Abstract

Wetlands are an important natural source of methane (CH4), so it is important to quantify how their emissions may vary under future climate change conditions. The Qinghai–Tibet Plateau contains more than a third of China’s wetlands. Here, we simulated temporal and spatial variation in CH4 emissions from natural wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau from 2008 to 2100 under Representative Concentration Pathways (RCP) 2.6, 4.5, and 8.5. Based on the simulation results of the TRIPLEX-GHG model forced with data from 24 CMIP5 models of global climate, we predict that, assuming no change in wetland distribution on the Plateau, CH4 emissions from natural wetlands will increase by 35%, 98% and 267%, respectively, under RCP 2.6, 4.5 and 8.5. The predicted increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration will contribute 10–28% to the increased CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Plateau by 2100. Emissions are predicted to be majorly in the range of 0 to 30.5 g C m−2·a−1 across the Plateau and higher from wetlands in the southern region of the Plateau than from wetlands in central or northern regions. Under RCP8.5, the methane emissions of natural wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau increased much more significantly than that under RCP2.6 and RCP4.5.

1. Introduction

Methane (CH4) is the second most abundant anthropogenically directly influenced greenhouse gas after carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. Since the industrial revolution, atmospheric CH4 concentration has more than doubled, with an average annual increase of 0.8% to 1.1% [1]. CH4 accounts for about 20% of the warming induced by long-lived greenhouse gases since pre-industrial times, and its emission forces radiation of 0.97 W·m−2 (range, 0.79–1.2 W·m−2) [2]. During the 1980s, atmospheric CH4 concentration increased at an annual rate of 1%, while this rate decreased to 0.7% in the 1990s [3]. In the late 1990s, atmospheric concentration of CH4 showed an increasing rate of zero and remained almost constant from 1999 to 2006. The globally averaged dry mole fraction of methane has increased rapidly since 2007 [4,5], and its growth even accelerated in 2014 [6,7], with an annual growth rate of 12.7 ± 0.5 ppb [6]. The reason for the rapid methane growth in the atmosphere is currently under debate and discussed in several studies [5,8,9,10]. The abnormal change of CH4 concentration has attracted wide attention all over the world, so it has important theoretical and practical significance for the future research of CH4 emissions.

CH4 from wetlands accounts for 70% of all natural CH4 emissions and 24.8% of global CH4 emissions [11]. About 10% of the world’s wetlands lie in China, where they occupy 304,849 km2 and contribute 1.2–3.2% of global CH4 emissions from wetlands [12]. More than a third of China’s wetlands lie on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau [13], the world’s highest plateau with an average elevation of 4000 m. The unique geographical location and climatic conditions of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau mean plenty of annual sunlight and slow decomposition of soil organic matter, which have made the Plateau a huge reservoir of soil carbon for thousands of years [14].

CH4 emission is known to depend on temperature, water level, vegetation, and the substrate, so future climate change and atmospheric CO2 concentration will affect CH4 emissions from wetlands, but many of the details and underlying processes remain unclear [15]. One study of CH4 fluxes on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau from 1949 to 2008 concluded that climate change is the main factor affecting the CH4 fluxes [16]. CH4 emissions have been shown to correlate positively with (a) soil temperature, which itself depends on air temperature; and (b) water level depth, which in turn depends on precipitation [17]. For example, rising temperatures at intermediate and high latitudes caused a 7% increase in CH4 emissions from wetlands from 2003 to 2007 [18].CH4 emissions from wetlands also show a positive association with atmospheric CO2 concentration: an increase in CO2 concentration from 463 to 780 ppm will led to a 13.2% increase in CH4 emissions [19].

The methods used to estimate CH4 emissions from wetlands in recent decades including: (a) a bottom-up approach, in which global or regional emissions were extrapolated from measured fluxes at certain sites or simulated by process-based models based on environmental factors; and (b) a top-down approach, in which inverse models rely on atmospheric observations to model the distribution of CH4 sources and sinks [2,20]. While the top-down method can be quite effective for simulating emissions over large areas, it is susceptible to errors due to incomplete data and amplification [21]. In contrast, process-based modeling can be more reliable because it calibrates model parameters based on experimental measurements, and it takes account of the complexity of CH4 emissions [22]. Process-based model is an important method to estimate regional and global wetland CH4 emissions and has made great progress in the past 25 years [22,23,24,25,26].

Several studies have estimated CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau for periods from 1995 to 2005 (2.47 TgC·a−1) [27], 1949–2008 (0.06 TgC·a−1) [16], 1979 to 2012 (0.96 TgC·a−1) [28], and 2000 to 2010 (0.22 TgC·a−1) [29]. However, CH4 emissions from Plateau wetlands under future climate conditions remain quite uncertain. In this study, based on a processed model of TRIPLEX-GHG [23], we predicted spatial and temporal patterns of CH4 emissions from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau wetlands from 2008 to 2100 under three concentration pathways (RCPs) of future climate change scenarios.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau have a surface area of 133,000 km2 and comprise alpine marshes, alpine meadow and alpine lakes. These wetlands have important ecological regulation functions, such as water supply and climate regulation. However, climate change and the freeze-thawing of permafrost have substantially degraded wetlands on the Plateau. The average elevation of this area is more than 4000 m, high and special terrain, forming a unique plateau climate. In most areas of the Plateau, the monthly maximal temperature is below 15 °C. Annual precipitation across the Plateau is about 400 mm, and this can vary substantially across the regions.

2.2. Model Description

TRIPLEX-GHG is a new-generation process model for quantifying greenhouse gas emissions of terrestrial ecosystems [30]. The TRIPLEX-GHG model integrates a variety of terrestrial ecosystem processes, including land surface processes, canopy physiology, vegetation phenology, vegetation dynamics and terrestrial carbon balance [30,31]. It also incorporates wetland CH4 production, consumption and transmission processes, based on biogeochemistry and dynamic water table modules [23]. In fact, the TRIPLEX-GHG model comprehensively considers the influence of soil temperature, soil redox potential, soil pH and other factors on CH4 emission from wetlands. The model has proven effective at quantitatively simulating CH4 emissions on different spatial and temporal scales [32]. The ratio of CH4 release rate to CO2 release rate (r) and the temperature control parameter of CH4 production (Q10P) are sensitive parameters in the model, and we adapted values from our previous work in the present study [23,32,33]. The TRIPLEX-GHG model has been well calibrated and validated for simulating CH4 emissions from wetlands in China [34] and elsewhere [23,32] under past climate conditions. This previous work provided a basis for predicting CH4 emissions from Plateau wetlands under future climate conditions [23,32,33,34].

