Abstract

Conventional wind resource assessments often fail to capture the complex interaction between topography and technology suitability in mountainous regions. This study employs a 40-year, 5 km resolution WRF dataset to construct a differentiated assessment framework for Sichuan Province, distinguishing between utility-scale and distributed generation potentials. The results reveal that topography dictates a stark west-to-east resource gradient, with the Extreme Wind (EW) region possessing a wind power density (1166 W/m2) exceeding that of the sheltered Basin by over 24 times. However, this high potential is coupled with severe operational risks, as overspeed shutdown durations (>25 m/s) in the EW region exceed those in the High Wind Plateau by more than 4.45 times. Crucially, shifting to a distributed generation perspective (2–15 m/s) fundamentally reconstructs the resource landscape: the Basin gains a substantial “light breeze dividend” with available hours increasing by ~89%, whereas the EW region suffers a “high-speed penalty” of ~7% due to frequent cut-out events. Despite a systematic model bias attributed to the “representativeness mismatch” between ridge-resolving grids and valley-bottom observations, the revealed relative spatiotemporal patterns remain robust.

1. Introduction

Under the global consensus on carbon neutrality, building a new power system dominated by renewable energy is central to ensuring energy security and climate resilience. Europe and the United States are accelerating the reshaping of their electricity structures with wind power, but this transition is accompanied by new challenges posed by climate change: following droughts that threaten hydropower, “wind droughts” (persistent low-wind events) are emerging as a major risk to wind-dominant power grids [,,,]. To meet this challenge, China’s wind power development strategy is undergoing a profound shift, moving from the high-wind “Three-North” regions to the load centres in central, eastern, and southern China [,]. The success of this strategic transition depends not only on enhancing the efficiency of large-scale turbines but also on distributed, low-wind-speed generation technologies that redefine wind energy value, thereby unlocking the vast potential of traditionally “wind-poor” areas [,,]. Southwest China, with its complex topography and co-location of hydro and wind resources, thus becomes a focal point for addressing this transition [,].

Accurate wind resource assessment is a scientific prerequisite for the successful development of wind power projects. Early assessments, relying on sparse meteorological stations or short-term met masts and statistical extrapolation methods like measure-correlate-predict (MCP), have inherent limitations in spatiotemporal representativeness and struggle to capture long-term climate variability and fine-scale wind field details in complex terrain [,,]. With advancements in computational power, reanalysis datasets from numerical weather prediction (NWP) models have become a cornerstone for global and regional wind energy assessment. Global reanalyses, such as the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts’ ERA5 [], the US CFSR [,], NASA’s MERRA-2 [], Japan’s JRA-55 [], and China’s CRA-40 [], provide multi-decadal, spatiotemporally continuous meteorological fields that have laid the foundation for understanding large-scale wind climatology. However, their common limitation is a coarse spatial resolution (typically > 25 km), making them unable to resolve key local circulations driven by drastic elevation changes, mountain barriers, and deep valleys, which leads to biases in simulating near-surface wind speeds in complex terrain [,,]. To bridge this scale gap, dynamical downscaling techniques, particularly the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model, have become a mainstream tool for long-term wind resource assessment in complex terrain [,,], while higher-fidelity computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models are typically reserved for micro-siting due to prohibitive computational costs [,].

Against this backdrop of national strategic transition, Sichuan Province, a major clean energy base, saw the vulnerability of its 76% hydropower-dominated structure exposed during the historic 2022 drought [,,], making “hydro-wind complementarity” imperative for energy security [,]. However, Sichuan’s wind resources exhibit an extreme “west-strong, east-weak” dichotomy, necessitating differentiated, region-specific development pathways. The western Panzhihua Plateau, with its superior wind resources, is designated for national-level, large-scale wind power bases to complement hydropower, but faces challenges in assessing operational risks in its complex terrain [,,]. Meanwhile, the vast eastern basin, the province’s load centre, with its low wind speeds, may be an ideal setting for distributed low-wind-speed generation [,]. Concurrently, a long-term “stilling” trend across the entire province introduces uncertainty for both technological pathways [,,].

Current assessment frameworks primarily focus on maximizing gross resource magnitude, often overlooking the critical nonlinear interactions between specific technological thresholds (e.g., cut-out speeds) and local topographical constraints. Consequently, Sichuan’s wind power development faces a critical dilemma: the most extreme wind resource areas are often constrained by prohibitive operational risks, while traditionally ‘wind-poor’ regions are prematurely dismissed despite their potential for distributed generation. To address this methodological gap, this study uses a 40-year, 5 km resolution WRF simulation to construct a differentiated assessment framework. We systematically reveal how topography leads to counter-intuitive resource-risk trade-offs in assessing centralized versus distributed generation potential. This provides a critical scientific basis for building a synergistic, secure, and economical “hydro-wind-solar” power system that integrates western “large bases” with eastern “distributed” generation.

2. Data and Methodology

2.1. Study Area

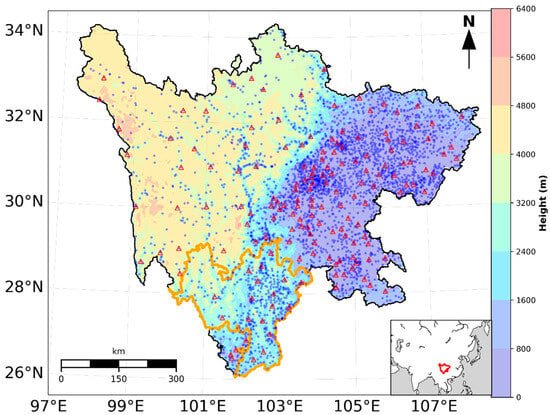

This study focuses on Sichuan Province (97°21′–108°33′ E, 26°03′–34°19′ N), located in southwestern inland China. The region features exceptionally complex terrain and topography, serving as an ideal natural laboratory for investigating wind field characteristics over heterogeneous surfaces. The terrain descends dramatically in a stepped configuration from west to east: the western region comprises the eastern edge of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau with average elevations exceeding 4000 m, including the Hengduan Mountains and associated high-altitude valleys; the central zone consists of peri-basin mountains and hills at elevations of 1000–3000 m; the eastern area encompasses the low-lying Sichuan Basin with elevations below 750 m (Figure 1). This extreme elevation gradient (exceeding 7000 m) and diverse geomorphological units drive multiscale local circulation systems—ranging from plateau monsoons to basin calm winds, and from mountain-valley winds to downslope flows—resulting in pronounced spatial heterogeneity in near-surface wind energy resources.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of automatic weather stations and terrain elevation in the Sichuan Basin-Plateau region. The map displays 6800 automatic weather station locations (colored dots) overlaid on topographic elevation (background shading, color scale in meters). Map approval number: GS(2019)3333.

2.2. Data Sources

To achieve long-term, high-precision assessment of wind energy resources in Sichuan Province, this study integrates multiple data sources.

Reanalysis data. The core driving dataset comprises ERA5 global atmospheric reanalysis produced by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). We utilized 40 years of hourly data from 1979 to 2018 at 0.25° spatial resolution, providing stable and reliable large-scale background fields and lateral boundary conditions for the model.

Observational data. First, to evaluate long-term climatological trends in wind speed, we compiled daily observational data from approximately 167 national meteorological reference stations across Sichuan Province since 1979. Second, to validate model capability in reproducing fine-scale wind field structures over complex terrain, we employed hourly wind speed observations from Sichuan Province’s high-density automatic weather station (AWS) network during 2016–2018. This network comprises over 6800 stations, providing critical validation for 5 km resolution simulations. All observational data underwent rigorous quality control prior to use.

