Abstract

This study investigates the influence of land use and land cover (LULC) on the distribution of extreme rainfall in the tropical coastal city of Natal, Brazil. Hourly precipitation data from eight automatic rain gauges (2014–2023) were quality-controlled, with only days containing 24 h continuous records retained. Rainfall events were classified into light (<5 mm), normal (5–10 mm), intense (40–50 mm), and extreme (>50 mm) categories, and for each category daily accumulation, duration, intensity, and maximum hourly peaks were calculated. Seasonal and spatial differences across administrative zones were assessed using multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). The LULC changes were evaluated from the MapBiomas Collection 9 dataset. Results show that between 1985 and 2020, the proportion of urbanized (non-vegetated) surfaces increased from 27.7% (42.3 km2) to 64.3% (99.7 km2), mainly in the North and West zones, replacing agricultural and vegetated areas. The East and North zones, the most urbanized areas, recorded higher daily averages of extreme rainfall in the dry season (85–88 mm) than in the wet season (78–82 mm), with maximum peaks up to 26 mm/h and durations exceeding 17 h. These findings demonstrate that rapid urban expansion intensifies rainfall extremes, underscoring the importance of incorporating LULC monitoring (e.g., MapBiomas) and spatial planning into climate adaptation strategies for medium-sized cities.

1. Introduction

Changes in land use and land cover (LULC) are among the main physical manifestations of human actions on the climate system. These modifications directly impact the surface energy balance, altering the average temperature of the lower troposphere, contributing to climate change. The regional socioeconomic consequences of climate change are unequal, with more adverse effects in countries and communities with lower response and adaptation capacity [1].

In this context, good climate governance practices developed at the municipal level are important mechanisms for mitigating Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, since cities are commonly associated with urban heat islands, among other environmental problems [2,3]. In parallel with obtaining primary GHG data, it is necessary to analyze other potential risks associated with the effects of climate change at the local level. One example is extreme rainfall, which has become increasingly intense and is expected to become even more frequent according to future projection scenarios [4,5].

International experiences, particularly in Chinese cities, show that LULC changes can significantly alter the surface energy balance, the instability of the Atmospheric Boundary Layer (ABL), and the availability of water vapor in the lower troposphere, leading to changes in local precipitation patterns, especially in cases of extreme events [6,7,8]. In the same way, the effects of LULC in Brazil on the rainfall regime have been elucidated for large urban centers, e.g., São Paulo, where extreme rainfall is more frequent in highly urbanized areas [9], intensified by urban heat island effects [10] and influenced by condensation nuclei from air pollution [11].

It is noteworthy that most socio-environmental disasters in Brazil are directly associated with the occurrence of extreme rainfall [12]. These events occur not only in large urban centers in the South and Southeast, but also throughout the Amazon [13] and the Northeast of Brazil (NEB) [14], including extreme cases in the city of Natal [15,16].

Natal is a coastal city where local LULC effects promote the occurrence of moderate Urban Heat Islands (UHIs) [17] and areas of intense thermal stress [18]. At the same time, there is a high probability of extreme rainfall events occurring during both dry and wet periods [15], while a marked decrease in wind speed, due to increased surface roughness, which is the result of the verticalization of the urban canopy, is observed [19]. It is also known that rainfall distribution in Natal shows high spatiotemporal heterogeneity and causes several socio-environmental disasters, such as landslides, flooding, and inundations [16]. Although official data on socio-environmental disaster records in Natal are scarce, some authors [15,16] identified the occurrence of a major landslide in June 2014, as well as fluvial and pluvial floods in March of 2016–2018, and another landslide in May 2017. According to the same authors, although less frequent, socio-environmental disasters associated with extreme rainfall in the city may also occur in May and July, as exemplified by the event of 2017.

Natal, due to its location in a tropical coastal zone, the pronounced spatiotemporal variability of rainfall, and the local effects of urbanization on the microclimate, is highly vulnerable to disasters such as flooding, inundations, and landslides. In this context, understanding the potential influence of LULC changes on the occurrence of extreme rainfall is essential to support climate adaptation policies and sustainable urban management. We hypothesize that LULC changes in Natal over recent decades may have intensified urban microclimatic effects, thereby enhancing atmospheric instability in the lower troposphere and leading to more intense rainfall in highly urbanized areas or those undergoing significant urban expansion.

Thus, the objective of this study is to analyze the influence of LULC changes on the rainfall regime in Natal, with emphasis on identifying spatial patterns of extreme precipitation and their association with the city’s urbanization process.

The study is structured as follows: Section 1 introduces the research problem and objectives. Section 2 describes the study area, including the physical characteristics of the city of Natal (territorial extent, climate, and rainfall regime), followed by the datasets and the statistical method used to associate rainfall events with local factors and temporal variability. Section 3 presents the results, organized into the analysis of LULC, rainfall distribution in Natal, intradiurnal characteristics of extreme rainfall, and the association between LULC changes and extreme rainfall events. Section 4 provides a discussion of the main findings, and Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Material and Methodology

2.1. Physical and Climatic Characteristics of Natal

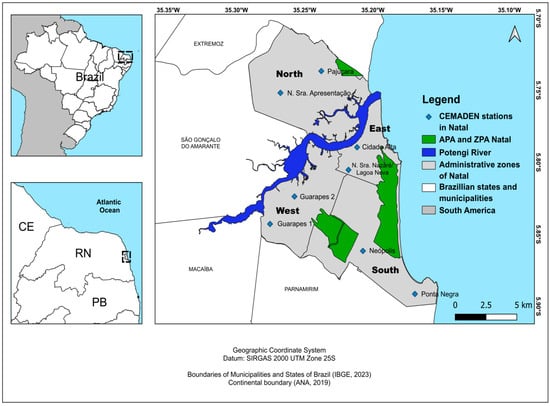

The municipality of Natal has a territorial area of 167.401 km2, distributed across four administrative zones (Figure 1): North with 58.794 km2; South covering 45.588 km2; West with 35.736 km2; and East accounting for 16.144 km2. In addition to the administrative areas, Natal contains three Environmental Protection Areas (EPA): Parque das Dunas, which covers 11.0 km2; Parque da Cidade, encompassing a total of 1.540 km2; and EPA Jenipabu, of which 0.526 km2 belong to the municipality of Natal. The total area of EPA Genipabu is 18.81 km2, but most of it is within the municipality of Extremoz.

