Abstract

Rapid warming and expanding heat seasons are reshaping electricity demand in cities, with basin-type megacities like Chengdu facing amplified risks due to calm-wind, high-humidity conditions and fast-growing digital infrastructure. This study develops a Transformer-based, multi-model downscaling framework that integrates outputs from 17 CMIP6 global climate models (GCMs), dynamically re-weighted through self-attention to generate city-scale temperature projections. Compared to individual models and simple averaging, the method achieves higher fidelity in reproducing historical variability (correlation ≈ 0.98; RMSD < 0.05 °C), while enabling century-scale projections within seconds on a personal computer. Downscaled results indicate sustained warming and a seasonal expansion of cooling needs: by 2100, Chengdu is projected to warm by ~2–2.5 °C under SSP2-4.5 and ~3.5–4 °C under SSP3-7.0 (relative to a 2015–2024 baseline). Using a transparent, temperature-only Cooling Degree Day (CDD)–load model, we estimate median summer (JJA) electricity demand increases of +12.8% under SSP2-4.5 and +20.1% under SSP3-7.0 by 2085–2094, with upper-quartile peaks reaching +26.2%. Spring and autumn impacts remain modest, concentrating demand growth and operational risk in summer. These findings suggest steeper peak loads and longer high-load durations in the absence of adaptation. We recommend cost-aware resilience strategies for Chengdu, including peaking capacity, energy storage, demand response, and virtual power plants, alongside climate-informed urban planning and enterprise-level scheduling supported by high-resolution forecasts. Future work will incorporate multi-factor and sector-specific models, advancing the integration of climate projections into operational energy planning. This framework provides a scalable pathway from climate signals to power system and industrial cost management in heat-sensitive cities.

1. Introduction

Cities worldwide are increasingly exposed to intensified warming and extreme heat events, driven by the combined effects of global warming and the urban heat island (UHI) phenomenon (Seneviratne et al., 2021; Pachauri et al., 2014) [1,2]. Studies have shown that both the frequency and intensity of heat extremes have increased significantly in recent decades (Perkins-Kirkpatrick & Gibson, 2017) [3], while the urban heat island (UHI) effect amplifies climate impacts on the city scale (Arnfield, 2003) [4]. Rapid warming and extreme heat not only disrupt traditional seasonal climate patterns but also reshape the urban energy metabolism, pushing the balance between urban thermal environments and regional energy supply–demand systems toward a critical threshold (Li et al., 2020) [5].

At the same time, rapid urbanization has increased population density and industrial concentration (Grimmond, 2007; Seto et al., 2012) [6,7], while the expansion of the digital economy has led to soaring cooling demand from server clusters and air-conditioning systems, creating “hidden load spikes” in power systems (Auffhammer & Mansur, 2014) [8]. To ensure stable operations, enterprises have increasingly deployed distributed storage and backup generation. However, such ad hoc measures often exacerbate voltage fluctuations and power flow instability in distribution networks, thereby heightening systemic risks (Davis & Gertler, 2015) [9]. This reality underscores the urgent need for high-resolution climate projections and demand-side management strategies to address the dual challenges of energy and climate stress in cities under global climate change.

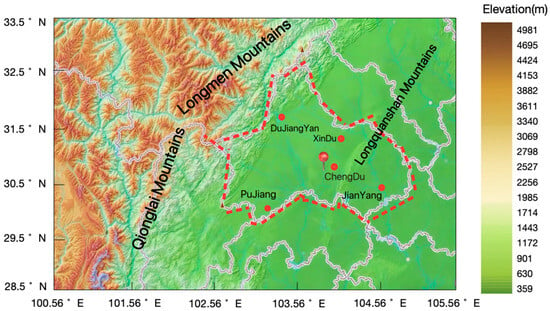

As a typical inland basin city, Chengdu is characterized by calm-wind and high-humidity climatic conditions that exacerbate the UHI effect far more than in most comparable regions. Geographically, Chengdu is located in the western Sichuan Plain (Chengdu Plain), enclosed by complex mountainous terrain—bounded by the Longmen Mountains to the northwest, the Longquan Mountains to the east, and the Qionglai Mountains to the west (Figure 1). This semi-enclosed topography restricts horizontal air circulation and promotes heat and moisture accumulation, especially during summer (Yang et al., 2025) [10]. The relatively low elevation of the basin floor contrasts sharply with the surrounding mountain ranges exceeding 4000 m, creating strong thermal inversions that suppress convective exchange. These features jointly contribute to Chengdu’s persistently stagnant boundary layer, limited ventilation capacity, and elevated nighttime temperatures, which further intensify extreme heat events and amplify cooling energy demand (Liu et al., 2018) [11].

Figure 1.

Topography of the Chengdu Plain and surrounding mountain systems.

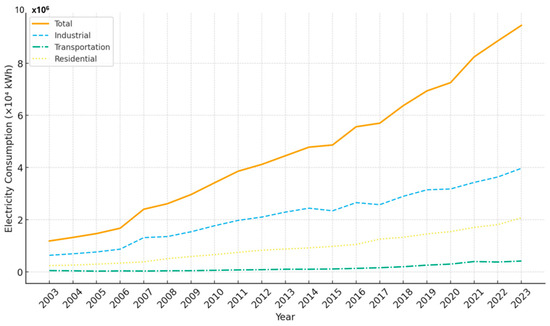

Multi-source remote sensing and ground observations indicate that Chengdu’s UHI index can reach 3.4 °C (Yang et al., 2025) [10]. According to the Chengdu Statistical Yearbook (Chengdu Bureau of Statistics, 2024) [12], between December 2022 and November 2023 the city recorded 180 station-days of high-temperature events (≥35 °C), including three concentrated heatwave episodes in mid-to-late July (8–10, 16–18, and 22–23 July), with single-day extremes exceeding 37 °C. Long-term analyses reveal that over the past decade the frequency of extreme heat events in Chengdu increased by 37%, with the number of ≥35 °C days more than doubled (2.1 times) compared to the pre-2010 period. In 2022, Chengdu reached an unprecedented 43.4 °C, setting a new heat record for the Sichuan Basin and underscoring the intensification of climate system instability. Meanwhile, Chengdu is rapidly expanding as the core hub of China’s digital economy pilot zone, developing a national computing center, trillion-yuan electronic information clusters, and an AI innovation zone. The surge in electricity demands associated with this industrial expansion, compounded by the city’s basin-induced stagnant meteorological conditions, further exacerbates thermal stress and imposes mounting challenges on the stability of the regional power system (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Chengdu’s electricity consumption, including total consumption and its sectoral components (Unit: 10,000 kilowatt-hours (kWh)).

