Abstract

Protein phosphatase 2Cs (PP2Cs) constitute a widespread family of signaling regulators in plants and play central roles in abscisic acid (ABA)-mediated stress signaling; however, the PP2C gene family has not yet been systematically identified and characterized in pea (Pisum sativum), a salt-sensitive legume crop. In this study, we identified 89 PsPP2C genes based on domain features and sequence homology. These genes are unevenly distributed across seven chromosomes and classified into ten subfamilies, providing a comparative framework for evaluating structural and regulatory diversification within the PsPP2C family. The encoded proteins vary substantially in length, physicochemical properties, and predicted subcellular localization, while most members contain the conserved PP2Cc catalytic domain. Intra- and interspecies homology analyses identified 19 duplicated gene pairs in pea and numerous orthologous relationships with several model plants; all reliable gene pairs exhibited Ka/Ks < 1, indicating pervasive purifying selection. PsPP2C genes also showed broad variation in exon number and intron phase, and their promoter regions contained diverse light-, hormone-, and stress-related cis-elements with heterogeneous positional patterns. Expression profiling across 11 tissues revealed pronounced tissue-specific differences, with generally higher transcript abundance in roots and seeds than in other tissues. Under salt treatment, approximately 20% of PsPP2C genes displayed concentration- or time-dependent transcriptional changes. Among them, PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82—both belonging to the clade A PP2C subfamily—exhibited the most pronounced induction under high salinity and at early stress stages. Functional annotation indicated that these two genes are involved in ABA-related processes, including regulation of abscisic acid-activated signaling pathway, plant hormone signal transduction, and MAPK signaling pathway-plant. Collectively, this study provides a systematic characterization of the PsPP2C gene family, including its structural features, evolutionary patterns, and transcriptional responses to salt stress, thereby establishing a foundation for future functional investigations.

1. Introduction

Protein phosphorylation and dephosphorylation are among the most important and conserved post-translational modifications in cellular signal transduction, playing key roles in regulating cellular metabolism, gene expression, and environmental responses [1]. These processes are jointly mediated by protein kinases (PKs) and protein phosphatases (PPs). Among them, protein phosphatase 2C (PP2C) represents a Mn2+/Mg2+-dependent metal phosphatase family that is evolutionarily conserved across eukaryotes [2]. The PP2C gene family in plants is typically large and diverse. For instance, 76 PP2C genes have been identified in Arabidopsis thaliana and classified into ten subfamilies (A–J) [3], 132 members have been reported in rice (Oryza sativa) [4]. In addition, 87–181 homologs have been identified across different cultivars of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum) [5], 178 in peanut (Arachis hypogaea) [6], and 102 in maize (Zea mays) [7]. Generally, PP2C proteins contain a highly conserved catalytic domain at the C-terminus, whereas the N-terminal region varies greatly and may include transmembrane domains or signaling-related motifs [8,9], conferring functional specificity in various physiological processes.

Extensive studies have demonstrated that PP2C protein phosphatases play crucial roles in regulating plant growth, development, and diverse signaling pathways, including abscisic acid (ABA) signaling, abiotic stress responses, cell division, and plant immunity. In ABA signaling, ZmPP2C-A10 in maize has been identified as a negative regulator of drought tolerance [10], while transgenic studies in A. thaliana have shown that overexpression of AtPP2CF1 promotes inflorescence stem growth by stimulating cell proliferation and expansion, thereby increasing biomass production [11]. In rice, most members of the clade A PP2C subfamily are strongly induced by various abiotic stresses, highlighting their central role in stress adaptation, particularly under salt stress conditions [12]. Moreover, OsPP65 regulates plant responses to abiotic stress through independent modulation of the ABA and jasmonic acid (JA) pathways, and its knockdown enhances tolerance to osmotic and salt stresses [13]. Under salt stress, AtPP2CG1 in A. thaliana is markedly upregulated and positively regulates salt tolerance in an ABA-dependent manner [14]. Similarly, in rice, the ABA-responsive RING-type E3 ubiquitin ligase OsRF1 promotes the ubiquitination and degradation of the clade A member OsPP2C09, thereby enhancing salt tolerance [15]. These studies reveal that PP2C family members play essential and multifaceted roles in strengthening plant tolerance to abiotic stresses, especially salinity.

Soil salinization, exacerbated by global climate change, has become one of the major environmental threats to sustainable agriculture. Drought and seawater intrusion lead to excessive salt accumulation in soils, severely restricting water and nutrient uptake by plants and ultimately reducing crop productivity [16,17]. At the physiological level, excessively high soil salinity can induce osmotic stress and ion toxicity, thereby triggering a series of stress responses [18,19,20,21,22,23]. Pea (Pisum sativum) is an important cool-season legume crop with high protein content, low fat, and excellent nitrogen fixation capacity, widely used for food, feed, and green manure production [24,25,26]. However, pea is notably sensitive to salt stress, and salinity substantially reduces germination, biomass accumulation, water uptake and overall plant vigor [27,28], making salinity a major agronomic limitation for pea production. Despite this vulnerability, the regulatory components underlying salt-stress signaling in pea remain insufficiently characterized, particularly the PP2C family, which regulates multiple stress-related pathways in other plant species [4,7,14,15]. Unlike protein kinases or transcription factors that often act downstream in stress-response cascades, clade A PP2Cs occupy a central upstream position in ABA signaling by directly interacting with and inhibiting SnRK2 kinases under non-stress conditions [29,30]. Upon salt or osmotic stress, relief of PP2C-mediated repression allows rapid activation of SnRK2s and downstream transcriptional responses [31,32]. In this context, PP2Cs function as molecular switches that tightly couple stress perception with signal transduction, such that changes in their expression or activity can profoundly reshape salt-responsive signaling outputs. Accordingly, a systematic analysis of PsPP2C genes is required to establish a comprehensive genomic framework and to identify candidate members potentially involved in salt-stress responses in pea.

In this study, we aimed to systematically identify the PP2C gene family in pea and uncover which PsPP2C members may regulate the plant’s salt-responsive signaling pathway. By integrating genome-wide identification, phylogenetic analysis, and expression profiling under salt stress conditions, we identified candidate PP2C genes that are transcriptionally responsive to salinity and may function as key regulators in the ABA-mediated stress response network in pea. Notably, expression profiling across different tissues and under varying salt stress conditions revealed distinct transcriptional patterns, with PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 showing the strongest and most consistent induction. These genes were highlighted as representative early-responding PP2C members in pea. Their reproducible activation under saline conditions suggests they may serve as critical entry points for dissecting ABA-associated stress signaling pathways in pea, which remain poorly defined. This study provides new insights into the molecular mechanisms of salt tolerance and contributes to the potential improvement of salt tolerance in legume crops.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Identification and Physicochemical Characterization of the PsPP2C Gene Family in Pea

The reference genome of Pea used in this study was obtained from the LuTianWan8 cultivar, which was independently assembled by our research group (unpublished data).

For mung bean (Vigna radiata) [33] and soybean (Glycine max) [34], genome assemblies previously published by our group were used. The genome sequences of A. thaliana and rice were retrieved from the Phytozome database (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/, accessed on 1 November 2025).

To reliably identify bona fide members of the PsPP2C gene family, we employed a stringent dual-validation workflow combining domain-based the hidden Markov model (HMM) search and homology-based BLAST (v1.4.0) filtering. First, HMM profile of the PP2C catalytic domain (Pfam ID: PF00481) was retrieved from the Pfam database [35]. Using HMMER (v3.4) (http://hmmer.org/download.html, accessed on 1 November 2025) with the trusted cutoff parameter (-cut_tc), we scanned the pea proteome to ensure that only proteins carrying a complete and statistically well-supported PP2C catalytic core were retained. In parallel, we performed an all-vs-all BLASTP search using 76 well-characterized A. thaliana PP2C proteins as queries against the pea protein dataset, with an E-value threshold of 1 × 10−5. To increase the confidence of homology assignments, BLAST hits were further filtered to keep only sequences showing ≥30% amino-acid identity to known A. thaliana PP2Cs. The intersection of the curated HMMER (-cut_tc) hits and the filtered BLASTP results was defined as the set of PsPP2C candidates. To avoid redundancy and the inclusion of incomplete isoforms, only the longest transcript was retained for each locus during the final curation step.

The chromosomal locations of the genes were determined based on the pea genome annotation file and visualized using TBtools-II (v2.375) [36].

The physicochemical properties of all predicted PsPP2C proteins, including molecular weight, theoretical isoelectric point (pI), instability index, aliphatic index, and grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), were calculated using the TBtools-II [36]. The subcellular localization of each PsPP2C protein was predicted using the WoLF PSORT online tool (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/, accessed on 1 November 2025).

