Effect of Conventional Nitrogen Fertilization on Methane Uptake by and Emissions of Nitrous Oxide and Nitric Oxide from a Typical Cropland During a Maize Growing Season

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

2.2. Measurements of CH4, N2O and NO Fluxes

2.3. Auxiliary Measurements

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

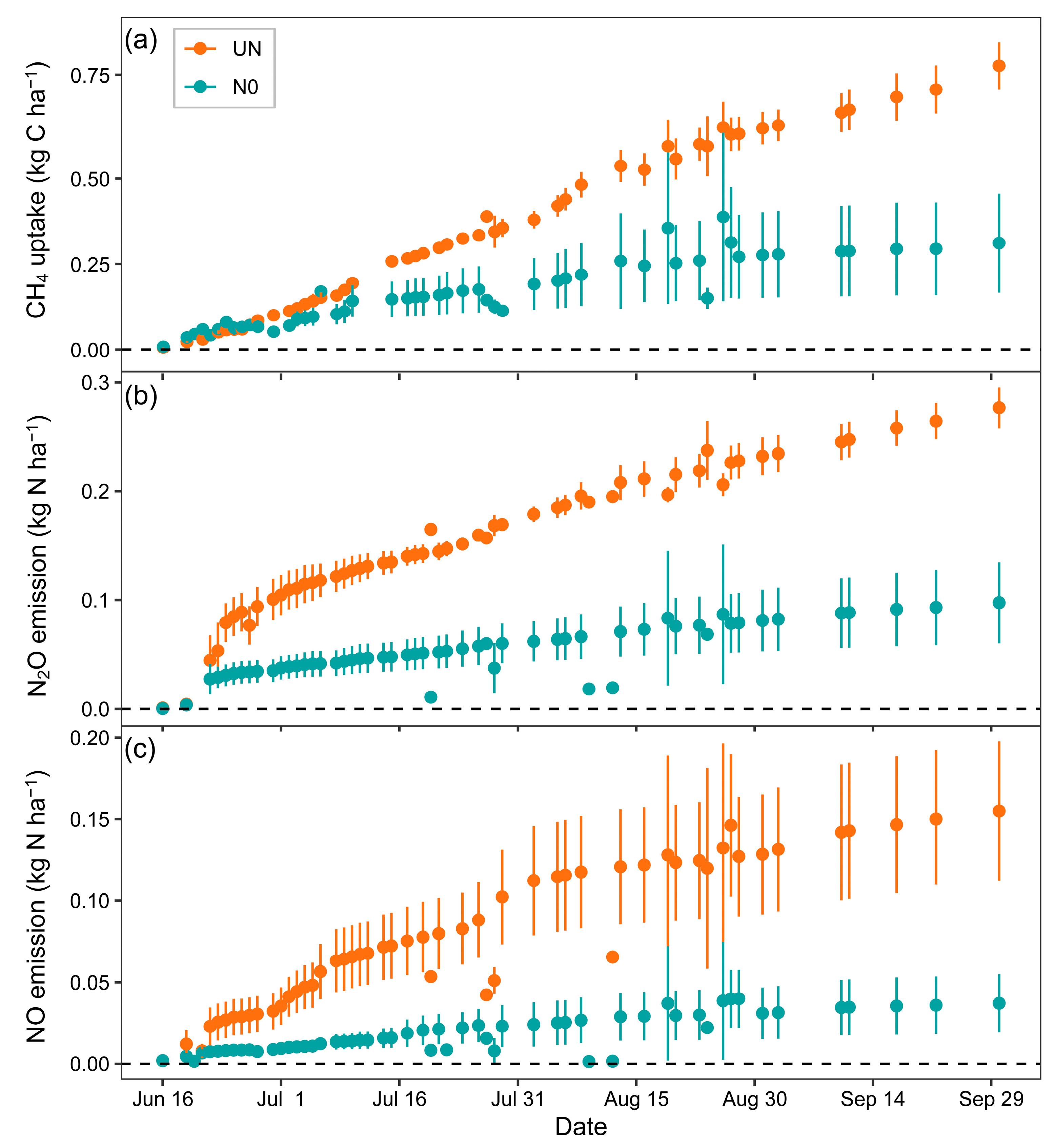

3.1. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilization on CH4, N2O and NO Fluxes and Their Integrated Global Warming Potential

