Abstract

Accurate nitrogen dioxide (NO2) forecasting is crucial for proactive emission control and issuing public health warnings. This study provides the first evaluation of the China Meteorological Administration’s (CMA) operational CUACE/Haze-Fog V3.0 numerical prediction system, assessing its daily NO2 forecast accuracy against independent satellite measurements and in situ observations. We compare model forecasts with TROPOspheric Monitoring Instrument (TROPOMI) satellite column data and observations from 1677 Chinese ground monitoring stations, focusing on four key regions: the Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta, Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, and Urumqi. An optimal spatial resolution of 0.15° × 0.15° was determined for TROPOMI data processing. The results indicate a strong seasonal dependency in model performance. The model systematically underestimates NO2 concentrations in winter but performs significantly better in summer. This systematic bias is confirmed by a Normalized Mean Bias (NMB) consistently below −20% in northern regions during the winter. In the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) reached 3.57 × 1015 molec/cm2 (vs. TROPOMI) and 1.09 × 1015 molec/cm3 (vs. ground stations) in winter, decreasing to 0.95 and 0.91, respectively, in summer. Critically, this winter bias pertains to pollution magnitude rather than temporal correlation; the model captures pollution trends but underestimates peak severity. Our study reveals a ‘vertical decoupling’ in the operational forecasting system. While the model utilizes surface data assimilation to correct surface pollutants, this study demonstrates that these corrections fail to propagate vertically to the total NO2 column during winter stable boundary layer conditions. This finding has broader implications for chemical transport models (CTMs): relying solely on surface data assimilation is insufficient for constraining column burdens in regions with complex vertical stratification. We propose that future operational systems integrate satellite-based vertical constraints to resolve the systematic winter bias identified here.

1. Introduction

Nitrogen oxides (NOx), comprising nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and nitric oxide (NO), are critical trace gases in the Earth’s atmosphere. Emitted primarily from anthropogenic activities such as vehicle exhaust and industrial processes [1], they serve as key precursors in the photochemical formation of ground-level ozone (O3), nitric acid, and Peroxyacyl nitrates (PANs) [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Beyond their environmental impact, NOx pose significant risks to public health. Prolonged exposure has been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases [1,8], with recent evidence suggesting potential associations with cognitive decline [9,10]. Since the early detection of these pollutants via remote sensing [11], monitoring tropospheric NO2—which is concentrated largely in the planetary boundary layer [12]—has become essential for both air quality management and health risk assessment.

While monitoring is vital, numerical forecasting remains central to China’s environmental protection strategy for proactive emission control. The CMA-CUACE/Haze-Fog V3.0, operational since November 2022, represents a significant upgrade featuring a refined 9 km resolution and improved physicochemical mechanisms, specifically including new heterogeneous reactions for secondary aerosols [13]. A critical innovation in this system (developed by Li et al., 2023 [14]) is the integration of dynamic data correction techniques, via an Ensemble Optimal Interpolation (EnOI) module driven by ground-based PM2.5 observations to explicitly constrain initial aerosol fields. However, this system currently neither assimilates gas-phase NO2 observations nor assumes a correlation between PM2.5 and NOx emissions during assimilation. Consequently, NO2 concentrations remain primarily driven by the emission inventory and meteorological conditions, leading to the potential for vertical and chemical decoupling, as demonstrated in this study.

While satellite retrievals like the TROPOMI have been widely used to evaluate chemical transport models [15,16,17,18], the CUACE V3.0 system presents a unique challenge. Since the system is primarily corrected by surface-level particulate data, a significant gap remains regarding how these surface-driven corrections propagate vertically to influence the total NO2 column. Specifically, it is crucial to determine whether surface assimilation effectively constrains the column burden or if a ‘vertical decoupling’ occurs under stable boundary layer conditions. Therefore, this study utilizes TROPOMI data as an independent, vertically aware benchmark to diagnose the cross-species efficacy of the model’s correction schemes [19].

The Sentinel-5P satellite, equipped with the TROPOMI, offers daily global coverage at high spatial resolution [19,20,21]. Unlike ground observations, which are limited to specific point locations, TROPOMI provides a spatially continuous dataset essential for resolving fine-scale atmospheric features and validating the regional consistency of the forecasting system [20].

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the datasets utilized in this study (including CUACE/Haze-Fog model data, TROPOMI satellite data, and ground-station observations) and the research methodology. Section 3 compares and analyzes the accuracy of the CUACE/Haze-Fog model with high-resolution TROPOMI satellite data and in situ observations across macroscopic, temporal, and quantitative dimensions, investigating the potential sources of model error. Finally, Section 4 provides a summary and discussion.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. CUACE/Haze-Fog Model Forecast Data

