Abstract

Invasive species are a recurring global problem, and the water hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes) is a well-known example. Various strategies have been explored to manage its spread, including its use as an agricultural amendment. However, when P. crassipes biomass is incorporated into soil and undergoes degradation, it may increase soil conductivity and promote metal leaching, potentially affecting soil biota, particularly microbiota. Saprophytic fungi play a key role in the decomposition and renewal of organic matter, and their resilience to stressors is crucial for maintaining soil function. Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of P. crassipes biomass extracts on the saprophytic fungus Trametes versicolor by evaluating fungal growth and metabolic changes [including sugar content, phosphatase enzymatic activity, and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production]. The fungus was exposed for 8 days to a dilution series of extracts (100%—undiluted, to 3.13%) prepared from P. crassipes biomass collected at five locations in Portuguese wetlands. Two sites were in the south, within a Mediterranean climate (Sorraia and Estação Experimental António Teixeira), and three were in the north, within an Atlantic climate (São João de Loure, Pateira de Fermentelos, and Vila Valente), representing both agricultural-runoff–impacted areas and recreational zones. Extracts were used to simulate a worst-case scenario. All extracts have shown high conductivity (≥15.4 mS/cm), and several elements have shown a high soluble fraction (e.g., K, P, As, or Ba), indicating substantial leaching from the biomass to the extracts. Despite this, T. versicolor growth rates were generally not inhibited, except for exposure to the São João de Loure extract, where an EC50 of 45.3% (extract dilution) was determined and a significant sugar content decrease was observed at extract concentrations ≥25%. Possibly due to the high phosphorous leachability, both acid and alkaline phosphatase activities increased significantly at the highest percentages tested (50% and 100%). Furthermore, ROS levels increased with increasing extract concentrations, yet marginal changes were observed in growth rates, suggesting that T. versicolor may efficiently regulate its intracellular redox balance under stress conditions. Overall, these findings indicate that the degradation of P. crassipes biomass in soils, while altering chemical properties and releasing soluble elements, may not impair and could even boost microbiota, namely saprophytic fungi. This resilience highlights the potential ecological benefit of saprophytic fungi in accelerating the decomposition of invasive plant residues and contribution to soil nutrient cycling and ecosystem recovery.

1. Introduction

Freshwater systems globally face significant challenges in maintaining ecological equilibrium, with invasive species posing major disruptions. Water hyacinth (Pontederia crassipes Mart. [Magnoliopsida: Commelinales]) has been reported as one of the most prolific aquatic species, capable, under ideal conditions, of doubling its population every 5 to 15 days [1,2]. Thriving in lentic environments such as low-flow rivers, it forms dense mats that alter hydrogeology and negatively affect native biota [3,4]. Once seen as a problem or a challenge, the biomass of P. crassipes is increasingly valued for its high lignocellulosic content [5], offering opportunities spanning agriculture, renewable energy, and environmental restoration [3,6,7,8,9]. For instance, P. crassipes biomass is rich in cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, alongside essential elements including carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and sulfur, which collectively contribute to its potential as a valuable agricultural resource, particularly in developing countries [5]. As it decomposes, P. crassipes promotes the mineralization of nutrients and organic matter turnover, thereby enhancing soil organic carbon, phosphorus, and potassium levels. This renders P. crassipes biomass effectiveness as a high-yield compost or inorganic fertilizer [10,11]. Composting remains one of the most widely used methods for producing green manure, especially in under-resourced regions of Africa and Southwest Asia [10].

Utilizing P. crassipes biomass in agriculture would have a dual purpose: mitigating its environmental impact while replenishing critical soil nutrients. However, for this plant to be used as a fertilizer, proper management is required, using criteria that respect the behaviour and interaction of the species with the environment, including its bioecology [12]. The European Commission classifies P. crassipes as an Invasive Alien Species of European Union Concern and clarifies its potential use as a fertilizer, but that must comply with waste legislation and soil remediation regulations, as well as respect the limit concentrations for metals within agricultural standards [13,14].

Several studies have documented positive effects of P. crassipes biomass amendments on soil physicochemical properties. For example, acidic soils (pH = 4) from the Pathum-Thani region of Thailand, amended with a proportion of water hyacinth-based biochar 1:8:2 biochar/soil/sand (average particle size of 0.075 mm), exhibited a significant pH increase of approximately three units (pH = 7.57), which correlated with enhanced growth performance of climbing plants such as Convolvulus sp. (Magnoliopsida: Solanales) [15]. Similarly, Masto et al. [16] reported that soil amended with water hyacinth-based biochar at 20 g/kg promoted Zea mays growth compared to unamended soil (control). Furthermore, P. crassipes incorporation into soils has been shown to promote microbial communities: Jutakanoke et al. [15] observed increased abundance and persistence of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (e.g., Bacillus, Paenibacillus, and Sphingomonas). Likewise, Umsakul et al. [17] found that compost or vermicompost containing P. crassipes enhanced microbial abundance and stimulated enzymatic activities during the decomposition phase, including cellulases, xylanases, and phosphatases.

Previous studies on the use of P. crassipes biomass in soils have predominantly focused on bacterial communities. Considering coexistence, the improved physical and chemical properties imparted by P. crassipes amendments to soils are also expected to favor the activity of saprophytic fungi. Evaluating the response of these fungi to biomass or biomass extracts derived from invasive species such as P. crassipes is particularly important given saprophytic fungi’s crucial role in the renewal and decomposition of the most recalcitrant organic matter [18,19], and this area remains underexplored in the literature. To date, and to our knowledge, research relating P. crassipes to saprophytic fungi has primarily highlighted the plant as a substrate for industrial production of hydrolytic enzymes by filamentous fungal strains such as Trichoderma harzianum, Trichoderma atroviride (Sordariomycetes), Penicillium griseofulvum, Penicillium commune, and Aspergillus versicolor (Eurotiomycetes) [20]. This approach overlooks the potential impacts on the ecological role of these fungi in soil biogeochemical cycles. Studies conducted with the phytopathogenic fungus Diplocarpon rosae (Leotiomycetes) have shown that exposure to plant-derived extracts and oils inhibits the fungal growth rate, sporulation, and protein synthesis, while increasing catalase and peroxidase enzymatic activities, which suggest induction of oxidative stress [21]. Similarly, Masto et al. [16] reported increased catalase and peroxidase activity within soil microbial communities exposed to P. crassipes biochar at 20 g/kg of soil, suggesting stress responses or altered microbial metabolism.

