Abstract

Near-field ionospheric total electron content records before and after the 15 January 2022 eruption of the Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha’apai submarine volcano were studied using GNSS total electron content data. The data started showing positive departures from the afternoon smooth decreasing trend ~1 h before the eruption. This anomaly is localized around the volcano, i.e., it decays as we go away from the volcano. The signature resembles the one that preceded the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake. However, a detailed investigation of ionospheric anomalies from a dense GNSS array in New Zealand showed a large-scale traveling ionospheric disturbance propagating toward Tonga, excited by a moderate geomagnetic storm on the previous day. This suggests that the anomaly around the volcano immediately before the eruption was caused by the arrival of this disturbance at Tonga just at the eruption time.

1. Introduction

Numerous reports have been published on the ionospheric anomalies caused by the volcanic explosivity index (VEI) 5 eruption of the submarine volcano Hunga-Tonga Hunga Ha’apai (HTHH) starting ~4:15 UT on 15 January 2022 [1]. They are based on total electron content (TEC) measurements from permanent global navigation satellite system (GNSS) stations. They discuss near-field phenomena such as the multiple arrivals of strong acoustic pulses reflecting the eruption sequence [2], formation of a large ionospheric hole [2,3], and atmospheric modes excited by the continuous eruption [4,5]. Observations with worldwide GNSS stations [6], together with tide gauges [7], revealed ionospheric signatures of passages of the Lamb wave (LW) in remote regions. Their repeated passages are studied by regional GNSS networks, such as in Japan [8,9], China [10], New Zealand [11], and Australia [12]. Mirror images of the anomalies propagating in northern Australia emerged in the northern hemisphere [13]. The occurrence of such conjugated anomalies is considered to have been caused by electric fields generated in the E region of the ionosphere [14]. So far, however, studies focused on the ionospheric changes prior to this large eruption are limited to that on the anomaly ~10 days before the eruption [15].

Heki [16] reported ionospheric electron enhancement starting ~40 min before the 2011 Mw9.0 Tohoku-oki earthquake, Northeast Japan. Three-dimensional tomography of this anomaly showed that a pair of positive and negative electron density anomalies emerged above the land area (i.e., not above the submarine fault) along the geomagnetic field [17]. This suggests surface positive electric charge responsible for the redistribution of ionospheric electrons. A detailed review is given in Heki [18].

Although volcanic eruptions and earthquakes are different phenomena, one may expect such precursory anomalies to occur in the ionosphere immediately before this exceptionally large eruption. Here, I look for pre-eruption ionospheric changes and study their origin.

2. TEC Changes on the Eruption Day

2.1. Data Processing

I obtained multi-GNSS raw data files of six ground stations (Figure 1) from NASA Crustal Dynamics Data Information System (CDDIS). These stations include the TONG station located in the main island of Tonga, close to HTHH (Figure 1) (eruption started ~16:30 in local solar time there). In order to separate spatial and temporal changes in TEC, I used satellites with geostationary orbits (two from BDS, C1, C4 and one from QZSS, J7) and quasi-zenith orbits (three from QZSS, J1-3). I did not use satellites with conventional half-sidereal-day orbital periods (e.g., GPS, Galileo, GLONASS) because they move rapidly in the sky and their TEC changes include both spatial and temporal changes. Figure 1 shows the ground tracks of ionospheric piercing points (IPPs) assuming a thin ionosphere as high as 300 km. Their geostationary satellites do not show recognizable “tracks” and quasi-zenith orbit satellites only show small movements during the 1.25 h period (only J2 shows a relatively long track). These satellites remain above these stations, with elevations higher than 45 degrees, and we could track them nearly continuously (Figure 2).

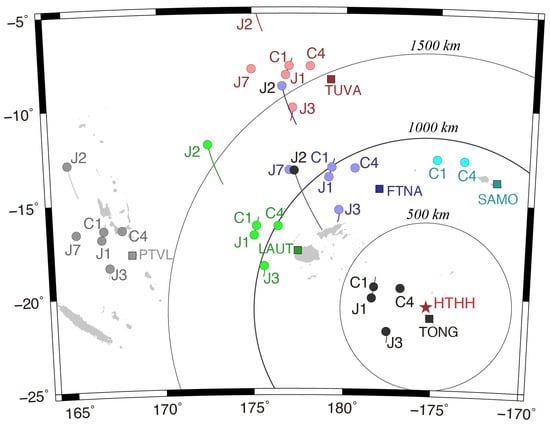

Figure 1.

