1. Introduction

As the global urbanization drive gathers pace and industrialization scales up, air pollution has evolved into a critical environmental concern that holds back the sustainable advancement of society. This form of pollution gives rise to numerous health issues, including respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular conditions and premature mortality, while also bringing about considerable risks to ecological systems [

1]. In China, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, as a core engine of economic development and a densely populated area, has always attracted wide attention at home and abroad regarding its air quality. Air pollution monitoring plays a vital role in assessing atmospheric pollutant concentrations against ambient air quality criteria, and it also serves as a core component for implementing effective air quality governance [

2,

3]. However, the sources and types of air pollution are complex and change with time and geographical location, making it difficult to predict air quality [

4]. In January 2024, China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment put forward that priority should be given to bolstering the technical capacity for air quality forecasting, with its core objective being to enhance the overall accuracy of such forecasts over a 72-h timeframe, and in particular, to overcome the key technical bottlenecks in the prediction and forecasting of heavy pollution weather processes. By the end of 2025, provincial and municipal ecological environment monitoring and forecasting institutions shall fully possess the ability to forecast air quality for 7–10 days. The supply of effective air quality prediction information enables governments to devise and enforce environmental protection policies in a scientific way, which in turn promotes the development of a green economy and achieves the goal of sustainable urban development [

5].

At present, the academic community has developed various technical paths around air quality prediction, ranging from early traditional models based on the statistical laws of data, to machine learning methods relying on nonlinear mapping capabilities, and then to deep learning architectures with deep feature mining capabilities [

6]. Various methods show differentiated advantages in prediction accuracy, applicable scenarios, and computational efficiency [

7,

8]. Meanwhile, the advancement of feature selection techniques also serves as a crucial safeguard for optimizing model inputs and enhancing predictive performance.

Early air quality prediction mainly relied on traditional statistical models, which center on data’s temporal regularity or linear correlation. Time series analysis is a key branch, with the ARIMA model widely used for Air Quality Index (AQI) prediction due to its good univariate time series fitting. Zhong et al. (2024) improved ARIMA to address nonlinearity and non-stationarity of carbon emission data, verifying its accuracy and efficiency [

9]. In addition, The multiple linear regression model establishes linear correlations between multi-factors and air quality. Ma et al. (2020) used SPSS tools to construct a multiple linear regression model, and selected five types of pollutants as the key factors affecting AQI and it was proved that the model has practical promotion value in air quality prediction [

10]. Mendes et al. (2022) proposed a statistical prediction method combining Classification and Regression Trees and Multiple Regression, and applied it to air quality prediction in Lisbon, Madeira, and Macao. It predicts next-day

and

concentrations, with

0.50–0.89, well following pollutant trends [

11].

As air quality data grows in dimension and complexity, traditional statistical models show prominent limitations in adapting to its nonlinear and non-stationary traits. In contrast, machine learning models have become a key breakthrough for air quality prediction. Support Vector Machines (SVM) demonstrate unique advantages in predicting data characterized by limited sample quantities and elevated dimensionality. Kulkarni et al. (2022) developed an SVM-based system to forecast AQI and concentrations of pollutants in the next 15 h, outperforming linear models in Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [

12]. In addition, Yu et al. (2025) [

13] proposed an attention-enhanced Random Forest for multi-pollutant estimation to address single-pollutant focus in prior studies. Experimental validation demonstrated superiority over other single-task comparison models, as evidenced by an increase in

from 9% to 26%; Varghese et al. (2023) built an Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)-regression model and combined multiple pollutants such as Pb,

,

,

with meteorological data for prediction, achieving higher accuracy than traditional models [

14]. Van et al. (2023) proposed an AQI prediction method combining data processing technology and lightweight machine learning algorithms, and comparisons on Indian regional datasets showed XGBoost is optimal in Mean Absolute Error (MAE), RMSE, and

among Decision Tree, Random Forest, and XGBoost [

15]. Despite machine learning’s higher accuracy than traditional models, single machine learning models still face issues like heavy reliance on feature engineering and insufficient capture of long-term temporal dependencies, driving research into deep learning models with stronger deep feature mining capabilities.

Deep learning models, by constructing a multi-layer neural network structure, can realize in-depth mining of spatiotemporal features and long short-term temporal dependencies, and effectively solve the performance bottlenecks of machine learning models in complex scenarios [

16,

17]. Zhou (2023) [

18] tackled the constraint that Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) focuses solely on historical information, and put forward an air quality prediction model built on an improved LSTM. This model leverages a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) network to read data in both forward and backward directions, enabling the extraction of more comprehensive temporal characteristics. It also incorporates an attention mechanism to assign weights to the outputs of the BiLSTM hidden layer, thereby realizing the selective utilization of key input information. In addition, CNN, relying on their local feature extraction capabilities, provide a new idea for predicting the spatial distribution of air quality. Wang et al. (2024) [

19] constructed a CNN model to predict the CO concentration with a 10-m resolution in Nanjing. The model input integrates various factors such as building height, terrain, and emission sources. The results showed that the

of the CNN prediction results is greater than 0.8, confirming its spatial generalization ability.

To further integrate the capabilities of capturing long-term temporal dependencies, hybrid deep learning architectures have become a research hotspot. Gilik et al. (2022) [

20] put forward a deep learning model based on CNN and LSTM. In the pollutant prediction of three cities, compared with the single-hidden-layer LSTM, this model reduced the prediction error of PM by 11–53%,

by 20–31%, nitrogen oxides by 9–47%, and

by 18–46%. Currently, prediction performance is largely affected by the architecture of deep learning models; different model architectures exhibit different performance. How to propose an applicable model architecture for specific problems remains a highly challenging issue.

