Abstract

Since the introduction of the NMDA receptor antagonist (S)-ketamine for depression therapy, it has become evident that the glutamatergic hypothesis of depression, proposed over 20 years ago, was justified and based on solid foundations. A significant breakthrough with this drug is its ability to produce a rapid and relatively long-lasting antidepressant effect in patients who are resistant to traditional depression treatments, both pharmacological and non-pharmacological. However, alongside its beneficial effects, (S)-ketamine can cause several side effects that make it a less safe option. As a result, strategies are being explored to mitigate the risks associated with its use. These strategies include leveraging the shared mechanism of action between ketamine and various modulators of the glutamatergic system. Preclinical studies have shown that low doses of mGlu2 and mGlu5 receptor antagonists can enhance the therapeutic effects of ketamine or its enantiomers without producing the typical side effects associated with ketamine. This review discusses the research on this synergistic effect, the underlying mechanisms, and the role of mGlu2 and mGlu5 receptors in the antidepressant action of ketamine.

Keywords:

antidepressant; depression; ketamine; LY341495; M-5MPEP; mGlu2 receptor; mGlu5 receptor; RAAD; TRD 1. Introduction

(S)-ketamine is currently the only registered rapid-acting antidepressant drug (RAAD) that has proven effective in treating treatment-resistant depression (TRD) through both intravenous and intranasal administration [1,2,3,4]. However, the introduction of (S)-ketamine has not resolved ongoing research concerns regarding its mechanism of action, potential adverse effects, and its effectiveness in various mental health disorders [5,6]. (S)-ketamine is one of the two enantiomers of ketamine, which has been used in medicine for several decades as an anesthetic [7]. Ketamine is a non-selective drug that interacts with various molecular and cellular mechanisms, resulting in a wide range of effects, both beneficial and adverse. Notable adverse effects can include depersonalization, which is related to the dissociative properties of the substance, agitation, confusion and even psychotic effects. Additionally, (S)-ketamine carries a potential for abuse [6].

This raises several important questions: What specific mechanisms of action are responsible for ketamine’s antidepressant effects? Is it possible to separate the desired effects from the undesirable ones? Can we minimize adverse effects while maintaining therapeutic effectiveness? How close are we to finding an alternative RAAD that is equally effective but has a lower potential for abuse? To address these questions, further exploration into the mechanisms of action of ketamine is necessary, utilizing both animal models and human studies.

A comprehensive discussion of the various mechanisms of action of ketamine is beyond the scope of this review. However, there are several important points to highlight. First, the antidepressant effect of ketamine follows a U-shaped curve, indicating that its effects are not observed at either low doses or high (anesthetic) doses [8]. Second, ketamine’s direct mechanism of action is primarily related to its modulation of glutamatergic transmission, specifically targeting the ionotropic glutamate receptor, NMDA [7]. Ketamine acts as a channel blocker at the phencyclidine (PCP) binding site of this receptor, suggesting that its action may be inhibitory. Interestingly, this inhibition may have the opposite effect; blocking NMDA channels on GABAergic interneurons in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) results in the disinhibition of glutamatergic pyramidal cells, leading to increased neuronal activity [9]. This heightened activity of pyramidal neurons in the PFC, which occurs following subanesthetic doses of ketamine, appears to initiate a series of neuroplastic changes in this area [10,11]. These changes may be modulated by factors that regulate the translation process necessary for producing new proteins, which are essential for forming new synaptic connections. mTOR kinase has been proposed as a key regulator of protein translation in this context [12]. Another proposed factor regulating the translation process, which plays a crucial role in ketamine’s antidepressant action, is eEF2 kinase. Research demonstrated its key role in the hippocampus, forming the basis for the theory of rapid homeostatic plasticity, highlighting the specific function of BDNF/TrkB signaling [13].

Interestingly, there are strong indications that ketamine’s mechanism of action is independent of direct NMDA receptor blockade [14,15]. This principle also applies to the antidepressant-active ketamine metabolite, (2R,6R)-HNK [15]. This finding offers hope for achieving therapeutic effects without the adverse effects commonly associated with NMDA receptor blockade, particularly since other NMDA receptor channel blockers do not replicate the ketamine-like antidepressant effects in humans [16].

On the other hand, activation of NMDA receptors, particularly through the GluN2A subunit, appears to be necessary for inducing the rapid antidepressant effects of not only ketamine but also other potential RAADs [8]. Thus, enhancing NMDAR signaling to promote NMDAR-dependent long-term potentiation (LTP)-like synaptic potentiation has been proposed as an effective antidepressant strategy [8]. Furthermore, studies indicate that there are additional targets, unrelated to glutamatergic receptor regulation, that also contribute to ketamine’s antidepressant response. These targets primarily include opioid receptors, sigma receptors, the TrkB receptor, and others [17,18].

While (S)-ketamine is the only RAAD registered for the treatment of TRD, there is also significant therapeutic potential in its second enantiomer, (R)-ketamine, as well as in (RS)-ketamine and some of its metabolites, including (2R,6R)-HNK [15,19]. Additionally, substances that modulate glutamatergic transmission through mGlu receptors show promise as RAADs; however, current evidence is primarily based on animal studies. These substances primarily include functional antagonists of the mGlu5 and mGlu2/3 receptors [20,21,22].

Notably, many cellular and molecular mechanisms responsible for the rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine have also been observed with mGlu5 and mGlu2/3 antagonists. This suggests a convergence in the mechanisms of action for these substances, despite their different receptor targets. Key mechanisms include: activation of mTOR, which is crucial for enhancing neuroplasticity and contributing to the antidepressant effect [23,24,25,26], the central role of the AMPA receptor [27,28,29,30], downstream activation of the NMDA receptor [8] (Zanos et al., 2023), and dependence on BDNF/TrkB signaling in their action [26,31]. Furthermore, shared mechanisms involving serotonergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission have been proposed as contributing to the antidepressant actions of both ketamine and mGlu2/3 receptor antagonists [24,27,28,30,32]. To our knowledge, the only significant mechanism of rapid ketamine’s antidepressant action not demonstrated for mGlu2/3 antagonists is its dependence on the regulation of eEF2 kinase [13].

In addition, mGlu2/3 and mGlu5 receptor antagonists have been shown to replicate the behavioral effects of ketamine in various tests and animal models of depression. Notably, these antagonists exhibited effects that lasted 24 h or longer after a single or short-term administration. This prolonged activity is characteristic of RAADs and differs from traditional antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) [21,25,29,30,31,33]. Moreover, mGlu2/3 receptor antagonists (like LY341495, MGS0039, and TP0178894) and mGlu5 receptor negative allosteric modulators (NAMs), such as M-5MPEP, demonstrated antidepressant effects in animal models of depression, including the chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS) and social defeat stress (SDS). These compounds induced a rapid reversal of modeled depression symptoms following a single or short-term administration, a trait associated with RAADs, but not with classical antidepressants [34,35,36,37,38]. Importantly, from a practical standpoint, mGlu2/3 antagonists have shown a favorable safety profile, as they do not produce neurotoxic, motor, cognitive, or abuse-related effects similar to those of ketamine [39].

Given the significant overlap in the mechanisms of action between ketamine and mGlu2/3 and mGlu5 receptor antagonists observed in animal models, an important question arises: could these compounds act synergistically? If so, could a subtherapeutic dose of ketamine be enhanced by the co-administration of an mGlu2 antagonist or an mGlu5 antagonist? This approach may help reduce the adverse effects associated with ketamine. Recent studies have provided several insights on this topic. They explore not only the potential to enhance the antidepressant effects of ketamine through mGlu2/3 and mGlu5 antagonists but also the effects of its enantiomers, (S)-ketamine and (R)-ketamine. Additionally, research indicates that mGlu2 and mGlu5 receptors play a role in the mechanisms through which ketamine, its enantiomers, and its active metabolites exert their effects.

2. The Involvement of the mGlu2 Receptor in the Effects of Ketamine

The initial data regarding the functional relationship between mGlu2/3 receptor activation and ketamine’s effects in the brain were presented in studies by Lorrain et al. [40,41]. These studies demonstrated that mGlu2/3 receptor agonists could reverse certain behavioral effects induced by ketamine, such as hyperlocomotion, and block the release of glutamate, norepinephrine, and dopamine triggered by ketamine, particularly in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). This suggests that mGlu2/3 receptor agonists may have potential for treating symptoms of psychosis through a mechanism that reduces ketamine (or PCP)-induced glutamatergic neurotransmission in the mPFC. Notably, these studies indicated that the relationship between ketamine and mGlu2/3 agonists is mainly one of negative feedback. The mechanism underlying this effect is likely related to the synaptic distribution and functional characteristics of the mGlu2/3 receptor. mGlu2 receptors are primarily located presynaptically in the preterminal regions of axons and function as inhibitory autoreceptors during periods of high excitation. They are abundantly expressed in limbic areas, including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala [42,43,44]. Consequently, mGlu2 receptor agonists inhibit glutamate release, which may result in reduced ketamine-enhanced glutamate levels, thereby decreasing ketamine-induced neurochemical and behavioral effects. Subsequent studies have confirmed this functional relationship between mGlu2 receptor activation through agonists or positive allosteric modulators (PAM) and ketamine. For instance, it was found that pretreatment with the mGlu2/3 receptor agonist LY379268 significantly reduced ketamine-induced blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signals in the rat brain [45]. Similar findings were confirmed in humans, where mGlu2/3 receptor agonists (LY2140023 and LY2979165) also reduced the ketamine-evoked BOLD phMRI signal [46]. Additionally, another indicator of neuronal activation, the cortical quantitative EEG (qEEG) gamma power evoked by ketamine, was found to decrease following pretreatment with the mGlu2/3 agonist LY379268 [47,48,49] or PAM TASP0433864 [50].

