Radiation-Induced Fibrosis (RIF) in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC): A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

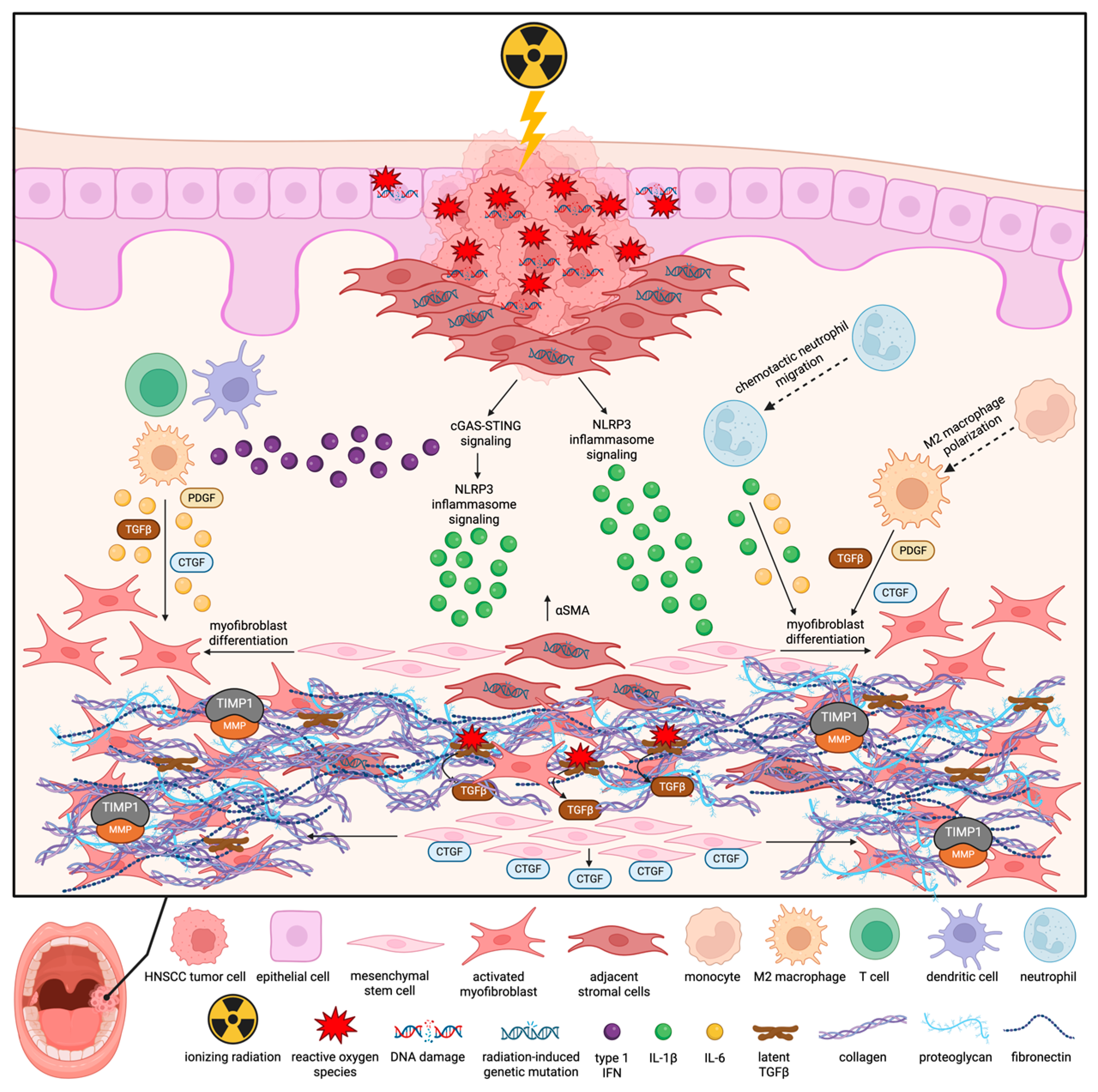

2. Mechanistic Insights

3. Methods for Diagnosing and Studying RIF in HNSCC

4. Conventional Therapies for RIF in HNSCC

| Treatment Regimen | Patient Cohort | RIF Presentation | Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PENTOX (PTX 800 mg/d; Vit E 1000 U/d) administered orally for at least 6 months | Breast, and HNSCC patients (N = 43) | Symptomatic RIF involving the skin and underlying tissues occurring within 1 year of RT (ranging from 45 to 75 Gy) | 53% mean reduction in fibrosis surface area after 6 months; mean linear dimensions diminished from 6.5 to 4.5 cm; SOMA injury score improved from 13.2 to 6.9 after 12 months | Phase 2 trial [73] |

| PENTOX (PTX 400 mg; Vit E 290–350 mg) administered orally twice daily | Breast and HNSCC patients (N = 54) | Severe and symptomatic RIF (Breast cancer patients N = 24; mean RT dose 45.7 Gy; mean duration of 31 months prior to intervention) (Head and neck cancer patients N = 30; mean RT dose 67.8 Gy; mean duration of 42 months prior to intervention) | 75% reported subjective improvement in RIF as reported by LENT-SOMA score in breast cancer patients after 14 months; 23% reported subjective improvement in head and neck patients after 12 months | Retrospective study [75] |

| Sodermix cream (280 U/g superoxide dismutase) once daily on the fibrotic area for 3 months | HNSCC patients (N = 68) | 86% of patients received RT more than 6 months before treatment initiation, with the majority having grade 1–2 fibrosis (according to CTCAE scoring) | 46.6% improvement in study arm vs. 43.3% in placebo control | Randomized, prospective, blinded study [106] |

| Pravastatin (40 mg/d) for 12 months | HNSCC patients (N = 40) | Grade 2 or greater cutaneous and subcutaneous neck fibrosis (according to CTCAE scoring) | Ultrasonography confirmed a reduction in RIF thickness by >30% in 35.7% of patients after 12 months; the CTCAE score was improved in 50% of patients | Phase 2 trial [111] |

