Abstract

The aim of the study was to investigate the early response of apple fruit infected with Penicillium expansum (P. expansum) to blue light-emitting diode (LED) light (BLL) irradiation. To focus our study on the interaction between apple fruit, the pathogen, and BLL, the effect of BLL was also studied on apples without P. expansum and P. expansum grown on malt extract agar (MEA). Transcriptome analysis revealed that the most pronounced responses among biological processes were observed in inoculated apples under BLL. The upregulated processes included water transport, response to heat, and response to high light intensity. The defence response of apples was enhanced by the upregulation of thaumatin-like proteins and caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase, while the cellular response to phosphate deficiency and the regulation of multicellular organism development were downregulated. In P. expansum grown on apples under BLL, transcriptome analysis revealed downregulation of genes related to signalling, response to organic compounds, and regulation of metabolic and biosynthetic processes, while genes involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites were upregulated. In addition, the expression of patulin cluster genes was predominantly downregulated in P. expansum. The significant upregulation of genes related to cryptochrome inhibition, defence response, and caffeic acid metabolism in apples under BLL, together with the reduced virulence of P. expansum, contributes to the inhibition of fungal growth.

1. Introduction

Total post-harvest losses of apples range from 5 and 35% in industrialized countries but can reach up to 50% in developing countries [1]. The greatest losses are caused by fungal diseases; the most important fungal pathogens include Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium expansum, Mucor piriformis, and Monilinia sp. [2]. Contamination of apples with mycotoxins produced by these fungal pathogens represents a significant concern for food security and human health [3,4]. Fungal diseases of apples are controlled by fungicides, which are environmentally controversial and may be hazardous to human health. To reduce the application of fungicides, good agricultural practice recommends improved utilization of solar radiation by placing reflective foils [5] or coloured shade in orchards [6]. Exposure of fruits to light significantly affects fruit development in both the pre-harvest post-harvest phases. Post-harvest treatments might be considered as environmental stresses for apples and some studies have evaluated their effect [7,8]. Different types of irradiation (i.e., ultraviolet-B (UV-B) LED light), low temperature, wound stress, and nutrient deficiency are environmental factors that influence anthocyanin biosynthesis via the phenylpropanoid pathway [9].

Various studies have identified the mechanisms of light-induced pigmentation in apples by altering the expression of transcription factors that regulate the expression of genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis pathways [10]. Vimolmangkang et al. (2014) identified 19 categories of genes with the highest number in primary metabolism (17%) and transcription (12%) after apples were exposed to 14 h of light treatment (daylight) [11].

Recently, various modulators and their genes have been identified along with some post-translational modifications (MdMYB1 and MdWRKY40 modulate the expression of anthocyanin biosynthetic genes, i.e., with upregulation after apple wounding). Hu et al. (2020) investigated the effects of UV-B irradiation on apple tissue (72 h) and found that genes encoding enzymes and transcription factors involved in the anthocyanin synthesis pathway (MdANS, MdDFR, MdUFGT, and MdMYB1) were more highly expressed in MdWRKY72-overexpressing transgenic calli than in the wild-type ‘Orin’ apple calli [12]. A similar response was also observed by Ding et al. (2021), who identified changes in the content of 178 metabolites in green apples exposed to UV-B light, and altered the expression of various genes, including 475 genes encoding transcription factors [13]. P. expansum is well known post-harvest pathogen on apples that requires a wound or natural opening for infection [14]. P. expansum modifies its environment at the infection site and infects the host by employing different strategies, such as the production of cell wall-degrading enzymes (CWDEs) [15], modifying pH, which in turn enhances its virulence by enhancing effectors and CWDE activity [16,17], the secretion of proteases, production of patulin [18], infection related transcription factors [19], and lysin motif (LysM) effectors [20].

Various studies have investigated P. expansum infection of apples at the transcriptomic level to identify the genes involved in its pathogenesis. Wang et al. (2019) investigated the early phases of P. expansum infection on apples (0, 1, 3 and 6 hours post-inoculation—hpi) [21]. They found that P. expansum exhibits changes in the expression of genes related to cell wall degradation, anti-oxidative stress, pH regulation, and effectors, while in apple tissue, pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP)-triggered immunity was activated at 1 hpi and was followed by effector-triggered immunity at 3 hpi. Transcriptomic analysis of the interaction between P. expansum and apples during infection revealed three major groups of genes in apple tissue involved in pH regulation and apple colonization, with upregulation of the jasmonic acid and mevalonate pathways and also downregulation of the glycogen and starch biosynthesis pathways [17].

Studies show that post-harvest irradiation of apples with BLL at 444 nm increases the content of antioxidants, especially anthocyanins and quercetin glycosides [22]. The content of certain phenolic compounds, such as phloridzin, quercetin, epicatechin, and procyanidins B1 and B2, could play a role in the resistance of apples to P. expansum infections [23].

Additionally, BLL with a wavelength of 460 nm inhibited the growth of P. expansum and reduced patulin production by inducing plasma membrane dysfunction and oxidative stress in P. expansum [8]. Similarly, Yamaga et al. (2015) observed reduced symptoms of P. italicum infection in mandarin fruits due to exposure to BLL [24]. Moreover, they indicated that BLL might induce apple defence and immune responses, leading to higher resistance to fungal inoculation, while simultaneously reducing the virulence of P. expansum.

However, the interaction between BLL and the inoculation of apples with P. expansum is not well understood from either the apple or fungal perspective. There is also a scarcity of studies elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying such interactions. In our study, we investigated how BLL and inoculation with P. expansum affect the response of apples, and how P. expansum responds to BLL when grown on apples or on malt extract agar (MEA).

To achieve these objectives, we compared artificially wounded apples irradiated with BLL with artificially wounded apples kept in the dark (comparison 1), apples inoculated with P. expansum and irradiated with BLL with apples inoculated with P. expansum and kept in the dark (comparison 2), and P. expansum grown in vitro under BLL with P. expansum grown in vitro in the dark (comparison 3). We assumed that under BLL, there would be a better defence response of apple fruit to P. expansum infection, while simultaneously reducing the pathogenicity of P. expansum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

To fully investigate the interactions between the pathogen P. expansum CBS 281.97, and the host Malus domestica cv. ‘Idared’ under BLL irradiation, the following comparisons were studied (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of comparisons made to fully investigate the interactions between the pathogen P. expansum CBS 281.97 and the host Malus domestica cv. ‘Idared’ under BLL irradiation. Created in BioRender. Mahnic, N. (2026) https://BioRender.com/nio5i2d (accessed on 16 January 2026).

- Artificially wounded apple irradiated with BLL vs. artificially wounded apple in the dark (comparison 1).