Figure 1.

Location of the municipality of Natal/RN, location of rain gauges, EPAs, Potengi River, and the administrative zones of the city of Natal.

The climate of the region is classified as tropical wet with a dry summer (As′) according to Köppen’s climate classification [20]. The rainy season extends from March to July, while the monthly average temperature varies between 26.7 °C (February) and 24.6 °C (July) [17]. Extreme rainfall in the eastern coast of the NEB (where Natal is located) generally results from the action of five main meteorological systems: mesoscale convective systems [21,22], easterly wave disturbances [23], upper-level cyclonic vortices [24], the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) [25], frontal system and the South Atlantic Convergence Zone (SACZ) [26,27,28].

From a seasonal perspective, extreme rainfall events in the NEB are mostly identified during the rainy season, although they may occasionally occur during the dry season, particularly in November and December [14,15]. Regarding interannual variability, extreme rainfall is more frequent during La Niña years, which corresponds to the cold phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) [29,30]. Furthermore, studies have shown that the intensity of extreme events is related to the combination of La Niña and phases 4 and 5 of the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) [31,32]. Specifically in Natal, the wet season extends from March to August, whereas the dry season spans from September to February [26,28].

2.2. Hourly Precipitation Data

We used hourly precipitation data collected in situ from eight (8) automatic rain gauges installed within the boundaries of the municipality of Natal. The geographic location of each gauge is presented in Table 1, while their spatial distribution is shown in Figure 1. These instruments are part of the monitoring network of the National Center for Monitoring and Early Warning of Natural Disasters (CEMADEN). The period analyzed spans from 1 January 2014, to 31 December 2023, totaling 10 years. Although the Lagoa Nova station is officially located in the southern zone, its proximity to the Cidade Alta gauge led us to assign it to the eastern zone.

Table 1.

Geographic location of automatic rain gauges in the city of Natal that are part of the CEMADEN network, administrative zones, and percentage of days with 100% of data collected (24 h) over the 10-year analysis period.

Only days when the equipment operated for 24 continuous hours were analyzed. This criterion ensures the completeness of the rainfall records. However, it results in a non-uniform data distribution, varying from 64.5% at Ponta Negra to 88.4% at Neópolis. These percentages of data gaps are relatively lower compared to historical series obtained from conventional stations installed during the 1960s–1980s in Brazil [33].

2.3. Classification of Rainfall Events

The scientific literature is flexible regarding the definition of extreme precipitation events. Therefore, the criterion can be adapted to the specific needs of each study. In this case, the goal is to characterize rainfall above a threshold considered critical for the occurrence of socio-environmental disasters in Natal. Thus, we adopted a previously used methodology [15], which identified the occurrence of various types of disasters (fluvial floods, pluvial floods, and landslides) in cases where daily precipitation exceeded 40.0 mm in Natal.

Thus, in the present study, rainfall events potentially associated with socio-environmental disasters are classified into two categories, intense and extreme, based on a minimum threshold of 40.0 mm. Based on this, we classified rainfall in the city as follows: light (prp < 5 mm); normal (5.1 mm < prp < 10.0 mm); intense (40.0 mm < prp < 50.0 mm); and extreme (prp > 50.1 mm). We counted the total number of rainfall records in each category; thus, a maximum of 8 (rain gauges) cases per day could be recorded in the city. For each category, we calculated the following intradiurnal characteristics: daily accumulated rainfall—PREC (mm); duration—DUR (hours); intensity—INT (mm/h), calculated as the total rainfall divided by duration; and maximum hourly rainfall—PMAX (mm/h). Analyses were conducted by dividing the year into wet and dry periods, following previous climatological studies. All calculations were performed separately for each Administrative Zone (AZ), as presented in Table 1.

2.4. LULC Data

LULC data were obtained from Collection 9 of the MapBiomas project [34]. This classification is annual and covers the entire Brazilian territory. The dataset is produced using Google Earth Engine tools from Landsat satellite imagery. The spatial resolution is 30 m, and data is available from 1985 to 2023. The LULC analysis was carried out by AZ, excluding protected environmental areas (Figure 1).

MapBiomas data are categorized into three levels. Analyses presented here used the first level, consisting of five main types: forest, non-forest formation, farming, non-vegetated area, herbaceous, and water. The second and third levels provide more detail. For instance, the forest class includes natural forest formation and forest plantations. Natural forest formation is subdivided into forest formation, savanna formation, and mangrove. Urban areas fall under the non-vegetated area category, specifically labeled as “urban infrastructure,” which includes streets, highways, and buildings.

MapBiomas data have been used in various studies on urban areas in Brazil, such as the analysis of urban expansion in 21 metropolitan regions [35]; characterization of urban growth in Belém, Amazon region [36]; influence of LULC on seasonal surface temperature variation in southern Brazil [37]; and mapping the advance of urbanization, monoculture, and pasture over native forest areas in the NEB [38].

2.5. Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA)

MANOVA is an extension of ANOVA that allows the simultaneous assessment of differences between groups across multiple dependent variables. Unlike univariate ANOVA, which tests differences in the means of a single variable, MANOVA considers the correlation between two or more dependent variables, enabling a broader analysis of combined effects. This approach is particularly useful when the analyzed variables are interrelated, as it preserves the multivariate structure of the data and reduces the risk of false positive results (Type I error) from multiple independent univariate tests. The MANOVA analyses were performed using the R software (Version 4.5.2).

