Abstract

Due to its sensitivity to topographic and land use land cover features, air temperature (maximum, minimum, and mean—Tx, Tn, and Tmean) is extremely variable in space and time. The sparse and unevenly distributed meteorological stations observed across remote regions cannot monitor such variability. Freely available, gridded temperature datasets (T-datasets) are positioned as an opportunity to overcome this issue. Still, their coarse spatial resolution (i.e., ≥5 km) does not allow for the observation of air temperature variations on a fine spatial scale. In this context, a set of variables that have a close relationship with daily air temperature (MODIS maximum, minimum, and mean Land Surface Temperature—LSTx, LSTn, and LSTmean; MODIS NDVI; SRTM topographic features—elevation, slope, and aspect) are integrated in three regression machine-learning models (Random Forest—RF, eXtreme Gradient Boosting—XGB, Multiple Linear Regression—MLR) to propose a T-dataset estimates (Tx, Tn, and Tmean) spatial resolution downscaling framework. The approach consists of two main steps: firstly, the machine-learning models are trained at the native 5 km spatial resolution of the studied T-dataset (i.e., CHIRTS); secondly, the application of the trained machine-learning models at a 1 km spatial resolution to downscale CHIRTS from 5 km to 1 km. The results show that the method not only improves the spatial resolution of the CHIRTS dataset, but also its accuracy, with higher improvements for Tn than for Tx and Tmean. Among the considered models, RF performs the best, with an R2, RMSE, and MAE improvement of 2.6% (0%), 47.1% (6.1%), and 55.3% (7%) for Tn (Tx). These results will support air temperature monitoring and related extreme events such as heat and cold waves, which are of prime importance in the actual climate change context.

1. Introduction

The ongoing temperature increase threatens ecosystem and human well-being sustainability as the adaptation time requirement does not fit with the global warming velocity. This time lag between air temperature change and adaptation is even more worrying because global warming not only comes with gradual temperature changes, but also with an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme temperature events such as heat and cold waves (HWs and CWs, respectively) [1,2]. These events give a temporal overview (i.e., a few days) of what could be the norm in the coming years and raise (i) public health concerns as they increase mortality and morbidity related to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases [3,4,5,6] and (ii) food security concerns as they reduce cereals and no-cereal yields [7,8] and increase cattle mortality [9]. These concerns are catalyzed by additional negative effects, such as the decrease in water resources availability and green energy production, which may worsen public health and food security concerns [10].

Although the findings of the above-mentioned studies are unequivocal, they are based upon air temperature records from meteorological stations, whose distribution and density are generally too low to accurately monitor air temperature dynamics in space and time. Actually, as point measurements, meteorological air temperature records are only representative of the vicinity area of the considered stations. To overcome this issue, air temperature estimates are interpolated to provide a synopsis overview of the air temperature pattern. However, interpolations are subject to uncertainties as the morphological features affecting air temperature in between the stations are not (or poorly) considered in the interpolation process. To overcome this issue, some authors take advantage of spatially continuous estimations of gridded air temperature datasets (T-datasets) to report on air temperature trends across remote regions with a sparse and unevenly distributed meteorological station network. In this context, CHIRTS and ERA5 T-datasets have been used to study (i) HWs in Kenya [11], Tanzania [12], Nigeria [13], Africa [14], and Chile [15], and (ii) air temperature trends in Bolivia [16] and Turkey [17].

However, T-datasets estimates are derived from indirect satellite and/or reanalysis datasets subject to space and time uncertainties affecting trends and/or extreme events analysis consistency [16]. Therefore, prior to their use, a T-dataset reliability assessment is required to weight any air temperature interpretation that could be drawn from such datasets. T-dataset reliability assessment consists of comparing their estimates with those registered by meteorological stations [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. According to these studies, T-dataset reliability drastically changes in space and time. For example, across India, MERRA2 accuracy presents a variation of more than 30% depending on the considered season or region [19]. A similar observation was observed across Bolivia for ERA5, MERRA2, CHIRTS, CPC, WFDEI, and PGF T-datasets [16], and for ERA5 across the Antarctic [20,21]. According to these studies, part of the uncertainty is due to their coarse spatial resolution, which cannot capture the local air temperature observed at the meteorological station level.

In this context, efforts have been made to increase the spatial resolution of T-datasets in order to reduce their space and time uncertainties [25,26]. The method consists of using the relationship between (i) the observed air temperature estimates (i.e., meteorological station) and (ii) the T-dataset estimates. In this process, additional features controlling temperature variation in space and time (i.e., topography, Land Surface Temperature—LST, NDVI, and wind) are considered to adjust the relationship in space and time. Topographic features gathered relevant information such as elevation lapse rate and insolation exposure related to slope and/or aspect features that control air temperature variability in space and time [27]. Similarly, the NDVI gathered relevant information on green space area distribution, which reduces air temperature due to its limited heat storage capacity and evaporation process that humidifies the atmosphere [28]. Finally, a strong relationship between Land Surface Temperature (LST) and air temperature was previously reported in different studies [29,30,31,32,33,34,35].

As machine-learning models have proven capability of capturing nonlinear relationships relevant to air temperature estimation [34], these models are generally used for T-datasets spatial downscaling [25,26,30,34,36]. The models are first calibrated at the original coarse spatial resolution of the T-dataset and then applied at a higher spatial resolution to spatially downscale the T-dataset estimates. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of such an approach in different contexts. In Morocco, Sebbar et al. [36] evaluated three models (eXtreme Gradient Boosting—XGB, Support Vector Regression—SVR, and Multiple Linear Regression—MLR) to downscale ERA5 hourly air temperature estimates. The results show that XGB provided the most accurate estimates, with an R2 and RMSE of 0.97 and 1.61 °C. In the Eastern Mediterranean region, Blizer et al. [25] compared XGB and Deep Neural Network (DNN) models to downscale ERA5 daily mean air temperature (Tmean) estimates. The results show that the DNN model provided the most reliable results, with R2 and RMSE of 0.97 and 0.98 °C, respectively. In Mongolia, Otgonbayar et al. [34] compared Random Forest (RF) and Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) models to estimate monthly Tmean from the MODIS LST product (MOD11A2). The results show that the RF model provided the most accurate estimates, obtaining R2 and RMSE values of 0.88 and 1.4 °C, respectively. Finally, in China, Wang et al. [30] compared five machine-learning models (RF, Decision Trees—DT, Feedforward Neural Network—FNN, Generalized Linear Model—GLM, and Support Vector Machine—SVM), identifying MODIS LST products (MOD11A1 and MYD11A1) among the most relevant variables for generating daily and instantaneous T-datasets. The results show that, for daily Tmean estimates, RF was the most suitable, with R2 and RMSE values of 0.99 and 1.29 °C, respectively. Overall, these studies show that the models’ performance was highly variable due to their sensitivity to (i) input variables (predictors), geographic and topographic characteristics, and (ii) considered temporal scale [25,30,34]. This observation is consistent with the No Free Lunch (NFL) theorem by Wolpert and MacReady [37], which states that no algorithm is universally superior for all optimization and supervised learning problems.

To date, T-datasets downscaling studies are limited to Tmean estimates [25,26,38]. However, in the current context of climate change with an increase in the frequency and intensity of both HWs and CWs, accurate estimates of maximum and minimum temperature (Tx and Tn, respectively) are required to improve HWs and CWs monitoring to support sustainable adaptation. In this context, this study proposes a machine-learning modeling approach to downscale CHIRTS T-dataset Tmean, Tx, and Tn estimates at the 1 km spatial resolution. CHIRTS is considered, as it has not yet been considered in such an approach, despite its overall higher reliability [16].

