A Global Investigation of Outdoor Climatic Comfort

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Climate, Well-Being, Mobility, and the Environment

1.2. Objectives and Scientific Novelty

- Integrate outdoor comfort indicators based on relative humidity, solar radiation, and temperature into a unified comfort index;

- Evaluate the spatial global distribution of outdoor climatic comfort;

- Examine future demographic scenarios to identify alignments and misalignments between human dynamics and climatic comfort.

2. Materials and Methods

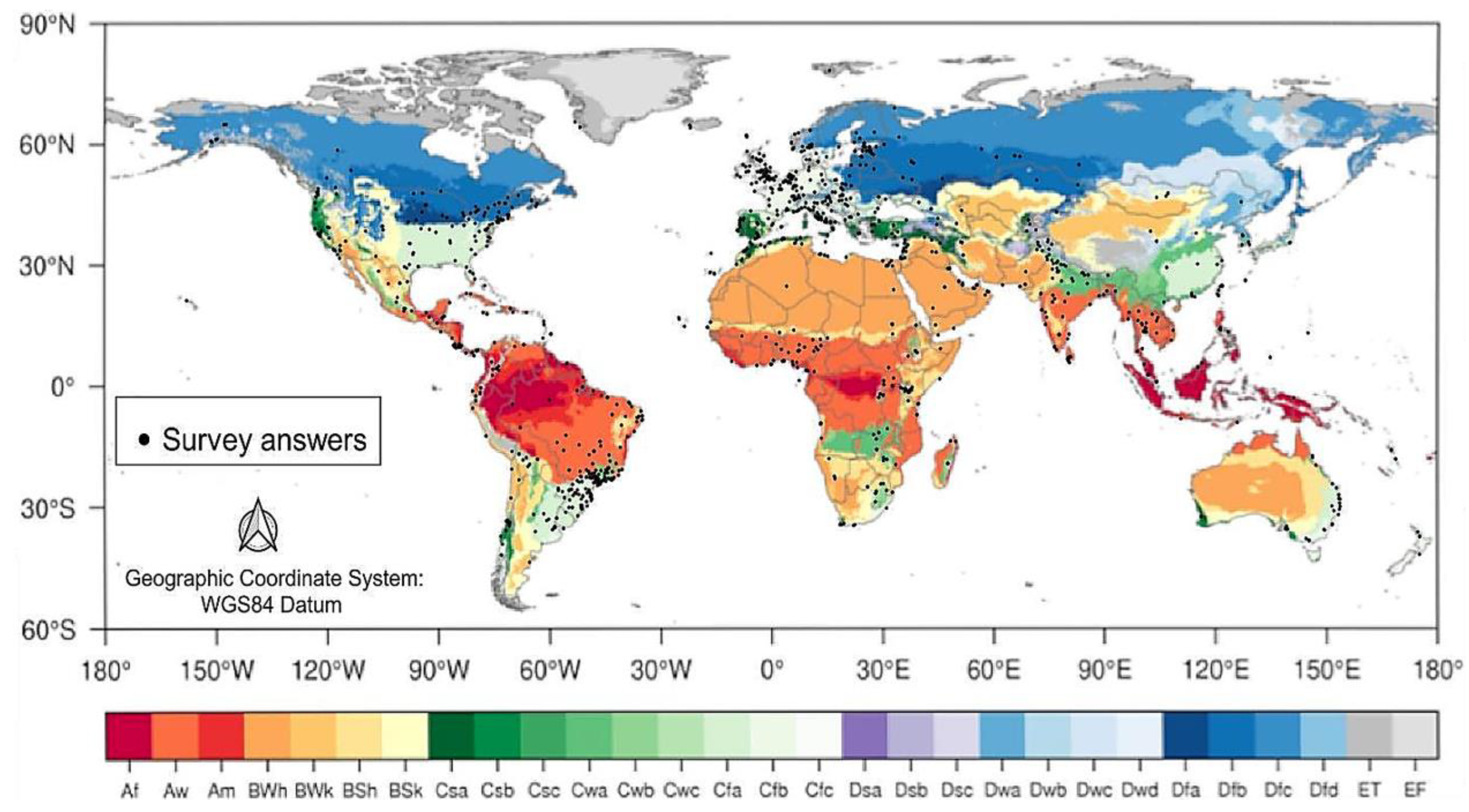

2.1. Survey Design and Disclosure

2.2. Comfort Indices

2.3. Databases

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. Maps of Outdoor Climatic Comfort

