Influence of Microclimate on Human Thermal and Visual Comfort in Urban Semi-Underground Spaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Site

2.1. Climatic Conditions

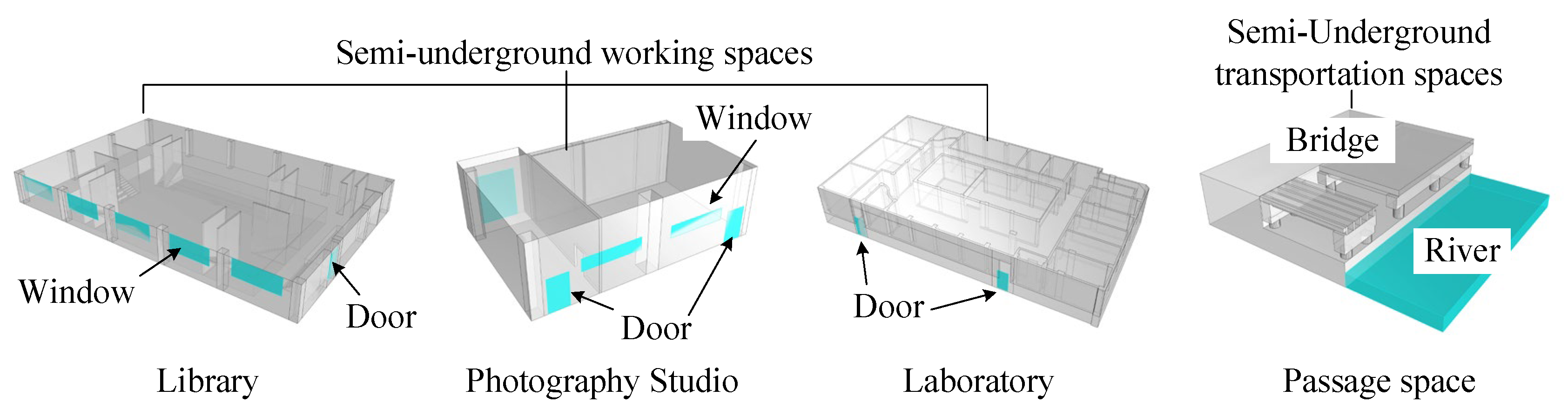

2.2. Site Information

3. Research Methods

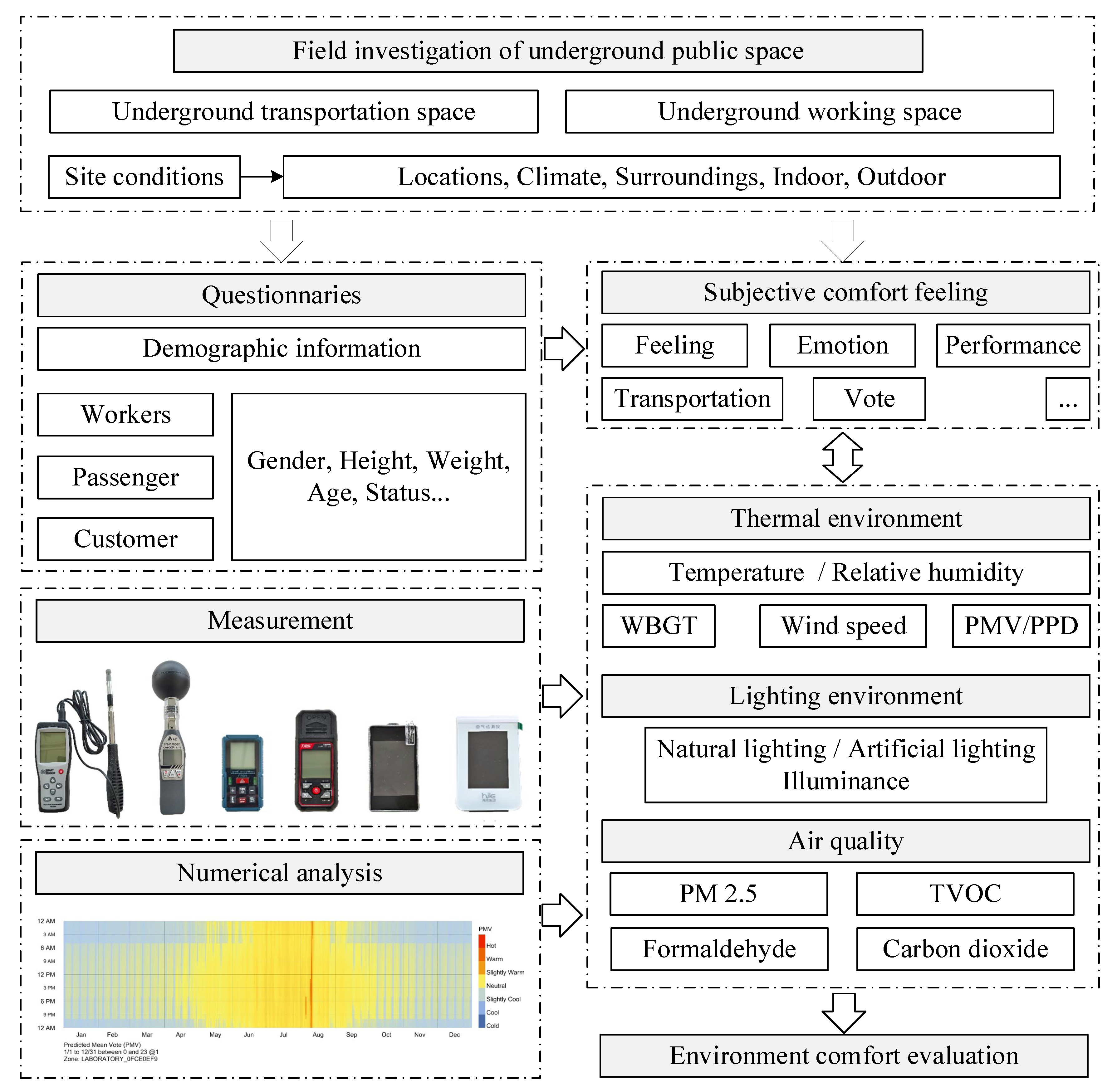

3.1. Methodology

3.2. Environment Measurements

3.2.1. Measurement Contents