2.3. RCPs and Model Input Data

The IPCC Fifth Assessment relies on RCPs 2.6, 4.5, 6.0 and 8.5 to model greenhouse gas concentrations in the future. The numbers refer to forced radiation levels (in W·m−2) predicted for 2100. For the present study, we applied RCPs 2.6, 4.5, and 8.5 (Table 1). RCP 2.6 is the low-end emission pathway, representing an active response to global climate change in order to keep global warming within 2 °C by the end of this century. RCP 4.5 is the intermediate, stable emission pathway, in which anthropogenic carbon emissions will decline after 2080 but still exceed the allowable value. RCP 8.5 is the high-end emission pathway, in which atmospheric CO2 concentrations will be 3–4 times higher in 2100 than before the Industrial Revolution [1].

Table 1.

Representative concentration pathways used in the present study.

Modeling for the period 2008–2100 was performed under these three RCPs using data from 24 global climate models in the fifth Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5, Table 2). After several phases of the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (e.g., CMIP1, CMIP2 and CMIP3), the Project Phase 5 was launched in September 2008 [35] and widely used in global change studies. The distribution of wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau was held constant at the distribution in 2008 [36]. Climate change data include monthly precipitation (mm), monthly average temperature (°C), monthly maximum temperature (°C), monthly minimum temperature (°C), monthly average cloud coverage (%), monthly average relative humidity (%) and monthly average surface wind speed (m·s−1). In this study, interpolation software ANUSPLIN 4.4 [37] was used to interpolate the data, and they were standardized to a resolution of 0.5º × 0.5º for all 24 CMIP5 models.

Table 2.

Basic information about the 24 climate models in the CMIP5 used in the present study.

In order to evaluate the influence of atmospheric CO2 concentration change on CH4 emission, simulations were repeated after holding atmospheric CO2 concentrations constant throughout the period 2008–2100, at the values in 2008. Annual CH4 emission anomalies were calculated as the difference between values for the period 2008–2100 and values for 2008. The resulting anomalies were added to our previous estimate of CH4 emissions from the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau wetlands in 2008 (0.24 TgC·a−1) [34].

3. Results

3.1. Future Annual Variation in CH4 Emissions from Wetlands on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau

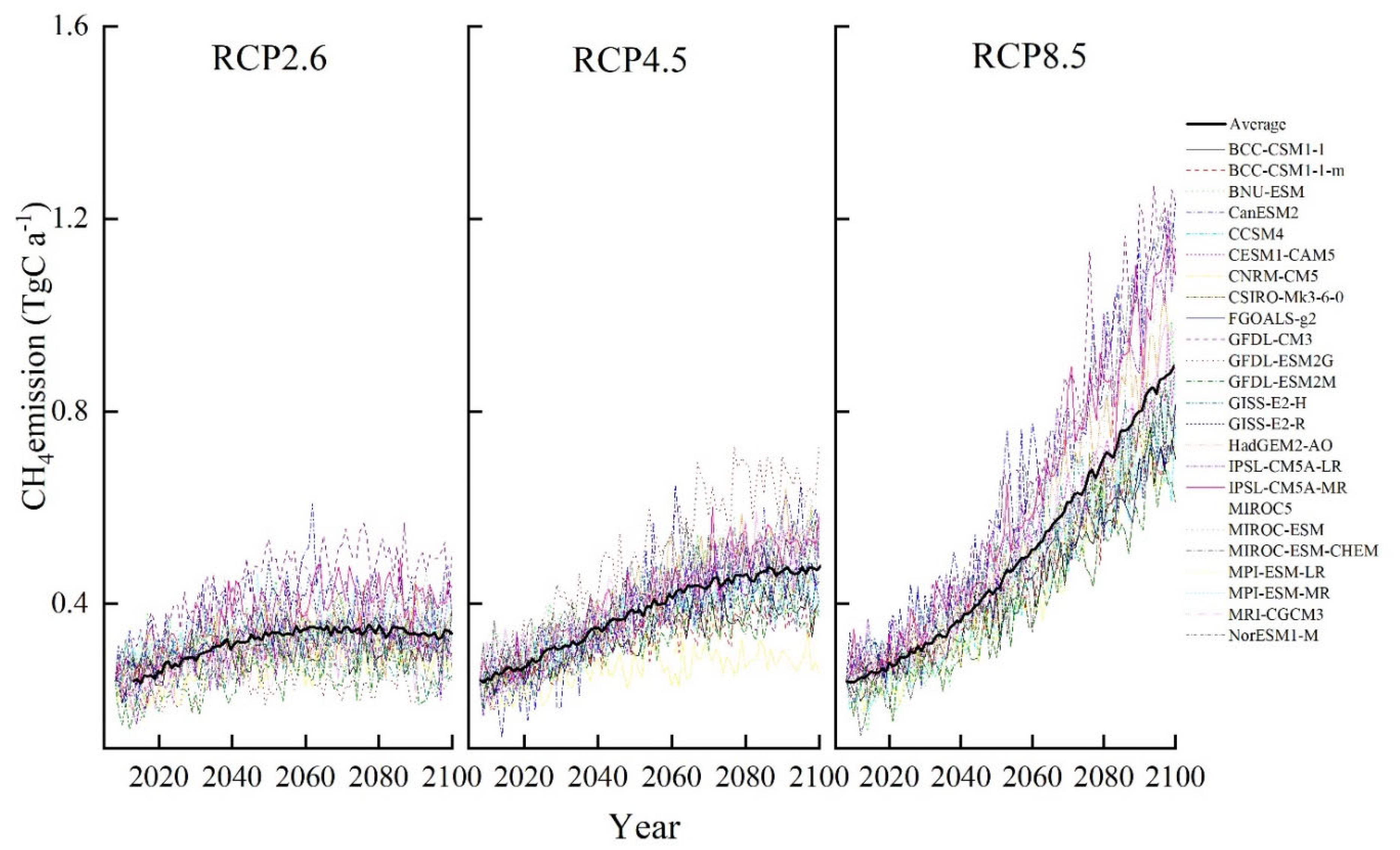

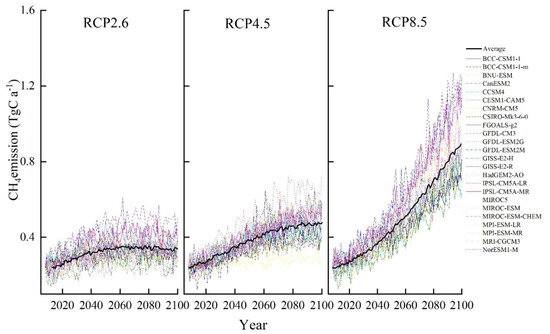

Variation in annual CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau during the period 2008–2100 were shown in Figure 1. In the RCP 2.6 scenario, CH4 emissions first rose slowly, then remained relatively constant, and finally, declined. The annual average maximum emission reached 0.35 TgC·a−1 in 2064, and the average CH4 emission was 0.32 TgC·a−1 in 2100, an increase of 35% over the current level. In the RCP 4.5 scenario, emissions rose rapidly at first, then they rose slowly, and finally they stabilized. The annual average maximum emission was 0.49 TgC·a−1 in 2091 and the average CH4 emission was 0.47 TgC·a−1 in 2100, an increase of 98% over the current level. In the RCP 8.5 scenario, emissions increased continuously, reaching annual average maximum emission of 0.88 TgC·a−1 in 2100, an increase of 267% over the current level.

