Abstract

Urban flooding has significantly impacted the livelihoods of households and communities worldwide. It highlights the urgency of focusing on both flood preparedness and adaptation strategies to understand the community’s perception and adaptive capacity. This study investigates the levels of risk perception, flood preparedness, and adaptive capacity, while also exploring the inter-relationships among these factors within the context of urban flooding in Malaysia. A quantitative approach was employed, involving a structured questionnaire administered to residents in flood-prone urban areas across Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. A total of 212 responses were analysed using descriptive statistics, categorical index classification, and Spearman correlation analysis. The findings indicate that residents generally reported high levels of risk perception and preparedness, although adaptive capacity exhibited greater variability, with a mean score of 3.97 (SD = 0.64). Positive associations were found among risk perception, flood preparedness, and adaptive capacity. This study contributes to the existing knowledge by providing evidence on community resilience and highlighting key factors that can guide flood management policies and encourage adaptive planning at the community level.

1. Introduction

Floods, particularly those driven by extreme weather events related to climate change, pose a significant threat to communities around the world. They are among the most destructive natural disasters. Between 2000 and 2019, estimates indicate that economic losses due to floods worldwide reached up to USD 651 billion [1]. In 2023 alone, insured losses from floods worldwide reached USD 14 billion, with urban flooding accounting for approximately USD 13 billion [2], highlighting the ongoing vulnerability to flooding.

The rapid and often unplanned growth of urban areas encroaches upon natural environments and increases the risk of urban flooding, presenting a significant challenge for city residents. Urban floods occur when heavy rainfall exceeds the capacity of drainage systems, leading to the accumulation of surface water. In natural environments, rainwater is typically absorbed by the soil. However, in urban areas, where the ground is largely impervious surface covered with asphalt and concrete, much of the rainfall remains on the surface [3]. This water is directed through drainage systems, which can become overwhelmed during heavy and continuous rainfall, resulting in flooding [3]. In recent years, many major cities, particularly in Asia, have transitioned from simply experiencing waterlogging to facing full-fledged urban flooding [4].

Urban flooding can profoundly interrupt everyday life and cause enduring economic, environmental, and social damage. Economically, these floods can result in significant losses to infrastructure, property, and economic productivity. On a social level, they can result in displacement, fatalities, and serious physical and mental health effects [5].

In addition to their immediate impact, urban floods pose a significant challenge to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). They hinder progress in several critical areas, including SDG 6, which aims to ensure sustainable water management and sanitation for everyone; SDG 11, seeking to create sustainable cities and communities; SDG 11.5, concerning the management of water-related disasters; and SDG 13, focused on climate action.

Despite growing concerns about flooding, floods continue to inflict significant damage globally, even in developed nations that possess more resources, and therefore, there is a critical need to reassess and revise our strategies for managing urban floods [6]. Meanwhile, research indicates that the resilience and adaptive capacity of urban residents, through non-structural strategies, play a crucial role in effectively reducing and managing floods in cities and urban regions [3]. To effectively address the increasing threat of urban flooding and make progress toward the SDGs, it is crucial to enhance the adaptive capacity of city dwellers. A study by Rana et al. (2020) [7] highlights that understanding the key determinants of risk perception, preparedness, and adaptation measures is crucial for informing policy development and guiding priority actions for extreme urban flooding, which has become a serious threat to urban areas.

Enhancing adaptive capacity involves more than just raising awareness or updating infrastructure; it requires cultivating a culture of resilience at both the institutional and community levels [8]. This means adopting a holistic approach that engages the community, reforms our institutions, and implements flexible strategies that can adapt over time to address future vulnerabilities. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, only a few studies have systematically quantified adaptive capacity and identified the key factors that drive effective flood adaptation in urban areas. In addition, there is often a lack of connection between the community’s preparedness and their risk perception and adaptive capacity. While the SDGS emphasise climate resilience and disaster risk reduction, there remains a lack of integrated approaches that connect adaptive capacity assessments with communities’ flood preparedness and risk perception for effective flood resilience strategies.

This study examines the perspectives of communities residing in urban areas vulnerable to flooding, with a focus on their capacity to adapt to increasing flood risks. It aims to fill existing gaps by empirically analysing the relationships among preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity at the community level, specifically considering the increasing risks associated with urban flooding. By adopting a people-centred approach, this study examines community preparedness behaviours, explores risk perception dynamics, and identifies the critical factors that influence adaptive capacity. Specifically, this study analyses how risk perception and flood preparedness shape the adaptive capacity of urban residents in response to recurrent flood events. The findings aim to support the development of targeted strategies to strengthen adaptive capacity and promote sustainable flood resilience, particularly in vulnerable urban environments. This study addresses two primary questions: (1) What are the levels of residents’ preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity in responding to potential future floods in flood-prone urban areas? and (2) how are flood preparedness and risk perception associated with the adaptive capacity?

This study aligns with the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030, emphasising the importance of understanding disaster risks, improving preparedness, and building community resilience. The framework advocates for risk mitigation, the prevention of new hazards, and the strengthening of capacity to respond to and recover from disasters. Ultimately, a truly resilient community can endure crises, recover effectively, and adapt to future climate challenges.

To conceptually support this study, we draw upon Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), introduced by Roger in 1975, which outlines two key cognitive processes: threat appraisal, which involves evaluating seriousness and personal vulnerability to a risk, and coping appraisal, which assesses one’s ability to manage that risk through factors such as self-efficacy, response efficacy, and perceived costs [9]. These appraisals influence protection motivation, which in turn affects the likelihood of engaging in adaptive or preparatory actions. PMT complements efforts to understand how risk perception and coping capacity contribute to community preparedness and long-term resilience.

1.1. Strengthening Flood Risk Perception and Preparedness

Preparedness for urban flooding requires more than just emergency responses, as it calls for long-term, proactive planning that enables communities to anticipate, endure, and recover from flooding incidents. Studies consistently show that inadequate preparedness mechanisms significantly weaken community resilience [10,11,12]. Traditional approaches often focus on infrastructure and awareness, while recent research highlights that effective preparedness is also profoundly influenced by socio-cultural dynamics, including local values, risk perception, and patterns of community engagement [11].

The concept of “Everyday Life Preparedness” in Kitagawa’s (2019) [13] study offers an insightful perspective from Japan, illustrating how flood preparedness can be integrated into daily routines. The term “everyday” does not mean that individuals actively think about or engage in disaster preparedness every day. Instead, it suggests incorporating preparedness-related thoughts and activities into everyday life without specifically labelling them as disaster preparedness. In this approach, social capital, self-efficacy, and habitual practices emerge as critical enablers for maintaining preparedness over time [13,14].

Effective preparedness strategies should reflect cultural realities, address local misconceptions, and involve inclusive planning [11]. Citizens are more likely to engage in preparedness efforts when these initiatives align with their lived experiences and everyday values [14]. In this context, adaptive capacity becomes not just a response mechanism but a proactive driver of preparedness. Pala et al. (2025) [12] argue that limited adaptive capacity, particularly among socioeconomically marginalised groups, increases vulnerability and hinders preparedness efforts. Adaptive capacity is influenced not only by infrastructure but also by public trust, awareness, and collective ability to convert risk perception into action [10]. Thus, adaptive capacity is the crucial bridge between awareness and behavioural response, enabling communities to learn, innovate, and adjust to changing flood dynamics. Enhancing flood preparedness requires integrated approaches that strengthen adaptive capacity at the individual, community, and institutional levels, thereby laying the foundation for inclusive, long-term urban resilience.

In addition, risk perception plays a crucial role in shaping how individuals respond to floods [15]. It influences preparedness and adaptive capacity and affects emotional and problem-solving coping strategies [16]. Recent empirical research indicates that many residents underestimate their vulnerability to flood risks, often believing their risk levels will remain constant over time. While prior experiences with flooding can increase awareness of these risks, they do not always lead to proactive protective behaviours. This issue is referred to as the risk perception paradox, where individuals recognise potential threats but fail to take preventive measures [15,16].

A study from Croatia [16] reveals that public awareness of flood risks is moderate, yet levels of preparedness are low, highlighting a disconnect between perception and action. Socioeconomic factors such as age, education, and past experiences with flooding influence awareness. However, many individuals perceive the risk to their community as being greater than the risk to themselves, which often results in inaction. This further illustrates the risk perception paradox, as people acknowledge the dangers of flooding but do not implement adequate mitigation measures [16].

Research indicates that emotional responses, such as fear, concern, and anxiety, significantly shape individuals’ perceptions of risk. These perceptions influence how people prepare for and respond to environmental hazards like urban flooding [17]. Perception of flood risk is affected by various factors, including personal experiences, social influences, cognitive biases, and external elements such as media representation and trust in policies [18]. By identifying and understanding these determinants, we can enhance flood preparedness, improve risk communication, and develop more effective adaptation strategies for those most at risk.

The study on Canadian homeowners’ flood risk perception found that many underestimate their actual risk, even in designated high-risk areas [19]. While past flood experiences increase awareness and preparedness, risk perception alone does not strongly motivate protective actions. Instead, homeowners are more likely to adopt flood protection measures if they have personally experienced flooding [19].

1.2. Adaptive Capacity in Flood Management

Adaptive capacity refers to a community’s ability to adjust to climate variability and change, reduce potential damage, and respond effectively to disasters such as floods [20,21]. This capability is especially important for managing floods because it has a direct impact on how effectively communities can prepare for, respond to, and recover from flooding incidents.

Adaptive capacity is frequently discussed in the context of vulnerability and resilience, highlighting its role in reducing risks and improving disaster preparedness. Unlike vulnerability, which is viewed as a negative trait, adaptive capacity is viewed as a positive attribute because it enables communities to manage climate risks effectively [20]. Adaptive capacity is a key concept in both vulnerability and resilience frameworks [21]. It is crucial in determining how communities cope with and adapt to environmental stresses.

According to Ebi et al. (2004) [22], “Adaptive” refers to a property or system that can adjust its characteristics or behaviour to expand its ability to cope with existing climate variability or future climate conditions. Increasing adaptive capacity expands a system’s ability to manage various climate impacts while also allowing for flexibility to adjust strategies if they are found to be on an undesirable path [20]. Adaptive capacity is closely linked to coping mechanisms, the immediate strategies employed to address the effects of a disaster. Although coping mechanisms offer short-term relief, adaptive capacity emphasises sustainable adaptation by incorporating a long-term strategy for building resilience [20].

In addition, resilience and adaptive capacity are intrinsically linked in urban flood management, with adaptive capacity serving as a core determinant of resilience [23]. The same study positions adaptive capacity as a critical element that counteracts vulnerability and significantly mitigates flood risk. Communities and individuals possessing higher adaptive capacity are demonstrably better prepared to withstand, recover from, and adapt to flood events, thereby reducing both immediate impacts and long-term risks. Adaptive capacity is not merely reactive; it is strategic and transformative, shaping the foundation of long-term urban resilience.

1.3. The Growing Importance and Determinants of Adaptive Capacity

Adaptive capacity is a crucial element of climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction, influencing how effectively urban systems can respond to environmental shocks [24]. Several conceptual models have been developed to assess adaptive capacity, each highlighting different dimensions and determinants. One widely used framework is the Adaptive Capacity Wheel by Gupta et al. (2010) [25], which identifies six key dimensions that impact a system’s ability to adapt: variety, learning capacity, room for autonomous change, leadership, availability of resources, and fair governance. This Gupta framework is particularly useful in evaluating community adaptive capacity and shaping how communities prepare for, respond to, and recover from flood risks.

