applied to solve the Navier–Stokes equations [37] under the Boussinesq approximation and shallow water assumption, which comprise the continuity equation (Equation (8)) and the momentum equations in the ξ and η directions (Equation (9)):

where and U are the metric coefficient and the mean velocity in the ξ-direction, respectively; and V are the metric coefficient and the mean velocity in the η-direction, respectively; Qc is the change in water volume per unit area, and d is the water depth; Pξ and Pη are the pressure gradients in the ξ-direction and η-direction, respectively; Fξ and Fη are the unbalanced Reynolds stresses in the ξ-direction and η-direction, respectively; Mξ and Mη are the momentum sinks and sources in the ξ-direction and η-direction, respectively; f is the Coriolis parameter; ρ0 is the water density; vV is the vertical eddy-viscosity coefficient; and u, v, and ω are the velocity components in the ξ-direction, η-direction, and σ-direction, respectively. Since the horizontal scale (i.e., the width) of the channel is much larger than the vertical scale (i.e., the depth), the vertical changes in flow velocity were neglected.

Furthermore, the transport equation (Equation (10)) was applied to solve the pollutants mass transfer within the water body by incorporating processes such as convection, diffusion, deposition, and extra source/sink:

where c is the pollutant concentration; DH and DV are the horizontal and vertical dispersion coefficients, respectively; λd is the pollutant decay coefficient; and S represents the external input or removal of pollutants.

Variations in flow and pollutant input from all branches were obtained from the data calculated by the coupled SWMM model, which were set as boundary conditions of the main channel in the Delft3D model.

2.5. Calibration and Validation

The model was validated based on the observation data, and the predictive accuracy was improved by calibrating key parameters. In this study, The Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency (NSE, Equation (11)) and the mean squared error (MSE, Equation (12)) were applied to evaluate the goodness of fit:

where is the observed discharge at time t, is the simulated discharge at time t, is the mean observed discharge, and T is the total length of the time series.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Calibration and Validation