Given that P. crassipes acts as a metal hyperaccumulator (e.g., [22]), it is critical to rigorously investigate the potential leaching of accumulated metals during biomass decomposition and their subsequent bioavailability, especially to soil microbiota. Failure to evaluate these pathways may compromise the environmental safety of biomass applications. Current research often focuses on biochar derived from P. crassipes (e.g., [14,15,16]). However, in resource-limited contexts where fresh biomass application may prevail, it is critical to examine whether factors such as the geographic origin and intrinsic physiological variations in hyacinth populations influence their metal accumulation capacity and their ecological impacts. Without such consideration, generalizing the benefits or risks associated with P. crassipes risks overlooking site-specific variations that could significantly alter the outcomes and generalizations. Accordingly, this study aimed to evaluate the effects of P. crassipes biomass on saprophytic fungi. To this end, P. crassipes extracts from biomass collected from five different locations were tested for their impact on the growth rates of a saprophytic fungus Trametes versicolor (Basidiomycota: Agaricomycetes). Additionally, potential stress responses were assessed by measuring the enzymatic activity of phosphatases in fungal exudates, total sugar content in the biomass, and intra- and extracellular reactive oxygen species concentrations. The extracts served as surrogates for P. crassipes biomass, enabling the quantification of the soluble fraction of potentially toxic elements and easy quantification of the effects on fungal metabolism. If P. crassipes extracts do not suppress rot fungus growth and activity, then deploying rot fungi (direct inoculation, pre-composting, or co-composting) may be proposed as a well-supported strategy to accelerate degradation of P. crassipes recalcitrant components and further valorize this biomass.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pontederia Crassipes Biomass Collection and Extract Preparation

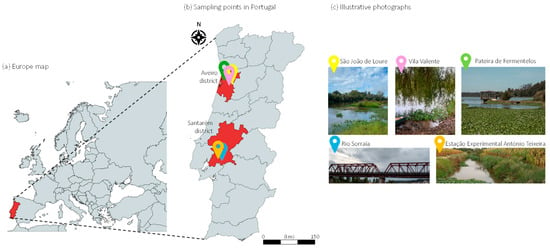

Pontederia crassipes biomass was collected from five different locations across Portugal wetlands (Figure 1) representing both Mediterranean (Coruche: Sorraia River, 38°57′ N, 8°31′ W; António Teixeira Experimental Station, Santarém, 38°56′ N, 8°30′ W) and Atlantic climates (São João de Loure, Aveiro, 40°37′ N 8°33′ W; Pateira de Fermentelos, Águeda, 40°34′ N 8°30′ W; Vila Valente, Aveiro, 40°40′ N 8°33′ W). Site selection followed the distribution and representativeness of the invasive species as documented by Portela-Pereira et al. [23] and was designed to capture a gradient of environmental conditions, including areas impacted by agricultural run-off as well as cleaner, recreational water bodies. At each site, plants were randomly collected within a 15-m radius, pooled, and kept refrigerated during transport. Only intact, non-flowering individuals (leaves, floaters, roots) free of sediments were sampled. In the laboratory, biomasses were rinsed to remove debris, dried at 40 °C to constant weight, grounded and homogenized (Qilive q.5132, 500 w, Villeneuve-d’Ascq, France). All samples were collected between 23 September and 3 October 2024, with outside temperatures ranging from 20.2 to 22.8 °C.

Figure 1.

Map showing the (a) European location of Portugal, (b) geographical location of P. crassipes sampling sites in Portugal, with (c) corresponding illustrative photographs.

The P. crassipes extracts from each site were prepared at a 1:10 ratio (mass/volume) in distilled water. The extracts were heated on a hotplate (2 to 4 h; Thermo ScientificTM Cimarec+TM Hot Plate 100–120 V, Waltham, MA, USA) at a temperature ranging from 60 °C to 80 °C to preserve sugars. After cooling, the extracts were filtered (≤0.45 µm pore size), and the pH and electrical conductivity (EC, mS/cm) were measured multiparametric with a Lovibond® Water Testing device (Dortmund, Germany), equipped with pH and EC probes. Both probes were calibrated prior to measurements using standard buffer solutions (pH 4.00, 7.00, and 10.00) and certified conductivity standards (1413 µS/cm and 12.88 mS/cm). All measurements were performed at room temperature.

2.2. Biomass and Water Extract Elemental Characterization

Biomass (washed and dried) from each of the six locations was subjected to acid digestion to extract trace elements for analysis, following a method based on US EPA 3050B and Baptista et al. [24,25]. An aliquot of 0.2 g of biomass was accurately weighed and 3 mL of concentrated nitric acid (HNO3, 65%) and let stand overnight at room temperature. The aliquots were then submitted to a temperature program in a digestion block (DigiPrep, SCP Science, Baie-d’Urfé, QC, Canada) at 85 °C for more than 120 min. After cooling to room temperature, 2 mL of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30%) was added to each sample, and the samples were reheated at 85 °C for 120 min. The acid and peroxide were evaporated at 50 °C until near dryness, and the samples were diluted to a final volume of 25 mL with 1% HNO3 solution.

Regarding the instrumental determinations, the elemental composition of both biomass digests and water extracts was analysed following methods based on ISO 17294-2:2023 [26], using an Agilent 7700 ICP-MS (Santa Clara, CA, USA) equipped with an octopole reaction system (ORS) collision/reaction cell technology to minimize spectral interferences. Germanium (72Ge), Rhodium (103Rh) and Iridium (193Ir) were used as internal standards and the calibration was established with standard solutions prepared by dilution of certified reference materials (High-Purity Standards—ISC Science, Oviedo, Spain). The analyzed elements included metals and metalloids (e.g., As, Al, Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni, Cu, Zn) as well as essential macro and micronutrients (e.g., Fe, Mn, Mg, Ca, K). Blanks and certified reference materials were treated using the same procedures, and an independent control standard was analysed to verify the calibration.

The methods’ accuracy was verified using CRM SPS-SW1 (Quality Control Material—Surface Water Level 1, lot 132, Spectrapure Inc., Tempe, AZ, USA), with recoveries between 92 and 110% (average = 99%), for water extracts, and certified reference material BCR-279 (Sea lettuce, Ulva lactuca, lot 574, JRC—Joint Research Centre, Brussels, Belgium) with recoveries between 82% and 95% for solid biomass samples. For biomass samples elemental characterization was performed in quadruplicate/triplicate for two of the samples for evaluation of homogeneity and duplicate for the remaining. Analytical precision, expressed as the relative standard deviation (RSD) of replicate analysis, was ≤20% for biomass determinations (average = 10%) and ≤10% for water extracts (average = 4%).

The soluble (or aqueous) fraction (SF, %) of each element, representing the proportion of that element that remains dissolved or readily leachable in the water extract relative to the biomass content, was calculated as follows:

where CF (concentration factor) is 100 if the concentration in the water extract is in µg/L and CF is 0.1 if the concentration in the water extract is in mg/L.

2.3. Saprophytic Fungus Choice and Maintenance

Trametes versicolor was selected as a model decomposer of lignin-rich plant biomass, including the aquatic plant species water hyacinth. Trametes versicolor is a well-studied white-rot fungus with an important ecological role in organic matter turnover in soils [18] and is sensitive to abiotic stress [27,28]. Thus, it is an appropriate representative of saprophytic fungi that is likely to be influenced by the incorporation of P. crassipes residues into the soil. Individual axenic cultures of T. versicolor were obtained from the BCCMTM/MUCL Culture Collection MUCL 30886 (Brussels, Belgium) and maintained under active growth in 90 mm Ø Petri dishes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA) containing potato dextrose agar (PDA; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The cultures were maintained at 28 °C (Cole Parmer SI-200, Cambridgeshire, UK) in the dark and renewed weekly.