Although deep learning models have significantly improved prediction performance, the increase in model complexity has also brought about the problem of feature redundancy. Therefore, efficient feature selection technology has become the key to optimizing model input and computational efficiency. Feature selection approaches rooted in deep learning algorithms have found widespread application in air quality prediction, thanks to their capacity to quantify the importance of features. Jamei et al. (2022) [

21] used XGBoost and CART to screen key prediction factors, and determined the optimal input combination through Best Subset Regression (BSR). After inputting this combination into the LSTM model, the prediction accuracy of

and

was better than that of models such as LightGBM. Tao made use of the Boruta feature selection method to determine which input variables are most significant. Based on three daily AQI sequences in China, experiments were carried out, which verified that the model could yield positive outcomes for these three cities [

22]. Currently, significant progress has been made in feature selection technology, but there remains a challenge in how to select the optimal algorithm for air quality prediction problems. The attention mechanism allows the model to focus more on important details, and how to apply it to the air quality prediction problem remains a challenge. In addition, feature selection involves hyperparameters and how to reasonably set the hyperparameters is also an issue that needs to be considered.

To solve the above problems, this study constructed an attention-enhanced hybrid neural network and took three core cities (Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang) in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region as research objects. It designed single-model multivariable comparison experiments, feature selection method comparison experiments, hyperparameter optimization comparison experiments, robustness tests, and Diebold–Mariano (DM) tests.

The novelty of this research manifests itself in the three aspects outlined below. First, in the model construction part, a CNN-BiLSTM-Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU)-Attention hybrid architecture is built. The CNN extracts the local spatiotemporal correlational features of pollutants, and the BiLSTM and GRU collaborate to capture both long-term and short-term temporal associations; the Attention mechanism strengthens the influence of pollution peak periods and key factors through dynamic weight allocation, designing a hybrid prediction model with adaptive feature selection, which breaks through the performance bottleneck of traditional models. Second, the Relief_F algorithm is used to measure the correlation weight between features and AQI, and core features are screened in combination with dynamic thresholds. Finally, in the hyperparameter optimization part, the Bat Optimization (BAT) algorithm is introduced to adaptively select the feature selection threshold of the Relief_F algorithm.

The subsequent sections of this paper are structured as follows.

Section 1 introduces the problem definition and the methods used.

Section 2 presents the proposed hybrid model prediction framework.

Section 3 includes information on the data set, data processing, and the design of comparison experiments.

Section 4 describes the comparison experiments and the discussion of experimental results.

Section 5 is the conclusion part.

2. Proposed Model

2.1. Proposed Model Framework

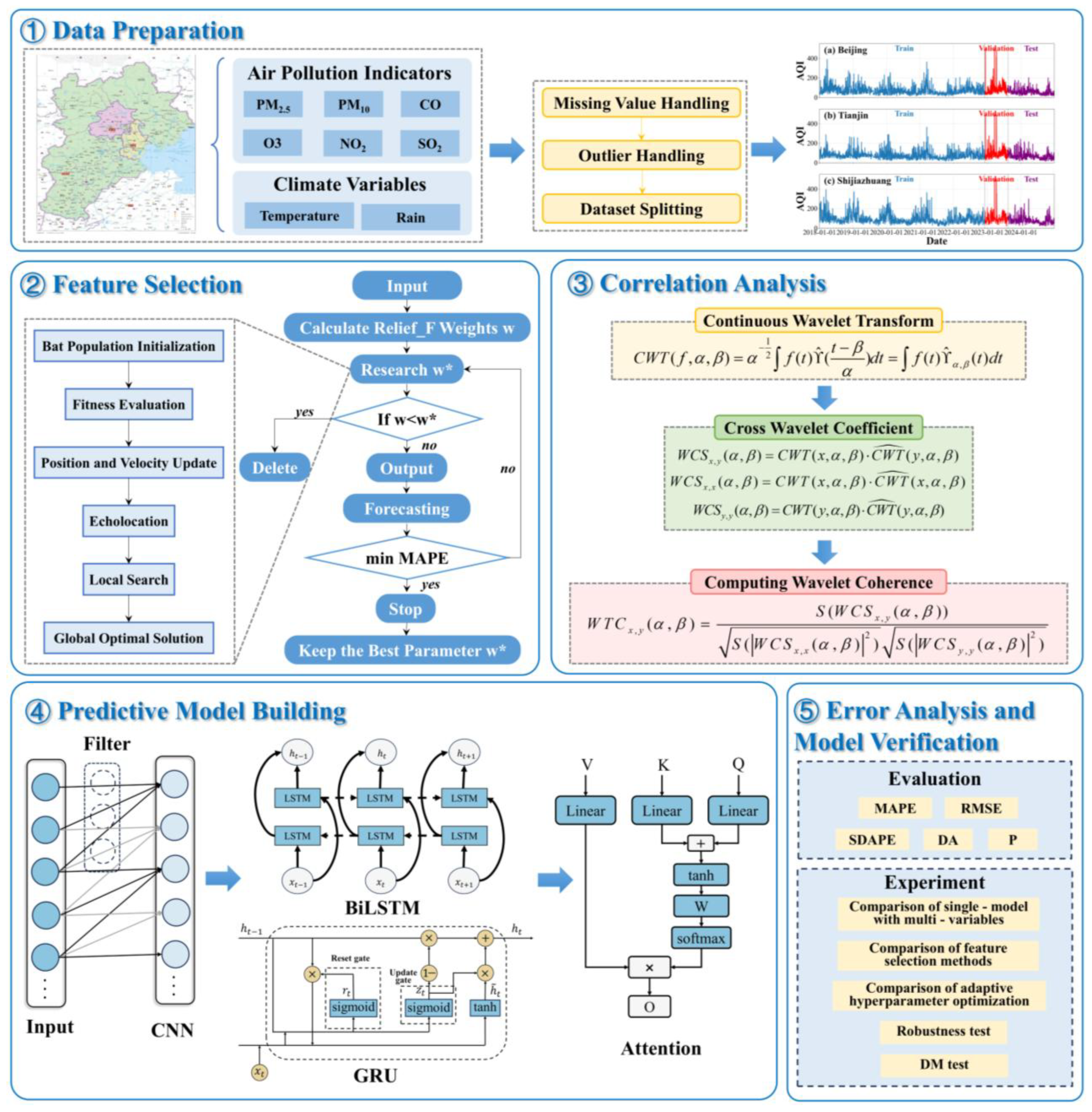

The BAT-Relief_F-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention model proposed in this paper achieves high-precision prediction in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region through three parts: feature selection, adaptive hyperparameter optimization, and optimal base model combination. The specific research framework is shown in

Figure 1.