Another necessary approach is the indicator-based model, which evaluates adaptive capacity using quantitative and qualitative indicators such as socioeconomic status, infrastructure quality, institutional effectiveness, and public awareness [26]. A study in Da Nang, Vietnam, identified 17 key indicators, including household wealth, education levels, access to municipal services, and governance effectiveness, as major determinants of urban adaptive capacity [26]. Similarly, a study in the Philippines categorised communities into different adaptive capacity levels based on factors like economic vulnerability, disaster preparedness, and recovery potential [27].

A study by Ro and Garffin (2023) [8] assessed institutional adaptive capacity using the Adaptive Capacity Wheel and found that robust governance structures, proactive planning, and community participation significantly enhance resilience in Seoul. In contrast, Accra, Ghana, faces notable socioeconomic and infrastructural challenges regarding urban flood resilience [28]. A study in the Dome community revealed that low-income households are highly vulnerable due to poor drainage systems, a lack of government assistance, and limited access to flood warning systems. Unlike Seoul, where strong institutions drive adaptation, Accra’s adaptive capacity is hindered by economic inequality and governance inefficiencies. The study emphasised the need for improved disaster relief policies, community-led adaptation measures, and greater investments in urban infrastructure to reduce vulnerabilities [28]. Addressing these challenges requires a data-driven approach to ensure equitable and inclusive flood preparedness strategies tailored to diverse urban contexts.

1.4. Urban Flood Vulnerability in Malaysia

Malaysia is geographically situated in a stable area, away from volcanic eruption zones. Nevertheless, the country still faces challenges related to floods and human-made disasters, such as deforestation and global warming. Rapid urbanisation has led to the development of residential and commercial areas, which have destroyed pervious surfaces like natural ground and open spaces that typically absorb water. This destruction increases surface runoff during heavy rainfall. Scholars have noted that the rapid and extensive urban development in Malaysia has significantly heightened the risk of flash floods, making this issue a critical concern for policymakers, urban planners, and developers [29].

Additionally, inadequate drainage systems are often unable to cope with intense rainfall, resulting in flooding. Changing weather patterns have exacerbated the situation, resulting in more frequent and intense downpours that overwhelm existing drainage systems, leading to urban flooding. Improper disposal of solid waste also contributes to localised flooding. The severe floods that have occurred in Selangor and Kuala Lumpur in recent years have displaced thousands of people and inflicted substantial economic losses, highlighting the acute vulnerability of urban areas to these disasters [29]. The flood event that took place from December 2021 to January 2022 was among the most catastrophic in Malaysia’s history, affecting eight states, with Selangor and Kuala Lumpur facing the most severe impacts. This disaster displaced over 125,000 people, caused more than 50 fatalities, and led to estimated financial losses of MYR 6.1 billion. This amount includes MYR 2 billion for infrastructure damage and MYR 1.6 billion in losses related to residential properties [30]. Notably, the 2021–2022 flood overwhelmed the nation’s flood management systems, highlighting the increasing intensity of extreme rainfall and revealing critical gaps in current mitigation systems. Therefore, there is a pressing need for increased awareness and preparedness regarding the risks of urban flooding, as well as the implementation of effective management and response strategies.

Despite various policies implemented by Malaysia to reduce the impact of flooding, many citizens continue to suffer damage and require government assistance to stay resilient [31]. Another study indicates that most studies in Malaysia have concentrated on the vulnerabilities associated with floods, primarily focusing on their impacts and adaptation strategies in rural areas [32]. However, urban flooding has emerged as an increasingly urgent concern that requires greater attention. Resilience may vary between urban and rural communities due to differences in infrastructure, socioeconomic conditions, and access to resources. Nonetheless, the specific ways that disaster vulnerability affects the resilience of urban communities remain under-researched and poorly understood.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Area

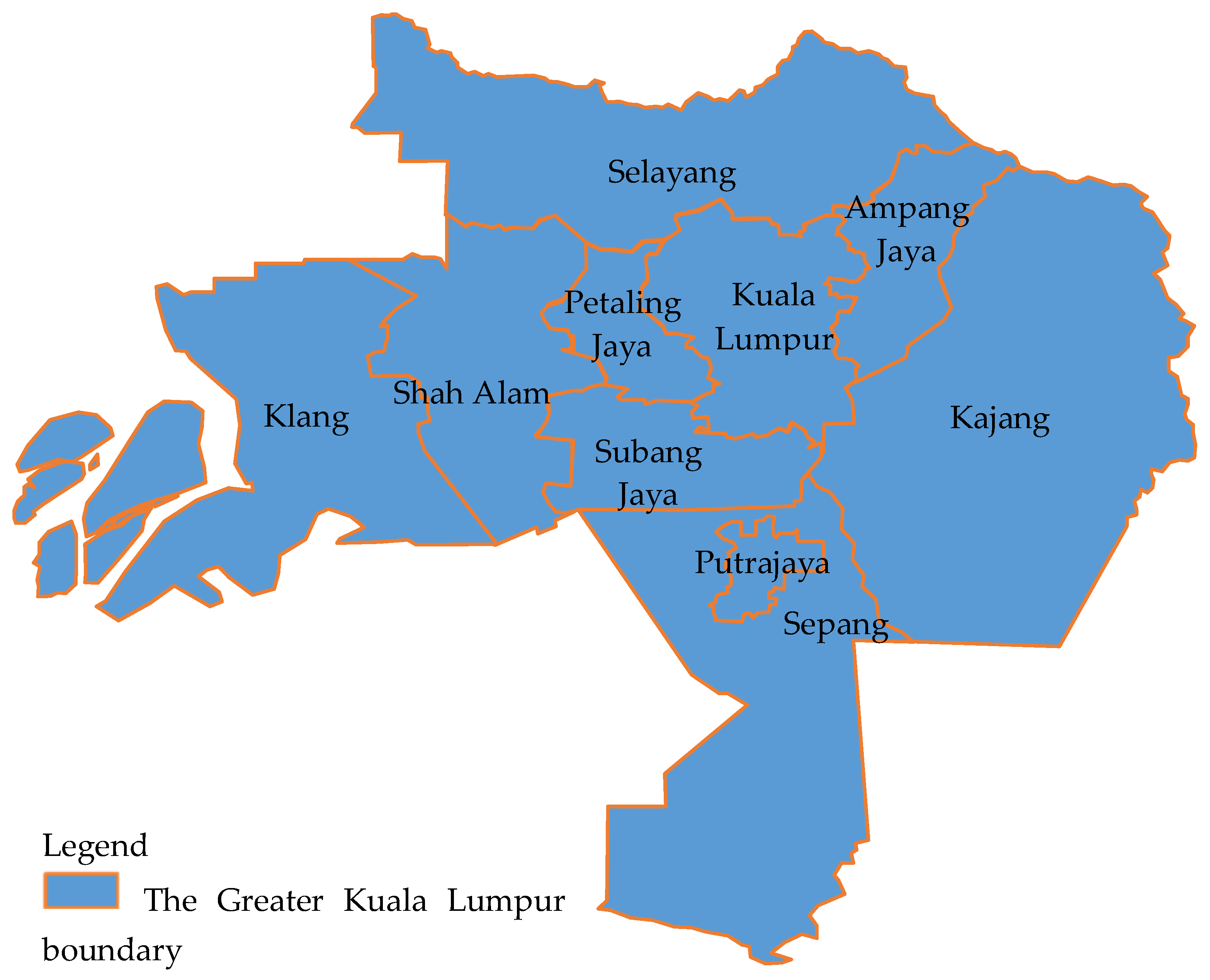

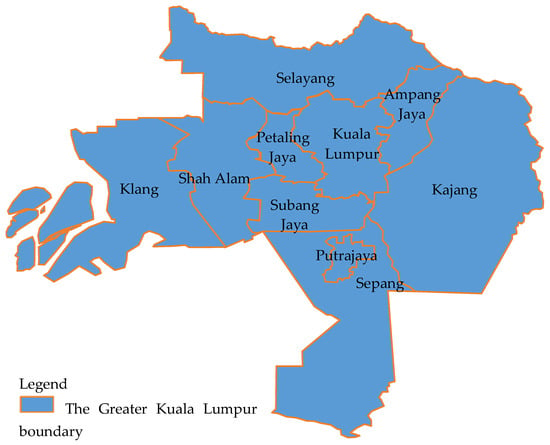

Greater Kuala Lumpur, located in the western part of Peninsular Malaysia, is the country’s most densely populated and urbanised region. It includes the federal territory of Kuala Lumpur and several key districts in Selangor, such as Petaling, Gombak, Hulu Langat, Klang, and parts of Kuala Langat and Sepang [33]. Figure 1 illustrates the spatial extent of Greater Kuala Lumpur.

Figure 1.

The Greater Kuala Lumpur boundaries (Source [33]).

As the economic and administrative centre of Malaysia, Greater Kuala Lumpur has experienced rapid urbanisation, industrial development, and population growth. However, these changes have made the region highly vulnerable to environmental challenges, particularly urban flooding. The extensive built-up areas, combined with inadequate drainage systems and climate variability, have contributed to a rise in frequent and severe flooding events in recent years. Recent statistics further emphasise the vulnerability of these regions. In 2022, Selangor reported significant flood-related losses totalling MYR 95 million. In 2023, losses decreased to MYR 13.91 million but rose again in 2024 to MYR 22.58 million [34]. Similarly, Kuala Lumpur faced considerable economic and infrastructure losses in both years. These recurrent flooding events have become annual challenges, putting immense strain on local resources and recovery efforts. This situation makes Greater Kuala Lumpur a critical case for investigating urban flood resilience and adaptive capacity.

2.2. Survey Instrument

The questionnaire items were derived from well-established scales and the relevant literature to ensure both reliability and validity. It consists of four sections: demographic profile, flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity, with a total of 65 items. The flood preparedness section items were adopted and adapted from Šiljeg et al. (2024) [35]. These items focus on individual responsibility, knowledge, proactive preparedness, financial readiness, and awareness.

For the risk perception section, the authors utilised the scale developed by Rana et al. (2022) [36]. The items address the likelihood of flooding, fear, perceived threats, potential damage, ability to cope, supply interruptions, knowledge, and trust in government.

To conduct a thorough evaluation of adaptive capacity, this study integrates six determinants from Gupta et al. (2010) [25]: learning capacity, fairness and governance, room for autonomous change, leadership, variety, and resources. Additionally, three determinants, social capital, technology, and institutional policies, are adapted from Thanvisitthpon et al. (2020) [3]. The details of the determinants [3,25] are as follows in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of constructs used for adaptive capacity.

This study investigates these nine constructs through a questionnaire consisting of 37 items designed to empirically assess the relevance and impact of adaptive capacity factors on community resilience to urban flooding. The objective is to gather data on how these dimensions interact and influence adaptive capacity and resilience in flood-prone areas.

The survey utilised a Likert scale to assess participants’ preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity, with most responses ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree”. During analysis, these ordinal responses were numerically coded to facilitate statistical analysis. A small number of binary (yes–no) items were included in the survey to capture actions or experiences that required clear and direct responses. This mixed-format approach follows established practices in disaster risk research and aims to enhance the clarity and depth of the data collected [37].

