Abstract

This study presents a comparative analysis of two rare thundersnow events accompanied by snowfall that occurred on 11 November 2023 and 10 December 2023 in Shaanxi province, China. Multiple data sources were integrated, including MICAPS surface and upper-air conventional detection observations, hourly meteorological records from Yanliang Airport, lightning location data, and ERA5 reanalysis, to examine and contrast the synoptic conditions, moisture transport mechanisms, and convective characteristics underlying these two events. The results indicate that the large-scale circulation patterns were characterized by a “high in the west and low in the east” configuration and a “two troughs-one ridge” pattern for the November and December cases, respectively. In both episodes, Shaanxi Province was located on the rear side of a high-pressure ridge, where a strong pressure gradient induced pronounced northerly winds that advected cold air southward, forming a distinct near-surface cold pool. During the November event, the convective cloud system developed east of the Tibetan plateau, guided by a westerly flow, and propagated eastward while gradually weakening, with a minimum brightness temperature of −42 °C. Conversely, in December, the convective activity initiated over southwestern Shaanxi and moved northeastward under a southwesterly flow, reaching a lower minimum brightness temperature of −55 °C, indicative of stronger vertical development. In both events, the principal water vapor transport occurred near the 700 hPa height level and was primarily sourced from the Bay of Bengal via a southwesterly flow. The November event featured a stronger northwesterly cold-air intrusion, whereas the December case exhibited a broader moisture channel. The CAPE values peaked during the afternoon and nighttime periods in both cases. The cold-pool and inversion-layer thickness were approximately 2 km/45 hPa in November and 0.8 km/150 hPa in December.

1. Introduction

Thunderstorms refer to mesoscale convective weather systems composed of deep cumulonimbus clouds and vigorous vertical motion, accompanied by phenomena such as lightning, thunder, heavy rainfall, strong winds, hail, and occasionally tornadoes [1]. In a narrower sense, they refer to deep convective processes associated with lightning activity [2]. They are typically characterized by a sudden onset, short life cycle, and significant spatial localization, often producing hazardous weather, such as hailstorms, intense gusts, and short-duration heavy precipitation [3,4]. Such events frequently result in significant human and economic losses, posing serious challenges to disaster prevention and weather forecasting [4,5,6]. A large number of climatological and statistical analyses have revealed a distinct seasonal variation in thunderstorm occurrences, with the peak frequency in summer and minimal activity in winter [4,7]. Data from meteorological stations across Northwest China indicates that thunderstorm activity is most frequent in summer, followed by spring and autumn, while winter thunderstorms are almost non-existent [7]. Consequently, most prior research focused on the mechanism, characteristics, and forecasting of warm-season convection, particularly during summer and autumn [8,9,10]. However, the threshold conditions governing thunderstorm development vary significantly across regions and seasons, reflecting differences in the atmospheric instability, moisture availability, and dynamic forcing [11,12,13].

Thundersnow (TSSN) is a rare atmospheric phenomenon characterized by the simultaneous occurrence of lightning, thunder, and heavy snowfall [14,15]. This phenomenon is also referred to as convective snowfall or a thunder snowstorm [16]. During the autumn and winter seasons, the atmospheric moisture content over mid-to-high-latitude regions is relatively low, which generally inhibits the development of deep convective systems. Consequently, precipitation during these seasons is predominantly stratiform rather convective. The probability of thundersnow near the coast or large lakes, where enhanced moisture influx and instability associated with lake-effect or sea-effect processes favor convective snow generation, is highly localized [15]. In contrast, continental regions at similar latitudes experience very few thunderstorm events. The simultaneous presence of large-scale snowstorms, lightning, and even hail within a winter convective system is exceptionally rare, making such events a subject of both operational forecasting interest and fundamental meteorological research [17,18].

Subsequent research has demonstrated that thundersnow is closely associated with elevated convection, in which the convective region is detached from the surface boundary layer [19,20,21,22]. Although the elevated-convection characteristics of thundersnow were discovered earlier [23], the phenomenon was formally conceptualized in the 1990s, when American scholars introduced the term based on multiple case analyses [24,25]. They found that such events typically develop on the cold side of frontal systems, where the base of the convective cloud lies above the planetary boundary layer. Wilson and Roberts [26] further revealed that during the elevated thundersnow events, the near-surface layer remains dominated by a shallow cold air mass, accompanied by a profound thermal inversion in both the temperature and wind profiles. Because this cold surface air cannot penetrate the inversion to access convective energy, instability arises above the inversion layer, where the adiabatic ascent of moist air initiates lightning and convective snow generation. These findings collectively indicate that thundersnow represents a special type of elevated convection, where thermodynamic instability and vertical shear above the boundary layer play a dominant role in storm electrification and precipitation processes.

In recent years, extensive research worldwide has advanced our understanding on elevated convection, achieving significant insights into its statistical characteristics [27], identification criteria, circulation backgrounds, radar signatures, associated weather types, formation mechanisms [28], spatiotemporal distribution, and frontal environments of regional elevated thundersnow events, contributing to refined classification of “thunder over snow” events [29,30]. Liu et al. [29] analyzed elevated thundersnow cases during the cold season across North China (2000–2015) and found that conditional symmetric instability (CSI) and frontal forcing under weak conditional stability, as well as near-neutral moist atmospheric stratification, were the primary mechanisms driving slantwise ascent and elevated convection during winter. Similarly, Zheng [30] categorized thundersnow events in Shandong Province into two major types—warm advection and sea effect—and provided a detailed summary of the thermodynamic and dynamic structural characteristics of each. Guo D M et al. [31] investigated an elevated thunderstorm event in early winter 2016 in Shaanxi Province, identifying conditional symmetric instability as the dominant instability mechanism responsible for convection over the Xi’an region. Their findings emphasized the role of strong vertical wind shear and mid-to-upper-level warm and moist airflow, which enhanced the atmospheric baroclinicity and promoted slantwise convection. Topography has also been shown to exert a critical influence on the formation of elevated thundersnow. Studies in the United States [24,32,33] have demonstrated that elevated convection systems most frequently develop across the Great Plains east of the Rocky Mountains, while being less common in northern inland and mountainous regions. Correspondingly, investigations in China [34] suggest that flat terrains, such as the North China Plain, Northeast Plain, and Middle–Lower Yangtze River Plain, favor the near-surface cold pools. These cold pools, combined with low-level jet streams, transport abundant moisture, providing favorable conditions for elevated convection above the stable surface layer.

Recent studies further underline the fact that elevated convection in mid-latitude winter and transitional regimes is controlled by a combination of moisture transport, instability above a capping layer, terrain modulation, and wave dynamics. Reanalysis and observation-based diagnoses emphasize the importance of multi-level moisture channels and CSI for supplying slantwise ascent and sloping instability in dry, continental basins. Jin et al. demonstrated how instability diagnostics and upper-level moisture pathways are essential for large precipitation events in arid basins, indicating that even low-column-humidity regions can support deep, elevated ascent when favorable transport and forcing occur [35]. Ma & Qin showed that elevated convection above a stable layer can generate ducted gravity waves, and that terrain ruggedness strongly modulates the propagation and organization of such waves, which, in turn, influence the initiation and clustering of elevated convective cells [36]. Ground-based remote-sensing analyses by Hoffman et al. highlight nocturnal elevated moist updrafts and elevated CAPE maxima along trailing cold-frontal boundaries, reinforcing the idea that elevated convection often preferentially develops at moist mid-levels rather than from the surface [37]. Finally, multi-sensor and reanalysis studies in complex terrain stressed that topography and mesoscale circulation patterns strongly alter convective structure and diurnal behavior, so inland elevated convection, while rarer, may arise under a distinctive set of synoptic and mesoscale preconditions [38]. Together, these recent results justified a focused case-comparative analysis of the rare 2023 thundersnow events in Shaanxi to diagnose the moisture pathways, elevated-instability mechanisms (e.g., CSI/slantwise ascent), and terrain–wave interactions that conventional surface-based convective parameterizations may miss.