In the Feature Selection section, the Relief_F algorithm serves to assess input features quantitatively. This is achieved by computing the correlation weight between characteristics and the target variable, key pollutant indicators such as and , as well as meteorological features such as temperature and precipitation are selected.

In the Hyperparameter Optimization segment, the BAT algorithm is brought in to accomplish the hyperparameter optimization for the Relief_F algorithm. By emulating the echolocation behavior of bats, it makes dynamic adjustments and reaches the optimal solution after multiple iterations, thus addressing the issues of high subjectivity and restricted accuracy in conventional manual parameter tuning.

The third part centers on the Hybrid Neural Network. It builds a combined model of CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention. In this model, the CNN takes charge of extracting the local spatiotemporal features of pollutant concentrations; the BiLSTM and GRU work together to capture long-term and short-term temporal dependencies; and the Attention mechanism enhances the impact of crucial time steps and feature variables by allocating weights.

2.2. Definition of the Problem

This study aims to construct a data-driven air quality prediction model, which realizes the accurate prediction of concurrent air quality by learning historical data.

Let the input data be a time-series dataset containing multi-dimensional features, where represents the d-th dimensional original feature data at the ith time step. These features include six types of pollutants as well as the characteristics of temperature and precipitation. First, S is applied to decrease the original features, and a subset of key features that contribute to the prediction results is selected acquire the processed feature set , where is the screened feature data at the ith time step.

The output result is a set of time series air quality indexes

, where

specifically refers to the AQI at the

i-th time step. Through a series of data processing and feature learning operations

F, the model sets up a association between the screened features and the concurrent AQI values, that is:

Among these components, operation F encompasses core links like feature acquisition and temporal sequence correlation modeling of the deep learning network, feature weight allocation of the attention mechanism, and hyperparameter optimization. Combined with the previous feature screening step, the prediction accuracy of the features at the i-th time step for the concurrent AQI value is improved through multi-step collaboration.

2.3. Relief_F Feature Selection Method

Relief evaluates feature importance by calculating the ability of features to distinguish instances of different classes [

23]. It can effectively identify features related to the target variable, reduce redundant information, and improve model efficiency and generalizability.

The Relief_F algorithm is aimed to randomly select a sample R from the dataset, and then find its nearest neighbor sample

in the same class and

k nearest neighbor samples

in other classes. For each feature

A, its weight

is calculated as follows:

represents the distance between sample R and sample X in terms of feature A, and m is the size of the dataset. After multiple iterations, features with larger weights are considered more important for the classification or prediction task and thus are retained, while redundant features with smaller weights are eliminated.

2.4. BAT Hyperparameter Optimization Method

The BAT algorithm simulates the flight and hunting behavior of bats, has strong global search ability, and can automatically find the optimal hyperparameter combination of the model [

24]. Each bat represents a set of hyperparameters. Bats search the optimal solution space by adjusting their positions and velocities. The update formulas for the position and velocity of bats are:

Among them,

is the position of the

i-th bat at the

t-th iteration (corresponding to the hyperparameter combination),

is its velocity,

is the inertia weight,

is the position of the current global optimal solution, and

is the frequency of the

i-th bat. The calculation formula of

is:

Here, and are the minimum and maximum frequencies, respectively, and is a random number between .

In addition, bats also have the ability of random search and perform local search with a certain probability to prevent the algorithm from falling into local optimality. During the search process, the quality of each bat’s position is evaluated, and the global optimal solution is continuously refreshed.

2.5. Standard Deep Learning Model

In this model, the CNN, BiLSTM and GRU together form the core part of feature extraction and time-series modeling, and they work collaboratively to capture the beneficial details in the input data.

CNN has a key advantage in effectively extracting local data features. Through the convolution operation between the convolution kernels in the convolution layer and the input data, the perception of local region features is realized. Next, the down-sampling process of the pooling layer is employed to reduce data dimensionality, and ultimately, the fully connected layer is utilized for feature integration [

25]. The CNN has been employed in air pollution prediction and delivered high-performance prediction outcomes [

26]. In air quality prediction, CNN can be used to extract local correlation information between features such as different pollutant concentrations and meteorological factors. The mathematical expression of its convolution operation is:

Among them,

represents the output feature value at position

of the convolution layer

l-th,

is the weight of the convolution kernel of the

l-th layer,

are the input data at position

of the layer (

1)-th,

M and

N are the sizes of the convolution kernel, respectively, and

is the bias term. The mathematical expression of the average pooling operation of the pooling layer is:

Here, is the output of the l-th pooling layer at position (i, j), and S is the size of the pooling window.

BiLSTM is an extended form of the LSTM network, which consists of a forward LSTM and a backward LSTM [

27]. LSTM can effectively handle the long-term dependence problem in long-sequence data through three gating mechanisms: input gate, forget gate, and output gate [

28], avoiding the common gradient vanishing or explosion phenomenon in traditional Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). The mathematical formulas of its gating mechanisms are as follows:

Among them, is the sigmoid activation function, tanh is the hyperbolic tangent activation function, ⊙ represents element-wise multiplication, W is the weight matrix, b is the bias vector, is the input at the current time step, is the hidden state at the previous time step, and is the memory cell at the previous time step. On this basis, BiLSTM extracts information from both the forward and backward directions of the sequence, thereby more comprehensively capturing the bidirectional dependence relationship of the sequence data. Assuming that the output of the forward LSTM is and the output of the backward LSTM is , the final output of BiLSTM is , where represents vector concatenation.

GRU is a simplified recurrent neural network, which has a more concise structure than LSTM and only includes a reset gate and an update gate [

29]. Its mathematical expressions are:

However, the CNN, BiLSTM, and GRU models pay the same attention to all features or time steps during processing, making it difficult to highlight the key information. Thus, incorporating the attention mechanism to allocate distinct weights to different features and time steps can optimize the air quality prediction performance.

2.6. Attention Mechanism

The attention mechanism imitates the process of human attention concentration, and during the processing of sequence data, it is capable of assigning varying weights to information in different positions [

30]. In air quality prediction, by adding Attention after the GRU layer, the weights between different elements are calculated.