2.3. Pre-Testing Questionnaire

Prior to conducting the survey, it is important to have an expert, or a group of experts, evaluate the questionnaire’s content and structure to establish its content validity. According to Davis (1992) [38], an ideal review panel should include experts familiar with the study’s concepts, theory, or problem, as well as those skilled in instrument design to ensure both structural quality and content validity, with at least two content experts and one expert in instrument construction for optimal results. Consequently, a total of six experts were engaged in this study to validate the questionnaire by reviewing the questionnaire and providing feedback on the relevance and clarity of the statements. Following that, a pretest was conducted in this study to evaluate the appropriateness of the questionnaire for the respondents. The pretest took place from 16 January to 18 January 2025, with five participants from the flood-affected community. Based on the feedback received, some sentences in the questionnaire were refined. Overall, the respondents reported no significant issues with the questionnaire and indicated they understood the questions clearly. The purpose of this evaluation is to address any shortcomings before administering the instrument to respondents, thereby minimising bias [39]. Finally, a pilot study is a smaller version of the main study used to evaluate the study design and research instrument. This study utilised a pilot test with 35 samples, conducted from 27 January to 30 January 2025. The participants included individuals directly or indirectly affected by urban floods in Selangor. Respondents from flood-affected areas were selected with the help of the head of communities (Penghulu) to ensure diverse representation. Additionally, input was gathered from policymakers, NGOs, and community leaders. Improvements were implemented based on the feedback received to ensure the phrasing of the items was precise, concise, and relevant to the Malaysian context.

Cronbach’s alpha, a commonly used coefficient of internal consistency, was employed to assess the reliability of the items within each dimension of preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity. The value of this coefficient should be greater than 0.7 to confirm the reliability of a questionnaire. Items with low intercorrelation were excluded from further analysis. After verifying the reliability of the questionnaire, a final version was prepared for distribution.

2.4. Data Collection

This study was conducted between February 2025 and April 2025. Data collection focused on urban areas in Greater Kuala Lumpur with specific emphasis on areas identified as high flood risk. These areas are based on their history of frequent flooding. A purposive sampling method was employed to identify individuals who have experienced flooding directly or indirectly in Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, with a focus on urban flood-prone areas. This includes individuals who currently reside or have resided in or near flood-prone areas, as well as those who have experienced or witnessed flooding disruptions or have been involved in flood management activities, to ensure a diverse and representative dataset. The data was primarily collected through an online survey distributed to flood victims, residents of flood-prone areas, and community leaders. Additionally, hard copies of the survey were provided for those unable to respond using electronic devices. A total of 212 valid responses were collected and used for the final analysis.

2.5. Analytical Methods

The analytical approach adopted in this study ensured methodological rigour and statistical appropriateness. Instrument reliability and validity were first assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, with values ranging from 0.70 to 0.95 across the three primary constructs: flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity. These values indicate an acceptable to excellent level of internal consistency, confirming that the items reliably measured their intended dimensions.

To determine the suitability of parametric versus non-parametric tests, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was conducted to evaluate the normality of data distribution. All constructs returned p-values below the 0.05 threshold, indicating that the dataset did not meet the assumption of normality. As a result, non-parametric statistical methods were employed throughout the analysis.

Descriptive statistics were applied to demographic data (Section 1), including frequencies, percentages, and visual representations such as charts and tables. This facilitated a comprehensive overview of the socio-demographic composition of the 212 respondents, aiding in the contextualization of the findings.

To further interpret the data, composite mean scores were calculated for each of the three constructs. These scores were used to quantify the respondents’ overall level of flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity. Mean values were then categorised into three levels: low (1.00–2.99), medium (3.00–3.99), and high (4.00–5.00), following established conventions in Likert-scale interpretation.

Flood preparedness and risk perception were measured using single-dimensional Likert-scale items, with results presented as mean scores. In contrast, adaptive capacity was assessed through a multidimensional construct encompassing various indicators such as social capital, governance, technology, and leadership. As a result, it is reported as a composite mean index. This distinction is made to accurately reflect the methodological differences in how each construct was operationalised and analysed.

Spearman’s rho correlation was used for inferential analysis to examine relationships among the three core constructs. This non-parametric method was selected due to its robustness in handling ordinal Likert-scale data and non-normally distributed variables. The test allowed for the assessment of the strength and direction of associations between flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity, providing deeper insights into community-level dynamics in urban flood resilience.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Demographic Insights

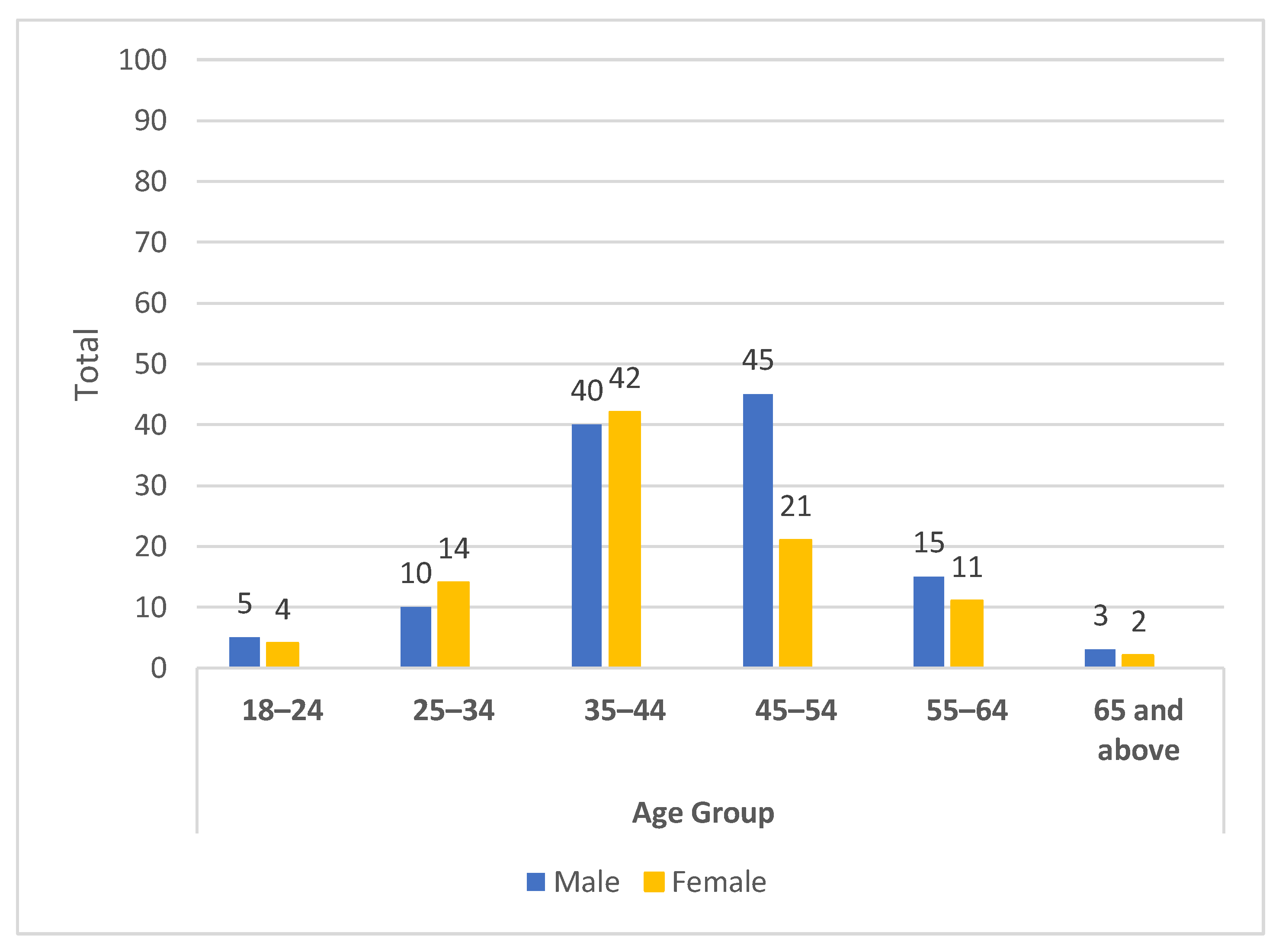

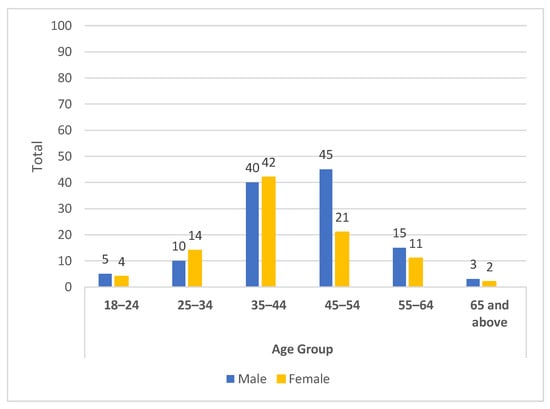

The demographic profile of the survey respondents is illustrated in Figure 2, which highlights the distribution across age groups and gender. Out of a total of 212 participants, 118 (55.7%) are male, while 94 (44.3%) are female. The largest segment of participants belongs to the 35–44 age group, which accounts for 38.7% of the respondents, with nearly equal representation from males (n = 40) and females (n = 42) and plays a crucial role in community resilience.

Figure 2.

Distribution of age group and gender.

In the younger age cohort of 25–34, female participation is notably higher, with 14 females compared to 10 males. This suggests that young women are more engaged in community-oriented or academic surveys. However, this trend shifts in older age categories. For instance, in the 45–54 age group, males significantly outnumber females (45 males vs. 21 females), making up nearly two-thirds of that segment.

Among the oldest respondents (aged 65 and above), male representation remains dominant, with 60% of this group being male. This demographic pattern indicates a diverse participation across all age groups, regardless of gender. However, engagement strategies may be necessary to encourage greater participation among older females, ensuring an inclusive approach to urban flood preparedness planning.

Additionally, the demographic distribution of the survey respondents provides essential insights into flood preparedness and risk perception. There are notable differences in engagement between genders and age groups. Younger women are more active in flood-related initiatives, while older males dominate in certain age ranges, indicating a need for targeted interventions. The observed gender and age dynamics indicate that a one-size-fits-all approach to flood preparedness would be insufficient. To enhance flood resilience across diverse demographic groups, it is essential to implement differentiated strategies that consider gender perceptions, generational preferences, and levels of technological familiarity. Thus, flood risk communication and adaptation planning must be tailored to different demographics by leveraging digital innovations for younger populations, maintaining inclusive leadership approaches for middle-aged adults, and employing personalised communication strategies for older individuals. This multi-faceted approach is vital for fostering inclusive, community urban flood resilience.

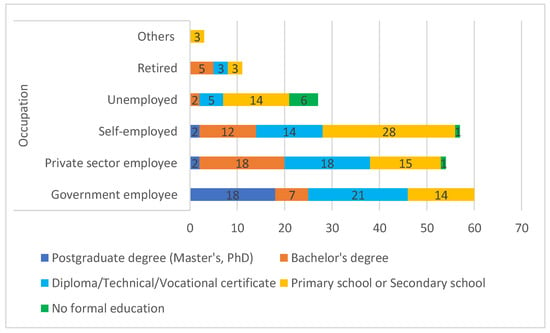

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution of educational attainment across various employment categories, offering insights into the socio-demographic characteristics of participants in this urban flood preparedness survey. A substantial proportion of respondents, particularly those employed in government and private sectors, possess higher education qualifications, including Bachelor’s and Postgraduate degrees. This trend reflects not only the formal education requirements associated with structured employment but also suggests that these individuals may have a greater capacity to engage in community-based disaster preparedness initiatives.

Figure 3.

Distribution of education levels by employment category.

In contrast, participants who are self-employed or unemployed exhibit a broader range of educational backgrounds, with a significant number having completed only primary or secondary school or lacking formal education altogether. This diversity in educational attainment may influence their access to flood-related information and how they participate in local adaptation strategies.