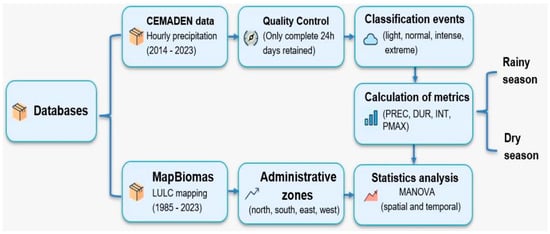

In this study, MANOVA was applied to characterize differences in intradiurnal precipitation characteristics (PREC, DUR, INT, and PMAX), considering year, seasonal period (wet and dry), and the four administrative zones (North, South, East, and West). MANOVA is especially appropriate in this case since precipitation variables are potentially correlated. Their combined analysis provides a more robust and integrated assessment of the spatial and temporal patterns of rainfall characteristics. For example, the combination of higher volume with longer duration and more intense peaks may define specific seasonal events in certain administrative zones, which would be undetected in univariate analysis. In Figure 2, we present a workflow summarizing the main methodological steps.

Figure 2.

Research Workflow for Rainfall Event Analysis and LULC Assessment in Natal, Brazil.

3. Results

3.1. LULC Evolution in Natal

3.1.1. General Aspects

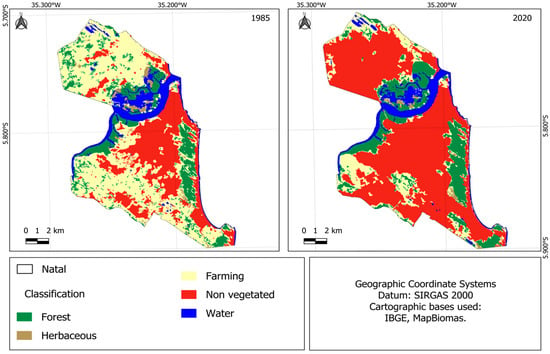

The comparative analysis of LULC in Natal between the years 1985 and 2020 revealed significant changes in the municipality’s spatial organization (Figure 3). In 1985, mosaic land use areas and savanna formations predominated in the West, North, and South zones, forming a heterogeneous landscape that was relatively preserved from anthropogenic pressures. The urbanized area, in contrast, was mainly concentrated in the East zone, indicating a more restricted urban core. Between 1985 and 2020, an intense urban expansion was observed, marked by the significant conversion of natural and rural areas into urban surfaces, especially in the northern and western zones. Urbanization advanced over areas previously occupied by land use mosaics, grassland formations, and agricultural zones, resulting in the fragmentation and isolation of remaining ecosystems.

Figure 3.

LULC maps for the city of Natal in the years 1985 and 2020, generated based on data from MapBiomas.

The evolution of LULC percentages were presented in Table 2. A continuous reduction in agricultural areas was observed, decreasing from 77.07 km2 (50.41%) in 1985 to 22.86 km2 (14.75%) in 2020. This significant decline reflects a process of land conversion from small-scale agricultural properties (locally known as granjas) to urban areas. This assertion is supported by the increase in non-vegetated areas in the city, which expanded from 42.30 km2 (27.67%) in 1985 to 99.66 km2 (64.31%) in 2020.

Table 2.

LULC evolution considering the five (5) main land cover classes for the total area of the city of Natal. Area values are expressed in km2, with their respective percentages shown in parentheses.

Simultaneously, there was a reduction in herbaceous and shrub vegetation from 3.36 km2 (2.20%) to 1.34 km2 (0.86%). Forested areas showed a slight increase from 19.89 km2 (13.01%) to 20.59 km2 (13.29%), possibly as a result of environmental conservation policies or natural regeneration in specific sectors of the city. Water bodies experienced slight fluctuations, changing from 13.63 km2 (4.11%) in 1985 to 11.86 km2 (3.57%) in 2020.

Therefore, the main LULC change observed in Natal between 1985 and 2020 was the conversion of agricultural production areas and other land uses, as well as shrub and herbaceous vegetation, into non-vegetated urban surfaces. However, these transformations did not occur uniformly across the city. Thus, in the following sections, the LULC changes within each AZ will be detailed.

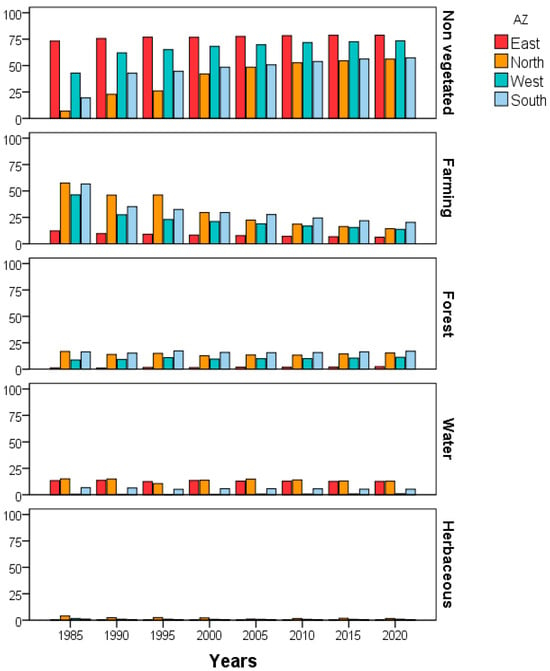

3.1.2. LULC Evolution by Administrative Zones

The LULC evolution over the year by Administrative Zone is shown in Figure 4. The East zone exhibited a strong predominance of non-vegetated areas throughout the entire period from 1985 to 2020. In 1985, this class already occupied 11.82 km2 (73.19%) of the region’s surface, and this percentage remained high, reaching 12.71 km2 (78.76%) in 2020. This region remained a densely urbanized area, with minimal changes in terms of revegetation or recovery of natural green spaces. Conversely, farming areas decreased from 1.96 km2 (12.16%) in 1985 to 1.00 km2 (6.22%) in 2020. Forest areas remained very limited, increasing slightly from 0.20 km2 (1.26%) in 1985 to 0.39 km2 (2.40%) in 2020, indicating an absence of effective forest regeneration processes in the most densely populated part of the city. There were no records of herbaceous or shrub vegetation, and the water bodies coverage declined by 0.12 km2, which, although representing less than 1% of the total area, is directly related to the Potengi River, the city’s main freshwater body.