The attention mechanism mainly uses three vectors: Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V) for calculation. Assume that the input sequence is

, where

represents the GRU output feature vector at the

i-th time step. The Q, K, and V vectors are generated by multiplying with the learnable weight matrices

,

, and

, respectively. The calculation formulas are as follows:

The additive Attention mechanism can better handle input sequences of different lengths. The specific calculation formula is:

Among them, represents the attention score between the query at the i-th position and the key at the j-th position. , and v are learnable. The tanh function is used for non-linear transformation to enhance the model’s ability to express complex relationships.

Moreover, the softmax function is used to normalize the scores to obtain the attention weights

The attention weight represents the degree of attention paid to the j-th position by the i-th position, and .

Finally, the attention weights are used to generate the output representation of each time step through weighted summation:

Among them, is the final output of the i-th time step, which integrates the information of each position in the entire input sequence and focuses on the information highly relevant to the current position.

3. Experiment

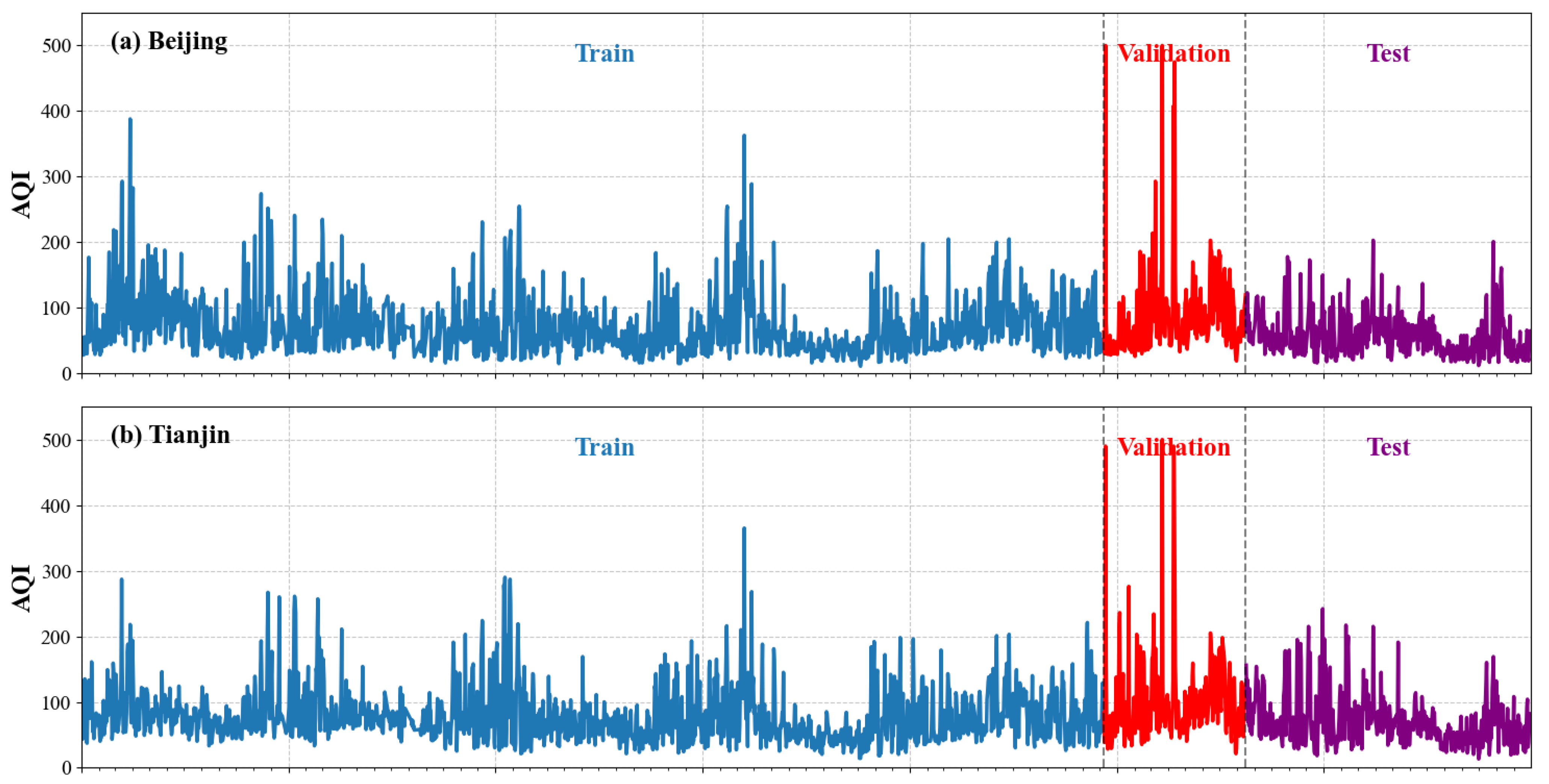

3.1. Dataset Description

In this study, the AQI is used as a comprehensive evaluation indicator for air pollution. Compared with traditional air pollution indices, this indicator not only covers a more comprehensive range of pollutant detection but also improves the objectivity of evaluation results through more stringent classification limit standards. To comprehensively investigate the temporal variation patterns of AQI and its influencing factors, this study collected daily average AQI data for three cities from 1 January 2018, to 31 December 2024, resulting in 2513 daily observations for each city. All data were obtained from

http://www.tianqihoubao.com. At the same time, to construct a more complete analytical framework, the study also obtained two types of key variables related to AQI from this website: one type is air pollution indicators, including

,

,

,

, CO, and

, which affect air quality through physical and chemical effects; the other type is environmental meteorological indicators, where temperature and precipitation indicators are selected to reflect the urban environmental meteorological conditions.

