1. Introduction

Air pollution is widely recognized as one of the most significant environmental threats to human health worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) identifies ambient air pollution as a major contributor to morbidity and mortality, responsible for millions of premature deaths annually, primarily through cardiovascular and respiratory diseases [

1]. In 2015, nearly nine million deaths—approximately one in six worldwide—were attributed to air pollution exposure, with more than 60% due to cardiovascular causes [

1,

2]. Despite global improvements in air quality standards, epidemiological evidence continues to show that even low concentrations of air pollutants are linked with elevated cardiovascular risks [

3,

4].

A large and consistent body of evidence supports a strong association between both short-term and long-term exposure to air pollutants and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [

5,

6,

7]. Studies have shown that short-term increases in particulate matter (PM) and gaseous pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide (NO

2) and sulfur dioxide (SO

2) correspond with increased hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and heart failure [

6,

7]. A comprehensive meta-analysis demonstrated that a 10 μg/m

3 increase in particulate matter—both coarse particles (PM

10, particulate matter ≤10 μm) and fine particles (PM

2.5, particulate matter ≤2.5 μm)—was associated with an approximately 1–2% rise in cardiovascular hospitalizations [

8], with no separate effect estimates reported for the two fractions [

8]. Long-term exposure to fine particulate matter (PM

2.5) is even more concerning; cohort studies across Europe and North America reveal significant increases in the incidence and mortality of ischemic heart disease, stroke, and heart failure per 10 µg/m

3 increment in annual PM

2.5 exposure [

5,

9,

10]. These findings emphasize that there is likely no “safe” threshold for exposure to many air pollutants as risks persist even below current WHO and EU limits [

3,

8].

The pathophysiological mechanisms linking air pollution to cardiovascular disease (CVD) have been extensively studied. Inhaled particulate matter and gaseous pollutants induce systemic oxidative stress, inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and autonomic imbalance, which in turn promote hypertension, atherosclerosis, thrombogenesis, and arrhythmogenesis [

2,

3,

6]. Experimental and clinical studies suggest that chronic exposure contributes to arterial remodeling and impaired cardiac function, ultimately leading to the manifestation of cardiovascular events [

4,

5]. Air pollution thus represents a modifiable but persistent determinant of cardiovascular health globally.

Among major anthropogenic sources, fossil fuel combustion—particularly from coal and lignite—is a dominant contributor to ambient particulate and gaseous pollution [

11]. Lignite (brown coal) combustion generates high emissions of particulate matter (PM

10), sulfur dioxide (SO

2), nitrogen oxides (NO, NO

2, NO

x), and trace metals. These emissions are associated with local air quality degradation and adverse population health outcomes [

11,

12]. Numerous studies have documented that communities near coal-fired power plants experience elevated risks of respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity due to chronic exposure to these pollutants [

7,

9,

10].

In Greece, lignite has historically been the cornerstone of national electricity production. Western Macedonia, in particular, has hosted the largest lignite mining and combustion complex in Southeastern Europe, operated by the Public Power Corporation (DEI) [

11]. This region encompasses the main DEI power stations in Kozani, Ptolemaida, Amyntaio, and Florina, with total installed capacity exceeding 4 GW. Decades of lignite exploitation have led to the accumulation of pollutants in the atmosphere, soil, and water systems. Monitoring data show that PM

2.5 and PM

10 levels in the area have often exceeded both European and national thresholds, especially during periods of intense power plant activity and unfavorable meteorological conditions [

11,

12]. Evagelopoulos et al. [

11] identified consistent seasonal and spatial variation in PM

10 and PM

2.5 concentrations in Western Macedonia, largely attributed to lignite combustion and mining operations. Similarly, Pavloudakis et al. [

13] reported that particulate concentrations remained elevated even after partial decommissioning of mining operations, reflecting the long-term environmental legacy of lignite use. In parallel, Manousakas et al. [

14] analyzed PM

10 sources at Megalopolis—a lignite-based area in southern Greece—and confirmed that combustion-related components dominate particle composition and are closely linked with both local emission sources and meteorological conditions.

Despite extensive environmental assessments, few studies have examined the direct epidemiological impact of air pollution from lignite combustion on human health in Western Macedonia. Previous investigations primarily addressed respiratory outcomes; however, cardiovascular effects have received less systematic attention. The present study addresses this gap by analyzing hospital admissions for cardiovascular conditions in relation to daily pollutant concentrations in Western Macedonia. The analysis focuses on five key pollutants emitted from DEI’s lignite-fired plants—PM10, SO2, NO, NO2, and total NOx—and evaluates their statistical associations with cardiovascular hospitalizations across multiple subregions.

Previous epidemiological analyses in similar settings have shown that short-term fluctuations in ambient pollutant concentrations may correspond to changes in cardiovascular hospital admissions [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. These patterns—particularly involving PM

10 and NO

2 in areas influenced by lignite combustion—underscore the relevance of examining pollutant–health associations in Western Macedonia. This scientific context motivates the objectives of our study, while the detailed methodology is presented in the dedicated

Section 2.