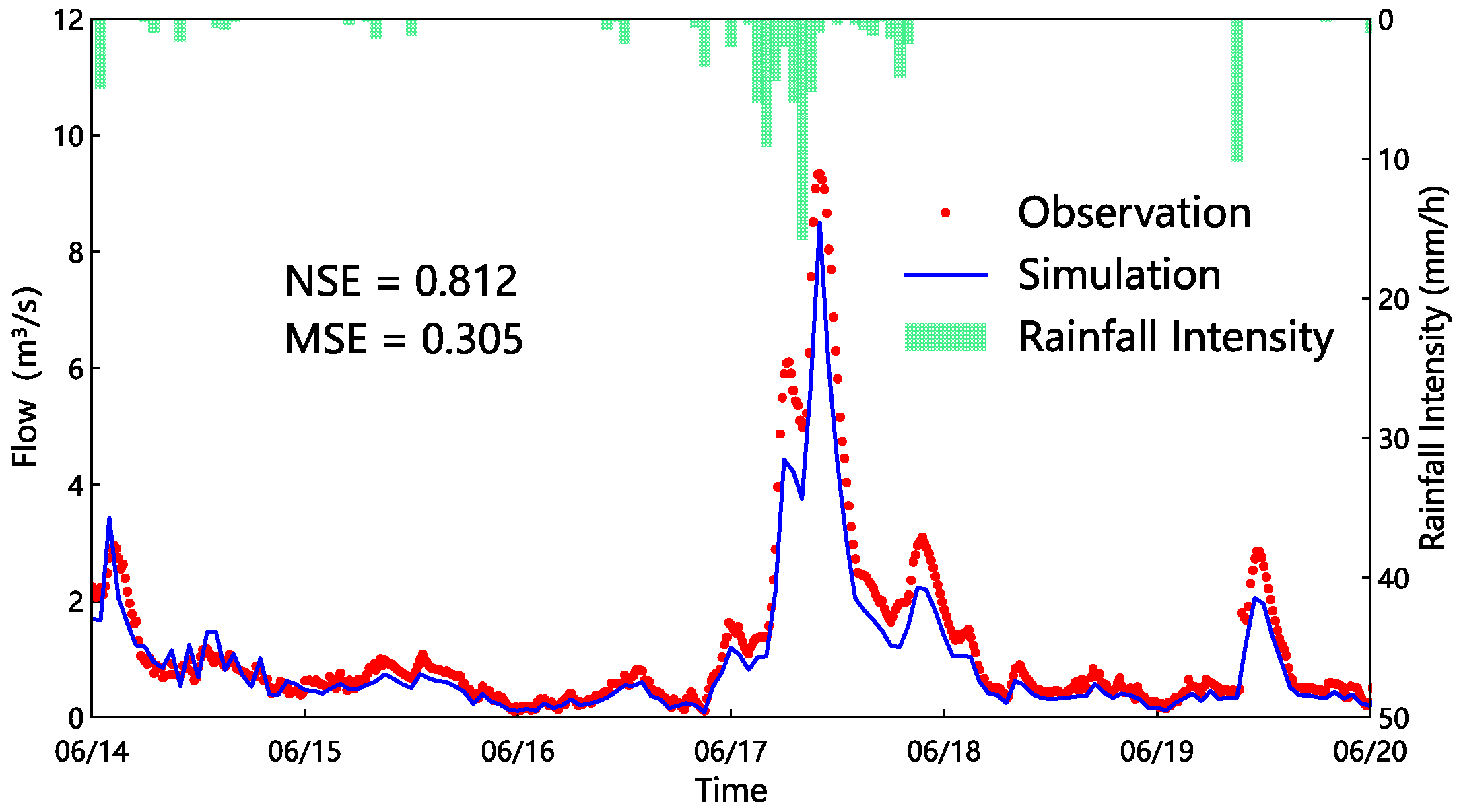

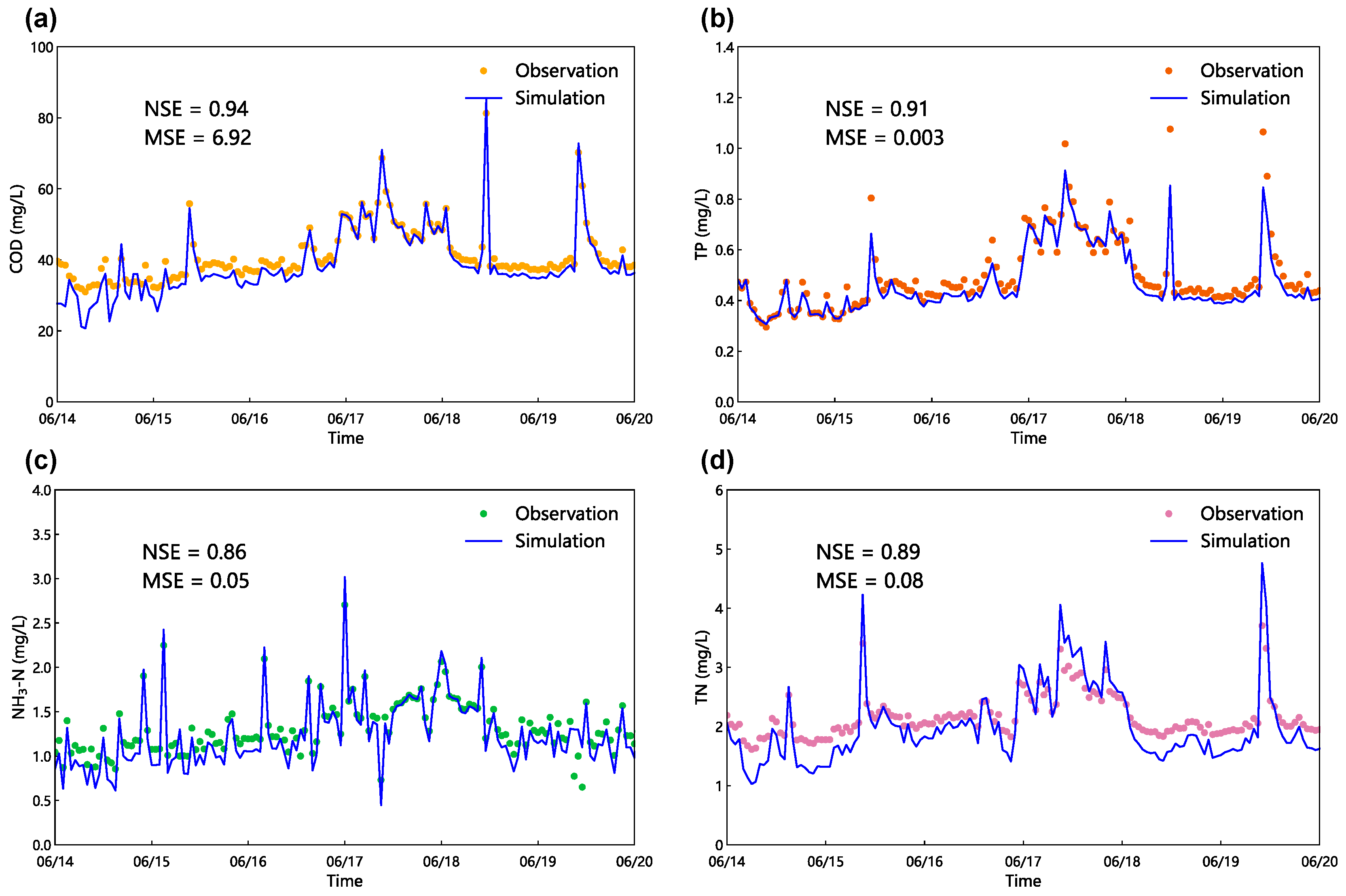

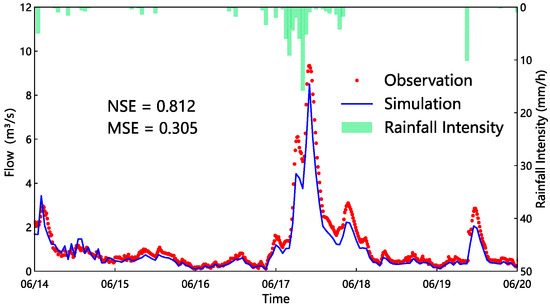

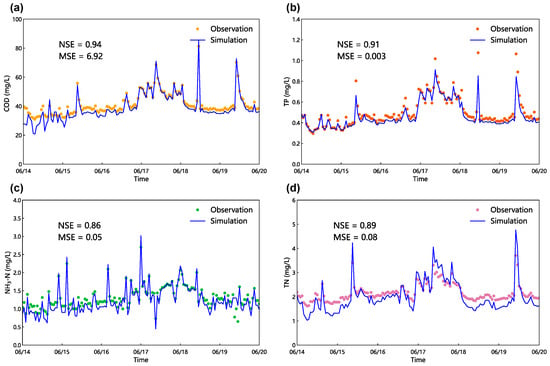

The coupled SWMM–Delft3D model was validated by evaluating the predictive accuracy first. The aforementioned hydrological and water quality data from the Shen–Guan cross-section (shown in Figure 1a), recorded during the rainfall series from 14 to 20 June, 2025, were used for the validation. As reported, an NSE value over 0.75 is considered as satisfactory model performance [38], and a low MSE value approaching zero indicates high predictive consistency. As shown in Figure 4, a remarkable agreement was achieved between the simulated and the measured data of flow after model parameter calibration, with NSE and MSE values of 0.812 and 0.305, respectively. In Figure 4, the predicted rainfall-driven flow profile accurately captured the overall varying trend of the measured data, especially the moment and the magnitude of the major peaks. Figure 5 presents the model validation results of four water quality parameters, with all NSE values over 0.85 and low MSE values, demonstrating a high degree of model accuracy. The results indicated a successful calibration and validation, and the calibrated model framework was used in all simulations shown in the followed-up sections.

Figure 4.

Rainfall-driven flow results of the calibrated and validated coupled model and the observation at the Shen–Guan cross-section.

Figure 5.

Concentration variations of (a) chemical oxygen demand (COD), (b) total phosphorus (TP), (c) ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N), and (d) total nitrogen (TN) of the calibrated and validated coupled model and observation at the Shen–Guan cross-section, driven by the same rainfall series as Figure 4.

