Abstract

This paper presents a mathematical model that describes the propagation of internal inertia–gravity waves in a stratified atmosphere under the approximations of an incompressible fluid and a traditional β-plane. It demonstrates that, in the incompressible fluid approximation, the temperature field is inconsistent with the heat conduction equation. The system of equations that describes internal inertia–gravity waves is considered in the general case, taking into account the buoyancy force, and reduced to a single equation. The solution is sought in the form of traveling plane waves. A dispersion relation has been obtained in the form of a cubic equation that represents a hypersurface in wave number space, without the assumption of small vertical wavelength. Cross-sections of this surface are plotted, and an extremum study is performed. This shows that a new frequency region appears in the low-frequency spectrum that was not present in the f-plane approximation. Here, is the Coriolis parameter, and is the latitude. Furthermore, these waves only propagate in the negative direction of the x-axis, i.e., in the opposite direction of the Earth’s rotation. It is also shown that there is a region with a minimum frequency in the “high-frequency” spectrum determined by buoyancy , and that waves propagate in the negative direction as well. Thus, the dispersion surface is shown to have two extremum points. The first is a minimum in the “high-frequency” spectrum and the second is a maximum in the “low-frequency” spectrum .

1. Introduction

Many studies have been devoted to internal gravity waves (IGWs). However, as noted in [], prior to [], IGWs were considered to be somewhat exotic phenomena. Interest in IGWs increased precisely with the classic work [], which showed that IGWs can be observed in the atmosphere and are responsible for wind disturbances in its upper layers. In [], waves of a non-planetary scale are considered, i.e., without taking the Coriolis force into account. According to [], IGWs are not just noise in the atmosphere; they play an important role, if not the main role, in large-scale atmospheric circulation. IGWs carry the energy of disturbances from one point on the planet to another. For example, we refer to [], which explains the slowing of average zonal flows with height by interaction with internal gravity waves. According to [], the three main sources of internal gravity waves are topography, thermal convection and zonal wind shear. Observations have shown that jet streams and fronts are also important sources of internal gravity waves in the atmosphere [].

The studies in [,,] consider planetary-scale waves using the traditional f-plane approximation, i.e., without considering the horizontal component of the Coriolis force. In this case, the Coriolis parameter is considered constant; here is the angular velocity of the Earth’s rotation, is the latitude. This paper presents a mathematical model that describes the propagation of internal inertia–gravity waves (IIGWs) in a stratified atmosphere using the approximations of an incompressible fluid and a β-plane. The beta plane is the plane tangent to the Earth’s surface on which the Coriolis parameter varies linearly along the meridian. The model is examined in terms of its consistency with the heat conduction equation.

In [], it was shown that three approximations are currently used to describe non-planetary scale waves: the incompressible fluid approximation, the compressible fluid approximation, and the anelastic gas approximation. Of these three approximations, only the compressible fluid approximation agrees with the heat conduction equation. In the other two approximations, the temperature field does not agree with the heat conduction equation. In other words, in the incompressible fluid and in the anelastic gas approximations, the temperature field is not found from the heat conduction equation, but from the Boussinesq relation. According to this relation, the temperature disturbance is directly proportional to the density disturbance.

Note that, when analyzing the system of equations that describes the IIGWs, we will assume that the atmosphere is homogeneously stratified, i.e., that the vertical temperature gradient is constant, which is equivalent to assuming that the buoyancy frequency does not depend on the vertical coordinate. In the case of heterogeneous stratification, however, the problem must be solved using numerical or asymptotic methods [].

In [], it was demonstrated that the problem of temperature field inconsistency with the heat conduction equation also occurs for planetary-scale waves in the traditional f-plane approximation. In this paper, we examine planetary-scale waves within the β-plane approximation. Furthermore, the incompressible fluid approximation is the sole consideration in this study. In the context of the β-plane approximation, the buoyancy force is typically neglected [,,]. This is because the β-effect only manifests itself at frequencies much lower than the buoyancy frequency for an incompressible fluid. However, as will be demonstrated in this article, incorporating buoyancy effects into the analysis provides a richer picture of the IIGW spectrum, resulting in the emergence of additional maxima and minima in the frequency spectrum. Therefore, in this study, we comprehensively analyze the dispersion relation, incorporating the effects of buoyancy forces. The dispersion relation is generally understood to be a hypersurface in the space of three projections of the wave vector. Consequently, the problem is reduced to analyzing this surface, studying its maximum and minimum values.

It should be noted that the studies in [,,] consider mathematical models describing the propagation of IIGWs in a stratified atmosphere in a non-traditional β-plane. However, these models also do not take buoyancy forces into account.