2.4. Eight-Day Growth Inhibition Assay with T. versicolor

The one-week growth inhibition assays with T. versicolor exposed to serial dilutions of each of the five P. crassipes extracts generally followed the procedure described by Venâncio et al. [27] with minor adaptations regarding type of medium and biomass collection. To facilitate P. crassipes extract incorporation and since P. crassipes extract dilution of 50% and 100% compromised the solidification of agar plates (possibly due to high conductivity), the assays were adapted to be carried out using potato dextrose broth (PDB, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Dilutions were prepared with distilled water from each original extract (100%) and tested at the following percentages—100 (undiluted), 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, and 3.13%—supplemented with PDB (27 g/L). Negative controls (PDB medium only) were also included. The assay was initiated by placing a single circular 7 mm Ø agar disk collected from the edge of an actively growing culture of T. versicolor at each replicate. Three replicates, each with 30 mL, were tested for each treatment and the control. The assay lasted 8 days, and at the end, the fungal biomass was collected by filtration using a 0.45 µm pore-sized filter from the growing liquid media. The pH and electrical conductivity (mS/cm) of the exudates were determined in triplicate using a multiparametric Lovibond® Water Testing device. Both the biomass and fungal exudates were individually frozen at −80 °C. Trametes versicolor dry weight (AND HR 250 AZ, A&D COMPANY, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was determined after lyophilization. Growth rates were determined as the increase in dry biomass over the incubation period, using the difference between the final dry weight and the initial average dry weight of the 7 mm Ø agar inoculum disk, divided by the total number of days of the assay.

From T. versicolor dry biomass, sugar content and intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) were also determined (described in detail below), while soluble sugar content, phosphatase activity, and extracellular ROS were determined in the exudates (described in detail below). All materials were properly sterilized (20 min at 121 °C, 1 bar; Uniclave 88, AJC, Cacém, Portugal).

2.5. Total Carbohydrate Content

Rot fungi are known to increase extracellular secretion when exposed to hard and recalcitrant substrates [29]. This response can be characterized by changes in carbohydrate dynamics (sugar production), either through the accumulation of carbohydrates within fungal biomass or through variations in the concentration of soluble sugars and polysaccharides in the surrounding medium. To capture these changes, the total carbohydrate content was determined using the phenol–sulfuric acid method [30]. Briefly, aliquots of fungal biomass with known weights were incubated at 95 °C (Thermo ScientificTM Cimarec+TM Hot Plate 100–120 V, Hampton, NH, USA) for one hour with a 2.5 mM H2SO4 solution (CAS number 7664-93-9, 98%, Merck & Co., Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA). Subsequently, the pellet was separated from the supernatant by centrifugation for 8 min at 10,000× g at room temperature, and each was independently mixed with a 5% phenol solution (CAS number 108-95-2, ≥99.5%, Merck & Co., Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA), followed by rapid addition of concentrated sulfuric acid (CAS number 7664-93-9, 95.0–98.0%, Merck & Co., Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA). After incubation at room temperature, the reaction developed a stable orange–yellow color, which was measured spectrophotometrically at 492 nm (Multiskan Microplate Photometer, Thermo Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA). Glucose (0.05, 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, and 0.25 µg/mL) was used as a standard to generate a standard calibration curve, and the results are expressed as glucose equivalents (µg/mL).

2.6. Phosphatase Enzymatic Activity Determination

The method for determining phosphatase activity was described by Eivazi and Tabatabai [31]. The disodium 4-nitrophenyl phosphate (1 mg/mL; CAS number 333338-18-4, high purity, Merck & Co., Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) substrate was dissolved in universal buffer with pH adjusted to 6 or 11 (5 M sodium hydroxide solution) for acid or alkaline phosphatase determination, respectively. Exudates were incubated with the substrate (proportion 1:1) for 1 h at 37 °C (Cole Parmer SI-200, Cambridgeshire, UK). At the end of this period, the samples were centrifuged to 10,000× g for 8 min at room temperature and the absorbance was measured at 492 nm (Multiskan Microplate Photometer, Thermo Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA). A blank was used solely with PDB to correct for possible medium interference on readings. The concentrations of acid and alkaline phosphatase in the samples (expressed as µg p-NP/hour/mL) were determined according to the respective calibration curves using p-nitrophenol (p-NP; CAS number 100-02-7, high purity, Merck & Co., Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) as a standard (10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, and 70 µg p-NP/mL for acid phosphatase and 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 µg p-NP/mL for alkaline phosphatase).

2.7. Intra- and Extracellular Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Determination

ROS production is characteristic of normal cellular metabolism; however, changes in their production may be correlated with stress exposure [32]. ROS production was analyzed in both fungal biomass (intracellular concentration) and exudates (extracellular), as fungi tend to secrete materials outside. For intracellular ROS determination, fungal biomass samples were homogenized (3 cycles of 30 s, intercalated with 1 min on ice) with a buffer solution (K2HPO4, pH = 7) and subsequently centrifuged (10,000× g, 4 °C; Thermo ScientificTM MegafugeTM, Hampton, NH, USA) to obtain the supernatant. For extracellular ROS determination, the previously collected and filtered exudate was used [33].

One mL of biomass supernatant or exudate was incubated, for 30 min in the dark with a 25 nM solution of the 2′7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; CAS number 2044-85-01, high purity, Merck & Co., Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) [29]. The DCFH-DA is a non-fluorescent dye that becomes highly fluorescent upon contact with ROS. The samples were read at a wavelength of 525 nm (Multiskan Microplate Photometer, Thermo Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA), and the values were converted to µg/mL of H2O2 equivalents. For this purpose, a calibration curve was previously prepared using H2O2 as a standard (0, 0.0034, 0.034, 0.085, and 0.34 µg/mL).

2.8. Data Analysis

Whenever possible, P. crassipes extract dilution percentages provoking X% of effect (ECx) in fungal growth rate were computed through a non-linear regression analysis by fitting a logistic model using the program Statistica for Windows 4.3 (StatSoft, Aurora, CO, USA). Additionally, statistical differences between dilutions and control were determined through a one-way ANOVA, followed by the Dunnett’s multi-comparison test (p ≤ 0.05). All data sets were previously transformed and checked for compliance with normality and homoscedasticity assumptions.

3. Results

3.1. Bioavailable Fraction of Macro- and Micronutrients (MaN and MiN) and Potentially Toxic Elements (PTE)

The elemental analysis of P. crassipes biomasses and their respective water extracts are presented in detail in Table 1, and the determined soluble fractions are summarized in Table A1.

Table 1.

Concentrations of the macronutrients (MaN), micronutrients (MiN), and potentially toxic elements (PTE) in Pontederia crassipes biomasses (dry weight) collected in five different locations, and the concentrations of the same elements in the respective water extracts.

Macronutrients such as K, Ca, and Mg were the most abundant elements in all analyzed biomasses. Biomasses from Estação and Vila Valente confirmed strong accumulation capacity of K and P, reaching concentrations above 32,000 mg/kg of K and around 1400 mg/kg for P (Table 1). However, the correspondent water extracts exhibited much lower absolute concentrations of macronutrients, although P and K remained the most soluble elements, with P reaching about 52,000 µg/L and K above 2000 mg/L in the extracts (Table 1). Na was not the most present element; however, it was joint with K, one of the elements showing the highest solubility (ranging from 47.8% in Estação up to 85.2% in Sorraia; Table A1). The macroelement Mg and the PTE Ni showed moderate solubility (19–44%), while elements like Fe, Zn, Cr, and Cu (<10%) remained largely insoluble, suggesting a potential higher retention in biomass (Table A1).