3.2. Rainfall-Driven Runoff and Pollutant Generation Transfer Processes in a Specific Rainfall Event

3.2.1. Surface Runoff Generation Transfer Within the Watershed

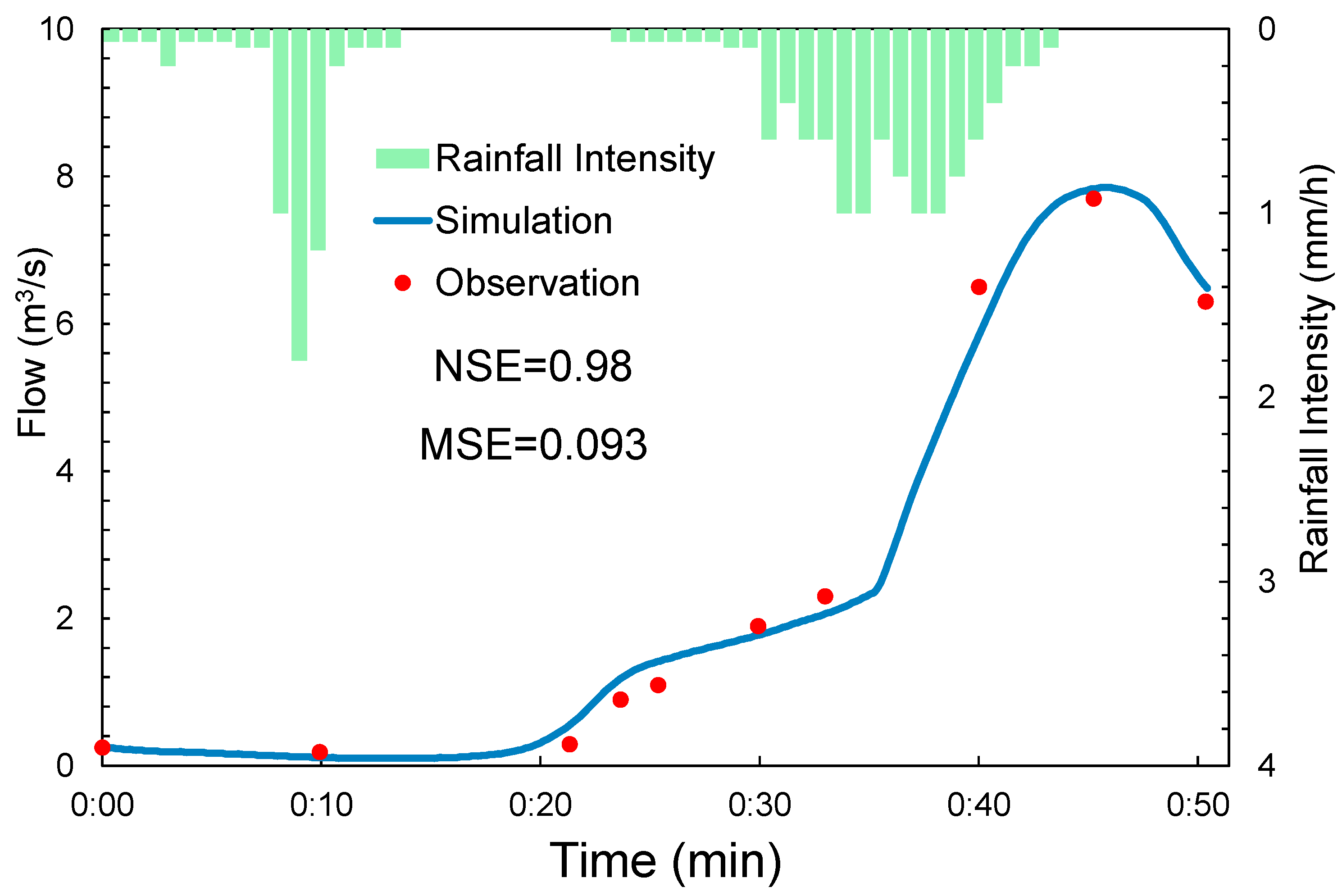

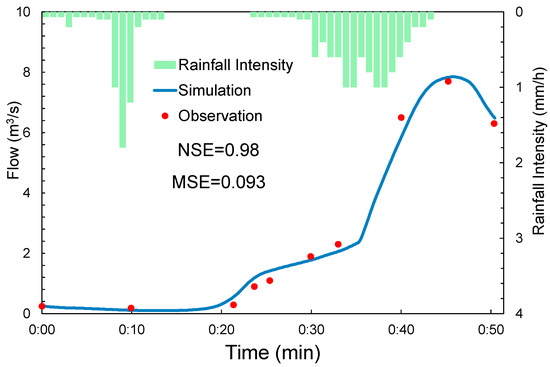

In order to assess the contribution from individual sub-catchments to flooding and NPS pollution in the whole watershed, the coupled model with optimization was applied to simulate one single rainfall event on 7 March 2021. The rainfall-driven runoff process was assessed first. As shown in Figure 6, an excellent agreement was achieved between the simulated and observed flow data, with NSE of 0.98 and MSE of 0.093, indicating satisfactory performance of the coupled model to simulate more rainfall event than the ones for validation in Section 3.1.

Figure 6.

Flow variation of the calibrated and validated coupled model and the observed data at the Shen–Guan cross-section, driven by one single rainfall event.

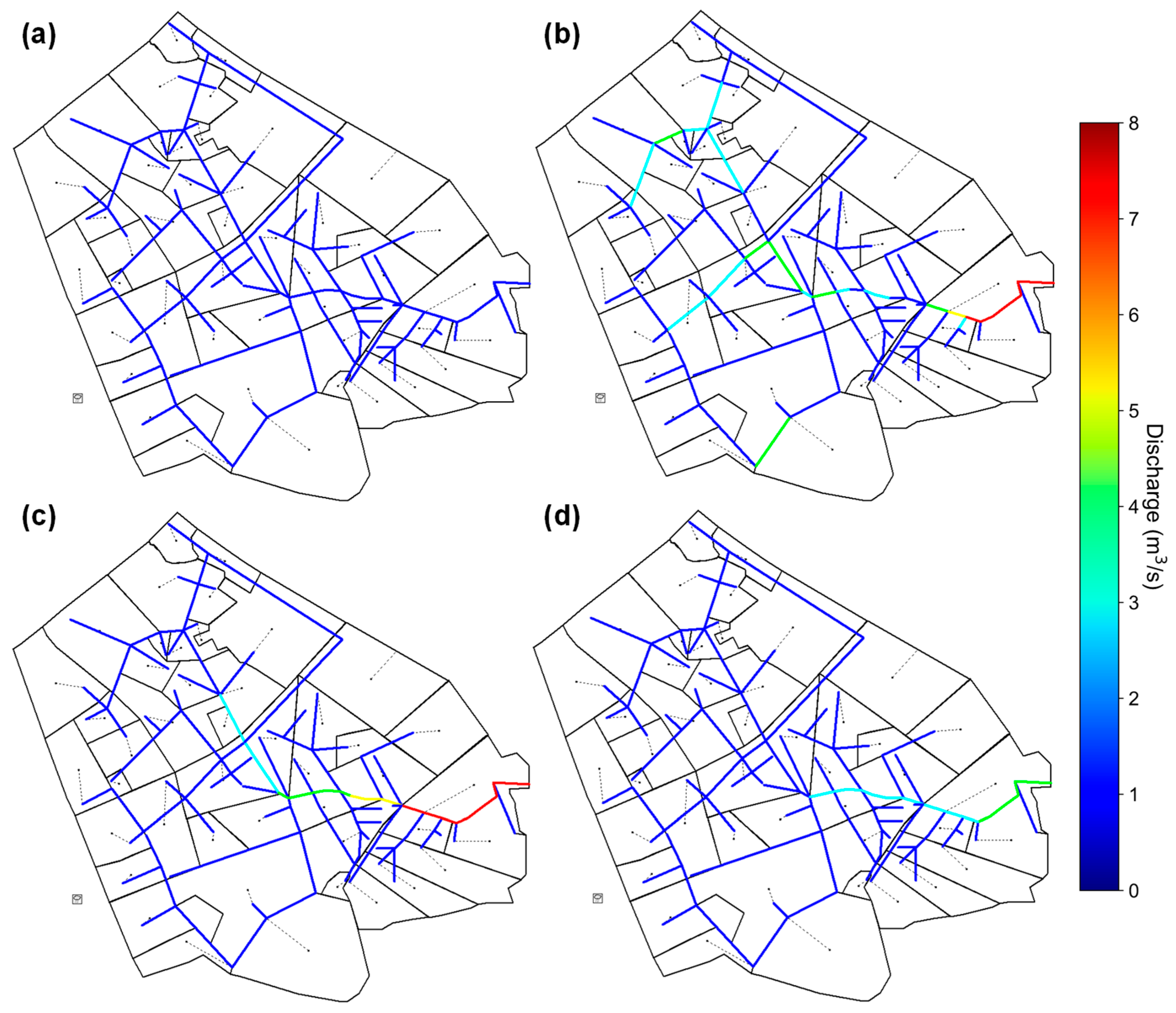

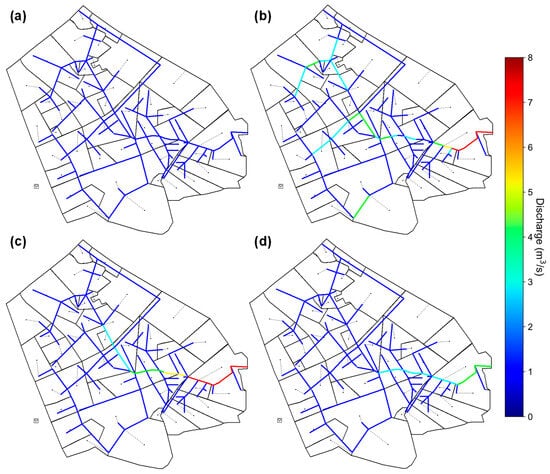

Figure 7 illustrates the simulated discharge response of all sub-catchments to the recorded rainfall event, in which four representative moments are selected. In the early stage of the rainfall (middle time of the rainfall, Figure 7a), although the discharge had the first increase phase (Figure 6), flows across the whole watershed still remained below 2 m3/s, indicating that effective runoff generation had not yet begun. When the peak shown in Figure 6 arrived (end of the rainfall, Figure 7b), considerable increase in discharge was observed in the main channel and some branches, especially the discharge of the last part of the downstream main channel which rose sharply to 6–8 m3/s, demonstrating the rainfall’s strong hydrologic influence. When the second peak (not shown in Figure 6, 21 min after the rainfall ended) visited the Shen–Guan cross-section, the area with high discharge values (red in Figure 7c) in the downstream main channel was even larger, but no more discharge increase was found in the upstream regions. For the rainfall-driven impact towards the end (56 min after the rainfall ended, Figure 7d), the discharge response was only found in the downstream main channel. The results highlighted a considerable time lag between the rainfall and the runoff response. Discharge increase was slow at first, then became steep when the rainfall was going to end, driving the sub-catchments toward saturation, particularly within the main channel network. Hence, under the condition of a durable rainfall, more attention should be paid to the flooding risk in the regions of downstream main channel and some branches.

Figure 7.

Channel flow variations in the Egongling River watershed as the response to a rainfall event at (a) middle time of the rainfall; (b) end of the rainfall; (c) 21 min after the rainfall ended; and (d) 56 min after the rainfall ended.