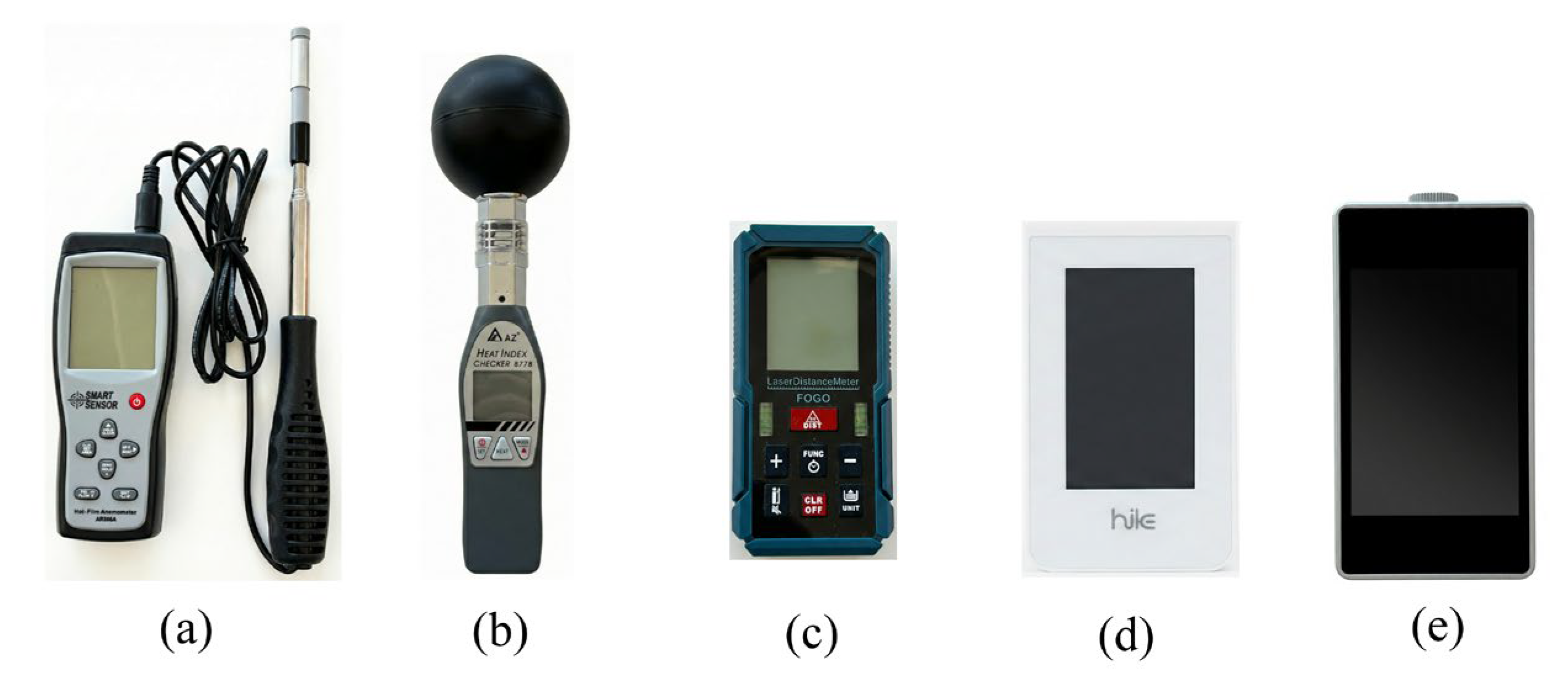

3.2.2. Measurement Devices

3.3. Questionnaire Survey

3.4. Thermal Comfort Model

3.5. Software Simulations

4. Results Analysis

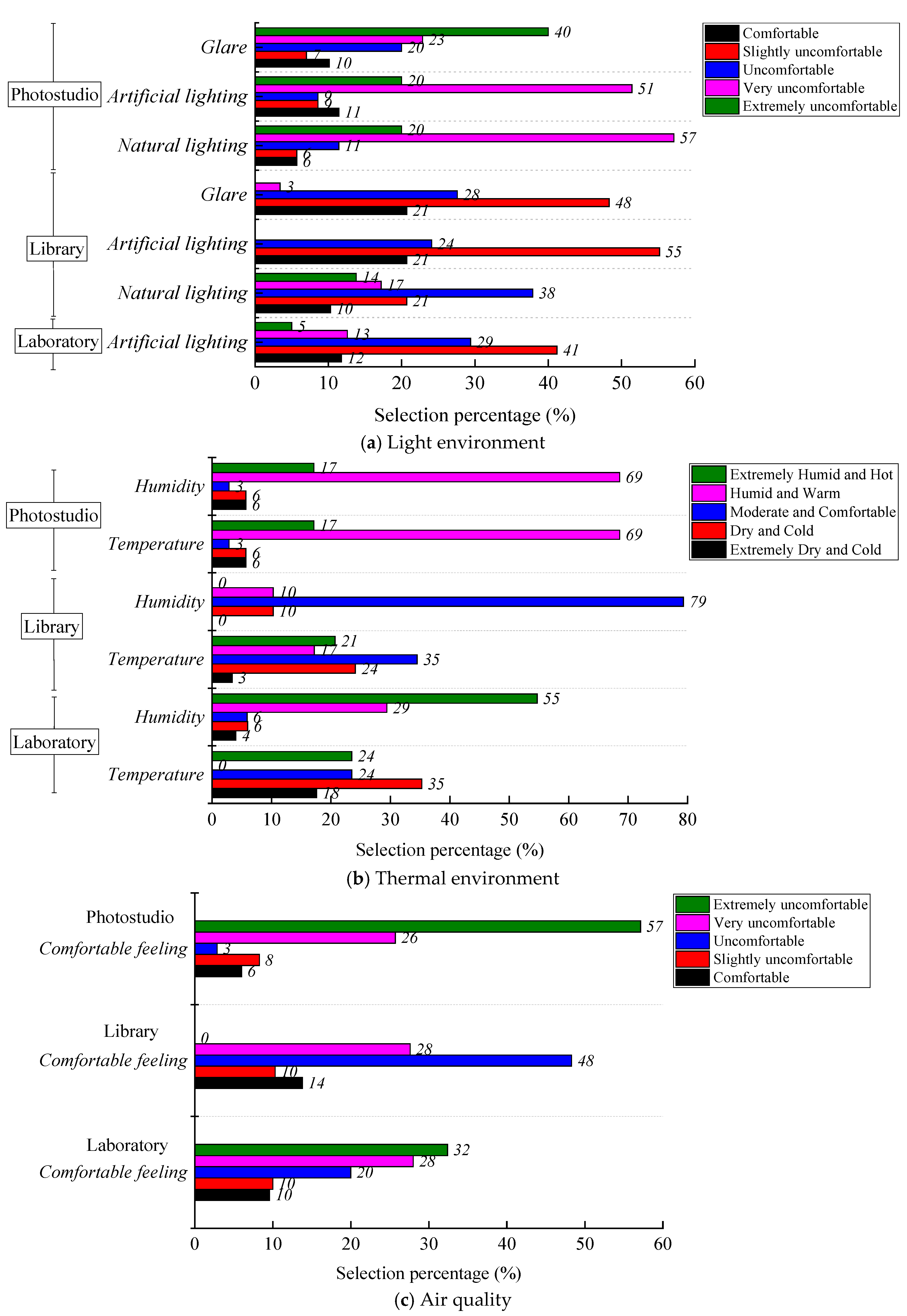

4.1. Questionnaire Results

4.2. Simulation Results

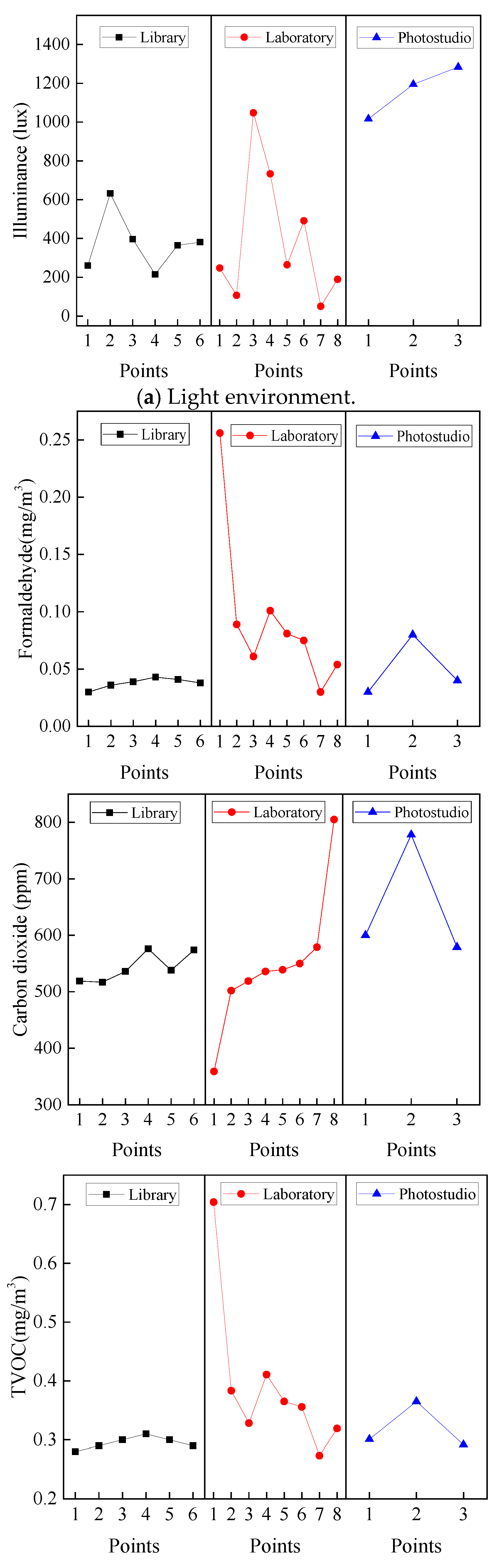

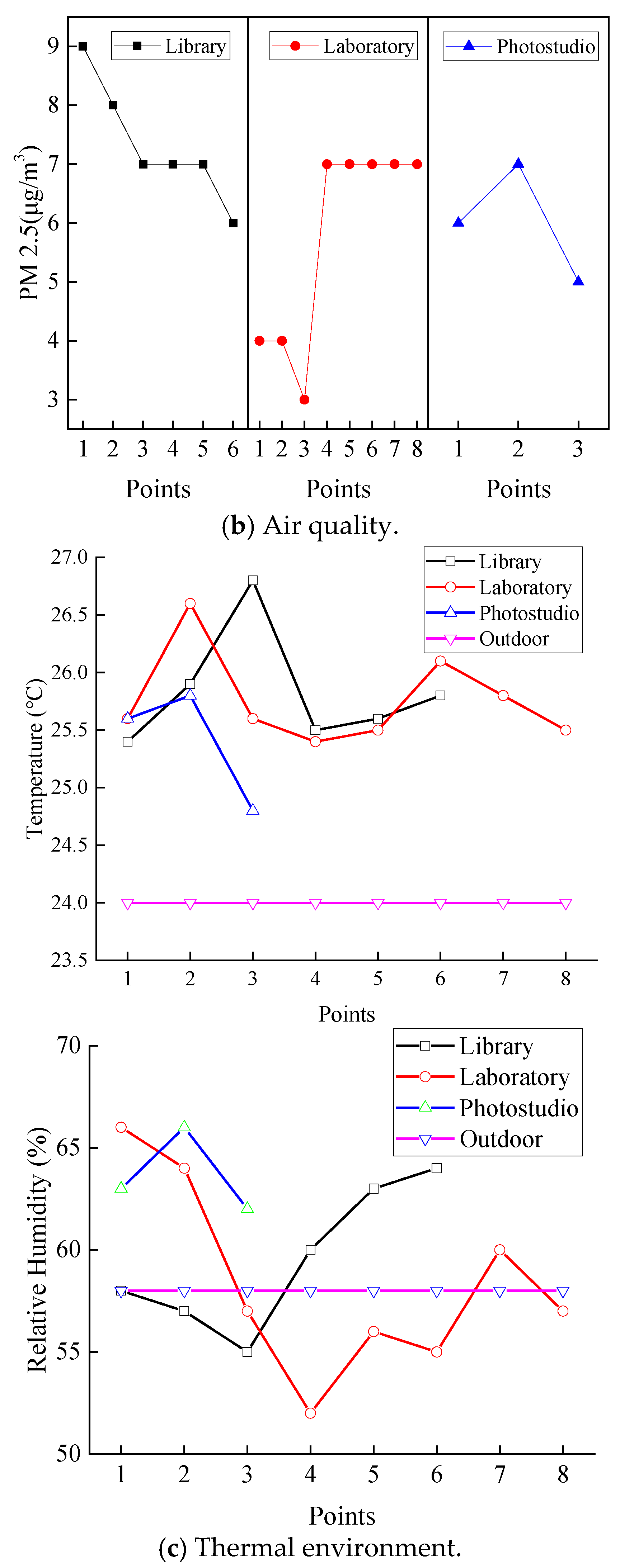

4.3. Measurement Results

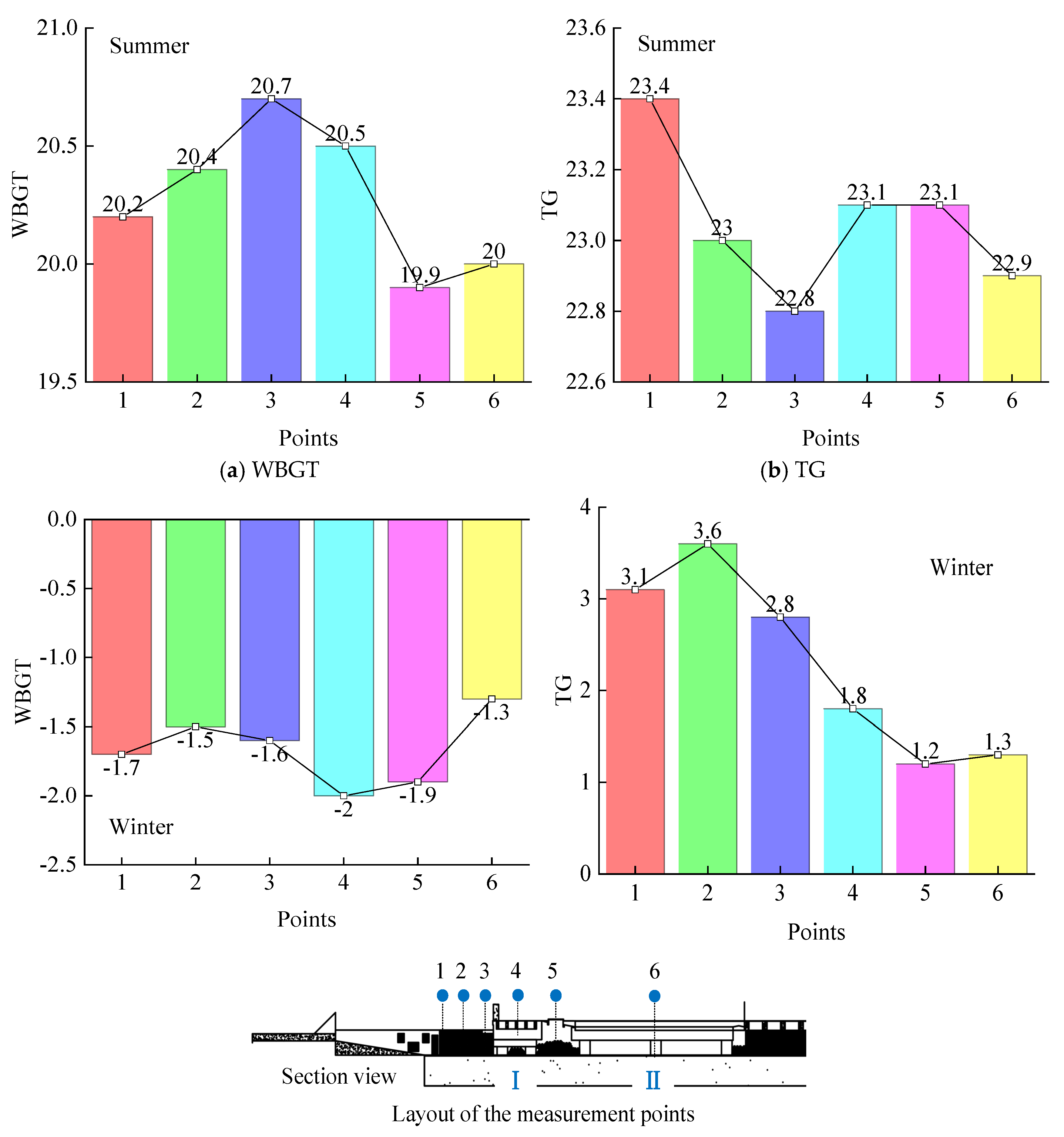