3. Results and Discussion

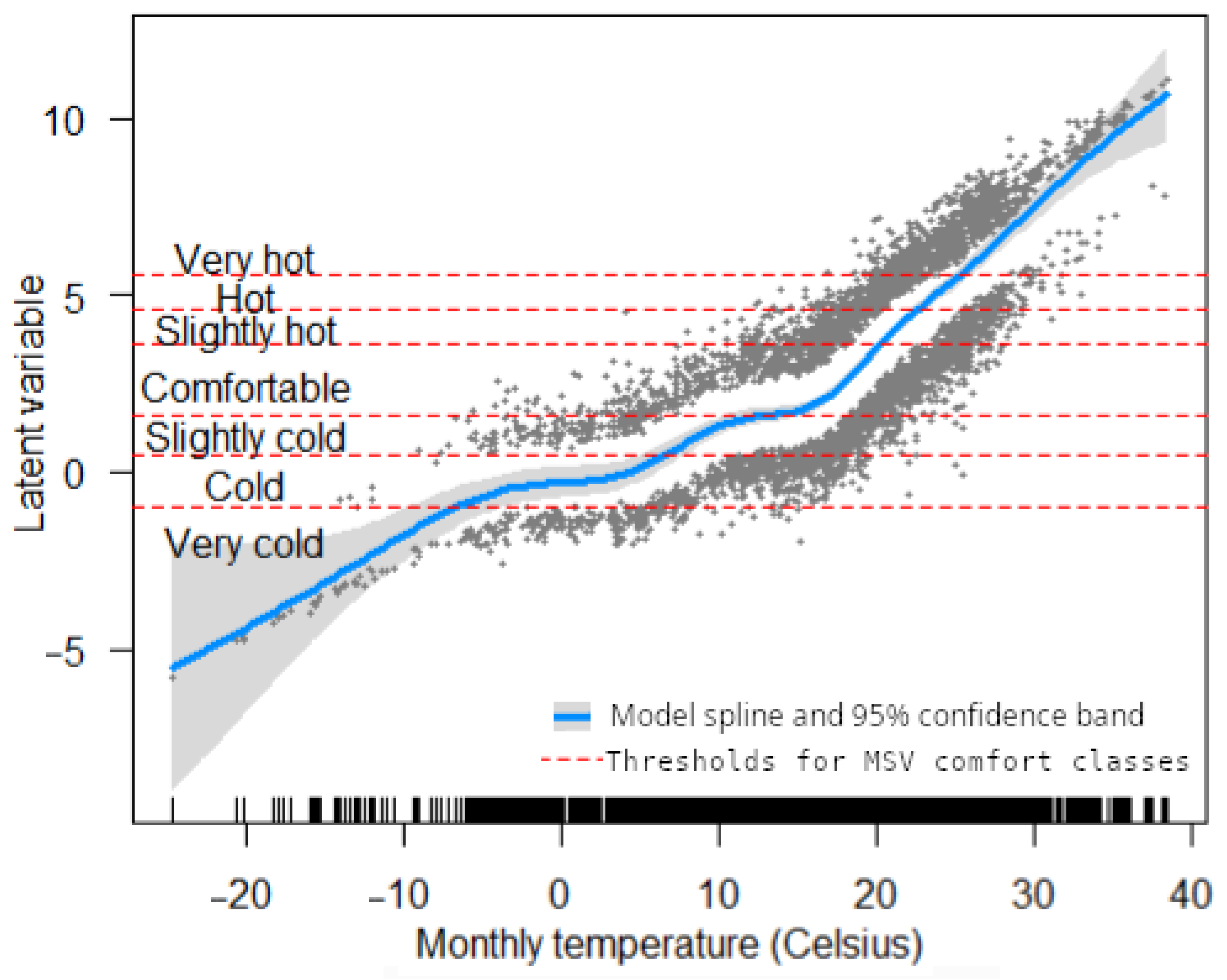

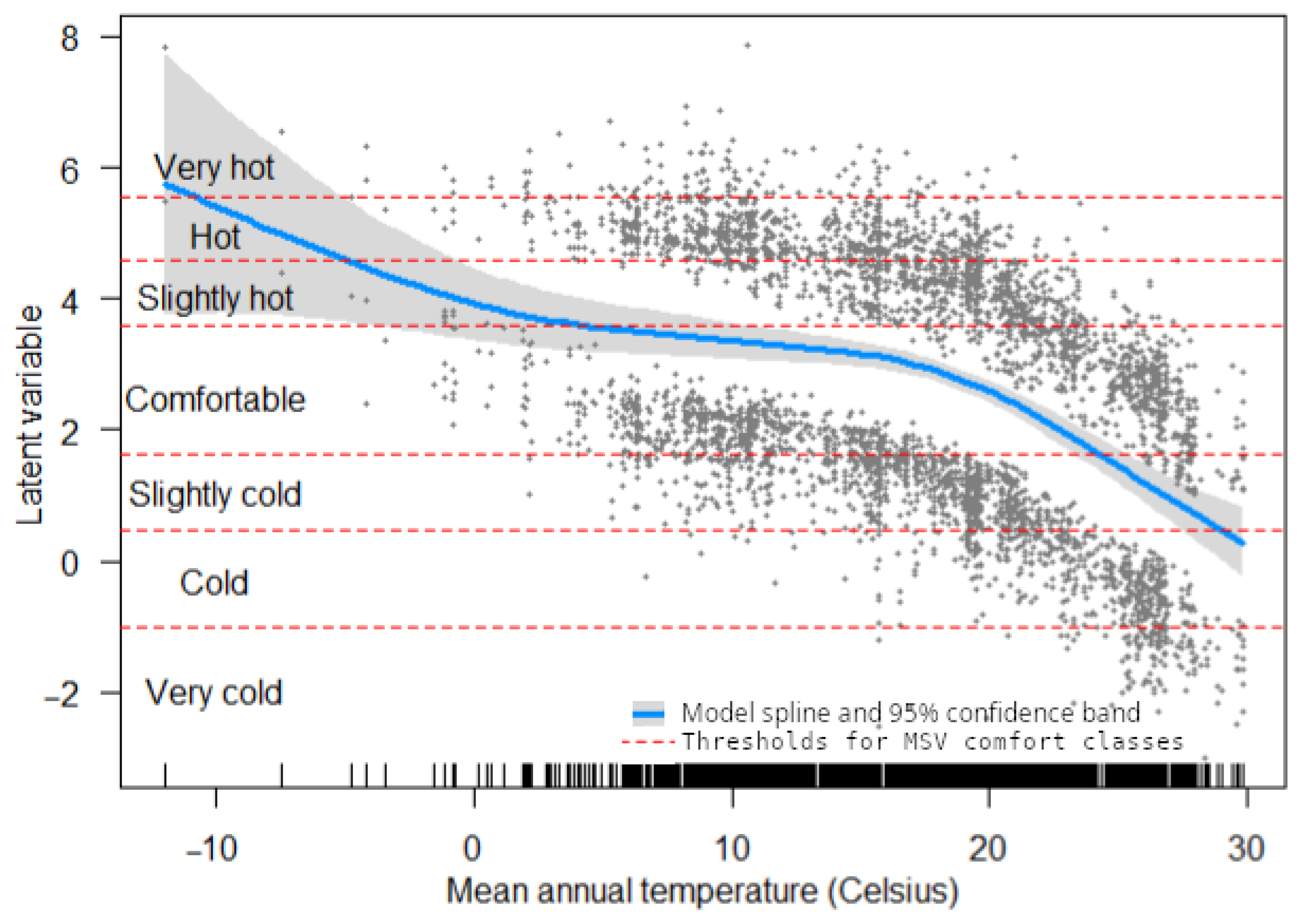

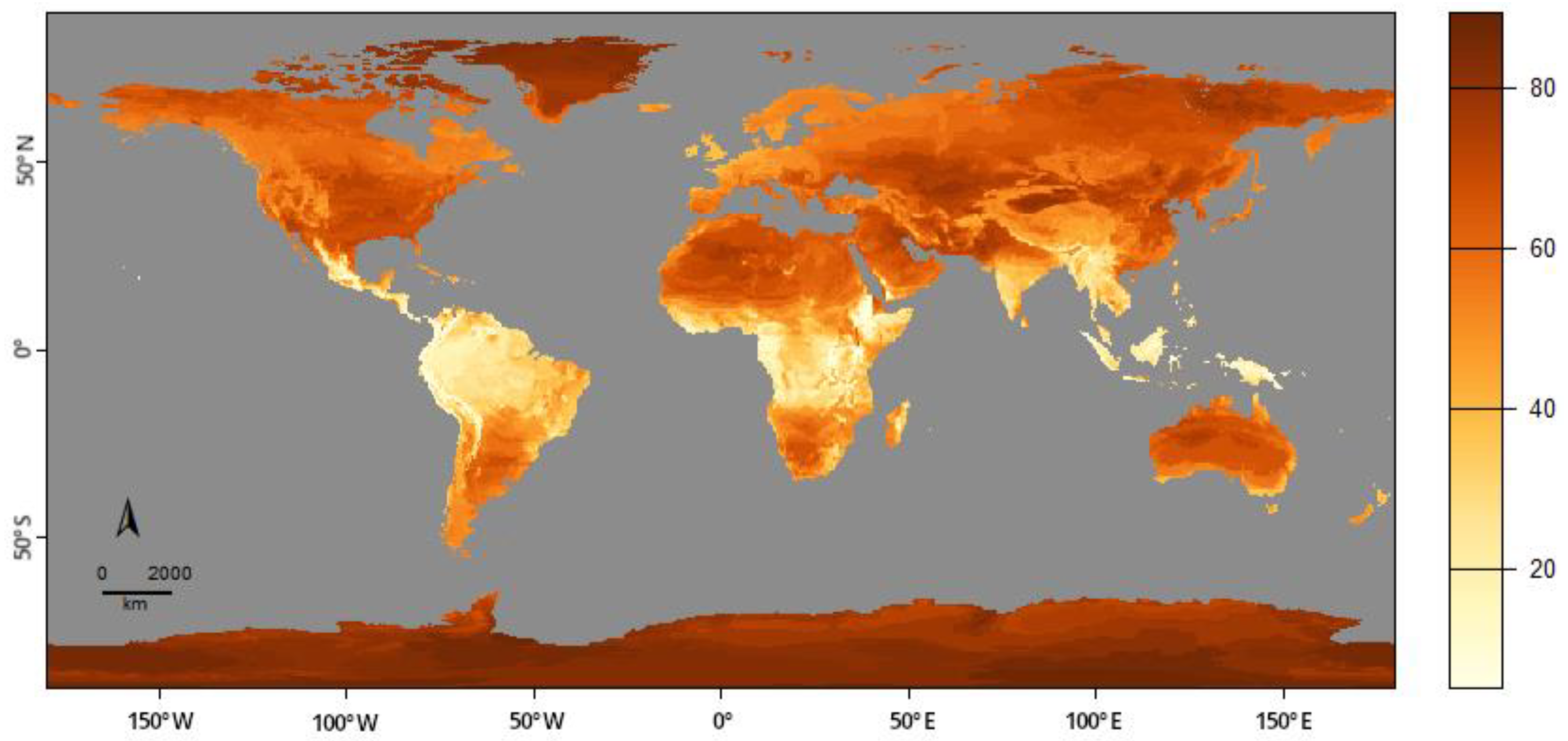

3.1. Models for Temperature, Humidity, and Natural Lighting

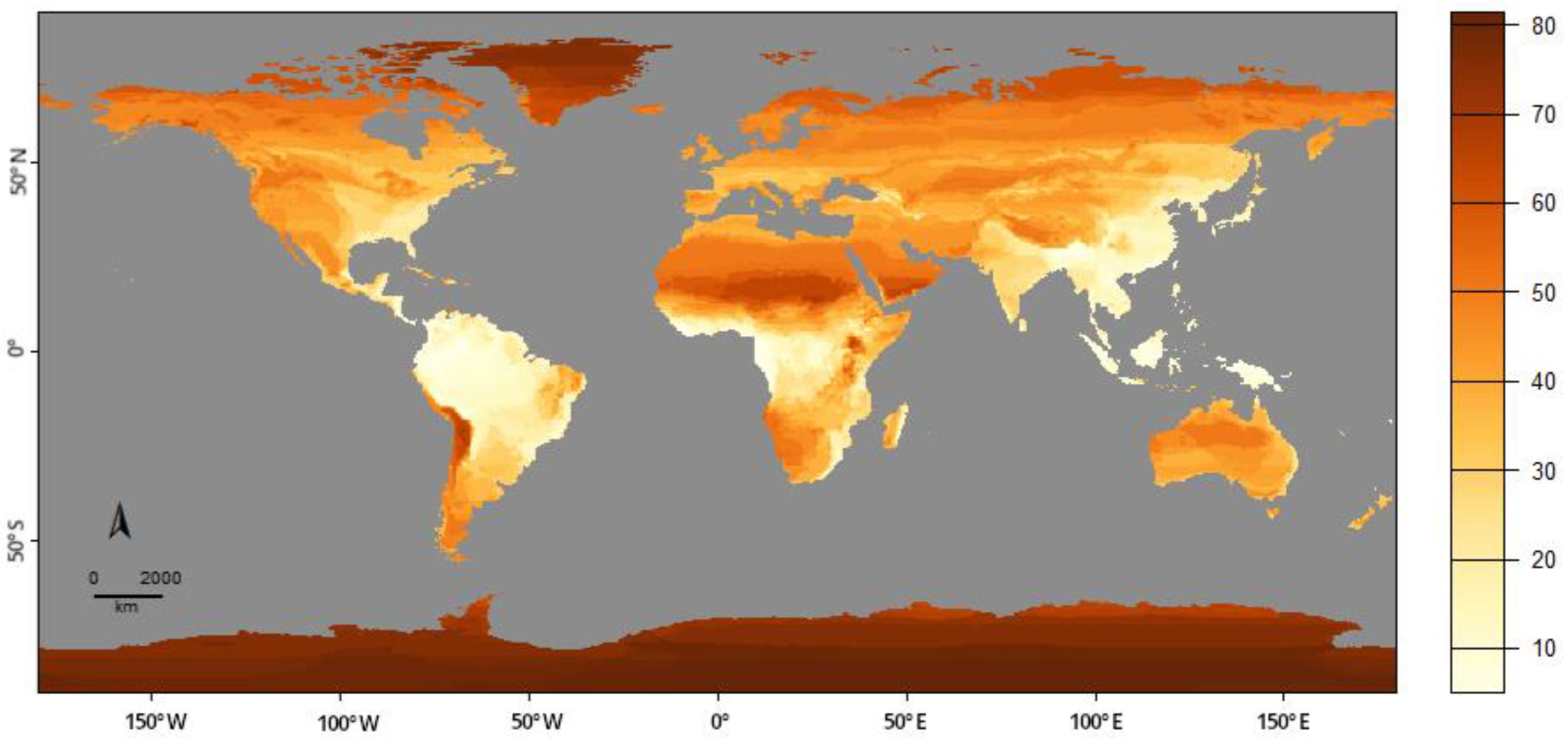

3.1.1. Temperature Comfort Model

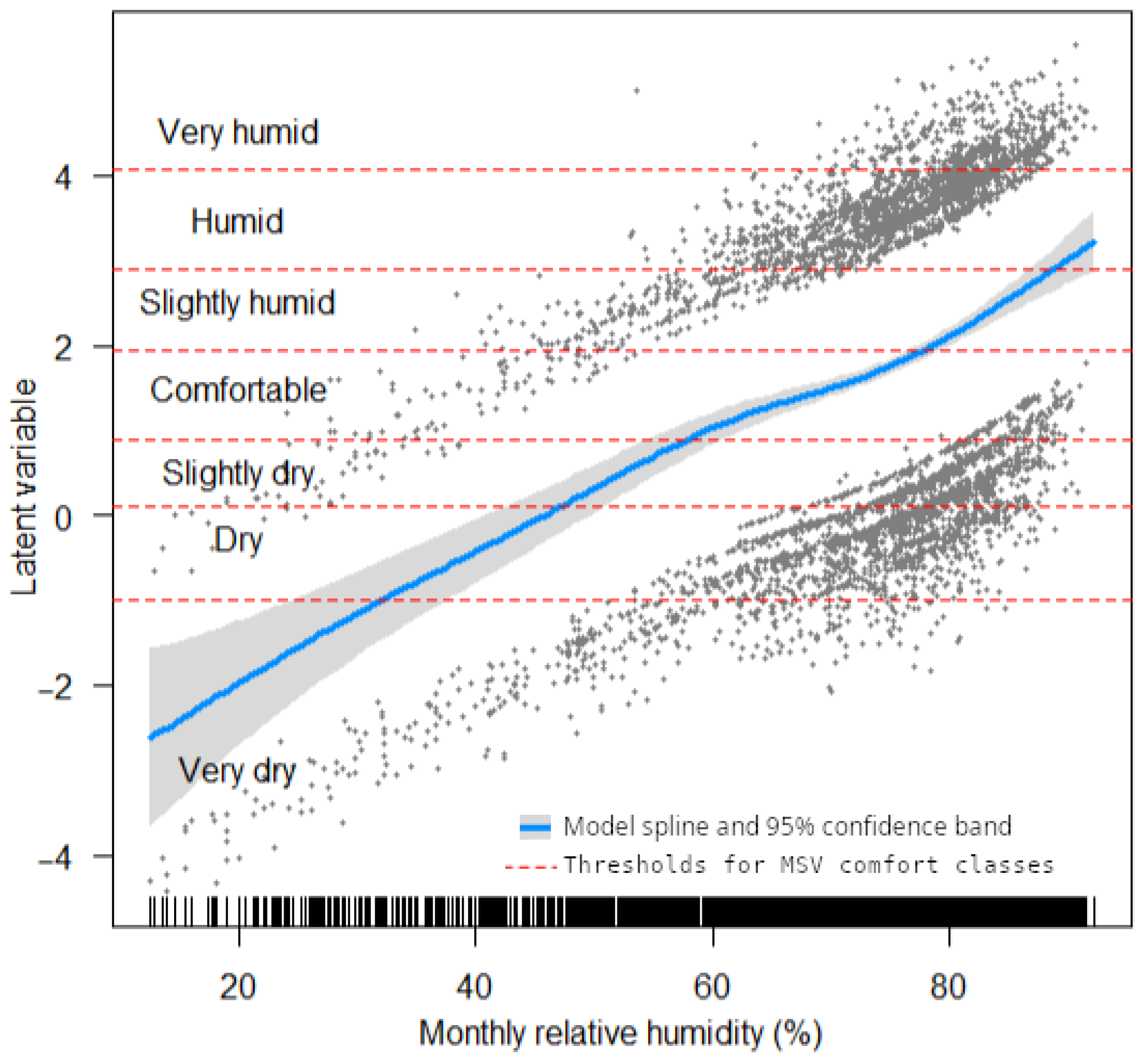

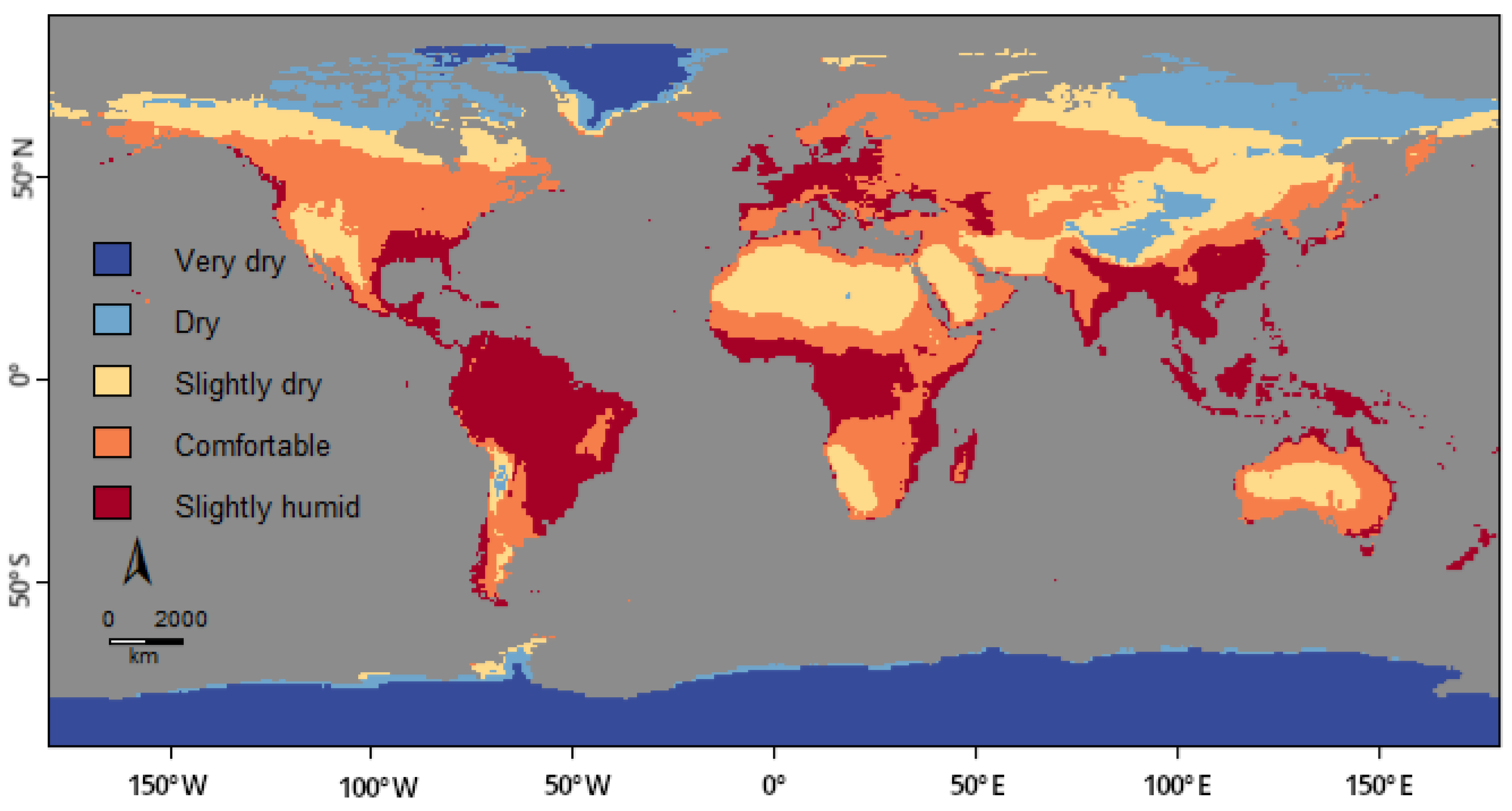

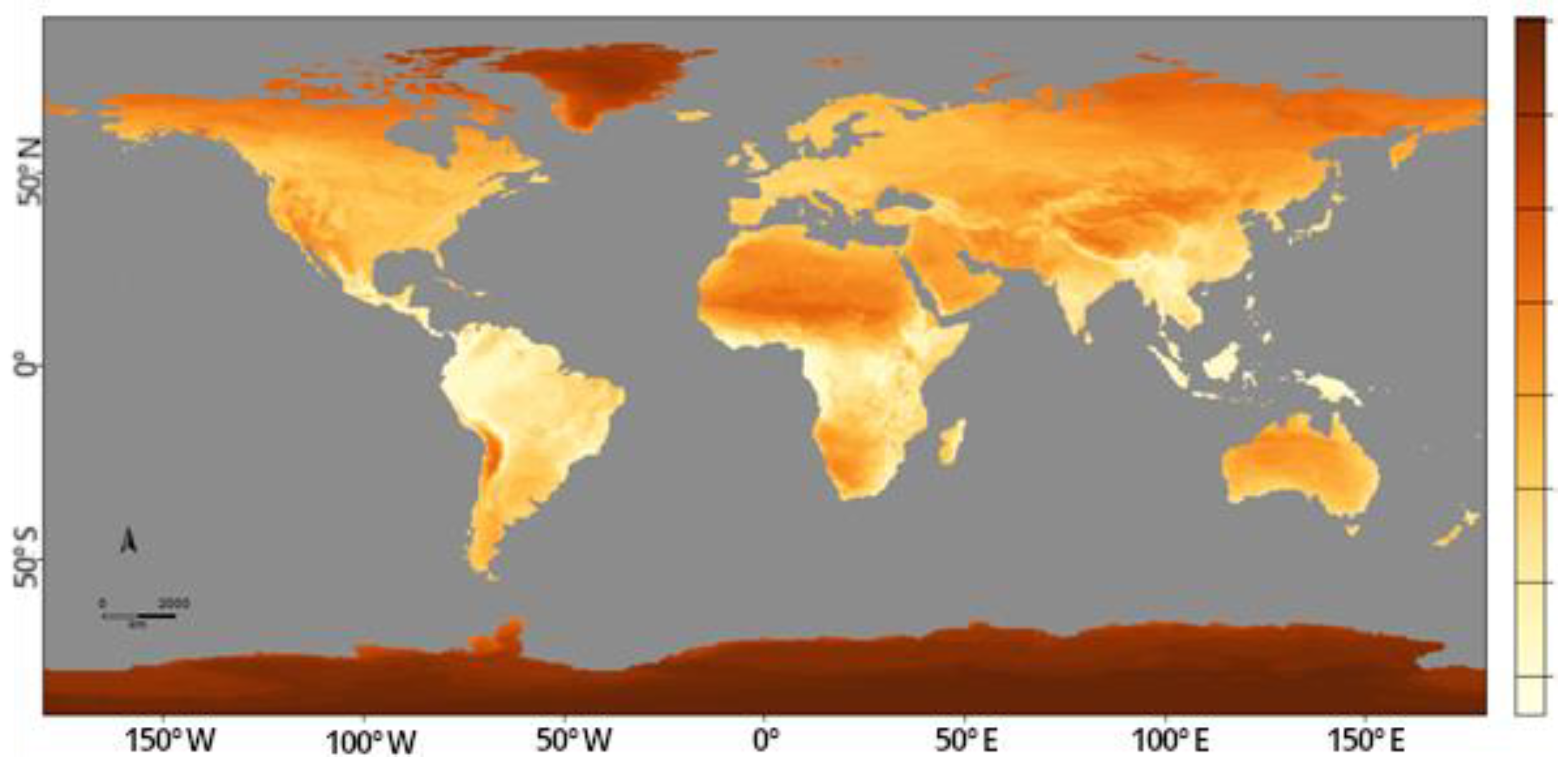

3.1.2. Humidity Comfort Model

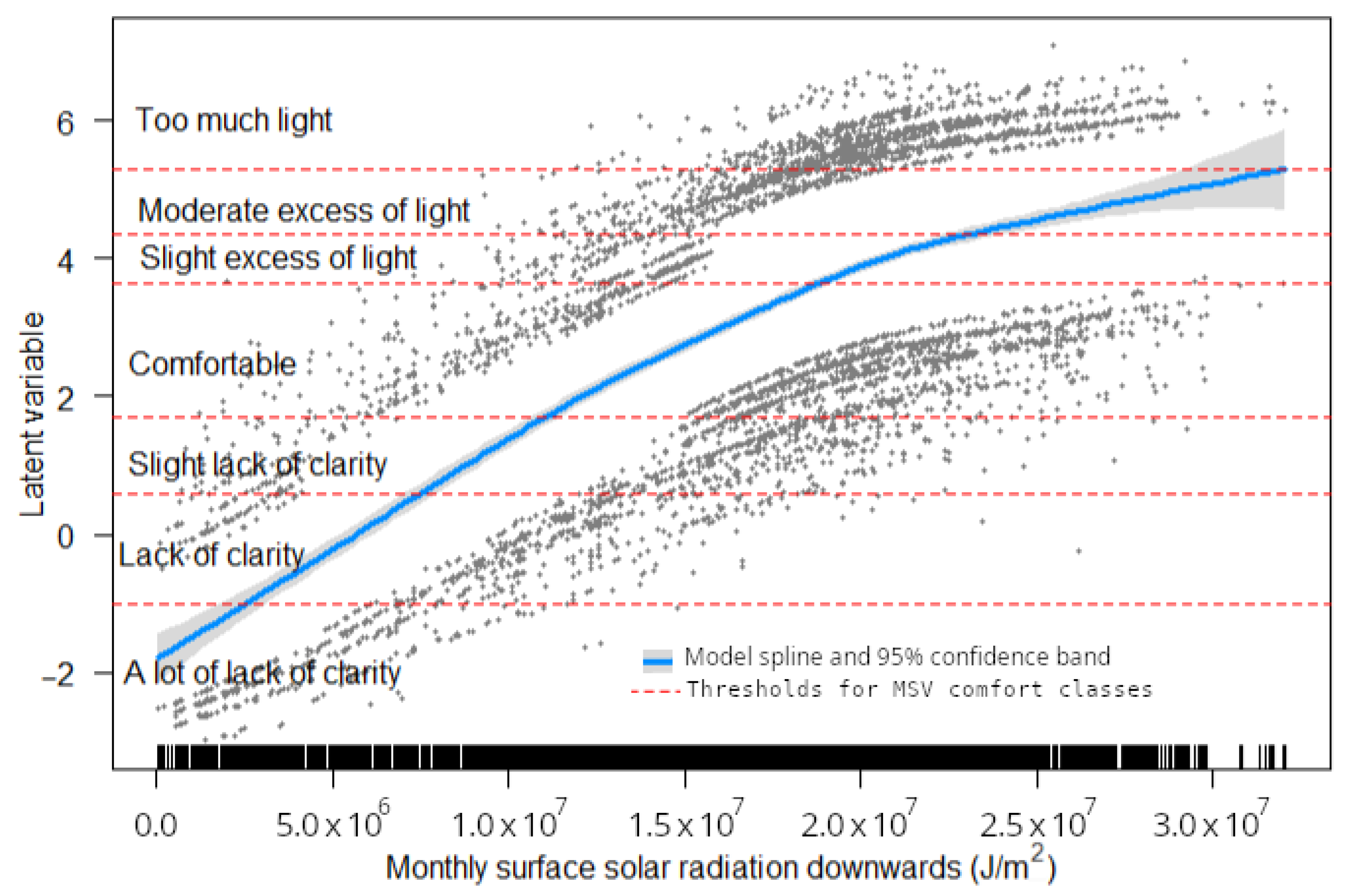

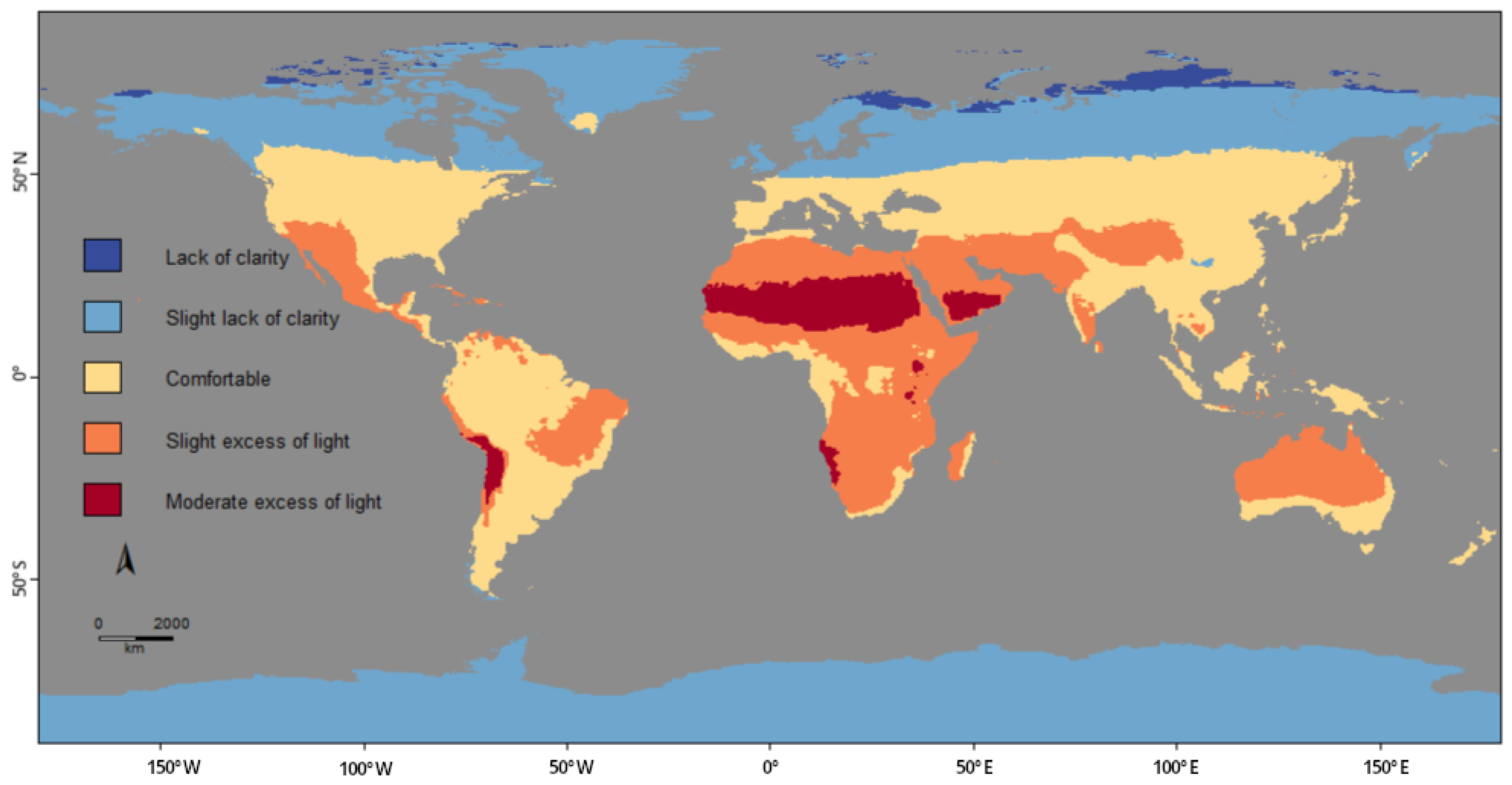

3.1.3. Natural Lighting Comfort Model

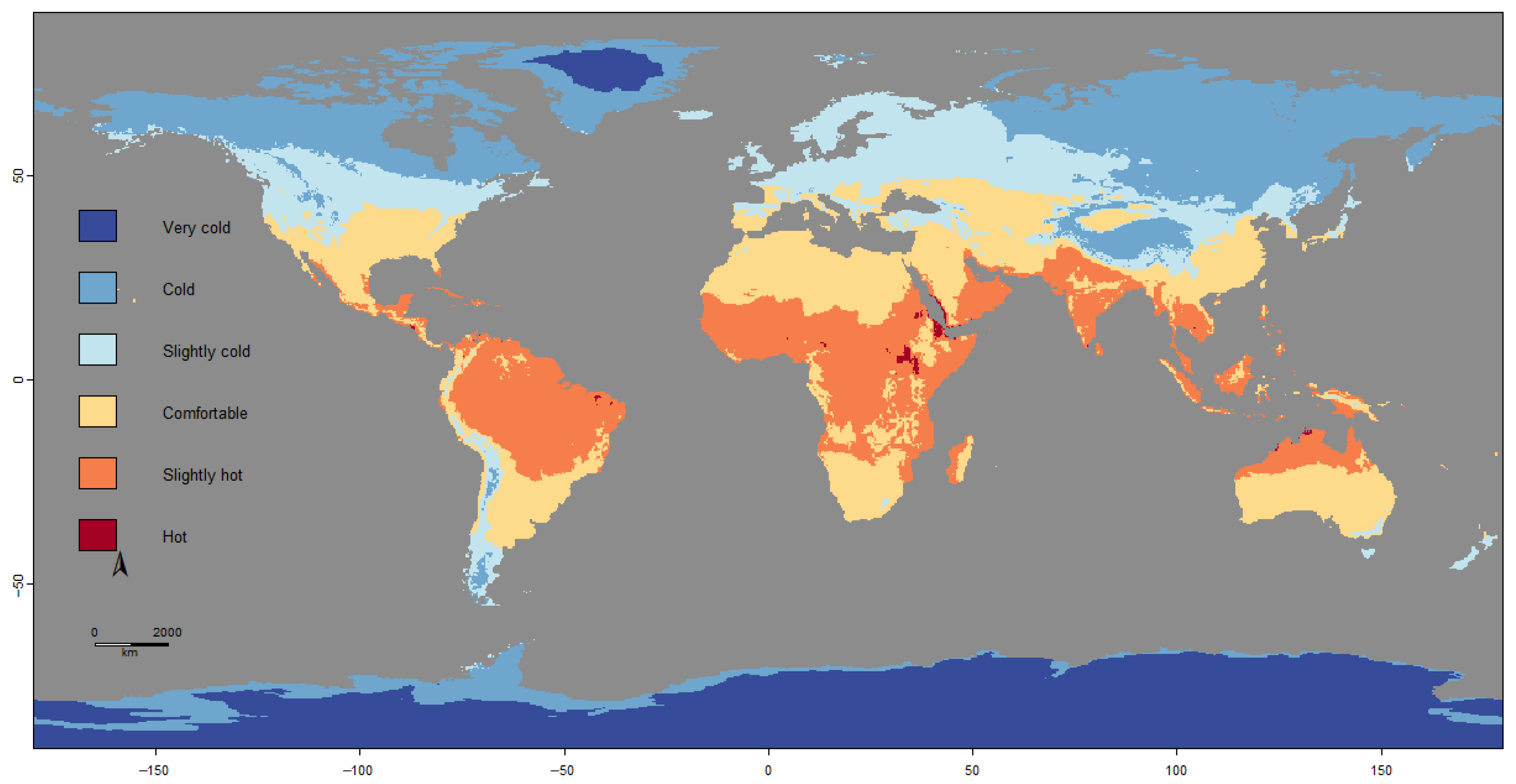