- Apple inoculated with P. expansum irradiated with BLL vs. apple inoculated with P. expansum in the dark (comparison 2).

- P. expansum grown in vitro under BLL vs. P. expansum grown in vitro in the dark (comparison 3).

2.2. Apple Inoculation and Irradiation

Apple fruits (M. domestica cv. Idared) were harvested in technological maturity in central Slovenia (46°13′27.012″ N 15°11′9.168″ E). Undamaged apples were soaked in 0.2% NaOCl (Kemika, Zagreb, Croatia) for 2 min, then thoroughly rinsed with distilled water, and dried with a paper towel. The inoculum was prepared from a 7-day-old culture of Penicillium expansum CBS 281.97 (Westerdijk institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands) grown on MEA (malt extract agar; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) by gently scraping the surface of the mould with a sterile loop to collect the conidia that were transferred to a physiological solution containing 0.05% Tween 80 (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The suspension was filtered through 8 layers of sterile gauze, and the conidia concentration was adjusted to 1 × 108 mL−1 using a haemocytometer. An x-shaped wound (approx. 2 × 2 mm) was made with a sterile scalpel six times on the same fruit and 10 µL of inoculum was added to each wound. The inoculum was left to dry on the apples and then the inoculated fruits were incubated at 25 °C for 9 h. Half of the inoculated apples (4) were incubated under constant irradiation with blue LED light (BLL, 445 nm, 11.4 µmol/m2 s; H2A1-H450; Roithner Lasertechnik, Vienna, Austria), which is comparable to the mean solar irradiation at the Earth’s surface (45° north latitude) at 450 nm, and the other half of the inoculated apples (4) were incubated in the dark as controls. In parallel, wounded apples without inoculum and P. expansum on MEA were prepared and incubated in the same conditions as the inoculated apples.

2.3. Sampling

After a 9 h incubation at 25 °C, a circular cut (d = 15 mm) was made around the wound/inoculation site, and discs of apple fruit tissue approximately 2 mm thick were peeled off. The discs were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Each sample contained 12 discs pooled from 2 apples. Sampling at 9 hpi was chosen to obtain transcriptional changes associated with mycelium growth of P. expansum in apple tissue, corresponding to initial hyphal penetration into the host tissue.

P. expansum colonies on MEA were sampled using a plunger and 4 fungal discs were collected from the same medium for each sample and were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until analysis. All experiments were repeated twice.

2.4. RNA Isolation and Quantification

The effects of irradiation and inoculation with P. expansum on apples, as well as the effects of irradiation and medium (apple or MEA) on P. expansum, were analyzed at the transcriptomic level for each organism studied. The control groups consisted of treatments conducted in dark conditions. Total RNA was isolated from the apple skin of the inoculated and artificially wounded apples of both groups, i.e., apples that were irradiated and those that were kept in the dark (control group). Similarly, total RNA was also isolated from fungi grown on apples or MEA that were irradiated or kept in the dark. Total RNA isolation was performed using the GenElute™ RNA/DNA/Protein Purification Kit (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quantification and integrity (RNA quality) of the total RNA were determined using an Agilent™ 2100 Bioanalyzer Instrument and Agilent™ RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Total RNA was enriched for polyadenylated (polyA) mRNA using NEXTflex Poly(A) Beads 2.0 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

2.5. Library Preparation and Sequencing

For next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), transcriptome libraries were constructed using an Ion Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Briefly, an appropriate amount of polyA RNA was enzymatically fragmented for 20 s and purified. The yield and size distribution were assessed with an Agilent™ 2100 Bioanalyzer Instrument and Agilent™ RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). This was followed by the hybridisation and ligation of adapters to the fragmented mRNA and reverse transcription. Prepared cDNA fragments were purified using magnetic beads, followed by barcoding of each sample using an Ion Xpress™ RNA-Seq Barcode 1–16 Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and PCR amplification. Barcoded cDNA libraries were purified, and yield and size distribution of libraries were assessed using an Agilent™ 2100 Bioanalyzer™ instrument with the Agilent™ DNA 1000 Kit or the Agilent™ High Sensitivity DNA Kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Prepared cDNA libraries were diluted to the same molar concentrations and pooled in equal volumes. Afterwards, the pooled sample was prepared for sequencing using an Ion OneTouch 2 system and Ion PI Hi-Q OT2 200 Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the accompanying manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed on an Ion Proton system, using the Ion PI Hi-Q sequencing 200 Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/; accessed on 16 January 2026) under BioProject accession number PRJNA1359740.

2.6. Data Analysis

The bioinformatics analysis was performed using a CLC Genomics Workbench and a CLC Genomics server (version 21.0.4) (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Firstly, quality control of the sequencing reads and trimming of the adapter sequences were performed using the “Trim Reads” tool. Afterwards, using the RNA-Seq Analysis tool (version 2.4), reads were mapped against reference genomes of Malus domestica ASM211411v1 (RefSeq: GCF_002114115.1) and Penicillium expansum ASM76974v1 (RefSeq: GCF_000769745.1) with annotated genes and transcripts, respectively. Obtained mapping files were used in the differential expression analysis using the tool “Differential Expression for RNA-Seq” (version 2.6). For M. domestica, we tested the effect of BLL irradiation on artificially wounded apples. This was obtained by comparing artificially wounded apples irradiated with BLL to artificially wounded apples kept in the dark (comparison 1; Figure 1). Furthermore, we determined the effect of BLL on P. expansum-inoculated apples by comparing P. expansum-inoculated apples irradiated with BLL to P. expansum-inoculated apples kept in the dark (comparison 2; Figure 1). The latter samples are the same as for comparison 2 in apples, but gene expression levels were obtained by mapping sequencing reads against the reference genome of P. expansum, as described above. Then we determined the effect of BLL on the fungus alone by comparing the fungus grown on MEA irradiated with BLL and the fungus grown on MEA kept in the dark (comparison 3; Figure 1).

Venn diagram analyses were performed to determine common DEGs within each organism. Specifically, common DEGs from comparison 1 and comparison 2 in apples, and comparison 2 and 3 in P. expansum, were visualized separately.

Afterwards, the expression of common apple DEGs was derived as the difference between the log2 fold change values (ΔLFC) of comparison 1 (artificially wounded apple) and those of comparison 2 (inoculated apple). For common P. expansum DEGs, the expression was derived as the difference between the LFC values (ΔLFC) of comparison 3 (P. expansum on MEA) and those of comparison 2 (P. expansum on apple). In both cases, the difference was considered significant if the absolute value was ≥2.

Genes with at least an absolute log2 fold change (|LFC|) of ≥1 and an FDR p-value of ≤0.05 were considered differentially expressed. Functional enrichment analysis was conducted with TopGO (GO terms with weighted a Fisher p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered significant).