A stronger relationship has been observed between the activity of mGlu2 receptor ligands and ketamine concerning its antidepressant effects. The initial evidence for this association was provided by a comparative study conducted by Witkin et al. [30], which highlighted several physiological, pharmacological, and behavioral similarities between ketamine and the mGlu2 receptor antagonist LY3020371. Notably, the study demonstrated that in the forced swim test (FST) in rats, the mGlu2/3 receptor agonist LY354740 completely blocked the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine [30]. Further investigation by Zanos and colleagues confirmed the mGlu2/3 receptor-dependent activity of the antidepressant doses of ketamine in mice. They utilized a hyperthermia assay induced by the mGlu2/3 receptor agonist LY379268 for this purpose [51]. This effect was replicated by (2R,6R)-HNK, a ketamine metabolite with antidepressant properties, which functions through a mechanism that does not depend on NMDA receptor inhibition. Conversely, NMDA receptor antagonists, which do not produce antidepressant effects—such as channel blockers at the PCP-binding site like MK-801 or Ro 25-6981, a GluN2B-specific NMDA receptor antagonist—did not induce the same effects [51]. These data suggest that the mechanism preventing LY379268-induced hyperthermia by ketamine is unlikely to involve NMDA receptor inhibition. Additionally, experiments using mice that genetically lack the Grm3 or Grm2 gene revealed that the effect is associated with the mGlu2 receptor but not the mGlu3 receptor [51]. Therefore, it has been established that the antidepressant action of ketamine and its active metabolite relies on the activation of the mGlu2 receptor, rather than directly blocking the NMDA receptor. Furthermore, an enhancement of high-frequency (gamma) qEEG oscillations—an in vivo marker of neuronal excitation—was observed following the administration of LY341495 and (2R,6R)-HNK [51]. These findings imply that both mGlu2 receptor antagonists and (2R,6R)-HNK act in a manner dependent on the mGlu2 receptor to enhance high-frequency neuronal activity, which may be related to their antidepressant effects. Another study indicated that (2R,6R)-HNK does not directly bind to the mGlu2 receptor; therefore, the relationship between ketamine and the mGlu2 receptor appears to involve an indirect mechanism [52].

3. Synergistic Effects of Ketamine and mGlu2/3 Receptor Antagonists

Due to the high similarity in the mechanisms of rapid antidepressant action between ketamine and the mGlu2/3 antagonist, Podkowa et al. [53] proposed, for the first time, combining subthreshold doses of both compounds. This approach aimed to investigate their potential synergistic effects while minimizing the side effects commonly associated with ketamine. In their study using the FST in rats, the authors confirmed that the mGlu2/3 antagonist LY341495 enhanced the effects of a subthreshold dose of ketamine both 40 min and 24 h after administration. The results provided the first evidence that combining these subthreshold doses of ketamine and LY341495 produces synergistic antidepressant-like effects without inducing the typical adverse effects associated with higher, antidepressant doses of ketamine [53]. Similarly, Zanos et al. [51] conducted independent research in mice, examining how the physiological actions of ketamine or its active metabolite (2R,6R)-HNK relate to mGlu2 receptor signaling. They aimed to determine whether these effects could be reflected in animal models predictive of antidepressant activity. To investigate the synergistic effects of mGlu2/3 receptor antagonists when combined with ketamine, subeffective doses of LY341495 and ketamine were co-administered and assessed using the FST in mice. The study found that this drug combination, as well as the combination of LY341495 and (2R,6R)-HNK, produced significant antidepressant-like effects both 1 h and 24 h after administration [51]. Furthermore, the subeffective doses of LY341495 and (2R,6R)-HNK resulted in a synergistic enhancement of cortical qEEG gamma power, a marker of target engagement associated with antidepressant efficacy [51].

In line with the hypothesis that a convergent mechanism of action exists between mGlu2/3 receptor inhibition and the effects of ketamine, subsequent studies were conducted using a model of depression based on unpredictable chronic mild stress (CUMS) in mice. The study demonstrated a synergistic effect when ketamine and LY341495 were administered together in subthreshold doses over three consecutive days. This combination effectively eliminated the stress-induced effects of apathy (measured by self-grooming time), anhedonia (assessed through sucrose consumption preference), and helplessness (evaluated in the tail suspension test, TST) [38]. Importantly, the coadministration of low doses of ketamine and LY341495 did not cause the hyperactivity typically associated with NMDA channel blockers. Furthermore, it did not impair short-term memory in the novel object recognition (NOR) test or disrupt motor coordination in the rotarod test, indicating a favorable safety profile for this treatment [38].

A recent study by Rafało-Ulińska et al. [54] has provided new insights into the effects of the combined administration of an mGlu2/3 antagonist along with each of the ketamine enantiomers, (R)-ketamine and (S)-ketamine, analyzed separately. The study’s findings indicated that in the TST, the effects of both ketamine enantiomers were enhanced when administered with LY341495, an mGlu2/3 antagonist, 60 min after administration. These enhanced effects were found to depend on the activation of the AMPA receptor, rather than the TrkB receptor. Furthermore, in the CUMS model of depression, which enables to assess the effects of fast-acting antidepressants, it was observed that 24 h after treatment, only (R)-ketamine showed a significantly enhanced effect when combined with the mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist. This enhancement was evident across all tests measuring anhedonia, apathy, and helplessness. In contrast, no enhancement was seen when (S)-ketamine was combined with LY341495 in any of the tests used [54]. This suggests that (R)-ketamine is primarily responsible for the enhanced antidepressant effects observed with the racemic mixture of ketamine, which contains equal parts of both enantiomers. Notably, the antidepressant effects of the combination of (R)-ketamine and LY341495 persisted for 3 to 4 days following administration [54]. The significance of this study lies in its demonstration of the differing mechanisms through which ketamine enantiomers act in relation to the mGlu2 receptor. Additionally, it highlights the potential for safe and effective therapy; (R)-ketamine tends to produce fewer adverse effects, and the co-administration of an mGlu2 antagonist may allow for a further reduction in the dosage of (R)-ketamine required.

4. Possible Mechanism for the Enhancement of Ketamine’s Antidepressant Effects Through Antagonism of the mGlu2 Receptor

The question arises: What mechanisms enhance the antidepressant effects of ketamine (or (R)-ketamine) when combined with the mGlu2 receptor antagonist, and which brain areas might be involved in these processes? The first study showing that the mGlu2 receptor antagonist potentiates the effects of ketamine in the FST in rats suggested a possible mechanism for this interaction [53]. It was found that this drug combination caused a rapid increase (40 min post-administration) in mTOR phosphorylation in both the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex (PFC). This suggests that mTOR kinase-dependent protein translation may play a role in this enhancement. However, only in the hippocampus was there a significant increase in the PSD-95 protein level, comparable to the antidepressant dose of ketamine, 24 h after administering the tested compounds. PSD-95 is a crucial scaffolding protein located at the postsynaptic density of excitatory synapses, essential for synaptic transmission and plasticity [55]. It has also been implicated in the rapid antidepressant effects of ketamine [12]. Therefore, it seems likely that increased neuroplasticity in the hippocampus contributes to the antidepressant-like activity of the combination of ketamine and LY341495 [53]. A subsequent behavioral study by the same research group demonstrated that an AMPA receptor antagonist completely blocked the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine administered alongside LY341495 in the FST in rats. Additionally, a TrkB receptor antagonist, ANA-12, inhibited this effect at one of three studied time points (3 h post-administration) [56]. In a depression model using chronic unpredictable mild stress (CUMS), the prolonged antidepressant-like effect of LY341495 co-administered with (R)-ketamine was found to rely on the activation of either AMPA or TrkB receptors. This treatment also restored the stress-reduced BDNF levels in the hippocampus [54]. Collectively, these findings indicate that the induction of neuroplastic processes involving AMPA/mTOR/BDNF/TrkB signaling is likely a key mechanism behind the synergistic antidepressant effect of the mGlu2 receptor antagonist in conjunction with ketamine and its active metabolites or enantiomers. This conclusion is further supported by studies showing that the neuroplastic effects of LY341495, including dendritic outgrowth and increased spine density in rat hippocampal neurons, required activation of AMPA receptor-mTOR signaling. Additionally, LY341495-induced BDNF expression was inhibited by pretreatment with AMPA and mTORC1 antagonists (NBQX and rapamycin, respectively) [57].