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Subfamily Classification of PsPP2C Proteins

Multiple sequence alignment was performed between P. sativum (PsPP2C) proteins and the well-characterized A. thaliana PP2C (AtPP2C) proteins using MUSCLE (v5.3) [37]. The A. thaliana PP2C protein sequences were obtained from the A. thaliana Information Resource (TAIR) database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/browse/gene_family/PP2C, accessed on 1 November 2025). Based on the established AtPP2C subfamily classification and sequence similarity analysis, the identified PsPP2C proteins were assigned to corresponding subfamilies.

The resulting protein sequences were aligned, and poorly aligned positions were trimmed using trimAL (v1.5.1) [38] with parameters -gt 0.6 -cons 60 to generate a high-confidence alignment in PHYLIP format. A maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was then constructed using IQ-TREE (3.0.1) [39] with automatic model selection (-m MFP), 1000 ultrafast bootstrap replicates (-bb 1000), 1000 SH-aLRT replicates (-alrt 1000), and BNNI optimization. The phylogenetic tree was visualized and annotated in the Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) platform [40], with distinct colors and branch styles representing different PP2C subfamilies.

2.3. Intra-Species and Inter-Species Homology Analysis and Evolutionary Characterization of the PsPP2C Gene Family

For intraspecific synteny, all-vs-all BLASTP was performed with E-value ≤ 1 × 10−5 and “-max_target_seqs 5”. MCScanX (v1.0.0) [41] was then run with default parameters, requiring at least five collinear genes per syntenic block (−s 5). Synteny was visualized using Circos (v0.52) [42].

For interspecific synteny (pea vs. soybean, mung bean, A. thaliana, and rice), the JCVI toolkit (v1.0.11) [43] was used. This pipeline performs all-vs-all BLASTP followed by collinearity detection and applies an internal c-score ≥ 0.7 filter (effectively reciprocal best hits after density filtering). Syntenic blocks were further screened with “-minspan = 30 -simple” to retain only robust blocks. Orthologous and paralogous gene pairs were extracted exclusively from these high-confidence syntenic blocks. Sequence extraction and filtering were performed with SeqKit (v2.4.0) [44].

Homologous gene pairs were subjected to codon-based multiple sequence alignments using ParaAT (v2.0) [45], which aligns protein sequences with MUSCLE (v5.3) [37] and subsequently back-translates them to the corresponding nucleotide sequences. The resulting codon alignments were used to estimate nonsynonymous substitution rates (Ka), synonymous substitution rates (Ks), and Ka/Ks ratios with KaKs_Calculator (v2.0) [46] under the default YN model. Gene pairs yielding unreliable estimates were removed.

2.4. Conserved Motif, Domain, Gene Structure, and Promoter Analysis

Conserved motifs of PsPP2C proteins were identified using MEME (4.12.0) [47], with the maximum number of motifs set to 10 and motif widths ranging from 6 to 200 amino acids. To further characterize conserved protein domains, Batch CD-Search [48] was employed with default parameters. Gene structure visualization, including exon–intron organization, was performed using TBtools-II [36] based on the pea genome annotation file.

For each PsPP2C gene, the transcription start site (TSS) was defined using the longest annotated transcript from the pea reference genome. The 2000 bp region upstream of the TSS was extracted with SeqKit (v2.10.1) [44] and used as the putative promoter sequence. Cis-acting regulatory elements were identified using the PlantCARE database (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 1 November 2025) [49]. The positional distribution of cis-elements along promoter regions was visualized using TBtools-II [36].

2.5. Tissue-Specific Expression and Salt Stress-Responsive Analysis of PsPP2C Genes

To investigate the spatial expression profiles of PsPP2C genes, publicly available RNA-seq data [50] were analyzed to examine the expression patterns of all 89 PsPP2C genes across 11 pea tissues: white flower, normal stipule, root, green pod, stem, fresh seed, tendril, imparipinnate leaf, light purple vexilla, dark purple wing, and purple pod, with three independent biological replicates per tissue.

For salt stress response analysis, two independent experiments were designed to explore the expression dynamics of PsPP2C genes under salt stress conditions. Pea seeds were germinated for three days and then transferred to sterile hydroponic boxes containing deionized water. Plants were grown under controlled environmental conditions: 26 °C, 50% relative humidity, 16 h light (200 µmol photons m−2 s−1), and 8 h dark. After one week, salt treatments were applied, with three biological replicates for each condition.

Experiment I (Concentration gradient): Seedlings were treated with five NaCl concentrations: T0 (0 mM), T30 (30 mM), T60 (60 mM), T90 (90 mM), and T120 (120 mM) for 72 h.

Experiment II (Time-course treatment): Seedlings were exposed to 100 mM NaCl, and samples were collected at seven time points: H0 (0 h), H1 (1 h), H3 (3 h), H6 (6 h), H12 (12 h), H24 (24 h), and H48 (48 h).

For each salt-stress treatment, three biological replicates were prepared. Seedlings were grown in a hydroponic box containing six plants. Each biological replicate consisted of a pooled sample from two individual plants within the same box (six plants per box pooled as three replicates). For each replicate, the two fully expanded apical leaves from each of the two plants were harvested and combined.

Total RNA was extracted from leaf tissues using TRIzol reagent, and RNA integrity and concentration were evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). cDNA libraries were constructed and sequenced on the DNBSEQ platform (MGI, Shenzhen, China) for high-throughput transcriptome profiling. Raw reads were quality-filtered using Fastp (v1.0.1) [51] with default parameters, and high-quality reads were aligned to the pea reference genome using HISAT2 (v2.1.0) [52]. Gene expression levels were quantified with FeatureCounts (v2.0.1) [53], and normalization was performed using the transcripts per million (TPM) method. To reduce background noise, genes with TPM values < 1 across all samples were removed prior to downstream analyses. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified using the DESeq2 (1.50.2) [54], which applies size-factor normalization and negative binomial generalized linear modeling. p values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg method. Genes with an adjusted p value (padj) < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| ≥ 1 were considered significantly differentially expressed.

2.6. Functional Annotation and Enrichment Analysis

Functional annotation of the PsPP2C proteins was performed using eggNOG-mapper (v2) [55] with the eukaryotic database and the pea genome protein sequences, applying default parameters. Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) terms were assigned based on the annotation results. Enrichment analysis of the PsPP2C genes was conducted using the clusterProfiler package [56], with a Benjamini–Hochberg adjusted p value < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Visualization of the enrichment results was carried out using the pheatmap package (https://github.com/raivokolde/pheatmap, accessed on 1 November 2025) in R (4.4.2).

2.7. RT–qPCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from leaf tissues collected under the same salt treatment conditions using the FastPure Plant Total RNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). RNA concentration and integrity were assessed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA using the HiScript® III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). Gene-specific primers were designed using NCBI Primer-BLAST. RT-qPCR was performed on a Roche LightCycler 96 real-time PCR system (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) using SupRealQ Purple SYBR Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The amplification program consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 10 s and 60 °C for 30 s. Each reaction included three technical replicates and three independent biological replicates. PsActin was used as the internal reference gene. Relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2^−ΔΔCt method. Statistical differences among treatment groups were assessed using the LSD test, with p < 0.05 considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the PP2C Gene Family in Pea

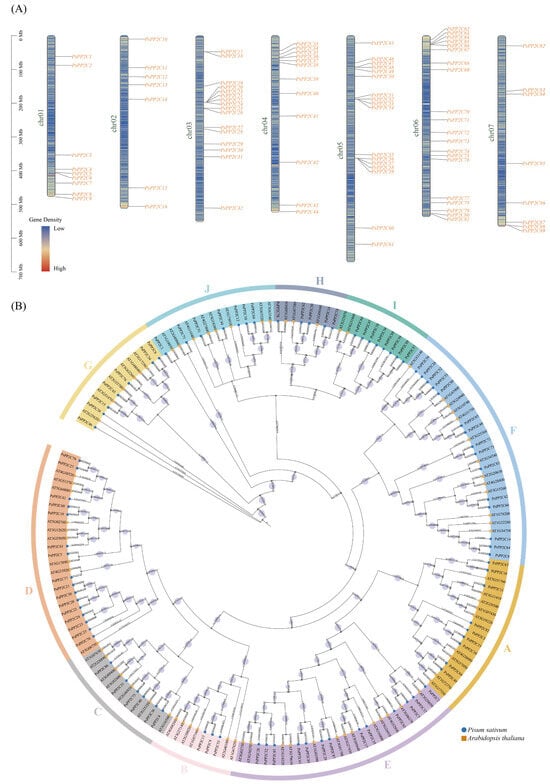

Using both HMM profile of the PP2C domain (PF00481) and BLAST searches based on A. thaliana PP2C sequences, a total of 89 PsPP2C genes were identified from the pea genome. These genes were designated as PsPP2C1 to PsPP2C89 according to their physical positions on the chromosomes. The PsPP2C genes were unevenly distributed across all seven chromosomes of pea. Among them, chromosome 6 contained the largest number of members (20 genes), followed by chromosome 5 (17 genes) and chromosome 3 (16 genes). In contrast, chromosome 4 harbored 12 genes, chromosome 1 contained 9, chromosome 7 contained 8, and chromosome 2 had the fewest (7 genes) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Chromosomal distribution and phylogenetic relationships of the PP2C gene family in pea. (A) Chromosomal locations of the 89 PsPP2C genes. All genes are mapped onto the pea chromosomes and labeled with their corresponding gene IDs. A red–blue gradient indicates local gene density, with red representing higher gene density and blue representing lower gene density. (B) Phylogenetic relationships between PP2C proteins from pea and A. thaliana. Pea and A. thaliana PP2Cs are marked with circles and squares, respectively. Pea PP2Cs were classified into subgroups A–J based on sequence similarity with A. thaliana proteins, and different background colors indicate these subgroups. Numbers at the nodes represent bootstrap support values, and the size of the light purple circles is proportional to the support value.