3. Results

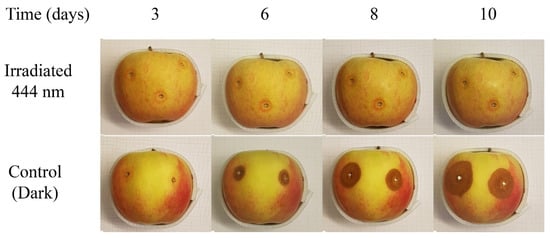

The inhibitory effect of blue LED light (BLL) on the growth of P. expansum on apples was confirmed by preliminary results (Figure 2), where apples cv ‘Idared’ were inoculated with P. expansum and either irradiated with BLL or incubated in the dark for 10 days [25]. To investigate the inhibitory effect of BLL on the colonization of apple fruit with P. expansum at the molecular level, an RNA-Seq approach was used.

Figure 2.

Inhibitory effect of blue LED light (BLL) on P. expansum growth on apple fruit during 10-day storage [25].

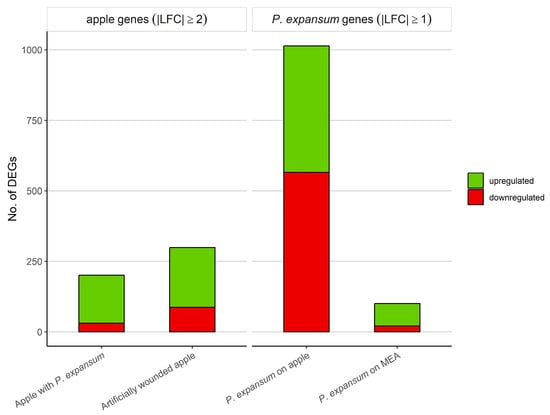

For apples, genes with |LFC| ≥ 2 and a false discovery rate (FDR) p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered differentially expressed. In comparison 1, in which we determined the effect of BLL on control apples (not inoculated), we identified 299 DEGs, of which 212 were upregulated and 87 were downregulated (Table S1). In comparison 2, in which we determined the effect of BLL on inoculated apples, we observed altered expression in 201 apple genes, of which 31 DEGs were downregulated and 170 DEGs were upregulated (Table S3; Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in apple and P. expansum after 9 h irradiation with blue LED light compared to respective controls incubated in the dark. Differential expression was considered with false discovery rate (FDR) p-value of ≤0.05.

Due to the low number of P. expansum DEGs, especially in comparison 3 (P. expansum on MEA), genes with |LFC| ≥ 1 and an FDR p-value of ≤0.05 were considered differentially expressed. In P. expansum growing on apples (comparison 2), we identified altered expression in 1014 genes due to BLL irradiation, of which 448 were upregulated and 566 were downregulated (Table S5). In contrast, a significantly lower number of genes (101 genes) was identified to be differentially expressed in the fungus growing on MEA due to BLL exposure (comparison 3). In P. expansum growing on MEA exposed to BLL, we determined 80 upregulated and 21 downregulated genes (Table S7; Figure 3).

The results of the functional analysis will be presented separately from both perspectives: the host (M. domestica) and the pathogen (P. expansum).

3.1. Functional Enrichment Analysis of Apple Differentially Expressed Genes

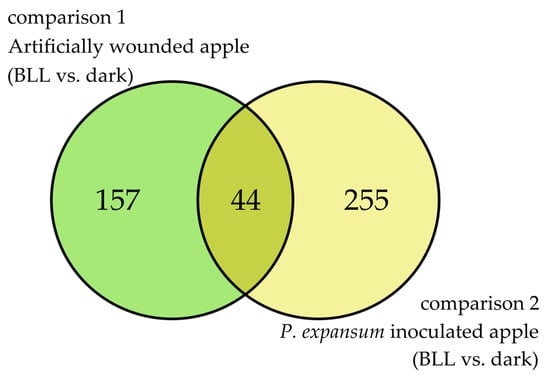

Host DEGs from comparisons 1 and 2 were combined as a Venn diagram (Figure 4) to identify common DEGs due to BLL irradiation of the host only (comparison 1) or with the presence of the pathogen (comparison 2).

Figure 4.

Venn diagram showing the number of common and specific DEGs (|LFC| ≥ 2) due to blue LED light in wounded apples (comparison 1) and apples inoculated with P. expansum (comparison 2).

The Venn diagram shows 157 unique DEGs from comparison 1 (artificially wounded apple; BLL vs. dark), 255 unique DEGs from comparison 2 (inoculated apple; BLL vs. dark), and 44 common DEGs.

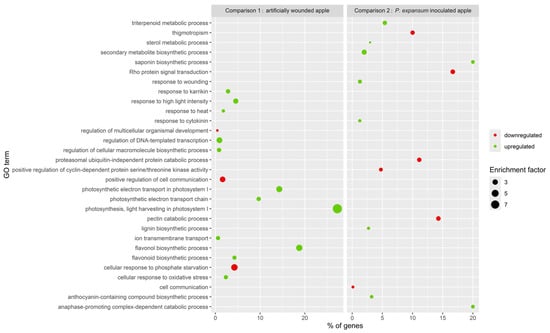

Separate functional enrichment analyses were conducted on specific DEGs from artificially wounded apples (comparison 1) and P. expansum-inoculated apples (comparison 2) exposed to BLL (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Bubble plot representing the first 15 significantly enriched GO terms as response of BLL treatment from apple DEGs from comparisons 1 (apple) and 2 (apple + P. expansum).

In the response of apples to BLL, we identified a total of 84 enriched GO terms of biological processes, 43 downregulated and 41 upregulated (Table S2). Figure 5 presents the fifteen most altered processes, of which upregulated biological processes were involved in the regulation of DNA-templated transcription (regulation of macromolecule biosynthetic process), water transport, response to heat, response to high light intensity, photosynthesis—light harvesting in photosystem I (photosynthetic electron transport chain and photosynthetic electron transport in photosystem I)—regulation of stomatal movement, response to UV-B, monoatomic ion transmembrane transport, cellular response to oxidative stress, cell redox homeostasis, flavonol biosynthetic process (flavonoid biosynthetic process), and response to karrikin. The downregulated processes included the cellular response to phosphate starvation, regulation of multicellular organismal development, positive regulation of cell communication, and cell surface receptor protein serine/threonine kinase signalling pathway.

In comparison 2 (inoculated apples), we identified 24 upregulated and 12 downregulated significantly enriched biological processes (Table S4). We observed upregulated processes related to secondary metabolite biosynthetic processes (anthocyanin-containing compound biosynthetic process), lignin biosynthetic processes, response to wounding (response to cytokinin), and the triterpenoid metabolic process (sterol metabolic process). Most biological processes involved in cell communication were shown to be downregulated.