Moreover, as discharge increased, the impact of rainfall-driven NPS pollutants on water quality was expected to intensify, and contamination risk would rise, particularly during the two flow peak stages. The spatiotemporal dynamics of NPS pollution are discussed in detail in the following section. The flow variation pattern obtained here also has a good agreement with some previous modeling work on urban watersheds [11,39]. Nonetheless, differences are still found in specific response modes and peak discharges within certain zones, which may result from specified regional rainfall characteristics, land use heterogeneity, and hydrologic model parameterization.

3.2.2. NPS Pollutant Transport and Dispersion in the Watershed and Main Channel

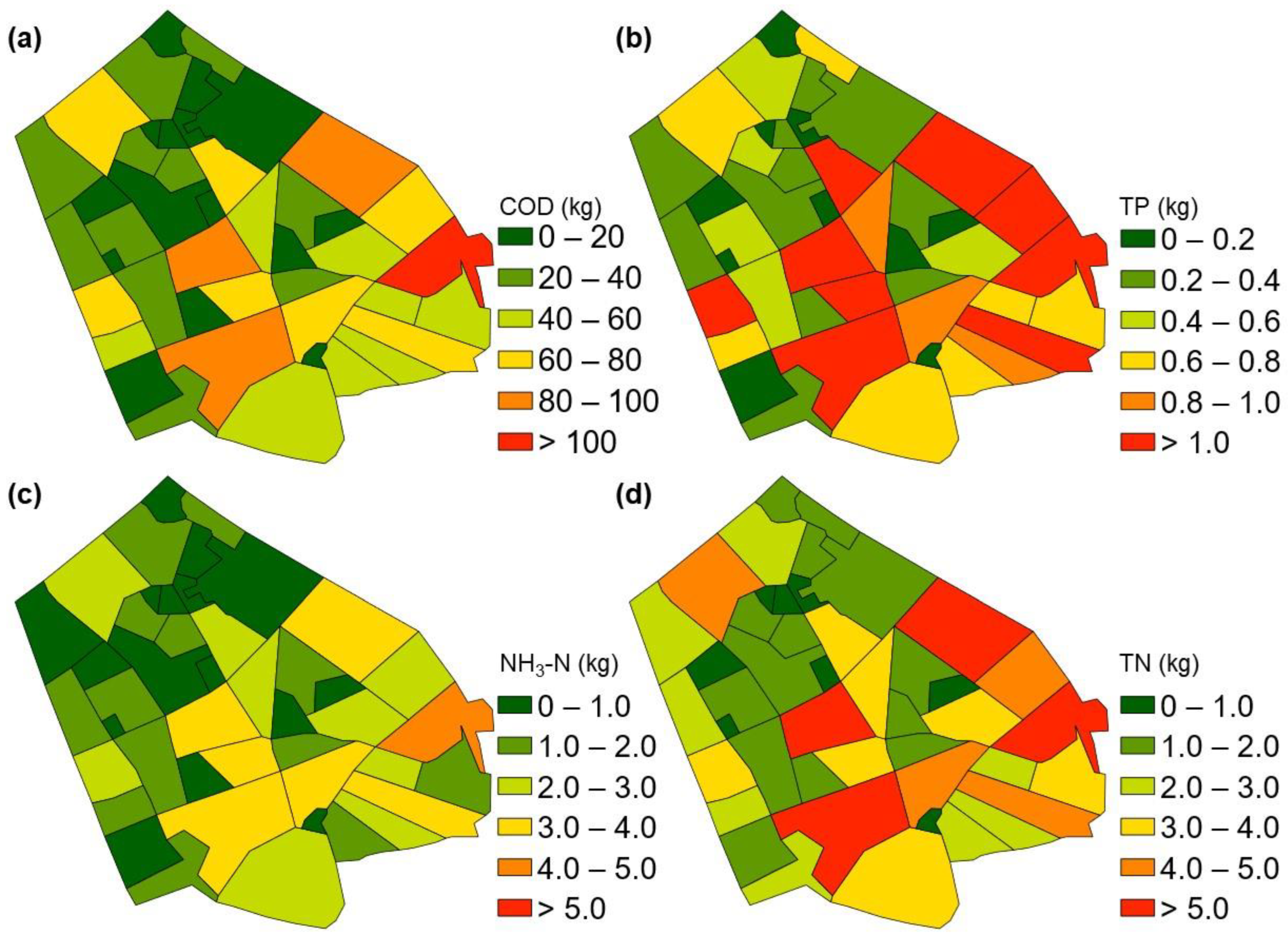

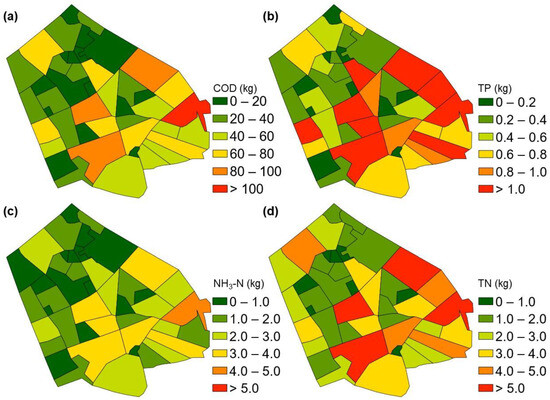

The NPS pollution correlated with the hydrologic response in the recorded rainfall event and was assessed using the total load distribution of the four NPS pollutants (COD, TP, NH3-N, and TN) in the whole watershed. As shown in Figure 8a, highly heterogeneous spatial distribution of the COD load was found, with large differences in magnitude: some sub-catchments had load values below 20 kg, while four had load values over 80 kg, with one even over 100 kg. The relatively low COD load sub-catchments (in green and dark green) were mainly located in the upstream regions, and the relatively high COD load sub-catchments (in yellow, orange and red) were mainly located in the middle- and downstream regions. Similar load distribution patterns were found in the results of TP, NH3-N, and TN, which are shown in Figure 8b, Figure 8c, and Figure 8d, respectively. However, some differences were observed in the overall load level. The overall load level of NH3-N was the lowest, TP was the highest, and TN was higher than COD. Although with some differences in color, the highest load levels of all pollutants are located in the same four sub-catchments, which were in red in the TN map, and the one with top value was in red in the COD map.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of total NPS pollution load during the whole rainfall event within the Egongling River watershed: (a) COD; (b) TP; (c) NH3-N; and (d) TN.

It should be noticed that the ratios of residential and greenland zones were larger in the upstream regions and the industrial zones mainly in the middle- and downstream regions. Hence, the pollutant load distribution considerably correlated with the land use type, especially the four sub-catchments with the highest load levels, which were all attributed to the industrial land use. Thus, the industrial regions accounted for the major contribution to the NPS pollution in the recorded rainfall event. Moreover, the range differences among the four pollutants set in Figure 8 were proportional to the corresponding differences in the national water quality standard. It means that TP should be concerned first in a rainfall event, since its concentration would be highly possibly the first over the standard threshold. The differences between Figure 8c,d also indicated that the ratio of NH3-N to TN was smaller in many industrial sub-catchments, indicating high risk that TN concentration could be over the standard threshold even if NH3-N is still below. Thus, more attention needs to be paid to TN control in these regions as well.