By including a broad spectrum of educational and occupational profiles, the survey provides a more representative understanding of urban flood preparedness. It also emphasizes the varying levels of awareness, resources, and institutional access among participants, which are the critical factors in shaping adaptive capacity. Capturing the perspectives of individuals with different educational and employment backgrounds allows the survey to present a more nuanced view of the socioeconomic factors that impact resilience and response to flood risks in urban environments.

Resilience is not just about physical infrastructure or technological solutions; it is also closely tied to social conditions, including education, employment, and income stability [40]. Recognising these differences is essential for creating inclusive flood risk management strategies that address the various needs and capabilities of different social groups. This knowledge can lead to targeted interventions, such as developing simplified educational materials for those with lower levels of education or creating specialised outreach programs for informal workers. These efforts aim to ensure that flood preparedness strategies are equitable and that no one is left behind.

3.2. Overview of Flood Perception Responses and Preparedness

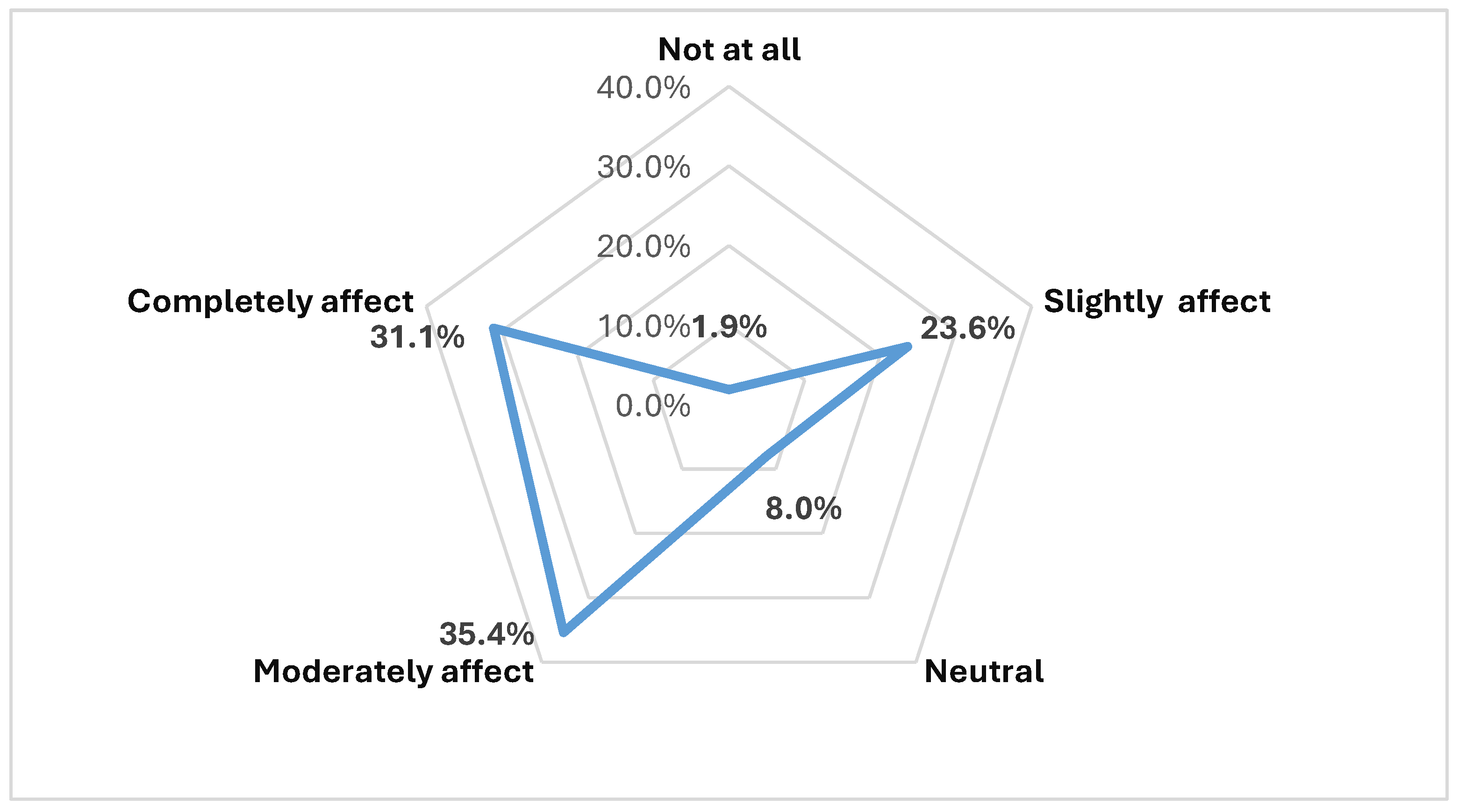

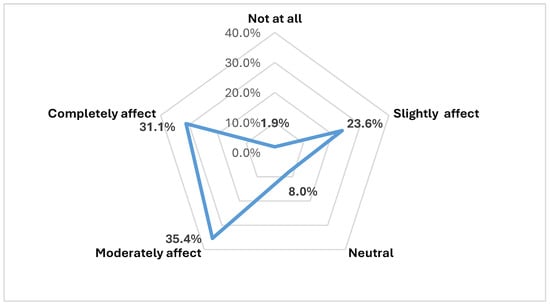

Respondents reported varying degrees of impact that urban floods have on their quality of life, as illustrated in Figure 4. Respondents were asked the following question: “To what extent do urban floods impact your quality of life?” using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (completely affected). A significant proportion, 35.4%, indicated that floods moderately affect their quality of life, while 31.1% reported that it is completely affected. This highlights that nearly two-thirds of respondents experience a substantial disruption due to flooding. Additionally, 23.6% felt that floods had a slight impact on their quality of life, whereas a smaller fraction remained neutral (8%) or indicated no impact (1.9%). These findings emphasise the tangible burden of flood events on daily living conditions, pointing to the need for more targeted preparedness and mitigation strategies to reduce such impacts. This finding echoes the concerns from a previous study [35], which noted that flood events intensify daily insecurities and should be considered a crucial part of the risk landscape that communities encounter. The considerable level of disruption underscores the need for policies that integrate flood management into urban socioeconomic planning.

Figure 4.

Response to the impact of urban floods on quality of life.

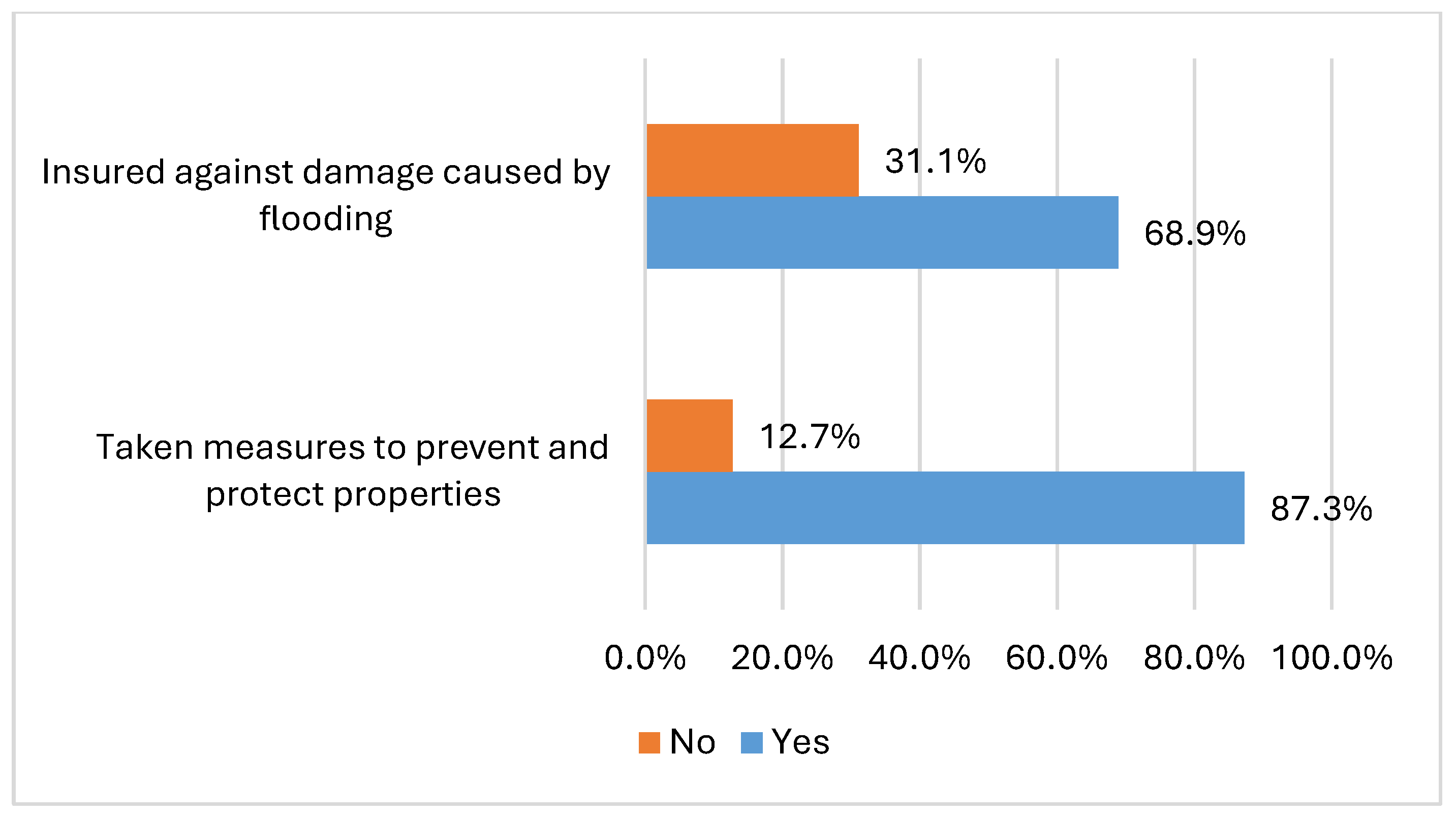

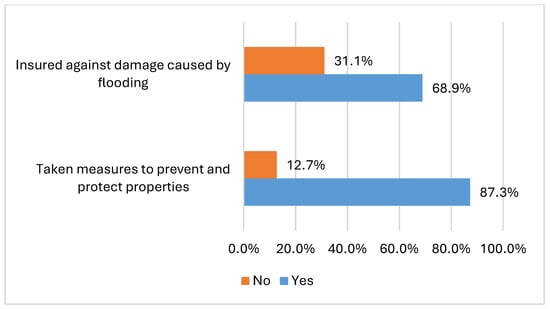

The extent to which respondents have taken proactive steps to reduce flood impacts is presented in Figure 5. Respondents were asked two separate yes-or-no questions to evaluate their readiness, specifically whether they had implemented property protection measures and whether their property was insured against flood damage. A substantial majority, 87.3%, reported having taken specific measures to prevent and protect their properties from flooding, reflecting a strong sense of personal responsibility and risk awareness. In contrast, regarding insurance coverage against flood damage, only 68.9% were insured, leaving 31.1% without coverage and exposed to potentially devastating economic losses. It is important to understand that flood insurance coverage options are limited and can significantly increase the financial burden on individuals. Most available flood insurance primarily protects physical assets, such as vehicles, depending on the type of premium purchased. Consequently, many households affected by floods often depend on post-disaster assistance, including financial aid from the government.

Figure 5.

Response to proactive steps to reduce flood impacts.

