Abstract

Agricultural inputs based on microalgae have been successfully tested at different stages of the crop cycle, from sowing to harvest, to enhance crop performance. In this study, biomass from Nannochloropsis gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. was obtained to evaluate its effect on wheat seed germination under two temperature conditions. Microalgal biomass was produced under controlled conditions (neutral pH, air flow of 1 L·min−1, and a dilution rate of 0.2 day−1). The biomass was characterized for its lipid, carbohydrate, protein, and ash content. Subsequently, its effect on germination, as well as on glucose and amylose content in wheat seedlings, was assessed. Four biomass concentrations were tested (0.0 [distilled water], 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 g·L−1) at two incubation temperatures (25 and 35 °C). Results showed that Thalassiosira sp. lightly promoted the germination rate more than N. gaditana. Germination parameters were negatively affected by high temperature, but treatments with Thalassiosira sp. alleviated this effect, showing values comparable to those obtained at the optimal temperature. Vigor parameters were improved compared with the control in both temperatures. Glucose and amylose contents exhibited irregular but consistent patterns. However, at a temperature of 35 °C, a slight conversion of starch to glucose could be observed. Overall, microalgal biomass did not significantly improve germination or its time variables, but it could exert a protective effect against high-temperature stress, particularly in the case of Thalassiosira sp.

1. Introduction

Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) is one of the major cereals in the world, with its demand increasing annually. The need to improve yields through environmentally friendly processes is a challenge for farmers. Germination, a key factor in the crop’s growth and final yield, is particularly crucial during the productive process. Efficient sowing methods are essential due to the high seed density needed per unit area to produce strong seedlings rapidly. Germination plays a significant role in achieving optimal plant density, resulting in strong, healthy seedlings during the productive cycle.

The germination process involves four primary stages: absorption, activation, emergence, and growth [1]. For these stages to proceed successfully, optimal water availability, soil conditions, and high-quality genetic material are essential.

However, current global warming trends have made achieving these conditions significantly more difficult. Given this reality, temperature becomes a determining and influential factor in the quality and time of germination [2]. Temperature affects the imbibition rate of seeds [3] and the activity of the enzymes involved in germination (α- and β-amylases) [4]; consequently, the functionality of phytohormones is inhibited (gibberellins) [5]. The respiratory rate is modified, producing changes in the synthesis of ATP and proteins essential for embryonic growth [6]. Seeds have a specific temperature range for optimal germination; in the case of wheat, the optimal temperature is 20–25 °C [7]. Considering the sowing season in the most important wheat-growing area of Cajeme municipality, Sonora, México [8] and in different wheat-producing zones in the world [9], some temperatures exceed 35 °C. Such a high level of temperature is considered a form of heat stress to the seed during germination [7]. This creates a problem for the producer because of decreased germination rates that are commercially unacceptable.

Microalgae biomass has become a promising source for various industrial sectors, including biofuels, food products, and pigments [10]. For more than a decade, the use of microalgae in the agricultural sector has been researched due to their rich content of compounds, including carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, vitamins, minerals, phytohormones, and functional metabolites. It has been shown that phytohormones (gibberellins, cytokinins, auxins) contained in the biomass of microalgae stimulate the growth and development of crops, even under temperature-stress conditions [11,12]. Given the nature of microalgae compounds, these possess characteristics that enable them to interact with the embryo’s cells, activating metabolic functions and initiating physiological processes throughout each stage of seed germination [13]. The effect of some microalgae biomass metabolites on germination, even under heat stress conditions, plays a role in stimulating the activation of enzymes, protecting against oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS), and mitigating respiratory imbalances caused by increased temperature, thereby allowing germination while minimizing natural energy expenditure under temperature stress [14]. Therefore, the present study proposes to evaluate the germination capacity of wheat seeds treated with biomass of microalgae species Nannochloropsis gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. under high-temperature and “in vitro” conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Preparation of Microalgae Extract and Germination Assays

The cultures were grown under photoautotrophic conditions. The inoculum cultures were maintained photoautotrophically in 0.25 L Erlenmeyer flasks containing 170 mL of f/2 culture medium. The microalgae were cultivated aseptically at 25 °C, with an aeration rate of 0.6 v·v−1 min−1, and under continuous illumination of 250 μmol·m−2·s−1. The microalgae cultures were performed in triplicate using f/2 culture medium [15]. Macro- and micro-nutrients were prepared in sterilized freshwater by autoclaving (Brinkmann 2340M, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) at 121 °C for 15 min. The pellet was taken, and subsequently, the microalgae biomass was washed three times with ultrapure water (MilliQ grade, 18.2 MΩ·cm−1 at 25 °C) to remove excess salts from the microalgae and then freeze-dried in a freeze dryer (Yamato DC401, Minami Alps, Yamanashi, Japan) for 24 h, and the dry biomass was crushed and weighed [16].

Wheat seeds (Triticum aestivum L.) of the Borloug 100 variety were used for germination tests. The seeds were recently harvested and stored at 4 °C until use (approximately six months), presenting a purity of 89.3% and a germination rate of 94.3% at the time of the experiment. Borlaug 100 is a high-yielding variety that performs well under both full and limited irrigation conditions, is resistant to certain fungal and viral diseases, and is productive and adaptable, particularly during the spring-summer cycle [17].