Figure 4.

LULC evolution over the years by Administrative Zones in Natal from 1985 to 2020.

The North zone exhibited significant changes, with a notable reduction in farming areas. In 1985, agriculture occupied 33.8 km2 (57.49%), decreasing to 8.41 km2 (14.30%) in 2020. Simultaneously, there was a substantial increase in the non-vegetated area, expanding from 4.01 km2 (6.81%) in 1985 to 33.00 km2 (56.12%) in 2020. This LULC transformation reflects an intense urbanization and territorial restructuring, replacing rural activities with urban expansion. The forest class slightly decreased from 9.85 km2 (16.75%) in 1985 to 9.00 km2 (15.31%) in 2020. Similarly, both herbaceous and shrubby vegetation and water classes experienced relative reductions. Herbaceous vegetation declined from 3.94% to 1.52%, and the presence of water bodies decreased from 15.01% to 12.80%. These reductions suggest that urban pressure extended beyond agricultural areas, also affecting fragile ecosystems such as wetlands and marshes.

The Western zone showed similarities to the North zone, for example, agricultural land decreased from 20.22 km2 (56.58%) in 1985 to 7.22 km2 (20.22%) in 2020, indicating a process of continuous, however more gradual, urbanization compared to the North zone. Conversely, the non-vegetated area class increased from 6.92 km2 (19.37%) in 1985 to 20.48 km2 (57.30%) in 2020, surpassing agriculture as the dominant land cover type from the early 2000s onward. Forest and water classes remained relatively stable between 1985 and 2020, indicating the presence of small vegetation patches that are either still protected or undergoing a slow, likely spontaneous, regeneration process. Water bodies, however, declined by 0.49 km2 over the same period.

In the South zone, the changes were also significant, with a sharp reduction in farming areas, which declined from 21.09 km2 (46.27%) in 1985 to 6.23 km2 (13.66%) in 2020. The rate of urbanization, although intense, occurred in a more planned manner compared to the North and West zones. This is consistent with the presence of middle-class neighborhoods and important institutional and commercial areas. However, this did not prevent a substantial increase in non-vegetated areas, which expanded from 19.56 km2 (42.90%) to 33.47 km2 (73.43%). Conversely, the South zone experienced the largest increase in forested areas in the city, growing from 3.97 km2 (8.72%) to 5.12 km2 (11.24%). Finally, the herbaceous and shrubby vegetation, and water bodies classes maintained a limited presence in the South zone. Herbaceous vegetation remained around 0.8%, and water bodies fluctuated between 0.5% and 0.8% of the surface area.

3.2. Distribution of Rainfall Events in Natal by Administrative Zone

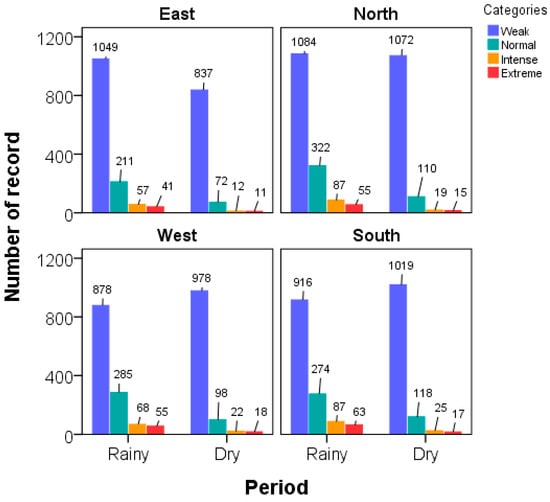

Figure 5 presents the distribution of rainfall occurrences by category across the four AZ of Natal. Light rainfall predominated in all zones, especially in the North zone, which recorded 1084 events (71.5%) in the wet season and 1072 (84.4%) in the dry season. The East, West, and South zones also showed a high frequency of light rainfall in both periods. Normal rainfall occurred less frequently, being more common in the wet season of the North zone (322 records) and the South zone (274 records), followed by the West zone (285 records); the other zones showed lower counts.

Figure 5.

Number of rainfall events by category, distributed across the four AZ of Natal, considering the dry and wet periods.

Intense rainfall was more frequent during the wet season, with highlights in the West zone (68 records, 5.7%) and the South zone (63 records, 4.8%). The North zone recorded 87 intense events (5.7%) in the wet season and 19 (1.5%) in the dry season, while the East zone registered 57 (4.2%) and 12 (1.2%) events, respectively. For extreme rainfall, the highest number of cases occurred in the South zone (63 cases), followed by the North and West (55 each), and East (41) during the wet season. In the dry season, the highest number of extreme events was observed in the West zone (18), followed by South (17), North (15), and East (11).

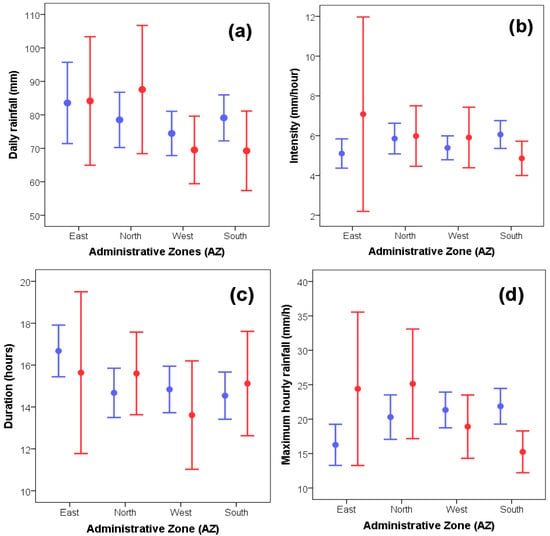

3.3. Analize of Extreme Rainfall in Natal

Intradiurnal characteristics of extreme rainfall events by AZ and seasonal period are presented in Figure 6. For average daily rainfall (Figure 6a), the East and North zones recorded higher averages during the dry season (85.0 mm and 88.0 mm, respectively), surpassing values observed in the wet season (82.0 mm and 78.0 mm). In contrast, the West and South zones experienced more intense extreme rainfall in the wet season (averages of 74.0 mm and 79.0 mm) compared to the dry season (70.0 mm and 72.0 mm). The East and North zones also had wider 95% confidence intervals, especially in the dry season. Figure 6b shows INT (mm/h), which was relatively homogenous across ZA, ranging mostly between 4.5 mm/h and 6.5 mm/h. However, the East zone during the dry season stood out with the highest average (7.2 mm/h) and a broader confidence interval (2.0 mm/h to 12.0 mm/h). In the other AZ, differences between wet and dry periods were less pronounced.