Faced with the dual pressures of increasingly frequent extreme heat events and rising energy demand, Chengdu’s reliance on high-resolution climate projections has become more critical than ever. However, existing climate modeling tools are insufficient to meet this need. Although global climate models (GCMs) such as CMIP6 provide valuable insights into long-term climate trends, their coarse spatial resolution makes them inadequate for capturing city-scale extreme heat events (Eyring et al., 2016) [13]. In addition, systematic biases in individual models and the spread of results across models introduce considerable uncertainty for regional risk assessments (Knutti & Sedláček, 2013) [14]. Thus, effectively integrating multi-model outputs and enhancing regional predictive capacity through downscaling has become a central challenge in climate and energy research (Giorgi & Mearns, 1999; Maraun & Widmann, 2018) [15,16].

Previous studies have shown that regional climate models (e.g., WRF) can provide higher-resolution simulations at the regional scale, but their application at sub-kilometer resolutions (<1 km) is limited by severe computational costs (Giorgi, 2019) [17]. In climate-sensitive cities like Chengdu, robust assessment of extreme heat risks requires long-term projections from multi-model ensembles, yet dynamical downscaling methods such as WRF are prohibitively expensive for systematic ensemble downscaling of multiple CMIP6 models (Liu et al., 2018) [11]. This limitation restricts the practical usability of high-resolution projections and constrains their integration into regional energy risk assessment and planning.

In this study, climate-sensitive cities refer to urban areas whose energy demand and environmental stress are highly responsive to climate variability and extremes. Such cities exhibit strong coupling between atmospheric conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity, and wind) and urban systems, meaning that even moderate changes in climate can lead to substantial variations in electricity demand, air quality, and heat-related risks. Chengdu, with its basin-constrained topography and high-humidity environment, is a representative example of a climate-sensitive city.

In Chengdu, the lack of ensemble-based high-resolution predictions is particularly consequential. First, climate change amplifies the nonlinearity of extreme weather events, making single-model projections unreliable for capturing trends (Knutti & Sedláček, 2013) [14]. Second, the growing penetration of renewable energy has intensified uncertainties on both the supply and demand sides; without high-precision forecasts, risks such as increased electricity procurement costs, wasted capacity, elevated carbon emissions, and unplanned outages are magnified (IEA, 2022; Lund et al., 2017) [18,19]. As a result, electricity demand forecasting in Chengdu has shifted from being a purely technical challenge to a strategic economic concern. Leveraging advanced machine learning algorithms to enhance climate projection accuracy while integrating results into grid balancing and corporate energy cost management has therefore become a key pathway to reconciling the contradictions between climate crisis and digital urbanization (Duchesne et al., 2020; Rolnick et al., 2022) [20,21].

This study proposes the use of advanced machine learning algorithms to efficiently downscale and optimally combine outputs from multiple Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) models, thereby addressing the computational and efficiency bottlenecks of traditional dynamical downscaling for localized analysis (Reichstein et al., 2019) [22]. This approach enables the rapid generation of high-resolution future temperature projections for Chengdu, offering practical support for forecasting electricity demand and managing energy costs in corporate settings. This work uses Chengdu as a representative case, with a focus on translating large-scale climate data into local projections. By incorporating Chengdu’s distinct warming trends, the study develops a targeted framework for assessing future electricity demand driven by rising temperatures. Through the integration of climate science, machine learning methods, and electricity demand analysis, this study explores a cross-disciplinary pathway from theoretical models and algorithms to industrial applications. Looking ahead, the methodology established here can be extended to other climate-sensitive cities and industrial contexts, thereby promoting the integration of climate prediction with industrial resilience management and providing replicable solutions for broader low-carbon transitions and sustainable socio-economic development.

2. Data and Methods

Data

This study utilizes long-term in situ meteorological observations from the Shuangliu Station, representing historical meteorological conditions in the Chengdu region. The data were retrieved from the Global Surface Summary of the Day (GSOD) dataset maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). GSOD provides standardized daily observations of key variables such as air temperature, wind speed, humidity, and precipitation collected from global weather stations. To the best of our knowledge, the Shuangliu station dataset is the only publicly accessible, long-term in situ meteorological record (1973-present) available for Chengdu, making it an essential source for assessing local climate variability and trend analysis.

In addition to meteorological data, we also collected electricity consumption data for Chengdu from the Chengdu Statistical Yearbooks (Chengdu Bureau of Statistics, 2024) [12]. The dataset includes key indicators such as electricity load, industrial distribution, and energy consumption characteristics. In this study, our primary focus is on developing and quantifying the relationship between rising temperatures and Chengdu’s total electricity demand, with particular attention to how warming trends and extreme heat events shape load variations across different warming scenarios.

Climate Scenarios

This study used multi-model ensemble outputs from CMIP6. Coordinated by the World Climate Research Programme, CMIP6 (Eyring et al., 2016) [13] represents one of the most authoritative and widely applied climate model ensembles to date, and its results provided the scientific foundation for the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) (IPCC, 2023). Compared with its predecessors, CMIP6 models feature enhanced spatial resolution and improved representation of physical and biogeochemical processes, along with new scenario frameworks (SSPs; O’Neill et al., 2016) [23], making them better suited for regional analysis (Tebaldi et al., 2021) [24].

We selected 17 CMIP6 GCMs (Table 1) developed by institutions across Europe, North America, and Asia, to ensure diversity and robustness in the ensemble projections. These models differ in their dynamical frameworks, parameterization schemes, and initial conditions, thereby offering a comprehensive representation of uncertainty in future climate projections.

Table 1.

The selected CMIP6 GCMs.

Two socio-economic pathways were considered in this study:

- SSP2-4.5 represents a “medium stabilization” pathway, assuming moderate mitigation policies, medium population and economic growth, and a gradual transition toward low-carbon energy. Under this scenario, global warming is partially constrained, making it suitable for assessing relatively moderate climate risks.