To explore their evolutionary relationships, a phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the amino acid sequences of PsPP2Cs together with A. thaliana PP2C proteins. According to sequence similarity, the PsPP2C proteins were classified into ten subgroups (A–J), consistent with the established classification in A. thaliana (Figure 1B).

The predicted amino acid lengths of PsPP2C proteins varied considerably, ranging from 53 residues (PsPP2C39) to 1083 residues (PsPP2C2), with corresponding molecular weights between 5.95 kDa (PsPP2C39) and 122.15 kDa (PsPP2C68). Their pI spanned from 4.55 (PsPP2C59) to 9.66 (PsPP2C73), with 67 proteins classified as acidic (pI < 7) and 22 as basic (pI ≥ 7) (Table S1).

Analysis of the instability index revealed that 78 proteins had values below 50, suggesting potential stability under in vitro conditions, while 11 were predicted to be unstable or moderately unstable. The aliphatic index ranged from 62.64 (PsPP2C39) to 93.52 (PsPP2C6), indicating generally high thermostability across the family. GRAVY values were mostly negative or close to zero (ranging from –0.777 in PsPP2C39 to 0.211 in PsPP2C12), implying that the majority of PsPP2C proteins are hydrophilic, with only PsPP2C12 showing slight hydrophobicity (Table S1).

Predicted subcellular localization suggested that PsPP2Cs are distributed among multiple cellular compartments. The majority were predicted to localize to the chloroplast (40 members), followed by the nucleus (24 members), cytoplasm (16 members), and mitochondria (5 members). A few members were predicted to localize to the vacuole (2: PsPP2C50 and PsPP2C62), cytoskeleton (1: PsPP2C63), and endoplasmic reticulum (1: PsPP2C89). These findings suggest that PsPP2C proteins may function in diverse cellular organelles, potentially participating in distinct signaling and regulatory processes (Table S1).

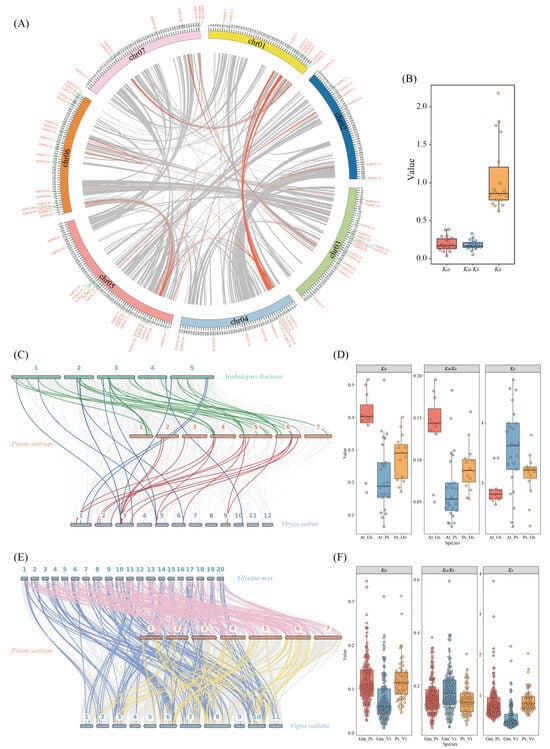

3.2. Evolutionary Dynamics of the PP2C Gene Family in Pea

To characterize the evolutionary dynamics of the PP2C gene family, we performed both intra-species and inter-species synteny analyses in pea, followed by Ka/Ks-based selection pressure assessment (Figure 2A–F; Tables S2 and S3). Within pea, a total of 19 syntenic PsPP2C gene pairs were identified across the genome (Figure 2A), most of which were located on different chromosomes or in distinct chromosomal regions, indicating that segmental duplication has been the major contributor to gene family expansion, with only one tandem duplication pair (PsPP2C72–PsPP2C73) detected. Among the 18 duplicated pairs with reliable codon alignments, all Ka/Ks ratios were substantially below 1 (0.054–0.330), ranging from PsPP2C48–PsPP2C65 (Ka/Ks = 0.054) to PsPP2C29–PsPP2C87 (Ka/Ks = 0.330) (Figure 2B; Table S2). One pair (PsPP2C34–PsPP2C76) showed high synonymous divergence (pS ≥ 0.75), resulting in unreliable Ks estimation, whereas Ks values for the remaining pairs varied between 0.626 and 2.179, reflecting different historical duplication events under predominantly strong purifying selection.

Figure 2.

Synteny relationships and evolutionary dynamics of the PP2C gene family in pea and other plant species. (A) Intra-genomic distribution, duplication events, and synteny relationships of PsPP2C genes in pea. Grey lines indicate syntenic genomic regions within the pea genome, while orange lines highlight duplicated PsPP2C gene pairs. (B) Boxplots showing Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks values for intra-species syntenic PsPP2C gene pairs in pea. (C) Inter-species synteny analysis of PP2C genes among pea, A. thaliana, and rice. Grey background lines represent conserved syntenic blocks across the three genomes. Green, red, and blue lines denote orthologous PP2C gene pairs between pea–A. thaliana, pea–rice, and A. thaliana–rice, respectively. (D) Boxplots showing Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks values for inter-species PP2C orthologous gene pairs among pea, A. thaliana, and rice. (E) Inter-species synteny analysis of PP2C genes among pea, soybean, and mung bean. Grey background lines indicate conserved syntenic blocks across the three genomes. Pink, yellow, and Light bluelines represent orthologous PP2C gene pairs between pea–soybean, pea–mung bean, and soybean–mung bean, respectively. (F) Boxplots showing the distributions of Ka, Ks, and Ka/Ks values for orthologous PP2C gene pairs among pea, soybean, and mung bean.

Inter-species synteny analysis detected 51 conserved PP2C orthologous gene pairs among pea, A. thaliana, and rice (Figure 2C; Table S3), consisting of 25 pea–A. thaliana, 15 pea–rice, and 11 A. thaliana–rice pairs. All orthologous pairs showed Ka/Ks < 0.2 (Figure 2D; Table S3), indicating pervasive functional constraint across species. The number of detectable syntenic pairs was higher between pea and A. thaliana than between pea and rice (Figure 2C), consistent with the greater retention of homologous loci between the two dicots. In contrast, fewer syntenic pairs were detectable between pea and rice, consistent with deeper divergence and extensive lineage-specific evolutionary events.

To extend the comparison within legumes, we further identified 360 PP2C orthologous gene pairs among soybean, pea, and mung bean (Figure 2D; Table S3). Among them, 164 pairs belonged to the soybean–pea comparison (45.6%), 136 to soybean–mung bean (37.8%), and 60 to pea–mung bean (16.7%). All orthologous pairs displayed Ka/Ks < 1, with an average of 0.1646, supporting strong purifying selection across legumes. Evolutionary rates differed moderately among species pairs, with soybean–pea showing the lowest Ka/Ks (0.1583), soybean–mung bean the highest (0.1807), and pea–mung bean the most conserved pattern (0.1452). Ka values were uniformly low across all comparisons (mean = 0.1037), whereas Ks exhibited a broad range (0.1874–3.8200) (Figure 2E, Table S3), indicating variable divergence times among orthologous PP2C genes. Together, these analyses define the duplication patterns and evolutionary constraints shaping PP2C gene family diversification across pea and related plant lineages.