This study contributes novel regional evidence to the expanding literature on air pollution and cardiovascular disease by focusing on a lignite-dependent area with a distinctive pollution profile. The results support the hypothesis that emissions from lignite power plants negatively affect cardiovascular health, as reflected by increases in hospital admissions during periods of higher pollutant concentrations. By providing quantitative evidence from Western Macedonia, this work underscores the public health significance of environmental exposures in coal-based regions and strengthens the global evidence base regarding the cardiovascular impacts of air pollution.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data

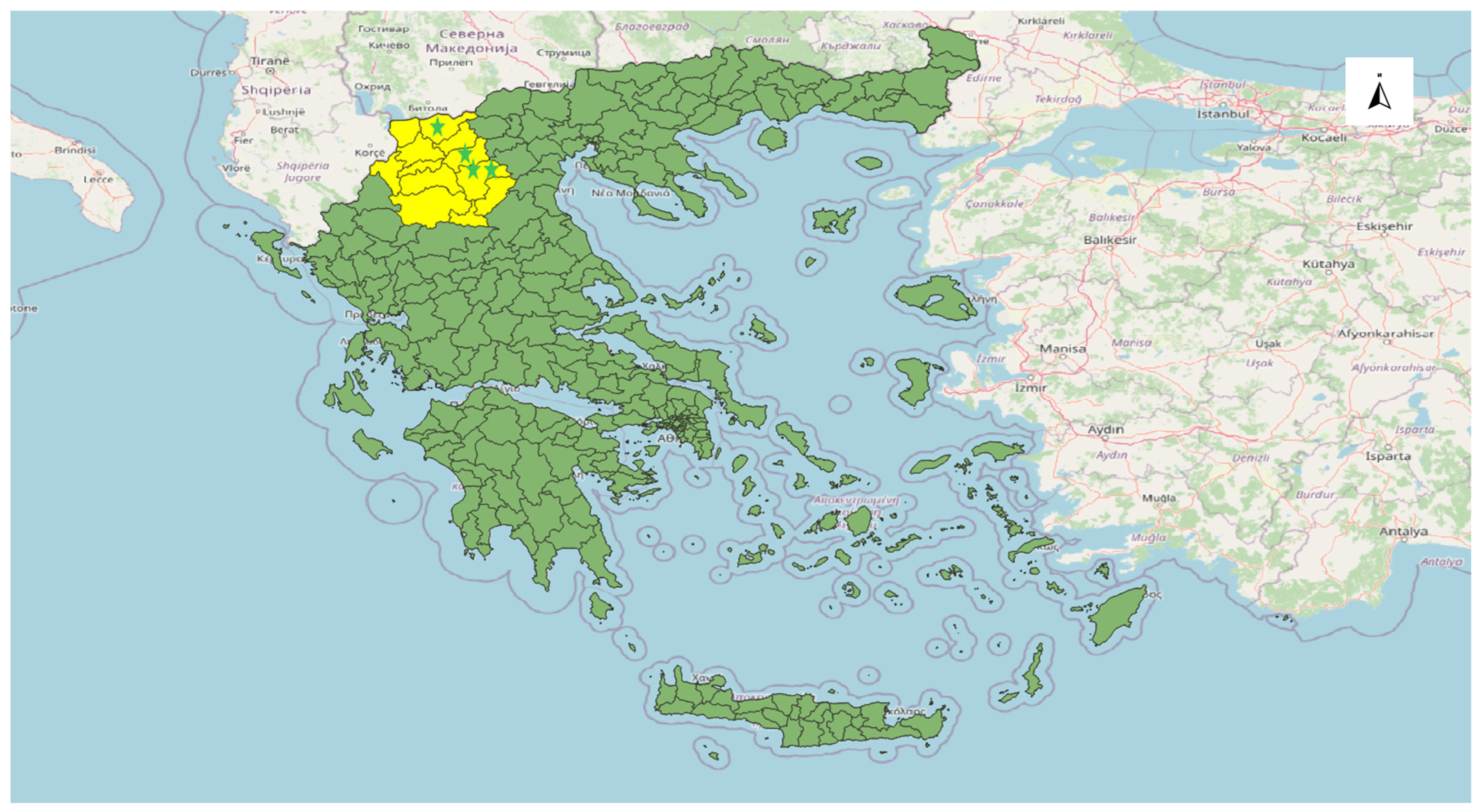

This study analyzed ambient air quality and cardiovascular hospital admissions in four subregions of Western Macedonia, Greece: Florina, Kozani, Ptolemaida, and Grevena. These areas include the locations of major lignite-fired power plants (in Florina, Kozani, and Ptolemaida), as well as a less industrialized area (Grevena). Daily concentrations of five key air pollutants—particulate matter with diameter ≤10 µm PM10, SO2, NO, NO2, and NOx—were obtained from the regional Air Quality Monitoring Network operated by the University of Western Macedonia (UoWM), specifically by the AirLab—Laboratory of Atmospheric Pollution and Environmental Physics.