The objective of this article is to conduct a comprehensive analysis of the dispersion relation of the IIGW model in the approximations of an incompressible fluid and a traditional β-plane, taking buoyancy into account and without assuming a small vertical wavelength.

The structure of the article will be as follows. In Section 2, the basic equations are presented. In Section 2.1, we examine the mathematical model of IIGWs in the incompressible fluid approximation. In Section 2.2, an analysis of the dispersion relation is conducted. The primary outcomes are delineated in Section 3. Section 4 is devoted to a discussion of the results obtained. Section 5 offers a synopsis of the key points and formulates conclusions.

2. Mathematical Model of IIGWs in the Incompressible Fluid Approximation

2.1. Basic Equations

The system of equations describing the dynamics of a disturbed atmosphere without background wind is written as [,]:

Here is the velocity vector; is the acceleration due to gravity (acceleration of free fall); , , are the disturbances of pressure, air density, and temperature, respectively; is the angular velocity modulus of the Earth’s rotation; is the vertical temperature gradient in a static atmosphere, equal to for a standard atmosphere; , are the air density and temperature in a static atmosphere; is the vertical component of air velocity; is the characteristic scale of atmospheric height. Here we used the approximation , .

Taking the substantial derivative from the last expression, taking into account (2) and (3), we reduce it to the form

Here is the speed of sound square, which is assumed to be equal to 330 m/s in calculations.

That is, in general, the system is described by six variables (, , , , , ) and six equations for each variable. In linearized form and without background wind, the system of equations has the following form:

In the Boussinesq approximation [], it is assumed that in expression (4) we can set , then

where is the thermal expansion coefficient, . For the atmosphere .

In the incompressible fluid approximation, the continuity equation splits into two equations. The first equation expresses that the substantial time derivative of air density is equal to zero. The second equation expresses the equality of velocity divergence to zero. In other words, the equation of state of a moving air parcel is assumed to be constancy of its density [,]. The heat conduction equation is not included in the system of equations describing IIGWs in the incompressible fluid approximation. It is assumed that the Boussinesq relation between density and temperature disturbances is satisfied.

The system of linearized equations for an incompressible fluid in the traditional approximation () is expressed in general form in projections on the coordinate axes as follows []:

The coordinate axes are chosen in the standard way: the origin is on the Earth’s surface, the x-axis is directed along a parallel with a positive direction in the direction of the Earth’s rotation, the y-axis is directed along a meridian with a positive direction to the north, and the z-axis is perpendicular to the Earth’s surface with a positive direction upward, away from the Earth’s surface. The reference system rotates with the Earth.

For the distribution of air density with height in a static atmosphere, we obtain

The value , as it appears in expression (18) for the distribution of air density in a static state, is considered to be the characteristic thickness of the stratified atmosphere. Here, is the so-called autoconvection gradient, which coincides with the temperature gradient of an atmosphere with uniform density; is the specific gas constant of dry air. In calculations for a standard atmosphere, the scale height is assumed to be equal to .

Note that in the incompressible fluid approximation, the equations for density disturbance and temperature disturbance ((15) and (16)) are not consistent with Boussinesq’s relation (10). In other words, in the incompressible fluid approximation, the temperature disturbance field, if determined from the heat conduction equation, is not consistent with the density disturbance field, as it should be according to Boussinesq’s relation (10). Therefore, in the incompressible fluid approximation, the temperature disturbance field is found not from the prognostic heat conduction Equation (16), but from the diagnostic relation (10) [].

Let us denote the Coriolis parameter as . For the 45th parallel . Thus, in the incompressible fluid approximation, the system of equations describing the IIGWs in the traditional approximation has the following form:

Equation (22) expresses the equation of state for an incompressible fluid : the density of an air parcel does not change during motion. In other words, the change in air density disturbance is opposite to the change in background air density []. Equation (22) is also the equation for buoyancy force if multiplied on both sides by the acceleration due to gravity.

Now we will take into account that the Coriolis parameter is not a constant value, but varies along the meridian . Moreover,

where is the Earth’s radius. For the 45th parallel .

Hence

This approximation is valid for . This distance along the meridian is a constraint for the β-plane.

