An Air-Quality-Based Analysis of NO, NO2, and O3 at a Suburban Mediterranean Site

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

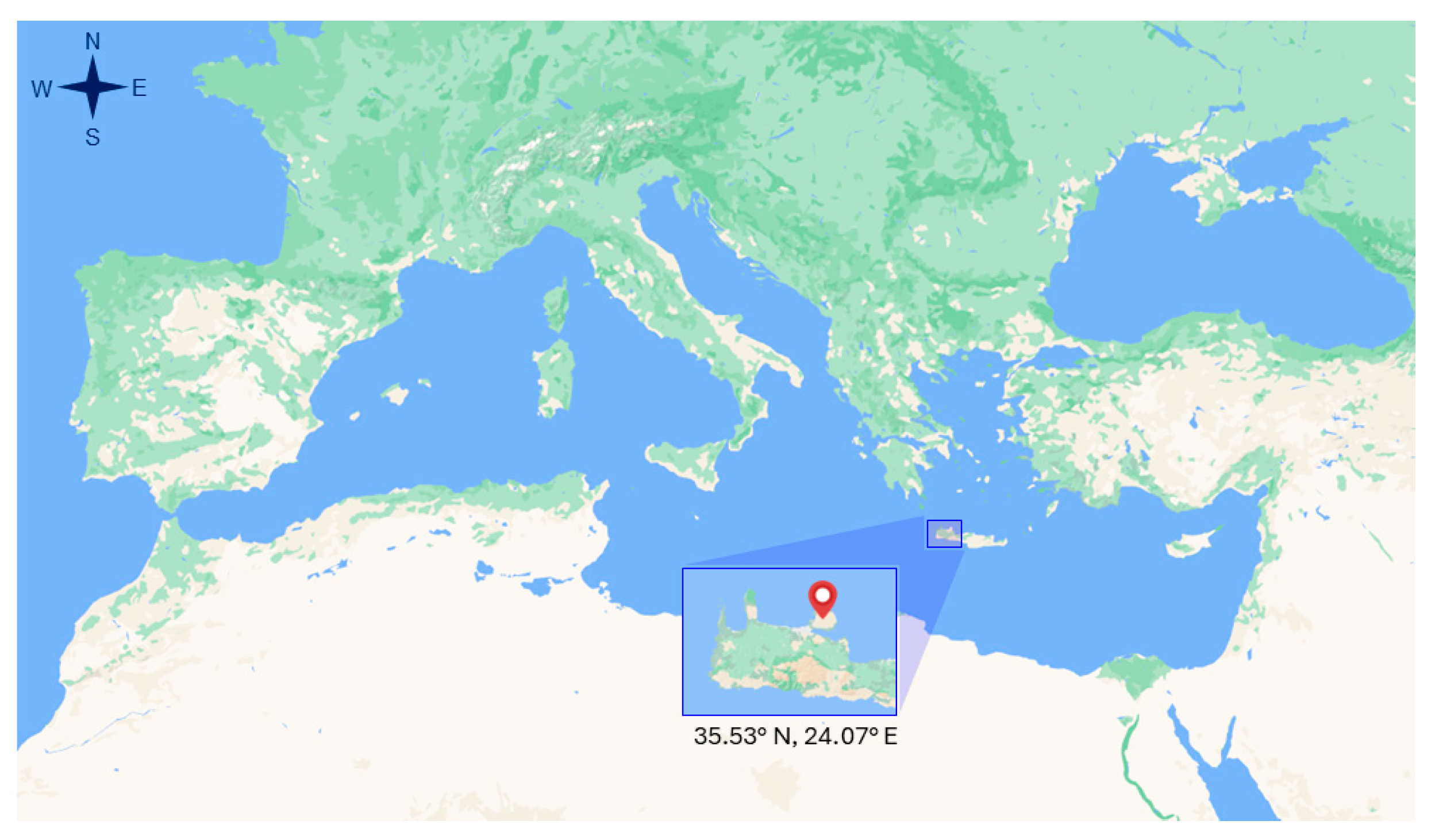

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Sampling and Instrumentation