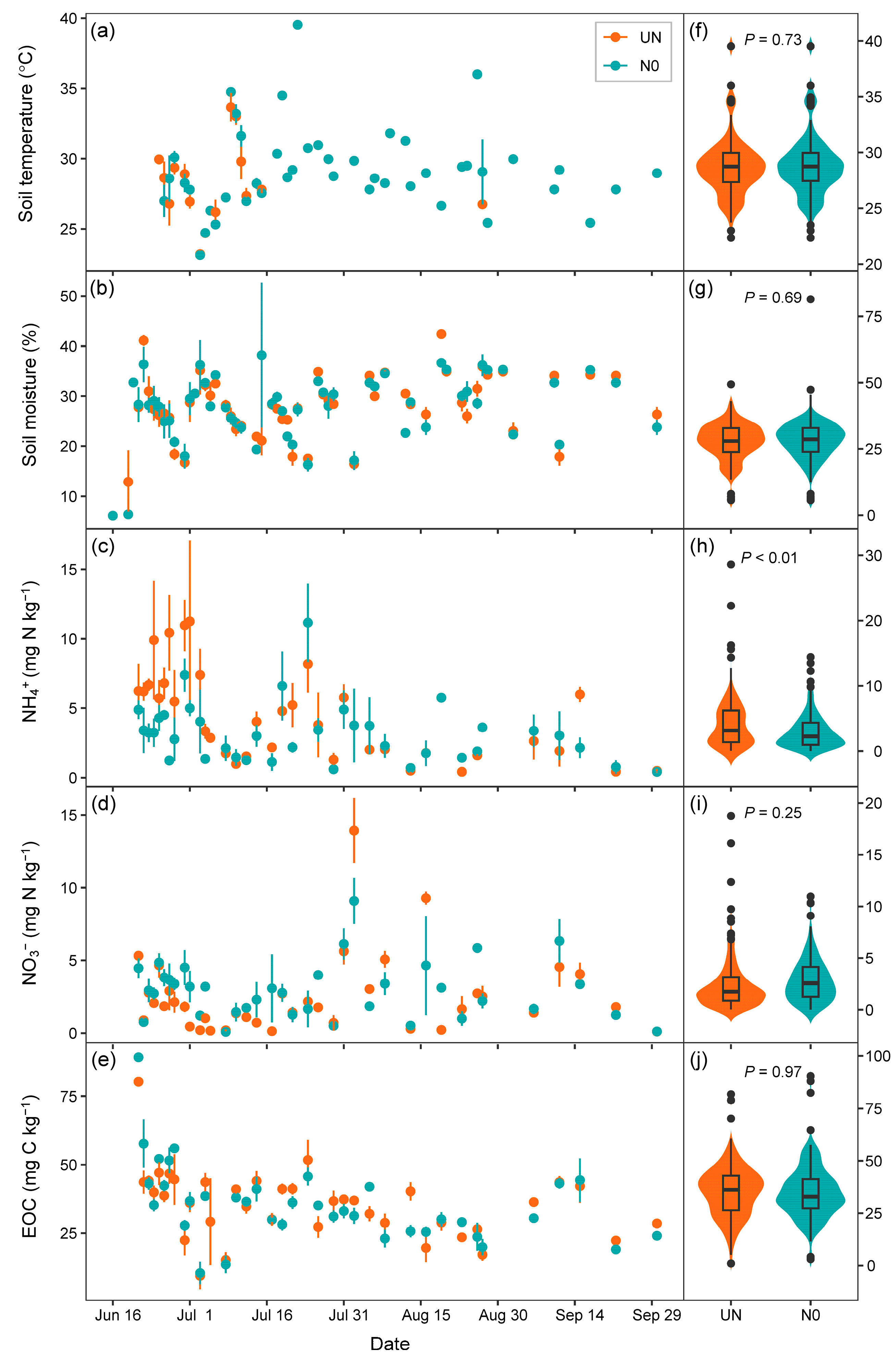

3.2. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilization on Soil Factors