- SSP3-7.0 represents a “regional rivalry” pathway, characterized by weak international cooperation, rapid population growth, and continued reliance on fossil fuels, leading to sustained medium-to-high levels of greenhouse gas emissions. This scenario reflects the potential high-risk conditions that climate-sensitive cities may face in terms of extreme heat and energy system stress. Note that only 14 models were available for this scenario. Results from GFDL-CM4, EC-Earth3-HR, and NESM3 under SSP3-7.0 were not available at the time of this study.

We used CMIP6 outputs for the period 2015–2100 and analyzed two representative future time slices—the mid-century (2050s) and the late century (2090s)—to capture the long-term trajectory of warming risks under different emission scenarios and to assess their potential impacts on summer cooling demand. The use of mid- and late-century periods is a standard practice in climate impact assessments, as it allows evaluation of both near- to medium-term adaptation challenges and long-term risks under sustained climate change.

Machine Learning

The Transformer architecture, originally proposed by Vaswani et al. (2017) [25], leverages the self-attention mechanism to effectively capture dependencies across long sequences and has achieved remarkable success in natural language processing. Compared with recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and convolutional neural networks (CNNs), Transformers provide stronger parallelization and greater flexibility in modeling long-term dependencies. In recent years, they have been increasingly applied in climate science, particularly in tasks such as weather prediction, climate model bias correction, and multi-source data fusion (Dosovitskiy et al., 2020; Nguyen et al., 2023; Chen and Xue, 2025) [26,27,28]. These developments highlight the potential of Transformer-based models as powerful tools for downscaling and improving the accuracy of regional climate projections.

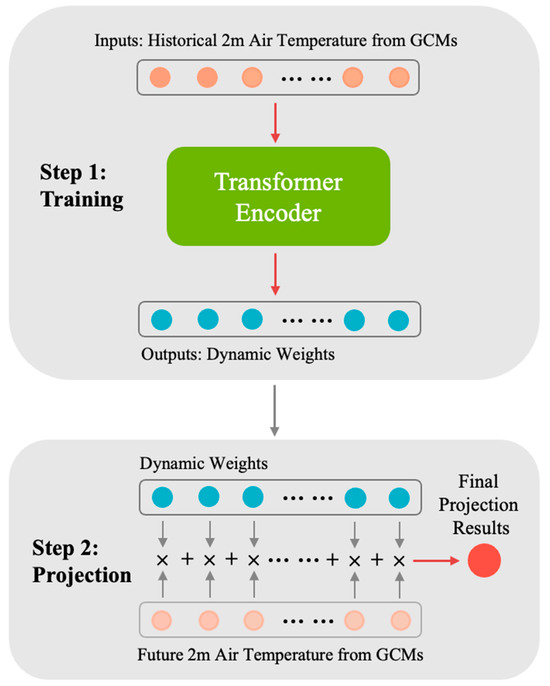

In this study, we implemented a Transformer-based downscaling framework using the standard PyTorch library (https://docs.pytorch.org/docs/stable/generated/torch.nn.TransformerEncoderLayer.html, accessed on 6 July 2025). As illustrated in Figure 3, at each time step the input vector, consisting of outputs from CMIP6 models, is processed by a Transformer encoder that generates a set of time-varying weights through multi-head self-attention. These weights are then used to compute a weighted sum of the inputs, yielding the final ensemble projection.

Figure 3.

The structure of transformer-based downscaling.

To prepare the inputs, we first obtained 2 m air temperature outputs from multiple GCMs with varying native spatial resolutions at the global scale. We then extracted the subset covering the domain 25–35° N, 96–110° E, which encompasses Sichuan Province. Using the Python function scipy.interpolate.griddata (accessed on 6 July 2025), the GCM data were linearly interpolated to the coordinate point (30.67° N, 104.06° E), representing Chengdu. This approach ensures consistent data alignment across models while maintaining regional representativeness. Prior to model training, all data, including in situ observations, were smoothed using a 10-year moving average to preserve long-term climatic trends and variability while filtering out short-term fluctuations (Huang et al., 2021; Chen and Xue, 2025) [28,29]. Compared with static averaging, this approach adaptively adjusts model weights, captures the dynamic features of extreme heat events, and significantly improves computational efficiency over dynamical downscaling, thereby making quick long-term projection feasible. The historical data was divided into two subsets: data from 2001 to 2004 were reserved as an independent testing dataset to evaluate model performance after training, while the remaining data were used for training (90%) and internal validation (10%) during model development.

Heat–Electricity demand relationship

Under global warming conditions, temperature is the most direct and significant meteorological driver of electricity load. Electricity demand is highly sensitive to climatic conditions, particularly temperature extremes. The most widely used climate indicators are degree days, defined relative to a baseline temperature. Cooling Degree Days (CDD) measure the intensity of cooling needs when temperatures exceed the baseline, while Heating Degree Days (HDD) capture heating requirements when temperatures fall below it (NOAA, 2023) [30]. These indicators have been extensively applied in electricity demand forecasting and energy–climate impact studies.

Many studies in energy economics employ either log-linear models, where electricity consumption enters natural logarithms (Fan et al., 2019; Hou et al., 2022) [31,32], or linear specifications (Pardo et al., 2002; Ding, 2007) [33,34]. For Chengdu’s cooling-dominated context, this study adopts a linear model (Ding, 2007) [34]. This choice allows the results to be directly interpreted as incremental changes in electricity demand per additional unit of CDD, which is particularly valuable for engineering applications, peak demand assessments, and cost analysis. Moreover, the linear formulation provides a transparent link between climatic variability and electricity consumption, facilitating its integration into energy system planning and risk assessment.

The daily CDD, (°C), is defined as:

where denotes the daily mean temperature at a given day d, and is a reference temperature. °C is used, similar to Cao et al. (2023) [35]. With focus of CDD-induced electricity demand, daily electricity demand (M kWh day−1) is then regressed on CDD:

Here, (M kWh day−1) represents the baseline load without cooling demand, while (M kWh day−1 °C−1) captures the marginal increase in electricity load per additional cooling degree day. (M kWh day−1) represents the combined effects of unobserved or omitted factors such as short-term fluctuations in consumer behavior, industrial activities, holiday effects, price shocks, measurement errors, and other stochastic influences.