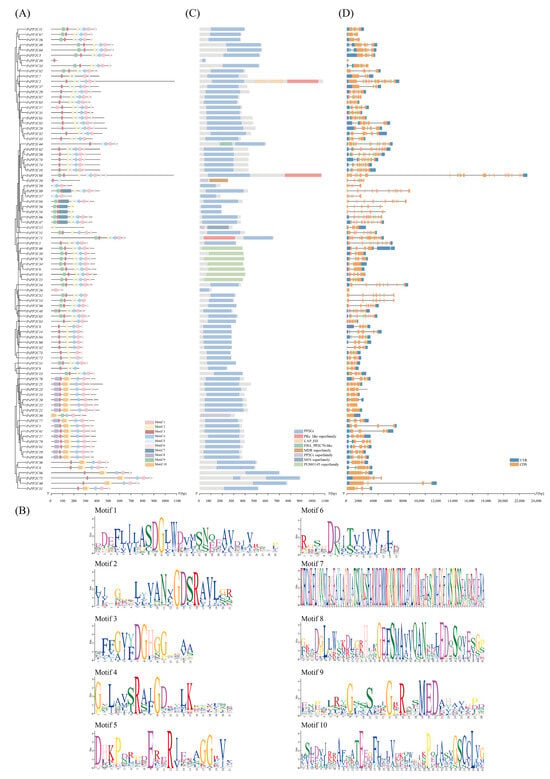

3.3. Conserved Motifs, Protein Domains, and Gene Structures of the PsPP2C Family

Conserved motif analysis of the 89 PsPP2C proteins identified ten well-defined motifs (motifs 1–10) distributed across the family (Figure 3A). Among these, Motif 1, consisting of 29 amino acids (Figure 3B), was the most conserved element and was present in 83 members, underscoring its essential role in maintaining the core structural and functional features of PP2C proteins. Most PsPP2C proteins contained five to seven conserved motifs, with Motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 commonly co-occurring across multiple subfamilies, thereby constituting the fundamental structural framework of the family. Motif lengths ranged from 6 to 50 amino acids, and the longer motifs likely correspond to specialized functional or structural modules. The relative positions of motifs were highly conserved among homologous genes, indicating strong structural constraints acting on the PP2C family throughout evolution.

Figure 3.

Conserved motifs, domain architectures, and gene structures of the PsPP2C gene family. (A) Distribution of conserved motifs across PsPP2C proteins. The x-axis represents amino acid positions, and the y-axis lists individual PsPP2C genes. Colored blocks indicate the relative positions of each motif within the corresponding protein. (B) Sequence logos of the ten conserved motifs (motifs 1–10). The height of each letter reflects residue conservation, with highly conserved amino acids shown in larger characters. (C) Domain architecture of PsPP2C proteins, illustrating the distribution of functional domains including PP2Cc, PKc_like superfamily, CAP_ED, FHA_PP2C70-like, MDR superfamily, PP2Cc superfamily, MFS superfamily, and PLN03145 superfamily. (D) Gene structure organization of PsPP2C genes. Blue boxes denote UTRs, orange boxes represent CDSs, and black lines indicate introns. The x-axis shows gene length (bp), and the y-axis represents individual genes.

Domain architecture analysis further revealed considerable structural diversification within the family. The vast majority of PsPP2C proteins contained the canonical PP2Cc catalytic domain, the hallmark of PP2C phosphatases responsible for Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent dephosphorylation activity (Figure 3C), confirming their classification within the classical PP2C superfamily. Notably, several PsPP2C members exhibited additional or atypical domains, suggesting potential functional diversification. PsPP2C2, PsPP2C68, and PsPP2C71 harbored both the PP2Cc domain and a PKc_like kinase-like catalytic domain, implying possible dual regulatory functionality. PsPP2C46, PsPP2C38, PsPP2C76, PsPP2C34, PsPP2C6, and PsPP2C45 contained the plant-specific PLN03145 superfamily domain, which may be associated with specialized roles in plant signaling. Moreover, PsPP2C10 and PsPP2C12 were annotated with MDR and MFS superfamily domains, respectively, representing unusual domain combinations within the PP2C family.

The PsPP2C gene family exhibited remarkable structural diversity and complexity (Figure 3D). Gene length varied substantially, ranging from 1.9 kb (PsPP2C72) to 7.6 kb (PsPP2C88), with most genes falling between 3–6 kb (average 4.2 kb). Notably, several short genes (e.g., PsPP2C72, PsPP2C88) contained a relatively high number of exons, suggesting extensive intron reduction during evolution. Exon–intron organization was highly heterogeneous across the family, with exon numbers spanning from 2 to 15. The most frequent structural classes were genes with 4 exons (25.8%), 5 exons (21.3%), and 6 exons (18.0%). A few genes displayed extreme configurations, such as PsPP2C2 with 15 exons, whereas PsPP2C22 and PsPP2C23 contained only 2 exons. These striking differences imply that the PsPP2C family has undergone lineage-specific exon gain/loss and intron insertion/deletion events, contributing to its structural diversification. The splice phase distribution showed a strong preference for phase 0 introns (56.4%), followed by phase 2 (27.1%) and phase 1 (16.5%). This dominance of phase 0 suggests a relatively conserved splicing environment that helps maintain protein structural integrity during evolution. Approximately 42% of PsPP2C genes possessed complex untranslated region (UTR) architectures, characterized by multiple discontinuous UTR fragments rather than single continuous segments. For example, PsPP2C4 contained three 5′UTR fragments, whereas PsPP2C14 and PsPP2C78 harbored two to three 5′UTR fragments in addition to a 3′UTR. Such UTR complexity indicates the potential involvement of alternative transcription start sites, alternative splicing, or internal ribosome entry sites, which may contribute to diverse transcript isoforms and fine-tuned post-transcriptional regulation.

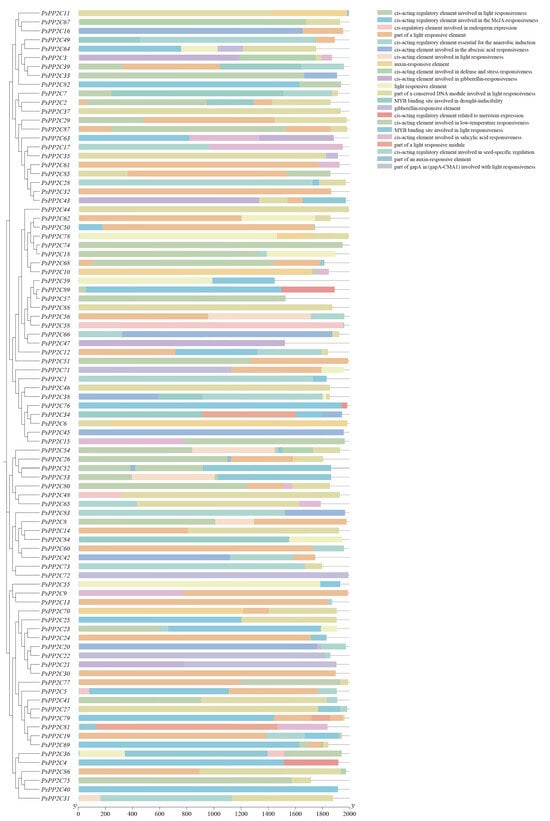

3.4. Cis-Regulatory Landscape of PsPP2C Promoters Reveals Extensive Light, Hormone, and Stress Responsiveness

Prediction of cis-regulatory elements within the 2000 bp regions upstream of the annotated TSSs of the 89 PsPP2C genes—defined from the high-quality pea genome annotation using the longest transcript for each locus—revealed a broad set of regulatory motifs with non-random distribution patterns (Figure 4; Table S4). Light-responsive elements formed the largest group, including Box4, G-box, GT1-motif, MRE, and I-box. Their positional profiles showed that G-box and Box4 frequently occurred between −200 and −800 bp, suggesting a commonly utilized light-responsive module in many PsPP2C promoters (Figure 4; Table S4).

Figure 4.

Distribution of cis-acting regulatory elements in the promoters of the PsPP2C Gene family. The x-axis represents the promoter region relative to the transcription start site (0–2000 bp), and the y-axis lists the 89 PsPP2C genes. Different colors or symbols denote distinct types of cis-acting regulatory elements, with vertical lines indicating the precise positions of each element within the promoter.

Hormone-related motifs were also widespread. ABRE elements appeared in most promoters, often in multiple copies, consistent with the well-known ABA regulation of PP2C genes. JA-responsive TGACG-motif and CGTCA-motif commonly occurred as paired units, while GA-responsive elements (GARE-motif, P-box, TATC-box) displayed gene-specific occurrences. Auxin-related motifs, including AuxRE and TGA-element, were also detected in a subset of promoters (Figure 4; Table S4).

Stress-responsive motifs contributed additional regulatory diversity. TC-rich repeats, MBS elements associated with drought responses, and LTR motifs associated with low-temperature responses were observed across multiple PsPP2C promoters, and ARE elements appeared in the majority of genes. Developmentally related motifs—such as RY-element and GCN4_motif—occurred in several promoters, suggesting possible roles during seed development (Figure 4; Table S4).

These observations indicate that the upstream regions of PsPP2C genes contain a broad repertoire of light, hormone, stress, and development-associated cis-elements with non-random distribution patterns.