2.3. High-Resolution Wind Field Dynamical Downscaling

This study employs the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model (ARW core, version 4.1.3) for dynamical downscaling simulations spanning 1979–2018. The simulation domain (1200 × 950 grid points, centered at 105° E, 35° N) adopts a two-way nested configuration: the outer domain covers most of East Asia, while the inner domain (d01) precisely encompasses Sichuan Province and surrounding areas at 5 km resolution. The model implements 50 vertically stretched eta levels with enhanced resolution (exceeding eight levels) within 1 km of the surface to improve simulation accuracy of wind speed vertical profiles within the planetary boundary layer.

Physical parameterization schemes include the Yonsei University (YSU) planetary boundary layer scheme, Thompson microphysics scheme, RRTMG longwave and shortwave radiation schemes, and Noah-unified land surface model. Additional options include topographic wind effects, deep soil temperature, and lake model parameterizations. Model topographic elevation and land use data derive from GTOPO30S and MODIS IGBP 21-category datasets, respectively.

2.4. Hub-Height Wind Speed Extrapolation and Wind Power Density Calculation

To assess wind energy potential at commercial turbine hub heights, this study employs the wind profile power law to extrapolate model-output 10 m wind speeds to 100 m. This method represents the classical approach for describing vertical wind speed variation within the atmospheric boundary layer:

where v1 and v2 denote wind speeds at reference height h1 (10 m) and target height h2 (100 m), respectively, and α represents the dimensionless wind shear exponent.

The wind shear exponent (α) depends on surface roughness and atmospheric stability. Considering Sichuan Province’s complex terrain, we adopt spatially varying α values based on land use/land cover (LULC) classification. Specifically, basin and plain agricultural regions employ values of 0.16–0.20; other regions follow empirically established values from previous studies [,]: open water 0.10–0.13, flat open terrain 0.14–0.16, forested areas 0.22–0.28, and urban centers 0.30–0.40.

Upon obtaining hourly 100 m wind speeds, we calculate wind power density (WPD) using WPD = 1/2·ρ·v3, where air density ρ adopts the standard value of 1.225 kg/m3. Annual mean WPD is computed by averaging all 8760 hourly values.

2.5. Differentiated Wind Energy Assessment Framework and Key Metrics

The core innovation of this study lies in constructing a differentiated wind energy potential and risk assessment framework based on validated WRF simulation datasets.

- Differentiated technology application scenarios. To bridge the gap between macro-scale (utility-scale) and micro-scale (distributed) generation potential assessments, this study designs two technology application scenarios:

- Utility-scale centralized development scenario: Assesses potential for large turbines suitable for “mega-base” development, with operational wind speed window set at 3 m/s (cut-in) to 25 m/s (cut-out).

- Distributed micro-wind generation scenario: Evaluates distributed wind power technology potential, with operational wind speed window set at 2 m/s to 15 m/s.

- Key assessment metric definitions:

- Annual available hours: Total annual hours suitable for electricity generation within the aforementioned operational windows.

- Calm wind risk (wind drought risk): Annual cumulative hours with wind speeds below 2 m/s.

- Cut-out risk (high-wind risk): Annual cumulative hours with wind speeds exceeding 25 m/s for large turbines; exceeding 15 m/s for distributed turbines.

- Seasonal and diurnal patterns: Analyzed through monthly mean wind speeds and diurnal wind speed ratios (nighttime 19:00–06:00 versus daytime 07:00–18:00).

- Spatiotemporal analysis methodology. For all aforementioned metrics, we adopt a unified analytical workflow:

- Spatial distribution pattern analysis: Compute 40-year mean values for each grid cell, classify by five geographic zones, and visualize using violin plots to reveal median, mean, dispersion, and spatial homogeneity of resources across zones.

- Long-term evolution trend analysis: Apply nonparametric Mann–Kendall test to determine trend significance for annual time series at each grid cell, and use Sen’s slope estimator to quantify trend magnitude. Violin plots similarly display trend distribution characteristics across zones.

3. Results

3.1. High-Resolution Assessment of Wind Energy Potential for Differentiated Generation Technologies over Sichuan’s Complex Terrain

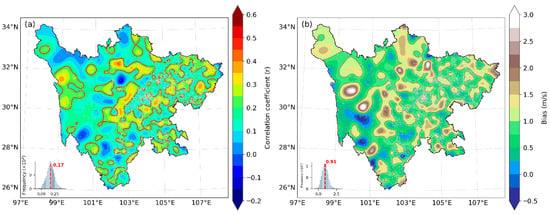

Spatial validation of the WRF wind speed simulation reveals a moderate but spatially heterogeneous positive correlation with observations, with a median Spearman correlation coefficient (r) of 0.17 across all stations (Figure 2a). The correlation is notably weaker over the western and northern Sichuan Plateau, where r-values are typically between −0.1 and 0.15, indicating the model’s difficulty in capturing the complex wind fields in this region. In contrast, the correlation improves over the Sichuan Basin and its northern areas, with r-values exceeding 0.2. The simulation exhibits a systematic overestimation of wind speed, as shown by the mean bias (MB) distribution (Figure 2b). The median MB is +0.91 m/s, a substantial deviation given the low mean wind speeds prevalent within the basin. This overestimation is strongly tied to topography. The most severe biases occur over the western Sichuan Plateau, often exceeding +1.5 m/s and reaching up to +2.5 m/s. This widespread positive bias is fundamentally attributed to the “representativeness mismatch” between the 5 km grid resolution and point-based station measurements in complex terrain. Meteorological stations in the mountainous Sichuan region are predominantly sited in habitable valleys or flat low-lying areas for accessibility and maintenance. Consequently, these observations reflect the wind characteristics of topographically shielded valley bottoms. In contrast, a single 5 × 5 km2 simulation grid cell aggregates the momentum budget of a vast area that encompasses both sheltered valleys and exposed ridge lines. Since wind speeds increase exponentially with elevation and are significantly higher at mountain crests, the grid-averaged wind speed inevitably incorporates these high-momentum components from the peaks. Therefore, comparing a spatially averaged grid value (which includes ridge-top winds) against a valley-bottom observation naturally results in a systematic numerical inflation. Additionally, the smoothed model topography at 5 km resolution inadequately resolves the sub-grid drag effects exerted by steep slopes and deep canyons, leading to insufficient energy dissipation and excessive downward transfer of momentum. In summary, while the WRF reanalysis captures the general spatial patterns, this valley-observation versus ridge-resolving-grid discrepancy leads to a systematic overestimation of near-surface wind speeds.

Figure 2.

Spatial validation of WRF wind speed simulations against observations in the Sichuan Basin-Plateau region. (a) Spearman correlation coefficient between 6800 automatic weather stations observations (2016–2018) and WRF 5 km resolution climatological simulations (1979–2018). The red contour delineates r = 0.2. Inset histogram shows the frequency distribution with median r = 0.17 (red vertical line). (b) Spatial distribution of mean hourly wind speed bias (unit: m/s). The red contour indicates ME = 1.0 m/s. Inset histogram displays bias distribution with median MB = +0.91 m/s (red vertical line). Color scales represent correlation strength ((a): −0.1 to 0.6) and bias magnitude ((b): −0.5 to 3.0 m/s).