As the downscaling procedure is sensitive to the considered models [25,36,38], different models are considered (i.e., Random Forest—RF, eXtreme Gradient Boosting—XGB, Multi-LinearRegression—MLR) to highlight the best option. Finally, Madagascar is considered as the study area because of its high sensitivity to air temperature changes [39], which threatens national food and sanitary security [40].

2. Materials

2.1. Study Area

Madagascar, covering an area of 587,041 km2, ranks among the largest islands globally. Situated in the Indian Ocean, the island exhibits significant topographic variation (Figure 1f). These geographical features contribute to marked climatic heterogeneity across the island. Bioclimatic classification identifies four distinct regions—humid, semi-humid, dry, and semi-arid [41]—and a pronounced seasonal pattern, with a wet season spanning November to April and a dry season from May to October.

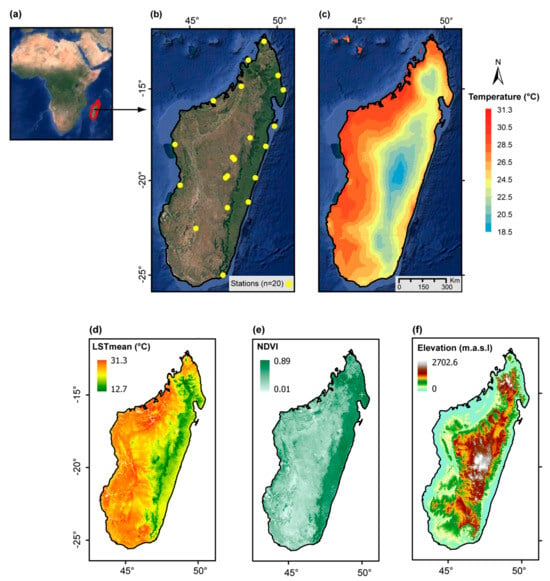

Figure 1.

Location of Madagascar (a) and the meteorological stations considered (n = 20) (b), along with the annual daily average of CHIRTS Tmean (c), MODIS LSTmean and NDVI (d,e), and SRTM elevation (f).

The nation faces some of the highest poverty levels worldwide [42] and, as a developing country, struggles with limited institutional capacity to sustain meteorological monitoring infrastructure. Consequently, the density of meteorological stations remains low (Figure 1b), and new hydro-climatic monitoring initiatives are being maintained by humanitarian organizations and academics (e.g., [43,44]). The sparse station network poses a significant challenge, as Madagascar’s complex topography and diverse climate result in substantial spatial air temperature variability. T-datasets fill the data gap, but spatial resolution is a major issue due to the high spatial variability of air temperature. Madagascar is therefore an ideal case study that combines technical and societal concerns that motivate improvements in T-datasets spatial resolution.

2.2. Meteorological Stations

Daily maximum and minimum two-meter air temperature estimates (Tx and Tn) for 2015 and 2016 were obtained from 20 meteorological stations managed by Madagascar’s General Directorate of Meteorology (DGM) and the International Center for Agricultural Research for Development (CIRAD) (Figure 1b). Mean air temperature (Tmean) was computed from observed Tx and Tn values (Equation (1)).

2.3. CHIRTS

The Climate Hazards Center InfraRed Temperature with Station daily (CHIRTS-daily; [24]), hereinafter referred to as CHIRTS, is a dataset developed by the Climate Hazards Center (CHC) at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The CHIRTS air temperature estimates at 2 m above the ground (Tx and Tn) are derived from remotely sensed infrared land surface emission temperatures, a global network of approximately 15,000 in situ stations, and temperature fields from ERA5 [45]. The dataset has been validated on a quasi-global scale, ranging from 60° S to 70° N, and has a spatial resolution of 0.05° × 0.05 (approximately 5 km × 5 km) [24]. At a more local scale, CHIRTS has been shown to provide the most reliable air temperature estimates (Tn, Tx, and Tmean) in Bolivia [16]. In this study, CHIRTS Tx and Tn for the 2015–2016 period were considered and used to calculate CHIRTS Tmean (Equation (1)).

2.4. MODIS Land Surface Temperature

MODIS LST products (MOD11A1 and MYD11A1 from the TERRA and AQUA satellites, respectively) provide daily LST estimates at both day and nighttime. However, the applications of these data face serious challenges [46] because of missing values caused by cloud cover exceeding 55% on average [47,48]. To overcome this limitation, we used the MODIS-like LST product generated from the MODIS LST estimates (MOD11A1 and MYD11A1) using a gap-filling method for cloudy periods and regions to obtain continuous LST observations in space and time [49]. The MODIS-like product provides daily LST estimates at both day and nighttime at 1 km spatial resolution. In this study, LST obtained at day and nighttime are considered as daily LST minimum and maximum values, respectively (i.e., LSTn, LSTx). LST mean daily value (LSTmean) is computed according to Equation (1).

2.5. MODIS NDVI

MODIS MOD13A2 product, version 6.1, contains 12 data layers, including the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), derived from the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA-AVHRR). This product provides the best available pixel value from all acquisitions within each 16-day period at a spatial resolution of 1 km × 1 km, applying criteria such as low cloud cover, reduced viewing angle, and the highest NDVI value [50].

NDVI values range from −1 to 1: higher values indicate dense and photosynthetically active vegetation, whereas senescent or dead plants, inorganic materials (e.g., rocks), and water bodies typically exhibit low or even negative NDVI values.

For the case of Madagascar, the tiles h21v11, h22v10, and h22v11 were processed using HEG Tool software (version 2.15) to generate raster-format files from the original sinusoidal MOD13A2 projection. Daily NDVI estimates were obtained assuming that NDVI values remained constant throughout each 16-day period.

2.6. Digital Elevation Model

The Digital Elevation Model (DEM) provided by the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM), approximately 30 × 30 m, known as the SRTM-v3 product, was generated from data collected over 11 days in February 2000. The acquisition employed the dual spaceborne imaging radar (SIR-C) and the dual X-band synthetic aperture radar (X-SAR). This dataset, covering latitudes from 60° N to 56° S, is a joint development of the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and was obtained through the Google Earth Engine platform [51]. First, the SRTM-DEM was projected to geographic coordinates and resampled to 1 km × 1 km spatial resolution using bilinear interpolation. Slope and aspect variables were then derived and processed using ArcGIS 10.8.

3. Methods

3.1. Machine-Learning Models

RF (Random Forest) is an ensemble-learning algorithm composed of several tree predictors that employs a technique known as bagging (Bootstrap Aggregating). Each tree predictor or decision tree is constructed randomly from a collection of training data. RF models have the advantage of having low rates of overfitting problems, because the prediction is carried out by averaging all decision trees. Moreover, if a large amount of data is to be processed, RF has the advantage of being able to train the model quickly and efficiently [52].

XGB (eXtreme Gradient Boosting) is a powerful, tree-based ensemble-learning algorithm that employs the gradient boosting framework. Unlike methods that build trees independently (e.g., RF), XGB constructs predictors sequentially, where each new decision tree is trained to correct the residual errors made by the previous ones. The XGB model is widely recognized for its high predictive accuracy and performance [53]. Moreover, its implementation is highly optimized for performance and speed, making it exceptionally efficient for processing large datasets.