Figure 6.

Daily rainfall (a), intensity (b), duration (c), and maximum hourly rainfall (d) for extreme precipitation events (>50.1 mm/day) as a function of the Administrative Zones of the city of Natal. The bars represent the 95% confidence interval. Blue bars correspond to the rainy season, while red bars represent the dry season.

Figure 6c presents DUR (hours) for extreme precipitation events. The East zone had the highest average durations, especially in the wet season (~17 h). During the dry season, despite a shorter average duration (~15.5 h), variability remained high, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from approximately 12 to 20 h. In the wet season, the North zone had an average of ~15 h, while the West and South zones were around 14.5 h, showing a 2.0 to 2.5 h difference compared to the East zone. The North, West, and South zones exhibited average durations of 14–14.5 h, about 1.0 to 1.5 h less than in the East.

Figure 6d presents PMAX (mm/h) for extreme rainfall. The East, North, and West zones had the highest peak intensities in the dry season. The East zone stood out with the highest peak (26.0 mm/h), with a confidence interval from 12.0 to 36.0 mm/h. In contrast, the wet season average dropped to 17.0 mm/h, with reduced variability. In the North and West, dry season PMAX also reached 25 mm/h and 23 mm/h, respectively, surpassing the 21 mm/h recorded in the wet season. In the South, however, rainfall was more intense in the wet season (23.0 mm/h) than in the dry season (16.0 mm/h).

In this sense, the results presented indicate that East and North zones, which exhibit the highest levels of urbanization, concentrated the most pronounced rainfall anomalies when compared to the West and South. The daily rainfall during the dry season exceeded that of the wet season, accompanied by greater variability in event duration and intensity. The East zone, in particular, recorded longer-lasting events (up to ~17 h in the wet season) and the highest peak intensities in the dry season (26.0 mm/h), with wide confidence intervals indicating strong variability. Similarly, the North zone presented longer durations and high intensities, reinforcing the pattern of more extreme and persistent rainfall in areas with greater land use change.

3.4. Multivariate Analysis of Rainfall

It is important to emphasize that the AZ factor (Administrative Zone) introduces the urbanization component into the analysis, since, as observed in Section 3.1.2 of the results, the non-urbanized areas of the Eastern and Northern zones differ considerably from those of the Southern and Western zones. Thus, indirectly, the AZ factor represents the urbanization process in the MANOVA.

MANOVA results by rainfall category are presented in Table 3. Light rainfall is significantly influenced by all main factors (Year—Y, Period—P, Administrative Zone—AZ) and by the interaction Y × P (p < 0.01). The P factor was the most expressive, showing extremely high F-values for all variables (e.g., F = 128.21 for PREC), confirming the seasonal pattern characteristic of this event type.

Table 3.

F-value and p-value of the MANOVA for the different rainfall categories.

For normal rainfall, the Year factor remained statistically significant for all variables (p < 0.01), indicating a clear influence of interannual variability. Conversely, AZ was significant for PMAX, DUR, and INT (p < 0.05), suggesting spatial differences in these rainfall aspects. The P factor alone was not significant for any variable, indicating that seasonality plays a lesser role in this rainfall category. The Y × AZ interaction again stood out, suggesting that spatial heterogeneity of rainfall is also modulated by interannual variability in cases of normal rain.

Intense rainfall showed a more specific influence pattern. AZ stood out for PMAX (F = 12.06), DUR (F = 5.17), and INT (F = 3.34). In contrast, PREC was not significantly impacted by the factors analyzed. The Y × AZ interaction was significant for PMAX, DUR, and INT (p < 0.1), suggesting that local characteristics and interannual variability jointly influence intense rainfall behavior. The Year factor reached p < 0.15, with lower F-values compared to AZ and P effects, indicating that large-scale patterns controlling interannual variability are less significant compared to local effects and rainfall seasonality in the region.

For extreme rainfall, the Year factor was the most relevant among all categories, showing statistical significance for all variables (F = 10.56 to 19.23), highlighting the importance of interannual variability in critical events. AZ was also significant for PREC, PMAX, and INT, but not for DUR. The P factor was not statistically significant for the four variables (p > 0.01), indicating that these events may occur randomly throughout the year. On the other hand, the P × Y interaction significantly impacted all variables, showing that extreme events are more sensitive to combinations of seasonality and interannual variability. Furthermore, the Y × P × AZ interactions showed statistical significance (p < 0.05) for all variables.

4. Discussion

Rainfall distribution in Natal follows a seasonal pattern, where the dry period is marked by sporadic extreme rainfall events, while light rainfall occurs as frequently as in the rainy season. In contrast, normal, intense, and extreme rainfall events are more frequent during the rainy season. This marked seasonality results from the ITCZ influence between March and May and mesoscale convective systems during June and July, as indicated by previous climatological studies [22,23]. On the other hand, intense and extreme rainfall events during the dry season (particularly in November and December) are mainly caused by the formation of upper-level cyclonic vortices, which are a typical manifestation of spring and summer circulation over South America [24,26].

The changes in LULC in Natal between 1985 and 2020 reveal a pronounced urbanization process, reflecting common patterns observed in medium- to large-sized Brazilian urban centers. Spatial analysis showed a transition from a landscape predominantly composed of savanna formations and mosaic land use (with lower anthropogenic pressure and greater heterogeneity) to a predominantly urban scenario, especially in the North and East zones. This urban expansion, at the expense of natural and rural areas, not only entails the direct replacement of native vegetation but also leads to habitat fragmentation and ecological remnant isolation, compromising ecological connectivity and the supply of essential ecosystem services.