I analyzed ionospheric records observed at six stations (squares) located near the HTHH volcano (red star) using two geostationary satellites of BDS (C1, C4), three quasi-zenith orbit satellites (J1, J2, J3) and one geostationary satellite (J7) of QZSS. Circles indicate sub-ionospheric points for these satellite–station pairs calculated assuming a thin ionosphere at 300 km altitude. Station positions and their IPP ground tracks are drawn using similar colors. Curves indicate IPP tracks during the period from 3.0 UT to the eruption time at 4.25 UT (such “tracks” are almost invisible for geostationary satellites). Station SAMO did not track QZSS, and stations TONG and LAUT did not track J7.

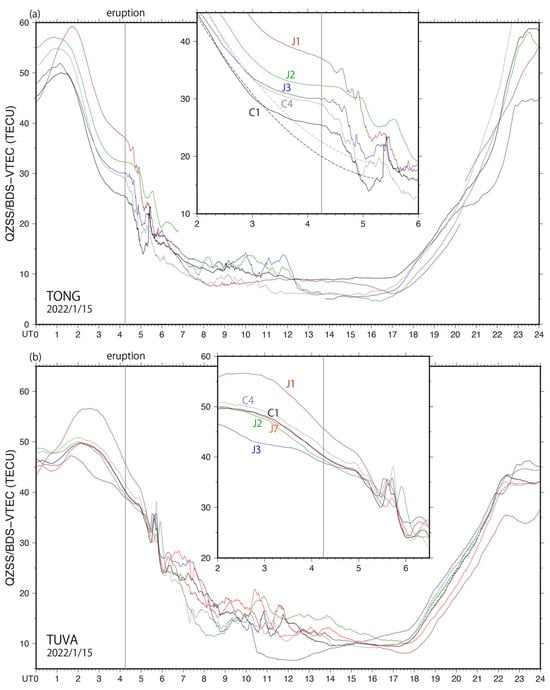

Figure 2.

(a) VTEC on 15 January 2022 at the TONG station, located close to HTHH as functions of time in UT (h). Data from different satellites are distinguished by colors. The inset shows the close-up view of the period 2–6 UT. The eruption start time (4:15) is indicated by a vertical gray line. In addition to disturbances caused by acoustic waves, internal gravity waves, electron depletion, and atmospheric modes (harmonic oscillations), we recognize the temporary departure of TEC from smooth afternoon decay starting ~1 h before the eruption. Dashed curves for C1 and C4 VTEC data (inset) are the “reference curves” derived by fitting these data using degree-two polynomials for 2:00–5:12, excluding 3:15–4:28 UT, affected by the anomalies. (b) VTEC at the TUVA station, located ~1500 km NW of HTHH. We recognize disturbances by acoustic waves and internal gravity waves, and harmonic oscillations reflecting atmospheric modes [5], but do not recognize temporary departure of TEC from smooth curves before the eruption as seen in TONG.

Figure 2a shows 24 h records of vertical TEC (VTEC) from these geostationary/quasi-zenith orbit satellites, C1, C4, J1, J2, J3 observed at the TONG station (J7 data not available at TONG). There, I removed the inter-frequency biases by minimizing the difference between the VTEC from individual satellites and those calculated using the global ionospheric map (GIM) downloaded from the University of Berne (ftp.aiub.unibe.ch/CODE/, accessed on 21 January 2022).

2.2. Anomalies Immediately Before the Eruption

In Figure 2a, we notice that the VTEC curves deviate from smoothly decreasing curves, i.e., they show positive “anomalies” starting ~1 h before the eruption. This signature resembles those before the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake in two points. The first point is that it started about 1 h before the event and showed positive departure of TEC from smoothly decreasing curves. The second point is its spatial decay. In the Tohoku-oki case, the anomaly appeared near the fault and decayed with the distance. Figure 2b shows that such anomalies cannot be seen at TUVA, ~1500 km from HTHH. Figure 3 compares the VTEC curves using pairs of six satellites and six stations having various distances from the volcano.