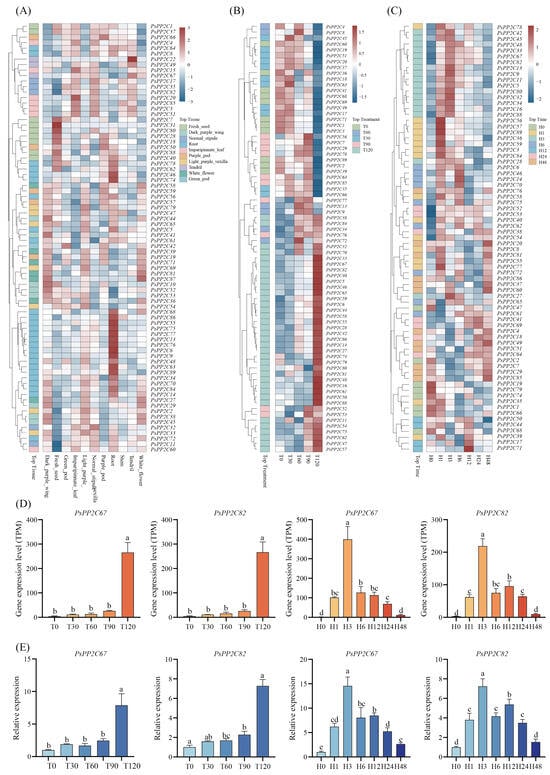

3.5. Spatiotemporal and Stress-Responsive Expression Profiles of PsPP2C Genes

To comprehensively characterize the expression patterns of PsPP2C genes across tissues and under salt-stress conditions, we assessed the quality and alignment performance of RNA-seq data generated from 69 samples, including 11 tissues as well as salt concentration- and time-gradient treatments (Table S5). On average, each sample yielded 48.7 ± 6.5 million clean reads with a retention rate close to 100%. The sequencing quality was high, with Q20 and Q30 values of 98.8 ± 0.2% and 96.5 ± 0.4%, respectively, and GC contents ranging from 41.9% to 43.7%, consistent with typical plant transcriptomes. When mapped to the pea reference genome, reads exhibited an average alignment rate of 98.0 ± 0.8%, including 89.9% uniquely mapped and 6.5% multi-mapped reads, while only 3.2% remained unmapped. These results demonstrate that the RNA-seq data are of high quality and highly compatible with the reference genome, providing a robust foundation for downstream expression analyses.

RNA-seq profiling across 11 tissues revealed pronounced spatial specificity in PsPP2C gene expression (Figure 5A; Table S6). Roots exhibited the highest overall expression, with numerous genes showing enrichment, reflecting high demand for phosphatase-mediated signaling during root growth and stress perception. Fresh seeds also displayed elevated expression, consistent with the complex hormone regulatory networks required for seed development and germination. Normal stipules showed notable expression for multiple genes, suggesting potential roles in leaf morphogenesis and photosynthetic regulation.

Figure 5.

Expression profiles of PsPP2C genes across tissues and under salt stress. (A–C) Heatmaps showing the expression patterns of 89 PsPP2C genes across 11 tissues (A), under different NaCl concentrations (0–120 mM) (B), and across a 0–48 h salt-stress time course (C). Genes are clustered based on expression similarity, and the blue-to-red gradient represents low to high transcript abundance. The annotation panels between the gene clusters and the heatmap indicate the tissue, salt concentration, or time point at which each gene shows maximal expression. (D) TPM values of PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 under different NaCl concentrations and time points. (E) Relative expression levels of PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 under the same conditions, validated by RT-qPCR. Lowercase letters in panels (D,E) indicate significant differences among treatments according to LSD tests (p < 0.05).

Three genes—PsPP2C21, PsPP2C24, and PsPP2C30—were not detectably expressed in any tissue, whereas PsPP2C43 exhibited highly restricted expression, with low levels detected almost exclusively in light-purple vexilla. Based on expression patterns, the PsPP2C family can be classified into root-enriched, flower-specific, seed-development-related, leaf-associated and broadly expressed groups. Despite differences in tissue composition between the cultivars Zhongwan 6 and Yunwan 127, most PsPP2C members displayed consistent expression trends across corresponding tissue types, indicating conserved transcriptional regulation within the species (Figure 5A; Table S6).

Expression profiling under five NaCl concentrations (0–120 mM) demonstrated clear dose-dependent regulation of PsPP2C genes (Figure 5B; Table S7). Approximately 20% of the genes showed induction or repression in response to increasing salt severity. PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 were the most strongly induced, showing nearly 100-fold upregulation at 120 mM NaCl. In contrast, The expression levels of PsPP2C51 and PsPP2C60 gradually decreased with increasing treatment concentration, suggesting roles in attenuating or balancing stress-related signaling. A subset of genes—including PsPP2C34, PsPP2C38, PsPP2C76 and PsPP2C84—displayed moderate induction, reaching peak expression at 90–120 mM. Conversely, genes such as PsPP2C45, PsPP2C49 and PsPP2C85 were downregulated across the concentration series, indicating negative or suppressive regulatory roles.

Time-course analysis (0–48 h) revealed additional layers of temporal regulation (Figure 5C; Table S8). Early-responsive genes—including PsPP2C67, PsPP2C82, PsPP2C33 and PsPP2C13—showed rapid induction within 1–3 h, with expression levels reaching 200–400-fold above the control for some genes. These genes gradually returned to baseline by 48 h, suggesting roles in fast stress recognition and early signal relay. Several genes, such as PsPP2C11, maintained elevated expression through the midphase (3–6 h), representing sustained-response regulators. In contrast, late-responsive genes—including PsPP2C60, PsPP2C28 and PsPP2C32—showed induction primarily at 24–48 h, consistent with roles in downstream adaptation and recovery processes. Approximately 70% of the genes remained stable throughout the time series, indicating housekeeping or standby functions. About 5%—PsPP2C21, PsPP2C30, PsPP2C31, PsPP2C43, PsPP2C83 and PsPP2C87—showed minimal or no expression under any treatment, suggesting limited involvement in salt-related pathways or activation only under specific conditions not tested here.

A subset of PsPP2C genes showed pronounced and consistent transcriptional responses across both the salt-concentration and time-course RNA-seq datasets. In particular, PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 exhibited the strongest induction under increasing NaCl concentrations (Figure 5B,D) and rapid early activation following salt exposure (Figure 5C,D), making them representative markers of salt-responsive PP2Cs. To experimentally confirm these RNA-seq patterns, gene-specific primers were designed for both genes (Table S9), and RT-qPCR assays were performed under the same salt-concentration and time-course conditions. The RT-qPCR results reproduced the expression trends observed in the RNA-seq data, confirming the strong induction of PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 and supporting the overall reliability of our transcriptomic analyses (Figure 5E).

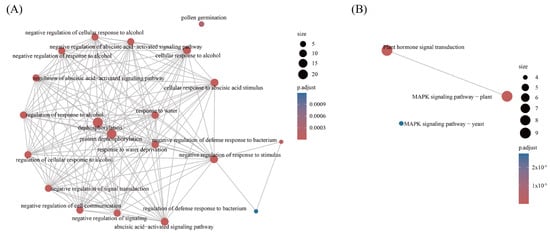

3.6. Functional Enrichment Identifies Key Biological Roles of the PsPP2C Gene Family

GO enrichment analysis of the 89 PsPP2C genes identified functional specificity in the molecular function, cellular component, and biological process categories (Figure 6A; Table S10). At the molecular function level, “protein dephosphorylation” and “serine/threonine phosphatase activity” were the most significantly enriched terms, consistent with the known biochemical roles of PP2Cs as Mg2+/Mn2+-dependent phosphatases. These results confirm their roles in phosphorylation-based signaling.

Figure 6.

Functional annotation and pathway enrichment analyses of PsPP2C genes. (A) GO enrichment analysis showing the biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions associated with PsPP2C genes. (B) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis. For both panels, bubble size represents the number of genes enriched in each category, and bubble color indicates statistical significance.

Within the biological process category, enrichment terms indicated a role for PsPP2C genes in stress adaptation and developmental regulation. Several terms associated with abiotic stress responses were significantly overrepresented, including “negative regulation of ABA-activated signaling pathway”, “response to water deprivation”, “response to osmotic stress”, and “plant recovery from drought” (Figure 6A; Table S10). These findings support the known role of PsPP2C genes in ABA signaling and stress responses, particularly in drought and salt tolerance.

KEGG pathway enrichment further supported these observations, with “plant hormone signal transduction” and “MAPK signaling pathway” identified as prominent pathways (Figure 6B; Table S11). These results align with the known roles of PsPP2C genes in integrating hormonal and kinase-mediated signaling. Enrichment of terms related to “defense response to bacteria” and its negative regulation suggests that some PsPP2C genes may also be involved in biotic stress responses.

PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82, both enriched in ABA-related functions and protein dephosphorylation, exhibited the strongest induction under both high-salt (120 mM) and early time-point (3 h) treatments (Figure 5B–E), consistent with their roles in ABA-mediated stress signaling. PsPP2C33, enriched for serine/threonine phosphatase activity, showed peak expression at 3 h and under 90–120 mM NaCl, suggesting a key regulatory function in salt-stress signal relay. Genes such as PsPP2C34 and PsPP2C38, enriched for water-stress responses, showed moderate induction across both dimensions, whereas PsPP2C51 and PsPP2C60 displayed contrasting regulation between concentration- and time-dependent treatments, pointing to potentially distinct roles in short-term adjustment versus long-term recovery (Figure 5B,C). Together, these findings reveal a finely tuned regulatory landscape in which PsPP2C genes balance stress tolerance with growth-related processes.

4. Discussion

This study provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the PP2C gene family in pea and establishes direct links between specific PsPP2C members and salt-stress signaling. We identified 89 PsPP2C genes (Figure 1), a family size comparable to those reported in other dicot and monocot species, such as 86 BdPP2Cs in Brachypodium distachyon [2], 178 AhPP2Cs in peanut [6], and up to 181 PP2Cs in cotton [5], although smaller than the expanded families found in certain polyploid or highly repetitive genomes. The PsPP2Cs were assigned to ten subfamilies (A–J) (Figure 1B), and their conserved motif composition together with the highly preserved PP2Cc catalytic domain indicate that the canonical molecular architecture of PP2Cs has been retained in pea and broadly conserved during legume evolution. Meanwhile, the presence of kinase-like domains, plant-specific PLN03145 domains, and unusual MDR/MFS domain combinations in some PsPP2Cs points to lineage-specific structural innovation that likely contributes to specialized signaling functions (Figure 3). Similar patterns of structural diversification have been documented in B. distachyon [2], Rosaceae species [57], and sugarcane (Saccharum) [58], suggesting that domain acquisition is a common mechanism by which PP2Cs expand their regulatory repertoire across angiosperms.

Chromosomal distribution and collinearity analyses showed that segmental duplication is the primary force driving PsPP2C expansion, whereas tandem duplication has played a minimal role (Figure 2A). The consistently low Ka/Ks values of both intra- and interspecies paralogous pairs (Figure 2) indicate pervasive purifying selection, consistent with the central roles of PP2Cs within highly constrained phosphorylation–dephosphorylation networks that tolerate little functional disruption. The synteny analysis revealed more conserved PP2C orthologous pairs between pea and the fellow dicot A. thaliana than between pea and the monocot rice (Figure 2C), consistent with their respective phylogenetic distances. Within legumes, a substantially larger number of orthologous pairs was retained: 164 pairs between soybean–pea, 60 pairs between pea–mung bean, and 136 pairs between soybean–mung bean (Figure 2E). All interspecific orthologous pairs, both across dicots/monocots and within legumes, exhibited Ka/Ks ratios markedly below 1 (Figure 2D,F) [59], indicating that purifying selection has been the dominant evolutionary force acting on these genes.

Promoter architecture and cis-element composition of PsPP2C genes suggest that these genes may play an integral role in linking environmental and hormonal signals to transcriptional regulation. The clustering of light-responsive elements, including G-box and Box4 motifs, within proximal promoter regions implies potential regulation by light-responsive transcription factors. These patterns suggest that PsPP2C genes could be involved in coordinating dephosphorylation processes related to light signaling (Figure 4; Table S4), though further experimental validation is required to confirm the functional relevance of these motifs. Similarly, the presence of ABRE elements, often in multiple copies, in the promoters of many PsPP2C genes hints at a role in ABA signaling, aligning with the known involvement of PP2Cs as negative regulators of ABA responses. However, these motifs serve as potential indicators rather than conclusive evidence of the integration of ABA-mediated regulation in PsPP2C gene expression [60,61].

Moreover, the detection of JA, GA, and auxin-responsive motifs in the promoters suggests that PsPP2Cs may be involved in hormone cross-talk, particularly under stress conditions. This is consistent with reports in other species such as rice and peanut, where PP2C isoforms are known to integrate various hormonal pathways under stress [4,5,58]. Additionally, the presence of cis-elements associated with stress responses (e.g., drought, low temperature, and anaerobic conditions) as well as developmentally regulated motifs suggests that PsPP2C genes could play a role not only in environmental stress adaptation but also in developmental processes such as seed maturation and germination (Figure 4; Table S4). While these results point to a broad regulatory role for PsPP2Cs, the functional significance of these motifs requires further investigation to establish their precise role in transcriptional regulation.

Spatial expression profiles across 11 tissues highlight the transcriptional diversity of the PsPP2C gene family. Roots and fresh seeds showed the highest overall expression, consistent with the intensive signaling demands associated with root growth, nutrient and water uptake, and the hormone-rich environment of seed development (Figure 5A; Table S6). Distinct clusters of root-enriched, flower-specific, seed-associated, leaf-related, and broadly expressed PsPP2Cs suggest potential organ-associated roles or transcriptional differentiation among individual genes or subgroups, echoing tissue-specific patterns documented in cotton [5], peanut [6], and Rosaceae species [57]. Certain narrowly expressed genes—for example, PsPP2C43, which is expressed only in light-purple flag petals—may be associated with highly specialized processes related to flower development or pigment-related signaling. Conversely, a small set of genes transcriptionally silent across all tested tissues may represent stress-inducible loci, pseudogenes, or regulatory elements functioning primarily through protein-level interactions rather than dynamic transcript accumulation (Figure 5A; Table S6).

Salt-stress experiments provided the strongest evidence for transcriptional specialization within the PsPP2C gene family. Approximately one-fifth of PsPP2Cs exhibited dose- or time-dependent expression changes, indicating that only a subset of the family shows pronounced transcriptional responsiveness under salt stress (Figure 5B,C; Tables S7 and S8). PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 emerged as prominently salt-responsive candidate genes, showing ~100-fold induction at 120 mM NaCl and displaying rapid, transient upregulation within 1–3 h of exposure, followed by a gradual return to baseline (Figure 5D,E). Such expression kinetics are commonly observed among early stress-responsive genes and are consistent with a potential involvement of PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 in ABA- and ion-homeostasis–related signaling processes (Figure 6, Tables S7 and S8). Their enrichment in ABA-related annotations and protein dephosphorylation categories is consistent with the canonical ABA signaling framework, in which PP2Cs repress SnRK2s in the absence of ABA but are inhibited when ABA levels increase [60]. Notably, previous work in A. thaliana and rice has shown that clade A PP2Cs (e.g., ABI1/ABI2, OsPP2C09, OsPP65) can either promote or suppress stress tolerance depending on their interaction partners and regulatory contexts, and their abundance and subcellular localization are tightly controlled [60,62,63]. Thus, the strong early induction of PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 may reflect a potential role in the fine-tuning of ABA signaling dynamics under salt stress, rather than a simple linear relationship with stress inhibition.

Other PsPP2Cs may be associated with in downstream or antagonistic phases of the salt response. For example, PsPP2C34 and PsPP2C38 exhibited moderate induction across higher salinity levels and broader time windows, suggesting roles in sustaining stress responses or coordinating recovery after partial restoration of homeostasis. In contrast, PsPP2C51 and PsPP2C60 were markedly downregulated with increasing salinity or over time (Figure 5B,C; Tables S7 and S8), implying that reduced expression of specific PP2Cs may be associated with decreased phosphatase-mediated constraints on key kinases or transcription factors during stress adaptation. Such bidirectional regulation within the same gene family mirrors patterns in peanut [6], cotton [5] and B. distachyon [2], where different PP2C subgroups are induced or repressed under salt, drought or cold, collectively shaping the amplitude and duration of stress-response signaling. The coexistence of PsPP2Cs exhibiting early, intermediate, or late transcriptional responses—including genes with sustained induction (e.g., PsPP2C11) and those activated predominantly at later time points (e.g., PsPP2C28 and PsPP2C32)—suggests temporal diversity in PsPP2C expression patterns during salt stress, without implying causal ordering or pathway hierarchy.

Together, these findings provide a comprehensive genome-wide overview of the PsPP2C gene family in pea, integrating evolutionary conservation, cis-regulatory element composition, tissue-specific transcriptional patterns, and salt-responsive expression dynamics. By combining comparative genomic analyses with spatial and stress-induced expression profiling, this study establishes a foundational framework for understanding the diversity and transcriptional behavior of PsPP2C genes in pea. Within this framework, PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 were identified as consistently and strongly salt-responsive genes at the transcriptional level, based on both RNA-seq and RT-qPCR analyses. Their reproducible and early induction under salt stress highlights them as high-priority candidates for further functional investigation, providing a focused starting point for future studies aiming to dissect PP2C-associated stress-response mechanisms in pea, including potential involvement in ABA-related signaling pathways and responses to combined stresses such as salt–drought or salt–cold [63,64].