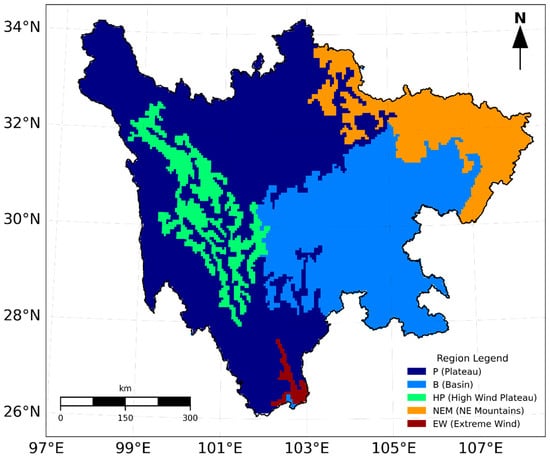

Figure 3 illustrates the wind speed regionalization in Sichuan, derived from 40-year monthly mean wind speed data at a 5 km resolution using an Agglomerative Clustering algorithm (see Appendix A, Figure A1 for partitioning coefficients). The spatial distribution of wind speed in Sichuan Province exhibits multi-scale characteristics driven by its profound topographic heterogeneity. At a macroscale, the western plateau (Region P), influenced by prevailing westerlies, constitutes a high-wind region, whereas the eastern basin (Region B) acts as a topographically shielded ‘low-wind zone’. Superimposed on this pattern, meso-scale mountain ranges induce wind acceleration; the Hengduan Mountains (Region HP) enhance local winds through a pronounced channeling effect, while the Daba Mountains (Region NEM) act as a dynamic barrier, intensifying speeds. Furthermore, micro-scale topographic constrictions at specific passes or gorges form localized ‘extreme wind spots’ (Region EW). Collectively, these multi-scale topographic features shape the highly heterogeneous spatial pattern of wind speed across the region.

Figure 3.

Wind speed regionalization of Sichuan Province based on spatial clustering analysis.

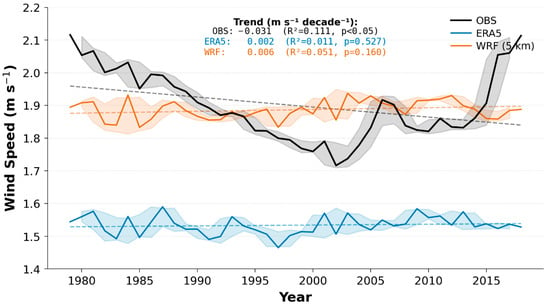

Figure 4 shows a significant divergence between observed and simulated multi-decadal surface wind speed trends is identified for the Sichuan region from 1979–2018. Observational data from 162 stations reveal a non-linear “stilling-to-recovery” pattern, where speeds decreased from ~2.1 m s−1 in 1979 to a minimum of ~1.7 m s−1 in the early 2000s, followed by a distinct recovery. This “stilling” phenomenon is consistent with findings across much of China and the globe, physically attributed to the combined effects of the weakening East Asian Winter Monsoon and the increasing surface roughness induced by rapid urbanization and vegetation growth []. The overall linear trend shows a significant decline of −0.031 m s−1 decade−1 (p < 0.05), though this value should be considered an upper estimate as the unhomogenized data may include non-climatic factors (e.g., station relocation or instrument changes).

Figure 4.

Comparison of observed and simulated multi-decadal wind speed in Sichuan. Annual mean surface wind speed (m s−1) from 1979 to 2018. Data are shown for an observation-based dataset from 167 stations (black line), the ERA5 reanalysis (blue line), and a 5 km WRF simulation forced by ERA5 (orange line). Shaded areas depict the range of one standard deviation (±1σ) for the 3-year running mean wind speed, illustrating the temporal variability. For the observation-based dataset (black line), the standard deviation is calculated from the 167 stations; for ERA5 (blue line) and WRF (orange line), it is calculated from all grid points across the Sichuan region. Dashed lines indicate the linear trends over the entire period.

In stark contrast, neither the ERA5 reanalysis nor the high-resolution WRF simulation reproduced this critical decadal variability. ERA5 consistently underestimated wind speeds by 0.3–0.5 m s−1 and exhibited a near-zero long-term trend (0.002 m s−1 decade−1). Since the WRF simulation is strictly forced by these lateral boundary conditions, it inevitably inherited this lack of trend variability. The WRF simulation, driven by these boundary conditions, consequently inherited this deficiency. This highlights a fundamental limitation of current regional climate modeling in capturing observed long-term wind speed evolution over this complex terrain, underscoring the need for caution when interpreting model-based trend analyses.

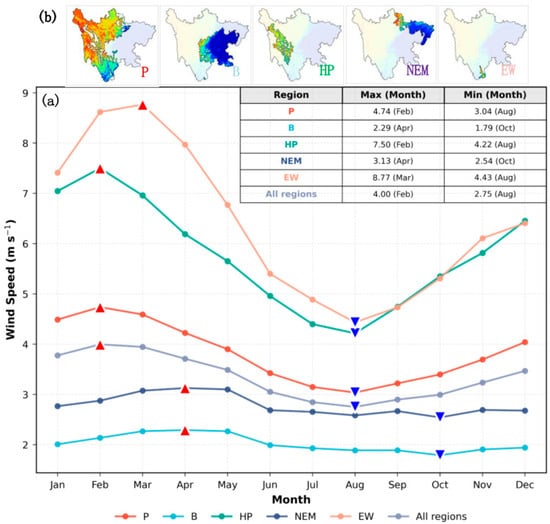

Wind speeds in Sichuan Province exhibit a pronounced single-peak seasonal pattern, forming a “high-wind season” from November to April and a “weak-wind season” from June to September, with May and October serving as transitional months. The provincial average wind speed peaks in February (4.00 m s−1) and reaches its minimum in August (2.75 m s−1) (Figure 5). Regional wind energy potential displays marked differentiation. The Extreme Wind region (EW) and the Hilly Plateau region (HP) constitute the primary wind energy reserves, with peak wind speeds occurring in March (8.77 m s−1) and February (7.50 m s−1), respectively. These two regions demonstrate substantial seasonal amplitudes (4.34 m s−1 and 3.28 m s−1, respectively), dominating the strong wind characteristics of the “high-wind season”. Notably, the minimum wind speed in the EW region (4.43 m s−1) still exceeds the peak values of all other regions, underscoring its exceptional year-round power generation potential. The Plateau transition region (P) functions as a moderate-intensity buffer zone. The Northeastern Mountain region (NEM) exhibits a distinctive “spring peak, autumn trough” pattern, with wind speed peaks delayed until April (3.13 m s−1) and minimum values occurring in October (2.54 m s−1), displaying the smallest seasonal variation (amplitude 0.59 m s−1). This seasonal rhythm, divergent from other regions, likely originates from unique interactions between topography and atmospheric circulation, providing potential temporal complementarity for the power grid. In contrast, the Basin region (B), due to intense topographic sheltering effects, maintains the lowest wind speeds throughout the year (peak 2.29 m s−1), with very limited wind energy development potential.

Figure 5.

Seasonal patterns and spatial distribution of wind speed across different geographical regions. (a) Monthly mean wind speed for each sub-region (P, B, HP, NEM, EW) and the overall regional average. Upward-pointing (red) and downward-pointing (blue) triangles denote the months with maximum and minimum wind speeds, respectively. The inset table summarizes the timing of peak and minimum wind speeds for each region. (b) Spatial distribution of the geographical regions analyzed, with each color corresponding to a specific sub-region (as defined in the legend of Figure 3).