The network consists of seven fixed monitoring stations distributed across the study region: two stations in Florina (urban background and industrial), two in Kozani (urban background and residential), two in Ptolemaida (industrial and suburban), and one in Grevena (rural background). All stations operate continuously and provide 24 h measurements of PM

10, SO

2, NO, NO

2, and NO

x. These daily concentrations were subsequently processed into 3-day moving averages to represent short-term exposure patterns relevant to acute cardiovascular outcomes.

Figure 1 presents the lignite-fired power plants of the Public Power Corporation (PPC) that were active during the study period and constituted the main sources of air pollution in the region. The monitoring stations of the AirLab network are situated in proximity to these facilities, allowing effective characterization of pollution levels associated with lignite combustion.

Data spanned the years 2011 through 2021, focusing on the winter months of November and December (when pollution levels and cardiorespiratory stress are typically highest). Daily counts of cardiovascular-related hospital admissions were collected from the cardiology departments of the participating hospitals and included cases classified under the relevant ICD-10 codes, specifically acute coronary syndromes (I20–I24), heart failure (I50), cardiac arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation and other rhythm disorders (I47–I49), hypertensive heart disease (I11), and pulmonary heart disease and related disorders (I26–I28). These admissions were aggregated by day and matched to pollutant measurements for the corresponding region. All data were de-identified and analyzed in aggregate; thus, no individual patient information was used, and ethical approval was not required for anonymized aggregate data.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

We employed non-parametric statistical tests given the observational nature of the data and to avoid assumptions of normality [

15,

16,

17]. First, we assessed the association between air pollution and hospital admissions in each area using Spearman’s rank correlation [

15]. For each region, Spearman’s rho (ρ) was calculated between the daily number of cardiovascular admissions and each pollutant’s 3-day average concentration. For each pollutant, a 3-day moving average (lag 0–2) was calculated to capture short-term exposure and reduce measurement noise, while hospital admissions were analyzed as daily counts. No multi-day aggregation of health outcomes was used. This non-parametric correlation was chosen due to the skewed distribution of pollutant levels and admissions counts, and it captures monotonic relationships without assuming linearity [

18]. The significance level was set at

p < 0.05 (two-tailed) for all tests. We interpret a statistically significant Spearman ρ as evidence of an association between higher (or lower) pollutant concentrations and changes in hospital admission counts.

To compare differences across regions, we used Friedman’s two-way analysis of variance by ranks—a non-parametric repeated-measures ANOVA [

16]—treating each calendar day as a repeated block. This allowed us to test whether the distribution of daily admissions differed between the four locations (Florina, Grevena, Kozani, Ptolemaida) when controlling for day-to-day variations (e.g., regional weather or seasonal effects common to all sites). Similarly, we applied Friedman tests to compare pollutant concentration levels between multiple sites [

19]. For example, we compared the daily PM

10 3-day average values among Kozani, Ptolemaida, and Florina (concurrent measurements) to determine if one location consistently exhibited higher or lower pollution than the others. In each Friedman ANOVA, a Chi-square test statistic (based on ranks) and

p-value were obtained for overall differences. When a Friedman test indicated a significant difference (

p < 0.05), we performed post hoc pairwise comparisons between groups (regions) using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests with Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparisons [

19,

20,

21]. Only those pairwise differences with adjusted

p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. We also tested underlying assumptions: the use of Friedman’s test assumes the observations (days) are matched across groups and comes in place of a parametric repeated-measures ANOVA since normality and homoscedasticity could not be assured for these data. Spearman correlation assumes a monotonic relationship; we verified there were no gross nonlinear trends that would contraindicate its use [

17,

22].

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28) and cross-checked in R for consistency. Results are reported with their test statistics (Spearman’s ρ or Friedman χ2) and p-values. In tables, values are given as means ± standard deviation (SD) or as otherwise indicated. An α level of 0.05 was used for significance testing, and all hypothesis tests were two-sided. Non-significant findings (p ≥ 0.05) were interpreted as no evidence of a statistically significant effect rather than proof of no effect, and these are reported to provide a transparent view of the data. All significant correlations and differences are reported with the corresponding p-values, and any observed trends that did not reach significance are also noted in the interest of completeness.

3. Results

3.1. Air Pollution Levels (2011–2021)

Over the 2011–2021 period, ambient pollutant concentrations in Western Macedonia showed marked declines, especially for PM

10 and SO

2, reflecting improved air quality over time.

Table 1 summarizes the mean concentrations (with ranges) of each pollutant in 2011 versus 2021 for the major monitoring locations. In 2011, areas downwind of lignite power stations recorded very high PM

10 levels—for example, Florina’s mean PM

10 in Nov–Dec 2011 was about 75 μg/m

3 (range 61–96 μg/m

3), one of the highest in the region. By 2021, the mean PM

10 in Florina had dropped to ~30 μg/m

3 (range 9–57 μg/m

3), indicating a substantial improvement in particulate pollution. A similar downward trend was observed in the Ptolemaida area, where mean PM

10 fell from ~53 μg/m

3 in 2011 to ~11 μg/m

3 in 2021. Notably, daily PM

10 concentrations in 2011 often spiked well above 100 μg/m

3 in the most affected locations (maximum values ~140–160 μg/m

3 were recorded), whereas by 2021 the peaks were much lower (generally <40 μg/m

3). This drastic reduction in particulate pollution coincides with the de-escalation of lignite activities and implementation of emission control measures in the interim years.