Studies by Zanos and colleagues on mice have significantly advanced our understanding of the synergistic effects of ketamine and the mGlu2 antagonist [51]. The authors demonstrated that combining subeffective doses of LY341495 and (2R,6R)-HNK resulted in increased gamma qEEG oscillations, which are markers of neuronal excitation in vivo [51]. Recent studies have indicated that the antidepressant action of (2R,6R)-HNK in the CA1 region of the hippocampus is associated with the regulation of presynaptic rapid potentiation. This process stimulates priming mechanisms that promote the persistent formation of NMDA-activation-dependent LTP and enhance synaptic plasticity [58]. Of note, the induction of synaptic potentiation by (2R,6R)-HNK does not require NMDA receptor activity; however, NMDA receptor activity is essential for maintaining synaptic priming [58]. Thus, it is possible that presynaptically located mGlu2 receptors, which are significant in the antidepressant action of ketamine in an NMDA-independent manner, may also play a role in the induction of (2R,6R)-HNK-induced synaptic potentiation, that also occurs presynaptically and is independent of NMDA receptor activity.

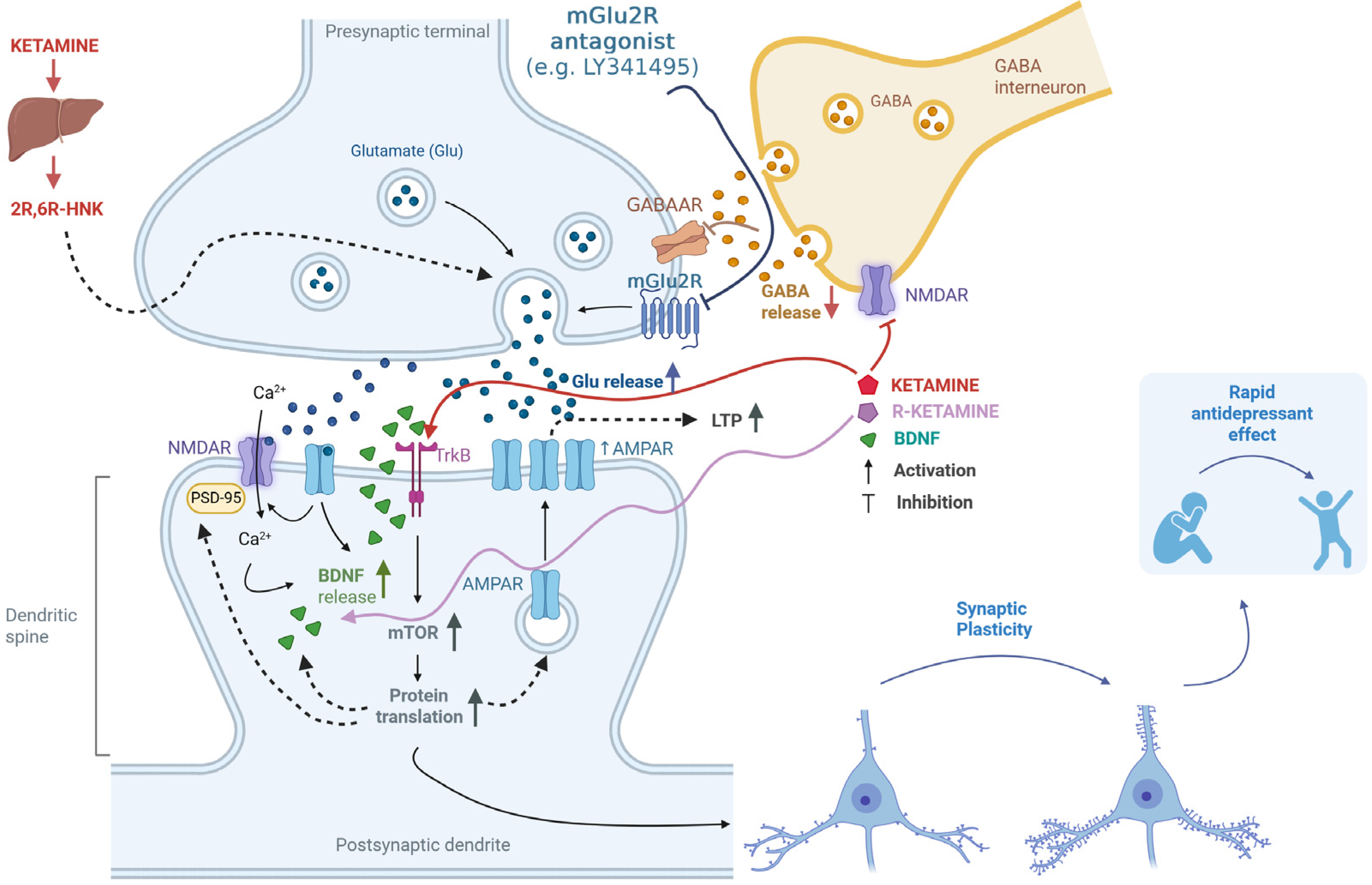

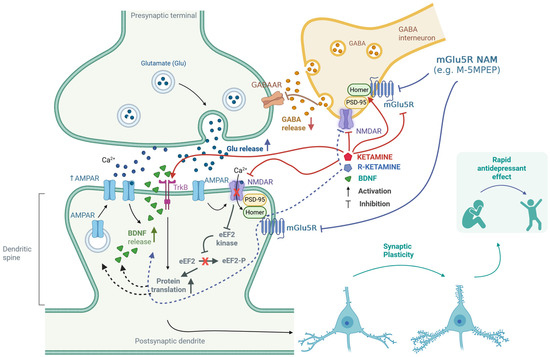

Additionally, using electrophysiological techniques, it was found that co-administering LY341495 with (R)-ketamine prevented changes in glutamatergic transmission and synaptic plasticity induced by CUMS in the mouse PFC. Specifically, the amplitude of field potentials, LTP, and paired-pulse responses—indicators of short-term synaptic plasticity—were affected [59]. There is a proposal to enhance NMDA receptor-dependent LTP-like synaptic potentiation as an effective antidepressant strategy [8]. The synergistic action of LY341495 and (R)-ketamine aligns with this strategy, especially since previous research has shown that blocking mGlu2/3 receptors increases LTP [60]. The proposed mechanisms of action of the mGlu2 antagonist in combination with ketamine or its enantiomers or an active metabolite are comprehensively shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Putative mechanisms for the enhancement of ketamine’s antidepressant effects through antagonism of the mGlu2 receptor. Ketamine works by inhibiting NMDA receptors located on GABAergic interneurons [9]. This inhibition reduces GABA release, leading to the disinhibition of glutamatergic neurons [9]. Additionally, mGlu2 receptors (mGlu2R) are located on glutamatergic neurons and act as autoreceptors [42,43,44]. When mGlu2R antagonists (e.g., LY341495) block these receptors, it results in increased glutamate release and a consequent enhancement of the ketamine effect [30,38,51,53]. One of ketamine’s metabolites, (2R,6R)-HNK, also plays a role in regulating glutamate release through a presynaptic mechanism, further intensifying its effects [15,33,58]. The released glutamate stimulates AMPA receptors, and upon membrane depolarization, NMDA receptors are activated. This activation allows calcium ions to enter the cell, initiating intracellular signaling cascades and promoting the release of BDNF. BDNF then activates TrkB receptors and initiates various intracellular pathways, including the activation of the mTOR kinase pathway [12,53,54]. This leads to increased protein translation and the production of essential proteins for forming new synapses, such as AMPA receptor subunits and PSD-95 protein, as well as BDNF [10,11,12,13,53]. Additionally, ketamine can directly bind to the TrkB receptor [17]. These processes enhance synaptic plasticity, which is fundamental to the rapid antidepressant effect [10,11,12,13,54,59]. Created in BioRender. Pałucha-Poniewiera, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/1owyasp (accessed on 17 November 2025).

5. The Involvement of the mGlu5 Receptor in the Antidepressant Action of Ketamine

The mGlu5 receptor plays an important role in the mechanism by which ketamine exerts its antidepressant effects. Human studies support this idea, as they demonstrate a decrease in mGlu5 receptor availability following intravenous administration of ketamine. For example, a significant reduction in the binding of the selective radioligand [11C]ABP688 to the mGlu5 receptor was observed in several regions of the human brain, including the medial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and hippocampus, after ketamine infusion. This finding was made using high-affinity positron emission tomography (PET) [61]. Another PET study confirmed the decrease in mGlu5 receptor availability in patients receiving intravenous ketamine. This effect lasted for up to 24 h after administration and was correlated with ketamine’s antidepressant effects [62]. In animal studies using rodent models of depression, such as prenatal stress in rats and CUMS in mice, it was found that stress-induced overexpression of the mGlu5 receptor was reversed by an antidepressant dose of ketamine [63] or (R)-ketamine [64]. Additionally, knocking down mGlu5 receptors led to decreased depression-like behaviors [63], indicating the receptor’s involvement in the therapeutic effects of RAADs. The hippocampus has also been identified as a potential brain region involved in these effects [63,64]. Possible mechanisms explaining the reduction in mGlu5 receptor availability following ketamine administration, or its enantiomers, include either the internalization of the mGlu5 receptor induced by ketamine or conformational modifications within the mGlu5 receptor that affect its expression on the cell surface. These mechanisms will be analyzed in detail below [61,65].