Although this study provides a comprehensive genomic and transcriptional framework for the PsPP2C gene family in pea, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our conclusions rely primarily on gene expression data from RNA-seq and RT-qPCR; however, transcript levels do not necessarily correlate with protein abundance, post-translational modifications, phosphatase activity, or ultimate regulatory function. Second, the use of pooled samples for RNA-seq, while reducing individual variation and enabling robust detection of treatment effects, may have obscured biological variability among plants. Third, the study lacks direct physiological or phenotypic assays—such as measurements of germination rate, root elongation, ion homeostasis, osmotic adjustment, or reactive oxygen species accumulation under salt stress—that could link differential PsPP2C expression to tangible salt-tolerance traits in pea. Additionally, functional validation through genetic approaches (e.g., overexpression, knockdown, or CRISPR/Cas9 editing), subcellular localization studies, or protein–protein interaction analyses (e.g., with PYR/PYL receptors or SnRK2 kinases) was not performed. Consequently, the proposed roles of specific PsPP2C members, particularly PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82, in ABA-dependent salt stress signaling remain hypothetical. Future studies can build on this foundational resource by conducting targeted functional characterization of candidate genes, integrating proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses, and evaluating transgenic or mutant lines under controlled salt stress conditions to definitively elucidate their contributions to salinity tolerance in pea.

5. Conclusions

This study presents a genome-wide identification and characterization of the PP2C gene family in pea. A total of 89 PsPP2C genes were identified and classified into ten subfamilies, revealing conserved PP2Cc catalytic domains together with substantial diversity in gene structure, protein architecture, and promoter cis-element composition. Comparative synteny and Ka/Ks analyses indicated that segmental duplication played a major role in the expansion of the PsPP2C family and that most duplicated gene pairs have evolved under strong purifying selection. Expression profiling across multiple tissues demonstrated pronounced spatial transcriptional diversity among PsPP2C genes, while salt-stress treatments revealed that a subset of family members exhibited reproducible concentration- or time-dependent transcriptional responses. Among these, PsPP2C67 and PsPP2C82 showed the most consistent and early induction across salt-stress conditions, identifying them as prominent salt-responsive members of the PsPP2C family at the transcriptional level. Together, these results provide the first integrated genomic, evolutionary, and expression framework for the PP2C gene family in pea and establish a valuable resource for comparative analyses and future functional studies. The identification of salt-responsive PsPP2C candidates offers a focused starting point for subsequent investigations into PP2C-associated stress-response processes in pea.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122920/s1, Table S1. Physicochemical properties of PsPP2C family genes; Table S2. Intraspecific synteny and evolutionary analysis of PP2C gene pairs in psa; Table S3. Interspecific collinear PP2C gene pairs with Ka/Ks estimates; Table S4. Prediction of cis-acting elements in the PsPP2C gene family; Table S5. Detailed information on RNA sequencing data of samples under salt stress; Table S6. Transcriptional expression levels (TPM) of the PsPP2C gene family in various tissues; Table S7. Transcriptional expression levels (TPM) of PsPP2C genes under different salt stress concentrations; Table S8. Expression levels (TPM) of the PsPP2C gene family under salt stress (constant concentration) at different time points; Table S9. Primer sequences for RT-qPCR analysis of PsPP2C genes and reference gene; Table S10. GO enrichment analysis of PsPP2C genes; Table S11. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of PsPP2C genes.

Author Contributions

K.-H.J. and N.-N.L. conceived and designed the study; M.L., Y.-Z.C., W.-J.W., T.Z., H.-T.S., S.H., Z.-M.S., G.L., R.-M.T., Y.-Y.Y., K.X., L.W. and N.-N.L. collected materials and analyzed the data; Z.-W.W. prepared figures and tables; Z.-W.W. wrote and revised the manuscript; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the earmarked fund for Shandong Agriculture Research System (SDARS-15), the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province (2025LZGC009, 2024TZXD052, 2023LZGC001, and 2022LZGC022), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32201736), and the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Project of SAAS (CXGC2023F13, CXGC2025B02, CXGC2025H21).

Data Availability Statement

All RNA-seq datasets generated or used in this study are deposited in the National GeneBank Database (CNGBdb). RNA-seq data from 11 pea tissues are available under accession number CNP0006001, and RNA-seq data from pea leaves subjected to different NaCl concentrations are available under accession number CNP0006814.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PP2C | Protein phosphatase 2C |

| PK | Protein kinase |

| PP | Protein phosphatase |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| GA | Gibberellin |

| HMM | Hidden Markov Model |

| BLASTP | Basic Local Alignment Search Tool |

| ML | Maximum Likelihood |

| JTT | Jones–Taylor–Thornton |

| SH-like | Shimodaira–Hasegawa-like |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| eggNOE | Evolutionary Genealogy of Genes: Non-supervised Orthologous Groups |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| TPM | Transcripts Per Million |

| JCVI | Python library for comparative genomics and evolution |

| CDS | Coding Sequence |

| UTR | Untranslated Region |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| DNBSEQ | DNA nanoball sequencing platform |