MLR (Multiple Linear Regression) models the linear relationship between a dependent variable and multiple predictors, seeking to minimize the sum of squared residuals through the ordinary least squares method. The reliability of this method depends on the independence among predictors. When high correlation exists between them (multicollinearity), the model’s coefficients become unstable, producing large variance and making it difficult to assess the individual effect of each predictor [54].

The implementation of the machine-learning models (RF, XGB, and MLR) was performed using the Scikit-learn (version 1.4.1.post1) library in Python 3.11.5.

3.2. Models Set-Up at 5 km

The first step consists of training the machine-learning models at the native spatial resolution of CHIRTS (i.e., 5 km). To do so, the model inputs—MODIS-like (LSTn, LSTx, LSTmean), SRTM-DEM (Slope, Aspect, Elevation), and NDVI—were upscaled to 5 km using a bilinear resampling method, and observed Tx, Tn, and Tmean were successively used as targets to train the models (RF, XGB, MLR) (Figure 2b).

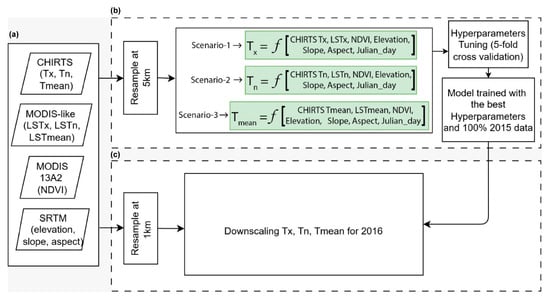

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the air temperature downscaling method showing (a) the considered predictors along with (b) the models’ calibration at 5 km, and (c) the models’ application at 1 km.

In this process, three scenarios are considered. Scenario-1 uses Tx as the target, and CHIRTS (Tx), LSTx, Slope, Aspect, Elevation, and NDVI as regressors; scenario-2 uses Tn as the target and CHIRTS (Tn), LSTn, Slope, Aspect, Elevation, and NDVI as regressors, and scenario-3 uses Tmean as the target and CHIRTS (Tmean), LSTmean, Slope, Aspect, Elevation, and NDVI (Figure 2b). The consideration of scenario-1 and -2 (Tn and Tx) is aimed at filling the actual state-of-the-art on T-dataset spatial downscaling, which is limited to Tmean. This consideration will improve extreme air temperature event monitoring, such as HWs and CWs that rely on Tx and Tn estimates, respectively.

In this first step, the 2015 available daily observations of Tx (n = 6.084), Tn (n = 6.271), and Tmean (n = 5.936) are individually split into two parts (i.e., the training and validation datasets). Each split encompasses 70% and 30% of the total observation number, respectively. It is worth mentioning here that the exact same splitting is used for all scenarios and models to ensure a consistent comparison for all set-ups.

Optimizing hyperparameters is crucial to significantly increase the models’ performance [55] and prevent over- or under-fitting [56]. In this context, the grid-search function, which systematically and automatically reviews each set of hyperparameters values during the model training process, is used for hyperparameters tuning [57]. The hyperparameters calibration is performed using the training dataset with the 5-fold cross-validation, with the RMSE (Equation (2)) as the objective function.

Finally, each model is trained for each scenario (-1, -2, -3), with the optimum hyperparameters combination using the training dataset and validated using the validation dataset. For the validation step, the RMSE, R2, and MAE are considered to assess the model’s training reliability (Equations (2)–(4)):

where is the observed air temperature values, is the air temperature estimated by the models, is the average of the air temperature observations, and n is the total length of the data.

3.3. Downscaling at 1 km

The second step consists of applying the trained model (i.e., 5 km) at the downscaled spatial resolution of 1 km (Figure 2c). The model inputs CHIRTS (Tx, Tn, and Tmean) and SRTM-DEM (Slope, Aspect, Elevation) were upscaled to 1 km using a bilinear resampling method. No resampling process was applied to MODIS-like (LSTn, LSTx, LSTmean) and NDVI, as their native resolution is 1 km. Consequently, for each scenario (-1, -2, and -3), the models (RF, XGB, and MLR) were trained at the 5 km spatial resolution considering the entire observation of the 2015 period and were applied at 1 km spatial resolution to the 2016 period. The models’ predictions at 1 km spatial resolution were compared with observations from the meteorological stations using R2, RMSE, and MAE.

4. Results

4.1. Models Training at 5 km

Table 1 presents the optimum hyperparameters values using the grid-search function for each scenario and RF and XGB models (the MLR model was not included in this table as it does not rely on hyperparameters but on regression coefficients). For both models (i.e., RF, XGB), only one of the considered hyperparameter values remained equal to the one proposed as the default value. In reality, the default value for “bootstrap” and “max_depth” in the RF and XGB models remains the same with and without the hyperparameter optimization (i.e., grid-search function). This result highlights the benefit of such hyperparameters optimization to improve model performance [55] and avoid over- and/or under-fitting issues [56]. In this context, hyperparameters optimization is increasingly used in machine-learning-based studies for land use land cover (LULC), soil humidity, and salinity mapping (i.e., [56,58,59,60]).

Table 1.

Hyperparameter search ranges and optimal values for the two machine-learning models.

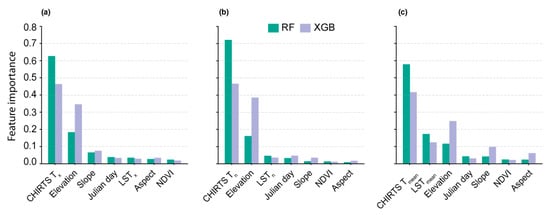

Figure 3 shows the feature importance (FI) obtained for the predictors of the different scenarios (-1, -2, and -3) and models (RF and XGB). It is worth mentioning that such an analysis was not possible for the MLR model due to its specific structure, which relies on regression coefficients.

Figure 3.

FI observed for the RF and XGB models and scenario-1 (a), scenario-2 (b), and scenario-3 (c).

Logically, CHIRTS data (Tx, Tn, and Tmean) were identified as the most contributive variable, with FI values systematically superior to 40% and 50% for both the RF and XGB models. Due to the strong relationship linking air temperature and elevation, elevation was identified as the second most contributive variable in the XGB model across all scenarios (Tx, Tn, and Tmean), whereas it was only the case in scenario-1 and -2 (Tx and Tn) for the RF model. Interestingly, with a FI value superior to 10%, LST contribution was only significant for scenario-3 (Tmean), whereas FI values lower than 10% were observed for scenario-1 and -2 (Tx and Tn). This discrepancy can be explained by the LSTx and LSTn time acquisition, which differ from the observed local time of Tx and Tn, respectively; a temporal mismatch that is attenuated through the average process to derive LSTmean. NDVI low FI scores (<5%) can be explained by the time lag between air temperature and the NDVI temporal dynamic. While air temperature presents high variations from day to day, the NDVI changes are much smoother. Therefore, no relation is expected between air temperature and NDVI at the daily time step. Similar observations apply to Julian day. However, NDVI and Julian day gathered relevant information on Madagascar’s temporal seasonality and bioclimatic regions to adjust the models in space and time.