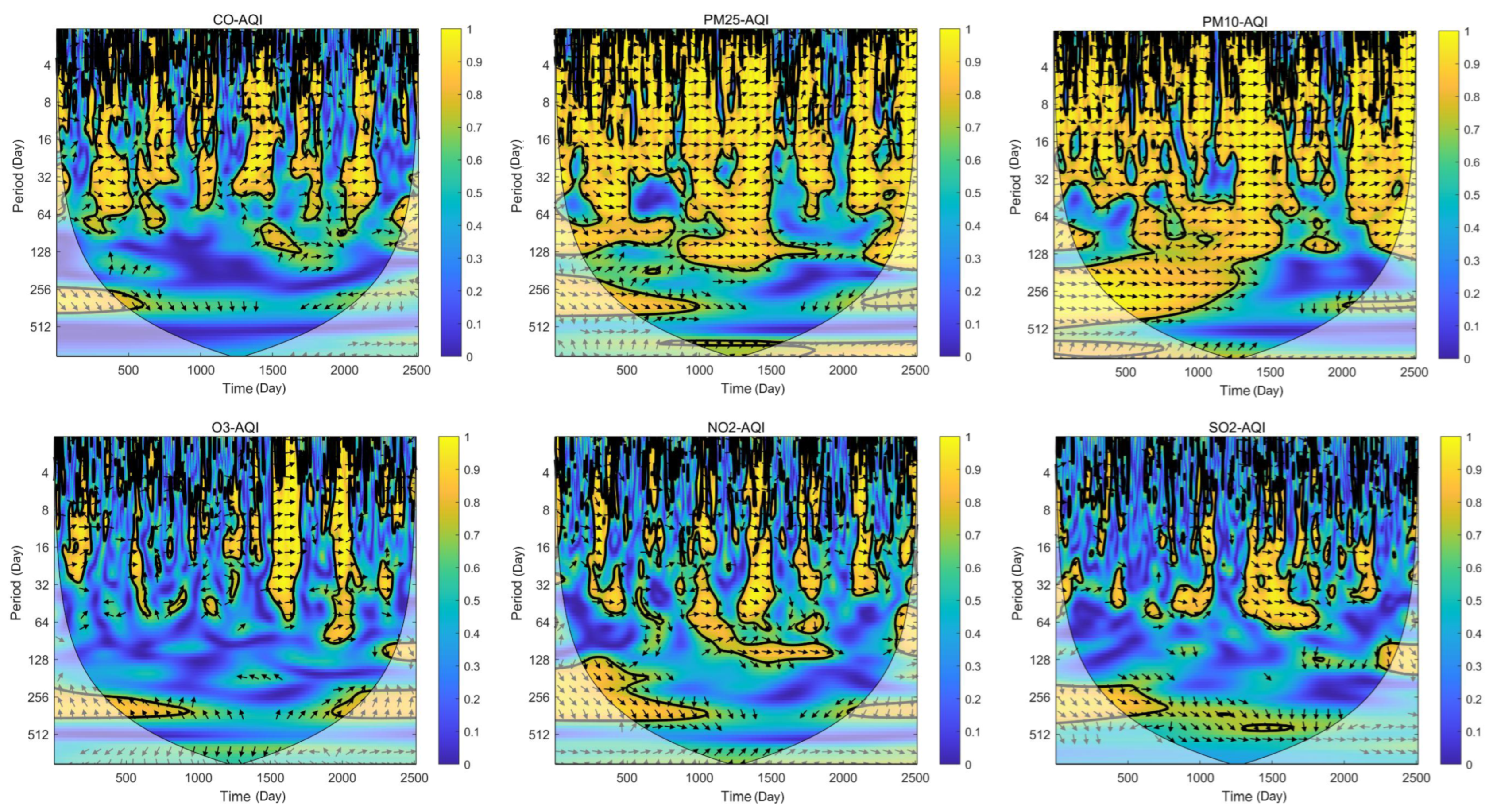

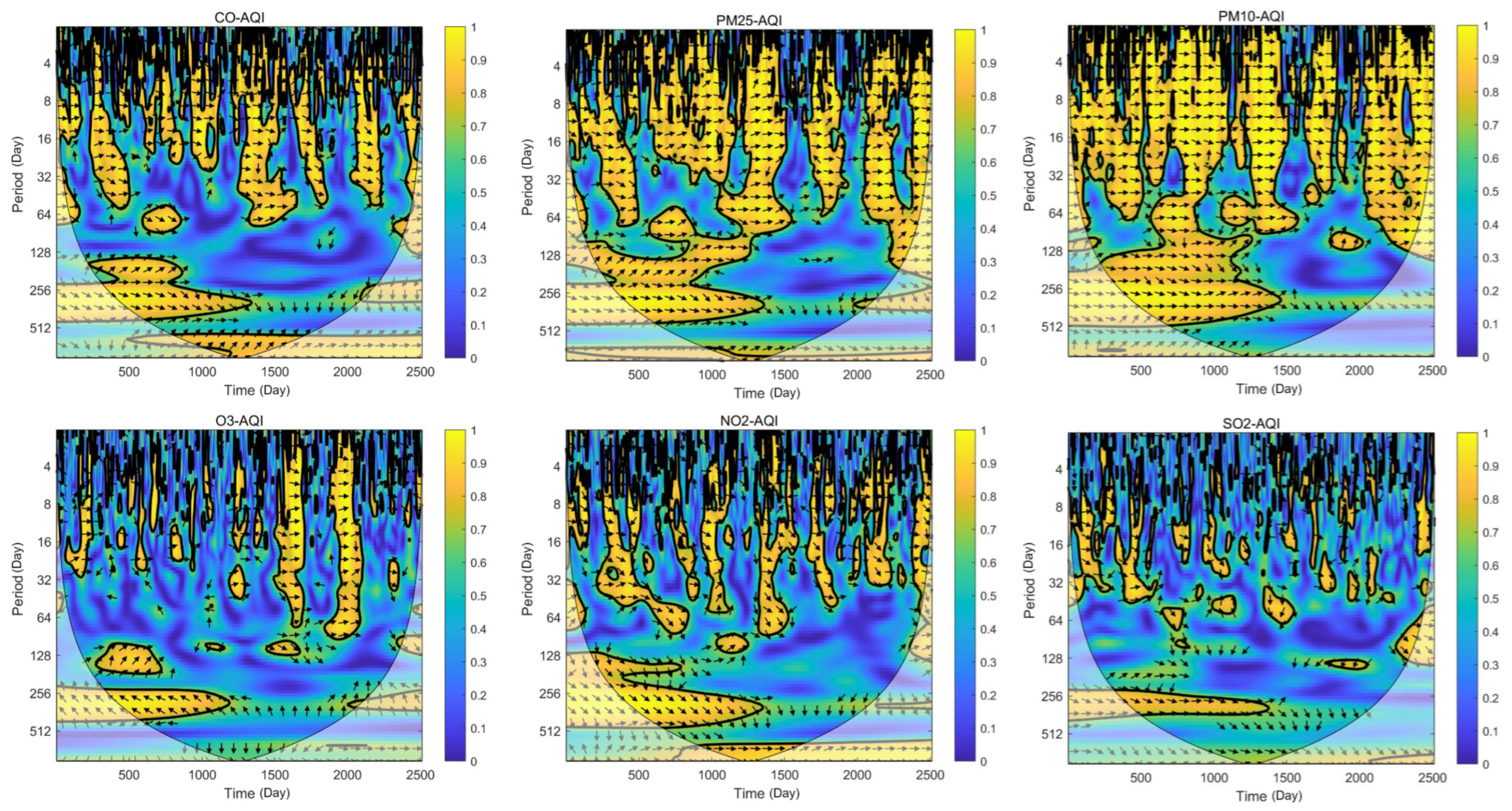

Considering the non-stationary characteristics of the AQI time series, the study introduced Wavelet Coherency (WTC) to explore the time-frequency correlation law between AQI and air pollutant indicators [

31]. This method combines the multi-scale analysis capability of wavelet transform with the idea of coherence analysis, which can quantify the covariance intensity of two time series and present the correlation and phase relationship of signals at different time and frequency scales.

The wavelet coherence results between AQI and air quality factors in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang are shown in the

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. Each point in the wavelet coherence image represents the coherence value at a specific time and scale. High coherence values in the image indicate strong signal synchronization; the direction of the arrows reflects the phase relationship, where horizontally to the right represents in-phase, to the left represents anti-phase, and the vertical direction reflects the sequence of factors and AQI. The closed solid line area represents passing the 5% significance level red noise test, and the area within the conical dashed line is the exclusion area.

The study divides the time-frequency scales into small time-frequency scales (frequency < 32 days), medium time-frequency scales (32 days < frequency < 128 days), and large time-frequency scales (frequency > 128 days), and conducts specific analyses for the three cities of Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang.

At the small time-frequency scale, the yellow and orange areas in the images are extensive, and pollutants in most regions generally show high coherence with AQI. For example, the AQI of the three cities shows in-phase positive coherence with CO, , and , while the yellow areas in the coherence images with , , and are small, indicating weak coherence.

At the medium time-frequency scale, the coherence distribution varies, and some pollutants in certain regions still maintain a certain degree of coherence in specific medium-to-long cycles. For instance, had a significant impact from 2022 to 2023, and showed annual periodic changes. The phase relationship between AQI and CO in the three cities is complex over time, and there is no significant coherence between AQI and .