The system of Equations (19)–(23), taking into account (25), reduces to a single equation. To do this, we exclude the pressure disturbance by cross-differentiating (19) and (20):

where the designation of vorticity is introduced

The divergence of the equation of motion is given by the following equation:

Taking the derivative with respect to x of the equation for and taking the derivative with respect to y of the equation for , and then summing them, yields another equation

So, we have a system of Equations (26), (28) and (29). Let us exclude the density disturbance from (22). Then, taking into account (25), Equations (28) and (29) can be written as

where is the buoyancy frequency in the incompressible fluid approximation, for a standard atmosphere . In real atmospheric conditions, the buoyancy frequency assumes real values, although it formally becomes imaginary at . Excluding we obtain

Thus, we have expressed the pressure disturbance through the vertical velocity. This allows us to exclude the pressure disturbance from the equations of motion. To do this, it is sufficient to multiply them by .

For we obtain

Similarly, for

So, instead of two horizontal equations of motion, we obtain system (33) and (34). From this, we express in terms of vertical velocity

and, similarly,

Thus, we have expressed the horizontal projections of velocity in terms of vertical velocity.

Let us substitute the resulting equations into the expression for divergence, after taking the operator . We obtain

where are the variables determining the state of the system in the incompressible fluid approximation; is the Laplacian; is the “horizontal” Laplacian. Thus, Equation (37) describes IIGWs in the approximations of an incompressible fluid and a traditional β-plane.

The solution is sought in the form of plane waves:

where are the components of the vector ; is the amplitude of the corresponding quantities included in . We assume that the wave numbers , , are complex in general.

The presence of the first derivative with respect to the vertical variable in Equation (37) will lead to the appearance of an imaginary part in the dispersion relation:

The standard procedure for representing the vertical component of the wave vector as the sum of the real and imaginary parts: , , yields the condition under which the oscillation frequency becomes real (see, for example, []):

The dispersion relation is obtained as follows:

here .

In dimensionless form:

where , , , , , . For the 45th parallel , .

From (42) it can be seen that there are two parameters that determine the dispersion relation: , .

2.2. Analysis of the Dispersion Relation

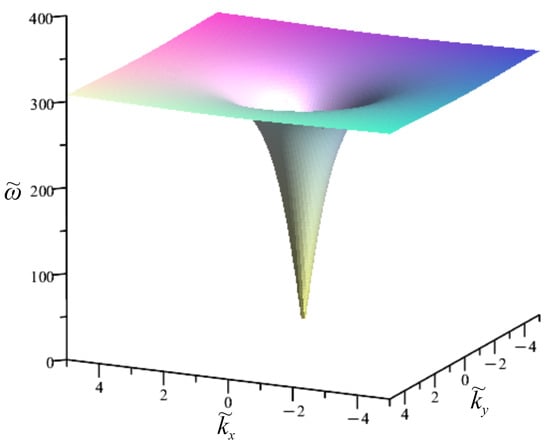

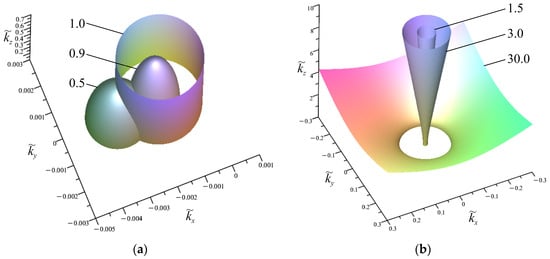

To plot the dispersion relation, assume and plot the surface (Figure 1). For the purpose of comparison, a similar graph in the f-plane approximation in the absence of the β-effect (see Appendix A) is presented in Figure 2. In the absence of the β-effect, the frequencies are confined between the inertial frequency and the buoyancy frequency .

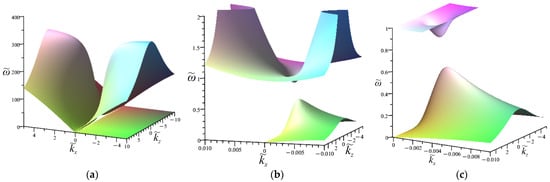

Figure 1.

Surface plot of according to Equation (42). (a) The formula and figure show that when and the oscillation frequency tends to the buoyancy frequency . (b) Low frequency region . (c) In the “high-frequency” spectrum (upper part of the figure), there is a region with a minimum frequency of waves that also propagate in the negative direction.

Figure 2.

Surface plot of according to Equation (42) in the f-plane approximation (in the absence of beta-effect).

Note that the graphs differ in the low-frequency range (long-wave range). Therefore, Figure 1b shows the low-frequency range separately. Note that a new frequency range appears in the low-frequency spectrum , which was not present in the f-plane approximation. Moreover, as can be seen from Figure 1b, these waves propagate only in the negative direction of the x-axis, i.e., against the direction of the Earth’s rotation. We also note that in the “high-frequency” spectrum (upper part of Figure 1b) there is a region with a minimum frequency , with which the waves also propagate in the negative direction. To make this clearer, we show this region in a separate Figure 1c.