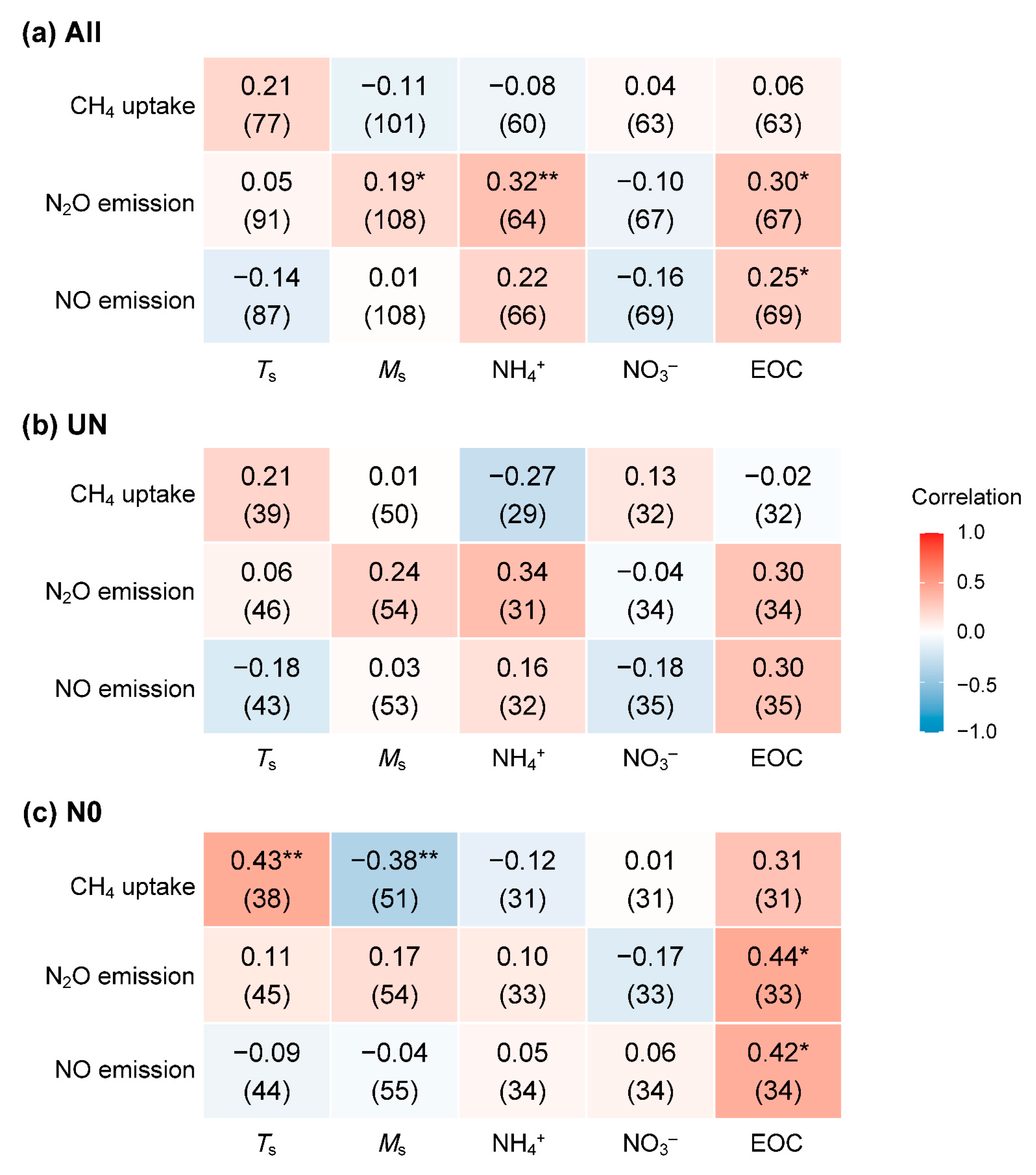

3.3. Effects of Nitrogen Fertilization on the Relationship Between Gas Fluxes and Soil Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanistic Shifts in Gas Fluxes Induced by Nitrogen Fertilization

4.2. Stability of Non-N Soil Factors and Their Implications

4.3. Optimizing Nitrogen Management: Mitigation Potential, Economic and Social Benefits

4.4. Limitations and Future Research Directions

- (i)

- Agro-ecosystem trade-offs: Future studies should employ multi-level nitrogen rate experiments coupled with concurrent yield monitoring to establish the relationship between nitrogen input, crop productivity, and greenhouse gas emissions, thereby enabling the identification of rates that minimize emission intensity.

- (ii)

- Long-term temporal analysis: Multi-year studies are essential to assess the permanence of the observed gas flux reductions under N0 and to evaluate potential long-term consequences for soil fertility, organic matter dynamics, and the resilience of the methane sink [96].

- (iii)

- Mechanistic microbial investigations: Integrating molecular techniques (e.g., qPCR, amplicon sequencing, metagenomics) is needed to characterize how nitrogen fertilization regimes shape the abundance, diversity, and functional gene expression of methanotrophic, nitrifying, and denitrifying microbial communities [12,100].

- (iv)

- Process-level tracing: Employing stable isotope techniques (e.g., 15N tracing) would allow for the precise quantification of the contributions of different pathways (e.g., nitrification, denitrification) to N2O and NO production, thereby moving beyond correlations to mechanistic understanding [63,101].

- (v)

- Evaluation of management strategies: Field trials should evaluate integrated management strategies—such as reduced nitrogen rates combined with enhanced-efficiency fertilizers (e.g., nitrification inhibitors, slow-release formulations), cover cropping, and precision split-application approaches—to identify the most effective methods for decoupling crop productivity from greenhouse gas emissions [92].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CH4 | Methane |

| N2O | Nitrous oxide |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| UN | Usual nitrogen application rate |