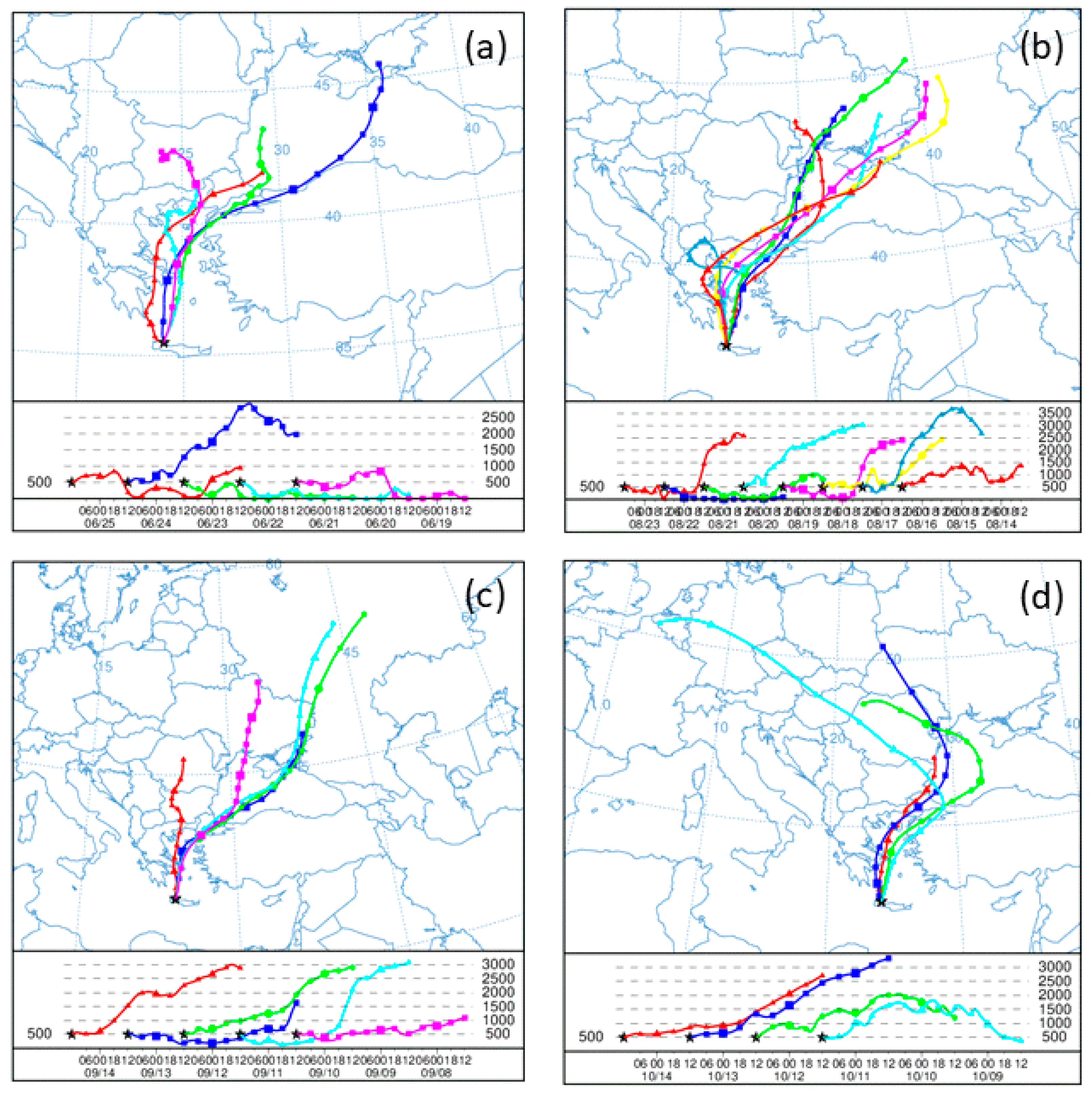

2.3. HYSPLIT Simulations

3. Results and Discussion

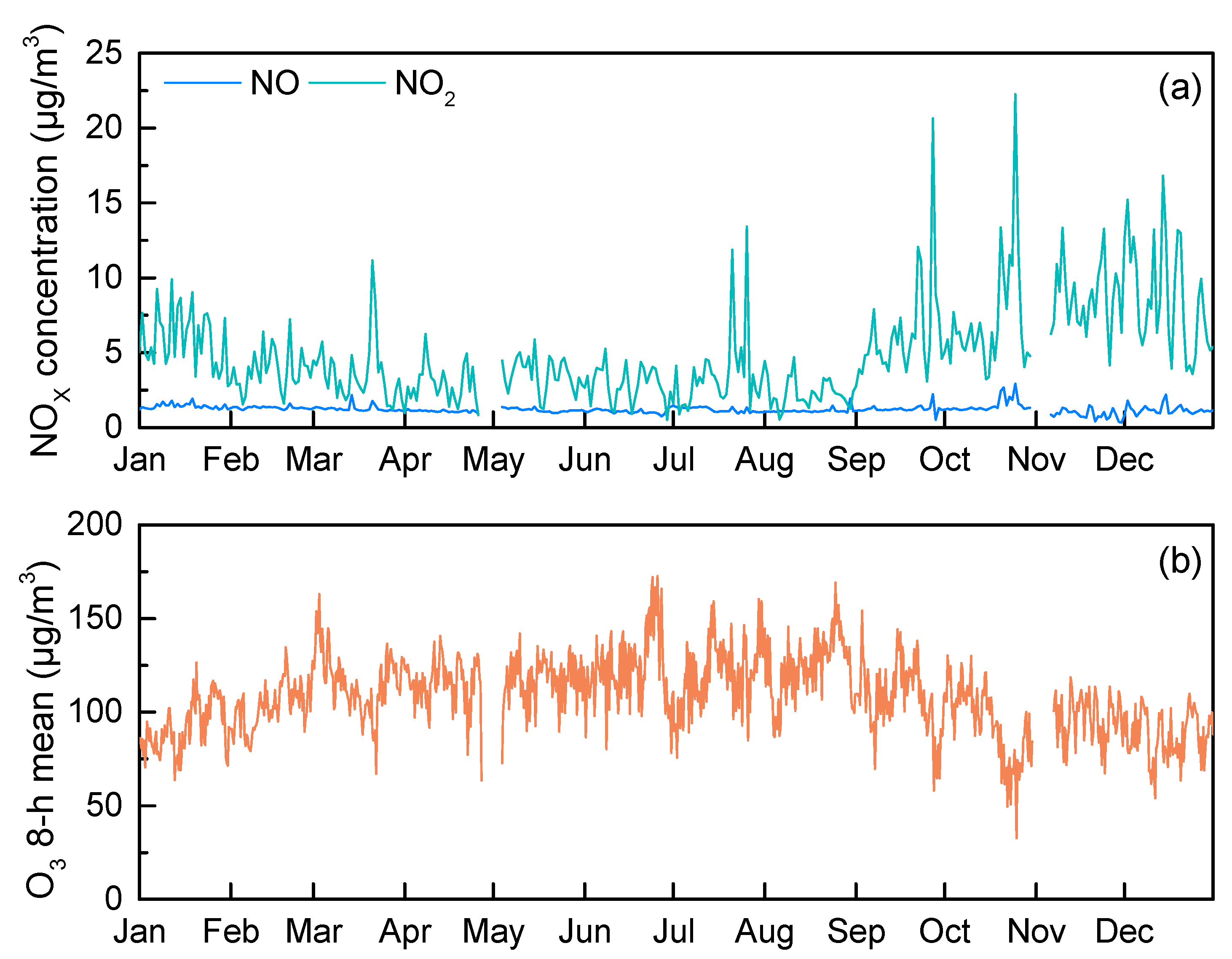

3.1. Timeseries

3.2. Comparison with EU Air Quality Standards

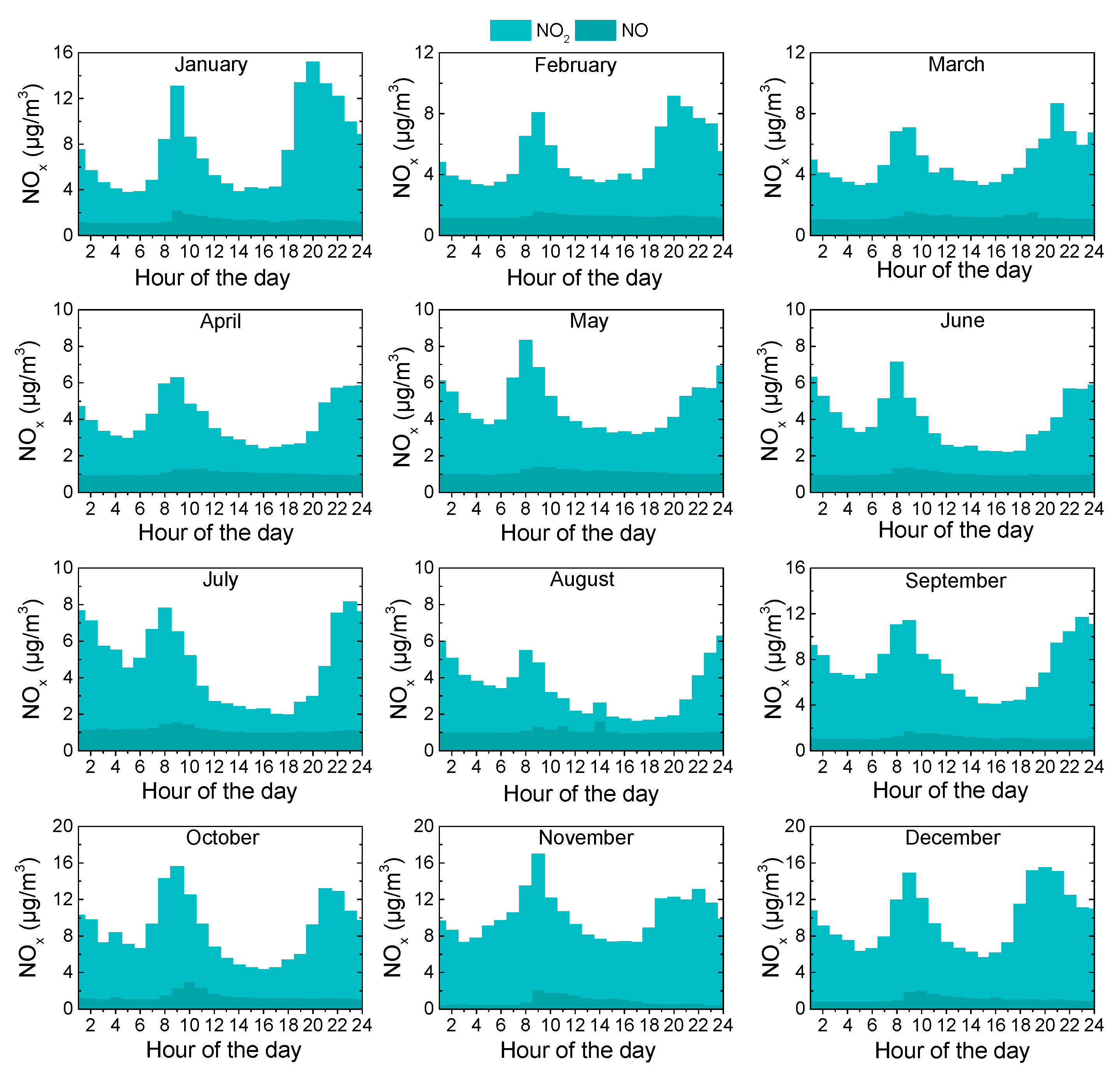

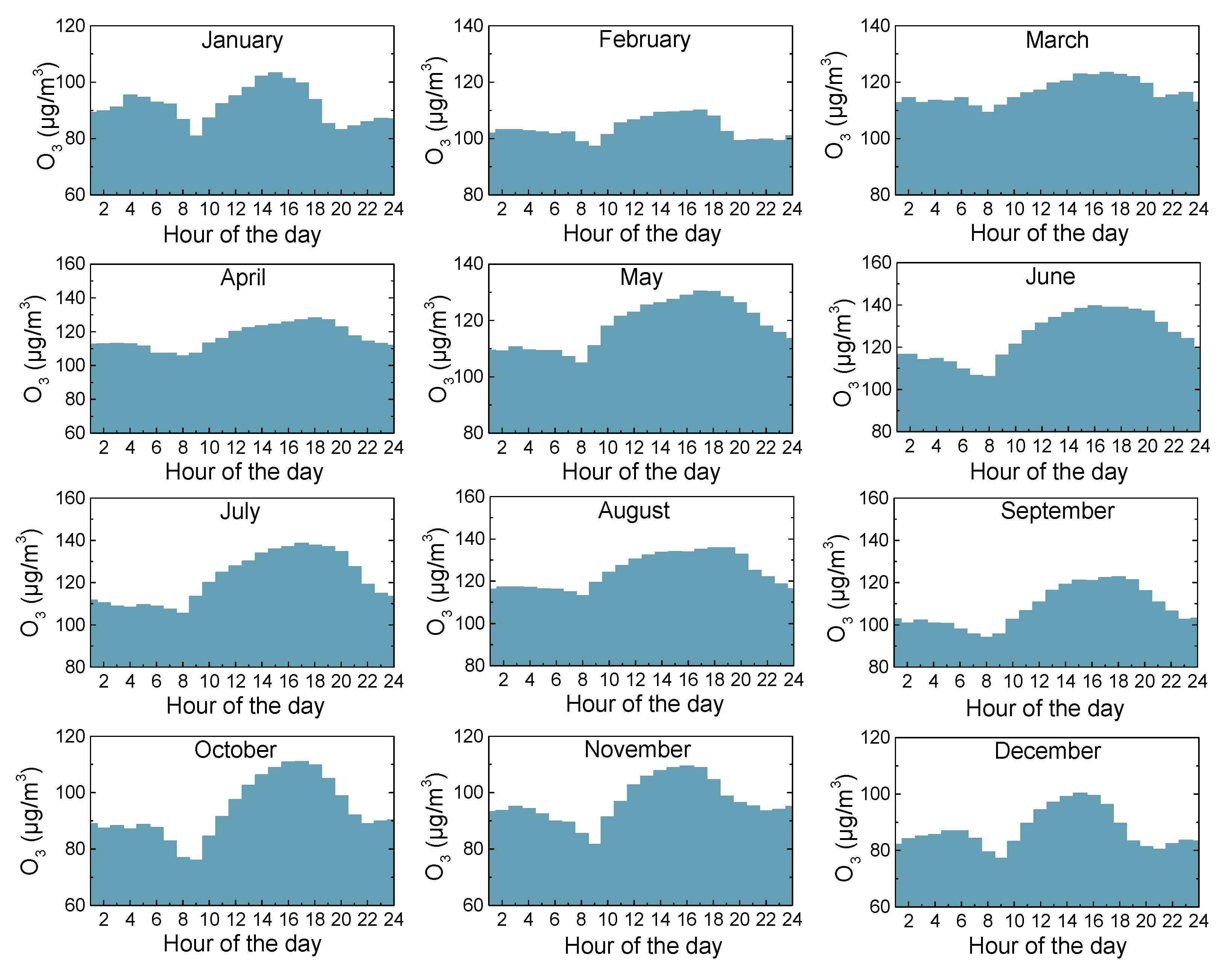

3.3. Diurnal Variations

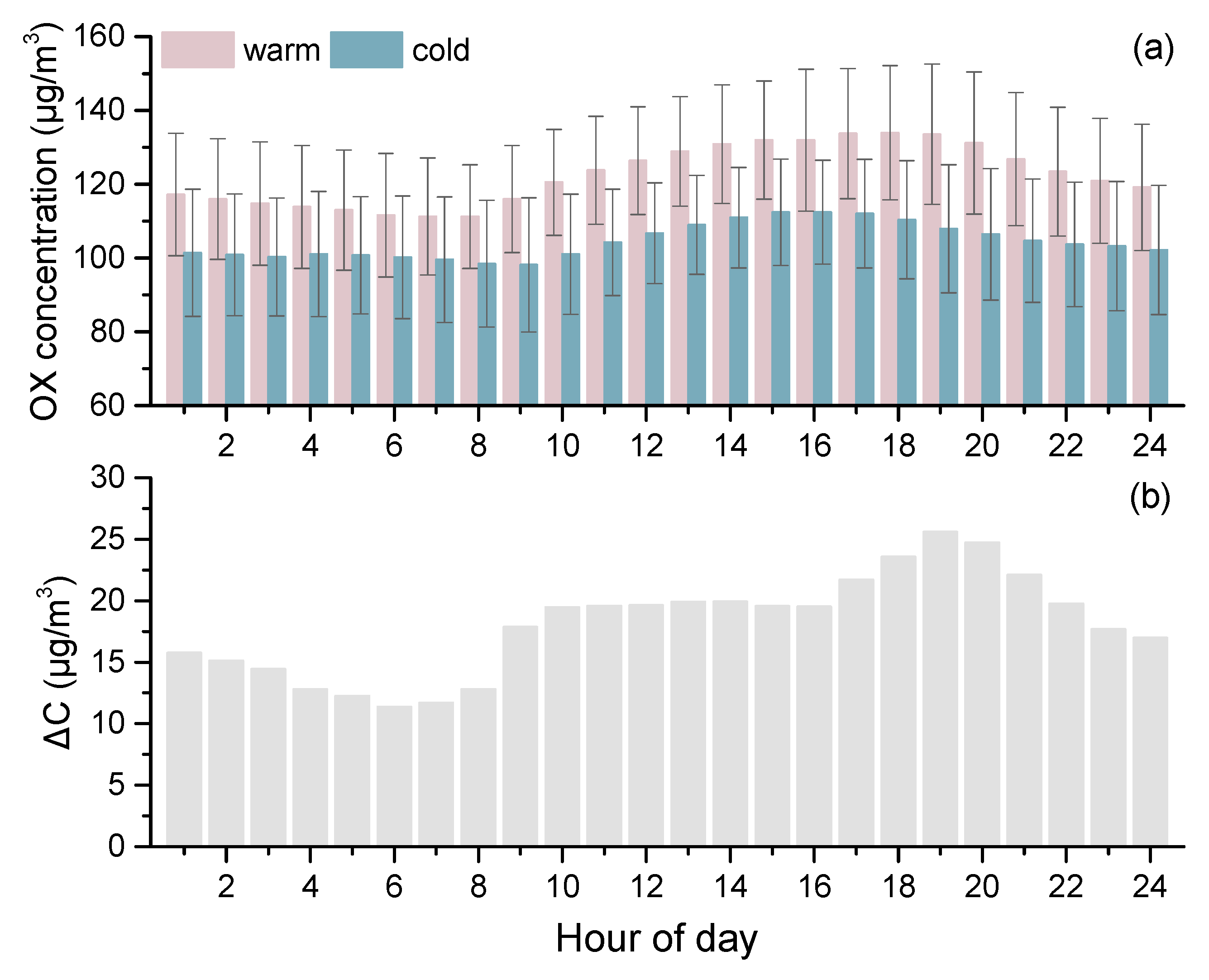

3.4. O3, NO, and NO2 Relationships

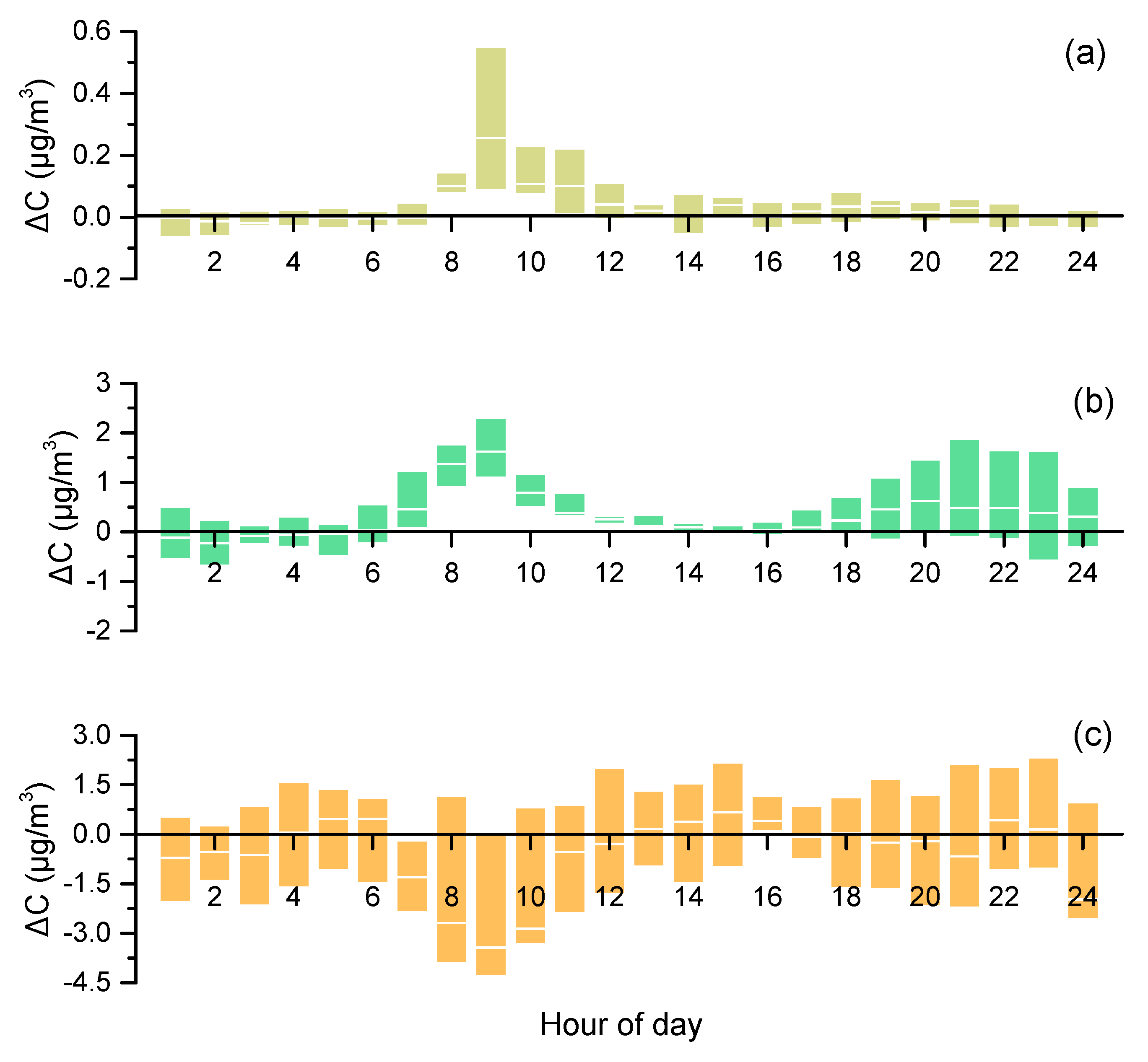

3.5. Weekdays vs. Weekends

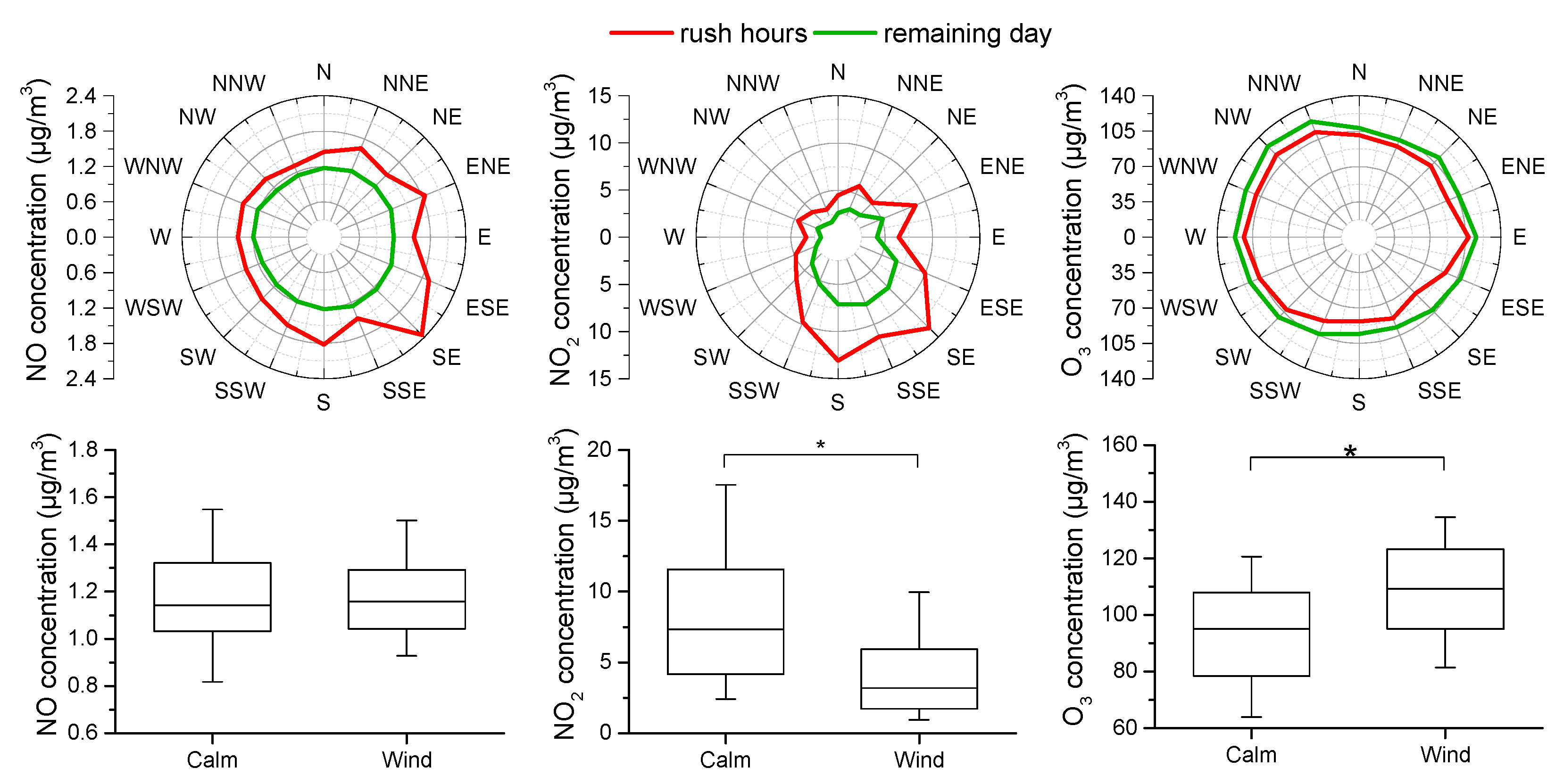

3.6. Impact of Ambient Conditions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Tan, X.; Fang, C. Analysis of NOx Pollution Characteristics in the Atmospheric Environment in Changchun City. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarghamipour, M.; Malakooti, H.; Bordbar, M.H. Spatio-temporal Analysis of the factors affecting NOx concentration during the evaluation cycle of high pollution episodes in Tehran metropolitan. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2024, 15, 102177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jian, H.-M.; Liu, C.-Y.; Gong, J.-C.; Li, P.-F.; Yang, G.-P. Distribution and influencing factors of atmospheric nitrogen oxides (NOx) over the east coast of China in spring: Indication of the sea as a sink of the atmospheric NOx. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 200, 116095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhong, X.; Li, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, K. Variation characteristics of acid rain in Zhuzhou, Central China over the period 2011–2020. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 138, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesterberg, T.W.; Bunn, W.B.; McClellan, R.O.; Hamade, A.K.; Long, C.M.; Valberg, P.A. Critical review of the human data on short-term nitrogen dioxide (NO2) exposures: Evidence for NO2 no-effect levels. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2009, 39, 743–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Li, M.; Guo, C.; Requia, W.J.; Sakhvidi, M.J.Z.; Lin, K.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Cao, P.; Yang, L.; et al. Associations of long-term exposure to nitrogen oxides with all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, S.S.; Idoudi, S.; Alhamdan, N.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Surkatti, R.; Amhamed, A.; Alrebei, O.F. Comprehensive review of health impacts of the exposure to nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon dioxide (CO2), and particulate matter (PM). J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2025, 19, 100771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Jacob, D.J.; Liao, H.; Kuk, S.K. Ozone pollution in the North China Plain spreading into the late-winter haze season. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2015797118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Tang, M.-X.; He, L.; Li, J.-H.; Hong, Y.; He, L.-Y.; Huang, X.-F. Unveiling the HONO Offsetting Effect: Rethinking NOx Emission Controls during Urban Ozone Pollution Episodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 22050–22059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monks, P.S.; Archibald, A.T.; Colette, A.; Cooper, O.; Coyle, M.; Derwent, R.; Fowler, D.; Granier, C.; Law, K.S.; Mills, G.E.; et al. Tropospheric ozone and its precursors from the urban to the global scale: From air quality to short-lived climate forcer. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 8889–8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-Y.; Kim, E.; Kim, W.J. Health Effects of Ozone on Respiratory Diseases. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2020, 83, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; You, Z.; Liao, C.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H. Health effects associated with ozone in China: A systematic review. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 367, 125642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vongelis, P.; Koulouris, N.G.; Bakakos, P.; Rovina, N. Air Pollution and Effects of Tropospheric Ozone (O3) on Public Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofanelli, P.; Bonasoni, P. Background ozone in the southern Europe and Mediterranean area: Influence of the transport processes. Environ. Pollut. 2009, 157, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Dahiya, A.; Kumar, N. Investigation into relationships among NO, NO2, NOx, O3, and CO at an urban background site in Delhi, India. Atmos. Res. 2015, 157, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.; Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; He, M.; Xu, N.; Zhang, J.; Qian, F.; Feng, J.; Xiao, H. Characteristics of surface ozone and nitrogen oxides at urban, suburban and rural sites in Ningbo, China. Atmos. Res. 2017, 187, 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasparoglu, S.; Incecik, S.; Topcu, S. Spatial and temporal variation of O3, NO and NO2 concentrations at rural and urban sites in Marmara Region of Turkey. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2018, 9, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravina, M.; Caramitti, G.; Panepinto, D.; Zanetti, M. Air quality and photochemical reactions: Analysis of NOx and NO2 concentrations in the urban area of Turin, Italy. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2022, 15, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaney, A.M.; Cryer, D.J.; Nicholl, E.J.; Seaskins, P.W. NO and NO2 interconversion downwind of two different line sources in suburban environments. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 5863–5871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkonyan, A.; Kuttler, W. Long-term analysis of NO, NO2 and O3 concentrations in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Atmos. Environ. 2012, 60, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2024/1760 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on Corporate Sustainability due Diligence and Amending Directive (EU) 2019/1937 and Regulation (EU) 2023/2859. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2024/1760/oj/eng (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines. Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; License CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp, L.J.; Jenkin, M.E. Analysis of the relationship between ambient levels of O3, NO2 and NO as a function of NOx in the UK. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 35, 6391–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Shin, J.Y.; Jusino-Atresino, R.; Go, Y. Relationships among the springtime ground–level NOx, O3 and NO3 in the vicinity of highways in the US East Coast. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2011, 2, 374–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, A.; Khorsandi, B.L.; Alavi Moghaddam, R.A. Long-term analysis of oxidant (OX = O3 + NO2) and its local and regional levels in Tehran, Iran, a high NOx-saturated condition. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopanakis, I.; Mammi-Galani, E.; Pentari, D.; Glytsos, T.; Lazaridis, M. Ambient Particulate Matter Concentration Levels and their Origin During Dust Event Episodes in the Eastern Mediterranean. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2018, 2, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopanakis, Ι.; Chatoutsidou, S.E.; Glytsos, T.; Lazaridis, M. Impact from local sources and variability of fine particle number concentration in a coastal sub-urban site. Atmos. Res. 2018, 213, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatoutsidou, S.E.; Lazaridis, M. Mass concentrations and elemental analysis of PM2.5 and PM10 in a coastal Mediterranean site: A holistic approach to identify contributing sources and varying factors. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 838, 155980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatoutsidou, S.E.; Lazaridis, M. Investigating the role of photochemistry and impact of regional and local contributions on gaseous pollutant concentrations (NO, NO2, O3, CO, and SO2) at urban and suburban sites. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2024, 15, 102322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagouvardos, K.; Kotroni, V.; Bezes, A.; Koletsis, I.; Kopania, T.; Lykoudis, S.; Mazarakis, N.; Papagiannaki, K.; Vougioukas, S. The automatic weather stations NOANN network of the National Observatory of Athens: Operation and database. Geosci. Data J. 2017, 4, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Xu, X.; Cheng, X.; Xu, X.; Qu, X.; Zhu, W.; Ma, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y. Spatio-temporal variations in SO2 and NO2 emissions caused by heating over the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region constrained by an adaptive nudging method with OMI data. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salva, J.; Poništ, J.; Rasulov, O.; Schwarz, M.; Vanek, M.; Sečkár, M. The impact of heating systems scenarios on air pollution at selected residential zone: A case study using AERMOD dispersion model. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrish, D.D.; Galbally, I.E.; Lamar, J.-F.; Horowitz, L.; Shindell, D.T.; Oltmans, S.J.; Derwent, R.; Tanimoto, H.; Labuschagne, C.; Cupeiro, M. Seasonal cycles of O3 in the marine boundary layer: Observation and model simulation comparisons. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2015, 121, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conil, S.; Bergametti, G.; Langrene, L.; Lopez, M.; Masson, O.; Pallares, C.; Ramonet, M. Surface Ozone: Seasonal cycles, trends and events, a new perspective from the OPE station in France over the 2012–2023 period. EGUsphere 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudel, A.; Cooper, O.R.; Ancellet, G.; Barret, B.; Boynard, A.; Burrows, J.P.; Clerbaux, C.; Coheur, P.-F.; Cuesta, J.; Cuevas, E.; et al. Tropospheric Ozone Assessment Report: Present-day distribution and trends of tropospheric ozone relevant to climate and global atmospheric chemistry model evaluation. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2018, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouvarakis, G.; Vrekoussis, M.; Mhalopoulos, N.; Kourtidis, K.; Rappenglueck, B.; Gerasopoulos, E.; Zerefos, C. Spatial and temporal variability of tropospheric ozone (O3) in the boundary layer above the Aegean Sea (eastern Mediterranean). J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2000, 107, D18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabokas, P.; Hjorth, J.; Foret, G.; Dufour, G.; Eremenko, M.; Siour, G.; Cuesta, J.; Beekmann, M. An investigation on the origin of regional springtime ozone episodes in the western Mediterranean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 3905–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalabokas, P.D.; Cammas, J.-P.; Thouret, V.; Volz-Thomas, A.; Boulanger, D.; Repapis, C.C. Examination of the atmospheric conditions associated with high and low summer ozone levels in the lower troposphere over the easter Mediterranean. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 10339–10352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sicard, P.; Agathokleous, E.; De Marco, A.; Paoletti, E.; Calatayud, V. Urban population exposure to air pollution in Europe over the last decades. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2021, 33, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendrick, C.M.; Koonce, P.; George, L.A. Diurnal and seasonal variations of NO, NO2 and PM2.5 mass as a function of traffic volumes alongside an urban arterial. Atmos. Environ. 2015, 122, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carslaw, D.C.; Beevers, S.D.; Tate, J.E.; Westmoreland, E.J.; Williams, M.L. Recent evidence concerning higher NOx emissions from passenger cars and light duty vehicles. Atmos. Environ. 2011, 45, 7053–7063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Bian, H.; Feng, Y.; Liu, A.; Li, X.; Zeng, F.; Zhang, X. Analysis of the Relationship between O3, NO and NO2 in Tianjin, China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2011, 11, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, U.; Incecik, S.; Guler, M.; Tek, A.; Topcu, S.; Unal, Y.S.; Yenigun, O.; Kindap, T.; Odman, M.T.; Tayanc, M. Analysis of surface ozone and nitrogen oxides at urban, semi-rural and rural sites in Istanbul, Turkey. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 443, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancholi, P.; Kumar, A.; Bikundia, D.S.; Chourasiya, S. An observation of seasonal and diurnal behavior of O3–NOx relationships and local/regional oxidant (OX = O3 + NO2) levels at a semi-arid urban site of western India. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2018, 28, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Xin, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Liu, P.; He, X.; Mu, Y. Ambient volatile organic compounds in urban and industrial regions in Beijing: Characteristics, source apportionment, secondary transformation and health risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 855, 158873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wenxuan, C.; Liu, Y.; Song, M.; Tian, X.; Zou, Q.; Lou, W.; Zhang, W.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Insights into ozone pollution control in urban areas by decoupling meteorological factors based on machine learning. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 1749–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, T.; Wang, J.; Ma, J.; Gao, H.; Huang, T. The transition from a nitrogen oxides-limited regime to a volatile organic compounds-limited regime in the petrochemical industrialized Lanzhou City, China. Atmos. Res. 2022, 269, 106035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, R.; Sun, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, G.; Shen, Z. From sensitivity regimes to policy action: Evaluating EKMA curve effectiveness with WRF-Chem, OBM, and machine learning. Atmos. Environ. 2026, 365, 121689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.S.; Stutz, J. Nighttime radical observations and chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 6405–6447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Tonnesen, G.S.; Wang, Z. Weekend/Weekday Differences of Ozone, NOx, CO, VOCs, PM10 and the Light Scatter during Ozone Season in Southern California. Atmos. Environ. 2004, 38, 3069–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoder, M.I. Diurnal, seasonal and weekdays–weekends variations of ground level ozone concentrations in an urban area in greater Cairo. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 149, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Wasti, S.; Lee, T.; Li, W.; Zhou, S.; Flynn, J.; Sheesley, R.J.; Usenko, S.; Liu, F. Impacts of anthropogenic emissions and meteorology on spring ozone differences in San Antonio, Texas between 2017 and 2021. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 914, 169693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liao, H.; Li, J. Nighttime ozone excess days and the associated meteorological conditions in the North China Plain from 2015 to 2022. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 330, 120561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Limit Values | Threshold | Threshold | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 1 day | Calendar year | Information (1 h) | Alert (1 h) | |