Based on these data, it can be concluded that the mechanism of action of ketamine, or its enantiomers, may involve a reduction in mGlu5 receptor activity. This finding aligns with well-documented evidence regarding the potential antidepressant effects of mGlu5 receptor antagonists and NAMs [20,66,67,68]. Supporting this hypothesis, studies using behavioral methods have demonstrated the mGlu5 receptor-dependent mechanism of ketamine’s action. For example, in the FST in rats, the activation of the mGlu5 receptor through the positive allosteric modulator CDPPB was found to inhibit the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine [69]. Conversely, the beneficial effects of ketamine appear to require reduced mGlu5 receptor activity [69]. Thus, the relationship between NMDA and mGlu5 receptors seems to be one of negative feedback. This type of interaction has been observed in other in vivo studies. For instance, research on the anesthetic properties of ketamine has shown that mGlu5 receptor agonists, such as DHPG and CHPG, reduce ketamine-induced anesthesia in mice. In contrast, an mGlu5 receptor antagonist, MPEP, enhances this effect [70]. Similarly, studies investigating the psychotic-like properties of ketamine in mice indicated that ketamine-induced schizophrenia-like behaviors could be reversed by mGlu5 receptor agonists [71].

6. Synergistic Effects of Ketamine and mGlu5 Receptor Antagonists and NAMs

As stated above, research indicates that reducing mGlu5 receptor activity is essential for the antidepressant effects of ketamine and its enantiomers. Consequently, a natural area of investigation has been to determine whether simultaneous blocking of the mGlu5 receptor—using selective antagonists or negative allosteric modulators (NAMs)—could enhance the antidepressant effects of ketamine. Several studies utilizing screening tests and animal models of depression have shown that administering mGlu5 receptor NAMs at subthreshold doses can actually amplify the antidepressant effects of ketamine. For example, combining the mGlu5 receptor NAM MTEP with ketamine resulted in significant synergistic antidepressant effects in the FST in rats [69]. Similar findings were reported in the TST in mice, where each enantiomer of ketamine was individually analyzed. The study revealed that the partial NAM of the mGlu5 receptor, M-5MPEP, administered at a subthreshold dose, enhanced the antidepressant effect of (R)-ketamine but not (S)-ketamine [21]. This specific effect was further confirmed using the CUMS model of depression in mice. The combination of subthreshold doses of (R)-ketamine and M-5MPEP effectively reduced symptoms of apathy and anhedonia induced by CUMS. This synergistic effect was related to changes in the levels of eEF2 and TrkB but not mTOR, in the hippocampus [64].

The significance of these recent studies lies not only in identifying (R)-ketamine as the enantiomer specifically associated with the potentiating effects of mGlu5 NAMs but also in utilizing a partial mGlu5 receptor NAM, M-5MPEP [72]. This partial NAM appears to be both effective and safe compared to previously used full mGlu5 NAMs like MPEP and MTEP. While full mGlu5 receptor NAMs have demonstrated significant antidepressant potential in animal studies, their progression to subsequent research stages has been impeded. This is primarily due to severe side effects, such as psychotomimetic effects and cognitive dysfunction [73,74]. Only studies on partial mGlu5 receptor NAMs, which induce less than 100% of the effects achieved by full NAMs at maximum concentrations, have raised hopes for their therapeutic applications. These compounds have demonstrated desirable effects, including anxiolytic, antidepressant, and anticocaine abuse properties, at doses that do not cause psychotomimetic side effects [72,75]. The broader therapeutic window of partial mGlu5 NAMs, combined with the similarity of some of their antidepressant mechanisms to RAADs, suggests that these compounds could improve the safety and efficacy of RAADs.

In summary, augmenting subthreshold doses of (R)-ketamine through the co-administration of a partial mGlu5 receptor NAM may offer an effective and safe treatment option for depression. However, this topic warrants further investigation, particularly in depressed patients. Studies demonstrating the antidepressant-like effects of administering subthreshold doses of an antagonist or NAM of mGlu2 or mGlu5 receptors alongside subthreshold doses of ketamine, its enantiomers, or a metabolite are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antidepressant-like effects of co-administering low, subthreshold doses of ketamine, its enantiomers, or metabolite with low, subthreshold doses of an mGlu2 or mGlu5 receptor antagonist or NAM in animal models of depression and screening tests.

7. Putative Mechanism of Potentiation of Ketamine’s Antidepressant Effect by mGlu5 Receptor Antagonism

What mechanism accounts for the strong functional association between ketamine and mGlu5 receptor ligands? To answer this question, it may help to consider some relevant and well-documented data. First, mGlu5 receptors interact with NMDA receptors through molecular mechanisms that arise from their physical and functional connection. Electrophysiological, biochemical, and molecular studies have demonstrated that the activation of the NMDA receptor enhances the function of the mGlu5 receptor. Conversely, activation of the mGlu5 receptor leads to an increase in NMDA receptor currents [76,77,78,79,80]. This functional interdependence is the result of an indirect physical association between mGlu5 receptors and NMDA receptors, which is mediated by Shank and Homer proteins. The Shank protein, part of the NMDA receptor-associated PSD-95 complex, binds to scaffolding Homer proteins, which are directly connected to the C-terminal tail of the mGlu5 receptor [81,82].

Notably, Homer proteins play a crucial role in regulating the interaction between mGlu5 and NMDA receptors. The long form of Homer1, known as Homer1b, facilitates a stable functional connection between the mGlu5 receptor and the NMDA receptor via the Shank protein. In contrast, the short form, Homer1a, disrupts this interaction [83,84]. Homer1a competes with Homer1b for binding to the mGlu5 receptor, which results in the uncoupling of mGlu5 from the Shank proteins that link it to the NMDA receptor [85]. Interestingly, ketamine can interfere with the regulatory mechanisms of Homer proteins, thereby affecting the mGlu5-NMDA receptor interaction. For example, ketamine has been shown to induce the expression of Homer1a in the cortical regions of the rat brain while simultaneously reducing the expression of Homer1b and PSD-95 in both cortical and striatal regions [86]. Furthermore, the antidepressant effects of ketamine are diminished when Homer1a is knocked down using siRNA in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) [87]. This suggests that ketamine increases the ratio of Homer1a to Homer1b, leading to the disassembly of the indirect connection between mGlu5 and NMDA receptors involving Shank and Homer proteins [88]. On the other hand, disconnection of the mGlu5 receptor from Homer1b has been shown to increase the lateral mobility of the mGlu5 receptor and promote its direct interaction and co-clustering with the NMDA receptor in hippocampal neurons [89].

Recently, Elmeseiny and Müller [90] proposed an intriguing and comprehensive mechanism for ketamine’s antidepressant action, linking NMDA inhibition with mGlu5 receptor modulation. This concept is based on the important role of Homer proteins in regulating the functional connection between mGlu5 and NMDA receptors. The authors suggest that ketamine uncouples the mGlu5 receptor from the Shank protein complex by inducing Homer1a. With the increased mobility of the mGlu5 receptor and its lateral diffusion into the synapse, it can directly associate with the NMDA receptor. According to the authors, this complex could integrate molecular information and facilitate the prolonged antidepressant effects observed even after the drug has been cleared from the brain [90].