The above-mentioned studies provide valuable insights into the diagnosis, forecasting, and early warning of elevated thundersnow in low-altitude, humid regions in China. However, in the arid and semi-arid regions of Northwest China, atmospheric water vapor content during the cold season is considerably low. Consequently, the precipitation is predominantly associated with cloud systems, which are less conducive to convective weather. Moreover, the more complex and highly variable underlying surface characteristics of semi-arid regions [39] hinder the formation and maintenance of cold pools, further reducing the likelihood of thundersnow during winter. Yanliang Airport is located in the Guanzhong Plain of Xi’an, Shaanxi Province. The southern part is geographically bounded by the Qinling Mountains to the south. This orographic influence generally suppresses instability, rendering winter convective weather extremely rare. As a result, meteorological support for winter flight testing primarily focuses on factors such as visibility, low cloud bases, and aircraft icing, while strong convective phenomena are often underestimated in winter operations.

This study analyzed two rare thundersnow events that occurred in Xi’an within a span of 31 days on 11 November and 10 December 2023. Both these events hold significant implications for flight test safety and for improving winter convective weather forecasting in Northwest China. Notably, although numerical weather prediction (NWP) models accurately forecasted the 24 h snowfall totals, they failed to accurately predict the lightning occurrence associated with these events. This discrepancy arose because the convective parameterization schemes in most operational models assume deep moist convection to be surface-based, thereby failing to capture elevated convection processes, leading to the systematic underreporting of elevated convection activity [40].

In this study, ERA5 atmospheric reanalysis data, MICAPS system conventional meteorological observations, FY-4 satellite imagery, and hourly observation data from Yanliang Airport were utilized to conduct a comparative analysis of these two thundersnow events. The objective was to provide a technical reference for forecasting the first snowfall and winter thundersnow episodes in Xi’an and to enhance meteorological support for flight testing operations under thundersnow conditions.

2. Data and Methodology

The present study employed multiple sources of observational and reanalysis data to diagnose and compare the physical mechanisms underlying the two thundersnow events that occurred in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province, on 11 November and 10 December 2023. The datasets include (1) hourly ground-based meteorological observation data from Yanliang Airport (Xi’an, China); (2) surface and upper-air observations obtained from the MICAPS system (MICAPS, version 4.0) of the China Meteorological Administration (CMA, Beijing, China) for 10–11 November and 9–10 December 2023; (3) ERA5 atmospheric reanalysis data provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF, Reading, UK), with a horizontal resolution of 0.25° × 0.25°, which was used to analyze the large-scale circulation and thermodynamics of dynamic fields; and (4) FY-4A satellite infrared 10.8 μm channel cloud imagery (with a temporal resolution of 15 min, provided by the National Satellite Meteorological Center (NSMC), China Meteorological Administration (Beijing, China)) to examine the convective cloud-top structure and brightness temperature evolution.

Using synoptic diagnosis techniques, the analysis integrated these datasets to identify the mesoscale circulation background, vertical thermodynamic structure, and cloud system evolution during the two events. Diagnostic parameters—including the equivalent potential temperature, vertical velocity, conditional symmetric instability (CSI), convective available potential energy (CAPE), and potential vorticity—were computed from ERA5 to evaluate the instability and moisture transport characteristics. Comparative interpretation was performed by combining the satellite cloud-top temperature variation with lightning occurrence data to clarify the mechanisms triggering elevated convection and thundersnow formation.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Overview of Weather Processes

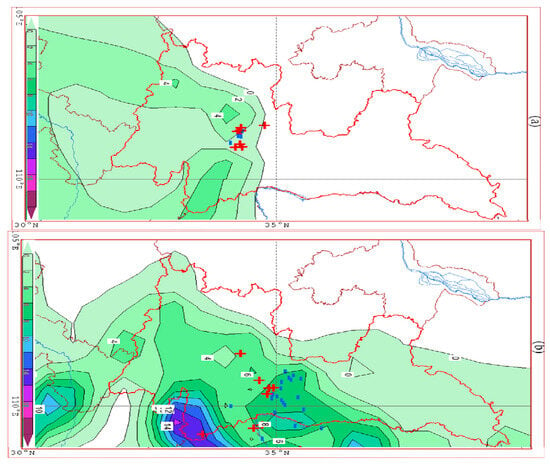

Two distinct thundersnow (TSSN) events occurred in the Xi’an region within a one-month interval on 11 November and 10 December 2023. The first event (11 November) produced heavy snowfall across several districts, including Beilin, Xixian New Area, and Lintong. The maximum instantaneous precipitation intensity at the compound of the People’s Congress of Shaanxi Province reached 13.3 mm/h−1 at 07:00, followed by 4.5 mm/h−1 at 08:00. The cumulative precipitation in the area affected by the strong convective weather significantly weakened six hours after the end of the process, as represented in Figure 1a.

Figure 1.

The distribution of precipitation in Shaanxi Province from 08:00 on 10 November to 14:00 on 10 November 2023 (a) and from 20:00 on 10 December to 02:00 on 11 December 2023 (b).

Thundersnow activity persisted from 07:00 to 08:30 local time, lasting approximately 90 min. A total of six lightning discharges were detected in the city during this period, including three strong positive cloud-to-ground (CG) flashes associated with hazardous discharge polarity. The convective core originated over western Xi’an and propagated eastward, showing a gradual decay as the stratiform precipitation zone expanded. In contrast, the 10 December event exhibited a more zonal, i.e., east to west, precipitation distribution. The thundersnow in Xi’an City mainly occurred on its northeastern side, and only two positive lightning flashes were recorded within the city. The cumulative precipitation at Jinghe Station reached 6.3 mm, and at Gaoling Station, it reached 7.3 mm during a six-hour period, accompanied by a rapid decrease in the lightning frequency and cloud-top brightness temperature, as represented in Figure 1b.

3.2. Variations in Meteorological Elements at Yanliang Airport

Under the influence of the “thunder and snow” weather process in Xi’an area on 11 November it was overcast at Yanliang Airport before 16:00 and cloudy after 16:00. From 05:30 to 09:20 in the morning, the airport successively experienced light rain, sleet, and light snow. Although the precipitation lasted for 3 h and 50 min, the cumulative precipitation was only 0.2 mm. During the overcast period, the cloud base height was maintained between 1200 and 1500 m. The wind speed at the airport was relatively low, with an average wind speed of only 1.2 m/s from 06:00 to 20:00. Except for 15:00, the wind speed at other hourly observation times was no more than 2 m/s. The wind direction at the airport changed significantly, with southeasterly wind in the morning and southwesterly wind in the afternoon, ranging from 129° to 255°. The visibility at the airport fluctuated significantly, dropping from 10 km before the precipitation to a minimum of 3 km, improving to 10 km in the afternoon, and then dropping to 4 km in the evening.