This disparity suggests that while many residents actively engage in preventive behaviours, a significant portion remains financially vulnerable in the event of flood-related losses. The gap between physical preparedness and financial resilience aligns with findings from Schubert et al. (2024) [41], which indicates that while communities often engage in immediate physical actions, financial and institutional adaptive behaviours tend to lag behind. This situation exemplifies the “capacity–action gap”, highlighting that financial vulnerability remains a significant obstacle to achieving comprehensive flood resilience [41]. It also highlights the importance of promoting not only physical preparedness but also financial resilience among urban populations at risk of flooding.

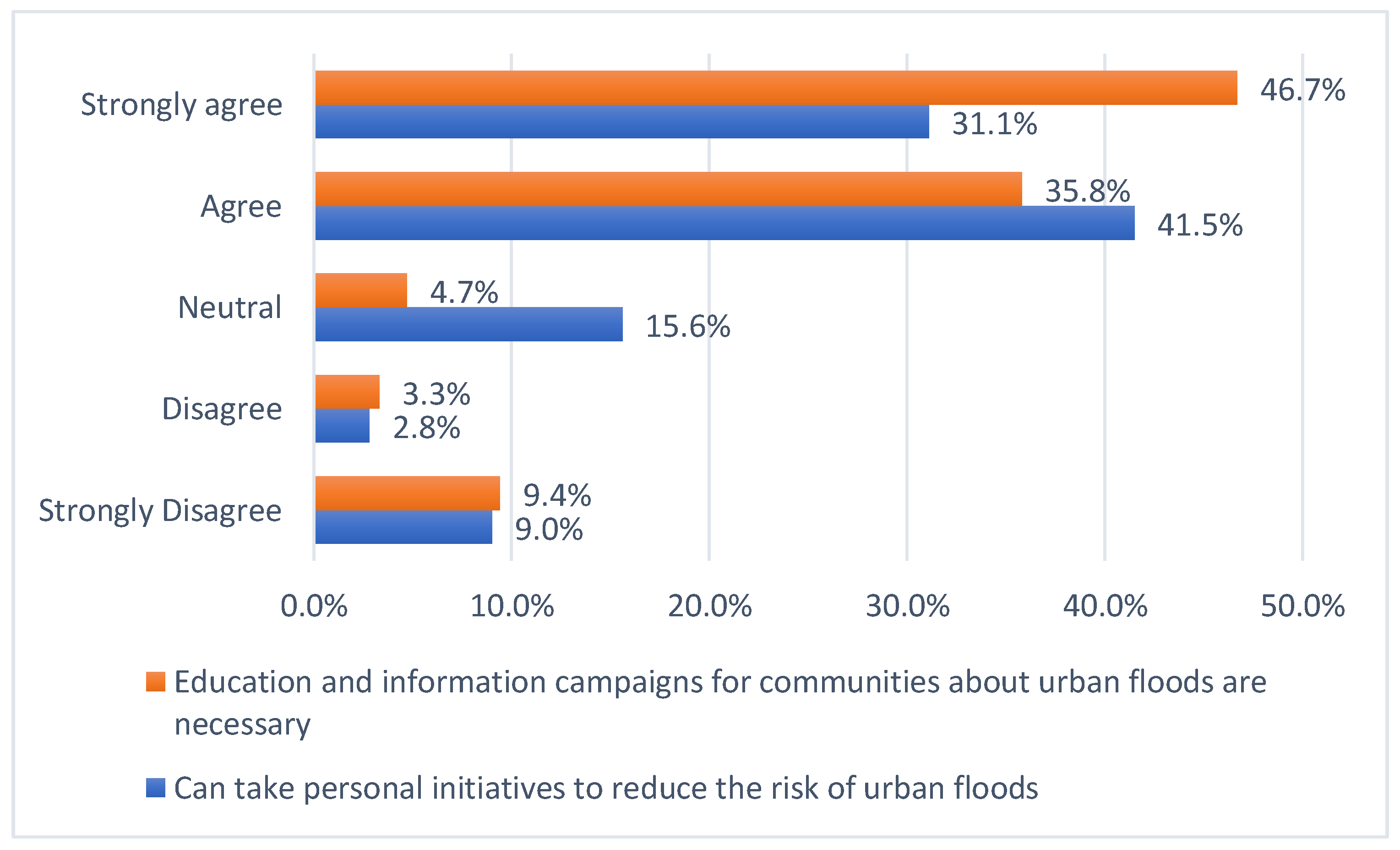

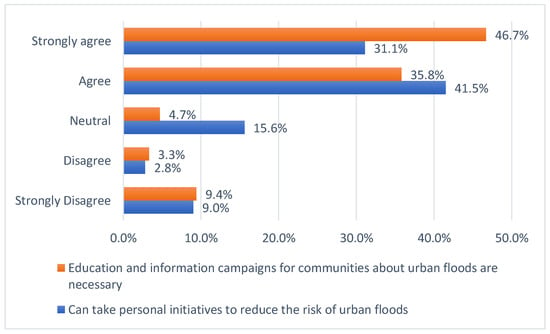

Respondents’ perspectives on two key dimensions of flood preparedness, the necessity of community education campaigns and their own personal initiatives, are illustrated in Figure 6. A notable 46.7% strongly agreed that education and information campaigns are essential, with another 35.8% agreeing, which reflects widespread recognition of the importance of public awareness in mitigating urban flood risks. In contrast, while personal action was also viewed positively, only 31.1% strongly agreed, and 41.5% agreed that they can take personal initiatives to reduce flood risk. A larger proportion (15.6%) remained neutral about taking action, suggesting a gap between awareness and behavioural response. These findings emphasise the importance of connecting information dissemination with community empowerment and the motivation to take action. The gap between awareness and individual action highlights the need for strategies that not only encourage behaviour change but also strengthen community-based initiatives for ongoing empowerment.

Figure 6.

Response to community education campaigns and personal initiatives.

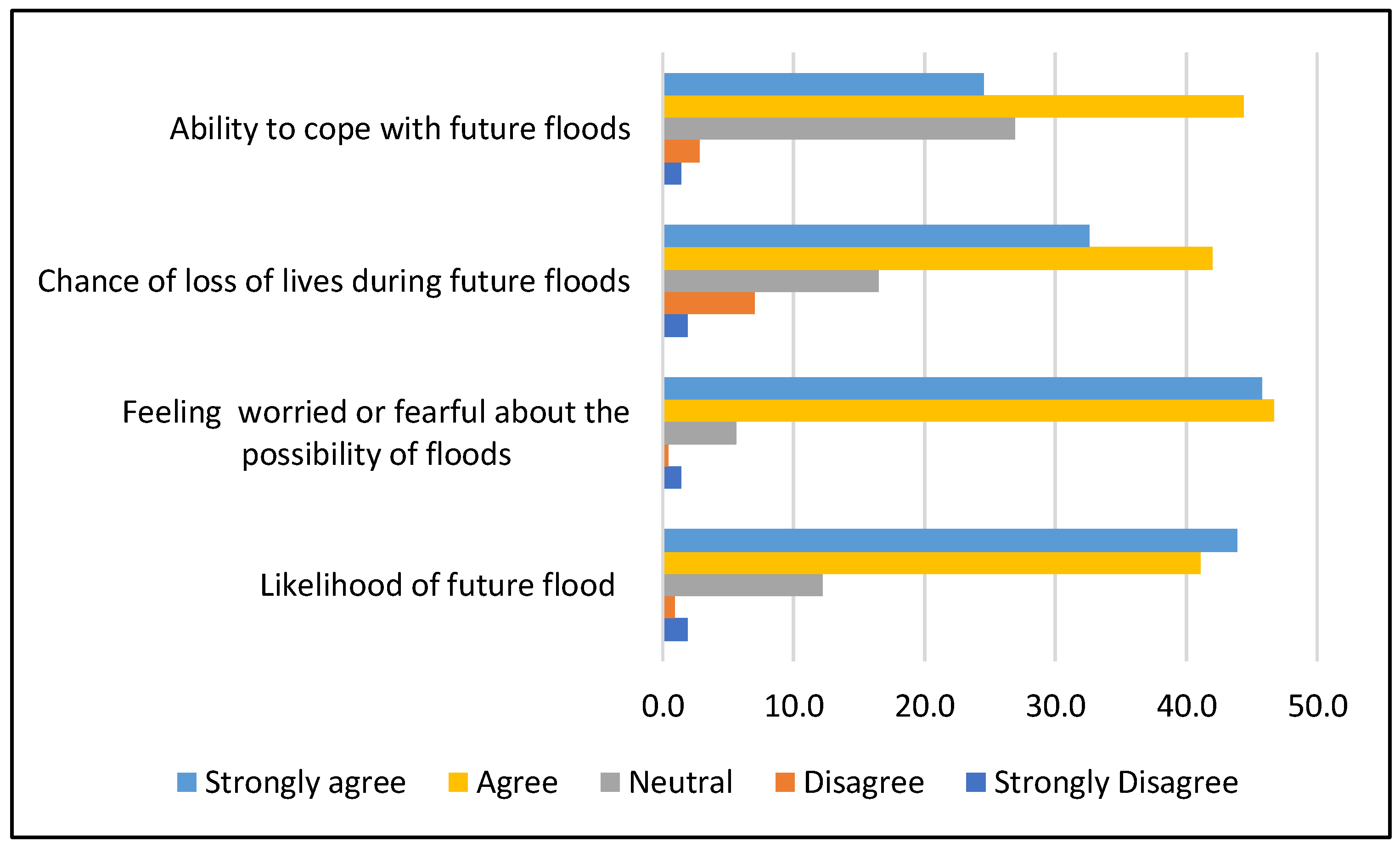

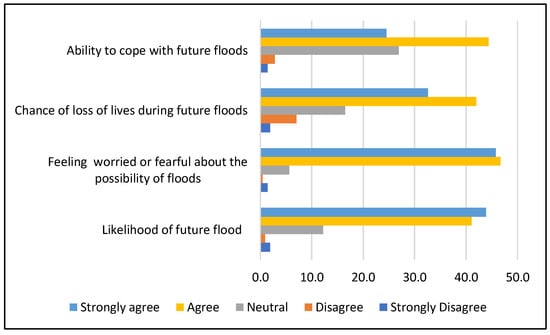

Respondents’ perception of urban flood risks across four dimensions, likelihood of future floods, emotional concern, perceived threat to life, and confidence in coping, is illustrated in Figure 7. A significant proportion of respondents expressed strong agreement (45%) and agreement (43%) with the likelihood of future flood occurrence in their area, underscoring heightened awareness of flood risks. Similarly, concern about floods was high, with over 85% agreeing or strongly agreeing that they felt worried or fearful about potential flood events. Regarding the perceived risk of losing lives, 42% agreed, and nearly 33% strongly agreed, indicating a significant concern for personal and community safety during future floods. In contrast, confidence in coping showed a more varied distribution. Over 40% agreed, and almost 25% strongly agreed that they could manage flood situations. A notable 27% remained neutral, while a small segment expressed disagreement, reflecting differing levels of self-efficacy in responding to floods. Residents recognise the potential for flooding and the danger it poses, yet they also feel confident in their ability to handle the situation. Past findings also indicate that previous flood experience can enhance awareness of risks and may cultivate a sense of confidence in addressing future events [42].

Figure 7.

Distribution of responses on flood risk perception.