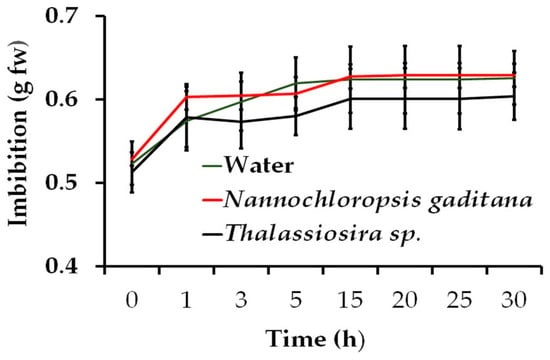

The seeds were surface sterilized before germination tests and disinfected with 20% aqueous ethanol for 2 min, then dried with absorbent paper. Additionally, in a previous bioassay, the imbibition rate of the seed was evaluated in bidistilled water at pH 7 and microalgae biomass solution at pH 7 and an electrical conductivity (EC) of 0.3–0.6 mS, respectively (Figure 1). Each solution contained 100 seeds to determine the maximum imbibition time. Microalgae biomass solutions were prepared in beakers under constant stirring at 110 rpm.

Figure 1.

Wheat seed rate of imbibition under water, N. gaditana, and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass solution at 25 °C temperatures. Average 100 seeds for each solution.

Four treatments of microalgal biomass from the Nannochloropsis gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. species, previously analyzed (Table 1) [16], were evaluated at 25 °C (optimal limited germination temperature) and 35 °C (average temperature at the time of sowing in the Yaqui Valley, México (September-October) with 24 h of imbibition in distilled water at pH 7 and 0.9–1.2 mS EC [18].

Table 1.

Biomass composition of the microalgae Nannochloropsis gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. on a dry basis [16].

2.2. Germination Parameters (Final Germination Percentage, T50 Germination, Germination Mean Time, Germination Index, and Vigor Index)

After the first germinated seed, germination counts were recorded hourly. A seed was considered germinated when its radicle exceeded twice the seed’s length. Based on the germination data, the following parameters were calculated:

Final Germination Percentage (FG)

FG = (N/SS) × 100 [19], where N is the number of germinated seeds, and SS is the total number of seeds sown. Ultimately, it was reported as the cumulative germination rate per species.

Time to 50% germination (T50)

T50 = Ti + [(N/2 − ni)/(nj − ni)] ×(tj − ti) [20], where N is the total number of germinated seeds, ni and nj are the cumulative numbers of seeds germinated at times ti and tj in hours (h), respectively.

Mean Germination Time (MGT)

MGT = ti + Σ(n·t)/Σn [21], where n represents the number of seeds germinated at time t.

Germination Index (GI):

GI = NSE/Ti + … +NSE/Tf [22], where NSE is the number of seeds that emerged at each evaluation time point, and Ti…Tf is the respective evaluation time.

Germination vigor

Root growth was monitored for up to 3 days post-imbibition, and root lengths were measured using a millimeter- and centimeter-graduated ruler. To assess seed vigor, the following indices were used:

SVI = LR (cm) × GI

SVII = DW (g) × GI

SVIII (DW + LR) × GI [23], where LR is root length, and DW is dry weight.

Germination Efficiency Index (GEI):

GEI = [(treatment FG − control FG)/FG control] × 100.

2.3. Amylose

The apparent amylose content in wheat grains was determined either pre-germination or following 72 h of soaking and germination. The analysis was made using the blue staining method [24], with slight modifications [25]. Briefly, freeze-dried and hexanal-defatted wheat grains were ground into a fine powder using a mortar. One gram of the powder was mixed with 10 mL of 6M urea (J.T. Baker) and 2 mL of DMSO (1:9 v/v, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The mixture was heated in a boiling water bath for one hour, with occasional gentle stirring. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 3700× g for 10 min. Subsequently, 25 mL of distilled water and 0.5 mL of the supernatant were transferred to a Falcon tube. To this mixture, 1 mL of an iodine/potassium iodide (I2/KI) solution (2 mg I2 and 20 mg KI, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) was poured. Immediately after adding I2/KI solution, the absorbance of the reacted solution was measured at 730 nm using a spectrophotometer (Hach 6300, Berlín, Germany). Amylose concentration was determined using an amylose standard curve (Figure S1) (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) with an R2 value of 0.9976. Results were expressed as a percentage.

2.4. Glucose

Glucose content was measured in imbibed and ungerminated seeds, and germinated wheat grains 72 h after the start of the treatment, using a slightly modified version of the HPLC method [26]. One gram of freeze-dried, hexane-defatted wheat grains was homogenized for 2 min using a T25 Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (IKA, Staufen, Germany) fitted with a 10 G dispersion shaft, in a mixture of 10 mL water and ethanol (80:10 v/v). The homogenate was heated in a boiling water bath for 15 min. Samples were filtered through cheesecloth, and 2 mL of the filtrate was collected. This filtrate was transferred to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at room temperature for 15 min at 3700 × g using an Eppendorf microcentrifuge (Eppendorf Zentrifugen GmbH, Leipzig, Germany). The supernatant was filtered through GV-type filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) with a 0.22 µm pore size. A 20 µL aliquot was injected into an HPLC system equipped with a refractive index detector (Varian ProStar 350, Varian, Sapporo, Japan) and a Supelcosil LC-NH2 column (250 mm length, 4.6 mm internal diameter, 5 µm particle size; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA), along with an LC-NH2 guard column. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and water (80:20 v/v), with a flow rate of 1 mL/min and a run time of 15 min. Glucose detection and quantification were used to prepare calibration curves from HPLC-grade glucose standards (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) at various concentrations. The glucose standard curve showed an R2 value of 0.9938 (Figure S2). Glucose levels were expressed as mg per gram of fresh weight.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

In two species of microalgae were applied four treatments (0.0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 g·L−1), each consisting of four replicates, with 100 seeds per replicate (100 seeds as the experimental unit), were grouped into 25 seeds each to facilitate evaluations and under two temperatures were analyzed statistically, and the values are reported as the mean ± standard deviation in each variable evaluated.