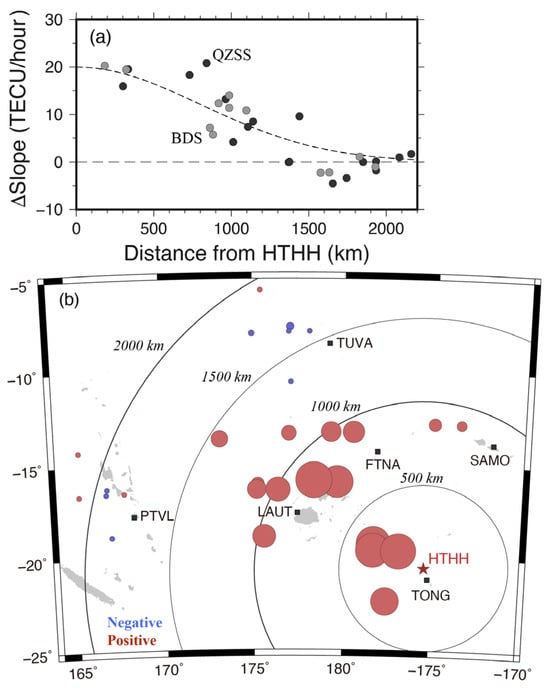

Figure 3.

VTEC curves during the two-hour period preceding the eruption (2.25–4.25 UT) for all available pairs of six GNSS satellites and stations (colors correspond to stations, Figure 1). Pairs with IPPs farther from HTHH are displayed more to the right (distances are shown as separation of the left tip of the curves from the left axis). Positive gentle bending is seen in curves close to HTHH, but not seen in those away from HTHH.

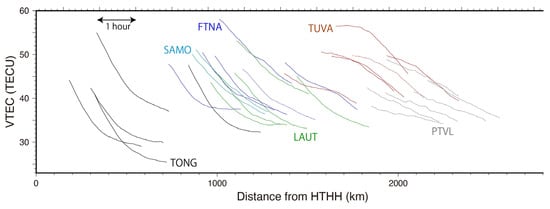

This is further illustrated in Figure 4. There, I quantified such bending as the difference in slopes immediately before the eruption from those before the start of the bending. This calculation is performed by first fitting a degree three polynomial to the curve 2.25–4.25 UT and defined the anomaly as the increase in the slopes between 2.25 and 4.25. For the upward-concave curves (e.g., those from TUVA, Figure 3), I took the reference slope at 3.25 UT to avoid large negative slope change. Such anomalies were plotted as a function of the distance from HTHH in Figure 4a, and on the map in Figure 4b. These figures suggest that such positive bending occurred in a region close to the volcano and decay with distance. These features give us the impression that they are precursory changes in the eruption.

Figure 4.

“Precursory” bending of VTEC is quantified as the difference between slopes immediately before the eruption and those before the onsets of the bending (either 1 or 2 h before the eruption). Such ΔSlopes were compared with distance from HTHH (a) or plotted on the map with circles with radii proportional to ΔSlopes (b).

3. Influence of the Geomagnetic Storm

If this positive TEC anomaly is a precursor of the HTHH eruption, it has a serious inconsistency with the mechanism proposed for earthquakes by Muafiry and Heki [17]. They found that the electron density anomaly before the 2011 Tohoku-oki earthquake appeared only above land, which lead to the hypothesis that surface electric charges are responsible for the electron redistribution. However, HTHH is a submarine volcano without large landmasses in the vicinity. Figure 4 shows that the observed anomaly is localized around HTHH. This figure also shows that the anomalies are as strong around the Fiji Islands (LAUT) as above HTHH. This suggests that the anomaly may have a structure elongated in NW-SE, which is inconsistent with the idea that HTHH is the unique source of the anomalies.