| Ka | Nonsynonymous substitution rate |

| Ks | Synonymous substitution rate |

| CNGBdb | China National GeneBank Database |

| pI | Theoretical isoelectric point |

References

- Lessard, P.; Kreis, M.; Thomas, M. Les protéines phosphatases et protéines kinases des plantes supérieuresProtein phosphatases and protein kinases in higher plants. Comptes Rendus de l’Académie des Sciences—Series III—Sciences de la Vie 1997, 320, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Jiang, M.; Li, P.; Chu, Z. Genome-wide identification and evolutionary analyses of the PP2C gene family with their expression profiling in response to multiple stresses in Brachypodium distachyon. BMC Genom. 2016, 17, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerk, D.; Bulgrien, J.; Smith, D.W.; Barsam, B.; Veretnik, S.; Gribskov, M. The complement of protein phosphatase catalytic subunits encoded in the genome of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 908–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Giri, J.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K.; Pandey, G.K. Protein phosphatase complement in rice: Genome-wide identification and transcriptional analysis under abiotic stress conditions and reproductive development. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shazadee, H.; Khan, N.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Zeng, J.; Huang, Z.; Wang, X. Identification and Expression Profiling of Protein Phosphatases (PP2C) Gene Family in Gossypium hirsutum L. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Luo, L.; Wan, Y.; Liu, F. Genome-wide characterization of the PP2C gene family in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) and identification of candidate genes involved in salinity-stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1093913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Cao, L.; Ye, F.; Ma, C.; Liang, X.; Song, Y.; Lu, X. Identification of the maize PP2C gene family and functional studies on the role of ZmPP2C15 in drought tolerance. Plants 2024, 13, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, J.M.; Collinge, M.A.; Smith, R.D.; Horn, M.A.; Walker, J.C. Interaction of a protein phosphatase with an Arabidopsis serine-threonine receptor kinase. Science 1994, 266, 793–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.L.; Ancillo, G.; Mayda, E.; Vera, P. A novel transcription factor involved in plant defense endowed with protein phosphatase activity. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 3376–3384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Sun, X.; Gao, S.; Qin, F.; Dai, M. Deletion of an endoplasmic reticulum stress response element in a ZmPP2C-A gene facilitates drought tolerance of maize seedlings. Mol. Plant 2017, 10, 456–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, H.; Kondo, S.; Tanaka, T.; Imamura, C.; Muramoto, N.; Hattori, E.; Ogawa, K.; Mitsukawa, N.; Ohto, C. Overexpression of a novel Arabidopsis PP2C isoform, AtPP2CF1, enhances plant biomass production by increasing inflorescence stem growth. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 5385–5400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, T.; Wang, D.; Zhang, S.; Ehlting, J.; Ni, F.; Jakab, S.; Zheng, C.; Zhong, Y. Genome-wide and expression analysis of protein phosphatase 2C in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Genom. 2008, 9, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ding, J.; Huang, W.; Yu, H.; Wu, S.; Li, W.; Mao, X.; Chen, W.; Xing, J.; Li, C.; et al. OsPP65 negatively regulates osmotic and salt stress responses through regulating phytohormone and raffinose family oligosaccharide metabolic pathways in rice. Rice 2022, 15, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhai, H.; Cai, H.; Ji, W.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Bai, X. AtPP2CG1, a protein phosphatase 2C, positively regulates salt tolerance of Arabidopsis in an abscisic acid-dependent manner. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 422, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Park, S.I.; Kwon, H.; Cho, M.H.; Kim, B.G.; Chung, J.H.; Nam, M.H.; Song, J.S.; Kim, K.H.; Yoon, I.S. The rice abscisic acid-responsive RING finger E3 ligase OsRF1 targets OsPP2C09 for degradation and confers drought and salinity tolerance in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 797940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perri, S.; Molini, A.; Hedin, L.O.; Porporato, A. Contrasting effects of aridity and seasonality on global salinization. Nat. Geosci. 2022, 15, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpede, M.; Percoco, M. Aridification, precipitations and crop productivity: Evidence from the aridity index. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2023, 50, 978–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-W.; Li, G.; Liu, M.; Cheng, X.; Li, L.-L.; Li, R.-Z.; Tian, R.-M.; Hou, S.; Zhao, J.-Y.; Yang, Y.-Y.; et al. Dose-dependent transcriptional reprogramming and lipid-associated defense under salt stress in mung bean (Vigna radiata). BMC Plant Biol. 2025, 25, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-W.; Li, G.; Li, R.-Z.; Tian, R.-M.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Hou, S.; Zhao, J.-Y.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Xie, K.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of the TCP transcription factor family in mung bean and its dynamic regulatory network under salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1602810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, B.; Yuan, F. Genome-wide identification of bHLH transcription factors and functional analysis in salt gland development of the recretohalophyte sea lavender (Limonium bicolor). Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Mao, M.; Ding, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Lai, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. The amino acid permease SlAAP6 contributes to tomato growth and salt tolerance by mediating branched-chain amino acid transport. Hortic. Res. 2024, 12, uhae286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, G.; Xuan, C.; Guo, Y.; Huang, X.; Feng, M.; Yuan, L.; Li, H.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; et al. The transcription factor ClWRKY61 interacts with ClLEA55 to enhance salt tolerance in watermelon. Hortic. Res. 2024, 12, uhae320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Yang, W.; Jing, W.; Shahid, M.O.; Liu, Y.; Qiu, X.; Choisy, P.; Xu, T.; Ma, N.; Gao, J.; et al. Multi-omics analysis reveals key regulatory defense pathways and genes involved in salt tolerance of rose plants. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grela, E.R.; Kiczorowska, B.; Samolińska, W.; Matras, J.; Kiczorowski, P.; Rybiński, W.; Hanczakowska, E. Chemical composition of leguminous seeds: Part I—Content of basic nutrients, amino acids, phytochemical compounds, and antioxidant activity. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2017, 243, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Gudi, S.; Amandeep; Upadhyay, P.; Shekhawat, P.K.; Nayak, G.; Goyal, L.; Kumar, D.; Kumar, P.; Kamboj, A.; et al. Unlocking the hidden variation from wild repository for accelerating genetic gain in legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1035878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, H.; Cao, L.; Wang, P.; Hu, H.; Guo, R.; Chen, J.; Zhao, H.; Zeng, C.; Liu, X. Genome-wide mapping of main histone modifications and coordination regulation of metabolic genes under salt stress in pea (Pisum sativum L). Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhae259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamouda, M.M.; Badr, A.; Ali, S.S.; Adham, A.M.; Ahmed, H.I.S.; Saad-Allah, K.M. Growth, physiological, and molecular responses of three phaeophyte extracts on salt-stressed pea (Pisum sativum L.) seedlings. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 2023, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.H.; Baset Mia, M.A.; Quddus, M.A.; Sarker, K.K.; Rahman, M.; Skalicky, M.; Brestic, M.; Gaber, A.; Alsuhaibani, A.M.; Hossain, A. Salinity-induced physiological changes in pea (Pisum sativum L.): Germination rate, biomass accumulation, relative water content, seedling vigor and salt tolerance index. Plants 2022, 11, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soon, F.-F.; Ng, L.-M.; Zhou, X.E.; West, G.M.; Kovach, A.; Tan, M.H.E.; Suino-Powell, K.M.; He, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chalmers, M.J.; et al. Molecular mimicry regulates ABA signaling by SnRK2 kinases and PP2C phosphatases. Science 2012, 335, 85–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, L.K.; Singh, N.; Pandey, G.K. Plant protein phosphatase 2C: Critical negative regulator of ABA signaling. In Protein Phosphatases and Stress Management in Plants: Functional Genomic Perspective; Pandey, G.K., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switherland, 2020; pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, W.; Shen, C.; Kang, Y.; Qin, S. PP2C-mediated ABA signaling pathway underlies exogenous abscisic acid-induced enhancement of saline–alkaline tolerance in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Plants 2025, 14, 1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghanizadeh, H.; Qamer, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, A. The multifaceted roles of PP2C phosphatases in plant growth, signaling, and responses to abiotic and biotic stresses. Plant Commun. 2025, 6, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.-H.; Li, G.; Wang, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, Z.-W.; Li, R.-Z.; Li, L.-L.; Xie, K.; Yang, Y.-Y.; Tian, R.-M.; et al. Telomere-to-telomere, gap-free genome of mung bean (Vigna radiata) provides insights into domestication under structural variation. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhae337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, K.-H.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.-L.; Shi, T.-L.; Liu, D.; Yang, Y.; Cong, Y.; Li, R.; Pu, Y.; Gong, Y.; et al. Telomere-to-telomere genome assemblies of cultivated and wild soybean provide insights into evolution and domestication under structural variation. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gebali, S.; Mistry, J.; Bateman, A.; Eddy, S.R.; Luciani, A.; Potter, S.C.; Qureshi, M.; Richardson, L.J.; Salazar, G.A.; Smart, A.; et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 47, D427–D432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Chen, H.; He, Y.; et al. TBtools-II: A “one for all, all for one” bioinformatics platform for biological big-data mining. Mol. Plant 2023, 16, 1733–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgar, R.C. Muscle5: High-accuracy alignment ensembles enable unbiased assessments of sequence homology and phylogeny. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.-T.; Schmidt, H.A.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2014, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; DeBarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.-h.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzywinski, M.; Schein, J.; Birol, I.; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Bowers, J.E.; Wang, X.; Ming, R.; Alam, M.; Paterson, A.H. Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 2008, 320, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Le, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, F. SeqKit: A cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiao, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Wang, X.; Dai, L. ParaAT: A parallel tool for constructing multiple protein-coding DNA alignments. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 419, 779–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0: A toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2010, 8, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME Suite: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A.; Bo, Y.; Han, L.; He, J.; Lanczycki, C.J.; Lu, S.; Chitsaz, F.; Derbyshire, M.K.; Geer, R.C.; Gonzales, N.R.; et al. CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 45, D200–D203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescot, M.; Déhais, P.; Thijs, G.; Marchal, K.; Moreau, Y.; Van de Peer, Y.; Rouzé, P.; Rombauts, S. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 325–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.-Z.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.-Y.; Li, L.-L.; Wang, Z.-W.; Song, F.-J.; Jia, K.-H.; Li, N.-N.; Chu, P.-F. Transcriptome profiling across 11 different tissues in Pisum sativum. BMC Genom. Data 2025, 26, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2023, 2, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantalapiedra, C.P.; Hernández-Plaza, A.; Letunic, I.; Bork, P.; Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: Functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2021, 38, 5825–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, T.; Hu, E.; Xu, S.; Chen, M.; Guo, P.; Dai, Z.; Feng, T.; Zhou, L.; Tang, W.; Zhan, L.; et al. clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2021, 2, 100141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Sun, X.; Guo, Z.; Joldersma, D.; Guo, L.; Qiao, X.; Qi, K.; Gu, C.; Zhang, S. Genome-wide identification and evolution of the PP2C gene family in eight Rosaceae species and expression analysis under stress in Pyrus bretschneideri. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 770014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, B.; Song, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, M.; Qin, Z.; Li, D.; Li, S.; et al. Genome-wide identification of the PP2C gene family and analysis of its expression profiling in response to cold stress in wild sugarcane. Plants 2023, 12, 2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharana, K.C.; Venancio, T.M. Polyploidization events shaped the transcription factor repertoires in legumes (Fabaceae). Plant J. 2020, 103, 726–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umezawa, T.; Nakashima, K.; Miyakawa, T.; Kuromori, T.; Tanokura, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. Molecular basis of the core regulatory network in ABA responses: Sensing, signaling and transport. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 1821–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, J.; Dupeux, F.; Betz, K.; Antoni, R.; Gonzalez-Guzman, M.; Rodriguez, L.; Márquez, J.A.; Rodriguez, P.L. Structural insights into PYR/PYL/RCAR ABA receptors and PP2Cs. Plant Sci. 2012, 182, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bono, M.; Rivera-Moreno, M.; Albert, A.; Rodriguez, P.L. Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation-mediated regulation of ABI1/2 activity and stability for fine-tuning ABA signaling. Mol. Plant 2025, 18, 1103–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Y.-S.; Javed, T.; Liu, T.-T.; Ali, A.; Gao, S.-J. Mechanisms of abscisic acid (ABA)-mediated plant defense responses: An updated review. Plant Stress 2025, 15, 100724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Pri-Tal, O.; Michaeli, D.; Mosquna, A. Evolution of abscisic acid signaling module and its perception. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).