Regarding the PTEs, elements such as As, Ba, and Rb were more prominent in the water extracts than in the correspondent biomasses (Table 1). The extracts from Estação and Vila Valente exhibited particularly elevated levels of As, while those from Pateira and Vila Valente showed higher concentrations of Rb. These results indicate a predominance of soluble or exchangeable forms, which resulted in soluble fraction percentages ranging between 31% and 62% for RB, and between 8% and 22% for As, although Ba remained largely insoluble (<5%; Table A1). Other elements like Pb, Al, and Cr were less represented in the water extracts than in the solid biomass, consistent with their low solubility (≤5% for Cr, and ≤1% for As and Pb; Table A1). As the expressions of concentration differ between matrices (mass/volume for extracts vs. mass/mass for biomass), these comparisons are interpreted as indicative of relative trends rather than direct quantitative relationships.

3.2. Physico-Chemical Parameters

The physico-chemical parameters of the raw P. crassipes extracts and of the media collected at the end of the assay with T. versicolor are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Electrical conductivity (mS/cm) and pH at the end of the 8-day assay with the saprophytic fungus Trametes versicolor exposed to serial dilutions of Pontederia crassipes water extracts performed with Pontederia crassipes biomass collected from five distinct locations. Values are the averages of three replicates. Additionally indicated are the physico-chemical parameters of raw extracts and the 100% extract at the beginning of the assay. * indicates statistically different from the respective control (0%) (Dunnet, p < 0.05).

The raw extracts’ pH varied from slightly acidic (5.30 in Pateira extract) to slightly basic (8.13 in Sorraia extract), but all had high conductivity values (ranging from 15.4 mS/cm in the Sorraia extract to 22.2 mS/cm in the Vila Valente extract; Table 2). In general, the pH and conductivity decreased slightly when PDB salts were added to the extract (Table 2).

At the end of the assay, the largest decrease in pH was observed in the Sorraia extract (7.41 to 5.65 in 100% extract; Table 2). Conductivity also decreased in general, with the highest drop in Vila Valente extract (from 17.8 to 9.23 mS/cm), and the smallest decrease range for São João de Loure (~5.3 mS/cm) (Table 2). Within the range tested (3.13 to 100%), all conductivities were significantly different from the control conditions, except for the 3.13% dilution with Estação and Vila Valente extracts (Table 2). Regarding pH, there was a significant dilution-dependent effect for Sorraia (6.25% dilution onwards), Vila Valente (12.5% dilution onwards), and São João de Loure (25% dilution onwards; Table 2). Despite site-specific variations, the overall trend was that pH slightly decreased, and conductivity increased with increasing extract concentration (from 3.13 to 100%; Table 2).

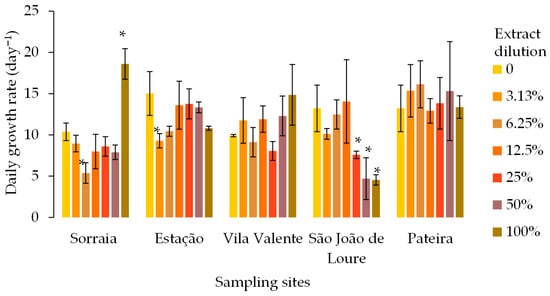

3.3. Trametes versicolor Growth Rate

The average growth rates of T. versicolor after exposure for one week to P. crassipes extracts from five sampling sites are shown in Figure 2. Overall, no dose–response pattern was observed, except for T. versicolor exposed to the extract from P. crassipes collected in São João de Loure. The growth rates of T. versicolor differed at different sites and dilutions. The growth rate of T. versicolor showed a similar pattern in extracts from Sorraia and Estação, except at the 100% extract (undiluted): it decreased at the lowest dilution percentages, although only significantly at 6.25% and 3.13%, respectively, and then increased again to levels similar (Estação) or significantly higher (Sorraia) than the control treatment. The growth rates decreased significantly when exposed to P. crassipes biomass extracts collected in São João de Loure at 25%, 50%, and 100%. This was the only case in which it was possible to determine a growth rate EC50 of 45.3% of extract dilution, with the respective 95% confidence interval between 14.3% and 76.3% of extract dilution.

Figure 2.

Average growth rate (day−1) of the saprophytic fungus Trametes versicolor after 8 days exposed to different dilutions of Pontederia crassipes water extracts (%). The vertical lines represent the standard deviation of n = 3. * represent statistical differences between the respective dilution and the control (no extract) within each of the sampling sites (Dunnet, p < 0.05).

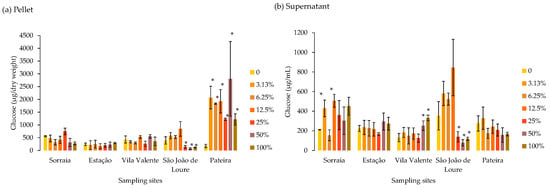

3.4. Total Carbohydrate Content

The sugar content in biomass and the content of soluble sugar of T. versicolor after exposure to the different extracts are presented in Figure 3a and Figure 3b, respectively. Exposure to a range of dilutions of P. crassipes extracts harvested in Sorraia, Estação, and Vila Valente did not induce any significant change in the sugar concentrations determined in T. versicolor biomass. However, in T. versicolor biomass exposed to P. crassipes extracts from São João de Loure and Pateira, two contrasting scenarios were observed: the sugar concentration in the biomass decreased significantly in the São João de Loure extract dilutions of 25% to 100% compared to the control, while it was significantly higher in all Pateira extract dilutions compared to the control treatment (Figure 3a). Regarding soluble sugars (determined in the supernatant), there were no changes recorded in Estação and Vila Valente, while in Sorraia, there were only significant changes compared to the control at percentages of 3.13% and 12.5% (Figure 3b). For Vila Valente and São João de Loure, the highest number of significant changes were recorded: the concentration of soluble sugars in the supernatant was significantly higher than that in the control in 50% and 100% Vila Valente extract, while it was significantly lower than that in the control in dilutions of 25%, 50%, and undiluted (100%) Pateira extract (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

Average sugar content (glucose) in biomass (µg/g dry weight) (a) and soluble sugars (µg/mL) (b) of the saprophytic fungus Trametes versicolor after 8 days exposed to different dilutions of Pontederia crassipes water extracts (%). The vertical lines represent the standard deviation of n = 3. * represents statistical differences between the respective dilution and the control (no extract) within each of the sampling sites (Dunnet, p < 0.05).