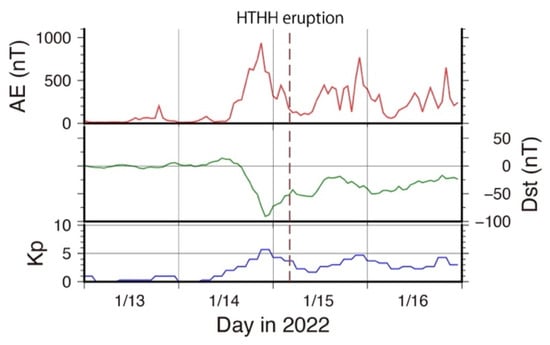

Such temporary TEC increases with timescales of 0.5–1.0 h often occur as large-scale traveling ionospheric disturbances (LSTIDs). They are internal gravity waves propagating toward the equator from the auroral oval. There, strong electric currents heat up the atmosphere and excite such waves. The statistical properties of LSTIDs are studied in Tsugawa et al. [19], and Cherniak and Zakharenkova [20] report worldwide observations of LSTIDs during a strong geomagnetic storm. The 2022 HTHH eruption occurred during a moderate geomagnetic storm, and the auroral electrojet (AE) indices show high auroral activities over a period lasting a half day just before the eruption (Figure 5). Next, I will confirm if the transient TEC increase just before the HTHH eruption is related to LSTID activities.

Figure 5.

Hourly values of the AE index, Dst index, and Kp index over the period 13–16 January 2022 after NASA/Omniweb (omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov, accessed on 25 June 2025).

Unfortunately, there are no GNSS stations south of HTHH within 1500 km. However, a dense network of GNSS stations is operational in New Zealand over the distance range 2000–3000 km from HTHH and records various ionospheric signatures related to the HTHH eruption [8]. The TEC data from these stations would also be useful in detecting LSTID signatures several hours before the eruption. I downloaded the data from ~40 stations and analyzed the VTEC data to look for LSTID signatures on 15 January 2022.

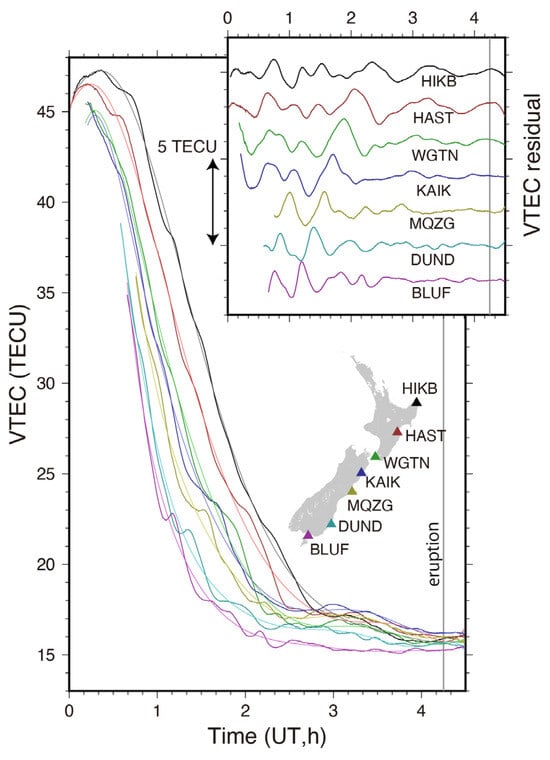

The New Zealand stations did not track BDS/QZSS, and I analyzed the data from GPS. Figure 6 shows that the VTEC of GPS Sat#13 (G13) rapidly decreased from its peak values at noon around 0 UT. We can recognize significant fluctuations overlie the smooth curves. The largest positive peak lies within the time range 1–3 UT, i.e., a few hours before the HTHH eruption. The Figure 6 inset shows the residuals of VTEC from best-fit polynomials. The data clearly indicate northward migration of the anomalies. It took ~1 h for the anomaly to travel from the southernmost to the northernmost stations (apart by ~800 km). This apparent speed of ~0.2 km/s is reduced to ~0.1 km/s by considering the G13 movements. Considering its typical properties (period, speed, azimuth of wavefront and propagation) and the enhancement of the AE index (Figure 5), this signature would indicate the propagation of LSTIDs generated in the auroral oval south of New Zealand.

Figure 6.

LSTID signature during 1–3 UT in New Zealand as seen in the VTEC records (G13) at 7 GNSS stations distributed NE-SW in New Zealand. Wavy fluctuations with a period of ~1 h propagate from south to north. The colors of the time series correspond to those of the sites shown on the map. The inset shows the residual time series of VTEC from best-fit degree 8 polynomials.