The calculations in the figures were performed for the 45th parallel, where . From Formula (42) and Figure 1, it follows that when (short horizontal waves), two regions arise, and . When , (waves propagate strictly vertically) .

Using the standard method for finding the extremum of an implicitly defined function, let us find the extremum of the function . We obtain the following system of equations:

Here, we have denoted by the partial derivative of function with respect to variable . We will write this system as:

From here, we can identify the critical points, which are the points at which the derivative of the function is zero. However, the function does not necessarily have an extremum at every critical point:

At the critical point, the function takes the following values:

Given that (for standard atmosphere ), let us write (50) as

From (48) we find

So, we have obtained two extremum points (points where the function reaches its maximum or minimum value):

Let us show that the first extremum is a minimum and the second is a maximum. To accomplish this, we will determine the following:

From here we get

It follows (Sylvester’s criterion) that the first extremum is a minimum and the second is a maximum.

Thus, the β-effect causes the spectrum in the low-frequency range to split into two non-intersecting groups of waves: (1) with minimum frequency and (2) with maximum frequency .

Thus, we see that in the low-frequency region there is a range of frequencies at which IIGWs do not propagate in the negative direction. This result is of practical importance in the analysis of large-scale atmospheric circulation. A possible physical manifestation of the beta-effect is the inhibition of zonal flow. However, the presence of the above-mentioned “gap” in the frequency spectrum leads to a range of frequencies at which zonal flow inhibition does not occur.

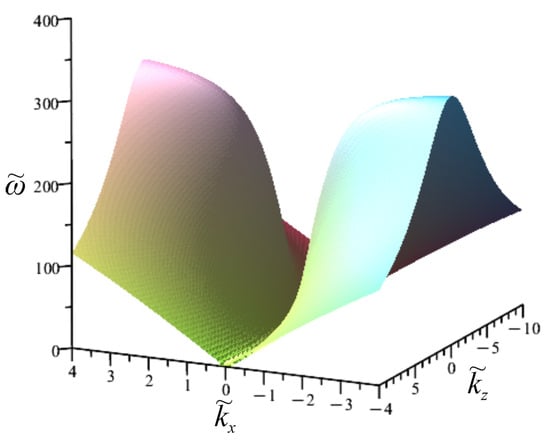

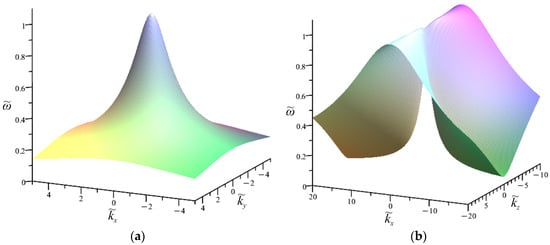

Let us also show the surface graph (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

(a) Surface plot of according to Equation (42). (b) The same as (a) for .

A comparison of Figure 1 and Figure 3 shows that there is asymmetry in the direction of wave propagation along the x and y axes. The β-effect influences wave propagation along the parallel. Separately, we will demonstrate the low-frequency region for the surface (Figure 3b). As can be seen from Figure 3b, for the surface , the minimum frequency is the inertial frequency .

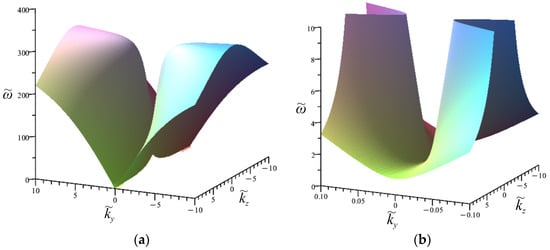

Figure 4 shows the graph of function . For comparison, let us show a similar graph for the f-plane approximation (Figure 5). The f-plane is defined as the plane tangent to the Earth’s surface on which the Coriolis parameter does not change along the meridian. A comparison of Figure 4 and Figure 5 shows that the β-effect manifests itself in the low-frequency range. Therefore, this range is shown separately in Figure 4b. Figure 4b shows that the “high-frequency” spectrum (the upper surface in Figure 4b) begins at the minimum frequency , while the low-frequency spectrum describes waves propagating in the negative direction of the x-axis (along the y-axis waves propagate in both directions) with a maximum frequency less than .

Figure 4.

(a) Surface plot of according to Equation (42). (b) The same as (a) for , .

Figure 5.

Surface plot of in the f-plane approximation according to Equation (42).