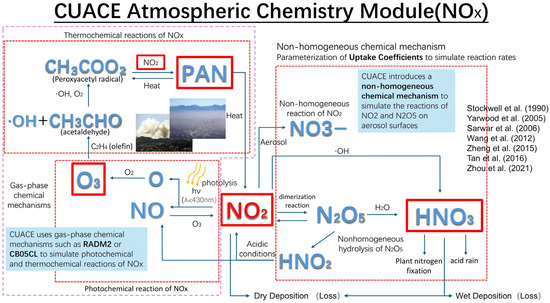

The CMA-CUACE/Haze-Fog V3.0 is an operational atmospheric chemistry forecasting system online-coupled with the GRAPES-Meso 5.1 meteorological driver. The simulation domain covers China with a 9 km horizontal resolution, enabling precise modeling of aerosols and key pollutants including PM2.5, PM10, O3 and visibility [22]. To address the lag in official inventories for the 2024 operational run, anthropogenic emissions are derived from the MEIC 2021 baseline (Multi-resolution Emission Inventory for China, http://meicmodel.org.cn/?page_id=560 (accessed on 24 November 2025)) [23,24]. Crucially, to represent 2024 conditions, these emissions are adjusted monthly using the “rapid update technology” described by Li et al. (2023) [14]. This process is driven exclusively by ground-based observations and does not utilize satellite data. Consequently, the TROPOMI measurements used in this study serve as a strictly independent dataset for model evaluation. The model’s chemical framework integrates gas-phase, aerosol, and thermodynamic modules [22,25]. Gas-phase chemistry is primarily governed by the RADM2 mechanism [26], while the CB05CL scheme was recently incorporated in 2023 to offer users the option to choose between these two mechanisms [27], the operational forecasts evaluated in this study utilized the RADM2 mechanism. The thermodynamic equilibrium module employs an optimized ISORROPIA algorithm to significantly enhance computational efficiency [28,29]. As detailed in Figure 1, the NOx chemistry simulates the core photolysis cycle, reservoir formation (e.g., PAN), and heterogeneous reactions on aerosol surfaces, with dry and wet deposition serving as primary loss pathways.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the NOx atmospheric chemistry module in the CUACE/Haze-Fog model. The simulation integrates the gas-phase mechanisms (RADM2 and CB05CL) established by Stockwell et al. [26] and Yarwood et al. [30] Furthermore, it incorporates heterogeneous chemistry and parameterizations on aerosol surfaces, including updates to the CMAQ system by Sarwar et al. [31] dust chemistry by Wang et al. [32] heterogeneous reactions during haze by Zheng et al. [33] aerosol liquid water impacts by Tan et al. [34] and optimized uptake coefficients by Zhou et al. [35].

2.1.2. NO2 Ground Monitoring Station Data

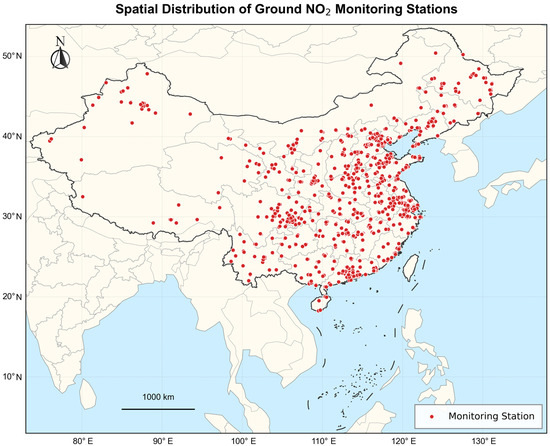

This study utilizes hourly NO2 observations from 1677 national air quality monitoring stations for the year 2024, sourced from the National Urban Air Quality Real-time Release Platform (https://air.cnemc.cn:18007/ (accessed on 24 November 2025)). The spatial distribution of these stations is illustrated in Figure 2. To ensure data reliability, a strict quality control pipeline was applied to the raw dataset. We adopted a stringent quality control protocol to filter instrument errors. Physical thresholds were defined as 0.00 < NO2 < 2000.0 µg/m3. To avoid statistical artifacts (high-bias) arising from selectively removing only negative tails (noise), any station reporting values outside this physical range was deemed unreliable due to instrument instability and was excluded from the dataset. Additionally, stations possessing low temporal coverage (<75% valid hourly data) were excluded. This rigorous screening process resulted in a final selection of 1677 valid monitoring stations. The remaining valid observations were then compiled and interpolated for model comparison.

Figure 2.

The spatial distribution of the 1677 air quality monitoring stations in China used in this study.

2.1.3. Sentinel-5P TROPOMI Satellite NO2 Column Concentration Data

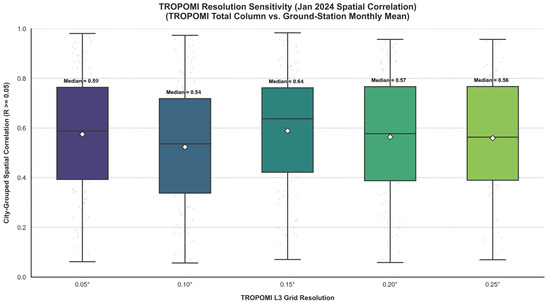

We utilized the Sentinel-5P TROPOMI OFFLINE Level 2 NO2 products (KNMI processor version 1.4.0), which have been validated against global ground-based measurements [36]. In strict accordance with the product user manual, a quality filter (qa_value > 0.75) was applied to exclude pixels affected by cloud cover or retrieval errors [37]. To determine the optimal grid for model evaluation, we followed the methodology outlined by Pope et al. [38] and conducted a spatial resolution sensitivity analysis (Figure 3) ranging from 0.05° to 0.25°. Results indicated that the 0.15° × 0.15° resolution yielded the highest spatial correlation (R = 0.64) with ground observations, effectively balancing the trade-off between signal dilution at coarser resolutions and high noise levels at finer resolutions. Consequently, all satellite data were re-gridded to 0.15° × 0.15° using the HARP toolkit for this study.

Figure 3.

TROPOMI resolution sensitivity analysis to determine the optimal grid size for comparison with ground-station data. The box plots show the city-grouped spatial correlation (R) between TROPOMI NO2 total columns and ground-station monthly means (using January 2024 data) at five different TROPOMI L3 grid resolutions (0.05° to 0.25°). The central line represents the median, the white diamond indicates the mean, the box limits indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles (Interquartile Range), and the whiskers extend to 1.5 times the IQR.

2.1.4. Observation Uncertainties

We explicitly address measurement artifacts affecting seasonal validation. First, ground-based chemiluminescence analyzers employing molybdenum converters are subject to positive interferences from oxidized nitrogen species (e.g., PAN, HNO3) [39]. This results in an overestimation of surface NO2, particularly during active summer photochemistry. Second, despite strict quality filtering (qa_value > 0.75), TROPOMI retrievals in Northern China are susceptible to negative biases in winter due to high aerosol loading and snow cover. These opposing artifacts—summer ground overestimation and winter satellite underestimation—are explicitly considered when interpreting model performance in Section 3.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Model Data Processing and Unit Conversion

To evaluate the operational forecasting performance, surface-level NO2 concentrations were extracted from the model’s lowest vertical layer and bilinearly interpolated to the geographic coordinates of the 1677 monitoring stations. To ensure physical consistency with the number density units used in scientific analysis, mass concentrations (µg/m3) were converted to number densities (molecules/cm3) using standard molar mass calculations based on the ideal gas law. No vertical integration was performed for the ground comparison as both datasets represent surface levels. For the comparison with TROPOMI satellite data, we directly utilized the model’s surface-level data rather than integrating it into a column. Consequently, no averaging kernel or tropopause determination was applied to the model data. This approach draws on the established relationship between surface concentrations and column densities S = ν × Ω [40]. By using the regression slope between TROPOMI columns and ground observations as an empirical baseline for the vertical profile shape factor (ν), we can diagnose whether the model correctly reproduces the column-to-surface ratio, which is critical for identifying vertical decoupling issues.