4.4. Thermal Comfort Evaluation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| PMV | predicted mean vote |

| PPD | predicted percentage of dissatisfied |

| TVOC | total volatile organic compounds |

| CO2 | carbon dioxide |

| PM2.5 | particulate matter with diameter ≤ 2.5 µm |

| WBGT | wet-bulb globe temperature |

| UTCI | universal thermal climate index |

| CSWD | Chinese standard weather data |

| WHO | world health organization |

| EPA | U.S. environmental protection agency |

| ASHRAE | American society of heating, refrigerating and air-conditioning engineers |

Appendix A

References

- Chen, P.; Nie, L.; Kang, J.; Liu, H. Research on the Influence of Open Underground Space Entrance Forms on the Microclimate: A Case Study in Xuzhou, China. Buildings 2024, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Ji, X.; Liu, H.; Fang, H.; Liu, X.; Yang, M. Optimization of Thermal and Light in Underground Atrium Commercial Spaces: A Case Study in Xuzhou, China. Int. J. Low-Carbon Technol. 2023, 18, 1227–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhu, H.; Shen, Y.; Feng, S. Green Tunnel Lighting Environment: A Systematic Review on Energy Saving, Visual Comfort and Low Carbon. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 144, 105535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 23386:2020; Building Information Modelling and Other Digital Processes Used in Construction—Methodology to Describe, Author and Maintain Properties in Interconnected Data Dictionaries. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020.