SO2 levels plummeted across all stations, consistent with reduced coal combustion. Florina’s mean SO2 in late 2011 was ~13.9 μg/m3, but by 2021 it had become almost undetectable (mean ~0.5 μg/m3). Ptolemaida likewise saw SO2 drop from ~2.4 μg/m3 to ~1.1 μg/m3 over the period. These reductions in SO2 (often >90% decrease in mean concentration) are evidence of cleaner fuel use or desulfurization efforts. The NOx (NO + NO2) pollutants exhibited more moderate changes. NO2 tended to decrease over the decade at all sites, though not as uniformly as SO2. In Florina, for instance, mean NO2 declined from ~30.8 μg/m3 in 2011 to ~18.3 μg/m3 in 2021. Kozani (city/valley station) had much lower NO2 to start with (mean ~13.7 μg/m3 in 2011) and dropped to ~4.2 μg/m3 in 2021. NO (nitric oxide) levels were generally low throughout (<10 μg/m3 on average) and showed variable year-to-year fluctuations, but most sites still saw a slight downward trend by 2021 (e.g., Kozani NO mean 3.4 → 1.3 μg/m3, Florina 8.1 → 5.2 μg/m3). Total NOx mirrored the NO2 patterns, with Florina registering the highest NOx and Kozani the lowest.

Despite overall improvements over time, there were persistent spatial differences in pollutant concentrations. The lignite-influenced areas (Florina and Ptolemaida) generally experienced higher pollution than Kozani or Grevena. For instance, Florina’s NO

2 and NO

x levels were significantly higher than those in Kozani throughout the study (median NO

2: Florina > Kozani,

p < 0.001), as shown in

Table 1 and confirmed by the post hoc Wilcoxon comparisons following the Friedman test. Likewise, Kozani consistently exhibited the lowest PM

10 and NO

x concentrations among the three lignite-affected areas; for example, Kozani’s median PM

10 was significantly lower than that of Florina and Ptolemaida (

p < 0.001), a result also supported by the post hoc analyses. Interestingly, SO

2 showed a different pattern: Florina (near the now-decommissioned Amyntaio plant) had higher SO

2 than Kozani, but Ptolemaida also recorded elevated SO

2 at times. A Friedman test confirmed a statistically significant effect of location on pollutant levels for each pollutant (

p < 0.001 for PM

10, SO

2, NO, NO

2, and NO

x), driven by these spatial contrasts. Pairwise Wilcoxon comparisons with Bonferroni correction further indicated that Florina had significantly higher NO, NO

2, and NO

x levels than Kozani (all

p < 0.001), while Kozani’s PM

10 concentrations were significantly lower than those of both Ptolemaida and Florina (

p < 0.001). In summary, air quality was poorest in the immediate vicinity of the lignite centers (particularly Florina/Amyntaio and Ptolemaida) and relatively better in Kozani city and rural Grevena, although all areas showed substantial improvements by 2021.

3.2. Hospital Admissions: Regional Patterns

The period of 2011–2021 was selected because it represents the longest continuous timespan with complete and comparable air quality records from the regional monitoring network, and coincides with the decade of progressive lignite phase-out in Western Macedonia. The analysis focuses on the winter months of November–December, which consistently exhibit both the highest pollutant concentrations and the greatest seasonal burden of cardiovascular admissions in the region. A total of 305 daily observations (61 days × 5 years) were analyzed for regional differences in hospitalizations. In the baseline winter of 2011, the busiest hospitals were those in Ptolemaida and Kozani, whereas Grevena’s hospital (serving a smaller, less polluted community) saw far fewer cases. For example, during the November–December period in 2011, the cardiology admissions totaled 171 in Ptolemaida and 146 in Kozani, compared to 57 in Grevena (Florina had intermediate values, on the order of 100 admissions). A non-parametric Friedman test confirmed that regional differences in daily admission counts were highly significant (χ

2 ≈ 388,

p < 0.001 for overall difference across the four areas). Post hoc comparisons showed a clear hierarchy: Grevena consistently had the lowest number of cardiac admissions (significantly lower than all other regions,

p < 0.001), and Ptolemaida had the highest. Florina’s hospital had more admissions than Grevena (

p < 0.001) but significantly fewer than Kozani and Ptolemaida in the early 2010s (

p < 0.001). Kozani and Ptolemaida, the two most populous/central areas, did not differ significantly in 2011–2014 (their admission counts were comparable). These regional differences in 2011 hospitalizations are summarized in

Table 2.