On 10 December, a “thunder and snow” weather process occurred in the Xi’an–Yanliang area. The thunderstorm at Yanliang Airport occurred from 20:25 to 20:40. The lightning location was to the northeast of the airport. The cloud layer in the airport area significantly lowered from mid-level cumulus clouds with a cloud base height of 3300 m to broken rain clouds with a cloud base height of 300 m, and the low cloud persisted for a long time, lasting for 5 h. The precipitation occurred from 16:20 to 24:00, with light rain lasting for 4 h and 30 min before turning to sleet, and then to light snow after 15 min. The 24 h precipitation was as high as 10.6 mm. The wind speed at the airport changed greatly. Before 17:00, the wind speed was consistently above 5 m/s. The average wind speed reached 9 m/s during the midday period (13:00 to 14:00). As the strong convective system approached, the wind speed rapidly decreased when the precipitation began. One hour before the thunderstorm, the average wind speed dropped to 2 m/s. The visibility at the airport fluctuated significantly. In the morning, due to the mixed phenomenon of haze and fog, the visibility was maintained at around 5 km. In the afternoon, the fog phenomenon ended and the visibility improved to 10 km before the precipitation. After the precipitation began in the evening, the visibility rapidly dropped to 1.5 km due to the fog phenomenon.

3.3. Upper-Level Circulation Situation

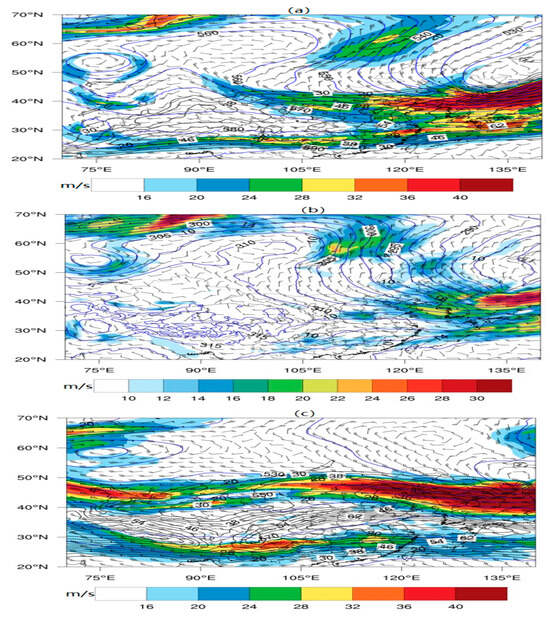

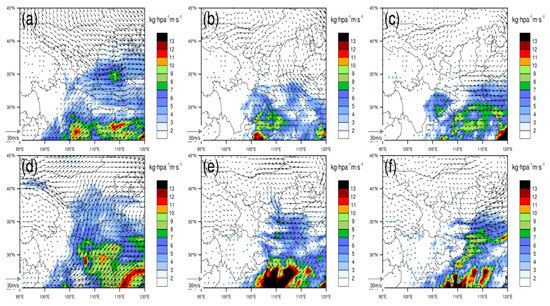

At 20:00 on 10 November, at the 500 hPa level (Figure 2a), the mid–high latitudes exhibited a west-high–east-low pattern. An anticyclone was active in the western area of Lake Baikal, with the ridge line extending northeastward. A low-pressure system was present over the Sea of Japan, and the cyclonic low-pressure center extended a west–east-oriented trough westward. The East Asian trough extended to the northern part of Inner Mongolia. The meridionality of the circulation was significant, indicating the presence of strong cold air activity. In the mid–low latitudes, the subtropical high was distributed in an east–west band along the South China coast. A weak ridge existed from the eastern part of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau to the eastern part of Xinjiang. The westerly flow prevailed from the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River to the southern part of North China. The jet stream was located from North China to the Sea of Japan. Xi’an was on the southern side of the 500 hPa jet stream. At the 200 hPa level, there was remarkable upper-level jet stream activity from the Sea of Japan to North China, with the central wind speed exceeding 60 m/s. Xi’an was at the rear of the upper-level jet stream, which featured wind speed divergence. Shaanxi was in front of the low-pressure trough, with a westerly jet stream above. At the corresponding 700 hPa circulation field (Figure 2b), the front part of the Baikal Lake high-pressure ridge was influenced by northeasterly winds, with the maximum wind speed exceeding 20 m/s. The wind direction changed to northwesterly in Inner Mongolia. The Yellow Sea region of China was under the influence of westerly winds, with wind speeds exceeding 20 m/s. The southern part of China was in the northern part of the subtropical high, with southerly winds. A distinct shear line was formed by the southerly and northwesterly winds in Gansu. The southerly wind in southern Shaanxi reached 6 m/s. Xi’an was on the southern side of the shear line and was about to be affected by it.

Figure 2.

Composite map of 500 hPa geopotential height (blue contour lines), wind speed > 16 m·s−1 (shaded area), and 200 hPa wind speed > 30 m·s−1 (black contour lines) at 20:00 on 10 November 2023 (a); composite map of 700 hPa geopotential height (blue contour lines) and wind speed > 10 m·s−1 (shaded area) at 20:00 on 10 November 2023 (b); composite map of 500 hPa geopotential height (blue contour lines), wind speed > 16 m·s−1 (shaded area), and 200 hPa wind speed > 30 m·s−1 (black contour lines) at 08:00 on 10 December 2023 (c); composite map of 700 hPa geopotential height (blue contour lines) and wind speed > 10 m·s−1 (shaded area) at 08:00 on 10 December 2023 (d).

At 08:00 on 10 December, at the 500 hPa level (Figure 2c), the mid–high latitudes presented a “two troughs and one ridge” circulation pattern. Low vortices were active in the northern part of the Sea of Japan and the western part of Lake Balkhash. There was a high-pressure system in Lake Baikal. The mid-latitudes also showed a “two troughs and one ridge” pattern. The high-pressure ridge was located in the central part of Mongolia, and the low-pressure troughs were over the Sea of Japan and Xinjiang. There was short-wave trough activity in the eastern part of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. The southern branch trough was located in the southern part of the plateau. The subtropical high-pressure ridge was along the South China coast. Shaanxi was in the front part of the short-wave trough in the eastern part of the plateau, with a dominant southerly flow above. At the 200 hPa level, there was significant upper-level jet stream activity from the Huai River Basin to the eastern part of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, with the central wind speed reaching 70 m/s. Xi’an was near the axis of the upper-level jet stream. At the corresponding 700 hPa circulation field (Figure 2d), a high-pressure ridge extended from the sea to North China. The southern part of China was in the southerly flow behind the high-pressure ridge. There was a low-level southerly jet stream in South China, with the center located in Yunnan and the wind speed reaching 18 m/s. There was low-pressure trough activity in the central part of Gansu. Shaanxi was in the southerly flow in front of the low-pressure trough.