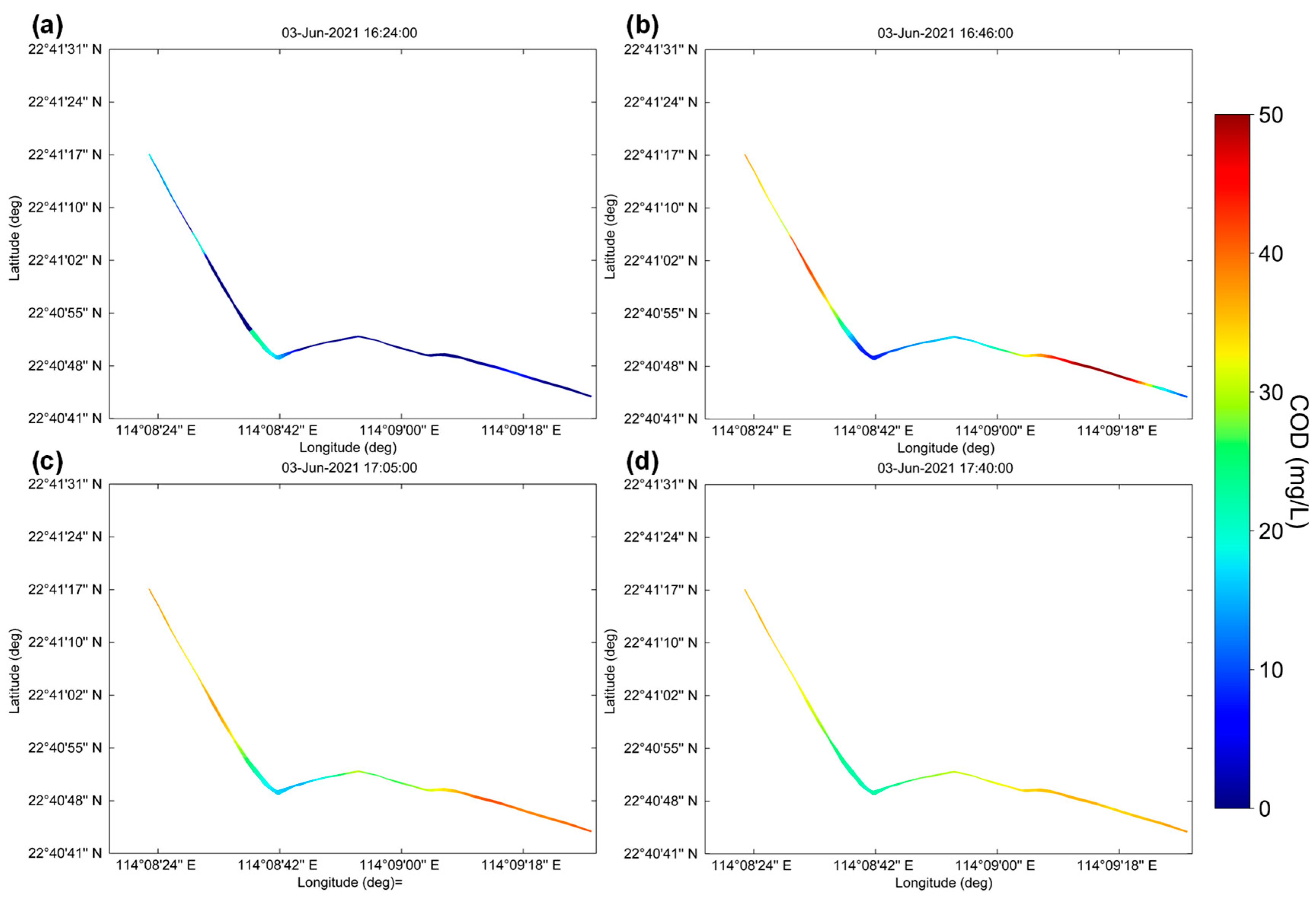

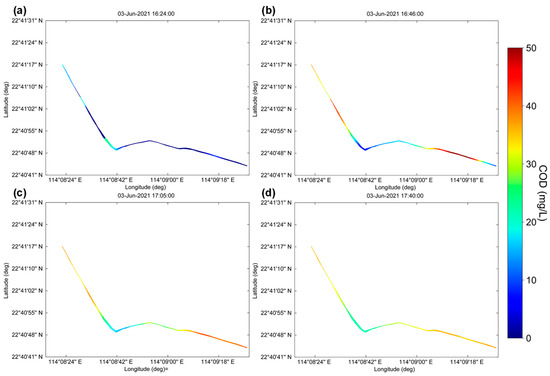

During a rainfall event, the pollutants accumulated from the impervious surfaces in a sub-catchment were washed out, moved together with the rainfall-driven runoff, and then entered the main channel. The NPS pollution loads generated in all sub-catchments eventually transferred and concentrated in the main channel, which would lead to considerable contamination stress on the local aquatic ecosystem. Figure 7 shows the large discharge changes in the main channel, but the details were limited. To further reveal the NPS pollution response to the recorded rainfall event, high-resolution characterization of the pollutant transfer process in the main channel was implemented based on the coupled Delft3D model. Figure 9 shows the detailed COD concentration distribution in the main channel, and the four moments are consistent with Figure 7. In the early stage, increased COD concentration was observed in a few upstream locations (Figure 9a). When the first discharge peak visited the Shen–Guan cross-section (Figure 9b), the COD peak (in red) was also arriving, and another peak was formed upstream. Similarly, the second COD peak was also arriving when the second discharge peak hit the cross-section, with a lower peak value (Figure 9c). In the end stage (Figure 9d), the distribution pattern was similar to Figure 9c, but the COD concentration values were lower, as the discharge was decaying. In addition, in Figure 9d, one peak was still formed in the upstream, meaning that pollutant transfer was not ending yet. However, the rainfall-driven runoff was almost gone, so the mass flux was so small that it could be negligible. The corresponding results of TP, NH3-N, and TN had almost the same trends to COD, which are not shown here. More discussion on the pollutant flux variation in the main channel is addressed in Section 3.3.

Figure 9.

The COD transfer along the Egongling River main channel at following moments: (a) middle time of the rainfall; (b) end of the rainfall; (c) 21 min after the rainfall ended; and (d) 56 min after the rainfall ended.

The aforementioned results indicated a high correlation between the variations of discharge and pollutants, since the peak time was almost overlapped. The two peak zones (in red) in Figure 9b also agreed with the discharge distribution in Figure 7b, since the magnitude of the upstream peak zone was lower than the downstream. Furthermore, the upstream peak zone became much larger when moving to the Shen–Guan cross-section, while the peak value did not decrease (Figure 9c). This change indicated that the peak kept growing when going forward. On the one hand, it moved by convection and diffusion and absorbed pollutants from the branches nearby entering the main channel; on the other hand, a sharp turn, located around 1515 m from the channel’s starting point with considerable changes in flow direction and channel width (shown in Figure 3), led to slow down the flow and thus delayed the pollutants’ motion downward with some local accumulation. Hence, the coupled Delft3D model results highlighted the considerable hydrodynamic impact on the pollutant transfer, and the expansion of the pollutant peak zone when moving downward should be a concern for NPS pollution control in the main channel.

3.3. Assessment on Hydrologic and NPS Pollution Impacts Under More Rainfall Intensity Conditions

It should be noted that the recorded rainfall was light, which may only drive part of the NPS pollution load within the watershed. To assess the NPS pollution behavior under heavier rainfall conditions, two more rainfall intensity scenarios were simulated, for which the cumulative precipitations in the same time were 21.2 mm (moderate) and 31.2 mm (heavy), respectively. The Shen–Guan cross-section was still monitored, since the hydrologic and pollution responses at this location can reflect the contributions from all sub-catchments in the watershed. Furthermore, one middle-point cross-section (also shown in Figure 1a) was selected to assess the hydrologic and pollution behavior of the upstream regions, quite near the aforementioned sharp turn.