By 2021, total cardiac admissions had decreased in all regions, reflecting either improvements in public health or broader healthcare trends. In Nov–Dec 2021, Ptolemaida recorded 132 cardiology admissions, down ~23% from 2011, and Kozani had 98 admissions, down ~33%. Florina and Grevena also saw declines (Florina’s admissions in 2021 were low enough to be statistically on par with Grevena’s). The Friedman analysis for 2021 still found an overall regional difference (p < 0.001), driven mainly by Ptolemaida’s hospital having significantly more admissions than the others. Ptolemaida remained the outlier with the highest caseload (significantly higher than Florina, Kozani, and Grevena; p < 0.01 for all pairwise comparisons). However, Florina, Kozani, and Grevena had converged in 2021 to similar (and lower) hospitalization levels—differences between those three were minor and not statistically significant after correction. This convergence suggests that the gap between the high-admission and low-admission areas narrowed over the decade, except for Ptolemaida, which still experiences a heavier burden of cases.

Overall, the regional hospitalization patterns indicate that communities closer to the lignite power plants (Ptolemaida, Kozani, and to a lesser extent Florina) have historically borne a greater cardiovascular hospital load than the more distant Grevena—a pattern that was pronounced in the early 2010s. Improvements by 2021 reduced admissions everywhere and made the inter-regional differences less extreme, though Ptolemaida continues to have the highest observed rates of cardiovascular hospitalizations in the region.

3.3. Pollution–Health Statistical Associations

We next examined whether day-to-day fluctuations in pollution were associated with corresponding changes in cardiovascular hospital admissions. Spearman correlation analyses were performed for each area, correlating same-day hospital admission counts with a 3-day moving average of pollutant concentrations (lag 0–2), which represents short-term exposure without aggregating hospital admissions across days. The correlation outcomes are summarized in

Table 3. Notably, the majority of pollutant–admission correlations were weak and not statistically significant, indicating that short-term variations in single pollutants did not correspond to large immediate changes in hospitalizations in most cases. However, a few significant associations emerged:

In Kozani, daily NO2 levels showed a positive correlation with cardiology admissions (ρ = +0.115, p = 0.045), which was statistically significant despite its small magnitude. Days with higher NO2 in Kozani were associated with slightly higher numbers of admissions. Other pollutants in Kozani (PM10, SO2, NO, NOx) had ρ values near zero and p > 0.05, indicating no significant correlation.

In Ptolemaida, a significant correlation was found for SO2 and admissions (ρ = +0.122, p = 0.034). This suggests that spikes in sulfur dioxide—likely a marker of local emissions—corresponded to modest increases in hospital admissions in Ptolemaida. PM10 showed a positive but borderline correlation (ρ = +0.112, p = 0.052, not significant), and NO, NO2, NOx in Ptolemaida all had very low, non-significant correlations (ρ ≈ 0.0–0.03, p > 0.5).

In Florina, PM10 was the only pollutant significantly correlated with admissions (ρ = +0.138, p = 0.017). Thus, on days with higher particulate levels in Florina, the hospital saw slightly more cardiac admissions on average. In contrast, Florina’s gaseous pollutants (SO2, NO, NO2, NOx) all showed weak negative correlations with admissions (ρ between –0.015 and –0.069) that were not statistically significant (p = 0.24–0.79). Essentially, no clear relationship was detected for those gases in Florina.

In Grevena, which had much lower pollution levels, none of the pollutant metrics were significantly associated with admissions. (Grevena’s air quality data were limited; additionally, the hospital admission counts there were quite low and showed little day-to-day variation, making correlations less reliable. Indeed, no meaningful pollutant–health correlation could be established for Grevena.)

Despite some statistically significant correlations, it is important to note that all correlation coefficients were relatively small in magnitude (|ρ| ≈ 0.1–0.14 for the significant cases). This suggests that acute changes in single-pollutant levels explained only a small fraction of the day-to-day variability in cardiovascular admissions. For example, the strongest association observed—PM10 in Florina—had ρ ≈ 0.14, indicating a very mild positive relationship. Such weak correlations imply that short-term pollutant fluctuations alone were not a dominant driver of daily cardiac hospital admissions in this dataset. It is possible that the health outcome is influenced by multi-day or cumulative exposure patterns that extend beyond a 3-day average; alternatively, the weak associations may partly reflect limitations of the statistical approach used (i.e., simple pairwise Spearman correlations), which cannot capture more complex exposure–response dynamics. Additionally, socio-environmental factors such as ambient air temperature, population susceptibility, and healthcare access likely contribute to day-to-day admission counts, diluting the measurable impact of air pollution on an individual day.

Τhe results reveal that higher particulate matter and certain gas concentrations corresponded to slight increases in hospital admissions in specific locales, consistent with the known adverse cardiovascular effects of pollution, but these effects were modest on a daily timescale. The associations were area-specific: PM10 was a significant predictor of daily cardiovascular hospital admissions in Florina, SO2 in Ptolemaida, and NO2 in Kozani, while other pollutant–region combinations showed no significant link. This pattern may reflect differences in population exposure or pollutant mix: for instance, Florina’s population might be more affected by particulate spikes (perhaps due to wood/coal heating contributions to PM10), whereas in Ptolemaida SO2 (a marker of power-plant emissions) showed the strongest signal. The lack of a broader significant correlation across all pollutants and areas underscores that acute cardiovascular admissions are likely influenced by a complex interplay of factors, and pollution’s impact, while detectable, is relatively subtle when considering daily fluctuations. Nevertheless, the significant positive correlations that were detected (though small in effect size) align with the epidemiological understanding that even short-term increases in ambient PM and SO2/NO2 can trigger or exacerbate cardiovascular events. These findings reinforce the importance of maintaining lower air pollution levels to protect cardiovascular health, especially in regions like Western Macedonia with vulnerable populations and historically high pollution.