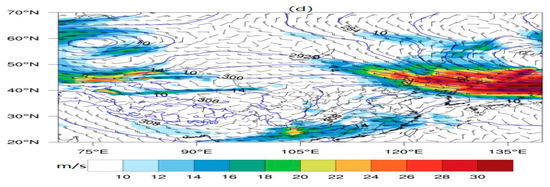

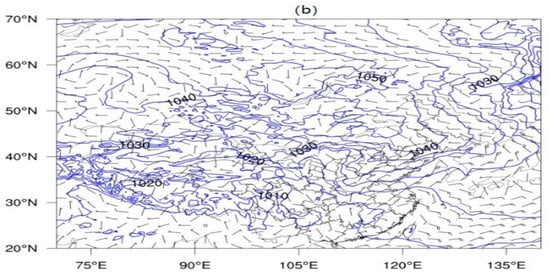

3.4. Surface Weather Situation

A comparative analysis of the surface charts of the two processes (Figure 3) indicates that in both instances, a high-pressure system was active in the southern part of Central Siberia to the region of Mongolia, and the center of the high pressure was situated in the western part of Mongolia. In the November process, the central pressure reached 1048 hPa, and the ridge line extending eastward from the high pressure was located in the Liaoning area. In the December process, the high pressure was more intense, with a central value of 1050 hPa, and the ridge line extending eastward from the high pressure was located in North China. During both processes, the eastern region of China was under the influence of the high-pressure circulation, being controlled by a northerly wind. Shaanxi was located at the rear of the high-pressure ridge, featuring a strong pressure gradient force. It was discovered that the gradient was greater in the first process compared with the second one. The powerful continental high pressure formed a northerly wind that was capable of transporting cold air from the north to the south, forming a cold pad at the surface.

Figure 3.

Surface synoptic chart at 20:00 on 10 November 2023 (a) and sea level pressure (blue contour lines) and 10 m wind field (wind barbs) at 08:00 on 10 December 2023 (b).

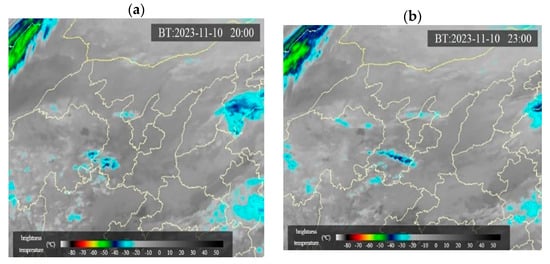

3.5. Comparative Satellite Monitoring

From the evolution of the satellite cloud images (Figure 4), at 20:00 on 11 November 2023, the convective cloud system developed and moved eastward from the east side of the plateau under the guidance of the westerly airflow. At 23:00 on 10 November, the cloud system passed through the southeast of Gansu Province. By 02:00 on 11 November, the main body of the convective cloud system moved to the Guanzhong area of Shaanxi Province. At 08:00, the high-value area of the convective cloud system’s brightness temperature appeared in the Xi’an area and then weakened and continued to move eastward. At 11:00 on 10 December, a southwest–northeast-oriented convective cloud band emerged on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and moved eastward and northward under the guidance of the southwesterly airflow. At 17:00 on 12 December, it moved to the Guanzhong and northern Shaanxi areas. At 20:00, the convective cloud system was vigorously developing, with the southern part covering the northern part of Xi’an, and the gradient of the brightness temperature increased significantly compared with the previous three hours. By comparing the development of the two convective cloud systems, it can be found that both originated from the east side of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. In November, the convective cloud band exhibited the entire process of development and weakening, with the lowest brightness temperature reaching only −42 °C. During the process in December, the convective cloud system continued to develop, and its movement direction showed an eastward and northward trend, with the lowest brightness temperature reaching −55 °C.

Figure 4.

Satellite cloud images of TBB at 20:00 (a), 23:00 (b), 02:00 (c), and 08:00 (d) on 10 November 2023 and at 11:00 (e), 14:00 (f), 17:00 (g), and 20:00 (h) on 10 December 2023.

3.6. Comparative Analysis of the Formation Mechanism of TSSN

3.6.1. Comparison of Water Vapor Conditions

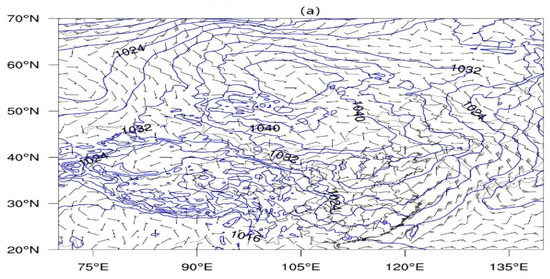

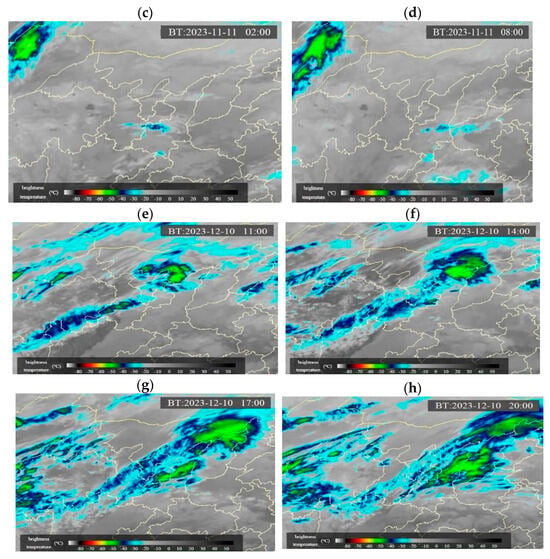

Water vapor conditions are indispensable for the occurrence of snowfall and convective weather. Xi’an is located in the Guanzhong Plain with an average altitude of 1027 m, which is relatively low. Strong convective weather mostly occurs in the middle and lower tropospheres (700–900 hPa). Therefore, Figure 5 presents the spatial distribution of the water vapor fluxes and wind fields at 700 hPa, 850 hPa, and 900 hPa during the two processes. The analysis revealed that at 700 hPa, both processes were characterized by the southwesterly airflow transporting warm and humid air from the Bay of Bengal to Shaanxi. In the first process, the northwesterly cold air was particularly strong, converging with the southwesterly warm and humid air in the Guanzhong area of Shaanxi. In the second process, the southwesterly airflow was more vigorous, transporting water vapor from the Bay of Bengal as far as central Inner Mongolia. At 850 hPa, only a weak southeasterly water vapor transport component from the Yellow Sea was present in the first process, while in the second process, water vapor from the Bohai Sea, Yellow Sea, and the returning easterly airflow was involved.

Figure 5.

The water vapor fluxes (colored fill) and horizontal wind fields (arrows) at 700 hPa, 850 hPa, and 925 hPa on 10 November 2023 at 20:00 (a–c) and 10 December 2023 at 08:00 (d–f).

At 925 hPa, the returning easterly airflow transported warm and humid air from the Bay of Bengal and the South China Sea to the Shaanxi region. When comparing the two processes, it was found that the northwesterly cold air was stronger in the November convective weather process than in the December process, while the southwesterly airflow was more vigorous in the December process. As a result, the water vapor transport in the first process reached the southern part of northern Shaanxi, while in the second process, it could reach Inner Mongolia. The longitudinal water vapor transport channel was narrower in the first process and wider in the second process. The water vapor content between 700 hPa and 925 hPa exceeded 5 kg·m−2·s−1 in both processes. In the lower layer (850–925 hPa), due to the strong convergence of the easterly wind speed in the northeast of Xi’an, a large water vapor flux area appeared in this region.