- Yuan, J.; Yu, Q.; Yao, S.; Ma, X.; Sun, Z. Multi-Objective Optimization for the Daylighting and Thermal Comfort Performance of Elevated Subway Station Buildings in Cold Climate Zone of China. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 78, 107771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, M.; Yuan, X.; Gao, L.; Xia, W.; Nan, K.; Zhang, M. Outdoor Thermal Comfort of Urban Plaza Space under Thermoacoustic Interactions –Taking Datang Everbright City as an Example. Build. Environ. 2025, 267, 112327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, C.; Ni, L.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y. Investigation on Thermal Environment of Subway Stations in Severe Cold Region of China: A Case Study in Harbin. Build. Environ. 2022, 212, 108761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Sun, Y.; Yao, Y.; Ni, L. Field Measurement and Analysis of Subway Tunnel Thermal Environment in Severe Cold Region. Build. Environ. 2023, 243, 110629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, C.; Ni, L.; Wang, Y.; Yao, Y. Field Experiment on Influence of Cold Protection Technologies on Thermal Environment of Subway Station in Severe Cold Region. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 109055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Gao, J.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, L.; Yuan, Y. Field Investigation of Indoor Air Quality and Its Association with Heating Lifestyles among Older People in Severe Cold Rural China. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 95, 110086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conceição, E.; Gomes, J.; Conceição, M.I.; Conceição, M.; Lúcio, M.M.; Awbi, H. Modelling of Indoor Air Quality and Thermal Comfort in Passive Buildings Subjected to External Warm Climate Conditions. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElBatran, R.M.; Ismaeel, W.S.E. Applying a Parametric Design Approach for Optimizing Daylighting and Visual Comfort in Office Buildings. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 3275–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakr Ali, L.; Ali Mustafa, F. Evaluating the Impact of Mosque Morphology on Worshipers’ Visual Comfort: Simulation Analysis for Daylighting Performance. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zou, Y.; Xia, H.; Jin, C. Multi-Objective Optimization Design of Residential Area Based on Microenvironment Simulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBroom, B.D.; Rahn, D.A.; Brunsell, N.A. Urban Fraction Influence on Local Nocturnal Cooling Rates from Low-Cost Sensors in Dallas-Fort Worth. Urban Clim. 2024, 53, 101823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieș, D.C.; Marcu, F.; Caciora, T.; Indrie, L.; Ilieș, A.; Albu, A.; Costea, M.; Burtă, L.; Baias, Ș.; Ilieș, M.; et al. Investigations of Museum Indoor Microclimate and Air Quality. Case Study from Romania. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Dai, M. Energy-Saving and Ecological Renovation of Existing Urban Buildings in Severe Cold Areas: A Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwetaishi, M. Energy Performance in Residential Buildings: Evaluation of the Potential of Building Design and Environmental Parameter. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castilla, N.; Llinares, C.; Bravo, J.M.; Blanca, V. Subjective Assessment of University Classroom Environment. Build. Environ. 2017, 122, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, H.W.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; Mobach, M.P.; Kort, H.S.M. A Systematic Approach to Quantify the Influence of Indoor Environmental Parameters on Students’ Perceptions, Responses, and Short-term Academic Performance. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e13116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Fan, Y.; Dong, Z.; Hu, X.; Yue, J. Improving Visual Comfort and Health through the Design of a Local Shading Device. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE Standard 55-2023; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023.

- GB 50157-2013; Code for Design of Metro (GB 50157-2013). Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2013.

- GB 50189-2015; Design Standard for Energy Efficiency of Public Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2015.