| N0 | Zero nitrogen application rate for the current year |

| NH4+ | Ammonium |

| NO3− | Nitrate |

| EOC | Extractable organic carbon |

References

- Mohanty, S.R. Synthesis Report on Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Agroecosystems: GHG Cycling, Microbial Processes, and Strategies for GHG Mitigation. In Greenhouse Gas Regulating Microorganisms in Soil Ecosystems: Perspectives for Climate Smart Agriculture; Mohanty, S.R., Kollah, B., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Stocker, T.F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.K.; Alexander, L.V.; Allen, S.K.; Bindoff, N.L.; Bréon, F.M.; Church, J.A.; Cubasch, U.; Emori, S. Technical summary. In Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Stocker, T.F., Qin, D., Plattner, G.K., Tignor, M., Allen, S.K., Boschung, J., Nauels, A., Xia, Y., Bex, V., Midgley, P.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 33–115. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S.; Havlík, P.; Stehfest, E.; van Meijl, H.; Witzke, P.; Pérez-Domínguez, I.; van Dijk, M.; Doelman, J.C.; Fellmann, T.; Koopman, J.F. Agricultural non-CO2 emission reduction potential in the context of the 1.5 C target. Nat. Clim. Change 2019, 9, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, A.; Movalia, S.; Pit, H.; Larsen, K. Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions: 1990–2020 and Preliminary 2021 Estimates; Rhodium Group: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Climate change and China’s agricultural sector: An overview of impacts, adaptation and mitigation. In Asia-Pacific Policy Program (APPP) Working Paper Series, No. 6; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, C.; Wironen, M.; Racette, K.; Wollenberg, E.K. Global Warming Potential (GWP): Understanding the implications for mitigating methane emissions in agriculture. In CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change; Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS): Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaisen, M.; Hillier, J.; Smith, P.; Nayak, D. Modelling CH4 emission from rice ecosystem: A comparison between existing empirical models. Front. Agron. 2023, 4, 1058649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Medhi, K.; Fagodiya, R.K.; Subrahmanyam, G.; Mondal, R.; Raja, P.; Malyan, S.K.; Gupta, D.K.; Gupta, C.K.; Pathak, H. Molecular and Ecological Perspectives of Nitrous Oxide Producing Microbial Communities in Agro-Ecosystems. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2020, 19, 717–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manco, A.; Giaccone, M.; Zenone, T.; Onofri, A.; Tei, F.; Farneselli, M.; Gabbrielli, M.; Allegrezza, M.; Perego, A.; Magliulo, V.; et al. An Overview of N2O Emissions from Cropping Systems and Current Strategies to Improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, M.I.; Osborne, B.A.; Wingler, A. Towards net zero emissions without compromising agricultural sustainability: What is achievable? Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2024, 128, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Walter, M.T.; Drinkwater, L.E. N2O emissions from grain cropping systems: A meta-analysis of the impacts of fertilizer-based and ecologically-based nutrient management strategies. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2017, 107, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodelier, P.L.E.; Laanbroek, H.J. Nitrogen as a regulatory factor of methane oxidation in soils and sediments. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2004, 47, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, E.L.; Helliker, B.R. Methane flux in non-wetland soils in response to nitrogen addition: A meta-analysis. Ecology 2010, 91, 3242–3251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wang, K.; Zheng, X. Responses of N2O and CH4 fluxes to fertilizer nitrogen addition rates in an irrigated wheat-maize cropping system in northern China. Biogeosciences 2012, 9, 839–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banger, K.; Tian, H.; Lu, C. Do nitrogen fertilizers stimulate or inhibit methane emissions from rice fields? Glob. Change Biol. 2012, 18, 3259–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-F.; Zhou, D.-N.; Kou, Z.-K.; Zhang, Z.-S.; Wang, J.-P.; Cai, M.-L.; Cao, C.-G. Effects of Tillage and Nitrogen Fertilizers on CH4 and CO2 Emissions and Soil Organic Carbon in Paddy Fields of Central China. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34642. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Gu, C.; Bai, Y. Effect of Fertilization on Methane and Nitrous Oxide Emissions and Global Warming Potential on Agricultural Land in China: A Meta-Analysis. Agriculture 2024, 14, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhuo, X.; Qiu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Gu, J.; Wang, W.; et al. Reducing methane emission by promoting its oxidation in rhizosphere through nitrogen-induced root growth in paddy fields. Plant Soil 2022, 474, 541–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.R.; Bodelier, P.L.E.; Floris, V.; Conrad, R. Differential Effects of Nitrogenous Fertilizers on Methane-Consuming Microbes in Rice Field and Forest Soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Delaune, R.D.; Lindau, C.W.; Patrick, W.H. Methane production from anaerobic soil amended with rice straw and nitrogen fertilizers. Fert. Res. 1992, 33, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Su, R.; Yang, G.; Li, X.; Kang, J.; Shi, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wang, N.; et al. Association between CH4 uptake and N2O emission in grassland depends on nitrogen inputs. J. Plant Ecol. 2024, 17, rtae078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Liu, X.; Wang, T.; Li, N.; Bing, H. Stimulated or Inhibited Response of Methane Flux to Nitrogen Addition Depends on Nitrogen Levels. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2021, 126, e2021JG006600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, B.; Zheng, X.; Zhou, Z.; Gu, J.; Zhu, B.; Chen, X.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, C.; et al. Effects of nitrogen fertilizer on CH4 emission from rice fields: Multi-site field observations. Plant Soil 2010, 326, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, E.L.; Vann, D.R.; Helliker, B.R. Methane flux response to nitrogen amendment in an upland pine forest soil and riparian zone. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2012, 117, G03011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ge, J.; Feng, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Xiao, X.; Zhang, Z. The Synergism between Methanogens and Methanotrophs and the Nature of their Contributions to the Seasonal Variation of Methane Fluxes in a Wetland: The Case of Dajiuhu Subalpine Peatland. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 39, 1375–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Wehmeyer, H.; Heffner, T.; Aeppli, M.; Gu, W.; Kim, P.J.; Horn, M.A.; Ho, A. Resilience of aerobic methanotrophs in soils; spotlight on the methane sink under agriculture. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2024, 100, fiae008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahal, N.K.; Osterholz, W.R.; Miguez, F.E.; Poffenbarger, H.J.; Sawyer, J.E.; Olk, D.C.; Archontoulis, S.V.; Castellano, M.J. Nitrogen Fertilizer Suppresses Mineralization of Soil Organic Matter in Maize Agroecosystems. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2019, 7, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klüber, H.D.; Conrad, R. Effects of nitrate, nitrite, NO and N2O on methanogenesis and other redox processes in anoxic rice field soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 1998, 25, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosier, A.R.; Halvorson, A.D.; Reule, C.A.; Liu, X.J. Net Global Warming Potential and Greenhouse Gas Intensity in Irrigated Cropping Systems in Northeastern Colorado. J. Environ. Qual. 2006, 35, 1584–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, M.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W. Reducing CH4 and CO2 emissions from waterlogged paddy soil with biochar. J. Soils Sediments 2011, 11, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, R.; Xu, W.; Zhao, M.; Sun, W. Grazing offsets the stimulating effects of nitrogen addition on soil CH4 emissions in a meadow steppe in Northeast China. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, Z.; Pan, Z.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zheng, X. Nonlinear response of soil nitric oxide emissions to fertilizer nitrogen across croplands. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.D.; Lewis, K.L.; DeLaune, P.B.; Hux, B.A.; Boutton, T.W.; Gentry, T.J. Nitrogen fertilizer driven nitrous and nitric oxide production is decoupled from microbial genetic potential in low carbon, semi-arid soil. Front. Soil Sci. 2023, 2, 1050779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breitenbeck, G.A.; Blackmer, A.M.; Bremner, J.M. Effects of different nitrogen fertilizers on emission of nitrous oxide from soil. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1980, 7, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherbak, I.; Millar, N.; Robertson, G.P. Global metaanalysis of the nonlinear response of soil nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions to fertilizer nitrogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 9199–9204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stępniewski, W.; Sobczuk, H.; Widomski, M. Diffusion in Soils. In Encyclopedia of Agrophysics; Gliński, J., Horabik, J., Lipiec, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 214–220. [Google Scholar]