To substantially strengthen the diagnostic framework, this investigation included a detailed description of the vertical thermodynamic and dynamic structure associated with the two thundersnow events. First, to address the CSI and slantwise ascent, we incorporated vertical cross-sections of equivalent potential temperature (θe) and moist absolute momentum, along with refined vertical-wind analyses. These diagnostics allowed for an explicit evaluation of symmetric stability. The revised analysis identified layers that satisfied the CSI criterion (∂M/∂z < 0), demonstrating that the November event contained a relatively shallow CSI-favorable layer between approximately 750 and 650 hPa, whereas the December event exhibited a deeper and more coherent CSI signature that extended from 800 to 600 hPa. This added evidence directly substantiates the presence of elevated slantwise ascent as a triggering mechanism for thundersnow in both cases.

Second, cross-sections of the Ertel potential vorticity (PV) were added, through which the dynamical forcing associated with upper-level jet streaks was revealed. The revised results show that the November case was influenced by a sharper and stronger mid-to-upper-level PV intrusion over central Shaanxi, which produced more intense dynamical lifting. However, in contrast, the December case featured a broader but weaker PV anomaly, which resulted in a more widespread, yet comparatively weaker, ascent. These diagnostics provide a clearer physical link between upper-level forcing and the evolution of elevated convection.

Finally, to strengthen the comparison of water vapor transport, the moisture analysis beyond qualitative descriptions was added. Vertically integrated water vapor fluxes and flux divergence fields were included. The updated results quantitatively show that the maximum moisture flux in the November event was approximately 5.30 kg·hPa−1·m·s−1 and was confined to southern areas of northern Shaanxi due to stronger northwesterly cold advection. In contrast, the December event benefited from a more vigorous and extensive southwesterly low-level jet, with flux maxima reaching 7.02 kg·hPa−1·m·s−1 and a transport pathway extending as far as Inner Mongolia. Moreover, although both events exhibited more than 5 kg·hPa−1·m·s−1 of moisture flux within the 700–925 hPa layer, the December event had a significantly wider longitudinal moisture corridor and stronger low-level convergence northeast of Xi’an, where average flux values exceeded 6.1 kg·hPa−1·m·s−1.

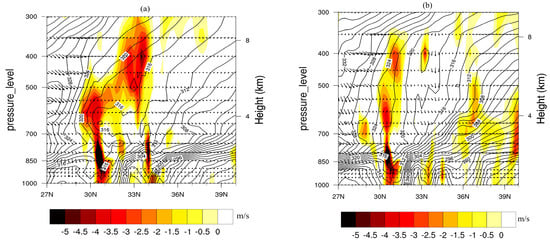

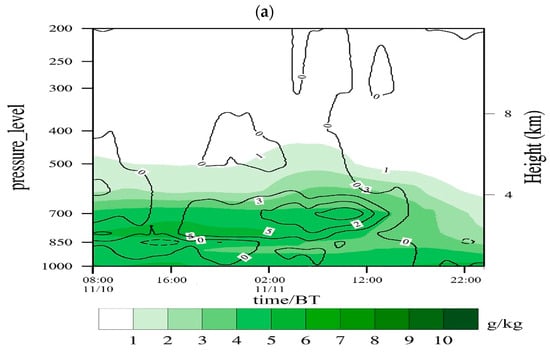

To better characterize the vertical structure and convective intensity of the two thundersnow events, ERA5 reanalysis data were analyzed along the 109°E meridional cross-section using the pseudo-equivalent potential temperature (θe), vertical velocity, and wind profiles (Figure 6). For the 11 November event, θe values below 850 hPa indicate cold-air influence in the lower layers, while θe decreased with height between 850 and 700 hPa, suggesting moderate instability conducive to convection. The vertical velocity fields indicate weak upward motion in this layer, consistent with observed lightning activity. By 08:00 UTC, θe increased with height, reflecting stabilization and enhanced subsidence (vertical velocities reaching −5.2 Pa·s−1).

Figure 6.

Latitude–height cross-sections along 109°E at 20:00 on 10 November 2023 (a), 08:00 on 11 November 2023 (b), 08:00 on 10 December 2023 (c), and 20:00 on 10 December 2023 (d), showing pseudo-equivalent potential temperature (contours, unit: K), vertical velocity (shaded), and wind field (wind barbs).

For the 10 December event, θe below 850 hPa similarly indicates cold-air influence. Between 850 and 700 hPa, θe initially decreased with height, which favored weak convection, but gradually became nearly neutral by 14:00 UTC, indicating stabilization, which corresponded to weak downward motion. By 20:00 UTC, enhanced subsidence was observed with vertical velocities of −5.8 Pa·s−1. Overall, while both events occurred under weak instability, the November case exhibited slightly stronger mid-level upward motion, consistent with the larger number of lightning strikes observed.

Although direct microphysical measurements were unavailable, the combination of vertical instability, weak mid-level ascent, and moisture convergence suggests graupel–ice interactions as the dominant mechanism for electrification. Snow particles likely grew via riming and aggregation within the mid-level convective cores, enabling charge separation and subsequent lightning discharges, consistent with observed positive ground flashes. This integrated analysis quantitatively assessed the convective intensity and linked thermal stratification, vertical motion, and plausible microphysical processes, providing a robust physical interpretation of the two thundersnow events.

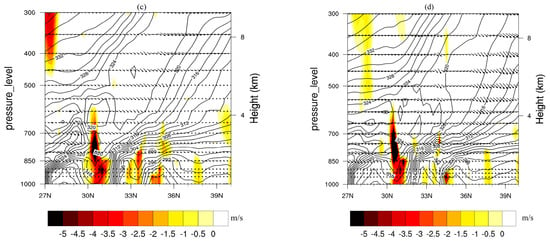

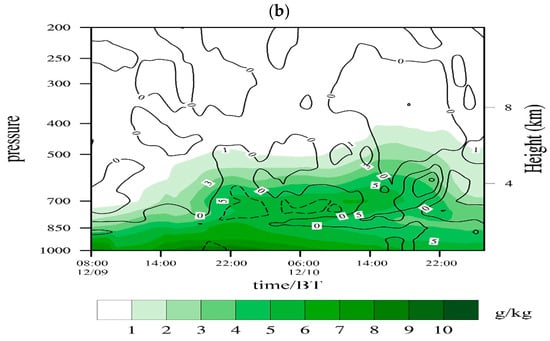

To further compare the water vapor conditions of the two strong convective processes in Xi’an, ERA5 reanalysis data were used to present the height–time cross-sectional distribution of average specific humidity and water vapor flux divergence in Xi’an from 08:00 on 10 November 2023 to 23:00 on 11 November 2023 and from 08:00 on 9 December 2023 to 08:00 on 11 December 2023 (Figure 7). The analysis shows that the water vapor conditions were better in the middle and lower tropospheres (700–850 hPa) during the November process. Weak convergence of the water vapor flux occurred at 700 hPa in the early morning and morning of 11 November, which was the main cause of the “thundersnow” phenomenon during this process. Compared with the November weather process, the water vapor conditions were better in the December process, and the convergence of water vapor flux mainly occurred at 850 hPa. At 400 hPa, a convergence area of water vapor flux also appeared from 20:00 to 21:00 on 10 December, which coincided with the occurrence time of the “thundersnow”. The convergence areas of water vapor flux in both strong convective processes were located in the middle troposphere, which is a characteristic of elevated convective storms.

Figure 7.