Overall, risk perception among respondents was notably high, reflecting a strong emotional concern about floods and widespread anticipation of future flood events. This heightened awareness aligns with findings from Bixler et al. (2021) [43], who emphasised that strong social capital and collective memory of past flood experiences can significantly enhance community risk perception. Despite this high level of awareness, some respondents exhibited uncertainty about their ability to cope with future flood incidents, suggesting that confidence in adaptive capacity may vary among individuals. This observation underscores the psychological gap between recognising the risk and feeling capable of responding effectively. This phenomenon resembles Mortreux and Barnett (2017) [44], suggesting that adaptive behaviours are often constrained not by a lack of awareness but by doubts regarding personal efficacy and the capacity to act.

3.3. Analysis of Mean Scores

This study assessed three dimensions of community resilience to urban flooding: flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity. These constructs provide a comprehensive understanding of how well individuals and communities are equipped to anticipate flood events. Each construct was measured using a series of Likert-scale items in a structured questionnaire, and scores were aggregated to generate a mean. Descriptive statistics for all three constructs are summarised in Table 2. The analysis revealed a mean score of 4.20 (SD = 0.50) for flood preparedness, indicating that respondents generally reported a high level of readiness to confront potential future flood events. Risk perception was recorded at a mean score of 4.16 (SD = 0.53), indicating heightened awareness and concern regarding flood risks among the participants. Adaptive capacity yielded a slightly lower mean score of 3.97 (SD = 0.64), suggesting moderately positive perceptions of the community’s ability to implement coping strategies and adapt to flood-related challenges. Although the adaptive capacity score remains above the midpoint, it is the lowest among the three constructs. This suggests that, although residents are generally prepared and aware of risks, their ability to adapt and recover, particularly in the long term, may be more limited. The higher standard deviation indicates greater variability in adaptive capacity across the population.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity.

The findings further reinforce these observations regarding categorical classification in Table 3. The respondents’ mean scores for flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity were further classified into three categorical levels: low (1.00–2.99), medium (3.00–3.99), and high (4.00–5.00). For flood preparedness, 87.3% of participants were categorised as having a high level of preparedness, with only 0.5% falling into the low preparedness category. Similarly, for risk perception, 85.4% of respondents demonstrated a high level of risk awareness. However, adaptive capacity showed relatively more variability, with 66.5% of participants classified as having a high level of adaptive capacity, while a considerable proportion did not reach the high category threshold. These distributions suggest that while the community shows strong preparedness and risk awareness, further efforts are needed to enhance adaptive capacity to ensure long-term resilience to future flood events.

Table 3.

Mean category of flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity.

3.3.1. Flood Preparedness

The analysis of individual flood preparedness items in Table 4 demonstrates that preventing urban floods is perceived as a collective responsibility, with high mean scores reported for the need for collective efforts (M = 4.59), local community responsibility (M = 4.54), and the importance of non-structural measures such as training and awareness (M = 4.56). These results confirm that the public is aware of the shared responsibilities involved in flood risk reduction and recognises that non-structural approaches are just as crucial as structural interventions in mitigating the impact of urban flooding. These findings align with the past research findings that show preparedness is greatly enhanced through collective engagement and integrated, non-structural approaches [45].

Table 4.

Mean value for flood preparedness items.

Despite a high level of awareness regarding the dangers of floods (M = 4.51), the relatively lower mean score for taking personal initiative (M = 3.83) signals a gap between awareness and action. The analysis focused on specific items related to risk perception and flood preparedness. This disparity may reflect limitations in individual capacity, resources, or perceived effectiveness of personal efforts. This gap between awareness and personal action reflects patterns noted by Mortreux and Barnett (2017) [44], who argued that a high awareness of risk does not automatically lead to proactive behaviours, especially when there are limitations in resources.

Moreover, the lowest rated item, adequacy of the drainage system (M = 3.62), highlights persistent infrastructural deficiencies that may undermine community confidence in local flood management systems. Respondents also expressed concerns about the resilience of infrastructure, particularly the adequacy of drainage systems. Respondents pointed out these infrastructural shortcomings, emphasising the need for improvements to ensure reliable performance during adverse conditions. Similar infrastructural shortcomings were noted, as physical vulnerabilities often undermine overall community resilience, regardless of awareness levels [46].

Respondents also strongly supported education and information campaigns to enhance flood preparedness, with a mean score of 4.07. This underscores a widespread belief in the value of community awareness initiatives as a fundamental element in reducing flood vulnerability. The findings also suggest the importance of trust in communication platforms, including government channels and community outreach programs. However, the slightly lower rating compared to collective efforts and non-structural measures indicates that education alone is not perceived as sufficient. Instead, it must be strategically integrated with actionable policies, participatory planning, and structural improvements to build urban flood resilience effectively.

This study reveals that while respondents report a high level of preparedness for floods, there are significant differences in their perceptions of various aspects of that preparedness. There is strong support for community responsibility and non-structural measures; however, concerns exist about the adequacy of infrastructure and the perceived impact of floods. These findings highlight the need for improved community interventions to improve overall flood preparedness.

3.3.2. Risk Perception

The analysis of individual risk perception items reveals strong concern among respondents regarding the likelihood, impact, and consequences of future flood events. Table 5 presents the mean value for risk perception items. The highest-rated items highlight the anticipated disruption of essential services (M = 4.51) and the belief in significant damages to property and infrastructure (M = 4.46), indicating that residents are not only aware of the risk but are also acutely conscious of the potential severity of flood-related disruptions in urban environments.

Table 5.

Mean value for risk perception items.

Respondents also expressed high levels of emotional concern, as evidenced by the mean score of 4.35 for the statement “I feel worried and fearful about the possibility of floods”. This level of psychological alertness is a critical driver of community vigilance and preparedness behaviours. The belief that future floods are likely to occur (M = 4.24) further supports the notion that flood risk is widely acknowledged and internalised among the surveyed population.

In contrast, confidence in coping ability (M = 3.88) and knowledge of emergency protocols (M = 4.07) received relatively lower scores, pointing to potential gaps in individual-level readiness during flood emergencies. Furthermore, perceptions regarding institutional efforts and trust appear more varied. While the perception of current flood-related policies (M = 4.14) is moderately positive, the belief that authorities have taken all necessary measures scored lowest among all items at M = 3.86, with the highest standard deviation (SD = 1.073). This variation reflects uncertainty or scepticism among respondents toward institutional readiness and the comprehensiveness of governmental action.

Overall, the results indicate a community that is highly risk aware, emotionally engaged, and anticipatory of major disruptions, yet somewhat uncertain about personal capacity and institutional support. Risk perception among respondents was notably strong, with significant concern about potential property damage, disruption of essential services, and the likelihood of future floods. These observations support previous study findings, which indicate that direct experiences with service interruptions and collective memory of past flooding events heighten flood risk perception within communities [41,43]. While emotional concern regarding floods was high, confidence in individual coping abilities was relatively moderate. This psychological gap reflects past findings that emphasised self-efficacy plays a critical role in translating risk perception into effective adaptive actions [44].

3.3.3. Mean Index of Adaptive Capacity

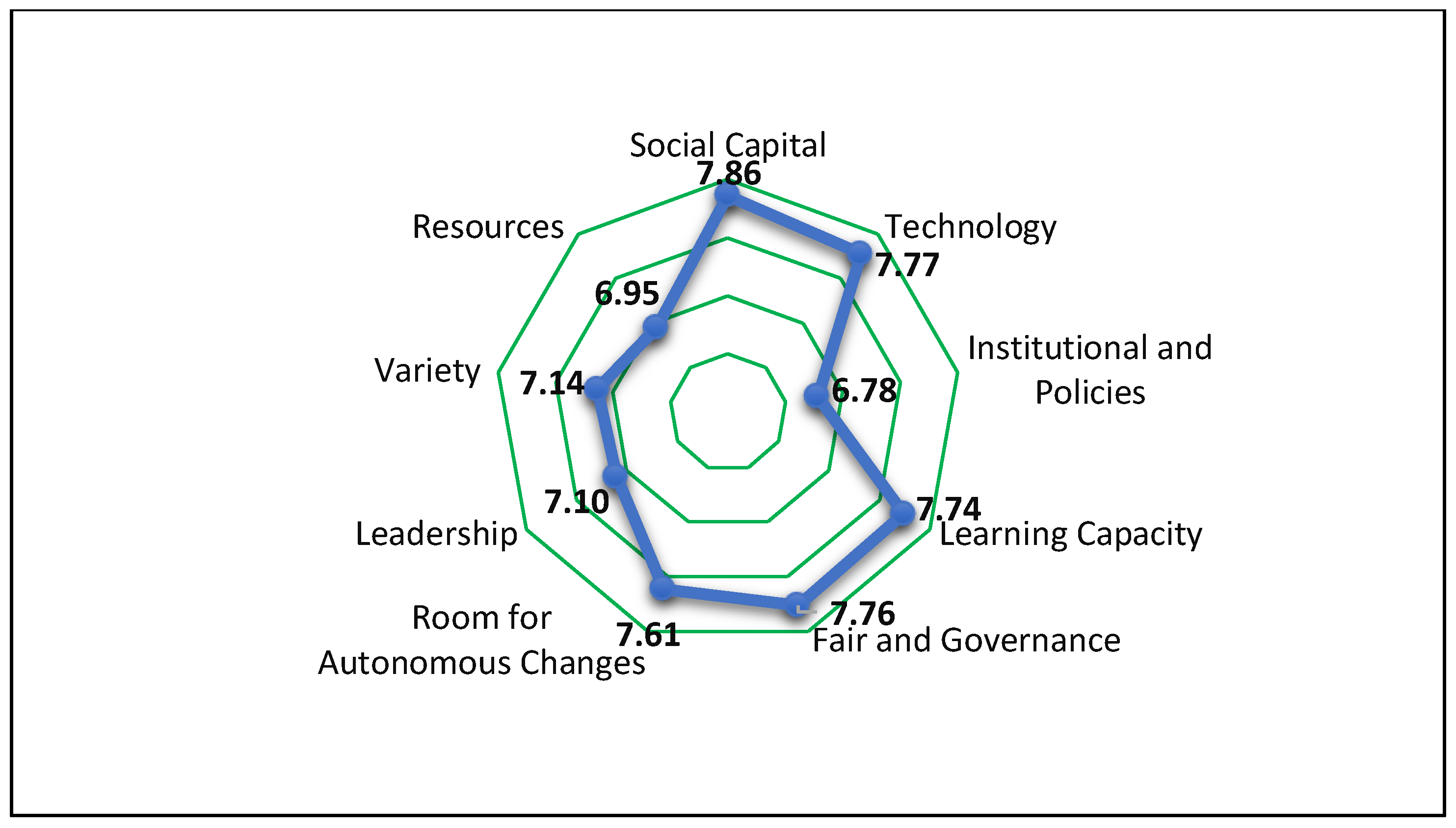

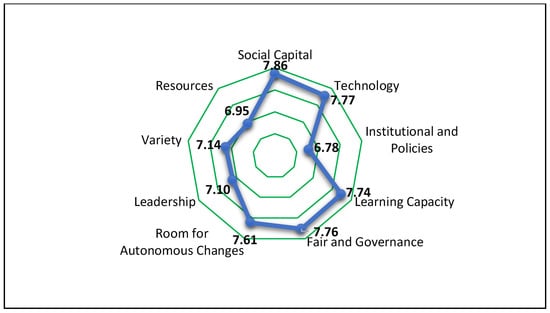

Adaptive capacity is assessed using a multidimensional framework comprising nine key indicators, including social capital, governance, technology, leadership, and others. It is calculated as a composite mean index derived from aggregated subcomponent scores. Unlike the average Likert score presented in mean score analysis, this section presents the adaptive capacity index, which reflects an integrated assessment across multiple dimensions. The analysis of the mean index values for adaptive capacity reveals generally positive perceptions across all components. However, substantial variation exists among the subconstructs, as illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Mean index for adaptive capacity constructs.