The results were analyzed using a completely randomized design with a factorial arrangement (2 species × 4 treatments × 2 temperatures). A three-way ANOVA was employed to calculate the significance, along with the Tukey test. The means and differences were considered significant with a probability value (p < 0.05). The relationship between species, treatment, and temperature was assessed using Statgraphics Centurion XVI (StatPoint Technologies, Inc., The Plains, Virginia, USA).

The cumulative germination rate was analyzed using the Gompertz curve to establish the cumulative growth rate equation and assess the fit between observed and predicted data for the two microalgae species, regardless of the treatment and temperature conditions applied, using RStudio (ver. 2025.05 + 496).

3. Results and Discussions

The fresh weight gain of the seeds by imbibition with distilled water and two solutions of 1.0 g L−1 of both evaluated microalgae species showed no numerical differences. It reached its maximum between 15 and 20 h, although over 90% of the weight gain occurred within the first three hours (Figure 1). This indicates that the solutes produced by the microalgae biomass at the given pH, EC, and temperature did not affect seed imbibition, allowing the seeds to complete the first stage of germination [1] without restriction, and suggests the potential for primed seeds with this treatment.

3.1. Final Percentage, T50 Germination, Germination Mean Time, Germination Index, and Vigor Index

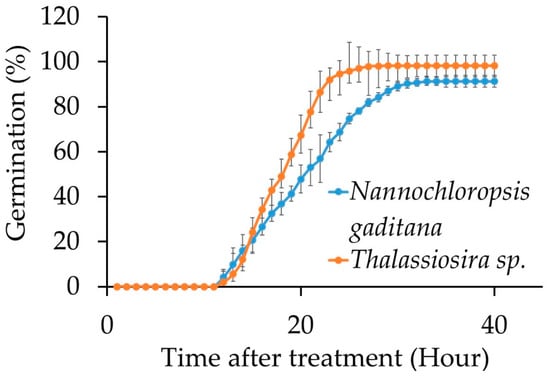

The cumulative germination rate obtained in this study showed that the application of microalgae biomass (N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp.) in wheat seeds followed the typical sigmoidal pattern described by the Gompertz model [27] (Figure 2), which showed an excellent fit with an R2 value exceeding 0.99 (Table 2 and Table S1), in both species, regardless of treatment and temperature conditions. During the initial hours following seed immersion (0–10 h), no germination was observed. Subsequently, seeds treated with N. gaditana began to germinate more rapidly; however, this rate declined over time. By hour 17, seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. exhibited significantly higher germination rates at 35 °C, surpassing those treated with N. gaditana (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cumulative germination rate of wheat treated with N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass under two temperatures.

Table 2.

Kinetics of cumulative germination percentage of wheat treated with N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass under two temperatures.

Significant differences (Table S2) in germination rates between the two species were observed from hour 17, with a 4% difference. Subsequently, a maximum difference in total germination was observed, with Thalassiosira sp. (98%) exhibiting a higher germination rate than N. gaditana (92%) (Table 3), and 4% higher than the germination reported for this seed.

Table 3.

Effect of N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass on the final germination of wheat seeds under two temperatures.

The differences observed in the cumulative germination rate were mainly influenced by temperature. This was evident in each of the analyzed variables, because seeds exposed to 35 °C exhibited delayed germination, lower germination rates, and reduced final germination percentages, especially in treatments involving the species N. gaditana. In contrast, wheat seeds treated with biomass microalga Thalassiosira sp. showed greater tolerance to high temperatures.

The present study demonstrates a germination rate that modestly exceeds the range of 84 to 95% but is consistent (Table S2). This range was previously reported for various wheat genotypes, with the maximum observed at 25 °C (96.7%) and the minimum at 35 °C (84.7%) [2]. Experiments with Sarraceno wheat (Fagopyrum esculentum M.) conducted between 15 °C and 35 °C documented similarly high germination rates, pinpointing 25–30 °C as the optimal range [28]. Likewise, increased germination was observed across wheat genotypes with a temperature elevation from 10 °C to 30 °C. Consistent with our findings, the highest germination occurred at 25 °C, reaching 100% in some treatments [29].

It is important to note that the seed utilized already exhibits a high germination rate, which limits the potential for further improvement. However, in this experiment, germination not only increased under optimal temperature conditions but also remained above the control treatment and the commercially acceptable threshold (90%) [30]. Although the differences were not statistically significant, the application of microalgal biomass showed a slight enhancement in germination even at 35 °C (Table 3 and Table S2). On the other hand, if we consider that the recommended sowing density is 100 kg ha−1 of wheat seed plus the adjustment for the percentage of germination and purity of origin to obtain a high yield [30], for each percentage unit of improvement of germination, it is possible to save 1 kg of seed, which has a local cost of 1.5 USD kg−1. In addition to what was mentioned above, the cost of microalgae and their applications must be considered, as it could lessen their commercial impact.

The lipid content of Thalassiosira sp. biomass (24%) compared to N. gaditana (14%) (Table 1) may have protected the membrane against high-temperature stress because monounsaturated fatty acids [31,32] can act as antioxidants and signaling molecules, triggering the expression of heat shock protein-related genes [33].