5. Experimental Therapies for RIF in HNSCC

5.1. Anti-Fibrotic Agents Approved for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

5.2. Neutralizing Antibodies for Targeting Pro-Fibrotic Factors

5.3. Natural Antioxidants

5.4. Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC) Therapy

5.5. Modulation of the DNA Damage Response

| Treatment | Anti-Fibrotic Mechanism | Anti-Fibrotic Effects in Non-HNSCC RIF Models |

|---|---|---|

| Pirfenidone | Inhibition of TGFβ-mediated fibroblast proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation, collagen synthesis, fibronectin production, and ECM deposition [112] | Reduced collagen deposition and fibrosis in mouse models of pulmonary RIF [147,148] |

| Nintedanib | Inhibits TGFβ signaling, downregulating ECM production and induction of αSMA [114] | Reduced collagen deposition in a mouse model of pulmonary RIF [115] |

| Imatinib | Inhibits c-Abl kinase activation of fibroblasts post-TGFβ induction [119] | Markedly attenuated development of pulmonary RIF in mice [120] |

| Fresolimumab | Inhibits TGFβ-mediated pro-fibrotic effects | Reduced pulmonary RIF development in mice [149] |

| Pamrevlumab | Inhibits CTGF-mediated pro-fibrotic effects | Reduced lung remodeling in mice at 24 weeks post-RT [124] |

| Curcumin | Increases antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), ameliorating ROS-mediated fibrotic effects [125]. Shown to attenuate pro-inflammatory molecules such as NF-κB, COX2, IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNFα [150] | Administration before and after RT protected against skin damage and pulmonary RIF in rats [125,150] |

| Rosmarinic acid | Attenuates ROS via indirect activation of the antioxidant response via PGC1-a/NOX4 and inhibition of inflammatory factors TNFα, IL-6, and IL-2, reducing collagen expression [127] | Administration protected against pulmonary RIF in rats [151] |

| Amifostine | Ameliorates ROS via activation of antioxidant enzymes such as SOD [152]. Reduces TGFβ-mediated signaling and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNFα, IL-6, and IL-1β [153,154] | Protects against pulmonary RIF and vocal fold and subglottic gland RIF in rats [152,153,154] |

| Mesenchymal stem cell therapy | Inhibited TGFβ activation of Wnt/β -catenin signaling, suppressing expression of αSMA, fibroblast proliferation, and collagen expression [132,137] | Attenuated RT-induced lung injury and fibrosis in mice [132,137] |

| STING inhibition | Inhibits PERK/eIF2α signaling mediating myofibroblast differentiation [141] | Knockdown of STING reduced collagen deposition and αSMA expression in a mouse model of pulmonary RIF [141] |