Figure 1.

Variation in annual CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau during the period 2008–2100. CO2 concentrations were assumed to rise up to 490–1370 × 10−6 by 2100. Results for the 24 CMIP5 models are shown, and the thick black line indicates the average across all models.

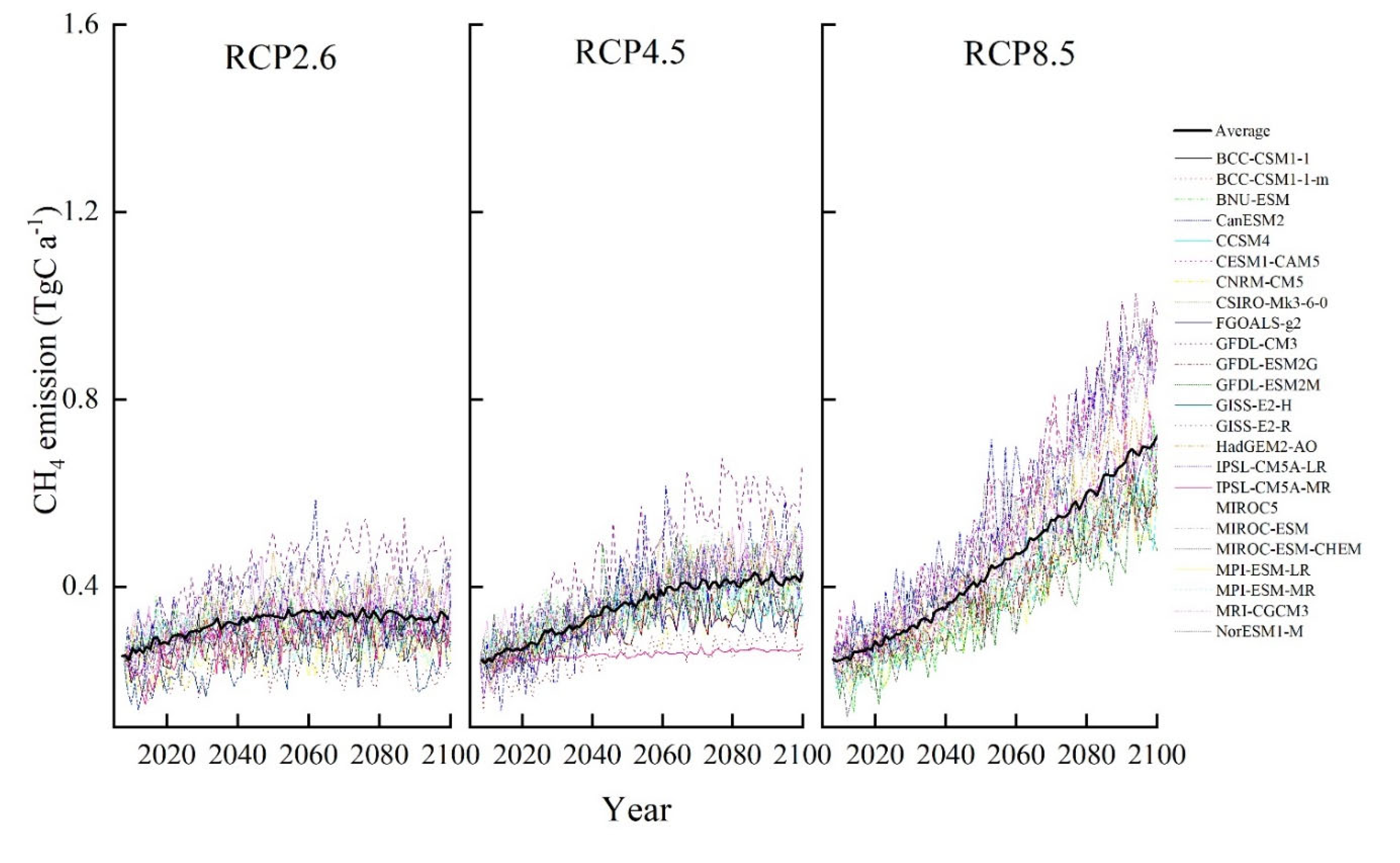

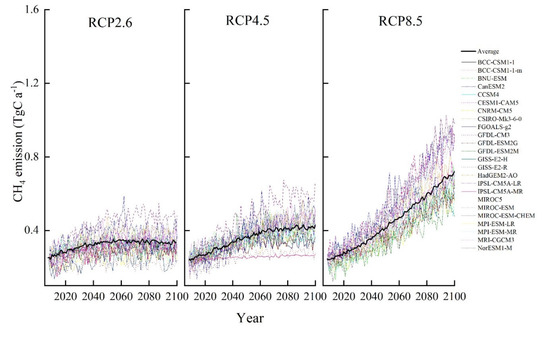

Next, we considered only the effects of future climate change on CH4 emissions, by holding atmospheric CO2 concentration constant throughout the period 2008–2100 (Figure 2). In the RCP 2.6 scenario, average CH4 emission in 2100 was 0.29 TgC·a−1, an increase of 22% over the current level but a decrease of 9% below the level estimated in the presence of elevated CO2 concentration. In the RCP 4.5 scenario, average CH4 emission in 2100 was0.39 TgC·a−1, an increase of 61% over the current level but a decrease of 17% below the level estimated in the presence of elevated CO2. In the RCP 8.5 scenario, average CH4 emission in 2100 was 0.69 TgC·a−1, an increase of 185% over the current level, but a decrease of 22% below the level estimated in the presence of elevated CO2.

Figure 2.

Variation in annual CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau during the period 2008–2100. CO2 concentrations were held constant at 2008 levels. Results for the 24 CMIP5 models are shown, and the thick black line indicates the average across all models.