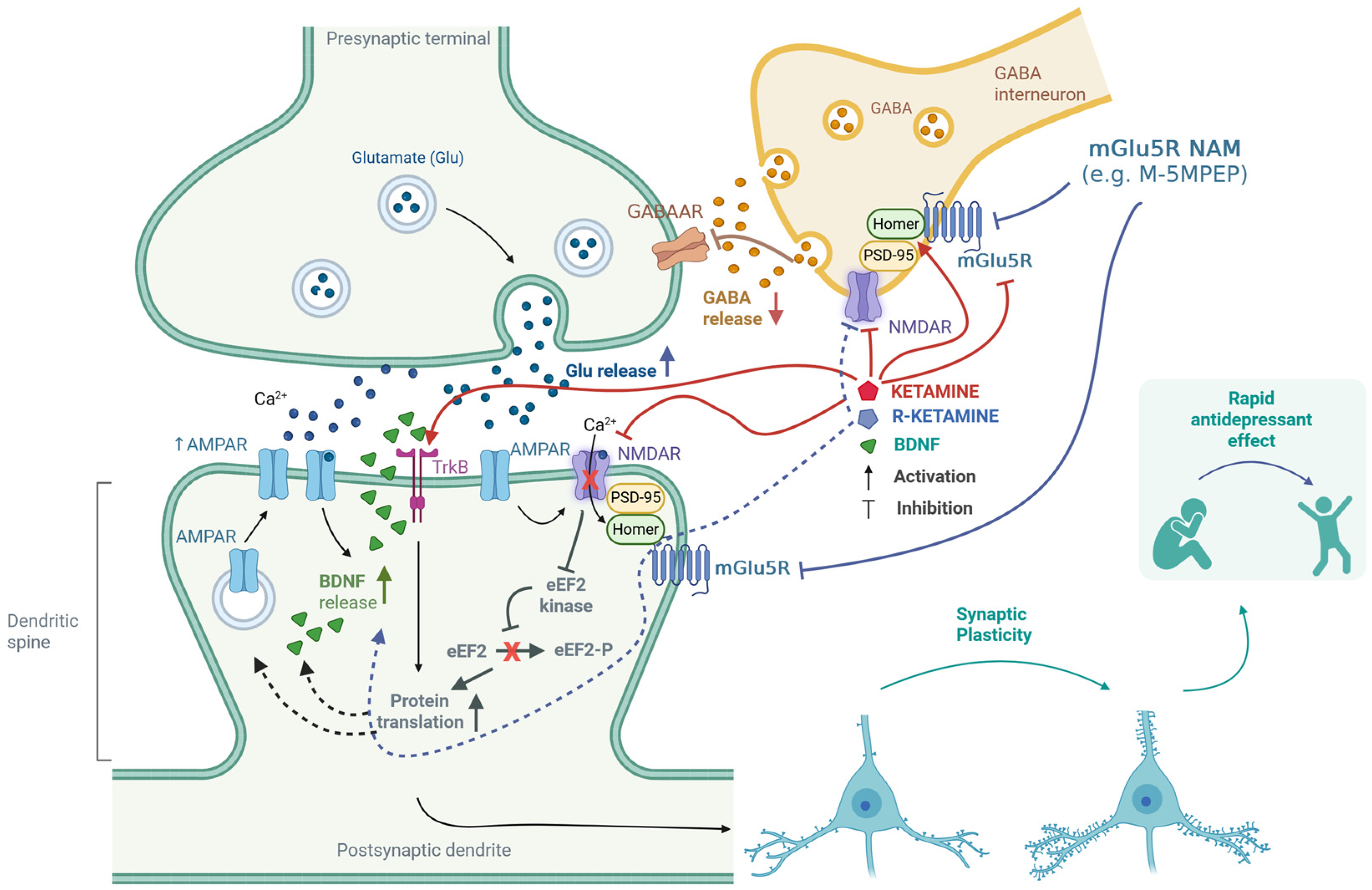

When examining how ketamine affects the regulation of the mGlu5 receptor, it is important to note that this receptor can exhibit constitutive (agonist-independent) activity. Homer proteins bind directly to the carboxy-terminal intracellular domains of the mGlu5 receptor and regulate this activity. Research by Ango et al. [65] has shown that increased levels of Homer1a can induce constitutive activity in the mGlu5 receptor within neurons. As previously mentioned, activating the mGlu5 receptor seems to inhibit the antidepressant effects of ketamine [69]. This implies that pharmacologically blocking the mGlu5 receptor may enhance the antidepressant effects of ketamine. This potential benefit may explain why co-administering ketamine with mGlu5 receptor NAMs is effective. The proposed mechanisms of action of the mGlu5 antagonist in combination with ketamine or its enantiomers are comprehensively shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Putative mechanisms for the enhancement of ketamine’s antidepressant effects through antagonism of the mGlu5 receptor. Ketamine inhibits GABAergic interneurons by blocking NMDA receptors, which leads to the disinhibition of glutamatergic neurons [9]. Furthermore, both ketamine and (R)-ketamine reduce the availability of mGlu5 receptors [61,62,63,64]. These receptors are functionally linked to NMDA receptors through the Homer proteins and Shank proteins—a part of the PSD-95 complex [81,82]. Homer proteins play a crucial role in regulating the interaction between NMDA and mGlu5 receptors [83,84,85]. Ketamine can disrupt the regulatory mechanisms of Homer proteins, affecting the interplay between mGlu5 and NMDA receptors [86,87,88,89]. The release of glutamate stimulates AMPA receptors, which subsequently activates NMDA receptors. This process triggers the release of BDNF, further activating TrkB receptors [10,13]. Additionally, ketamine can directly bind to the TrkB receptor [17]. The activation of TrkB initiates intracellular signaling cascades that promote protein translation. The regulation of eEF2 kinase [13] is essential in this context—the synergistic effect of (R)-ketamine and the mGlu5 receptor NAM was linked to changes in the levels of eEF2 and TrkB, but not mTOR [64]. These processes enhance synaptic plasticity, which is fundamental to the rapid antidepressant effect [10,11,12,13,61,64,65]. Created in BioRender. Pałucha-Poniewiera, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/0xfrbdi (accessed on 17 November 2025).

8. Conclusions

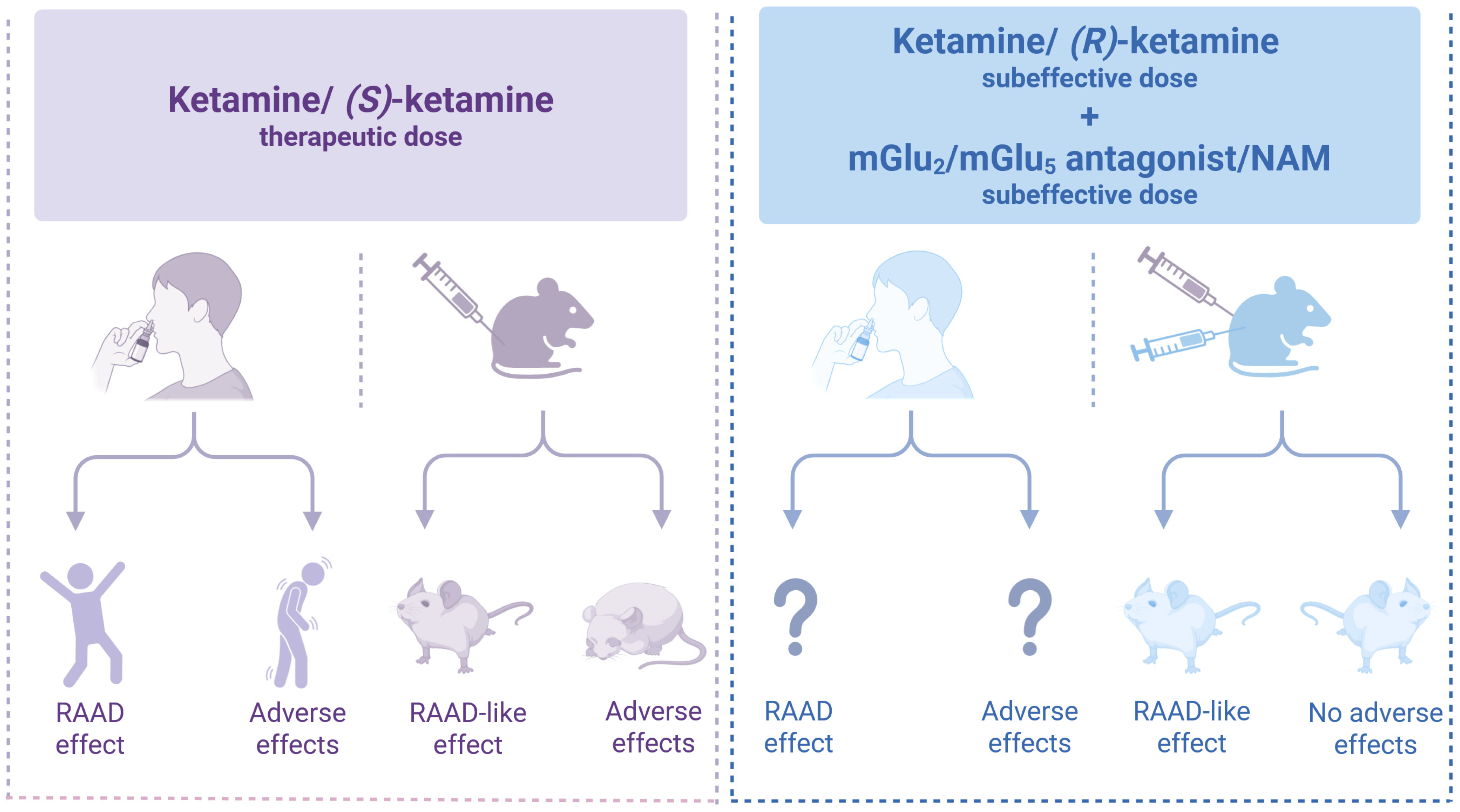

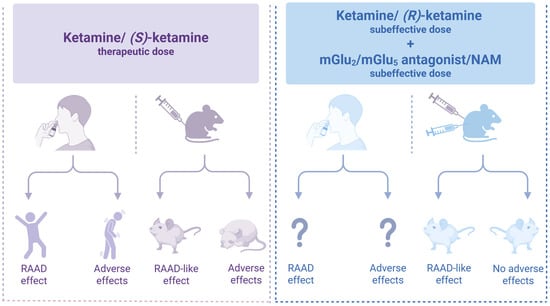

Improving the quality of therapy involves enhancing both the efficacy and safety of medications. In the case of (S)-ketamine, used for the treatment of TRD, the side effects play a significant role in its overall action profile. Addressing these undesirable effects poses a considerable challenge in modern psychopharmacology. One strategy to mitigate these effects is to use substances that modulate glutamatergic transmission through mGlu receptors. Preclinical research has shown that certain ligands for these receptors, including mGlu2 and mGlu5 antagonists or NAMs, resemble the cellular and molecular mechanisms of ketamine and its enantiomers. Blocking these receptors may enhance the antidepressant effects of ketamine or its safer enantiomer, (R)-ketamine, enabling a lower therapeutic dose while reducing the likelihood of adverse effects (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Co-administration of subthreshold doses of ketamine or (R)-ketamine with an mGlu2 o mGlu5 antagonist or NAM produces antidepressant-like effects [21,38,51,53,54,56,59,64,69] similar to (S)-ketamine [8,12,13,15,29,30,35,38,53,54] but without adverse effects [38,53,54]. Created in BioRender. Pałucha-Poniewiera, A. (2025) https://BioRender.com/0wk7zeg (accessed on 17 November 2025).