2.2.2. Statistical Metrics

The model performance was quantitatively evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) [41], Normalized Mean Bias (NMB) [42], and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [43]. These metrics provide a comprehensive assessment: r evaluates the temporal synchronization of pollution trends; NMB reveals the direction of systematic bias (over- or underestimation); and RMSE quantifies the overall magnitude of errors. The calculations are defined as follows:

where (or ) and (or ) represent the observed and forecasted values at time , respectively; and denote their means; and N is the total number of samples.

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Distribution of Observed and Forecast NO2 Concentrations in China

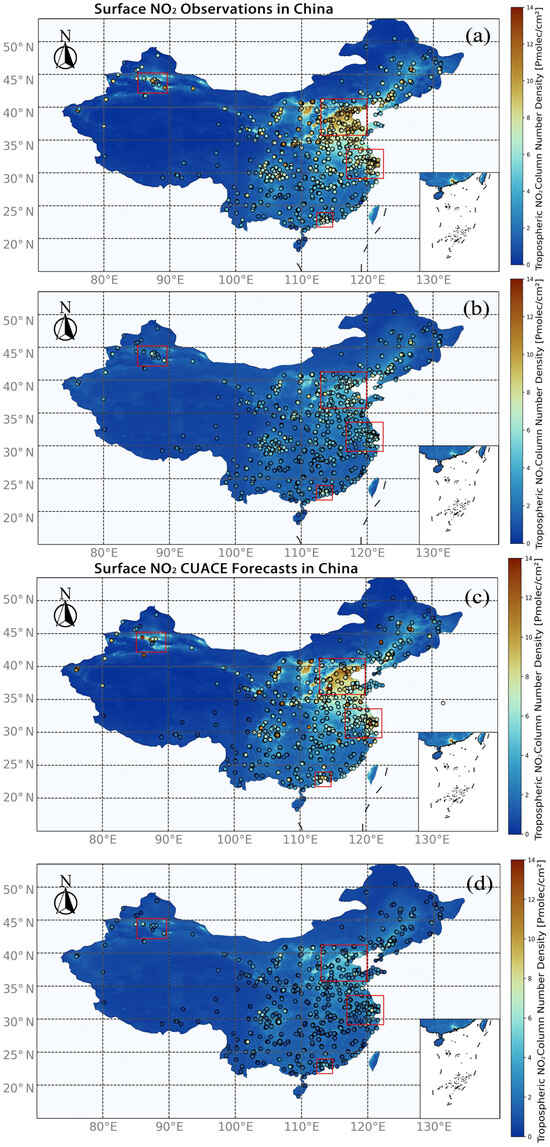

Figure 4 presents the spatial distribution maps of NO2 concentrations comparing ground-station observations (panels Figure 4a,b) and CUACE/Haze-Fog forecast data (panels Figure 4c,d), all overlaid on the TROPOMI satellite data which serve as the background map.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of tropospheric NO2 column density over China in winter (a,c) and summer (b,d) 2024. Panels (a,b) compare TROPOMI data (background) with ground-station observations (circles). Panels (c,d) compare TROPOMI data with CUACE/Haze-Fog forecasts (circles). The red boxes indicate the Kashi region (left), and the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Yangtze River Delta, and Pearl River Delta regions (right, from top to bottom).

The analysis of the winter distribution (Figure 4a,c) shows a significant increase in NO2 concentration during these months, particularly in urban areas such as the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region [44], the Pearl River Delta [45], the Yangtze River Delta [46] and Urumqi in Xinjiang [47]. This is consistent with previous studies. These regions, characterized by dense populations and intensive industrial and agricultural activities, exhibit significant contributions from anthropogenic NOx emissions. The demand for centralized heating in northern cities, coupled with lower temperatures, lower air humidity, and reduced wind speeds, leads to a decrease in the height of the atmospheric stable layer. Recent studies utilizing multi-source observations have quantitatively confirmed that these meteorological constraints—specifically the suppression of the planetary boundary layer (PBL) height and weak near-surface ventilation—are the dominant drivers for the accumulation of surface pollutants in Northern Hemisphere winters [48,49,50,51]. For instance, research in similar high-latitude regions has shown that extreme concentrations are closely linked to anticyclonic weather and stable atmospheric stratification, which traps anthropogenic emissions near the ground [49,50]. Furthermore, evaluating vertical limitations in atmospheric models remains a challenge; recent assessments over the Mongolian Plateau indicate that even reanalysis datasets (e.g., ERA5) can exhibit significant biases in simulating boundary layer heights and wind profiles during winter stable conditions [52]. Crucially, these wintertime biases in ERA5 PBL height are reported to be especially large during periods with high aerosol loading, which further exacerbates the difficulty in correctly simulating the vertical distribution of pollutants during severe haze events [53]. Additionally, weakened solar radiation diminishes photolysis, thereby reducing the rate at which NO2 is converted into other compounds [54]. Consequently, NO2 levels show a marked increase compared to summer.

By comparing Figure 4a (Ground Station) and Figure 4c (CUACE Model) in winter, it is evident that the CUACE/Haze-Fog model demonstrates relatively good forecasting accuracy in these major urban areas with high NO2 pollution. However, some discrepancies remain. For instance, the CUACE/Haze-Fog forecasted NO2 concentrations in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei (Figure 4c) are slightly lower than those recorded by ground stations (Figure 4a).