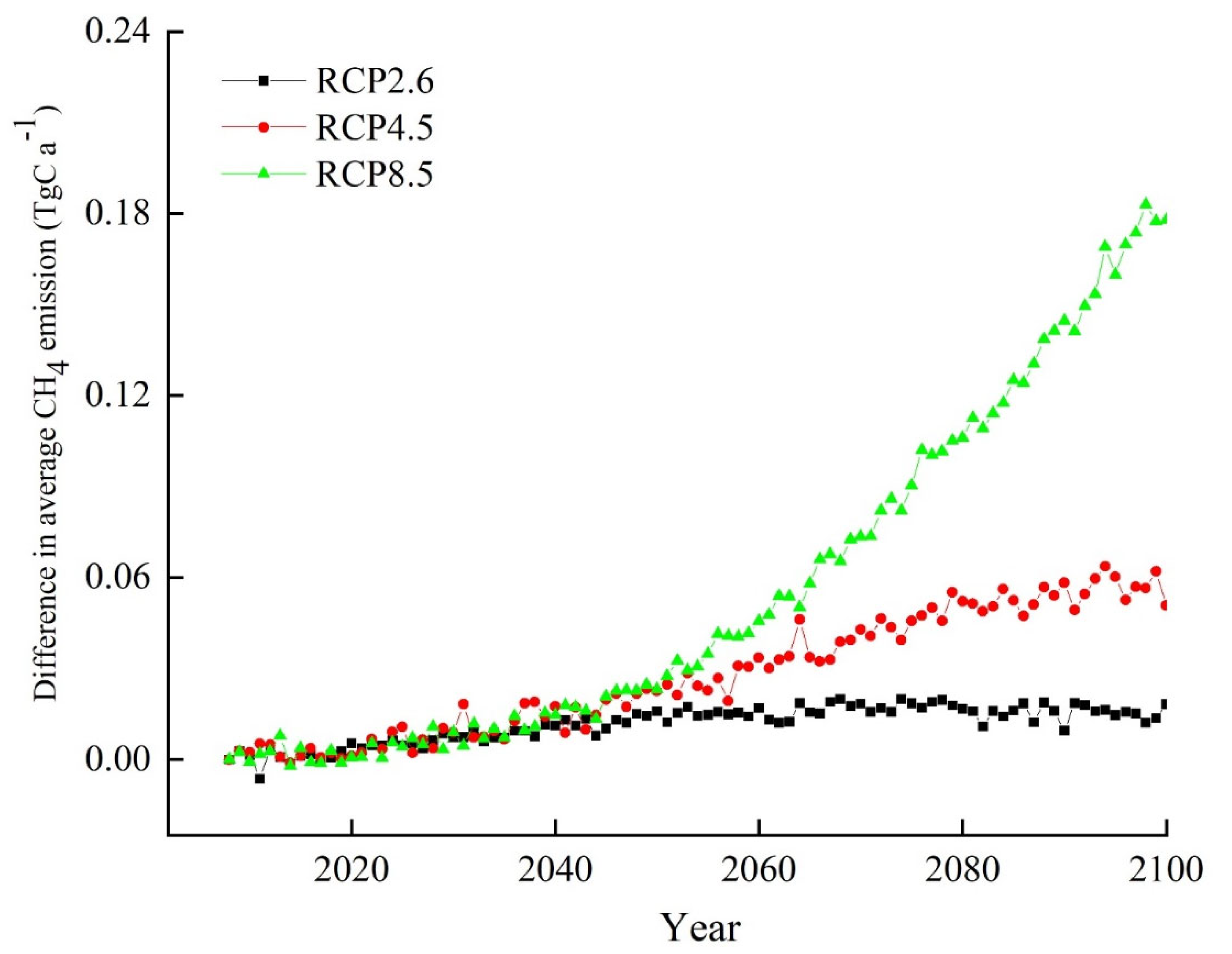

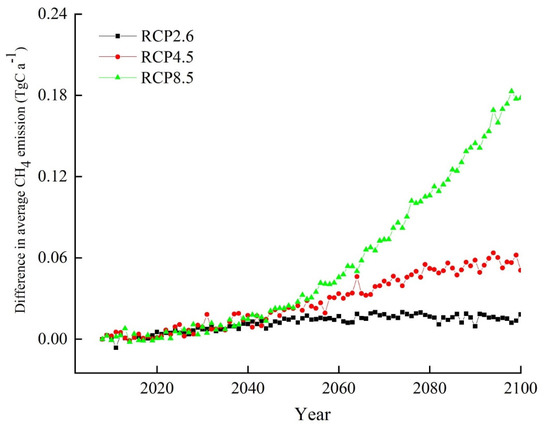

In fact, the difference in average annual CH4 emission between the situations when CO2 concentration was allowed to rise or was held constant increased over time under all three RCPs (Figure 3). Under the scenario of RCP2.6, the emissions difference increased from 2008 to 2100 by 0.02TgC·a−1, showing a slight upward trend. Under the scenario of RCP4.5, the emissions difference is enhanced to 0.06TgC·a−1 by 2100, then slowly rises in the early and middle part of the 21st century and rises rapidly in the later part. Under the scenario of RCP8.5, the CH4 emission difference shows a linear upward trend, and is enhanced to 0.18TgC·a−1 in 2100. The rate of increase per year was the slowest in RCP 2.6 and the fastest in RCP 8.5. Under all three RCPs, elevated CO2 enhanced CH4 emissions more in the second half of the 21st century than in the first half.

Figure 3.

Difference in average CH4 emission from wetlands when models stipulated increasing or constant CO2. Average values were calculated across all 24 CMIP5 models, and results under each RCP are shown. Positive differences indicate higher average emission with increasing CO2.