4. Discussion

The present findings reinforce and extend the extensive body of evidence linking ambient air pollution to adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Globally, environmental pollution—including ambient air pollution, chemical pollution, and other exposure pathways—remains a major contributor to cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity and mortality. The landmark Lancet Commission on pollution and health reported that environmental pollution was responsible for approximately 9 million premature deaths in 2015 (around one in six deaths worldwide) [

1,

2]. Importantly, a large proportion of these pollution-related deaths are cardiovascular—on the order of 60% or more in recent analyses [

23]. There appears to be no “safe” threshold below which air pollution poses no cardiovascular risk; even low concentrations have been associated with measurable increases in CVD events [

24]. Our study of Western Macedonia—a region historically burdened by elevated particulate and gaseous emissions from lignite coal combustion—aligns with this global literature. We found that reductions in ambient PM

10 and SO

2 over the 2011–2021 period coincided with a decline in cardiovascular hospital admissions, while day-to-day increases in certain pollutants were associated with modest upticks in cardiac hospitalizations. In this discussion, we interpret these findings in the context of international epidemiologic and mechanistic evidence, compare them with prior studies in Europe and beyond, and consider potential implications and limitations.

4.1. Air Quality Improvements and Cardiovascular Trends

One notable finding of our study is the concurrent improvement in air quality and decline in cardiovascular hospital admissions over the decade. Mean winter PM

10 and SO

2 levels fell dramatically in the lignite-burning areas (e.g., Florina and Ptolemaida) between 2011 and 2021, and during the same interval the total cardiology admission counts in these areas dropped by approximately 20–30%. This temporal association is consistent with observations from other regions that lowering air pollution yields measurable public health benefits in relatively short time frames. For example, the American Heart Association (AHA) scientific statement update noted that reductions in fine particulate matter have been associated with decreases in cardiovascular mortality within just a few years [

25]. In the United States, a 0.61-year increase in life expectancy was observed per 10 µg/m

3 decrease in PM

2.5 concentration across cities, after accounting for socioeconomic factors [

26]. Similarly, the ban on coal sales in Dublin, Ireland led to a 70% reduction in particulate pollution and was followed by a 10% decrease in cardiovascular death rates (an estimated 243 fewer cardiac deaths per year) [

27]. Our findings in Western Macedonia likely reflect a comparable phenomenon: as pollution from lignite power plants abated (due to decommissioning of older units and emissions controls), the burden of acute cardiac events in the population also declined. It is worth noting that broader healthcare system trends and primary prevention improvements may have also contributed to declining admissions (for example, improved hypertension and lipid management over the decade), acting in parallel with the substantial reductions in air pollution. Therefore, the observed decrease in hospitalizations likely reflects multiple contributing factors rather than air quality alone. However, the temporal and spatial pattern—with the steepest admission declines observed in the traditionally most-polluted locations—is suggestive of an air pollution effect. This convergence of hospital admission rates between higher-pollution and lower-pollution areas by 2021 underscores the public health importance of environmental improvements in historically polluted regions.

4.2. Short-Term Pollution Exposure and Acute Cardiovascular Events

Despite the overall improvement, our analysis detected significant short-term associations between pollution levels and daily cardiovascular admissions in specific subregions. These acute effects were modest in magnitude, yet they are in agreement with numerous epidemiological studies indicating that day-to-day fluctuations in air pollution can trigger acute cardiac events such as myocardial infarction, heart failure decompensation, or arrhythmias [

28,

29]. In Florina, days with higher PM

10 were associated with slightly increased cardiac admissions, whereas in Ptolemaida, elevated SO

2 on a given day corresponded to a higher admission count. In Kozani, daily NO

2 concentrations showed a minor but statistically significant positive association with daily cardiovascular hospital admissions. Although most pollutant–hospitalization correlations in our data were weak (Spearman ρ ≈ 0.10–0.12), this simply indicates that same-day pollutant fluctuations explain only a small proportion of the day-to-day variability in cardiovascular admissions. Such small correlations are common when using single-day exposure metrics to assess short-term health effects. For instance, a multi-city U.S. study found that a 10 μg/m

3 increase in daily PM

2.5 was associated with a ~1.3% increase in heart-failure hospitalizations [

28,

30], and an Italian nationwide analysis reported a 0.5–1.0% increase in total cardiovascular admissions per 10 μg/m

3 of PM

10 (and about a 1.7% increase in heart-failure admissions) [

31,

32]. Given the low day-to-day variability in cardiovascular admissions and the use of same-day exposure metrics, relatively weak pollutant–admission correlations are expected. Similar correlation magnitudes (typically ρ < 0.15) have been reported in short-term studies using comparable methods, particularly in regions with modest pollution variability. Therefore, the small but statistically significant associations observed here are consistent with the pattern found in comparable correlation-based analyses. They confirm that even in a medium-sized population, acute pollution exposure can noticeably affect cardiovascular event rates, albeit with effects that may require large sample sizes or multi-year data to detect statistically [

33].