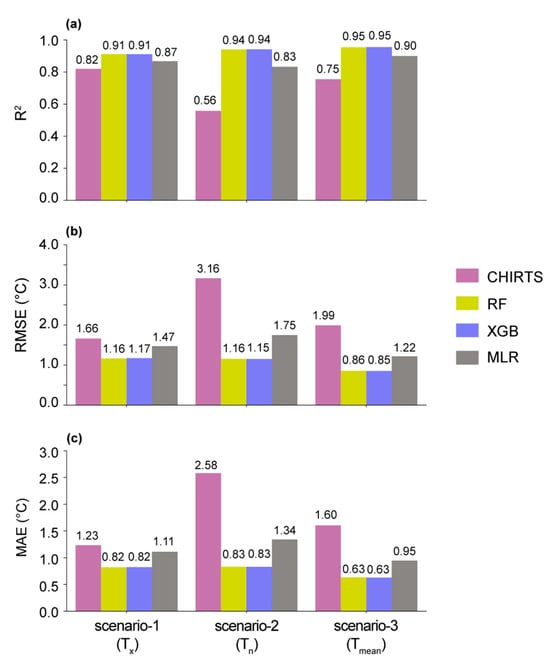

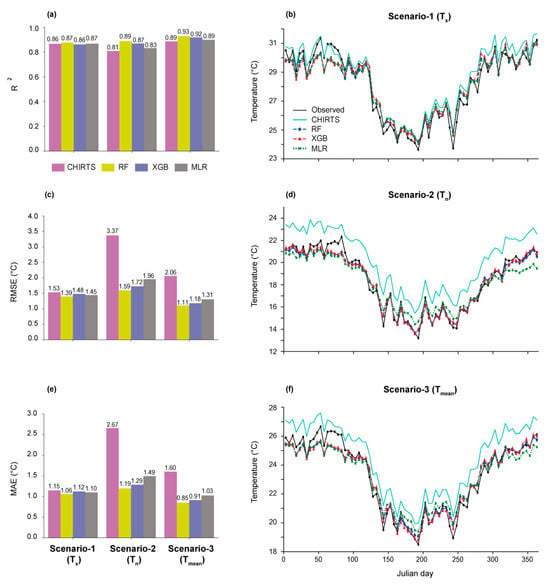

Figure 4 shows the statistical metrics (R2, RMSE, and MAE) obtained for all models (RF, XGB, and MLR) and scenarios (-1, -2, and -3) at 5 km for the validation step with the optimum hyperparameters values (Table 1).

Figure 4.

R2 (a), RMSE (b) and MAE (c) obtained with the validation dataset for 2015 at 5 km spatial resolution for all the considered models (RF, XGB, MLR) and scenarios (-1, -2, -3).

Considering scenario-1 (Tx), an R2 improvement of 11%, 11%, and 6% is observed for RF, XGB, and MLR, respectively. The improvement is even more consequent considering both RMSE and MAE, with an RMSE decrease of 30%, 29.5%, and 11.5%, and a MAE decrease of 33.5%, 33.5%, and 8% observed for RF, XGB, and MLR, respectively. Considering scenario-2 (Tn), the improvements are even more important, with an R2 increase of approximately 68%, 68%, and 48%, a RMSE decrease of approximately 63.5%, 63.5%, and 44.5%, and a MAE decrease of approximately 68%, 68%, and 48% observed for RF, XGB, and MLR, respectively. Considering scenario-3 (Tmean), intermediate improvements are observed as Tmean is obtained from Tn and Tx (Equation (1)).

Overall, all the models improve CHIRTS Tx, Tn, and Tmean estimates, with the RF and XGB models performing better than the MLR model.

4.2. Model Prediction at 1 km

Figure 5 presents the metrics obtained when using the trained models to downscale CHIRTS estimates (Tx, Tn, and Tmean) from 5 km to 1 km for 2016.

Figure 5.

Metrics (R2, RMSE and MAE) obtained with the application of the models (RF, XGB, MLR) at 1 km spatial resolution for 2016, considering scenarios-1, -2, and -3 (a,c,e), along with the 5-days average of mean daily temperature observations (Tx, Tn, and Tmean) derived from all available stations and corresponding pixels (b,d,f).

In scenario-1 (Tx), no improvement is observed in terms of R2, with values ranging between 0.86 and 0.87 before and after the model application. Regarding RMSE (MAE), a slight decrease of 9% (8%), 3% (3%), and 5% (4%) is observed for RF, XGB, and MLR, respectively, in comparison to CHIRTS.

In scenario-2 (Tn), slight improvements of 9%, 7%, and 2% are observed for the R2 value and RF, XGB, and MLR models, respectively, in comparison to CHIRTS. The largest improvements are observed in RMSE (MAE), with a decrease of 53% (55%), 49% (52%), and 42% (44%) for RF, XGB, and MLR, respectively, in comparison to CHIRTS.

Finally, the highest statistical scores are observed for scenario-3, with the RF and XGB models presenting R2 values of 0.92 and 0.93, respectively. In comparison to CHIRTS, a significant improvement is observed on RMSE (and MAE), with a decrease of 47% (47%) and 43% (43%) for RF and XGB, respectively.

Overall, the downscaling process does not significantly improve the R2 score. In reality, both CHIRTS and the model outputs (Tn, Tx, and Tmean) correctly capture the air temperature dynamic (Figure 5b,d,f). The model benefit relies more on the RMSE and MAE decrease (especially for Tn and Tmean), resulting in a significant bias correction of both CHIRTS Tn and Tmean all along the time series (Figure 5d,f).

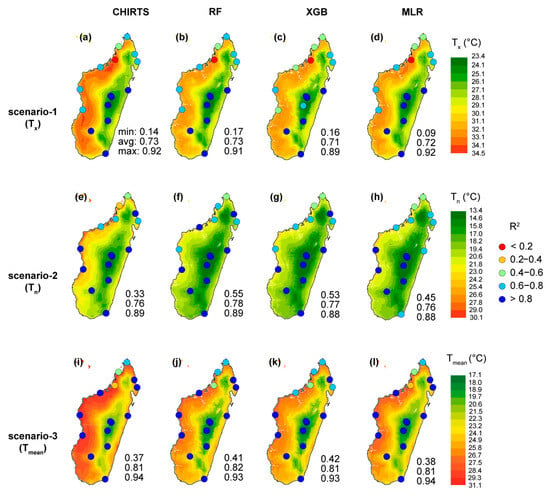

Figure 6 shows the mean daily temperature maps (Tn, Tx, and Tmean), as observed by CHIRTS and all the models and scenarios combination for 2016, along with the R2 obtained at each considered meteorological station.

Figure 6.

R2 obtained at the meteorological stations location for the validation of 2016 data at 1 km spatial resolution for all the considered models (RF, XGB, MLR) and CHIRTS for scenarios-1 (a–d), -2 (e–h), and -3 (i–l). The color maps used as background show the daily mean air temperature average (Tn, Tx, and Tmean) observed for 2016. White pixels are observed due to LST and/or NDVI missing data, preventing the models’ application.

In comparison to CHIRTS, the model outputs lead to a significant decrease in temperature estimates, especially along the western Madagascar coast (Figure 6). This spatial pattern is in line with the overall bias values observed on CHIRTS Tn, Tx, and Tmean estimates (Figure 5). The downscaling from 5 km to 1 km brings much more detail about the air temperature spatial patterns that are shaped by the elevation variations (Figure 5). This feature is in line with the FI, as elevation is one of the most contributive features for all model and scenario combinations (Figure 3). This improvement will support air temperature monitoring in regions with important air temperature changes observed in a reduced space due to topographic features.