The expression of common DEGs was determined by subtracting the LFC values of comparison 1 (artificially wounded apple) from those of comparison 2 (inoculated apple). The difference (ΔLFC) was considered significant if |ΔLFC| ≥ 2. Among the 44 DEGs common in both comparisons, a significant LFC difference (|ΔLFC| ≥ 2) was found in the 8 DEGs presented in Table 1. With this approach, we identified genes that, although common to both comparisons, are still expressed differently and demonstrate the effect of BLL and P. expansum infection on the host. Gene LOC103452045, which was upregulated under both conditions but significantly more in comparison 2, encodes the BIC1-like protein, a blue light inhibitor of cryptochromes 1. Two genes (LOC103411735 and LOC103429376) that code for thaumatin-like proteins and are involved in defence response (GO:0006952) were strongly upregulated in the presence of P. expansum under BLL [26], while they were downregulated in the case without the pathogen. Similarly, two other genes LOC103410332 and LOC103408513 coding for caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase and hydrophobic protein RCI2A, respectively, showed strong upregulation under BLL in the presence of the pathogen, while they were strongly downregulated in the case without the pathogen. The gene LOC114823345, which codes for large ribosomal subunit protein eL20z-like, showed the largest difference in expression between conditions and was downregulated in both cases, significantly more in the case without the pathogen. Two genes showed relative downregulation in the presence of P. expansum, LOC103440276 and LOC103409391, both coding for aldehyde oxidase GLOX1-like, and LOC103409391 coding for Vacuoleless Gametophytes-like protein.

Table 1.

Common apple DEGs from comparisons 1 (artificially wounded apple) and 2 (inoculated apple) that were considered significantly different (|ΔLFC| ≥ 2), including protein name and respective GO—biological process.

3.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis of P. expansum Differentially Expressed Genes

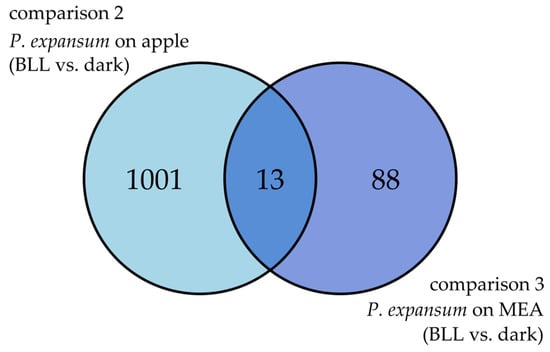

Similarly, as for the apple, combining the pathogen genes from comparisons 2 and 3 as a Venn diagram was performed to identify common and specific pathogen DEGs in response to BLL while growing on apple fruits (comparison 2) or on MEA (comparison 3) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Venn diagram representing common and specific P. expansum DEGs (|LFC| ≥ 1) due to BLL from P. expansum grown on apple (comparison 2) and P. expansum grown on MEA (comparison 3).

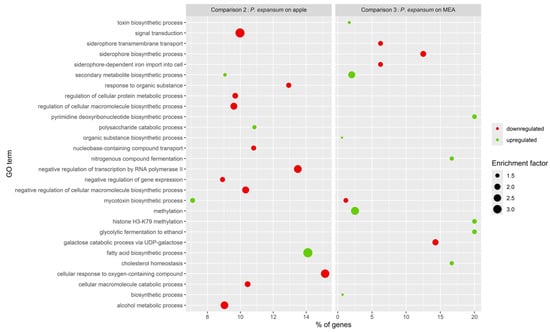

Functional enrichment analysis was conducted on specific DEGs from comparisons 2 and 3 (Figure 7) to determine specific effect of BLL on P. expansum growing on different mediums.

Figure 7.

Bubble plot representing the first 15 significantly enriched GO terms in response to BLL treatment from P. expansum DEGs from P. expansum grown on apple (comparison 2) and P. expansum grown on MEA (comparison 3).

Gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed on the sets of unique DEGs from comparisons 2 and 3 (Figure 7). In response to P. expansum grown on apples exposed to BLL compared to P. expansum grown on apples kept in the dark (comparison 2), we identified 79 enriched biological processes, of which 50 were downregulated and 29 were upregulated (Table S6). However, in response to BLL, P. expansum grown on MEA (comparison 3) showed 26 enriched biological processes, of which 5 were downregulated and 21 were upregulated (Table S8). In response to BLL irradiation, P. expansum exhibited condition-specific enrichment of GO biological process terms, as shown in the bubble plot comparing samples grown on apples (P. expansum on apple) and on MEA (P. expansum on MEA). We identified a higher number of downregulated biological processes when P. expansum was exposed to BLL and grown on apples (50 biological processes) compared to samples from MEA, the former showing downregulation of genes involved in signal transduction, response to organic substances, regulation of metabolic and biosynthetic processes, and negative regulation of transcription. Enriched terms among the upregulated genes included the secondary metabolite biosynthetic process, which was also upregulated in P. expansum grown on MEA and exposed to BLL, and the mycotoxin biosynthetic process, for which we observed downregulation in P. expansum exposed to BLL and grown on MEA. In P. expansum exposed to BLL while growing on MEA (comparison 3), we identified that most of the upregulated genes are involved in enriched biological processes related to methylation, fermentation, and cholesterol homeostasis, and downregulated genes are involved in the enriched processes of siderophore transport and biosynthesis.

Of the genes common to both comparisons, those with expression value differences greater than 2 or less than −2 were considered significant. In total, nine genes showed differential expression between P. expansum on MEA and P. expansum on apple under BLL versus dark conditions (Table 2). Among these, five genes (PEX2_012080, PEX2_059990, PEX2_080210, PEX2_020710, and PEX2_076110) were upregulated in P. expansum when grown on an apple and downregulated in P. expansum alone, with positive differences in LFC values between the samples ranging from 2.24 to 4.84. These genes encode the following products: putative NAD-dependent epimerase/dehydratase, a major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter, cellulase, an oxoglutarate/iron-dependent dioxygenase, and a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase. Four genes (PEX2_044620, PEX2_035410, PEX2_032800, and PEX2_099230) showed the opposite pattern, with higher expression in P. expansum grown on MEA and lower expression when grown on apples, resulting in negative values of the difference in LFC ranging from −2.94 to −6.08. These genes encode an alcohol dehydrogenase protein, a DUF1774 domain-containing protein, an uncharacterized protein, and a bZIP domain-containing protein. Gene ontology annotations linked the upregulated cellulase (PEX2_080210) to the cellulose catabolic process (GO:0030245) and the dioxygenase (PEX2_020710) to mycotoxin biosynthesis (GO:0043386) and related biosynthetic processes. The uncharacterized gene PEX2_032800 was associated with methylation (GO:0032259).