Few studies have investigated the use of externally applied lipids to promote seed germination. Nevertheless, a strong correlation exists between seed viability, lipid content, and stability. This relationship can have either beneficial or detrimental effects. The nonoxidized lipids are positively correlated with seed germination [34]. The temperature stress tolerance of wheat seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. biomass performance suggests the need for specific future analyses, including membrane stability assays, oxygen-reducing species, and silicon uptake in seedlings.

Table 4 presents the results for each germination variable evaluated in relation to time in response to the biomass stimulus from two microalgae species at two different temperatures. The average time to reach 50% germination (T50) was generally longer in seeds exposed to 35 °C. Wheat seeds treated with N. gaditana biomass had average T50 values ranging from 20.80 to 21.81 h at 35 °C. At the same temperature, seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. biomass had T50 roughly 15% shorter on average compared to wheat seeds treated with N. gaditana. Additionally, treatments with Thalassiosira sp. at 25 °C showed the shortest T50 values, being 2 to 4 h faster than those treated with N. gaditana at 25 °C and 35 °C, respectively. No statistically significant differences were found among control treatments and different biomass concentrations across both species; only slight delays in T50 values were noted (Table S2).

Table 4.

Effect of N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass on the germination parameters of wheat seeds under two temperatures.

Like the T50 values, the GMT variable exhibited a comparable pattern, with seeds germinating on average two hours later at 35 °C compared to 25 °C. Additionally, seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. biomass germinated 1 to 2 h faster than those treated with N. gaditana. Although no statistically significant differences were observed across treatments, a noticeable delay in germination was recorded in seeds exposed to 35 °C and treated with N. gaditana, except for T2. Mostly, the wheat seeds control showed slightly longer GMT (Table 3).

Regarding the T50 and GMT variables, wheat seeds treated with both microalgae species at 25 °C showed minimal differences across treatments. This suggests that under optimal temperature conditions, the microalgal biomass had a minimal effect on germination speed. However, seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. and exposed to 35 °C demonstrated tolerance to high-temperature stress, as the T50 was similar to that of treatments at 25 °C, and GMT showed only a slight delay. In contrast, seeds treated with N. gaditana experienced delays in T50 and GMT by 2 to 6 h and 2 to 5 h, respectively. As a result, the germination rate for Thalassiosira sp. reflected a faster germination pattern than N. gaditana. In this context, temperature is a factor that could cause delays of nearly 2–4% longer than the average time.

Buriro et al. [35] demonstrated that temperature stress changes the morphology and physiology of the wheat root system during germination, which, as a consequence, could impair water uptake by seedlings [36]. Although biostimulants have been shown to mitigate abiotic stress and enhance germination under adverse conditions [37], our study did not observe a marked improvement in germination efficiency, only a slight reduction in mean germination time.

T50 values in this work were shorter than those reported by Hussain et al. [38], who documented a T50 of approximately 72 h for wheat under salinity conditions. Previous microalgae biomass research as biostimulants has shown that seed imbibition with Acutodesmus sp. biomass (0.75 g·L−1) in tomato can advance germination by nearly two days compared to untreated controls [39]. In our study, wheat seeds treated with similar biostimulants exhibited a moderate reduction in T50 of approximately 0.94 h, compared to untreated seeds. While Hussain et al. [38] reported over 90% germination at GMT = 72 h, our results indicate a reduction of scarcely 48 h.

Consistent with Buriro et al. [35], our findings confirm that optimal germination for wheat occurs at temperatures between 20 °C and 25 °C. Additionally, it was observed that wheat seeds soaked in water or biostimulant solutions absorbed moisture more rapidly during the initial hours, promoting germination, a phenomenon reflected in the accelerated imbibition and germination observed in our treatments [40]. The GI reflects the average rate at which seeds germinate over time. In the present study, wheat seeds began to germinate between 12 and 32 h after the application of treatment (Figure 1). During the 20 h germination period, no significant differences were observed among the treatments and temperature conditions, except for the control and T3 treatments treated with N. gaditana at 35 °C; both treatments exhibited the lowest germination speeds with GI values of 3.81 and 3.88 germinated seeds per hour, respectively. In this same group, treatments T1 and T2 also exhibited lower GEI, with levels below 5 seeds h−1. In contrast, seeds placed at 25 °C, regardless of the microalgae treatment and concentration, as well as those at 35 °C treated with Thalassiosira sp., showed rates between 5 and 6 seeds per hour (Table 3).

Overall, treatments with microalgal biomass showed a marginal improvement in GI values. Wheat seeds exposed to 35 °C and treated with Thalassiosira sp. biomass exhibited a particularly enhanced response under these conditions; final germination rates not only surpassed those of the control but also matched the germination levels observed at 25 °C, regardless of the treatment level applied (Table 3).

The final germination percentage results in this experiment (Figure 1) were generally high and agree with the results of Hussain et al. [38], where more than 90% germination was obtained. In seeds treated at 25 °C, both species achieved greater than 90% germination. On the other hand, the effect of the treatments was more pronounced at 35 °C for both species of microalgae, as the differences ranged from 1 to 14 percentage points in favor of the treated samples over the control (Table 4).

In terms of the wheat germination index (GI), no significant differences were observed overall, except for seeds treated with N. gaditana (T3) at 25 °C (6.19 seeds h−1), and for T3 and the control at 35 °C (3.88 and 3.81 seeds h−1, respectively) (see Table 3). In contrast, our study applied the biostimulant directly to the seeds, with Thalassiosira sp. at 35 °C, resulting in GI as well as treatments at 25 °C in both microalgae species.