Analysis of diurnal wind speed variation patterns indicates that most regions of Sichuan Province exhibit nocturnal wind dominance, with nighttime wind speeds exceeding daytime values (Table 1). The Basin region (B) and Extreme Wind region (EW) demonstrate the most pronounced nocturnal advantage, both with annual mean night-to-day wind speed ratios of 1.15. The EW region maintains a stable strong nocturnal wind pattern throughout the year, indicating high reliability of its wind resources at the diurnal scale; whereas the high ratio in the B region is accompanied by elevated variability (large standard deviation), particularly during the weak-wind season (1.17 ± 0.22). An exception is the Hilly Plateau region (HP), which exhibits a distinctive “day-strong, night-weak” pattern during the high-wind season, with a night-to-day wind speed ratio representing the only value below 1.0 among all analyses (0.97 ± 0.13). This reversal phenomenon reveals that during this season, daytime momentum downward transport driven by large-scale weather systems exerts influence exceeding that of local thermal circulation. In contrast, the Northeastern Mountain region (NEM) displays the most stable diurnal variation pattern across seasons, manifesting persistent local circulation characteristics. These findings reveal substantial spatial heterogeneity in diurnal wind speed variations within the region. Notably, the potential day-night complementarity existing between the HP region (daytime dominance) and the EW region (nighttime dominance) offers valuable insights for optimizing wind energy integration and grid operation strategies.

Table 1.

Diurnal wind speed ratios (nighttime/daytime) across wind regimes and seasons in Sichuan Province (1979–2018). Values represent mean ± standard deviation of the ratio between nighttime (UTC 11–22, local 19:00–06:00) and daytime (UTC 23, 0–10, local 07:00–18:00) wind speeds derived from WRF 5 km simulations. Regions are defined as: P (Plateau transition zone), B (Basin calm wind zone), HP (High Wind Plateau), NEM (Northeast Mountains), and EW (Extreme Wind zone in Hengduan Mountains). Three seasons are identified through temporal clustering analysis based on wind speed patterns: Trans. Seas. (Transitional Seasons), High WS Seas. (High Wind Speed Season), and Low WS Seas. (Low Wind Speed Season). Ratios > 1.0 indicate stronger nighttime winds, characteristic of nocturnal low-level jets and katabatic flows in mountainous terrain.

3.2. Topographic Control on the Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Wind Energy Resources

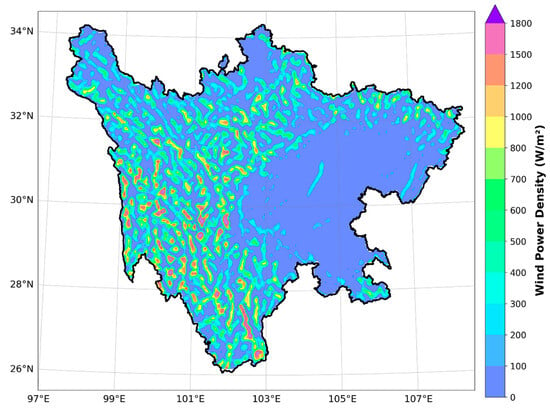

Figure 6 reveals a topographically dominated, pronounced east–west differentiation pattern in the annual mean wind power density (WPD) across Sichuan Province. Demarcated by the 103° E meridian, the eastern Sichuan Basin exhibits impoverished and uniformly distributed wind resources, with WPD generally below 100 W/m2. In stark contrast, the western region manifests as a heterogeneous mosaic of wind energy potential. A narrow transition zone distributes along the eastern margin of the Tibetan Plateau (102–103° E), where WPD increases abruptly, forming a distinct gradient. Wind-rich zones in the western plateau and mountainous areas, particularly in the core region of the northwestern Sichuan Plateau (97–101° E) and southern Liangshan Prefecture, do not conform to traditional contiguous plains in their high-value areas (>600 W/m2). Their spatial morphology presents a distinctive “venous” or “reticulated” structure, with high-WPD bands (800–1200 W/m2) clearly extending along mountain ranges and ridge orientations, punctuated by extreme-value cores. This fragmented, terrain-aligned distribution characteristic fundamentally indicates that premium wind resources in Sichuan Province are not directly controlled by large-scale weather systems, but rather result from the dominant role of topographic dynamic enhancement mechanisms. These include the “nozzle effect” of mesoscale topographic channels, airflow acceleration in passes and valleys, and dynamical effects generated by interactions between westerly circulation and the complex three-dimensional terrain of the Tibetan Plateau and Hengduan Mountains. This pattern underscores the necessity of high-resolution wind resource assessment in regions with complex underlying surfaces to identify such terrain-driven high-potential zones.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of annual mean wind power density (WPD) at 100 m height across Sichuan Province. WPD derived from WRF 5 km simulations over the period 1979–2018. The sharp east–west gradient reflects the dramatic topographic transition from the Sichuan Basin (east) to the eastern Tibetan Plateau (west).

Wind power density (WPD) in Sichuan Province exhibits a dual differentiation pattern governed by the interplay between topographic gradients and seasonal atmospheric circulation (Table 2). The Basin (B) and Northeastern Mountain (NEM) regions represent resource-poor zones, constrained by boundary layer decoupling and topographic shielding. Their annual mean WPD is limited to 48 ± 93 W/m2 and 133 ± 185 W/m2, respectively, characterized by low absolute values and weak seasonal fluctuations (high-to-low wind season ratios of 1.3–1.4). Corresponding to the abrupt elevation increase, the Plateau region (P) shows a surge in annual WPD to 303 ± 380 W/m2—exceeding sixfold that of the Basin. This region exhibits pronounced seasonality closely coupled with the intensity of the upper-level westerlies, with high-wind season WPD (406 W/m2) reaching 2.3 times that of the low-wind season (174 W/m2). The substantial standard deviation (±380 W/m2) further highlights the pronounced spatial heterogeneity modulated by the complex local terrain features within the plateau.

Table 2.

Wind power density (W/m2) at 100 m height across topographic zones and seasons in Sichuan Province (1979–2018). Values represent mean ± standard deviation derived from WRF 5 km simulation.

Local topographic dynamic enhancement further amplifies this pattern. The High Wind Plateau (HP) and Extreme Wind (EW) regions benefit from airflow acceleration effects (e.g., channeling along ridges and gorges), with annual mean WPD escalating to 731 ± 569 W/m2 and 1166 ± 961 W/m2, respectively. This represents a 2.4-fold and 3.8-fold increase over the plateau baseline. Their seasonality intensifies correspondingly, with high-to-low wind season ratios expanding to 2.8 and 3.3, and absolute amplitudes reaching 647 W/m2 and 1166 W/m2. Notably, even during the low-wind season, WPD in the EW region (515 W/m2) substantially exceeds the annual mean of the P region, confirming its exceptional resource superiority regardless of seasonal variations. Topography thus serves as the primary determinant, establishing both the spatial baseline (exceeding a 24-fold difference from Basin to EW) and amplifying the seasonal absolute amplitude from approximately 13 W/m2 in the Basin to 1166 W/m2 in the EW region.