In this study, is set to 120 M kWh day−1, representing Chengdu’s average daily baseline electricity consumption under neutral temperature conditions (i.e., CDD = 0), derived from the averaged total consumption from 2013 to 2023 (Figure 2) converted to a daily scale. The coefficient is calibrated as 10 M kWh day−1 °C−1, indicating that each additional cooling degree day increases the city’s total daily electricity demand by approximately 8–10% relative to the baseline. These values are consistent with reported seasonal load variations in major inland cities of China (Ding et al., 2007) [34] and serve as a conservative yet realistic representation of Chengdu’s cooling-sensitive electricity demand.

Given that the frequency of extreme heat events varies across climate scenarios, we estimated seasonal changes in total CDD under SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0 for Chengdu, and translated these changes into projected increments in electricity demand. Although simplified, this model offers computational efficiency, strong interpretability, and reasonable quantification of heat impacts on electricity demand.

3. Results

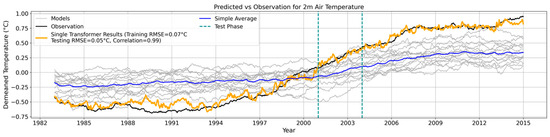

3.1. Model Validation

Figure 4 illustrates the comparison between simulated and observed 10-year moving average air temperatures for the historical period (1983–2014). The individual GCMs exhibit large variability, and their simple average deviates substantially from the observations (black line), generally overestimating temperature before 2000 and underestimating temperature afterwards and failing to capture the amplitude of both warming and cooling phases. In contrast, the Transformer-based downscaling closely matches the observations. More importantly, it not only reproduces the long-term trend in the training phase but also performs consistently well during the testing period (2001–2004), achieving notably lower root mean square errors (RMSE). The Transformer framework attains a testing RMSE of 0.07 °C. These results demonstrate that the Transformer framework substantially enhances the fidelity of historical climate reproduction compared to conventional ensemble-averaging methods.

Figure 4.

Comparison of 10-year moving average of 2 m air temperature downscaled at Chengdu among individual GCMs (gray), their simple average (SA; blue), Transformer-based downscaling (yellow), and in situ observations (black).

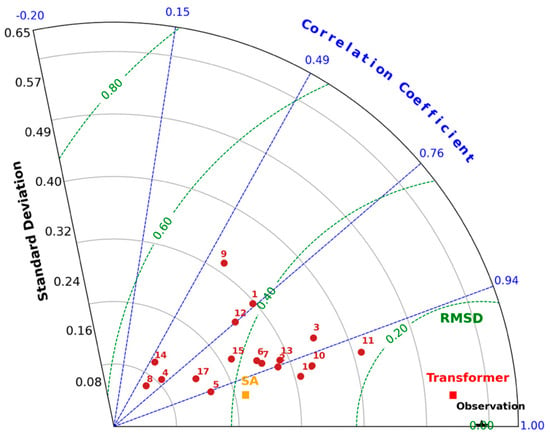

The Taylor diagram (Taylor, 2001) [36] reinforces the superior performance of Transformer-based downscaling. Figure 5 shows that individual CMIP6 models exhibit substantial discrepancies in simulating 2 m air temperature over Chengdu. Most of the models significantly underestimate the observed standard deviation (0.58 °C), and their root-mean-square differences (RMSD) are typically greater than 0.2 °C, reflecting systematic biases in reproducing observed long-term temperature variability. In addition, conventional ensemble methods such as simple averaging (SA) reduce inter-model spread but still display notable deviations from observations. By contrast, the proposed Transformer-based downscaling method outperforms both individual GCMs and SA across all key metrics, including standard deviation, RMSD, and correlation coefficient. In particular, its correlation with observations reaches 0.98 and its RMSD is less than 0.05 °C, indicating much higher fidelity in capturing historical temperature evolution. These results underscore the advantages of the Transformer framework, which dynamically adjusts model weights through self-attention, effectively overcoming the limitations of static averaging and providing a more reliable approach for regional climate projections. Overall, the Transformer approach not only aligns more closely with observations in terms of statistical consistency but also outperforms all benchmark methods in overall accuracy, offering a robust foundation for regional warming projections.

Figure 5.

Taylor diagram showing the performance of individual GCMs, their simple average (SA), and Transformer-based downscaling for the historical period (1983–2015).

3.2. Projected Temperature Changes

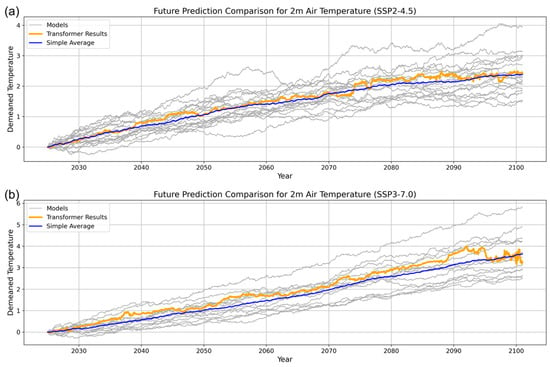

Figure 6 compares future downscaled 10-year moving average of 2 m air temperature projections from our Transformer-based model (orange lines) with the ensemble of CMIP6 models (gray lines). Under SSP2-4.5, the temperature anomaly shows a steady upward trend, increasing by approximately 1.0–1.5 °C relative to the baseline in 2050s and reaching 2–2.5 °C in 2090s. Under the higher-emission SSP3-7.0 pathway, warming is more pronounced, reaching 3–4 °C in 2090s, while remaining similar to SSP2-4.5 in 2050s. Despite a larger inter-model spread under this scenario, the Transformer predictions remain closely aligned with the central tendency, demonstrating robustness in capturing long-term warming trajectories while reducing variance compared with individual GCM outputs. Overall, the Transformer-based downscaling not only provides superior historical fits but also delivers credible projections of future warming.

Figure 6.

Future projections of 10-year moving average of 2 m air temperature anomalies (relative to the baseline of 2015–2024) under two emission scenarios: SSP2-4.5 (a) and SSP3-7.0 (b).