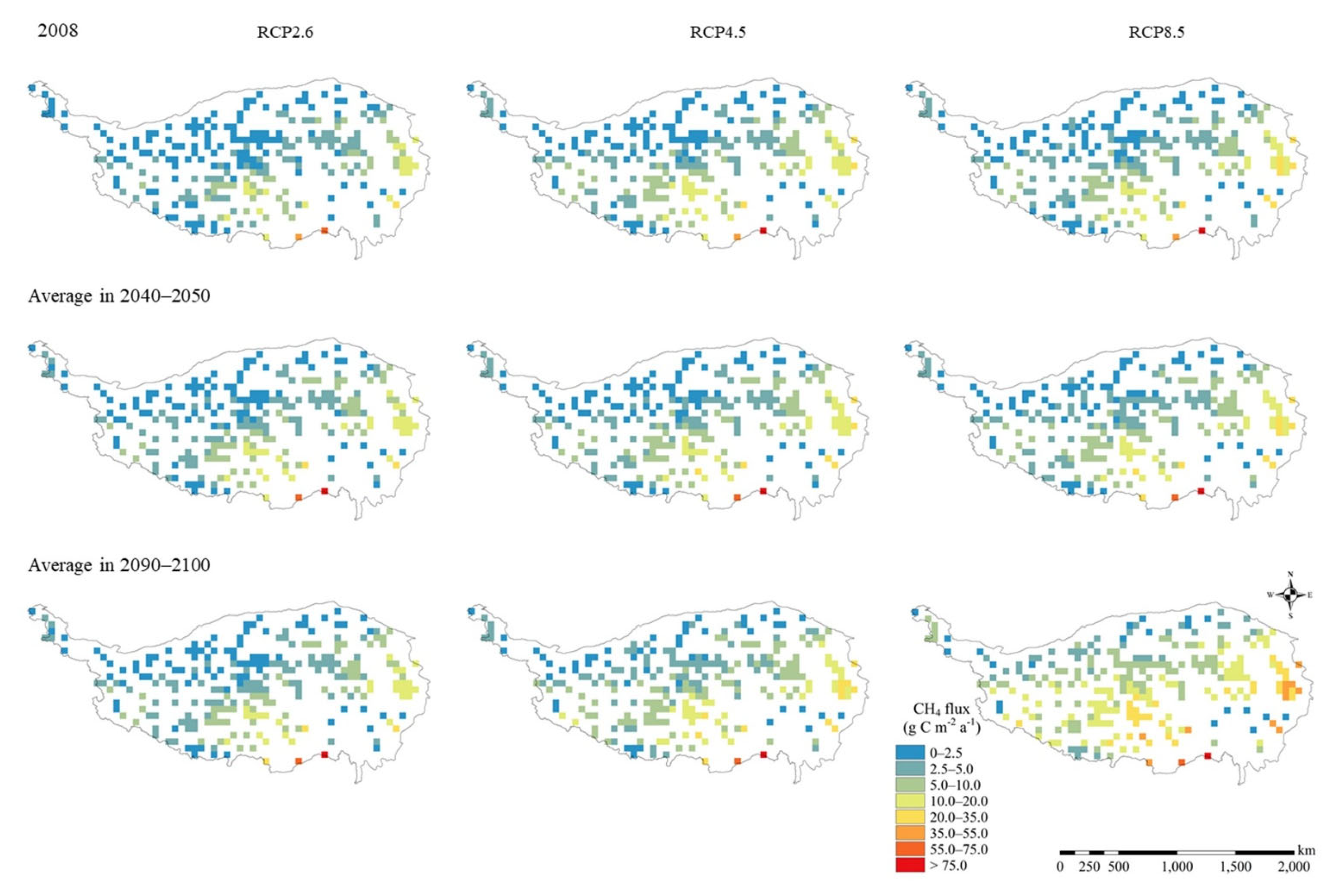

3.2. Spatial Distribution of Future CH4 Emissions from Wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

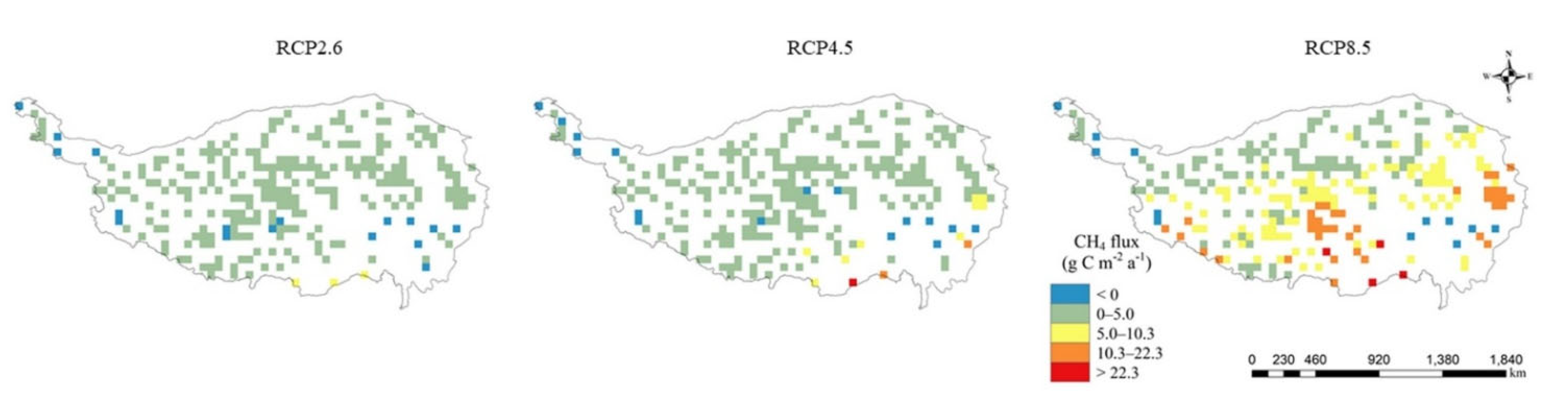

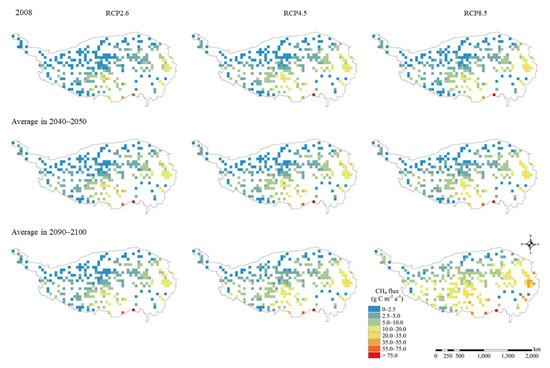

The spatial distribution of annual CH4 emissions, averaged across all 24 models, was calculated for the periods 2008, 2040–2050 and 2090–2100 (Figure 4). In general, CH4 fluxes were smaller in the western part than the eastern part of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, and the emission rates of most wetlands were 0–10.5 gC·m−2·a−1. In the RCP 2.6 scenario, the spatial pattern of CH4 emission rate was similar across the three time periods. In the RCP 4.5 scenario, the annual average CH4 emission rate was significantly higher in the last time period than during the previous two periods. In the RCP 8.5 scenario, the annual average CH4 emission rate in most wetland areas was significantly higher than in the other two RCP scenarios at all three time periods. Under scenarios of RCP2.6, RCP4.5, and RCP8.5, the highest CH4 emission rate is distributed in the southernmost wetland area of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, and the average wetland CH4 emission rates in these areas reached 75.5, 90.2 and 112.8 gC·m−2·a−1 in 2090–2100, respectively.