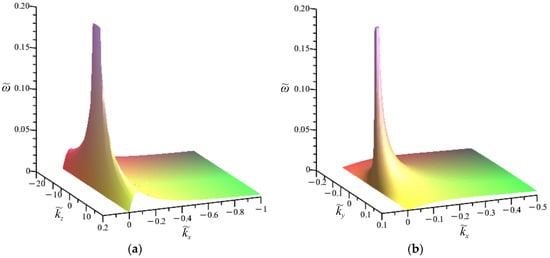

When modeling large-scale atmospheric circulation, buoyancy is sometimes neglected and air density is considered constant. Motion is also considered only in the horizontal plane since buoyancy causes vertical motion. Note that without taking buoyancy into account, the surface pattern changes significantly (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

(a) Surface plot of (low frequency region) without buoyancy according to Equation (42). (b) The same as (a) for .

In the absence of buoyancy, there is no asymmetry in the direction of the x-axis in the graph. The situation is similar for the graph (Figure 6b).

Let us find the extrema of the function in the general case. Using the standard method, we obtain a system of equations:

Note that Equations (60) and (62) coincide with Equations (43) and (45), respectively, if we make the substitution . Equations (44) and (61) differ in their numerators. The system (60)–(62) is to be written as follows:

From here, we can find the critical point:

At the critical point, the function takes values coinciding with (50), which can be represented as (51). Condition (53) also holds.

Thus, we have two extremum points:

Similarly to the case of surface , the first extremum will be a minimum, and the second extremum will be a maximum.

The dispersion ratio (42) can be conveniently written as:

Let us bring it to canonical form:

where

We obtain

To determine the sign of , let us set the terms with to zero, and we obtain

In our case , which means we have three real roots:

Returning to the original variable, we write

This expression includes all three components that determine the dispersion relation. The first term under the square root is due to buoyancy forces and describes oscillations with a buoyancy frequency for an incompressible fluid. The second term under the square root is due to the Coriolis inertia force component and describes inertial oscillations with a frequency . The term outside the square root describes oscillations caused by the β-effect. From the dispersion relation (42), it follows that at , the maximum frequency of the IIGWs is equal to the Coriolis parameter . Dispersion relations (81) and (82) express a peculiarity of the dispersion of the IIGWs, namely that the wave frequency depends not only on the wavelength but also on the direction of propagation. Strictly vertical waves can propagate only at the inertial frequency, and as the angle of inclination to the horizon decreases, the wave frequency increases and, in the horizontal direction, tends to the buoyancy frequency.

The procedure of representing the vertical component of the wave vector as the sum of the real and imaginary parts leads to the wave amplitude increasing with height:

Thus, the incompressible fluid approximation can explain the inhomogeneities observed in the upper atmosphere through wave breaking. The increase in wave amplitude with height, according to [], is explained by the fact that the density of air in a static state decreases with height. Recall that in [] and subsequent studies, the breaking of the IGWs explains the periodic structures observed in the upper atmosphere (mesosphere, ionosphere, at heights of about 80–100 km) in the form of velocity field disturbances.

Note that when deriving system (19)–(23), no assumption was made about the thickness of the fluid layer in which the waves propagate being small compared to the characteristic atmospheric height scale . Thus, the results obtained are extended to the upper atmosphere. The main assumption of this approximation is that disturbances are small compared to the values in the static state, and that the parameters used (e.g., atmospheric composition and vertical temperature gradient ) are constant. It is also assumed that wave breaking occurs at amplitudes that are still much smaller than those in a static state.

With the additional “assumption of a small vertical wavelength” [,], the second term with the multiplier on the right-hand side of (21) can be neglected. This eliminates the fourth term in Equation (37). This means that the imaginary unit does not appear in the dispersion relation, and the wave amplitude does not increase with height. In this case, the term with disappears from the dispersion relation:

Thus, we see that the increase in wave amplitude with height is not necessarily a consequence of the decrease in air density with height in a static state, as is commonly believed [,].