At the large time-frequency scale, the AQI of Beijing shows negative coherence with , where lags behind AQI by approximately 1/4 of a cycle, and there is no coherence with CO. This also indicates that CO mainly affects the abrupt changes in air quality. The AQI of Beijing shows a relationship where other factors lead AQI when paired with all other factors. For Tianjin, the AQI shows a leading relationship with , , and , and a lagging relationship with . For Shijiazhuang, the relationship between AQI and is the same as that in Tianjin, and the AQI shows a leading relationship with CO, , and .

In summary, the AQI of each city shows strong coherence with and across all time-frequency scales. At small and medium time-frequency scales, the AQI has strong coherence with CO, indicating that changes in CO concentration have a rapid and significant impact on AQI in a short period, and pollution fluctuations are easily reflected in the air quality index quickly. In contrast, the large time-frequency scale reflects the continuous effect of processes such as regional pollution transmission and accumulation on AQI over a longer time scale.

3.2. Data Preparation

Step 1: Data Preprocessing

The step of AQI data cleaning is crucial to ensure the accuracy of the final results. First, identify the NaN values in the AQI data, temporarily store their positions, and remove samples containing NaN values to avoid interfering with calculations. Next, use the Hampel filter to process the time-series AQI data, where time is used as the X vector and AQI values as the Y vector. The filter automatically sets a reasonable window half-width and anomaly threshold: it detects AQI outliers that significantly deviate from the normal fluctuation range, then replaces these outliers with the median of the AQI data within the corresponding local window. Finally, reinsert the previously temporarily stored NaN values back into their original positions to complete the AQI data cleaning.

Step 2: Dataset Division

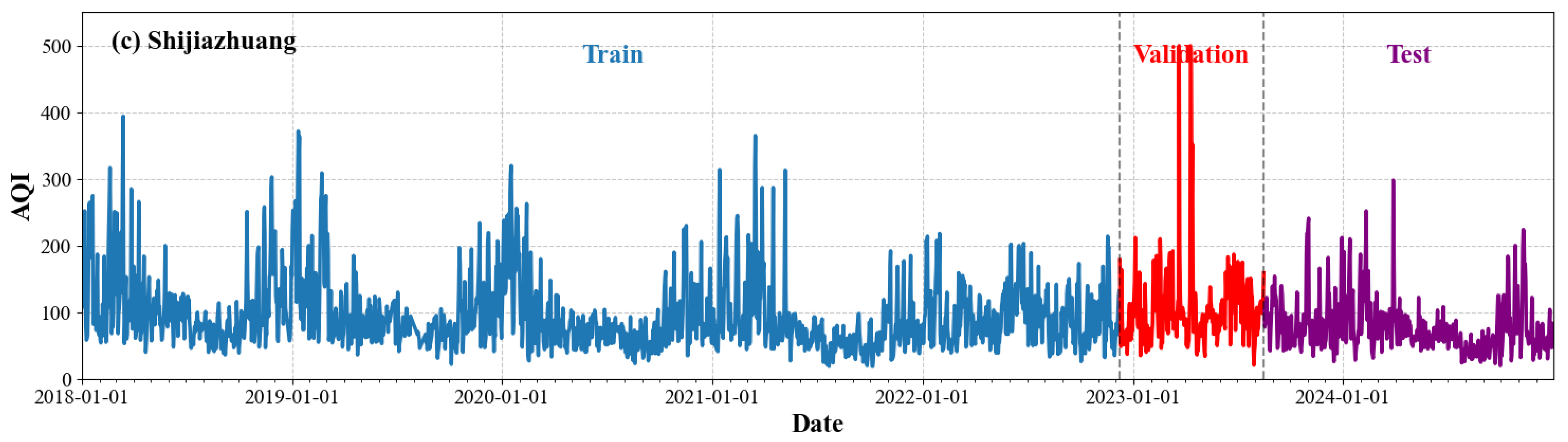

There are altogether 2513 samples in the original data. In this research, the data spanning from 2018 to 2024 is split into a training set, a validation set, and a test set with a proportion of 7:1:2 [

32]. The dataset division for Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang is presented in

Figure 5.