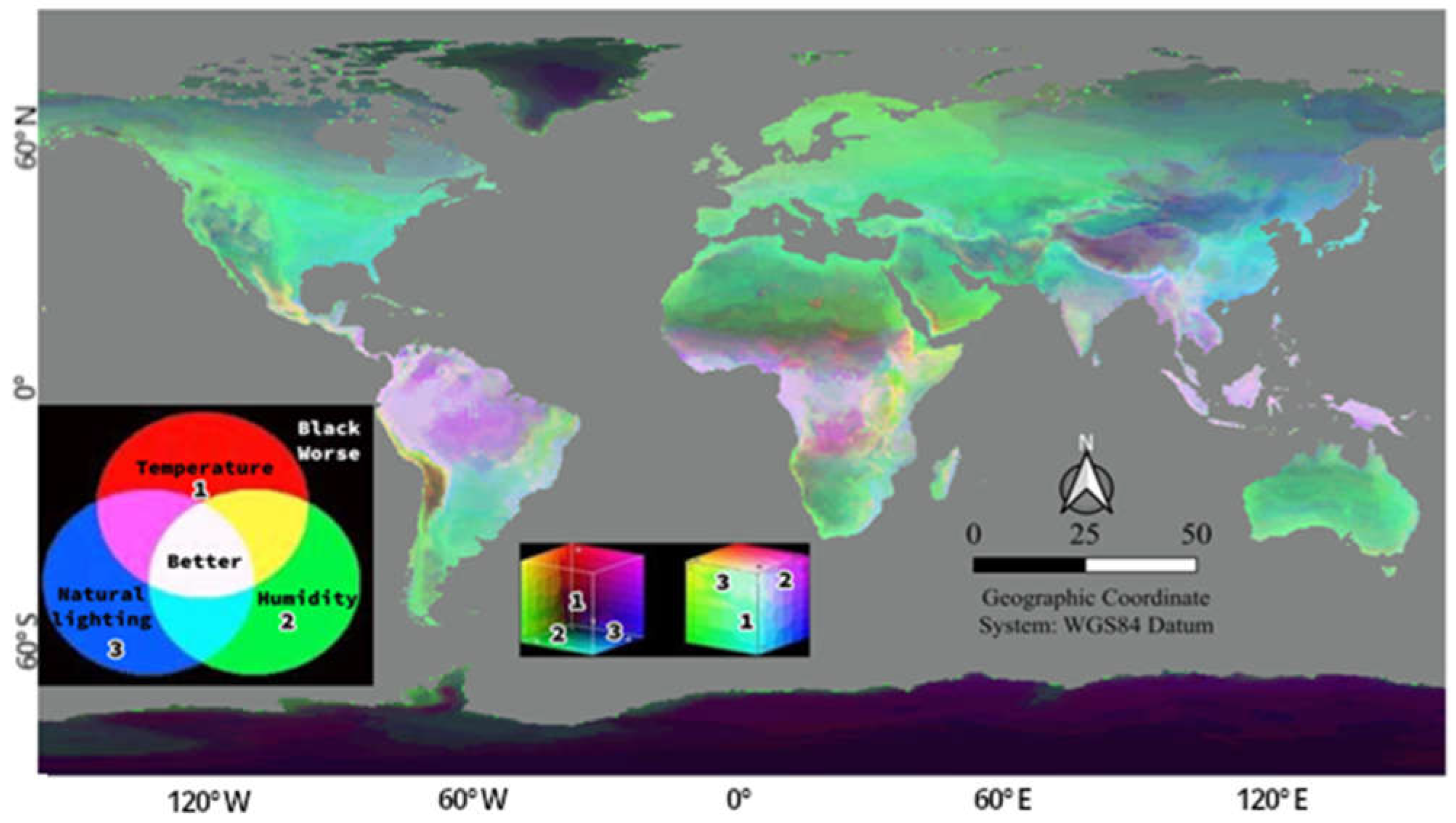

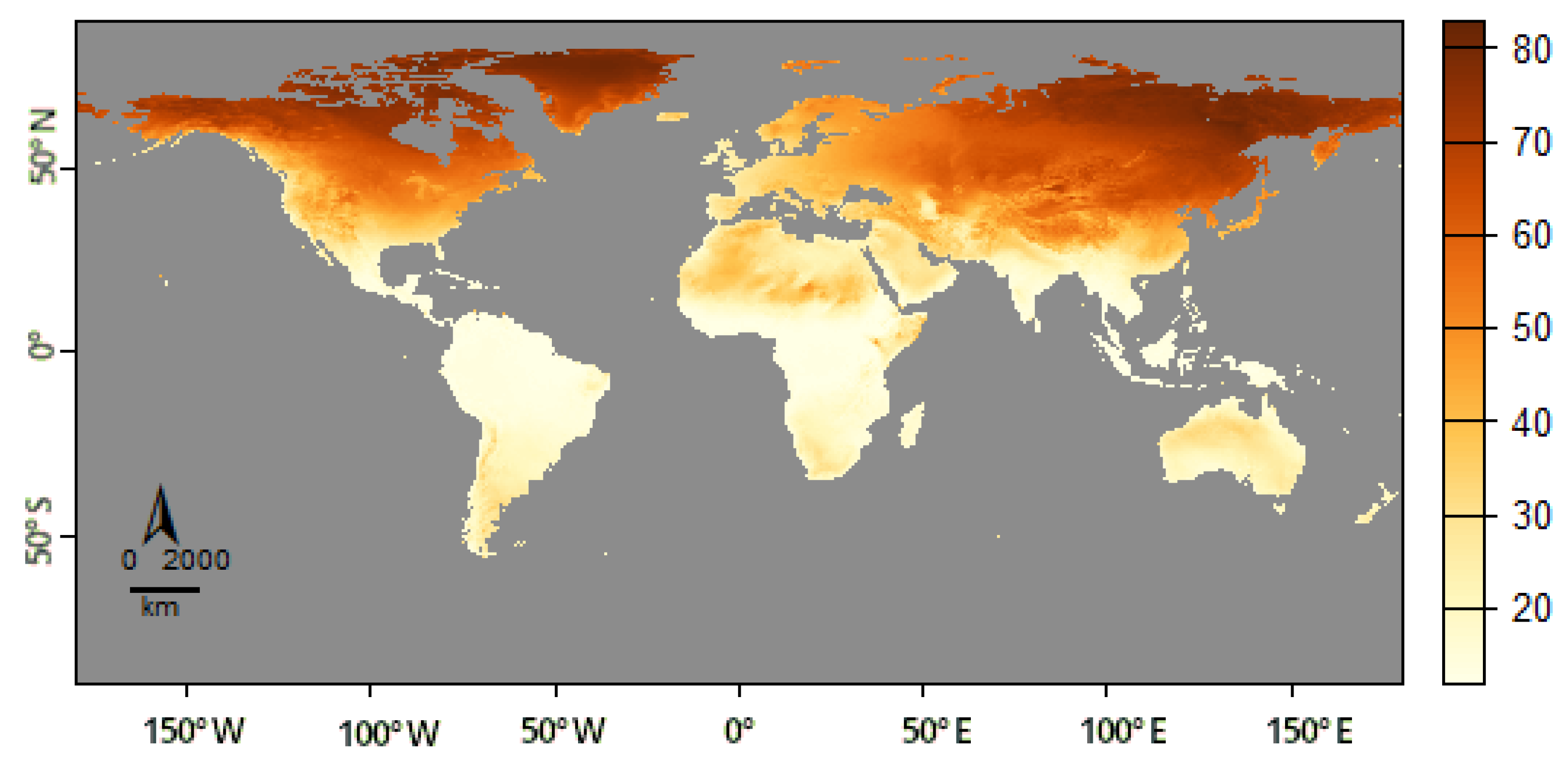

3.2. Integrated Maps of Climatic Comfort

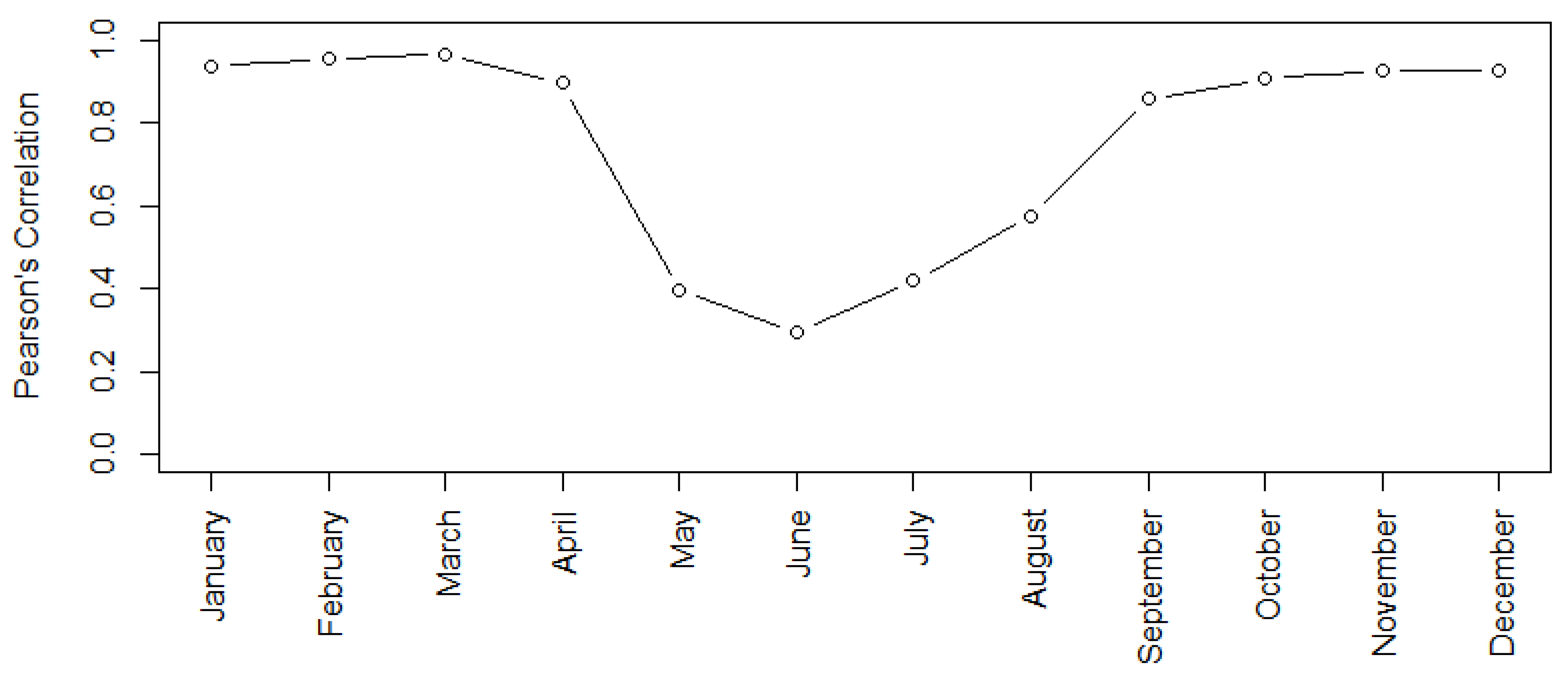

3.3. Comparison with GOCI and UTCI Indices

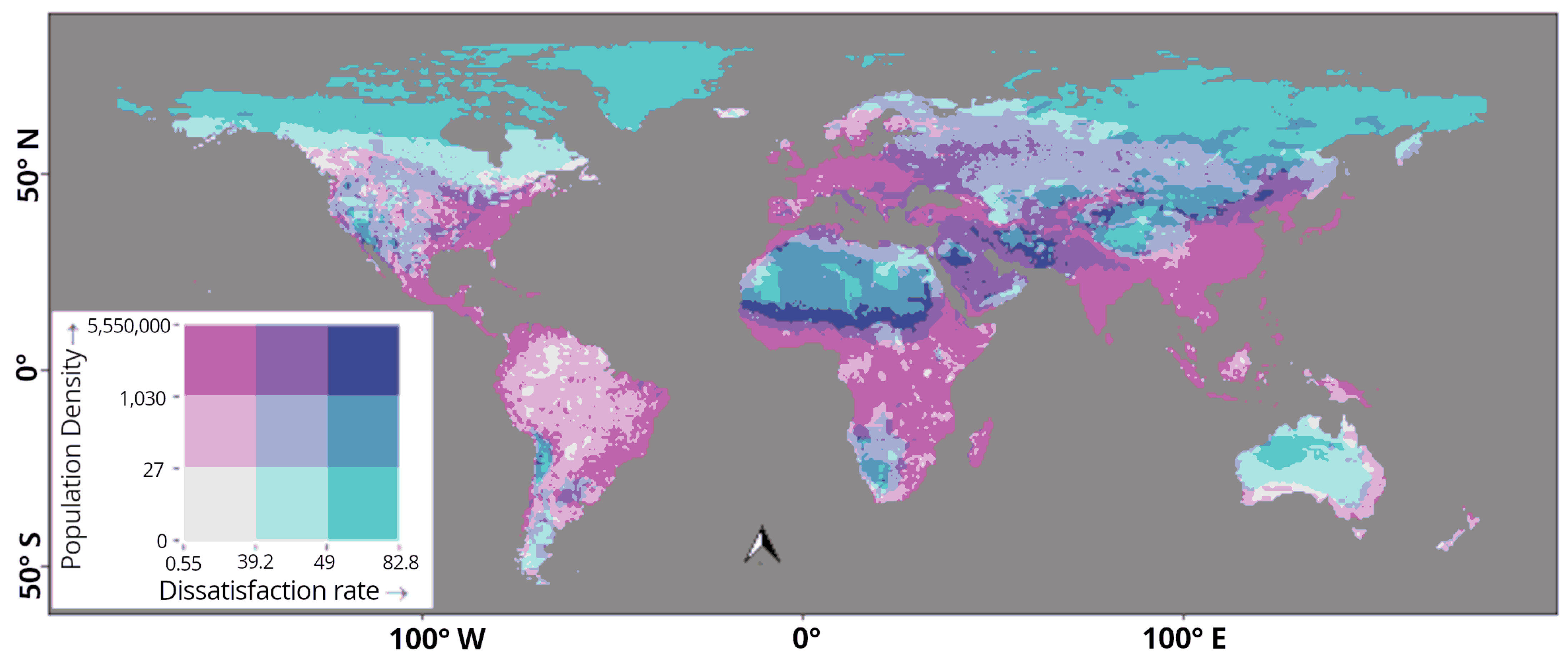

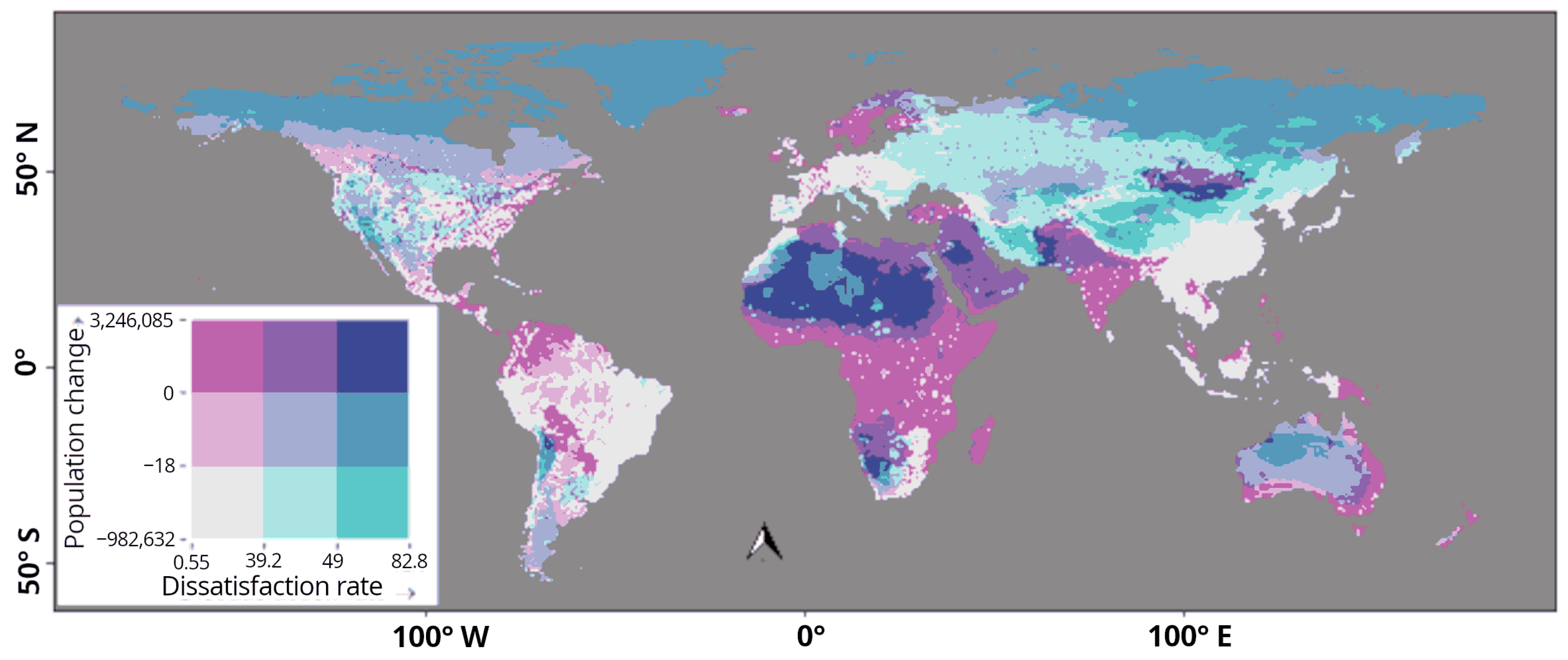

3.4. Spatial Relationships Between Climatic Comfort and Demographic Patterns

- In temperate regions, the climate is likely to become less comfortable due to more frequent heat waves and hotter summers, partially offset by warmer—and thus less uncomfortable—winters.