Considering scenario-1 (Tx), no R2 improvement is observed in comparison to CHIRTS for all considered models (i.e., RF, XGB, MLR). Even for the stations with the lowest R2 value for CHIRTS (R2 < 0.2) located in the Northern region, no model significantly increased its R2 value. However, when considering scenario-2 (Tn), all the models improved the R2 values at the station location where the lowest R2 values are observed for CHIRTS. More precisely, an R2 improvement of approximately 66.5%, 60.5% and 36.5% is observed for the RF, XGB, and MLR models, respectively, for the station with the lowest R2 score for CHIRTS (R2 = 0.33). According to the respective improvement observed on Tx and Tn estimates, scenario-3 (Tmean) shows slight improvements, mainly for the northern stations, where CHIRTS provides the least reliable Tmean estimates.

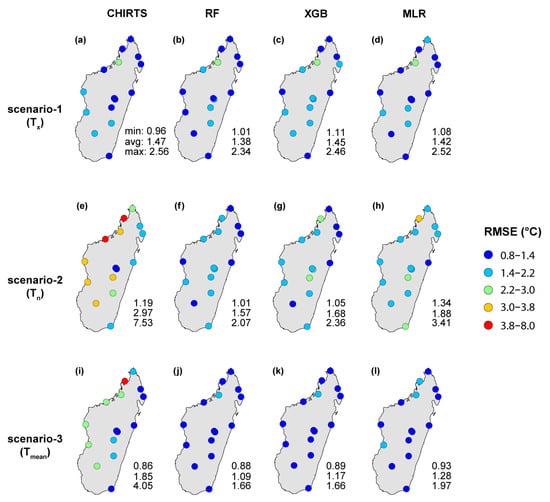

Figure 7 shows the RMSE obtained for CHIRTS and the considered models (i.e., trained on 2015 data) for 2016 at 1 km spatial resolution.

Figure 7.

RMSE obtained at the meteorological stations location for the validation on 2016 data at 1 km spatial resolution for all the considered models (RF, XGB, MLR) and CHIRTS for scenarios-1 (a–d), -2 (e–h), and -3 (i–l).

As observed for R2, the improvement brought by the models is slight to none for the Tx estimates (scenario-1) but significant for the Tn estimates (scenario-2). In reality, for the stations located in the Western and Central regions, the RMSE observed with CHIRTS ranging from 2.2 to 8.0 °C significantly decreased after applying the trained models. This is especially true for the RF model, with all stations presenting RMSE values inferior to 2.2 °C. As a result, when considering the RF model, a RMSE decrease of approximately 47% is observed on average. The improvement significantly increases to 75% for the station with the highest RMSE value for CHIRTS (RMSE = 7.53 °C). The improvement brought by the models on Tn is consequently observed for Tmean (scenario-3). Indeed, a RMSE decrease of approximately 41%, 37%, and 31% is observed for RF, XGB, and MLR in comparison to the average value observed for CHIRTS Tmean average MAE value (MAE = 1.85 °C).

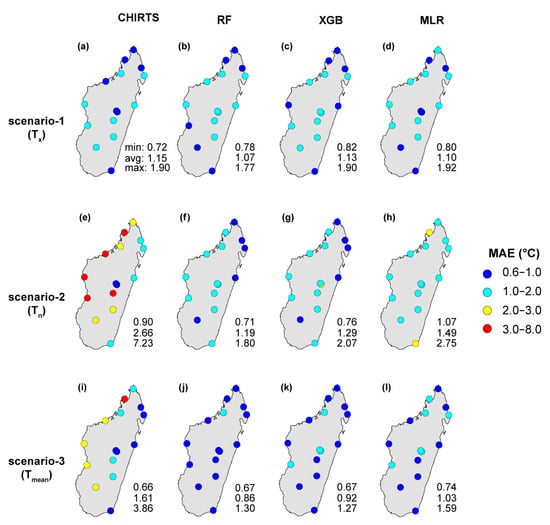

Figure 8 shows the MAE obtained for CHIRTS and the considered models (i.e., trained on 2015 data) for 2016 data at 1 km spatial resolution.

Figure 8.

MAE obtained at the meteorological stations location for the validation on 2016 data at 1 km spatial resolution for all the considered models (RF, XGB, MLR) and CHIRTS for scenarios-1 (a–d), -2 (e–h), and -3 (i–l).

As for R2 and RMSE, the improvement brought by the models is clearly observable for the Tn estimates (scenario-2). In reality, an MAE decrease of approximately 55%, 51.5% and 44% on the average CHIRTS Tn MAE value is observed. As for the RMSE, the improvement is more important for the Western and Central regions, where CHIRTS MAE values range from 2.0 to 8.0 °C, whereas RF MAE values are systematically inferior to 2.0 °C. The improvement observed for the Tn estimates is reflected in Tmean values (scenario-3) with a MAE decrease of approximately 46.5%, 43%, and 36% for the RF, XGB, and MLR models, respectively. When focusing on the station location with the highest MAE value for CHIRTS (MAE = 3.86 °C), the improvement increased to approximately 67%, 67%, and 59% for RF, XGB, and MLR, respectively.

Overall, all the models perform better in correcting the error on CHIRTS Tn than Tx estimates, with RF and XGB models providing more reliable Tn and Tx estimates than the MLR model. With no R2 improvement for all considered scenarios (-1, -2, and -3), no models are able to correct the temporal inconsistency observed in CHIRTS temperature estimates.

5. Discussion

5.1. New Insights

The actual state-of-the-art on T-datasets spatial downscaling is limited to Tmean estimates [25,26,38]. Even if these efforts bring relevant contributions on air temperature monitoring and sensitivity to anthropogenic factors (i.e., LULC, greenhouse gases), at a finer spatial scale, their contribution remains limited regarding extreme temperature events. In reality, the ongoing warming process also comes with an increase in the frequency and intensity of extreme temperature events such as HWs and CWs, threatening sanitary and food security [3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. As HWs and CWs monitoring is based on Tx and Tn, respectively, the ability to monitor Tx and Tn at a finer spatial scale is critical to understanding their dynamics in located sensitive regions such as urbanized and agricultural areas.

By transferring and adapting the available methodological steps for Tmean to Tx and Tn, the results show that spatially improved Tx and Tn estimates can be achieved with these methods. In addition to the benefits regarding HWs and CWs at finer spatial scale, the generated Tn and Tx could be used to retrieve Tmean without the need for the calibration of a specific Tmean modeling set-up (scenario-3), affording the lowest computational time. In this context, Table 2 shows the metrics obtained with Tmean retrieved from Tn and Tx estimates (i.e., scenario-4) obtained through all the considered models and scenarios combined. In comparison to scenario-3, the results show a slight increase (decrease) of R2 (RMSE and MAE) for all the considered models (Table 2). Following this process, the RF model appears as the most reliable option to retrieve Tmean with R2, RMSE, and MAE values of 0.93, 1.09 °C, and 1.02 °C, respectively (Table 2). The slight outperformance of scenario-4 over scenario-3 could be explained by the consideration of the Tn estimate model outputs, which showed the most notable improvement in comparison to CHIRTS Tn estimates (Figure 5).

Table 2.

Metrics comparison between scenario-3 and -4.

5.2. Validation Uncertainties

It is worth mentioning in this section that some limitations regarding the validation step arise from the analysis.