Importantly, our findings were pollutant-specific and location-specific, suggesting heterogeneity in exposure–response depending on local environmental and population factors. In Florina, PM

10 showed a statistically significant positive association with daily cardiovascular admissions, whereas no significant association was observed for PM

10 in Kozani or Ptolemaida. Florina is downwind of a major power plant and also experiences winter biomass burning for heating; this mix of sources might produce higher spikes in particulates, to which the local population is acutely responsive. By contrast, SO

2 was a significant correlate in Ptolemaida, the site of multiple active lignite units during the study period—here, short-term peaks in SO

2 (a marker of coal combustion) showed an correlation with admissions, whereas SO

2 in Florina (which had declining emissions after a power station closure) did not. These patterns resonate with studies from other coal-burning regions and industrial centers. In Beijing, China, for example, time-series analyses have demonstrated that daily SO

2 levels correlate with increases in cardiovascular hospital admissions, especially for ischemic heart disease and hypertension-related events, in populations exposed to coal-fired heating [

34]. Our observation that NO

2 had an effect in Kozani (the most urbanized area, with traffic and urban background pollution) is consistent with research in high-traffic cities showing nitrogen dioxide to be associated with acute coronary syndromes and arrhythmias, often as an indicator of traffic-related combustion emissions. A comprehensive meta-analysis by Mustafic et al. [

29] indeed found that all major pollutants—PM

2.5, PM

10, NO

2, SO

2, and CO—were significantly associated with a near-term increase in myocardial infarction risk, with only ozone showing no clear effect. Thus, our area-specific results (PM-driven in one locale, SO

2- or NO

2-driven in another) likely reflect differences in dominant sources and population exposure profiles, but in all cases they align with the broader notion that short-term exposure to particulate and gaseous pollutants can acutely trigger cardiovascular events.

From a public health perspective, the short-term pollutant–admission correlations observed in this study were modest in magnitude, indicating that daily fluctuations in air pollution explained only a small proportion of the variability in cardiovascular admissions. This modest effect size is in line with expectations and does not diminish its importance: even a 1–2% increase in daily CVD admissions can translate into a significant number of additional cases when applied to an entire population, and these cases may include life-threatening events (e.g., myocardial infarctions or acute heart failure episodes) that incur substantial individual and societal costs. Moreover, the impact of chronic exposure is cumulative; days of elevated pollution might precipitate events in vulnerable individuals (e.g., the elderly or those with pre-existing heart disease), contributing to the overall burden of cardiovascular morbidity. Our findings reinforce the idea that there is no truly “harmless” level of air pollution. Exposure reductions—even from moderate levels down to low levels—confer cardiovascular benefits, and conversely, short-term pollution spikes can have tangible health impacts [

24]. This evidence base has prompted increasingly stringent air quality guidelines. For instance, the WHO has recently lowered its recommended PM

2.5 and NO

2 limits, citing epidemiological data showing risk persisting at the previous standards [

4]. The Western Macedonia region, despite improvements, still experienced winter PM

10 concentrations (often 30–50 μg/m

3 in 2021) that exceed the latest WHO guideline for PM

2.5 (15 μg/m

3 annual, 25 μg/m

3 24 h) when converted to PM

2.5 equivalent. Our study provides epidemiological support for aggressive pollution mitigation: even in a setting with intermediate pollution levels by earlier standards, further reductions might yield additional reductions in cardiovascular events [

35].

Although the present study did not investigate mechanistic pathways, it is well established in the literature that air pollutants can trigger cardiovascular events through systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and transient endothelial dysfunction [

36,

37]. These biological responses may acutely destabilize susceptible individuals and provide a general framework that contextualizes the small short-term associations observed in our analysis.

A few European epidemiological studies have reported similar modest short-term increases in cardiovascular admissions associated with daily changes in PM

10, PM

2.5, NO

2, or SO

2 concentrations. Our observations are broadly consistent with these findings, aligning with multi-city analyses from Italy, the APHEA project, and related European time-series investigations [

38,

39,

40,

41].