6. Alternative Options for RIF Reduction in HNSCC

6.1. Alternative RT Techniques

6.2. Dietary and Nutritional Support

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barsouk, A.; Aluru, J.S.; Rawla, P.; Saginala, K.; Barsouk, A. Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention of Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med. Sci. 2023, 11, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Huang, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, E.; Tu, Y.; Zou, J.; Su, K.; Yi, H.; Yin, S. Global burden of head and neck cancers from 1990 to 2019. iScience 2024, 27, 109282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, M.; Creaney, G.; Schache, A.; Ingarfield, K.; Conway, D.I. Reviewing the epidemiology of head and neck cancer: Definitions, trends and risk factors. Br. Dent. J. 2022, 233, 780–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordzińska-Rak, A.; Telejko, I.; Adamczuk, G.; Trombik, T.; Stepulak, A.; Błaszczak, E. Advancing Head and Neck Cancer Therapies: From Conventional Treatments to Emerging Strategies. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Economopoulou, P.; de Bree, R.; Kotsantis, I.; Psyrri, A. Diagnostic Tumor Markers in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC) in the Clinical Setting. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepikhova, T.; Karhemo, P.-R.; Louhimo, R.; Yadav, B.; Murumägi, A.; Kulesskiy, E.; Kivento, M.; Sihto, H.; Grénman, R.; Syrjänen, S.M.; et al. Drug-Sensitivity Screening and Genomic Characterization of 45 HPV-Negative Head and Neck Carcinoma Cell Lines for Novel Biomarkers of Drug Efficacy. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018, 17, 2060–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, K.S.; Somara, S.; Ko, H.C.; Thatai, P.; Quintana, A.; Wallen, Z.D.; Green, M.F.; Mehrotra, R.; McGuigan, S.; Pang, L.; et al. Biomarkers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Unraveling the path to precision immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1473706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P.; Linnenbach, A.; South, A.P.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.; Curry, J.M.; Johnson, J.M.; Harshyne, L.A.; Mahoney, M.G.; Luginbuhl, A.J.; Vadigepalli, R. Tumor microenvironment governs the prognostic landscape of immunotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: A computational model-guided analysis. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2025, 21, e1013127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfouzan, A.F. Radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. Saudi Med. J. 2021, 42, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, T.; Agarwal, J.; Jain, S.; Phurailatpam, R.; Kannan, S.; Ghosh-Laskar, S.; Murthy, V.; Budrukkar, A.; Dinshaw, K.; Prabhash, K.; et al. Three-dimensional conformal radiotherapy (3D-CRT) versus intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A randomized controlled trial. Radiother. Oncol. 2012, 104, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Machiels, J.P.; René Leemans, C.; Golusinski, W.; Grau, C.; Licitra, L.; Gregoire, V. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, larynx, oropharynx and hypopharynx: EHNS-ESMO-ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciubba, J.J.; Goldenberg, D. Oral complications of radiotherapy. Lancet Oncol. 2006, 7, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharzai, L.A.; Mierzwa, M.L.; Peipert, J.D.; Kirtane, K.; Casper, K.; Yadav, P.; Rothrock, N.; Cella, D.; Shaunfield, S. Monitoring Adverse Effects of Radiation Therapy in Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: The FACT-HN-RAD Patient-Reported Outcome Measure. JAMA Otolaryngol.–Head Neck Surg. 2023, 149, 884–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, P.H.P.; Reali, R.M.; Decnop, M.; Souza, S.A.; Teixeira, L.A.B.; Júnior, A.L.; Sarpi, M.O.; Cintra, M.B.; Pinho, M.C.; Garcia, M.R.T. Adverse Radiation Therapy Effects in the Treatment of Head and Neck Tumors. Radiographics 2022, 42, 806–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevens, D.; Duprez, F.; Daisne, J.F.; Laenen, A.; de Neve, W.; Nuyts, S. Radiotherapy induced dermatitis is a strong predictor for late fibrosis in head and neck cancer. The development of a predictive model for late fibrosis. Radiother. Oncol. 2017, 122, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.N.; Simmons, B.J.; Wolfson, A.H.; Nouri, K. Acute and Chronic Cutaneous Reactions to Ionizing Radiation Therapy. Dermatol. Ther. 2016, 6, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, A.; Khan, S.; Aden, D.; Shrama, A. Unravelling the significance of fibrotic cancer stroma: A key player in the tumour microenvironment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2025, 21, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Herch, I.; Tornaas, S.; Dongre, H.N.; Costea, D.E. Heterogeneity of cancer-associated fibroblasts and tumor-promoting roles in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1340024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymakers, L.; Demmers, T.J.; Meijer, G.J.; Molenaar, I.Q.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Intven, M.P.W.; Leusen, J.H.W.; Olofsen, P.A.; Daamen, L.A. The Effect of Radiation Treatment of Solid Tumors on Neutrophil Infiltration and Function: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 120, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Liu, Z.; He, Y. Radiation-induced fibrosis: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies from an immune microenvironment perspective. Immunology 2024, 172, 533–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, S.C.; Walsh, B.J.; Bennett, S.; Robbins, J.M.; Foulcher, E.; Morgan, G.W.; Penny, R.; Breit, S.N. Both in vitro and in vivo irradiation are associated with induction of macrophage-derived fibroblast growth factors. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1996, 103, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, M.; Lefaix, J.-L.; Delanian, S. TGF-β1 and radiation fibrosis: A master switch and a specific therapeutic target? Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2000, 47, 277–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, A.; Löffler, H.; Bamberg, M.; Rodemann, H.P. Molecular and cellular basis of radiation fibrosis. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 1998, 73, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yarnold, J.; Vozenin Brotons, M.-C. Pathogenetic mechanisms in radiation fibrosis. Radiother. Oncol. 2010, 97, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasek, J.J.; Gabbiani, G.; Hinz, B.; Chaponnier, C.; Brown, R.A. Myofibroblasts and mechano-regulation of connective tissue remodelling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2002, 3, 349–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbury, C.B.; Yarnold, J.R. Radiation Fibrosis—Current Clinical and Therapeutic Perspectives. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 24, 657–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, J.M.; New, J.; Hamilton, C.D.; Lominska, C.; Shnayder, Y.; Thomas, S.M. Radiation-induced fibrosis: Mechanisms and implications for therapy. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 141, 1985–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fijardo, M.; Kwan, J.Y.Y.; Bissey, P.A.; Citrin, D.E.; Yip, K.W.; Liu, F.F. The clinical manifestations and molecular pathogenesis of radiation fibrosis. EBioMedicine 2024, 103, 105089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimura, T.; Sasatani, M.; Kawai, H.; Kamiya, K.; Kobayashi, J.; Komatsu, K.; Kunugita, N. Radiation-Induced Myofibroblasts Promote Tumor Growth via Mitochondrial ROS–Activated TGFβ Signaling. Mol. Cancer Res. 2018, 16, 1676–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artlett, C.M. The Mechanism and Regulation of the NLRP3 Inflammasome during Fibrosis. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Robbins, M.E. Inflammation and chronic oxidative stress in radiation-induced late normal tissue injury: Therapeutic implications. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.M.; Desai, L.P. Reciprocal regulation of TGF-β and reactive oxygen species: A perverse cycle for fibrosis. Redox Biol. 2015, 6, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobling, M.F.; Mott, J.D.; Finnegan, M.T.; Jurukovski, V.; Erickson, A.C.; Walian, P.J.; Taylor, S.E.; Ledbetter, S.; Lawrence, C.M.; Rifkin, D.B.; et al. Isoform-specific activation of latent transforming growth factor beta (LTGF-beta) by reactive oxygen species. Radiat. Res. 2006, 166, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, K.E.; Wong, C.; Teng, Y.; Spong, S. CTGF is a central mediator of tissue remodeling and fibrosis and its inhibition can reverse the process of fibrosis. Fibrogenes. Tissue Repair 2012, 5, S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrishrimal, S.; Kosmacek, E.A.; Oberley-Deegan, R.E. Reactive Oxygen Species Drive Epigenetic Changes in Radiation-Induced Fibrosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 4278658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavragani, I.V.; Nikitaki, Z.; Kalospyros, S.A.; Georgakilas, A.G. Ionizing Radiation and Complex DNA Damage: From Prediction to Detection Challenges and Biological Significance. Cancers 2019, 11, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sage, E.; Shikazono, N. Radiation-induced clustered DNA lesions: Repair and mutagenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 107, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durante, M.; Formenti, S.C. Radiation-Induced Chromosomal Aberrations and Immunotherapy: Micronuclei, Cytosolic DNA, and Interferon-Production Pathway. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storozynsky, Q.; Hitt, M.M. The Impact of Radiation-Induced DNA Damage on cGAS-STING-Mediated Immune Responses to Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Zhang, F.; Cao, J.; Xiong, W. Role of cGAS-STING pathway in fibrotic disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2025, 221, 107971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zou, W.; Cao, Y. Radiation-induced cellular senescence and adaptive response: Mechanistic interplay and implications. Radiat. Med. Prot. 2025, 6, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Dong, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guan, B.; Lu, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Meng, A.; et al. Potential role of senescent macrophages in radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.D.; Stetz, J.; Pajak, T.F. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1995, 31, 1341–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoeller, U.; Tribius, S.; Kuhlmey, A.; Grader, K.; Fehlauer, F.; Alberti, W. Increasing the rate of late toxicity by changing the score? A comparison of RTOG/EORTC and LENT/SOMA scores. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2003, 55, 1013–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Renslo, B.; Alapati, R.; Penn, J.; Yu, K.M.; Sutton, S.; Virgen, C.G.; Sawaf, T.; Sykes, K.J.; Thomas, S.M.; Materia, F.T.; et al. Quantification of Radiation-Induced Fibrosis in Head and Neck Cancer Patients Using Shear Wave Elastography. Cureus 2024, 16, e71159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montesi, S.B.; Désogère, P.; Fuchs, B.C.; Caravan, P. Molecular imaging of fibrosis: Recent advances and future directions. J. Clin. Investig. 2019, 129, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polasek, M.; Fuchs, B.C.; Uppal, R.; Schühle, D.T.; Alford, J.K.; Loving, G.S.; Yamada, S.; Wei, L.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Guimaraes, A.R.; et al. Molecular MR imaging of liver fibrosis: A feasibility study using rat and mouse models. J. Hepatol. 2012, 57, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caravan, P.; Yang, Y.; Zachariah, R.; Schmitt, A.; Mino-Kenudson, M.; Chen, H.H.; Sosnovik, D.E.; Dai, G.; Fuchs, B.C.; Lanuti, M. Molecular magnetic resonance imaging of pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2013, 49, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Yalamanchali, S.; New, J.; Parsel, S.; New, N.; Holcomb, A.; Gunewardena, S.; Tawfik, O.; Lominska, C.; Kimler, B.F.; et al. Development and Characterization of an In Vitro Model for Radiation-Induced Fibrosis. Radiat. Res. 2018, 189, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javvadi, P.; Hertan, L.; Kosoff, R.; Datta, T.; Kolev, J.; Mick, R.; Tuttle, S.W.; Koumenis, C. Thioredoxin reductase-1 mediates curcumin-induced radiosensitization of squamous carcinoma cells. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 1941–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttle, S.; Hertan, L.; Daurio, N.; Porter, S.; Kaushick, C.; Li, D.; Myamoto, S.; Lin, A.; O’Malley, B.W.; Koumenis, C. The chemopreventive and clinically used agent curcumin sensitizes HPV(-) but not HPV(+) HNSCC to ionizing radiation, in vitro and in a mouse orthotopic model. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2012, 13, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millen, R.; De Kort, W.W.B.; Koomen, M.; van Son, G.J.F.; Gobits, R.; Penning de Vries, B.; Begthel, H.; Zandvliet, M.; Doornaert, P.; Raaijmakers, C.P.J.; et al. Patient-derived head and neck cancer organoids allow treatment stratification and serve as a tool for biomarker validation and identification. Med 2023, 4, 290–310.e212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinhofer, I.; Braunholz, D.; Klinghammer, K. Preclinical models of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma for a basic understanding of cancer biology and its translation into efficient therapies. Cancers Head Neck 2020, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasoulas, J.; Srivastava, S.; Xu, X.; Tarasova, V.; Maniakas, A.; Karreth, F.A.; Amelio, A.L. Genetically engineered mouse models of head and neck cancers. Oncogene 2023, 42, 2593–2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dileto, C.L.; Travis, E.L. Fibroblast radiosensitivity in vitro and lung fibrosis in vivo: Comparison between a fibrosis-prone and fibrosis-resistant mouse strain. Radiat. Res. 1996, 146, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, M.L.; Graham, M.M.; Mahler, P.A.; Rasey, J.S. Use of steroids to suppress vascular response to radiation. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1987, 13, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacht, S.; Garzón, P. Effects of corticosteroids on connective tissue and fibroblasts. Adv. Steroid Biochem. Pharmacol. 1974, 4, 157–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, R.B.; TrailSmith, M.D.; Ryan, M.E.; Charette, M.F. Synergistic effects of dexamethasone on platelet-derived growth factor mitogenesis in vitro. Arch. Oral. Biol. 1992, 37, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, D.M.; Cohen, M.; Juliéron, M.; Marandas, P.; Janot, F.; Bourhis, J. Botulinum toxin for radiation-induced facial pain and trismus. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2008, 138, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiFrancesco, T.; Khanna, A.; Stubblefield, M.D. Clinical Evaluation and Management of Cancer Survivors with Radiation Fibrosis Syndrome. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 2020, 36, 150982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamstra, J.I.; Roodenburg, J.L.; Beurskens, C.H.; Reintsema, H.; Dijkstra, P.U. TheraBite exercises to treat trismus secondary to head and neck cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2013, 21, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barañano, C.F.; Rosenthal, E.L.; Morgan, B.A.; McColloch, N.L.; Magnuson, J.S. Dynasplint for the management of trismus after treatment of upper aerodigestive tract cancer: A retrospective study. Ear Nose Throat J. 2011, 90, 584–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrafon, C.S.; Matos, L.L.; Simões-Zenari, M.; Cernea, C.R.; Nemr, K. Speech-language therapy program for mouth opening in patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer undergoing adjuvant radiotherapy: A pilot study. Codas 2018, 30, e20160221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piraux, E.; Caty, G.; Aboubakar Nana, F.; Reychler, G. Effects of exercise therapy in cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy treatment: A narrative review. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120922657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bach, C.A.; Wagner, I.; Lachiver, X.; Baujat, B.; Chabolle, F. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of post-radiosurgical neck contracture in head and neck cancer: A novel approach. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2012, 129, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Shen, Q.; Wang, Y.; Lu, K.; Wang, Y.; Peng, Y. A randomized prospective study of rehabilitation therapy in the treatment of radiation-induced dysphagia and trismus. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2011, 187, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okunieff, P.; Augustine, E.; Hicks, J.E.; Cornelison, T.L.; Altemus, R.M.; Naydich, B.G.; Ding, I.; Huser, A.K.; Abraham, E.H.; Smith, J.J.; et al. Pentoxifylline in the Treatment of Radiation-Induced Fibrosis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 2207–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, B.; Duncan, M.R. Pentoxifylline inhibits normal human dermal fibroblast in vitro proliferation, collagen, glycosaminoglycan, and fibronectin production, and increases collagenase activity. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1989, 92, 605–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, B.; Wietzerbin, J.; Sanceau, J.; Merlin, G.; Duncan, M.R. Pentoxifylline inhibits certain constitutive and tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced activities of human normal dermal fibroblasts. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1992, 98, 706–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Berman, B.; Duncan, M.R. Pentoxifylline inhibits the proliferation of human fibroblasts derived from keloid, scleroderma and morphoea skin and their production of collagen, glycosaminoglycans and fibronectin. Br. J. Dermatol. 1990, 123, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanian, S.; Balla-Mekias, S.; Lefaix, J.L. Striking regression of chronic radiotherapy damage in a clinical trial of combined pentoxifylline and tocopherol. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999, 17, 3283–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, R.; El Wakeel, L.; Saad, A.S.; Kelany, M.; El-Hamamsy, M. Pentoxifylline and vitamin E reduce the severity of radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis and dysphagia in head and neck cancer patients: A randomized, controlled study. Med. Oncol. 2019, 37, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harpsø, M.; Andreassen, C.N.; Offersen, B.V. Pentoxifylline and vitamin E for treating radiation-induced fibrosis in breast and head and neck cancer patients. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2025, 201, 1044–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dion, M.W.; Hussey, D.H.; Doornbos, J.F.; Vigliotti, A.P.; Wen, B.C.; Anderson, B. Preliminary results of a pilot study of pentoxifylline in the treatment of late radiation soft tissue necrosis. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1990, 19, 401–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futran, N.D.; Trotti, A.; Gwede, C. Pentoxifylline in the Treatment of Radiation-Related Soft Tissue Injury: Preliminary Observations. Laryngoscope 1997, 107, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arqueros-Lemus, M.; Mariño-Recabarren, D.; Niklander, S.; Martínez-Flores, R.; Moraga, V. Pentoxifylline and tocopherol for the treatment of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws. A systematic review. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal 2023, 28, e293–e300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Fu, H.; He, J.; He, Y. Does radiation-induced fibrosis have an important role in pathophysiology of the osteoradionecrosis of jaw? Med. Hypotheses 2011, 77, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vujaskovic, Z.; Anscher, M.S.; Feng, Q.-F.; Rabbani, Z.N.; Amin, K.; Samulski, T.S.; Dewhirst, M.W.; Haroon, Z.A. Radiation-induced hypoxia may perpetuate late normal tissue injury. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2001, 50, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLeod, N.M.; Pratt, C.A.; Mellor, T.K.; Brennan, P.A. Pentoxifylline and tocopherol in the management of patients with osteoradionecrosis, the Portsmouth experience. Br. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 50, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanian, S.; Lefaix, J.L. Complete healing of severe osteoradionecrosis with treatment combining pentoxifylline, tocopherol and clodronate. Br. J. Radiol. 2002, 75, 467–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanian, S.; Depondt, J.; Lefaix, J.L. Major healing of refractory mandible osteoradionecrosis after treatment combining pentoxifylline and tocopherol: A phase II trial. Head Neck 2005, 27, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delanian, S.; Chatel, C.; Porcher, R.; Depondt, J.; Lefaix, J.L. Complete restoration of refractory mandibular osteoradionecrosis by prolonged treatment with a pentoxifylline-tocopherol-clodronate combination (PENTOCLO): A phase II trial. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2011, 80, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robard, L.; Louis, M.Y.; Blanchard, D.; Babin, E.; Delanian, S. Medical treatment of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible by PENTOCLO: Preliminary results. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2014, 131, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, M.; Pellecer, M.; Chung, E.; Sung, E. The efficacy of pentoxifylline/tocopherol combination in the treatment of osteoradionecrosis. Spec. Care Dent. 2015, 35, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, V.; Gadiwalla, Y.; Sassoon, I.; Sproat, C.; Kwok, J.; McGurk, M. Use of pentoxifylline and tocopherol in the management of osteoradionecrosis. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 54, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissard, A.; Dang, N.P.; Barthelemy, I.; Delbet, C.; Puechmaille, M.; Depeyre, A.; Pereira, B.; Martin, F.; Guillemin, F.; Biau, J.; et al. Efficacy of pentoxifylline-tocopherol-clodronate in mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, E559–E566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.; Patel, N.; Sassoon, I.; Patel, V. The use of pentoxifylline, tocopherol and clodronate in the management of osteoradionecrosis of the jaws. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 156, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravichandran, S.; Manickam, N.; Kandasamy, M. Liposome encapsulated clodronate mediated elimination of pathogenic macrophages and microglia: A promising pharmacological regime to defuse cytokine storm in COVID-19. Med. Drug Discov. 2022, 15, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.W.; Zhang, X.M.; Luo, H.M.; Fu, Y.C.; Xu, M.Y.; Tang, S.J. Clodronate liposomes reduce excessive scar formation in a mouse model of burn injury by reducing collagen deposition and TGF-β1 expression. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2014, 41, 2143–2149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloskey, E.; Paterson, A.H.; Powles, T.; Kanis, J.A. Clodronate. Bone 2021, 143, 115715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aygenc, E.; Celikkanat, S.; Kaymakci, M.; Aksaray, F.; Ozdem, C. Prophylactic effect of pentoxifylline on radiotherapy complications: A clinical study. Otolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2004, 130, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Gadiwalla, Y.; Sassoon, I.; Sproat, C.; Kwok, J.; McGurk, M. Prophylactic use of pentoxifylline and tocopherol in patients who require dental extractions after radiotherapy for cancer of the head and neck. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 54, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.R.; Fleck, J.F.; Diehl, A.; Barletta, D.; Braga-Filho, A.; Barletta, A.; Ilha, L. Protective effect of alpha-tocopherol in head and neck cancer radiation-induced mucositis: A double-blind randomized trial. Head Neck 2004, 26, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zeng, J.; Qi, F. The Effects and Mechanisms of Botulinum Toxin Type A on Hypertrophic Scars and Keloids. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2025; ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Lee, C.S.; Wu, J.; Koch, C.J.; Thom, S.R.; Maity, A.; Bernhard, E.J. Effects of hyperbaric oxygen exposure on experimental head and neck tumor growth, oxygenation, and vasculature. Head Neck 2005, 27, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velazquez, O.C. Angiogenesis and vasculogenesis: Inducing the growth of new blood vessels and wound healing by stimulation of bone marrow–derived progenitor cell mobilization and homing. J. Vasc. Surg. 2007, 45, A39–A47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, P.; Vaishnavi, D.; Gnanam, A.; Krishnakumar Raja, V.B. The role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the prevention and management of radiation-induced complications of the head and neck-a systematic review of literature. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 118, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipsen, B.B.; Korsholm, M.; Rohde, M.; Wessel, I.; Forner, L.; Johansen, J.; Godballe, C. The effect of hyperbaric oxygen therapy in head and neck cancer patients with radiation induced dysphagia—A systematic review. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 2594–2600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.C.; Bennett, M.H.; Hawkins, G.C.; Azzopardi, C.P.; Feldmeier, J.; Smee, R.; Milross, C. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for late radiation tissue injury. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 8, Cd005005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Sharma, V.; Pandey, S.; Pal, U.S. Radiation effects in head and neck and role of hyperbaric oxygen therapy: An adjunct to management. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 15, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.H.; Feldmeier, J.; Smee, R.; Milross, C. Hyperbaric oxygenation for tumour sensitisation to radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 4, Cd005007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonis, S.T. Superoxide Dismutase as an Intervention for Radiation Therapy-Associated Toxicities: Review and Profile of Avasopasem Manganese as a Treatment Option for Radiation-Induced Mucositis. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2021, 15, 1021–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Sarwar, T.; Khan, A.A.; Rahmani, A.H. Therapeutic Applications and Mechanisms of Superoxide Dismutase (SOD) in Different Pathogenesis. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeen, K.C.; Spanos, W.C.; Gromer, L. Topical superoxide dismutase in posttreatment fibrosis in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2018, 40, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C.M.; Lee, C.M.; Saunders, D.; Curtis, A.; Dunlap, N.; Nangia, C.S.; Lee, A.S.; Holmlund, J.; Brill, J.M.; Sonis, S.T.; et al. Results of a randomized, placebo (PBO) controlled, double-blind P2b trial of GC4419 (avisopasem manganese) to reduce duration, incidence and severity and delay onset of severe radiation-related oral mucositis (SOM) in patients (pts) with locally advanced squamous cell cancer of the oral cavity (OC) or oropharynx (OP). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, H.; Bensadoun, R.J. Trolamine emulsion for the prevention of radiation dermatitis in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Support. Care Cancer 2012, 20, 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haydont, V.r.; Bourgier, C.l.; Pocard, M.; Lusinchi, A.; Aigueperse, J.; Mathé, D.; Bourhis, J.; Vozenin-Brotons, M.-C. Pravastatin Inhibits the Rho/CCN2/Extracellular Matrix Cascade in Human Fibrosis Explants and Improves Radiation-Induced Intestinal Fibrosis in Rats. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 5331–5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgier, C.; Haydont, V.; Milliat, F.; François, A.; Holler, V.; Lasser, P.; Bourhis, J.; Mathé, D.; Vozenin-Brotons, M.C. Inhibition of Rho kinase modulates radiation induced fibrogenic phenotype in intestinal smooth muscle cells through alteration of the cytoskeleton and connective tissue growth factor expression. Gut 2005, 54, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgier, C.; Auperin, A.; Rivera, S.; Boisselier, P.; Petit, B.; Lang, P.; Lassau, N.; Taourel, P.; Tetreau, R.; Azria, D.; et al. Pravastatin Reverses Established Radiation-Induced Cutaneous and Subcutaneous Fibrosis in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer: Results of the Biology-Driven Phase 2 Clinical Trial Pravacur. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2019, 104, 365–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruwanpura, S.M.; Thomas, B.J.; Bardin, P.G. Pirfenidone: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Clinical Applications in Lung Disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, N.L.; Soule, B.P.; Gerber, L.; Augustine, E.; Smith, S.; Altemus, R.M.; Mitchell, J.B.; Camphausen, K.A. Oral Pirfenidone in patients with chronic fibrosis resulting from radiotherapy: A pilot study. Radiat. Oncol. 2007, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joannes, A.; Voisin, T.; Morzadec, C.; Letellier, A.; Gutierrez, F.L.; Chiforeanu, D.C.; Le Naoures, C.; Guillot, S.; De Latour, B.R.; Rouze, S.; et al. Anti-fibrotic effects of nintedanib on lung fibroblasts derived from patients with Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases (PF-ILDs). Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 83, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Liu, C.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Liang, H.; Yuan, X. Nintedanib Mitigates Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis by Suppressing Epithelial Cell Inflammatory Response and Inhibiting Fibroblast-to-Myofibroblast Transition. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2024, 20, 3353–3371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi, S.; Endo, M.; Fukuda, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Nakamura, M.; Okada, K.; Kawahara, M.; Akahane, K.; Nagatomo, T.; Onaga, R.; et al. Nintedanib-Induced Delayed Mucosal Healing after Adjuvant Radiation in a Case of Oropharyngeal Carcinoma. Case Rep. Oncol. 2022, 15, 776–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Huang, K.; Zhang, H.; Kim, E.; Kim, H.; Liu, Z.; Kim, C.Y.; Park, K.; Raza, M.A.; Kim, K.; et al. Imatinib inhibits oral squamous cell carcinoma by suppressing the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J. Cancer 2024, 15, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J.Y.; Glazer, T.; Iida, M.; Mehall, B.; Kostecki, K.L.; Yu, M.; Wieland, A.; Hartig, G.K.; McCulloch, T.M.; Trask, D.; et al. Imatinib plus Cetuximab as a Window of Opportunity Clinical Trial in Head and Neck Cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2024, 118, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, C.E.; Wilkes, M.C.; Edens, M.; Kottom, T.J.; Murphy, S.J.; Limper, A.H.; Leof, E.B. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2004, 114, 1308–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, J.A.; Chung, E.J.; Hudak, K.E.; Sowers, A.; Thetford, A.; White, A.O.; Mitchell, J.B.; Citrin, D.E. Inhibition of radiation-induced skin fibrosis with imatinib. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2013, 89, 162–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetshina, A.; Venalis, P.; Dees, C.; Busch, N.; Zwerina, J.; Schett, G.; Distler, O.; Distler, J.H. Treatment with imatinib prevents fibrosis in different preclinical models of systemic sclerosis and induces regression of established fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009, 60, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Abdollahi, A.; Gröne, H.J.; Lipson, K.E.; Belka, C.; Huber, P.E. Late treatment with imatinib mesylate ameliorates radiation-induced lung fibrosis in a mouse model. Radiat. Oncol. 2009, 4, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, L.M.; Padilla, C.M.; McLaughlin, S.R.; Mathes, A.; Ziemek, J.; Goummih, S.; Nakerakanti, S.; York, M.; Farina, G.; Whitfield, M.L.; et al. Fresolimumab treatment decreases biomarkers and improves clinical symptoms in systemic sclerosis patients. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 2795–2807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, M.; Lipson, K.E.; Akbarpour, M.; Fouse, S.; Kriegsmann, M.; Zhou, C.; Kriegsmann, K.; Weichert, W.; Seeley, T.W.; Kouchakji, E.; et al. Late Intervention with Radiation-Induced Lung Fibrosis-Comparing Pamrevlumab Anti-CTGF Therapy vs. Pirfenidone vs. Nintedanib as Mono-, Dual- and Triple-therapy Combinations. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2020, 108, S76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabeeb, D.; Musa, A.E.; Abd Ali, H.S.; Najafi, M. Curcumin Protects Against Radiotherapy-Induced Oxidative Injury to the Skin. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2020, 14, 3159–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan Wolf, J.; Heckler, C.E.; Guido, J.J.; Peoples, A.R.; Gewandter, J.S.; Ling, M.; Vinciguerra, V.P.; Anderson, T.; Evans, L.; Wade, J.; et al. Oral curcumin for radiation dermatitis: A URCC NCORP study of 686 breast cancer patients. Support. Care Cancer 2018, 26, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Liu, C.; Ma, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, R. Protective Effect and Mechanism of Action of Rosmarinic Acid on Radiation-Induced Parotid Gland Injury in Rats. Dose Response 2020, 18, 1559325820907782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonadou, D.; Pepelassi, M.; Synodinou, M.; Puglisi, M.; Throuvalas, N. Prophylactic use of amifostine to prevent radiochemotherapy-induced mucositis and xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2002, 52, 739–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukourakis, M.I.; Kyrias, G.; Kakolyris, S.; Kouroussis, C.; Frangiadaki, C.; Giatromanolaki, A.; Retalis, G.; Georgoulias, V. Subcutaneous administration of amifostine during fractionated radiotherapy: A randomized phase II study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 2226–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brizel, D.M.; Wasserman, T.H.; Henke, M.; Strnad, V.; Rudat, V.; Monnier, A.; Eschwege, F.; Zhang, J.; Russell, L.; Oster, W.; et al. Phase III randomized trial of amifostine as a radioprotector in head and neck cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2000, 18, 3339–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarhaddi, D.; Tchanque-Fossuo, C.N.; Poushanchi, B.; Donneys, A.; Deshpande, S.S.; Weiss, D.M.; Buchman, S.R. Amifostine protects vascularity and improves union in a model of irradiated mandibular fracture healing. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013, 132, 1542–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shao, L.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, W.; Ma, L.; Xu, T.; Chang, P.; Dong, L. Mesenchymal stromal cells can repair radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis via a DKK-1-mediated Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Tissue Res. 2021, 384, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Tong, Z. Mesenchymal Stem Cells in Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis: Future Prospects. Cells 2022, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blitzer, G.C.; Paz, C.; Glassey, A.; Ganz, O.R.; Giri, J.; Pennati, A.; Meyers, R.O.; Bates, A.M.; Nickel, K.P.; Weiss, M.; et al. Functionality of bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells derived from head and neck cancer patients-A FDA-IND enabling study regarding MSC-based treatments for radiation-induced xerostomia. Radiother. Oncol. 2024, 192, 110093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grønhøj, C.; Jensen, D.H.; Glovinski, P.V.; Jensen, S.B.; Bardow, A.; Oliveri, R.S.; Specht, L.; Thomsen, C.; Darkner, S.; Kiss, K.; et al. First-in-man mesenchymal stem cells for radiation-induced xerostomia (MESRIX): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casiraghi, F.; Remuzzi, G.; Abbate, M.; Perico, N. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell therapy and risk of malignancies. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2013, 9, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Kong, F.; Yuan, Y.; Seth, P.; Xu, W.; Wang, H.; Xiao, F.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; et al. Decorin-Modified Umbilical Cord Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSCs) Attenuate Radiation-Induced Lung Injuries via Regulating Inflammation, Fibrotic Factors, and Immune Responses. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2018, 101, 945–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenova, V.; Mladenov, E.; Stuschke, M.; Iliakis, G. DNA Damage Clustering after Ionizing Radiation and Consequences in the Processing of Chromatin Breaks. Molecules 2022, 27, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Fabbrizi, M.R.; Hughes, J.R.; Grundy, G.J.; Parsons, J.L. Effectiveness of PARP inhibition in enhancing the radiosensitivity of 3D spheroids of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 940377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mentzel, J.; Hildebrand, L.S.; Kuhlmann, L.; Fietkau, R.; Distel, L.V. Effective Radiosensitization of HNSCC Cell Lines by DNA-PKcs Inhibitor AZD7648 and PARP Inhibitors Talazoparib and Niraparib. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Liu, Q.; Fan, H.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Qin, B.; Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Hu, Y. STING facilitates the development of radiation-induced lung injury via regulating the PERK/eIF2alpha pathway. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2024, 13, 3010–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colangelo, N.W.; Gerber, N.K.; Vatner, R.E.; Cooper, B.T. Harnessing the cGAS-STING pathway to potentiate radiation therapy: Current approaches and future directions. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1383000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, A.; Loo, T.M.; Okada, R.; Kamachi, F.; Watanabe, Y.; Wakita, M.; Watanabe, S.; Kawamoto, S.; Miyata, K.; Barber, G.N.; et al. Downregulation of cytoplasmic DNases is implicated in cytoplasmic DNA accumulation and SASP in senescent cells. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Xiao, N.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, Z.; Fu, Y.; Huang, M.; Xu, S.; Chen, Q. Suppression of TREX1 deficiency-induced cellular senescence and interferonopathies by inhibition of DNA damage response. iScience 2023, 26, 107090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Thummuri, D.; Zheng, G.; Okunieff, P.; Citrin, D.E.; Vujaskovic, Z.; Zhou, D. Cellular senescence and radiation-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Transl. Res. 2019, 209, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanpouille-Box, C.; Alard, A.; Aryankalayil, M.J.; Sarfraz, Y.; Diamond, J.M.; Schneider, R.J.; Inghirami, G.; Coleman, C.N.; Formenti, S.C.; Demaria, S. DNA exonuclease Trex1 regulates radiotherapy-induced tumour immunogenicity. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, H.; Fang, M.; Hang, Q.Q.; Chen, Y.; Qian, X.; Chen, M. Pirfenidone modulates macrophage polarization and ameliorates radiation-induced lung fibrosis by inhibiting the TGF-β1/Smad3 pathway. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2021, 25, 8662–8675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, W.; Liu, B.; Yi, M.; Li, L.; Tang, Y.; Wu, B.; Yuan, X. Antifibrotic Agent Pirfenidone Protects against Development of Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis in a Murine Model. Radiat. Res. 2018, 190, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, I.; El Abiad, J.M.; James, A.W.; Levin, A.S.; Morris, C.D. Administration of TGF-ß Inhibitor Mitigates Radiation-induced Fibrosis in a Mouse Model. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2021, 479, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.J.; Yi, C.O.; Jeon, B.T.; Jeong, Y.Y.; Kang, G.M.; Lee, J.E.; Roh, G.S.; Lee, J.D. Curcumin attenuates radiation-induced inflammation and fibrosis in rat lungs. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2013, 17, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Ma, S.; Liu, C.; Hu, K.; Xu, M.; Wang, R. Rosmarinic Acid Prevents Radiation-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis Through Attenuation of ROS/MYPT1/TGFβ1 Signaling Via miR-19b-3p. Dose Response 2020, 18, 1559325820968413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Park, G.C.; Lee, H.-W.; Bang, S.-Y.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, W.-T.; Shin, S.-C.; Cheon, Y.-i.; Lee, B.-J. Amifostine and melatonin attenuate radiation-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrotic remodeling in the vocal folds and subglottic glands of rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 192, 118658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Zhuang, B.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W.; Jin, Y. Inhaled amifostine for the prevention of radiation-induced lung injury. Radiat. Med. Prot. 2022, 03, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujaskovic, Z.; Feng, Q.F.; Rabbani, Z.N.; Samulski, T.V.; Anscher, M.S.; Brizel, D.M. Assessment of the protective effect of amifostine on radiation-induced pulmonary toxicity. Exp. Lung Res. 2002, 28, 577–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, A.; Greenberger, J.S.; Rubin, P.J. Understanding the mechanism of radiation induced fibrosis and therapy options. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 204, 107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavigne, D.; Ng, S.P.; O’Sullivan, B.; Nguyen-Tan, P.F.; Filion, E.; Létourneau-Guillon, L.; Fuller, C.D.; Bahig, H. Magnetic Resonance-Guided Radiation Therapy for Head and Neck Cancers. Curr. Oncol. 2022, 29, 8302–8315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, S.L.; Heukelom, J.; McDonald, B.A.; Van Dijk, L.; Wahid, K.A.; Sanders, K.; Salzillo, T.C.; Hemmati, M.; Schaefer, A.; Fuller, C.D. MR-Guided Adaptive Radiotherapy for OAR Sparing in Head and Neck Cancers. Cancers 2022, 14, 1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, W.C.; Yoon, W.S.; Koom, W.S.; Rim, C.H. Reirradiation using stereotactic body radiotherapy in the management of recurrent or second primary head and neck cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Oral Oncol. 2020, 107, 104757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagodinsky, J.C.; Vera, J.M.; Jin, W.J.; Shea, A.G.; Clark, P.A.; Sriramaneni, R.N.; Havighurst, T.C.; Chakravarthy, I.; Allawi, R.H.; Kim, K.; et al. Intratumoral radiation dose heterogeneity augments antitumor immunity in mice and primes responses to checkpoint blockade. Sci. Transl. Med. 2024, 16, eadk0642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darragh, L.B.; Knitz, M.M.; Hu, J.; Clambey, E.T.; Backus, J.; Dumit, A.; Samedi, V.; Bubak, A.; Greene, C.; Waxweiler, T.; et al. A phase I/Ib trial and biological correlate analysis of neoadjuvant SBRT with single-dose durvalumab in HPV-unrelated locally advanced HNSCC. Nat. Cancer 2022, 3, 1300–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, S.; Sherman, E.; Tsai, C.J.; Baxi, S.; Aghalar, J.; Eng, J.; Zhi, W.I.; McFarland, D.; Michel, L.S.; Young, R.; et al. Randomized Phase II Trial of Nivolumab with Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy Versus Nivolumab Alone in Metastatic Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Youssef, I.; Yoon, J.; Mohamed, N.; Zakeri, K.; Press, R.H.; Chen, L.; Gelblum, D.Y.; McBride, S.M.; Tsai, C.J.; Riaz, N.; et al. Toxicity Profiles and Survival Outcomes Among Patients with Nonmetastatic Oropharyngeal Carcinoma Treated with Intensity-Modulated Proton Therapy vs Intensity-Modulated Radiation Therapy. JAMA Netw. Open 2022, 5, e2241538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, S.J.; Busse, P.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Hernandez, M.; Swanson, D.M.; Garden, A.S.; Sturgis, E.M.; Ferrarotto, R.; Gunn, G.B.; Patel, S.H.; et al. Phase III randomized trial of intensity-modulated proton therapy (IMPT) versus intensity-modulated photon therapy (IMRT) for the treatment of head and neck oropharyngeal carcinoma (OPC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42, 6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Muller, O.M.; Shiraishi, S.; Harper, M.; Amundson, A.C.; Wong, W.W.; McGee, L.A.; Rwigema, J.-C.M.; Schild, S.E.; Bues, M.; et al. Empirical Relative Biological Effectiveness (RBE) for Mandible Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) in Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated With Pencil-Beam-Scanning Proton Therapy (PBSPT): A Retrospective, Case-Matched Cohort Study. Front. Oncol. 2022, 12, 843175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dee, E.C.; Yang, F.; Singh, A.; Wu, Y.; Suggitt, J.; Treechairusame, T.; Polanco, E.S.; Zhang, Z.; Mah, D.; Lin, H.; et al. Osteoradionecrosis as a complication following intensity-modulated radiation therapy or proton therapy in the treatment of oropharyngeal carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 6066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowder, S.L.; Najam, N.; Sarma, K.P.; Fiese, B.H.; Arthur, A.E. Head and Neck Cancer Survivors’ Experiences with Chronic Nutrition Impact Symptom Burden after Radiation: A Qualitative Study. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2020, 120, 1643–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.M.; Sultana, N.; Liu, C.; Mao, A.; Katsube, T.; Wang, B. Impact of dietary ingredients on radioprotection and radiosensitization: A comprehensive review. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2396558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, J.; Su, Y.; Bai, H.; Kuang, H.; Li, C.; Zheng, X.; Liang, L.; Li, L.; Cheng, D.; Li, T. Nutritional management for late complications of radiotherapy. Holist. Integr. Oncol. 2024, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Beilman, B.; Gibbs, H.D.; Hamilton, J.L.; Parker, N.; Bur, A.M.; Caudell, J.J.; Gan, G.N.; Hamilton-Reeves, J.M.; Jim, H.S.L.; et al. Nutrition in head and neck cancer care: A roadmap and call for research. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, e300–e310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faverio, P.; Bocchino, M.; Caminati, A.; Fumagalli, A.; Gasbarra, M.; Iovino, P.; Petruzzi, A.; Scalfi, L.; Sebastiani, A.; Stanziola, A.A.; et al. Nutrition in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis: Critical Issues Analysis and Future Research Directions. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, D.; Ranjbar, G.; Rezvani, R.; Goshayeshi, L.; Razmpour, F.; Nematy, M. Dietary patterns in relation to hepatic fibrosis among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2019, 12, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seth, I.; Lim, B.; Cevik, J.; Gracias, D.; Chua, M.; Kenney, P.S.; Rozen, W.M.; Cuomo, R. Impact of nutrition on skin wound healing and aesthetic outcomes: A comprehensive narrative review. JPRAS Open 2024, 39, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Ji, K.; Zhang, M.; Huang, H.; Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Q. NMN alleviates radiation-induced intestinal fibrosis by modulating gut microbiota. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2023, 99, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Acute | Chronic |