The spatiotemporal evolution of the average water vapor flux divergence (contours, unit: 10−8 g·s−1·cm−2·hPa−1) and specific humidity (shading) in the Xi’an region (33°~35° N, 107°~112° E) on 10–11 November 2023 (a) and 9–10 December 2023 (b).

Figure 5 explicitly shows the horizontal moisture flux (color-shaded) and wind-field vectors at 925 hPa, 850 hPa, and 700 hPa for both events, i.e., 10–11 November and 10 December. These three levels were selected because they represent the core inflow layers associated with low-level moisture supply in winter thundersnow environments. Figure 5 reveals structural differences that were less apparent in the earlier version. Moisture transport during the November event remained confined to a narrow southwest–northeast corridor, constrained by a stronger intrusion of northwesterly cold air. The 925–850 hPa moisture plume was shallow and spatially limited, which reflected terrain-induced channeling between the Loess Plateau and the Qinling Mountains. In contrast, the December event featured a broader, deeper, and more coherent moisture-flux belt that extended from the southwest toward central Shaanxi, supported by stronger southeasterly inflow at 925 hPa and an expansive 850 hPa moisture plume that reached as far as Inner Mongolia. These characteristics indicate enhanced warm-air advection and the presence of a stronger low-level jet, which resulted in greater moisture availability and more widespread precipitation.

Recent studies emphasize that winter elevated convection and thundersnow result from the coupling of mesoscale moisture transport, dynamic lifting, and terrain-modulated flow. Harkema et al. [41] showed that wintertime stratiform and banded snow regimes can become electrically active through mixed-phase and riming processes sampled in the NASA IMPACTS campaign, demonstrating mechanisms relevant to our cases. Fernández-Álvarez et al. [42] used WRF–FLEXPART Lagrangian diagnostics to quantify moisture source contributions for landfalling atmospheric river events, highlighting how long-range moisture transport can feed mid-level instability—a process analogous to the southwest moisture corridor we diagnose for the December event. Yang et al. [43] demonstrated in a cloud-scale numerical study that ice multiplication and riming greatly modulate cold-season cloud electrification, lending microphysical support to our graupel–ice interpretation under weak instability. Finally, using the Lake-Effect Electrification (LEE) field campaign synthesis, Steiger et al. [44] provided recent observational evidence that riming and mixed-phase microphysics, together with low-level flow organization, control winter lightning production; this supports our view that terrain-modulated moisture funnels and mid-level ascent governed the differing convective signatures in the November and December events.

3.6.2. Convective Available Potential Energy (CAPE)

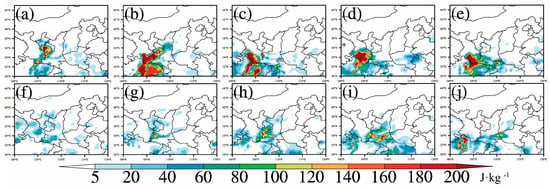

Spatial distribution maps of the convective available potential energy (CAPE) in Shaanxi Province at 08:00, 14:00, and 20:00 on 10 November 2023; at 02:00 on 11 November 2023; and at 08:00, 11:00, 14:00, 17:00, and 20:00 on 10 December 2023 were provided using ERA5 reanalysis data. Although there is a certain error between the CAPE in the reanalysis data and the actual sounding data, it can still basically reflect the spatial distribution characteristics of the CAPE. Through the spatio-temporal comparison analysis of the spatial distribution maps of CAPE during the two convective processes, it can be seen that high CAPE values occurred in the afternoon and night during both processes. During the first convective process, the high CAPE value area was located at the junction of Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia (Figure 8a–e). The intensity of the CAPE center value showed a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with time, while its spatial distribution changed little. The high-value center developed from the junction of Shaanxi, Gansu, and Ningxia at 08:00 on 10 November and then moved southward to the junction of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau and northern Sichuan, with little change in the position of the center value area. The CAPE value in the Xi’an urban area was very weak, and the distribution was in an east–west band, located in the south. The CAPE value was the largest one day before the thunderstorm occurred, while on the day of the thunderstorm, the CAPE value in Xi’an was basically 0 J·kg−1. During the second convective process, the CAPE value increased with time and moved eastward. The maximum CAPE value in Xi’an occurred 3 h before the thunderstorm, reaching up to 221 J·kg−1. After the thunderstorm, the CAPE value decreased rapidly.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of convective available potential energy (CAPE, J kg−1). (a) 08:00 LT on 10 November 2023; (b) 14:00 LT on 10 November 2023; (c) 20:00 LT on 10 November 2023; (d) 02:00 LT on 11 November 2023; (e) 08:00 LT on 11 November 2023; (f) 08:00 LT on 10 December 2023; (g) 11:00 LT on 10 December 2023; (h) 14:00 LT on 10 December 2023; (i) 17:00 LT on 10 December 2023; (j) 20:00 LT on 10 December 2023.