Previous studies indicated that urbanization intensifies the occurrence of extreme rainfall events, both through alterations in urban surface properties (such as albedo, heat capacity, and surface roughness) and by inducing atmospheric instabilities associated with UHIs [3,6]. Therefore, although not directly comparable due to the substantial differences between the cities, this findings for the city of Natal are consistent with those found in the international scientific literature and in major Brazilian cities [9,10,11], regarding the influence of LULC on rainfall characteristics, particularly intense and extreme events in urban environments.

The results presented in Figure 4 indicate that the North and East zones are precisely those where the intradiurnal characteristics of precipitation are most intense. This suggests a likely association between pronounced LULC changes (in the North zone) and the predominance of urbanized areas (in the East zone), both of which appear to be linked to the occurrence of more intense rainfall compared to regions with less marked LULC transformations.

Our analyses clearly indicate distinct characteristics (PREC, PMAX, DUR, and INT) of extreme rainfall between the East and North zones compared to the West and South zones. Indeed, extreme rainfall events are more intense, last longer, and exhibit higher maximum hourly rates in areas where the LULC analysis (Figure 3) shows a predominance of non-vegetated surfaces (East zone) or a greater conversion of pasture and forest areas into non-vegetated surfaces over the study period (North zone). A possible explanation for this pattern is the modification of the surface energy balance, since areas with reduced vegetation cover are dominated by sensible heat flux, which warms the lower troposphere and enhances local convection, wchich is one of the primary drivers of the diurnal precipitation cycle in tropical regions, such as the coastal zones of Northeast Brazil, and has been identified in previous studies [39] as the main mechanism controlling the diurnal precipitation cycle in the Natal region.

It is noteworthy that, in addition to the eastern zone, the northern and western zones also recorded a high frequency of extreme events, consistent with the intense LULC changes observed in these areas. The predominance of light rainfall across all zones, including the most urbanized ones, underscores that although LULC exerts an important modulatory role, it interacts with large-scale climatic drivers [25,29,32], as further evidenced by the influence of the “Year” factor in the MANOVA. In this context, the MANOVA results highlight that both interannual variability and administrative zoning are key determinants of extreme rainfall occurrence in Natal, corroborating findings reported for the State of São Paulo [9,10,11,40] and its metropolitan area [41], where reduced dependence on seasonality has been observed, with extreme events occurring relatively randomly throughout the year.

5. Conclusions

This study provides novel and relevant evidence on how land use and land cover (LULC) changes influence precipitation characteristics in Natal, a medium-sized tropical coastal city. By using a high-quality, long-term hourly rainfall dataset collected in situ from eight CEMADEN stations (2014–2023), the research demonstrates that rapid and spatially heterogeneous urbanization has intensified extreme precipitation events. The most urbanized areas (East and North zones) concentrated the anomalies with more intense, longer-lasting events and higher maximum hourly rates, particularly where natural vegetation and pastures were converted into impervious surfaces. These findings reveal that urban-induced microclimatic changes, previously reported mainly in large Brazilian metropolitan regions such as São Paulo, are also evident in medium-sized coastal cities, a geographical context that remains underrepresented in the scientific literature.

From a methodological standpoint, the study advances the field by applying MANOVA, which enables a robust and integrated assessment of precipitation metrics considering their inherent correlation. The results highlight that interannual variability and spatial configuration (urbanization gradient) exert a stronger influence on extreme rainfall occurrences than seasonality, indicating that critical events may occur throughout the year, not only during the wet season. This reinforces the urgency for improved urban and environmental governance, emphasizing the integration of LULC monitoring tools, such as MapBiomas, into climate adaptation strategies for medium-sized cities to mitigate hydrometeorological risks and strengthen climate resilience.

On the other hand, the study presents some important limitations: (i) the distribution of precipitation data is not uniform among the eight stations analyzed, due to the strict quality control criterion that considered only days with complete 24 h records, resulting in different levels of data availability across stations; (ii) the urbanization component was indirectly represented in the statistical analysis by using administrative zones as a proxy, since the heterogeneity between urbanized and non-urbanized areas within the city prevents a direct distinction of the urban effect; and (iii) there is a scarcity of official socio-environmental disaster records in Natal, which limits a more accurate contextualization of the impacts associated with extreme precipitation events and requires reliance on previous studies as reference.

Overall, these findings corroborate our initial hypothesis that LULC changes in Natal over recent decades have intensified urban microclimatic effects, contributing to stronger and more persistent extreme rainfall events in areas with greater urban expansion or consolidated urbanization. This provides unprecedented evidence for a medium-sized Brazilian city and aligns with results from larger urban centers, such as São Paulo.