The distribution maps of NO2 concentrations in the summer of 2024 (Figure 4b,d) indicate that NO2 levels across the country are significantly lower compared to winter. This seasonal reduction can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, intense solar radiation promotes the photolysis of NO2, generating NO and excited oxygen atoms (O), which subsequently lead to the formation of O3 and OH radicals. The OH radicals, acting as important oxidants, play a critical role in the oxidative removal of NO2 [55]. Secondly, the absence of centralized heating systems, which are prevalent in winter, contributes to the lower NO2 concentrations observed during the summer months. However, despite these reductions, NO2 concentrations in the urban areas remain slightly higher than those in rural regions [56].

The summer forecast data of the CUACE/Haze-Fog model demonstrate that the predicted values of NO2 concentration are lower than those in winter, and the predicted concentration in urban areas is higher than that in rural areas, which is in line with the actual situation (Figure 4b) and indicates that the model can capture the distribution pattern of NO2 in China better. In contrast, the winter forecast data (Figure 4c) exhibited anomalous areas with elevated NO2 concentrations, such as the vicinity of Changchun in the northeast and near Kashgar in the northwest [57]. Unlike the broad regional patterns, these localized hotspots likely stem from uncertainties in the spatial allocation of point-source emissions within the inventory. In these areas, the model’s predictions showed discrepancies with both the ground-station observations (Figure 4a) and the satellite data (background), suggesting potential inaccuracies in the model’s representation. The summer forecast data demonstrated superior performance, exhibiting no such anomalously high values.

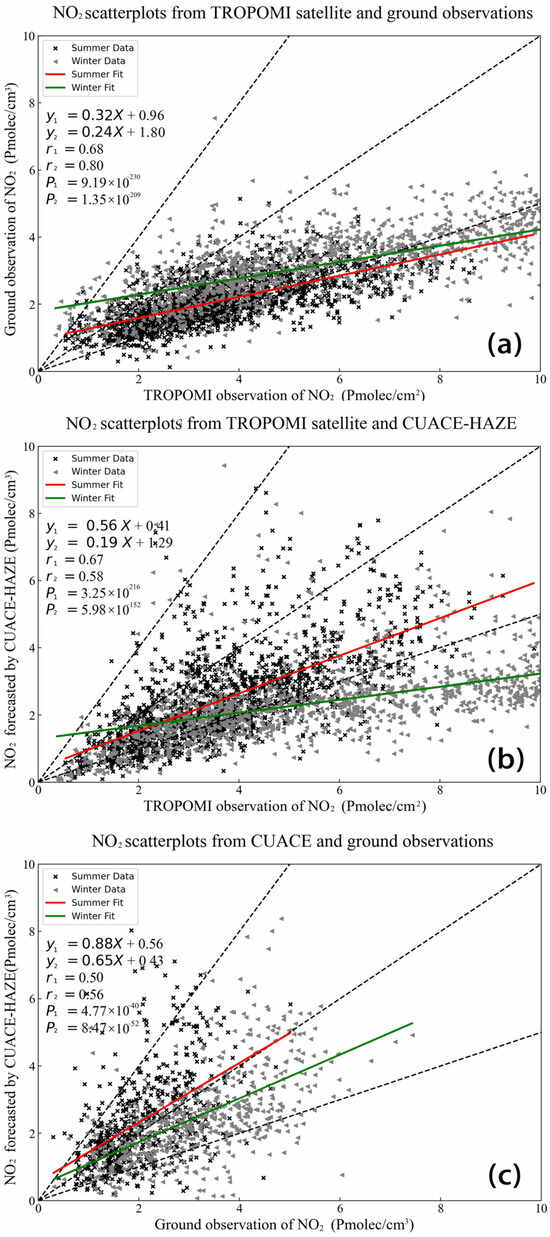

3.2. Correlation Between Satellite/Ground Observations and Forecasts by Season

Figure 5a establishes the baseline observational relationship between TROPOMI columns and ground concentrations. A significant positive correlation is evident, particularly in winter (r = 0.77) compared to summer (r = 0.68), consistent with Pope et al. [38]. Despite known positive biases in ground measurements due to molybdenum converter interference [58], the stronger winter correlation indicates that stable meteorological conditions (e.g., lower PBL height) dominate the column-to-surface relationship, superseding photochemical artifacts [59]. Crucially, this panel defines the empirical “column-to-surface” conversion ratio: the regression slopes (Summer: 0.32, Winter: 0.24) reflect how TROPOMI’s total column observations map onto actual surface concentrations under different seasonal meteorological conditions.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot comparisons of model performance and observations. (a) TROPOMI NO2 column density (x-axis) vs. ground-station observations (y-axis). (b) TROPOMI NO2 column density (x-axis) vs. CUACE/Haze-Fog forecasts (y-axis). (c) Ground-station observations (x-axis) vs. CUACE/Haze-Fog forecasts (y-axis). Linear regression parameters (y, r, p) are annotated.

The evaluation of the CUACE model reveals distinct performance characteristics when assessed against these baselines. In the Model vs. TROPOMI comparison (Figure 5b), the model’s performance is evaluated against the observational baseline in Figure 5a rather than the 1:1 identity line. The model’s winter slope (0.19) is comparable to the observed winter slope (0.24) in Figure 5a. This alignment suggests that the model reasonably reproduces the physical relationship between the total column and the surface layer, successfully capturing the vertical distribution characteristics of the winter atmosphere.

In contrast, the model vs. ground comparison (Figure 5c) represents a direct evaluation of surface-level magnitude and is strictly assessed against the 1:1 diagonal. Here, the systematic deficiency becomes apparent: the winter slope is only 0.65, significantly deviating from the 1:1 line. Synthesizing these findings, the model correctly simulates the ratio between column and surface (consistent with Figure 5a vs. Figure 5b) but systematically underestimates the absolute magnitude of surface concentrations (Figure 5c), pointing to insufficient emission intensity rather than errors in vertical transport structure.