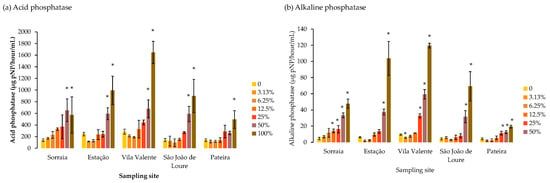

3.5. Phosphatases Enzymatic Activity Determination

The activities of acid and alkaline phosphatases are shown in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, respectively. The activity of both enzymes followed a dose-dependent pattern, increasing with decreasing dilution. All P. crassipes extract dilutions of 50% and 100% significantly increased T. versicolor acid phosphatase compared to the control, except for the Pateira extract, in which this tendency was only observed at 100% extract (Figure 4a). This fold difference between 100% extract and the respective control was the highest for the Vila Valente extract and the lowest for the Pateira extract (Figure 4a). For alkaline phosphatase, significant enzymatic induction was also observed for 50% and 100% dilutions of Estação and São João de Loure extracts but started to be significantly higher at higher dilution percentages in Sorraia (12.5%) and Pateira (25%) (Figure 4b). In Vila Valente extracts, T. versicolor alkaline phosphatase activity was significantly lower at 3.13% extract dilution compared to the control, but significantly higher than the control at 25% dilution to undiluted (100%) extract (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Phosphatase enzymatic activity (µg p-NP/hour/mL) in the exudate of the saprophytic fungus Trametes versicolor grown for 8 days exposed to different dilutions of Pontederia crassipes water extracts (%). The vertical lines represent the standard deviation of n = 3. * represent statistical differences between the respective dilution and the control (no extract) within each of the sampling sites (Dunnet, p < 0.05).

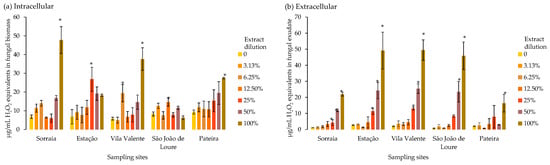

3.6. Intra- and Extracellular ROS Determination

Intra- and extracellular ROS levels increased with extract concentration across all biomasses (Figure 5a and Figure 5b, respectively). Trametes versicolor exposed to Sorraia and Vila Valente 100% extract dilutions presented the highest biomass ROS accumulation compared to the control, while São João de Loure extract induced the lowest production of ROS in T. versicolor biomass (Figure 5a). Higher extract dilutions (12.5 and 25% in Vila Valente and São João de Loure) induced significant ROS production compared to the controls, indicating that oxidative stress was triggered well before the full-strength extracts. Extracellular ROS production increased significantly at extract percentages ≥ 25% for Sorraia, Estação, and Vila Valente, while it was ≥50% and 100% for São João de Loure and Pateira, respectively (Figure 5b). The lowest extracellular ROS levels were observed in T. versicolor exposed to Pateira extract (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Concentrations of intra- and extracellular reactive oxygen species (µg/mL H2O2 equivalents) in biomass and exudate of the saprophytic fungus Trametes versicolor grown for 8 days exposed to different dilutions of Pontederia crassipes water extracts (%). The vertical lines represent the standard deviation of n = 3. * represent statistical differences between the respective dilution and the control (no extract) within each of the sampling sites (Dunnet, p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

The objective of this study was to characterize the solubility of Pontederia crassipes (water hyacinth) biomasses and the elemental composition of their aqueous extracts from different aquatic environments, and to evaluate their effects on the growth, metabolic activity, and oxidative stress responses of the ligninolytic fungus Trametes versicolor. This approach aimed at determining the potential ecological compatibility and biotransformation capacity of this fungal species when exposed to nutrient- and metal-rich aquatic plant residues, providing insight into whether rot fungi could facilitate the degradation of recalcitrant macrophyte biomass and thus contribute to organic matter cycling or whether these soil processes could be hampered by their presence.

Across all sampling sites, P. crassipes biomass exhibited a consistent pattern of macronutrient accumulation, particularly for K, Ca, and Mg levels. In contrast, P. crassipes extracts were richer in more mobile elements, such as P (up to 23% of soluble fraction), Mn, K (ranging from 45 to 68% of soluble fraction), As, and Rb. These findings reinforce the plant’s ability to store nutrients of agronomic value (N, K, and Ca), supporting its repurposing as a potential organic fertilizer [34,35,36]. For example, Datta et al. [37] reported that a 65-day sun-dried P. crassipes compost met India’s fertilizer control standards, showing ranges of 5365–8323 mg/kg for N, 2893–4014 mg/kg for P, and 4097–4792 mg/kg for K [37]. The higher solubility and mobility of certain trace elements observed in this study are supported by previous works showing a higher incidence of elements such as P and N after crop biomass residue addition to agricultural soils (e.g., [38,39,40]). The increased incidence of some potentially toxic elements in water extracts may arise from the hyperaccumulator and phytoremediation behaviour of water hyacinths [41,42,43] but may also be influenced by the presence of other elements in the biomass that stimulate their leachability. For instance, the presence of higher concentrations of phosphate ions in soils was found to promote the mobility of large fractions of previously “non-leachable” As, although this relationship is dependent on (not exclusively) soil type, P dose, and organic matter content [44,45]. These findings may raise concerns about nutrient losses (eutrophication of nearby water bodies) and the long-term safety of using P. crassipes residues in soils [8].

Elemental concentrations varied among sampling sites, with Estação and Vila Valente exhibiting the highest overall nutrient and metal levels, suggesting greater anthropogenic input or nutrient-rich conditions, whereas Pateira exhibited the highest soluble P but comparatively low metal contents. These differential accumulation patterns reflect local water quality and pollution histories, confirming that the composition of P. crassipes mirrors their habitat and may serve as a bioindicator of environmental conditions [5]. It is very likely that the high electrical conductivity (EC) measured in the extracts resulted from the leaching of these ions. Previous studies have reported P. crassipes behaviour in absorbing and releasing elements into aqueous solutions [46]. The strongest ionic contributions were found in Vila Valente and São João de Loure extracts (22.2 and 19.3 mS/cm, respectively), while Sorraia exhibited the lowest value, reflecting lower pollutant loads. Similar conductivity increases were reported when water-hyacinth-based biochar was mixed with soils (0.25:10–1:10 biochar/soil), where EC rose from 0.42 to 3.55 mS/cm compared with that of the control soil [15].

Given these high EC levels, it was important to evaluate whether ionic strength and soluble elements affected fungal physiology. Exposure of T. versicolor to P. crassipes extracts did not produce a consistent dose–response pattern in the fungus growth rates. A significant growth inhibition dilution causing 50% of effect on growth rates (EC50 ≈ 45.3% dilution) was determined only for São João de Loure extracts, while other extracts (Sorraia, Estação) caused mild inhibition at low concentrations, followed by low-dose inhibition in the lowest dilutions. Although there are few studies on the potential effects of P. crassipes extracts on the growth rates of rot fungi, other studies have reported that small increments in soil EC induced by P. crassipes biomass addition are beneficial to plant growth. Masto et al. [16] assessed Z. mays germination percentage and growth in soils amended with water hyacinth-based biochar. The authors found that maize germination percentages increased from 78% in control to 100% at 20 g/kg of P. crassipes biochar, while plant shoot and root lengths increased from 22 to 33 cm and from 15.7 to 20.2 cm, respectively, and the overall plant weight was improved at the same application rate [16]. Nevertheless, soil EC did not surpass 1 mS/cm at the highest application rate of 20 mg/kg [16], which is far from the extract conductivity measured herein.