Figure 4.

Spatial distributions of CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau for three RCPs and three time periods.

3.3. Dynamics in the Spatial Distribution of Future CH4 Emissions from Wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

Differences in the spatial distribution of the annual average CH4 emission rates showed that emissions from most wetlands increased by 0–5.0 gC·m−2·a−1 between 2008 and 2090–2100 (Figure 5). Emissions decreased in only 1.9% of wetlands under the RCP 2.6 scenario and 1.5% of wetlands under the RCP 4.5 scenario. The increases were larger under the RCP 8.5 scenario than the other ones, amounting to 10–32 gC·m−2·a−1 on over 16% of the wetland areas. Under all three RCPs, emissions grew fastest in the southern region, with rates (in gC·m−2·a−1) of 10 under RCP 2.6, 22 under RCP 4.5 and 32 under RCP 8.5. Emissions grew second-fastest in the eastern region, and slowest in the western region.

Figure 5.

Differences in spatial distribution of CH4 emission from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau between 2008 and 2090–2100. Negative differences indicate a decrease from 2008 to 2090–2100.

4. Discussion

The wetland area is about 860 × 104 km2 in the world, but 80% of wetland resources are being lost or degraded due to irrational utilization [38,39], resulting in the wetland ecosystem becoming one of the most threatened ecosystems in the world [40]. China is one of the countries with the most abundant wetland resources, ranking the fourth in the world with 304,849 km2, accounting for 10% of the global wetland area [12]. The Qinghai–Tibet Plateau has the largest wetland area in China [41], accounting for more than 30% of the total wetland area of the country. To make a reasonable estimation for wetland CH4 emission of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau is important for the evaluation of the CH4 budget of China, since CH4 was put on the agenda of COP26 on making further actions to reduce CH4 missions by 2030. Additionally, with the highest altitude, the wetland on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau is much more sensitive to climate change than other areas, which will have great potential impacts on the inter-annual variation of wetland CH4 emissions of China. Although several studies were conducted to evaluate the historical wetland CH4 emissions of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, there are few studies to make prediction on wetland methane emission of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau under future climate conditions. In this study, our results revealed that in the context of future climate change, CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau will increase by 35–267% by the end of the 21st century, assuming the current spatial distribution will not change. The main factors driving this increase appear to be increases in temperature, precipitation and atmospheric CO2 concentration. The temperature on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau has been projected to increase by 2–4 °C by 2050 and 4–7 °C by 2100 [12,42]. Average annual precipitation may increase by 2.5–10 mm/month in the mid-21st century and by >10 mm/month in the late 21st century [12,42]. Similar to our analysis of wetlands on the Plateau, a study of wetlands in China predicted emission increases of 32–90% by 2100 [43], and studies of global wetlands predicted emission increases of 75–100% [44], 50–80% [45]. Consistent with our analysis, other work has identified temperature and precipitation as the main climatic factors affecting wetland CH4 emission in future [15,44]. Increasing temperature has been shown to increase CH4 emissions by promoting CH4 production and oxidation [46]. The largest increase in methane is observed in the tropics and midlatitudes [6]. Rising temperature increases NPP, provides more metabolic substrates for CH4-producing microorganisms, and enhances the activity of methanogens [15]. The optimal temperature for CH4 generation on peatlands is 25 °C, and every increase of 2 °C reduces soil carbon storage by 10–25% and increases CH4 emissions by 10–20% [47].

Rising water levels also increase CH4 emission rate by altering soil aeration and redox potential. Water levels higher than the surface layer are generally believed to create a reductive environment that promotes methanogen survival [48,49]. Conversely, water levels lower than the surface layer create an aerobic soil environment that promotes survival of methane-oxidizing bacteria, reducing CH4 flux.

CO2 levels in the atmosphere are expected to double in the second half of the 21st century [50], which is expected to increase CH4 emissions globally as well as on wetlands [51,52]. Our analysis suggests that the predicted increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration will contribute 10–28% (depending on the RCP) to the increased CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau by 2100. One possible explanation is that an increase in atmospheric CO2 accelerates decomposition of organic matter in the soil and increases plant productivity, in turn increasing the soluble organic carbon content in soil and the emission of CH4 [53,54]. Whatever the explanation, most models suggest that CH4 emissions from wetlands are affected more by the increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration than by climate change [1].

Our findings should be interpreted carefully, in large part because we assumed a constant wetland distribution on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau based on the distribution in 2008 [36]. However, wetland distribution is affected by climate, geomorphology, soil moisture and other factors that will change in the future [16]. One possibility is that the increased CO2 concentration in the future closes plant stomata, reducing water loss, in turn reducing water demand from the soil, which increases soil moisture and thereby the extent of wetlands [50]. Other possibilities are that wetland area increases when rising temperatures melt the permafrost on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, or that wetland area shrinks because of decreasing precipitation and increasing evaporation [19,55]. Nevertheless, we chose to keep the wetland distribution fixed during the present simulations given the substantial uncertainties in modeling wetland distribution and CH4 emission in general [53], and uncertainties in the extent of the wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau [56]. Several other simulations of future CH4 emissions from wetlands have used a similar approach of fixing wetland distribution based on current conditions [1,57,58].