Table 2.

Common P. expansum DEGs from comparisons 2 (P. expansum on apple) and 3 (P. expansum on MEA) that were considered significantly different (|ΔLFC| ≥ 2), including protein name and respective GO—biological process.

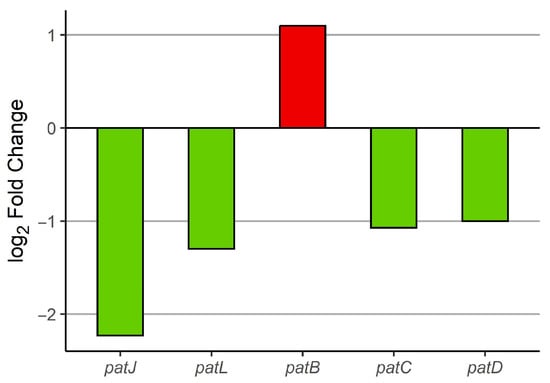

During the investigation of the irradiation effect of BLL on the expression of genes from the patulin cluster (patA–patO) in P. expansum grown on apples (comparison 2), we found five genes from the patulin cluster to be differentially expressed (Figure 8). Only one of these genes (patB) was upregulated, while the rest among them (patJ, patL, patC, and patD) were downregulated. This finding indicates reduced pathogenicity of P. expansum on apples with respect to patulin biosynthesis as a consequence of BLL irradiation. There was no statistical difference in the expression of genes from the patulin cluster in comparison 3 (Table S9). The inference of reduced patulin production is indirect, based on transcriptomic data rather than chemical quantification.

Figure 8.

Differential expression of P. expansum patulin cluster genes from comparison 2 (apple + P. expansum); green—downregulated, red—upregulated; FDR p-value ≤ 0.05.

4. Discussion

In the response of apples to BLL, we identified 201 differentially expressed genes enriched in 84 biological processes. The highest percentage of DEGs are involved in the upregulation of biological processes related to photosynthesis and the biosynthesis of flavonol and flavonoids. Excess and fluctuating light result in photoinhibition and reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation around photosystems II and I, respectively [27]. From a metabolomic perspective, it has significant effects on phenylpropanoid metabolism, specifically on the accumulation of phenols, especially anthocyanins and quercetin derivatives [22].

Similarly, P. expansum-inoculated apples exposed to BLL show enriched and upregulated secondary metabolite, saponin, and anthocyanin-containing compound biosynthetic processes, as well as triterpene metabolic processes; this additionally indicates the additive defence response of apples against BLL and fungal infection, as saponins are known to affect fungal cell membranes [28], which might lead to higher susceptibility to BLL [29]. Additionally, the pectin catabolic process is shown to be downregulated, and the lignin biosynthetic process is upregulated. These two processes were represented by lower expression of pectinesterase QRT1—LOC103448431, and higher expression of caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferas (COMT)—LOC103410332, respectively. Caffeic acid O-methyltransferase catalyzes the last step of melatonin synthesis in plants and reportedly participates in the regulation of stress response and tolerance [30]. In relation to light, blue light at 445 nm has been shown to upregulate COMT and other phenylpropanoid genes, leading to lignin accumulation in pear stone cells [31]. More importantly, blue light was the most efficient in promoting COMT expression compared to white or red light [31]. COMT catalyzes the methylation of caffeic acid at C3’-OH to produce ferulic acid. Exogenous caffeic acid applied as a dip treatment inhibited the growth of P. expansum in ‘Qiujin’ apples [30] and promoted the synthesis of endogenous caffeic acid.

Moreover, exogenous melatonin induces resistance against P. expansum in ‘Golden Delicious’ apples [31]. This indicates enhanced cell wall integrity in treated apples, thus preventing its additional degradation, which might be caused by P. expansum and consequent infection [32]. The latter also supports our observation of altered gene expression in P. expansum grown on apples exposed to BLL, where we determined the enrichment and upregulation of the polysaccharide catabolic process (Figure 5). We observed upregulated expression of gene glycoside hydrolase, family 61 (PEX2_080210; LFC 2.25), which has been reported to be involved in the cellulose catabolic process and belongs to the glycoside hydrolase protein family that acts on glucose polysaccharides found in the cell walls or on pectin [33]. Additionally, we determined upregulation of oxoglutarate/iron-dependent dioxygenase (PEX2_020710), which has been reported to be involved in the oxidation of organic substrates and can be indirectly involved in the catalysis of pectin during colonization [17].

Among the genes shared between BLL-irradiated apples, P. expansum-inoculated apples, and BLL-irradiated wounded apples, we observed upregulation of LOC103452045, which codes for BIC1-like protein. Blue-light inhibitor of cryptochromes 1 (BIC1) is a brassinazole-resistant 1 (BZR1) interacting protein. It functions as a transcriptional coactivator for BZR1, affecting plant growth [34], especially hypocotyl length [35]. The induction of mRNA expression of the BIC1 and BIC2 genes in Arabidopsis by blue light correlates positively with exposure time and light intensity [35]. These proteins are known transcriptional coactivators that promote brassinosteroid signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana [34] and this signalling can indirectly induce disease resistance and reduce the decay of jujube fruit infected by P. expansum [36].

The gene that codes for the large ribosomal subunit protein eL20z-like, showed significant downregulation in P. expansum-inoculated apples exposed to BLL, but even lower expression in artificially wounded apples exposed to BLL. Although their main role is in mediating protein synthesis, new studies show that most ribosomal large subunits show upregulation in response to cold and phytohormones, and downregulation in response to heat and H2O2 treatments. Additionally, 80% of them are upregulated in the leaves of rice infected with the bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae [37]. Some studies also attribute indirect antimicrobial activity to ribosomal proteins through an increase in ROS production, which in turn affects a pathogen’s membrane integrity and leads to cell death [38]. In addition to ROS production, BLL also directly changes cell membrane integrity, mycelium morphology, and provokes mitochondrial membrane destruction and mitochondrial dysfunction of P. expansum [8].

Furthermore, we observe upregulation and enrichment of the defence response (GO:0006952) represented by thaumatin-like protein 1a (TLP1a) and 1b (TLP1b) in inoculated and irradiated apples, while these proteins show low expression in artificially wounded apples irradiated with BLL. This indicates strong antifungal response, as TLPs are plant host defence proteins that belong to pathogenesis-related family 5 (PR-5), and growing evidence has demonstrated their involvement in resistance to various fungal diseases in many crop plants, particularly legumes [39]. In in vitro studies, TLPs isolated from bananas significantly inhibited P. expansum in a wide pH range [40]. The antifungal protein induced permeabilization and disruption of the P. expansum membrane [40].