- Global warming may render some currently comfortable, densely populated tropical and equatorial areas less hospitable—for example, Indonesia and coastal areas of Brazil and Eastern Africa. However, this assessment should consider the local adaptation capacity, as modeled in this study (Figure 4).

- Extremely cold regions are expected to become more thermally comfortable due to global warming. Nonetheless, the low and declining population density in these regions limits the global significance of this benefit.

- Regarding humidity, densely populated monsoon regions—such as South and Southeast Asia, West Africa, and Southeast Brazil—are likely to experience more pronounced seasonal humidity extremes, becoming uncomfortably wetter during rainy seasons and uncomfortably drier during dry seasons.

- Changes in climatic comfort are expected to be more pronounced in continental interiors, particularly Central Asia, whereas coastal areas—which are typically more densely populated—may benefit from the moderating influence of proximity to the sea.

- Climate projections indicate a northward shift in the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), altering the extent of uncomfortably wet climates, alongside a northward expansion of the subtropical high-pressure belts (deserts and semi-arid zones). These shifts will necessitate adaptation strategies for populations experiencing changing climatic conditions.

3.5. Policy Implications

3.6. Limitations, Uncertainties, and Prospects for Future Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ASHRAE | American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| DR | Dissatisfaction Rate |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| GOCI | Global Outdoor Comfort Index |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| ITCZ | Intertropical Convergence Zone |