4.3. Study Limitations and Strengths

While interpreting our findings, several limitations of the study should be acknowledged. First, the observational design (daily correlations) cannot prove causation, and unmeasured confounding factors may influence the associations. We did not explicitly adjust for weather variables (e.g., air temperature, relative air humidity) or seasonal epidemics (e.g., influenza) in our analysis; instead, we implicitly controlled for season by focusing on winter months and used non-parametric tests to handle general temporal trends. However, short-term cold snaps or flu outbreaks could increase cardiac admissions and coincidentally correlate with pollution (for example, colder days lead to more fuel combustion and also physiologically stress the cardiovascular system). This residual confounding could either exaggerate or mask pollution’s true effect. Second, our health outcome was total cardiovascular admissions to cardiology departments, which, while pragmatic, is a composite of various conditions—including acute coronary syndromes, heart failure, arrhythmias, etc. Each of these sub-outcomes may have different relationships with pollution. For instance, arrhythmias might be more immediately triggered by pollution (via autonomic effects), whereas heart failure admissions might depend on cumulative exposure or fluid retention related to weather. By aggregating them, we potentially diluted more specific associations. Future analyses focusing on cause-specific admissions (e.g., separating acute myocardial infarctions from heart failure) could provide more nuanced insights. Third, our pollution exposure metrics came from ambient monitoring stations and may not perfectly represent individual exposure, especially for a spatially spread population. Western Macedonia’s topography and settlement patterns mean that some residents (e.g., those near plant stacks or in valley villages) experience different pollution levels than what the central monitors record. Any exposure misclassification of this kind is likely non-differential, tending to bias associations toward zero. This could partly explain why many pollutant–admission correlations were null or very weak—true exposure differences were larger than what was measured, introducing noise. Fourth, the statistical power to detect associations was limited by the moderate sample size (305 days per area) and additionally because the analysis used conservative statistical thresholds (

p < 0.05 without multiple-comparison adjustment across five pollutants and four areas in

Table 3). It is possible that some true associations were missed (Type II error), or that some nominally significant ones may be false positives (though their consistency with literature makes this less likely). We attempted to mitigate multiple comparisons by focusing our interpretation on patterns consistent with prior knowledge (e.g., we place more confidence in the PM

10, NO

2, SO

2 findings than we would in an isolated unexpected finding). Fifth, by focusing only on winter months across years, we targeted the season of highest pollution and presumed susceptibility; however, this means our results may not generalize to other seasons. Summer pollution (e.g., ozone, which we did not measure) could also impact cardiovascular health—a domain our study did not address. Additionally, long-term trends in population demographics and health behaviors (e.g., aging, smoking rates) were not explicitly modeled; some of the decline in admissions might reflect such factors as well, rather than environmental change alone. Finally, an extraordinary factor in the later part of our study period was the COVID-19 pandemic (late 2020 and 2021), which is known to have reduced hospital admissions for other causes due to patients avoiding hospitals and healthcare system strain. We included data up to December 2021; thus, part of the observed decline in admissions by 2021 (especially in Kozani and Florina) could be due to pandemic-related healthcare disruptions rather than improvements in underlying cardiovascular health. Unfortunately, our data cannot easily disentangle this; we note, however, that pollution levels were also lower in 2020–2021 (due in part to lockdown-related emission reductions), so the pandemic likely influenced both pollution and admissions. Recognizing these limitations, our analysis should be viewed as an ecological, hypothesis-generating study that is consistent with (but not absolute proof of) pollution-related cardiac effects.

Despite these limitations, the study also has several strengths. It leverages 10 years of data across multiple communities with different pollution profiles, enhancing variability in exposure and allowing an internal comparison between more-polluted versus less-polluted areas. The use of non-parametric statistical methods (Spearman rank correlations, Friedman tests) made our findings robust against outliers and without assumptions of linearity or normality, which is appropriate given the skewed distribution of pollutant concentrations. We focused on a unique setting (lignite-dependent region) that has been underrepresented in health impact literature; thus, our results contribute novel information for a type of high-exposure environment analogous to other coal-burning regions in Eastern Europe or Asia. By examining multiple pollutants simultaneously, we could identify which pollutant had the strongest association in each area, providing clues about dominant harmful agents (e.g., suggesting that controlling particulate matter might yield most benefit in Florina, whereas SO2 reduction is key in Ptolemaida). Lastly, the declining secular trends we observed add credibility to a pollution effect: it is encouraging (and biologically plausible) to see cardiovascular admission rates improve over years in parallel with air quality gains. This coherence with expected directionality strengthens the argument that the associations are not spurious.

5. Conclusions

In this lignite-dependent region of Western Macedonia, a decade of air quality improvements coincided with a clear decline in cardiovascular hospital admissions. Short-term increases in PM10, SO2, and NO2 were correlated with modest increases in daily cardiac admissions, consistent with international evidence linking pollution to acute cardiovascular events. These findings underscore that continued emission reductions and air quality management remain important components of cardiovascular disease prevention in former coal-based areas.

Beyond the immediate findings, our results hold implications for public health practice. Localized air quality monitoring and early warning systems can help protect vulnerable individuals during high-pollution days, while the ongoing transition away from lignite is likely to generate further health benefits. Cardiovascular endpoints should also be explicitly incorporated into environmental and energy policy impact assessments, as they respond sensitively to changes in pollutant exposure.

Future research should employ more advanced time-series or case-crossover methods that account for meteorological and seasonal confounders, quantify lag structures, and explore dose–response relationships. Analyses tailored to specific cardiovascular outcomes (e.g., myocardial infarction versus heart failure) would help identify the most pollution-sensitive endpoints. Additionally, prospective studies examining physiological markers—such as blood pressure, inflammatory indicators, and arrhythmic activity—could clarify the biological pathways relevant to this population. Finally, as Western Macedonia completes the lignite phase-out, this setting presents a unique natural experiment to assess how large-scale emission reductions translate into measurable cardiovascular health gains.