In both treatments, namely inoculated and irradiated samples and wounded and irradiated samples, we observed upregulation of aldehyde oxidase GLOX1-like. These proteins have a role in the biosynthesis of phytohormones, stress response, and are also responsible for oxidizing aldehydes to carboxylic acids, thus maintaining reactive oxygen species homeostasis and increasing stress tolerance [41].

Exposure of P. expansum to BLL on MEA caused transcriptional changes affecting both primary and secondary metabolism. The highest percentage of upregulated DEGs were involved in various biosynthetic processes, including glycolytic fermentation to ethanol, nitrogenous compound fermentation, and the pyrimidine deoxyribonucleotide biosynthetic process. This might reflect the consumption of nitrogenous compounds, primarily amino acids and ammonium, by fungi grown on MEA and a possible stress-induced biosynthesis [42]. Upregulation of genes linked to methylation and secondary metabolite biosynthesis indicates that P. expansum responds to BLL by reprogramming regulatory networks and activating stress-protective pathways [43,44]. Epigenetic mechanisms, such as methylation, often mediated by the LaeA and velvet family of regulatory proteins, play a leading role in coordinating secondary metabolism and adaptation to environmental signals [44]. BLL also enhanced the expression of genes involved in fermentation and nucleotide biosynthesis, suggesting a metabolic shift towards energy generation and DNA maintenance under stress. Such changes may reflect reduced dependence on respiration and increased demand for nucleotides to repair light-induced damage [45].

Conversely, the strongest downregulation was observed for genes related to mycotoxin biosynthesis, siderophore production, and galactose catabolism. Downregulation of toxin biosynthetic clusters supports previous reports that light can suppress fungal virulence factors [46,47]. Reduced siderophore activity may further impair iron acquisition and competitiveness [48], while decreased galactose utilization points to resource reallocation towards central metabolism [49]. Overall, BLL as an environmental stressor enhanced pathways that support survival while suppressing virulence-associated traits, highlighting its potential to reduce the pathogenicity and toxigenicity of P. expansum.

When P. expansum was inoculated on apple fruit and irradiated with BLL, its transcriptional response differed markedly from that on MEA. That was expected, as apple fruit and MEA differ substantially in nutrient content and other intrinsic factors (i.e., pH value). The strongest downregulated DEGs were linked to signal transduction, oxidative stress responses, alcohol metabolism, transcriptional regulation, and macromolecule biosynthesis, indicating a general inhibition of growth and stress responses [43,48].

In contrast, the most upregulated DEGs were involved in fatty acid biosynthesis, polysaccharide catabolism, and secondary metabolites, including mycotoxin biosynthesis. The induction of lipid metabolism likely reflects membrane remodelling and stress protection [44,46], while the activation of polysaccharide degradation points to host tissue utilization [49]. Unlike on MEA, secondary metabolism was induced, suggesting that host-derived signals can override light-mediated repression, consistent with fungal transcriptional plasticity and previous reports of host-modulated transcriptional responses during early apple infection [21,45,49,50].

It is evident that BLL in the presence of P. expansum significantly increases the upregulation of genes associated with the following proteins: protein BIC1-like, thaumatin-like protein 1a precursor, thaumatin-like protein 1b, caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase, hydrophobic protein RCI2A, and a large ribosomal subunit protein eL20z-like. In contrast, genes associated with aldehyde oxidase GLOX1-like and uncharacterized protein LOC103409391 isoform X1 were downregulated under the same conditions. Apparently, BLL plays a significant role in the early response of apples inoculated with P. expansum.

Analysis of the patulin biosynthetic cluster (patA–patO) revealed a more specific effect: only patB was upregulated, while patJ, patL, patC, and patD were downregulated. Thus, despite global activation of secondary metabolism, patulin biosynthesis was suppressed, implying reduced pathogenic potential of P. expansum under BLL. This agrees with reports that light can repress cluster-specific regulators [43,46]. PatL, a cluster-specific transcription factor and positive regulator, was downregulated under BLL, likely suppressing the overall patulin biosynthetic pathway despite the upregulation of patB, which participates in early precursor metabolism [51]. Global regulators, such as the pH-responsive transcription factor patC and the velvet complex component LaeA, further integrate environmental signals with secondary metabolism, contributing to the observed suppression of patulin production under BLL [19]. No significant changes were observed on MEA, indicating that both host cues and light are required to shift patulin regulation, in line with previous observations of early host-driven transcriptional modulation of patulin genes and invasion mechanisms [21,50,52].

BLL’s effect on P. expansum is highly dependent on the host context. In the hostile apple environment—characterized by oxidative stress, antimicrobial compounds, and nutrient limitation—BLL synergises with host defences to suppress fungal attack and fitness. On MAE, BLL may even stimulate fungal metabolism. This suggests that BLL does not directly kill the fungus but instead amplifies host-imposed stresses, creating an inhospitable environment where the pathogen cannot effectively deploy its virulence strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study has shown that the apple defence mechanism is triggered within 9 h after inoculation with P. expansum and BLL irradiation. The apple defence mechanisms include the expression of genes involved in water transport, response to heat, response to high light intensity, and the upregulation of thaumatin-like proteins and caffeic acid 3-O-methyltransferase. Downregulated processes include the response to phosphate deficiency and the regulation of multicellular organism development.

In P. expansum, genes related to signalling, response to organic compounds, and the regulation of metabolic and biosynthetic processes were downregulated under BLL irradiation, while genes involved in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites were upregulated. However, BLL irradiation led to the downregulation of four patulin-related genes.