In all cases, the Germination Enhancement Index (GEI) values were barely positive, indicating that every treatment resulted in a higher final germination percentage compared to the control. In some instances, the improvement was minimal, as in wheat seeds treated with various concentrations of Thalassiosira sp. at 25 °C, where the increase ranged from 0.02% to 1.26%. However, at 35 °C, all treatment levels of this species demonstrated a more pronounced effect, exceeding 4% and reaching up to 5.60% in treatment T3. In contrast, and differing from previous reports, N. gaditana treatments at 25 °C showed a GEI increase of over 7%. At 35 °C, the response to N. gaditana was more variable: treatments T2 and T3 showed modest increments of 0.61% and 1.83%, respectively, while T1 exhibited a substantial improvement of 16.67% compared to the control.

Seed vigor is a population-level indicator of a seed’s capacity to germinate quickly and uniformly, as well as to develop into robust seedlings under both favorable and unfavorable conditions [41]. Table 4 presents the effects of applying marine microalgal biomass from two species at two temperature conditions on vigor, evaluated based on size, weight, and the combination of both parameters.

The Vigor I results reveal a general trend that the wheat seeds incubated at 25 °C exhibited greater growth and higher Vigor I values compared to those at 35 °C. Statistically significant differences (Table S3) were found in seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. at 25 °C, showing higher vigor compared to other treatments and temperatures, except for T2 and T3 using N. gaditana at the same temperature. Furthermore, Vigor I values for treatments with either of the microalgae at both temperatures were marginally higher than those for the control treatment. For instance, seeds treated with N. gaditana at 25 °C surpassed a Vigor I value of 2, whereas the control remained below this threshold. Similarly, at 35 °C, the control treatment recorded a Vigor I value below 1, while treated seeds ranged between 1.36 and 1.50. Notably, wheat seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. biomass at 25 °C reached Vigor I values between 3.35 and 3.41, exceeding the control by 0.8 units; at 35 °C, the increase over the control was 0.43 units for this same species.

For Vigor II, which accounts for the dry weight of the sprout biomass, no statistically significant differences were observed (p > 0.05) (Table S3). Although treatments with microalgae slightly outperformed the controls, temperature did not have a notable effect on Vigor II (Table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass on the germination vigor of wheat seeds under two temperatures.

Vigor III, incorporating both size and weight, displayed a pattern similar to that of Vigor I. Given the absence of significant differences in Vigor II, the observed effect was attributed primarily to seedling size rather than biomass weight (Table 4). Seeds subjected to 35 °C had slightly lower Vigor III values, approximately 2 units lower, compared to those at 25 °C. Additionally, treatments with N. gaditana resulted in marginally lower Vigor III values (around 1 or just above) relative to treatments with Thalassiosira sp. (Table 5).

The results from the evaluation of vigor types I and III across their respective modalities indicated a positive response to the application of microalgal treatments. In contrast, no significant effect was observed for vigor II. Seedling length (vigor I) appeared to be a more decisive factor in the assessment compared to seedling weight (vigor II). Similarly, vigor III behaved comparably to vigor I, suggesting minimal influence from biomass accumulation. This outcome may be attributed to the developmental stage at which vigor was measured, where the accumulation of total dietary fiber (mainly cellulose and hemicellulose) constitutes only a small and relatively stable portion of the total dry biomass [42]. In contrast, active cell division and expansion within the radicle meristem and coleoptile of the wheat embryo are ongoing during early development [7]. Slightly higher vigor values observed in microalgae-treated seeds, regardless of the species, could be attributed to the stimulatory effects of the proteins and ash content present in the microalgae (Table 1). These ashes are rich in essential micronutrients, such as Ca, Mg, Fe, Cu, Mn, and Zn [43]. In the case of Thalassiosira sp., notable quantities of bioavailable silicon compounds are also present [44]. These micronutrients play crucial roles in tissue development and metabolic pathways, including the activation of enzymes in primary metabolism and the biosynthesis of phytohormones, such as auxins [45]. The effect was more pronounced in seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp., a diatom known for its silica-rich composition, which, although not entirely bioavailable, can release silicon gradually over time [46]. This gradual availability may enhance plant growth, as silica contributes to cell wall formation, secondary metabolism, and resistance to various biotic and abiotic stress factors [47].

3.2. Amylose and Glucose Content

Amylose content was assessed at two different time points: before seed imbibition and after 72 h of imbibition using a biomass solution of N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae. Overall, no significant differences (Table S4) were observed between the initial amylose content and the content measured at 25 °C for both microalgae species, as well as at 35 °C for seeds treated with N. gaditana after 72 h of imbibition; the only exception was that the control seeds at 35 °C showed 41.44% amylose. Initially, the amylose content in the wheat seeds treated with microalgal biomass ranged from 28% to 31%. Following biomass application and incubation at 25 °C, a slight reduction in amylose levels was observed, ranging from 4% to 6%. Likewise, seeds incubated at 35 °C and treated with N. gaditana exhibited no significant changes in amylose content, while those treated with Thalassiosira sp. showed an increase ranging from 6% to 11% (Table 6).

Table 6.

Changes in amylose content in wheat seeds during germination treated with N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass under two temperatures.

As with amylose, glucose was determined at the same times. The initial glucose concentration in wheat seeds, regardless of treatment, ranged from 0.8 to 1.88 mg gr−1 dw. After 72 h of treatment and germination, an opposite trend was observed: seeds treated with N. gaditana at 25 °C showed the highest glucose accumulation, with values ranging from 9 to 14 mg gr−1 dw. Conversely, at the same temperature, seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. exhibited lower glucose concentrations, ranging from 2 to 5.7 mg g−1 dw. Whereas seeds incubated at 35 °C and treated with N. gaditana had glucose concentrations ranging from 2.6 to 4.8 mg gr−1 dw, those treated with Thalassiosira sp. reached levels between 5 and 13.07 mg gr−1 dw (Table 7).