It is worth noting that this review expands the range of mGlu receptor ligands that enhance the effects of ketamine to include the partial NAM of the mGlu5 receptor. As a result, the potential for a synergistic effect with ketamine in producing antidepressant-like outcomes is not confined to mGlu2 receptor ligands, which have been the primary focus of research in this area for nearly a decade. Furthermore, in our analysis of the enhancement of ketamine’s action by mGlu ligands, we propose for the first time that (R)-ketamine, rather than (S)-ketamine, may be involved in this mechanism, thus opening avenues for further research.

The therapeutic approach proposed in this review could potentially improve the safety profile of ketamine and its enantiomers in the treatment of depression. However, further research, especially clinical trials, including evaluation of the antidepressant effects and safety profile of combined low doses of ketamine enantiomers with mGlu2 and mGlu5 receptor antagonists, is necessary to validate these findings. Until we obtain the results of these studies, the question marks in Figure 3 remain. Thus, the hypothesis presented in this work has not been clinically validated, which is a significant limitation. However, a review of preclinical studies showing promising results may encourage the implementation of the proposed strategy in clinical settings. Only by doing so can we determine whether the findings from studies using animal models correlate with the effects observed in patients.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript the author used Grammarly Business App for Windows (the writing assistant software tool, 14.1266.0) for the purposes of reviewing the spelling, grammar, and tone of the writing and BioRender: Scientific Image and Illustration Software to make diagrams. The author has reviewed and edited the output and takes full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMPA | alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| BOLD | blood oxygenation level-dependent |

| CUMS | chronic unpredictable mild stress |

| eEF2 | eukaryotic elongation factor 2 |

| FST | forced swim test |

| GABA | gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| HNK | hydroxynorketamine |

| LTP | long-term potentiation |

| mGlu receptor | metabotropic glutamate receptor |

| M-5MPEP | 2-(2-(3-methoxyphenyl)ethynyl)-5-methylpyridine |

| mPFC | medial prefrontal cortex |

| mTOR | mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NAM | negative allosteric modulator |

| NMDA | N-methyl-D-aspartic acid |

| NOR | novel object recognition |

| PAM | positive allosteric modulator |

| PCP | phencyclidine |

| PET | positron emission tomography |

| PFC | prefrontal cortex |

| phMRI | pharmacologic magnetic resonance imaging |

| PSD-95 | postsynaptic density 95 |

| qEEG | quantitative electroencephalography |

| RAAD | rapid-acting antidepressant drug |

| SDS | social defeat stress |

| SSRI | selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| TRD | treatment-resistant depression |