| MRT | Mean Radiant Temperature |

| MSV | Mean Sensation Vote |

| PMV | Predicted Mean Vote |

| PPD | Predicted Percentage of Dissatisfaction |

| ROAD | The ROCEEH Out of Africa Database |

| SEDAC | Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center |

| SSPs | Shared Socioeconomic Pathways |

| SSR | Surface Solar Radiation |

| UTCI | Universal Thermal Climate Index |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- IPCC. Synthesis Report on Climate Change; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Fischer, R.; Van de Vliert, E. Does climate undermine subjective well-being? A 58-nation study. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2011, 37, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 7730; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/85803.html (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Martini, A.; Biondi, D.; Batista, A.C.; Zamproni, K. A periodicidade diária do índice de conforto térmico na arborização de ruas de Curitiba-PR. Sci. Plena 2013, 9, 057301-1. Available online: https://scientiaplena.emnuvens.com.br/sp/article/view/1360 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Corbella, O.; Yannas, S. Em Busca de uma Arquitetura Sustentável Para os Trópicos: Conforto Ambiental, 2nd ed.; Revan: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55-2023; Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ashrae.org/technical-resources/bookstore/standard-55-thermal-environmental-conditions-for-human-occupancy (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Staiger, H.; Laschewski, G.; Grätz, A. The perceived temperature–a versatile index for the assessment of the human thermal environment. Part A: Scientific basics. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Indoor Air Quality: Biological Contaminants. Report on a WHO Meeting; WHO Regional Publications; European Series No. 31; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1988; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/260557 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Environmental Protection Agency. A Brief Guide to Mold, Moisture, and Your Home; Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/mold/brief-guide-mold-moisture-and-your-home (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Wirz-Justice, A. Seasonality in affective disorders. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2018, 258, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melrose, S. Seasonal Affective Disorder: An Overview of Assessment and Treatment Approaches. Depress. Res. Treat. 2015, 2015, 178564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fell, G.L.; Robinson, K.C.; Mao, J.; Woolf, C.J.; Fisher, D.E. Skin β-endorphin mediates addiction to UV light. Cell 2014, 157, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, J.; Mellerup, E.; Bolwig, T.; Scheike, T.; Dam, H. The influence of climate on development of winter depression. J. Affect. Disord. 1996, 37, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, N.E.; Sack, D.A.; Gillin, J.C.; Lewy, A.J.; Goodwin, F.K.; Davenport, Y.; Mueller, P.S.; Newsome, D.A.; Wehr, T.A. Seasonal Affective Disorder. A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1984, 41, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, P.R. Light, lighting and human health. Light. Res. Technol. 2022, 54, 101–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enescu, D. A review of thermal comfort models and indicators for indoor environments. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2017, 79, 1353–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honjo, T. Thermal comfort in outdoor environment. Glob. Environ. Res. 2009, 13, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Qaid, A.; Lamit, H.B.; Ossen, D.R.; Shahminan, R.N.R. Urban heat island and thermal comfort conditions at micro-climate scale in a tropical planned city. Energ. Build. 2016, 133, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topay, M. Mapping of thermal comfort for outdoor recreation planning using GIS: The case of Isparta Province (Turkey). Turk. J. Agric. For. 2013, 37, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzarakis, A.; Amelung, B. Physiological equivalent temperature as indicator for impacts of climate change on thermal comfort of humans. In Seasonal Forecasts, Climatic Change and Human Health; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, C.; Barnard, C.; Prudhomme, C.; Cloke, H.L.; Pappenberger, F. ERA5-HEAT: A global gridded historical dataset of human thermal comfort indices from climate reanalysis. Geosci. Data J. 2020, 8, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, G.R. Special issue: Universal thermal comfort index (UTCI). Int. J. Biometeorol. 2012, 56, 419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, E.; Callejas, I.J.A.; Rosa, L.A.; Cunha, E.G.; Carvalho, L.; Leder, S.; Vieira, T.; Hirashima, S.; Drach, P. Regional Adaptation of the UTCI: Comparisons Between Different Datasets in Brazil. In Applications of the Universal Thermal Climate Index UTCI in Biometeorology; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 113–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golasi, I.; Salata, F.; de Vollaro, E.L.; de Lieto Vollaro, A.; Coppi, M. Complying with the demand of standardization in outdoor thermal comfort: A first approach to the Global Outdoor Comfort Index (GOCI). Build. Environ. 2018, 130, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ng, E. Outdoor thermal comfort and outdoor activities: A review of research in the past decade. Cities 2012, 29, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzholzer, S. Research and design for thermal comfort in Dutch urban squares. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2012, 64, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeciras, J.A.R.; Coch, H.; Pérez, G.P.; Yeras, M.C.; Matzarakis, A. Human thermal comfort conditions and urban planning in hot-humid climates—The case of Cuba. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2016, 60, 1151–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zölch, T.; Rahman, M.A.; Pfleiderer, E.; Wagner, G.; Pauleit, S. Designing public squares with green infrastructure to optimize human thermal comfort. Build. Environ. 2019, 149, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, A.M.; Tapper, N.J.; Beringer, J.; Loughnan, M.; Demuzere, M. Watering our cities: The capacity for Water Sensitive Urban Design to support urban cooling and improve human thermal comfort in the Australian context. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 2013, 37, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punia, A.; Singh, R.P.; Chauhan, N.S. Drivers of climate migration. In Global Climate Change and Environmental Refugees; Pardep, S., Bendagwapang, A., Yadav, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpkins, G. Low income population groups trapped. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2022, 3, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duplan, K.; Cranston, S. Towards geographies of privileged migration: An intersectional perspective. Prog. Hum. Geog. 2023, 47, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornweg, D.; Sugar, L.; Gomez, C.L. Cities and Greenhouse Gas Emissions: Moving Forward; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport, J. Moving to nice weather. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 2007, 37, 375–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trudel, J.M. International human resources management: A new challenge. Port. J. Manage. Stud. 2009, 14, 149–162. Available online: https://repositorio.ulisboa.pt/entities/publication/b8457af6-fc19-4175-9f9b-3205bbbf9afc (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Williams, A.M.; Hall, C.M. Tourism, migration, circulation and mobility: The contingencies of time and place. In Tourism and Migration; Hall, C.M., Williams, A.M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, Netherlands, 2002; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schellen, L.; van Lichtenbelt, W.D.; Loomans, M.G.; Toftum, J.; De Wit, M.H. Differences between young adults and elderly in thermal comfort, productivity, and thermal physiology in response to a moderate temperature drift and a steady-state condition. Indoor Air 2010, 20, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noelke, C.; McGovern, M.; Corsi, D.J.; Jimenez, M.P.; Stern, A.; Wing, I.S.; Berkman, L. Increasing ambient temperature reduces emotional well-being. Environ. Res. 2016, 151, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirsch, S. The incredible shrinking world? Technology and the production of space. Environ. Plan. D 1995, 13, 529–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dragicevic, S.; Castro, F.A.; Sester, M.; Winter, S.; Coltekin, A.; Pettit, C.; Jiang, B.; Haworth, J.; Stein, A.; et al. Geospatial big data handling theory and methods: A review and research challenges. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 115, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, V.V. O profissional de meio ambiente e o contato com a natureza. Qual. Rev. Eletrônica 2011, 1, 1–10. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/272505020_O_profissional_de_meio_ambiente_e_o_contato_com_a_natureza (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Fanger, P.O. Thermal Comfort; Danish Technical Press: Lyngby, Copenhagen, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10551; Ergonomics of the Physical Environment—Subjective Judgment Scales for Assessing Physical Environments, 2nd ed. Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7730; Moderate Thermal Environment—Determination of the PMV and PPD Indices and Specification of the Conditions for Thermal Comfort. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Krüger, E.; Rossi, F.; Drach, P. Calibration of the physiological equivalent temperature index for three different climatic regions. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2017, 61, 1323–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J. ERA5-Land monthly averaged data from 1950 to present. In Copernicus Climate Change Service, Climate Data Store; Copernicus Publications: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Rozum, N.; Vamborg, F.S.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Buontempo, C.; Horányi, J.; Peubey, C.; et al. Essential climate variables for assessment of climate variability from 1979 to present. In Copernicus Climate Change Service, Climate Data Store; Copernicus Publications: Göttingen, Germany, 2018; Available online: https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/ecv-for-climate-change (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Biavati, G.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Rozum, I.; et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on single levels from 1940 to present. In Copernicus Climate Change Service, Climate Data Store; Copernicus Publications: Göttingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, B.; O’Neill, B.C. Global One-Eighth Degree Population Base Year and Projection Grids Based on the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, Revision 01; NASA Socioeconomic Data and Applications Center: Palisades, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Kriegler, E.; Riahi, K.; Ebi, K.L.; Hallegatte, S.; Carter, T.R.; Mathur, R.; van Vuuren, D.P. A new scenario framework for climate change research: The concept of shared socioeconomic pathways. Climatic Change 2014, 122, 387–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.N. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Population Prospects 2024; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://population.un.org/wpp/publications (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Mangiafico, S.S. Summary and Analysis of Extension Program Evaluation in R; Rutgers Cooperative Extension: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2016; Available online: https://rcompanion.org/handbook/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Somers, R.H. A new asymmetric measure of association for ordinal variables. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1962, 27, 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorell, A.; Aho, K.; Alfons, A.; Anderegg, N.; Aragon, T.; Arppe, A.; Baddeley, A.; Barton, K.; Bolker, B.; Borchers, H.W. DescTools: Tools for Descriptive Statistics, R package version 0.99.54; CRAN. 2024. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=DescTools (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Agresti, A.; Tarantola, C. Simple ways to interpret effects in modeling ordinal categorical data. Stat. Neerl. 2018, 72, 210–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, R. Confidence intervals for rank statistics: Somers’ D and extensions. Stata J. 2006, 6, 309–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, V.V.; Pinho, C.M.D. Multivariate Geovisualization of Dengue, Zika and Chikungunya cases in Brazil: A didactic experience. Hygeia 2017, 13, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.C. Make a Bivariate Plot Using Raster Data and Ggplot2. GitHub, Gist. 2020. Available online: https://gist.github.com/scbrown86/2779137a9378df7b60afd23e0c45c188 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Prener, C. Options for Breaks and Legends. 2022. Available online: https://chris-prener.github.io/biscale/articles/breaks.html (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Geiger, R. The Climate Near the Ground; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, D.; Liang, S.; Wang, D.; Liu, Z. A 1 km global dataset of historical (1979–2013) and future (2020–2100) Köppen–Geiger climate classification and bioclimatic variables. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 5087–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Indoor Environment: Health Aspects of Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Light and Noise; WHO Environmental Health in Rural and Urban Development and Housing Unit: Geneva, Switzerland, 1990; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/62723/WHO_EHE_RUD_90.2.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Karyono, T.H. Predicting comfort temperature in Indonesia, an initial step to reduce cooling energy consumption. Buildings 2015, 5, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komolafe, K.; Akingbade, F.O.A. Analysis of thermal comfort in Lagos, Nigeria. Global J. Environ. Sci. 2003, 2, 59–65. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/gjes/article/view/2407 (accessed on 21 August 2024). [CrossRef]