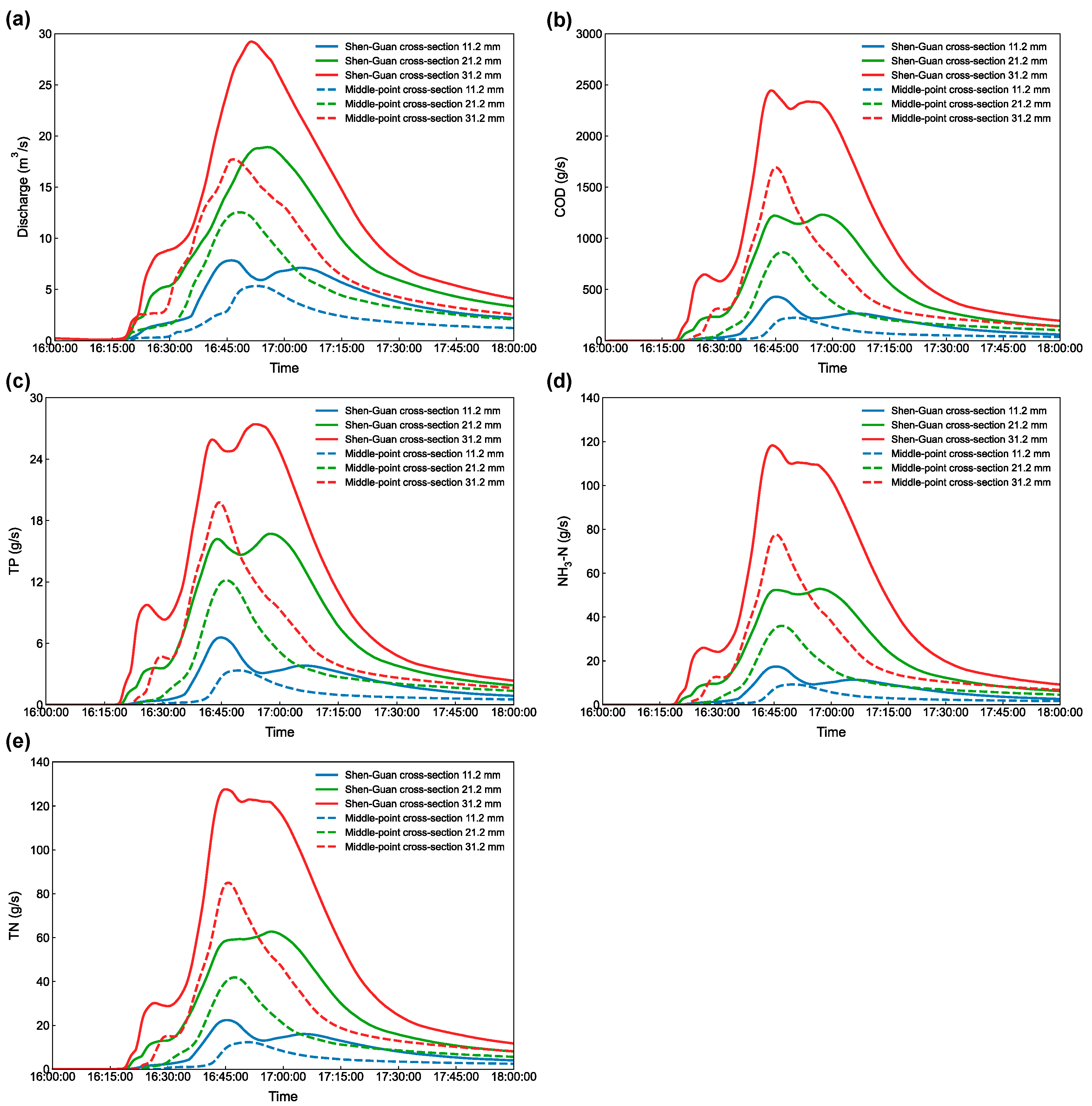

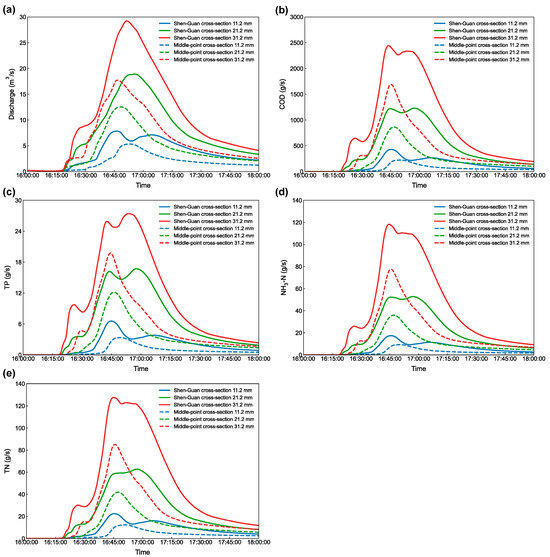

Figure 10a depicts the discharge variation at the two cross-sections. At the middle-point cross-section, the discharge was found to increase to a small plateau, then form one large peak, and finally gradually decrease to the end under the light rainfall event (11.2 mm). However, in the moderate rainfall scenario (21.2 mm), no plateau was observed, and the discharge increased sharply to form the peak, which was larger and occurred earlier than the 11.2 mm scenario. Although a small plateau was observed, the heavy rainfall scenario (31.2 mm) had a similar profile to the 21.2 mm scenario, with a larger and earlier peak. The results indicated that the cross-section received the runoff from the nearby sub-catchments first, then much more runoff from the other upstream sub-catchments to form a peak. As the rainfall intensity increased, the formed peak not only became larger but also hit the cross-section earlier, revealing stronger hydrologic responses. Regarding the Shen–Guan cross-section, in the 11.2 mm scenario, the discharge curve with two peaks has been analyzed in detail in Section 3.2. However, the moderate rainfall scenario (21.2 mm) only had one major peak, with a much larger value of 19 m3/s, while a later time of 55 min. The heavy rainfall scenario (31.2 mm) also had one major peak, for which the value further increased to 29 m3/s. However, the peak time had no further delay and was comparable to the 21.2 mm scenario. The results indicated that in the light rainfall scenario, the hydrologic responses of the sub-catchments from upstream and downstream were clearly reflected by forming two separate discharge peaks in the main channel, with the second peak occurring after the rainfall ended. As the rainfall intensity increased to moderate, these region-dependent responses seem no longer clear, and more runoff generated from the whole watershed mainly formed one peak, with a much larger magnitude and longer time visiting the end of the main channel. However, the peak time was no longer delayed under the heavy rainfall condition. It may be due to that the urban drainage system was rapidly overwhelmed with infiltration capacity nearly saturated, and the additional rainfall was converted almost instantaneously to surface runoff. Hence, the peak was formed when the rainfall was still in progress rather than after it ended, which is an agreement with the previous research [40].

Figure 10.

Temporal variations of (a) discharge; (b) COD; (c) TP; (d) NH3-N; and (e) TN flux at the middle-point and the Shen–Guan cross-sections under the three rainfall intensity scenarios.

Figure 10b–e illustrate the time-varying pollutant flux results under the three rainfall intensity scenarios at the two cross-sections. Regarding the COD flux variation at the middle-point cross-section, unlike the discharge curve, no plateau was found before the peak arrived in the 11.2 mm scenario, and the peak time was a little (about 4 min) earlier than the discharge. As the rainfall intensity increased to 21.2 mm, faster pollution responses were found, since the starting moment of the COD flux increase and the peak time were both earlier. In the 31.2 mm scenario, the COD flux increased to form a small peak first; however, the starting and major peak time were almost the same as the 21.2 mm scenario. The flux curves of TP, NH3-N, and TN had similar varying trends to COD. At the Shen–Guan cross-section, in the 11.2 mm scenario, as discussed in Section 3.2.2, the four pollutant curves had a ‘two-peak’ trend similar to the discharge curve. However, the trend consistency was no longer found as the rainfall intensity increased to 21.2 mm: the COD flux first increased to a small plateau, then sharply increased to form two peaks before finally decreasing. This trend was different from the corresponding discharge curve with only one peak (Figure 10a), and neither peak time was matched. In the 31.2 mm scenario, the first plateau part became a small peak; thus, three peaks were formed in the COD flux curve. The general curve patterns of TP, NH3-N, and TN flux were similar to the COD case, although some details were different.