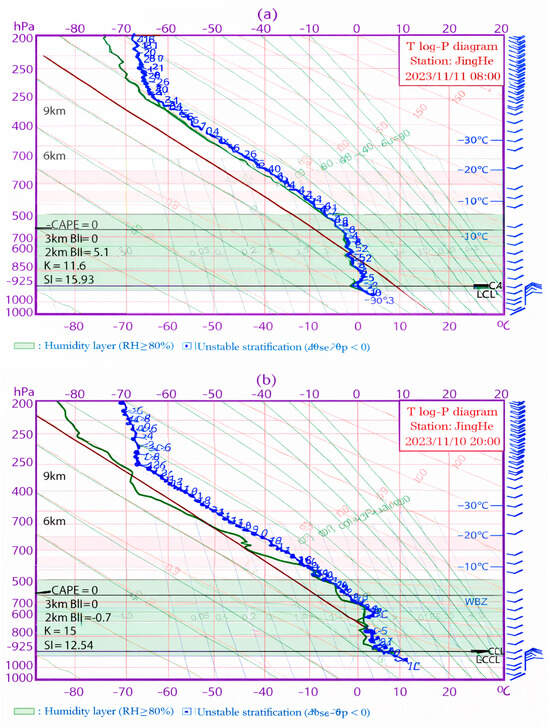

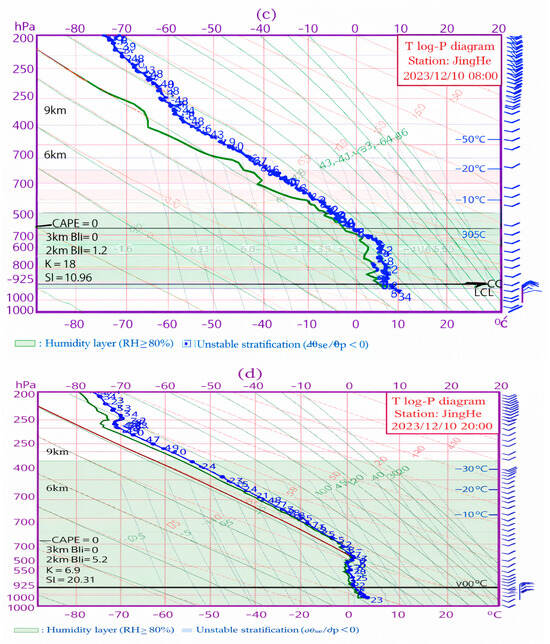

3.6.3. Comparison of Atmospheric Stratification Characteristics

The actual radiosonde data (Figure 9) show that the CAPE at Jinghe Station was 0 J·kg−1 during both processes. When the CAPE value was very small or zero, the reason for the occurrence of elevated thundersnow was the existence of cold pools and inversion layers. Therefore, by analyzing the evolution of the atmospheric stratification characteristics during the two convective processes from the radiosonde curves, it can be seen that before the convective process in November, there was a significant cold pool and inversion layer at Jinghe Station. The thickness of the cold pool was 2 km, and the temperature difference between the bottom and top of the cold pool was 7 °C. The inversion layer was located near 770 to 815 hPa, with a thickness of 45 hPa and a temperature difference of 5 °C. The unstable stratification was in the middle and upper tropospheres between 700 hPa and 500 hPa, with a thickness of 200 hPa. The moist layer was in the middle and lower tropospheres. After the thunderstorm process (08:00 on 11 November), the inversion layer at Jinghe Station disappeared, and the moist layer significantly increased. Before the convective process in December, the radiosonde chart at Jinghe Station showed that the thickness of the cold pool was 0.8 km, and the temperature difference between the bottom and top of the cold pool was 6 °C. The inversion layer was between 750 and 900 hPa, with a thickness of 150 hPa, but the temperature difference was only 3 °C. The unstable stratification was located near the height layer of 700 hPa to 450 hPa. By comparison, it was found that the cold pool in the convective process in November was deeper than that in December. The reason for this is that the convective process in November occurred under the background of strong northwesterly airflow supplementing southward along the Hexi Corridor. The land–atmosphere interaction caused by the rapid ground cooling radiation at night led to the cooling of the air above the cold pool, which enabled the deep cold pool to be maintained at night.

Figure 9.

Sounding data from Xian Jinghe Station at 20:00 on 10 November 2023 (a), 08:00 on 11 November 2023 (b), 08:00 on 10 December 2023 (c), and 20:00 on 10 December 2023 (d).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

This study utilized ground and upper-air conventional detection data, hourly observation data from Yanliang Airport, lightning location data, FY-4 satellite cloud images, and ERA5 reanalysis data to comparatively analyze two rare thunderstorms with snowfall events on 11 November 2023 and 10 December 2023. The causes and mechanisms of the two events were explored and compared, leading to the following conclusions:

- (1)

- During the November convective process, the high-latitude circulation background presented a west-high–east-low pattern, with the East Asian trough extending to the northern part of Inner Mongolia, and the circulation was highly meridional with strong cold air moving southward. In the December strong convective process, the mid–high latitude circulation pattern was “two troughs and one ridge”, and the mid–high latitude system was relatively weak. When the November process occurred, Xi’an was located in front of the 700 hPa low-pressure trough, and there was a westerly jet stream at 500 hPa. During the December process, Xi’an was located in front of the southern branch trough at the 700 hPa height level, under the control of strong southwesterly airflow, and the 500 hPa height level was dominated by southwesterly airflow. During both processes, the eastern part of China was under the influence of a high-pressure circulation, with a northerly risk control, and Shaanxi was behind the high-pressure ridge, with a strong pressure gradient force. It was found that the gradient in the first process was greater than that in the second process. The strong continental high-pressure system formed a northerly wind that could transport cold air from the north to the south, forming a cold pad on the ground.

- (2)

- Through a comparison of the development and evolution patterns of convective clouds, it was discovered that in November 2023, the convective cloud system originated from the eastern side of the plateau, developed and moved eastward under the guidance of the westerly airflow, weakened after passing through the Xi’an area, and continued to move eastward, where the minimum brightness temperature reached −42 °C. During the process in December, the convective cloud system was oriented southwest–northeast and moved eastward and northward under the influence of the southwesterly airflow, with the minimum brightness temperature reaching −55 °C.

- (3)

- The main water vapor transport channels for both “thundersnow” processes were at the 700 hPa height level, and the water vapor was guided by the southwestern airflow from the Bay of Bengal to Shaanxi. During the November convective weather process, the northwestern cold air was stronger than that in the December convective process. The longitudinal water vapor channel in the second process was wider than that in the first process, with the water vapor content exceeding 5 kg·m−2·s−1 between 700 hPa and 925 hPa. At the lower level (850 hPa to 925 hPa), due to the strong convergence of the easterly wind speed in the northeast of Xi’an, a large water vapor flux area appeared in this region.

- (4)

- The high CAPE in both processes occurred from the afternoon to the night. During the first convective process, the CAPE value in Xi’an was very weak, with an east–west band distribution and a position biased southward. During the second convective process, the CAPE value increased with time and moved eastward, with the maximum CAPE value in Xi’an occurring 3 h before the thunderstorm and reaching up to 221 J·kg−1. After the thunderstorm, the CAPE value decreased rapidly. Before both convective processes, there were significant cold pads and inversion layers at Jinghe Station. The cold pad thickness in the November process was 2 km, and the inversion layer was near 770 to 815 hPa, with a thickness of 45 hPa. The cold pad thickness in the December convective process was 0.8 km, and the inversion layer was between 750 and 900 hPa, with a thickness of 150 hPa. Under the influence of the high-latitude large-scale circulation background and the land–atmosphere interaction at night, the cold pad in the November convective process was deeper than that in the December process.

5. Future Work

Future investigations should aim to improve the predictive understanding of elevated-convection thundersnow in arid and semi-arid regions by integrating higher-resolution numerical simulations and more comprehensive observational platforms. The two events examined in this study revealed clear signals of elevated instability, moisture transport pathways, and cold-pad structures that current operational models did not resolve. Convection-permitting models, together with Doppler radar and lightning-mapping observations, would allow for a more accurate depiction of the vertical development, electrification structure, and convective triggers associated with wintertime elevated convection. In addition, quantitative moisture source diagnostics could help clarify the role of long-range transport from low-latitude regions, which appeared influential in both cases. Expanding the analysis to a multi-year climatology of thundersnow events in Northwest China would also help determine how representative these two cases are and would support the development of improved early-warning strategies for aviation operations in regions where thundersnow is rare but operationally significant.

Author Contributions

Y.L.: Writing—review and editing, investigation, software, writing—original draft, and conceptualization. H.N.: Data curation, writing—original draft, methodology, writing—review and editing, and supervision. J.L.: Validation, project administration, writing—review and editing, writing—original draft, and formal analysis. Y.C.: Visualization, resources, and writing—review and editing. X.H.: Methodology and writing—review and editing. S.L.: Writing—original draft and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Civil Aircraft Specialized Research Project of the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (mjz5-xxxx).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the content of this work.