First, during the training step, the training/validation dataset splitting (70%/30%) is based on the total daily observations from all the available stations (n = 20), regardless of their temporal proximity. For a given station and a very limited temporal scale (i.e., week), the daily air temperature observations (Tn, Tx, and Tmean) and considered features (CHIRTS, NDVI, LST) are expected to be very similar. In this context, very similar daily observations are going to be part of the training and validation datasets, so that the models are going to be “well trained” to reproduce what they already learned during their calibration. To minimize this redundancy, the validation at 1 km is based on a training and validation dataset encompassing the 2015 and 2016 observations, respectively. Even if the same meteorological stations are used for each year (2015 and 2016), the daily air temperature observations (Tn, Tx, and Tmean) and considered features (CHIRTS, NDVI, LST) are expected to be contrasted from one year to another. In this context, the models are assessed upon a “less learned” context, ensuring more representative statistical metrics of these models’ potential for long-term monitoring.

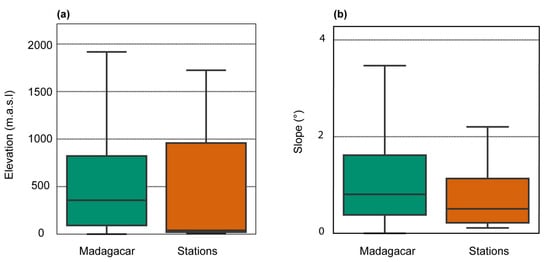

Secondly, the models were trained and validated at meteorological station locations with specific (i) climate, (ii) environmental, and (iii) topographic features that are not representative of the broader range observed at the Madagascar national scale (Figure 9). Whereas Madagascar encompasses topographic features from low-lying plains to high peaks with steep slope areas, the stations used to train/validate the models are mostly located in low-lying flat regions located near the coast due to the presence of airports (Figure 9). In this context, model predictions in a different topographic context than the one used to train the models (i.e., observed at the meteorological station location) are expected to be less reliable. This limitation increases even more considering that the combination of all considered features (i.e., NDVI, LST) presents an even broader range of variation at the national scale than at the meteorological station locations. This feature is especially marked across Madagascar due to the limited number of meteorological stations that cannot represent air temperature sensitivity to environmental components (topography, NDVI, etc.). Therefore, it is worth mentioning that the obtained statistical scores (Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8) are not representative of the model performance across regions (in or outside Madagascar island) with different environmental contexts (i.e., elevation, slope, aspect, LST, NDVI) than those included in the training dataset.

Figure 9.

Boxplot comparison of (a) elevation, and (b) slope observed at the national scale and at the meteorological station locations. The bottom and upper edges of the boxes represent the 25th and 75th percentile values, respectively, whereas the central horizontal line represents the median value.

In this context, assessing the models’ output reliability in an untrained context (temporally and spatially) remains challenging. Leave One Out Cross Validation (LOOCV) could be used to partially overcome this issue by training the model with the observations provided by “n-1” out of the “n” available stations and estimating the air temperature for the stations not included in the training set. Reiterating this operation “n” times would allow assessing the model reliability in the untrained context of the stations successively not included in the training set. However, this approach remains limited to the context (i.e., elevation, slope, aspect, LST, NDVI) observed at the station location used to validate the models. To overcome this issue, a modeling approach such as hydrologic modeling could be an interesting alternative. Indeed, these models rely on evapotranspiration estimates that can be calculated from air temperature estimates [61,62]. Comparing hydrological model outputs (i.e., streamflow) obtained through (i) downscaled/calibrated air temperature estimates and (ii) available interpolated meteorological station observations could highlight the reliability of the proposed method in an “untrained” context. However, the model outputs (i.e., streamflow) are not only sensitive to evapotranspiration estimates (i.e., air temperature estimates), but also to other parameters subject to uncertainties (i.e., precipitation, LULC, model structure).

5.3. Methodological Improvements Recommendations

Despite the overall ability of the proposed modeling approach to improve CHIRTS estimates (Tx, Tn, Tmean) and spatial resolution (i.e., 5 km to 1 km), some considerations could have been taken into account to improve the downscaling procedure.

First, additional variables related to precipitation and wind components could have been considered to improve model output consistency. Wind information has already been considered for ERA-5 air temperature estimate downscaling [25,26,38]. In Italy, wind zonal and meridional components along with wind speed contributed positively to the downscaling of ERA-5 Tmean from 9 km to 1 km [38]. Regarding precipitation, lower air temperatures are generally observed after precipitation events, so that satellite-based precipitation estimates could be used as input. However, their low spatial resolution and uncertainties across Madagascar represent a challenge for their consideration [63]. In this context, a downscaled procedure that has proven efficiency to improve both spatial resolution (up to 1 km) and estimate reliability (i.e., [64]) should be considered before its use.

Secondly, this study only considered the information gathered at the pixel level. However, at a specific location (i.e., pixel), the air temperature variation are not only sensitive to the local condition but also to its neighboring environment. For instance, the topographic features (i.e., elevation, slope, and aspect) observed in the neighboring pixels affect the centered pixel’s exposure to sunlight, wind, rain, humidity, and therefore its air temperature value. To a lesser extent, this observation also applies to LST and NDVI, which also gather relevant information linked to the centered pixel air temperature values. To take this spatial sensitivity into account, a study conducted in China considered the information gathered in a sub-grid of 7 × 7 pixels centered on the pixels including the meteorological station for downscaling of ERA-5 land Tmean estimates [65].

Finally, more complex models such as deep-learning models (i.e., Bidirectional Long Short Term Memory) could be considered so that information on previous and/or following days can be used to improve the air temperature adjustment. Along this line, an alternative should be to apply hydride models based on conditional diffusion models that simultaneously integrate downscaling and bias correction, preserving statistical distributions and improving spatiotemporal consistency in climate estimates [66].

6. Conclusions

This study assessed the benefits of using MODIS LST and NDVI estimates along with topographic features as input variables in machine-learning models (Random Forest—RF; eXtreme Gradient Boosting—XGB, multi-linear regression—MLR) to downscale daily CHIRTS air temperature estimates (maximum, minimum, and mean—Tx, Tn, and Tmean) from 5 km to 1 km. The main results of the study can be summarized as follows:

- The downscaling procedure not only improved the spatial resolution but also the air temperature (Tn, Tx, and Tmean) estimates reliability.

- Considering Tmean, a RMSE decrease of approximately 41%, 37%, and 31% is observed when applying the proposed modeling set-up with RF, XGB, and MLR, respectively.

- For all considered models, a more important air temperature estimates improvement is obtained for Tn than for Tx, with the RF model performing the best, leading to an RMSE improvement of 47.1% and 6.1% for Tn and Tx, respectively.

- The model benefits are not consistent in space: the models perform better in the Western and Central parts of Madagascar. This is partially explained by a higher similarity in the environmental context (i.e., elevation, slope, aspect, LST, NDVI) observed in these regions, with the one described at the meteorological station location used for model calibration.