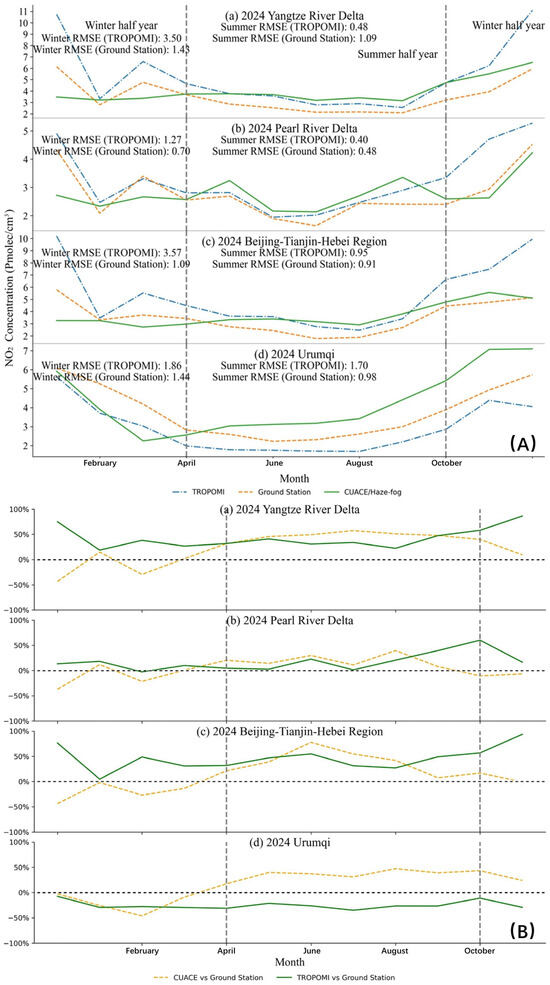

3.3. Error (RMSE) and Bias Analysis of NO2 Time Series in Key Regions

Figure 6 (top panel, Figure 6a–d) shows the monthly mean NO2 time series in four key Chinese regions. These charts confirm a strong seasonality: concentrations peak in winter (October–March) and fall to a trough in summer (April–September). As shown by the RMSE values annotated on the charts, the CUACE/Haze-Fog forecast model’s prediction error in winter is higher than in summer. For example, in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region (Figure 6c, top panel), the winter RMSE against the TROPOMI reaches 3.57 × 1015 molec/cm2, while against ground-station data it is 1.09 × 1015 molec/cm3. In summer, these values decrease to 0.95 × 1015 molec/cm2 and 0.91 × 1015 molec/cm3, respectively, consistent with the analysis in Section 3.2.

Figure 6.

Monthly time series and bias analysis for key regions in 2024. Top panel (A) monthly mean NO2 concentration time series, comparing the TROPOMI (blue dash-dot), ground station (orange dashed), and CUACE/Haze-Fog (green solid). Annotated text provides seasonal RMSE values. Bottom panel (B) Monthly Normalized Mean Bias (NMB) relative to ground-station data, comparing CUACE/Haze-Fog (orange dash) and the TROPOMI (green solid).

Figure 6 (bottom panel, Figure 6a–d) further quantifies this bias by plotting the monthly percentage differences. In winter, the CUACE model exhibits a persistent negative bias (NMB < −20%) in northern regions (Yangtze River Delta, Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei, and Urumqi). This systematic winter underestimation is likely driven by two coupled factors. First, regarding boundary layer dynamics, the model may overestimate the height of the planetary boundary layer (PBL) or vertical mixing coefficients under stable winter conditions, leading to excessive dilution of surface pollutants [51]. Second, limitations in the emission inventory likely contribute to the bias, as the “rapid update technology” applied to the 2021 baseline may not fully capture the intensity of residential heating emissions during the 2024 winter. Consequently, while the current analysis suggests that excessive vertical dilution is a primary contributor, other factors cannot be fully ruled out without high-resolution vertical validation. A noteworthy exception is the Pearl River Delta (Figure 6b, bottom panel), where the bias remains closer to zero throughout the year, indicating better model performance in regions with less intense winter heating requirements. This contrast indicates that the model demonstrates superior performance in southern regions where winter heating emissions are negligible and atmospheric ventilation is stronger.

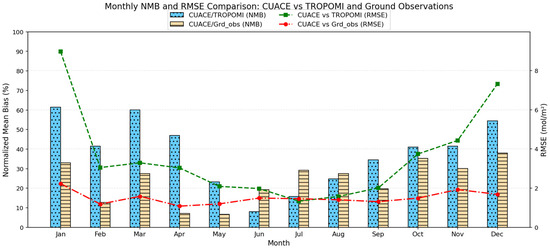

3.4. Monthly Variation in NMB and RMSE

Figure 7 quantifies the monthly NMB and RMSE, revealing performance differences in the CUACE/Haze-Fog model when compared against two observation types. When compared against TROPOMI column concentrations (blue bars), the CUACE/Haze-Fog model’s bias (NMB) exhibits strong seasonality: the bias is extremely high in winter (exceeding 60% in both January and March) but decreases sharply in summer (dropping to a minimum of about 8% in June). This pattern suggests the CUACE/Haze-Fog model’s simulation of NO2 column concentrations is more accurate under high-temperature, strong photochemical conditions.

Figure 7.

Monthly statistical evaluation of the CUACE model against TROPOMI (blue bars/green line) and ground observations (tan bars/red line) in 2024, showing NMB and RMSE trends.

However, when compared against ground observations (brown bars), the CUACE/Haze-Fog model demonstrates entirely different characteristics. Its NMB values are much smaller (ranging from 7% to 38% year-round), with far less volatility compared to the column concentration bias.

The RMSE analysis (line graphs) also reflects this performance divergence between “surface” and “total column” data. The CUACE/Haze-Fog model’s RMSE against the TROPOMI (green line) aligns with the NMB’s seasonality, reaching an error peak of 9.00 mol/m2 in January. In contrast, the CUACE/Haze-Fog model’s RMSE against ground observations (red line) remains at a very low level throughout the year. This value reaches its minimum in April (approx. 1.1) and its maximum in January (approx. 2.2), showing significantly less fluctuation than the TROPOMI RMSE.