- GB 50033-2013; Standard for Daylighting Design of Buildings. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- GB/T 18883-2022; Standards for Indoor Air Quality. State Administration for Market Regulation & Standardization Administration of the P.R.C.: Beijing, China; Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2022.

- ISO 7730:2005; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240034228 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Building Air Quality: A Guide for Building Owners and Facility Managers; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, C.; Du, Z.; Lin, G.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Wu, K. Luminance Stepped Decreasing Ratio of the Tunnel Entrance Enhanced Lighting Based on Visual Performance. Appl. Opt. 2022, 61, 6553–6560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sui, X.; Chen, S.; Han, B.; Yu, S. Evaluation of the Thermal Environment of Xi’an Subway Stations in Summer and Determination of the Indoor Air Design Temperature for Air-Conditioning. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, H.; Wu, Y. Analysis of Dynamic Characteristics of CO2 Concentration in Subway Cars. E3S Web Conf. 2022, 356, 02019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, H.; Jin, Y.; Li, Z. Experimental and Numerical Investigation of TVOC Concentrations and Ventilation Dilution in Enclosed Train Cabin. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 831–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yao, H.; Wang, F. A Review of Ventilation and Environmental Control of Underground Spaces. Energies 2022, 15, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nang, E.E.K.; Abuduxike, G.; Posadzki, P.; Divakar, U.; Visvalingam, N.; Nazeha, N.; Dunleavy, G.; Christopoulos, G.I.; Soh, C.-K.; Jarbrink, K.; et al. Review of the Potential Health Effects of Light and Environmental Exposures in Underground Workplaces. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2019, 84, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instrument | Measurement Content | Measurement Range | Accuracy | Pictures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIMAA Thermosensitive anemometer—air flow meter AR866A | Air velocity | 0.3–30 m/s | ±0.5 m/s | Figure 3a |

| Wind temperature | 0–45 °C | / | ||

| Air volume | 0–999,900 m3/min | / | ||

| AZ instrument temperature—heat index meter AZ8778 | Air temperature | 0–50 °C | ±0.6 °C | Figure 3b |

| Humidity | 0–100% RH | ±3% RH | ||

| Globe temperature (Black globe diameter: 75 mm) | 0–80 °C | ±1 °C | ||

| WBGT index | 0–50 °C | ±0.6 °C | ||

| FOGO handheld laser rangefinder | Distance | 0.2–120 m | ±2 mm | Figure 3c |

| Hiciv air detector B6A | CO2 | 0–9999 ppm | ±40 ppm | Figure 3d |

| PM2.5 | 0–999 μg/m3 | ±15% | ||

| PM10 | 0–999 μg/m3 | ±15% | ||

| Formaldehyde | 0–9.999 mg/m3 | ±0.03 mg/m3 | ||

| TVOC | 0.22–9.99 mg/m3 | ±0.03 mg/m3 | ||

| Dual-color cloud spectrum intelligent spectral illuminometer HP320 | Illuminance | 0.1~200K lx | ±4% | Figure 3e |

| Thermal Sensation | Hot | Warm | Slightly Warm | Neutral | Slightly Cool | Cool | Cold |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMV | +3 | +2 | +1 | 0 | −1 | −2 | −3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ye, Z.; Liang, T.; Yi, H.; Zhang, S. Influence of Microclimate on Human Thermal and Visual Comfort in Urban Semi-Underground Spaces. Atmosphere 2026, 17, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010029

Ye Z, Liang T, Yi H, Zhang S. Influence of Microclimate on Human Thermal and Visual Comfort in Urban Semi-Underground Spaces. Atmosphere. 2026; 17(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Zijian, Tianlong Liang, Hui Yi, and Shize Zhang. 2026. "Influence of Microclimate on Human Thermal and Visual Comfort in Urban Semi-Underground Spaces" Atmosphere 17, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010029

APA StyleYe, Z., Liang, T., Yi, H., & Zhang, S. (2026). Influence of Microclimate on Human Thermal and Visual Comfort in Urban Semi-Underground Spaces. Atmosphere, 17(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos17010029