It is worth mentioning here that the proposed method does not improve the temporal reliability of throughout temperature series, as similar R2 values are observed before and after the model application. This result suggests that the downscaled temperature estimates are prone to improvement. Along these lines, the consideration of neighboring pixels information should lead to improvements as the centered pixel temperature dynamic is expected to not only be sensitive to its local condition, but also to its close surrounding context (i.e., especially topographic context). Similarly, additional variables that may influence temperature variation in time (e.g., precipitation, wind) should be considered as additional model inputs for improving the model outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.U.-F. and F.S.; methodology, E.U.-F. and F.S.; formal analysis, E.U.-F. and F.S.; investigation, E.U.-F., F.S., R.P.-Z., H.R., D.T.-A., M.P.-F., L.B., F.P.M.R., Z.R. and S.D.C.; data curation, E.U.-F. and F.S.; writing—original draft preparation, E.U.-F. and F.S.; writing—review and editing, R.P.-Z., H.R., D.T.-A., M.P.-F., L.B., F.P.M.R., Z.R. and S.D.C.; supervision F.S.; project administration, S.D.C.; funding acquisition, S.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been partly funded by the French Space Agency CNES (Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales) through the TOSCA research program (SuFECiS project) and ANR (Agence Nationale de la Recheche) with the DIGAP project (grant: ANR-23-CE03-0008). The first author acknowledges funding in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior–Brasil (CAPES)–Finance Code 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work used temperature data acquired and shared by DGM (Direction Générale de la Météorologie) of Madagascar and CIRAD (Centre de coopération internationale en recherche agronomique pour le développement) of France.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CHIRTS | Climate Hazards Center InfraRed Temperature with Station daily |

| CIRAD | French Agricultural Research and International Cooperation Organization |

| CW | Cold Waves |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| DGM | General Directorate of Meteorology |

| FI | Feature importance |

| HW | Heat Waves |

| LOOCV | Leave One Out Cross Validation |

| LSTx, LSTn, LSTmean | Land Surface Temperature maximum, minimum, and mean |

| LULC | Land use land cover |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| MODIS | Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| R2 | Coefficient of Determination |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RMSE | Root mean squared error |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

| Tx, Tn, Tmean | Daily maximum, minimum, and mean temperature |

| XGB | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis: Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/climate-change-2021-the-physical-science-basis/415F29233B8BD19FB55F65E3DC67272B (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Intergovernmental Panel On Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781009325844/type/book (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- de Moraes, S.L.; Almendra, R.; Barrozo, L.V. Impact of heat waves and cold spells on cause-specific mortality in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 239, 113861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; FitzGerald, G.; Guo, Y.; Jalaludin, B.; Tong, S. Impact of heatwave on mortality under different heatwave definitions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 2016, 89–90, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Hu, W.; Li, J.; Wei, R.; Lin, J.; Ma, W. Impact of heatwaves on daily outpatient visits of respiratory disease: A time-stratified case-crossover study. Environ. Res. 2019, 169, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Xu, Z.; Bambrick, H.; Prescott, V.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Su, H.; Tong, S.; Hu, W. Cardiorespiratory effects of heatwaves: A systematic review and meta-analysis of global epidemiological evidence. Environ. Res. 2019, 177, 108610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brás, T.A.; Seixas, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Jägermeyr, J. Severity of drought and heatwave crop losses tripled over the last five decades in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 065012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandio, A.A.; Dash, D.P.; Nathaniel, S.P.; Sargani, G.R.; Jiang, Y. Mitigation pathways towards climate change: Modelling the impact of climatological factors on wheat production in top six regions of China. Ecol. Model. 2023, 481, 110381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morignat, E.; Gay, E.; Vinard, J.-L.; Sala, C.; Calavas, D.; Hénaux, V. Impact of heat and cold waves on female cattle mortality beyond the effect of extreme temperatures. J. Therm. Biol. 2018, 78, 374–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brás, T.A.; Simoes, S.G.; Amorim, F.; Fortes, P. How much extreme weather events have affected European power generation in the past three decades? Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 183, 113494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amou, M.; Gyilbag, A.; Demelash, T.; Xu, Y. Heatwaves in Kenya 1987–2016: Facts from CHIRTS High Resolution Satellite Remotely Sensed and Station Blended Temperature Dataset. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyilbag, A.; Amou, M.; Tulcan, R.X.S.; Zhang, L.; Demelash, T.; Xu, Y. Characteristics of Enhanced Heatwaves over Tanzania and Scenario Projection in the 21st Century. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragatoa, D.S.; Ogunjobi, K.O.; Klutse, N.A.B.; Okhimamhe, A.A.; Eichie, J.O. A change comparison of heat wave aspects in climatic zones of Nigeria. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccherini, G.; Russo, S.; Ameztoy, I.; Marchese, A.F.; Carmona-Moreno, C. Heat waves in Africa 1981–2015, observations and reanalysis. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 17, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demortier, A.; Bozkurt, D.; Jacques-Coper, M. Identifying key driving mechanisms of heat waves in central Chile. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 57, 2415–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satgé, F.; Pillco, R.; Molina-Carpio, J.; Mollinedo, P.P.; Bonnet, M.-P. Reliability of gridded temperature datasets to monitor surface air temperature variability over Bolivia. Int. J. Climatol. 2023, 43, 6191–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, M. Accuracy assessment of temperature trends from ERA5 and ERA5-Land. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelaro, R.; McCarty, W.; Suárez, M.J.; Todling, R.; Molod, A.; Takacs, L.; Randles, C.A.; Darmenov, A.; Bosilovich, M.G.; Reichle, R.; et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 2017, 30, 5419–5454. Available online: https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/clim/30/14/jcli-d-16-0758.1.xml (accessed on 31 July 2025). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Verma, S.; Bhatla, R.; Chandel, A.S.; Singh, J.; Payra, S. Validation of Surface Temperature Derived From MERRA-2 Reanalysis Against IMD Gridded Data Set Over India. Earth Space Sci. 2020, 7, e2019EA000910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetzner, D.; Thomas, E.; Allen, C. A Validation of ERA5 Reanalysis Data in the Southern Antarctic Peninsula—Ellsworth Land Region, and Its Implications for Ice Core Studies. Geosciences 2019, 9, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xie, A.; Qin, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, B.; Wang, Y. An Assessment of ERA5 Reanalysis for Antarctic Near-Surface Air Temperature. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Xiao, W.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, X.; Hui, F.; Zhao, J. Evaluation of 2-m Air Temperature and Surface Temperature from ERA5 and ERA-I Using Buoy Observations in the Arctic during 2010–2020. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleixner, S.; Demissie, T.; Diro, G.T. Did ERA5 Improve Temperature and Precipitation Reanalysis over East Africa? Atmosphere 2020, 11, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdin, A.; Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Tuholske, C.; Grace, K. Development and validation of the CHIRTS-daily quasi-global high-resolution daily temperature data set. Sci. Data 2020, 7, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blizer, A.; Glickman, O.; Lensky, I.M. Comparing ML Methods for Downscaling Near-Surface Air Temperature over the Eastern Mediterranean. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Erell, E.; Hough, I.; Rosenblatt, J.; Just, A.C.; Novack, V.; Kloog, I. Estimating near-surface air temperature across Israel using a machine learning based hybrid approach. Int. J. Climatol. 2020, 40, 6106–6121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Serrano, F.; López-Moreno, J.I.; Azorin-Molina, C.; Alonso-González, E.; Aznarez-Balta, M.; Buisán, S.T.; Revuelto, J. Elevation Effects on Air Temperature in a Topographically Complex Mountain Valley in the Spanish Pyrenees. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhabl, M.; Alkam, D. Impact of Vegetation on Thermal Conditions Outside, Thermal Modeling of Urban Microclimate, Case Study: The Street of the Republic, Biskra. Energy Procedia 2012, 18, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, B.; Cleverly, J.; Liu, D.L.; Feng, P.; Zhang, H.; Huete, A.; Yang, X.; Yu, Q. Creating New Near-Surface Air Temperature Datasets to Understand Elevation-Dependent Warming in the Tibetan Plateau. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Bi, X.; Luan, Q.; Li, Z. Estimation of Daily and Instantaneous Near-Surface Air Temperature from MODIS Data Using Machine Learning Methods in the Jingjinji Area of China. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.; Lű, A.; Jia, S. Estimation of daily maximum and minimum air temperature using MODIS land surface temperature products. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 130, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benali, A.; Carvalho, A.C.; Nunes, J.P.; Carvalhais, N.; Santos, A. Estimating air surface temperature in Portugal using MODIS LST data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 124, 108–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Z.; Cai, W.H.; Yang, J. Evaluation of MODIS Land Surface Temperature Data to Estimate Near-Surface Air Temperature in Northeast China. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otgonbayar, M.; Atzberger, C.; Mattiuzzi, M.; Erdenedalai, A. Estimation of Climatologies of Average Monthly Air Temperature over Mongolia Using MODIS Land Surface Temperature (LST) Time Series and Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, M.; Ninyerola, M.; Batalla, M.; Pesquer, L.; Pons, X. Improving Mean Minimum and Maximum Month-to-Month Air Temperature Surfaces Using Satellite-Derived Land Surface Temperature. Remote. Sens. 2017, 9, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebbar, B.; Khabba, S.; Merlin, O.; Simonneaux, V.; Hachimi, C.E.; Kharrou, M.H.; Chehbouni, A. Machine-Learning-Based Downscaling of Hourly ERA5-Land Air Temperature over Mountainous Regions. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, D.H.; Macready, W.G. No free lunch theorems for optimization. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 1997, 1, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhakare, S.; Dal Gesso, S.; Venturini, M.; Zardi, D.; Trentini, L.; Matiu, M.; Petitta, M. Intercomparison of Machine Learning Models for Spatial Downscaling of Daily Mean Temperature in Complex Terrain. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadross, M.; Randriamarolaza, L.; Rabefitia, Z.; Yip, Z.K. Climate Change in Madagascar, Recent Past and Future; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harrington, L.J.; Wolski, P.; Pinto, I.; Ramarosandratana, A.M.; Barimalala, R.; Vautard, R.; Philip, S.; Kew, S.; Singh, R.; Heinrich, D.; et al. Limited role of climate change in extreme low rainfall associated with southern Madagascar food insecurity, 2019–2021. Environ. Res. Clim. 2022, 1, 021003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornet, A. Essai de Cartographie Bioclimatique à Madagascar; Orstom: Paris, France, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank Poverty Headcount Ratio at National Poverty Lines (% of Population). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.NAHC (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Carrière, S.D.; Health, T.; Rakotomandrindra, P.F.M.; Ollivier, C.; Rajaomahefasoa, R.E.; Rakoto, H.A.; Lapègue, J.; Rakotoarison, Y.E.; Mangin, M.; Kempf, J.; et al. Long-term groundwater resource observatory for Southwestern Madagascar. Hydrol. Process. 2021, 35, e14108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramahaimandimby, Z.; Randriamaherisoa, A.; Jonard, F.; Vanclooster, M.; Bielders, C.L. Reliability of Gridded Precipitation Products for Water Management Studies: The Case of the Ankavia River Basin in Madagascar. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Peterson, S.; Shukla, S.; Davenport, F.; Michaelsen, J.; Knapp, K.R.; Landsfeld, M.; Husak, G.; Harrison, L.; et al. A High-Resolution 1983–2016 Tmax Climate Data Record Based on Infrared Temperatures and Stations by the Climate Hazard Center. J. Clim. 2019, 32, 5639–5658. Available online: https://journals.ametsoc.org/view/journals/clim/32/17/jcli-d-18-0698.1.xml (accessed on 3 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Lu, N.; Jiang, H.; Qin, J.; Yao, L. Filling Gaps of Monthly Terra/MODIS Daytime Land Surface Temperature Using Discrete Cosine Transform Method. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, A.; Liang, S.; Wang, D.; Mallick, K.; Zhou, S.; Hu, T.; Xu, S. Advances in Methodology and Generation of All-Weather Land Surface Temperature Products From Polar-Orbiting and Geostationary Satellites: A comprehensive review. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2024, 12, 218–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Li, D. A simple retrieval method of land surface temperature from AMSR-E passive microwave data—A case study over Southern China during the strong snow disaster of 2008. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2011, 13, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Asrar, G.R. A global seamless 1 km resolution daily land surface temperature dataset (2003–2020). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 651–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didan, K. MODIS/Terra Vegetation Indices 16-Day L3 Global 1km SIN Grid V061. NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center. 2021. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/data/catalog/lpcloud-mod13a2-061 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