Table 7.

Changes in glucose content in wheat seeds during germination treated with N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass under two temperatures.

The basal amylose levels observed (initial) in the wheat seeds in this study were consistent with those reported for high-quality seeds [48]. After 72 h of germination at 25 °C, a slight decrease in amylose content was detected in both wheat species. This reduction agrees with the natural germination process, during which basal metabolism is reactivated, and a series of key metabolic events occur before and after radicle emergence. As a major starch component, amylose is progressively broken down into lower-molecular-weight compounds, such as glucose. At this stage, glycolysis and the pentose phosphate pathway are initiated, followed by the Krebs cycle, to generate the energy required for early seedling development [49]. This metabolic shift was reflected in increased glucose levels in the seeds. In contrast, seeds exposed to 35 °C did not exhibit a decrease in amylose content; instead, it increased slightly, especially those treated with Thalassiosira sp. biomass. Under optimal conditions, gibberellins activate α-amylase, which hydrolyzes amylose into glucose [50]. Despite the lack of amylose degradation at 35 °C, glucose accumulation was still observed, possibly due to other sources. However, gibberellin activity and consequently α-amylase activation are suppressed at elevated temperatures. Therefore, endogenous reserves, such as lipids and proteins derived from the same seed, although supplemented by exogenous compounds provided by the microalgal treatment, may serve as alternative energy sources. Fatty acids are likely transported to glyoxysomes, where they undergo β-oxidation to yield acetyl-CoA, which subsequently enters the glyoxylate cycle via malate synthase and isocitrate lyase enzymes that remain functional at 35 °C to ultimately produce sugars in the cytoplasm [49]. Additionally, specific peptidases cleave internal peptide bonds, releasing small peptides and free amino acids such as glutamic and aspartic acids, which are mobilized to support seedling development [50].

4. Conclusions

In commercial agriculture, rapid and uniform seed germination and seedling emergence are essential for successful crop establishment. The biomass of marine microalgae N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. slightly improved germination under both optimal and less favorable temperature conditions. However, this did not influence germination time parameters (T50, GMT, GI). Improvements were mainly observed in the final germination percentage and seedling vigor indices I and III. Notably, seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. and exposed to 35 °C showed tolerance to temperature stress, as their final germination percentage and vigor indices I and III were comparable to those at 25 °C. Conversely, seeds treated with N. gaditana were more negatively affected by higher temperatures, with reductions in germination rate, germination speed, and vigor indices I and III. Analysis of amylose and glucose content at 25 °C, both initially and after 72 h, revealed a consistent pattern in which amylose levels decreased, while glucose levels increased. At 35 °C, amylose content remained stable, while glucose levels increased in seeds treated with Thalassiosira sp. biomass. However, a thorough analysis that considers the marginal effects of microalgae stimulation should be conducted to evaluate the cost–benefit balance, as well as to address the challenges of managing primed seeds, which are uncommon in wheat.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/agronomy15122917/s1, Figure S1: Amylose curve with fitted line and equation; Figure S2: Glucose curve with fitted line and equation; Table S1: Gompertz model goodness-of-fit metrics in the cumulative germination rate of wheat treated with N. gaditana and Thalassiosira sp. microalgae biomass at two temperatures; Table S2: The results of the three-way ANOVA on Treatment (Tr), Temperature (Te), Species (Spp), and their interactions on T50, GMT, GI, and GF variables, using Tr, Te, Spp, and their interaction as fixed terms and as random effects. Asterisk indicates significant differences (* p < 0.05). W = Shapiro-Wilkis test, L = Lavene’s; Table S3: The results of the three-way ANOVA on Treatment (Tr), Temperature (Te), Species (Spp), and their interactions on Vigor I, II, and III variables, using Tr, Te, Spp, and their interaction as fixed terms and as random effects. Asterisk indicates significant differences (* p < 0.05). W = Shapiro-Wilkis test, L = Lavene’s test; Table S4: The results of the three-way ANOVA on Treatment (Tr), Temperature (Te), Species (Spp), and their interactions on amylose and glucose variables, using Tr, Te, Spp, and their interaction as fixed terms and as random effects. Asterisk indicates significant differences (* p < 0.05). W = Shapiro-Wilkis test, L = Lavene’s test.

Author Contributions

L.G.A.S. methodology, statistical analysis, G.I.R.V. conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, original draft writing, and project administration. A.S.E. conceptualization, reviewing, original draft writing, and editing supervision. B.L.P.P. investigation, methodology. L.A.C.C. methodology, validation, investigation, reviewing, and editing supervision, F.G.A.F. conceptualization, review and editing, M.I.E.A. funding acquisition, methodology, validation, investigation, reviewing, and editing supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received financial support from Programa de Fomento y Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación (PROFAPI) through project PROFAPI 2025-069. Dr. Gabriel Ivan Romero Villegas and M.C. Brisia Lizbeth’s contributions were financially supported by the Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencia y Tecnología (CONAHCyT, México). Maria Isabel Estrada Alvarado and Luis Alberto Cira Chavez received support from the SEP-SES, which was provided for conducting a research stay corresponding to the call “Short Stays for Research of Members of Consolidated Academic Bodies 2019”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article or Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hartmann, H.T.; Kester, D.E. Propagación de Plantas: Principios y Prácticas, 6th ed.; Editorial Continental: Mexico City, Mexico, 1998; pp. 137–167. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, V.; Tanwar, H.; Mor, V.S.; Kumar, M.; Punia, R.C.; Dalal, M.S.; Khan, M.; Sangwan, S.; Bhuker, A.; et al. Impact of high temperature on germination, seedling growth and enzymatic activity of wheat. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portuguez-García, M.P.; Rodríguez-Ruiz, A.M.; Porras-Martínez, C.; González-Lutz, M.I. Imbibition and temperature to rupture latency of Ischaemum rugosum. Salisb. Agron. Mesoam. 2020, 31, 780–789. [Google Scholar]