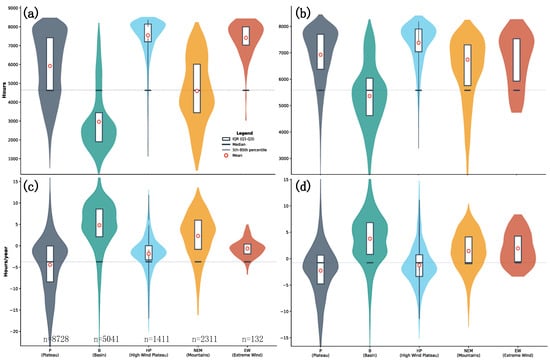

3.3. Comparative Assessment of Wind Availability for Different Turbine Technologies

Figure 7 presents a comparative analysis of the spatiotemporal evolution of annual available wind hours across five topographic zones in Sichuan Province (1979–2018), distinguishing between the standard operating window (3–25 m/s, left column) and the distributed low-speed window (2–15 m/s, right column). The distributional characteristics of climatological means (Figure 7a,b) reveal distinct resource patterns governed by the interaction between turbine thresholds and local aerodynamic conditions. Under the standard 3–25 m/s criterion (Figure 7a), the Extreme Wind (EW) and High Wind Plateau (HP) regions unequivocally constitute the core energy reserves, exhibiting median annual available hours of approximately 7500 and 7600 h, respectively, corresponding to an annual capacity factor exceeding 87%. The HP region displays exceptional spatial homogeneity, characterized by an extremely narrow interquartile range (IQR ≈ 1300 h), reflecting the relatively uniform surface roughness and consistent exposure to geostrophic winds typical of the plateau terrain. Whereas the EW region, despite comparable potential, presents an asymmetric violin shape indicative of localized extreme conditions, likely resulting from the uneven acceleration effects found in complex gorges. In sharp contrast, the Basin (B) appears resource-poor under this standard, physically constrained by the topographic shielding that decouples the basin boundary layer from strong synoptic flows, resulting in a median of only 2800 h and a highly concentrated low-value distribution.

Figure 7.

Spatiotemporal characteristics of annual available wind hours at 100 m height across five topographic zones in Sichuan Province (1979–2018). The top row (a,b) displays the distribution of the climatological mean annual available hours, while the bottom row (c,d) illustrates the long-term linear trends (hours/year). The left column (a,c) corresponds to the standard cut-in/cut-out wind speed range of 3–25 m/s, and the right column (b,d) corresponds to the lower wind speed range of 2–15 m/s. In the violin plots, the white boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR, Q1–Q3), the black horizontal lines indicate the median, the red circles denote the mean values, and the width of the shaded area represents the data density. The dash lines represent the mean value of the wind hours. The sample size (n) representing the number of 5 km grid cells for each zone is listed in subplots. Data are derived from WRF simulations. Abbreviations: P (Plateau), B (Basin), HP (High Wind Plateau), NEM (Northeast Mountains), EW (Extreme Wind).

However, shifting to the 2–15 m/s window (Figure 7b) substantially reshapes this landscape. The Basin region benefits from a significant “light breeze dividend,” where median available hours surge dramatically to approximately 5300 h. This transformation captures the frequent thermally driven local circulations (e.g., mountain-valley breezes) that prevail in this sheltered environment, converting the region from a commercially unviable zone to one possessing specific potential for low-power applications. Conversely, the EW region exhibits a “high-speed penalty” in this lower threshold window; its comparative advantage diminishes as wind speeds frequently exceed the 15 m/s cut-out limit, driven by intense channeling effects that accelerate airflow beyond the operational range of small turbines. Meanwhile, the Northeast Mountains (NEM) region demonstrates the highest spatial heterogeneity across both windows, with the widest IQRs necessitating refined micro-siting strategies to adapt to the diverse exposure conditions created by the rugged ridge-valley topography.

The long-term temporal trends (Figure 7c,d) further highlight divergent evolutionary trajectories over the four-decade period. For the standard 3–25 m/s window (Figure 7c), the HP region shows a systematic weakening signal with a median trend of −2 h/year, while the EW region exhibits high stability with a median trend near zero (−1 h/year). Notably, the Basin (B) is the only zone displaying a significant positive trend in this window (median +5 h/year), representing a cumulative increase of approximately 7% over 40 years. When analyzing the 2–15 m/s window (Figure 7d), the Basin’s strengthening trend remains robust and universally significant (median +4 h/year), indicating a consistent improvement in light wind resources. A marked contrast is observed in the EW region, which shifts from the slight negative trend observed in the standard window to a distinct positive trend (+1.5 h/year) in the low-speed window. This suggests that while extreme wind events may be fluctuating, the baseline wind energy availability remains climatologically robust. The Plateau (P) region demonstrates the greatest complexity in both scenarios, characterized by broad trend distributions that encompass areas of both significant strengthening and weakening, reflecting a high degree of spatial differentiation in climate response likely modulated by local topographic orientation. Overall, while the HP region remains the premier resource base despite slight weakening (−1 to −2 h/year), the revaluation of the Basin’s increasing low-speed potential offers new perspectives for distributed energy planning.

3.4. Long-Term Operational Risk Assessment Under Climate Variability

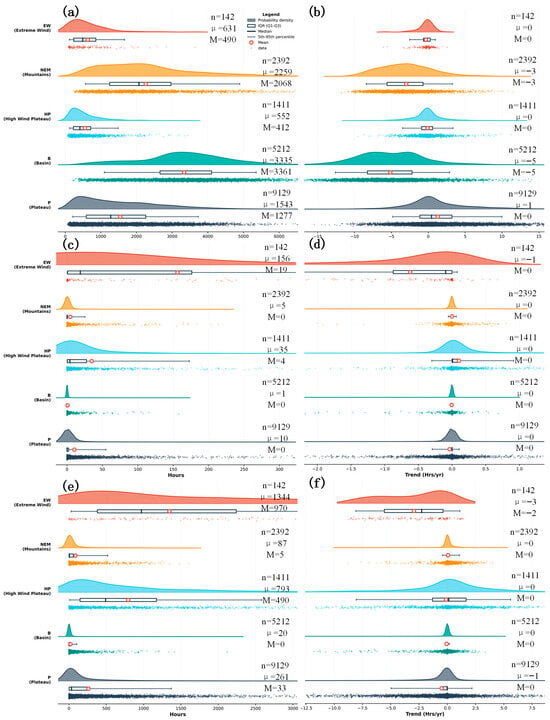

Figure 8a illustrates the spatial distribution of annual calm wind hours (wind speeds below 2 m/s), revealing pronounced polarization in wind resource availability across Sichuan Province. The Basin (B) region is climatologically characterized by predominantly calm conditions, primarily attributed to the profound shielding effect of the surrounding mountain barriers which isolate the basin boundary layer from large-scale circulation. With a median (M) of 3361 h and a mean (μ) of 3335 h, wind speeds in the Basin are insufficient for turbine cut-in for approximately 38% of the year, fundamentally constraining commercial scalability. In stark contrast, the High Wind Plateau (HP) and Extreme Wind (EW) regions demonstrate superior resource continuity, benefiting from their elevated exposure to free-tropospheric westerlies and topographic channeling effects that accelerate airflow. The HP region, serving as a core development zone, records the lowest incidence of calm winds with a median of 412 h (μ = 552 h), while the EW region follows closely with a median of 490 h (μ = 631 h). The probability distributions for HP and EW are notably narrow and right-skewed, confirming high consistency of available wind speeds. The Northeastern Mountain (NEM) region represents a transitional zone with moderate values (M = 2068 h) but exhibits the widest distribution dispersion, reflecting extreme spatial heterogeneity driven by the high surface roughness and complex ridge-valley interactions typical of this terrain.

Figure 8.

Spatiotemporal characteristics of non-operational wind speed events at 100 m height across five topographic zones in Sichuan Province (1979–2018). The rows represent three distinct constraints: (a,b) calm wind conditions (below 2 m/s); (c,d) standard cut-out wind speed (above 25 m/s); and (e,f) distributed wind turbine cut-out speed (above 15 m/s). The left column (a,c,e) displays raincloud plots of the climatological mean annual hours, illustrating the data distribution, box plots (white box: IQR; black line: median; red circle: mean), and raw data jitter. The right column (b,d,f) displays the distribution of linear trend slopes (hours/year) for the corresponding metrics. Statistical annotations include sample size (n), mean (μ), and median (M). Data are derived from WRF simulations. Abbreviations: B (Basin), NEM (Northeast Mountains), P (Plateau), HP (High Wind Plateau), EW (Extreme Wind).