The ranking of core components that influence adaptive capacity provides valuable insights into a community’s strengths and identifies potential areas for targeted intervention. Mean indices and standard deviations were calculated for each component to assess their relative impact. A higher mean index indicates a stronger community perception of that component, as arranged from high to low index value, as illustrated in Table 6.

Table 6.

Mean index and standard deviation of adaptive capacity.

The assessment of mean index adaptive capacity components revealed that social capital was the most influential factor, with a mean index of 7.86. It was closely followed by technology and fairness and governance, scoring 7.11 and 7.76. Learning capacity had a score of 7.74. This indicates high levels of agreement regarding effective coordination with government agencies, mutual respect, technological adoption, and perceptions of fairness. Respondents generally view their communities as collaborative, technologically adaptive, and supported by relatively fair governance structures.

However, several critical gaps were identified. Institutional and policy support received the lowest mean index of 6.78, suggesting a lack of confidence in the effectiveness of institutions and the enforcement of flood-related policies. Resources were also rated low at 6.95, with concerns about funding availability, infrastructure, trained personnel, and essential relief resources. Leadership engagement received a moderate index rating of 7.11, indicating a perceived lack of proactive and visible leadership in flood resilience planning. These findings highlight that, while strengths exist in social capital, technological use, and governance, significant improvements are needed in institutional support, resource distribution, and leadership engagement to enhance overall community adaptive capacity.

The respondents generally rated their adaptive capacity positively, but this aspect received the lowest scores compared to flood preparedness and risk perception. This observation aligns with findings from Schubert et al. (2024) [41], who note that while adaptive capacity may be viewed favourably, challenges such as weak governance support, limited resources, and socio-psychological barriers often hinder communities from turning their intentions into practical adaptation measures. Similarly, institutional barriers can significantly obstruct the implementation of adaptive strategies [45].

Within the domain of adaptive capacity, social capital and technological readiness were identified as the communities’ strengths. This supports the argument by Bixler et al. (2021) [43] that strong social networks and technological integration play a critical role in enhancing community resilience. Conversely, weaker areas such as institutional and policy support, resource access, and leadership engagement reaffirm the conclusions of Birchall et al. (2025) [45] and Mortreux and Barnett (2017) [44], who note that systemic weaknesses and institutional barriers can inhibit long-term adaptive capacity, even in the presence of strong community initiatives. Furthermore, achieving higher resilience requires a collaborative approach that blends grassroots, community-driven efforts with top-down institutional strategies [47].

Access to resources, such as funding, emergency infrastructure, and trained personnel, remains a pivotal enabler of adaptive action. Without reliable access to these essentials, even communities that are risk aware and motivated to act may struggle to implement effective long-term resilience strategies. Collectively, these findings underscore that while the community demonstrates strong preparedness and heightened risk perception, closing the adaptive capacity gap through institutional reform, resource mobilisation, and local empowerment is essential for achieving enduring urban flood resilience.

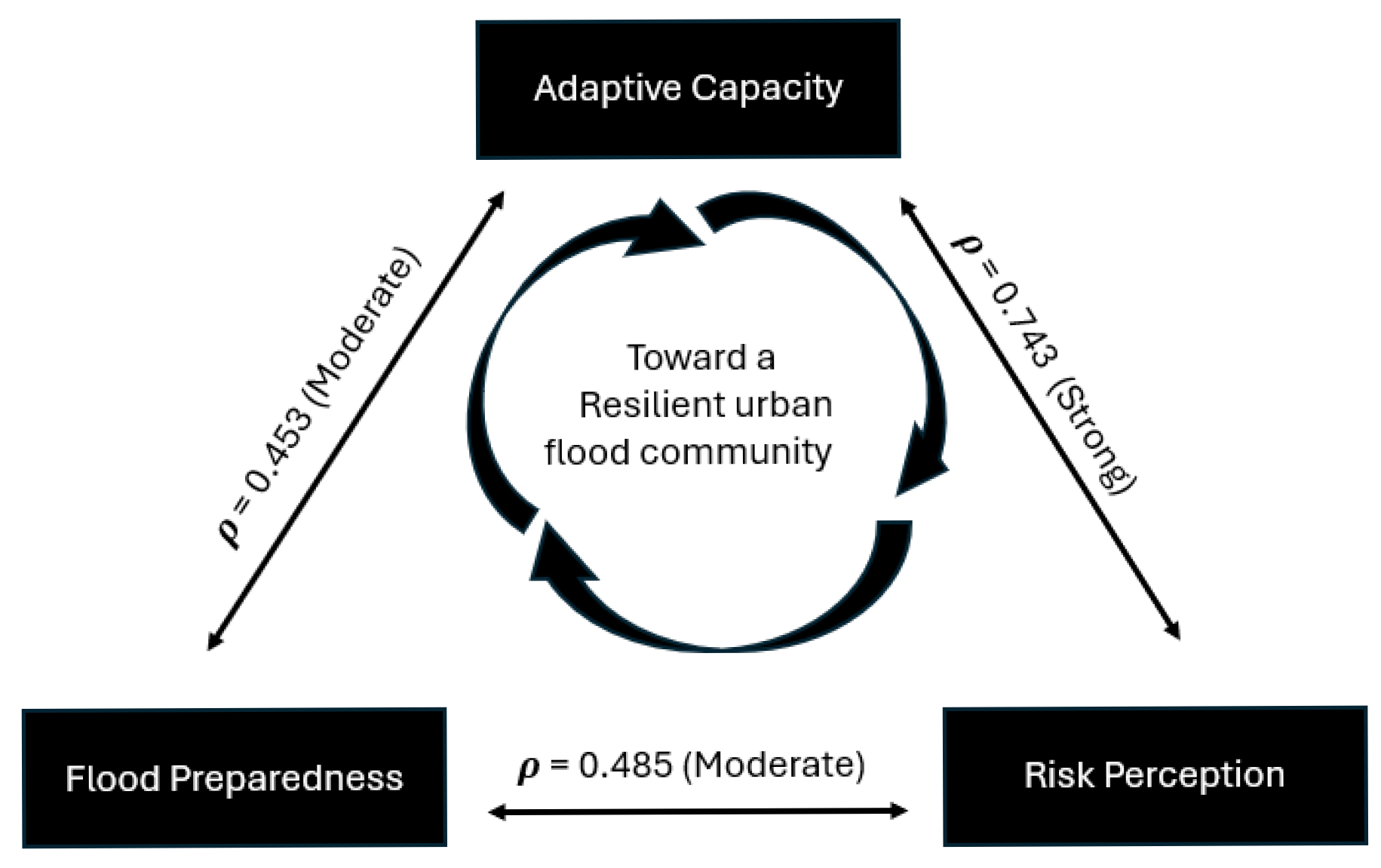

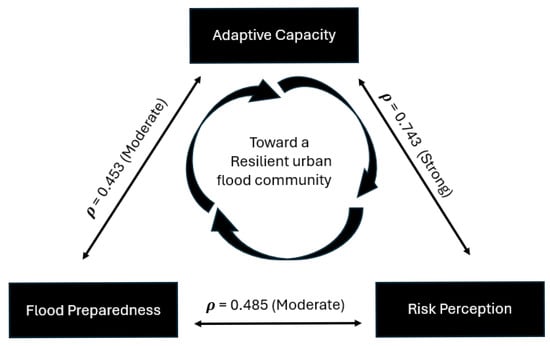

3.4. Exploring the Linkages Between Awareness, Preparedness, and Adaptation

Spearman’s correlation analysis examined the relationships among flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity. The findings are presented in Table 7. The results indicated that all three relationships were statistically significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed), with p-values less than 0.001 for each pair. A moderate positive correlation was observed between flood preparedness and risk perception (= 0.485, p < 0.001), suggesting that individuals with a higher perception of flood risks are more likely to engage in preparedness behaviours. It reflects the overall relationship between risk perception and flood preparedness. This finding is consistent with past studies emphasising risk perception as a significant driver of proactive flood preparedness initiatives [43,48]. Higher risk awareness, manifested through concerns about future floods, potential loss of life, and disruption of essential services, appears to motivate individuals to undertake preventive measures such as safeguarding property and participating in awareness campaigns.

Table 7.

Correlation analysis of preparedness, perception, and adaptive capacity.

Similarly, flood preparedness and adaptive capacity were also moderately correlated (= 0.453, p < 0.001), indicating that preparedness contributes to an individual’s ability to adapt and recover in the face of flood events. In other words, preparedness actions serve immediate protection purposes and enhance individuals’ and communities’ long-term ability to cope with, recover from, and adapt to flood risks. These findings align with the framework proposed by Schubert et al. (2024) [41], which highlights that preparedness measures contribute to building tangible adaptive assets, although challenges remain in translating preparedness into sustained adaptation.

Notably, a strong positive correlation was found between risk perception and adaptive capacity ( = 0.743, p < 0.001), highlighting that individuals who perceive greater risk tend to have significantly higher adaptive capacity. Respondents who had a higher perception of flood risk tended to report significantly greater adaptive capacity. As highlighted by Mortreux and Barnett (2017) [44] and further supported by van Valkengoed and Steg (2019) [49], psychological factors such as fear, trust, emotional concern, and perceived vulnerability play a crucial role in translating risk awareness into effective adaptation actions. Individuals who internalise the threat of floods are more likely to engage in adaptive behaviours, such as learning emergency protocols, strengthening community networks, and investing in long-term resilience strategies. These strategies should be consistent with adaptive community approaches that emphasise flexibility, the ability to embrace change, proactive adjustments, and continuous learning, enabling individuals and communities to respond effectively to flood risks [50].

Overall, the findings of this study indicate that flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity are closely interconnected, as shown in Figure 9. This relationship aligns with the Protection Motivation Theory (PMT). When people perceive flood risk as significant and pertinent, their threat appraisal increases, making them more inclined to take steps that go beyond basic preparedness. Strong risk perception correlates with adaptive capacity, while a moderate relationship between flood preparedness and adaptive capacity reflects the role of coping appraisal, which involves individuals evaluating their ability and available resources to respond to risks. However, without solid enabling conditions such as reliable leadership, accessible resources, and institutional support, they may find it challenging to act on their protective intentions. This can prevent those intentions from evolving into effective preparedness or sustainable adaptation.

Figure 9.

Interconnection between flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity in building a resilient urban flood community.

Strengthening risk perception and preparedness efforts can collectively enhance adaptive capacity, thereby contributing to the development of resilient urban flood communities. However, to fully achieve community resilience, comprehensive urban flood resilience strategies must also address systemic and contextual barriers, beyond just individual awareness and action.

4. Conclusions

The findings revealed that while residents demonstrate strong awareness of flood risks at 85.4% and a relatively high level of preparedness at 87.3%, adaptive capacity remains comparatively weaker and more inconsistent at 66.5%. High mean scores in flood preparedness indicate that urban communities value shared responsibilities and actively engage in managing flood risks. They demonstrate their readiness to take action, both individually and collectively, to address challenges proactively. Additionally, they are aware of the risks associated with flooding. Residents are worried not only about potential damage to their homes and disruptions to their daily lives but also about the intangible impacts on their emotional well-being and overall quality of life.