- De Schepper, C.F.; Michiels, P.; Buvé, C.; Van Loey, A.M.; Courtin, C.M. Starch hydrolysis during mashing: A study of the activity and thermal inactivation kinetics of barley malt α-amylase and β-amylase. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 255, 117494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Camba, R.; Sánchez, C.; Vidal, N.; Vielba, J.M. Interactions of gibberellins with phytohormones and their role in stress responses. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H. The seed and the metabolism regulation. Biology 2022, 11, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaeim, H.; Kende, Z.; Balla, I.; Gyuricza, C.; Eser, A.; Tarnawa, Á. The effect of temperature and water stresses on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). Sustainability 2022, 14, 3887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ramos, O.H.; Herrera-Andrade, M.H.; Cruz-Medina, I.R.; Turrent-Fernández, A. Study on the production of wheat technology per agro-system, for pointing out needs of information. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agrícolas 2014, 5, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, M.; Foulkes, M.J.; Slafer, G.A.; Berry, P.; Parry, M.A.; Snape, J.W.; Angus, W.J. Raising yield potential in wheat. J. Exp. Bot. 2009, 60, 1899–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.W.; Yap, J.Y.; Show, P.L.; Suan, N.H.; Juan, J.C.; Ling, T.C.; Lee, D.J.; Chang, J.S. Microalgae biorefinery: High value products perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 229, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Shahid, S.; Nazar, N.; Hussain, A.I.; Ali, S.; Chatha, S.A.S.; Perveen, R.; Naseem, J.; Haider, M.Z.; Hussain, B.; et al. Use of phytohormones in conferring tolerance to environmental stress. In Plant Ecophysiology and Adaptation Under Climate Change: Mechanisms and Perspectives II: Mechanisms of Adaptation and Stress Amelioration; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 245–355. [Google Scholar]

- González-Pérez, B.K.; Rivas-Castillo, A.M.; Valdez-Calderón, A.; Gayosso-Morales, M.A. Microalgae as biostimulants: A new approach in agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 38, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupawalla, Z.; Shaw, L.; Ross, I.L.; Schmidt, S.; Hankamer, B.; Wolf, J. Germination screen for microalgae-generated plant growth biostimulants. Algal Res. 2022, 66, 102784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Cai, Y.; Wakisaka, M.; Yang, Z.; Yin, Y.; Fang, W.; Xu, Y.; Omura, T.; Yu, R.; Zheng, A.L.T. Mitigation of oxidative stress damage caused by abiotic stress to improve biomass yield of microalgae: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 896, 165200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillard, R.R.L. Culture of Phytoplankton for Feeding Marine Invertebrates. Cult. Mar. Invertebr. Anim. 2023, 1975, 29–60. [Google Scholar]

- Puente-Padilla, B.L.; Romero-Villegas, G.I.; Sánchez-Estrada, A.; Cira-Chávez, L.A.; Estrada-Alvarado, M.I. Effect of Marine Microalgae Biomass (Nannochloropsis gaditana and Thalassiosira sp.) on Germination and Vigor on Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Seeds “Higuera”. Life 2025, 15, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Villalba, G.; Camacho-Casas, M.A.; Alvarado-Padilla, J.I.; Huerta-Espino, J.; Villaseñor-Mir, H.E.; Ortiz-Monasterio, J.I.; Figueroa-López, P. Borlaug 100, a bread wheat variety for irrigated conditions of northwestern Mexico. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2021, 44, 123–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kolar, K. Gravimetric Determination of Moisture and Ash in Meat and Meat Products: NMKL Interlaboratory Study. J. AOAC Int. 1992, 75, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTA. International Seed Testing Association. Seed Sci. Technol. 2016, 27, 333. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.; Basra, S.M.A.; Ahmad, N.; Hafeez, K. Thermal hardening: A new seed vigor enhancement tool in rice. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2005, 47, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S.; Khajeh-Hosseini, M. Length of the lag period of germination and metabolic repair explain vigour differences in seed lots of maize (Zea mays). Seed Sci. Technol. 2007, 35, 200–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiang, S.; Wan, H. Negative Association between Seed Dormancy and Seed Longevity in Bread Wheat. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 347–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vashisth, A.; Nagarajan, S. Effect on germination and early growth characteristics in sunflower (Helianthus annuus) seeds exposed to static magnetic field. J. Plant Physiol. 2010, 167, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCready, R.M.; Hassid, W.Z. The Separation and Quantitative Estimation of Amylose and Amylopectin in Potato Starch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1943, 65, 1154–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraza-Jáuregui, G.; Soriano-Colchado, J.; Obregón, J.; Martínez, P.; Peña, F.; Velezmoro, C.; Siche, R.; Miano, A.C. Physicochemical, functional, and structural properties of starches obtained from five varieties of native potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.). In Proceedings of the LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology, Online, 27–31 July 2020; pp. 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Hernandez, J.; Gonzalez-Castro, M.J.; Vazquez-Blanco, M.E.; Vazquez-Oderiz, M.L.; Simal-Lozano, J. HPLC Determination of Sugars and Starch in Green Beans. J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazim, S.K.; Ramadhan, M. Study effect of a static magnetic field and microwave irradiation on wheat seed germination using different curves fitting model. J. Green Eng. 2020, 10, 3188–3205. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, A.J. Evaluación en Diferentes Condiciones de Germinación y Crecimiento Inicial de Trigo Sarraceno (Fagopyrum esculentum Moench). Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad Nacional de Río Negro, Río Negro, Argentina, 2020. Available online: http://rid.unrn.edu.ar:8080/bitstream/20.500.12049/6218/1/Keil_Aldana-2020.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025).