The temporal evolution of calm winds over the 40-year period (1979–2018), shown in Figure 8b, highlights divergent regional trajectories. The Basin (B) displays a significant and robust signal of resource improvement, characterized by a negative trend in calm hours with both median and mean linear slopes of −5 h/year. This equates to a cumulative reduction of approximately 200 h of calm conditions over the study period. The Northeastern Mountain (NEM) region similarly exhibits an improving trend (μ = −3, M = −3 h/year), suggesting a gradual increase in wind availability. Conversely, the high-quality resource zones (HP and EW) exhibit remarkable stability. The trend distributions for the HP and EW regions are tightly concentrated around zero (μ = 0, M = 0), indicating that the superior continuity of wind resources in these regions is climatologically robust and has not been significantly altered by long-term climate variability. Regarding operational safety constraints, Figure 8c presents the distribution of annual overspeed shutdown hours (wind speeds exceeding 25 m/s). Substantial gradient differentiation is evident. The Extreme Wind (EW) region presents the highest operational risk profile, with a mean of 156 h/year and a median of 19 h/year. The large discrepancy between mean and median, combined with the long-tailed distribution, indicates the presence of specific grid cells subject to severe topographic acceleration (e.g., the Venturi effect in narrow gorges), necessitating high-class turbine specifications. Conversely, the High Wind Plateau (HP) demonstrates an optimal risk-benefit balance for large-scale bases. Despite being a high-wind zone, its annual shutdown duration is minimal (M = 4 h, μ = 35 h), suggesting that wind speeds rarely exceed the 25 m/s safety threshold. The Basin (B) and Northeastern Mountain (NEM) regions effectively face negligible operational risk from standard cut-out speeds (M = 0).

Regarding long-term trends of these safety risks (Figure 8d), the landscape is characterized by stability. The HP, Basin, and Plateau regions show trend distributions centered strictly on zero (M = 0, μ = 0), implying no significant climatological intensification of extreme wind risks. The EW region exhibits a slight negative tendency (μ = −1 h/year), suggesting marginal amelioration in operational safety risks over the multidecadal period. Finally, Figure 8e,f evaluate the “high-speed penalty” relevant to distributed or small-scale wind turbines with a lower cut-out threshold (exceeding 15 m/s). This parameter substantially reshapes the resource assessment for the EW region. Under this stricter constraint, the EW region experiences severe loss of operational time, with a mean of 1344 h and a median of 970 h lost annually to overspeed events. This high-speed penalty is significantly lower in the HP region (M = 490 h, μ = 793 h), reinforcing the HP region’s status as the most balanced zone for standardized deployment. Notably, the long-term trends for this parameter (Figure 8f) reveal specific dynamics in the EW region: a distinct declining trend in overspeed hours (μ = −3, M = −2 h/year). This trend represents a positive signal for distributed applications in the EW zone, as the frequency of events exceeding the 15 m/s threshold is progressively decreasing, thereby gradually expanding the effective operational window over time. All other regions maintain high stability with trend distributions centered near zero.

4. Discussion

This study employs high-resolution WRF simulations to systematically reveal the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of wind energy resources under the complex topography of Sichuan Province. By innovatively constructing a differentiated assessment framework that distinguishes between “utility-scale” (centralized) and “distributed” application scenarios, this work provides critical scientific evidence for wind power development strategies in regions with extremely complex terrain.

4.1. Reevaluating Resource Suitability Through a Technical Perspective

The simulation results first quantify the resource endowment differences across topographic units. The High Wind Plateau (HP) and Extreme Wind (EW) regions exhibit annual mean wind power densities reaching 731 W/m2 and 1166 W/m2, respectively, establishing their status as core zones for centralized wind power development based on data. However, high-resolution simulations further reveal a significant divergence in operational risks between the two: the annual mean overspeed shutdown duration (>25 m/s) in the EW region exceeds that of the HP region by more than 4.45 times. This data-driven comparison intuitively indicates that although the EW region possesses extremely high mean wind energy, its extreme instantaneous wind speed characteristics pose immense stability challenges, which are often masked by average states in lower-resolution assessments.

When the assessment perspective shifts to distributed turbines (2–15 m/s), the resource distribution landscape undergoes a fundamental reversal. The annual available hours in the Basin (B) region surge from 2800 h under the conventional view to 5300 h (an increase of approximately 89%). This significant “low wind speed dividend” demonstrates that this region possesses substantial, previously underestimated time windows suitable for the operation of low-cut-in turbines. These results quantitatively confirm that in complex terrain, so-called “resource superiority” is not absolute but strictly depends on the matching degree between technical parameters and local wind regime distributions.

4.2. Physical Interpretation of Model Biases and Limitations

Regarding validation performance, we acknowledge the systematic positive bias (median +0.91 m/s) identified in the WRF simulations. We do not consider this merely a numerical error, but attribute it physically to the inherent “representativeness mismatch” in complex terrain modeling. Observation stations in the mountainous areas of Sichuan are predominantly sited in habitable valley bottoms for maintenance accessibility (topographically shielded), whereas the 5 km grid cells aggregate momentum from both sheltered valleys and exposed ridge lines (high wind speeds). Consequently, the grid-averaged wind speed inevitably exceeds the point-based valley observation values. Applying simple statistical bias correction in such highly heterogeneous terrain would risk distorting the physical consistency of the wind field. Therefore, although absolute design values should be interpreted with caution, the relative spatial patterns, regional contrasts, and temporal trends revealed in this study remain robust and physically consistent.

4.3. Practical Implications for Regional Planning

Despite data limitations, the resource patterns revealed in this study offer concrete scientific references for regional planning. First, for the resource-rich HP and EW regions, the results confirm their potential as centralized bases. However, the quantified high shutdown risks indicate that development efficiency depends not on the accumulation of turbine numbers, but on their adaptability to extreme conditions. Selecting turbines with wider cut-out thresholds (e.g., typhoon-resistant models) is more effective for reducing generation loss than simply pursuing larger capacities. Second, the assessment of the Basin region breaks the traditional stereotype of it being a “wind-poor zone.” Data shows that by matching low-cut-in distributed units, this region can transform from an ineffective area into a valid energy supplement. Conversely, deploying small-scale turbines in the EW region proves inefficient, as frequent overspeed events lead to significant resource waste (i.e., the “high-speed penalty”). In summary, in complex terrain, simply finding the “windiest spots” is insufficient. This study demonstrates that precisely matching turbine technical parameters (e.g., operating windows) with local wind regimes—rather than adopting a “one-size-fits-all” approach—is the key pathway to maximizing wind energy utilization. This study employs high-resolution WRF simulations to systematically reveal the spatiotemporal heterogeneity of wind energy resources under Sichuan Province’s complex topography. By innovatively constructing a differentiated assessment framework that distinguishes between utility-scale and distributed application scenarios, this work provides critical scientific evidence for wind power development strategies in regions with extremely complex terrain.

5. Conclusions

Based on 40 years of high-resolution WRF simulation data, this study provides a systematic assessment of wind energy resources and their long-term evolution under Sichuan Province’s complex topography. The main conclusions are as follows:

1. Topography dictates a stark west–east differentiation in wind resources. The complex terrain creates a steep gradient in Wind Power Density (WPD). The Extreme Wind (EW) region achieves an annual mean WPD of 1166 W/m2, establishing its status as a core resource zone alongside the High Wind Plateau (HP, 731 W/m2). In contrast, the topographically shielded Basin (B) region remains resource-poor (48 W/m2) under conventional assessment standards.