Specifically for rot fungi, the literature highlights the ability of rot fungi to cope with high conductivity or metal levels, which aligns with the results for the growth rates obtained in this study. When exposed to increased conductivities of natural seawater for 8 days, T. versicolor reduced its growth rate by half solely at conductivity levels as high as 34.1 mS/cm (almost three quarters of seawater), with slight changes in exopolysaccharide production [27]. Others have also reported that enhanced enzymatic activities were consistent with the extracellular production of proteins in response to the presence of recalcitrant P. crassipes biomass [20]. In this study, the soluble sugar content was significantly higher in Vila Valente and São João de Loure extracts with decreasing extract dilution, which may be a response to the conductivity of the extract. Nonetheless, it must be highlighted that the use of PDB may mask some extract-specific physicochemical effects, and that the use of a defined minimal medium would provide clear conclusions on the contributions of the hyacinth extract itself to pH, EC, and fungal responses. Similarly, in another study, the authors found that Schizophyllum commune adapted well to salt conditions, grew best at 5 g NaCl/L, and maintained about half of its maximum growth rate even under hypersaline conditions [47]. However, in field studies with non-saline to severely saline soils (conductivities ranging from 0.32 to 3.76 mS/cm), it was found that soil fungal α-diversity decreased with increasing soil salinity, but the difference between non-saline and lightly salinity soils was negligible. In fact, light-salinity soils promoted the appearance of phosphorous-solubilizing species, which could improve phosphorus utilization efficiency and nutrient conditions in slightly saline soils [48].

White-rot fungi, such as T. versicolor, may also display remarkable tolerance to metals and metalloids owing to a combination of cell wall binding, chelation, and oxidative stress regulation. For instance, exposure of a wild strain of T. versicolor to 80 mg As/L did not cause a significantly delayed growth rate, possibly due to the induction of the antioxidant system. The same study reported that at this level of the metalloid, the fungus catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione were enhanced by 1.10, 1.09, and 20.47 times, respectively, compared to the non-exposed fungus group [49]. The activity levels of these three enzymes (catalase, superoxide dismutase, and glutathione) provide indirect indicators of intracellular ROS status. In the present study, ROS generation increased with increasing extract concentrations and was detected upon exposure to all P. crassipes extracts, with the highest incidence in T. versicolor biomass exposed to Sorraia and Vila Valente water extracts (correlating with high soluble metals/ions) and the lowest in Pateira. Nevertheless, fungal growth rates were only marginally affected, suggesting that T. versicolor efficiently regulates intracellular redox balance, likely through the activation of a similar antioxidant mechanism. (e.g., [50,51]). This tolerance is consistent with the reported resilience of white-rot fungi to stressors, such as metals or metalloids. For instance, when supplementing the culture medium with 127 mg Cu/L, T. versicolor laccase production increased by 12-fold compared to that in control cultures [52]. In field studies, Agraricus campestris was found to be the most accumulator among ten other saprophytic fungi species of metals like Ni (3.62 mg/kg dry weight), Cr (3.01 mg/kg dry weight), and Cd (2.67 mg/kg dry weight) [53]. Although ROS accumulation may be often associated with oxidative stress (and thus, inhibitory effects), in many wood-decaying fungi, ROS are not merely stress indicators but essential agents in lignocellulose degradation, generated through enzyme-driven radical processes. Both white-rot and brown-rot fungi can produce significant levels of extracellular ROS during biomass breakdown, meaning that high ROS production can occur without growth inhibition [54,55].

The induction of acid and alkaline phosphatases at higher extract concentrations suggests the activation of phosphate metabolism and general stress responses. Ramdas et al. [56] studied the effects of the addition of several organic amendments and verified that the amendment consisting of a mixture of paddy straw and P. crassipes induced the highest phosphatase activity, possibly related to the mineralization of phosphorus present in the P. crassipes biomass [56]. In this study, Pateira biomass extracts caused the weakest enzymatic induction, possibly due to their lower potentially toxic element (PTE) content or more balanced nutrient profile. However, the overall results indicate that T. versicolor maintained its metabolic flexibility under chemically complex conditions, supporting its potential role in the partial degradation of nutrient-rich aquatic biomass and a particularly important tool for enhancing phosphorus availability.

In summary, the tolerance of T. versicolor to the chemical complexity of P. crassipes extracts underscores its ecological resilience and biotechnological relevance. The ability of this fungus to grow and regulate oxidative stress under high-ionic and metal-rich conditions suggests that ligninolytic fungi can actively participate in the biodegradation of this invasive species. Integrating fungal-assisted decomposition into the circular bioeconomy framework proposed by Datta et al. [37] strengthens the case for converting the P. crassipes “menace” into a renewable agricultural asset. Such approaches enhance nutrient recovery, mitigate inefficient phosphorus turnover in poor soils, and support low-cost, sustainable organic amendments for rural agroecosystems. Nevertheless, the analysis of other metabolic pathways would help to further elucidate the coping mechanisms enabling fungal adaptation to these chemically complex environments.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study highlight the potential of P. crassipes as an agricultural fertilizer without further prejudice for the rot fungi T. versicolor; however, this must always be accompanied by the need for elemental characterization, particularly regarding potentially toxic elements (PTEs) and mobile macroelements such as phosphorus.

Despite the load of some PTEs in the water extracts, these induced marginal reductions in the growth rates of the fungus T. versicolor, except for the extract made with biomass collected in São João de Loure, for which an EC50,8days of 45.3% was calculated. The maintenance or increase in fungal biomass was mainly accompanied by increased phosphatase activity (acid and alkaline), indicating a potential adjustment to nutrient-rich environments (simulating decomposed aquatic macrophytes). Furthermore, the activation of oxidation mechanisms (assessed by ROS production) with minimal effects on fungal growth rates reinforces the overall metabolic adjustment and resilience of this fungus to metal(loid)s inputs.

This study reinforces the hypothesis that ligninolytic fungi can contribute to the degradation and recycling of nutrient-rich macrophyte residues, such as P. crassipes, in soils or composting systems. However, it is important to note that translating these extract-level responses into actual soil organic matter cycling requires caution. Overall, these findings suggest that, although the high solubility of some elements and conductivity may limit the direct application of untreated residues to soil, P. crassipes biomass can greatly benefit from fungal pretreatment, representing a promising technique for application in sustainable agricultural systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.V. and C.P.; methodology, C.V., A.R. and P.P.; validation, C.V., A.R., P.P. and C.P.; investigation, C.V., A.R., P.P. and C.P.; resources, C.V. and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, C.V. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, C.V., A.R., P.P. and C.P.; supervision, C.V.; funding acquisition, C.V. and C.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the financial support to UID Centro de Estudos do Ambiente e Mar (CESAM) + LA/P/0094/202 and GEOBIOTEC (UIDB/04035), to FCT/MEC through national funds for financing the project “Ph-uel: meeting agricultural soil Phosphorous reqUirements by biomass transformation and valorization of the invasivE water hyacinth: a circuLar system-thinking” (Ref. 2023.15713.PEX), to the LabEx DRIIHM—Dispositif de Recherche Interdisciplinaire sur les Interactions Hommes-Milieux and OHMI—Observatoire Hommes-Millieux International Estarreja for funding the project “CHOICES—When CHallenges met Opportunities: water hyaCinth invasions as potential agricultural enhancers for EStarreja’s agricultural soils”, and the project “LIFT—LeveragIng rot Fungi potential for the rehabiliTation of degraded soils: from mechanisms of action to field-case effectiveness (Reference 2023.18428.ICDT, COMPETE2030-FEDER-00814600, SGO2030: 16864).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Soluble fraction (%) of elements determined based on the ratio between the concentrations of elements in the water extracts and the concentrations of elements in Pontederia crassipes biomass. n.d.—not determined, below detection limits in one the samples (biomass or water).