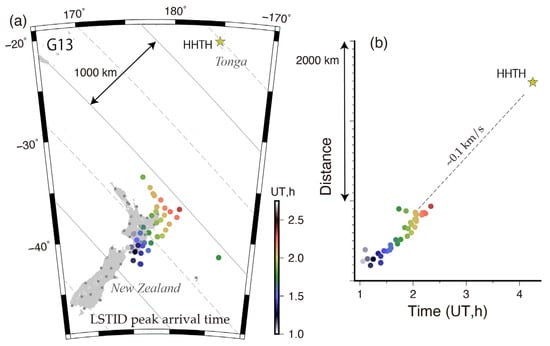

If this LSTID keeps traveling in the same direction at a constant velocity, when will it arrive at HTHH? Figure 7 shows that the LSTID wavefront strikes NW-SE and its largest positive peak would arrive at HTHH just around the eruption time (4:15 UT). This strongly suggests that the temporary enhancement of VTEC at the GNSS stations around the HTHH volcano immediately before the eruption is not a precursor of the eruption but indicates the arrival of this LSTID. This also explains the similar TEC enhancement at the LAUT station, which is on the same wavefront of this LSTID as TONG. The amplitudes of the LSTID signatures in Figure 6 are smaller than those in Figure 2a. This is not surprising because LSTIDs during disturbed times often grow in amplitude as they propagate [19].

Figure 7.

(a) The peak arrival times of the LSTID propagating in New Zealand from SW to NE (Figure 6) are shown as colors onto the IPP positions at the peak times (i.e., times calculated for IPPs are different from station to station). Gray dots on the map show the GNSS station positions. I assumed that the LSTID has a wavefront extending NW-SE and propagates toward NE. (b) The peak arrival times are plotted as the function of distance in the SW-NE direction. If the LSTID continues traveling at the speed of ~0.1 km/s, it will arrive at the HTHH volcano when the eruption started (4:15 UT).

4. Conclusions

It has been pointed out that preseismic TEC anomalies often resemble LSTID signatures in their intensity, spatial extent, and timescale [21]. Heki and Enomoto [21,22] showed that LSTIDs can be distinguished from preseismic anomalies by their movements toward the equator. In the present study, I have demonstrated a new effective approach to distinguish them, i.e., analyzing the ionospheric data in the “upstream” region of LSTIDs.

I showed that the transient positive anomaly immediately before the January 2022 HTHH eruption is not the precursor of the eruption but is LSTID propagating from the auroral oval around the south pole. The method proposed here might serve as a standard to confirm LSTID origins of such transient anomalies. This study has implications as listed below.

- (1)

- It provides a model case to examine if a certain temporary TEC enhancement is caused by space weather. This study demonstrates that a dense GNSS network on the upstream side (southward in the present case) is useful.

- (2)

- The existence of a temporary TEC enhancement matters in inferring the amount of the TEC drop after the eruption (ionospheric hole formation). There is no such concern if one compares VTEC after the eruption with those on other days [1]. However, if one uses the VTEC value immediately before the eruption to discuss its post-eruption drop, temporary increase due to LSTIDs would let us overestimate the drop.

Funding

The author was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, President’s International Fellowship Initiative (Grant number 2022VEA0014) during his stay in China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The GNSS raw data files were downloaded from CDDIS, https://cddis.nasa.gov, accessed on 20 January 2022. The raw GNSS data from the New Zealand network are available from www.linz.govt.nz/products-services/geodetic/positionz (doi:10.21420/RXKE-AZ44, 1 August 2022). The AE indices were downloaded from NASA Omniweb, https://omniweb.gsfc.nasa.gov, accessed on 25 June 2025. The Global Ionospheric Map was downloaded from the University of Berne, ftp.aiub.unibe.ch/CODE/, accessed on 21 January 2022.