Urban communities possess strong social connections and are eager to utilise technology to manage flood risks effectively. However, they face significant challenges due to a lack of institutional and policy support, as well as limited resources. The significant positive correlations among flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity imply that they are closely interconnected in shaping urban flood resilience. The strong link between risk perception and adaptive capacity suggests that when individuals clearly understand the risks, they are more likely to take adaptive actions. Meanwhile, the moderate relationships with preparedness indicate that while communities are taking steps to get ready, their actions are more effective when paired with awareness and institutional support. These findings underscore the need for integrated strategies that not only promote preparedness but also foster an understanding of risk and supportive systems to facilitate long-term adaptation.

It is important to acknowledge several limitations of this study. Although the sample size was appropriate for the analyses, it may limit the generalizability of the findings to all urban areas in Malaysia. Future research should include more flood-affected cities to validate and expand the results. This exploratory study does not utilise advanced statistical modelling to assess latent constructs of adaptive capacity. However, its descriptive and correlational analysis lays a foundation for future, more rigorous investigations. Additionally, this research employed a quantitative survey to investigate the relationships between flood preparedness, risk perception, and adaptive capacity. While the survey provided valuable insights at the community level, it did not fully address institutional and governance factors that impact adaptive capacity. Future research could benefit from a mixed-methods approach that includes qualitative interviews with government officials, policymakers, and community leaders. These interviews would offer a deeper understanding of governance gaps, institutional challenges, and the effectiveness of policies, thereby complementing the quantitative findings and providing a more comprehensive view of flood resilience strategies.

Based on the findings, several recommendations are made to enhance urban flood resilience. Flood management must prioritise clear and open communication, involve community members in the planning process, and recognise them as essential partners in building resilience against floods. When urban residents feel empowered and included, they can play a vital role in creating a safer and more prepared community. It is also essential to strengthen institutional and policy support by promoting transparent and inclusive governance. Local authorities need to enhance their communication, coordination, and enforcement of flood-related strategies. Achieving this requires clear policies, consistent implementation, and stronger connections between the government and local communities. Additionally, interventions should foster long-term behavioural change by shifting the focus from reactive coping to proactive and transformative adaptation. Authorities should invest in community-based education, support local leadership, and ensure resources are distributed equitably, particularly to vulnerable groups. Implementing these measures will not only improve immediate flood preparedness but also cultivate a culture of long-term adaptation, ensuring that urban communities are better equipped to withstand and recover from future flood challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and F.Y.T.; Methodology, M.K., F.Y.T. and A.S.; Formal analysis, M.K. and A.S.; Investigation, M.K. and S.S.; Data curation M.K., S.S. and A.S.; Validation, F.Y.T., S.S. and R.A.F.; Writing—original draft preparation, M.K.; Review and editing, F.Y.T., A.S., S.S. and R.A.F.; Supervision, F.Y.T., A.S. and S.S.; Project administration, M.K. and F.Y.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Government of Malaysia and the University of Nottingham Malaysia for the assistance rendered.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. The Human Cost of Disasters: An Overview of the Last 20 Years (2000–2019); UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Swiss Re Institute. Natural Catastrophes in 2023: Gearing up for Today’s and Tomorrow’s Weather Risks; Swiss Re Institute: Zurich, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Thanvisitthpon, N.; Shrestha, S.; Pal, I.; Ninsawat, S.; Chaowiwat, W. Assessment of flood adaptive capacity of urban areas in Thailand. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2020, 81, 106363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Bhandari, G. Coping with urban flooding: A community portrayal of Bardhhaman Town, West Bengal, India. Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2024, 16, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosova, R.; Hajrulla, S.; Xhafaj, E.; Kapçiu, R. Urban Flood Resilience: A Multi-Criteria Evaluation Using Ahp and Topsis. J. Ilm. Ilmu Terap. Univ. Jambi 2024, 8, 812–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertilsson, L.; Wiklund, K.; de Moura Tebaldi, I.; Rezende, O.M.; Veról, A.P.; Miguez, M.G. Urban flood resilience—A multi-criteria index to integrate flood resilience into urban planning. J. Hydrol. 2019, 573, 970–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, I.A. Disaster and climate change resilience: A bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 50, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, B.; Garfin, G. Building urban flood resilience through institutional adaptive capacity: A case study of Seoul, South Korea. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 85, 103474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasantab, J.C.; Gajendran, T.; Maund, K. Expanding protection motivation theory: The role of coping experience in flood risk adaptation intentions in informal settlements. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 76, 103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joumar, N.; Gaganis, C.M.; Tourlioti, P.N.; Pantelakis, I.; Tzoraki, O.; Benaabidate, L.; El Messari, J.E.S.; Gaganis, P. Understanding Public Perception and Preparedness for Flood Risks in Greece. Water 2025, 17, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaniyan, F.A. Community flood preparedness in a collectivist cultural context: Lessons from Ibadan, Nigeria. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2024, 44, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, O.N.; Cetinkaya, I.D.; Yazar, M. Urban Flood Exposure and Vulnerability: Insights From Pendik District of Istanbul. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2025, 18, e70000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, K. Exploring ‘everyday-life preparedness’: Three case studies from Japan. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 34, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appleby-Arnold, S.; Brockdorff, N.; Callus, C. Developing a ‘culture of disaster preparedness’: The citizens’ view. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 56, 102133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Yan, X.; Song, H.; Xu, S. Influence of risk information and perception on residents’ flood behavioural responses in Inland Northern China. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 6285–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šiljeg, S.; Milošević, R.; Panđa, L. Public Perception of the Urban Pluvial Floods Risk—Case Study of Poreč (Croatia). J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijic SASA 2022, 72, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Zwickle, A.; Walpole, H. Developing a Broadly Applicable Measure of Risk Perception. Risk Anal. 2019, 39, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlan, S.L.; Sarango, M.J.; Mack, E.A.; Stephens, T.A. A survey-based assessment of perceived flood risk in urban areas of the United States. Anthropocene 2019, 28, 100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thistlethwaite, J.; Henstra, D.; Brown, C.; Scott, D. How Flood Experience and Risk Perception Influences Protective Actions and Behaviours among Canadian Homeowners. Environ. Manag. 2018, 61, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, N.L. Adaptive capacity and its assessment. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, K.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ebi, K.L.; Lim, B.; Aguilar, Y. Scoping and Designing an Adaptation Project; Technical Paper 1; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2004; p. 36. [Google Scholar]

- Tabasi, N.; Fereshtehpour, M.; Roghani, B. A review of flood risk assessment frameworks and the development of hierarchical structures for risk components. Discov. Water 2025, 5, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M.; Raymond, C.M.; Oczkowski, E.; Morrison, M. Measuring the dimensions of adaptive capacity: A psychometric approach. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.; Termeer, C.; Klostermann, J.; Meijerink, S.; van den Brink, M.; Jong, P.; Nooteboom, S.; Bergsma, E. The Adaptive Capacity Wheel: A method to assess the inherent characteristics of institutions to enable the adaptive capacity of society. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhuan, M.T.; Tue, N.T.; Hue, N.T.H.; Quy, T.D.; Lieu, T.M. An indicator-based approach to quantifying the adaptive capacity of urban households: The case of Da Nang city, Central Vietnam. Urban Clim. 2016, 15, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio, E.A.; Acosta, L.A.; Magcale-Macandog, D.B.; Macandog, P.B.M.; Lin, E.K.-H.; Eugenio, J.M.A.; Manuta, J.B. Adaptive capacity of Philippine communities vulnerable to flash floods and landslides: Assessing loss and damage from typhoon Bopha in Eastern Mindanao. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 19, 279–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye, W.A.; Bawakyillenuo, S. Diagnoses of the Adaptive Capacity of Urban Households to Floods: The Case of Dome Community in the Greater Accra Region of Ghana. Ghana J. Geogr. 2018, 10, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Saad, M.S.H.; Ali, M.I.; Razi, P.Z.; Bawono, A.S.; Ramli, N.I. A Preliminary Study on the Fuzzy Analytical Hierarchy Process (FAHP) for the Prioritization of Flash Flood Risk Index in Development Projects. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1444, 012025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DOSM. Laporan Khas Impak Banjir Di Malaysia 2021 Jabatan Perangkaan Malaysia Department Of Statistics Malaysia. 2022. Available online: https://www.nadma.gov.my/bm/penerbitan/penerbitan-3 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Ridzuan, M.R.; Razali, J.R.; Ju, S.Y.; Rahman, N.A.S.A. An Analysis of Malaysian Public Policy in Disaster Risk Reduction: An Endeavour of Mitigating the Impacts of Flood in Malaysia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2022, 12, 2006–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosedi, N.; Ishak, M.Y. Evaluation of the vulnerability and resilience towards urban flash floods in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1144, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, M.Y.; Bin, M.A.; Zain, M.; Haniff, M.; Hassan, B. Urbanization and growth of Greater Kuala Lumpur: Issues and recommendations for urban growth management. Southeast Asia A Multidiscip. J. 2022, 22, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. Flood Impact 2024. Available online: https://open.dosm.gov.my/publications/flood_impact_2024 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Šiljeg, S.; Milošević, R.; Mamut, M. Pluvial Flood Susceptibility in the Local Community of the City of Gospić (Croatia). Sustainability 2024, 16, 1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, I.A.; Lodhi, R.H.; Zia, A.; Jamshed, A.; Nawaz, A. Three-step neural network approach for predicting monsoon flood preparedness and adaptation: Application in urban communities of Lahore, Pakistan. Urban Clim 2022, 45, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pescaroli, G.; Velazquez, O.; Alcántara-Ayala, I.; Galasso, C.; Kostkova, P.; Alexander, D. A Likert Scale-Based Model for Benchmarking Operational Capacity, Organizational Resilience, and Disaster Risk Reduction. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2020, 11, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.L. Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1992, 5, 194–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougie, R.; Sekaran, U. Research Methods for Business, 8th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yusoff, S.; Yusoff, N.H. Building social resilience after the 2014 flood disaster. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 29, 1709–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, A.; Von Streit, A.; Garschagen, M. Unravelling the capacity-action gap in flood risk adaptation. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2025, 25, 1621–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazhuhan, M.; Amirzadeh, M. Flood risk perception and disaster preparedness in marginalised flood-prone communities: Evidence from Saadi neighbourhood, Shiraz, Iran. Local. Environ. 2024, 29, 680–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bixler, R.P.; Paul, S.; Jones, J.; Preisser, M.; Passalacqua, P. Unpacking Adaptive Capacity to Flooding in Urban Environments: Social Capital, Social Vulnerability, and Risk Perception. Front. Water 2021, 3, 728730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortreux, C.; Barnett, J. Adaptive capacity: Exploring the research frontier. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2017, 8, e467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birchall, S.J.; Kehler, S.; Weissenberger, S. ‘Sometimes, I just want to scream’: Institutional barriers limiting adaptive capacity and resilience to extreme events. Glob. Environ. Change 2025, 91, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Marrero, T.; Yarnal, B. Putting adaptive capacity into the context of people’s lives: A case study of two flood-prone communities in Puerto Rico. Nat. Hazards 2010, 52, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, N.; Das, A.; Mazumder, T.N. Decoding urban form resilience and adaptation in flood prone wards of Surat, India: Exploring the duality of public-private discourse. Environ. Dev. 2025, 55, 101178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelda, E.; Olanrewaju, L. Flood Risk Perceptioon Disaster Preparedness and Response in Flood-Prone Communities. J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2022, 14, 1303. [Google Scholar]

- van Valkengoed, A.M.; Steg, L. Meta-analyses of factors motivating climate change adaptation behaviour. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaresen, M.; Teo, F.Y.; Selvarajoo, A.; Sivapalan, S.; Falconer, R.A. Urban flood resilience with adaptive community approaches: A review. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).