2. Technological scale fundamentally redefines resource availability. Switching from utility-scale (3–25 m/s) to distributed (2–15 m/s) evaluation windows reveals a significant “technology-resource mismatch.” The traditionally “wind-poor” Basin gains a “light breeze dividend,” with available hours surging by approximately 89% (to 5300 h). Conversely, deploying small-scale turbines in the “wind-rich” EW region is inefficient due to frequent cut-out events. This underscores that resource suitability in complex terrain is not absolute but contingent on specific turbine operating thresholds.

3. High resource potential is coupled with distinct operational risks. While the EW region offers maximum energy density, it faces severe stability challenges. Its annual mean overspeed shutdown duration (>25 m/s) exceeds that of the HP region by more than 4.45 times. This identifies the HP region as the optimal balance for standardized large-scale deployment, whereas the EW region necessitates specialized climate-resilient turbine specifications to mitigate extreme wind risks.

4. Long-term evolution exhibits regional non-stationarity. Over the 40-year period, the Basin region shows a robust increasing trend in low-speed wind availability (+5 h/year). Crucially, the high-risk EW region exhibits a stabilizing trend, with high-wind periods (>15 m/s) decreasing definitively (−2 h/year), indicating a progressive improvement in the operational environment.

5. Implications for regional planning. Despite the systematic positive bias in WRF simulations—physically attributed to the “representativeness mismatch” between ridge-resolving grids and valley-bottom observations—the relative spatial patterns provide robust guidance. Effective development requires a differentiated strategy, prioritizing climate-resilient turbines for centralized bases in the west and leveraging low-cut-in distributed technologies to unlock the potential of the eastern basin.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, data analysis, and writing—original draft preparation were performed by R.Z.; supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition were handled by Z.W.; and methodology and writing—review and editing were performed by L.B.; methodology, R.Z., Z.W. and J.L.; software, R.Z. and H.Z.; validation, R.Z., C.H., Z.W. and J.L.; formal analysis, R.Z., H.Z. and J.L.; investigation, R.Z., C.H. and J.D.; resources, Z.W., B.C. and L.B.; data curation, R.Z. and H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.W., L.B., B.C. and J.L.; visualization, R.Z. and H.Z.; supervision, Z.W. and L.B.; project administration, Z.W. and L.B.; funding acquisition, Z.W. and L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by China Datang Corporation Science and Technology General Research Institute Ltd. (Grant No. DTKY-2023-20532), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32260294), the “Tianshan Talent” Training Program-Science and Technology Innovation Team (Tianshan Innovation Team) Project (2022TSYCTD0007), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (Grant No. 425RC692).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author due to institute restriction.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors Rui Zhu, Haiku Zhang, Chuankai He, Zhiding Wu, Jun Dai, and Bin Chen were employed by the company Datang Hydropower Science & Technology Research Institute Co., Ltd. The remaining authors (Junjiang Liu and Lei Bai) declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Nomenclature

| Abbreviation /Symbol | Full Name /Description | Note /Definition |

| B | Basin Region | The low-lying Sichuan Basin characterized by low wind speeds. |

| EW | Extreme Wind Region | Areas with the highest wind resources, located in localized gorges and passes. |

| HP | High Wind Plateau | The Hilly Plateau region, including parts of the Hengduan Mountains. |

| NEM | Northeastern Mountains | The Daba Mountains region, acting as a dynamic barrier. |

| P | Plateau Region | The transition zone of the eastern Tibetan Plateau. |

| AWS | Automatic Weather Station | Ground-based observation stations used for validation6. |

| ERA5 | ECMWF Reanalysis v5 | Global atmospheric reanalysis dataset used as boundary conditions. |

| IQR | Interquartile Range | Statistical measure of spread (difference between 75th and 25th percentiles). |

| KDE | Kernel Density Estimation | A non-parametric way to estimate the probability density function of a variable. |

| MB | Mean Bias | Systematic error metric (Model minus Observation). |

| NWP | Numerical Weather Prediction | Mathematical models of the atmosphere. |

| WPD | Wind Power Density | The power available in the wind per unit area (W/m2). |

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting | The mesoscale numerical weather prediction system used for downscaling. |

| ρ | Air Density | Standard value set to 1.225 kg/m3. |

| α | Wind Shear Exponent | Coefficient used in the power law for vertical wind profile extrapolation. |

| r | Spearman Correlation Coefficient | Metric used to assess the correlation between simulated and observed data. |

Appendix A

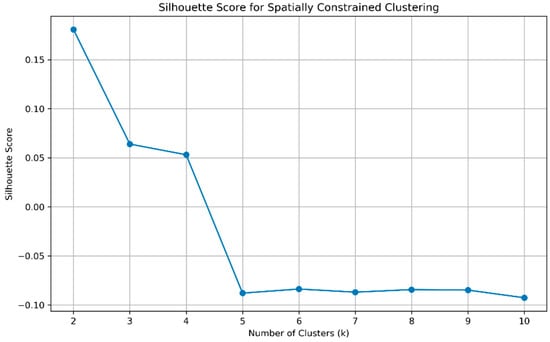

To objectively delineate wind energy characteristic zones across Sichuan Province, this study employed a spatially constrained hierarchical clustering algorithm, with silhouette scores used to evaluate partition quality across different cluster numbers (k = 2 to 10). The silhouette score assesses clustering performance by measuring intra-cluster cohesion and inter-cluster separation. The analysis results (Figure A1) revealed that the silhouette score reached its maximum value (~0.175) at k = 2, representing the optimal solution from a purely statistical perspective. However, such a simple binary partition scheme (e.g., plateau-basin dichotomy) proves overly coarse, failing to capture critical mesoscale wind field characteristics driven by complex topography. Systematic evaluation of all partition schemes demonstrated that k = 5 yielded results highly consistent with Sichuan Province’s macroscopic geographical patterns and meteorological characteristics, successfully identifying five regions with clear physical significance. Conversely, when k ≥ 6, the partition results became spatially fragmented and lacked coherent physical patterns. Therefore, despite the negative silhouette score at k = 5 (potentially reflecting natural gradual transition zones between regions), comprehensive consideration of geographical representativeness, uniqueness of physical mechanisms, and interpretability and practical value of the final scheme led to the selection of k = 5 as the optimal partition solution.

Figure A1.

Silhouette Score analysis based on spatially constrained hierarchical clustering algorithm.