|---|---|

| Mucositis | Xerostomia |

| Dysgeusia | Trismus |

| Voice changes | Odynophagia |

| Dysphagia | Osteoradionecrosis |

| Lymphedema | Pharyngoesophageal stenosis |

| Dermatitis | Fibrosis |

| Parotitis | Thyroid dysfunction |

| Periodontitis | |

| Dental caries | |

| Radiation-associated neoplasms | |

| Musculoskeletal loss of function or range of motion |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muehlebach, M.E.; Pradeep, S.; Chen, X.; Arnold, L.; Arthur, A.E.; Gan, G.N.; Thomas, S.M. Radiation-Induced Fibrosis (RIF) in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC): A Review. Cells 2025, 14, 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241969

Muehlebach ME, Pradeep S, Chen X, Arnold L, Arthur AE, Gan GN, Thomas SM. Radiation-Induced Fibrosis (RIF) in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC): A Review. Cells. 2025; 14(24):1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241969

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuehlebach, Molly E., Sidharth Pradeep, Xin Chen, Levi Arnold, Anna E. Arthur, Gregory N. Gan, and Sufi Mary Thomas. 2025. "Radiation-Induced Fibrosis (RIF) in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC): A Review" Cells 14, no. 24: 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241969

APA StyleMuehlebach, M. E., Pradeep, S., Chen, X., Arnold, L., Arthur, A. E., Gan, G. N., & Thomas, S. M. (2025). Radiation-Induced Fibrosis (RIF) in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC): A Review. Cells, 14(24), 1969. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14241969