3.3. Projected Cdd Changes and Its Impact on Electricity Demand

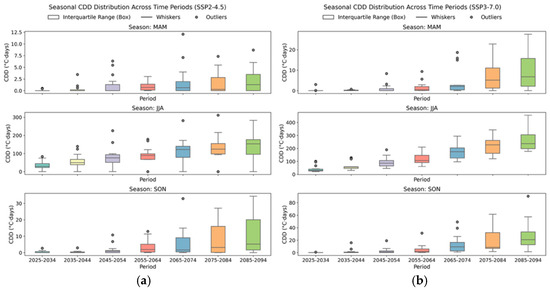

Figure 7 illustrates the projected seasonal evolution of CDD across different future periods under two climate scenarios, SSP2-4.5 (panel a) and SSP3-7.0 (panel b). Under SSP2-4.5, all three seasons (MAM, JJA, and SON) show a gradual increase in CDD over the course of the 21st century. The strongest increase is observed during boreal summer (JJA), where the interquartile range expands significantly after mid-century, indicating both a robust rise in cooling demand and greater variability across ensemble members. In spring (MAM) and autumn (SON), the upward trend is more moderate but still evident, with CDD values in the late 21st century approximately two to three times higher than those in the early 21st century. The widening whiskers and the increasing number of outliers also reflect the potential for more frequent and intense extreme heat events driving higher seasonal cooling requirements.

Figure 7.

Seasonal distribution of CDD across future time periods under (a) SSP2-4.5 and (b) SSP3–7.0. Box plots show the interquartile range (box), whiskers (minimum–maximum excluding outliers), and outliers (dots).

In contrast, SSP3-7.0 produces markedly larger increases in CDD across all seasons, highlighting the amplified impact of higher greenhouse gas emissions. During JJA, median CDD values approach 260 °C·days by the late 21st century, far exceeding those under SSP2-4.5, signaling heightened risk of extreme cooling demand. Spring and autumn also show substantially elevated CDD, with late-century distributions shifting upward and extending toward higher extremes. Notably, under SSP3-7.0, the seasonal shifts are not only stronger but also more variable (note the different y-axis ranges), suggesting that the intensity and frequency of cooling requirements will rise disproportionately under a higher-emissions trajectory. Together, these results underscore the critical importance of considering scenario uncertainty in energy system planning, as cooling demand is projected to escalate significantly under both pathways, with particularly severe implications under SSP3-7.0.

Table 2 summarizes the seasonal evolution of CDD-induced electricity demand as normalized ratio relative to the 2025–2034 baseline (values of 1.00 indicate no change), reported by the 25th percentile (P25), median (P50), and 75th percentile (P75) across ensemble members for successive future periods and two scenarios. The results indicate that summer (JJA) is the dominant season for demand growth. Under SSP2-4.5, the median (P50) summer demand increases by +2.1% in 2025–2034 and rises steadily to +12.8% by 2085–2094, with the upper quartile (P75) reaching +15.2%. Under the higher-emission SSP3-7.0 scenario, the increase is more pronounced: median summer demand grows from +1.6% to +20.1%, while the P75 values rise to +26.2% in the late century. In contrast, spring (MAM) and autumn (SON) exhibit only marginal changes, generally within the range of 0–2%, suggesting that the CDD-driven load increase is predominantly concentrated in summer. These findings highlight that future climate warming will substantially intensify summer peak load pressures, particularly under high-emission pathways, thereby underscoring the need for enhanced system flexibility and resilience. Importantly, the increasing variability suggests not only higher annual averages but also more intense demand peaks and longer durations of elevated loads during extreme heat events. Together, these findings imply that Chengdu’s power system will face substantially greater challenges in peak load management and cost control over the coming decades.

Table 2.

CDD-induced electricity demand increases ratio relative to the 2015–2024 baseline for successive future periods under SSP2–4.5 and SSP3–7.0. Values > 1 denote increases relative to baseline.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates the clear advantages of a Transformer-based deep learning framework for multi-model integration and downscaling. Compared with conventional ensemble averaging, the Transformer adaptively adjusts model weights through self-attention, thereby reducing systematic biases in individual models and enhancing overall predictive skill. The results indicate that the Transformer achieves correlation coefficients close to 1, standard deviations highly consistent with observations, and very low RMSD than individual prediction and their SA (Figure 3), confirming its robustness in reproducing historical climate variability.

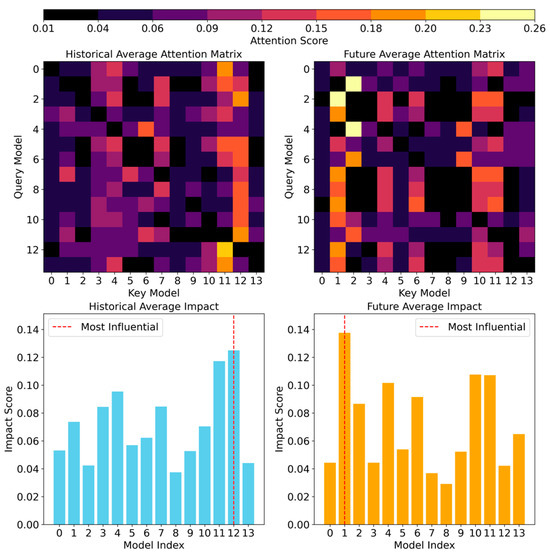

Figure 8 visualizes the Transformer’s internal attention structure, highlighting how the model dynamically assigns importance to different GCM inputs during both the historical and future periods. The attention matrices (top panels) reveal that the learned relationships among models are not uniform: certain GCMs consistently receive higher attention scores, indicating stronger influence in determining the ensemble prediction. In the historical period, attention seems more evenly distributed, reflecting comparable reliability among models. In contrast, under future conditions the attention map becomes more polarized, with several models receiving distinctly higher scores, suggesting that the Transformer adaptively emphasizes models that better capture the evolving temperature signal under stronger forcing scenarios. The impact bars (bottom panels) further quantify this shift, showing that the most influential models change from Index 12 in the historical stage to Index 0 in the future stage. This dynamic re-weighting demonstrates the framework’s capacity to learn temporal dependencies and adjust inter-model trust as climate variability and extremes intensify, which is an ability that static multi-model averaging cannot reproduce.