- Nyachiro, J.; Clarke, F.; DePauw, R.; Knox, R.; Armstrong, K. Temperature effects on seed germination and expression of seed dormancy in wheat. Euphytica 2002, 126, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosas-Jáuregui, I.A.; Fuentes-Dávila, G.; Félix-Fuentes, J.L.; Monserrat, M. Grain yield of four durum wheat cultivars in the Yaqui Valley, Sonora, Mexico, during the 2023–2024 crop season. Braz. J. Anim. Environ. Res. 2025, 6, 3195–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjya, R.; Marella, T.K.; Tiwari, A.; Saxena, A.; Singh, P.K.; Mishra, B. Bioprospecting of marine diatoms Thalassiosira, Skeletonema and Chaetoceros for lipids and other value-added products. Bioresour. Technol. 2020, 318, 124073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sas, A.A.A.; Arshad, A.; Das, S.K.; Pau, S.S.N. Optimum Temperature and Salinity Conditions for Growth, Lipid Contents, and Fatty Acids Composition of Centric Diatoms Chaetoceros calcitrans and Thalassiosira weissflogii. Pertanika J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 31, 689–707. [Google Scholar]

- Pranneshraj, V.; Sangha, M.K.; Djalovic, I.; Miladinovic, J.; Djanaguiraman, M. Lipidomics-assisted GWAS (LGWAS) approach for improving high-temperature stress tolerance of crops. Inter. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiebach, J.; Nagel, M.; Börner, A.; Altmann, T.; Riewe, D. Age-dependent loss of seed viability is associated with increased lipid oxidation and hydrolysis. Plant Cell Environ. 2020, 43, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buriro, M.; Wadhayo Gandahi, A.; Chand Oad, F.; Ibrahim Keerio, M.; Tunio, S.; Waseem Hassan, S.U.; Mal Oad, S. Wheat Seed Germination Under the Influence of Temperature Regimes. Sarhad 2011, 27, 539–543. [Google Scholar]

- Rajjou, L.; Duval, M.; Gallardo, K.; Catusse, J.; Bally, J.; Job, C.; Job, D. Seed germination and vigor. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 507–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Oosten, M.J.; Pepe, O.; De Pascale, S.; Silletti, S.; Maggio, A. The role of biostimulants and bioeffectors as alleviators of abiotic stress in crop plants. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4, 5, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Khaliq, A.; Matloob, A.; Wahid, M.A.; Afzal, I. Germination and growth response of three wheat cultivars to NaCl salinity. Soil Environ. 2013, 32, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gonzalez, J.; Sommerfeld, M. Biofertilizer and biostimulant properties of the microalga Acutodesmus dimorphus. J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 1051–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.E.L.; Gurmu, M. Seed vigour and water relations in wheat. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1990, 117, 441–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, L.O.; McDonald, M.B. Seed Science and Technology; Chapman & Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, C.; Nyman, M.; Andersson, R.; Alminger, M. Effects of variety and steeping conditions on some barley components associated with colonic health. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 4821–4827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čmiková, N.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Kmiecik, D.; Tomczak, A.; Drożdżyńska, A.; Ślachciński, M.; Królak, J.; Kačániová, M. Characterization of selected microalgae species as potential sources of nutrients and antioxidants. Foods 2024, 13, 2160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardo, A.; Orefice, I.; Balzano, S.; Barra, L.; Romano, G. Mini-review: Potential of diatom-derived silica for biomedical applications. App. Sci. 2021, 11, 4533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppe, D.; Kaczorek, D.; Schaller, J. Biological impacts on silicon availability and cycling in agricultural plant-soil systems. In Silicon and Nano-Silicon in Environmental Stress Management and Crop Quality Improvement; Academic Press: London, UK, 2022; pp. 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, A.; Yadav, M.; Debroy, A.; George, N. Application of nanosilica for plant growth promotion and crop improvement. In Metabolomics, Proteomes and Gene Editing Approaches in Biofertilizer Industry; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 339–361. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Fang, C.; Qian, Z.; Guo, B.; Huo, Z. Differences in starch structure, physicochemical properties and texture characteristics in superior and inferior grains of rice varieties with different amylose contents. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 110, 106170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matilla, A.J. Desarrollo y germinación de las semillas. In Fundamentos de Fisiología Vegetal, 2nd ed.; Azcón-Bieto, J., Talón, M., Eds.; McGraw-Hill Interamericana: Madrid, Spain, 2008; Chapter 2; p. 549. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Wang, W.; Lu, H.; Shu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Q. New perspectives on physiological, biochemical and bioactive components during germination of edible seeds: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 123, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P.; Primo, A. Germinación de las semillas. In Fisiología y Bioquímica Vegetal; Azcón-Bieto, J., Talón, M., Eds.; Interamericana-McGraw Hill: Madrid, Spain, 1993; pp. 419–435. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).