Acknowledgments

I thank Shuanggen Jin, SHAO, for the discussions, and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Matoza, R.S.; Fee, D.; Assink, J.D.; Iezzi, A.M.; Green, D.N.; Kim, K.; Toney, L.; Lecocq, T.; Krishnamoorthy, S.; Lalande, J.-M.; et al. Atmospheric waves and global seismoacoustic observations of the January 2022 Hunga eruption, Tonga. Science 2022, 377, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astafyeva, E.; Maletckii, B.; Mikesell, T.D.; Munaibari, E.; Ravanelli, M.; Coisson, P.; Manta, F.; Rolland, L. The 15 January 2022 Hunga Tonga Eruption History as Inferred from Ionospheric Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Astafyeva, E.; Yue, X.; Ding, F.; Maletckii, B. The giant ionospheric depletion on 15 January 2022 around the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcanic eruption. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2022, 128, e2022JA030984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Soares, G.; Matzka, J. Geomagnetic detection of the atmospheric acoustic resonance at 3.8 mHz during the Hunga Tonga eruption event on 15 January 2022. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2022, 127, e2022JA030540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heki, K. Atmospheric resonant oscillations by the 2022 January 15 eruption of the Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha’apai volcano from GNSS-TEC observations. Geophys. J. Int. 2024, 236, 1840–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Themens, D.R.; Watson, C.; Žagar, N.; Vasylkevych, S.; Elvidge, S.; McCaffrey, A.; Prikryl, P.; Reid, B.; Wood, A.; Jayachandran, P.T. Global propagation of ionospheric disturbances associated with the 2022 Tonga volcanic eruption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravanelli, M.; Astafyeva, E.; Munaibari, E.; Rolland, L.; Mikesell, T.D. Ocean-ionosphere disturbances due to the 15 January 2022 Hunga-Tonga Hunga-Ha’apai eruption. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2022GL101465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heki, K. Ionospheric signatures of repeated passages of atmospheric waves by the 2022 Jan. 15 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption detected by QZSS-TEC observations in Japan. Earth Planets Space 2022, 74, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, S. Ionospheric disturbances observed over Japan following the eruption of Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai on 15 January 2022. Earth Planets Space 2022, 74, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Gao, Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.-Y. Ionospheric disturbances observed over China after 2022 January 15 Tonga volcano eruption. Geophys. J. Int. 2023, 235, 909–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muafiry, I.N.; Wijaya, D.D.; Meilano, I.; Heki, K. Diverse ionospheric disturbances by the 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai eruption observed by a dense GNSS array in New Zealand. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2023, 128, e2023JA031486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Xiong, M.; Wang, R.; Yao, Y.; Tang, F.; Chen, H.; Qiu, L. On the ionospheric disturbances in New Zealand and Australia following the eruption of the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano on 15 January 2022. Space Weather 2023, 21, e2022SW003294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Rajesh, P.K.; Lin, C.C.H.; Chou, M.; Liu, J.; Yue, J.; Hsiao, T.; Tsai, H.; Chao, H.; Kung, M. Rapid conjugate appearance of the giant ionospheric Lamb wave signatures in the northern hemisphere after Hunga-Tonga volcano eruptions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2022GL098222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinbori, A.; Otsuka, Y.; Sori, T.; Nishioka, M.; Perwitasari, S.; Tsuda, T.; Nishitani, N. Electromagnetic conjugacy of ionospheric disturbances after the 2022 Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcanic eruption as seen in GNSS-TEC and SuperDARN Hokkaido pair of radars observations. Earth Planets Space 2022, 74, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, D. Analysis of ionospheric anomalies before the Tonga volcanic eruption on 15 January 2022. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heki, K. Ionospheric electron enhancement preceding the 2011 Tohoku-Oki earthquake. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2011, 38, L17312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muafiry, I.N.; Heki, K. 3D tomography of the ionospheric anomalies immediately before and after the 2011 Tohoku-oki (Mw9.0) earthquake. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2020, 125, e2020JA27993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heki, K. Chapter 21: Ionospheric Disturbances Related to Earthquakes. In Ionospheric Dynamics and Applications; Geophys. Monograph; Huang, C., Lu, G., Zhang, Y., Paxton, L.J., Eds.; Wiley/American Geophysical Union: Malden, MA, USA, 2021; Volume 260, pp. 511–526. ISBN 978-1-119-50755-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, T.; Saito, A.; Otsuka, Y. statistical study of large-scale traveling ionospheric disturbances using the GPS network in Japan. J. Geophys. Res. 2004, 109, A06302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniak, I.; Zakharenkova, I.I. Large-scale traveling ionospheric disturbances origin and propagation: Case study of the December 2015 geomagnetic storm. Space Weather 2018, 16, 1377–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heki, K.; Enomoto, Y. Preseismic ionospheric electron enhancements revisited. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2013, 118, 6618–6626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heki, K.; Enomoto, Y. Mw dependence of preseismic ionospheric electron enhancements. J. Geophys. Res. Space Phys. 2015, 120, 6016–6018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.