Figure 8.

The Transformer’s internal attention map averaged over the historical and future periods under SSP3-7.0 scenario as an example, showing how the model dynamically assigns importance to different GCM inputs.

In addition, it is important to note that it should not be interpreted as attention values represent GCM reliability. Rather, Figure 8 shows that the attention mechanism in our Transformer framework allows the model to dynamically adjust the weighting of each GCM during the ensemble computation. These weights reflect the model’s learned contextual importance in reconstructing the target temperature sequence, not a deterministic measure of GCM performance or credibility.

In addition, relative to computationally expensive dynamical downscaling methods such as WRF, the Transformer achieves century-scale projections in less than one second on a personal computer, following a training procedure that requires approximately six hours on a workstation. This dramatic gain in efficiency makes systematic ensemble downscaling of multiple CMIP6 models not only feasible but also practical. Such methodological innovation provides a powerful and economical pathway for long-term climate risk assessment at regional and urban scales, with particular promise for data-scarce or resource-limited regions.

In China, recent studies have demonstrated the growing significance of Cooling Degree Days (CDDs) as an indicator of rising electricity demand under a warming climate. For example, Cao et al. (2023) [35] reported that the number of CDDs has increased markedly across major climate zones over the past five decades, consistent with observed warming trends, underscoring the utility of CDDs in capturing long-term shifts in cooling energy requirements. Similarly, Ding (2007) [34] analyzed multi-decade observations in Beijing and identified a quantitative relationship between CDDs and electricity load—showing that the mean monthly maximum CDD in July reached 259.2 degree days, with a clear upward trend that reinforces the explanatory power of CDDs in load forecasting.

Consistent with these findings, our projections indicate that under both SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0 scenarios, electricity demand increases substantially, but with notable differences in magnitude. This finding underscores how global mitigation pathways will directly shape the load levels and operational risks of Chengdu’s power system. The rise in electricity demand is reflected not only in higher annual averages but also in more intense peaks and longer durations of elevated load, particularly during summer. This dual challenge—higher short-term peaks and sustained high demand—highlights the increasing stress that extreme heat imposes on electricity systems, consistent with recent studies linking climate extremes to rising cooling loads (Auffhammer et al., 2017) [37].

For Chengdu, with its concentration of electronics, manufacturing, and AI industries, unmanaged risks could threaten industrial stability and regional economic growth. As a basin city, Chengdu’s stagnant and humid atmospheric conditions hinder heat dissipation, amplifying the impact of high temperatures on cooling demand. At the same time, the rapid expansion of its electronics and digital economy sectors has intensified cooling and heat-dissipation needs, further magnifying the combined effects of climate change and industrial development (Chen et al., 2011) [38]. Compared with northern Chinese cities, Chengdu exhibits stronger temperature sensitivity in electricity demand growth (Li et al., 2019; Kang et al., 2022) [39,40], while unlike coastal megacities in the Yangtze River and Pearl River Deltas, Chengdu lacks maritime regulation, resulting in more pronounced accumulation of extreme heat stress. This suggests that energy planning and climate adaptation strategies cannot simply borrow from other regions but must account for the distinct vulnerabilities of basin-type cities (Liu et al., 2018) [11].

The Chengdu case therefore not only highlights the complexity of urban climate–energy interactions but also offers valuable insights for cities with similar geographic and industrial profiles (e.g., Chongqing, Wuhan, Bangkok), underscoring the importance of integrating regional climate projections with industrial development strategies. The findings suggest that Chengdu’s power system must prepare proactively for rising electricity demand driven by surging heat. At the grid level, investments should prioritize peak-shaving capacity, energy storage, and coordinated operation of demand response with distributed energy resources to enhance system flexibility and resilience (Lund et al., 2017; Thornbush and Golubchikov, 2021) [19,41]. At the enterprise level, firms could leverage high-resolution climate forecasts to optimize production scheduling and energy procurement strategies, thereby reducing additional costs and avoiding unplanned outages during heatwaves (Auffhammer et al., 2017) [37]. At the governmental level, climate projections should be incorporated into energy strategies and urban adaptation policies, promoting structural optimization and low-carbon transitions while strengthening overall risk management capacity (IPCC, 2022). These implications extend beyond Chengdu and provide valuable references for other climate-sensitive cities, particularly those experiencing rapid urbanization alongside increasing risks from extreme heat.

Although the Transformer-based downscaling framework demonstrates effective applicability for Chengdu’s warming and electricity demand projections, the results remain subject to several sources of uncertainty. First, the climate system’s inherent nonlinearity and multi-scale disturbances make it difficult for current models to fully capture the intensity and frequency of future extremes. Second, delays in aligning policies and market instruments hinder the timely translation of climate forecasts into actionable energy dispatch and corporate strategies. Finally, multiple unresolved factors can introduce additional uncertainties, while energy transformation remains constrained by path dependence and cost barriers, potentially limiting effective climate risk adaptation.

Future research should therefore strengthen the integration of climate prediction with policy development and corporate decision-making. On one hand, predictive models need to incorporate multiple meteorological factors—such as temperature, humidity, wind speed, and radiation—to more accurately represent combined heat stress (Budd 2008; Di Napoli et al., 2019; Buzan and Huber, 2020) [42,43,44]. On the other hand, policy frameworks should adopt climate resilience as a core principle, embedding dynamic climate risk governance into energy and industrial planning (Buhl et al., 2023; Kalogiannidis et al., 2024) [45,46]. At the enterprise level, instruments such as green finance and supply-chain coordination can help lower transition costs, enabling a shift from passive exposure to proactive value creation (Billio et al., 2024) [47].

Adaptive needs are evident in three dimensions. First, differentiated continuity requirements across industries highlight the necessity of establishing tiered resilience standards. Second, resilience is evolving from single-grid resistance toward multi-energy complementarity and cross-regional coordination, thereby enhancing buffering capacity. Third, resilience enhancement requires a “dual drive” of hard technologies and soft mechanisms, combining cutting-edge tools such as machine learning forecasts and virtual power plants with institutional linkages between climate risks, market signals, and policy incentives. This integrated approach enables power systems to transition from short-term emergency response to long-term sustainable resilience management.