| Value | 200 μg/m3 | 50 μg/m3 | 20 μg/m3 | 150 μg/m3 | 200 μg/m3 |

| NO2 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Maximum daily 8-h mean | Information (1 h) | Alert (1 h) | |||

| Value | 100 μg/m3 | 180 μg/m3 | 240 μg/m3 | ||

| O3 | 274 | 13 | - | ||

| Temperature | Relative Humidity | Wind Speed | Solar Radiation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.03 | 0.08 |

| NO2 | −0.21 | 0.24 | −0.37 | −0.31 |

| O3 | 0.48 | −0.48 | 0.23 | 0.42 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chatoutsidou, S.E.; Kordonouri, I.; Lazaridis, M. An Air-Quality-Based Analysis of NO, NO2, and O3 at a Suburban Mediterranean Site. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010007

Chatoutsidou SE, Kordonouri I, Lazaridis M. An Air-Quality-Based Analysis of NO, NO2, and O3 at a Suburban Mediterranean Site. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):7. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010007

Chicago/Turabian StyleChatoutsidou, Sofia Eirini, Iliana Kordonouri, and Mihalis Lazaridis. 2026. "An Air-Quality-Based Analysis of NO, NO2, and O3 at a Suburban Mediterranean Site" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010007

APA StyleChatoutsidou, S. E., Kordonouri, I., & Lazaridis, M. (2026). An Air-Quality-Based Analysis of NO, NO2, and O3 at a Suburban Mediterranean Site. Atmosphere, 17(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010007