5. Conclusions

Our TRIPLEX-GHG modeling of CH4 emissions from wetlands on the Qinghai–Tibet plateau under 3 RCPs, based on future climate change data from 24 CMIP5 models, suggests that climate change and increasing atmospheric CO2 concentration will substantially alter the temporal and spatial distribution of CH4 emissions from the Plateau’s wetlands. Our modeling suggests that, assuming a constant distribution of wetlands on Qinghai–Tibet Plateau, CH4 emissions will increase by 35–267% by the end of the 21st century. CH4 emission rates are predicted to be higher from southern wetlands than from northern ones, and higher from eastern wetlands than from western ones. Under the scenario of RCP8.5, the wetland CH4 emissions in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau showed a stronger increasing trend than that under scenarios of RCP2.6 and RCP4.5.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Z., H.C. and C.P.; methodology, X.Z., J.W. and J.Z.; formal analysis, X.Z. and J.W.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Z.; writing—review and editing, Q.Z., H.C. and C.P.; visualization, X.Z. and J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition (2019QZKK0304), National Natural Science Foundation of China (42041005, U2243203).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are publicly available from https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19837936.v1 (accessed on 20 April 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. In Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kirschke, S.; Bousquet, P.; Ciais, P.; Saunois, M.; Canadell, J.G.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Bergamaschi, P.; Bergmann, D.; Blake, D.R.; Bruhwiler, L.; et al. Three decades of global methane sources and sinks. Nat. Geosci. 2013, 6, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.P.; Luo, P.; Wang, Y.F.; Wu, N. Advances in the research on methane emissions from wetlands. World Sci.-Technol. Res. Dev. 2007, 29, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Bousquet, P. Methane on the rise-again. Science 2014, 476, 493–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Manning, M.R.; Lowry, D.; Fisher, R.E.; France, J.L.; Michel, S.E.; Miller, J.B.; White, J.W.C.; Vaughn, B.; et al. Rising atmospheric methane: 2007–2014 growth and isotopic shift. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 2016, 30, 1356–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nisbet, E.G.; Manning, M.R.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Fisher, R.E.; Lowry, D.; Michel, S.E.; Myhre, C.L.; Platt, S.M.; Allen, G.; Bousquet, P.; et al. Very Strong Atmospheric Methane Growth in the 4 Years 2014–2017: Implications for the Paris Agreement. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2019, 33, 318–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, S.E.M.; Schaefer, H. Rising methane: A new climate challenge. Science 2019, 364, 932–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, H.; Fletcher, S.E.M.; Veidt, C.; Lassey, K.R.; Brailsford, G.W.; Bromley, T.M.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Michel, S.E.; Miller, J.B.; Levin, I.; et al. A 21st-century shift from fossil-fuel to biogenic methane emissions indicated by 13CH4. Science 2016, 352, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunois, M.; Bousquet, P.; Poulter, B.; Peregon, A.; Ciais, P.; Canadell, J.G.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Etiope, G.; Bastviken, D.; Houweling, S.; et al. Variability and quasi-decadal changes in the methane budget over the period 2000–2012. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2017, 17, 11135–11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thompson, R.L.; Nisbet, E.G.; Pisso, I.; Stohl, A.; Blake, D.; Dlugokencky, E.J.; Helmig, D.; White, J.W.C. Variability in Atmospheric Methane from Fossil Fuel and Microbial Sources Over the Last Three Decades. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 11499–11508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.; Gao, Y.H.; Yao, S.P.; Wu, N.; Wang, Y.F.; Luo, P.; Tian, J.Q. Spatio temporal variation of methane emissions from alpine wetlands in Zoige Plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2008, 28, 3425–3437. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhu, Q.A.; Peng, C.H.; Wu, N.; Wang, Y.F.; Fang, X.Q.; Jiang, H.; Xiang, W.H.; Chang, J.; Deng, X.W.; et al. Methane emissions from rice paddies natural wetlands, lakes in China: Synthesis new estimate. Global Chang. Biol. 2013, 19, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.; Xu-Ri; Tarchen, T.; Dai, D.X.; Wang, Y.S.; Wang, Y.H. Revisiting the role of CH4 emissions from alpine wetlands on the Tibetan Plateau: Evidence from two in situ measurements at 4758 and 4320 m above sea level. J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosci. 2015, 120, 1741–1750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Yamada, K.; Tang, Y.H.; Yoshida, N.; Wada, E. Stable carbon isotopic evidence of methane consumption and production in three alpine ecosystems on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Atmos Environ. 2013, 77, 338–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, F.M.; Boucher, O.; Gedney, N.; Jones, C.D.; Folberth, G.A.; Coppell, R.; Friedlingstein, P.; Collons, W.J.; Chappellaz, J.; Ridley, J.; et al. Possible role of wetlands, permafrost, and methane hydrates in the methane cycle under future climate change: A review. Rev. Geophy. 2010, 48, RG4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.F.; Tian, H.Q. Methane exchange between marshland and the atmosphere over China during 1949–2008. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2012, 26, GB2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.D.; Zhuang, Q.L.; Chen, M.; Sirin, A.; Melillo, J.; Kicklighter, D.; Sokolov, A.; Song, L.L. Rising methane emissions in response to climate change in Northern Eurasia during the 21st century. Environ. Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 045211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, A.A.; Palmer, P.I.; Fraser, A.; Reay, D.S.; Frankenberg, C. Large-scale controls of methanogenesis inferred from methane and gravity spaceborne data. Science 2010, 327, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- van Groenigen, K.J.; Osenberg, C.W.; Hungate, B.A. Increased soil emissions of potent greenhouse gases under increased atmospheric CO2. Nature 2011, 475, 214–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arneth, A.; Sitch, S.; Bondeau, A.; Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Foster, P.; Gedney, N.; de Noblet-Ducoudré, N.; Prentice, I.C.; Sanderson, M.; Thonicke, K. From biota to chemistry and climate: Towards a comprehensive description of trace gas exchange between the biosphere and atmosphere. Biogeosciences 2010, 7, 121–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.H.; Prinn, R.G. Atmospheric modeling of high-and low-frequency methane observations: Importance of interannually varying transport. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 2005, 110, D10303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, M.K.; Marshall, S.; Gregson, K. Global carbon exchange and methane emissions from natural wetlands: Application of a process-based model. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 1996, 101, 14399–14414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, J.; Peng, C.; Chen, H.; Fang, X.; Jiang, H.; Yang, G.; Zhu, D.; Wang, W.; Zhou, X. Modelling methane emissions from natural wetlands by development and application of the TRIPLEX-GHG model. Geosci. Model. Dev. 2014, 7, 981–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, C.S.; Trettin, C.C.; Li, H.; Sun, G. An integrated model of soil, hydrology, and vegetation for carbon dynamics in wetland ecosystems. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2002, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhuang, Q.; Melillo, J.M.; Kicklighter, D.W.; Prinn, R.G.; Mc Guire, A.D.; Steudler, P.A.; Felzer, B.S.; Hu, S. Methane fluxes between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere at northern high latitudes during the past century: A retrospective analysis with a process-based biogeochemistry model. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2004, 18, GB3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, W.J.; Subin, Z.M.; Lawrence, D.M.; Swenson, S.C.; Torn, M.S.; Meng, L.; Mahowald, N.M.; Hess, P. Barriers to predicting changes in global terrestrial methane fluxes: Analyses using CLM4Me, a methane biogeochemistry model integrated in CESM. Biogeosciences 2011, 8, 1925–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, K.; Kong, C.F.; Liu, J.Q.; Wu, Y. Using Methane Dynamic Model to Estimate Methane Emission from Natural Wetlands in China. In Proceedings of the 2010 18th International Conference on Geoinformatics, Beijing, China, 18–20 June 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, D.; Wang, X.D. Recent climatic changes and wetland expansion turned Tibet into a net CH4 source. Clim. Chang. 2017, 144, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.T.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Z.G.; Ma, Z.F.; Liu, J.; Luo, Y.; Xu, J.J.; Wang, G.C.; Zhang, W. Modeling CH4 emissions from natural wetlands on the Tibetan Plateau over the past 60 years: Influence of climate change and wetland loss. Atmosphere 2016, 7, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Foley, J.A.; Prentice, I.C.; Ramankutty, N.; Levis, S.; Pollard, D.; Sitch, S.; Haxeltine, A. An integrated biosphere model of land surface processes, terrestrial carbon balance, and vegetation dynamics. Global Biogeochem. Cy. 1996, 10, 603–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharik, C.J.; Foley, J.A.; Delire, C.; Fisher, V.A.; Coe, M.T.; Lenters, J.D.; Young-Molling, C.; Ramankutty, N.; Norman, J.M.; Gower, S.T. Testing the performance of a dynamic global ecosystem model: Water balance, carbon balance, and vegetation structure. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2000, 14, 795–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.A.; Peng, C.H.; Chen, H.; Fang, X.Q.; Liu, J.X.; Jiang, H.; Yang, Y.Z.; Yang, G. Estimating global natural wetland methane emissions using process modelling: Spatio-temporal patterns and contributions to atmospheric methane fluctuations. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2015, 24, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Q.A.; Yang, B.; Wang, J.Y.; Chen, H.; Peng, C.H. Evaluating patterns of wetland methane emissions in Qinghai-Tibet plateau based on process model. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2020, 40, 3060–3071. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.A.; Peng, C.; Liu, J.; Jiang, H.; Fang, X.; Chen, H.; Niu, Z.; Gong, P.; Lin, G.; Wang, M.; et al. Climate-driven increase of natural wetland methane emissions offset by human-induced wetland reduction in China over the past three decades. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 38020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, K.E.; Stouffer, R.J.; Meehl, G.A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2011, 93, 485–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Niu, Z.G.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, X.W.; Yao, W.B.; Zhou, D.M.; Zhao, K.Y.; Zhao, H.; Li, N.N.; Huangm, H.B.; Li, C.C.; et al. Mapping wetland changes in China between 1978 and 2008. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 57, 2813–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hutchinson, M.F.; Gessler, P.E. Splines: More than just a smooth interpolator. Geoderma 1994, 62, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.Y. Development and prospect of wetland science in China. Adv. Earth Sci. 2000, 15, 666–672. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.G.; Liu, J.S.; Li, B. The actuality, problems and sustainable utilization countermeasures of wetland resources in China. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2006, 20, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lemly, A.D.; Kingsford, R.T.; Thompson, J.R. Irrigated agriculture and wildlife conservation: Conflict on a global scale. Environ. Manag. 2000, 25, 485–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.Y. Wetlands of China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Ding, Y.H.; Li, D.L. Climatic Change over Qinghai and Xizang in 21st Century. Plateau Meteorol. 2003, 22, 451–457. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.G.; Zhu, Q.A.; Shen, Y.; Yang, Y.Z.; Luo, Y.P.; Peng, C.H. Spatiotemporal variations of natural wetland CH4 emissions over China under future climate change. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 26, 3467–3474. [Google Scholar]