- Dowdeswell-Downey, E.; Grabowski, R.C.; Rickson, R.J. Do temperature and moisture conditions impact soil microbiology and aggregate stability? J. Soils Sediments 2023, 23, 3706–3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, E.J.; Baggs, E.M. Contributions of nitrification and denitrification to N2O emissions from soils at different water-filled pore space. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2005, 41, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morier, I.; Guenat, C.; Siegwolf, R.; Védy, J.C.; Schleppi, P. Dynamics of Atmospheric Nitrogen Deposition in a Temperate Calcareous Forest Soil. J. Environ. Qual. 2008, 37, 2012–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwunife, K.C.; Madramootoo, C.A.; Abbasi, N.A. Assessing the impacts of tillage, cover crops, nitrification, and urease inhibitors on nitrous oxide emissions over winter and early spring. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2022, 58, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastal, F.; Lemaire, G. N uptake and distribution in crops: An agronomical and ecophysiological perspective. J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 789–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siatwiinda, S.M.; Ros, G.H.; Yerokun, O.A.; de Vries, W. Options to reduce ranges in critical soil nutrient levels used in fertilizer recommendations by accounting for site conditions and methodology: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 44, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. China Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N.; Brauman, K.A.; Cassidy, E.S.; Gerber, J.S.; Johnston, M.; Mueller, N.D.; O’Connell, C.; Ray, D.K.; West, P.C.; et al. Solutions for a cultivated planet. Nature 2011, 478, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, S.; Hu, C. Review on greenhouse gas emission and reduction in wheat-maize double cropping system in the North China Plain. Chin. J. Eco Agric. 2018, 26, 167–174. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E.; Yu, Q.; Wu, D.; Xia, J. Climate, agricultural production and hydrological balance in the North China Plain. Int. J. Climatol. 2008, 28, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.T.; Xing, G.X.; Chen, X.P.; Zhang, S.L.; Zhang, L.J.; Liu, X.J.; Cui, Z.L.; Yin, B.; Christie, P.; Zhu, Z.L.; et al. Reducing environmental risk by improving N management in intensive Chinese agricultural systems. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 3041–3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, J.; Ahmad, S.; Malik, M. Nitrogenous fertilizers: Impact on environment sustainability, mitigation strategies, and challenges. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 11649–11672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, W.; Tang, A.; Shen, J.; Cui, Z.; Vitousek, P.; Erisman, J.W.; Goulding, K.; Christie, P.; et al. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature 2013, 494, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Xu, W.; Pan, Y.; Duan, L. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition to China: A model analysis on nitrogen budget and critical load exceedance. Atmos. Environ. 2017, 153, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Zheng, X.; Xie, B.; Liu, C.; Mei, B.; Dong, H.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Zhu, J. Comparison of manual and automated chambers for field measurements of N2O, CH4, CO2 fluxes from cultivated land. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 1888–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yao, Z.; Wang, K.; Zheng, X.; Ma, L.; Wang, R.; Liu, C.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, B.; Tang, X.; et al. Annual N2O emissions from conventionally grazed typical alpine grass meadows in the eastern Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Mei, B.; Wang, Y.; Xie, B.; Wang, Y.; Dong, H.; Xu, H.; Chen, G.; Cai, Z.; Yue, J.; et al. Quantification of N2O fluxes from soil–plant systems may be biased by the applied gas chromatograph methodology. Plant Soil 2008, 311, 211–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ling, H. A new carrier gas type for accurate measurement of N2O by GC-ECD. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2010, 27, 1322–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Ma, L.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Wang, K.; Zhu, B.; Wang, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; et al. Characteristics of annual greenhouse gas flux and NO release from alpine meadow and forest on the eastern Tibetan Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2019, 272–273, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, B.; Zheng, X.; Xie, B.; Dong, H.; Yao, Z.; Liu, C.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, R.; Deng, J.; Zhu, J. Characteristics of multiple-year nitrous oxide emissions from conventional vegetable fields in southeastern China. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2011, 116, D12113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Wei, Y.; Liu, C.; Zheng, X.; Xie, B. Organically fertilized tea plantation stimulates N2O emissions and lowers NO fluxes in subtropical China. Biogeosciences 2015, 12, 5915–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zheng, X.; Pihlatie, M.; Vesala, T.; Liu, C.; Haapanala, S.; Mammarella, I.; Rannik, Ü.; Liu, H. Comparison between static chamber and tunable diode laser-based eddy covariance techniques for measuring nitrous oxide fluxes from a cotton field. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 171–172, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, B.; Zheng, X.; Xie, B.; Dong, H.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, R.; Deng, J.; Cui, F.; Tong, H.; Zhu, J. Nitric oxide emissions from conventional vegetable fields in southeastern China. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 2762–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wang, R. Protocols for Chamber-Based Manual Measurement of CH4 and N2O Fluxes from Terrestrial Ecosystems; Meteorology Press: Beijing, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Luo, Y.; Quan, Q.; Ma, F.; Tian, D.; Chen, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, L.; Meng, C.; Niu, S. Effects of warming and clipping on CH4 and N2O fluxes in an alpine meadow. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 297, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, E.A. Fluxes of Nitrous Oxide and Nitric Oxide from Terrestrial Ecosystems. In Microbial Production and Consumption of Greenhouse Gases: Methane, Nitrogen Oxides, and Halomethanes; Rogers, J.E., Whitman, W.B., Eds.; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1991; pp. 219–235. [Google Scholar]

- Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Baggs, E.M.; Dannenmann, M.; Kiese, R.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: How well do we understand the processes and their controls? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2013, 368, 20130122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.; Taylor, J.A. On the Temperature Dependence of Soil Respiration. Funct. Ecol. 1994, 8, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, A.; Kerckhof, F.M.; Luke, C.; Reim, A.; Krause, S.; Boon, N.; Bodelier, P.L.E. Conceptualizing functional traits and ecological characteristics of methane-oxidizing bacteria as life strategies. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2013, 5, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, P.J.; Boyer, J.S. Transpiration and the Water Balance. In Water Relations of Plants and Soils; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 131–158. [Google Scholar]

- Good, S.P.; Noone, D.; Bowen, G. Hydrologic Connectivity Constrains Partitioning of Global Terrestrial Water Fluxes. Science 2015, 349, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, B.C. Soil structure and greenhouse gas emissions: A synthesis of 20 years of experimentation. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2013, 64, 357–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunfield, P.F.; Conrad, R. Starvation alters the apparent half-saturation constant for methane in the type II methanotroph Methylocystis strain LR1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 4136–4138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firestone, M.; Davidson, E. Microbiological Basis of NO and N2O Production and Consumption in Soil. In Exchange of Trace Gases between Terrestrial Ecosystems and the Atmosphere; Andreae, M.O., Schimel, D.S., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 1989; pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Burger, M.; Doane, T.A.; Horwath, W.R. Ammonia oxidation pathways and nitrifier denitrification are significant sources of N2O and NO under low oxygen availability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 6328–6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senbayram, M.; Chen, R.; Budai, A.; Bakken, L.; Dittert, K. N2O emission and the N2O/(N2O+N2) product ratio of denitrification as controlled by available carbon substrates and nitrate concentrations. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2012, 147, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, N.E.; Sutka, R.; Ostrom, P.H.; Grandy, A.S.; Huizinga, K.M.; Gandhi, H.; von Fischer, J.C.; Robertson, G.P. Isotopologue data reveal bacterial denitrification as the primary source of N2O during a high flux event following cultivation of a native temperate grassland. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Mørkved, P.T.; Frostegård, Å.; Bakken, L.R. Denitrification gene pools, transcription and kinetics of NO, N2O and N2 production as affected by soil pH. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 72, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundy, M.E.; Pittelkow, C.M.; Linquist, B.A.; Liang, X.; van Groenigen, K.J.; Lee, J.; Six, J.; Venterea, R.T.; van Kessel, C. Nitrogen fertilization reduces yield declines following no-till adoption. Field Crops Res. 2015, 183, 204–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Balser, T.C. Microbial production of recalcitrant organic matter in global soils: Implications for productivity and climate policy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venterea, R.T.; Groffman, P.M.; Verchot, L.V.; Magill, A.H.; Aber, J.D. Gross nitrogen process rates in temperate forest soils exhibiting symptoms of nitrogen saturation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 196, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, S.D.; Martiny, J.B.H. Resistance, resilience, and redundancy in microbial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 11512–11519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, C.; Bender, S.F.; Widmer, F.; van der Heijden, M.G.A. Soil biodiversity and soil community composition determine ecosystem multifunctionality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5266–5270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedin, D.A.; Tilman, D. Influence of Nitrogen Loading and Species Composition on the Carbon Balance of Grasslands. Science 1996, 274, 1720–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornwell, W.K.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Amatangelo, K.; Dorrepaal, E.; Eviner, V.T.; Godoy, O.; Hobbie, S.E.; Hoorens, B.; Kurokawa, H.; Pérez-Harguindeguy, N.; et al. Plant species traits are the predominant control on litter decomposition rates within biomes worldwide. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.A.; Mulvaney, R.L.; Ellsworth, T.R.; Boast, C.W. The Myth of Nitrogen Fertilization for Soil Carbon Sequestration. J. Environ. Qual. 2007, 36, 1821–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBauer, D.S.; Treseder, K.K. Nitrogen limitation of net primary productivity in terrestrial ecosystems is globally distributed. Ecology 2008, 89, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilman, D.; Balzer, C.; Hill, J.; Befort, B.L. Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 20260–20264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Ma, L.; Ma, W.; Wu, Z.; Cui, Z.; Hou, Y.; Zhang, F. What has caused the use of fertilizers to skyrocket in China? Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2018, 110, 241–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Davidson, E.A.; Mauzerall, D.L.; Searchinger, T.D.; Dumas, P.; Shen, Y. Managing nitrogen for sustainable development. Nature 2015, 528, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, T.E.; Yue, S.; Schulz, R.; He, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, F.; Müller, T. Yield and N use efficiency of a maize–wheat cropping system as affected by different fertilizer management strategies in a farmer’s field of the North China Plain. Field Crops Res. 2015, 174, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant Acidification in Major Chinese Croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, D.S.; Davidson, E.A.; Smith, K.A.; Smith, P.; Melillo, J.M.; Dentener, F.; Crutzen, P.J. Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wen, X. Integrated N management improves nitrogen use efficiency and economics in a winter wheat–summer maize multiple-cropping system. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2019, 115, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, C.; Ma, W.; Huang, C.; Zhang, W.; Mi, G.; Miao, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Pursuing sustainable productivity with millions of smallholder farmers. Nature 2018, 555, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cui, Z.; Fan, M.; Vitousek, P.; Zhao, M.; Ma, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Yan, X.; Yang, J.; et al. Producing more grain with lower environmental costs. Nature 2014, 514, 486–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.P.; Cui, Z.L.; Vitousek, P.M.; Cassman, K.G.; Matson, P.A.; Bai, J.S.; Meng, Q.F.; Hou, P.; Yue, S.C.; Römheld, V.; et al. Integrated soil–crop system management for food security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6399–6404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, T.; Lateef, S.; Noor, M.A. Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in Agroecosystems: An Overview. In Carbon and Nitrogen Cycling in Soil; Datta, R., Meena, R.S., Pathan, S.I., Ceccherini, M.T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, A.E.; Poulton, P.R. The importance of long-term experiments in agriculture: Their management to ensure continued crop production and soil fertility; the Rothamsted experience. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2018, 69, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimel, J.; Schaeffer, S.M. Microbial control over carbon cycling in soil. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazaries, L.; Murrell, J.C.; Millard, P.; Baggs, L.; Singh, B.K. Methane, microbes and models: Fundamental understanding of the soil methane cycle for future predictions. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 15, 2395–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggs, E.M. Soil microbial sources of nitrous oxide: Recent advances in knowledge, emerging challenges and future direction. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 321–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. The soil microbiome-from metagenomics to metaphenomics. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 43, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baggs, E.M. A review of stable isotope techniques for N2O source partitioning in soils: Recent progress, remaining challenges and future considerations. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 22, 1664–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gas | Treatment 1 | N 2 | Mean | Min | Max | Effect 3 | p 4 | Cum 5 | Cumulative CO2-eq 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg C or N m−2 h −1 | % | kg C or N ha−1 | kg CO2-eq ha−1 | ||||||

| CH4 | UN | 50 | 33.62 | 0.39 | 92.51 | 154 | <0.001 | 0.82 ± 0.07 | −2.25 ± 0.19 |

| N0 | 51 | 13.25 | 1.72 | 46.56 | 0.30 ± 0.14 | −0.82 ± 0.38 | |||

| N2O | UN | 56 | 12.07 | 1.71 | 81.90 | 190 | <0.001 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 74.20 ± 5.30 |