The study reinforces the need to integrate LULC monitoring tools, such as MapBiomas, into urban planning to mitigate hydrometeorological risks. Strengthening environmental governance, protecting remaining natural areas, and promoting sustainable urban development are critical to reducing vulnerability and enhancing climate resilience in Natal and other cities facing similar challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.d.P.N.M. and C.M.S.e.S.; investigation, T.d.P.N.M. and C.M.S.e.S.; methodology, C.M.S.e.S., T.d.P.N.M., I.D.G.d.M., K.R.M., T.N.M.d.S., G.Y.P.d.C., C.L.B., V.L., J.I.A.d.M.S., P.E.S.d.O., C.d.H., F.A.C.d.M., D.T.R., G.V.S.d.N., M.B.d.N. and G.B.C.; validation, C.M.S.e.S., T.d.P.N.M., I.D.G.d.M., K.R.M., T.N.M.d.S., G.Y.P.d.C., C.L.B., V.L., J.I.A.d.M.S., P.E.S.d.O., C.d.H., F.A.C.d.M., D.T.R., G.V.S.d.N., M.B.d.N. and G.B.C.; formal analysis, C.M.S.e.S., T.d.P.N.M., I.D.G.d.M., K.R.M., T.N.M.d.S., G.Y.P.d.C., C.L.B., V.L., J.I.A.d.M.S., P.E.S.d.O., C.d.H., F.A.C.d.M., D.T.R., G.V.S.d.N., M.B.d.N. and G.B.C.; writing---original draft preparation, C.M.S.e.S. and T.d.P.N.M.; writing---review and editing, C.M.S.e.S., T.d.P.N.M., I.D.G.d.M., K.R.M., T.N.M.d.S., G.Y.P.d.C., C.L.B., V.L., J.I.A.d.M.S., P.E.S.d.O., C.d.H., F.A.C.d.M., D.T.R., G.V.S.d.N., M.B.d.N. and G.B.C.; funding acquisition, C.M.S.e.S., T.d.P.N.M. and G.B.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Federal University of Western Pará (UFOPA) in PAPCIQ program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) to the grant of Productivity Scholarship of Cláudio M. Santos e Silva (n° 312222/2023-8) and Gabriel Brito Costa (n° 304809/2025-0).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zimm, C.; Mintz-Woo, K.; Brutschin, E.; Hanger-Kopp, S.; Hoffmann, R.; Kikstra, J.S.; Kuhn, M.; Min, J.; Muttarak, R.; Pachauri, S. Justice considerations in climate research. Nat. Clim. Change 2024, 14, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulpiani, G. On the linkage between urban heat island and urban pollution island: Three-decade literature review towards a conceptual framework. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 751, 141727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Z. Relationship between land surface temperature and air quality in urban and suburban areas: Dynamic changes and interaction effects. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 118, 106043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Donat, M.G.; Zong, S.; Alexander, L.V.; Manzanas, R.; Kruger, A.; Choi, G.; Salinger, J.; He, H.S.; Li, M.-H. Extreme Precipitation on Consecutive Days Occurs More Often in a Warming Climate. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2022, 103, 1130–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, P.B.R.; Amanguah, E.; McNally, D.; Espinoza, M.; Ghaedi, H.; Reilly, A.C.; Hendricks, M.D. Navigating the definition of urban flooding: A conceptual and systematic review of the literature. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 90, 2796–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, C.; Leung, R.; Wang, H.; Yang, B.; Fan, J.; Yan, H.; Yang, X.-Q.; Liu, D. Urbanization-induced urban heat island and aerosol effects on climate extremes in the Yangtze River Delta region of China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 5439–5457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Fung, K.Y.; Tam, C.-Y.; Wang, Z. Urbanization Impacts on Pearl River Delta Extreme Rainfall Sensitivity to Land Cover Change Versus Anthropogenic Heat. Earth Space Sci. 2021, 8, e2020EA001536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xu, G.; Gao, H. Characteristics of Summer Hourly Extreme Precipitation Events and Its Local Environmental Influencing Factors in Beijing under Urbanization Background. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, C.B.; Campos, T.L.O.B.; Rafee, S.A.A.; Martins, J.A.; Grimm, A.M.; Freitas, E.D.d. Extreme Rainfall Events in the Macrometropolis of São Paulo: Trends and connection with climate oscillations. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2021, 60, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva Dias, M.A.F.; Dias, J.; Carvalho, L.M.V.; Freitas, E.D.; Dias, P.L.S. Changes in extreme daily rainfall for São Paulo, Brazil. Clim. Change 2013, 116, 705–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picolo, M.F.; Campos, T.L.O.B.; Freitas, E.D.d. Relationship Between Urbanization and Precipitation in the São Paulo Macrometropolis; The Urban Book Series; Springer Nature: Zürich, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palharini, R.; Vila, D.; Rodrigues, D.; Palharini, R.; Mattos, E.; Undurraga, E. Analysis of Extreme Rainfall and Natural Disasters Events Using Satellite Precipitation Products in Different Regions of Brazil. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, E.B.; Ferreira, D.B.S.; Anjos, L.J.S.; Cunha, A.C.; Silva, J.A., Jr.; Coutinho, E.C.; Sousa, A.M.L.; Souza, P.J.O.P.; Correa, W.P.M.; Dias, T.S.S.; et al. Intensification of Natural Disasters in the State of Pará and the Triggering Mechanisms Across the Eastern Amazon. Atmosphere 2024, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.T.; Silva, C.M.S.e.; Lima, K.C. Climatology and trend analysis of extreme precipitation in subregions of Northeast Brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2017, 130, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.T.; Gonçalves, W.A.; Spyridês, M.H.C.; Andrade, L.M.B.; Souza, D.O.d.; Araujo, P.A.A.d.; Silva, A.C.N.d.; Silva, C.M.S.e. Probability of occurrence of extreme precipitation events and natural disasters in the city of Natal, Brazil. Urban Clim. 2021, 35, 100753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.S.M.; Andrade, L.M.B.; Spyridês, M.H.C.; Lima, K.C.; Silva, P.E.d.; Batista, D.T.; Lara, I.A.R.d. ENVIRONMENTAL DISASTERS IN NORTHEAST BRAZIL: Hydrometeorological, social and sanitary factors. Weather. Clim. Soc. 2021, 541, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, F.F.; Gonçalves, W.A.; Andrade, L.M.B.; Villavicencio, L.M.M.; Silva, C.M.S. Assessment of Urban Heat Islands in Brazil based on MODIS remote sensing data. Urban Clim. 2021, 35, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapola, D.M.; Braga, D.R.; Giulio, G.M.d.; Torres, R.R.; Vasconcellos, M.P. Heat stress vulnerability and risk at the (super) local scale in six Brazilian capitals. Clim. Change 2019, 154, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, G.C.; Rodrigues, D.T.; Silva, C.M.S.e.; Costa, P.C.d.S. Evolution of wind speed observed in Brazil between 1961 and 2020. Int. J. Climatol. 