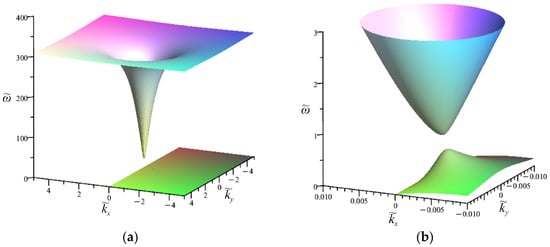

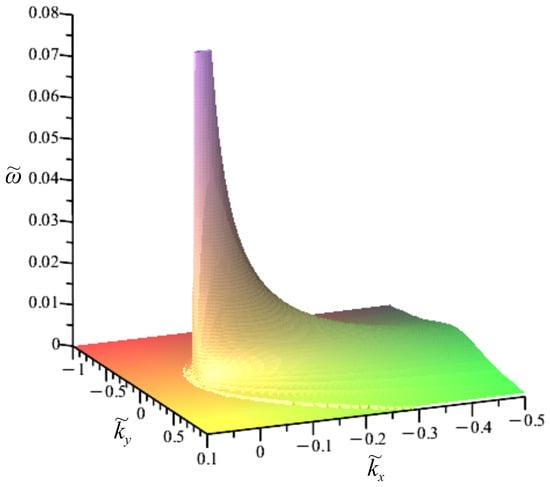

In the literature, the β-plane approximation is often considered precisely under the assumption of a small vertical wavelength []. Figure 7 shows the graphs of the surfaces and according to Formula (84). The figure shows the manifestation of the beta effect, i.e., the waves propagate only in the negative direction of the x-axis.

Figure 7.

Surface plot of (a) and (b) under the assumption of a small vertical wavelength according to Equation (84).

We also present a graph of the surface assuming a small vertical wavelength and no buoyancy (Figure 8). A comparison with Figure 6a suggests that the absence of buoyancy does not necessarily result in the manifestation of the β-effect. The β-effect only manifests itself when both a small vertical wavelength and the absence of buoyancy are assumed. Therefore, in order to study the influence of buoyancy on the manifestation of the β-effect, it is necessary to analyze the complete dispersion relation. Taking buoyancy into account and rejecting the assumption of a small vertical wavelength provides a more comprehensive view of the dispersion relation. Particularly, there are two non-overlapping wave spectra (Figure 4) propagating in the negative direction of the x-axis.

Figure 8.

Surface plot of without buoyancy and under the assumption of a small vertical wavelength according to Equation (84).

Thus, in the approximation of an incompressible fluid without assuming a small vertical wavelength, the dispersion relation has the form (42), the wave amplitude increases with height, and the buoyancy frequency is equal to (see Appendix B). Assuming small amplitudes (with short vertical wavelengths), the dispersion relation is given by Formula (84), and the wave amplitude does not increase with height. It also follows from (42) that only inertial waves with frequency can be strictly vertical.

In the incompressible fluid approximation in the absence of buoyancy forces, the maximum oscillation frequency will be determined by the components of the Coriolis inertia force, i.e., inertial oscillations will occur. However, the presence of buoyancy forces will lead to oscillations with a maximum frequency equal to .

In the considered case, in the incompressible fluid approximation, the heat conduction equation is not included in the system of equations, since it is assumed that the relationship holds, i.e., the density perturbation is proportional to the temperature perturbation. This relationship is called the Boussinesq approximation, which is understood as the assumption that the pressure disturbance is zero in the equation of state of the disturbed atmosphere, but not zero in the equation of motion. This leads to the fact that in the incompressible fluid approximation, the temperature field is not consistent with the temperature field obtained from the heat conduction equation. Therefore, the following task arises for further research: to propose a mathematical model of IIGWs such that the temperature field is consistent with the heat conduction equation. We proposed such a model in [,] for non-planetary scale waves and waves in the f-plane approximation, where it is shown that taking into account the heat conduction equation leads to a quantitatively and qualitatively new dispersion relation in the anelastic gas approximation, while in the incompressible fluid and compressible fluid approximations, the dispersion relations remain unchanged.

3. Results

Thus, the system of equations describing the propagation of IIGWs in a stratified atmosphere, in the incompressible fluid and traditional β-plane approximations, is reduced to a single Equation (37). Solving this equation in the form of plane traveling waves leads to the dispersion relation (42), which is a hypersurface in wave number space. From the validity condition (40) of the dispersion relation (39), it follows that the amplitude of the IIGWs increases with height. The incompressible fluid approximation explains the inhomogeneities observed in the upper atmosphere by wave breaking. Moreover, this is true not only for non-planetary scale waves, i.e., waves with a maximum frequency equal to the buoyancy frequency in the incompressible fluid approximation, but also for planetary scale waves in the traditional f-plane approximation, which gives a lower spectrum limit equal to the inertial frequency. As shown in this work, the traditional β-plane approximation also leads to an increase in the amplitude of the IIGWs with height.

Analysis of the dispersion relation showed that the beta effect leads to the spectrum being divided into two non-intersecting groups of waves in the low-frequency region : (1) with a minimum frequency and (2) with a maximum frequency .