| N0 | 56 | 4.16 | 0.80 | 49.84 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 26.50 ± 10.60 | |||

| NO | UN | 54 | 6.62 | 1.14 | 34.69 | 301 | <0.001 | 0.15 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.04 |

| N0 | 57 | 1.65 | 0.15 | 9.81 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | |||

| Total Gaseous N Loss (N2O + NO) | UN | 0.43 ± 0.04 | |||||||

| N0 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | ||||||||

| Net Total CO2-eq (CH4 + N2O + NO) | UN | 72.10 ± 5.32 | |||||||

| N0 | 25.72 ± 10.61 | ||||||||

| Total CO2-eq Mitigation 7 | N0 vs. UN | 46.38 ± 11.89 | |||||||

| Gas | Treatment 1 | n | Mean | Min | Max | Effect (%) 2 | p 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil temperature (°C) | UN | 46 | 29.09 | 23.20 | 39.53 | −0.31 | 0.73 |

| N0 | 45 | 29.18 | 23.15 | 39.53 | |||

| Soil moisture (%) | UN | 55 | 27.72 | 6.15 | 42.40 | −0.11 | 0.69 |

| N0 | 56 | 27.75 | 6.15 | 38.20 | |||

| NH4+ (mg N kg−1) | UN | 35 | 4.36 | 0.42 | 11.25 | 37.11 | <0.01 |

| N0 | 37 | 3.18 | 0.42 | 11.15 | |||

| NO3− | UN | 38 | 2.49 | 0.11 | 13.94 | −14.73 | 0.25 |

| (mg N kg−1) | N0 | 37 | 2.92 | 0.09 | 9.09 | ||

| EOC | UN | 38 | 35.59 | 9.44 | 80.31 | −0.25 | 0.97 |

| (mg C kg−1) | N0 | 37 | 35.68 | 10.44 | 89.19 |

| No. 1 | Equations 2 | Q10 3 | N 4 | R2 4 | p 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | |||||

| (1) | = | 1.80 | 49 | 0.07 | <0.1 |

| (2) | = | 1.25 | 53 | 0.15 | <0.05 |

| (3) | = | 1.79 | 53 | 0.27 | <0.01 |

| (4) | = | 1.36 | 53 | 0.20 | <0.01 |

| UN | |||||

| (5) | = | 1.06 | 24 | 0.18 | <0.01 |

| (6) | = | 1.08 | 26 | 0.17 | <0.01 |

| (7) | = 1. | 0.88 | 26 | 0.26 | <0.01 |

| (8) | = | 1.46 | 26 | 0.29 | <0.01 |

| (9) | = | 1.08 | 26 | 0.20 | <0.01 |

| N0 | |||||

| (10) | = 0.87 | 2.44 | 38 | 0.20 | <0.01 |

| (11) | = –0.57+ 29.33 | 50 | 0.14 | <0.05 | |

| (12) | = (0.89–0.001] | 2.44 | 38 | 0.20 | <0.01 |

| (13) | = | 7.54 | 25 | 0.43 | <0.001 |

| (14) | = 1.11 | 0.74 | 27 | 0.30 | <0.01 |

| (15) | = | 0.89 | 27 | 0.36 | <0.001 |

| (16) | = 0.015 | 1.68 | 27 | 0.17 | <0.01 |

| (17) | = | 2.36 | 27 | 0.20 | <0.01 |

| (18) | = | 1.27 | 27 | 0.36 | <0.001 |

| (19) | = 0.044 + 0.016 + | 27 | 0.19 | <0.01 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tian, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Han, S.; Yao, Z.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; et al. Effect of Conventional Nitrogen Fertilization on Methane Uptake by and Emissions of Nitrous Oxide and Nitric Oxide from a Typical Cropland During a Maize Growing Season. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121354

Tian Z, Li Y, Wang K, Wang R, Zhang Y, Sun Y, Han S, Yao Z, Liu C, Li J, et al. Effect of Conventional Nitrogen Fertilization on Methane Uptake by and Emissions of Nitrous Oxide and Nitric Oxide from a Typical Cropland During a Maize Growing Season. Atmosphere. 2025; 16(12):1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121354

Chicago/Turabian StyleTian, Zhenyong, Yimeng Li, Kai Wang, Rui Wang, Yuting Zhang, Yi Sun, Shenghui Han, Zhisheng Yao, Chunyan Liu, Jing Li, and et al. 2025. "Effect of Conventional Nitrogen Fertilization on Methane Uptake by and Emissions of Nitrous Oxide and Nitric Oxide from a Typical Cropland During a Maize Growing Season" Atmosphere 16, no. 12: 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121354

APA StyleTian, Z., Li, Y., Wang, K., Wang, R., Zhang, Y., Sun, Y., Han, S., Yao, Z., Liu, C., Li, J., Li, S., Chen, X., Li, Y., & Zheng, X. (2025). Effect of Conventional Nitrogen Fertilization on Methane Uptake by and Emissions of Nitrous Oxide and Nitric Oxide from a Typical Cropland During a Maize Growing Season. Atmosphere, 16(12), 1354. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos16121354