- Indraganti, M. Using the adaptive model of thermal comfort for obtaining indoor neutral temperature: Findings from a field study in Hyderabad, India. Build. Environ. 2010, 45, 519–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaka, S.; Mathur, J.; Wagner, A.; Agarwal, G.D.; Garg, V. Evaluation of thermal environmental conditions and thermal perception at naturally ventilated hostels of undergraduate students in composite climate. Build. Environ. 2013, 66, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. Going global: How humans conquered the world. New Scientist, 24 October 2007. Available online: https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg19626271-800-going-global-how-humans-conquered-the-world/ (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Melé, M.; Javed, A.; Pybus, M.; Zalloua, P.; Haber, M.; Comas, D.; Netea, M.G.; Balanovsky, O.; Balanovska, E.; Jin, L.; et al. Recombination gives a new insight in the effective population size and the history of the old world human populations. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2012, 29, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, S.T.; McClure, L.A.; Crosson, W.L.; Arnett, D.K.; Wadley, V.G.; Sathiakumar, N. Effect of sunlight exposure on cognitive function among depressed and non-depressed participants: A REGARDS cross-sectional study. Environ. Health 2009, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, S.T.; Cushman, M.; Howard, G.; Judd, S.E.; Crosson, W.L.; Al-Hamdan, M.Z.; McClure, L.A. Sunlight exposure and cardiovascular risk factors in the REGARDS study: A cross-sectional split-sample analysis. BMC Neurol. 2014, 14, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, S.T.; Howard, G.; Crosson, W.L.; Prineas, R.J.; McClure, L.A. The association of remotely-sensed outdoor temperature with blood pressure levels in REGARDS: A cross-sectional study of a large, national cohort of African-American and white participants. Environ. Health 2011, 10, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, S.T.; Kabagambe, E.K.; Wadley, V.G.; Howard, V.J.; Crosson, W.L.; Al-Hamdan, M.Z.; Judd, S.E.; Peace, F.; McClure, L.A. The relationship between long-term sunlight radiation and cognitive decline in the REGARDS cohort study. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruuhela, R.; Hiltunen, L.; Venäläinen, A.; Pirinen, P.; Partonen, T. Climate impact on suicide rates in Finland from 1971 to 2003. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2009, 53, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, A.C.; Tsai, S.J.; Huang, N.E. Decomposing the association of completed suicide with air pollution, weather, and unemployment data at different time scales. J. Affect. Disord. 2011, 129, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Walter, S.D. Seasonal variation in depressive disorders and suicidal deaths in New South Wales. Br. J. Psychiatry 1982, 140, 626–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, P.L.; Ancoli-Israel, S.; McQuaid, J. Illuminating the impact of habitual behaviors in depression. Chronobiol. Int. 2005, 22, 279–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radua, J.; Pertusa, A.; Cardoner, N. Climatic relationships with specific clinical subtypes of depression. Psychiatry Res. 2010, 175, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirz-Justice, A.; Wever, R.A.; Aschoff, J. Seasonality in freerunning circadian rhythms in man. Naturwissenschaften 1984, 71, 316–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wirz-Justice, A.; Van der Velde, P.; Bucher, A.; Nil, R. Seasonality of depression, sleep, and temperature in a student population. Biol. Psychiatry 2003, 54, 460–466. [Google Scholar]

- Premkumar, M.; Sable, T.; Dhanwal, D.; Dewan, R. Circadian levels of serum melatonin and cortisol in relation to changes in mood, sleep, and neurocognitive performance, spanning a year of residence in Antarctica. Neurosci. J. 2013, 2013, 254090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutolo, M. Rheumatoid arthritis: Circadian and circannual rhythms in RA. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2011, 7, 500–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizoue, T. Ecological study of solar radiation and cancer mortality in Japan. Health Phys. 2004, 87, 532–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W. GIS Analysis of Depression Using Location-Based Social Media Data. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA, 2015. Available online: https://openscholar.uga.edu/record/8258 (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Ayers, J.W.; Althouse, B.M.; Allem, J.P.; Rosenquist, J.N.; Ford, D.E. Seasonality in seeking mental health Information on Google. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 44, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenstein, E.G. The Laws of Migration. J. Stat. Soc. 1889, 52, 241–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobler, W. Migration: Ravenstein, Thornthwaite, and beyond. Urban Geogr. 1995, 16, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpestam, P.; Andersson, F.N. Economic perspectives on migration. In Routledge International Handbook of Migration Studies; Gold, S.J., Nawyn, S.J., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, Oxfordshire, 2013; pp. 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piguet, E.; Pécoud, A.; De Guchteneire, P. Migration and climate change: An overview. Refug. Surv. Q. 2011, 30, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeman, R. Climate and Human Migration: Past Experiences, Future Challenges; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Yu, R.; Ge, X.; Fu, J.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S. Tabular prior-data fitted network for urban air temperature inference and high temperature risk assessment. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 128, 106484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, M.; He, Y.; Diao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cui, H.; Li, C.; Lu, J.; Li, Z.; Tan, C.L. A review on hygrothermal transfer behavior and optimal design of building greenery with integrated photovoltaic systems. Energy Build. 2025, 337, 115698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiker, M.; Andersen, R.K.; Carlucci, S.; Chinazzo, G.; Hodder, S.; Mahdavi, A.; Palella, B.I.; Pisello, A.L.; Alfano, F.R.D.; Vellei, M. Ten questions concerning the usage of subjective assessment scales in research on indoor environmental quality. Build. Environ. 2025, 283, 113393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilks, D.S. Projecting “normals” in a nonstationary climate. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2013, 52, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, J.F.; Humphreys, M.A.; Roaf, S. Adaptive Thermal Comfort: Principles and Practice; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huizenga, C.; Hui, Z.; Arens, E. A model of human physiology and comfort for assessing complex thermal environments. Build. Environ. 2001, 36, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Huizenga, C.; Arens, E.; Yu, T. Considering individual physiological differences in a human thermal model. J. Therm. Biol. 2001, 26, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomaala, P.; Holopainen, R.; Piira, K.; Airaksinen, M. Impact of individual characteristics such as age, gender, BMI and fitness on human thermal sensation. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference of International Building Performance Simulation Association, Chambéry, France, 26–28 August 2013; pp. 2305–2311. Available online: https://publications.ibpsa.org/proceedings/bs/2013/papers/bs2013_2240.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2024).

- Salata, F.; Golasi, I.; Ciancio, V.; Rosso, F. Dressed for the season: Clothing and outdoor thermal comfort in the Mediterranean population. Build. Environ. 2018, 146, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhao, S.; Gao, S.; Zhang, H.; Arens, E.; Zhai, Y. Gender differences in metabolic rates and thermal comfort in sedentary young males and females at various temperatures. Energ. Build. 2021, 251, 111360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Kántor, N.; Nikolopoulou, M. Meta-analysis of outdoor thermal comfort surveys in different European cities using the RUROS database: The role of background climate and gender. Energ. Build. 2022, 256, 111757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H.; Li, B.; Chen, B.; Kosonen, R.; Jokisalo, J. Age differences in thermal comfort and physiological responses in thermal environments with temperature ramp. Build. Environ. 2023, 228, 109887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, I.M.; Reckien, D.; Reyer, C.P.; Marcus, R.; Le Masson, V.; Jones, L.; Serdeczny, O. Social vulnerability to climate change: A review of concepts and evidence. Reg. Environ. Change 2017, 17, 1651–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.L.; Hill, D.J.; Dolan, A.M.; Carnaval, A.C.; Haywood, A.M. PaleoClim, high spatial resolution paleoclimate surfaces for global land areas. Sci. Data 2018, 5, 180254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, A.W.; Sommer, C.; Kanaeva, Z.; Bolus, M.; Bruch, A.A.; Groth, C.; Haidle, M.N.; Hertler, C.; Heß, J.; Malina, M.; et al. The ROCEEH Out of Africa Database (ROAD): A large-scale research database serves as an indispensable tool for human evolutionary studies. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0289513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Dear, R.; Xiong, J.; Kim, J.; Cao, B. A review of adaptive thermal comfort research since 1998. Energ. Build. 2020, 214, 109893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höppe, P. The physiological equivalent temperature–a universal index for the biometeorological assessment of the thermal environment. Int. J. Biometeorol. 1999, 43, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, T.R.; Mills, G.; Christen, A.; Voogt, J.A. Urban Climates; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; 397p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Likert Scale | PMV-ASHRAE [6,42] | Mean Sensation Vote (MSV) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal | Humidity | Natural Lighting | ||

| 1 | Cold | Very cold | Very humid | A lot of lack of clarity |

| 2 | Cool | Cold | Humid | Lack of clarity |

| 3 | Slightly cool | Slightly cold | Slightly humid | Slight lack of clarity |

| 4 | Neutral | Comfortable | Comfortable | Comfortable |

| 5 | Slightly warm | Slightly hot | Slightly dry | Slight excess of light |

| 6 | Warm | Hot | Dry | Moderate excess of light |

| 7 | Hot | Very hot | Very dry | Too much light |

| Database | Spatial Resolution * | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Air temperature, wind speed, solar radiation | 0.1° (~11 km) | Era5-Land [47] |

| Mean radiant temperature (MRT), Universal Thermal Climate Index (UTCI) | 0.25° (~28 km) | Era5 Heat [21] |

| Relative humidity | 0.25° (~28 km) | Era5 Essential climate variables [48] |

| Cloud cover | 0.25° (~28 km) | Era5 Single levels [49] |

| Age Group | Sex | Answers | Sample Proportion | Global Proportion (Target) [50] | Weight for Bias Compensation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0–29 | Female | 516 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 1.24 |

| Male | 770 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.85 | |

| 30–44 | Female | 308 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.86 |

| Male | 415 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.62 | |

| 45–60 | Female | 203 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.91 |

| Male | 151 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 1.20 | |

| 60+ | Female | 89 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 2.07 |

| Male | 77 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 2.04 |

| Predicted Variable | Mathematical Formula |

|---|---|

| Mean temperature sensation vote | s(temperature of the month) + s(annual mean temperature) + s(humidity of the month, k = 5) + s(annual mean humidity) + s(radiation of the month) + s(annual mean radiation) + s(wind speed of the month) + binary variable of worst or best month + s(random effect of respondent id) |

| Mean humidity sensation vote | s(humidity of the month) + s(annual mean humidity, k = 4) + s(temperature of the month) + binary variable of worst or best month + s(random effect of respondent id) |

| Mean natural lighting sensation vote | s(radiation of the month) + binary variable of worst or best month + s(random effect of respondent id) |

| Predicted Variable | Sommers’ Delta |

|---|---|

| Mean temperature sensation vote | 0.69 [95% CI = 0.68–0.71] |

| Mean humidity sensation vote | 0.24 [95% CI = 0.22–0.26] |

| Mean natural lighting sensation vote | 0.52 [95% CI = 0.50–0.54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vasconcelos, V.V.; Salata, F.; Sacht, H.M.; Osaki, C.M.N.; Mendes, A.C.R.; Ferreira, C.V.M.A.; Oluwole, S.; Chaves, V.C.; Souza Filho, H.P.d. A Global Investigation of Outdoor Climatic Comfort. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121356

Vasconcelos VV, Salata F, Sacht HM, Osaki CMN, Mendes ACR, Ferreira CVMA, Oluwole S, Chaves VC, Souza Filho HPd. A Global Investigation of Outdoor Climatic Comfort. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121356

Chicago/Turabian StyleVasconcelos, Vitor Vieira, Ferdinando Salata, Helenice Maria Sacht, Camila Mayumi Nakata Osaki, Ana Carla Rizzo Mendes, Camilly Vitoria Macedo Araujo Ferreira, Solomon Oluwole, Verônica Carmacio Chaves, and Homero Pereira de Souza Filho. 2025. "A Global Investigation of Outdoor Climatic Comfort" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121356

APA StyleVasconcelos, V. V., Salata, F., Sacht, H. M., Osaki, C. M. N., Mendes, A. C. R., Ferreira, C. V. M. A., Oluwole, S., Chaves, V. C., & Souza Filho, H. P. d. (2025). A Global Investigation of Outdoor Climatic Comfort. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1356. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121356