| TrkB | tropomyosin receptor kinase B |

| TST | tail suspension test |

References

- Mahase, E. Esketamine is approved in Europe for treating resistant major depressive disorder. BMJ 2019, 367, l7069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobo, W.V.; Vande Voort, J.L.; Croarkin, P.E.; Leung, J.G.; Tye, S.J.; Frye, M.A. Ketamine for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar major depression: Critical review and implications for clinical practice. Depress. Anxiety 2016, 33, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidus, K.A.; Levitch, C.F.; Perez, A.M.; Brallier, J.W.; Parides, M.K.; Soleimani, L.; Feder, A.; Iosifescu, D.V.; Charney, D.S.; Murrough, J.W. A randomized controlled trial of intranasal ketamine in major depressive disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 2014, 76, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarate, C.A., Jr.; Singh, J.B.; Carlson, P.J.; Brutsche, N.E.; Ameli, R.; Luckenbaugh, D.A.; Charney, D.S.; Manji, H.K. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006, 63, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- aan het Rot, M.; Collins, K.A.; Murrough, J.W.; Perez, A.M.; Reich, D.L.; Charney, D.S.; Mathew, S.J. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biol. Psychiatry 2010, 67, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystal, J.H.; Karper, L.P.; Seibyl, J.P.; Freeman, G.K.; Delaney, R.; Bremner, J.D.; Heninger, G.R.; Bowers, M.B., Jr.; Charney, D.S. Subanesthetic effects of the noncompetitive NMDA antagonist, ketamine, in humans. Psychotomimetic, perceptual, cognitive, and neuroendocrine responses. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1994, 51, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Vlisides, P.E. Ketamine: 50 years of modulating the mind. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanos, P.; Brown, K.A.; Georgiou, P.; Yuan, P.; Zarate, C.A., Jr.; Thompson, S.M.; Gould, T.D. NMDA receptor activation-dependent antidepressant-relevant behavioral and synaptic actions of ketamine. J. Neurosci. 2023, 43, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, B.; Adams, B.; Verma, A.; Daly, D. Activation of glutamatergic neurotransmission by ketamine: A novel step in the pathway from NMDA receptor blockade to dopaminergic and cognitive disruptions associated with the prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 2921–2927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Suzuki, K.; Kavalali, E.T.; Monteggia, L.M. Bridging rapid and sustained antidepressant effects of ketamine. Trends Mol. Med. 2023, 29, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, C.; Duman, R.S. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: A convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Lee, B.; Liu, R.J.; Banasr, M.; Dwyer, J.M.; Iwata, M.; Li, X.Y.; Aghajanian, G.; Duman, R.S. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science 2010, 329, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autry, A.E.; Adachi, M.; Nosyreva, E.; Na, E.S.; Los, M.F.; Cheng, P.F.; Kavalali, E.T.; Monteggia, L.M. NMDA receptor blockade at rest triggers rapid behavioural antidepressant responses. Nature 2011, 475, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray, N.H.; Schappi, J.M.; Singh, H.; Senese, N.B.; Rasenick, M.M. NMDAR-independent, cAMP-dependent antidepressant actions of ketamine. Mol. Psychiatry 2019, 24, 1833–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanos, P.; Moaddel, R.; Morris, P.J.; Georgiou, P.; Fischell, J.; Elmer, G.I.; Alkondon, M.; Yuan, P.; Pribut, H.J.; Singh, N.S.; et al. NMDAR inhibition-independent antidepressant actions of ketamine metabolites. Nature 2016, 533, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newport, D.J.; Carpenter, L.L.; McDonald, W.M.; Potash, J.B.; Tohen, M.; Nemeroff, C.B. APA Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and Treatments. Ketamine and other NMDA antagonists: Early clinical trials and possible mechanisms in depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 2015, 172, 950–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casarotto, P.C.; Girych, M.; Fred, S.M.; Kovaleva, V.; Moliner, R.; Enkavi, G.; Biojone, C.; Cannarozzo, C.; Sahu, M.P.; Kaurinkoski, K.; et al. Antidepressant drugs act by directly binding to TRKB neurotrophin receptors. Cell 2021, 184, 1299–1313.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinstein, M.R.; Carlton, M.L.; Di Ianni, T.; Ventriglia, E.N.; Rizzo, A.; Gomez, J.L.; Budinich, R.C.; Shaham, Y.; Airan, R.D.; Zarate, C.A., Jr.; et al. Mu opioid receptor activation mediates (S)-ketamine reinforcement in rats: Implications for abuse liability. Biol. Psychiatry 2022, 93, 1118–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, H.; Demers, J.C.; Biesiada, J.; Golani, L.K.; Cerne, R.; Smith, J.L.; Szostak, M.; Witkin, J.M. (R)-(-)-ketamine: The promise of a novel treatment for psychiatric and neurological disorders. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaki, S.; Ago, Y.; Palucha-Paniewiera, A.; Matrisciano, F.; Pilc, A. mGlu2/3 and mGlu5 receptors: Potential targets for novel antidepressants. Neuropharmacology 2013, 66, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pałucha-Poniewiera, A.; Rafało-Ulińska, A.; Santocki, M.; Babii, Y.; Kaczorowska, K. Partial mGlu5 receptor NAM, M-5MPEP, induces rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects in the BDNF-dependent mechanism and enhances (R)-ketamine action in mice. Pharmacol. Rep. 2024, 76, 504–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkin, J.M. mGlu2/3 receptor antagonism: A mechanism to induce rapid antidepressant effects without ketamine-associated side-effects. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2020, 190, 172854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, J.M.; Lepack, A.E.; Duman, R.S. mTOR activation is required for the antidepressant effects of mGluR2/3 blockade. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 15, 429–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, K.; Iijima, M.; Funakoshi, T.; Chaki, S. 5-HT(1A) receptor stimulation in the medial prefrontal cortex mediates the antidepressant effects of mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist in mice. Neuropharmacology 2018, 137, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koike, H.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S. Involvement of the mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in the antidepressant-like effect of group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists. Neuropharmacology 2011, 61, 1419–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepack, A.E.; Bang, E.; Lee, B.; Dwyer, J.M.; Duman, R.S. Fast-acting antidepressants rapidly stimulate ERK signaling and BDNF release in primary neuronal cultures. Neuropharmacology 2016, 111, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, K.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S. Serotonin-1A receptor stimulation mediates effects of a metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptor antagonist, 2S-2-amino-2-(1S,2S-2-carboxycycloprop-1-yl)-3-(xanth-9-yl)propanoic acid (LY341495), and an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, ketamine, in the novelty-suppressed feeding test. Psychopharmacology 2014, 231, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukumoto, K.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S. The antidepressant effects of an mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist and ketamine require AMPA receptor stimulation in the mPFC and subsequent activation of the 5-HT neurons in the DRN. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 1046–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, H.; Chaki, S. Requirement of AMPA receptor stimulation for the sustained antidepressant activity of ketamine and LY341495 during the forced swim test in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 2014, 271, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkin, J.M.; Mitchell, S.N.; Wafford, K.A.; Carter, G.; Gilmour, G.; Li, J.; Eastwood, B.J.; Overshiner, C.; Li, X.; Rorick-Kehn, L.; et al. Comparative effects of LY3020371, a potent and selective metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) 2/3 receptor antagonist, and ketamine, a noncompetitive N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist in rodents: Evidence supporting the use of mGlu2/3 antagonists, for the treatment of depression. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2017, 361, 68–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koike, H.; Fukumoto, K.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S. Role of BDNF/TrkB signaling in antidepressant-like effects of a group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist in animal models of depression. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 238, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkin, J.M.; Monn, J.A.; Schoepp, D.D.; Li, X.; Overshiner, C.; Mitchell, S.N.; Carter, G.; Johnson, B.; Rasmussen, K.; Rorick-Kehn, L.M. The rapidly acting antidepressant ketamine and the mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist LY341495 rapidly engage dopaminergic mood circuits. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2016, 358, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, D.; Peng, H.Y.; Lin, T.B.; Lai, C.Y.; Hsieh, M.C.; Wen, Y.C.; Lee, A.S.; Wang, H.H.; Yang, P.S.; Chen, G.D.; et al. (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine rescues chronic stress-induced depression-like behavior through its actions in the midbrain periaqueductal gray. Neuropharmacology 2018, 139, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Tian, Z.; Fujita, Y.; Fujita, A.; Hino, N.; Iijima, M.; Hashimoto, K. Antidepressant-like actions of the mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist TP0178894 in the chronic social defeat stress model: Comparison with escitalopram. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2022, 212, 173316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhang, J.C.; Yao, W.; Ren, Q.; Ma, M.; Yang, C.; Chaki, S.; Hashimoto, K. Rapid and sustained antidepressant action of the mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist MGS0039 in the social defeat stress model: Comparison with ketamine. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwyer, J.M.; Lepack, A.E.; Duman, R.S. mGluR2/3 blockade produces rapid and long-lasting reversal of anhedonia caused by chronic stress exposure. J. Mol. Psychiatry 2013, 1, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałucha-Poniewiera, A.; Bobula, B.; Rafało-Ulińska, A.; Kaczorowska, K. Depression-like effects induced by chronic unpredictable mild stress in mice are rapidly reversed by a partial negative allosteric modulator of mGlu(5) receptor, M-5MPEP. Psychopharmacology 2024, 242, 1259–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pałucha-Poniewiera, A.; Podkowa, K.; Rafało-Ulińska, A. The group II mGlu receptor antagonist LY341495 induces a rapid antidepressant-like effect and enhances the effect of ketamine in the chronic unpredictable mild stress model of depression in C57BL/6J mice. Prog. NeuroPsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 109, 110239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witkin, J.M.; Monn, J.A.; Li, J.; Johnson, B.; McKinzie, D.L.; Wang, X.S.; Heinz, B.A.; Li, R.; Ornstein, P.L.; Smith, S.C.; et al. Preclinical predictors that the orthosteric mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist LY3020371 will not engender ketamine-associated neurotoxic, motor, cognitive, subjective, or abuse-liability-related effects. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2017, 155, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorrain, D.S.; Baccei, C.S.; Bristow, L.J.; Anderson, J.J.; Varney, M.A. Effects of ketamine and N-methyl-D-aspartate on glutamate and dopamine release in the rat prefrontal cortex: Modulation by a group II selective metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist LY379268. Neuroscience 2003, 117, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorrain, D.S.; Schaffhauser, H.; Campbell, U.C.; Baccei, C.S.; Correa, L.D.; Rowe, B.; Rodriguez, D.E.; Anderson, J.J.; Varney, M.A.; Pinkerton, A.B.; et al. Group II mGlu receptor activation suppresses norepinephrine release in the ventral hippocampus and locomotor responses to acute ketamine challenge. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003, 28, 1622–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartmell, J.; Schoepp, D.D. Regulation of neurotransmitter release by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J. Neurochem. 2000, 75, 889–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohishi, H.; Neki, A.; Mizuno, N. Distribution of a metabotropic glutamate receptor, mGluR2, in the central nervous system of the rat and mouse: An immunohistochemical study with a monoclonal antibody. Neurosci. Res. 1998, 30, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigemoto, R.; Kinoshita, A.; Wada, E.; Nomura, S.; Ohishi, H.; Takada, M.; Flor, P.J.; Neki, A.; Abe, T.; Nakanishi, S.; et al. Differential presynaptic localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 1997, 17, 7503–7522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, C.L.; Upadhyay, J.; Marek, G.J.; Baker, S.J.; Zhang, M.; Mezler, M.; Fox, G.B.; Day, M. Awake rat pharmacological magnetic resonance imaging as a translational pharmacodynamic biomarker: Metabotropic glutamate 2/3 agonist modulation of ketamine-induced blood oxygenation level dependence signals. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2011, 336, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, M.A.; Schmechtig, A.; Kotoula, V.; McColm, J.; Jackson, K.; Brittain, C.; Tauscher-Wisniewski, S.; Kinon, B.J.; Morrison, P.D.; Pollak, T.; et al. Group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist prodrugs LY2979165 and LY2140023 attenuate the functional imaging response to ketamine in healthy subjects. Psychopharmacology 2018, 235, 1875–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujáková, M.; Páleníček, T.; Brunovský, M.; Gorman, I.; Tylš, F.; Kubešová, A.; Řípová, D.; Krajča, V.; Horáček, J. The effect of ((-)-2-oxa-4-aminobicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (LY379268), an mGlu2/3 receptor agonist, on EEG power spectra and coherence in ketamine model of psychosis. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2014, 122, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiyoshi, T.; Hikichi, H.; Karasawa, J.; Chaki, S. Metabotropic glutamate receptors regulate cortical gamma hyperactivities elicited by ketamine in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 2014, 567, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, N.C.; Reddy, M.; Anderson, P.; Salzberg, M.R.; O’Brien, T.J.; Pinault, D. Acute administration of typical and atypical antipsychotics reduces EEG γ power, but only the preclinical compound LY379268 reduces the ketamine-induced rise in γ power. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012, 15, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiyoshi, T.; Marumo, T.; Hikichi, H.; Tomishima, Y.; Urabe, H.; Tamita, T.; Iida, I.; Yasuhara, A.; Karasawa, J.; Chaki, S. Neurophysiologic and antipsychotic profiles of TASP0433864, a novel positive allosteric modulator of metabotropic glutamate 2 receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2014, 351, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanos, P.; Highland, J.N.; Stewart, B.W.; Georgiou, P.; Jenne, C.E.; Lovett, J.; Morris, P.J.; Thomas, C.J.; Moaddel, R.; Zarate, C.A., Jr.; et al. (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine exerts mGlu2 receptor-dependent antidepressant actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 6441–6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaventura, J.; Gomez, J.L.; Carlton, M.L.; Lam, S.; Sanchez-Soto, M.; Morris, P.J.; Moaddel, R.; Kang, H.J.; Zanos, P.; Gould, T.D.; et al. Target deconvolution studies of (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine: An elusive search. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 4144–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkowa, K.; Pochwat, B.; Brański, P.; Pilc, A.; Pałucha-Poniewiera, A. Group II mGlu receptor antagonist LY341495 enhances the antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in the forced swim test in rats. Psychopharmacology 2016, 233, 2901–2914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafało-Ulińska, A.; Brański, P.; Pałucha-Poniewiera, A. Combined administration of (R)-ketamine and the mGlu2/3 receptor antagonist LY341495 induces rapid and sustained effects in the CUMS model of depression via a TrkB/BDNF-dependent mechanism. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Nelson, C.D.; Li, X.; Winters, C.A.; Azzam, R.; Sousa, A.A.; Leapman, R.D.; Gainer, H.; Sheng, M.; Reese, T.S. PSD-95 is required to sustain the molecular organization of the postsynaptic density. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 6329–6338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałucha-Poniewiera, A.; Podkowa, K.; Pilc, A. Role of AMPA receptor stimulation and TrkB signaling in the antidepressant-like effect of ketamine co-administered with a group II mGlu receptor antagonist, LY341495, in the forced swim test in rats. Behav. Pharmacol. 2019, 30, 471–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.K.; Hien, L.T.; Park, M.K.; Choi, A.J.; Seog, D.H.; Kim, S.H.; Park, S.W.; Lee, J.G. AMPA receptor-mTORC1 signaling activation is required for neuroplastic effects of LY341495 in rat hippocampal neurons. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Ajibola, M.I.; Gould, T.D. Rapid hippocampal synaptic potentiation induced by ketamine metabolite (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine persistently primes synaptic plasticity. Neuropsychopharmacology 2025, 50, 928–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pałucha-Poniewiera, A.; Bobula, B.; Rafało-Ulińska, A. The antidepressant-like activity and cognitive enhancing effects of the combined administration of (R)-ketamine and LY341495 in the CUMS model of depression in mice are related to the modulation of excitatory synaptic transmission and LTP in the PFC. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.A.; Komaki, A.; Salehi, I.; Sarihi, A.; Shahidi, S. Role of group II metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluR2/3) blockade on long-term potentiation in the dentate gyrus region of hippocampus in rats fed with high-fat diet. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLorenzo, C.; DellaGioia, N.; Bloch, M.; Sanacora, G.; Nabulsi, N.; Abdallah, C.; Yang, J.; Wen, R.; Mann, J.J.; Krystal, J.H.; et al. In vivo ketamine-induced changes in [11C]ABP688 binding to metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 5. Biol. Psychiatry 2015, 77, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esterlis, I.; DellaGioia, N.; Pietrzak, R.H.; Matuskey, D.; Nabulsi, N.; Abdallah, C.G.; Yang, J.; Pittenger, C.; Sanacora, G.; Krystal, J.H.; et al. Ketamine-induced reduction in mGluR5 availability is associated with an antidepressant response: An [11C]ABP688 and PET imaging study in depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2018, 23, 824–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, W.; Zhang, H.; Yao, Z.; Che, F.; Cao, Y.; Sun, H. mGluR5 mediates ketamine antidepressant response in susceptible rats exposed to prenatal stress. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 272, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałucha-Poniewiera, A.; Rafało-Ulińska, A.; Faron-Górecka, A.; Pabian, P.; Kaczorowska, K. (R)-ketamine induces mGlu5 receptor-dependent antidepressant-like effects in the chronic unpredictable mild stress model of depression in mice. Psychopharmacology 2025, 242, 2401–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ango, F.; Prézeau, L.; Muller, T.; Tu, J.C.; Xiao, B.; Worley, P.F.; Pin, J.P.; Bockaert, J.; Fagni, L. Agonist-independent activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors by the intracellular protein Homer. Nature 2001, 411, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuxe, K.; Borroto-Escuela, D.O. Basimglurant for treatment of major depressive disorder: A novel negative allosteric modulator of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2015, 24, 1247–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T.; Takata, M.; Kitaichi, M.; Kassai, M.; Inoue, M.; Ishikawa, C.; Hirose, W.; Yoshida, K.; Shimizu, I. DSR-98776, a novel selective mGlu5 receptor negative allosteric modulator with potent antidepressant and antimanic activity. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 757, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pałucha, A.; Brański, P.; Szewczyk, B.; Wierońska, J.M.; Kłak, K.; Pilc, A. Potential antidepressant-like effect of MTEP, a potent and highly selective mGluR5 antagonist. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2005, 81, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokalp, D.; Unal, G. The role of mGluR5 on the therapeutic effects of ketamine in Wistar rats. Psychopharmacology 2024, 241, 1399–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sou, J.-H.; Chan, M.-H.; Chen, H.-H. Ketamine, but not propofol, anaesthesia is regulated by metabotropic glutamate 5 receptors. Br. J. Anaesth. 2006, 96, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Chan, M.-H.; Chiu, P.-H.; Sou, J.-H.; Chen, H.-H. Attenuation of ketamine-evoked behavioral responses by mGluR5 positive modulators in mice. Psychopharmacology 2008, 198, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.W.; Amato, R.J.; Bubser, M.; Joffe, M.E.; Nedelcovych, M.T.; Thompson, A.D.; Nickols, H.H.; Yuh, J.P.; Zhan, X.; Felts, A.S.; et al. Partial mGlu5 negative allosteric modulators attenuate cocaine-mediated behaviors and lack psy-chotomimetic-like effects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016, 41, 1166–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayoun, H.; Stefani, M.R.; Adams, B.W.; Tamagan, G.D.; Moghaddam, B. Functional interaction between NMDA and mGlu5 receptors: Effects on working memory, instrumental learning, motor behaviors, and dopamine release. Neuropsychopharmacology 2004, 29, 1259–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinney, G.G.; Burno, M.; Campbell, U.C.; Hernandez, L.M.; Rodriguez, D.; Bristow, L.J.; Conn, P.J. Metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptors modulate locomotor activity and sensorimotor gating in rodents. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holter, K.M.; Lekander, A.D.; LaValley, C.M.; Bedingham, E.G.; Pierce, B.E.; Sands, L.P., 3rd; Lindsley, C.W.; Jones, C.K.; Gould, R.W. Partial mGlu5 negative allosteric modulator M-5MPEP demonstrates antidepressant-like effects on sleep without affecting cognition or quantitative EEG. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 700822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, H.; Hubert, G.W.; Smith, Y.; Levey, A.I.; Conn, P.J. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 has direct excitatory effects and potentiates NMDA receptor currents in neurons of the subthalamic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 7871–7879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-H.; Liao, P.-F.; Chan, M.-H. mGluR5 positive modulators both potentiate activation and restore inhibition in NMDA receptors by PKC dependent pathway. J. Biomed. Sci. 2011, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Guo, M.; Xue, B.; Mao, L.; Wang, J.Q. Differential regulation of CaMKIIα interactions with mGluR5 and NMDA receptors by Ca2+ in neurons. J. Neurochem. 2013, 127, 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, S.A.; Jackson, M.F.; Al-Mahrouki, A.; Roder, J.C.; Orser, B.A.; MacDonald, J.F. Co-stimulation of mGluR5 and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors is required for potentiation of excitatory synaptic transmission in hippocampal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 27742–27749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbrock, H.; Kramer, G.; Hobson, S.; Koros, E.; Grundl, M.; Grauert, M.; Reymann, K.G.; Schröder, U.H. Functional interaction of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 and NMDA-receptor by a metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 positive allosteric modulator. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 639, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perroy, J.; Raynaud, F.; Homburger, V.; Rousset, M.C.; Telley, L.; Bockaert, J.; Fagni, L. Direct interaction enables cross-talk between ionotropic and group I metabotropic glutamate receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 6799–6805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.C.; Xiao, B.; Naisbitt, S.; Yuan, J.P.; Petralia, R.S.; Brakeman, P.; Doan, A.; Aakalu, V.K.; Lanahan, A.A.; Sheng, M.; et al. Coupling of mGluR/Homer and PSD-95 complexes by the shank family of postsynaptic density proteins. Neuron 1999, 23, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockaert, J.; Perroy, J.; Ango, F. The complex formed by group I Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor (mGluR) and Homer1a plays a central role in metaplasticity and homeostatic synaptic scaling. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 5567–5578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, N.E.; Trent, S.; Thomas, K.L.; Hall, J. Regulation and function of activity-dependent homer in synaptic plasticity. Mol. Neuropsychiatry 2019, 5, 147–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammermeier, P.J.; Worley, P.F. Homer 1a uncouples metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 from postsynaptic effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6055–6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bartolomeis, A.; Sarappa, C.; Buonaguro, E.F.; Marmo, F.; Eramo, A.; Tomasetti, C.; Iasevoli, F. Different effects of the NMDA receptor antagonists ketamine, MK-801, and memantine on postsynaptic density transcripts and their topography: Role of Homer signaling, and implications for novel antipsychotic and pro-cognitive targets in psychosis. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serchov, T.; Clement, H.W.; Schwarz, M.K.; Iasevoli, F.; Tosh, D.K.; Idzko, M.; Jacobson, K.A.; de Bartolomeis, A.; Normann, C.; Biber, K.; et al. Increased signaling via adenosine A1 receptors, sleep deprivation, imipramine, and ketamine inhibit depressive-like behavior via induction of Homer1a. Neuron 2015, 87, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serchov, T.; Heumann, R.; van Calker, D.; Biber, K. Signaling pathways regulating Homer1a expression: Implications for antidepressant therapy. Biol. Chem. 2016, 397, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aloisi, E.; Le Corf, K.; Dupuis, J.; Zhang, P.; Ginger, M.; Labrousse, V.; Spatuzza, M.; Haberl, M.G.; Costa, L.; Shigemoto, R.; et al. Altered surface mGluR5 dynamics provoke synaptic NMDAR dysfunction and cognitive defects in Fmr1 knockout mice. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmeseiny, O.S.A.; Müller, H.K. A molecular perspective on mGluR5 regulation in the antidepressant effect of ketamine. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 200, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).