Future prospects for this study include proteomic and metabolomic approaches for both apples and P. expansum, as well as validation of the results using a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and quantification of patulin content in samples. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the effects of BLL is important for the development and optimization of practical applications of BLL in the food industry, including—but not limited to—refrigeration systems for fruit storage.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy16020246/s1, Table S1: Differentially expressed apple genes from comparison 1 (artificially wounded apple BLL vs. dark); |LFC| ≥ 2; FDR p-value ≤ 0.05; Table S2: GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed apple genes from comparison 1 (artificially wounded apple BLL vs. dark); weighted Fisher p-value ≤ 0.05; Table S3: Differentially expressed apple genes from comparison 2 (P. expansum inoculated apple BLL vs. dark); |LFC| ≥ 2; FDR p-value ≤ 0.05; Table S4: GO analysis of differentially expressed apple genes from comparison 2 (P. expansum inoculated apple BLL vs. dark); weighted Fisher p-value ≤ 0.05; Table S5: Differentially expressed P. expansum genes from comparison 2 (P. expansum on apple BLL vs. dark); |LFC| ≥ 1; FDR p-value ≤ 0.05; Table S6: GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed P. expansum genes from comparison 2 (P. expansum on apple BLL vs. dark); weighted Fisher p-value ≤ 0.05; Table S7: Differentially expressed P. expansum genes from comparison 3 (P. expansum on MEA BLL vs. dark); |LFC| ≥ 1; FDR p-value ≤ 0.05; Table S8: GO enrichment analysis of differentially expressed P. expansum genes from comparison 3 (P. expansum on MEA BLL vs. dark); weighted Fisher p-value ≤ 0.05; Table S9: Expression of P. expansum patulin cluster genes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.M., R.V. and B.J.; methodology, N.M., U.K., J.J., N.T., S.K., R.V. and B.J.; validation, N.T. and S.K.; formal analysis, N.M., U.K., N.T. and S.K.; investigation, N.M., U.K., N.T., S.K., R.V. and B.J.; resources, N.M., U.K., J.J., N.T., S.K., M.B.K., R.V. and B.J.; data curation, N.M., U.K. and J.J.; writing—original draft preparation, N.M., U.K., R.V. and B.J.; writing—review and editing, N.M., U.K., J.J., N.T., S.K., M.B.K., R.V. and B.J.; visualization, N.M. and U.K.; supervision, R.V. and B.J.; project administration, N.M., R.V. and B.J.; funding acquisition, J.J., N.T. and R.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/; accessed on 16 January 2026) under BioProject accession number PRJNA1359740.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the financial support from the Slovene Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS, program groups P4-0116, P4-0234 and P4-0077).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Natasa Toplak and Simon Koren were employed by the company Omega d.o.o., and Urban Kunej was employed by the company Jafral d.o.o. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BLL | blue LED light |