- Gedney, N.; Cox, P.M.; Huntingford, C. Climate feedback from wetland methane emissions. Environ. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L20503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koffi, E.N.; Bergamaschi, P.; Alkama, R.; Cescatti, A. An observation-constrained assessment of the climate sensitivity and future trajectories of wetland methane emissions. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay4444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharyya, P.; Roy, K.S.; Neogi, S.; Dash, P.K.; Nayak, A.K.; Mohanth, S.; Baig, M.J.; Sarkar, R.K.; Rao, K.S. Impact of elevated CO2 and temperature on soil C and N dynamics in relation to CH4 and N2O emissions from tropical flooded rice. Sci. Total Enciron. 2013, 461, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, W.Q.; Wu, Z.L.; Wang, Z.L. Control factors and critical condition between carbon sinking and sourcing of wetland ecosystem. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2011, 20, 1359–1366. [Google Scholar]

- van Huissteden, J.; Maximov, T.C.; Dolman, A.J. High methane flux from an arctic floodplain (Indigirka lowlands, eastern Siberia). J. Geophys. Res.-Biogeosci. 2009, 144, G02018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dijkstra, F.A.; Morgan, J.A.; Follett, R.F.; Lecain, D.R. Climate change reduces the net sink of CH4 and N2O in a semiarid grassland. Global Chang. Biol. 2013, 19, 1816–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, L.; Deng, A.; Bian, X.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, W. Responses of dissolved organic carbon and dissolved nitrogen in surface water and soil to CO2 enrichment in paddy field. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2011, 140, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton, J.R.; Wania, R.; Hodson, E.L.; Hodson, E.L.; Poulter, B.; Ringeval, B.; Spahni, R.; Bohn, T.; Avis, C.A.; Beerling, D.J.; et al. Present state of global wetland extent and wentland methane modeling: Conclusions from a model inter-comparison project (WETCHIMP). Biogeosciences 2013, 10, 753–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shindell, D.T.; Walter, B.P.; Faluvegi, G. Impacts of climate change on methane emissions from wetlands. Environ. Res. Lett. 2004, 31, L21202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.A.; Drake, B.G.; Erickson, J.E.; Megonigal, J.P. An oxygen-mediated positive feedbake between elevated carbon dioxide and soil organic matter decomposition in a simulated anaerobic wetland. Global Chang. Biol. 2007, 13, 2036–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenner, N.; Freeman, C.; Lock, M.A.; Harmens, H.; Reynolds, B.; Sparks, T. Interactions between elevated CO2 and warming could amplify DOC exports from peatland catchments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 3146–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valk, A.G.V.D. Water-level fluctuations in North American prairie wetlands. Hydrobiologia 2005, 539, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, M.; Chen, H.; Peng, C. High uncertainties detected in the wetlands distribution of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau based on multisource data. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 16, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseev, A.V.; Mokhov, I.I.; Arzhanov, M.M.; Demchenko, P.F.; Denisov, S.N. Interaction of the methane cycle and processes in wetland ecosystems in a climate model of intermediate complexity. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2008, 44, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volodin, E.M. Methane cycle in the INM RAS climate model. Izv. Atmos. Ocean. Phys. 2008, 44, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).