Table A1.

Soluble fraction (%) of elements determined based on the ratio between the concentrations of elements in the water extracts and the concentrations of elements in Pontederia crassipes biomass. n.d.—not determined, below detection limits in one the samples (biomass or water).

| MaN and MiN | Sorraia | Estação | Vila Valente | São João de Loure | Pateira |

| Mn (%) | 3 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Mg (%) | 38.4 | 28.4 | 19.0 | 21.1 | 21.3 |

| Ca (%) | 5.83 | 4.29 | 4.19 | 1.85 | 4.06 |

| Na (%) | 85.2 | 47.8 | 70.0 | 52.0 | 62.8 |

| Fe (%) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Zn (%) | 0 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| K (%) | 64.1 | 45 | 49.1 | 47.6 | 67.5 |

| Ni (%) | 44.0 | 78 | 53 | 21 | 33 |

| Co (%) | 6 | 19 | 19 | 7 | 9 |

| Mo (%) | 9 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 11 |

| P (%) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 23 |

| Cu (%) | 1 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| B (%) | 21 | 16 | 18 | 19 | 21 |

| PTE | Sorraia | Estação | Vila Valente | São João de Loure | Pateira |

| Ba (%) | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Li (%) | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| V (%) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| As (%) | 8 | 22 | 18 | 10 | 15 |

| Sb (%) | 10 | 17 | 9 | 6 | 12 |

| Cr (%) | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Sn (%) | 4 | 25 | 6 | 10 | 1 |

| Pb (%) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| U (%) | 2 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Al (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Rb (%) | 31 | 40 | 50 | 46 | 62 |

| Cd (%) | n.d. | 8 | 1 | 0 | n.d. |

| W (%) | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Ti (%) | n.d. | n.d. | 15 | 8 | 3 |

References

- Auma, E.; Peter, O.; Ndiba, K.; Gikuma, P. Characterization of water hyacinth (E. crassipes) from Lake Victoria and ruminal slaughterhouse waste as co-substrates in biogas production. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njogu, P.; Kinyua, R.; Muthoni, P.; Nemoto, Y. Biogas production using water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for electricity generation in Kenya. Energy Power Eng. 2015, 7, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bote, M.A.; Naik, V.R.; Jagadeeshgouda, K.B. Review on water hyacinth weed as a potential bio fuel crop to meet collective energy needs. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2020, 3, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retnamma, J.; Sarath, S.; Balachandran, K.K.; Krishnan, S.S.; Karnan, C.; Arunpandi, N.; Alok, K.T.; Ramanamurty, M.V. Environmental and human facets of the waterweed proliferation in a Vast Tropical Ramsar Wetland-Vembanad Lake System. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, E.; Arthur, R.; Agyemang, E.; Baidoo, M.; Asiedu, N. Experimental simulation and kinetic modeling of bioenergy potential of Eichhornia crassipes biomass from the Volta River basin of Ghana under mesophilic conditions. Sci. Afr. 2023, 23, e02032. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, S.H.; Song, W.; Guo, J.Y. Advances in management and utilization of invasive water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) in aquatic ecosystems—A review. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2017, 37, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, F.; Sequeira, I.; Geraldes, H.; Anastácio, P. Espécies Aquáticas que Estão a Invadir Portugal; Projeto LIFE-INVASAQUA; MARE–Centro de Ciências do mar e do Ambiente: Évora, Portugal; Wilder-Rewilding Your Days: Évora, Portugal; Universidade de Évora: Évora, Portugal, 2023; pp. 120–129. [Google Scholar]