| LFC | log2 fold change |

| MEA | malt extract agar |

| DEG | differentially expressed gene |

| GO | gene ontology |

| dH2O | distilled water |

| qPCR | quantitative polymerase chain reaction |

References

- Porat, R.; Lichter, A.; Terry, L.A.; Harker, R.; Buzby, J. Postharvest losses of fruit and vegetables during retail and in consumers’ homes: Quantifications, causes, and means of prevention. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 139, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikram, A.; Prithiviraj, B.; Hamzehzarghani, H.; Kushalappa, A. Volatile metabolite profiling to discriminate diseases of McIntosh apple inoculated with fungal pathogens. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2004, 84, 1333–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, S. Pathogenicity assay of Penicillium expansum on apple fruits. Bio-Protocol 2017, 7, e2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannous, J.; Atoui, A.; El Khoury, A.; Francis, Z.; Oswald, I.P.; Puel, O.; Lteif, R. A study on the physicochemical parameters for Penicillium expansum growth and patulin production: Effect of temperature, pH, and water activity. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 4, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smrke, T.; Persic, M.; Veberic, R.; Sircelj, H.; Jakopic, J. Influence of reflective foil on persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) fruit peel colour and selected bioactive compounds. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupambi, G.; Anthony, B.M.; Layne, D.R.; Musacchi, S.; Serra, S.; Schmidt, T.; Kalcsits, L.A. The influence of protective netting on tree physiology and fruit quality of apple: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 236, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Shan, J.; Mao, X.; Zhang, Z.; Hong, W.; Wang, W.; Zhao, C.; Lin, H.; Zhu, R. Transcriptomic investigation reveals a potential mechanism of white LED irradiation inhibiting the growth and pathogenicity of the blue mold pathogen Penicillium expansum. Food Microbiol. 2025, 132, 104857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Wang, W.; Luo, Z.; Lin, H.; Li, Y.; Lu, W.; Xu, Z.; Cai, C.; Hu, S. Blue LED light treatment inhibits virulence and patulin biosynthesis in Penicillium expansum. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 200, 112340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.P.; Zhang, X.W.; You, C.X.; Bi, S.Q.; Wang, X.F.; Hao, Y.J. Md WRKY 40 promotes wounding-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in association with Md MYB 1 and undergoes Md BT 2-mediated degradation. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 380–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espley, R.V.; Hellens, R.P.; Putterill, J.; Stevenson, D.E.; Kutty-Amma, S.; Allan, A.C. Red colouration in apple fruit is due to the activity of the MYB transcription factor, MdMYB10. Plant J. 2007, 49, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vimolmangkang, S.; Zheng, D.; Han, Y.; Khan, M.A.; Soria-Guerra, R.E.; Korban, S.S. Transcriptome analysis of the exocarp of apple fruit identifies light-induced genes involved in red color pigmentation. Gene 2014, 534, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Fang, H.; Wang, J.; Yue, X.; Su, M.; Mao, Z.; Zou, Q.; Jiang, H.; Guo, Z.; Yu, L. Ultraviolet B-induced MdWRKY72 expression promotes anthocyanin synthesis in apple. Plant Sci. 2020, 292, 110377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, R.; Che, X.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, Y. Metabolome and transcriptome profiling provide insights into green apple peel reveals light-and UV-B-responsive pathway in anthocyanins accumulation. BMC Plant Biol. 2021, 21, 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luciano-Rosario, D.; Keller, N.P.; Jurick, W.M. Penicillium expansum: Biology, omics, and management tools for a global postharvest pathogen causing blue mould of pome fruit. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21, 1391–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadal, M.; Garcia-Pedrajas, M.D.; Gold, S.E. The snf1 gene of Ustilago maydis acts as a dual regulator of cell wall degrading enzymes. Phytopathology 2010, 100, 1364–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Torres, P.; Vilanova, L.; Ballester, A.R.; López-Pérez, M.; Teixidó, N.; Viñas, I.; Usall, J.; González-Candelas, L.; Torres, R. Unravelling the contribution of the Penicillium expansum PeSte12 transcription factor to virulence during apple fruit infection. Food Microbiol. 2018, 69, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barad, S.; Sela, N.; Kumar, D.; Kumar-Dubey, A.; Glam-Matana, N.; Sherman, A.; Prusky, D. Fungal and host transcriptome analysis of pH-regulated genes during colonization of apple fruits by Penicillium expansum. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snini, S.P.; Tannous, J.; Heuillard, P.; Bailly, S.; Lippi, Y.; Zehraoui, E.; Barreau, C.; Oswald, I.P.; Puel, O. Patulin is a cultivar-dependent aggressiveness factor favouring the colonization of apples by Penicillium expansum. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2016, 17, 920–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, B.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tian, S. The pH-responsive PacC transcription factor plays pivotal roles in virulence and patulin biosynthesis in Penicillium expansum. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 20, 4063–4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, E.; Ballester, A.R.; Raphael, G.; Feigenberg, O.; Liu, Y.; Norelli, J.; Gonzalez-Candelas, L.; Ma, J.; Dardick, C.; Wisniewski, M. Identification and characterization of LysM effectors in Penicillium expansum. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Yang, Q.; Boateng, N.A.S.; Ahima, J.; Liu, J.; Zhang, H. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of the Interaction between Penicillium expansum and Apple Fruit (Malus pumila Mill.) during Early Stages of Infection. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokalj, D.; Zlatić, E.; Cigić, B.; Kobav, M.B.; Vidrih, R. Postharvest flavonol and anthocyanin accumulation in three apple cultivars in response to blue-light-emitting diode light. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 257, 108711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gotal Skoko, A.-M.; Skendrović Babojelić, M.; Šarkanj, B.; Flanjak, I.; Tomac, I.; Jozinović, A.; Babić, J.; Šubarić, D.; Sulyok, M.; Krska, R. Influence of Polyphenols on the Resistance of Traditional and Conventional Apple Varieties to Infection by Penicillium expansum during Cold Storage. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaga, I.; Takahashi, T.; Ishii, K.; Kato, M.; Kobayashi, Y. Suppression of blue mold symptom development in satsuma mandarin fruits treated by low-intensity blue LED irradiation. Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2015, 21, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnič, N.; Kunej, U.; Jamnik, P.; Vidrih, R.; Jakše, J.; Koren, S.; Toplak, N.; Jeršek, B. Transcriptomic response of Penicillium expansum to LED blue light irradiation. In Proceedings of the Genetika 2022, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 28–30 September 2022; Genetic Society of Slovenia: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Medrano, R.; Jimenez-Moraila, B.; Herrera-Estrella, L.; Rivera-Bustamante, R.F. Nucleotide sequence of an osmotin-like cDNA induced in tomato during viroid infection. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992, 20, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeber, V.M.; Bajaj, I.; Rohde, M.; Schmülling, T.; Cortleven, A. Environment, Light acts as a stressor and influences abiotic and biotic stress responses in plants. Plant Cell 2021, 44, 645–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, V.; Morrissey, J.P.; Latijnhouwers, M.; Csukai, M.; Cleaver, A.; Yarrow, C.; Osbourn, A. Dual effects of plant steroidal alkaloids on Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2732–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escaray, F.J.; Felipo-Benavent, A.; Antonelli, C.J.; Balaguer, B.; Lopez-Gresa, M.P.; Vera, P. Plant triterpenoid saponins function as susceptibility factors to promote the pathogenicity of Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant 2024, 17, 1073–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Li, C.; Guo, M.; Liu, J.; Qu, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ge, Y. Caffeic acid enhances storage ability of apple fruit by regulating fatty acid metabolism. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2022, 192, 112012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Gong, X.; Xie, Z.; Qi, K.; Yuan, K.; Jiao, Y.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, S.; Shiratake, K.; Tao, S. Cryptochrome-mediated blue-light signal contributes to lignin biosynthesis in stone cells in pear fruit. Plant Sci. 2022, 318, 111211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miedes, E.; Lorences, E.P. Changes in cell wall pectin and pectinase activity in apple and tomato fruits during Penicillium expansum infection. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1359–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.A.; Fincher, G.B. (1, 3; 1, 4)-β-d-glucans in cell walls of the Poaceae, lower plants, and fungi: A tale of two linkages. Mol. Plant 2009, 2, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yan, B.; Dong, H.; He, G.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, J. BIC 1 acts as a transcriptional coactivator to promote brassinosteroid signaling and plant growth. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Han, Y.J.; Liu, Q.; Gu, L.; Yang, Z.; Su, J.; Liu, B.; Zuo, Z.; He, W. A CRY–BIC negative-feedback circuitry regulating blue light sensitivity of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2017, 92, 426–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, G.; Tian, S. Effects of brassinosteroids on postharvest disease and senescence of jujube fruit in storage. Pstharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 56, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moin, M.; Bakshi, A.; Saha, A.; Dutta, M.; Madhav, S.M.; Kirti, P. Rice ribosomal protein large subunit genes and their spatio-temporal and stress regulation. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurtado-Rios, J.J.; Carrasco-Navarro, U.; Almanza-Pérez, J.C.; Ponce-Alquicira, E. Ribosomes: The new role of ribosomal proteins as natural antimicrobials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Wei, S.; Li, Y. Thaumatin-like proteins in legumes: Functions and potential applications—A review. Plants 2024, 13, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, W.; Li, X.; Zhao, H.; Cao, J.; Jiang, W. Antifungal activity of an abundant thaumatin-like protein from banana against Penicillium expansum, and its possible mechanisms of action. Molecules 2018, 23, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Kamanga, B.M.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Y.; Xu, L. Research progress of aldehyde oxidases in plants. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, D.; Bi, Y.; Zong, Y.; Li, Y.; Sionov, E.; Prusky, D. Dynamic change of carbon and nitrogen sources in colonized apples by Penicillium expansum. Foods 2022, 11, 3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brakhage, A.A. Regulation of fungal secondary metabolism. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayram, Ö.; Braus, G.H. Coordination of secondarymetabolism and development in fungi: The velvet family of regulatory proteins. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purschwitz, J.; Müller, S.; Kastner, C.; Fischer, R. Seeing the rainbow: Light sensing in fungi. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2006, 9, 566–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Heydt, M.; Rüfer, C.; Raupp, F.; Bruchmann, A.; Perrone, G.; Geisen, R. Influence of light on food relevant fungi with emphasis on ochratoxin producing species. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011, 145, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priesterjahn, E.-M.; Geisen, R.; Schmidt-Heydt, M. Influence of light and water activity on growth and mycotoxin formation of selected isolates of Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, H. Fungal siderophore metabolism with a focus on Aspergillus fumigatus. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1266–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Assis, L.J.; Silva, L.P.; Bayram, O.; Dowling, P.; Kniemeyer, O.; Krüger, T.; Brakhage, A.A.; Chen, Y.; Dong, L.; Tan, K. Carbon catabolite repression in filamentous fungi is regulated by phosphorylation of the transcription factor CreA. mBio 2021, 12, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y.; Dhanasekaran, S.; Ngea, G.L.N.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, L.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H. Transcriptome analysis provides insights into potential mechanisms of epsilon-poly-L-lysine inhibiting Penicillium expansum invading apples. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2024, 207, 112622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, A.R.; Norelli, J.; Burchard, E.; Abdelfattah, A.; Levin, E.; Gonzalez-Candelas, L.; Droby, S.; Wisniewski, M. Transcriptomic Response of Resistant (PI613981-Malus sieversii) and Susceptible (“Royal Gala”) Genotypes of Apple to Blue Mold (Penicillium expansum) Infection. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, H.; Sun, T.; Ge, Y. Melatonin induces resistance against Penicillium expansum in apple fruit through enhancing phenylpropanoid metabolism. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2023, 127, 102082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.