Step 3: Model Training

The AQI data, air pollution indicator data, and environmental meteorological indicator data are used as the input of the BAT-Relief_F-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention model. After training the model, it can predict the AQI data for multiple future time steps.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics and Experiment Design

3.3.1. Evaluation Metrics

This study constructs a system of five metrics, including Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), RMSE, Symmetric Directional Absolute Percentage Error (SDAPE), Direction Accuracy (DA) of prediction results, and Performance Parameter (PP). The specific calculation formulas and descriptions of each metric are as follows:

Among these symbols, ∑ denotes the summation operation, denotes the observed value or true value, denotes the predicted value, N denotes the number of samples, c denotes the city, and i denotes the time.

3.3.2. Experiment Design

This study introduces various types of benchmark models for comparative evaluation. First are statistical learning models, with the ARIMAX model specifically selected; second are machine learning models, with the XGBoost model chosen. In terms of neural network-related models, on the one hand, they include standard neural network models, specifically three types: GRU, LSTM, and BiLSTM; on the other hand, they also cover combined neural network models, with two combined models selected here: CNN-BiLSTM and CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention.

In addition, this study also introduces two types of prediction models related to feature selection as benchmarks. The first type is feature selection-prediction models, including four models: Grey-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention, Lasso-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention, Relief_F-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention, and Principal Component Analysis(PCA)-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention. Among them, “Grey” refers to feature selection implemented by calculating grey relational grade; “Lasso” completes feature selection by reducing the coefficients of unimportant features to zero. “Relief_F” uses the Relief_F model to calculate the distance between features and the similarity between instances, thereby evaluating feature importance and further screening out features with the strongest discriminative ability for classification. PCA retains as much information as possible by calculating the contribution rate and cumulative contribution rate of each factor.

The second type is algorithm-optimized feature selection-prediction models, specifically including three models: BAT-Relief_F-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention, GWO-Relief_F-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention, and DA-Relief_F-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention. Among them, the Bat-inspired Algorithm (BAT) simulates the flight and hunting behaviors of bats and has strong global search capability; the Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) simulates the leader-follower behaviors of grey wolf packs and has fast convergence speed and good local search capability; the Dragonfly Algorithm (DA) simulates the behaviors of dragonflies when searching for food and is a heuristic optimization algorithm based on bionics principles.

Next, the basic parameters of the model put forward in this study are discussed. To improve the reliability of the model results, the model was trained 10 times and the average value of the final prediction indicators was calculated. The specific parameters of the models are displayed in

Table 1.

4. Result Analysis

4.1. Comparison Results of Single Model with Multivariate Input

The results of the single model with multivariate input comparison experiment are shown in

Table 2. From the perspective of the comprehensive indicators of the three cities (Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang), the CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention model(CBGA) significantly outperforms other comparative models. This superiority stems from the hybrid network’s complementary advantages: CNN extracts local spatial features of multivariate input data, BiLSTM and GRU capture bidirectional and long-term temporal dependencies, respectively, and the integrated Attention mechanism emphasizes key information—together enhancing the model’s ability to mine complex AQI variation patterns. The proposed model integrates CNN for spatial feature extraction and BiLSTM-GRU for temporal dependency modeling, resulting in an 82.33% lower MAPE than XGBoost in Shijiazhuang. Its MAPE values in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang are 2.35%, 4.43%, and 2.12%, respectively, which are 9.26%, 10.51%, and 4.71% lower than those of the CNN-BiLSTM model. The traditional statistical model ARIMAX performs the worst, with a MAPE of 15.55% in Beijing, indicating that ARIMAX is not suitable. Although XGBoost outperforms ARIMAX, it is limited by the capacity of tree-based models to forecast air quality, and its MAPE in Shijiazhuang still reaches 6.17%, which is 2.9 times that of the proposed model.

The DA values of the CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention model all exceeded 0.95, and the P values all exceeded 0.5 in the air quality prediction tasks for three cities. This indicates that the model possesses a strong ability to judge the changing trends of air quality, demonstrating stable and excellent overall prediction performance.

4.2. Comparison Results of Feature Selection Methods

Four feature selection methods, namely PCA, Relief_F, Lasso, and Grey, were selected for comparison. In this process, the default threshold values were adopted for feature screening, and a threshold of 0.5 was used in this study. The results are shown in

Table 3. Compared with directly using all variables for prediction without feature selection, after implementing PCA, Lasso, and Grey feature selection, the prediction results were unstable. In some cases, the prediction accuracy improved, while in others, the prediction performance declined. This is because the default parameters used for feature selection fail to correctly identify the optimal features, thereby leading to the loss of important feature information.

Different from the CBGA model, the model screened by the Relief_F algorithm showed a significant improvement over other feature selection methods. Specifically, its MAPE values in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang decreased by 22.55%, 68.17%, and 32.55%, respectively, while its RMSE values decreased by 78.81%, 81.17%, and 74.03%, respectively.

4.3. Comparison Results of Adaptive Hyperparameter Optimization

The threshold of default parameters can cause the model to lose important feature information. Therefore, it is necessary to optimize this parameter. In this study, the BAT, GWO, and DA are selected to optimize the feature selection threshold of the Relief_F algorithm, thereby enabling it to select features that are more beneficial to the prediction results. The experimental results of adaptive hyperparameter optimization for the Relief-CNN-BiLSTM-GRU-Attention (RCBGA) model are shown in

Table 4.