Analysis of the dispersion relation shows that there is asymmetry in the direction of the waves along the x and y axes. The β-effect affects the propagation of waves along the parallel. From the dispersion relation (42), it follows that at , the maximum frequency of the IIGWs is equal to the Coriolis parameter .

The following presentation of graphs of frequency isosurfaces in wave number space is made according to the dispersion relation (42) (Figure 9). Figure 9 shows that there is a beta-effect in the direction of the x-axis and that each specific frequency corresponds to a specific family of wave numbers.

Figure 9.

Frequency isosurfaces in wave number space according to the dispersion relation (42). (a) . (b) .

It should be noted that, formally, the dispersion relation (42) does not impose any restrictions on the values of the wave numbers . The only restriction is that the frequency can only take real values. This is equivalent to assuming that the size of the beta plane is unlimited, while along the meridian there is a restriction, as indicated above (). Similarly, we assume that the atmosphere extends vertically without limitation with homogeneous stratification, i.e., with unchanged parameters, which is, of course, an idealization. Such an idealization is generally considered acceptable [].

4. Discussion

Thus, we have considered a mathematical model describing internal inertia–gravity waves in a stratified atmosphere in the traditional β-plane approximation. Moreover, we have considered the incompressible fluid approximation. The state of the fluid is determined by five variables . In this approximation, the density of the air remains constant during motion. This leads to the fact that the density perturbation is opposite to the change in density in the surrounding atmosphere (in a static state). In other words, there is a position (height) of equilibrium at which the density of the moving air parcel coincides with the density of the surrounding air. Since in this approximation the density of the moving air parcel remains constant, when moving upward relative to the equilibrium position, the density of the air parcel becomes greater than the density of the surrounding air. And when moving downward relative to the equilibrium position, the density of the moving air parcel is less than the density of the surrounding environment. Thus, when deviating from the equilibrium position, a restoring force arises, which leads to oscillations, which in turn generate waves.

In the incompressible fluid approximation, it is assumed that the disturbances in air density and temperature are related by the ratio: . Therefore, the system of equations does not include the heat conduction equation. Indeed, if we compare the continuity equation in the form (7) with the heat conduction Equation (8) under the condition that the divergence of velocity is zero, we see that they are not consistent. The temperature field is found from the diagnostic Boussinesq relation , and not from the solution of the prognostic heat conduction Equation (16). This is the disadvantage of this approximation.

In the incompressible fluid approximation, the buoyancy frequency is equal to . From (42) it follows that strictly vertically propagating IIGWs propagate with an inertial frequency . The maximum frequency is obtained only for horizontally propagating waves, for which . According to Formula (42), the maximum frequency is less than the buoyancy frequency .

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, a mathematical model describing IIGWs in the incompressible fluid approximation has been developed. An examination of the model reveals that, within the framework of the incompressible fluid approximation, the temperature field is inconsistent with the heat conduction equation. The dispersion relation obtained was analyzed, which demonstrated that the traditional β-plane approximation also resulted in an increase in the amplitude of internal gravity waves with height.

It has been demonstrated that the β-effect results in the spectrum being divided into two non-intersecting groups of waves in the low-frequency region. The first group () comprises waves with a minimum frequency , and the second group () comprises waves with a maximum frequency . Thus, in the low-frequency region there is a range of frequencies at which IIGWs do not propagate in the negative direction. This result is of practical importance in the analysis of large-scale atmospheric circulation. A possible physical manifestation of the beta-effect is the inhibition of zonal flow. However, the presence of the above-mentioned “gap” in the frequency spectrum leads to a range of frequencies at which zonal flow inhibition does not occur.

It should be noted that in [], mathematical models of internal gravity waves of a non-planetary scale were previously considered, with the background wind being taken into account. In future research, a mathematical model of planetary IIGWs in the β-plane approximation, incorporating the background wind, will be considered.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G.Z.; methodology, R.G.Z.; validation, R.G.Z.; formal analysis, R.G.Z.; investigation, R.G.Z., A.V.C. and A.R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.Z.; writing—review and editing, A.R.Z.; supervision, R.G.Z.; project administration, A.R.Z.; funding acquisition, R.G.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-21-20083.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. F-Plane Approximation

If the Coriolis parameter is considered constant in Equations (19) and (20), then the system of Equations (19)–(23) reduces to the following form (see, for example, []):

which is obtained from (37) when . Equation (A1) corresponds to the dispersion relation:

The condition for the dispersion relation (A2) to be real will lead to relation (40), and the dispersion relation itself will take the form:

Provided that, i.e., the vertical wavelength is much smaller than the characteristic scale of the atmosphere, the terms in (A3) will disappear, and we will obtain a more familiar form of the dispersion relation.