As the core city of the Chengdu–Chongqing urban agglomeration, Chengdu’s energy resilience is crucial not only for local industrial development but also for the broader national strategic framework (NDRC Regional Development Institute, 2016) [48]. The findings of this study suggest that adaptive capacity should be reinforced through spatial planning optimization and the design of innovative policy instruments, thereby ensuring the alignment of climate resilience with regional development objectives.

On the spatial planning side, machine learning-based downscaled projections of extreme heat can guide the siting and layout of key industrial zones. For example, avoiding heat island cores and incorporating ventilation corridors and green buffer zones can significantly reduce local thermal loads, decrease cooling-related energy consumption, and indirectly lower corporate operational costs (Wang et al., 2024) [49]. On the energy policy side, efforts should accelerate the development of coordinated “source–grid–load–storage” systems, expand distributed PV and storage deployment, and mainstream virtual power plants (VPPs) with integrated demand response mechanisms (Chengdu Planning and Design Institute, 2022) [50]. More than 200 major electricity users in Chengdu have already joined VPP platforms, which have proven effective in reducing peak electricity costs while enhancing grid flexibility and stability. Looking ahead, dual-track incentives that combine demand response with PV-storage deploymLund, H.ent could further broaden participation and advance the low-carbon, intelligent upgrading of the regional energy system.

While this study focuses on city-scale validation using in situ observations, we recognize the complementary value of homogenized and gridded datasets-based ones such as CN05.1 and reanalysis products such as ERA5. These datasets provide spatially continuous and internally consistent representations of regional climate variability and are particularly suitable for basin- or province-scale assessments, trend analyses, and regional energy–climate coupling studies. However, their coarse spatial resolution (≈0.25°) and interpolation or assimilation procedures inherently smooth out local features, was not designed for resolving local city-scale variability. Therefore, the present analysis employs station-based observations to preserve the fine-scale variability that is central to city-level climate adaptation and planning. Future work could extend this framework to incorporate CN05.1 or ERA5 data for multi-scale evaluation of regional energy demand and climate sensitivity.

5. Conclusions

This study addresses the practical challenge of projecting city-scale extreme heat and the computational bottlenecks of dynamical downscaling by introducing a Transformer-based multi-model ensemble framework that efficiently integrates outputs from 17 CMIP6 models for Chengdu. Coupled with a simple and interpretable CDD–load model, this approach quantifies the implications of regional warming for the power system. Compared with individual GCM projection and their SA, the Transformer-based downscaling achieves higher correlations, lower RMSD, and observation-consistent variance during the historical period, while substantially reducing the cost and complexity of long-horizon multi-model projections. These results demonstrate the framework’s clear methodological value for operational regional climate applications.

Scenario results indicate sustained warming and an expansion of the shoulder seasons under both SSP2-4.5 and SSP3-7.0. On the electricity side, this translates into steady yet scenario-divergent demand growth. Beyond higher annual means, the steepening demand curves imply higher peaks and longer durations of elevated load, underscoring the critical role of peaking capacity, storage, and demand response in sustaining urban power systems.

Our load linkage is primarily temperature-driven (CDD-based) and does not yet explicitly incorporate humidity, radiation, wind, or sectoral heterogeneity; therefore, portability to other climates requires recalibration of thresholds and parameters. Future work will pursue (i) multi-factor and distributed-lag responses to better capture heat extremes, (ii) sector-specific load modeling to enhance policy and enterprise relevance, and (iii) cross-city deployment with operational integration, embedding the pipeline into power system and urban-planning workflows to close the forecast–decision–evaluation loop.

Overall, this study provides a scalable, interpretable, and actionable pathway: employing Transformer architectures to overcome ensemble downscaling bottlenecks, translating climate signals into energy-side impacts through a parsimonious load–temperature relationship, and converting projections into concrete guidance for grid resilience and industrial cost management. This paradigm delivers replicable evidence and methodological tools to support planning and governance in climate-adaptive modern cities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.Y.; methodology, R.Y. and writing—original draft preparation, R.Y. and G.T.; writing—review and editing, R.Y. and G.T. funding acquisition, R.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Chengdu Municipal Foundation for Philosophy and Social Science grant number 2025ZX12, and Sichuan Provincial Social Science Fund Commissioned Project grant number SCJJ25RKX083.

Data Availability Statement

The long-term in situ meteorological observations from the Shuangliu Station were retrieved from the Global Surface Summary of the Day (GSOD) dataset maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) from: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/search/data-search/global-summary-of-the-day (accessed on 6 July 2025) CMIP6 data was available from World Climate Research Program: https://esgf-ui.ceda.ac.uk/cog/search/cmip6-ceda/ (accessed on 6 July 2025).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our family and partners for their support, anonymous reviewers for their valuable revision suggestions, and journal editors for their efficient handling and professional oversight.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GCM | global climate models |

| CDD | Cooling Degree Days |

| CMIP6 | Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 |

| HDD | Heating Degree Days |

| MAM | March, April, May |

| JJA | June, July, August |

| SON | September, October, November |

References

- Seneviratne, S.I.; Zhang, X.; Adnan, M.; Badi, W.; Dereczynski, C.; Luca, A.D.; Ghosh, S.; Iskandar, I.; Kossin, J.; Lewis, S.; et al. Weather and climate extreme events in a changing climate. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Masson-Delmotte, V.P., Zhai, A., Pirani, S.L., Connors, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 1513–1766. [Google Scholar]

- Pachauri, R.K.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pachauri, R., Meyer, L., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; 151p, ISBN 978-92-9169-143-2. [Google Scholar]

- Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S.E.; Gibson, P.B. Changes in regional heatwave characteristics as a function of increasing global temperature. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnfield, A.J. Two decades of urban climate research: A review of turbulence, exchanges of energy and water, and the urban heat island. Int. J. Climatol. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2003, 23, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zha, Y.; Wang, R. Relationship of surface urban heat island with air temperature and precipitation in global large cities. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimmond, S.U.E. Urbanization and global environmental change: Local effects of urban warming. Geogr. J. 2007, 173, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Güneralp, B.; Hutyra, L.R. Global forecasts of urban expansion to 2030 and direct impacts on biodiversity and carbon pools. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 16083–16088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auffhammer, M.; Mansur, E.T. Measuring climatic impacts on energy consumption: A review of the empirical literature. Energy Econ. 2014, 46, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.W.; Gertler, P.J. Contribution of air conditioning adoption to future energy use under global warming. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 5962–5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Lin, Z.; Li, Q. Quantitative Simulation and Planning for the Heat Island Mitigation Effect in Sponge City Planning: A Case Study of Chengdu, China. Land (2012) 2025, 14, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tian, G.; Feng, J.; Wang, J.; Kong, L. Assessing summertime urban warming and the cooling efficacy of adaptation strategy in the Chengdu-Chongqing metropolitan region of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 610, 1092–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chengdu Bureau of Statistics. Chengdu Statistical Yearbooks 2003–2024; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Eyring, V.; Bony, S.; Meehl, G.A.; Senior, C.A.; Stevens, B.; Stouffer, R.J.; Taylor, K.E. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model. Dev. 2016, 9, 1937–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knutti, R.; Sedláček, J. Robustness and uncertainties in the new CMIP5 climate model projections. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 369–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgi, F.; Mearns, L.O. Introduction to special section: Regional climate modeling revisited. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 1999, 104, 6335–6352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraun, D.; Widmann, M. Statistical Downscaling and Bias Correction for Climate Research; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, F. Thirty years of regional climate modeling: Where are we and where are we going next? J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2019, 124, 5696–5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2022; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Lund, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Connolly, D.; Mathiesen, B.V. Smart energy and smart energy systems. Energy 2017, 137, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesne, L.; Karangelos, E.; Wehenkel, L. Recent developments in machine learning for energy systems reliability management. Proc. IEEE 2020, 108, 1656–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolnick, D.; Donti, P.L.; Kaack, L.H.; Kochanski, K.; Lacoste, A.; Sankaran, K.; Ross, A.S.; Milojevic-Dupont, N.; Jaques, N.; Waldman-Brown, A.; et al. Tackling climate change with machine learning. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2022, 55, 1–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat, F. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, B.C.; Tebaldi, C.; van Vuuren, D.P.; Eyring, V.; Friedlingstein, P.; Hurtt, G.; Knutti, R.; Kriegler, E.; Lamarque, J.-F.; Lowe, J.; et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model. Dev. 2016, 9, 3461–3482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebaldi, C.; Debeire, K.; Eyring, V.; Fischer, E.; Fyfe, J.; Friedlingstein, P.; Knutti, R.; Lowe, J.; O’Neill, B.; Sanderson, B.; et al. Climate model projections from the scenario model intercomparison project (ScenarioMIP) of CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2021, 12, 253–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghani, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; et al. An image is worth 16 × 16 words: Transformers for image recognition at scale. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.11929. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Chen, J.; Yu, R. ClimaX: A foundation model for weather and climate. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.10343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xue, P. Dual-transformer deep learning framework for seasonal forecasting of Great Lakes water levels. J. Geophys. Res. Mach. Learn. Comput. 2025, 2, e2024JH000519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zhu, L.; Ma, G.; Meadows, G.A.; Xue, P. Wave climate associated with changing water level and ice cover in Lake Michigan. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 746916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOAA. Available online: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/cdus/degree_days/ddayexp.shtml (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Fan, J.-L.; Hu, J.-W.; Zhang, X. Impacts of climate change on electricity demand in China: An empirical estimation based on panel data. Energy 2019, 170, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.J.; Liu, L.C.; Dong, Z.Y.; Wang, Z.; Yu, S.W.; Zhang, J.T. Response of China’s electricity consumption to climate change using monthly household data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 90272–90289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, A.; Meneu, V.; Valor, E. Temperature and seasonality influences on Spanish electricity load. Energy Econ. 2002, 24, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.P.; Xie, Z.; Li, X.; You, H.L.; Han, C. Relationship between electric demand and CDD and the forecast of daily peak electric load in Beijing. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 105, 55–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Shi, J.; Li, M.; Zhai, Z.; Zhang, R.; Wang, M. Variations of cooling and dehumidification degree days in major climate zones of China during the past 57 years. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, K.E. Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2001, 106, 7183–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auffhammer, M.; Baylis, P.; Hausman, C.H. Climate change is projected to have severe impacts on the frequency and intensity of peak electricity demand across the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1886–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Gao, J. Urbanization in China and the coordinated development model—The case of Chengdu. Soc. Sci. J. 2011, 48, 500–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Pizer, W.A.; Wu, L. Climate change and residential electricity consumption in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Reiner, D.M. Off seasons, holidays and extreme weather events: Using data-mining techniques on smart meter and energy consumption data from China. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 89, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornbush, M.; Golubchikov, O. Smart energy cities: The evolution of the city-energy-sustainability nexus. Environ. Dev. 2021, 39, 100626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budd, G.M. Wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT)—Its history and its limitations. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2008, 11, 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Napoli, C.; Pappenberger, F.; Cloke, H.L. Verification of heat stress thresholds for a health-based heat-wave definition. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2019, 58, 1177–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzan, J.R.; Huber, M. Moist heat stress on a hotter Earth. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2020, 48, 623–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhl, M.; Markolf, S. A review of emerging strategies for incorporating climate change considerations into infrastructure planning, design, and decision making. Sustain. Resilient Infrastruct. 2023, 8 (Suppl. 1), 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogiannidis, S.; Kalfas, D.; Papaevangelou, O.; Chatzitheodoridis, F.; Katsetsiadou, K.N.; Lekkas, E. 756 Integration of climate change strategies into policy and planning for regional development: A case study of Greece. Land 2024, 13, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billio, M.; Murgia, M.; Vismara, S. Sustainable and climate finance: An integrative framework from corporates to markets and society. Rev. Corp. Financ. 2024, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC); Territorial Development and Regional Economy Institute. Strategic Positioning and Planning Objectives of the Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration [EB/OL]; People’s Daily Online (Theory Edition); National Development and Reform Commission: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, W.Q.; Pickett, S.T.; Qian, Y. A scaling law for predicting urban tree canopy cooling efficiency. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2401210121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chengdu Municipal Institute of Planning and Design. Specialized Research Report of Chengdu Municipal Institute of Planning and Design; Chengdu Municipal Institute of Planning and Design: Chengdu, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).