Compared with the model without hyperparameter optimization, the model optimized by the BAT algorithm exhibited reduced errors: its MAPE values in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang decreased by 45.05%, 18.43%, and 23.77%, respectively, and its RMSE values decreased by 48.27%, 41.36%, and 62.82%, respectively. Among these, Shijiazhuang showed the largest reduction in RMSE, from 2.68 to 0.99. Additionally, the data in the table indicates that the error of the BAT algorithm after multiple rounds of parameter optimization is smaller than that of the GWO and DA algorithms. Therefore, in air quality prediction, the BAT algorithm also makes the model’s prediction performance more stable.

To more clearly depict the model fitting situation, this study selected the first 200 test set data points for demonstration. The forecast results are shown in the

Figure 6. As shown in the figure, the curves of Grey-CBGA and PCA-CBGA deviate significantly from the true values, indicating the poor performance of the Grey and PCA methods. In contrast, the Relief_F algorithm, when used as a feature selection method, achieved high prediction accuracy. After adopting the adaptive hyperparameter optimization method, the fitting degree of the model was further improved. Among these methods, the BAT algorithm showed the best performance in improving prediction accuracy and also exhibited the optimal fitting effect.

It can thus be concluded that the Relief_F algorithm is based on an iterative update mechanism of feature weights: it quantifies the correlation strength between features and AQI by calculating the differential contribution of each feature between samples of the same class and different classes, thereby determining the contribution degree of each influencing factor to air quality prediction. The BAT algorithm, on the other hand, is based on a bionic optimization mechanism simulating bat echolocation: by simulating the behavior of bats emitting sound waves and receiving echoes, it dynamically adjusts the search strategy using parameters such as pulse frequency and loudness to achieve adaptive optimization of the Relief_F feature selection threshold. Under the synergistic effect of the two algorithms, not only does Relief_F not need to rely on assumptions about the probability distribution of data, but the BAT algorithm also reduces the errors caused by manual selection of feature selection thresholds.

4.4. Robustness Test

The robustness test evaluates the anti-interference by modifying the input air quality data and verifying whether the prediction results remain accurate after adding disturbances to the input data. In this study, disturbances of 5%, 7%, and 10% were added to the input data of the test set, and the network structure obtained from the original training set was still used for prediction.

The results of the noise disturbance verification are shown in

Table 5. With the increase in disturbance intensity, although the model error indicators fluctuated slightly, they always remained at a low level. In Beijing, the MAPE values under 5% and 7% disturbances were 0.91% and 0.91%, respectively; although the RMSE increased from 1.95 to 2.72 under 5% disturbance, it dropped back to 2.36 under 7% disturbance, and the DA value remained stable at around 0.96. In Tianjin, the MAPE under 10% disturbance was 1.73%, which was only 0.58% higher than that without disturbance, and the DA value remained above 0.95. In Shijiazhuang, the MAPE increased to 3.63% and the RMSE increased to 2.72 under 10% disturbance; this may be related to Shijiazhuang being an industrial city, where pollutant sources are more complex and concentration fluctuations are more intense. Even so, its DA value under 10% disturbance was still 0.93, indicating that the model still has reliable judgment on the changing trend of pollution. Overall, the model can maintain stable prediction performance when there is a certain degree of noise or fluctuation in the data, meeting the requirement for the model’s anti-interference ability in practical air quality early warning.

4.5. DM Test

The DM test is primarily employed to quantitatively compare the performance of various models. It leverages statistical approaches to ascertain if there are notable discrepancies in the errors of multiple models during AQI prediction, so as to steer clear of judgment biases stemming from relying purely on subjective error value comparison [

30]. The DM test makes use of three indicators—MAPE, MSE, and Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD)—to validate the prediction efficiency of the models. The outcomes are presented in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8.

The null hypothesis of the DM test is that the prediction efficiency of the two models is identical, that is, the average values of their loss sequences are the same. The alternative hypothesis is that the prediction efficiency of the two models differs. When the DM value exceeds 0, it indicates that the prediction effect of Model 2 is superior to that of Model 1. In this research, Model 1 was designated as other benchmark models, and Model 2 was designated as the model put forward in this paper.

Based on the DM test results, under all three evaluation indicators, the DM statistics of the proposed model in contrast to each benchmark model were notably larger than 0, and all p-values were below 0.05. This shows that at the statistical significance level, the null hypothesis stating “no difference in prediction efficiency between the two types of models” can be rejected, verifying that the proposed model has higher prediction accuracy. Its superiority is not due to random factors but reflects a statistically significant enhancement.

5. Conclusions

High-precision air quality prediction is not only a key support for coordinated regional pollution control, but also an important prerequisite for ensuring the health and travel safety of the public. Addressing the demand for high-precision air quality prediction in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, this study combines feature selection, hyperparameter optimization, and a hybrid neural network. First, the Relief_F algorithm is used to screen key features. Then, the BAT algorithm is employed for adaptive optimization of the feature selection threshold of Relief_F. Finally, a Hybrid Neural Network is constructed to capture spatiotemporal features and temporal dependencies. The core innovation lies in integrating an attention mechanism into the hybrid neural network, while further improving the model performance through the coordination of feature selection and hyperparameter optimization. The experimental findings demonstrate that this approach is remarkably better than ARIMAX, XGBoost, and individual deep learning models. The MAPE in Beijing, Tianjin, and Shijiazhuang is as low as 1.00–1.15%, which is 18.43–45.05% lower than that of the unoptimized hybrid neural network. Moreover, robustness tests and DM tests confirm that the proposed method has strong anti-interference ability and good statistical significance, and can effectively handle the nonlinear and non-stationary characteristics of air quality data.

To broaden the application scope of the proposed framework, future research could integrate temperature and other environmental variables to establish a combined evaluation network for air pollution and heat exposure, drawing on studies that have validated the nonlinear impacts of urban morphology on microclimate and thermal environment [

33,

34]. Additionally, incorporating multi-source data such as ground monitoring, satellite observations, and meteorological reanalysis can further enhance the spatial/temporal resolution of the evaluation, as demonstrated in relevant urban environmental assessment studies. Such extensions would provide more comprehensive decision support for low-carbon urban planning and public health risk management.