4. Conclusions and Discussion

This study provided the first comprehensive evaluation of the CMA-CUACE/Haze-Fog V3.0 forecasting system against TROPOMI satellite columns and ground observations. The analysis reveals that the model’s performance exhibits a strong seasonal dependency, characterized by a systematic underestimation in winter. Crucially, our results indicate that this winter bias is driven by magnitude rather than correlation. While the model captures the temporal evolution of pollution events (R = 0.56 in winter), it fails to reproduce peak severity, with regression slopes falling significantly below the 1:1 diagonal.

A critical contribution of this study is the distinction between forecasting system deficiencies and inherent evaluation uncertainties. The apparent “overestimation” in summer is partially attributable to observational biases, as ground-based molybdenum converters are known to positively bias NO2 readings by interfering with oxidized nitrogen species (NOz) under strong photochemical conditions [39,58]. Consequently, the model’s summer performance may be more accurate than the raw statistics suggest. In contrast, the severe winter underestimation represents a fundamental physical deficiency in the forecasting system. The discrepancy between surface corrections and total column burdens suggests a “vertical decoupling”: under stable winter boundary layer conditions, surface-based data assimilation fails to effectively constrain the total column burden, likely due to insufficient vertical propagation of information or overestimated PBL heights.

To resolve this vertical decoupling, reliance solely on surface PM2.5 assimilation (EnOI) is insufficient for complex vertical stratification. Future operational upgrades require robust vertical constraints. To address the limitation of sparse observational data highlighted in this study, our ongoing work is specifically dedicated to reconstructing spatiotemporally continuous, gap-free vertical profiles derived from TROPOMI retrievals. Assimilation of this reconstructed 3D dataset is the planned next step for the CUACE system. While the specific assimilation pathway is currently under evaluation, integrating these satellite-derived vertical profiles will directly constrain the total column burden, bridging the gap between surface observations and upper-level transport to correct the systematic magnitude bias identified in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Z., Q.C. and J.F.; Data curation, H.Z. and L.A.; Formal analysis, H.Z.; Methodology, H.Z.; Project administration, X.Z.; Resources, X.Z.; Software, H.Z. and Y.W. Validation, H.Z.; Visualization, H.Z.; Writing—original draft, H.Z.; Writing—review & editing, X.Z. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2442210; 42275059; 42275009) and Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2023NSFSC0246; 2024NSFTD0017).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Linchang An of National Meteorological Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meng, X.; Liu, C.; Chen, R.; Sera, F.; Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M.; Milojevic, A.; Guo, Y.; Tong, S.; Coelho, M.d.S.Z.S.; Saldiva, P.H.N.; et al. Short Term Associations of Ambient Nitrogen Dioxide with Daily Total, Cardiovascular, and Respiratory Mortality: Multilocation Analysis in 398 Cities. BMJ 2021, 372, n534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crutzen, P. A Discussion of the Chemistry of Some Minor Constituents in the Stratosphere and Troposphere. Pure Appl. Geophys. 1973, 106, 1385–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Naeher, L.P. A Review of Traffic-Related Air Pollution Exposure Assessment Studies in the Developing World. Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamsal, L.N.; Martin, R.V.; Parrish, D.D.; Krotkov, N.A. Scaling Relationship for NO2 Pollution and Urban Population Size: A Satellite Perspective. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7855–7861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Craemer, S.; Vercauteren, J.; Fierens, F.; Lefebvre, W.; Meysman, F.J.R. Using Large-Scale NO2 Data from Citizen Science for Air-Quality Compliance and Policy Support. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 11070–11078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Jacob, D.J.; Liao, H.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Q.; Bates, K.H. Anthropogenic Drivers of 2013–2017 Trends in Summer Surface Ozone in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 422–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Z.; Jacob, D.J.; Silvern, R.F.; Shah, V.; Campbell, P.C.; Valin, L.C.; Murray, L.T. US COVID-19 Shutdown Demonstrates Importance of Background NO2 in Inferring NOx Emissions From Satellite NO2 Observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2021, 48, e2021GL092783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, R.; Islam, T.; Shankardass, K.; Jerrett, M.; Lurmann, F.; Gilliland, F.; Gauderman, J.; Avol, E.; Künzli, N.; Yao, L.; et al. Childhood Incident Asthma and Traffic-Related Air Pollution at Home and School. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1021–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrakou, T.; Müller, J.-F.; Boersma, K.F.; van der A, R.J.; Kurokawa, J.; Ohara, T.; Zhang, Q. Key Chemical NOx Sink Uncertainties and How They Influence Top-down Emissions of Nitrogen Oxides. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2013, 13, 9057–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, S.; Wang, J.; You, W.; Xu, J.; Chen, G. The Potential Role of Nitrogen Dioxide Inhalation in Parkinson’s Disease. Med Gas Res 2024, 14, 153–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hains, J.C.; Boersma, K.F.; Kroon, M.; Dirksen, R.J.; Cohen, R.C.; Perring, A.E.; Bucsela, E.; Volten, H.; Swart, D.P.J.; Richter, A.; et al. Testing and Improving OMI DOMINO Tropospheric NO2 Using Observations from the DANDELIONS and INTEX-B Validation Campaigns. J. Geophys. Res. (Atmos.) 2010, 115, D05301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, A.; Kley, D. Volz Evaluation of the Montsouris Series of Ozone Measurements Made in the Nineteenth Century. Nature 1988, 332, 240–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xie, B.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Gong, S. The Development of an Atmospheric Aerosol/Chemistry-Climate Model, BCC_AGCM_CUACE2.0, and Simulated Effective Radiative Forcing of Nitrate Aerosols. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 2019, 11, 3816–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Peng, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Che, H.; Zhang, X. Implementation and Application of Ensemble Optimal Interpolation on an Operational Chemistry Weather Model for Improving PM2.5 and Visibility Predictions. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 4171–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Li, S.; Lai, J.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X.; Li, A. Evaluation of TROPOMI and OMI Tropospheric NO2 Products Using Measurements from MAX-DOAS and State-Controlled Stations in the Jiangsu Province of China. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, T.; Jiang, T.; Che, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Z. Impacts of PBL Schemes on PM2.5 Simulation and Their Responses to Aerosol-Radiation Feedback in GRAPES_CUACE Model during Severe Haze Episodes in Jing-Jin-Ji, China. Atmos. Res. 2021, 248, 105268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyazaki, K.; Eskes, H.; Sudo, K.; Boersma, K.F.; Bowman, K.; Kanaya, Y. Decadal Changes in Global Surface NOx Emissions from Multi-Constituent Satellite Data Assimilation. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 807–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; van der A, R.J.; Eskes, H.J.; Mijling, B.; Stavrakou, T.; van Geffen, J.H.G.M.; Veefkind, J.P. NOx Emissions Reduction and Rebound in China Due to the COVID-19 Crisis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2020GL089912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoelst, T.; Compernolle, S.; Pinardi, G.; Lambert, J.-C.; Eskes, H.J.; Eichmann, K.-U.; Fjæraa, A.M.; Granville, J.; Niemeijer, S.; Cede, A.; et al. Ground-Based Validation of the Copernicus Sentinel-5P TROPOMI NO2 Measurements with the NDACC ZSL-DOAS, MAX-DOAS and Pandonia Global Networks. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2021, 14, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Ma, P. Advances of Ozone Satellite Remote Sensing in 60 Years. ZGGX 2022, 26, 817–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veefkind, J.P.; Aben, I.; McMullan, K.; Förster, H.; de Vries, J.; Otter, G.; Claas, J.; Eskes, H.J.; de Haan, J.F.; Kleipool, Q.; et al. TROPOMI on the ESA Sentinel-5 Precursor: A GMES Mission for Global Observations of the Atmospheric Composition for Climate, Air Quality and Ozone Layer Applications. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 120, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, S.L.; Zhang, X.Y. CUACE/Dust—An Integrated System of Observation and Modeling Systems for Operational Dust Forecasting in Asia. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2008, 8, 2333–2340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Kurokawa, J.; Woo, J.-H.; He, K.; Lu, Z.; Ohara, T.; Song, Y.; Streets, D.G.; Carmichael, G.R.; et al. MIX: A Mosaic Asian Anthropogenic Emission Inventory under the International Collaboration Framework of the MICS-Asia and HTAP. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 935–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K. Multi-Resolution Emission Inventory for China (MEIC): Model Framework and 1990–2010 Anthropogenic Emissions. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, S.L.; Barrie, L.A.; Blanchet, J.-P.; von Salzen, K.; Lohmann, U.; Lesins, G.; Spacek, L.; Zhang, L.M.; Girard, E.; Lin, H.; et al. Canadian Aerosol Module: A Size-Segregated Simulation of Atmospheric Aerosol Processes for Climate and Air Quality Models 1. Module Development. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, AAC 3-1–AAC 3-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, W.R.; Middleton, P.; Chang, J.S.; Tang, X. The Second Generation Regional Acid Deposition Model Chemical Mechanism for Regional Air Quality Modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1990, 95, 16343–16367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.Q.; Zhai, S.X.; Jin, M.; Gong, S.; Wang, Y. Development of an Adjoint Model of GRAPES–CUACE and Its Application in Tracking Influential Haze Source Areas in North China. Geosci. Model Dev. 2016, 9, 2153–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountoukis, C.; Nenes, A. ISORROPIA II: A Computationally Efficient Thermodynamic Equilibrium Model for K+–Ca2+–Mg2+–NH4+–Na+–SO42−–NO3−–Cl−–H2O Aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 4639–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Zhang, X.; Gong, S.; Wang, Y.; Xue, M. Improving Aerosol Interaction with Clouds and Precipitation in a Regional Chemical Weather Modeling System. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2016, 16, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarwood, G.; Rao, S.; Yocke, M.; Whitten, G. Updates to the Carbon Bond Mechanism: CB05. Final Report Prepared for the United States Environmental Protection Agency. 2005. Available online: https://www.camx.com/Files/CB05_Final_Report_120805.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Sarwar, G.; Luecken, D.; Yarwood, G.; Whitten, G.Z.; Carter, W.P.L. Impact of an Updated Carbon Bond Mechanism on Predictions from the CMAQ Modeling System: Preliminary Assessment. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2008, 47, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Nenes, A.; Fountoukis, C. Implementation of Dust Emission and Chemistry into the Community Multiscale Air Quality Modeling System and Initial Application to an Asian Dust Storm Episode. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 10209–10237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; He, K.B.; Wang, K.; Zheng, G.J.; Duan, F.K.; Ma, Y.L.; Kimoto, T. Heterogeneous Chemistry: A Mechanism Missing in Current Models to Explain Secondary Inorganic Aerosol Formation during the January 2013 Haze Episode in North China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2015, 15, 2031–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Cai, M.; Fan, Q.; Liu, L.; Li, F.; Chan, P.W.; Deng, X.; Wu, D. An Analysis of Aerosol Liquid Water Content and Related Impact Factors in Pearl River Delta. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 1822–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Gong, S.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, L.; He, J.; Wang, Y.; Ji, D.; Feng, J.; Mo, J.; Ke, H. A New Parameterization of Uptake Coefficients for Heterogeneous Reactions on Multi-Component Atmospheric Aerosols. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 781, 146372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garane, K.; Koukouli, M.-E.; Verhoelst, T.; Lerot, C.; Heue, K.-P.; Fioletov, V.; Balis, D.; Bais, A.; Bazureau, A.; Dehn, A.; et al. TROPOMI/S5P Total Ozone Column Data: Global Ground-Based Validation and Consistency with Other Satellite Missions. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2019, 12, 5263–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Xing, Z.; Vollrath, C.; Hugenholtz, C.H.; Barchyn, T.E. Global Observational Coverage of Onshore Oil and Gas Methane Sources with TROPOMI. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 16759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pope, R.J.; Kelly, R.; Marais, E.A.; Graham, A.M.; Wilson, C.; Harrison, J.J.; Moniz, S.J.A.; Ghalaieny, M.; Arnold, S.R.; Chipperfield, M.P. Exploiting Satellite Measurements to Explore Uncertainties in UK Bottom-up NOx Emission Estimates. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2022, 22, 4323–4338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlea, E.J.; Herndon, S.C.; Nelson, D.D.; Volkamer, R.M.; San Martini, F.; Sheehy, P.M.; Zahniser, M.S.; Shorter, J.H.; Wormhoudt, J.C.; Lamb, B.K.; et al. Evaluation of Nitrogen Dioxide Chemiluminescence Monitors in a Polluted Urban Environment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2007, 7, 2691–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamsal, L.N.; Martin, R.V.; van Donkelaar, A.; Steinbacher, M.; Celarier, E.A.; Bucsela, E.; Dunlea, E.J.; Pinto, J.P. Ground-Level Nitrogen Dioxide Concentrations Inferred from the Satellite-Borne Ozone Monitoring Instrument. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2008, 113, D16308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, K., VII. Mathematical Contributions to the Theory of Evolution.—III. Regression, Heredity, and Panmixia. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. A 1896, 187, 253–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, J.W.; Russell, A.G. PM and Light Extinction Model Performance Metrics, Goals, and Criteria for Three-Dimensional Air Quality Models. Atmos. Environ. 2006, 40, 4946–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, C.J. Some Comments on the Evaluation of Model Performance. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1982, 63, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wu, S.; Dai, Z.; Wang, Y.; Du, Z.; Liu, X.; Qiu, C. High-Resolution Daily Spatiotemporal Distribution and Evaluation of Ground-Level Nitrogen Dioxide Concentration in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region Based on TROPOMI Data. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Shi, R.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Y.; Bai, K.; Zhang, J. Spatio-Temporal Characteristics of NO 2 in China and the Anthropogenic Influences Analysis Based on OMI Data. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2013, 15, 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, Z.; Cai, Z.; Wang, L.; Gu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, J. Analysis of the Spatial–Temporal Distribution Characteristics of NO2 and Their Influencing Factors in the Yangtze River Delta Based on Sentinel-5P Satellite Data. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petracchini, F.; Paciucci, L.; Vichi, F.; D’Angelo, B.; Aihaiti, A.; Liotta, F.; Paolini, V.; Cecinato, A. Gaseous Pollutants in the City of Urumqi, Xinjiang: Spatial and Temporal Trends, Sources and Implications. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2016, 7, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Gui, L.; Tao, M.; Zeng, M.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.; Gui, L.; Tao, M.; Zeng, M. Comparing the Influences on NO2 Changes in Terms of Inter-Annual and Seasonal Variations in Different Regions of China: Meteorological and Anthropogenic Contributions. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikhovtsev, M.Y.; Makarov, M.M.; Aslamov, I.A.; Tyurnev, I.N.; Molozhnikova, Y.V.; Shikhovtsev, M.Y.; Makarov, M.M.; Aslamov, I.A.; Tyurnev, I.N.; Molozhnikova, Y.V. Application of Modern Low-Cost Sensors for Monitoring of Particle Matter in Temperate Latitudes: An Example from the Southern Baikal Region. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikhovtsev, M.Y.; Molozhnikova, Y.V.; Obolkin, V.A.; Potemkin, V.L.; Lutskin, E.S.; Khodzher, T.V.; Shikhovtsev, M.Y.; Molozhnikova, Y.V.; Obolkin, V.A.; Potemkin, V.L.; et al. Features of Temporal Variability of the Concentrations of Gaseous Trace Pollutants in the Air of the Urban and Rural Areas in the Southern Baikal Region (East Siberia, Russia). Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.J.; Karim, I.; Zaman, S.U. Seasonal Dynamics and Trends in Air Pollutants: A Comprehensive Analysis of PM2.5, NO2, CO, SO2 and O3 in Houston, USA. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2025, 18, 2625–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Sun, Y.; Ma, Y.; Tan, Y.; Ren, X.; Peng, K.; Yang, S.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, X.; Ren, Y.; et al. Deviations of Boundary Layer Height and Meteorological Parameters Between Ground-Based Remote Sensing and ERA5 over the Complex Terrain of the Mongolian Plateau. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, K.; Liao, H.; Zhang, S.; Huang, K.; Lv, Y.; Shao, J.; Yu, T.; Tong, B.; et al. Investigation of Near-Global Daytime Boundary Layer Height Using High-Resolution Radiosondes: First Results and Comparison with ERA5, MERRA-2, JRA-55, and NCEP-2 Reanalyses. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 17079–17097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seinfeld, J.H.; Pandis, S.N.; Noone, K. Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change. Phys. Today 1998, 51, 88–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amedro, D.; Bunkan, A.J.C.; Berasategui, M.; Crowley, J.N. Kinetics of the OH + NO2 reaction: Rate coefficients (217–333 K, 16–1200 mbar) and fall-off parameters for N2 and O2 bath gases. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2019, 19, 10643–10657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xiu, G. Investigating the Photolysis of NO2 and Influencing Factors by Using a DFT/TD-DFT Method. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 230, 117559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.W.; Zhang, Q.; Streets, D.G.; He, K.B.; Martin, R.V.; Lamsal, L.N.; Chen, D.; Lei, Y.; Lu, Z. Growth in NOx Emissions from Power Plants in China: Bottom-up Estimates and Satellite Observations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2012, 12, 4429–4447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dari-Salisburgo, C.; Carlo, P.; Giammaria, F.; Kajii, Y.; D’Altorio, A. Laser Induced Fluorescence Instrument for NO2 Measurements: Observations at a Central Italy Background Site. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 970–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chubarova, N.Y.; Larin, I.K.; Lebedev, V.V.; Partola, V.S.; Lezina, Y.A.; Rublev, A.N. Experimental and Model Study of Changes in Spectral Solar Irradiance in the Atmosphere of Large City Due to Tropospheric NO2 Content. AIP Conf. Proc. 2009, 1100, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.