References

- Antonini, E.G.; Virgüez, E.; Ashfaq, S.; Duan, L.; Ruggles, T.H.; Caldeira, K. Identification of reliable locations for wind power generation through a global analysis of wind droughts. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, H.C.; Brayshaw, D.J.; Shaffrey, L.C.; Coker, P.J.; Thornton, H.E. The changing sensitivity of power systems to meteorological drivers: A case study of Great Britain. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 054028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Shen, L.; Zeng, Z.; Yang, B.; Zhong, H.; Yang, X.; Lu, X. Prolonged wind droughts in a warming climate threaten global wind power security. Nat. Clim. Change 2025, 15, 842–849. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Z.; Ziegler, A.D.; Searchinger, T.; Yang, L.; Chen, A.; Ju, K.; Piao, S.; Li, L.Z.; Ciais, P.; Chen, D. A reversal in global terrestrial stilling and its implications for wind energy production. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 979–985. [Google Scholar]

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Notice on Issuing the “14th Five-Year Plan for Renewable Energy Development”. 2022. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xwdt/tzgg/202206/t20220601_1326720.html (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Chinese)

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC). Opinions on Improving the Institutional Mechanisms and Policy Measures for a Green and Low-Carbon Energy Transition (NDRC Energy [2022] No. 206). 2022. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/tz/202202/t20220210_1314511.html (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Chinese)

- Bianchini, A.; Bangga, G.; Baring-Gould, I.; Croce, A.; Cruz, J.I.; Damiani, R.; Erfort, G.; Simão Ferreira, C.; Infield, D.; Nayeri, C.N. Current status and grand challenges for small wind turbine technology. Wind Energy Sci. 2022, 7, 2003–2037. [Google Scholar]

- Karimian, S.; Abdolahifar, A. Performance investigation of a new Darrieus vertical axis wind turbine. Energy 2020, 191, 116551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraschivoiu, I. Wind Turbine Design: With Emphasis on Darrieus Concept; Polytechnic International Press: Montréal, QC, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Tan, Z.; Du, E.; Liu, N.; Ma, J.; Sun, M.; Li, C.; Song, J.; Lu, X. Inherent spatiotemporal uncertainty of renewable power in China. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, M.; Li, Y.; Qin, J.; Wei, K.; Song, L. Analysis of wind characteristics and wind energy potential in complex mountainous region in southwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 274, 123036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, J.A.; Ramírez, P.; Velázquez, S. A review of wind speed probability distributions used in wind energy analysis: Case studies in the Canary Islands. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 933–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carta, J.A.; Velázquez, S.; Cabrera, P. A review of measure–correlate–predict (MCP) methods used to estimate long-term wind characteristics at a target site. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 27, 362–400. [Google Scholar]

- Möhrlen, C.; Zack, J.W.; Giebel, G. IEA Wind Recommended Practice for the Implementation of Renewable Energy Forecasting Solutions; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Liu, Y.; Chappell, A.; Dong, L.; Xu, R.; Ekström, M.; Fu, T.; Zeng, Z. Evaluation of global reanalysis land surface wind speed trends to support wind energy development using in situ observations. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2021, 60, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, K.; Regner, P.; Wehrle, S.; Zeyringer, M.; Schmidt, J. Towards global validation of wind power simulations: A multi-country assessment of wind power simulation from MERRA-2 and ERA5 reanalyses bias-corrected with the Global Wind Atlas. Energy 2022, 238, 121520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelaro, R.; McCarty, W.; Suárez, M.J.; Todling, R.; Molod, A.; Takacs, L.; Randles, C.A.; Darmenov, A.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Reichle, R.; et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 2017, 30, 5419–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, S.; Ota, Y.; Harada, Y.; Ebita, A.; Moriya, M.; Onoda, H.; Onogi, K.; Kamahori, H.; Kobayashi, C.; Endo, H. The JRA-55 reanalysis: General specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 2015, 93, 5–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Jiang, L.; Shi, C.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, Z.; Liao, J.; Yao, S.; Liu, J.; Wang, M.; Wang, H. CRA-40/atmosphere—The first-generation Chinese atmospheric reanalysis (1979–2018): System description and performance evaluation. J. Meteorol. Res. 2023, 37, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahmann, A.N.; Sile, T.; Witha, B.; Davis, N.N.; Dörenkämper, M.; Ezber, Y.; García-Bustamante, E.; González Rouco, J.F.; Navarro, J.; Olsen, B.T. The making of the new European Wind Atlas, Part 1: Model sensitivity. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 5053–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horvath, K.; Koracin, D.; Vellore, R.; Jiang, J.; Belu, R. Sub-kilometer dynamical downscaling of near-surface winds in complex terrain using WRF and MM5 mesoscale models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2012, 117, D11111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, L.; Zhang, F.; Tan, J.; Wang, C. Numerical simulation of near-surface wind during a severe wind event in complex terrain by multisource data assimilation and dynamic downscaling. Adv. Meteorol. 2020, 2020, 7910532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodini, N.; Castagneri, S. Long-term uncertainty quantification in WRF-modeled offshore wind resource off the US Atlantic coast. Wind Energy Sci. 2023, 8, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haupt, S.E.; Kosović, B.; Shaw, W.; Berg, L.K.; Churchfield, M.; Cline, J.; Draxl, C.; Ennis, B.; Koo, E.; Kotamarthi, R.; et al. On bridging a modeling scale gap: Mesoscale to microscale coupling for wind energy. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2019, 100, 2533–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Yue, P.; Liu, Q.; He, X.; Wang, Z. Wind field characteristics of complex terrain based on experimental and numerical investigation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedjari, H.D.; Guerri, O.; Saighi, M. CFD wind turbines wake assessment in complex topography. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 138, 224–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, R.J.A.M.; Meneveau, C. Flow structure and turbulence in wind farms. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2017, 49, 311–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichuan Provincial People’s Government. Why Does Sichuan—A Hydropower-Rich Province—Still Face Power Shortages? 2022. Available online: https://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/10464/13722/2022/8/18/a041da76a6cd45b79b9f39d89b06187d.shtml (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Chinese)

- Sichuan Provincial People’s Government. Sichuan Coordinates Multiple Parties and Multiple Measures to Ensure Power Supply. 2022. Available online: https://www.sc.gov.cn/10462/10464/10465/10574/2022/8/13/1cf87d99f7fa496e85dcc9a05ccf9ffc.shtml (accessed on 17 October 2025). (In Chinese)

- Ma, M.; Qu, Y.; Lyu, J.; Zhang, X.; Su, Z.; Gao, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, J. The 2022 extreme drought in the Yangtze River Basin: Characteristics, causes and response strategies. River 2022, 1, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Huang, X.; Shi, J.; Li, K.; Cai, J.; Zhang, X. Complementary potential of wind–solar–hydro power in Chinese provinces: Based on a high temporal resolution multi-objective optimization model. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 184, 113566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, W.; Wang, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J. Current status, challenges, and perspectives of Sichuan’s renewable energy development in Southwest China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 57, 1373–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, A.; Barber, S.; Stökl, A.; Frank, H.; Karlsson, T. Research challenges and needs for the deployment of wind energy in hilly and mountainous regions. Wind Energy Sci. 2022, 7, 2231–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Kammen, D.M. Where, when and how much wind is available? A provincial-scale wind resource assessment for China. Energy Policy 2014, 74, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, C.; Wei, R.; Zhao, L.; Chen, S.; Shen, C. Optimal distribution modeling and multifractal analysis of wind speed in the complex terrain of Sichuan Province, China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, L.; Ding, Z.; Fu, Y. From macro to micro: A multi-scale method for assessing coastal wind energy potential in China. Appl. Energy 2025, 389, 125729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadhim, M.A.; Phing, C.C.; Wai, L.C.; Paw, J.K.S.; Tak, Y.C.; Kadirgama, K.; Kadhim, A.A. Performance study of low-speed wind energy harvesting by micro wind turbine system. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 3712–3727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, X.; Liu, P. A comparative study of near-surface wind speed observations and reanalysis datasets in China over the past 38 years. Int. J. Climatol. 2025, 45, e8738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vautard, R.; Cattiaux, J.; Yiou, P.; Thépaut, J.; Ciais, P. Northern Hemisphere atmospheric stilling partly attributed to an increase in surface roughness. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justus, C.G.; Mikhail, A. Height variation of wind speed and wind distribution statistics. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1976, 3, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manwell, J.F.; McGowan, J.G.; Rogers, A.L. Wind Energy Explained: Theory, Design and Application, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Xu, M.; Hu, Q. Changes in near-surface wind speed in China: 1969–2005. Int. J. Climatol. 2011, 31, 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).