References

- Collins, E.G. Meteorology of a Gliding Flight. Nature 1934, 133, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, B.N. Elevated cold sector severe thunder storms: A preliminary study. Natl. Weather Dig. 1995, 19, 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan, K.L.; Schultz, D.M.; Hales, J.E., Jr.; Corfidi, S.F.; Johns, R.H. A five-year climatology of elevated severe convective storms in the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. Weather Forecast. 2007, 22, 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.D.; Vavrek, J.R. An overview of thundersnow. Weather 2009, 64, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Sun, J.; Yang, X. A 7-yr climatology of the initiation, decay, and morphology of severe convective storms during the warm season over North China. Mon. Weather Rev. 2021, 149, 2599–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Y.; Yu, H.P.; Sheng, X.; Zhu, C.Q.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Ma, Y.X.; Gou, S. Mechanism analysis of a rare “thunder snow” process in semiarid area. Meteorol. Mon. 2020, 46, 1596–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, J.T.; Pearson, A.D. Proximity soundings for thunderstorms with snow. In Preprints, Seventh Conference on Severe Local Storms, Denver, CO, USA, 15–17 October 1973; American Meteorological Society: Kansas City, MO, USA, 1971; pp. 118–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chilingarian, A.; Sargsyan, B.; Zazyan, M. An enormous increase in atmospheric positron flux during a summer thunderstorm on Mount Aragats. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 222, 111819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ma, Y.; Liu, M.; Huang, T.; Xin, G.; Zhuang, B. Research on Relay Protection and Security Automatic Equipment Based on the Last Decade of Big Data. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2276, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steeneveld, G.; Peerlings, E.E. Mesoscale Model Simulation of a Severe Summer Thunderstorm in The Netherlands: Performance and Uncertainty Assessment for Parameterised and Resolved Convection. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Qie, X.; Peng, L.; Li, W. Charge structure of a summer thunderstorm in North China: Simulation using a Regional Atmospheric Model System. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2014, 31, 1022–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rickenbach, T. Seasonal Changes of Extremes in Isolated and Mesoscale Precipitation for the Southeastern United States. Atmosphere 2018, 9, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Miao, A.; Wang, H. Cloud image characteristics and maintaining mechanism of a squall line in autumn in Shanxi Province. J. Arid Meteorol. 2019, 37, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, V.; Soysal, E.L.; Kara, Y. Statistical analysis of thundersnow events and ERA5-based convective environments across Türkiye. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 3293–3312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, V.; Lupo, A.R.; Fox, N.I.; Deniz, A. A long-term analysis of thundersnow events over the Marmara Region, Turkey. Nat. Hazards 2022, 114, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacGorman, D.R.; Rust, W.D. The Electrical Nature of Storms; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; p. 422. [Google Scholar]

- Bech, J.; Pineda, N.; Rigo, T.; Aran, M. Remote sensing analysis of a mediterranean thundersnow and low altitude heavy snowfall event. Atmos. Res. 2013, 123, 305–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolif Neto, G.; Market, P.S.; Pezza, A.B.; Morales Rodriguez, C.A.; Calvetti, L.; da Silva Dias, P.L.; Escobar, G.C.J. Thundersnow in Brazil: A case study of 22 July 2013. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2016, 17, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, W.; Cao, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Y. A 10-Year Thundersnow Climatology over China. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, E2022GL100734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuart, N.A. Multi-dimensional analysis of an extreme thundersnow event during the 30 December 2000 snowstorm. In Proceedings of the 18th Conference on Weather Analysis and Forecasting, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 1 August 2001; American Meteorological Society: New York, NY, USA, 2001; Volume 18, pp. 223–226. [Google Scholar]

- Mäkelä, A.; Saltikoff, E.; Julkunen, J.; Juga, I.; Gregow, E.; Niemelä, S. Cold-season thunderstorms in Fin land and their effect on aviation safety. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2013, 94, 847–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumjian, M.R.; Dierling, W. Analysis of thundersnow storms over northern Colorado. Weather Forecast. 2015, 30, 1469–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Means, L.L. On thunderstorm forecasting in the central united states. Mon. Weather Rev. 1952, 80, 165–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, B.R. Thundertorms above frontal sufaes in eirnoments without positive CAPE: Part I: Aclimatology. Mon. Weather Rev. 1990, 1189, 1103–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, B.R. Thunderstorms above frontal surfaces in environments without positive CAPE: Part II: Organization and instability mechanisms. Mon. Weather Rev. 1990, 118, 1123–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.J.; Roberts, D.R. Summary of convective storm initiation and evolution during IHOP: Observational and modeling perspective. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2016, 134, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market, P.; Grempler, K.; Sumrall, P.; Henson, C. Analysis of Severe Elevated Thunderstorms over Frontal Surfaces Using DCIN and DCAPE. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, L.; Wu, L.; Xi, L. Diagnosis of the Frontogenesis And Instabilities in Two Continuous Autumn Torrential Rain Days in Henan Province. Meteorol. Mon. 2022, 48, 1101–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Zhou, X.G.; Wang, X.M. Climatic Statistical Analysis of Cold Season Elevated Convection Characteristics in the North China Region of China. Meteorol. Mon. 2018, 44, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.N.; Zhang, Z.H.; Xia, J.D. Classification and Cause Analysis of “Thundersnow” Event in Shandong. Meteorol. Mon. 2019, 45, 1075–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, D.M.; Zhang, L.N.; Wang, X.M. Analysis of a High-altitude Thunderstorm Weather Process in Shaanxi Province in Early Winter 2016. Meteorol. Mon. 2018, 44, 1404–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari, A.; Liu, C. Geographical distribution of thundersnow events and their properties from GPM Ku-band radar. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 2031–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market, P.S.; Halcomb, C.E.; Ebert, R.L. A climatology of thundersnow events over the contiguous United States. Weather Forecast. 2002, 17, 1290–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.R.; Tan, G.R.; Duan, W.; Yang, S.Y.; Jiang, Q.H. Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Regional Short-Term Heavy Precipitation Events in Yunnan Province and Classification of Weather System Characteristics. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 48, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; He, Q.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Z. An Analysis of the Instability Conditions and Water Vapor Transport Characteristics during a Typical Rainstorm in the Tarim Basin. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Qin, L. Analysis of the Ducted Gravity Waves Generated by Elevated Convection over Complex Terrain in China. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, K.; Turner, D.D.; Demoz, B.B. Nocturnal Convection Along a Trailing-End Cold Front: Insights from Ground-Based Remote Sensing Observations. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Liao, Y. Comparative Analysis of Summer Deep Convection Systems over the Tibetan Plateau and Sichuan Basin. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, J.; van den Heever, S.C. The impact of land surface properties on haboobs and dust lofting. J. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 79, 3195–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Song, P.; Zheng, F.; He, Z. Diagnostic Analysis of A Severe Regional Snowstorm Event in the Early Winter of 2016 in Henan Province, China. Chin. J. Atmos. Sci. 2020, 44, 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harkema, S.S.; Carey, L.D.; Schultz, C.J.; Mansell, E.R.; Berndt, E.B.; Fierro, A.O.; Matsui, T. Electrification within wintertime stratiform regions sampled during the 2020/2022 NASA IMPACTS field campaign. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2023JD038708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Álvarez, J.C.; Pérez-Alarcón, A.; Eiras-Barca, J.; Ramos, A.M.; Rahimi-Esfarjani, S.; Nieto, R.; Gimeno, L. Changes in moisture sources of atmospheric rivers landfalling the Iberian Peninsula with WRF-FLEXPART. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2023, 128, e2022JD037612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, S.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, Y.; Liu, Y. Impact of ice multiplication on the cloud electrification of a cold-season thunderstorm: A numerical case study. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2024, 24, 5989–6010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, S.M.; Bruning, E.C.; Chmielewski, V.C.; Stano, G.; Trostel, J.; Calhoun, K.M.; Jesmonth, K.R.; Lamsma, B.; Lang, T.; Laurinaitis, S.; et al. Winter lightning to the lee of Lake Ontario: The Lake-Effect Electrification (LEE) field campaign. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2024, 105, E2026–E2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.