Similarly, if we assume that the Coriolis parameter is zero in the above expressions, we obtain the dispersion relation for IGWs (nonplanetary scale waves). However, neither IGWs nor IIGWs in the f-plane approximation give such a rich frequency spectrum with non-overlapping ranges as those obtained in the β-plane approximation.

Appendix B. Buoyancy Frequency for Compressible and Incompressible Fluids

In general, the buoyancy frequency of a compressible fluid is described by the expression:

where is the potential temperature in a static atmosphere; is the adiabatic temperature gradient, equal to . The buoyancy frequency of a compressible fluid is called the Brunt–Väisälä frequency.

Expression (A4) can be represented as

If we set the speed of sound to infinity in expression (9), we obtain the condition for an incompressible fluid: the divergence of velocity is zero. Therefore, if we formally set the speed of sound to infinity in expression (A5) [,], we obtain the buoyancy frequency for an incompressible fluid in the form:

A comparison of Formulas (A4)–(A6) shows that they differ quantitatively, so we use the designation for the frequency of an incompressible fluid, as opposed to for the frequency of a compressible fluid.

References

- Nappo, C.J. An Introduction to Atmospheric Gravity Waves; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hines, C.O. Internal atmospheric gravity waves at ionospheric heights. Can. J. Phys. 1960, 38, 1441–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritts, D.C.; Alexander, M.J. Gravity wave dynamics and effects in the middle atmosphere. Rev. Geophys. 2003, 41, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, T.A. Quasi one-dimensional model of the middle atmosphere circulation interacting with internal gravity waves. J. Meteorol. Soc. Japan 1982, 60, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B.R. Internal Gravity Waves; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Plougonven, R.; Zhang, F. Internal gravity waves from atmospheric jets and fronts. Rev. Geophys. 2014, 52, 33–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, B.R. Internal waves in the atmosphere and ocean: Instability mechanisms. In Fluid Mechanics of Planets and Stars; Le Bars, M., Lecoanet, D., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; International Centre for Mechanical Sciences, Courses and Lectures: Udine, Italy, 2020; Volume 595. [Google Scholar]

- Gossard, E.E.; Hooke, W.H. Waves in the Atmosphere: Atmospheric Infrasound and Gravity Waves: Their Generation and Propagation; Elsevier Science & Technology: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Zakinyan, R.G.; Kamil, A.H.; Svetlichny, V.A.; Zakinyan, A.R. Various approximations of mathematical models of internal gravity waves in the stratified atmosphere. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 076636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshevetskii, S.P.; Kurdyaeva, Y.A.; Gavrilov, N.M. Spectra of acoustic-gravity waves in the atmosphere with a quasi-isothermal upper layer. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakinyan, R.G.; Chernyshov, A.V.; Zakinyan, A.R. Various approximations of mathematical models of planetary internal gravity waves in the f-plane approximation. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 2025, 112, 101604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gledzer, A.E.; Gledzer, E.B.; Khapaev, A.A.; Chkhetiani, O.G. Rossby waves and zonal flux anomalies in the analogs of hadley and ferrell cells of the general atmospheric circulation: Model and experiments. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2023, 59, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miropol’sky, Y.Z. Dynamics of Internal Gravity Waves in the Ocean; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Boston, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Brekhovskikh, L.M.; Goncharov, V. Mechanics of Continua and Wave Dynamics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dellar, P.J. Variations on a beta-plane: Derivation of non-traditional beta-plane equations from Hamilton’s principle on a sphere. J. Fluid Mech. 2011, 674, 174–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasahara, A. The roles of the horizontal component of the Earth’s angular velocity in nonhydrostatic linear models. J. Atmos. Sci. 2003, 60, 1085–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reznik, G.M. Wave adjustment: General concept and examples. J. Fluid Mech. 2015, 779, 514–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A.E. Atmosphere–Ocean Dynamics; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Holton, J.R.; Hakim, G.J. An Introduction to Dynamic Meteorology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Boussinesq, J. Théorie Analytique de la Chaleur; Gathier-Villars: Paris, France, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Eckermann, S.D.; Gibson-Wilde, D.E.; Bacmeister, J.T. Gravity wave perturbations of minor constituents: A parcel advection methodology. J. Atmos. Sci. 1998, 55, 3521–3539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakinyan, R.G.; Kamil, A.H.; Svetlichny, V.A.; Zakinyan, A.R. On the frequency of internal gravity waves in the atmosphere: Comparing theory with observations. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).