The aforementioned results demonstrate considerable impacts from rainfall intensity and sub-catchment location on the hydrologic and NPS pollution responses. In the light rainfall scenario, the discharge and the pollutant flux curves had similar trends, with the same peak number and coupled peak time. However, in the moderate and heavy rainfall scenarios, different trends were found between the discharge and the pollutant flux curves, with more peaks and decoupled peak time in the pollutant flux curves. It should be noted that the increase ratios of discharge for the 21.2 mm and 31.2 mm scenarios to the 11.2 mm scenario were 207% and 302%, respectively; however, the corresponding mean increase ratios for the four pollutant loads were 322% (±21%) and 596% (±83%), respectively. These large differences revealed that many more pollutants were rushed out from the sub-catchments in intense rainfall events. The large amount of the first-flush pollutants from the nearest sub-catchment entered into the main channel, resulting in the extra small peak formed in an early stage in the 31.2 mm scenario. Moreover, the increased amount of pollutants from the downstream sub-catchments was large enough to form another major peak at the Shen–Guan cross-section, which was comparable to the peak formed upstream (i.e., the peak at the middle-point cross-section). It should be noted that the middle-point cross-section received the runoff generated from 71% of the whole watershed’s area. However, the relevant NPS pollution contribution was just comparable to the contribution from the downstream regions with only 29% area, where industrial land distribution was denser.

Therefore, the measures to effectively control flooding and NPS pollution in a rainfall event should be made based on considerations of both rainfall intensity and spatial heterogeneity. Under a light rainfall condition, focus could be mainly on the coupled peak stage of the discharge and pollutant flux. Under an intense rainfall condition, the pollution issue should be concerned earlier than flooding: the amount of pollutants from first flush would increase sharply, and the resulting local NPS pollution would become much more severe than flooding. Particular concern should be addressed to locations with dense industrial land distribution, especially the downstream regions. In addition, the sharp turn region with enlarged width (Figure 3) should also be focused, where the slow-down flow could lead to concentrated local pollutant distribution.

4. Management Implications and Decision Support

4.1. Risk-Based Spatial Prioritization Framework

The coupled SWMM–Delft3D model’s identification of heterogeneous pollutant distributions across land use categories enables the establishment of a tiered intervention protocol. We recommend implementing a watershed zoning system where management intensity corresponds to modeled pollution contribution coefficients. Specifically, industrial-dominated sub-catchments exhibiting elevated pollutant export rates (as quantified through our spatial analysis) should receive priority allocation of control infrastructure. This approach optimizes resource deployment by concentrating interventions where marginal pollution reduction benefits are maximized.

4.2. Event-Responsive Management Protocols

Based on empirical observations revealing asymmetric escalation of contaminant burdens compared to volumetric discharge during high-intensity rainfall episodes (322–596% versus 207–302% augmentation), precipitation-tiered management frameworks become imperative. This study advocates for implementing operational criteria correlated with predicted rainfall magnitude: during moderate-intensity occurrences (<25 mm/6 h), immediate-deployment source containment protocols should prioritize initial runoff interception within the first 30–45 min window, whereas severe precipitation episodes (>50 mm/6 h) require activation of strategically positioned treatment configurations that integrate hydraulic rerouting, interim containment facilities, and subsequent restoration protocols.

4.3. Targeted Measures for Industrial Districts

The established linkage between manufacturing land utilization and contaminant generation warrants implementation of stringent source mitigation requirements within industrial sectors. Essential measures encompass compulsory deployment of sheltered raw material storage facilities, intensification of sweeping schedules in advance of predicted meteorological events, and deployment of continuous monitoring infrastructure at strategic outfall locations. High-granularity modeling outputs facilitate strategic sensor positioning for anticipatory alert mechanisms.

4.4. Adaptive Infrastructure Design Parameters

Empirical evidence indicates that traditional engineering criteria fail to accommodate non-linear contaminant mobilization patterns across diverse precipitation regimes. Infrastructure dimensioning standards require reconfiguration to integrate pollutant reduction performance indicators beyond conventional hydraulic conveyance parameters. Retention structures necessitate dual-function optimization approaches that simultaneously address peak flow mitigation and contaminant mass abatement objectives, calibrated against event-specific loading projections generated through predictive modeling.

5. Conclusions

This study developed a coupled SWMM–Delft3D model framework to characterize the hydrologic and NPS pollution responses to rainfall events with different precipitation intensities in the Egongling River watershed in Shenzhen, one of the most representative cities undergoing rapid urbanization in China. The coupled model achieved excellent agreements with both the observed hydrological (NSE = 0.812; MSE = 0.305) and water quality (NSE > 0.85) data and demonstrated high-resolution dynamic changes in flow and pollutant transfer within the studied watershed, with highly heterogeneous spatial distributions of discharge and pollutant loads. Moreover, the temporal change patterns in discharge and pollutant flux in the main channel considerably differed with rainfall intensity, which highly correlated in a light rainfall scenario but decoupled under more intense rainfall conditions. As rainfall intensity increased, the increase in pollutant loads (mean 322% and 596%, respectively) was much larger than the increase in discharge (207% and 302%, respectively), indicating a substantial amount of local accumulative NPS pollutants rushed out by the strengthened runoff. The pollutant flux variation was also dependent on land use type heterogeneity, since more severe NPS pollution was found in locations with concentrated industrial land distribution, especially the downstream regions. Hence, strategies to effectively control flooding and NPS pollution should be specified based on both rainfall intensity and spatial heterogeneity of land use. This study also provides substantial method and data support for further decision-making on sponge-city construction and smart control of flood and NPS pollution.