- Canning, A. A Review on Harnessing the Invasive Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for Use as an Agricultural Soil Amendment. Land 2025, 14, 1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherwoo, L.; Kumar, S.; Das, S.; Datta, A.; Verma, S.; Prabhu, N.G.; Oo, H.N.; Sharma, A.; Bhondekar, A.P. Transforming aquatic weeds into resources: Pontederia crassipes, water hyacinth mining for circular bioeconomy. Environ. Manag. 2025, 75, 2458–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, A.; Aggarwal, N.; Saini, A.; Yadav, A. Beyond Biocontrol: Water hyacinth- opportunities and challenges. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 26–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, W.; Sun, Q.; Xia, M.; Wen, Z.; Yao, Z. The resource utilization of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes [Mart.] solms) and its challenges. Resources 2018, 7, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigermal, H.; Assefa, F. Impact of the Invasive water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) on Socio-Economic Atributes. J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2019, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Proposal for a Council and European Parliament Regulation on the Prevention and Management of the Introduction and Spread of Invasive Alien Species; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2013; 148p, Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX%3A52013SC0321 (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Kassa, Y.; Amare, A.; Nega, T.; Alem, T.; Gedefaw, M.; Chala, B.; Freyer, B.; Waldmann, B.; Fentie, T.; Mulu, T.; et al. Water hyacinth conversion to biochar for soil nutrient enhancement in improving agricultural product. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jutakanoke, R.; Intaravicha, N.; Charoensuksai, P.; Mhuantong, W.; Boonnorat, J.; Sichaem, J.; Phongsopitanun, W.; Chakritbudsabong, W.; Rungarunlert, S. Alleviation of soil acidification and modification of soil bacterial community by biochar derived from water hyacinth Eichhornia crassipes. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Masto, R.E.; Kumar, S.; Rout, T.K.; Sarkar, P.; George, J.; Ram, L.C. Biochar from water hyacinth (Eichornia crassipes) and its impact on soil biological activity. Catena 2013, 111, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umsakul, K.; Dissara, Y.; Srimuang, N. Chemical, physical and microbiological changes during composting of the water hyacinth. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 13, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, S.; Six, J.; Elliot, E. Reciprocal transfer of carbon and nitrogen by decomposer fungi at the soil-litter interface. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 1001–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Meng, B.; Rudgers, J.; Chui, N.; Zhao, T.; Chai, H.; Yang, X.; Sterneberg, M.; Sun, W. Disruption of fungal hyphae suppressed litter-derived C retention in soli and N translocation to plants under drought-stressed temperate grassland. Geoderma 2023, 432, 116395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana-Cuenca, A.; Tovar-Jiménez, X.; Favela-Torres, E.; Perraud-Gaime, I.; González-Becerra, A.E.; Martínez, A.; Moss-Acosta, C.L.; Mercado-Flores, Y.; Téllez-Jurado, A. Use of water hyacinth as a substrate for the production of filamentous fungal hydrolytic enzymes in solid-state fermentation. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.M.; Schwan-Estrada, K.R.F.; Jardinetti, V.D.A.; Oliva, L.S.D.C.; Silva, J.B.D.; Scarabeli, I.G.R. Atividade fungitóxica de extratos vegetais e produtos comerciais contra Diplocarpon rosae. Summa Phytopathol. 2016, 42, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgali, P.; Palimkar, S.; Adhikari, A.; Patel, R.; Routh, J. Remediation of potentially toxic elements-containing wastewaters using water hyacinth—A review. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 2023, 25, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portela-Pereira, E.; Araújo, P.V.; Clamote, F.; Carapeto, A.; Almeida, J.D.; Correia, M.J.; Schwarzer, U.; Pereira, P.; Gomes, C.T.; Clemente, A.; et al. Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms—Mapa de distribuição. In Flora-On: Flora de Portugal Interactiva; Sociedade Portuguesa de Botânica: Alverca do Ribatejo, Portugal, 2025; Available online: http://www.flora-on.pt/#wEichhornia+crassipes (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Method 3050B: Acid Digestion of Sediments, Sludges, and Soils (Revision 2); U.S. EPA, Office of Solid Waste: Washington, DC, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baptista, C.J.; Seixas, F.; Gonzalo-Orden, J.M.; Patinha, C.; Pato, P.; da Silva, E.F.; Casero, M.; Brazio, E.; Brandão, R.; Costa, D.; et al. The first full study of heavy metal(loid)s in western-European hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) from Portugal. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 11983–11994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 17294-2:2023; Water Quality—Application of Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)—Part 2: Determination of Selected Elements Including Uranium Isotopes. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Venâncio, C.; Pereira, R.; Freitas, A.; Rocha-Santos, T.; da Costa, J.; Duarte, A.; Lopes, I. salinity induced effects on the growth rates and mycelia composition of basidiomycete and zygomycete fungi. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.; Cardoso, P.; Lopes, I.; Figueira, E.; Venâncio, C. Exploring the Potencial of White-Rot Fungi Exudates on the Amelioration of Salinized Soils. Agriculture 2023, 13, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, S.; Navarro, D.; Grisel, S.; Chevret, D.; Berrin, J.; Rosso, M. The integrative omics of white rot-fungus Pycnoporus coccineus reveals co-regulated CAZymes for orchestrated lignocellulose breakdown. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuBois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eivazi, F.; Tabatabai, M. Phosphatases in soils. Soil. Biol. Biochem. 1977, 9, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenkranz, M.; Shi, H.; Ballauff, J.; Schnitzler, J.; Polle, A. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mycorrhizal fungi and symbiotic interactions with plants. Adv. Bot. Res. 2023, 105, 239–275. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, T.; Soares, L.; Oliveira, L.; Moraes, D.; Mendes, M.; Soares, C.; Bailão, A.; Bailão, M. Zinc Starvation Induces Cell Wall remodeling anda Activates the antioxidant defense System in Fonsecaea pedrosoi. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Ma, X.; Li, L. Optimal conditions for the catalytic and non-catalytic pyrolysis of water hyacinth. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 94, 337–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A. Pyrolysis of water hyacinth in a fixed bed reactor: Parametric effects on product distribution, characterization and syngas evolutionary behavior. Waste Manag. 2018, 80, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wauton, I.; Ogbeide, S.E. Investigation of the production of pyrolytic bio-oil from water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) in a fixed bed reactor using pyrolysis process. Biofuels 2022, 13, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A.; Singh, H.O.; Raja, S.K.; Singh, R.; Jat, M.L.; Padhee, A.K. Science based approach for translating water hyacinth menace into wealth for agricultural sustainability: Empirical evidence from rural India. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermak, J.D.; Gilley, J.E.; Eghball, B.; Wienhold, B.J. Leaching and sorption of nitrogen and phosphorus by crop residue. Trans. ASAE 2004, 47, 113–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.; Torstensson, G.; Aronsson, H. Nitrogen and phosphorus leaching losses from potatoes with different harvest times and following crops. Field Crops Res. 2012, 133, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogush, A.A.; Stegemann, J.A.; Williams, R.; Wood, I.G. Element speciation in UK biomass power plant residues based on composition, mineralogy, microstructure and leaching. Fuel 2018, 211, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matindi, C.N. Analysis of Heavy Metal Content in Water Hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) from Lake Victoria and Assessment of Its Potential as a Feedstock for Biogas Production. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. Available online: https://erepository.uonbi.ac.ke/handle/11295/97132 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Du, Y.; Wu, Q.; Kong, D.; Shi, Y.; Huang, X.; Luo, D.; Chen, Z.; Xiao, T.; Leung, J.Y. Accumulation and translocation of heavy metals in water hyacinth: Maximising the use of green resources to remediate sites impacted by e-waste recycling activities. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 115, 106384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, A.T.; Chen, Y.C.; Tran, B.N.T. A small-scale study on removal of heavy metals from contaminated water using water hyacinth. Processes 2021, 9, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J.R.; Peryea, F.J. Phosphate fertilizers influence leaching of lead and arsenic in a soil contaminated with lead arsenate. Water Air Soil Pollut. 1991, 57, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Ma, L.Q.; Shiralipour, A. Effects of compost and phosphate amendments on arsenic mobility in soils and arsenic uptake by the hyperaccumulator, Pteris vittata L. Environ. Pollut. 2003, 126, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkimbile, C.; Yusoff, M. Assessing water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) and lettuce (Pistia stratiotes) effectiveness in aquaculture wastewater treatment. Int. J. Phytorremediat. 2012, 14, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, G.; Demoulin, V. NaCl salinity and temperature effects on growth of three wood-rotting basidiomycetes from a Papua New Guinea coastal forest. Mycol. Res. 1997, 101, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, C.; Yang, J.; Yao, R.; Wang, X.; Xie, W.; Ge, A.H. Salinity-dependent potential soil fungal decomposers under straw amendment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 891, 164569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, C.; Xia, Z.; Xiao, K.; Xie, L. Arsenic (III)-induced oxidative defense and speciation changes in a wild Trametes versicolor strain. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baćmaga, M.; Wyszkowska, J.; Kucharski, J. Response of soil microbiota, enzymes, and plants to the fungicide azoxystrobin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revina, S.; Minnikova, T.; Ruseva, A.; Kolesnikov, S.; Kutasova, A. Catalase activity as a diagnostic indicator of the health of oil-contaminated soils after remediation. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2024, 196, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo, M.; Moldes, D.; Sanromán, M.Á. Effect of heavy metals on the production of several laccase isoenzymes by Trametes versicolor and on their ability to decolourise dyes. Chemosphere 2006, 63, 912–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Širić, I.; Humar, M.; Kasap, A.; Kos, I.; Mioč, B.; Pohleven, F. Heavy metal bioaccumulation by wild edible saprophytic and ectomycorrhizal mushrooms. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 18239–18252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, R.; Jensen, K.A.; Houtman, C.J.; Hammel, K.E. Significant levels of extracellular reactive oxygen species produced by brown rot basidiomycetes on cellulose. FEBS Lett. 2002, 531, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaño, J.D.; Zhang, J.; Anderson, C.E.; Schilling, J.S. Oxidative damage control during decay of wood by brown rot fungus using oxygen radicals. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e01937-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramdas, G.M.; BL, M.; Narendra Pratap, S.; Ramesh, R.; Verma, R.R.; Marutrao, L.A.; Ruenna, D.S.; Natasha, B.; Rahul, K. Effect of organic and inorganic sources of nutrients on soil microbial activity and soil organic carbon build-up under rice in west coast of India. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 2017, 63, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).