- Farr, T.G.; Rosen, P.A.; Caro, E.; Crippen, R.; Duren, R.; Hensley, S.; Kobrick, M.; Paller, M.; Rodriguez, E.; Roth, L.; et al. The Shuttle Radar Topography Mission. Rev. Geophys. 2007, 45, RG2004. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2005RG000183 (accessed on 26 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2939672.2939785 (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Wu, W.; Liu, H.; Zhang, W.; Hu, J. Identifying Dynamic Changes in Water Surface Using Sentinel-1 Data Based on Genetic Algorithm and Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandak, S.; Movahedi Naeini, S.A.R.; Komaki, C.B.; Verrelst, J.; Kakooei, M.; Mahmoodi, M.A. Satellite-Based Estimation of Soil Moisture Content in Croplands: A Case Study in Golestan Province, North of Iran. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, L.; Mohammadi, F.G.; Rezapour, S.; Ohland, M.W.; Amini, M.H. Search Algorithms for Automated Hyper-Parameter Tuning. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.14677. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2104.14677 (accessed on 3 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Taghadosi, M.M.; Hasanlou, M.; Eftekhari, K. Retrieval of soil salinity from Sentinel-2 multispectral imagery. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 52, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, H.; Wu, W.; Zhan, L.; Wei, J. Mapping Rice Paddy Based on Machine Learning with Sentinel-2 Multi-Temporal Data: Model Comparison and Transferability. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.H.; Pham, L.T.H.; Dang, T.D.; Tran, D.D.; Dinh, T.Q. Application of Sentinel-1 data in mapping land-use and land cover in a complex seasonal landscape: A case study in coastal area of Vietnamese Mekong Delta. Geocarto Int. 2022, 37, 3743–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, G.H.; Samani, Z.A. Reference Crop Evapotranspiration from Temperature. Appl. Eng. Agric. 1985, 1, 96–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornthwaite, C.W. An Approach toward a Rational Classification of Climate. Geogr. Rev. 1948, 38, 55–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ollivier, C.C.; Carrière, S.D.; Heath, T.; Olioso, A.; Rabefitia, Z.; Rakoto, H.; Oudin, L.; Satgé, F. Ensemble precipitation estimates based on an assessment of 21 gridded precipitation datasets to improve precipitation estimations across Madagascar. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 47, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medrano, S.C.; Satgé, F.; Molina-Carpio, J.; Zolá, R.P.; Bonnet, M.-P. Downscaling Daily Satellite-Based Precipitation Estimates Using MODIS Cloud Optical and Microphysical Properties in Machine-Learning Models. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Du, J.; Ren, J.; Hu, Q.; Qin, F.; Mu, W.; Hu, J. Improving the ERA5-Land Temperature Product through a Deep Spatiotemporal Model That Uses Fused Multi-Source Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aich, M.; Hess, P.; Pan, B.; Bathiany, S.; Huang, Y.; Boers, N. Conditional diffusion models for downscaling & bias correction of Earth system model precipitation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.14416. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/2404.14416 (accessed on 3 September 2025). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).