2024, 44, 1932–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvares, C.A.; Stape, J.L.; Sentelhas, P.C.; Gonçalves, J.L.d.M.; Sparovek, G. Köppen’s climate classification map for Brazil. Meteorol. Z. 2013, 22, 711–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyra, M.J.A.; Fedorova, N.; Levit, V. Mesoscale convective complexes over northeastern Brazil. J. S. Am. Earth Sci. 2022, 118, 103911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, N.S.; Santos, C.A.C.d.; Silva, M.T.; Gomes, H.B.; Ferreira, R.R.; Silva, M.L.d.; Silva, C.M.S.e.; Oliveira, C.P.d.; Medeiros, J.; Giovannettone, J. Landslides Triggered by the May 2017 Extreme Rainfall Event in the East Coast Northeast of Brazil. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, H.B.; Ambrizzi, T.; Silva, B.F.P.d.; Hodges, K.; Dias, P.L.S.; Herdies, D.L.; Silva, M.C.L.; Gomes, H.B. Climatology of easterly wave disturbances over the tropical South Atlantic. Clim. Dyn. 2019, 53, 1393–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.S.d.; Gonçalves, W.A.; Mendes, D. Climatology of the dynamic and thermodynamic features of upper tropospheric cyclonic vortices in Northeast Brazil. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 57, 3413–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utida, G.; Cruz, F.W.; Etourneau, J.; Bouloubassi, I.; Schefuß, E.; Vuille, M.; Novello, V.F.; Prado, L.F.; Sifeddine, A.; Klein, V. Tropical South Atlantic influence on Northeastern Brazil precipitation and ITCZ displacement during the past 2300 years. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.T.; Lima, K.C.; Silva, C.M.S.e. Synoptic environment associated with heavy rainfall events on the coastland of Northeast Brazil. Adv. Geosci. 2013, 35, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorova, N.; Levit, V.; Cruz, C.D.d. On Frontal Zone Analysis in the Tropical Region of the Northeast Brazil. Pure Appl. Geophys. 2016, 173, 1403–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, D.H.M.C.; Lima, K.C. What is the return period of intense rainfall events in the capital cities of the northeast region of Brazil? Atmos. Sci. Lett. 2019, 20, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luiz-Silva, W.; Oscar-Júnior, A.C.; Cavalcanti, I.F.A.; Treistman, F. An overview of precipitation climatology in Brazil: Space-time variability of frequency and intensity associated with atmospheric systems. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2021, 66, 289–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.S.; Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.d.; Santos, P.J.d.; Correia Filho, W.L.F.; Gois, G.d.; Blanco, C.J.C.; Teodoro, P.E.; Silva Junior, C.A.d.; Santiago, D.d.B.; Souza, E.d.O. Rainfall extremes and drought in Northeast Brazil and its relationship with El Niño–Southern Oscillation. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 41, 2111–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.S.; Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.d.; Costa, M.S.; Cardoso, K.R.A.; Shah, M.; Shahzad, R.; Silva, L.F.F.d.; Romão, W.M.d.O.; Singh, S.K.; Mendes, D. Effects of extreme phases of El Niño–Southern Oscillation on rainfall extremes in Alagoas, Brazil. Int. J. Climatol. 2023, 43, 7700–7721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valadão, C.E.A.; Carvalho, L.M.V.; Lucio, P.S.; Chaves, R.R. Impacts of the Madden-Julian oscillation on intraseasonal precipitation over Northeast Brazil. Int. J. Climatol. 2016, 37, 1859–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.T.; Gonçalves, W.A.; Silva, C.M.S.e.; Spyridês, M.H.C.; Lúcio, P.S. Imputation of precipitation data in northeast Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Ciências 2023, 95, e20210737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, C.M.; Shimbo, J.Z.; Rosa, M.R.; Parente, L.L.; Alencar, A.A.; Rudorff, B.F.T.; Hasenack, H.; Matsumoto, M.; Ferreira, L.G.; Souza-Filho, P.W.M. Reconstructing Three Decades of Land Use and Land Cover Changes in Brazilian Biomes with Landsat Archive and Earth Engine. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriota, E.G.; Bertrand, G.F.; Almeida, C.N.; Claudino, C.M.A.; Coelho, V.H.R. Heat the road again! Twenty years of surface urban heat island intensity (SUHII) evolution and forcings in 21 tropical metropolitan regions in Brazil from remote sensing analyses. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 113, 105629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtado, L.S.; Pereira, R.V.S.; Souza, E.B.d. Hemeroby Mapping of the Belém Landscape in Eastern Amazon and Impact Study of Urbanization on the Local Climate. Urban Sci. 2024, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.P.; Menezes, G.P.; Figueiredo, G.K.D.A.; Mello, K.d.; Valente, R.A. Impacts of urban landscape pattern changes on land surface temperature in Southeast Brazil. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 33, 101142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia Filho, W.L.F.; Oliveira-Júnior, J.F.d.; Santos, C.T.B.d.; Batista, B.A.; Santiago, D.d.B.; Silva Junior, C.A.d.; Teodoro, P.E.; Costa, C.E.S.d.; Silva, E.B.d.; Freire, F.M. The influence of urban expansion in the socio-economic, demographic, and environmental indicators in the City of Arapiraca-Alagoas, Brazil. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 25, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos e Silva, C.M.; Rodrigues, D.T.; Medeiros, F.; Valentim, A.M.; de Araújo, P.A.A.; da Silva Pinto, J.; Mutti, P.R.; Mendes, K.R.; Bezerra, B.G.; de Oliveira, C.P.; et al. Diurnal cycle of precipitation in Brazil. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 2024, 155, 7811–7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, M.C.; Rosa, M.B. Heat waves in São Paulo State, Brazil: Intensity, duration, spatial scope, and atmospheric characteristics. Int. J. Climatol. 2023, 43, 3782–3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valverde, M.C.; Coelho, L.H.; Cardoso, A.O.; Paiva Junior, H.; Brambila, R.; Boian, C.; Martinelli, P.C.; Valdambrini, N.M. Urban climate assessment in the ABC Paulista Region of São Paulo, Brazil. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).