Furthermore, some perspectives should be addressed in future work. First, the validation period was temporally constrained, which may not fully capture long-term variability or extreme events. Additionally, uncertainties in parameter estimation, particularly in regions with limited data, could affect the model’s predictions. The integration of models at different spatial and temporal scales also posed challenges, potentially limiting further application. Assumptions made in the pollutant buildup and washoff processes, such as simplified representations of land cover and pollutant behavior, still have a distance from fully characterized real-world complexities. Future research should focus on long-term validation studies, refined parameter calibration, and the inclusion of additional environmental factors to enhance model robustness and accuracy. Additionally, the incorporation of pollution control strategies, such as Total Maximum Daily Load measures, could be explored to assess their effectiveness in mitigating water quality issues and optimizing pollutant management in the study area.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/w17213049/s1, Table S1: Summary of data sources and precision; Table S2: Key features of SWMM and Delft3D; Table S3: Egongling River sub-catchment characteristics; Table S4: Initial conditions and boundary conditions of SWMM and Delft3D.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.F., P.W., and W.L.; methodology, G.Y.; formal analysis, H.W., G.Y., W.L., F.S., Z.H., and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, H.W. and G.Y.; writing—review and editing, C.F., P.W., K.L., and Y.P.; supervision, C.F., P.W., K.L., and Y.P.; project administration, C.F.; funding acquisition, C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the PowerChina Core Technology Research Project (grant number DJ-HXGG-2022-09); the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of China (grant number 2023B1515040028); and the National Key R&D Program of China (grant number 2022YFC3002903).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Hantao Wang, Yang Ping, Fangze Shang, Zhiqiang Hou, and Zhenzhou Zhang were employed by the company PowerChina Eco-Environmental Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The authors declare that this study received funding from PowerChina Core Technology. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Deng, O.; Wang, S.; Ran, J.; Huang, S.; Zhang, X.; Duan, J.; Zhang, L.; Xia, Y.; Reis, S.; Xu, J.; et al. Managing urban development could halve nitrogen pollution in China. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guan, Y.; Hu, M.; Hou, Z.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Shang, F.; Lin, K.; Feng, C. Enhancing pollution management in watersheds: A critical review of total maximum daily load (TMDL) implementation. Environ. Res. 2025, 264, 120394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossman, L.; Storm Water Management Model User’s Manual Version 5.2. 2022. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/water-research/storm-water-management-model-swmm (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Yan, X.; Xia, Y.Q.; Ti, C.P.; Shan, J.; Wu, Y.H.; Yan, X.Y. Thirty years of experience in water pollution control in Taihu Lake: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasti, L. Decontamination of Urban Run-Off: Importance and Methods. In Balanced Urban Development: Options and Strategies for Liveable Cities; Maheshwari, B., Thoradeniya, B., Singh, V.P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 85–107. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, F.Z.; Tang, S.J.; Wang, H.T.; Yang, R.Y.; Hou, Z.Q.; Ping, Y.; Zhang, Z.Z.; Chen, H.Y.; Yu, Y.E.; Goonetilleke, A.; et al. Assessing the effectiveness of non-point source pollution models in data-limited urban areas. J. Hydrol. 2025, 661, 133636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M.N., Jr.; do Lago, C.A.F.; Rápalo, L.M.C.; Oliveira, P.T.S.; Giacomoni, M.H.; Mendiondo, E.M. HydroPol2D-Distributed hydrodynamic and water quality model: Challenges and opportunities in poorly-gauged catchments. J. Hydrol. 2023, 625, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.K.; Song, Z.X.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, S.Y.; Zhang, M.J.; Zhang, W.Q.; Xiao, S.R. A review on curbing non-point source pollution in watershed-the answer lies at the root. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Qi, F.; Liu, L.; Chen, M.; Sun, D.; Nan, J. How do urban rainfall-runoff pollution control technologies develop in China? A systematic review based on bibliometric analysis and literature summary. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 789, 148045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisht, D.S.; Chatterjee, C.; Kalakoti, S.; Upadhyay, P.; Sahoo, M.; Panda, A. Modeling urban floods and drainage using SWMM and MIKE URBAN: A case study. Nat. Hazards 2016, 84, 749–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood-Ponce, R.; Diab, G.; Liu, Z.Y.; Blanchette, R.; Hathaway, J.; Khojandi, A. Developing data-driven learning models to predict urban stormwater runoff volume. Urban Water J. 2024, 21, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Olivares, A.; Des, M.; Decastro, M.; Pereira, H.; Picado, A.; Dias, J.M.; Gómez-Gesteira, M. Coupled Hydrodynamic and Biogeochemical Modeling in the Galician Rías Baixas (NW Iberian Peninsula) Using Delft3D: Model Validation and Performance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyappan, K.; Thiruvenkatasamy, K.; Balu, R.; Devendrapandi, G.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Ayyamperumal, R. Numerical model study on stability of a micro-tidal inlet at Muttukadu along the east coast of Bay of Bengal. Environ. Res. 2024, 248, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.; Roy, M.B.; Roy, P.K. Evaluating the performance of MIKE NAM model on rainfall-runoff in lower Gangetic floodplain, West Bengal, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2022, 8, 4001–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.S.M.; Saad, N.A.; Akhir, M.F.M.; Rahim, M.S.A. QUAL2K water quality model: A comprehensive review of its applications, and limitations. Environ. Modell. Softw. 2025, 184, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, C.; Ahirwar, A.; Lohani, A.K.; Singh, H.P. Comparative analysis of HEC-HMS and SWAT hydrological models for simulating the streamflow in sub-humid tropical region in India. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 41182–41196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swilla, L.; Katambara, Z.; Lingwanda, M. Calibration and verification of a hydrological SWMM model for the ungauged Kinyerezi River catchment in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2024, 10, 2803–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Gui, H.J. Comparative assessment of pollution control measures for urban water bodies in urban small catchment by SWMM. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.Z.; Wang, X.L.; Li, S.M.; Dong, G.Y.; Wang, Q.H.; Chen, Y.T.; Xue, S.H. Numerical simulation model of water quality evolution in urban rivers considering adsorption-desorption process of nitrogen and phosphorus in sediments. J. Hydrol. 2024, 636, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.B.; Zhang, W.T.; Wang, Y.T.; Wang, T.W.; Liu, G.L.; Huang, W. Spatial optimization of ecological ditches for non-point source pollutants under urban growth scenarios. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Li, S.; Cui, C.H.; Yang, S.S.; Ding, J.; Wang, G.Y.; Bai, S.W.; Zhao, L.; Cao, G.L.; Ren, N.Q. Runoff control simulation and comprehensive benefit evaluation of low-impact development strategies in a typical cold climate area. Environ. Res. 2022, 206, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.N.; Hui, M.; Qu, H.Z. Design of a 3D Platform for the Evaluation of Water Quality in Urban Rivers Based on a Digital Twin Model. Water 2024, 16, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.F.; Luo, W.; Yao, Z.Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, C.Y.; Lin, K.R. Water Quality Prediction in Urban Waterways Based on Wavelet Packet Denoising and LSTM. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 2399–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacikoc, M.; Dadaser-Celik, F.; Beyhan, M. Modelling Hydrodynamics and Water Quality in a Brackish Water Lake Under Scarce Data Availability-A Case Study at the Bafa Lake, Türkiye. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2025, 236, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APHA. Standard Methods For the Examination of Water and Wastewater, 21st ed.; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, C.; Liang, Z.; Liao, X.; Lin, K.; Zhai, Y.; Liu, G.; Malpei, F.; Hu, A. Microbial Dynamics on Different Microplastics in Coastal Urban Aquatic Ecosystems: The Critical Roles of Extracellular Polymeric Substances. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 10554–10566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan Tanim, A.; Goharian, E. Developing a hybrid modeling and multivariate analysis framework for storm surge and runoff interactions in urban coastal flooding. J. Hydrol. 2020, 595, 125670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.S.; Hu, C.H.; Zhao, C.C.; Sun, Y.; Xie, T.N.; Wang, H.L. Research on Urban Storm Flood Simulation by Coupling K-means Machine Learning Algorithm and GIS Spatial Analysis Technology into SWMM Model. Water Resour. Manag. 2024, 38, 2059–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.R.; Li, M.R.; Lu, Z.M. Assessing runoff control of low impact development in Hong Kong’s dense community with reliable SWMM setup and calibration. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, R.E. Analysis of runoff-plat experiments with varying infiltration-capacity. Eos Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 1939, 20, 693–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-Venant. Theorie du mouvement non-permanent des eaux avec application aux crues des rivers et a l’introduntion des Marees dans leur lit. Acad. Sci. Comptes Redus 1871, 73, 148–154. [Google Scholar]

- Golosov, V.; Konoplev, A.; Wakiyama, Y.; Ivanov, M.; Komissarov, M. Erosion and Redeposition of Sediments and Sediment-Associated Radiocesium on River Floodplains (the Niida River Basin and the Abukuma River as an Example). In Behavior of Radionuclides in the Environment III: Fukushima; Nanba, K., Konoplev, A., Wada, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 97–133. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Q.; Qiao, W.B.; Huang, J.F.; Li, H.Y.; Wang, X. Impact and analysis of urban water system connectivity project on regional water environment based on Storm Water Management Model (SWMM). J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 423, 138840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Sperling, M.; de Paoli, A.C. First-order COD decay coefficients associated with different hydraulic models applied to planted and unplanted horizontal subsurface-flow constructed wetlands. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 57, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.K.; Zhang, B.; Mu, C.; Chen, L. Simulation of the hydrological and environmental effects of a sponge city based on MIKE FLOOD. Environ. Earth Sci. 2018, 77, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.X.; Yin, H.L.; Yao, Y.J. Prediction of Water Quality of Huangpu River Using a Tidal River Network Model. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2008, 25, 1463–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navier, C. Memoire sur les lois du Mouvement des Fluides. Mem. Acad. R. Sci. Inst. Fr. 1823, 73, 389–440. [Google Scholar]

- Melsen, L.A.; Puy, A.; Torfs, P.; Saltelli, A. The rise of the Nash-Sutcliffe efficiency in hydrology. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2025, 70, 1248–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.X.; Liu, J.H.; Feng, Y.C.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Li, C.H. An intelligent SWMM calibration method and identification of urban runoff generation patterns. Front. Environ. Sci. 2025, 13, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Liu, B.Y.; Lei, T.J.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.J.; Guo, R.; Chen, D.; Zhou, K.; Li, S.S.; Gao, X. Exploring how economic level drives urban flood risk. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).